Departmental Self Review - UCLA Academic Senate

Departmental Self Review - UCLA Academic Senate

Departmental Self Review - UCLA Academic Senate

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

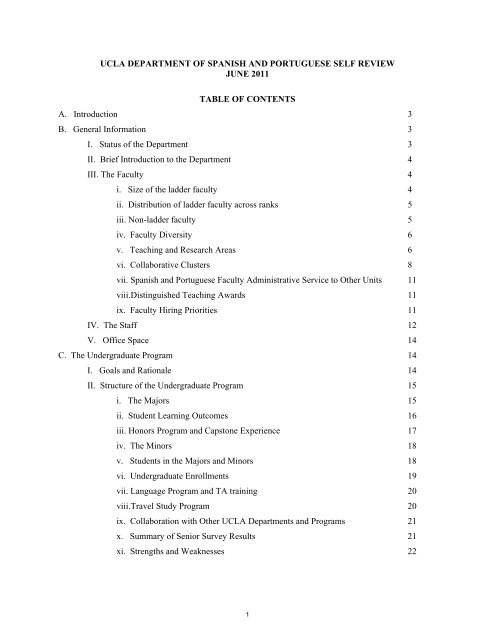

<strong>UCLA</strong> DEPARTMENT OF SPANISH AND PORTUGUESE SELF REVIEWJUNE 2011TABLE OF CONTENTSA. Introduction 3B. General Information 3I. Status of the Department 3II. Brief Introduction to the Department 4III. The Faculty 4i. Size of the ladder faculty 4ii. Distribution of ladder faculty across ranks 5iii. Non-ladder faculty 5iv. Faculty Diversity 6v. Teaching and Research Areas 6vi. Collaborative Clusters 8vii. Spanish and Portuguese Faculty Administrative Service to Other Units 11viii.Distinguished Teaching Awards 11ix. Faculty Hiring Priorities 11IV. The Staff 12V. Office Space 14C. The Undergraduate Program 14I. Goals and Rationale 14II. Structure of the Undergraduate Program 15i. The Majors 15ii. Student Learning Outcomes 16iii. Honors Program and Capstone Experience 17iv. The Minors 18v. Students in the Majors and Minors 18vi. Undergraduate Enrollments 19vii. Language Program and TA training 20viii.Travel Study Program 20ix. Collaboration with Other <strong>UCLA</strong> Departments and Programs 21x. Summary of Senior Survey Results 21xi. Strengths and Weaknesses 221

D. The Graduate Program 23I. Overview 23II. Graduate Student Support 24III. Program Performance 24i. Number of applications, selectivity and enrollment success 24ii. Median Time to Doctorate 25iii. Completion Rates 25iv. Fellowships and Grants 25v. Placement 26vi. Student satisfaction 26IV. Response to the 2002-2003 <strong>Review</strong> 27Appendix A. Counselor’s Report on the Undergraduate Program 30Appendix B. May 2011 Senior Undergraduate Survey 42Appendix C: Graduate Division Data 49Appendix D: Job Placements 64Appendix E: May 2011 Survey of Graduate Students 672

<strong>UCLA</strong> DEPARTMENT OF SPANISH AND PORTUGUESE SELF REVIEWJUNE 2011A. INTRODUCTIONA first version of the report was drafted during the spring 2011 quarter. Maarten van Delden (DepartmentChair) wrote the general overview of the Department, Jesús Torrecilla (Vice Chair for Graduate Studies)the section on graduate studies, and Carlos Quícoli (Vice Chair for Undergraduate Studies) the section onundergraduate studies (with a few paragraphs added by Maarten van Delden). The results of a survey ofour graduate students were incorporated into the section on our graduate programs, while the results of a“senior survey” conducted by Matthew Swanson, the Department’s undergraduate counselor, wereincluded in the section of the report devoted to our undergraduate programs. The report was discussed ata faculty meeting on June 3 rd . Input provided at the meeting, as well as via email communications withthe Department Chair, led to further revisions to the document. The final document was circulatedelectronically to all ladder faculty, who were given a week to review the report and were asked to vote onit via email. The final vote was: fifteen (15) in favor, zero (0) opposed, zero (0) abstentions. Eligiblevoters: seventeen (17).B. GENERAL INFORMATIONI. Status of the DepartmentThe Department of Spanish and Portuguese has operated in an extremely difficult environment over thelast year and a half. In December 2009, a Humanities Task Force appointed by Executive ViceChancellor Scott Waugh submitted a report containing a range of recommendations for the future of theHumanities, including the creation of a Language Center and a Humanities Center, as well as theconsolidation of a number of foreign language departments, among them the Department of Spanish andPortuguese. At a series of town hall meetings organized by the Dean of Humanities during the Winter2010 quarter, it became clear that the proposal for a consolidated Department of European Languages wasthe most controversial and least popular of the recommendations. Nevertheless, in October 2010 DeanTim Stowell announced that he wanted to proceed with the consolidation. The reasons given in supportof the plan to consolidate were many and varied, including the need to address the demographic crisis inthe Departments of German and Italian, the advantages of reducing administrative overhead byeliminating a number of department chairs, the desire to stimulate collaboration between faculty in thedifferent language departments, and the need to find a solution to a history of feuding in certaindepartments, including ours. An overwhelming majority of the ladder faculty of the Department ofSpanish and Portuguese opposed the merger. A joint letter was sent to the dean, in which it was arguedthat such a move would harm recruitment and retention of faculty and graduate students in our fields, andwould signal a reduced commitment on <strong>UCLA</strong>’s part to the study of the language and culture of almosthalf the population of Los Angeles. The letter also argued that the budgetary advantages of a mergerwere unclear. The opposition from Spanish and Portuguese faculty, and from the overwhelming majorityof faculty in the other departments slated for consolidation, has apparently led Dean Stowell to weighother options. However, as of the current writing, we still do not know what plans the <strong>UCLA</strong>administration has for our department. We think it essential, therefore, that the matter of the future of ourDepartment, and in particular the strong desire of faculty and students in Spanish and Portuguese to retainthe Department’s autonomy, be placed front and center in the current review. The overview that followsof our graduate and undergraduate programs, and of our strengths in teaching and research, willdemonstrate that the Department of Spanish and Portuguese is a thriving unit that makes an importantcontribution to <strong>UCLA</strong>’s educational mission. There are many areas in which our performance canimprove; however, a large majority of Department faculty remain convinced that there is no justificationwhatsoever for dissolving the Department of Spanish and Portuguese into a larger unit, especially givenour location in one of the world’s capitals of Spanish-language culture. A large majority of Department3

faculty view the proposals to merge our Department with other foreign language departments as the signof a lack of support from the administration for the fields of study we represent. We hope that all thoseinvolved in this review will explicitly address <strong>UCLA</strong>’s failure to provide adequate support for ourDepartment.II. Brief Introduction to the DepartmentWe would like to draw attention here to two features of our Department: first, the remarkable breadth ofour curricular offerings and of the research areas covered by the Department’s faculty; second, theimportant contribution our Department makes to <strong>UCLA</strong>’s diversity mission.At the undergraduate level, we offer five majors (Spanish, Portuguese, Spanish and Community andCulture, Spanish and Portuguese, and Spanish and Linguistics) and four minors (Portuguese, Spanish,Spanish Linguistics, and Mexican Studies). The richness of the Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking worldis amply represented in the extensive range of courses we teach in language, literature, linguistics, andculture. Our language program offers courses primarily in Spanish and Portuguese at all levels ofproficiency. It is enriched by courses in Catalan and indigenous languages of Latin America such asQuechua. In addition to courses on the literatures and cultures of Spanish America, Spain, Brazil, andPortugal, the Department also offers courses on Chicano literature and culture. Many of the Department’scourses have an interdisciplinary orientation, and include the study of film, music, architecture and urbanplanning, photography, and other forms of artistic expression. Our graduate program includes threeseparate tracks: in Spanish, Portuguese and Linguistics. Our faculty are national leaders in all three ofthese areas. Even though we have substantially fewer faculty than at the time of the previous review, ourSpanish program continues to offer coverage of all the major periods of Spanish and Spanish Americanliterature. Our programs also integrate a diversity of theoretical perspectives derived from fields such ascultural studies, gender studies, post-colonial studies, studies of the city, the sociology of literature andhuman rights studies<strong>UCLA</strong> is located in a city in which more than 40% of the population speaks Spanish at home. We arepart of a region that exists in very close proximity to Latin America. In such a setting, it is not surprisingto find strong student interest in learning about the cultures of the Spanish-speaking world. We note thatthis interest is especially strong among Latino students. Although we have no hard statistics at ourdisposal, we estimate that 50-60% of students in our upper-division courses are Latino. This means thatin addition to serving all interested students, we provide an especially important service to <strong>UCLA</strong>’sLatino student population. We believe that in the recent debates about a possible reconfiguration of thelanguage departments, our Department’s crucial role in meeting the needs of this segment of <strong>UCLA</strong>’sundergraduate student population has not been sufficiently stressed. There is no doubt in our mind that itwould be much more difficult for us to fulfill this role if we were to lose our departmental autonomy.Calls for greater collaboration with other units presuppose that Department of Spanish and Portuguesefaculty should teach more courses in English. Doing so, however, would directly undermine our diversitymission, which depends in large part on the Department meeting the overwhelming student demand (inparticular from Latino students) for courses taught in Spanish.III. The Facultyi. Size of the ladder facultyAs of Spring 2011, the Department has 17 ladder faculty (technically 14 and ¼, if we take jointappointments into account). Appointments are divided by rank as follows: 13 Full Professors, 3Associate Professors, and 1 Assistant Professor.A comparison with the previous self-review, conducted in May/October 2002, is instructive. In Fall2002, the Department had 20 ladder faculty (18 and ¾, with joint appointments taken into account).Division by rank in 2002 was as follows: 14 Full Professors, 4 Associate Professors, and 2 AssistantProfessors.4

Since 2002, the Department has lost Professors Carroll B. Johnson, Enrique Rodríguez Cepeda, JoséMonleón, C. Brian Morris, John Skirius, Gerardo Luzuriaga, Guillermo Hernández, Elizabeth Marchantand Susan J. Plann. The above-named professors have retired (Rodríguez Cepeda, Morris, andLuzuriaga), passed away (Johnson, Skirius, Monleón and Hernández) or transferred to other <strong>UCLA</strong>departments (Marchant and Plann). Mention should also be made of the retirement during the reviewperiod of José Cruz-Salvadores, who held the position of Lecturer SOE. This means that he was an<strong>Academic</strong> <strong>Senate</strong> member and that his position was a faculty FTE.Since 2002, the Department has hired five new professors. They are Professors Maite Zubiaurre, JorgeMarturano, José Luiz Passos, Barbara Fuchs and Maarten van Delden. In addition, Professor TeófiloRuiz of the History Department now has a 0% appointment in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese.The quality of the Department’s new hires is clear proof of <strong>UCLA</strong>’s prestige and of the strength of ourprograms. Nevertheless, we must draw attention to the substantial reduction in our numbers since the lastreview. Even if we exclude the two colleagues who transferred to other departments at <strong>UCLA</strong>, we arestill left with a reduction of 4 FTEs, equal to a decline in our numbers of over 20% of our full-timefaculty. We note that this reduction took place before the current budget crisis erupted. Given statementsfrom the administration that budgetary difficulties can be remedied only by means of a down-sizing of thefaculty, we feel compelled to point out that this process has already occurred in Spanish and Portuguese.We strongly believe that there should be no further reduction in our numbers; on the contrary, wemaintain that it is imperative for the Department’s continued standing and competitiveness in the fieldthat some of the ground that has been lost since 2002 be recovered in the near future.ii. Distribution of ladder faculty across ranksAt the time of the last review (2002), the distribution of the faculty was 14 Full Professors, 4 AssociateProfessors, and 2 Assistant Professors. The review team singled out the “top-heavy” distribution offaculty as an “area in need of attention.” On p. 5 of the 2003 “<strong>Review</strong> Team Report Narrative,” we readthe following advice to the department: “A more balanced distribution of ladder faculty needs to beestablished by hiring budding scholars equipped with recently developed methodologies and fresh ideasin the assistant range.” The problem of the top-heavy distribution of the faculty has worsened since thelast review. Although we question the implication of the statement from the 2003 review team that seniorprofessors don’t generate “fresh ideas,” we believe that the review team’s recommendation that theadministration authorize searches in Spanish and Portuguese in the Assistant Professor range is even moreurgent now than it was at the time of the last review. Not only do younger scholars have a distinctivecontribution to make to research and teaching, their presence in a department ensures both continuity andrenewal with regard to the future.iii. Non-ladder facultyThe Department also employs a number of lecturers, teaching fellows, and visiting professors whostrengthen and enrich our undergraduate and graduate curricula. In 2010-2011, we employed sixlecturers: Dr. Juliet Falce-Robinson, our Lower-Division Coordinator; Victoria West, who teachescourses in our lower-division program; Raquel Villero, a Catalan lecturer; Dr. Tomás Creus, who teachesPortuguese language courses and courses in Luso-Brazilian literature and culture; Dr. Juan Jesús Payán, alecturer in Spanish who teaches both lower- and upper-division courses; and Luz María de la Torre, whoteaches Quechua and Spanish language courses. We think it is worth drawing attention to theDepartment’s success in obtaining external funding for a number of its teaching positions. Of the lecturerpositions just listed, three are funded with substantial help from outside agencies. Creus’s position isfunded in part by Brazil’s Ministry of Foreign Relations; Payán’s in part by Spain’s Ministry of ForeignRelations; Villero’s in part by the Institut Ramón Llull in Barcelona, Spain; De la Torre’s in part by TitleVI funding from the Latin American Institute. The fact that these agencies have agreed to fund teachingpositions at <strong>UCLA</strong> speaks to the Department’s international prestige. The appointments of Villero andPayán will end at the close of the current academic year. However, the programs that allowed us to hire5

them are being continued: the search for a new Catalan lecturer is now underway, while a replacement forPayán has been identified and approved. Our current expectation is that de la Torre will remain with usfor at least three more years, so that she can continue to build <strong>UCLA</strong>’s Quechua program. De la Torre’sQuechua courses are listed in the course schedule under “Indigenous Languages of the Americas” andscheduled through the Department of Linguistics; however, that department provides no funds for de laTorre’s position.The Department regularly employs Visiting Professors. During 2010-2011 the following Visiting Facultytaught for us: Gabriela Copertari, Associate Professor at Case Western Reserve University, and aspecialist in Argentine literature and film; João Adolfo Hansen, Professor of Brazilian Literature at theUniversity of São Paulo; Roberta Johnson, Professor Emerita at the University of Kansas; and SherryVelasco, Professor of Spanish at the University of Southern California.Finally, mention should be made of our very successful Faculty Fellow program, a postdoctoral teachingprogram intended for recent <strong>UCLA</strong> Spanish & Portuguese PhDs with the prospect of pursuing academiccareers at leading research universities. Faculty fellows normally teach a combination of lower- andupper-division courses while advancing their research and seeking permanent employment elsewhere. In2010-2011, the Department employed two Faculty Fellows and we have made one appointment for 2011-2012.iv. Faculty DiversityAccording to statistics maintained by <strong>UCLA</strong>’s Office of Faculty Diversity and Development, Hispanicsare well represented on our faculty, at 9.8 faculty, or 70% of the total. The same table indicates that wehave 6 women on the faculty, equal to 43.1% of the total. The statistics provided are for the currentacademic year and take joint appointments into account. For more detailed information, see:http://faculty.diversity.ucla.edu/library/data/index.htm#mngrphv. Teaching and Research AreasThe Department continues to be strong in all of its sub-fields, although faculty attrition has led to athinning of the ranks in several areas. The main sub-fields are Spanish literature (Dagenais, Ruiz, Fuchs,Torrecilla, and Zubiaurre), Spanish American literature (More, Kristal, Bergero, Cortínez, Clayton,Marturano and Van Delden), Luso-Brazilian literature (Johnson and Passos), Linguistics (Parodi andQuícoli) and Chicano/a literature (Calderón). Some colleagues teach and do research in more than one ofthese sub-fields. Examples are Kristal (Spanish literature), More (Luso-Brazilian), Parodi (SpanishAmerican literature), and Calderón (Spanish American literature).Spanish literature remains a solid field. We have two medievalists on the faculty, John Dagenais andTeo Ruiz. Dagenais has published on the ethics of reading in a manuscript culture and is currently atwork on several research projects, including a project in the field of digital humanities that involves 3-Dvirtual reality reconstructions of pre-Romanesque and Romanesque churches in Santiago de Compostela.Ruiz is a scholar of the social and cultural history of late medieval and early modern Castile, with elevenauthored or co-authored books to his name. Although his primary appointment is in the HistoryDepartment, he has been an active teacher and mentor in Spanish and Portuguese, in addition to chairingthe Department in 2008-2009. Barbara Fuchs, who has a joint appointment with English, specializes inEarly Modern Spanish literature. Trained as a comparatist (English, Spanish, French, Italian), Fuchsworks on European cultural production from the late fifteenth through the seventeenth centuries, with aspecial emphasis on literature and empire. She is the author of four books and numerous otherpublications in the field. Jesús Torrecilla is a specialist in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Spanishliterature with thirteen books (five single-authored scholarly books, five edited or co-edited works, andthree novels) to his name. His scholarly work focuses on the reception of modernity in Spain. MaiteZubiaurre is a specialist in twentieth-century Peninsular literature and cultural studies. Trained as acomparatist, her scholarly work includes a book on the dialectics of space and gender in European and6

appointment in our department. A Professor in the Department of Applied Linguistics, her areas ofexpertise are Spanish linguistics, deaf studies, service learning and oral history.vi. Collaborative ClustersThe purpose of this section is to present a fuller picture of the Department’s research, teaching andoutreach profile by highlighting clusters that allow Department faculty to collaborate with each other aswell as with faculty and entities outside the Department.Early Modern StudiesDecidedly trans-Iberian and interdisciplinary, early modern studies continues to be a vibrant field in theDepartment. Despite the net shrinkage of faculty FTEs in recent years, the hire of Barbara Fuchs and thejoint appointment of Teo Ruiz have kept the field viable. Recent initiatives have built strong bridges toother departments at <strong>UCLA</strong> and across the UC system. Fuchs and Anna More’s close research andpedagogical collaboration makes <strong>UCLA</strong>’s one of the few truly transatlantic programs in early modernstudies. In 2010-2011 Fuchs and More spearheaded the Early Modern Studies Research Group (EMRG)an interdisciplinary working group for early modern studies at <strong>UCLA</strong> and in the region. The groupbridges the focus of the two early modern centers on campus (the Center for Medieval and RenaissanceStudies and the Center for 17th- and 18th-Century Studies). As part of the inaugural year, Fuchs andMore organized a lecture series on “Early Modern Cosmopolitanisms” featuring five high profile speakers(Florence Hsia, John Watkins, Susan Phillips, Paula Findlen and Christopher Johnson) funded by theMellon Fellowship for Transformational Support in the Humanities. Funding has been renewed for anadditional two years. In 2010-2011 More also collaborated with Ivonne Del Valle (UC Berkeley) tofound a UC Multi-Campus Research Group (MRG) titled “Early Modern Globalization,” in which Fuchsparticipates. The group, which includes twelve faculty members from across the UC system in the fieldsof History, Art History and Literature, focuses on the global effects of Iberian expansion. Finally,Barbara Fuchs has recently been named Director of the Center for 17th- and 18th-Century Studies and theClark Library for a five-year term. While this appointment undoubtedly benefits the Department inmultiple ways, it also means a further reduction of Fuchs’ FTE to .25 over the course of her tenure andthus gives additional urgency to a hire in early modern studies (see section ix below).Colonial StudiesAn important focal point for colonial studies at <strong>UCLA</strong> is the Center of Colonial Ibero-American Studies(CECI), a research unit that brings together students and professors whose academic backgroundsembrace a variety of disciplines. Established in 2000 by Dr. José Pascual Buxó and Dr. Claudia Parodi,the main goal of CECI is to promote the study of the languages, literatures and cultures of colonial LatinAmerica from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries. CECI’s research interests and activities include:editing colonial texts; creating specialized databases and bibliographies; becoming acquainted with andvisiting libraries and archives throughout the United States, Latin America and Europe that house colonialtexts; and investigating different theoretical proposals in various disciplines. CECI has hosted talks bymany important figures from the worlds of literature and academia, including Rodolfo Cerrón Palomino(Peru), Guillermo Samperio (Mexico), Cristina Rivera Garza (Mexico) and Sara Poot Herrera (USA).Currently, CECI researchers are undertaking a critical edition of the "Neptuno alegórico” by Sor JuanaInés de la Cruz. One of CECI’s most important contributions to the study of the Ibero-American colonialperiod is the paleography seminar offered by Parodi. CECI has also sponsored important conferences,including a very successful Colonial Symposium, held in October 2010 and featuring Margo Glantz as akeynote speaker. Recently, CECI received a grant from UC Mexus to organize a conference on thecolonial period, in conjunction with the University of San Luis Potosí in Mexico.8

Caribbean StudiesThe Department has a very active agenda in the area of Caribbean Studies. Since 2006, Jorge Marturanohas co-organized with Robin Derby (History) several interdisciplinary Latin American Institute workinggroups related to the Caribbean. These working groups have brought dozens of guest speakers to thecampus and to our Department’s Lydeen Library. Marturano and Derby also co-organized a two-yearlong<strong>UCLA</strong> Mellon Faculty Seminar on Caribbean Cultural History (with the support of a Mellon Grantfor Transforming the Humanities) that was very active in organizing talks and small workshops. Inaddition, they co-organized (with the support of the Latin American Institute) a two-day-longinterdisciplinary conference titled “The 1950s in the Caribbean,” with the participation of twentyscholars. The list of guest speakers on Caribbean topics during the last five years is too long to include infull, but among the guest speakers it is worth mentioning Emilio Bejel (UC Davis), José Quiroga (EmoryU), Sybille Fischer (NYU), Elzbieta Sklodowska (Washington U), Juan Carlos Quintero Herencia (U ofMaryland), César Salgado (U of Texas, Austin), Raúl Fernández (UC-Irvine), Francisco Morán (SMU),Jossiana Arroyo (Uof Texas, Austin), Peter Hulme (University of Essex), Jacqueline Loss (U ofConnecticut), Lucía Suárez (Ahmerst College), Pedro Pérez Sarduy (London Metropolitan U), IdelberAvelar (Tulane U), Luis Duno-Gottberg (Rice U), and Roberto Ignacio Díaz (USC).Southern Cone StudiesArgentina and Chile are at the center of sustained teaching and research in this area. The activities of theladder faculty—in particular Professors Verónica Cortínez and Adriana Bergero—have been strengthenedby numerous academic initiatives: an international conference on “Cultures and Politics of Memory andHuman Rights in Post-dictatorship Southern Cone,” with the participation of the co-founder of theArgentine human rights movement HIJOS, Juan Martin Aiub, as well as Chilean Mapuche human rightsactivist Graciela Huinao (May 21-22, 2008); the presence of Chilean writer Alberto Fuguet as VisitingProfessor; seminars and discussions with filmmakers from both Argentina and Chile such as LucreciaMartel, Liliana Paolinelli, Carlos Flores and, most recently, Patricio Guzmán (in collaboration with the<strong>UCLA</strong> Film & Television Archive); a homage to Pablo Neruda on the occasion of his centennial (filmscreening and round-table); a poetry reading by Raúl Zurita, a workshop with Diamela Eltit, etc. Theinstitutional link with the Latin American Institute’s “Center for Argentina, Chile and the Southern Cone”as well as the UC-Chile Agreement on academic cooperation further enhance the perspectives forsuccessful exchanges. The results of these efforts are reflected in numerous publications and a series ofrecent doctoral dissertations and new dissertation projects (Eva Perón, Alfonsina Storni, Fuguet, Chileanfilm of the 90s, Chilean culture of the 80s against Pinochet, Human rights and movements of theArgentine civil society, etc.).Mexican StudiesThe field of Mexican Studies relies on the contributions of three faculty members who work on thecolonial period (Cortínez, More and Parodi) and two who work on twentieth and twenty-first centuryMexican literature (Calderón and Van Delden). In recent years, the area has strengthened its profilewithin the Department and the University at large through the creation of a new minor in MexicanStudies, and the development of new courses, such as Anna More’s Hypermedia Mexico City course, firsttaught in Spring 2011. The field benefits from its close links to <strong>UCLA</strong>’s Center for Mexican Studies,which in the last two years has co-sponsored two symposia on the Mexican Revolution with significantparticipation of Department of Spanish and Portuguese faculty. The Department offers a very successfulSummer Study Abroad program in Mérida, which in recent years has been directed by Dr. Juliet Falce-Robinson. We have also taken advantage of our proximity to Mexico by developing a very productiverelationship with the University of Guadalajara, which in recent years has sponsored an annual miniseminarin our Department offered by prominent Mexican writers such as Hugo Gutiérrez Vega and JorgeEsquinca, as well organizing “Cátedra Julio Cortázar” lectures on our campus by eminent figures such asCarlos Fuentes and Jorge Volpi.9

(http://sicalipsis.humnet.ucla.edu), as a companion to her book (Cultures of the Erotic in Spain 1098-1939) forthcoming from Vanderbilt University Press. Also active in this area is Professor Anna More,who, with the support of a grant from the Office of Instructional Development, has built a course arounddigitized historical maps and readings on Mexico City.vii. Spanish and Portuguese Faculty Administrative Service to Other UnitsFaculty members of the Department of Spanish and Portuguese continue to make importantadministrative contributions to other units on campus. Examples are Héctor Calderón (Director,Education Abroad Program in Mexico, 2004-2008, and founding Executive Director of Casa de laUniversidad de California en Mexico, A.C., a UC mini-campus in Mexico City, 2006-2008); VerónicaCortínez (Director, Education Abroad Program, Chile, 2005-2006 ); Barbara Fuchs (recently appointedDirector, Center for 17 th and 18 th Studies at <strong>UCLA</strong>); Randal Johnson (currently, Interim Vice Provost forInternational Studies; Director, Latin American Institute, 2005-2010); Efraín Kristal (currently, Chair,Department of Comparative Literature; Director, Education Abroad Program in Paris, 2005-2008); JoséLuiz Passos (Director, Center for Brazilian Studies, 2008-2011) . The service to the University and to theUniversity of California system rendered by faculty members of the Department of Spanish andPortuguese shows the willingness of Department faculty to step outside the confines of our own unit andengage with other entities on campus as well as within the wider UC community.viii. Distinguished Teaching AwardsThe Department of Spanish and Portuguese has a distinguished track record in the area of teaching. Thefollowing members of the Department have won <strong>UCLA</strong>’s coveted Distinguished Teaching Award, forwhich only a handful of winners are selected each year: Verónica Cortínez (1998); Efraín Kristal (2000);Jesús Torrecilla (2004); Teo Ruiz (2008); and Susan Plann (2010). Mention should also be made of theOutstanding Teaching Award granted in 2010 to Claudia Parodi by the Graduate Student Association at<strong>UCLA</strong>.ix. Faculty Hiring PrioritiesIn May 2010, the Dean of Humanities invited departments in the Humanities Division to submit theirrequests for faculty searches over the next few years. The Department of Spanish and Portugueserequested hires in the following fields: Central American literature and culture, Early Modern Luso-Hispanic studies, and Linguistics. Following we provide brief rationales for searches in these areas. (Todate, none of the requests has been approved).A hire in Central American literature is justified by the intrinsic interest and importance of the field; bythe opportunities a hire in this field would offer for collaboration with other disciplines and departments;by the demographic changes that have taken place in recent decades both in our region and at <strong>UCLA</strong>,which include significant growth in the Central American population; and by strong interest in the fieldamong both graduate and undergraduate students at <strong>UCLA</strong>. The appointment of an expert in CentralAmerican literature and culture would complete the geographical sweep of Latin American studies in theDepartment (we currently have experts working on all the other major regions of the continent) and wouldstrengthen our ability to compete for the best Latin Americanist graduate students.The Department has a strong need for an additional FTE in 16th- and 17th-century Luso-Hispanic studies.In the past several years, we have lost 2 FTEs in the field and have gained only .5 FTE with the hire ofProfessor Barbara Fuchs. With some of the best known works of peninsular literature in drama, poetry,and prose, the field is foundational for Hispanic literature. The social and cultural development of Luso-Hispanic regions are largely inexplicable without reference to this period in which Spain’s empireprecipitously rose and fell. Both the literary production of the period, which influenced many laterperiods, and intellectual and cultural production from both sides of the Atlantic provide alternativeperspectives on modernity that are essential to understanding the region today. It is impossible for oneperson, with only half an appointment in the Department, to cover two hundred years of literary and11

cultural production across the genres, and this lack of staffing puts us at a considerable disadvantage inrelation to our peer institutions when it comes to recruiting graduate students in the field. In sum, it iscrucially important that this area be strengthened with an additional hire.The Department also has a strong need for a linguist with specialization in Spanish Phonetics andPhonology and a focus on experimental methods in linguistic research, and language acquisition (Spanishas L1 and L2). Studies of Spanish Phonetics and Phonology with an experimental focus on the utilizationof new technological tools in statistics and in sociolinguistics are exciting new fields with strong graduatestudent interest and increasing professional opportunities. Most of our current students are interested indoing research on the Spanish language as spoken in Los Angeles. Since <strong>UCLA</strong> is a premier center forgeneral phonetics and phonology and because Los Angeles has a huge Spanish-speaking population, theaddition of a specialist in Spanish Phonetics and Phonology with strong statistical knowledge will allowus to tap into campus resources and to develop a high level of research focused on the Spanish languagein general and on Los Angeles Spanish in particular, with the potential of being a leader in this excitingnew area.IV. The StaffTogether with the Departments of Linguistics and Applied Linguistics, the Department of Spanish andPortuguese is part of a single administrative unit known as the Rolfe/Campbell Humanities Group(RCHG). We have seven staff members, five of whom are shared with other units. Compared to the lastreview, we have seen a decline in the staff members available to the Department. At the time of the lastreview, the Department of Applied Linguistics was not yet part of the Rolfe/Campbell Humanities Group.This means that four staff members who previously split their time between the Department of Spanishand Portuguese and the Department of Linguistics now work for the Department of Applied Linguistics aswell. One position was converted in 2010 from a full-time position in Spanish and Portuguese to a splitposition between Spanish and Portuguese and Linguistics. The result is that we have gone from theequivalent of five full-time positions to 3.76 positions.In the last two years, we have seen considerable turnover among the staff. Four staff members left theDepartment in academic year 2009-2010 and in two cases appointing replacements took excessively long,in part because of uncertainty in the dean’s office over whether new appointments to these staff positionswould be authorized. An added complication was that one new appointment proved unsuccessful and anew search to fill the position in question had to be undertaken. The result was that between November2009 and March 2010, the Department had to manage for approximately eleven months without a fulltimemanager (two separate part-time interim managers were appointed to help out). The <strong>Departmental</strong>so had to manage without an undergraduate adviser for approximately five months. We needs to be toemphasized is that the remaining staff members worked extra hard to ensure the continued smoothrunning of the Department. We are also happy to report that we are extremely pleased with the staffmembers hired during the past year, and believe that at this point we have an excellent team in place.Following is a list of our staff members and their main duties.One Chief Administrative Officer (Claudia Salguero), who splits her time between the Departments ofSpanish and Portuguese, Linguistics, and Applied Linguistics [33.3%]. Claudia oversees all financial,purchasing and payroll transactions, financial management, human resource management, contract andgrant administration, gift policy administration, facilities and materials management as well asinformation systems management. She hires and trains the staff, establishes performance standards andjob duties, and develops and implements office management policies related to staff work environment.Claudia advises and informs the Chairs on all issues in the Department, and is the liaison between theCollege administrative offices and our Department.12

One Student Affairs Officer III (Hilda Peinado), who serves as our graduate student advisor. Hildaadvises all new and continuing students on courses, requirements, funding opportunities and fellowships.She also advises those graduate students with academic and financial hardships. Hilda coordinates thegraduate admissions process. She also coordinates the class schedule and classroom assignments for theDepartment. Hilda is responsible for hiring Teaching Assistants and Graduate Student Researchers. Inthese capacities, she works closely with administrators, faculty, staff, Masters and Doctoral students. Shealso coordinates, plans, develops, implements, modifies, and evaluates policies and procedures for theefficient operation of admissions and academic advising services.One Student Affairs Officer II (Matthew Swanson), who provides academic counseling to undergraduatestudents on major and minor requirements, course selection and placement exam results. He meets withincoming freshmen and transfer students to advise them and answer questions about our major and minorprograms. He maintains accurate records for departmental long-range planning. He provides relevantdata and reports to faculty and Department staff, and maintenance of student records. He also presentsthis information at university fairs and open houses. Matt is responsible for the Department’s graduationceremonies for undergraduate students. Matt splits his time between Spanish and Portuguese andLinguistics (50%).One Front Office Coordinator (Nivardo Valenzuela), who serves as the main point of contact for allstudents and visitors to the Department. Nivardo handles all day-to-day logistics of teaching operationssuch as textbook orders, supply orders, audio-visual equipment requests, mail distribution, conferenceroom scheduling and parking assignments. He provides general administrative support to the Chair,faculty, staff, and students. He is responsible for travel and entertainment reimbursement; manages allarrangements for conferences and receptions, including travel logistics and accommodations for speakers.He prepares publicity materials for lectures and seminars, and maintains departmental bulletin boards, e-mail lists, and web-pages.One <strong>Academic</strong> Personnel Officer (Peter Kim), who also works for the Linguistics and Applied LinguisticsDepartments (33.3%). His duties include preparing dossiers for merit and promotion cases, inputtingpayroll appointments and sabbaticals in the on-line system, and handling visa issues and hiring paperworkfor all faculty and visiting scholars. Peter supervises all aspects of the academic personnel processes forthe three departments. Peter oversees the distribution and dissemination of all benefits information. Hereconciles payroll ledgers and prepares reports for the Manager and Chairs. He also oversees the hiring ofTA/GSR and other student related payroll/personnel policies and procedures.One Fund Manager (Christopher Palomo), who also works for the Linguistics and Applied LinguisticsDepartments (33.3%) Chris coordinates all financial transactions, manages all aspects of purchasing andledger/account reconciliation. He prepares monthly and annual budget reports for CAO and Chairs asneeded. Chris oversees all reimbursement processes to ensure proper policies and procedures are beingfollowed, ensure that proper funds are recharged, and oversees all travel and relocation arrangements. Heprepares all intercampus payments and departmental deposit transmittals. Chris manages all sales andservice accounts and ensures that activity complies with university policies and procedures. He assistsfaculty with COR grant applications. He also reviews and reconciles monthly ledgers.One <strong>Departmental</strong> Technology Analyst (Drake Chang), who splits his time between our Department(26.6%), the other two Departments in the Rolfe/Campbell Humanities Group, and the Center for DigitalHumanities. He provides technical support in all areas of computing and acts as the support coordinatorfor all faculty, graduate students and staff. Drake troubleshoots workstation, local network, Internet andremote access problems; advises users on computer related issues and available services; trains users inthe basics of computer systems, instructional technology and network services.13

V. Office SpaceOne significant improvement has taken place compared to the previous review: our TAs now have muchmore adequate office space than nine years ago. However, we note that the problem of the lack of airconditioning in Rolfe Hall continues. It is very disappointing that the Department of Spanish andPortuguese is one of the very few departments on campus that continues to be housed in a buildingwithout air conditioning. We take the opportunity to strongly urge the administration to take thenecessary steps to address this problem. In effect, faculty, staff and students in the Department of Spanishand Portuguese are being asked to work in conditions that are substantially inferior to the conditionsenjoyed by the overwhelming majority of the <strong>UCLA</strong> community.Our current office inventory is as follows:16 ladder faculty offices3 emeriti offices4 visiting faculty offices7 lecturer offices9 TA offices (shared between 3-4 TAs)5 staff offices1 department Chair office1 main department office1 small conference room1 department library1 small computer lab with 3 terminals1 graduate student publications office1 equipment room (projector, screen, TV monitors, DVD player, speakers)1 copy room with 1 computer terminal1 mailroom1 small kitchen1 department archival room1 department archival room shared with the Rolfe-Campbell Humanities Administration GroupNotes:1. The distribution of TA, visiting faculty and lecturer offices fluctuates from academic year toacademic year.2. The conference room is used for committee and staff meetings and, on occasion, for graduateseminars and small classes for which the Scheduling Office was unable to find classrooms.3. Most department lectures are held in the library, which is currently being upgraded with AVequipment in order to host such lectures.C. THE UNDERGRADUATE PROGRAMI. Goals and RationaleOur goals for undergraduate education in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese are oriented towardsthe implementation of a particular version of a liberal arts education. In this regard, the Department isconcerned with three main goals.Our first goal is coincidental with the general purpose of a liberal arts education offered by many otherforeign language departments in the country. Similar to undergraduates at other universities in the UnitedStates, our undergraduates are expected to gain a perspective on a range of disciplines as part of their14

general education, to concentrate in one area, to perfect their analytical and critical faculties, to expressthemselves in a foreign language, to appreciate literature and other forms of art, and to sharpen theirjudgment in issues of ethics and morality in order to be able to function effectively as citizens in adiverse, democratic society.Our second goal is to provide an educational program that is appropriate to the special circumstanceshaving to do with <strong>UCLA</strong>’s location in Los Angeles—a city with large Chicano, Mexican, and CentralAmerican populations, a growing Spanish-speaking population originating from all parts of LatinAmerica and Spain, and a substantial Portuguese-speaking community. What distinguishes theDepartment of Spanish and Portuguese at <strong>UCLA</strong> from many other similar departments in the country isthe way the Department has responded to these special circumstances. Spanish is not a foreign languagein the area—it was spoken here many years before English, and it continues to be the native language ofmillions of Californians. Our task in this regard is similar to that of an English department at anAmerican university. To reiterate what was stated in our previous <strong>Self</strong> <strong>Review</strong>, “our field is not simplyan academic discipline here; it is a demographic, social, and cultural reality. Insofar as we are concernedto broaden and especially deepen Latino students’ knowledge of their own tradition, our objectives arecloser to those of a typical English department, or to those of other Spanish departments in places whereEnglish- and Spanish-speaking cultures co-exist.” (<strong>Self</strong> <strong>Review</strong> 2002, p. 1).Our third goal is to contribute to the University’s educational mission by providing courses to support theundergraduate majors of other departments and inter-departmental programs with which we collaborate(Latin American Studies, Chicano/Chicana Studies, Comparative Literature, Linguistics), and to meet thedemand for courses in Spanish and Portuguese to the large number of <strong>UCLA</strong> students whose interests aredriven by the pervasive influence of Latin American cultures in the area and our many ties to the SpanishandPortuguese-speaking countries around the world. These multiple goals are reflected in the structureof our undergraduate curriculum and in the diversity of our faculty.II. Structure of the Undergraduate Programi. The MajorsIn order to accomplish the above-stated goals, the Department has developed five undergraduate majors,leading to the B.A. degree, all of which require approximately forty five upper division units. Four ofthese majors were already in place at the time of the previous review. One new major was created sincethat time—the Spanish and Community and Culture major. What differentiates these five majors is therelative emphasis placed on different aspects of the areas covered by the department. A brief descriptionof these majors and their respective upper division requirements is given below (more detailedinformation about these majors and about the recent changes introduced is provided in Appendix A):a) Spanish: emphasizes the study of literature and forms of cultural expression of the Spanish speakingworld. Upper Division: Sp 119 (Structure of the Literary Work); b) Sp 120 (History of Literature), c)Eight elective courses from the areas of literature, culture, linguistics, media, and interdisciplinarystudies; d) Sp 191-A (Capstone seminar). The recent changes made in this major were intended tostreamline the program with the elimination of survey courses in favor of two more focused coursesdealing with the structure of literary work and literary history, and also to give more flexibility to theprogram, allowing more choices to students, and encouraging the creativity of the faculty. This majorwas recently approved as a capstone major.b) Spanish and Community and Culture: emphasizes the study of cultural and linguistic aspects ofcommunities of Hispanic heritage in California and in the US, with a distinguishing Community-BasedLearning and Service Learning component. Upper Division: Sp 100-A (Phonology) or Sp 100-B(Syntax); Two from Chicano/a 100SL, Sp 165SL, Sp M172SL; Sp 119 or 120; Four from Sp 130 through195; Two additional courses from Chicano/a Studies or Soc M155. This major already has an approvedcapstone feature. This major is currently the second largest major in the Spanish and Portuguese15

Department. It has a strong Chicano Studies component, and has allowed the Department to strengthenits community-outreach profile.c) Spanish and Linguistics : an inter-departmental major with the Linguistics Department, whichemphasizes the study of the Spanish language—its structure (phonology, syntax), its historical evolution,its dialectal variants, and its socio-linguistic dimensions—in the context of modern linguistic theory.Upper division: a) Spanish: Sp 100-A; Sp 100-B; Four electives in Spanish; b) Linguistics: Ling 103;Ling 120-A; Ling 120-B; Ling 160; Ling 165-A or Ling 165-B. The Linguistics Department has acounterpart of this major (Linguistics and Spanish) with the same course requirements.d) Portuguese: a major designed for students interested in the Portuguese language and the literature, film,and cultural expressions of the Portuguese-speaking world, with emphasis on Brazil. Upper Division:Port 100-A or Port 100-B; Port 130-A; Port 130-B; Seven electives from Port 100-A to Port 199. Thismajor was redesigned to better reflect the more central position that the study of film and other forms ofcultural expression now occupy in the program. A name change for this major is also being contemplatedto go along with the broader dimension of the program.e) Spanish and Portuguese: a combined major that allows students to focus on the combined study of thelanguages, literatures, and cultures of the Spanish- and Portuguese speaking peoples, with a primaryemphasis on Spanish America and Brazil. Upper Division: Sp 100-A or 100-B; Port 100-A or Port 100-B;Sp 119; Sp 120; Port 130-A and Port 130-B; Two electives in Spanish; Two electives in Portuguese; Oneadditional elective in Spanish or Portuguese. This major was recently adjusted to reflect the changes inthe Spanish and Portuguese majors noted above.The structure of our majors above reflects recent revisions made in the program in 2010. These changeswere made in part to conform to the new College of Letters and Sciences policy that called for a uniformnumber of 45 upper division credit units for all majors in the College (“Challenge 45”). However, somechanges were also made to give more focus to the literature centered majors by instituting a requiredanalytical course (Sp 119: Structure of the Literary Work), by consolidating various survey courses into asingle course (Sp 120: History of Literature), and by shifting linguistics courses from required courses toupper division electives. These changes also had the effect of giving more flexibility to the program, andof allowing more choices to students. The revised majors are in the initials stages of implementation, andsome fine-tuning will probably be necessary to ensure that the changes that were introduced will indeedproduce the intended programmatic results. A more complete description comparing the old majors andthe revised majors is provided in Appendix A.ii. Student Learning OutcomesIn the process of updating our undergraduate program, the Department defined the learning outcomes foreach Major.Spanish Major. Graduates in the Spanish major will be able to: a) demonstrate a mastery of the Spanishlanguage, both written and oral; b) demonstrate, within the context of a specialized topic in Spanish andSpanish American studies, specific skills and expertise acquired in earlier coursework, including research,analysis and writing; c) identify and analyze appropriate primary sources; d) acquire a workingknowledge of scholarly discourse relative to a specialized topic; e) conceive and execute a project thatidentifies and engages with a specialized topic; f) engage with a community of scholars, presenting one’sown work to peers and helping to further the work of those peers through discussion and critique.The learning outcomes for the new Spanish major were developed by the Undergraduate AffairsCommittee as part of the restructuring of the major in response to Challenge 45. The new majorrequirements along with the learning outcomes were approved at the February 7 th , 2010 Departmentmeeting by a vote of fifteen (15) in favor and one (1) opposed.16

Spanish and Community and Culture Major. Graduates in Spanish and Community and Culture will beable to: a) demonstrate a mastery of the Spanish language, both written and conversational; b) conductand interpret research to determine the needs of specific communities; c) demonstrate a criticalunderstanding of and an ability to apply theories within a service context; d) demonstrate sensitivity todiversity and cultural differences; e) perform scholarly presentations that tie current issues to research andtheory; f) articulate the value of civic engagement.The learning outcomes of the major in Spanish and Community and Culture were approved by theDepartment in the 2006-2007 academic year.Spanish and Linguistics Major. Graduates will be able to: a) demonstrate a technical mastery of theSpanish language: its pronunciation (phonetics and phonology) its history (historical linguistics), itsstructure (syntax); b) demonstrate, within the context of a specialized topic how to do basic spokenlanguage research in Spanish linguistics, mainly Latin American Spanish and Chicano Spanish or LosAngeles vernacular; c) identify and analyze appropriate primary linguistic sources, mainly within theGenerative (i.e. formal) framework; d) acquire a working knowledge of scholarly discourse relative to aspecialized Spanish linguistics topic (phonology, syntax and historical linguistics); e) conceive andexecute a project that identifies and develops a specialized topic in Spanish linguistics that demonstratesanalytical skills in phonetics and phonology; f) sharpen critical and analytical skills regarding issuesrelated to the nature of language—its structure, its acquisition, its variation (dialects), and the way it isused in society.The learning outcomes for the Spanish and Linguistics major were developed by faculty in the field oflinguistics.Portuguese Major. Graduates in Portuguese will be able to: a) demonstrate oral, aural, and written masteryof the Portuguese language; b) demonstrate, within the context of a specialized topic in Portuguese andLuso-Brazilian studies, specific skills and expertise acquired in earlier coursework, including research,analysis and writing; c) identify and analyze appropriate primary sources; d) acquire a workingknowledge of scholarly discourse relative to a specialized topic; e) conceive and execute research projectsthat identify and engage with a specialized topic; f) engage with a community of scholars, presentingone's own work to peers and helping to further the work of those peers through discussion and critique.The learning outcomes for the Portuguese major were developed by faculty in the field of Portuguese.Spanish and Portuguese Major. Graduates in Spanish and Portuguese will be able to: a) demonstrate oral,aural, and written mastery of the Portuguese and Spanish languages; b) demonstrate, within the context ofa specialized topic in Portuguese and Luso-Brazilian studies and in Spanish and Spanish Americanstudies, specific skills and expertise acquired in earlier coursework, including research, analysis andwriting; c) identify and analyze appropriate primary sources; d) acquire a working knowledge of scholarlydiscourse relative to a specialized topic; e) conceive and execute research projects that identify andengage with a specialized topic; f) engage with a community of scholars, presenting one's own work topeers and helping to further the work of those peers through discussion and critique.The learning outcomes for the Spanish and Portuguese major were developed the Undergraduate AffairsCommittee as part of the restructuring of the major in response to Challenge 45.iii. Honors Program and Capstone ExperienceThe Department offers a <strong>Departmental</strong> Honors program which is open to Spanish majors who havecompleted eight upper division courses with at least a 3.5 grade point average.Also, the Department is in the process of developing opportunities for Capstone Seminars for all itsmajors to provide students with the opportunity to demonstrate their mastery of the skills proposed aslearning outcomes for their respective majors. The major in Spanish and Community and Culture already17

offers the opportunity of a capstone experience to its majors. The proposed Capstone feature for theSpanish major was approved by <strong>UCLA</strong>’s Undergraduate Council at its June 10, 2011 meeting.iv. The MinorsIn addition to the five areas of concentration offered to majors, the Department also offers studentsconcentrating on other disciplines the possibility of doing a minor in the Department. Currently, there arefour Minors. These Minors and their respective upper division course requirement are as follows:a) Spanish. Requirements: Sp 119 or Sp 120; Four courses in Spanish;b) Spanish Linguistics. Requirements: Sp 100-A; Sp 100-B; Two electives in Spanish Linguistics; Oneadditional course in Spanish.c) Portuguese. Requirements: Port 27; Five elective courses from Port 100-A to Port 199.d) Mexican Studies. Requirements: Three courses on Mexican Literature (Sp 135 to Sp 175); Twospecified elective courses from Anthropology, Chicano/a Studies; Ethno-musicology; Geography, orHistory.v. Students in the Majors and MinorsThe number of students majoring in our Department has increased slightly since the last review, from 160to 181 students. The number of students enrolled in our minors also increased since the last review, from204 to approximately 225 students. The current combined total of majors and minors ranges around 400to 450 students. A summary of majors and minors since 2002 is provided in the table below (more detailsare provided in Appendix A):Major and Minors : 2002 to 2011 (Spring Quarter Statistics)S11 S10 S09 S08 S07 S06 S05 S04 S03 S02Majors 181 176 179 168 186 196 NA 165 142 160Minors 225 282 320 270 256 267 NA 220 189 204Totals 406 458 499 438 442 463 NA 385 331 364The distribution of students per Majors since the last review is as follows (Spring Quarter numbers):Students Distribution per Majors: 2002 – 2011 (Spring Quarter Statistics)S11 S10 S09 S08 S07 S06 S05 S04 S03 S02Spanish 118 112 118 108 149 155 NA 126 105 126Spanish & Linguistics 19 25 21 27 24 27 NA 23 22 29Spanish & Community 35 24 23 15 NA NA NA NA NA NASpanish & Portuguese 7 10 16 17 9 8 NA 14 13 4Portuguese 1 5 1 1 4 6 NA 2 2 1Totals 181 176 179 168 186 196 NA 165 142 16018

Although the Department believes that it can increase significantly the number of Majors, the currentnumbers can be considered quite satisfactory given the mostly adverse circumstances we have had toconfront in recent years—the Department has suffered a significant net loss of permanent FTEs since thelast review, it has faced a reduction in the allocation of FTEs for Lecturers and TAs, and there is anadverse cyclical trend indicating a decline in the number of students majoring in language departments inthe country and at <strong>UCLA</strong>. Yet, as can be seen from the figures above, the number of students pursuingMajors and Minors in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese has actually increased in recent years.vi. Undergraduate EnrollmentsOverall undergraduate enrollments continued to be strong, despite a number of adverse factors. Theoverall total of students enrolled in undergraduate lower division and upper division courses offered bythe Department is currently approximately 5,000 students. This total includes enrollment by students whoare majors and minors in the Department, students from other <strong>UCLA</strong> departments, students attendingSummer Session courses on campus, and students taking courses in our Summer Travel Study ProgramsAbroad. The undergraduate enrollment statistics for the past five years are provided below.Undergraduate Enrollments (Years 2006-07 to 2010-2011)Year 10-11 09-10 08-09 07-08 06-07 05-06 04-05 03-04 02-03Spanish 3,261 3,693 3,738 3,848 3,857 3,768 3,946 4,611 4,204Portuguese 365 404 426 349 358 437 452 348 343Summer 819 907 789 879 865 681 578 576Total 4,916 5,071 4,986 5,094 5,070 5,071 5,537 5,123The enrollment figures above can be considered very positive, and reflect the ability of the faculty andstaff to run a large and successful undergraduate program consistently, and to respond actively to theadverse factors affecting the Department. Among the main difficulties faced by the undergraduateprogram were a net loss of permanent faculty FTEs, and budgetary cuts in our FTE allocation fortemporary Lecturers and TAs. The latter factor in particular had a negative impact on our enrollments. Ascan be seen from the table above, there was a significant decline in enrollments in Spanish classes in theacademic year 2010-2011 when compared to the previous academic years. The reason for this decline isthe budgetary cuts in our FTE allocation for Lecturers and TAs. This forced the Department to reduce thenumber of sections in Spanish language courses, which decreased from 38 sections in Fall 2009 to 28sections in Fall 2010—a decrease of 10 sections. The decrease in enrollments in Spanish is due solely tothese budget cuts—there are no other factors affecting enrollments in Spanish language courses. Almostall our Spanish language courses fill to capacity each quarter, and have substantial waitlists.The Department has attempted to attenuate the impact for students by increasing the enrollment caps by10% (from 25 to 28 students in Spanish 1-3, as of Fall 2010), and by offering a substantial program in theSummer Sessions on campus and in Travel Study programs abroad. In addition, the Department hasactively pursued external sources—the Brazilian government has been supporting a Lecturer forPortuguese; and the Spanish government has been supporting a Lecturer for Spanish. Thanks to anagreement with Catalan authorities, who agreed to provide a lecturer for Catalan, the Department hasbeen able to extend its language program by offering three levels of Catalan. In addition, the Departmenthas utilized funds raised through its extensive Summer programs to staff some of its undergraduatecourses where the need was more critical.19

vii. Language Program and TA TrainingThe teaching of the Spanish and Portuguese languages is carried out by Lecturers and TAs working underthe supervision of the Lower-Division Coordinator (Dr Juliet Falce-Robinson). Dr. Falce-Robinson isassisted by a TA Consultant (an experienced TA in the Department), who is funded partially by the Officeof Instructional Development and partially by the Department. As part of the undergraduate program, theLanguage Program is subordinated to the Vice-Chair for Undergraduate Studies, and is overseen by theUndergraduate Affairs Committee, which includes the Vice-chair for Undergraduate Affairs, four ladderfaculty, the Lower-Division Coordinator, the Department Chair (ex-officio), and student representatives.The Department has a TA training program, which includes a course (Sp 495) on language teachingmethods taught by the Lower-Division Coordinator, and includes observation of model classes. Undernormal circumstances, the graduate students take Sp 495 during their first quarter as TAs in ourDepartment. The Department’s TA training program can be considered outstanding. The Department’sTAs hold the <strong>UCLA</strong> record for the highest number of winners of the “Outstanding Teaching Assistants”awards granted by <strong>UCLA</strong>. This award is conferred once a year to about six TAs selected from alldepartments of the university.viii. Travel Study ProgramsThe Department has strongly responded to the goal of making <strong>UCLA</strong> a global university by increasingopportunities for students to study abroad through its four Summer Travel Study Programs. Theseprograms are in addition to the system-wide Education Abroad Program administered by a unitsubordinated to the UC Office of the President, which offers longer-term opportunities for UC students tostudy at a foreign university. Our Summer Travel Study Programs abroad are particularly importantbecause they offer to <strong>UCLA</strong> students, especially minority students, an opportunity to have a significantexperience abroad that many of them would not have otherwise. These programs focus on language andculture, and allow students to be immersed in the language and the culture of the country in which theystudy.The Department currently has four programs abroad (two in Spain, one in Mexico, and one in Brazil).Since the last review, the program in Puebla, Mexico was relocated to Merida, the program in Costa Ricawas discontinued, and in 2011 a new program was added in Barcelona, Spain. Enrollment statistics for thepast six years are given below.Summer Travel Study Programs – 2006 to 2011Year 2011** 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006Brazil/Salvador 29 35 36 35 53 38Spain/Granada 79 77 77 78 79 78Spain/Barcelona 30 NA NA NA NA NAMexico/Merida 31 34 26 23* 23* 26*Costa Rica/S. Jose NA NA 19 21 30 32Totals 167 146 158 157 185 174(*Prior Program at Puebla, Mexico; **preliminary numbers , based on information provided by theOffice of Internal Education).20

Student demand for these programs has been strong, and our Department has the highest enrollments forprograms of this kind at <strong>UCLA</strong>. Enrollments range from 150 to 180 students, with gross revenues ofapproximately US $ 800,000 to US$ 1,000,000 per summer. Some of these revenues have been sharedwith the Department and have served to attenuate somewhat the impact of the repeated budgetary cutsthat would otherwise seriously impair our program.ix. Collaboration with Other <strong>UCLA</strong> Departments and ProgramsIn addition to supporting the various Department majors and minors, the courses offered by theDepartment also provide key support for the majors offered by other <strong>UCLA</strong> departments and interdepartmentalprograms—particularly the majors offered by the interdepartmental programs in LatinAmerican Studies and European Studies, as well as the Departments of Chicano/Chicana Studies,Comparative Literature, and Linguistics.The program in Portuguese, with its focus on Brazil, has played an instrumental role in the recent renewalof the Title VI grant administered by the <strong>UCLA</strong> Latin American Institute—a multi-year grant ofapproximately US$ 4 million for the study of “critical languages” of Latin America. As in the past, theDepartment’s course offerings in Brazilian Portuguese—a listed “critical language”—played a decisiverole in obtaining this award. In addition, the Department currently helps sustain the program inQuechua—another critical language of Latin America—which is funded by the Title VI grant, by payingpart of the Quechua lecturer’s salary.x. Summary of Senior Survey ResultsMatthew Swanson, the Department’s undergraduate counselor, conducted a senior survey in Spring 2011.Forty-two students responded to the survey. The survey posed a number of broad questions designed togauge student satisfaction, request recommendations for improving our programs, and collect informationabout the backgrounds and future plans of our students. Students were not asked to score our programs.Some overall conclusions can be derived from the responses. (See Appendix B for all student responses tothe survey).A large number of students mention a “love” of the Spanish language and/or the literatures and cultures ofSpanish-speaking peoples as the reason for majoring in our Department. Many students state that themajor connected them to their cultural heritage. Others were inspired to undertake a major in ourDepartment by a high school teacher or by specific professors in the Department of Spanish andPortuguese.In response to a question about the most enjoyable aspect of the major, many students mentioned the“great” literature and film studied in the Department’s classes, the variety of classes offered, and thesupport from the faculty. Professors in the Department are described as “warm,” “caring,” “accessible,”“approachable,” and “friendly.” The opportunity to study abroad is also regularly mentioned as anattractive feature of our majors.Aspects that can be improved of the Spanish and Portuguese majors include offering fewer “literaturebased”classes, bringing back some of the classes that were part of the old Spanish major, such as therequired class on Don Quijote, and making sure that classes are offered in Spanish, not English.An overwhelming majority of the respondents (approximately 75%) mention graduate school as part oftheir post-graduation plans. Fields that students plan to study in graduate school range from Spanish andMuseum Studies to law, medicine and pharmacy. Several students mention that they will be going toSpain to teach English, some of them as part of the Language and Culture Assistants programadministered by the Centro Español de Recursos in Los Angeles. Some students have jobs lined up,others are still looking. Jobs mentioned include working for a school district (no specific position isidentified), working for an event planning and tech company that does business in Latin America (again,21

no specific job function is stated), and working as an English Teaching Assistant for the French Ministryof Foreign Affairs in Paris.xi. Strengths and WeaknessesIn our collective view, the Department Majors and Minors continue to be strong and to attract excellentstudents. The number of students majoring and minoring in our Department has experienced an increase,despite the current adverse trend facing the Humanities. The recent College policy to standardize thenumber of upper division courses around forty five units (“Challenge 45”) and the Department’s revisionsto comply with this policy bring the course requirements for our majors more in line with other majors at<strong>UCLA</strong>, which should facilitate the recruitment of students into our majors.Most of our new majors were put into place during the academic year that has just concluded. TheDepartment Chair will be meeting with colleagues during the summer break to assess strengths andweaknesses of the required courses in the new Spanish major. The senior survey indicates that somestudents regret that certain courses—such as the Don Quijote class—are no longer required for the major.However, the substantial reduction of the faculty in the field of Golden Age literature makes it impossibleto offer such a course with sufficient frequency to make it a requirement for the major. We note,furthermore, that other students seem pleased with the greater flexibility offered by the new majors.Another frequent complaint is that the Department offers too many courses in English. While we takethis complaint seriously, we believe that it is overstated and possibly based on a misunderstanding of howour curriculum works. Large classes offered for General Education credit (such as Sp 44-Latin AmericanCulture) have to be taught in English in order to meet the requirements of the GE program. Moreover, theDepartment invariably offers discussion sections in Spanish as part of these courses. At the upperdivisionlevel, the Department occasionally offers a course in English in order to attract a wider range ofstudents. However, the vast majority of our classes are taught in Spanish. Finally, we would like toaddress the complaint that our majors are too “literature-based.” This is a complaint voiced by foreignlanguage majors all over the country; it results from a disconnect between the reasons for whichundergraduate students choose to major in a foreign language and the areas in which professors in thesefields receive their training. While the complaint needs to be taken seriously, it is not at all clear that theproblem is easy to remedy. Let us note, to begin with, that courses in the Department of Spanish andPortuguese are already highly interdisciplinary, with students being offered the opportunity to study filmand other arts, as well as take classes with a strong emphasis on history and politics. But when studentsask for courses, let’s say, on architecture or in the field of journalism, taught in Spanish by professors inthe Department of Spanish and Portuguese, they are in effect asking that our Department become amicrocosm of the university as a whole, with classes being offered in Spanish across the entire range ofthe curriculum. This would necessitate a drastic reconceptualization of the university as such. With ourtop administrators apparently eager to downgrade rather than strengthen the Department of Spanish andPortuguese, we are very far from being in a position to respond to student expectations with regard toclasses taught in Spanish.Although the undergraduate program has been affected by budgetary cuts, the department has takeneffective steps to provide undergraduate majors with the courses they need to graduate within theexpected time to degree. Some faculty deferred their sabbaticals, enrollment caps in some Spanishlanguage courses were slightly raised (by 10%) to accommodate for reduced sessions, more classes wereoffered in the Summer, and summer money was used to hire additional visiting faculty. With thesemeasures the Department has ensured the necessary availability of courses needed for students to graduateon time.The Department’s Summer Session programs are also very successful. Participation of the ladder facultyin these programs has been strong, which insures the quality of the courses. Second, since most of thecourses satisfy degree requirements, students have the opportunity to accelerate their academic progresstowards their degree. Third, the extensive language program offered in the Summer enables many22

students to fulfill their language requirements during the Summer, diminishing the impact on ourlanguage classes during the academic year when we have more difficulty in staffing the courses due tobudgetary cuts. Likewise, the Summer Travel-Study Programs organized by the Department inconjunction with the Office of International Education are very successful. These programs are directedby a <strong>UCLA</strong> faculty member to assure their academic integrity. Students also benefit from a directexposure to the language and culture of the countries they study, and from a concrete experience abroadwhich better prepares them for the increasingly globalized market place. Lastly, these programs have alsoprovided the Department with an extra source of revenues to shore up its academic programs, helpingattenuate the impact of the successive budgetary cuts experienced by the Department over the past severalyears.We believe our undergraduate program is strong and that its shortcomings are more than offset by itsaccomplishments. The most pressing issue faced by the undergraduate program is that the Department hashad a net loss of several FTEs for ladder faculty and of soft FTEs for lecturers and TAs. This has resultedin a significant reduction of course offerings in language classes (a reduction of 10 classes), and forcedthe adoption of contingency measures by the Department to shore up the program. We are cognizant ofthe current budgetary constraints, but it seems clear that unless some of these FTEs are restored soon wemay reach a critical point where the integrity of our programs will be compromised.D. THE GRADUATE PROGRAMI. OverviewOur current graduate program was approved in Fall 2002. Its aim was to offer our graduate students awell-rounded education in their area of specialization (the study of the literatures, languages, and culturesof the Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking world) and to prepare them for a career as professors at thecollege level. With that goal in mind, we stopped offering students the option of entering the programsolely to pursue a M.A. degree (although a student may earn a terminal M.A. degree), and divided theprogram into two phases. The purpose of the Preliminary phase is to offer our students a generalknowledge of their field of study, an understanding of the connections between different areas ofspecialization, and an understanding of the evolution of literary movements as part of a historicalcontinuum. In addition, the program exposes students to different theoretical and methodologicalapproaches to the study of literature and linguistics. At the end of the second year, students take thePreliminary Exams and the entire body of ladder faculty decides whether they receive a terminal MAdegree or are allowed to advance to the doctoral phase of the program. In the second phase, studentsnarrow their field of interest while they aim towards the writing of the dissertation. The goal of thesecond phase is to form scholars who can contribute to the academic community with creative andoriginal research in their field of specialization.The new program was evaluated very positively in the last eight-year review. One of the externalreviewers said in his report that “students have received these changes with acclaim” (JH, p. 5). Thereviewer himself was very much in favor of the new program, arguing that the “state of the professionmakes almost certain that most schools would need instructors who are proficient in different fields, bothin Peninsular and Latin American literature, and the new structure of the program increases in this waythe opportunities for employment” (JH, p. 5). Current graduate students also perceive these changes inpositive terms. In their answers to a Survey that was distributed in May 2011, a majority considered thattaking courses in different subfields and having Preliminary exams based on a reading list is good fortheir education (see summary of the survey’s results below; see Appendix E for all survey responses). Inthis regard, our Department belongs to a selective group of departments of S&P that have a similargraduate program. Of the twenty top-ranked departments in the 2010 NRC ranking, at least twelve haveMA exams based on a comprehensive reading list similar to our own.The Department offers graduate courses in the areas of Spanish and Spanish American literatures, whichhave been divided into seven groups that correspond to the seven main subfields of the preliminary phase:23