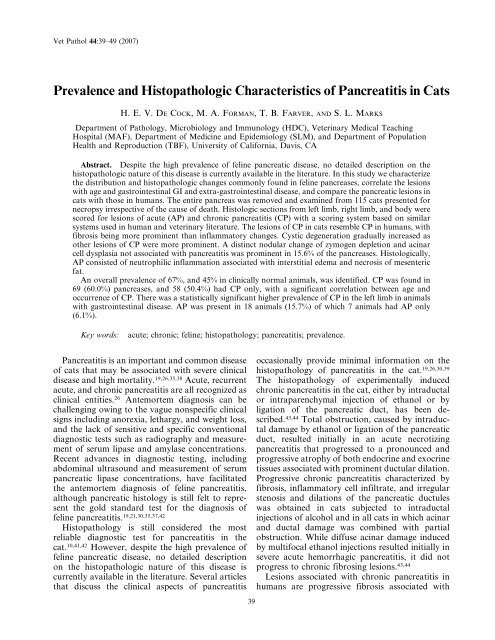

Prevalence and Histopathologic Characteristics of Pancreatitis in Cats

Prevalence and Histopathologic Characteristics of Pancreatitis in Cats

Prevalence and Histopathologic Characteristics of Pancreatitis in Cats

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

42 De Cock, Forman, Farver, <strong>and</strong> Marks Vet Pathol 44:1, 2007Table 3. <strong>Histopathologic</strong> score for acute <strong>and</strong> chronic pancreatitis <strong>in</strong> the left <strong>and</strong> right limbs <strong>and</strong> body <strong>in</strong>apparently healthy cats, cats with gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al disease, <strong>and</strong> cats with extra-gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al disease.*DivisionNormal(n)Normal MeanMean Score (6SD)GI-Disease(n)GI-Disease MeanScore (6SD)Non-GI-Disease(n)Non-GI-DiseaseMean Score (6SD)LLAP 42 0.095 (60.484) 20 0.900 (61.774) 52 0.192 (60.627)LLCP 42 0.881 (61.418) 19 1.526 (62.270) 52 1.731 (62.223)BAP 41 0.024 (60.156) 20 0.600 (61.231) 52 0.192 (60.742)BCP 41 0.829 (61.263) 20 0.850 (61.348) 52 1.635 (61.868)RLAP 42 0.000 (60.000) 20 0.500 (61.000) 53 0.226 (60.724)RLCP 42 0.619 (61.011) 20 0.800 (61.361) 53 1.566 (61.995)* LLAP 5 left limb acute pancreatitis; LLCP 5 left limb chronic pancreatitis; BAP 5 body acute pancreatitis; BCP 5 bodychronic pancreatitis; RLAP 5 right limb acute pancreatitis; RLCP 5 right limb chronic pancreatitis.mean scores for AP <strong>and</strong> CP <strong>in</strong> the differentdivisions <strong>of</strong> the pancreas for the different cl<strong>in</strong>icalgroups is given <strong>in</strong> Table 3. Healthy animals alwayshad the lowest score for AP <strong>and</strong> CP compared withanimals from group 2 or group 3. Animals withGI-disease (group 2) had higher scores <strong>of</strong> APcompared with animals <strong>in</strong> group 3, whereas thereverse occurred with CP. The highest scoresfor CP occurred <strong>in</strong> animals with extra GI-disease(group 3). In animals <strong>of</strong> group 3, the CP scoreswere comparable <strong>in</strong> all divisions <strong>of</strong> the pancreas,while <strong>in</strong> animals with GI-disease the left limb hada much higher CP score compared with the rightlimb <strong>and</strong> body.There was a statistically significant (P , .01)higher CP score <strong>in</strong> the left lobe compared with theright lobe <strong>in</strong> animals with GI-disease. There wasno statistically significant difference <strong>in</strong> AP or CPscore between the other cl<strong>in</strong>ical groups for theleft limb, right limb, <strong>and</strong> body when adjusted forage. There was a statistically significant correlation(P , .01) between the presence <strong>of</strong> CP <strong>and</strong>location <strong>in</strong> the pancreas. There was also a statisticallysignificant correlation (P , .01) between thepresence <strong>of</strong> AP <strong>and</strong> location <strong>in</strong> the pancreas. Astatistically significant correlation (P , .0005) wasfound between the age <strong>of</strong> the animal <strong>and</strong> thepresence <strong>of</strong> CP <strong>in</strong> the left limb, right limb, <strong>and</strong>body unadjusted <strong>and</strong> when adjusted for other factors.There was no correlation between age <strong>and</strong>AP score <strong>in</strong> any location, both unadjusted <strong>and</strong>when adjusted for sex <strong>and</strong> breed. Sex <strong>and</strong> breedwere shown to be nonsignificant factors <strong>in</strong> allanalyses.HistopathologyIn general, the lesions <strong>of</strong> CP were multifocal.Only <strong>in</strong> the end-stage were the lesions confluent,although small nests <strong>of</strong> normal-appear<strong>in</strong>g ac<strong>in</strong>iwere always present. Lesions <strong>of</strong> AP were alsor<strong>and</strong>omly scattered throughout the pancreas <strong>and</strong><strong>of</strong>ten extended <strong>in</strong>to the surround<strong>in</strong>g mesentericadipose tissue.Fibrosis. Fibrosis was a very prom<strong>in</strong>ent feature<strong>of</strong> CP. In the mild stages <strong>of</strong> CP, fibrosis usually wasm<strong>in</strong>imal <strong>and</strong> composed <strong>of</strong> a th<strong>in</strong> layer <strong>of</strong> densefibrous tissue that surrounded 1 or several pancreaticlobules (Fig. 1). In the more severe CP, thefibrous tissue exp<strong>and</strong>ed uniformly around 1 ormore lobules <strong>and</strong> dissected <strong>in</strong>to the lobule as th<strong>in</strong>str<strong>and</strong>s that separated the <strong>in</strong>dividual ac<strong>in</strong>i. In themost severe cases, the fibrosis was marked <strong>in</strong>the <strong>in</strong>terlobular <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>tralobular areas <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>tenreplaced large areas <strong>of</strong> pancreatic exocr<strong>in</strong>e parenchyma(Fig. 2). In all cats with severe CP, smalllobules with viable parenchyma were spared(Fig. 2). Occasionally fibrosis started with<strong>in</strong> pancreaticlobules, <strong>in</strong>dividualiz<strong>in</strong>g the ac<strong>in</strong>ar structureswithout obvious <strong>in</strong>terlobular fibrosis. The associatedac<strong>in</strong>i <strong>in</strong> these cases <strong>of</strong>ten were atrophic, <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>flammation was frequently more prom<strong>in</strong>ent.Fibrosis was not a feature <strong>of</strong> AP.Inflammation. A few scattered lymphocyteswith<strong>in</strong> the pancreatic parenchyma was considerednormal. Inflammation <strong>in</strong> CP was variable but <strong>of</strong>tenrather mild <strong>in</strong> comparison to the fibrous response.In the mild stages, only occasional <strong>in</strong>flammatorycells were scattered with<strong>in</strong> the fibrous tissue(Fig. 1). As the amount <strong>of</strong> fibrous tissue <strong>in</strong>creased,<strong>in</strong>flammation also became more prom<strong>in</strong>ent (Fig. 2)<strong>and</strong> more widely distributed with<strong>in</strong> the lobules.Lymphocytes were always the major <strong>in</strong>flammatorycomponent <strong>in</strong> CP, but occasionally eos<strong>in</strong>ophils <strong>and</strong>macrophages were also present. Macrophages wereespecially prom<strong>in</strong>ent <strong>in</strong> the lumen <strong>of</strong> cystic ac<strong>in</strong>arstructures that developed <strong>in</strong> the more chronicstages <strong>of</strong> pancreatitis (see cysts) (Fig. 3).In 29 pancreases (25%) there were nests <strong>of</strong>lymphocytes without associated signs <strong>of</strong> pancreatitis.The lymphocytes were small <strong>and</strong> monomorphous,closely arranged <strong>and</strong> located <strong>in</strong> small

44 De Cock, Forman, Farver, <strong>and</strong> Marks Vet Pathol 44:1, 2007Fig. 3. Pancreas; cat. Severe chronic pancreatitis;cystic ac<strong>in</strong>ar spaces with <strong>in</strong>tralum<strong>in</strong>al macrophages(arrows). HE. Bar 5 200 mm.A strik<strong>in</strong>g feature found <strong>in</strong> 18 (15.7%) pancreaseswas prom<strong>in</strong>ent lobulation due to the <strong>in</strong>term<strong>in</strong>gl<strong>in</strong>g<strong>of</strong> apparently normal look<strong>in</strong>g lobules with prom<strong>in</strong>entzymogen production <strong>and</strong> pale basophiliclobules with markedly less zymogen. (Fig. 5). Theac<strong>in</strong>ar cells <strong>of</strong>ten looked slightly atrophic witha small, round, pale basophilic nucleus <strong>and</strong>a small amount <strong>of</strong> dark basophilic cytoplasm that<strong>of</strong>ten conta<strong>in</strong>ed microvacuoles. However, theselobules occasionally also consisted <strong>of</strong> mildlydysplastic ac<strong>in</strong>ar cells with large, oval nuclei,<strong>in</strong>creased nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio, pale basophiliccytoplasm, <strong>and</strong> scattered mitotic figures. Interlobularducts were not evident <strong>in</strong> these types <strong>of</strong>lobules. This feature appeared <strong>in</strong>dependently <strong>of</strong>other changes <strong>in</strong> the pancreas.In addition, atypical pancreatic nodules werefound <strong>in</strong> 14 pancreases (12.2%). Two differenttypes could be dist<strong>in</strong>guished. In the basophilic/vacuolated type, the cells conta<strong>in</strong>ed a prom<strong>in</strong>entamount <strong>of</strong> cytoplasm that was pale basophilic orvacuolated (Fig. 6A). The vacuolation <strong>in</strong> thesenodules was <strong>of</strong>ten more prom<strong>in</strong>ent <strong>in</strong> the antilum<strong>in</strong>alsite <strong>of</strong> the ac<strong>in</strong>ar cell. In the eos<strong>in</strong>ophilicFig. 4. Pancreas; cat. Large cysts l<strong>in</strong>ed by ac<strong>in</strong>arcells without significant chronic pancreatitis. The l<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gcells have normal zymogen granules. HE. Bar 5100 mm.type, the cytoplasm had a pale eos<strong>in</strong>ophilic glassylook<strong>in</strong>gcontent (Fig. 6B). Vacuolation <strong>of</strong> theac<strong>in</strong>ar cells was not always conf<strong>in</strong>ed to atypicalnodules. Scattered throughout the pancreas, smallareas with cytoplasmic vacuolation, was not uncommon.This type <strong>of</strong> vacuolation was dist<strong>in</strong>ctivelydifferent from the vacuolation seen <strong>in</strong> atypicalnodules, characterized by small well-demarcatedvacuolar spaces r<strong>and</strong>omly distributed with<strong>in</strong> a basophiliccytoplasm.Interlobular <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>tralobular ducts. In normalpancreases, the large <strong>in</strong>tralobular ducts were <strong>of</strong>tendilated <strong>and</strong> the lumen was <strong>of</strong>ten filled with a paleeos<strong>in</strong>ophilic, watery, amorphous mucoprote<strong>in</strong>ousmaterial. The ducts were l<strong>in</strong>ed by a low columnarepithelium that <strong>of</strong>ten desquamated regionally. Thelatter was considered an artifact caused by manipulation<strong>of</strong> the tissues.Changes <strong>in</strong> the ducts were generally m<strong>in</strong>imal <strong>and</strong>not related to the extent <strong>of</strong> AP <strong>and</strong> CP <strong>in</strong> thesurround<strong>in</strong>g exocr<strong>in</strong>e pancreas. The most commonchange <strong>in</strong> the small <strong>and</strong> larger <strong>in</strong>terlobular ducts

Vet Pathol 44:1, 2007 <strong>Pancreatitis</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Cats</strong> 45Fig. 5. Pancreas; cat. Prom<strong>in</strong>ent lobulation ow<strong>in</strong>gto the <strong>in</strong>term<strong>in</strong>gl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> apparently normal look<strong>in</strong>globules with prom<strong>in</strong>ent zymogen production <strong>and</strong> palebasophilic lobules with markedly less zymogen. Nopancreatitis is apparent. HE. Bar 5 100 mm.was mild to moderate dilation. The mucoprote<strong>in</strong>varied <strong>in</strong> these ducts from pale eos<strong>in</strong>ophilic todark eos<strong>in</strong>ophilic <strong>of</strong>ten with a slight granular, oroccasionally more mucoid, pale basophilic appearance.M<strong>in</strong>eralization was rare <strong>and</strong>, if present,consisted <strong>of</strong> very small concrements. Pancreaticstones were not identified. The epithelium <strong>in</strong>markedly dilated <strong>in</strong>terlobular ducts appeared lowcuboidal to flat. In 8 cases, the epithelium wasconvoluted form<strong>in</strong>g small <strong>in</strong>vag<strong>in</strong>ations <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>tralum<strong>in</strong>alpapillary projections.Ductal <strong>in</strong>flammation was found <strong>in</strong> 12 cases. Inmost cases, the <strong>in</strong>flammatory <strong>in</strong>filtrate was verymild, lymphocytic, <strong>and</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>ly periductular. Insome cases, there was also a neutrophilic component<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>tralum<strong>in</strong>al <strong>in</strong>filtration, rarely withaccompany<strong>in</strong>g bacteria. Scattered epithelial cellswith changes consistent with apoptosis were occasionallyfound <strong>in</strong> association with ductal <strong>in</strong>flammation.A prom<strong>in</strong>ent ductal <strong>in</strong>flammation characterizedby a diffuse periductular lymphocytic<strong>in</strong>flammation with multifocal lymphoid follicleFig. 6. Pancreas; cat. Fig. 6a. Eos<strong>in</strong>ophilic atypicalnodule. Fig. 6b. Basopilic atypical nodule <strong>in</strong> the fel<strong>in</strong>epancreas. HE. Bar 5 25 mm.formation was found <strong>in</strong> 2 pancreases (Fig. 7). Theamount <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>flammation <strong>in</strong> these ducts was farmore prom<strong>in</strong>ent than the <strong>in</strong>flammation <strong>of</strong> thesurround<strong>in</strong>g parenchyma.Islets. Amyloidosis was present <strong>in</strong> general <strong>in</strong>34 (29.6%) <strong>of</strong> the pancreases, vary<strong>in</strong>g from mild(,50% <strong>of</strong> the islets affected) (10.4%), to moderate(50–75% <strong>of</strong> the islets affected) (10.4%), to severe(75–100% <strong>of</strong> the islets affected) (8.7%).Vascular changes. Mild to severe arteriosclerosis,characterized by <strong>in</strong>timal fibrosis, was foundonly <strong>in</strong> 5 cats, either <strong>in</strong> the pancreatic-duodenalartery <strong>and</strong> gastroduodenal ve<strong>in</strong>, or <strong>in</strong> the branchesthere<strong>of</strong> with<strong>in</strong> the pancreas.DiscussionThis study confirms that CP is common <strong>in</strong> cats,with an overall study prevalence <strong>of</strong> 67%, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g45% <strong>of</strong> apparently healthy cats. These figures areconsiderably higher than those previously reported,perhaps reflect<strong>in</strong>g the high <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong> severe <strong>and</strong>

46 De Cock, Forman, Farver, <strong>and</strong> Marks Vet Pathol 44:1, 2007Fig. 7. Pancreas; cat. Significant periductular lymphocytic<strong>in</strong>flammation form<strong>in</strong>g lymphoid follicles. HE.Bar 5 250 mm.complicated cl<strong>in</strong>ical conditions <strong>in</strong> the study population.11,26,30,38 In addition, the detailed exam<strong>in</strong>ation<strong>of</strong> the entire pancreas detected even very mildlesions as reflected by the low mean CP scoresfound <strong>in</strong> the pancreases <strong>of</strong> the healthy cats. Thef<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g is also supported by the observations <strong>of</strong>Ste<strong>in</strong>er et al., who found a discrepancy betweenthe prevalence <strong>of</strong> pancreatitis <strong>in</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical <strong>and</strong> pathologicstudies from which they concluded thata significant number <strong>of</strong> cats have subcl<strong>in</strong>icalpancreatitis. 38The high prevalence <strong>of</strong> CP <strong>in</strong> the cats with GIdiseaseis not surpris<strong>in</strong>g; however, cats withdisorders not <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g the abdomen had a similaroccurrence <strong>of</strong> CP that was not attributable to agedifferences. This f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g might suggests that thepancreas is very sensitive to drugs, stress, metabolicderangements, or ischemia associated witha wide variety <strong>of</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical conditions <strong>and</strong> potentiallyexpla<strong>in</strong>s why mild pancreatic lesions are commoneven <strong>in</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ically healthy animals. Similarly, Stammfound an unexpectedly high <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong> pancreaticlesions such as lipomatosis, fibrosis, alterations <strong>of</strong>ducts <strong>and</strong> ductal epithelium, <strong>in</strong>flammatory <strong>in</strong>filtrates,focal necrosis, ac<strong>in</strong>ar dilation, <strong>and</strong> vascularchanges <strong>in</strong> his study <strong>of</strong> 112 human pancreasescollected from unselected autopsies <strong>of</strong> adult patientswith no known pancreatic disease. 36A significant correlation was found betweenage <strong>and</strong> CP <strong>in</strong> the cat. Previous studies also havereported that older cats are more likely to presentwith pancreatitis. 11,26 Mansfield <strong>and</strong> Jones notedthat Siamese cats were more likely to develop pancreatitiscompared with other breeds; however, wefound no correlation between breed <strong>and</strong> pancreatitis<strong>in</strong> our study. 26 A plausible reason for thisf<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g is that most cats <strong>in</strong> the Mansfield <strong>and</strong> Jonesstudy were Domestic short hair (71%) <strong>and</strong> otherbreeds may have been under represented.The lesions <strong>of</strong> CP <strong>in</strong> cats partially resemble thechanges <strong>of</strong> CP <strong>in</strong> humans. As <strong>in</strong> humans, fibrosis ismore prom<strong>in</strong>ent than <strong>in</strong>flammation. 18,29 A majordifference between fel<strong>in</strong>e CP <strong>in</strong> this study <strong>and</strong>human CP is <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>of</strong> the pancreatic ducts,which is a prom<strong>in</strong>ent feature <strong>in</strong> human CP, <strong>and</strong> ismild <strong>in</strong> cats. 27 Common lesions that occur <strong>in</strong>human pancreatic ducts are <strong>in</strong>tralum<strong>in</strong>al mucoprote<strong>in</strong>accumulation <strong>and</strong> prom<strong>in</strong>ent m<strong>in</strong>eralization/stone formation, ductular dilation, epithelial metaplasia,<strong>and</strong> ductal muc<strong>in</strong>ous hyperplasia. 2,3,8,22,27,29Ductal muc<strong>in</strong>ous hyperplasia, preneoplastic epithelialmetaplasia, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>traductal stone formationwere not identified <strong>in</strong> cat pancreases. Furthermore,ductular dilation, epithelial changes, mucoprote<strong>in</strong>accumulation, <strong>and</strong> m<strong>in</strong>eralization were remarkablymild <strong>in</strong> affected cats. This f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g is <strong>in</strong> contrastwith the observations <strong>of</strong> Jubb et al., who describeCP as an extension from ductular <strong>in</strong>flammation. 20Zhao et al. also report ductular epithelial flatten<strong>in</strong>g,epithelial proliferation, <strong>and</strong> stenosis <strong>in</strong> experimentally<strong>in</strong>duced pancreatitis <strong>in</strong> cats. 44 A possibleexplanation is that the technique used to <strong>in</strong>ducepancreatitis <strong>in</strong> the cats <strong>in</strong> this study, namely,ductular damage is not representative for the waythe natural disease develops.Ac<strong>in</strong>ar cell metaplasia is common <strong>in</strong> humanCP. 9,14,33 The changes <strong>in</strong> the ac<strong>in</strong>ar cells as well asthe ductular epithelial changes are consideredpreneoplastic lesions, <strong>and</strong> a gradual progressionfrom mild to severe metaplasia <strong>and</strong> concurrentneoplasia has been well documented. 9,14,27,33 Whileatypical nodules <strong>and</strong> nodular atrophy with occasionaldysplasia (see below <strong>in</strong> discussion) were<strong>of</strong>ten present <strong>in</strong> the fel<strong>in</strong>e pancreases, transition tomore dist<strong>in</strong>ct preneoplastic or neoplastic changeswere not identified. The plausible reason for thisdifference is the different etiology <strong>of</strong> pancreatitis <strong>in</strong>humans <strong>and</strong> cats. Alcohol abuse is responsible for70% <strong>of</strong> CP <strong>in</strong> humans, while the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g 30% is

Vet Pathol 44:1, 2007 <strong>Pancreatitis</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Cats</strong> 47autoimmune, dietary, genetic, idiopathic, or secondaryto pancreatic duct obstruction. 8,22,27,29 Thecause <strong>of</strong> pancreatitis <strong>in</strong> cats is still highly speculative<strong>and</strong>, accord<strong>in</strong>g to Ste<strong>in</strong>er <strong>and</strong> Williams, 90% <strong>of</strong>the cases are idiopathic. 37 Correlations have beenfound between <strong>in</strong>flammatory bowel disease (IBD)<strong>and</strong> cholangiohepatitis <strong>and</strong> the presence <strong>of</strong> CP. 40Differentiation between the different etiologies<strong>of</strong> CP based on histopathologic morphology wasnot possible <strong>in</strong> this study. This is similar to thef<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> humans, <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g that pancreaticdisease, <strong>in</strong>dependent <strong>of</strong> the underly<strong>in</strong>g etiology,reaches a common immunologic stage beyondwhich it appears to progress as a s<strong>in</strong>gle dist<strong>in</strong>ctiveentity. 34 An exception is the recently documentedautoimmune pancreatitis <strong>in</strong> humans characterizedby prom<strong>in</strong>ent periductular lymphoplasmacytic <strong>in</strong>flammationassociated with periductular sclerosis.23,28,31 A comparable severe lymphocytic <strong>in</strong>flammationwas observed <strong>in</strong> 2 fel<strong>in</strong>e pancreases(Fig. 7).Some histopathologic features found <strong>in</strong> fel<strong>in</strong>e CPmight be suggestive <strong>of</strong> a more specific etiology.Small lymphocytic <strong>in</strong>filtrates with no associatedparenchymal lesions were common <strong>in</strong> the exam<strong>in</strong>edfel<strong>in</strong>e pancreases. It appeared as a subjectiveobservation that these <strong>in</strong>filtrates were commonlyassociated with <strong>in</strong>flammatory bowel disease.In addition, the multilobular atrophy (Fig. 5)sometimes associated with dysplasia, but notassociated with <strong>in</strong>flammation found <strong>in</strong> 15.6% <strong>of</strong>the pancreases, is most likely associated witha specific <strong>in</strong>sult to the pancreas. These lesions havebeen referred to <strong>in</strong> the literature as hyperplasticnodules. 20 However, it has never been <strong>in</strong>vestigatedwhether these lesions really are hyperplastic or not.In the pancreases exam<strong>in</strong>ed for this project, thecells appeared rather atrophic based on the reducedamount <strong>of</strong> cytoplasm <strong>and</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> zymogen production.One possible reason for this is obstruction<strong>of</strong> smaller pancreatic ducts lead<strong>in</strong>g to atrophy<strong>of</strong> the associated lobule. Zhao et al. describedextensive exocr<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> endocr<strong>in</strong>e pancreatic atrophywithout fibrosis or <strong>in</strong>flammation <strong>in</strong> cases withcomplete obstruction <strong>of</strong> the pancreatic duct. 44However, Zhao et al. also found dilated ducts <strong>in</strong>these particular cases, which was not present <strong>in</strong> themultilobular atrophy type <strong>of</strong> our study. 44 Moreresearch is warranted to determ<strong>in</strong>e the underly<strong>in</strong>gcause for this specific lesion.Some age-related changes described <strong>in</strong> thehuman pancreas were also frequently noticed <strong>in</strong>fel<strong>in</strong>e pancreases. This <strong>in</strong>cluded ac<strong>in</strong>ar cell vacuolation<strong>and</strong> atypical eos<strong>in</strong>ophilic <strong>and</strong> basophilicnodules. In addition, several pancreases had cysticstructures not related to CP. It was remarkablethat a high percentage <strong>of</strong> the cats with such cystswere <strong>of</strong> a long-haired breed. S<strong>in</strong>ce long-hairedbreeds have a predisposition for polycystic kidneydisease syndrome, the pancreatic cysts might berelated to this disease. 4–6,12 Similarly, <strong>in</strong> people withpolycystic kidney disease, pancreatic cysts are notuncommon. 1Pancreatic biopsy is still considered the goldst<strong>and</strong>ard for the diagnosis <strong>of</strong> CP <strong>in</strong> humans <strong>and</strong>cats. 10,13,17,41,42 Even acute necrotiz<strong>in</strong>g pancreatitis<strong>and</strong> CP <strong>in</strong> cats cannot be dist<strong>in</strong>guished from eachother solely on the basis <strong>of</strong> history, physicalexam<strong>in</strong>ation f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs, results <strong>of</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>icopathologictest<strong>in</strong>g, radiographic abnormalities, or ultrasonographicabnormalities. 15 In humans, a highly significantcorrelation exists between direct functiontests <strong>and</strong> histopathology <strong>of</strong> the exocr<strong>in</strong>e pancreas.17,18Surgical biopsy is facilitated by tak<strong>in</strong>ga biopsy <strong>of</strong> the most accessible part <strong>of</strong> the pancreas.An important observation <strong>in</strong> our study was thef<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> higher mean CP scores <strong>in</strong> the leftpancreatic limb <strong>in</strong> cats with GI-disease. The leftlimb is the most accessible portion <strong>of</strong> the pancreas,which should facilitate the diagnosis <strong>of</strong> CP <strong>in</strong> catswith GI-disease. In contrast, we did not f<strong>in</strong>d anydifferences <strong>in</strong> the severity <strong>of</strong> pancreatic scores <strong>in</strong>the left limb, right limb, or body <strong>in</strong> cats with extra-GI disease. The reason for the differences <strong>in</strong> CPscores <strong>in</strong> the different divisions <strong>of</strong> the pancreas <strong>in</strong>animals with abdom<strong>in</strong>al disease is most likelyrelated to anatomic characteristics, blood supply,or both <strong>in</strong> relation to the rest <strong>of</strong> the GI tract. Theleft limb, which had higher scores <strong>of</strong> CP, was alsosignificantly bigger than the right limb. Therefore,it is assumed that differences <strong>in</strong> the size or morphology<strong>of</strong> the ducts might <strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>in</strong>vasion <strong>of</strong>bacteria or regurgitation <strong>of</strong> bile from the GI tract.In contrast, <strong>in</strong> animals with generalized disease,the entire pancreas had comparable scores. It isthought that the lesions <strong>in</strong> these cases are related toblood-borne <strong>in</strong>sults <strong>and</strong> therefore are more evenlydistributed lesions.Acute pancreatitis was relatively uncommon <strong>in</strong>this study as was the prevalence <strong>of</strong> AP <strong>and</strong> CP <strong>in</strong>the same pancreas. Forman et al. found a prevalence<strong>of</strong> 44% <strong>of</strong> AP <strong>and</strong> CP <strong>in</strong> the same pancreas <strong>in</strong>their study, which is significantly higher than the9.6% found <strong>in</strong> this study. 16 The most likely reasonfor this is the difference <strong>in</strong> selected animals for bothstudies.This study underscores the high prevalence <strong>of</strong> CP<strong>in</strong> cats. <strong>Histopathologic</strong> changes resemble thelesions found <strong>in</strong> human CP, although preneoplasticchanges were not noticed <strong>in</strong> cats. While determi-

48 De Cock, Forman, Farver, <strong>and</strong> Marks Vet Pathol 44:1, 2007nation <strong>of</strong> the underly<strong>in</strong>g cause might not be possiblebased on histopathologic exam<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> thepancreas <strong>in</strong> most cases, very typical lesions werenoticed <strong>in</strong> fel<strong>in</strong>e pancreases that warrant furtherresearch to determ<strong>in</strong>e the underly<strong>in</strong>g cause.AcknowledgementsS<strong>in</strong>cere thanks are due to all the pathologists,cl<strong>in</strong>icians, students, <strong>and</strong> technicians <strong>of</strong> University <strong>of</strong>California, Davis, who helped collect cases for thisproject. Specifically, we would like to thank MonicaKratochvil for her excellent assistance. The authorsappreciate the critical review <strong>of</strong> this manuscript by Dr.James N. MacLachlan, Department <strong>of</strong> Pathology,Microbiology, <strong>and</strong> Immunology, University <strong>of</strong> California,Davis, School <strong>of</strong> Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e.References1 Al-Bhalal L, Akhtar M: Molecular basis <strong>of</strong> autosomaldom<strong>in</strong>ant polycystic kidney disease. Adv AnatPathol 12:126–133, 20052 Allen-Mersh TG: What is the significance <strong>of</strong>pancreatic ductal muc<strong>in</strong>ous hyperplasia? Gut 26(8):825–833, 19853 Allen-Mersh TG: Pancreatic ductal muc<strong>in</strong>ous hyperplasia:distribution with<strong>in</strong> the pancreas, <strong>and</strong>effect <strong>of</strong> variation <strong>in</strong> ampullary <strong>and</strong> pancreatic ductanatomy. Gut 29(10): 1392–1396, 19884 Barrs VR, Gunew M, Foster SF, Beatty JA, MalikR: <strong>Prevalence</strong> <strong>of</strong> autosomal dom<strong>in</strong>ant polycystickidney disease <strong>in</strong> Persian cats <strong>and</strong> related breeds <strong>in</strong>Sydney <strong>and</strong> Brisbane. Aust Vet J 79:257–259, 20015 Barthez PY, Rivier P, Begon D: <strong>Prevalence</strong> <strong>of</strong>polycystic kidney disease <strong>in</strong> Persian <strong>and</strong> Persianrelated cats <strong>in</strong> France. J Fel<strong>in</strong>e Med Surg 5:345–347,20036 Cannon MJ, MacKay AD, Barr FJ, Rudorf H,Bradley KJ, Gruffydd-Jones TJ: <strong>Prevalence</strong> <strong>of</strong> polycystickidney disease <strong>in</strong> Persian cats <strong>in</strong> the UnitedK<strong>in</strong>gdom. Vet Rec 149:409–411, 20017 Chari ST, S<strong>in</strong>ger MV: The problem <strong>of</strong> classification<strong>and</strong> stag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> chronic pancreatitis. Proposals basedon current knowledge <strong>of</strong> its natural history.Sc<strong>and</strong> J Gastroenterol 29:949–960, 19948 Cruickshank AH: Non<strong>in</strong>fective chronic pancreatitis.In: Pathology <strong>of</strong> the Pancreas, ed. Cruickshank AH<strong>and</strong> Benhow EW, pp. 233–258. Spr<strong>in</strong>ger, London,UK, 19959 Cylwik B, Nowak HF, Puchalski Z, Barczyk J:Epithelial anomalies <strong>in</strong> chronic pancreatitis as a riskfactor <strong>of</strong> pancreatic cancer. Hepatogastroenterology45:528–532, 199810 Dill-Macky E: Pancreatic diseases <strong>of</strong> cats. CompendCont<strong>in</strong> Educ Pract Vet 15:589–598, 199311 Duffel SJ: Some aspects <strong>of</strong> pancreatic disease <strong>in</strong> thecat. J Small Anim Pract 16:365–374, 197512 Eaton KA, Biller DS, DiBartola SP, Rad<strong>in</strong> MJ,Wellman M: Autosomal dom<strong>in</strong>ant polycystic kidneydisease <strong>in</strong> Persian <strong>and</strong> Persian-cross cats. Vet Pathol34:117–126, 199713 Etemad B, Whitcomb DC: Chronic pancreatitis:diagnosis, classification, <strong>and</strong> new genetic developments.Gastroenterology 120:682–707, 200114 Fang J, Hussong J, Roebuck BD, Talamonti MS,Rao MS: Atypical ac<strong>in</strong>ar cell foci <strong>in</strong> humanpancreas: morphological <strong>and</strong> morphometric analysis.Int J Pancreatol 22:127–130, 199715 Ferreri JA, Hardam E, Kimmel SE, Saunders HM,Van W<strong>in</strong>kle TJ, Drobatz KJ, Washabau RJ:Cl<strong>in</strong>ical differentiation <strong>of</strong> acute necrotiz<strong>in</strong>g fromchronic nonsuppurative pancreatitis <strong>in</strong> cats: 63 cases(1996–2001). J Am Vet Med Assoc 223:469–474,200316 Forman MA, Marks SL, De Cock HE, Hergesell EJ,Wisner ER, Baker TW, Kass PH, Ste<strong>in</strong>er JM,Williams DA: Evaluation <strong>of</strong> serum fel<strong>in</strong>e pancreaticlipase immunoreactivity <strong>and</strong> helical computed tomographyversus conventional test<strong>in</strong>g for the diagnosis<strong>of</strong> fel<strong>in</strong>e pancreatitis. J Vet Intern Med18:807–815, 200417 Hayakawa T, Kondo T, Shibata T, Noda A, SuzukiT, Nakano S: Relationship between pancreaticexocr<strong>in</strong>e function <strong>and</strong> histological changes <strong>in</strong> chronicpancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 87:1170–1174, 199218 Heij HA, Obertop H, van Blankenste<strong>in</strong> M, ten KateFW, Westbroek DL: Relationship between functional<strong>and</strong> histological changes <strong>in</strong> chronic pancreatitis.Dig Dis Sci 31:1009–1013, 198619 Hill RC, Van W<strong>in</strong>kle TJ: Acute necrotiz<strong>in</strong>g pancreatitis<strong>and</strong> acute suppurative pancreatitis <strong>in</strong> the cat. Aretrospective study <strong>of</strong> 40 cases (1976-1989). J VetIntern Med 7:25–33, 199320 Jubb KVF: The pancreas. In: Pathology <strong>of</strong> DomesticAnimals, ed. Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, <strong>and</strong> PalmerN, pp. 407–424. Academic Press, San Diego, CA,199321 Kitchell BE, Strombeck DR, Cullen J, Harrold D:Cl<strong>in</strong>ical <strong>and</strong> pathologic changes <strong>in</strong> experimentally<strong>in</strong>duced acute pancreatitis <strong>in</strong> cats. Am J Vet Res47:1170–1173, 198622 Klöppel G, Heitz, Ph: Exocr<strong>in</strong>e pancreas. In:Pancreatic Pathology, ed. Klöppel G <strong>and</strong> Heitz,Ph, pp. 3–114. Churchill Liv<strong>in</strong>gstone, Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh,UK, 198423 Klöppel G, Luttges J, Lohr M, Zamboni G, LongneckerD: Autoimmune pancreatitis: pathological,cl<strong>in</strong>ical, <strong>and</strong> immunological features. Pancreas27:14–19, 200324 Longnecker DS, Hashida Y, Sh<strong>in</strong>ozuka H: Relationship<strong>of</strong> age to prevalence <strong>of</strong> focal ac<strong>in</strong>ar celldysplasia <strong>in</strong> the human pancreas. J Natl Cancer Inst65:63–66, 198025 Longnecker DS, Sh<strong>in</strong>ozuka H, Dekker A: Focalac<strong>in</strong>ar cell dysplasia <strong>in</strong> human pancreas. Cancer45:534–540, 198026 Mansfield CS, Jones BR: Review <strong>of</strong> fel<strong>in</strong>e pancreatitispart two: cl<strong>in</strong>ical signs, diagnosis <strong>and</strong> treatment.J Fel<strong>in</strong>e Med Surg 3:125–132, 2001

Vet Pathol 44:1, 2007 <strong>Pancreatitis</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Cats</strong> 4927 Mitchell RMS, Byrne MF, Baillie J: <strong>Pancreatitis</strong>.Lancet 361:1447–1455, 200328 Okazaki K: Cl<strong>in</strong>ical relevance <strong>of</strong> autoimmune-relatedpancreatitis. Best Pract Res Cl<strong>in</strong> Gastroenterol16:365–378, 200229 Owen DA, Kelly JK: Embryology, normal anatomy,<strong>and</strong> histology <strong>of</strong> the pancreas. In: Pathology <strong>of</strong> theGallbladder, Biliary Tract <strong>and</strong> Pancreas, ed. OwenDA, pp. 1–14. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 200130 Owens JM: Pancreatic disease <strong>in</strong> the cat. J Am AnimHosp Assoc 11:83–89, 197531 Pearson RK, Longnecker DS, Chari ST, Smyrk TC,Okazaki K, Frulloni L, Cavall<strong>in</strong>i G: Controversies <strong>in</strong>cl<strong>in</strong>ical pancreatology: autoimmune pancreatitis:does it exist? Pancreas 27:1–13, 200332 Pitchumoni CS, Glasser M, Saran RM, PanchacharamP, Thelmo W: Pancreatic fibrosis <strong>in</strong> chronicalcoholics <strong>and</strong> nonalcoholics without cl<strong>in</strong>icalpancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 79:382–388,198433 Sh<strong>in</strong>ozuka H, Lee RE, Dunn JL, Longnecker DS:Multiple atypical ac<strong>in</strong>ar cell nodules <strong>of</strong> the pancreas.Hum Pathol 11:389–391, 198034 Shrikh<strong>and</strong>e SV, Martignoni ME, Shrikh<strong>and</strong>e M,Kappeler A, Ramesh H, Zimmermann A, BuchlerMW, Friess H: Comparison <strong>of</strong> histological features<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>flammatory cell reaction <strong>in</strong> alcoholic, idiopathic<strong>and</strong> tropical chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg90:1565–1572, 200335 Simpson KW, Shiroma JT, Biller DS: Antemortemdiagnosis <strong>of</strong> pancreatitis <strong>in</strong> four cats. J Small AnimPract 35:93–99, 199436 Stamm BH: Incidence <strong>and</strong> diagnostic significance <strong>of</strong>m<strong>in</strong>or pathologic changes <strong>in</strong> the adult pancreas atautopsy: a systematic study <strong>of</strong> 112 autopsies <strong>in</strong>patients without known pancreatic disease. HumPathol 15:677–683, 198437 Ste<strong>in</strong>er JM, Williams DA: Fel<strong>in</strong>e Tryps<strong>in</strong>-likeImmunoreactivity <strong>in</strong> Fel<strong>in</strong>e Exocr<strong>in</strong>e PancreaticDisease. Comp Cont<strong>in</strong> Educ Pract Vet 18:543–547,199638 Ste<strong>in</strong>er JM, Williams DA, Davis A: Fel<strong>in</strong>e pancreatitis.Comp Cont<strong>in</strong> Educ Pract Vet 19:590–601,199739 Swift NC, Marks SL, MacLachlan NJ, Norris CR:Evaluation <strong>of</strong> serum fel<strong>in</strong>e tryps<strong>in</strong>-like immunoreactivityfor the diagnosis <strong>of</strong> pancreatitis <strong>in</strong> cats. J AmVet Med Assoc 217:37–42, 200040 Weiss DJ, Gagne JM, Armstrong PJ: Relationshipbetween <strong>in</strong>flammatory hepatic disease <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>flammatorybowel disease, pancreatitis, <strong>and</strong> nephritis <strong>in</strong>cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 209:1114–1116, 199641 Whitney M: The laboratory assessment <strong>of</strong> can<strong>in</strong>e<strong>and</strong> fel<strong>in</strong>e pancreatitis. Vet Med 88:1045–1052, 199342 Williams D: Diagnosis <strong>and</strong> management <strong>of</strong> pancreatitis.J Small Anim Pract 35:445–454, 199343 Zhao P, Tu J, Martens A, Ponette E, Van SteenbergenW, Oord JV, Fevery J: Radiologic <strong>in</strong>vestigations<strong>and</strong> pathologic results <strong>of</strong> experimental chronicpancreatitis <strong>in</strong> cats. Acad Radiol 5:850–856, 199844 Zhao P, Tu J, van den Oord JJ, Fevery J: Damage toduct epithelium is necessary to develop progress<strong>in</strong>glesions <strong>of</strong> chronic pancreatitis <strong>in</strong> the cat. Hepatogastroenterology43:1620–1626, 1996Request repr<strong>in</strong>ts from Dr. Hilde E. V. De Cock, University <strong>of</strong> Antwerp, Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Pathology, Universiteitsple<strong>in</strong> 1,Wilrijk, 2610 (Belgium). E-mail: hilde.decock@ua.ac.be.