The Innocence Project in Print - Summer 2011 (PDF)

The Innocence Project in Print - Summer 2011 (PDF)

The Innocence Project in Print - Summer 2011 (PDF)

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

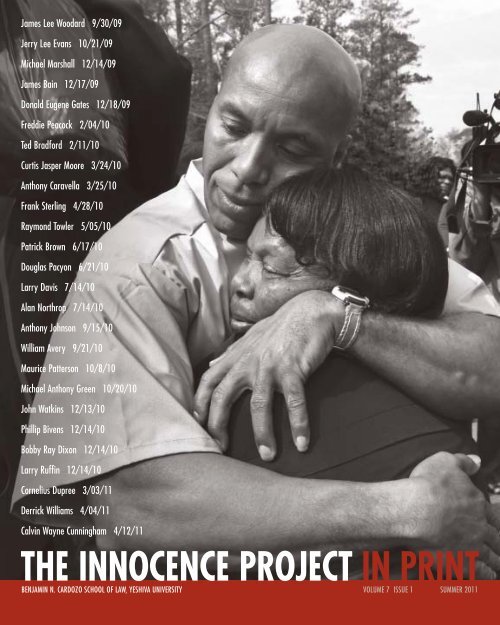

James Lee Woodard 9/30/09Jerry Lee Evans 10/21/09Michael Marshall 12/14/09James Ba<strong>in</strong> 12/17/09Donald Eugene Gates 12/18/09Freddie Peacock 2/04/10Ted Bradford 2/11/10Curtis Jasper Moore 3/24/10Anthony Caravella 3/25/10Frank Sterl<strong>in</strong>g 4/28/10Raymond Towler 5/05/10Patrick Brown 6/17/10Douglas Pacyon 6/21/10Larry Davis 7/14/10Alan Northrop 7/14/10Anthony Johnson 9/15/10William Avery 9/21/10Maurice Patterson 10/8/10Michael Anthony Green 10/20/10John Watk<strong>in</strong>s 12/13/10Phillip Bivens 12/14/10Bobby Ray Dixon 12/14/10Larry Ruff<strong>in</strong> 12/14/10Cornelius Dupree 3/03/11Derrick Williams 4/04/11Calv<strong>in</strong> Wayne Cunn<strong>in</strong>gham 4/12/11THE INNOCENCE PROJECT IN PRINTBENJAMIN N. CARDOZO SCHOOL OF LAW, YESHIVA UNIVERSITYVOLUME 7 ISSUE 1 SUMMER <strong>2011</strong>

IN THIS ISSUEBOARD OF DIRECTORSMichelle AdamsLaura ArnoldGordon DuGanSenator Rodney EllisBoard ChairJason FlomJohn GrishamCalv<strong>in</strong> C. Johnson, Jr.Dr. Eric S. LanderHon. Janet RenoDirector EmeritusRossana RosadoMatthew RothmanStephen SchulteBoard Vice ChairBonnie Ste<strong>in</strong>gartChief Darrel StephensAndrew H. Tananbaum, Esq.Jack TaylorBoard TreasurerFEATURESA CASE OF MISTAKEN IDENTITY..............................................................4WHO WILL PROSECUTE THE PROSECUTORS?.......................................9STRENGTH IN NUMBERS ........................................................................12IN THEIR OWN WORDS:Q & A WITH FALSE CONFESSION EXPERTRICHARD LEO .................................................................................16DEPARTMENTSLETTER FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR..............................................3EXONERATION NATION ..........................................................................18INNOCENCE PROJECT NEWS..................................................................20INNOCENCE BY THE NUMBERS:INEFFECTIVE DEFENSE....................................................................22ON THE COVER: ON MARCH 21, HIS 46TH BIRTHDAY, THOMAS HAYNESWORTH WAS RELEASED AFTER SPENDING 27YEARS IN PRISON FOR CRIMES HE DIDN’T COMMIT. HERE, HE HUGS HIS MOTHER, DELORES HAYNESWORTH, WHILEA CAMERA CREW LOOKS ON.916PHOTO CREDITS: COVER, Richmond Times-Dispatch; PAGE 3, www.heatherconley.com; PAGE 6, Richmond Times-Dispatch; PAGE 9, Tony Deifell;PAGE 12, Dottie Stover/University of C<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>nati Photography; PAGE 13, Greg Kendall-Ball; PAGE 14, Diane Bladecki; PAGE 18, PaulVidela/Bradenton HeraldTHE NAMES THAT FOLLOW BELOW ARE THOSE OF THE 271 WRONGFULLY CONVICTED PEOPLE WHOM DNAHELPED EXONERATE, FOLLOWED BY THE YEARS OF THEIR CONVICTION AND EXONERATION.GARY DOTSON 1979 TO 1989 • DAVID VASQUEZ 1985 TO 1989 • EDWARD GREEN 1990 TO 1990 • BRUCE NELSON 1982 TO 1991 • CHARLES DABBS 1984 TO 1991 • GLEN WOODALL 1987 TO 1992 • JOE JONES 1986 TO1992 • STEVEN LINSCOTT 1982 TO 1992 • LEONARD CALLACE 1987 TO 1992 • KERRY KOTLER 1982 TO 1992 • WALTER SNYDER 1986 TO 1993 • KIRK BLOODSWORTH 1985 TO 1993 • DWAYNE SCRUGGS 1986 TO 1993 •MARK D. BRAVO 1990 TO 1994 • DALE BRISON 1990 TO 1994 • GILBERT ALEJANDRO 1990 TO 1994 • FREDERICK DAYE 1984 TO 1994 • EDWARD HONAKER 1985 TO 1994 • BRIAN PISZCZEK 1991 TO 1994 • RONNIE

FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR3LOOKING BACK, LOOKING AHEADWhen we met with our colleagues from the <strong>Innocence</strong> Network this spr<strong>in</strong>g, we felt that,beyond just participat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a three-day conference, we were mak<strong>in</strong>g history. Neverbefore had so many exonerated people – and their family members and advocates –come together from all across the country and the world. <strong>The</strong> conference re<strong>in</strong>vigoratedour efforts and challenged us to th<strong>in</strong>k bigger.Every exoneree – whether male or female, black or white, from the big city or a smalltown – shares the life-alter<strong>in</strong>g experience of wrongful conviction. (Read more aboutthe exonerees who attended the conference <strong>in</strong> “Strength <strong>in</strong> Numbers” start<strong>in</strong>g onpage 12.) And just as the crim<strong>in</strong>al justice system repeats the same mistakes, wrongfulconviction cases share identifiable similarities.Seventy-five percent of those exonerated through DNA test<strong>in</strong>g were misidentifiedby an eyewitness. (As you’ll read <strong>in</strong> “A Case of Mistaken Identity” on page 4, eyewitnessmisidentification is the lead<strong>in</strong>g cause of wrongful convictions.) Twenty-five percent oftheir cases <strong>in</strong>volved a false confession or admission. (False confession expert RichardLeo expla<strong>in</strong>s how this can happen <strong>in</strong> “In <strong>The</strong>ir Own Words,” on page 16.) Many otherwrongful convictions <strong>in</strong>volved faulty forensics, jailhouse <strong>in</strong>formants, prosecutorial andpolice misconduct and <strong>in</strong>effective defense. (For more about prosecutorial misconduct,see “Who Will Prosecute the Prosecutors?” on page 9. For more about <strong>in</strong>effectivedefense, see “<strong>Innocence</strong> by the Numbers” on page 22.)In order to confront these systemic flaws, the <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> helped foundand develop the <strong>Innocence</strong> Network, an affiliation of organizations dedicated tooverturn<strong>in</strong>g wrongful convictions and improv<strong>in</strong>g the crim<strong>in</strong>al justice system. Althougheach of the 55 U.S. <strong>Innocence</strong> Network member organizations operates <strong>in</strong>dependently– from Texas to Ohio to Wash<strong>in</strong>gton State – we help to coord<strong>in</strong>ate policy reformefforts. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> provides strategic support, shapes the reform agendaand collaborates with the member organizations. Work<strong>in</strong>g together, we buildrelationships with state lawmakers and local law enforcement – all while keep<strong>in</strong>gour bold national agenda <strong>in</strong>tact.It’s an effort that began many years ago with only a few, scattered exonerations. Today,over 270 people have been exonerated through DNA test<strong>in</strong>g, and wrongful convictionshave been overturned <strong>in</strong> hundreds of other cases by other means. We have revealedstartl<strong>in</strong>g flaws <strong>in</strong> the crim<strong>in</strong>al justice system and laid the groundwork for systemicchange. How many more <strong>in</strong>nocent prisoners will be freed <strong>in</strong> the years to come? Howwill the system be transformed? We can’t wait to f<strong>in</strong>d out.Maddy deLoneExecutive DirectorBULLOCK 1984 TO 1994 • DAVID SHEPHARD 1984 TO 1995 • TERRY CHALMERS 1987 TO 1995 • RONALD COTTON 1985, 1987 TO 1995 • ROLANDO CRUZ 1985 TO 1995 • ALEJANDRO HERNANDEZ 1985 TO 1995 •WILLIAM O. HARRIS 1987 TO 1995 • DEWEY DAVIS 1987 TO 1995 • GERALD DAVIS 1986 TO 1995 • WALTER D. SMITH 1986 TO 1996 • VINCENT MOTO 1987 TO 1996 • STEVEN TONEY 1983 TO 1996 • RICHARD JOHNSON1992 TO 1996 • THOMAS WEBB 1983 TO 1996 • KEVIN GREEN 1980 TO 1996 • VERNEAL JIMERSON 1985 TO 1996 • KENNETH ADAMS 1978 TO 1996 • WILLIE RAINGE 1978, 1987 TO 1996 • DENNIS WILLIAMS 1978,

4A CASE OFMISTAKEN IDENTITYNationwide, of the 271 cases of wrongful conviction overturned throughDNA test<strong>in</strong>g, 202 <strong>in</strong>volved eyewitness misidentification. An ongo<strong>in</strong>g<strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> case tells the story beh<strong>in</strong>d the number.A YOUNG MAN’S FUTURE UPENDEDIn early 1984, a serial rapist began terroriz<strong>in</strong>g white women <strong>in</strong> Richmond, Virg<strong>in</strong>ia.Police apprehended Thomas Haynesworth, and he was convicted of three crimes. Butas the city breathed a sigh of relief, the attacks cont<strong>in</strong>ued. <strong>The</strong> perpetrator, emboldened,began call<strong>in</strong>g himself the “black n<strong>in</strong>ja.” F<strong>in</strong>ally, towards the end of the year, Leon Daviswas arrested and convicted, and the “black n<strong>in</strong>ja” never struck aga<strong>in</strong>.THOMAS HAYNESWORTH (LEFT) WAS MISIDENTIFIED FIVETIMES AS THE PERPETRATOR OF A SERIES OF RAPES THATWERE ACTUALLY COMMITTED BY LEON DAVIS (RIGHT).All of the crimes were perpetrated with<strong>in</strong> the same one-mile radius, all targeted the samevictim demographic and all followed a similar pattern. Was there a connection between1987 TO 1996 • FREDRIC SAECKER 1990 TO 1996 • VICTOR ORTIZ 1984 TO 1996 • TROY WEBB 1989 TO 1996 • TIMOTHY DURHAM 1993 TO 1997• ANTHONY HICKS 1991 TO 1997 • KEITH BROWN 1993 TO 1997 •MARVIN MITCHELL 1990 TO 1997 • CHESTER BAUER 1983 TO 1997 • DONALD REYNOLDS 1988 TO 1997 • BILLY WARDELL 1988 TO 1997 • BEN SALAZAR 1992 TO 1997 • KEVIN BYRD 1985 TO 1997 • ROBERT MILLER1988 TO 1998 • PERRY MITCHELL 1984 TO 1998 • RONNIE MAHAN 1986 TO 1998 • DALE MAHAN 1986 TO 1998 • DAVID A. GRAY 1978 TO 1999 • HABIB W. ABDAL 1983 TO 1999 • ANTHONY GRAY 1991 TO 1999 •

A CASE OF MISTAKEN IDENTITY5Haynesworth and Davis? Could Davis have committed all of the crimes? If police andprosecutors asked these questions, they never bothered to f<strong>in</strong>d the answers.Thomas Haynesworth became a suspect when one of the victims spotted him walk<strong>in</strong>gnear his home and identified him as the attacker. He was 18 years old and had nocrim<strong>in</strong>al record. His photo was shown to victims of similar crimes. Five victims eventuallyidentified him – the one on the street and four <strong>in</strong> photo arrays. In one of the crimes,the victim, who was 5’ 8”, had orig<strong>in</strong>ally described the perpetrator as “taller than me.”In another, the perpetrator was described as 5’ 10”. Haynesworth is only 5’6 1/2”; Davis is5’10”. Haynesworth was ultimately convicted of two rapes and one attempted robberyand abduction.Haynesworth, a young man with dreams and ambitions, was suddenly a convicted serialrapist. He says “I thought they were go<strong>in</strong>g to see that they made a mistake and correct it.It’s been 27 years, and I’m still wait<strong>in</strong>g.”In Haynesworth’s first letter to the <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong>, he writes: “<strong>The</strong>re is an <strong>in</strong>matenamed Leon Davis who is <strong>in</strong> prison for some of the same th<strong>in</strong>gs I’m charged with, andhe was liv<strong>in</strong>g down the street from me <strong>in</strong> Richmond, Virg<strong>in</strong>ia… . I will bet my life this isthe man who committed these crimes… . A simple blood test could solve this problemright away. Just get my DNA tested, and you will see I’m <strong>in</strong>nocent of these crimes.”RELEASED, BUT NOT FREEIn Virg<strong>in</strong>ia, post-conviction DNA test<strong>in</strong>g has refuted eyewitness evidence <strong>in</strong> ten cases.<strong>The</strong>se ten people were exonerated after spend<strong>in</strong>g a comb<strong>in</strong>ed total of 128 years <strong>in</strong>prison. Now Haynesworth’s case makes 11. DNA test<strong>in</strong>g of biological evidence from theperpetrator l<strong>in</strong>ks Leon Davis to two of the crimes that Haynesworth was charged with,one that resulted <strong>in</strong> his conviction and one that resulted <strong>in</strong> his acquittal. Haynesworthhas been exonerated of that one crime, but the other two convictions still stand becausebiological evidence is not available for post-conviction DNA test<strong>in</strong>g.“THERE IS AN INMATE NAMEDLEON DAVIS WHO IS IN PRISONFOR SOME OF THE SAMETHINGS I’M CHARGED WITH….I WILL BET MY LIFE THIS ISTHE MAN WHO COMMITTEDTHESE CRIMES.”– From a letter Thomas Haynesworth wroteto the <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> from prisonEven without the DNA evidence, it’s pla<strong>in</strong> to see that Haynesworth did not perpetrateany of these crimes. <strong>The</strong> manner <strong>in</strong> which the rapes and attempted rapes werecommitted is consistent with Davis’ modus operandi. All of the victims provided similardescriptions of the perpetrator. Davis matches these descriptions, Haynesworth does not.In February, local prosecutors jo<strong>in</strong>ed the <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong>, the Mid-Atlantic <strong>Innocence</strong><strong>Project</strong> and the law firm of Hogan Lovells <strong>in</strong> an effort to overturn all three convictions.<strong>The</strong> Virg<strong>in</strong>ia Attorney General also supports Haynesworth’s motion for exoneration onall charges. Even though his motion is unopposed, the Virg<strong>in</strong>ia Court of Appeals stillhasn’t ruled on it. Without a writ of <strong>in</strong>nocence or a pardon, Haynesworth cannot becleared.At the Governor’s request, and the <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong>’s urg<strong>in</strong>g, Haynesworth wasreleased this March on his 46th birthday. S<strong>in</strong>ce then, the Virg<strong>in</strong>ia Attorney General’sJOHN WILLIS 1993 TO 1999 • RON WILLIAMSON 1988 TO 1999 • DENNIS FRITZ 1988 TO 1999 • CALVIN JOHNSON 1983 TO 1999 • JAMES RICHARDSON 1989 TO 1999 • RONALD JONES 1989 TO 1999 • CLYDE CHARLES1982 TO 1999 • MCKINLEY CROMEDY 1994 TO 1999 • LARRY HOLDREN 1984 TO 2000 • LARRY YOUNGBLOOD 1985 TO 2000 • WILLIE NESMITH 1982 TO 2000 • JAMES O’DONNELL 1998 TO 2000 • FRANK L. SMITH 1986TO 2000 • HERMAN ATKINS 1988 TO 2000 • NEIL MILLER 1990 TO 2000 • A.B. BUTLER 1983 TO 2000 • ARMAND VILLASANA 1999 TO 2000 • WILLIAM GREGORY 1993 TO 2000 • ERIC SARSFIELD 1987 TO 2000 • JERRY

6Office has employed him as an office technician, a job that he says he enjoys because“it makes me feel like part of society aga<strong>in</strong>.” But, sadly, Haynesworth is still under statesupervision. As long as he awaits a decision from the court, he will cont<strong>in</strong>ue to be onparole, permitted only to leave the house to go to his job.THE EYES DECEIVEIn the rape that Haynesworth has been exonerated of, the rape victim was reported assay<strong>in</strong>g: “I would have staked my life on the fact that I knew exactly who had done this.”How could she have been so sure and yet so wrong? And how could multiple witnesseshave misidentified the same <strong>in</strong>nocent man?Scientific research about eyewitness identification has advanced <strong>in</strong> the last century, butone early discovery rema<strong>in</strong>s undisputed: memory is mutable. Witnesses will naturallylook to outside sources – law enforcement, media, or other witnesses – for reassuranceand guidance. A suggestion from law enforcement, whether <strong>in</strong>tentional orun<strong>in</strong>tentional, can have the same effect that contam<strong>in</strong>ation of forensic evidence has –it becomes unreliable.THOMAS HAYNESWORTH WALKS IN THE FRONT DOOR OF HISMOTHER’S HOUSE IN RICHMOND, VIRGINIA, ON THE DAY OFHIS RELEASE FROM THE GREENSVILLE CORRECTIONAL CENTER.<strong>The</strong> <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> encourages state legislatures to mandate the adoption of uniformidentification procedures and advocates a specific package of best practices that havebeen proven to reduce the rate of misidentification. (For more about these reforms, seethe sidebar on page 8.) Police identification procedures vary from state to state and evenjurisdiction to jurisdiction. Many police departments don’t have written policies at all.WATKINS 1986 TO 2000 • ROY CRINER 1990 TO 2000 • ANTHONY ROBINSON 1987 TO 2000 • CARLOS LAVERNIA 1985 TO 2000 • EARL WASHINGTON 1984 TO 2000 • LESLY JEAN 1982 TO 2001 • DAVID S. POPE 1986TO 2001 • KENNY WATERS 1983 TO 2001 • DANNY BROWN 1982 TO 2001 • JEFFREY PIERCE 1986 TO 2001 • JERRY F. TOWNSEND 1980 TO 2001 • CALVIN WASHINGTON 1987 TO 2001 • EDUARDO VELASQUEZ 1988 TO2001 • CHARLES I. FAIN 1983 TO 2001 • MICHAEL GREEN 1988 TO 2001 • JOHN DIXON 1991 TO 2001 • CALVIN OLLINS 1988 TO 2001 • LARRY OLLINS 1988 TO 2001 • MARCELLIUS BRADFORD 1988 TO 2001 • OMAR

A CASE OF MISTAKEN IDENTITY7Instead, procedures are passed down from senior officers to junior officers and maynot be based on scientific research or best practices. Research has shown that simpleprocedural errors, such as fail<strong>in</strong>g to tell the witness that the perpetrator may not bepresent <strong>in</strong> the l<strong>in</strong>eup, can result <strong>in</strong> misidentifications and set the stage for a wrongfulconviction.RECOMMENDATIONS FOR REFORMEleven states, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Virg<strong>in</strong>ia, have statewide laws govern<strong>in</strong>g l<strong>in</strong>eup procedures.Earlier this year, Virg<strong>in</strong>ia lawmakers, at the urg<strong>in</strong>g of the <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> and otherstakeholders, passed a law that will require police departments to adopt eyewitnessidentification procedures consistent with best practices. <strong>The</strong> Virg<strong>in</strong>ia State CrimeCommission has committed to address<strong>in</strong>g the issue by plann<strong>in</strong>g an audit to <strong>in</strong>vestigatewhether the procedures are <strong>in</strong> place. If the procedures are scientifically sound, the newlaw could be a big step toward strengthen<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>tegrity of eyewitness evidence <strong>in</strong>Virg<strong>in</strong>ia and prevent<strong>in</strong>g what happened to Haynesworth from happen<strong>in</strong>g aga<strong>in</strong>.New Jersey led the vanguard <strong>in</strong> eyewitness identification reform <strong>in</strong> 2001. But a 2004conviction revealed that the new procedures mandated by the reforms were not alwaysbe<strong>in</strong>g practiced. Larry Henderson’s conviction, based largely on faulty eyewitnessidentification, prompted the state Supreme Court to consider a major overhaul oflegal standards for eyewitness identification evidence.<strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> Co-Director Barry Scheck argued the case before the court earlierthis year. At issue is the legal test used by 48 states and the federal courts to determ<strong>in</strong>ethe reliability and admissibility of eyewitness testimony. People v. Henderson could changethe way that cases <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g eyewitness identification are litigated <strong>in</strong> New Jersey andcould ultimately compel reform <strong>in</strong> other states as well.<strong>The</strong> majority of states still have no laws govern<strong>in</strong>g eyewitness identification procedures,and the <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> is work<strong>in</strong>g with law enforcement and lawmakers to affectchange <strong>in</strong> this area. In Texas – where more people have been misidentified, wrongfullyconvicted, and exonerated through DNA test<strong>in</strong>g than any other state – exonerees haveteamed with the <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> and local advocates to support eyewitnessidentification reforms that passed <strong>in</strong> June.Just a week after he was declared <strong>in</strong>nocent <strong>in</strong> early <strong>2011</strong>, Cornelius Dupree jo<strong>in</strong>ed overa dozen Texas exonerees to testify at the state capitol <strong>in</strong> favor of eyewitness identificationreform. Dupree was misidentified as one of two men who perpetrated a Dallas area rapeand robbery. After 30 years beh<strong>in</strong>d bars, Dupree has served more time wrongfully thananyone else <strong>in</strong> the state.CORNELIUS DUPREE, BEFORE HIS WRONGFUL CONVICTION ATAGE 19 (TOP), AND AFTER HIS 30 YEARS OF WRONGFULIMPRISONMENT AT AGE 51, WITH HIS WIFE, SELMA DUPREE(BOTTOM).“It’s not go<strong>in</strong>g to be a perfect system,” Dupree told the legislators, “but we need tom<strong>in</strong>imize the amount of people fall<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to the same trap I did.” Dur<strong>in</strong>g his 30 yearsof wrongful imprisonment, Dupree lost both parents and was not able to go to theirfunerals. He might have been released on parole <strong>in</strong> 2004 if he had been will<strong>in</strong>g toSAUNDERS 1988 TO 2001 • LARRY MAYES 1982 TO 2001 • RICHARD ALEXANDER 1998 TO 2001 • MARK WEBB 1987 TO 2001 • LEONARD MCSHERRY 1988 TO 2001 • ULYSSES R. CHARLES 1984 TO 2001 • BRUCEGODSCHALK 1987 TO 2002 • RAY KRONE 1992 TO 2002 • HECTOR GONZALEZ 1996 TO 2002 • ALEJANDRO DOMINGUEZ 1990 TO 2002 • CLARK MCMILLAN 1980 TO 2002 • LARRY JOHNSON 1984 TO 2002 • CHRISTOPHEROCHOA 1989 TO 2002 • VICTOR L. THOMAS 1986 TO 2002 • MARVIN ANDERSON 1982 TO 2002 • EDDIE J. LLOYD 1985 TO 2002 • JIMMY R. BROMGARD 1987 TO 2002 • ALBERT JOHNSON 1992 TO 2002 • SAMUEL SCOTT

8 THE INNOCENCE PROJECT IN PRINTattend a sex offender treatment program, but he refused. He and his longtime love,Selma, wed the day after his release. <strong>The</strong>y had dated for 20 years. (For more aboutDupree, see “Strength <strong>in</strong> Numbers” on page 12.)For all that Dupree and Haynesworth have endured, they are only two of the over 200people who have been misidentified and proven <strong>in</strong>nocent through DNA test<strong>in</strong>g afteryears or decades. S<strong>in</strong>ce DNA test<strong>in</strong>g is not available <strong>in</strong> most cases, we can never knowhow many people are wrongfully imprisoned because they were mistaken for somebodyelse. But we do know how to address the problem. Decades of scientific research hasshown that the rate of misidentifications can be reduced through simple reforms. Thatmeans fewer wrongful convictions and more real perpetrators apprehended before theyhave a chance to reoffend. EYEWITNESS IDENTIFICATION PROCEDURAL REFORMSAs recommended by the <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> and lead<strong>in</strong>g national justice andlegal organizations <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the National Institute of Justice and the AmericanBar Association. DOUBLE-BLIND ADMINISTRATIONPhotos or l<strong>in</strong>eup members should bepresented by an adm<strong>in</strong>istrator who doesnot know who the suspect is. And thewitness should be told that theadm<strong>in</strong>istrator doesn’t know. PROPER LINEUP COMPOSITION“Fillers” (the non-suspects <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> al<strong>in</strong>eup) should resemble the eyewitness’sdescription of the perpetrator, and thesuspect should not stand out. Also, al<strong>in</strong>eup should not conta<strong>in</strong> more thanone suspect. CONFIDENCE STATEMENTSAt the time of the identification, theeyewitness should provide a statement<strong>in</strong> her own words <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g her levelof confidence <strong>in</strong> the identification. RECORDING THE PROCEDUREIdentification procedures should bevideotaped. SEQUENTIAL PRESENTATION(Optional) L<strong>in</strong>eup members arepresented one at a time (by a “bl<strong>in</strong>d”adm<strong>in</strong>istrator) <strong>in</strong>stead of side by side. INSTRUCTIONS TO THE WITNESS<strong>The</strong> person view<strong>in</strong>g a l<strong>in</strong>eup should betold that the perpetrator may not be <strong>in</strong>the l<strong>in</strong>eup and that the <strong>in</strong>vestigation willcont<strong>in</strong>ue regardless of whether anidentification is made.1987 TO 2002 • DOUGLAS ECHOLS 1987 TO 2002 • BERNARD WEBSTER 1983 TO 2002 • DAVID B. SUTHERLIN 1985 TO 2002 • ARVIN MCGEE 1989 TO 2002 • ANTRON MCCRAY 1990 TO 2002 • KEVIN RICHARDSON 1990TO 2002 • YUSEF SALAAM 1990 TO 2002 • RAYMOND SANTANA 1990 TO 2002 • KOREY WISE 1990 TO 2002 • PAULA GRAY 1978 TO 2002 • RICHARD DANZIGER 1990 TO 2002 • JULIUS RUFFIN 1982 TO 2003 • GENEBIBBINS 1987 TO 2003 • EDDIE J. LOWERY 1982 TO 2003 • DENNIS MAHER 1984 TO 2003 • MICHAEL MERCER 1992 TO 2003 • PAUL D. KORDONOWY 1990 TO 2003 • DANA HOLLAND 1995 TO 2003 • KENNETH WYNIEMKO

9WHO WILL PROSECUTETHE PROSECUTORS?A recent Supreme Court decision begs the question of what, if anyth<strong>in</strong>g,prosecutors can be held accountable for.In 1985, John Thompson, a 22-year-old father of two, was wrongfully convicted ofmurder and sent to death row at Angola State Penitentiary <strong>in</strong> Louisiana. While fac<strong>in</strong>ghis seventh execution date, a private <strong>in</strong>vestigator hired by his appellate attorneysdiscovered scientific evidence of Thompson’s <strong>in</strong>nocence that had been concealed for15 years by the New Orleans Parish District Attorney’s Office.Thompson was released and exonerated <strong>in</strong> 2003 after 18 years <strong>in</strong> prison, 14 of themisolated on death row. <strong>The</strong> state of Louisiana gave him $10 and a bus ticket upon hisrelease. He sued the District Attorney’s Office. A jury awarded him $14 million, one foreach year on death row. When Louisiana appealed, the case went to the U.S. SupremeJOHN THOMPSON1994 TO 2003 • MICHAEL EVANS 1977 TO 2003 • PAUL TERRY 1977 TO 2003 • LONNIE ERBY 1986 TO 2003 • STEVEN AVERY 1985 TO 2003 • CALVIN WILLIS 1982 TO 2003 • NICHOLAS YARRIS 1982 TO 2003 • CALVINL. SCOTT 1983 TO 2003 • WILEY FOUNTAIN 1986 TO 2003 • LEO WATERS 1982 TO 2003 • STEPHAN COWANS 1998 TO 2004 • ANTHONY POWELL 1992 TO 2004 • JOSIAH SUTTON 1999 TO 2004 • LAFONSO ROLLINS 1994TO 2004 • RYAN MATTHEWS 1999 TO 2004 • WILTON DEDGE 1982, 1984 TO 2004 • ARTHUR L. WHITFIELD 1982 TO 2004 • BARRY LAUGHMAN 1988 TO 2004 • CLARENCE HARRISON 1987 TO 2004 • DAVID A. JONES

10 THE INNOCENCE PROJECT IN PRINTCourt. This spr<strong>in</strong>g, Justice Clarence Thomas issued the majority 5-4 decision <strong>in</strong> Connickv. Thompson that the prosecutor’s office could not be held liable.<strong>The</strong> controversial and divided decision leaves Thompson with no choice but to geton with his life, which, <strong>in</strong>credibly, he already has. He is the founder and director of“Resurrection after Exoneration,” an organization that provides transitional hous<strong>in</strong>gto exonerees <strong>in</strong> the New Orleans area. Thompson’s fortitude notwithstand<strong>in</strong>g, his storyhas become a k<strong>in</strong>d of cautionary tale of unchecked prosecutorial power. If prosecutorscannot be held accountable <strong>in</strong> this case, when can they be held accountable?“BECAUSE THE ABSENCE OFTHE WITHHELD EVIDENCE MAYRESULT IN THE CONVICTION OFAN INNOCENT DEFENDANT,IT IS UNCONSCIONABLE NOTTO IMPOSE REASONABLECONTROLS IMPELLINGPROSECUTORS TO BRING THEINFORMATION TO LIGHT.”– Justice Ruth Bader G<strong>in</strong>sburgIn an op-ed for <strong>The</strong> New York Times, Thompson writes, “I don’t care about the money.I just want to know why the prosecutors who hid evidence, sent me to prison forsometh<strong>in</strong>g I didn’t do and nearly had me killed are not <strong>in</strong> jail themselves. <strong>The</strong>re wereno ethics charges aga<strong>in</strong>st them, no crim<strong>in</strong>al charges, no one was fired and now,accord<strong>in</strong>g to the Supreme Court, no one can be sued.”DELIBERATE INDIFFERENCE<strong>The</strong> prosecutorial misconduct <strong>in</strong> Thompson’s case was no anomaly. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to areport by the <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> of New Orleans, District Attorney Harry F. Connick’soffice withheld evidence favorable to the defense <strong>in</strong> at least n<strong>in</strong>e death row cases. Fourdeath row convictions were overturned because of the misconduct.In spite of this legacy, the Supreme Court ruled that the violation <strong>in</strong> the Thompsoncase was “a s<strong>in</strong>gle <strong>in</strong>cident,” and that no pattern of misconduct could be established.<strong>The</strong> majority op<strong>in</strong>ion acknowledges the four other overturned convictions but arguesthat they don’t count because different types of evidence were withheld <strong>in</strong> those cases.In her dissent, Justice G<strong>in</strong>sburg writes, “the conceded, long-concealed prosecutorialtransgressions were neither isolated nor atypical.” She cites ten items of evidence thatwere withheld from Thompson’s defense, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g police reports, audiotapes andblood evidence that would have seriously underm<strong>in</strong>ed Thompson’s conviction.Such violations have led to an <strong>in</strong>calculable number of wrongful convictions. Becauseof the often covert nature of prosecutorial misconduct, it is impossible to estimate howmany <strong>in</strong>nocent people have been affected. Furthermore, the vast majority of felonycases are resolved through plea barga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and never go to trial. Prosecutors may haveengaged <strong>in</strong> misconduct <strong>in</strong> those cases as well.In at least 63 of the wrongful convictions later overturned through DNA test<strong>in</strong>g,<strong>in</strong>nocent defendants alleged prosecutorial misconduct <strong>in</strong> their appeals or civil trials.Examples of misconduct <strong>in</strong>clude elict<strong>in</strong>g perjured testimony; destroy<strong>in</strong>g, conceal<strong>in</strong>gor fabricat<strong>in</strong>g evidence; mak<strong>in</strong>g improper and <strong>in</strong>flammatory statements and more.Recent studies of these and other cases have shown that prosecutors are rarely foundat fault, and even when they are, they are very rarely discipl<strong>in</strong>ed for it. A USA Today<strong>in</strong>vestigation found that only one federal prosecutor has been disbarred, even1995 TO 2004 • BRUCE D. GOODMAN 1986 TO 2004 • DONALD W. GOOD 1984 TO 2004 • DARRYL HUNT 1985 TO 2004 • BRANDON MOON 1988 TO 2005 • DONTE BOOKER 1987 TO 2005 • DENNIS BROWN 1985 TO2005 • PETER ROSE 1996 TO 2005 • MICHAEL A. WILLIAMS 1981 TO 2005 • HAROLD BUNTIN 1986 TO 2005 • ANTHONY WOODS 1984 TO 2005 • THOMAS DOSWELL 1986 TO 2005 • LUIS DIAZ 1980 TO 2005 • GEORGERODRIGUEZ 1987 TO 2005 • ROBERT CLARK 1982 TO 2005 • PHILLIP L. THURMAN 1985 TO 2005 • WILLIE DAVIDSON 1981 TO 2005 • CLARENCE ELKINS 1999 TO 2005 • JOHN KOGUT 1986 TO 2005 • ENTRE N. KARAGE

WHO WILL PROSECUTE THE PROSECUTORS?11temporarily, for misconduct <strong>in</strong> the past 12 years despite 201 documented cases ofviolated laws or ethics rules. <strong>The</strong> federal prosecutor <strong>in</strong> that one case was suspendedfrom practic<strong>in</strong>g law for just one year. A study conducted by the Northern California<strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> supports these f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs. In that study, over 700 Californiaprosecutors engaged <strong>in</strong> misconduct from 1997 to 2009 and only seven of themwere discipl<strong>in</strong>ed.In response to the misguided rul<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Connick v. Thompson, the <strong>Innocence</strong> Networksent a letter to Attorney General Eric Holder, the Presidents of the National DistrictAttorneys Association and the National Association of Attorneys General call<strong>in</strong>g forsolutions to the problem of prosecutorial misconduct. N<strong>in</strong>eteen wrongfully convictedvictims of prosecutorial misconduct signed the letter: “Now that the wrongfullyconvicted have virtually no mean<strong>in</strong>gful access to the courts to hold prosecutorsliable for their misdeeds, we demand to know what you <strong>in</strong>tend to do to put a checkon the otherwise unchecked and enormous power that prosecutors wield over thejustice system.”<strong>The</strong> 19 exoneree signatories <strong>in</strong>cluded five people who served time on death row.Kirk Bloodsworth, who spent two years on Maryland’s death row, remarked on theThompson decision: “It’s sad for America that we allow court officers to <strong>in</strong>flict themost harmful of all errors upon us with glib and cavalier <strong>in</strong>tent to only w<strong>in</strong>. Justice<strong>in</strong> that event always loses.” OTHER EXAMPLES OF PROSECUTORIAL MISCONDUCTTHOMAS GOLDSTEINLOS ANGELES DISTRICT ATTORNEY JOHN VAN DEKAMP DEVELOPED A CASE AGAINST GOLDSTEINBASED LARGELY ON THE INCENTIVIZED TESTIMONYOF A JAILHOUSE SNITCH. THE INFORMANTTESTIFIED THAT HE RECEIVED NO BENEFIT FORHIS TESTIMONY WHEN, IN FACT, HE HADNEGOTIATED WITH THE PROSECUTOR’S OFFICE FORA LIGHTER SENTENCE IN AN UNRELATED CRIME.THE U.S. SUPREME COURT STRUCK DOWNGOLDSTEIN’S ATTEMPT TO HOLD PROSECUTORS’LIABLE IN VAN DE KAMP V. GOLDSTEIN IN 2009.GOLDSTEIN’S CONVICTION WAS OVERTURNED IN2004 BECAUSE OF CONCERNS ABOUT THEINFORMANT’S CREDIBILITY.CURTIS McCARTYOKLAHOMA CITY DISTRICT ATTORNEY ROBERTMACY COMMITTED MULTIPLE ACTS OFMISCONDUCT IN THE McCARTY CASE, INCLUDINGWITHHOLDING KEY EVIDENCE FROM THE DEFENSE,DISPARAGING DEFENSE COUNSEL AND MAKINGINFLAMMATORY REMARKS. MACY SENT 73 PEOPLETO DEATH ROW DURING HIS 21 YEAR CAREER(INCLUDING McCARTY), MORE THAN ANY OTHERPROSECUTOR IN THE NATION. DNA TESTINGPROVED McCARTY’S INNOCENCE AND HE WASEXONERATED WITH THE HELP OF THE INNOCENCEPROJECT IN 2007. McCARTY SPENT 19 YEARS ONDEATH ROW AND 21 YEARS IN PRISON.NATHANIEL HATCHETTWHEN PRE-TRIAL DNA TESTING EXCLUDEDHATCHETT, PROSECUTORS REQUESTED THAT THEVICTIM'S HUSBAND'S GENETIC PROFILE BECOMPARED TO THE BIOLOGICAL EVIDENCE. BUTTHE HUSBAND WAS ALSO EXCLUDED, SUGGESTINGTHE PRESENCE OF AN UNKNOWN PERPETRATOR.PROSECUTORS DID NOT SHARE THIS INFORMATIONWITH DEFENSE ATTORNEYS. IN FACT, THEPROSECUTION REFERRED TO THE HUSBAND INCLOSING ARGUMENTS AS A POSSIBLECONTRIBUTOR OF THE EVIDENCE. DESPITE DNAEVIDENCE POINTING TO HIS INNOCENCE, HATCHETTWAS CONVICTED AND SPENT 10 YEARS IN PRISONBEFORE HIS EXONERATION IN 2008.1997 TO 2005 • KEITH E. TURNER 1983 TO 2005 • DENNIS HALSTEAD 1987 TO 2005 • JOHN RESTIVO 1987 TO 2005 • ALAN CROTZER 1981 TO 2006 • ARTHUR MUMPHREY 1986 TO 2006 • DREW WHITLEY 1989 TO 2006 •DOUGLAS WARNEY 1997 TO 2006 • ORLANDO BOQUETE 1983 TO 2006 • WILLIE JACKSON 1989 TO 2006 • LARRY PETERSON 1989 TO 2006 • ALAN NEWTON 1985 TO 2006 • JAMES TILLMAN 1989 TO 2006 • JOHNNYBRISCOE 1983 TO 2006 • JEFFREY DESKOVIC 1990 TO 2006 • ALLEN COCO 1997 TO 2006 • JAMES OCHOA 2005 TO 2006 • SCOTT FAPPIANO 1985 TO 2006 • MARLON PENDLETON 1996 TO 2006 • BILLY J. SMITH 1987

12STRENGTHIN NUMBERS<strong>The</strong> annual <strong>Innocence</strong> Network Conference is the largest gather<strong>in</strong>gof exonerated people anywhere <strong>in</strong> the world. This year was thebiggest ever.Stand<strong>in</strong>g together, the men and women on stage represented hundreds of yearsof wrongful imprisonment. <strong>The</strong>y were Americans, Mexicans, British, Japanese andCanadians. <strong>The</strong>y were grandfathers, mothers, small bus<strong>in</strong>ess owners, students, activistsand newlyweds. Some had been exonerated 10 years ago or more, others had beenout less than a month. <strong>The</strong>y were tak<strong>in</strong>g their lives back.Before 2000, only 66 people had been exonerated through DNA test<strong>in</strong>g and they werescattered throughout the country. Today, over 270 <strong>in</strong>nocent people have been clearedthrough DNA test<strong>in</strong>g and hundreds more have been exonerated through other means.Each year, they meet to socialize and strategize at the <strong>Innocence</strong> Network Conference.EXONEREES ON STAGE AT THE “LET FREEDOM SING”CONCERT ON THE LAST NIGHT OF THE INNOCENCE NETWORKCONFERENCE IN CINCINNATI.<strong>The</strong> <strong>Innocence</strong> Network is an affiliation of organizations that provides pro bono legaland <strong>in</strong>vestigative services to prisoners with claims of <strong>in</strong>nocence and works to improveTO 2006 • BILLY W. MILLER 1984 TO 2006 • EUGENE HENTON 1984 TO 2006 • GREGORY WALLIS 1989 TO 2007 • LARRY FULLER 1981 TO 2007 • TRAVIS HAYES 1998 TO 2007 • WILLIE O. WILLIAMS 1985 TO 2007 • ROYBROWN 1992 TO 2007 • CODY DAVIS 2006 TO 2007 • JAMES WALLER 1983 TO 2007 • ANDREW GOSSETT 2000 TO 2007 • ANTONIO BEAVER 1997 TO 2007 • ANTHONY CAPOZZI 1987 TO 2007 • JERRY MILLER 1982 TO2007 • CURTIS MCCARTY 1986, 1989 TO 2007 • JAMES C. GILES 1983 TO 2007 • BYRON HALSEY 1988 TO 2007 • DWAYNE A. DAIL 1989 TO 2007 • LARRY BOSTIC 1989 TO 2007 • MARCUS LYONS 1988 TO 2007 • CHAD

STRENGTH IN NUMBERS13the crim<strong>in</strong>al justice system. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> is a found<strong>in</strong>g member of theNetwork, which now <strong>in</strong>cludes 55 projects from the U.S. and 9 <strong>in</strong> other countries.Attorneys and staff members from the projects also attend the conference.Hosted by the Ohio <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> at the Freedom Center <strong>in</strong> C<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>nati, theApril <strong>2011</strong> conference was the largest gather<strong>in</strong>g of exonerees ever. Part family reunion,part professional network<strong>in</strong>g opportunity, the conference gave exonerees the chanceto reunite and work toward common goals – fight<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>justice and eas<strong>in</strong>g the transitionfor the newly released. In a welcom<strong>in</strong>g ceremony, each exonerated person cameforward as their name and current occupation was read. Here are a few of their stories:JAMES D. WALLER: Fundrais<strong>in</strong>g for Exoneree Brothers of Texas;Bail bondsmanExonerated from Dallas, Texas, <strong>in</strong> 2007, James Waller has attended the conferenceevery year s<strong>in</strong>ce his exoneration. Those four conferences have brought him to SanJose, California; Houston, Texas; Atlanta, Georgia; and now to C<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>nati. Impeccablydressed <strong>in</strong> a tan suit at 6’4”, he’s ever aware of the impact his presence can haveat strategic times – at a legislative hear<strong>in</strong>g for crim<strong>in</strong>al justice reform, for example,or at the exoneration of the person most recently proven <strong>in</strong>nocent <strong>in</strong> Texas. His driveto be a presence <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>nocence movement br<strong>in</strong>gs him back to the conference yearafter year.Waller says, “At the Introduction of the Exonerees, you see all these people come upknow<strong>in</strong>g that they’ve been locked up for a long time. So many years, and so many familymembers lost dur<strong>in</strong>g that time. To see that they still want to get out and work after be<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>carcerated for so long – you see men who are 50 years old and don’t have any socialsecurity because they were locked up for 25 or 30 years – and then for them to say thatthey just want to get out and do someth<strong>in</strong>g to help, that takes a lot of courage.”Waller and four other Texas exonerees have started the “Exoneree Brothers of Texas,”to provide assistance to the newly released exonerees. <strong>The</strong> group is fil<strong>in</strong>g for nonprofitstatus and hop<strong>in</strong>g to provide transitional hous<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Dallas for Texas exonerees andat-risk youth.JAMES WALLERCORNELIUS DUPREE: Attend<strong>in</strong>g Houston Community College;Advocate for eyewitness reform; Intern for Senator Rodney EllisOne would never guess from all of his activities that Cornelius Dupree has only beenexonerated for a few months and has been out of prison for less than a year. Released<strong>in</strong> July 2010 and exonerated <strong>in</strong> March <strong>2011</strong>, he endured 30 years of wrongfulimprisonment. He attended the conference for the first time this year with his wife,Selma Perk<strong>in</strong>s Dupree. After two decades of courtship beh<strong>in</strong>d bars, the two weremarried the day after his release.HEINS 1996 TO 2007 • JOHN J. WHITE 1980 TO 2007 • RICKEY JOHNSON 1983 TO 2008 • RONALD G. TAYLOR 1995 TO 2008 • KENNEDY BREWER 1995 TO 2008 • CHARLES CHATMAN 1981 TO 2008 • NATHANIEL HATCHETT1998 TO 2008 • DEAN CAGE 1996 TO 2008 • THOMAS MCGOWAN 1985, 1986 TO 2008 • ROBERT MCCLENDON 1991 TO 2008 • MICHAEL BLAIR 1994 TO 2008 • PATRICK WALLER 1992 TO 2008 • STEVEN PHILLIPS 1982,1983 TO 2008 • ARTHUR JOHNSON 1993 TO 2008 • JOSEPH WHITE 1989 TO 2008 • WILLIAM DILLON 1981 TO 2008 • STEVEN BARNES 1989 TO 2009 • RICARDO RACHELL 2003 TO 2009 • JAMES DEAN 1990 TO 2009 •

14<strong>The</strong> trip to C<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>nati also marked Dupree’s first time on an airplane. “Everyth<strong>in</strong>g ismy first. Go<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to prison at such a young age, I never had the opportunity to live asan adult. You miss out on so much.”“EACH ONE CAN IDENTIFYWITH YOUR HURT AND SORROWSAND PAIN.”– Cornelius DupreeLike Waller, his favorite moment of the conference was the Introduction to theExonerees ceremony. “To see everyone come together on the same stage <strong>in</strong> unity – thatmeant a lot to me. That was very unique to be <strong>in</strong> one spot with exonerees from all overthe globe who have experienced the same th<strong>in</strong>g. You all can communicate on the samelevel. Each one can identify with your hurt and sorrows and pa<strong>in</strong>.”Be<strong>in</strong>g from Texas, Dupree has a stronger local support network than many others. Infact, a dozen or more Texas exonerees came out to support him at the Dallas Countycourthouse when he was pronounced <strong>in</strong>nocent. Several of them had even served timetogether. Dupree hopes to do the same for those who follow <strong>in</strong> his footsteps. “I lookforward to be<strong>in</strong>g very active and supportive <strong>in</strong> the years to come,” he says.TOSHIKAZU SUGAYA: Japan’s First DNA Exoneration<strong>The</strong> tsunami that devastated Japan struck less than a month before the Aprilconference, but Toshikazu Sugaya made the long journey to Ohio nevertheless. Sugayahas become an outspoken advocate for crim<strong>in</strong>al justice reform <strong>in</strong> Japan s<strong>in</strong>ce his DNAexoneration <strong>in</strong> 2010.DARRYL BURTON EXONERATED FROM ST. LOUIS, MISSOURI(LEFT), AND BRITISH EXONEREE, GERRY CONLON (RIGHT),READ A POEM FROM “ILLUSTRATED TRUTH: EXPRESSIONS OFWRONGFUL CONVICTION” EXHIBIT SHOWCASED DURING THEINNOCENCE NETWORK CONFERENCE.Based almost entirely on his false confession, Sugaya was convicted of the murder of a4-year-old girl <strong>in</strong> 1990. A 45-year-old school bus driver at the time, Sugaya was a seniorcitizen by the time he was released. Both of his parents had passed away; his father diedjust two weeks after Sugaya’s arrest.Speak<strong>in</strong>g through a translator, Sugaya expla<strong>in</strong>ed that he had been coerced <strong>in</strong>toconfess<strong>in</strong>g after 13 hours of <strong>in</strong>terrogation. “In Japan, <strong>in</strong>terrogations are not recorded.KATHY GONZALEZ 1990 TO 2009 • DEBRA SHELDEN 1989 TO 2009 • ADA J. TAYLOR 1990 TO 2009 • THOMAS WINSLOW 1990 TO 2009 • JOSEPH FEARS JR. 1984 TO 2009 • MIGUEL ROMAN 1990 TO 2009 • VICTORBURNETTE 1979 TO 2009 • TIMOTHY COLE 1986 TO 2009 • JOHNNIE LINDSEY 1983, 1985 TO 2009 • CHAUNTE OTT 1996 TO 2009 • LAWRENCE MCKINNEY 1978 TO 2009 • ROBERT L. STINSON 1985 TO 2009 • KENNETHIRELAND 1988 TO 2009 • JOSEPH ABBITT 1995 TO 2009 • JAMES L. WOODARD 1981 TO 2009 • JERRY L. EVANS 1987 TO 2009 • MICHAEL MARSHALL 2008 TO 2009 • JAMES BAIN 1974 TO 2009 • DONALD E. GATES

STRENGTH IN NUMBERS15I want to see that change made <strong>in</strong> Japan and all over the world. That’s why I’m here.”Electronically record<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terrogations from the read<strong>in</strong>g of the Miranda rights onwardis the best reform available to prevent false confessions from becom<strong>in</strong>g wrongfulconvictions. In the U.S., only 18 states require <strong>in</strong>terrogations to be recorded. (Formore about false confessions, see “In <strong>The</strong>ir Own Words” on p. 16.) In Japan, suspectscan be <strong>in</strong>terrogated for up to 23 days, and <strong>in</strong>terrogations may <strong>in</strong>clude physical violenceand sleep deprivation.As one of the only exonerees <strong>in</strong> his home country, Sugaya enjoyed the opportunityto <strong>in</strong>teract with people from other countries who know what he’s go<strong>in</strong>g through.“Everyone is on the same page,” he says. “I feel like I made some friends. I would liketo come aga<strong>in</strong>.”TRENA BOZELLA: Wife of Exoneree Dewey BozellaFamily members of the exonerated attended the conference as well, not only toaccompany their husbands, brothers and daughters, but also to connect with otherswho share their experience. As Trena Bozella says, “Anyone who has stuck by an<strong>in</strong>nocent person <strong>in</strong> prison has a story to tell.”Trena and Dewey Bozella had been married 14 years by the time of his release andexoneration for a Poughkeepsie, New York, murder that he didn’t commit. Thoseyears of deal<strong>in</strong>g with his wrongful imprisonment were hard, she remembers, but lifes<strong>in</strong>ce his exoneration <strong>in</strong> 2009 has presented its own set of challenges. “<strong>The</strong> sleeplessnights, the attitudes, the mood sw<strong>in</strong>gs. I had no tools to deal with it.” She spoke aboutthese challenges on a special panel at the conference titled “Women on the Outside.”<strong>The</strong> three panelists spoke about the costs, both f<strong>in</strong>ancial and emotional, of wrongfulconviction from a family member’s perspective.Fellow family members of the exonerated can help prepare each other for a newlyexonerated relatives’ homecom<strong>in</strong>g. Most exonerees, if they have surviv<strong>in</strong>g family, goto live with them immediately upon release. By speak<strong>in</strong>g out at the conference, Bozellahopes that she reached others who might learn from her experience: “We go throughyears of visit<strong>in</strong>g them, br<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g them packages, we do this and that. We always look likethe strong ones. Sometimes I thought I was los<strong>in</strong>g myself to be there for him.”TRENA AND DEWEY BOZELLADewey Bozella has s<strong>in</strong>ce become a box<strong>in</strong>g tra<strong>in</strong>er and a counselor for formerly<strong>in</strong>carcerated youth. Trena Bozella says, “After all that Dewey has gone through fight<strong>in</strong>gfor his freedom, he’s f<strong>in</strong>ally found a family,” she says, referr<strong>in</strong>g to the bond betweenthe exonerated men and women. “It’s brotherhood and sisterhood with the men andwomen who have been wrongfully convicted.” 1982 TO 2009 • FREDDIE PEACOCK 1976 TO 2010 • TED BRADFORD 1996 TO 2010 • ANTHONY CARAVELLA 1986 TO 2010 • FRANK STERLING 1992 TO 2010 • RAYMOND TOWLER 1981 TO 2010 • CURTIS J. MOORE 1978TO 2010 • PATRICK BROWN 2002 TO 2010 • DOUGLAS PACYON 1985 TO 2010 • LARRY DAVIS 1993 TO 2010 • ALAN NORTHROP 1993 TO 2010 • ANTHONY JOHNSON 1986 TO 2010 • WILLIAM AVERY 2004 TO 2010 •MAURICE PATTERSON 2003 TO 2010 • MICHAEL A. GREEN 1983 TO 2010 • JOHN WATKINS 2004 TO 2010 • PHILLIP BIVENS 1980 TO 2010 • BOBBY RAY DIXON 1980 TO 2010 • LARRY RUFFIN 1980 TO 2010 • CORNELIUS

16IN THEIROWN WORDSQ & A WITH RICHARD LEO, ASSOCIATE PROFESSOROF LAW AT THE UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO ANDFALSE CONFESSION EXPERTDNA exonerations have proven what many f<strong>in</strong>d impossible to believe – people confessto crimes they didn’t commit. In fact, false confessions and admissions contribute toabout 25% of wrongful convictions <strong>in</strong> DNA exoneration cases. In Richard Leo’s book,“Police Interrogation and American Justice,” Leo exam<strong>in</strong>es how <strong>in</strong>terrogations canelicit confessions from <strong>in</strong>nocent people. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> In Pr<strong>in</strong>t asked Leo to helpexpla<strong>in</strong> what happens <strong>in</strong>side the <strong>in</strong>terrogation room, how false confessions lead towrongful convictions and how they can be prevented.<strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> In Pr<strong>in</strong>t: What happens dur<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>terrogation process thatcould cause a person to falsely confess?RICHARD LEO IN HIS OFFICE AT THE UNIVERSITY OFSAN FRANCISCO.Richard Leo: Interrogations are a two-step process – sticks and carrots. <strong>The</strong> first stepis beat<strong>in</strong>g the suspect down psychologically. <strong>The</strong>n, after you move the person to aperception that there is no way out, the second step is to <strong>in</strong>duce them to th<strong>in</strong>k thatthey’re better off confess<strong>in</strong>g. <strong>The</strong> first step <strong>in</strong>volves isolat<strong>in</strong>g the suspect, accus<strong>in</strong>g themand cutt<strong>in</strong>g off their denials. Interrogators are tra<strong>in</strong>ed to dom<strong>in</strong>ate the <strong>in</strong>teraction andnot let the suspect verbalize the words, “I did not do it. I am <strong>in</strong>nocent.” At the heart ofthis first step is what researchers call “the evidence ploy.” Most people <strong>in</strong> America don’tknow that police can lie about the existence of evidence, to say “We’ve got yourf<strong>in</strong>gerpr<strong>in</strong>ts.” I cannot th<strong>in</strong>k of a s<strong>in</strong>gle false confession case that didn’t <strong>in</strong>volve liesabout evidence.IP: Do Miranda warn<strong>in</strong>gs help prevent false confessions?RL: Miranda Warn<strong>in</strong>gs were designed to protect someone’s free choice to participate<strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>terrogation. “You have the right to rema<strong>in</strong> silent. You have the right to anattorney.” When people hear that they don’t th<strong>in</strong>k, “I can shut down the <strong>in</strong>terrogation.”<strong>The</strong>y just th<strong>in</strong>k they’re be<strong>in</strong>g educated about their rights more broadly. If you’re of aDUPREE 1980 TO <strong>2011</strong> • DERRICK WILLIAMS 1993 TO <strong>2011</strong> • CALVIN W. CUNNINGHAM 1981 TO <strong>2011</strong>

IN THEIR OWN WORDS17certa<strong>in</strong> education level or have lawyers <strong>in</strong> the family, you might know that police cantrap you. But most people don’t know that. <strong>The</strong> impulse to talk when a police officer isaccus<strong>in</strong>g you is strong. We want to <strong>in</strong>st<strong>in</strong>ctively defend ourselves aga<strong>in</strong>st false accusations.You could say “I would like to have a lawyer.” In theory, that should end the <strong>in</strong>terrogation.Very few suspects actually say that, and usually when they have said that <strong>in</strong> the<strong>in</strong>nocence cases, it was ignored.IP: Can you speak about how young people are especially vulnerable?RL: <strong>The</strong>re’s great research from developmental psychology about why juveniles aremore vulnerable to false confessions: they’re less mature, they’re more impulsive, theyare more gullible and trustworthy, and they don’t th<strong>in</strong>k about long-term consequences.<strong>The</strong>se are the same reasons why people with low IQs are vulnerable. But falseconfessors are not limited to these categories.IP: Can hav<strong>in</strong>g the parents present dur<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>terrogation be a protection?RL: I’ve always been skeptical about the idea of gett<strong>in</strong>g a guardian or parent <strong>in</strong> theroom. Because the police make up evidence, and they tell the parents, “We have peoplesay<strong>in</strong>g he did this.” <strong>The</strong>n the parents are like, “Joe, stop ly<strong>in</strong>g. You need to tell theofficer the truth.” So the parents become agents, oftentimes, of the police. Most parentsjust aren’t street smart.IP: Can you expla<strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>vestigators’ “presumption of guilt”?RL: A police <strong>in</strong>terrogator’s goal is to build a case, not to separate out whether thesuspect is likely <strong>in</strong>nocent or likely guilty. <strong>The</strong>re’s no hypothesis test<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>terrogations.If we start th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g about more thorough ways to analyze whether the suspect is likelyguilty or not, and maybe gett<strong>in</strong>g more evidence before we subject them to that<strong>in</strong>terrogation, maybe police can prevent more false confessions.“INTERROGATORS ARE TRAINEDTO DOMINATE THE INTERACTIONAND NOT LET THE SUSPECTVERBALIZE THE WORDS,‘I DID NOT DO IT.’”– Richard LeoIP: What other reforms do you recommend?RL: Electronically record<strong>in</strong>g the entire <strong>in</strong>terrogation is the most important reform.Non-public details (that are not publicly known by anyone other than the trueperpetrator and the police) can be <strong>in</strong>tentionally or un<strong>in</strong>tentionally imputed to thesuspect. <strong>The</strong>y make the confession seem persuasive. Record<strong>in</strong>g captures thecontam<strong>in</strong>ation process from start to f<strong>in</strong>ish. If a case were to go to trial, the defenseattorney can show how the details never were known by the person be<strong>in</strong>g accused,and how they were fed at every step of the way.IP: Are <strong>in</strong>terrogations ever good and necessary?RL: You need confessions to solve crimes, especially murder crimes, and as long asconfessions are done fairly and legally, we’re absolutely <strong>in</strong> favor of the <strong>in</strong>terrogationsthat produce them. We don’t want to underm<strong>in</strong>e the ability of police, most of whomare good and decent people who follow the rules, to get these confessions. As long asyou do th<strong>in</strong>gs fairly and properly, it shouldn’t endanger the <strong>in</strong>nocent.

18EXONERATIONNATIONS<strong>in</strong>ce January <strong>2011</strong>, three more <strong>in</strong>nocent people have been exoneratedthrough DNA test<strong>in</strong>g. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> congratulates these<strong>in</strong>spir<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividuals, as well as our colleagues who fought to help provetheir <strong>in</strong>nocence.DERRICK WILLIAMS (CENTER), HOLDS HIS GRANDSON, OMARJR., WHILE SURROUNDED BY FAMILY MEMBERS ON HISEXONERATION DAY.Of the 42 people exonerated through DNA test<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Texas, none served more timethan CORNELIUS DUPREE who was wrongfully imprisoned for 30 years before hisrelease <strong>in</strong> January <strong>2011</strong>. At the age of 19, he was misidentified and convicted of anarmed rape and robbery. <strong>The</strong> perpetrators, who have never been identified, accosteda young woman and her male friend <strong>in</strong> a Dallas park<strong>in</strong>g lot. <strong>The</strong>y robbed both victimsand forced the male victim to drive. Later, they forced the male victim out of the carand raped the young woman <strong>in</strong> a nearby park.

EXONERATION NATION19Dupree and his friend, Anthony Mass<strong>in</strong>gill (who also claims <strong>in</strong>nocence), becamesuspects after they were stopped and frisked by police. <strong>The</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g day, the femalevictim selected both Dupree and Mass<strong>in</strong>gill from a photo array. <strong>The</strong> male victim didn’tmake an identification. DNA test<strong>in</strong>g was not available at the time of the trial, but postconvictionDNA test<strong>in</strong>g secured by the <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> produced two male profiles,neither of which matched Dupree or his co-defendant. Dupree was officially exoneratedon March 3. Mass<strong>in</strong>gill is still fight<strong>in</strong>g to prove his <strong>in</strong>nocence.Based on a suggestive identification procedure, a Florida rape victim selectedDERRICK WILLIAMS as the man who drove her to a secluded orange grove and rapedher <strong>in</strong> the backseat of her car <strong>in</strong> the summer of 1992. After view<strong>in</strong>g a photo array <strong>in</strong>which Williams’ picture appeared twice, she said that she was about 80% sure that hewas the perpetrator. By the time she viewed him aga<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> a live l<strong>in</strong>eup, she was 100%sure. At trial, Williams testified that he was attend<strong>in</strong>g a family barbecue at the time ofthe rape, an alibi corroborated by six witnesses. Furthermore, Williams did not matchthe description of the perpetrator as be<strong>in</strong>g about 5’6” with a scar on his gut; he is 5’11”and has a scar on his back. Williams was wrongfully convicted <strong>in</strong> 1993 and sentenced tolife <strong>in</strong> prison.With the help of the Florida <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong>, Williams received post-convictionDNA test<strong>in</strong>g of sweat and sk<strong>in</strong> cells from a T-shirt worn by the attacker. Other evidence,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g a rape kit and other cloth<strong>in</strong>g, had been destroyed after a water leak at theevidence warehouse facility led to extensive damage. DNA test results proved thatWilliams did not wear the T-shirt and therefore, could not have been the perpetrator.A judge also ruled that the destruction of the other evidence <strong>in</strong> Williams’ case violatedhis due process rights. Williams was released and exonerated on April 4. He had spent18 years <strong>in</strong> prison.When CALVIN WAYNE CUNNINGHAM’s neighbor across the hall was raped at 4 a.m.one morn<strong>in</strong>g, she identified Cunn<strong>in</strong>gham as the perpetrator. In 1981, Cunn<strong>in</strong>gham wasconvicted of the crime. In 1982, before DNA test<strong>in</strong>g had ever been used <strong>in</strong> a crim<strong>in</strong>alcase, he wrote to a judge request<strong>in</strong>g that his biological sample be compared with theevidence at the crime scene. He spent seven years <strong>in</strong> prison before be<strong>in</strong>g released onparole and made to register as a sex offender.CORNELIUS DUPREECunn<strong>in</strong>gham returned to prison for an unrelated, non-violent offense. In themeantime, Virg<strong>in</strong>ia Governor Mark Warner ordered a review of hundreds of closedcases after DNA exonerations raised questions about the state crim<strong>in</strong>al justice system.Through this review, Cunn<strong>in</strong>gham’s evidence was f<strong>in</strong>ally tested, and he was proven<strong>in</strong>nocent of the crime. <strong>The</strong> Mid-Atlantic <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> represented him <strong>in</strong> hisexoneration on April 12. Cunn<strong>in</strong>gham is still serv<strong>in</strong>g a four-year sentence on unrelatedcharges and expects to be released <strong>in</strong> November 2012. 3,494YEARS OF WRONGFUL INCARCERATION ENDURED BY ALL271 EXONEREES

20IP NEWSTEXAS FORENSIC SCIENCE COMMISSION ISSUES RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ARSON CASESSeven years after Texas executed Cameron Todd Will<strong>in</strong>gham based on outdated andunscientific arson evidence, the Texas Forensic Science Commission released an 893-page report recommend<strong>in</strong>g more education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g for fire <strong>in</strong>vestigators andimplement<strong>in</strong>g procedures to review old cases.<strong>The</strong> report was the long-awaited response to the <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong>’s 2006 allegation <strong>in</strong>two cases – Cameron Todd Will<strong>in</strong>gham and Ernest Willis – argu<strong>in</strong>g that both had beenwrongfully convicted based on the same flawed arson evidence. Though Will<strong>in</strong>ghamwas executed, Willis was exonerated. After years of politically motivated delays andupheavals, the TFSC issued the report with 16 recommendations this April. While theTFSC stopped short of say<strong>in</strong>g that arson <strong>in</strong>vestigators were negligent <strong>in</strong> Will<strong>in</strong>gham’scase, it did concede that the arson evidence used to convict him was outdated. Anop<strong>in</strong>ion is pend<strong>in</strong>g from the Texas Attorney General about whether the commissionmay report on the alleged negligence of the arson <strong>in</strong>vestigators.HANK SKINNERILLINOIS ABOLISHES THE DEATH PENALTYCit<strong>in</strong>g the risk of wrongful execution and other fail<strong>in</strong>gs, Ill<strong>in</strong>ois Governor Pat Qu<strong>in</strong>nsigned a bill abolish<strong>in</strong>g the state’s death penalty <strong>in</strong> March. Gov. Qu<strong>in</strong>n also commutedthe sentences of all 15 <strong>in</strong>mates rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g on Ill<strong>in</strong>ois’ death row. From Gov. Qu<strong>in</strong>n’sofficial statement: “S<strong>in</strong>ce 1977, Ill<strong>in</strong>ois has seen 20 people exonerated from deathrow….That is a record that should trouble us all. To say that this is unacceptable doesnot even beg<strong>in</strong> to express the profound regret and shame we, as a society, must bearfor these failures of justice.”Former Governor George Ryan lead the way by pass<strong>in</strong>g a moratorium on executions <strong>in</strong>2000 <strong>in</strong> response to a grow<strong>in</strong>g concern about the possibility of execut<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>nocentperson. Five of the 17 people who have been exonerated by DNA test<strong>in</strong>g after serv<strong>in</strong>gtime on death row were Ill<strong>in</strong>ois’ cases. <strong>The</strong> state, which once had one of the largerdeath rows <strong>in</strong> the country, has not executed anyone s<strong>in</strong>ce 1999. S<strong>in</strong>ce the re<strong>in</strong>statementof the death penalty <strong>in</strong> 1977, sixteen states and the District of Columbia have haltedexecutions.SUPREME COURT APPROVES PRISONER’S CLAIM FOR DNA TESTINGTexas Death Row Inmate Hank Sk<strong>in</strong>ner was just hours away from execution when theU.S. Supreme Court stayed his execution and granted Sk<strong>in</strong>ner’s request to file a civil

IP NEWS21rights claim <strong>in</strong> federal court for post-conviction DNA test<strong>in</strong>g. <strong>The</strong> March rul<strong>in</strong>g maybenefit other prisoners whose requests for test<strong>in</strong>g have been unfairly denied by statecourts. Sk<strong>in</strong>ner had been seek<strong>in</strong>g DNA test<strong>in</strong>g for 10 years <strong>in</strong> the murder of his live-<strong>in</strong>girlfriend and her two sons. Among the evidence Sk<strong>in</strong>ner is seek<strong>in</strong>g to test are knivesfrom the crime scene, hairs from the victim’s hand and a w<strong>in</strong>dbreaker possibly worn bythe perpetrator. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong>, which has assisted Sk<strong>in</strong>ner’s attorneys, arguesthat these items could provide proof of his guilt or <strong>in</strong>nocence. Seventeen people havebeen proven <strong>in</strong>nocent and exonerated by DNA test<strong>in</strong>g after serv<strong>in</strong>g time on death row.IP’S FIFTH ANNUAL CELEBRATION OF FREEDOM AND JUSTICE A SUCCESSHundreds of <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> supporters and exonerees gathered to celebrate andraise over $950,000 for the organization at the <strong>2011</strong> benefit dur<strong>in</strong>g which Betty AnneWaters, Governor Jon S. Corz<strong>in</strong>e and the law firm of Schulte Roth & Zabel werehonored. Waters’ story of determ<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> fight<strong>in</strong>g for her brother’s exonerationthrough DNA test<strong>in</strong>g became a major motion picture <strong>in</strong> 2010 – “Conviction” starr<strong>in</strong>gHilary Swank and Sam Rockwell. Governor Jon S. Corz<strong>in</strong>e led New Jersey <strong>in</strong> crim<strong>in</strong>aljustice reform, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g abolish<strong>in</strong>g the death penalty. <strong>The</strong> law firm of Schulte Roth& Zabel has provided extensive pro bono work and ongo<strong>in</strong>g support for the <strong>Innocence</strong><strong>Project</strong>. <strong>The</strong> gala, held at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel on May 4, <strong>in</strong>cluded musicalenterta<strong>in</strong>ment from jazz pianist Jonathan Batiste and exoneree musicians WilliamDillon, Antione Day and Raymond Towler.DNA EVIDENCE CLEARS NINE IN CHICAGONew DNA test results prove that four men were convicted of a 1994 rape and murderthey didn’t commit. <strong>The</strong> DNA results l<strong>in</strong>k a convicted murderer to the crime, and thefour men are seek<strong>in</strong>g to be released from prison based on the new evidence. <strong>The</strong> caseis nearly identical to another <strong>in</strong> the Chicago area, <strong>in</strong> which five men convicted of a1991 murder are seek<strong>in</strong>g to overturn their convictions based on DNA evidence that aconvicted rapist committed the crime.BETTY ANNE WATERS WITH EXONEREE ANTIONE DAY AT THE<strong>2011</strong> INNOCENCE PROJECT BENEFIT.In both cases, the defendants were teenagers when they were arrested, as young as14, and the pr<strong>in</strong>cipal evidence used aga<strong>in</strong>st them was their own confessions. (To readabout why young people are more susceptible to false confessions, see “In <strong>The</strong>ir OwnWords” on page 16.) Also <strong>in</strong> both cases, the defendants were convicted <strong>in</strong> spite ofprelim<strong>in</strong>ary DNA tests that excluded all n<strong>in</strong>e of them. However, there was noconnection to another possible suspect as there is now. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> iswork<strong>in</strong>g with the Center on Wrongful Convictions of Youth (at Northwestern LawSchool), the Exoneration <strong>Project</strong> (at the University of Chicago Law School) and privateattorneys to overturn all n<strong>in</strong>e convictions and exonerate the men.

22INNOCENCEBY THE NUMBERSINEFFECTIVE DEFENSEIn the W<strong>in</strong>ter 2010 issue of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> In Pr<strong>in</strong>t, we provided statistics aboutprosecutorial misconduct. <strong>The</strong> other side of that issue, and another major contributorto wrongful convictions, is <strong>in</strong>effective defense. While cases of outright <strong>in</strong>competencedo exist, and should be addressed, defense attorney’s fail<strong>in</strong>gs are better understood bywhat they did not do. Negligent attorneys, struggl<strong>in</strong>g with a massive caseload and a lackof resources, do not meet their constitutional obligation to advocate for their clients.<strong>The</strong> data below offers only a glimpse of the problem and <strong>in</strong>dicates only those caseswhere <strong>in</strong>formation was available.Number of the 271 DNA exonerees to allege <strong>in</strong>effective assistance of counsel <strong>in</strong> theirpost-conviction appeals 62Number of those 62 <strong>in</strong> which courts found error, whether harmful or harmless 10Number of those 62 <strong>in</strong> which courts found “harmful error” that lead to a reversalof the conviction 7Number of the 271 DNA exonerees who paid for their own lawyer at their orig<strong>in</strong>altrials (result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the wrongful conviction) 65 1Number of the 271 DNA exonerees who were represented by a public defenderor court-appo<strong>in</strong>ted counsel at their orig<strong>in</strong>al trials 163 1Average hourly rate of lawyers <strong>in</strong> private practice $ 178 - $ 265 2Approximate hourly rate of court-appo<strong>in</strong>ted attorneys <strong>in</strong> non-capital felonycases $ 50 - $ 65 2Percent <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> crim<strong>in</strong>al caseloads from state public defender programs from1999 to 2007 20% 3Percent <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> number of public defenders employed <strong>in</strong> state programs for thesame period 4% 31 Based on 228 cases where <strong>in</strong>formation was known.2 <strong>The</strong> Constitution <strong>Project</strong>, “Justice Denied: America’s Cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g Neglect of Our Constitutional Rightto Counsel,” (2009).3 Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report, “Defense Counsel <strong>in</strong> Crim<strong>in</strong>al Cases,” (2000).

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong> was founded <strong>in</strong> 1992 by Barry C. Scheck and Peter J. Neufeld at theBenjam<strong>in</strong> N. Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University to assist prisoners who could beproven <strong>in</strong>nocent through DNA test<strong>in</strong>g. To date, 271 people <strong>in</strong> the United States have beenexonerated by DNA test<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g 17 who served time on death row. <strong>The</strong>se peopleserved an average of 13 years <strong>in</strong> prison before exoneration and release. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Innocence</strong><strong>Project</strong>’s full-time staff attorneys and Cardozo cl<strong>in</strong>ic students provided directrepresentation or critical assistance <strong>in</strong> most of these cases. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong>’sgroundbreak<strong>in</strong>g use of DNA technology to free <strong>in</strong>nocent people has provided irrefutableproof that wrongful convictions are not isolated or rare events but <strong>in</strong>stead arise fromsystemic defects. Now an <strong>in</strong>dependent nonprofit organization closely affiliated withCardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University, the <strong>Innocence</strong> <strong>Project</strong>’s mission is noth<strong>in</strong>gless than to free the stagger<strong>in</strong>g numbers of <strong>in</strong>nocent people who rema<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>carcerated andto br<strong>in</strong>g substantive reform to the system responsible for their unjust imprisonment.OUR STAFFOlga Akselrod: Staff Attorney, Angela Amel: Director of Social Work and Associate Director of Operations/LitigationDepartment, Anna Arons: Paralegal, Elena Aviles: Document Manager, Rebecca Brown: Senior Policy Advocate forState Affairs, Paul Cates: Director of Communications, Sarah Chu: Forensic Policy Advocate, Scott Clugstone: Directorof F<strong>in</strong>ance and Adm<strong>in</strong>istration, Craig Cooley: Staff Attorney, Ariana Costakes: Receptionist, Valencia Craig: CaseManagement Database Adm<strong>in</strong>istrator, Hensleigh Crowell: Paralegal, Jamie Cunn<strong>in</strong>gham: Policy Associate, Huy Dao:Case Director, Madel<strong>in</strong>e deLone: Executive Director, Ana Marie Diaz: Case Assistant, Akiva Freidl<strong>in</strong>: Associate Directorfor Institutional Giv<strong>in</strong>g, Nicholas Goodness: Case Analyst, Edw<strong>in</strong> Grimsley: Case Analyst, Caitl<strong>in</strong> Hanvey:Development Assistant, Nicole Leigh Harris: Policy Analyst, Barbara Hertel: F<strong>in</strong>ance Associate, William D. Ingram:Case Assistant, Jeffrey Johnson: Office Manager, Matt Kelley: Onl<strong>in</strong>e Communications Manager, Jason Kreag: StaffAttorney, Jason Lantz: Assistant Director, Information and Communications Technology, Audrey Levit<strong>in</strong>: Director ofDevelopment, David Loftis: Manag<strong>in</strong>g Attorney, Laura Ma: Assistant Director, Donor Services, Vanessa Meterko:Research Assistant, Alba Morales: Staff Attorney, N<strong>in</strong>a Morrison: Senior Staff Attorney, Crist<strong>in</strong>a Najarro: Paralegal,Peter Neufeld: Co-Director, Karen Newirth: Eyewitness Identification Litigation Fellow, Jung-Hee Oh: Adm<strong>in</strong>istrativeAssociate, Legal Department, Cor<strong>in</strong>ne Padavano: F<strong>in</strong>ance and Human Resources Associate, Charlie Piper: SpecialAssistant, Vanessa Potk<strong>in</strong>: Senior Staff Attorney, Krist<strong>in</strong> Pulkk<strong>in</strong>en: Assistant Director of Individual Giv<strong>in</strong>g,N. Anthony Richardson: Policy Assistant, Stephen Saloom: Policy Director, Alana Salzberg: CommunicationsAssociate, Barry Scheck: Co-Director, Chester Soria: Communications Assistant, Maggie Taylor: Senior Case Analyst,Elizabeth Vaca: Assistant to the Directors, Marc Vega: Case Assistant, Elizabeth Webster: Publications Manager,Elizabeth Weill-Greenberg: Case Analyst, Emily West: Research Director, Karen Wolff: Social Worker

INNOCENCE PROJECT, INC.40 WORTH STREET, SUITE 701NEW YORK, NY 10013WWW.INNOCENCEPROJECT.ORGBENJAMIN N. CARDOZO SCHOOL OF LAW,YESHIVA UNIVERSITYDonate onl<strong>in</strong>e at www.<strong>in</strong>nocenceproject.org