Small Arms and Light Weapons - Harry Frank Guggenheim ...

Small Arms and Light Weapons - Harry Frank Guggenheim ...

Small Arms and Light Weapons - Harry Frank Guggenheim ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

CONTENTSWEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTIONJoel Wallman1SMALL ARMS RESEARCH:WHERE WE ARE AND WHERE WE NEED TO GOEdward J. Laurance3EFFECTS OF SMALL ARMS MISUSEWilliam Godnick, Edward J. Laurance, Rachel Stohl, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong> Survey10GUNS IN CRIMENicolas Florquin21FOLLOWING THE TRAIL:PRODUCTION, ARSENALS, AND TRANSFERS OF SMALL ARMSAnna Khakee <strong>and</strong> Herbert Wulf26MEANS AND MOTIVATIONS:RETHINKING SMALL ARMS DEMANDRobert Muggah, Jurgen Brauer, David Atwood, <strong>and</strong> Sarah Meek31CONTRIBUTORS39

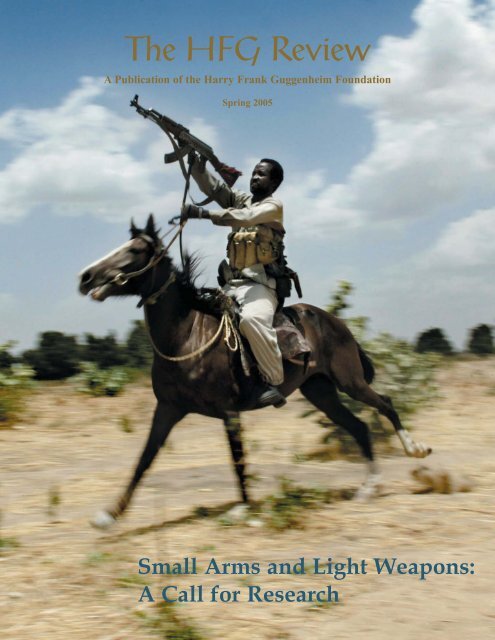

<strong>Weapons</strong> of Mass DestructionJoel WallmanVery few of today's armed conflicts take placebetween armed forces of different states. Rather,most such violence occurs within states. The strategyof armed groups in these conflicts involvesdeliberate targeting of civilians, <strong>and</strong> most of thesecasualties, as well as those of the combatants, areinflicted with small arms <strong>and</strong> light weapons—instruments wielded by one or two people, such aspistols, rifles, <strong>and</strong> mortars. The small-arms problemhas not received anything like the academicattention devoted to the problem of nuclear proliferation,perhaps because, given the ubiquity <strong>and</strong>quotidian nature of these weapons, they do notengender the anxiety of atomic devices. Thus far,however, the human toll of small arms <strong>and</strong> lightweapons far exceeds that from nuclear, chemical,or biological weapons. The <strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong> Survey, aresearch organization that issues annual reportsbased on meticulous research, estimates that300,000 people are killed each year with theseweapons, around one-third in group conflicts <strong>and</strong>the others from homicide or suicide by firearm.And, of course, a much larger number of victims ofsmall arms survive their injuries but live on withgrievous damage. In their aggregate effects, theseare proven weapons of mass destruction.<strong>Small</strong> arms <strong>and</strong> light weapons can potentiate aspiral of lawlessness. Weak states allow their proliferation,<strong>and</strong> acquisition of arms allows formerlypowerless groups to challenge authority, furtherweakening it. The abundance of arms in the h<strong>and</strong>sof nonstate actors means that new wars can readilybe started. In the case of pre-existing conflicts, theinflux of weapons exacerbates the violence, asfirearms are intrinsically more deadly than othersmall weapons. It is true that much of the 1994killing in Rw<strong>and</strong>a was conducted with machetes,but the scale of the carnage in such a short timecould not have been achieved without the massiveavailability of rifles, grenades, <strong>and</strong> similar weaponsused to round up <strong>and</strong> terrorize the victims.The problem is by no means just one of insurgentgroups besieging legitimate governments,however. Among the worst abusers of small armsare repressive governments <strong>and</strong> their paramilitaryadjuncts, such as the janjaweed militia of Sudan,who, in concert with government forces, have beencommitting atrocities of genocidal proportion inDarfur.There are other effects of the spread of theseweapons, none of them good. In today's substateconflicts, anyone can become a combatant byacquiring a weapon, <strong>and</strong> participants in these warstend to be less constrained in whom they targetthan traditional soldiers. As a result, humanitarianagencies, which strive to reduce the impact of waron civilians, have become increasingly reluctant tosend their people into conflict areas. The acquisitionof weapons by young men, especially boys,inverts traditional authority relations, placingpower in the h<strong>and</strong>s of people who, not havingknown it before, are perhaps more reluctant to disarmthan would be their elders. And, more generally,the likelihood of adherence to a peace agreementis much lower when large numbers of militantsremain armed.Many organizations have taken up the cause ofstemming the illicit flow of small arms, but, torepeat, only a modest effort has been devoted thusfar to systematic research on the nature of thisproblem: the diversion of arms from the legitimateto illicit market, the role of small arms in the out-1

<strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong> Research:Where We Are <strong>and</strong> Where We Need to GoEdward J. LauranceIntroductionIn the early 1990s, there was great hope throughoutthe world for a decline in the wars, insurgencies,<strong>and</strong> threats from weapons of mass destructionthat marked the Cold War. With the breakup ofthe Soviet Union, we saw a precipitous decline inmilitary spending by the major powers, the endingof several wars fueled by Cold War rivalries (e.g.,Mozambique, Nicaragua, El Salvador), <strong>and</strong> renewedinterest in the principles of the UN Charter<strong>and</strong> legal instruments controlling weapons of massdestruction.These hopes were soon dashed as intrastate conflicts,some new, others held in check by the superpowersduring the Cold War, began to flare up intoarmed violence. While the root causes of theseconflicts were familiar <strong>and</strong> quickly identified,something new had emerged that caught the worldunprepared for solving these conflicts. They werebeing fought almost exclusively with small arms<strong>and</strong> light weapons—assault rifles, rocket propelledgrenades, <strong>and</strong> similar tools of violence not previouslyaddressed or studied by those charged withcontrolling armed violence. 1•In 1994 Mali, a civil war between the Touregminority <strong>and</strong> the rest of the country resulted inthe wide availability of arms in society. The ensu-3

ing instability <strong>and</strong> violence brought all developmentprojects to a halt.• In El Salvador, a UN-brokered peace hadbrought a vicious civil war to a close in 1992. Butby 1995 the country was ablaze with armed violence,this time by criminals armed with morethan 200,000 military weapons left over from thecivil war.• In Rw<strong>and</strong>a, more than 800,000 Tutsis <strong>and</strong> manyHutus were massacred at the direction of theHutu government, made possible by the distributionof weapons brought into the country forthis purpose.• In Sri Lanka, an intractable civil war raged, withthe government facing a Tamil insurgency thathad established a global network of illicit armssupplies.• In the former Soviet Union, states with only armsindustries left as viable commercial enterpriseslegally sold hundreds of thous<strong>and</strong>s of small arms<strong>and</strong> light weapons to governments involved inconflicts, many of which were illegally diverted toarmed groups bent on perpetuating conflicts.Ten years after the small arms problem burstonto the world stage, there is a clear consensus thatit is key to the underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>and</strong> control of contemporaryviolence. The proliferation <strong>and</strong> misuseof small arms <strong>and</strong> light weapons (SALW) occurs ina variety of contexts: receding conflict, post-conflict,<strong>and</strong> high-crime areas. Today there are over600 million SALW in circulation worldwide. Of49 major conflicts in the 1990s, 47 were wagedalmost exclusively with small arms. <strong>Small</strong> arms areresponsible for hundreds of thous<strong>and</strong>s of deathsper year, including 200,000 from homicides <strong>and</strong>suicides <strong>and</strong> perhaps 300,000 from political violence.A wide range of negative consequences fromtheir use has been revealed: deaths <strong>and</strong> injuries toinnocent civilians, human rights violations, denialof socio-economic development; sparking, fueling,<strong>and</strong> prolonging conflicts; obstruction of humanitarianrelief programs; undermining of peace initiatives;diminishing the security of vulnerablegroups such as women, children, refugees, <strong>and</strong>internally displaced persons; <strong>and</strong> increasing thepublic health burden from violence.A Research Field EmergesAs this reality emerged in the mid-1990s, so didthe need for information <strong>and</strong> knowledge aboutthese weapons. Why? As a class these weapons <strong>and</strong>their effects are very different from larger conventionalweapons. They are smaller, more portable,cheaper, simpler to use, <strong>and</strong> easily available to nonstateactors. What we knew about the trade <strong>and</strong>production of larger weapons such as tanks <strong>and</strong>fighter aircraft was hardly enough to provide guidanceto policymakers. The research questionsregarding small arms went far beyond traditionalnational <strong>and</strong> international security, which concernedonly the state.The goal of this publication is to provide anintroduction to the research field of small armsthat emerged as a result of this new reality. To date,this work has been primarily policy research,designed for <strong>and</strong> produced by nongovernmentalorganizations (NGOs), international governmentalorganizations (IGOs), <strong>and</strong> national governmentsinvolved in addressing this problem. This researchhas focused on practical policy variables <strong>and</strong> developing<strong>and</strong> testing programs, interventions, <strong>and</strong>services. As a result, program-evaluation methodologiestend to have an important place in thefield. This policy research has also been characterizedby strict time constraints, placed on researchersby donor governments <strong>and</strong> international organizationsactive in seeking policy solutions. 2The academic community was rarely engaged indebate about these policies or in systematic testingof practices enacted to stem the flow of small arms.The time has come to enlist the full range of academicdisciplines to exp<strong>and</strong> the knowledge baseneeded to reduce the damage wrought by small4

arms <strong>and</strong> light weapons.The initial research agenda was set by a resurgentUnited Nations, which had sent out anunprecedented number of peacekeeping missionsafter the end of the Cold War. Responding to UNSecretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali's 1995warning of this new global threat, a UN panel ofexperts was formed to investigate the types of smallarms <strong>and</strong> light weapons actually being used in conflicts,the nature <strong>and</strong> causes of their accumulation,transfer, production, <strong>and</strong> trade, <strong>and</strong> the ways <strong>and</strong>means to prevent <strong>and</strong> curb their negative effects.This research led to the UN Conference on<strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong> in July 2001, the goal of which was todevelop a “Programme of Action” to guide thepolicies of governments <strong>and</strong> regional <strong>and</strong> internationalorganizations. 3 It was underst<strong>and</strong>able thatthe knowledge being developed was shaped by thegoal of having maximal impact on the formulationof the Programme of Action. 4At this time there was a general recognition thatacademic research on small arms was lacking. Inresponse, the <strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong> Survey (SAS) was formedin Geneva in late 1999 as an independent researchcenter on the issue of small arms. After four yearsof work by SAS <strong>and</strong> other policy research centers, 5an initial set of propositions, hypotheses, <strong>and</strong> datahas emerged that now needs to be investigatedusing the full range of scholarly research methods.Policy research has raised a number of questions<strong>and</strong> hypotheses that need to be tested by those lessconstrained by the dictates of a policy communitywhose first priority is solving the problem now.For example, very little statistical analysis of thegrowing volume of survey data has taken place.The small arms problem needs research that ismore replicable, cumulative, <strong>and</strong> testable by peerreview. The purpose of this publication is to stimulatesuch work.The articles that follow summarize what we knowabout each major aspect of the small arms problem<strong>and</strong> the questions that remain to be investigated.production, transfers, <strong>and</strong> trafficking ofsalwKnowing the scope of production is a core elementin predicting the types <strong>and</strong> numbers ofweapons in future circulation. If one is trying tostop the supply of weapons to conflict zones, it isimportant to know the source of this supply. Inthe 1990s, policymakers sought to use arms controltechniques that applied to larger weapons systems,such as tanks <strong>and</strong> aircraft. They went after producersof these weapons, only to discover that newproduction of small arms was actually declining.The major source of supply was existing stockpilesor weapons circulating from previous wars. Moregenerally, underst<strong>and</strong>ing how arms are acquired byprivate citizens, official security forces, criminals,<strong>and</strong> insurgent groups requires knowledge about theactors (governments, brokers, transport agents)<strong>and</strong> legal <strong>and</strong> illegal modes of transfer (export criteria,end-user certificates, illicit trafficking networks)involved in distribution.impacts of salwUnderst<strong>and</strong>ing the effects of small arms in <strong>and</strong>on societies goes to the heart of the motivation forsmall arms research: what harm is caused by theproliferation <strong>and</strong> misuse of these weapons, who ismost affected by them, <strong>and</strong> what are the circumstancesunder which they cause harm? Researchgoes beyond deaths <strong>and</strong> injuries to individuals toinclude the full range of impacts on societies.role of salw availability in outbreak <strong>and</strong>exacerbation of armed conflictIn Rw<strong>and</strong>a, El Salvador, Kosovo, Brazil, <strong>and</strong>many other places, small arms <strong>and</strong> light weaponswidely available or supplied to an area of conflict<strong>and</strong> tension can spark the rise of armed violence.What are the dynamics of this process of escalation?Also important is the effect that the (mis)useof these weapons during armed conflict can haveon civilians, often in violation of human rights <strong>and</strong>5

international humanitarian law. Does the presenceof SALW exacerbate or lengthen armed conflict?dem<strong>and</strong> for small armsAnalyzing dem<strong>and</strong> for small arms involvesexamining who possesses <strong>and</strong> carries them, whattypes are acquired, <strong>and</strong> the motivations for acquiringthem. Knowledge of dem<strong>and</strong> is important inthe design of programs intended to address thenegative effects of these weapons, e.g., demobilization,disarmament, <strong>and</strong> reintegration (DDR) of excombatants,as well as programs for collection <strong>and</strong>destruction of weapons.international efforts at controlThe 2001 UN Programme of Action on <strong>Small</strong><strong>Arms</strong>, <strong>and</strong> various regional treaties <strong>and</strong> frameworks,have been developed to address the globalproblems associated with small arms <strong>and</strong> lightweapons. Evaluation research has been conductedto assist in monitoring <strong>and</strong> evaluating these collaborativeefforts. Such treaties <strong>and</strong> protocols shouldbe compiled into a database to avoid duplication<strong>and</strong> promote complementarities <strong>and</strong> synergies.design <strong>and</strong> evaluation of practical policies<strong>and</strong> programsA significant amount of research has been conductedon the programs designed to alleviate thenegative effects of small arms. Much of it is classicprogram evaluation, with a focus on evaluatingneeds assessment, goals <strong>and</strong> objectives of the program,program design, implementation, <strong>and</strong> impact.Compilation of “lessons learned” <strong>and</strong> “bestpractices” is the typical outcome of this research.Most of this work has focused on the followingtypes of programs:• Disarmament, demobilization, <strong>and</strong> reintegration(DDR) of ex-combatants• Amnesties <strong>and</strong> weapons collection• Destruction of surplus weapons• Increasing public awarenesssmall arms <strong>and</strong> crimeAs mentioned, small arms take an estimated200,000 lives each year outside of group conflictthrough homicide <strong>and</strong> suicide, as well as inflictinga much greater number of grievous injuries. Theyalso facilitate the commission of millions of crimesof other types, including robbery, assault, <strong>and</strong> sexualoffenses.By contrast with the other domains of inquirysurveyed above, there is an abundant literature onthe role of small arms in crime, most of it pertainingto the United States, Canada, Australia, <strong>and</strong>the United Kingdom. Research on the causes,effects, <strong>and</strong> costs of gun violence has an especiallylong history in the United States. This is also truefor the dem<strong>and</strong> question, as well as the evaluationof policy <strong>and</strong> program interventions designed tolessen these harms. There are academic journalsdevoted to this research, well-established researchcenters, <strong>and</strong> vigorous debates among scholars onthese issues. Such is not the case with research onthe global small arms problem. The challenge is toget this academic community, mainly although notexclusively in the United States, to test the applicabilityof this body of research to small arms problemsoutside the United States.Integrating Salw Research intoLarger IssuesThe research effort on small arms, as indicatedabove, has had a clear link to policies <strong>and</strong> programsdesigned to prevent <strong>and</strong> reduce the damagewrought by these weapons. Given the lack ofinformation on small arms at the start of the policyprocess in the mid-1990s, much of the initialresearch was necessarily technical <strong>and</strong> descriptivein nature: characteristics of weapons, who wasusing them <strong>and</strong> where, how legal transfers turnedinto illicit ones, etc. In concentrating on theinstrumentalities or tools of violence, researchers6

tended to become “small arms experts.”Once the UN Programme of Action was agreedupon in 2001, the research began to shift towardintegrating or “mainstreaming” small arms knowledgeinto larger issues. A very good example is therecent move toward linking small arms policyresearch with the general field of internationaldevelopment. Scholars in development studiesseek to formulate models of development, determineeffective modes of delivering assistance, <strong>and</strong>identify the various obstacles to development. Asdiscussed in the following pages, one of the majorobstacles plaguing the delivery of assistance,indigenous capacity-building, <strong>and</strong> post-conflictreconstruction is armed violence <strong>and</strong> insecurityresulting from the prevalence of small arms <strong>and</strong>light weapons. There is a natural synergy herebetween the development <strong>and</strong> small arms researchcommunities that is only now beginning to be recognized.Within the small arms group, a consensusis emerging as to the various impacts of smallarms on the development process. 6 However,development researchers <strong>and</strong> small arms researchersrarely engage each other. The importance ofrecognizing the nexus of security <strong>and</strong> developmenthas become particularly urgent given the difficultieswith post-conflict reconstruction in Iraq,Afghanistan, <strong>and</strong> Kosovo, among other places.There are other fields of research where the data<strong>and</strong> findings of small arms research could provevaluable. This has already begun to occur in genderstudies. Another fruitful area is justice <strong>and</strong>security sector reform, a major issue in post-conflictnation-building contexts. As of yet, however,the justice reform element of this work has notlinked with the small arms effort. Questions to beaddressed: Have codes of conduct of legitimatelyarmed persons (police/military) regarding the useof arms been implemented? Have gun laws beenchanged? Are the legal <strong>and</strong> penal systems capableof dealing with those accused of gun crimes,including law-enforcement personnel? 7ConclusionSALW research covers a wide range of issues thatlink small arms proliferation <strong>and</strong> misuse to a hostof negative effects. This work has been shaped bya policy agenda requiring basic data on small arms<strong>and</strong> a focus on what can be done to reduce <strong>and</strong> preventthe damage they cause. There are now sufficientempirical data <strong>and</strong> hypotheses ripe forengagement by the wider academic community.We hope that these articles, by distilling downthe literature <strong>and</strong> emphasizing what “needs knowing,”will contribute to an increase in the quantity<strong>and</strong> quality of small arms research. We also hopeto encourage a wider set of academic disciplines toaddress the questions that will move us closer tosolving the problems posed by small arms.Sources for Research on <strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong>centre for humanitarian dialoguehttp://www.hdcentre.org/?aid=37The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue is anNGO with a <strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong> <strong>and</strong> Human SecurityProgram. They conduct research related to thehuman cost of small arms availability <strong>and</strong> misuse.international action network on small armshttp://www.iansa.orgThe International Action Network on <strong>Small</strong><strong>Arms</strong> is the global network of civil society organizationsworking to stop the proliferation <strong>and</strong> misuseof small arms <strong>and</strong> light weapons. Founded in1998, IANSA has grown rapidly to more than 500participant groups in nearly 100 countries. Its portalsinclude key issues, resources <strong>and</strong> publications,events <strong>and</strong> campaigns, <strong>and</strong> a women's portal.international alerthttp://www.international-alert.org/publications.htmInternational Alert is an independent internationalNGO that works to help build lasting peacein countries <strong>and</strong> communities affected or threatenedby violent conflict. They have regional pro-7

grams in Africa, the Caucasus, <strong>and</strong> Central, South,<strong>and</strong> South East Asia. They conduct policy analysis<strong>and</strong> advocacy at government, EU, <strong>and</strong> UN levelson cross-cutting issues such as business, humanitarianaid <strong>and</strong> development, gender, security, <strong>and</strong>religion in relation to conflict. They are part of theBiting the Bullet collaborative <strong>and</strong> have conducteda significant amount of independent research onsmall arms issues.norwegian initiative on small armshttp://www.nisat.orgNISAT is based at the Peace Research Institute,Oslo. It maintains a database of small arms transferscontaining over 250,000 records. Its BlackMarket Archive contains over 7,000 searchabledocuments. It also maintains a West Africa newsarchive.saferworldhttp://www.saferworld.org.uk/iac/index.htmSaferworld is a large transnational NGO thatworks with governments <strong>and</strong> civil society internationallyto research, promote, <strong>and</strong> implement newstrategies to increase human security <strong>and</strong> preventarmed violence. They are a member of the researchcollaborative called Biting the Bullet, which hasproduced a series of papers on all aspects of thesmall arms problem <strong>and</strong> what to do about it.small arms nethttp://www.smallarmsnet.orgThe Institute for Security Studies in Pretoria hasestablished the <strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong> Net, an informationportal for groups <strong>and</strong> individuals working to containthe proliferation of small arms <strong>and</strong> lightweapons in Africa. An initiative of the <strong>Arms</strong>Management Programme (AMP), it is an informationhub for small arms <strong>and</strong> arms related issuesaffecting the continent.small arms surveyhttp://www.smallarmssurvey.orgBeginning in 2001, <strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong> Survey, throughOxford University Press, has published an annualsurvey of the field. Some of the chapter themes arerecurrent (e.g., products, producers, stockpiles,transfers, controls), which serves to update readerson these topics. In addition, each year SAS introducesnew aspects of the field. Topics haveincluded arms brokers, the UN 2001 <strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong>Conference <strong>and</strong> Programme of Action, weaponscollectionprograms, effects of small arms onhuman development, regional <strong>and</strong> country-specificcases, <strong>and</strong> human rights. SAS also produces occasionalpapers <strong>and</strong> reports.un department of disarmament affairs:conventional arms branch: small arms <strong>and</strong>light weapons portalhttp://disarmament2.un.org/cab/salw.htmlThis web site is an authoritative source for allUN action <strong>and</strong> documents since the small armsissue entered onto the world stage in the mid-1990s.un development programme: small arms<strong>and</strong> demobilization divisionhttp://www.undp.org/bcpr/smallarms/index.htmAssists countries recovering from conflict to curtailillicit weapons, address the needs of ex-combatants<strong>and</strong> other armed groups through alternativelivelihood <strong>and</strong> development prospects, <strong>and</strong>build capacities at all levels to promote humansecurity.Notes1. The 1997 Report of the United Nations Panel ofGovernment Experts on <strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong> provides the mostwidely accepted definition of small arms <strong>and</strong> lightweapons. This distinguishes between small arms, whichare weapons designed for personal use, <strong>and</strong> lightweapons, which are designed for use by several personsserving as a crew. The category of small arms includes8

evolvers <strong>and</strong> self-loading pistols, rifles <strong>and</strong> carbines,assault rifles, sub-machine guns, <strong>and</strong> light machineguns. <strong>Light</strong> weapons include heavy machine guns,h<strong>and</strong>-held under-barrel <strong>and</strong> mounted grenade launchers,portable anti-tank <strong>and</strong> anti-aircraft guns, recoillessrifles, portable launchers of anti-tank <strong>and</strong> anti-aircraftmissiles, <strong>and</strong> mortars of calibers less than 100mm. Seehttp://www.smallarmsnet.org/definition.htm.2. Colin Robson. Real World Research. Oxford:Blackwell Publishers, 2002.3. For a summary of this conference <strong>and</strong> the text ofthe Programme of Action, see the web site of the UNDepartment of Disarmament Affairs: http://disarmament2.un.org/cab/salw.html.4. An example of this research can be found in theBiting the Bullet series of publications at http://www.saferworld.org.uk/publications/int_arms_control.htm.5. Major examples include United Nations Institutefor Disarmament Research (UNIDIR), Bonn InternationalCenter for Conversion (BICC), Institute forSecurity Studies in Pretoria, Bradford University,International Alert, Center for Defense Information,Human Rights Watch, OXFAM, Peace ResearchInstitute of Oslo (PRIO), UN Development Programme(UNDP), UNICEF, Monterey Institute ofInternational Studies, Saferworld.6. See http://www.smallarmssurvey.org/Yearbook%202003/ch4_Yearbk2003_en.pdf.7. For research questions <strong>and</strong> the state of the researchin this field, see “Critical Triggers: ImplementingInternational St<strong>and</strong>ards for Policing Firearms Use,” pp.213-247 in <strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong> Survey 2004. Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press.Kalashnikov productionat Arsenal Co. inBulgaria. <strong>Weapons</strong>from plants in formercommunist countriesturn up frequently inillicit arms transfers.9

Effects of <strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong> MisuseWilliam Godnick, Edward J. Laurance, Rachel Stohl, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong> SurveyIntroductionIn 1994 the impoverished nation of Mali waswracked with violence. <strong>Small</strong> arms <strong>and</strong> lightweapons had become readily available, turninggrievances by the economically marginalizedToureg into armed violence so pervasive that alldevelopment work in Mali had come to a halt.Donor countries pulled out, <strong>and</strong> the scuttling oftheir development projects resulted in half-builtschools, contaminated water supplies, <strong>and</strong> unfinishedroads. The president of Mali formally askedthe United Nations to assist his country in tacklinga problem heretofore unaddressed in internationalaffairs, the proliferation <strong>and</strong> misuse of small arms<strong>and</strong> light weapons.When the global community first engaged theissue of small arms <strong>and</strong> light weapons (SALW) inthe 1990s, it was the terrible effects of theseweapons in places such as Mali that were the primemover for research <strong>and</strong> action. Documenting theseeffects was a crucial first step toward developingpolicies to address the problem, since most of theweapons involved initially had a legitimate role inthe internal <strong>and</strong> external security of sovereignstates, yet governments were underst<strong>and</strong>ably reluctantto formally recognize that there were unintendedeffects from these weapons. The result wasa set of papers, produced mainly by the policy <strong>and</strong>advocate communities, intended to demonstratethe need to focus on the instruments of violence.Most of these initial reports were stories or anecdotesgathered by NGOs with firsth<strong>and</strong> experienceof the effects of small arms. 1Once the policy <strong>and</strong> advocacy materials definedthe problem, it was natural that more in-depthresearch would soon follow. Underst<strong>and</strong>ing thesocietal <strong>and</strong> individual effects of small arms is themotivation for this research: we want to knowwhat harm small arms cause, who is most affectedby them, <strong>and</strong> the circumstances under which theseweapons cause harm.Direct Effectsdeaths, injuries, <strong>and</strong> disabilitiesDirect effects of small arms occur as deaths,injuries, <strong>and</strong> disabilities, as well as direct costs thatresult from the treatment of injuries <strong>and</strong> disabilities.In addition, there are the costs to society oflost working days resulting from treatment, prematuredeath, or disability.Studies in the United States in particular, <strong>and</strong> toa lesser extent in other Western societies, have providedan underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the significance offirearms in suicide <strong>and</strong> homicide rates by comparingfirearms with other means of killing.Suicides by firearm: It has been documented formany Western societies that the availability of civilianfirearms influences the percentage of suicidescommitted with a firearm. This is partly explainedby the higher suicide completion rates for suicidesthat are attempted with a gun as compared toattempted suicides that make use of other means.Completed suicide rates appear to be higher forgroups that are more prone to impulsive actions,such as youths, when they have easy access to afirearm. However, it remains debatable whetheroverall suicide rates increase as a result of elevatedarms availability. Nor is great firearms prevalencenecessary for a high suicide rate. Japan suffersfrom very high suicide rates but has one of the lowestrates of civilian arms availability in the world.Domestic firearm deaths: In the US there is evi-10

dence that rates of domestic murder are positivelycorrelated with rates of firearms ownership.However, research has also shown that firearmownership rate is only one of several variables thatinfluence fatal domestic violence. Unemployment<strong>and</strong> abuse of alcohol <strong>and</strong> drugs have also beenshown to be significant.Our underst<strong>and</strong>ing of patterns in firearmsdeaths around the world is still patchy. It is oftenstated that the majority of SALW victims are men,<strong>and</strong> in particular young men. However, in relationto political conflicts it is often stated that a majorityof victims are civilians, largely women <strong>and</strong> children.While there is a significant volume ofresearch on categories of victims in the UnitedStates, information on other societies is more limited.Therefore, studies that provide a detailedbreakdown of firearm victims by gender, age, ethnicity,<strong>and</strong> locality in different societies are neededto develop a nuanced picture of who is most at risk<strong>and</strong> who should be the focus of intervention programs.There is evidence that the rate of suicides committedwith firearms can be used as a proxy forcivilian gun ownership rates. However this observationis based on research in Western societies.Further work is needed to validate this assumptionfor non-Western societies.Most work considering the direct effects offirearms use has concentrated on death <strong>and</strong> physicalinjury. These, however, don't exhaust the consequences.terror, intimidation, <strong>and</strong> other psychologicaleffectsHuman rights activists have pointed to the useof firearms in coercion <strong>and</strong> intimidation. Besidesdocumenting individual stories of human rightsabuses, there has been very little research to datethat would help us to underst<strong>and</strong> how guns areused to threaten rather than kill. Similar work hasbeen conducted on the criminal use of guns, but todate little concentrating on the effects of gun use insystematic state violations of human rights.particular vulnerability of children <strong>and</strong>womenChildrenWhile it is obvious that small arms negativelyaffect the lives of children, it was really not untilthe lead-up to the UN 2001 Conference that thefull effects of small arms on the welfare of childrenwere documented. UNICEF drew attention to theissue in their pre-conference <strong>and</strong> conference statement,<strong>and</strong> a comprehensive NGO study on theimpacts of small arms on children was released forthe conference. 2Such studies have provided data about the victimizationof children by small arms violence. InColombia in 1999, children were victims of 1,333homicides, 58 accidents, <strong>and</strong> 16 suicides in whichsmall arms were used. Between 1987 <strong>and</strong> 2001, 467children died in the Israel-Palestine armed conflictas a result of gun-related violence, while 3,937 childrenwere killed by firearms in the state of Rio deJaneiro during the same four-year span.From these early studies we know that childrenare victims of conflict <strong>and</strong> small arms misuse, thatsmall arms proliferation <strong>and</strong> misuse interfere withthe provision of basic needs <strong>and</strong> services, <strong>and</strong> thatsmall arms make child soldiering more possible<strong>and</strong> more probable. We have good case studies butthere is still much we don't know. There is nothorough data-collection process that transcendsnational borders <strong>and</strong> experiences to quantify theimpact of small arms on children.WomenWomen are another of the groups most vulnerableto small arms violence, <strong>and</strong> a significantamount of work is now being conducted on therelationship between gender <strong>and</strong> small arms. It iswell established that legal guns are just as dangerousto women as illegal ones. There is abundant11

evidence that sexual violence at gunpoint is used asa weapon of war. To name but a few cases, inAfghanistan, Sudan, the Democratic Republic ofCongo, <strong>and</strong> the former Yugoslavia, women <strong>and</strong>young girls have been abducted from their homes,schools, <strong>and</strong> places of work at the barrel of a gun.This practice persists in the aftermath of armedgroup conflict.Women are not just the victims of gun violence,however. They may also participate as combatants<strong>and</strong> in support roles, providing information, food,clothing, <strong>and</strong> shelter, as well as bearing the longtermburden of caring for the sick <strong>and</strong> injured.increased potential for violations ofhuman rights <strong>and</strong> internationalhumanitarian lawHuman RightsThere is a prodigious body of scholarship onhuman rights <strong>and</strong> an increasing amount concerningthe use of small arms to violate internationallyrecognized human rights. Much of this work hasbeen done by organizations such as Human RightsWatch, Amnesty International, <strong>and</strong> other nongovernmentalorganizations evaluating the humanrights records of small arms recipient countries.Amnesty International has a recent publication forthe Control <strong>Arms</strong> campaign examining effectivemechanisms for police to use in controlling theseweapons without themselves misusing them.Research to date has demonstrated that small armsin the wrong h<strong>and</strong>s (both governmental <strong>and</strong> nongovernmental)lead directly to human rightsabuses, including extrajudicial executions, forceddisappearances, <strong>and</strong> the general repression of individuals<strong>and</strong> groups.<strong>Small</strong> arms were effective tools of terror, used tokill, maim, rape, <strong>and</strong> forcibly displace people ingenocides <strong>and</strong> mass attacks on civilians in Bosnia,Rw<strong>and</strong>a, the Democratic Republic of Congo, <strong>and</strong>Sudan. Even where they are not the primarymeans of killing, weapons capable of massivelethality—automatic rifles, grenades, rocketlaunchers—can serve to corral victims so that theycan be killed with cheap <strong>and</strong> crude weapons suchas machetes. In addition, small arms have beenused to forcibly recruit <strong>and</strong> arm children to serve assoldiers in dozens of countries around the world.<strong>Small</strong> arms proliferation facilitates rights violationsoutside of conflict situations. Governmentforces may misuse small arms in violation of theUN Basic Principles on the Use of Force <strong>and</strong>Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, as hasbeen the case, for example, in Ethiopia, whenpolice have used excessive force against studentprotesters.In April 2003, the United Nations appointed anexpert on human rights <strong>and</strong> small arms to investigatethe link between them. This research <strong>and</strong>other work in the area will focus on the need foradditional principles <strong>and</strong> norms <strong>and</strong> elevate to theglobal intergovernmental level violations of humanrights directly linked to small arms proliferation<strong>and</strong> misuse.International Humanitarian LawThe use of conventional weapons, includingsmall arms, in armed conflict falls under the jurisdictionof international humanitarian law (IHL),as embodied in a variety of international agreements,including the 1907 Hague Conventions, the1949 Geneva Conventions, the 1977 Protocols Additionalto the Geneva Conventions, <strong>and</strong> the 1980UN Convention on Conventional <strong>Weapons</strong>. Theseagreements are designed to protect civilians <strong>and</strong> preventunnecessary suffering during times of conflictby limiting both the physical means <strong>and</strong> the methodsthat belligerent parties can use to wage war.The deliberate targeting of civilians, indiscriminateforce that is likely to harm civilians, <strong>and</strong> the use ofweapons <strong>and</strong> tactics that are indiscriminate by theirnature or excessively injurious to combatants areprohibited by these agreements.Just as small arms can be used to violate humanrights law, which applies mainly to nonwar con-12

texts, small arms can also contribute to violationsof IHL, which applies to situations of inter- <strong>and</strong>intrastate war. All types of armed groups, whethergovernment or guerrilla forces, have used smallarms for IHL violations. <strong>Small</strong> arms have beenused for summary executions in Liberia <strong>and</strong> tocommit massacres in Colombia. In Sri Lanka,children have been forcibly recruited at the barrelof a gun. Civilian property has been looted inAfghanistan <strong>and</strong> forced disappearances haveoccurred in Chechnya.Violations of IHL have been more frequent insome conflicts because armed groups are purposefullytargeting civilians <strong>and</strong> aid workers as part oftheir strategy. The culture of impunity that allowssuch atrocities needs further study. How does thisimpunity prolong armed conflicts <strong>and</strong> make themmore intractable? How do the st<strong>and</strong>ard tactics <strong>and</strong>operating procedures of organized military forceslead to violations of IHL? Since currently there areonly inadequate measures to address the irresponsibletransfer of weapons to areas where their misuseis foreseeable, we must also consider whethergovernments authorizing such transfers are fulfillingtheir obligation to “respect <strong>and</strong> ensure respect”for the basic protections established by IHL.threats to humanitarian interventionThe widespread availability of small arms hasincreased the duration, incidence, <strong>and</strong> lethality ofarmed conflict, where, since the end of the ColdWar, the “average” conflict has lasted eight years.<strong>Small</strong> arms have made it more difficult for humanitarianrelief to be delivered as aid workers arespecifically targeted for extortion, threat, theft,rape, <strong>and</strong> murder. For example, on March 28,2003, a Red Cross worker in Afghanistan was singledout from his Afghan companions <strong>and</strong> killed ata roadblock. The risk of violence can limit accessto populations in need of assistance <strong>and</strong> divertresources to security rather than relief provision,even though IHL requires that aid agencies haveaccess to populations that need humanitarian assistance.Approximately 50 percent of populations inconflict regions live in areas that are not accessibleto relief campaigns due to security threats. In somecountries it has become too expensive, both inhuman lives <strong>and</strong> cash, for outsiders to providemuch-needed aid, forcing populations to endurethe horrors of war alone. The danger to aid <strong>and</strong>relief workers from small arms has been documentedin a ground-breaking study by the <strong>Small</strong><strong>Arms</strong> Survey <strong>and</strong> the Centre for HumanitarianDialogue, In the Line of Fire. Ten percent ofrespondents from relief organizations reported havingbeen the victim of a “security incident,” such asassault, intimidation, or sexual violence, in the previoussix months. Forty percent of these encountersinvolved a weapon.Even when aid workers can supply relief, it isoften difficult to reach the needy populations. Atthe end of 2002, there were approximately 12 millionrefugees, 5.3 million internally displaced persons(IDPs) still away from their homes, <strong>and</strong>941,000 asylum seekers. Refugees <strong>and</strong> IDPs areoften afraid to leave camps <strong>and</strong> return to theirhomes or to venture out of safe areas to acquirerelief supplies. At the same time, refugee <strong>and</strong> IDPcamps often become militarized, <strong>and</strong> their vulnerablepopulations are subject to intimidation, rape,injury, forced prostitution, <strong>and</strong> slavery as well asforced recruitment into armed service.Some research on refugee camps being used asarms trafficking sites has begun. But we need toknow much more about both the levels of suchphenomena <strong>and</strong> their impact on underserved populations.outbreak of intergroup violenceIt is clear that small arms exacerbate <strong>and</strong> perpetuateintergroup violence, but does the buildup <strong>and</strong>acquisition of small arms <strong>and</strong> light weapons actuallylead to the outbreak <strong>and</strong> escalation of armedconflict? This was a crucial question for those who13

The importation of weaponry to regions of conflict perpetuatesviolence, impedes peacekeeping <strong>and</strong> development efforts,<strong>and</strong> undercuts the ability of the parental generation to socializeyouth.pushed the small arms problem onto the globalstage in the mid-1990s. Laurance, surveying theevidence, concluded that “while it is true that peoplebent on killing each other will do so regardlessof the weapons they possess, it is also true that acritical mass of weapons can be the impetus forstarting a major conflict.” 3Two case studies that received much attentionshaped the early response to this question.Researchers from Human Rights Watch arguedthat all four phases of the Rw<strong>and</strong>a conflict of the1990s—the invasion of Rw<strong>and</strong>a by Tutsi exiles, thediffusion of weapons to Hutus within Rw<strong>and</strong>a, thegenocide itself, <strong>and</strong> the raids by Hutu militia afterbeing expelled—were possible only because of thesupply of small arms <strong>and</strong> light weapons. 4 The secondcase pointing to the direct effect of armsbuildups on the outbreak of armed violence isKosovo. In 1997 the government of Albania collapsed<strong>and</strong>, in the subsequent instability, its significantarsenal of small arms <strong>and</strong> light weapons waspillaged. More than half of these weapons left thecountry, <strong>and</strong> many wereacquired by the KosovoLiberation Army (KLA).A very tense situation inKosovo, a province ofSerbia in which 1.7 millionethnic Albanians,though a majority, livedunder the domination of200,000 Serbs, very soonexploded into armed violence.The massive acquisitionof arms did notcreate the KLA's willingnessto use violence, butit did give them the meansto do so on a broad scale. 5The most comprehensivestudy of the impactof small arms <strong>and</strong> lightweapons on the outbreak <strong>and</strong> escalation of conflict,<strong>Arms</strong> <strong>and</strong> Ethnic Conflict, concludes that “armsaccumulation by ethnic groups or in conflict zonesseems a relatively good predictor of impending violence.”6 The authors regard their findings as preliminary,however, <strong>and</strong> call for research to clarifythe impact of weapons on governments' <strong>and</strong> ethniccommunities’ opportunity <strong>and</strong> willingness toemploy violence in pursuit of their goals:• Under what circumstances do arms produce orcontribute to the initiation of conflict? What arethe early warning indicators involving SALWthat could be used to better predict the outbreakof violence? 7• In what ways might arms fuel ongoing violence?• Do arms flows facilitate or hinder efforts toresolve ethnopolitical violence <strong>and</strong> conflict?• What is the effect of arms infusions on the likeli-14

hood <strong>and</strong> success of third-party efforts to resolvea conflict? 8Indirect EffectsDevelopment studies have identified the indirecteffects of small arms by pointing to the linkbetween SALW <strong>and</strong> instability <strong>and</strong> insecurity,which, in turn, are seen as responsible for a numberof socioeconomic effects (reduced productiveeconomic activities, limited possibilities for education,malfunctioning health structures) that hindera nation's or community's development. In addition,public health experts have documented theindirect deaths that occur during conflicts becauseof famine, interrupted health care, <strong>and</strong> increasedstress levels. In many African conflicts, for example,the death toll from indirect causes is considerablyhigher than the number of fatalities fromfighting.developmentIn the early work of the United Nations, theconcept of “sustainable disarmament for sustainabledevelopment” became a catch phrase for combiningthe work of the arms control <strong>and</strong> developmentcommunities. The concept is simple: sustainabledevelopment cannot exist in an insecureenvironment, as in the case of Mali in 1994, citedabove. Violent conflict destroys the physical infrastructureneeded for an economy to grow <strong>and</strong>diverts human <strong>and</strong> economic resources away fromagriculture, education, industry, <strong>and</strong> other constructiveactivities. Proliferation of weapons preventssustainable development by damaging fragileeconomies, deterring foreign investment, <strong>and</strong>diverting domestic economic resources to publicsecurity.Over the past decade we've learned a lot aboutthe impact of small arms on development. In postconflictsocieties, former combatants enter the jobmarket <strong>and</strong>, finding limited opportunities, oftenturn to crime. In El Salvador, the number of gunrelateddeaths was actually higher after the fightingended due to the extensive use of weapons in criminalactivities. In post-war Iraq, the disb<strong>and</strong>ing ofthe Iraqi army left at least 400,000 soldiers withouttheir jobs but with their guns.Fear <strong>and</strong> damaged public infrastructures c<strong>and</strong>eter public <strong>and</strong> private foreign investment.Development projects have been cancelled inLiberia, Niger, <strong>and</strong> Sierra Leone due to small armsviolence. Promised international development aidto post-war Afghanistan <strong>and</strong> to Iraq remains largelyunfulfilled due to insecurity. We also know thatorganized crime <strong>and</strong> black markets harm development.Profitable companies are now lucrative targets<strong>and</strong> businesses must invest in their own protectionto avoid kidnapping or other extortion. InColombia, the major guerrilla groups “earned” anaverage of $140 million annually between 1986 <strong>and</strong>2000 from ransom <strong>and</strong> other extortion activities.Research on the reciprocal relationship betweenunderdevelopment <strong>and</strong> gun violence is clearlycalled for. Toward this end, the Department forInternational Development of the government ofthe United Kingdom began a major assessment ofdevelopment, “Tackling Poverty by ReducingArmed Violence,” in 2003. 9 Nine SALW projectswere selected for evaluation. The researchers estimatedthat only 5% of the indicators being used inthese projects related to effects on development,poverty reduction, or humanitarian impacts. 10These projects simply did not have these outcomesas major concerns. Moreover, the study of thesenine projects concluded that for effective policy<strong>and</strong> programs, it was essential to go beyond monitoringprogress merely in terms of arms reduction(number of weapons collected, weapons sales <strong>and</strong>street prices). Measurements should also be madeof the direct impact on armed violence itself <strong>and</strong>the realities <strong>and</strong> perceptions of insecurity, as well asof other development <strong>and</strong> poverty-related effects.Evaluation research focused on such measuresshould be a high priority.15

social structuresHow small arms affect the lives <strong>and</strong> livelihoodsof individuals is fairly well understood, but weneed also to address the effects of small arms onsocietal structures, as illustrated in the followingvignettes.El SalvadorThe current situation in El Salvador is representativeof much of post-conflict Central America,where, due to insufficient disarmament <strong>and</strong> demobilizationprograms for ex-combatants, small armsare still abundant <strong>and</strong> misused. At the end of thecountry's twelve-year civil war in 1992, the UnitedNations was successful in recovering <strong>and</strong> destroyingapproximately 10,000 small arms from theFMLN guerrillas, while a private-sector initiativerecovered close to that many weapons from thecivilian population between 1996 <strong>and</strong> 2000,including highly dangerous h<strong>and</strong> grenades <strong>and</strong>rocket launchers. 11But during the Salvadoran peace process, whennearly 10,000 guerrillas were demobilized alongwith 31,000 government soldiers, the newly formedcivilian police force was m<strong>and</strong>ated to absorb only5-6,000 of these individuals, while defunct police<strong>and</strong> paramilitary forces also disb<strong>and</strong>ed. This leftthous<strong>and</strong>s of former guerrillas, soldiers, <strong>and</strong> policeofficers unemployed in a society where the problemof youth gangs was growing on a scale neverseen before. Because of the scarcity of employmentopportunities <strong>and</strong> the ability of these men to useweapons, many had life options limited to organizedcrime or employment as private securityguards.Horn of AfricaThe pastoralists in the Horn of Africa have alsoseen deleterious consequences of the influx of smallarms. The Kenyan scholar Kennedy Mkutu <strong>and</strong>others have documented this problem <strong>and</strong> workedwith the international community on potentialsolutions. 12 For generations, groups in theKaramoja region of Ug<strong>and</strong>a <strong>and</strong> the West Pokotregion on the other side of the border, in Kenya,have pursued a pastoral mode of living ordered inrelation to the size <strong>and</strong> quality of livestock herds<strong>and</strong> the environment. Cattle raiding has alwaysbeen a problem but was traditionally limited toonly the best livestock, <strong>and</strong> violence, though present,was minimal. When someone was killed inthe process, the victim's family was compensatedwith cattle by the offending group.However, because of the many African wars forindependence in the 1960s, AK-47 assault riflesbegan to appear among the different pastoralistgroups <strong>and</strong> proliferated considerably in the 1970s.This led to increased frequency <strong>and</strong> lethality of violenceamong many of the border communities aswell as a vicious circle of raid <strong>and</strong> counterraid.B<strong>and</strong>s of armed youths have now taken over largesections of the border area <strong>and</strong> warlords have capitalizedby buying <strong>and</strong> selling raided livestock <strong>and</strong>selling weapons. Traditionally, councils of maleelders governed the pastoralist communities <strong>and</strong>served as mediators in resolving conflicts, bothbefore <strong>and</strong> during colonial rule. But the deteriorationof customary governance structures in thesesocieties has weakened the capacity of elders toexercise control over young males now armed withassault rifles. Not only has the availability ofSALW <strong>and</strong> proclivity to use them affected the relationshipsbetween neighboring groups, it has alsoaltered the hierarchy of power within communities.13YemenThe research of Derek Miller in Yemen providesan example of dem<strong>and</strong> for small arms that is basedon indigenous belief systems <strong>and</strong> is a key componentof the maintenance of political <strong>and</strong> socialorder that has not resulted in high levels of crime<strong>and</strong> violence, unlike in other parts of the globe. 14<strong>Weapons</strong> in Yemen are considered part of the16

national character <strong>and</strong> are more closely associatedwith custom <strong>and</strong> tradition than with violence,injury, <strong>and</strong> death. In contemporary Yemen, malesat the age of fifteen are often provided with anassault rifle as a rite of passage.Similar to the role that SALW played in the pastoralregions of the Horn of Africa before proliferation,weapons in Yemen have long been symbolsof power, responsibility, masculinity, <strong>and</strong> wealth.This does not preclude their use for aggression ordefense, as was the case during the country's civilwar in the 1990s. However, as mentioned, therehas not been an increase in violence or SALWrelatedfatalities despite widespread civilian acquisitionof weapons as a result of the war. Strongtribal mechanisms for conflict resolution in placein Yemen prevent major outbreaks of violence. Wedo not see the youth rebelling against tribal eldersas in Ug<strong>and</strong>a <strong>and</strong> Kenya.The introduction of firearms can transform relationsbetween generations, men <strong>and</strong> women, <strong>and</strong>ethnic groups. Thus far, we have only a few suchcase studies <strong>and</strong> anecdotal evidence of howfirearms availability <strong>and</strong> use alter the establishedsocial order. Currently very few social scientistswork on how small arms affect social structures.Anthropologists <strong>and</strong> sociologists could provideuseful contributions in this area.tourismJust as small arms hinder development, so theycan inhibit tourism. Tourism has become a fastgrowingindustry <strong>and</strong> an important revenue sourcefor many countries. It creates employment in severalsectors of society, accounting for nearly 200million jobs <strong>and</strong> over 40 per cent of GDP in smallisl<strong>and</strong> economies <strong>and</strong> some developing countries.Moreover, tourism brings in foreign currency, providinga stable <strong>and</strong> reliable source of income.<strong>Small</strong> arms proliferation <strong>and</strong> the attendant threatof violence can undermine tourism because oftourists’ fear of political upheaval or crime. Touristsites are sometimes damaged or rendered inaccessibleby ongoing hostilities, <strong>and</strong> recently touristshave been specifically targeted in armed attacks.Armed groups may actually utilize tourist destinations,as with Kenyan rebel groups that use animalreserves as their base of operations. In the late1990s civil wars in several African countries causedtourism to drop by a third to a half.post-conflict reconstructionIn the last several years, we have seen the dangersof small arms proliferation <strong>and</strong> misuse in countriesemerging from war. In both Afghanistan <strong>and</strong> Iraq,the widespread availability of small arms puts securityat grave risk, severely undermines the rule oflaw, <strong>and</strong> presents a major obstacle to the transitionto peace. The availability of arms increases thepossibility of outbreak of conflicts in areas of crisis,endangers the safety of both international peacekeepers<strong>and</strong> the local population, <strong>and</strong> above all,hinders conflict resolution.As with humanitarian interventions, peacekeepingmissions <strong>and</strong> the soldiers <strong>and</strong> civilian officialsimplementing them are also at risk from smallarms. Unlike during the Cold War, in the 1990sUN forces found that small arms posed a threat tothemselves that had to be addressed. UN peacekeepersare regularly targeted, most notably inKosovo, East Timor, Sierra Leone, Bosnia, <strong>and</strong>Afghanistan. Indeed, in both Angola <strong>and</strong> SierraLeone rebels have held hundreds of UN peacekeepershostage. While some peacekeeping operationsinclude m<strong>and</strong>ates that address small arms,such as disarmament, demobilization, or collection<strong>and</strong> destruction of surplus weapons, others have nosuch m<strong>and</strong>ate. More systematic attention to smallarms must be included in post-conflict peacebuilding.The lack of such provisions in the USplan in Iraq makes clear that the wide availabilityof small arms <strong>and</strong> light weapons can provide thefuel to transform a disorganized but angry group ofcivilians into an insurgent force that not only pro-17

longs a conflict but also brings to a halt the economic,social, <strong>and</strong> political development needed tobring the conflict to an end. We see this phenomenonin other places. These cases need to beresearched <strong>and</strong> compared to produce findings thatcan be used by those charged with peace-building.governance<strong>Small</strong> arms have had notable destructive impactson the ability of some states to govern well. As discussedabove, proliferation has raised the cost ofmaintaining public order. This expense divertsresources from investment in the economy <strong>and</strong>diminishes a state's ability to help create jobs <strong>and</strong>raise the st<strong>and</strong>ard of living. In turn, all of this promotesthe acquisition <strong>and</strong> use of arms for bothlegitimate protection <strong>and</strong> illicit purposes by privatesecurity firms <strong>and</strong> individual citizens. Manywould argue that in some polities the state has foreversurrendered its role as the primary provider ofsecurity.Research has begun on the growth of privatemilitary contractors <strong>and</strong> its effect on societies. 15This work has demonstrated how private securitycompanies fuel the legal <strong>and</strong> illegal markets forsmall arms. In El Salvador, as in much of Central<strong>and</strong> Latin America, the state has lost its monopolyover the use of force <strong>and</strong> the tools of violence.These companies purchased mostly high-caliberweapons for their employees, which probably representeda good share of the more than 50,000firearms El Salvador imported between 1996 <strong>and</strong>2000. At the same time, it has been documentedthat 25 per cent of the weapons confiscated by theSalvadoran authorities were taken off of privatesecurity agents outside hours of work. 16 In recentyears the numbers of private security agents (some20,000 plus) have surpassed the 16,000 police officersserving in El Salvador. 17Such widespread availability of guns <strong>and</strong> abreakdown in the rule of law have led to the emergenceof private armed groups in many countries.Such groups are seldom held accountable for therole they play in human rights abuses. Indeed,small arms have become the weapons of choice notonly for political insurgents but also for terroristsaround the world. Nearly 75 percent of the significantterrorist incidents in 2002 were perpetratedby individuals <strong>and</strong> groups wielding small arms.<strong>Small</strong> arms create <strong>and</strong> fuel the conditions in whichterrorist groups thrive. The poverty <strong>and</strong> desperationexperienced by many post-conflict societiesare often exploited by terrorists, who use the victims'suffering to justify <strong>and</strong> build support for theiractions. Afghanistan in the 1990s provided suchan environment. Al Quaeda found there a safehaven <strong>and</strong> could tap into the vast criminal networksthat spring up in the absence of effective lawenforcement.The availability <strong>and</strong> use of firearms are determinedby the nature of governance in a country.The reverse is also true: firearms influence the waysin which countries are governed. The relationshipbetween firearms <strong>and</strong> governance is extremely significantfor development, law enforcement, <strong>and</strong>human rights, but it is underresearched.There is now a consensus typology of the effectsof the availability <strong>and</strong> misuse of small arms <strong>and</strong>light weapons, a picture that has emerged fromefforts of scholars working on one or another of themany aspects of the small arms problem. Table 1,from <strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong> Survey 2003, captures this consensus<strong>and</strong> serves as an excellent guide for furtherresearch.Notes1. Some of these accounts were the basis for a set offact sheets prepared by the U.S. <strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong> WorkingGroup (SAWG) in advance of the 2001 UN <strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong>Conference <strong>and</strong> updated for the 2003 Biennial Meetingof States follow-up conference. Fact sheets on smallarms <strong>and</strong> brokers; children; collection, destruction, <strong>and</strong>stockpile protection; development; human rights; internationalhumanitarian law; natural resources; peacekeeping;public health; tourism; <strong>and</strong> women can befound at http://www.iansa.org/documents/index.htm.18

Direct effectsFatal <strong>and</strong> non-fatal injuriesLost productivityPersonal costs of treatment <strong>and</strong> rehabilitationFinancial costs at household, community,municipal, <strong>and</strong> national levelsPsychological <strong>and</strong> psychosocial costsIndirect effectsArmed crimeRates of reported crime (homicide)Community-derived indices of crimeInsurance premiumsNumber <strong>and</strong> types of private security facilitiesAccess to <strong>and</strong> quality of social servicesIncidence of attacks on health/educationworkersIncidence of attacks on <strong>and</strong> closure ofhealth/education clinicsVaccination <strong>and</strong> immunization coverageLife expectancy <strong>and</strong> child mortalitySchool enrollment ratesEconomic activityTransport <strong>and</strong> shipping costsDestruction of physical infrastructurePrice of local goods <strong>and</strong> local terms of tradeAgricultural productivity <strong>and</strong> food securityInvestment, savings, <strong>and</strong> revenue collectionTrends in local <strong>and</strong> foreign direct investmentInternal sectoral investment patternsTrends in domestic revenue collectionLevels of domestic consumption <strong>and</strong> savingsSocial capitalNumbers of child soldiers recruited, in actionMembership of armed gangs <strong>and</strong> organizedcrimeRepeat armed criminality among minorsIncidence of domestic violence involvingfirearms or the threat of weaponsRespect for customary <strong>and</strong> traditional forms ofauthorityDevelopment interventionsIncidence of security threatsCosts of logistics <strong>and</strong> transportationCosts of security managementOpportunity costs associated with insecureenvironments <strong>and</strong>/or damaged investmentsTable 1. Effects of small armsmisuse on human development(from <strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong> Survey 2003:Development Denied. Oxford:Oxford University Press)2. Rachel Stohl et al., “Putting Children First:Building a Framework for International Action toAddress the Impact of <strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong> on Children.” Bitingthe Bullet, Briefing 11, 2001. http://www.internationalalert.org/pdf/pubsec/btb_brf11.pdf.3. Edward J. Laurance, “The New Field ofMicrodisarmament.” Brief 7: Bonn InternationalCenter for Conversion. September 1996, p. 16.http://www.bicc.de/publications/briefs/brief07/brief7.pdf.4. Stephen D. Goose <strong>and</strong> <strong>Frank</strong> Smyth, “ArmingGenocide in Rw<strong>and</strong>a.” Foreign Affairs 73:86.5. Case study on Kosovo in John Sislin <strong>and</strong> FrederickS. Pearson, <strong>Arms</strong> <strong>and</strong> Ethnic Conflict. Boulder: Rowman& Littlefield, 2001, pp. 100-105.6. Sislin <strong>and</strong> Pearson, pp. 80-81.7. For a treatment of early warning <strong>and</strong> SALW, seeEdward J. Laurance, ed., “<strong>Arms</strong> Watching: Integrating<strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Light</strong> <strong>Weapons</strong> into the Early Warningof Violent Conflict.” London:International Alert. May1990. http://www.international-alert.org/pdf/pubsec/lw_armswatching.pdf.8. Questions are from Sislin <strong>and</strong> Pearson, pp. 17-19.9. A description of this effort can be found in recommendationsfrom a Wilton Park Workshop, http://www.eldis.org/static/DOC13096.htm.10. “Assessing <strong>and</strong> Reviewing the Impact of <strong>Small</strong><strong>Arms</strong> Projects on <strong>Arms</strong> Availability <strong>and</strong> Poverty.”Bradford University Center for International Cooperation<strong>and</strong> Security. Draft synthesis report, July 2004,p. 3.11. Edward J. Laurance <strong>and</strong> William Godnick,“<strong>Weapons</strong> Collection in Central America: El Salvador<strong>and</strong> Guatemala.” In Sami Faltas <strong>and</strong> Joseph Di ChiaroIII, eds., Managing the Remnants of War: Micro-disarmamentas an Element of Peace-building. Baden-Baden:Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, 2001.12. Kennedy Mkutu, “Pastoral Conflict <strong>and</strong> <strong>Small</strong><strong>Arms</strong>: The Kenya-Ug<strong>and</strong>a Border Region.” London:Saferworld, 2003.13. Also see S<strong>and</strong>ra Gray et al., “Cattle Raiding,Cultural Survival, <strong>and</strong> Adaptability of East AfricanPastoralists.” Cultural Anthropology 44 (SupplementDecember 2003): S3-S30.14. Derek B. Miller, “Dem<strong>and</strong>, Stockpiles, <strong>and</strong> SocialControls: <strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong> in Yemen.” <strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong> SurveyOccasional Paper #9, May 2003. http://www.smallarmssurvey.org/OPs/OP09Yemen.pdf.15. Deborah Avant, “Think Again: Mercenaries.”Foreign Policy, July/August 2004; P. W. Singer,19

“Corporate Warriors: The Rise of the Privatized MilitaryIndustry <strong>and</strong> Its Ramifications for InternationalSecurity.” International Security 26, no. 3, Winter2001/02.16. José Miguel Cruz, Alvaro Arguello, <strong>and</strong> FranciscoGónzalez, “The Social <strong>and</strong> Economic Factors Associatedwith Violent Crime in El Salvador.” Washington <strong>and</strong>San Salvador: World Bank <strong>and</strong> the Instituto Universitariode Opinión Pública, Universidad Centroamericana, 1999.17. William Godnick, “Control de Armas Ligeras ySeguridad Privada: Consideraciones para Centroamérica.London: International Alert, 2004.In a Palestinianrefugee camp inLebanon, a girlst<strong>and</strong>s near a pistolleft behind by a militant.20

Guns in CrimeNicolas FlorquinIntroductionThe toll resulting from the use of small arms insocieties “at peace” is drawing increasing internationalattention. At least 200,000 non-conflictrelatedfirearm deaths occur each year worldwide,the vast majority of which (at least 140,000) arecategorized as homicides, a criminal offensethroughout the world. Nonlethal crimes involvingthe use of small arms include robberies, assaults<strong>and</strong> threats, <strong>and</strong> to a lesser extent, sexual offenses(<strong>Small</strong> <strong>Arms</strong> Survey 2004). The criminal use ofarms in societies at peace can be treated as a distinctfield of inquiry, despite the obvious overlapswith the more general questions of the effects ofgun use.The debate over the relationship betweenfirearms <strong>and</strong> crime has, for the most part, remaineda US academic <strong>and</strong> public policy issue. The academicdisciplines that have examined the role ofguns in crime to date are mainly criminal justice,public health, economics, <strong>and</strong> anthropology/sociology.Put simply, they have focused on threebroad themes:• the accessibility thesis, i.e., the relationshipbetween gun accessibility <strong>and</strong> levels of violence,defined as crime by criminologists <strong>and</strong> as deaths<strong>and</strong> injuries by public-health scholars.• the tangible economic costs gun violence imposeson societies.• the intangible impacts of gun violence on communities<strong>and</strong> individuals’ perceptions, behavior,<strong>and</strong> attitudes.21

The Accessibility ThesisNorth American criminologists <strong>and</strong> publichealthexperts have produced a large literature onthe linkages between firearm accessibility <strong>and</strong>crime. There seems to be little relationshipbetween gun availability <strong>and</strong> the rates of mostcrimes, such as assault, rape, or burglary, few ofwhich involve guns. However, studies usually finda strong association between gun availability <strong>and</strong>lethal violence (homicide), but there is a need formore detailed research in the area (Hepburn <strong>and</strong>Hemenway 2004).International cross-sectional studies of highincomecountries find that gun ownership levelsare correlated with overall rates of homicide(Hemenway <strong>and</strong> Miller 2000), although a recentinternational study found no relationship (Killiaset al. 2001). However, if only high-income countries(as defined by the World Bank) are includedin the analysis, a strong, significant relationshipagain emerges (Hepburn <strong>and</strong> Hemenway 2004).Across US regions <strong>and</strong> states, where there are moreguns there are more homicides because there aremore firearm homicides. The association holdsafter accounting for poverty, urbanization, alcoholconsumption, unemployment, <strong>and</strong> violent crimeother than homicide (Miller et al. 2002a). Resultsare similar for youth <strong>and</strong> adults, for men <strong>and</strong>women.Studies at the household, cross-state, <strong>and</strong> crossnationallevels find that the more guns there are,the more women become victims of homicide(Bailey et al. 1997, Hemenway et al. 2002; Miller etal. 2002b). Gun availability is also linked to levelsof gun crime. Cook (1979; 1987), for instance,finds that higher levels of gun ownership are associatedwith higher rates of gun robberies, <strong>and</strong> gunrobberies are more likely than other types of robberiesto result in death.Pro-gun academics argue that guns are oftenused in self-defense (Kleck 1997) <strong>and</strong> that permissivegun-carrying laws actually reduce crime (Lott1998). There are, however, a series of methodologicalproblems <strong>and</strong> data limitations surroundingthese two claims (Hemenway 1997; Black <strong>and</strong>Nagin 1998; Hemenway et al. 2000; Maltz <strong>and</strong>Targonski 2002, 2003). Many recent studies ongun-carrying laws suggest that, if anything, theselaws probably have had little effect on crime ormay actually have increased homicides (Ludwig1998; Duggan 2001; Ayres <strong>and</strong> Donohue 2003;Donohue 2003; Kov<strong>and</strong>zic <strong>and</strong> Marvell 2003;Hepburn et al. 2004).The effect of restrictive gun laws on crime <strong>and</strong>lethal violence has been more difficult to determine.For example, a recent Centers for DiseaseControl report found insufficient evidence toassess the effectiveness of eight different types ofgun control measures in reducing overall levels ofviolence (CDC 2003). The problem with the evidencestems from the difficulty of disentanglingthe effects of relatively modest gun laws from theeffects of various other factors that are changingover time.The accessibility thesis is being continually studiedin the United States. New data-collection systemshave been put in place recently <strong>and</strong> shouldgenerate richer <strong>and</strong> more comparable data, allowingfor even better studies in the years to come(Hemenway 2004).A limited number of studies have also emergedfrom Australia, the United Kingdom (see <strong>Small</strong><strong>Arms</strong> Survey 2004), Brazil, <strong>and</strong> South Africa. Littlehas been done to explore the relationship betweensmall arms availability <strong>and</strong> crime in other areas.Our knowledge would be enhanced with theimprovement of data-collection systems in manycountries, which would allow for the examinationof the accessibility thesis in different contexts.The Tangible Costs of Gun ViolenceThe economics literature has sought to quantifythe costs gun violence imposes on societies. Withrespect to costs imposed on the medical care sys-22