Effectiveness of Neighbourhood Watch on Reducing Crime

Effectiveness of Neighbourhood Watch on Reducing Crime

Effectiveness of Neighbourhood Watch on Reducing Crime

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Effectiveness</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>Watch</str<strong>on</strong>g> In <strong>Reducing</strong> <strong>Crime</strong>Report prepared forThe Swedish Nati<strong>on</strong>al Council for<strong>Crime</strong> Preventi<strong>on</strong>

Brå – a centre <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> knowledge <strong>on</strong> crime and measures to combat crimeThe Swedish Nati<strong>on</strong>al Council for <strong>Crime</strong> Preventi<strong>on</strong> (Brottsförebyggande rådet – Brå)works to reduce crime and improve levels <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> safety in siciety by producing data anddisseminating knowledge <strong>on</strong> crime and crime preventi<strong>on</strong> work and the justice system’sresp<strong>on</strong>ses to crime.Producti<strong>on</strong>:Swedish Council for <strong>Crime</strong> Preventi<strong>on</strong>, Informati<strong>on</strong> and publicati<strong>on</strong>s,Box 1386, 111 93 Stockholm.Teleph<strong>on</strong>e +46(0)8 401 87 00, fax +46(0)8 411 90 75, e-mail info@bra.seThe Nati<strong>on</strong>al Council <strong>on</strong> the internet www.bra.seAuthors: Trevor H. Bennett, Katy R. Holloway, David P. Farringt<strong>on</strong>Cover illustrati<strong>on</strong>: Helena Halvarss<strong>on</strong>Cover: Anna GunneströmPrinting: Edita Norstedts Västerås 2008© Brottsförebyggande rådet 2008ISBN 978-91-85664-91-7

C<strong>on</strong>tentsForeword 5Acknowledgements 6Summary 6Introducti<strong>on</strong> 8Background 9The Theory <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Watch</str<strong>on</strong>g> 9Programme Elements 10Previous Reviews 11Research methods 13Criteria for Inclusi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Studies 13Coding Study Characteristics 15Attriti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Publicati<strong>on</strong>s 15Descripti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Studies Meeting the Eligibility Criteria 16Results 18Narrative Review 18Effect Sizes In Individual Evaluati<strong>on</strong>s 24Mean Effect Sizes 26Fixed Effects Model 27Random Effects Model 27Moderator Analyses 28C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>Research Implicati<strong>on</strong>s3030Implicati<strong>on</strong>s for Policy 31References 32Appendix 35Measuring effect size 35

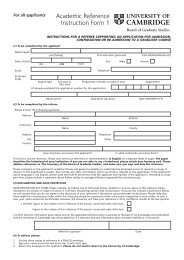

Foreword<str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g> watch schemes are a comm<strong>on</strong> method used to preventcrime in residential areas. But how well do they work? What does theresearch tell us? There are never sufficient resources to c<strong>on</strong>duct rigorousscientific evaluati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all the crime preventi<strong>on</strong> measures employed inindividual countries. Nor has an evaluati<strong>on</strong> been c<strong>on</strong>ducted in Sweden<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> efforts employing neighbourhood watch schemes to prevent crime.For this reas<strong>on</strong>, the Swedish Nati<strong>on</strong>al Council for <strong>Crime</strong> Preventi<strong>on</strong>(Brå) has commissi<strong>on</strong>ed three distinguished researchers to carry out aninternati<strong>on</strong>al review <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the research published in this field.This report presents a systematic review <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhoodwatch that has been c<strong>on</strong>ducted by Pr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>essor Trevor H. Bennet, Dr.Katy R. Holloway, both in University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Glamorgan, United Kingdomand Pr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>essor David P. Farringt<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Cambridge University, United Kingdom,who have also written the report. The study follows a rigorousmethod for the c<strong>on</strong>duct <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> systematic reviews. The analysis combinesthe results from a number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> evaluati<strong>on</strong>s that are c<strong>on</strong>sidered to satisfy alist <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> empirical criteria for measuring effects as reliably as possible. Theanalysis then uses the results from these previous evaluati<strong>on</strong>s to calculateand produce an overview <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the effects that a given measure doesand does not produce. Thus the objective in this instance is to systematicallyevaluate the results from a number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> studies from differentcountries in order to produce a more reliable picture <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the possibilitiesand limitati<strong>on</strong>s associated with neighbourhood watch initiatives in relati<strong>on</strong>to crime preventi<strong>on</strong> efforts. Studies <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this kind are also valuablewhen assessing which circumstances c<strong>on</strong>tribute to a certain measureproducing a positive effect.In this case, the research review builds up<strong>on</strong> a relatively small number<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> evaluati<strong>on</strong>s and examines mainly evaluati<strong>on</strong>s that have been c<strong>on</strong>ductedin the United States and the United Kingdom. A number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> questi<strong>on</strong>sc<strong>on</strong>cerning the potential crime preventive effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhoodwatch in a country like Sweden thus remain unanswered. But the studydoes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fer the most accessible overview to date <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhoodin order to prevent crime and improve public safety.Stockholm, February 2008Jan Anderss<strong>on</strong>Director-General5

AcknowledgementsWe would like to acknowledge the financial support <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the CampbellCollaborati<strong>on</strong> and the University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Glamorgan in the preparati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>the protocol and review. In particular, we are indebted to David B. Wils<strong>on</strong>for his methodological assistance and comments.Trevor H. BennettKaty R. HollowayDavid P. Farringt<strong>on</strong>6

Summary<str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g> watch (also known as block watch, apartment watch,home watch and community watch) grew out <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a movement in the USduring the late 1960s that promoted greater involvement <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> citizens in thepreventi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> crime. Since then, interest in neighbourhood watch hasgrown c<strong>on</strong>siderably and recent estimates suggest that over a quarter <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>the UK populati<strong>on</strong> and over forty per cent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the US populati<strong>on</strong> live inareas covered by neighbourhood watch schemes. The primary aim <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> thisreview is to assess the effectiveness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood watch in reducingcrime.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g> watch sometimes comprises a stand-al<strong>on</strong>e scheme andsometimes includes additi<strong>on</strong>al programme elements. The most comm<strong>on</strong>combinati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> programme elements is the ‘big three’ (neighbourhoodwatch, property marking and security surveys). Studies were selected forinclusi<strong>on</strong> in this review if they were based <strong>on</strong> a watch scheme either al<strong>on</strong>eor in combinati<strong>on</strong> with any <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the other ‘big three’ elements. The mainquality c<strong>on</strong>trol was that the studies should be based <strong>on</strong> random allocati<strong>on</strong>or a pre-post test design with a comparis<strong>on</strong> area.Studies were identified by searching 11 electr<strong>on</strong>ic databases. In additi<strong>on</strong>,studies were sought using <strong>on</strong>line library catalogues, literature reviews,lists <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> references, and published bibliographies. Leading researchersin the field were also c<strong>on</strong>tacted when there was a particular need to do so.The narrative review was based <strong>on</strong> 17 studies (covering 36 evaluati<strong>on</strong>s)and the meta-analysis was based <strong>on</strong> 12 studies (covering 18 evaluati<strong>on</strong>s).The data included police-recorded crimes and victimizati<strong>on</strong> surveys.The main finding <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the narrative review was that the majority <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> theschemes (19) indicated that neighbourhood watch was effective in reducingcrime, while <strong>on</strong>ly 6 produced negative results. The main finding <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>the meta-analysis was that neighbourhood watch was followed by a reducti<strong>on</strong>in crime <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> between 16 and 26 percent.This review c<strong>on</strong>cludes that across all studies neighbourhood watchwas followed by a reducti<strong>on</strong> in crime. However, it is not immediatelyclear why neighbourhood watch is effective. The analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> moderatorvariables failed to show any clear differences between more and less effectivestudies in terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> methods used or programme design. It is possiblethat the reducti<strong>on</strong>s in crime were associated with some <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the essentialfeatures <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood watch schemes. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g> watch mightserve to increase surveillance, reduce opportunities for crime or enhanceinformal social c<strong>on</strong>trol. Unfortunately, this kind <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> informati<strong>on</strong> is notprovided in the majority <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> evaluati<strong>on</strong>s and the precise reas<strong>on</strong>s for theresults are not clear at present. Nevertheless, the existing evidence justifiesthe c<strong>on</strong>tinued use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood watch and suggests that furtherresearch is needed to identify the key features <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> effective programmes.7

Introducti<strong>on</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g> watch is a widespread and popular crime preventi<strong>on</strong>measure. One <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> its main aims is to reduce crime and, in particular, toreduce residential burglary and other household and neighbourhood crime.It is <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten implemented as part <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a comprehensive package comprisingneighbourhood watch, property-marking and home security surveys(sometimes known as ‘the big three’). C<strong>on</strong>sidering the widespreadadopti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood watch, it is important to know whethersuch a large investment in time and m<strong>on</strong>ey has been effective in achievingthe aim <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> crime reducti<strong>on</strong>.There are several mechanisms by which neighbourhood watch mightreduce crime. One method is that it encourages residents to look out forsuspicious activities and report these to the police. This might have adeterrent effect <strong>on</strong> potential <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fenders who might perceive that surveillanceby residents increases their risks <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> being caught. It might also havethe effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> providing the police with useful informati<strong>on</strong> which mightlead to successful arrests and c<strong>on</strong>victi<strong>on</strong>s.The main aim <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this report is to c<strong>on</strong>duct a systematic review <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> theresearch literature to determine the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood watch <strong>on</strong>crime. The report is based <strong>on</strong> an updated and extended versi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> asystematic review c<strong>on</strong>ducted for the Campbell Collaborati<strong>on</strong> <strong>Crime</strong> andJustice Group. Systematic reviews use rigorous methods for locating andsynthesising evidence from evaluati<strong>on</strong> research and aim to be transparentand replicable in their approach. Attempts are made to obtain allpotentially relevant studies, including both published and unpublishedreports. Each study is screened to determine if it meets the criteria forinclusi<strong>on</strong> in the review. Relevant informati<strong>on</strong> is extracted from eacheligible study and coded for analysis. Quantitative techniques, such asmeta-analysis, are used to analyse and summarise the results.This report presents the results <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a systematic review <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> evaluati<strong>on</strong>s<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood watch. It summarises the findings through a narrativereview in which the results for each study are described and analysedand through a meta-analysis in which the results <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> each evaluati<strong>on</strong> areaggregated to determine the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood watch across allstudies combined.This report is divided into five main chapters. The first chapter is thisintroducti<strong>on</strong>. The sec<strong>on</strong>d chapter provides background informati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong>neighbourhood watch schemes, the theory behind them, and the mainprogramme elements. The third chapter discusses the methods used inthe review, including methods <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> searching for studies and the inclusi<strong>on</strong>criteria for the evaluati<strong>on</strong>s. The fourth chapter summarises the results <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>the narrative review and the meta-analyses. The final chapter drawsc<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s and discusses the implicati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the findings for policy andresearch.8

Background<str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g> watch grew out <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a movement in the US that promotedgreater involvement <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> citizens in the preventi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> crime (Titus,1984). It is also known as block watch, apartment watch, home watch,citizen alert and community watch. One <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the first evaluati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>neighbourhood watch programmes in the US was <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Seattle Community<strong>Crime</strong> Preventi<strong>on</strong> Project launched in 1973 (Cirel, Evans,McGillis, and Whitcomb, 1977). One <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the first evaluati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>neighbourhood watch schemes in the UK was <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Home <str<strong>on</strong>g>Watch</str<strong>on</strong>g> programmeimplemented in 1982 in Cheshire (Andert<strong>on</strong>, 1985).Since the 1980s, the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood watch schemes in theUK has expanded c<strong>on</strong>siderably. The report <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the 2000 British <strong>Crime</strong>Survey estimated that over a quarter (27 per cent) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all households(approximately six milli<strong>on</strong> households) in England and Wales weremembers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a neighbourhood watch scheme (Sims, 2001). This amountedto over 155,000 active schemes. A similar expansi<strong>on</strong> has occurredin the US. The report <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> The 2000 Nati<strong>on</strong>al <strong>Crime</strong> Preventi<strong>on</strong> Survey(Nati<strong>on</strong>al <strong>Crime</strong> Preventi<strong>on</strong> Council, 2001) estimated that 41 per cent<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the American populati<strong>on</strong> lived in communities covered by neighbourhoodwatch. The report c<strong>on</strong>cluded, ‘This makes <str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>Watch</str<strong>on</strong>g> the largest single organized crime preventi<strong>on</strong> activity in the nati<strong>on</strong>’(p.39). C<strong>on</strong>sidering such large investments in terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> resourcesand community involvement, it is important for researchers to investigatewhether neighbourhood watch is effective in reducing crime.The Theory <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Watch</str<strong>on</strong>g>The most frequently suggested mechanism by which neighbourhoodwatch is supposed to reduce crime is by residents looking out for suspiciousactivities and reporting these to the police (Bennett, 1990). Thelink between reporting and crime reducti<strong>on</strong> is not usually elaborated inthe literature. However, it has been argued that visible surveillancemight reduce crime as a result <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> its deterrent effect <strong>on</strong> the percepti<strong>on</strong>sand decisi<strong>on</strong> making <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> potential <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fenders (Rosenbaum, 1987). Hence,watching and reporting might deter <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fenders if they are aware <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> thelikelihood <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> local residents reporting suspicious behavior and if theyperceive this as increasing their risks <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> being caught.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g> watch might also lead to a reducti<strong>on</strong> in crime byreducing opportunities for crime, for example by creating signs <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> occupancy.Some <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the methods by which members <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhoodwatch schemes might create signs <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> occupancy were discussed in thereport <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Seattle scheme (Cirel et al., 1977). These include removingnewspapers and milk from outside neighbours’ homes when they areaway, mowing the lawn, and filling up trash cans. The way in which9

signs <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> occupancy might reduce crime might be through the effect thatthis has <strong>on</strong> the percepti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> potential <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fenders <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> their likelihood <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>getting caught. For example, potential burglars prefer to choose unoccupiedhouses (Bennett and Wright, 1984).<str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g> watch might also lead to a reducti<strong>on</strong> in crimethrough the various mechanisms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> social c<strong>on</strong>trol. Informal social c<strong>on</strong>trolis not <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the methods <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> reducing crime stated in the publicitymaterial <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these schemes. Nevertheless, the schemes might indirectlyserve to enhance community cohesi<strong>on</strong> and increase the ability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> communitiesto c<strong>on</strong>trol crime (Greenberg, Rohe, and Williams, 1985). Informalsocial c<strong>on</strong>trol can affect community crime through the communicati<strong>on</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> acceptable norms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> behavior and by direct interventi<strong>on</strong> byresidents.It is also possible that neighbourhood watch schemes might reducecrime through enhancing police detecti<strong>on</strong>. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g> watch mightserve to increase the flow <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> useful informati<strong>on</strong> from the public to thepolice. An increase in informati<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>cerning crimes in progress andsuspicious pers<strong>on</strong>s and events might lead to a greater number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> arrestsand c<strong>on</strong>victi<strong>on</strong>s and result (when a custodial sentence is passed) in areducti<strong>on</strong> in crime through the incapacitati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> local <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fenders (Bennett,1990).It is also feasible that neighbourhood watch might reduce crimethrough the other comp<strong>on</strong>ents <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the programme package. It has beenargued that property marking might lead to a reducti<strong>on</strong> in crime as aresult <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> making the disposal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> marked property more difficult (Laycock,1985). This might reduce <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fending rates if potential <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fendersviewed marked property as increasing the risk <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> detecti<strong>on</strong>. Home securitysurveys might lead to a reducti<strong>on</strong> in crime as a result <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> making itphysically more difficult for an <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fender to enter the property (Bennettand Wright, 1984).Programme Elements<str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g> watch is <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten implemented as part <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a comprehensivepackage. The typical package is sometimes referred to as the ‘big three’and includes neighbourhood watch, property-marking and home securitysurveys (Titus, 1984). Some programmes include other elementssuch as a recruitment drive for special c<strong>on</strong>stables, increased regular footpatrols, citizen patrols, educati<strong>on</strong>al programmes for young people, auxiliarypolice units, and victim support services.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g> watch schemes vary in the size <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the area covered.Some <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the earlier schemes in the US and the UK were based <strong>on</strong> areascovering just a few households. More recent schemes sometimes covermany thousand households (Knowles, 1983). One <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the smallest schemesincluded in this review was the ‘coco<strong>on</strong>’ neighbourhood watch programmein Rochdale in England covering just <strong>on</strong>e dwelling and its im-10

mediate neighbours (Forrester, Frenz, O’C<strong>on</strong>nell, and Pease, 1990). One<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the largest was the Manhattan Beach neighbourhood watch schemein Los Angeles covering a populati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> over 30,000 residents (Knowles,1983).<str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g> watch schemes can be initiated by residents or police.Schemes launched in the UK initially tended to be police-initiated(e.g. the early neighbourhood watch schemes in L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong>). More recently,neighbourhood watch schemes have been launched mainly at therequest <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the public. Some police departments c<strong>on</strong>tinue initiating theirown schemes, even when the programme is fully developed. A programmeimplemented in Detroit, for example, developed a secti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>police-initiated schemes in order to promote neighbourhood watch inareas that were unlikely to generate public-initiated requests (Turnerand Barker, 1983).In the US, block watches are usually run by a block captain who isresp<strong>on</strong>sible to a block coordinator or block organizer. The block coordinatoracts as the liais<strong>on</strong> pers<strong>on</strong> to the local police department.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g> watch schemes in the UK <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten include street coordinators(equivalent to block captains) and area coordinators (equivalent tothe block organizer). There is little informati<strong>on</strong> in the research literature<strong>on</strong> the number and type <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood watch meetings. The evidencethat does exist suggests that some schemes have public meetingsthat involve all <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the residents participating in the scheme, while othershave meetings that involve <strong>on</strong>ly the organizers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the scheme (Bennett,1990).The funding <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood watch schemes is nearly always ajoint venture between the local police department and the scheme membersthrough their fundraising activities. The relative c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> thetwo sources varies c<strong>on</strong>siderably. Some schemes in the United States areprovided with no more than an informati<strong>on</strong> package from the localpolice. Others are provided with police facilities for the producti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>newsletters and the use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> police premises for meetings (Turner andBarker, 1983). Apart from police funding, the majority <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> schemes areencouraged to raise some funds from other sources such as voluntaryc<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong>s, local businesses, and the proceeds <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fairs and raffles.Previous ReviewsThere are several previous reviews that include evaluati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhoodwatch programmes. One <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the earliest c<strong>on</strong>ducted in the USwas by Titus (1984) who summarized the results <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> nearly forty communitycrime preventi<strong>on</strong> programmes. Most <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these included elements<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood watch. The majority <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> studies were c<strong>on</strong>ducted bypolice departments or included data from police departments. Nearly allfound that neighbourhood watch areas tended to have relatively low11

levels <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> crime. However, most <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the evaluati<strong>on</strong>s were described as‘weak’ in terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> their ability to guard against threats to validity.Another review <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the literature looked mainly at community watchprogrammes in the UK (Husain, 1990). This study reviewed the results<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> nine existing evaluati<strong>on</strong>s and c<strong>on</strong>cluded that there was little evidencethat neighbourhood watch prevented crime.One <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the most recent reviews <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the literature <strong>on</strong> the effectiveness<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> community watch programmes selected <strong>on</strong>ly evaluati<strong>on</strong>s with thestr<strong>on</strong>gest research designs (Sherman et al., 1997). The review included<strong>on</strong>ly studies that used random assignment or studies that m<strong>on</strong>itoredboth watch areas and similar comparis<strong>on</strong> areas without communitywatch. The review found <strong>on</strong>ly four evaluati<strong>on</strong>s that matched these criteria.The results <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these evaluati<strong>on</strong>s were largely negative. The authorsc<strong>on</strong>cluded, ‘The oldest and bestknown community policing program,<str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Watch</str<strong>on</strong>g>, is ineffective at preventing crime’ (p.8–25).Similar c<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s were drawn in the later update <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this report(Sherman and Eck, 2002).12

Research methodsCriteria for Inclusi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> StudiesThe criteria for inclusi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> studies in the current review were based <strong>on</strong>three broad categories: the type <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> interventi<strong>on</strong>, the type <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> outcome andthe type <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> evaluati<strong>on</strong> design.The main aim <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the type <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> interventi<strong>on</strong> criteria was to include studiesthat evaluated neighbourhood watch schemes. In practice, this ismore difficult to determine than it might seem as neighbourhood watchschemes are <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten implemented al<strong>on</strong>gside other programme elements. Asmenti<strong>on</strong>ed, the most comm<strong>on</strong> other elements are property marking andsecurity surveys. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g> watch is also sometimes implementedas part <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> broader area improvements and may exist al<strong>on</strong>gside otherunrelated crime reducti<strong>on</strong> initiatives. Hence, the selecti<strong>on</strong> criteria relatingto the type <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> interventi<strong>on</strong> included <strong>on</strong>ly the following programmetypes and combinati<strong>on</strong>s:1. Stand-al<strong>on</strong>e neighbourhood watch schemes (comprising solely awatch comp<strong>on</strong>ent).2. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g> watch schemes that include ‘the big three’(neighbourhood watch, property marking and security surveys)as l<strong>on</strong>g as there was a watch comp<strong>on</strong>ent.3. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g> watch schemes that include two comp<strong>on</strong>ents <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>‘the big three’ as l<strong>on</strong>g as there was a watch comp<strong>on</strong>ent.4. Comprehensive programmes that include neighbourhood watch(any versi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the above) and other unrelated schemes (such asenvir<strong>on</strong>mental improvements), as l<strong>on</strong>g as the independent effects<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the neighbourhood watch comp<strong>on</strong>ent were identified in theevaluati<strong>on</strong> or neighbourhood watch was the major comp<strong>on</strong>ent<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the programme.The main aim <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the type <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> outcome criteria was to focus the evaluati<strong>on</strong><strong>on</strong> crime outcomes. We were not interested in this review in determiningthe impact <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood watch <strong>on</strong> fear <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> crime, residents’satisfacti<strong>on</strong> with their area, or police-community relati<strong>on</strong>s. Instead, wesought to determine whether neighbourhood watch succeeded in meetingits primary objective <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> reducing residential burglary and relatedneighbourhood crimes. The types <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> crimes included in the review were:1. crimes against residents2. crimes against dwellings3. other (street) crimes occurring in residential areas.13

The aim <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the type <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> evaluati<strong>on</strong> design criteria was to include studies<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the highest quality in regard to the research methods used. The mainmethod for selecting rigorous evaluati<strong>on</strong>s was based <strong>on</strong> the MarylandScientific Methods Scale (SMS) (Farringt<strong>on</strong> et al., 2002; Sherman, etal.,1997; Sherman and Eck, 2002). This is a five-point scale rangingfrom level 1 (the weakest design) to level 5 (the str<strong>on</strong>gest design) interms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> overall internal validity. Sherman and Eck (2002) argue thatevaluati<strong>on</strong>s should be at least level 3 in order to make it possible to c<strong>on</strong>cludewith a reas<strong>on</strong>able level <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> certainty that the programme worked.The present review <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> evaluati<strong>on</strong>s uses level 3 as the minimum acceptablefor inclusi<strong>on</strong> in the review. This level requires that the evaluati<strong>on</strong>must include at least a comparis<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong>e or more experimental unitsand <strong>on</strong>e or more comparable c<strong>on</strong>trol units over time. Hence, the minimumrequirement for inclusi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> evaluati<strong>on</strong>s in this review is that theyare based <strong>on</strong> before and after measures <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> crime in experimental (neighbourhoodwatch) and comparis<strong>on</strong> areas.Search StrategyThe main goal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the strategy for searching the literature was to be asexhaustive as possible in obtaining relevant evaluati<strong>on</strong>s. This meantthat we were willing to include published and unpublished studies, withno restricti<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> country <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> origin or source sector (e.g. academic, government,policy, or voluntary). We could <strong>on</strong>ly include studies written inEnglish as we had no research funds for translati<strong>on</strong>. We used the followingsearch strategies for locating studies:1. Searches <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong>line databases (especially for reports and articles).Wec<strong>on</strong>ducted searches <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the following electr<strong>on</strong>ic databasesand websites: IBSS (Internati<strong>on</strong>al Bibliography <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the SocialSciences), Web <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Science, Criminal Justice Abstracts, Nati<strong>on</strong>alCriminal Justice Reference Service Abstracts, SociologicalAbstracts, Psychological Abstracts (PsycINFO), Social ScienceAbstracts, UK Government Publicati<strong>on</strong>s (Home Office), Dissertati<strong>on</strong>Abstracts (ASSIA), ProQuest, and C2-SPECTR.2. Searches <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong>line library catalogues (especially for books).These included the Radzinowicz Library, University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Cambridgeand the Rutgers University Library.3. Searches <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> reviews <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the literature <strong>on</strong> the effectiveness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>neighbourhood watch in preventing crime. These included reviewsby Titus (1984), Husain (1990), Sherman et al, (1997),and Sherman and Eck (2002).4. Searches <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> bibliographies <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> publicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> neighbourhoodwatch. These included the references in all publicati<strong>on</strong>s selectedas eligible for the review.14

5. C<strong>on</strong>tacting leading researchers. These included DennisRosenbaum and Wesley Skogan who worked <strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the largestevaluati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood watch.We used the following search terms when searching <strong>on</strong>line databases:‘neighbourhood watch’, ‘neighborhood watch’, ‘street watch’, ‘blockwatch’, ‘apartment watch’, ‘home watch’, ‘community watch’, ‘homealert’, ‘block associati<strong>on</strong>’, ‘crime alert’, ‘block clubs’, ‘crime watch’, ‘bigthree’.Coding Study CharacteristicsStudies determined as eligible for inclusi<strong>on</strong> in the systematic review werecoded and the data were entered into a database. One researcher enteredthe data and this was then checked for accuracy by a sec<strong>on</strong>d researcher.Any discrepancies in coding were discussed and an agreementwas reached <strong>on</strong> the correct figures to be used. The database includedbasic informati<strong>on</strong> about the study (e.g. author(s), year <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> publicati<strong>on</strong>,country <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> study), details <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the programme (e.g. type <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> programme,programme elements, size <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> area, type <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> area), research design (e.g.type <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> design, sample size, length <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> followup period, type <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> comparis<strong>on</strong>areas), and outcomes (type <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fence, pre- and post-test measuresfor experimental and c<strong>on</strong>trol areas).In some cases, evaluati<strong>on</strong>s produced multiple outcome measures.This occurred when there were multiple methods <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> measuring the sameoutcome and when the same outcome was measured at multiple pointsin time. In these cases, a method <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> selecting outcomes was established.When multiple outcome measures were provided (e.g. multiple outcomemeasures <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> crime) we listed the results for each measure. However, anysingle analysis was based <strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong>ly <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these measures. The measurechosen was based <strong>on</strong> a system for prioritizing the results (i.e. burglaryfirst, followed by all property crimes and then all crimes). When thesame outcome was measured at multiple points in time, we selected theyear before and the year after the implementati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the scheme as thebasis for our analyses. Failing this, we chose other periods in accordancewith the above priority system (i.e. periods nearest to the point <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> implementati<strong>on</strong>were chosen first).Attriti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Publicati<strong>on</strong>sA total <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1,595 potentially relevant reports were identified from thesearches. Reports that were clearly not evaluati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhoodwatch were excluded. Overall, 335 reports were selected as possibleevaluati<strong>on</strong>s. One hundred and ten <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these reports were duplicates andwere excluded from the list. This left 225 unique reports. Of the 225selected reports, 137 were obtained. The main reas<strong>on</strong>s for not obtaining15

eports were that they could not be located following various attemptsto obtain them through interlibrary loan, through the internet, or byc<strong>on</strong>tacting the authors. Another reas<strong>on</strong> for the losses was that many <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>the evaluati<strong>on</strong>s were included in unpublished reports by police departmentsand other <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ficial agencies and had not been deposited in copyrightlibraries that hold copies <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all nati<strong>on</strong>al publicati<strong>on</strong>s.Thirty <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the 137 reports obtained were c<strong>on</strong>sidered eligible for inclusi<strong>on</strong>in the review. The main reas<strong>on</strong> for ineligibility was that the reportdid not include an evaluati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood watch, but for example,was a descripti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a neighbourhood watch programme or a processevaluati<strong>on</strong>. Eleven <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the 30 eligible reports presented results that wereincluded in another eligible report. In other words the results <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> thestudy were published in two or more reports. In these cases, the mostdetailed report was selected for inclusi<strong>on</strong> in this review. This left 19unique studies including 43 separate evaluati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhoodwatch schemes. Two studies including seven evaluati<strong>on</strong>s were excluded<strong>on</strong> the grounds that the results were presented in graphical form <strong>on</strong>ly.This left 17 studies including 36 evaluati<strong>on</strong>s that were included in thenarrative review.Descripti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Studies Meeting theEligibility CriteriaTable 1 summarises the characteristics <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the 36 evaluati<strong>on</strong>s included inthe narrative review. All were c<strong>on</strong>ducted during the period 1977 to1994. No eligible evaluati<strong>on</strong>s were found after the mid 1990s. Abouthalf were c<strong>on</strong>ducted in North America and about half in the UK. Therewas <strong>on</strong>e study from Canada and <strong>on</strong>e study from Australia. Most evaluati<strong>on</strong>s(23) c<strong>on</strong>cerned a neighbourhood watch scheme with no other programmeelements, but 13 assessed a comprehensive package includingproperty marking and/or security surveys. Only a minority <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> evaluati<strong>on</strong>s(10) were based <strong>on</strong> any kind <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> matching <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> comparis<strong>on</strong> with experimentalareas. The remainder used either similar nearby areas orlarger areas with no matching at all (e.g. the remainder <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the policeforce area). In some cases, the comparis<strong>on</strong> area was the whole policeforce, including the neighbourhood watch area. In these cases, crimes inthe experimental area should have been subtracted from crimes in thetotal area, but in practice this would have made very little difference tothe results.Half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the evaluati<strong>on</strong>s (18) used police-recorded crime data as themain outcome measure, while the other 18 used victimizati<strong>on</strong> surveydata. Twenty-five <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the evaluati<strong>on</strong>s were categorized as published and11 as not published. Evaluati<strong>on</strong>s were defined as published if they werereported in a book, journal or <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ficial government report, as these werelikely to have been externally reviewed before distributi<strong>on</strong>. Unpublished16

evaluati<strong>on</strong>s included police reports and reports from survey researchcompanies, which were unlikely to have been externally reviewed beforedistributi<strong>on</strong>. Most schemes (25) were implemented in relatively largeareas (greater than 1000 dwellings or 1 census tract).Table 1. Descripti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Studies and Methods.Author (publicati<strong>on</strong> date) 1n=17No. <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>evaluati<strong>on</strong>sn=36Scheme Published Dataelements 2 sourceSize <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>schemearea 3Comparis<strong>on</strong>area 4Andert<strong>on</strong> (1985) 1 NW plus Not published Police Large Not matchedBennett (1990) 2 NW plus Published Survey Small MatchedBennett and Lavrakas (1989) 10 NW <strong>on</strong>ly Published Survey Large Not matchedCirel et al. (1977) 1 NW plus Published Survey Large Not matchedForester, Chattert<strong>on</strong> and Pease(1988) 1 NW plus Published Police Large Not matchedHenig (1984) 1 NW <strong>on</strong>ly Not published Police Large Not matchedHulin (1979) 1 NW plus Published Police Small MatchedJenkins and Latimer (1986) 4 NW <strong>on</strong>ly Not published Police Small Not matchedKnowles, Lesser and McKewen(1983) 1 NW plus Not published Police Large Not matchedLatessa and Travis (1987) 1 NW plus Published Police Large Not matchedLewis, Grant and Rosenbaum(1988) 5 NW <strong>on</strong>ly Published Survey Large MatchedLowman (1983) 1 NW plus Published Police Small Not matchedMatthews and Trickey (1994a) 1 NW plus Not published Police Large Not matchedMatthews and Trickey (1994b) 1 NW plus Not published Police Large Not matchedResearch and Forecasts Inc.(1983) 1 NW plus Not published Police Large MatchedTilley and Webb (1994) 3 NW <strong>on</strong>ly Published Police Small Not matchedVeater (1984) 1 NW plus Not published Police Large MatchedNotes:1Publicati<strong>on</strong> date <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the main report used in review.2NW plus = neighbourhood watch plus security surveys and/or property marking. NW <strong>on</strong>ly = neighbourhoodwatch but not security surveys or property marking.3Small = 1,000 dwellings or less or 1 census tract or less. Large = greater than 1,000 dwellings or 1 censustract.4Matched areas = Comparis<strong>on</strong> areas that are specifically matched or comparable with the experimental areas.N<strong>on</strong>-matched areas = Comparis<strong>on</strong> areas are not specifically matched or comparable with the experimentalareas. These include the remainder <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the police divisi<strong>on</strong> or police force area or other nearby areas chosensolely <strong>on</strong> the grounds <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> distance from the experimental site.17

ResultsTwo methods are used here to summarise the results <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the selectedstudies. The first is a narrative review, which presents details <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> thestudies and the results obtained. The findings are presented in the form<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the relative percentage change in crime in the experimental area comparedwith the c<strong>on</strong>trol area. The review also includes the author’s c<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>and other textual comments found in the research publicati<strong>on</strong>.The sec<strong>on</strong>d method is a meta-analysis, which involves recalculating thepublished findings to produce a comm<strong>on</strong> effect size in each study.The main advantage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a narrative review is that more details aregiven about each study and it is possible to include more studies in thereview. Some reports do not provide sufficient data to be included in themeta-analysis. The main disadvantage is that it is difficult to draw anoverall c<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong> for all studies combined. The main advantage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ameta-analysis is that a single weighted mean effect size can be calculatedfor groups <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> studies or all studies combined. The main disadvantage isthat meta-analysis can <strong>on</strong>ly be used when there is sufficient informati<strong>on</strong>provided in the original report to calculate an effect size. In the followingsecti<strong>on</strong> we present the findings <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> both methods.Narrative ReviewOne <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the aims <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Table 2 is to show whether the study found thatneighbourhood watch had a positive effect (a greater reducti<strong>on</strong> orsmaller increase in crime than the comparis<strong>on</strong> area), an uncertain effect,or a negative effect (a smaller reducti<strong>on</strong> or greater increase in crime thanthe comparis<strong>on</strong> area). This was calculated from the published results <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>the study in <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> two ways depending <strong>on</strong> whether the results werepresented as numbers or coefficients.When the results were presented as raw numbers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> crimes or as percentages,a relative change score was calculated showing the differencebetween the change in the experimental area and the change in the comparis<strong>on</strong>area. For example, Anders<strong>on</strong> (1985) reported a 10 per cent decreasein crime in the experimental area and a 3 per cent increase incrime in the c<strong>on</strong>trol area, yielding a relative change score <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> -13 per cent(-10 per cent – 3 per cent). In order to assess whether this difference wasnoteworthy, we defined a relative reducti<strong>on</strong> in the neighbourhoodwatch area <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 9 per cent or more as a positive effect and a relative increasein the neighbourhood watch area <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 10 per cent or more as a negativeeffect. These effects are symmetrically opposite (an increase from 1to 1.10 or a decrease from 1 to 1/1.10). Effects in between were c<strong>on</strong>sidereduncertain when the results were presented as adjusted means or asregressi<strong>on</strong> coefficients the significance and directi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the effect werepresented (e.g. a significant positive effect, no significant effect or a significantnegative effect).18

Table 2. Outcome <str<strong>on</strong>g>Effectiveness</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Neighbourhood</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Watch</str<strong>on</strong>g>.Author (publicati<strong>on</strong> date)n=36Data Resultsource % crime differenceRelative % changeminus=favourableplus=unfavourableOutcomeAndert<strong>on</strong> (1985) PD Exp -10%; C<strong>on</strong> +3% -13% PositiveBennett (1990) (1) SD Exp -22%; C<strong>on</strong> -28% +6% UncertainBennett (1990) (2) SD Exp +37%; C<strong>on</strong> -28% +65% NegativeBennett and Lavrakas (1989) (1) SD % not available Sig. negative. NegativeBennett and Lavrakas (1989) (2) SD % not available n.s. UncertainBennett and Lavrakas (1989) (3) SD % not available n.s. UncertainBennett and Lavrakas (1989) (4) SD % not available n.s. UncertainBennett and Lavrakas (1989) (5) SD % not available Sig. positive PositiveBennett and Lavrakas (1989) (6) SD % not available n.s. UncertainBennett and Lavrakas (1989) (7) SD % not available n.s. UncertainBennett and Lavrakas (1989) (8) SD % not available Sig. negative. NegativeBennett and Lavrakas (1989) (9) SD % not available n.s. UncertainBennett and Lavrakas (1989) (10) SD % not available n.s. UncertainCirel et al. (1977) SD Exp -61%; C<strong>on</strong> -4% -57% PositiveForrester, Chattert<strong>on</strong> andPease (1988) PD Exp -38%; C<strong>on</strong> +1% -39% PositiveHenig (1984) PD Exp -100%; C<strong>on</strong> -35% -65% PositiveHulin (1979) PD Exp -26%; C<strong>on</strong> +10% -36% PositiveJenkins and Latimer (1986) (1) PD Exp -25%; C<strong>on</strong> +2% -27% PositiveJenkins and Latimer (1986) (2) PD Exp +1100%; C<strong>on</strong> +20% +1,080% NegativeJenkins and Latimer (1986) (3) PD Exp -75%; C<strong>on</strong> -29% -46% PositiveJenkins and Latimer (1986) (4) PD Exp -71%; C<strong>on</strong> -25% -46% PositiveKnowles, Lesser and McKewen(1983) PD Exp -28%; C<strong>on</strong> +13% -41% PositiveLatessa and Travis (1987) PD Exp -11%; C<strong>on</strong> -2% -9% PositiveLewis, Grant and Rosenbaum(1988) (1) SD Exp -21%; C<strong>on</strong> -11% Sig. positive PositiveLewis, Grant and Rosenbaum(1988) (2) SD Exp +23%; C<strong>on</strong> -27% Sig. negative. NegativeLewis, Grant and Rosenbaum(1988) (3) SD Exp +10%; C<strong>on</strong> -18% Sig. negative. NegativeLewis, Grant and Rosenbaum(1988) (4) SD % not available n.s. UncertainLewis, Grant and Rosenbaum(1988) (5) SD % not available n.s. UncertainLowman (1983) PD Exp -33%; C<strong>on</strong> 0% -33% PositiveMatthews and Trickey (1994a) (1) PD Exp -20%; C<strong>on</strong> -17% -3% UncertainMatthews and Trickey (1994b) (2) PD Exp +24%; C<strong>on</strong> +45% -21% PositiveResearch and Forecasts Inc.(1983) PD Exp -48%; C<strong>on</strong> -4% -44% PositiveTilley and Webb (1994) (1) PD Exp -41%; C<strong>on</strong> -11% -30% PositiveTilley and Webb (1994) (2) PD Exp 0%; C<strong>on</strong> +12% -12% PositiveTilley and Webb (1994) (3) PD Exp -13%; C<strong>on</strong> +12% -25% PositiveVeater (1984) PD Exp -25%; C<strong>on</strong> +31% -56% PositiveNotes: PD=Police-recorded crime data; SD=Survey data.The narrative analysis c<strong>on</strong>cluded that 53 per cent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> evaluati<strong>on</strong>s (19studies) showed that neighbourhood watch had a significant desirableeffect <strong>on</strong> crime. The remainder showed an uncertain effect (11 studies)or an undesirable effect (6 studies). Overall, the results are mixed, with<strong>on</strong>ly slightly more evaluati<strong>on</strong>s providing evidence that neighbourhoodwatch was effective than those providing uncertain evidence or evidence<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> an unfavourable effect. However, the comparis<strong>on</strong> between 19 posi-19

tive results and <strong>on</strong>ly 6 negative results suggests that neighbourhoodwatch is effective in reducing crime.Short summaries <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the 17 studies (covering 36 evaluati<strong>on</strong>s) includedin the narrative review are presented below.ANDERTON (1985) c<strong>on</strong>ducted an evaluati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a ‘Home <str<strong>on</strong>g>Watch</str<strong>on</strong>g>’scheme in Northwich in Cheshire. This was <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the first evaluati<strong>on</strong>s<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood watch in the UK. The study was based <strong>on</strong> a comparis<strong>on</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> police-recorded crimes measured 18 m<strong>on</strong>ths before and 30m<strong>on</strong>ths after the launch <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the scheme. The crime rates for Northwichwere compared with the crime rates for Cheshire as a whole. The resultsshowed that the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> burglaries in Northwich decreased by 10 percent, compared with an increase <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> three per cent across the county as awhole. Andert<strong>on</strong> (1985) c<strong>on</strong>cluded that, ‘It appears from the experiencein Cheshire so far that Home <str<strong>on</strong>g>Watch</str<strong>on</strong>g> is <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the most effective, efficientand successful crime preventi<strong>on</strong> initiatives ever undertaken’ (p.53).BENNETT (1990) evaluated the effectiveness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood watchschemes in two areas <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong> (Wimbled<strong>on</strong> and Act<strong>on</strong>). The evaluati<strong>on</strong>swere based <strong>on</strong> crime and public attitude surveys in the two areasbefore the schemes were implemented and again <strong>on</strong>e year after theirimplementati<strong>on</strong>. Similar surveys were c<strong>on</strong>ducted in matched comparis<strong>on</strong>areas some distance from the experimental areas. In Wimbled<strong>on</strong>, crimedecreased by a greater amount in the c<strong>on</strong>trol area than in the experimentalarea (28 per cent compared with 22 per cent). In Act<strong>on</strong>, crimeincreased by 37 per cent in the experimental area and decreased by 28per cent in the c<strong>on</strong>trol area. The author c<strong>on</strong>cluded that the findingswere ‘not encouraging’ (p.110). Overall, the results suggested that residentsin the neighbourhood watch areas experienced either no better orworse rates <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> victimizati<strong>on</strong> than in the comparis<strong>on</strong>.BENNETT AND LAVRAKAS (1989) investigated the effectiveness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>neighbourhood watch schemes in 10 US cities (Baltimore, Bost<strong>on</strong>,Br<strong>on</strong>x, Brooklyn, Cleveland, Miami, Minneapolis, Newark, Philadelphiaand Washingt<strong>on</strong>). The research was based <strong>on</strong> a pretest – posttestdesign with a n<strong>on</strong>-equivalent c<strong>on</strong>trol group. The comparis<strong>on</strong> areas wereselected by drawing a ‘ring’ around the experimental area approximatelytwo census tracts wide. M<strong>on</strong>thly crime statistics revealed no differencesbetween the experimental and c<strong>on</strong>trol areas in seven <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the tenevaluati<strong>on</strong>s and a negative differential change (where crime decreasedless in the experimental area than in the comparis<strong>on</strong> area) in two <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> thecities. Only <strong>on</strong>e area showed a desirable differential change (where theexperimental area experienced a larger decrease in crime than the c<strong>on</strong>trol).The authors c<strong>on</strong>cluded that the programs ‘did not seem to achievethe ‘ultimate’ goal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> crime reducti<strong>on</strong>’ (p.361).CIREL ET AL. (1977) c<strong>on</strong>ducted <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the first evaluati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> theeffectiveness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood watch in the United States. The evaluati<strong>on</strong>,based in Seattle, Washingt<strong>on</strong>, included a teleph<strong>on</strong>e and door-todoorsurveys <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> residents <strong>on</strong>e year before the launch <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the scheme and20

<strong>on</strong>e year after. Two census tracts adjacent to the neighbourhood watcharea was used as a comparis<strong>on</strong>. The results showed that the rate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> burglarydecreased by a substantially greater amount in the experimentalareas than in the c<strong>on</strong>trol areas (61 per cent compared with 4 per cent).The authors c<strong>on</strong>cluded that participating in community crime preventi<strong>on</strong>,‘significantly reduces the risk <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> residential burglary victimizati<strong>on</strong>’ (p.79).FORRESTER, CHATTERTON AND PEASE (1988) evaluated a burglarypreventi<strong>on</strong> project in Kirkholt, an area <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> public housing near Rochdale(a town 10 miles north <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Manchester) in the UK. A package <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> measureswas introduced as part <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the project, including ‘coco<strong>on</strong>’neighbourhood watch. The evaluati<strong>on</strong> was based <strong>on</strong> the analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> preandpost-test police-recorded crime rates in the experimental area(Kirkholt) which were compared with crime rates in the remainder <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>the police sub-divisi<strong>on</strong>. The results showed that domestic burglariesdecreased by 38 per cent in the experimental area compared with <strong>on</strong>eper cent in the remainder <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the subdivisi<strong>on</strong>. The authors c<strong>on</strong>cluded thatthere had been a, ‘large absolute and proporti<strong>on</strong>ate reducti<strong>on</strong> in domesticburglary during the initiative’ (p.19).HENIG (1984) c<strong>on</strong>ducted an evaluati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood watch in apolice district in Washingt<strong>on</strong>, DC. The impact <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> block watch <strong>on</strong> crimewas assessed by examining the levels <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> police-recorded crime in thesample <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> participating blocks in the year before and after the schemehad been launched. This was compared with crime rates for the policedistrict as a whole and for the city as a whole. The results showed thatover the evaluati<strong>on</strong> period the level <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> burglary decreased by 100 percent (from 4 to 0 burglaries) in the sample area and by 35 per cent(from 2745 to 1778 burglaries) in the police district as a whole. Theauthor c<strong>on</strong>cluded that neighbourhood watch was associated with a reducti<strong>on</strong>in burglary am<strong>on</strong>g participating blocks.HULIN (1979) evaluated the effectiveness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a neighbourhood watchscheme in a high crime area <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> F<strong>on</strong>tana, California. Using policerecordedcrime data for the year before and the year after the scheme,the author compared changes in residential burglary rates in F<strong>on</strong>tanawith changes in burglary in four demographically similar c<strong>on</strong>trol areaswith similar pre-test crime rates. The results showed a decrease in residentialburglary <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> more than 25 per cent in the experimental area comparedwith increases ranging from 10 to 25 per cent in each <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the c<strong>on</strong>trolareas. Hulin (1979) c<strong>on</strong>cluded that the results were ‘positive’ andindicated that neighbourhood watch was ‘an effective crime preventi<strong>on</strong>instrument’ (p.30).JENKINS AND LATIMER (1986) c<strong>on</strong>ducted evaluati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhoodwatch schemes in four areas <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Merseyside in the UK. Each <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> thefour evaluati<strong>on</strong>s examined the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> crimes recorded by the policein the year before and the year after the scheme had been implemented.In three <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the four areas, the experimental area experienced larger decreasesin the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> burglaries than in the sub-divisi<strong>on</strong> as a whole.21

In the fourth area (Burford Avenue), burglary increased by more than1,000 per cent (from 1 to 12). The authors c<strong>on</strong>cluded that there is, ‘anindicati<strong>on</strong> that Homewatch is having an effect, certainly initially, inreducing the instances <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> burglary within an area and to a lesser extentthe total crime’ (p.12). However, they warned that results <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the BurfordAvenue scheme ‘should not be ignored and indicate that Homewatchis not a panacea for reducing crime’ (p.12).KNOWLES, LESSER AND MCKEWEN (1983) evaluated the effectiveness<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a neighbourhood watch programme in a residential suburb <strong>on</strong> thewestern boundary <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Los Angeles County in the USA. The evaluati<strong>on</strong>examined changes in the rate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> police-recorded residential burglaries inthe 12 m<strong>on</strong>ths before and the 12 m<strong>on</strong>ths after the programme had beenimplemented. These were compared with burglary rates in comparis<strong>on</strong>areas (comprising eight neighbouring jurisdicti<strong>on</strong>s). The results showeda decrease in burglary <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 28 per cent in the experimental area, comparedwith an increase <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 13 per cent in the comparis<strong>on</strong> area. The authorsexplained that the atmosphere <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> cooperati<strong>on</strong> fostered by the programme,‘provided for the achievement <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a comm<strong>on</strong> goal – crime c<strong>on</strong>trol’(p 38).LATESSA AND TRAVIS (1987) c<strong>on</strong>ducted an evaluati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a blockwatch programme implemented in the College Hill area <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Cincinnati inthe USA. College Hill is described by the authors as the fifth largestcommunity in the city with a populati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> over 17,000 residents. Usingpolice-recorded crime data, burglary rates in College Hill in the yearbefore and after the scheme were compared with burglary rates in thecity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Cincinnati as a whole. The figures showed that burglary in theexperimental area decreased by 11 per cent, while burglary in Cincinnatias whole decreased by two per cent. The authors c<strong>on</strong>cluded thatCollege Hill experienced a decrease in the amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> recorded crimeduring the course <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the programme.LEWIS, GRANT AND ROSENBAUM (1988) in another US study, evaluatedthe effectiveness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> five block watch schemes in Chicago, Illinois.<strong>Crime</strong> and public attitude surveys were c<strong>on</strong>ducted in the experimentaland matched c<strong>on</strong>trol areas before the launch <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the schemes and again<strong>on</strong>e year after the launch. Only <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the five experimental areas experienceda reducti<strong>on</strong> in victimizati<strong>on</strong>s. Two <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the experimental areas,however, showed a statistically significant increase in victimizati<strong>on</strong>s perresp<strong>on</strong>dent. The authors c<strong>on</strong>cluded in their original report that the results,‘force us to seriously address the possibility <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> both theory failureand program failure in this field’ (Rosenbaum, Lewis and Grant 1985,p.170).LOWMAN (1983) investigated the effectiveness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhoodwatch in a residential district <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Vancouver, Canada. The evaluati<strong>on</strong>was based <strong>on</strong> a comparis<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> crime rates in an experimental area (theneighbourhood watch pilot project area) and three c<strong>on</strong>trol areas inwhich neighbourhood watch had not been implemented. The results22

showed that the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> burglaries decreased by 33 per cent in theexperimental area with no change in the comparis<strong>on</strong> areas. The authorc<strong>on</strong>cluded that the reducti<strong>on</strong> in the experimental area ‘may be indicative<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a deterrent effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the program’ (p.295).MATTHEWS AND TRICKEY (1994) c<strong>on</strong>ducted an evaluati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> aneighbourhood watch scheme in the New Parks area <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Leicester in theUK. Police-recorded crime data were used to determine changes in crimerates in the experimental area in the 12 m<strong>on</strong>ths before and after thelaunch <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the scheme. Comparable data were obtained for seven nearbyc<strong>on</strong>trol areas. The results showed that the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> burglaries decreasedin the experimental area and increased in the c<strong>on</strong>trol area.However, in the following year the rate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> burglary increased. The authorsexplained that this reducti<strong>on</strong> in burglary was ‘welcome’ butsomewhat ‘shortlived’ (p 67).In a sec<strong>on</strong>d evaluati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood watch in Leicester, MATT-HEWS AND TRICKEY (1994) evaluated the effectiveness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a neighbourhoodwatch scheme <strong>on</strong> the Eyres M<strong>on</strong>sell housing estate. Police datawere used to examine changes in the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> burglaries in the yearbefore the launch <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the scheme and in the year following implementati<strong>on</strong>.Data were also collected for four other housing estates in thearea close to the Eyres M<strong>on</strong>sell estate. Over the study period, the number<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> burglaries <strong>on</strong> the Eyres M<strong>on</strong>sell estate increased by 24 per cent.The number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> burglaries <strong>on</strong> the Saffr<strong>on</strong> Lane estate (the estate with themost similar pretest burglary rate) also increased over the study period,but the increase was approximately half that <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the experimental area(12 per cent). The authors c<strong>on</strong>cluded that the outcome <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the project asa whole was encouraging, although ‘not particularly remarkable’ (p.50).However, the rapid increase in the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> burglaries in 1994 was ‘acause <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>siderable c<strong>on</strong>cern’ (p.50).RESEARCH AND FORECASTS INCORPORATED (1983) c<strong>on</strong>ducted in aUS study an evaluati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood watch in a residential area <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>Detroit, Michigan. The study used police data to compare changes incrime rates in 155-block experimental area (Crary-St Mary’s) withchanges in a matched c<strong>on</strong>trol area four miles away. In both neighbourhoods,crime rates for the 12 m<strong>on</strong>th period before and after implementati<strong>on</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighbourhood watch were examined. The results showed thatburglary rates decreased by a substantially greater amount in the experimentalarea than in the c<strong>on</strong>trol area (48 per cent compared with 4per cent). The authors explained that reported crime statistics showed,‘a substantial reducti<strong>on</strong> in Crary-St Mary’s that is not matched by thestatistics for the c<strong>on</strong>trol neighbourhood’ (p.34).TILLEY AND WEBB (1994) present findings from 11 evaluati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>individual burglary reducti<strong>on</strong> schemes implemented as part <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the SaferCities Program in the UK. Three <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the 11 evaluati<strong>on</strong>s (in Birmingham-Primrose estate, Rochdale-Belfield estate and Rochdale-Back O’Th’Mossestate) met the eligibility criteria for inclusi<strong>on</strong> in this review. Each23