Goal Attainment Scaling: An Efficient and Effective Approach to ...

Goal Attainment Scaling: An Efficient and Effective Approach to ...

Goal Attainment Scaling: An Efficient and Effective Approach to ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

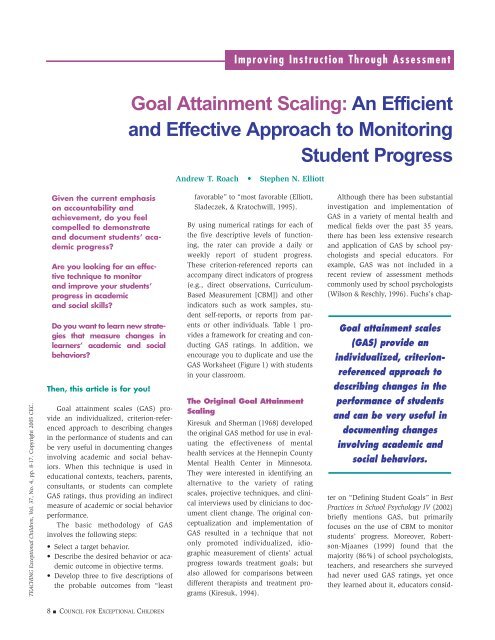

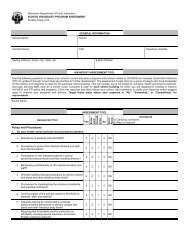

Figure 1. Template for Developing <strong>Goal</strong> <strong>Attainment</strong> Scales<strong>Goal</strong> <strong>Attainment</strong> Scale WorksheetStudent:Date of Birth:Today's Date: Grade: Gender: ❑ Male ❑ FemaleTeacher:School:Target Behavior(s):<strong>Goal</strong> <strong>Attainment</strong> Scale With Descriptive Criteria for Moni<strong>to</strong>ring Academic or Social Behavior Change+2+10-1-2Graph of Academic or Social Behavior ProgressNote. From Academic Competence Evaluation Scales, by J. C. DiPerna <strong>and</strong> S. N. Elliott, 2000, San <strong>An</strong><strong>to</strong>nio, TX: ThePsychological Corporation. Copyright 2000 by The Psychological Corporation. Adapted with permission.ments <strong>to</strong> solving the assessmentpuzzle. (p.13)By contributing additional <strong>and</strong> potentiallyunique information regarding students’academic needs <strong>and</strong> progress,GAS ratings represent an important“piece of the assessment puzzle.”<strong>An</strong> Alternate <strong>Approach</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Goal</strong><strong>Attainment</strong> <strong>Scaling</strong> for Use inEducational SettingsDrs. Thomas Kra<strong>to</strong>chwill <strong>and</strong> StephenElliott used a modified version of GASas part of a U.S. Department ofEducation research project entitled “<strong>An</strong>Experimental <strong>An</strong>alysis of Teacher/Parent Mediated Interventions forPreschoolers with Behavioral Problems.”Robertson-Mjannes (1999) outlinedthe differences betweenKra<strong>to</strong>chwill <strong>and</strong> Elliott’s modified GAS<strong>and</strong> the original approach developed byKiresuk <strong>and</strong> Sherman. Beyond its utilityas a follow-up measure of clinician orprogram effectiveness, Kra<strong>to</strong>chwill <strong>and</strong>Elliott conceptualized GAS as a forma-10 ■ COUNCIL FOR EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN

Case Examples From Current ResearchThe following cases were gathered as part of an investigation of the utility of the Academic Competence Evaluation Scales(ACES; DiPerna, & Elliott, 2000) <strong>and</strong> Academic Intervention Moni<strong>to</strong>ring System (AIMS; Elliott et al., 2001) for developing <strong>and</strong>moni<strong>to</strong>ring prereferral interventions in elementary school settings. To protect the confidentiality of the participants, we havechanged any identifying information about the cases.Case #1: JacobJacob is an 8-year-old boy who is in second grade at RedHawk Elementary School. Jacob was originally referred <strong>to</strong>the student assistance team as a kindergartner due <strong>to</strong> concernsabout his ability <strong>to</strong> remember <strong>and</strong> retaining basic conceptsskills. As a kindergartner, Jacob was referred by histeacher <strong>to</strong> the student assistance team—a small group ofgeneral <strong>and</strong> special education teachers, support staff, <strong>and</strong>administra<strong>to</strong>rs—for help in addressing her concerns abouthis ability <strong>to</strong> remember <strong>and</strong> retain basis concepts <strong>and</strong> skills.The results of a psychoeducational evaluation, conductedwhen Jacob was a first grader, indicated he had averageintelligence <strong>and</strong> academic skills in all areas. After consultationbetween his parents <strong>and</strong> school staff, it was decidedJacob should repeat first grade, <strong>and</strong> he was referred <strong>to</strong> aphysician for an ADHD evaluation.Early in second grade, Jacob’s teacher referred him <strong>to</strong> thestudent assistance team because of concerns with attention<strong>and</strong> academic performance, particularly in the area of reading<strong>and</strong> language arts. His teacher reported having used avariety of strategies <strong>to</strong> improve his performance includingusing preferential seating, modified materials <strong>and</strong> assignments,<strong>and</strong> pretesting/teaching important concepts. A considerationof work samples <strong>and</strong> a teacher-completed ACESrating scale resulted in the identification of the following targetbehavior: To increase Jacob’s ability <strong>to</strong> read secondgradevocabulary (i.e., sight words).Jacob’s initial performance in reading second-gradewords was at a level of less than 50% accuracy.Interventions included guided practice of text <strong>and</strong> sight wordreading, frequent checks of Jacob’s independent work, <strong>and</strong>moni<strong>to</strong>ring his progress through informal assessments witha goal of achieving at least 80% accuracy in the targetbehavior. Jacob’s teacher <strong>and</strong> members of the student assistanceteam collaborated <strong>to</strong> construct a GAS rating scale (seeFigure 2) for moni<strong>to</strong>ring Jacob’s progress in reading gradeleveltext.Data on Jacob’s progress <strong>to</strong>ward the target behavior wasgathered periodically (via teacher-completed GAS rating) forapproximately 4 weeks. Examination of the GAS ratingsdemonstrated improvements on the target behavior on 40%of the assessment dates. Subsequent consultation withJacob’s teacher indicated that he had made moderate overallprogress in reading during the assessment period <strong>and</strong> thatadditional practice opportunities <strong>and</strong> frequent informalassessments appeared <strong>to</strong> be more successful interventionpractices than moni<strong>to</strong>ring his independent work.Case #2: Wil<strong>to</strong>nWil<strong>to</strong>n is a 9-year-old boy who is in fourth grade at GreenMeadows Elementary School. Prior <strong>to</strong> this year, Wil<strong>to</strong>n hadnever been referred <strong>to</strong> the student assistance team.Wil<strong>to</strong>n’sthird-grade teacher referred him <strong>to</strong> the student assistanceteam because of her concerns about his reading <strong>and</strong> writingskills, which were both at least one grade below gradelevel. His teacher reported having used a variety of strategies<strong>to</strong> improve his performance such as reducing thelength of assignments, peer tu<strong>to</strong>ring, one-on-one tu<strong>to</strong>ringoutside of his reading group, <strong>and</strong> giving him extended time<strong>to</strong> complete his written work. A consideration of work samples<strong>and</strong> a teacher-completed ACES rating scale resulted inthe identification of the following target behavior: Toincrease Wil<strong>to</strong>n’s ability <strong>to</strong> identify the main idea of a s<strong>to</strong>rypassage.At the beginning of progress moni<strong>to</strong>ring, Wil<strong>to</strong>n couldidentify the main idea from a grade-level passage approximately60% of the time. Interventions included reducingthe reading level of texts, working with a lower readinggroup, allowing Wil<strong>to</strong>n <strong>to</strong> take home reading materials, <strong>and</strong>moni<strong>to</strong>ring his progress through informal assessments witha goal of achieving at least 90% accuracy in the targetbehavior. Wil<strong>to</strong>n’s teacher <strong>and</strong> members of the studentassistance team collaborated <strong>to</strong> construct a GAS rating scale(see Figure 3) for moni<strong>to</strong>ring Wil<strong>to</strong>n’s progress in readinggrade-level text.Data on Wil<strong>to</strong>n’s progress <strong>to</strong>wards the target behaviorwas gathered periodically (via teacher-completed GAS rating)for approximately 6 weeks. Examination of the GASratings demonstrated improvements on the target behavioron 10% of the assessment dates with no overall improvementin the target behavior. Subsequent consultation withthe classroom teacher indicated that the recommendedinterventions had been seen as acceptable <strong>and</strong> were implementedwith integrity, <strong>and</strong> also that Wil<strong>to</strong>n’s overall readingperformance had not improved during the assessmentperiod. In light of the assessment results suggesting resistance<strong>to</strong> intervention, the student assistance team referredWil<strong>to</strong>n for additional evaluation with “confidence that testingmay be indicated.”TEACHING EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN ■ MAR/APR 2005 ■ 11

Figure 2. <strong>Goal</strong> <strong>Attainment</strong> Scale Ratings for the Case of Jacob<strong>Goal</strong> <strong>Attainment</strong> Scale WorksheetStudent: Jacob Jones Date of Birth: 8-17-1984Today's Date: 10-19-02 Grade: 2nd Gender: X Male ❑ FemaleTeacher: Ms. Smith School: Red Hawk ElementaryTarget Behavior(s):Jacob will improve his accuracy in reading 2nd grade vocabulary words.<strong>Goal</strong> <strong>Attainment</strong> Scale with Descriptive Criteria for Moni<strong>to</strong>ring Academic Change+2 Jacob reads 2nd grade vocabulary with greater than 75% accuracy.+1 Jacob reads 2nd grade vocabulary with 56%-75% accuracy.0 Jacob reads 2nd grade vocabulary with 45%-55% accuracy.-1 Jacob reads 2nd grade vocabulary with 30%-44% accuracy.-2 Jacob reads 2nd grade vocabulary with less than 30% accuracy.Graph of Academic ProgressNote. From Academic Competence Evaluation Scales, by J. C. DiPerna <strong>and</strong> S. N. Elliott, 2000, San <strong>An</strong><strong>to</strong>nio, TX: ThePsychological Corporation. Copyright 2000 by The Psychological Corporation. Adapted with permission.tive assessment that could be repeatedperiodically <strong>to</strong> moni<strong>to</strong>r students’ academicor behavior progress.Using GAS as a repeated measure ofstudents’ progress required changes inthe original scaled descriptions developedby Kiresuk <strong>and</strong> Sherman.Although Kra<strong>to</strong>chwill <strong>and</strong> Elliott maintainedthe 5-point scale, the modifiedGAS included initial assessments <strong>to</strong>establish a baseline, which was subsequentlyassigned a score of “0.” Thus,the new scale levels ranged from thebest possible outcome (+2) <strong>to</strong> theworst possible outcome (-2). In addition,the modified GAS allowed for ratingsof both over- <strong>and</strong> underattainmen<strong>to</strong>f behavioral or academic objectives(Kra<strong>to</strong>chwill, Elliott, & Rot<strong>to</strong>, 1995).12 ■ COUNCIL FOR EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN

Figure 3. <strong>Goal</strong> <strong>Attainment</strong> Scale Ratings for the Case of Wil<strong>to</strong>n<strong>Goal</strong> <strong>Attainment</strong> Scale WorksheetStudent: Wil<strong>to</strong>n Phillips Date of Birth: 9-15-1983Today's Date: 10-20-02 Grade: 4th Gender: X Male ❑ FemaleTeacher: Ms. Powers School: Green Meadows ElementaryTarget Behavior(s):Wil<strong>to</strong>n will identify the main idea of a s<strong>to</strong>ry passage 90% of the time.<strong>Goal</strong> <strong>Attainment</strong> Scale with Descriptive Criteria for Moni<strong>to</strong>ring Academic Change+2 Wil<strong>to</strong>n correctly identifies main idea 90% <strong>to</strong> 100% of the time.+1 Wil<strong>to</strong>n correctly identifies main idea 80% <strong>to</strong> 89% of the time.0 Wil<strong>to</strong>n correctly identifies main idea 60% <strong>to</strong> 79% of the time.-1 Wil<strong>to</strong>n correctly identifies main idea 40% <strong>to</strong> 59% of the time.-2 Wil<strong>to</strong>n correctly identifies main idea 0% <strong>to</strong> 39% of the time.Graph of Academic ProgressNote. From Academic Competence Evaluation Scales, by J. C. DiPerna <strong>and</strong> S. N. Elliott, 2000, San <strong>An</strong><strong>to</strong>nio, TX: ThePsychological Corporation. Copyright 2000 by The Psychological Corporation. Adapted with permission.Previous Research onEducational <strong>and</strong> ClinicalApplications of GAS RatingsMaher’s (1982) evaluation of the <strong>Goal</strong>-Oriented <strong>Approach</strong> <strong>to</strong> Learning (GOAL)program indicated that students whocompleted GAS self-ratings achievedhigher goal attainment scores thanpeers who did not self-evaluate (58.0 <strong>to</strong>33.3), <strong>and</strong> were more likely <strong>to</strong> achievethe “Expected Outcome” level for theirgoals (88% <strong>to</strong> 0%). A follow-up investigation(Maher, 1983) demonstratedthat student <strong>and</strong> adult (i.e., guidancecounselor) GAS ratings of school adjustment<strong>and</strong> achievement “did not differsignificantly in terms of estimating goalattainment” (p. 533).Single-case studies utilizing GAS ratingshave been conducted with studentswith autism (Oren & Ogletree, 2000),traumatic brain injuries (Mitchell &Cusick, 1998), <strong>and</strong> conduct problems(Sladeczek, Elliott, Kra<strong>to</strong>chwill,TEACHING EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN ■ MAR/APR 2005 ■ 13

Figure 4. <strong>Goal</strong> <strong>Attainment</strong> Scale Ratings for the Case of Ellen<strong>Goal</strong> <strong>Attainment</strong> Scale WorksheetStudent: Ellen Jensen Date of Birth: April 6, 1990Today's Date: March 2, 2002 Grade: 6th Gender: ❑ Male X FemaleTeacher: Mrs. WilliamsSchool: Bailey ElementaryTarget Behavior(s):Ellen will demonstrate her ability <strong>to</strong> work cooperatively with a small group of classmates on a project withoutprompts or cues from an adult.<strong>Goal</strong> <strong>Attainment</strong> Scale with Descriptive Criteria for Moni<strong>to</strong>ring Behavior Change+2 When it is time <strong>to</strong> work with her project team, Ellen will almost always work cooperatively during the entireperiod without an adult prompting or cueing her <strong>to</strong> do so.+1 When it is time <strong>to</strong> work with her project team, Ellen will often work cooperatively during the entire period with onlyminimal prompting or cueing from an adult.0 When it is time <strong>to</strong> work with her project team, Ellen will sometimes work cooperativelyduring the entire period with periodic prompting or cueing from an adult.-1 When it is time <strong>to</strong> work with her project team, Ellen will almost never work cooperatively during the entireperiod despite frequently <strong>and</strong> strong prompting or cueing from an adult.-2 When it is time <strong>to</strong> work with her project team, Ellen never works cooperatively during the entire period regardlessof the amount of prompting <strong>and</strong> cueing from an adult.Graph of Progress on "Working Cooperatively"Note. From Academic Competence Evaluation Scales, by J. C. DiPerna <strong>and</strong> S. N. Elliott, 2000, San <strong>An</strong><strong>to</strong>nio, TX: ThePsychological Corporation. Copyright 2000 by The Psychological Corporation. Adapted with permission.Robertson-Mjaanes, & S<strong>to</strong>iber, 2001). Ineach case, consultants <strong>and</strong> consulteesreported GAS ratings helped <strong>to</strong> clarifyintervention goals <strong>and</strong> document studentprogress <strong>to</strong>wards those goals.In their study of family therapy efficacy,Santa-Barbara et al. (1977) reportedthat GAS was “the only clinical outcomemeasure that [was] consistentlyrelated <strong>to</strong> measures of intellectual functioning<strong>and</strong> academic achievemen<strong>to</strong>btained at follow-up ratings” (p. 54).Follow-up studies on family therapyclients conducted by Woodward et al.(1981) demonstrated that GAS ratings14 ■ COUNCIL FOR EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN

Table 2. Advantages <strong>and</strong> Disadvantages <strong>to</strong> Utilizing GAS Ratings <strong>to</strong> Moni<strong>to</strong>r Students’Academic GrowthAdvantages of GAS Ratings• Time efficient• Personalized/ individual assessment• Conceptually consistent with behavioral consultation• Requires minimal skills <strong>to</strong> collect data• Nonintrusive assessment method• Can be used as a self-assessment• Can be used by multiple informants across settings (e.g., home, school, community)• Can be used repeatedly <strong>to</strong> moni<strong>to</strong>r perceptions of intervention progress• Can be used <strong>to</strong> document perceptions of intervention outcomes• Inexpensive• Requires minimal skills <strong>to</strong> interpret dataDisadvantages of GAS Ratings• Limited published, empirical research on the school-based use of the method• Subjective summary of observations collected over time• Not norm-referenced• Guidelines for interpretation are determined by parties involved with the intervention, thus subject <strong>to</strong> bias• Global (i.e., less discrete) accounting of behaviorwere a more effective predic<strong>to</strong>r thanother outcome measures.GAS Ratings Are Time-<strong>Efficient</strong><strong>and</strong> User-FriendlyAlthough many researchers <strong>and</strong> policymakersconsider CBM the “gold st<strong>and</strong>ard”for assessing students’ academicperformance, practitioners often viewthese techniques as labor-intensive <strong>and</strong>unmanageable in general, <strong>and</strong> inappropriatefor students in middle school orhigher who are working on moreadvanced academic skills. For example,Fuchs <strong>and</strong> Elliott (1997) asserted CBMcan be “time-consuming for teachers orschool psychologists <strong>to</strong> collect, score,<strong>and</strong> analyze” (p. 228). Foegen, Espin,Allinder, <strong>and</strong> Markell (2001) suggestedthe following reasons for teacher’sreluctance <strong>to</strong> use CBM methods: (a)lack of time <strong>to</strong> implement <strong>and</strong> scoreCBM probes, (b) insufficient mastery ofthe skills needed <strong>to</strong> use CBM, <strong>and</strong> (c)practitioners’ beliefs about the validityof CBM.Acceptability research with school<strong>and</strong> mental health professionals suggeststhat GAS is perceived as highlyacceptable <strong>and</strong> useful in a variety of settings.Robertson-Mjaanes (1999) askedprofessionals (including teachers, n =36) <strong>to</strong> rate the ease of use <strong>and</strong> acceptabilityof GAS. The results indicate thatmost teachers (94%) endorsed GAS as“very feasible” or “feasible” <strong>to</strong> use withtheir students. Moreover, Robertson-Mjaanes found that 70% of the teachersbelieved that most professionals wouldfind GAS “easy” or “very easy” <strong>to</strong> usefor moni<strong>to</strong>ring intervention progress<strong>and</strong> outcomes.According <strong>to</strong> Carr (1979), specialeducation teachers who participated inan evaluation project described the timenecessary <strong>to</strong> construct an individualGAS as “worthwhile” <strong>and</strong> valuable forspecifying goals <strong>and</strong> facilitating theinclusion process. Cardillo (1994)reported that the existing research onthe implementation of GAS in mentalhealth settings suggests study participantsexperienced the GAS process as(a) “an unexpected, but beneficial learningexperience, with respect <strong>to</strong> both goalsetting <strong>and</strong> treatment planning”; <strong>and</strong>(b) one that lead “<strong>to</strong> an enhancedawareness of <strong>and</strong> respect for documentationrequirements” (p. 59). In an evaluationof two adult <strong>and</strong> family literacyprograms, Sherow (2000) identified thefollowing positive outcomes of usingGAS ratings:• Encouraged cooperative goal settingbetween staff <strong>and</strong> clients.• Facilitated the development of individualizedprograms for clients.• Clarified <strong>and</strong> communicating programgoals.TEACHING EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN ■ MAR/APR 2005 ■ 15

In addition <strong>to</strong> measuringacademic knowledge <strong>and</strong>skills, educa<strong>to</strong>rs may alsochoose <strong>to</strong> use GAS ratings<strong>to</strong> measure students’progress in socialbehaviors or academicenablers.• Provided both formative <strong>and</strong> summativeevaluations of program effectiveness.Table 2 provides a summary of theadvantages <strong>and</strong> disadvantages <strong>to</strong> usingGAS ratings <strong>to</strong> moni<strong>to</strong>r students’ academicgrowth.Final ThoughtsIn addition <strong>to</strong> measuring academicknowledge <strong>and</strong> skills, educa<strong>to</strong>rs mayalso choose <strong>to</strong> use GAS ratings <strong>to</strong> measurestudents’ progress in social behaviorsor academic enablers (i.e., “attitudes<strong>and</strong> behaviors that allow a student<strong>to</strong> participate in, <strong>and</strong> ultimatelybenefit from academic instruction”;DiPerna & Elliott, 2002, p. 294). A substantialbody of research exists whichdemonstrates the relationship betweenstudents’ social behavior <strong>and</strong> their academicperformance (DiPerna, Volpe, &Elliott, 2002; Malecki & Elliott, 2002;Wentzel, 1993). Figure 4 provides anexample of a complete GAS rating forEllen, a student with a social behaviorthat directly contributes <strong>to</strong> her educationalsuccess. Readers should note howthis GAS rating scale operationalizes agroup of behaviors (or “response class”)that pertains <strong>to</strong> the educational goal:successfully collaborating with classmateson a group project.According <strong>to</strong> Smith <strong>and</strong> Cardillo(1994), GAS ratings are especially suited“as a measure of one important aspec<strong>to</strong>f outcome: treatment- (or instruction-)induced change. If interest should be inthe change that has been produced during(an intervention)…GAS can be recommendedas a particularly sensitivemethod of measuring that change”(p. 272). The initial results from ourcase studies of prereferral interventionssuggest GAS ratings can provide efficient<strong>and</strong> accurate assessments of students’academic <strong>and</strong> behavior progress.Moreover, in our work designing academicinterventions in collaborationwith teachers, we have found GAS ratings<strong>to</strong> be a user-friendly <strong>and</strong> meaningfulway for conceptualizing <strong>and</strong> communicatingchange over the course of amultiweek intervention. GAS ratings arerelatively easy-<strong>to</strong>-use <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong>,making them particularly appropriate<strong>to</strong>ols for consulting <strong>and</strong> collaboratingwith general education teachers, paraprofessionals,<strong>and</strong> parents.GAS can be utilized <strong>to</strong> meet a varietyof assessment needs. As part of selfmoni<strong>to</strong>ringintervention, students themselvescan complete GAS ratings.Conversely, educa<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>and</strong> parents canuse GAS ratings <strong>to</strong> record their observations<strong>and</strong> perceptions of students’ academic<strong>and</strong> behavior progress. In comparison<strong>to</strong> direct observation or CBMprobes, teachers <strong>and</strong> paraprofessionalsmay find GAS ratings easier <strong>to</strong> collectwithin the complex ecologies of theirclassrooms. In addition, GAS promotesclearly operationalized interventiongoals <strong>and</strong> on-going (i.e., time-series)evaluation of student progress, makingit a potentially useful <strong>to</strong>ol for specialeduca<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>and</strong> school psychologistsworking within a responsiveness-<strong>to</strong>intervention(RTI) model of special educationidentification.ReferencesCardillo, J. E. (1994). <strong>Goal</strong> setting, follow-up,<strong>and</strong> goal moni<strong>to</strong>ring. In T. J. Kiresuk, A.Smith, & J. E. Cardillo (Eds.), <strong>Goal</strong><strong>Attainment</strong> <strong>Scaling</strong>: Application, Theory,<strong>and</strong> Measurement (pp. 39-60). Hillsdale,NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.Cardillo, J. E., & Smith, A. (1994).Psychometric issues. In T. J. Kiresuk, A.Smith, & J. E. Cardillo (Eds.), <strong>Goal</strong><strong>Attainment</strong> <strong>Scaling</strong>: Application, Theory,<strong>and</strong> Measurement (pp. 173-212). Hillsdale,NJ: LawrenceErlbaum.Carr, R. A. (1979). <strong>Goal</strong> attainment scaling asa useful <strong>to</strong>ol for evaluating progress inspecial education. Exceptional Children,46, 88-95.DiPerna, J. C., & Elliott, S. N. (2000).Academic Competence Evaluation Scales.San <strong>An</strong><strong>to</strong>nio, TX: The PsychologicalCorporation.DiPerna, J. C., & Elliott, S. N. (2002).Promoting academic enablers <strong>to</strong> improvestudent achievement: <strong>An</strong> introduction <strong>to</strong>the miniseries. School Psychology Review,31, 293-297.DiPerna, J. C., Volpe, R. J., & Elliott, S. N.(2002). A model of academic enablers <strong>and</strong>elementary reading/language artsachievement. School Psychology Review,31, 298-312.Elliott, S. N., DiPerna, J. C., & Shapiro, E. S.(2001). Academic Intervention Moni<strong>to</strong>ringSystem. San <strong>An</strong><strong>to</strong>nio, TX: ThePsychological Corporation.Elliott, S. N., Sladeczek, I., & Kra<strong>to</strong>chwill, T.R. (1995, August). <strong>Goal</strong> attainment scaling:Its use as a progress moni<strong>to</strong>ring <strong>and</strong>outcome effectiveness measure in behavioralconsultation. Paper presented at theannual convention of the AmericanPsychological Association, New York, NY.Foegen, A., Espin, C. A., Allinder, R. M., &Markell, M. A. (2001). Translatingresearch in<strong>to</strong> practice: Preservice teachers’beliefs about curriculum-based measurement.Journal of Special Education, 34,226-237.Fuchs, L. S. (2002). Best practices in definingstudent goals <strong>and</strong> outcomes. In A.Thomas, & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best Practicesin School Psychology-IV (pp. 539-546).Washing<strong>to</strong>n, DC: National Association ofSchool Psychologists.Fuchs, L. S., & Elliott, S. N. (1997). The utilityof curriculum-based measurement <strong>and</strong>performance assessment as alternatives <strong>to</strong>traditional intelligence <strong>and</strong> achievementtests. School Psychology Review, 26, 224-233.Kiresuk, T. J. (1994). His<strong>to</strong>rical perspective.In T. J. Kiresuk, A. Smith, & J. E. Cardillo(Eds.), <strong>Goal</strong> <strong>Attainment</strong> <strong>Scaling</strong>:Application, Theory, <strong>and</strong> Measurement(pp. 135-160). Hillsdale, NJ: LawrenceErlbaum.Kiresuk, T. J., & Sherman, R. E. (1968). <strong>Goal</strong>attainment scaling: A general method forevaluating community mental health programs.Community Mental Health Journal,4, 443-453.Kra<strong>to</strong>chwill, T. R., Elliott, S. N., & Rot<strong>to</strong>, P. C.(1995). Best practices in school-basedbehavioral consultation. In A. Thomas, &J. Grimes (Eds.), Best Practices in SchoolPsychology-III (pp. 519-538). Washing<strong>to</strong>n,DC: National Association of SchoolPsychologists.Maher, C. A. (1982). Learning disabled adolescentsin the regular classroom:Evaluation of a mainstreaming procedure.Learning Disability Quarterly, 5, 82-84.Maher, C. A. (1983). <strong>Goal</strong> attainment scaling:A method for evaluating special educationservices. Exceptional Children, 49, 529-536.16 ■ COUNCIL FOR EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN

Malecki, C. M., & Elliott, S. N. (2002).Children’s social behaviors as predic<strong>to</strong>rsof academic achievement: A longitudinalanalysis. School Psychology Quarterly, 17,1-23.Mitchell, T., & Cusick, A. (1998). Evaluationof a client-centered paediatric rehabilitationprogramme using goal attainmentscaling. Australian Occupational TherapyJournal, 45, 7-17.Oren, T., & Ogletree, B. T. (2000). Programevaluation in classrooms for students withautism: Student outcomes <strong>and</strong> programprocesses. Focus on Autism <strong>and</strong> OtherDevelopmental Disabilities, 15, 170-175.Robertson-Mjaanes, S. L. (1999). <strong>An</strong> evaluationof goal attainment scaling as an interventionmoni<strong>to</strong>ring <strong>and</strong> outcome evaluationtechnique. Unpublished doc<strong>to</strong>ral dissertation,University of Wisconsin-Madison.Santa-Barbara, J., Woodward, C. A., Levin, S.Streiner, D. L., Goodman, J. T., & Epstein,N. B. (1977). Interrelationships amongoutcome measures in the McMasterFamily Therapy Study. <strong>Goal</strong> <strong>Attainment</strong>Review, 3, 47-58.Shapiro, E. S., & Browder, J. L. (1990).Behavioral assessment: Applications forpersons with mental retardation. In J. L.Matson (Ed.), H<strong>and</strong>book of BehaviorModification with the Mentally Retarded(pp. 93 -120). New York: Plenum Press.Shapiro, E. S., & Kra<strong>to</strong>chwill, T. R. (2000).Conducting School-Based Assessments ofChild <strong>and</strong> Adolescent Behavior. New York:Guilford Press.Sherow, S. M. (2000). Adult <strong>and</strong> family literacyadaptations of goal attainment scaling.Adult Basic Education, 10, 30-38.Sladeczek, I. E., Elliott, S. N., Kra<strong>to</strong>chwill, T.R., Robertson-Mjaanes, S., & S<strong>to</strong>iber, K. C.(2001). Application of goal attainmentscaling <strong>to</strong> a conjoint behavioral consultationcase. Journal of Educational <strong>and</strong>Psychological Consultation, 12, 45-58.Smith, A., & Cardillo, J. E. (1994).Perspectives on validity. In T. J. Kiresuk,A. Smith, & J. E. Cardillo (Eds.). <strong>Goal</strong>attainment scaling: Applications, theory,<strong>and</strong> measurement. Hillsdale, NJ:Lawrence Erlbaum.Wilson, M. S., & Reschly, D. J. (1996).Assessment in school psychology training<strong>and</strong> practice. School Psychology Review,25, 9-23.Wentzel, K. R. (1993). Does being good makethe grade? Social behavior <strong>and</strong> academiccompetence in middle school.Journal ofEducational Psychology, 85, 357-364.Woodward, C. A., Santa-Barbara, J., Streiner,D. L., Goodman, J. T., Levin, S., &Epstein, N. B. (1981). Client, treatment,<strong>and</strong> therapist variables related <strong>to</strong> outcomein brief, systems-oriented family therapy.Family Process, 20, 189-197.Center for Assessment <strong>and</strong> InterventionResearch; <strong>and</strong> Stephen N. Elliott, DunnProfessor of Assessment, Department ofSpecial Education, Peabody College, V<strong>and</strong>erbiltUniversity, Nashville, Tennessee.Address all correspondence concerning thisarticle <strong>to</strong> <strong>An</strong>drew T. Roach, Center forAssessment <strong>and</strong> Intervention Research, 405Wyatt, 1930 South St., Nashville, TN 37203(e-mail: roach@v<strong>and</strong>erbilt.edu)TEACHING Exceptional Children, Vol. 37,No. 4, pp. 8-17.Copyright 2005 CEC.<strong>An</strong>drew T. Roach, Research Coordina<strong>to</strong>r,TEACHING EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN ■ MAR/APR 2005 ■ 17