Factors Affecting The Use of Student Financial Assistance by First ...

Factors Affecting The Use of Student Financial Assistance by First ...

Factors Affecting The Use of Student Financial Assistance by First ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Published in 2008 <strong>by</strong><strong>The</strong> Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation1000 Sherbrooke Street West, Suite 800, Montreal, QC, Canada H3A 3R2Toll Free: 1-877-786-3999Fax: (514) 985-5987Web: www.millenniumscholarships.caE-mail: millennium.foundation@bm-ms.orgNational Library <strong>of</strong> Canada Cataloguing in Publication<strong>Factors</strong> <strong>Affecting</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Student</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Assistance</strong> <strong>by</strong> <strong>First</strong> Nations YouthNumber XXIncludes bibliographical references.ISSN 1704-8435 Millennium Research Series (Online)Layout Design: Charlton + Company Design Group<strong>The</strong> opinions expressed in this research document are those <strong>of</strong> the authors and do not represent <strong>of</strong>ficialpolicies <strong>of</strong> the Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation and other agencies or organizations thatmay have provided support, financial or otherwise, for this project.

<strong>Factors</strong> <strong>Affecting</strong><strong>The</strong> <strong>Use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Student</strong><strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Assistance</strong><strong>by</strong> <strong>First</strong> Nations YouthPrepared for theCanada Millennium Scholarship FoundationPrepared <strong>by</strong>R.A. Malatest & Associates Ltd.and Dr. Blair StonechildJune 2008400–294 Albert St.1206–415 Yonge St.858 Pandora Ave.300–10621 100th Ave.Ottawa, ON K1P 6E6Toronto, ON M5B 2E7Victoria, BC V8W 1P4Edmonton, AB T5J 0B3Phone: (613) 688-1847Phone: (416) 644-0161Phone: (250) 384-2770Phone: (780) 448-9042Fax: (613) 288-1278Fax: (416) 644-0164Fax: (250) 384-2774Fax: (780) 448-9047www.malatest.com

Table <strong>of</strong> ContentsExecutive Summary ____________________________________________________vSection 1: Background to the Project_________________________________________1Background _________________________________________________________________________________________________1Purpose and Scope <strong>of</strong> the Study _______________________________________________________________________________2Section 2: Research Approach and Methodology ________________________________5Project Design _______________________________________________________________________________________________5Focus Groups and Key Informant Interviews ____________________________________________________________________5Research Considerations______________________________________________________________________________________7Report Structure _____________________________________________________________________________________________8Section 3: Aspirations for and Perspectives on Post-Secondary Education______________9Introduction ________________________________________________________________________________________________9Primary Influences __________________________________________________________________________________________10Plans and Expectations After High School _____________________________________________________________________11Reasons for Attending Post-Secondary Education_______________________________________________________________13Challenges to Attending Post-Secondary Education _____________________________________________________________13Summary <strong>of</strong> Major Findings__________________________________________________________________________________15Section 4: Awareness and <strong>Use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Student</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Assistance</strong> ____________________17Introduction _______________________________________________________________________________________________17Where <strong>First</strong> Nations Youth Are Finding Out about <strong>Student</strong> Funding Options _______________________________________18Awareness and <strong>Use</strong> <strong>of</strong> Band Funding __________________________________________________________________________19Awareness and <strong>Use</strong> <strong>of</strong> Other Types <strong>of</strong> <strong>Student</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Assistance</strong> _______________________________________________20Attitudes to Borrowing to Pay for Post-Secondary Education _____________________________________________________23Difference Between Awareness <strong>of</strong> <strong>Student</strong> Funding and <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Assistance</strong> among<strong>First</strong> Nations Compared to Non-<strong>First</strong> Nations Youth ____________________________________________________________25Key Informants’ Suggestions for Improved Delivery <strong>of</strong> Information _______________________________________________26Summary <strong>of</strong> Major Findings__________________________________________________________________________________27Section 5: Access to <strong>Student</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Assistance</strong>______________________________28Introduction _______________________________________________________________________________________________28Access to Band Funding _____________________________________________________________________________________28Access to <strong>Student</strong> Loans _____________________________________________________________________________________31Access to Scholarships or Bursaries ___________________________________________________________________________32Summary <strong>of</strong> Major Findings__________________________________________________________________________________33

FACTORS AFFECTING THE USE OF STUDENT FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE BY FIRST NATIONS YOUTHSection 6: Adequacy <strong>of</strong> <strong>Student</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Assistance</strong> ___________________________35Introduction _______________________________________________________________________________________________35Adequacy <strong>of</strong> Band Funding __________________________________________________________________________________35Adequacy <strong>of</strong> <strong>Student</strong> Loans __________________________________________________________________________________36Adequacy <strong>of</strong> Scholarships____________________________________________________________________________________37Transportation and Childcare Costs ___________________________________________________________________________37Summary <strong>of</strong> Major Findings__________________________________________________________________________________37Section 7: Final Observations and Recommendations ___________________________39Final Observations __________________________________________________________________________________________39Recommendations for Improving <strong>Student</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Assistance</strong> for <strong>First</strong> Nations Youth______________________________40Appendix A: Focus Group Locations and Types <strong>of</strong> Groups ________________________43

iAcknowledgementsThis report was prepared <strong>by</strong> R.A. Malatest &Associates Ltd., with the assistance <strong>of</strong> Dr. BlairStonechild, for the Canada Millennium ScholarshipFoundation. We would like to sincerely thank all <strong>of</strong>those who gave their valuable time to this project.We would especially like to thank those who assisted<strong>by</strong> participating in focus groups and interviews orwho helped to make them happen. We would alsolike to thank the Council <strong>of</strong> Ministers <strong>of</strong> Education,Canada (CMEC) for their financial contribution tothe preparation <strong>of</strong> the literature review and environmentalscan that preceded the fieldwork phase <strong>of</strong> thisproject. In addition, we appreciate the advice on thedevelopment <strong>of</strong> this project provided <strong>by</strong> <strong>of</strong>ficialsfrom CMEC and from the governments <strong>of</strong> Manitoba,Saskatchewan and British Columbia. Finally, wewould like to thank <strong>of</strong>ficials from Human Resourcesand Social Development Canada, and in particularBrian McDougall, for their encouragement and inputinto all phases <strong>of</strong> this research.British ColumbiaVancouver:Vancouver School BoardUniversity <strong>of</strong> British ColumbiaBroadway Youth Resource CentreVancouver Technical High SchoolVancouver Aboriginal FriendshipCentrePrince George:School District No. 57(Prince George)College <strong>of</strong> New CaledoniaPrince George NativeFriendship CentreUniversity <strong>of</strong> NorthernBritish ColumbiaKamloops:School District No. 73(Kamloops/Thompson)ManitobaWinnipeg:Winnipeg School DivisionCentre for Aboriginal HumanResource DevelopmentUniversity <strong>of</strong> ManitobaBrandon:Brandon School DivisionBrandon UniversityBrandon Aboriginal FriendshipCentre<strong>The</strong> Pas:Opaskwayak Cree Nation Employ -ment and Training CentreJoe A. Ross SchoolUniversity College <strong>of</strong> the NorthSaskatchewanSaskatoon:Saskatoon Public SchoolsSaskatchewan Indian Institute<strong>of</strong> TechnologySaskatoon Indian and MetisFriendship CentreUniversity <strong>of</strong> SaskatchewanRoyal West Campus/Mount Royal CollegiateRegina:Regina Public SchoolsMuscowpetung <strong>First</strong> NationScott Collegiate High School<strong>First</strong> Nations University <strong>of</strong> CanadaPrince Albert:Saskatchewan Institute <strong>of</strong> AppliedScience and TechnologyCarlton ComprehensiveHigh School

iiiAcronyms <strong>Use</strong>d in the ReportINACPSEPSSSPSFAIndian & Northern Affairs CanadaPost-Secondary EducationPost-Secondary <strong>Student</strong> Support Program (INAC PSE Funding Program)<strong>Student</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Assistance</strong>Glossary <strong>of</strong> TermsAboriginal personBand councilBill C-31<strong>First</strong> Nations peopleStatus <strong>First</strong>Nations personTribal councilA person <strong>of</strong> <strong>First</strong> Nations, Metis or Inuit ancestry 1A council governing a <strong>First</strong> Nations bandA 1985 amendment to the Indian Act that, among other provisions, allowed <strong>First</strong>Nations women who married non-<strong>First</strong> Nations men, and their children, to retaintheir legal Status as <strong>First</strong> Nations people.Indigenous people <strong>of</strong> Canada, not including Inuit or Metis peopleA <strong>First</strong> Nations person who is listed in the Indian Register <strong>of</strong> the Department<strong>of</strong> Indian & Northern Affairs Canada. Sometimes called a “Registered Indian.”An association <strong>of</strong> multiple <strong>First</strong> Nation bands, <strong>of</strong>ten formed around ethnic,linguistic or cultural bonds.1 As defined <strong>by</strong> Section 35 <strong>of</strong> the Constitution Act.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYviinities and families that do not have widespreadexperience with the PSE system, and there is <strong>of</strong>ten,as a result, a lower degree <strong>of</strong> familiarity with thebureaucratic systems <strong>of</strong> PSE funding. Furthermore,many <strong>First</strong> Nations youth return to their educationafter a period <strong>of</strong> working, looking after their familymembers, or other activities and may be somewhatdisconnected from the informational supportsavailable to those currently in the high school systemwho are moving directly to PSE.A second theme that emerged during the researchis that <strong>First</strong> Nations youth <strong>of</strong>ten do not explorealternative forms <strong>of</strong> SFA, as they believe that bandfunding will be available to them to finance their PSE.Many <strong>First</strong> Nations youth are reluctant to exploreother forms <strong>of</strong> PSE (e.g., provincial or Canada<strong>Student</strong> Loans, private lines <strong>of</strong> credit) becausethey prefer band funding (which is almost entirelygrant-based), as opposed to other funding mechanismsthat typically involve a repayable component.Often this is related to the recognition among <strong>First</strong>Nations youth that funding for education is a treatyobligation <strong>of</strong> the federal government.Thirdly, <strong>First</strong> Nations youth <strong>of</strong>ten do not feelmotivated to seek out information about PSEfunding. This is a result <strong>of</strong> a lack <strong>of</strong> confidence intheir ability to qualify for scholarships or loans, afeeling <strong>of</strong> disconnection from institutional/bureau -cratic systems and, importantly, a common concernabout incurring debt to pay for PSE.Overall, the results <strong>of</strong> the research suggest that incomparison with non-<strong>First</strong> Nations youth, <strong>First</strong>Nations youth have considerably less informationand motivation to explore the full range <strong>of</strong> SFAoptions available to support them in terms <strong>of</strong> attendinga PSE program.Awareness <strong>of</strong> scholarships, bursaries and otherforms <strong>of</strong> financing PSE increases once studentsbegin PSE studies.Notwithstanding that <strong>First</strong> Nations youth appear tohave considerably less knowledge or understanding<strong>of</strong> available SFA programs prior to enrolling in a PSEprogram, it appears that once they are enrolled in aPSE institution, many <strong>of</strong> them quickly gain a morecomprehensive understanding <strong>of</strong> available SFAprograms and services.A significant number <strong>of</strong> <strong>First</strong> Nations youthattending PSE noted that they only found out aboutmany forms <strong>of</strong> financial assistance after they beganto attend college or university. This was a result<strong>of</strong> becoming more aware <strong>of</strong> information sources,<strong>of</strong>ten including connecting with Aboriginal studentadvisers and other supports available at collegesand universities.<strong>First</strong> Nations youth generally appear to be wary<strong>of</strong> taking on debt to finance their PSE.<strong>The</strong>re is <strong>of</strong>ten an understandable aversion among<strong>First</strong> Nations youth to borrowing money to financetheir education. <strong>The</strong>re is a reticence among many topursue other forms <strong>of</strong> funding given that bandfunding may be available. Many youth do not appearto have planned for other funding in the eventthat band funding is not available to them or isinsufficient to cover all their expenses.In addition, <strong>First</strong> Nations youth <strong>of</strong>ten feel that theymay not be successful in college or university, whichmakes them wary <strong>of</strong> taking on debt for their PSE.Finally, as many <strong>First</strong> Nations students have youngfamilies and come from impoverished areas, manyconsider the risk that they will be unable to pay backtheir loans following their studies to be too high. Anumber <strong>of</strong> youth noted that they had seen friendsor family members struggling for years with unmanageabledebt as a result <strong>of</strong> student loans and didnot want the same fate for themselves.<strong>The</strong>re was also concern expressed <strong>by</strong> some youththat the amount <strong>of</strong> funding students receivedthrough their bands could be reduced for studentswho receive other forms <strong>of</strong> assistance or funding.In some cases, students even felt that they maybecome disqualified for band funding if they pursuedother forms <strong>of</strong> funding. Others may feel that bandfunding is the only major form <strong>of</strong> funding available to<strong>First</strong> Nations students.

viiiFACTORS AFFECTING THE USE OF STUDENT FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE BY FIRST NATIONS YOUTHBand funding is not available for all prospective<strong>First</strong> Nations PSE students.Given the high level <strong>of</strong> reliance on band funding,it would appear that current funding levels areinsufficient given the demand and accelerating costsassociated with PSE.Overall demand for band PSE funding exceedswhat is available in many <strong>First</strong> Nations, resulting insome students having to go on waiting lists or beingpassed over for funding. As a result <strong>of</strong> a limited pool<strong>of</strong> available funding, bands give preference to specifictypes <strong>of</strong> students, commonly including full-timestudents, students continuing with their studies,youth who have just completed high school or thosewho have previously not left their PSE program topursue other activities. Some types <strong>of</strong> studiesare rarely or never funded through band funding,including post-graduate and pr<strong>of</strong>essional studies.Given the limited availability <strong>of</strong> band funding,many <strong>First</strong> Nations students expressed frustrationwith the “lack <strong>of</strong> transparency” with respect to howsuch funds are allocated. Some youth felt that receipt<strong>of</strong> band funding <strong>of</strong>ten depended on relationshipswith band leadership, proximity to the band(those living on reserve were seen as having a higherprobability <strong>of</strong> being funded than those living <strong>of</strong>freserve) or other factors.<strong>The</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> role models or family history <strong>of</strong> SFAcould contribute to the limited understanding<strong>of</strong> student financial options.Many stakeholders noted that a lack <strong>of</strong> role modelscould account for reduced awareness <strong>of</strong> SFA optionsamong <strong>First</strong> Nations youth. In contrast to thenon-<strong>First</strong> Nations population, where a significantproportion <strong>of</strong> parents may have utilized a variety <strong>of</strong>grant or loan programs to finance their PSE, many<strong>First</strong> Nations youth and key informants notedthat they were not aware <strong>of</strong> individuals who hadutilized such programs to finance their education.In addition, the lower levels <strong>of</strong> PSE participationamong Canada’s <strong>First</strong> Nations population furtherreduced the likelihood <strong>of</strong> <strong>First</strong> Nations youthreceiving guidance from individuals who had“been through the system.”<strong>First</strong> Nations youth <strong>of</strong>ten have a limited understanding<strong>of</strong> the costs <strong>of</strong> PSE and the extent towhich band funding will cover these costs.Many <strong>First</strong> Nations youth have little knowledge <strong>of</strong> thecosts associated with PSE. This is <strong>of</strong>ten compounded<strong>by</strong> the inexperience <strong>of</strong> some youth from morerural, remote and northern areas in living in theurban centres where most colleges and universitiesare located.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYixMany <strong>First</strong> Nations youth believe that bandfunding alone will be sufficient to cover the costs <strong>of</strong>PSE. This is sometimes not the case—particularlyfor youth who are leaving their communities totake college or university programs in cities withcomparatively high costs <strong>of</strong> living or who havechildren to care for.<strong>The</strong>re appears to be insufficient support tocover transportation and childcare costs for<strong>First</strong> Nations PSE students.Many <strong>First</strong> Nations youth noted that the availableforms <strong>of</strong> student funding (including student loans)were <strong>of</strong>ten insufficient to cover the comparativelyhigh costs <strong>of</strong> transportation and childcare for <strong>First</strong>Nations PSE students, especially for those who haveto relocate from a <strong>First</strong> Nations community to pursuePSE. Many <strong>First</strong> Nations college or universitystudents have more than one child, and many travellong distances to attend PSE.<strong>The</strong>re is perceived to be a comparative lack <strong>of</strong>funding options available to pursue upgradingand trades training.Many key informants noted that there is a lack <strong>of</strong>funding options available for those <strong>First</strong> Nationsyouth who want to pursue upgrading and tradestraining. While some youth can receive financialassistance for trades training through AboriginalHuman Resource Development Agreement funding,there is a disproportionately low number <strong>of</strong> fundingoptions available for these types <strong>of</strong> training.Key informants provided suggestions on waysto improve the PSE funding systems for <strong>First</strong>Nations youth.<strong>The</strong> research confirms the need to enhance awarenessamong <strong>First</strong> Nations youth <strong>of</strong> the full range <strong>of</strong> SFAprograms. Related suggestions provided <strong>by</strong> keyinformants included:• more human resources and better training forstaff dedicated to educating <strong>First</strong> Nations youthabout PSE funding in <strong>First</strong> Nations communitiesand in colleges and universities;• courses on career and education planning needto be a consistent part <strong>of</strong> the secondary schoolcurriculum;• more funding opportunities need to be providedto <strong>First</strong> Nations students;• role models need to be involved in outreach; and• more funding and support are needed to increaseInternet access in <strong>First</strong> Nations communities.

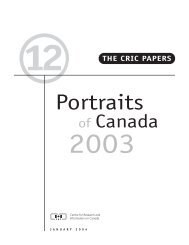

1Section 1Background to the ProjectBackgroundDespite improvements in the last two decades, thepost-secondary education (PSE) attainment rates<strong>of</strong> Aboriginal people remain below those <strong>of</strong> theoverall Canadian population. Census data do show asteady increase since the 1980s in participation andcompletion <strong>of</strong> PSE among Aboriginal people.Nevertheless, they are still significantly less likely toattain a university degree than a college or tradesdiploma, and there remains a significant gapbetween Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal PSE attainmentrates overall. 2 According to the 2006 census,35 percent <strong>of</strong> the population with Aboriginal ancestryhad attained post-secondary credentials (eithertrades, college or university), compared to 51 percent<strong>of</strong> the general Canadian population. Furthermore,as illustrated in Figure 1, only eight percent <strong>of</strong> NorthAmerican Indians had completed a university degree,compared to 23 percent <strong>of</strong> the non-Aboriginalpopulation.<strong>The</strong>se lower education rates are particularly significantgiven the demographics <strong>of</strong> the Aboriginalpopulation. In the 2006 Census, the number <strong>of</strong>people who identified themselves as Aboriginalsurpassed the one million mark—at 1,172,790.Approximately 53 percent <strong>of</strong> Aboriginal peopleidentified themselves as being “Registered Indian.”According to the 2006 Census, nearly one-half(48 percent) <strong>of</strong> Registered Indians lived on reserves.<strong>The</strong> Aboriginal population is younger than theoverall Canadian population and is expected toexceed 1.4 million people <strong>by</strong> 2017. 3 Again accordingto the 2006 Census, 48 percent <strong>of</strong> the populationFigure 1: Proportion <strong>of</strong> Populations Aged 15 Years or Older with Completed Certificate, Diploma or Degree, 200660%50%40%30%32%35%51%All PSEUniversitydiploma,degree20%23%10%0%North AmericanIndian8% 9%All AboriginalPeoplesNon-AboriginalCanadiansSource: Statistics Canada, 2006 Census (20 percent sample data)2 For a more detailed discussion <strong>of</strong> these issues, see: Canadian Council on Learning (2007), “State <strong>of</strong> Learning in Canada: No Time for Complacency,”Report on Learning in Canada 2007, Ottawa: Canadian Council on Learning, (http://www.ccl-cca.ca/NR/rdonlyres/5ECAA2E9-D5E4-43B9-94E4-84D6D31BC5BC/0/NewSOLR_Report.pdf).3 Statistics Canada (2005), Projections <strong>of</strong> the Aboriginal Populations, Canada, Provinces and Territories: 2001 to 2017, Ottawa: Industry Canada,Statistics Canada Catalogue No. 19 91-547-XWE.

2FACTORS AFFECTING THE USE OF STUDENT FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE BY FIRST NATIONS YOUTHstating their identity as Aboriginal were under the age<strong>of</strong> 25, compared to only 31 percent <strong>of</strong> the overallCanadian population. 4 As these young Aboriginalpeople age and represent a growing proportion <strong>of</strong> theCanadian population, their educational success hasimportant implications for the country overall.<strong>The</strong>re are significant benefits for Aboriginalpeople and Aboriginal communities from higherrates <strong>of</strong> PSE attainment. Recent research found thatAboriginal people who held a university degreehad employment rates comparable to their non-Aboriginal counterparts. 5 Recent data from StatisticsCanada reveal that Aboriginal women who hadcompleted a university education had a higheremployment rates than non-Aboriginal universitygraduates. 6 In addition, PSE is associated withbenefits related to earnings, health and well being, aswell as positive levels <strong>of</strong> civic and communityengagement. 7In a recent survey commissioned <strong>by</strong> the Foun -dation, financial barriers were perceived <strong>by</strong> <strong>First</strong>Nations youth not planning to go on to college oruniversity as the most significant factor holding themback from PSE. 8 Furthermore, when <strong>First</strong> Nationsyouth who were planning to go on to PSE were askedif anything might change their plans, 48 percent saidthat it would be a lack <strong>of</strong> money. <strong>The</strong> seriousness <strong>of</strong>these financial barriers reflects the lower incomelevels <strong>of</strong> Aboriginal people compared to the overallCanadian population. However, low income levelsmay not be the sole reason for non-participation inPSE, and a key objective <strong>of</strong> this research projectwas to explore <strong>First</strong> Nations youth perspectiveswith respect to student financial assistance (SFA)programs which should help address the financialbarriers they face.Purpose and Scope<strong>of</strong> the StudyGiven the impact <strong>of</strong> financial barriers in terms <strong>of</strong>participation in PSE, it is important to understandthe ways that <strong>First</strong> Nations youth are accessingfinancial assistance for PSE and the factors affectingthis access and use. <strong>The</strong> goal <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Factors</strong> <strong>Affecting</strong>the <strong>Use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Student</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Assistance</strong> <strong>by</strong> <strong>First</strong>Nations Youth project was to examine the factorsaffecting <strong>First</strong> Nations youth awareness and use <strong>of</strong>post-secondary financial assistance and to examinehow these factors differ from those <strong>of</strong> non-<strong>First</strong>Nations youth. That is, given that there are particularfinancial barriers for <strong>First</strong> Nations youth in terms <strong>of</strong>PSE, what are the reasons that <strong>First</strong> Nations youthchoose to access or not access financial assistance?Are these reasons different from those <strong>of</strong> non-<strong>First</strong>Nations students?Specifically, the objectives <strong>of</strong> this project wereto provide information to help understand thefollowing areas:• <strong>First</strong> Nations youth use <strong>of</strong> post-secondary SFAprograms;• attitudes <strong>of</strong> <strong>First</strong> Nations youth toward SFA ingeneral;• potential barriers in the financial assistanceapplication process; and• whether existing levels <strong>of</strong> financial assistanceare sufficient to encourage successful completion<strong>of</strong> PSE.4 Statistics Canada (2006), “Aboriginal identity population <strong>by</strong> age groups, median age and sex, 2006 counts, for Canada, provinces and territories—20 percent sample data.” (http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census06/data/highlights/Aboriginal/pages/Page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo=PR&Code=01&Table=1&Data=Count&Sex=1&Age=1&StartRec=1&Sort=2&Display=Page)5 See, for example: Jeremy Hull (2005), Aboriginal PSE and Labour Market Outcomes, Canada, 2001, Winnipeg: Prologica Research Inc.6 Berger, Joseph (2008), Why Access Matters Revisited: A Review <strong>of</strong> the Latest Research, Montreal: Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation.7 Canadian Council on Learning (2007), Canadian PSE—A Positive Record, An Uncertain Future (http://www.ccl-cca.ca/CCL/Reports/Post-secondaryEducation/).8 Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation (2005), Changing Course: Improving Aboriginal Access to Post-Secondary Education in Canada:Millennium Research Note #2, Montreal: Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation.

SECTION 1: BACKGROUND TO THE PROJECT 3Consultations were limited to youth and keyinformants in three provinces: Manitoba, Saskatche -wan and British Columbia. Focusing on specific areas<strong>of</strong> Canada allowed the project to examine in a morecomprehensive manner the issues arising in thesethree provinces, all <strong>of</strong> which include comparativelylarge proportions <strong>of</strong> <strong>First</strong> Nations youth.<strong>The</strong> project was undertaken <strong>by</strong> R.A. Malatest &Associates Ltd. (“the Consultant”), in conjunctionwith Dr. Blair Stonechild, in order to support themandate <strong>of</strong> the Canada Millennium ScholarshipFoundation (“the Foundation”). <strong>The</strong> Foundation is anindependent organization that was created <strong>by</strong> an act<strong>of</strong> Parliament in 1998 to provide financial assistancein the form <strong>of</strong> bursaries and scholarships to collegeand university undergraduate students. Its mandateis to improve access to PSE so that Canadianscan acquire the knowledge and skills needed toparticipate in a changing economy and society.<strong>The</strong> Foundation distributes $335 million annually inneed-based bursaries accessed <strong>by</strong> students throughprovincial SFA programs, as well as $12 millionannually in merit scholarships. It also operates aresearch program to study barriers to PSE and theimpact <strong>of</strong> policies designed to alleviate them, andit brings education stakeholders together to helpidentify ways to improve overall access to PSE.

5Section 2Research Approachand MethodologyProject Design<strong>The</strong> <strong>Factors</strong> <strong>Affecting</strong> the <strong>Use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Student</strong> <strong>Financial</strong><strong>Assistance</strong> <strong>by</strong> <strong>First</strong> Nations Youth project wasdesigned to explore its research questions throughmultiple activities and sources.Primary research activities undertaken for theproject included the completion <strong>of</strong> 40 focus groupsand 41 key informant interviews. In addition, theproject included the review and analysis <strong>of</strong> secondarysources in order to:• complete an environmental scan comprising acomprehensive review <strong>of</strong> available sources <strong>of</strong>PSE funding for Aboriginal students (including<strong>First</strong> Nations, Métis and Inuit students) from allgovernmental, non-governmental, private andcorporate sources; and• complete a document and literature review <strong>of</strong>factors relevant to Aboriginal access to fundingsources for PSE.This report presents the findings and conclusions<strong>of</strong> the focus groups and key informant interviewsundertaken for the project.Focus Groups and KeyInformant InterviewsFocus Groups<strong>The</strong> project collected the perspectives <strong>of</strong> youththrough a series <strong>of</strong> 40 focus groups in Manitoba,Saskatchewan and British Columbia from November2007 to February 2008. For the purposes <strong>of</strong> the study,youth included those up to the age <strong>of</strong> 30 years <strong>of</strong> age.Focus groups were undertaken with:• Secondary school students—<strong>First</strong> Nations andgeneral population (i.e., non-<strong>First</strong> Nations) youthwho were in their final years <strong>of</strong> high school.Generally students were in Grade 12;• Youth in PSE—<strong>First</strong> Nations and general populationyouth who were enrolled in university or collegestudies; and• Youth not in PSE—<strong>First</strong> Nations and generalpopulation youth who had left or completedhigh school and who were not currently registeredin PSE; this group included youth enrolled at anadult high school or pursuing a high schoolgeneral equivalency diploma.Focus groups ranged in size from two to 17 partici -pants, with an average <strong>of</strong> nine participants per group.Table 1 details the locations and respondent groupsfor the focus groups.Participants in focus groups <strong>of</strong> <strong>First</strong> Nations PSEstudents were grouped <strong>by</strong> different ages: separatefocus groups were undertaken with those whowere under 25 years <strong>of</strong> age and with those who were

6FACTORS AFFECTING THE USE OF STUDENT FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE BY FIRST NATIONS YOUTHTable 1: Focus GroupsSecondary Post- ProvincialProvince Group Type School <strong>Student</strong>s Secondary Not in PSE TotalBritish Columbia<strong>First</strong> Nations 2 4 4General Population 1 1 113SaskatchewanManitoba<strong>First</strong> Nations 3 5 4General Population 1 1 1<strong>First</strong> Nations 2 4 413General Population – 1 1Total 9 16 15 4015between 25 and 30 years <strong>of</strong> age. Overall, 10 focusgroups were undertaken with PSE students whowere under 25 years old, and three with older PSEstudents.Focus group discussions were structured tocapture information related to the following topics:• What are the reasons that youth are accessingor not accessing financial assistance?• Are <strong>First</strong> Nations youth more “debt averse” thanother students?• Does the Indian & Northern Affairs Canada(INAC) PSE program model discourage studentsfrom applying for other forms <strong>of</strong> financial assistance(loans, scholarships, bursaries)?• Are participants aware <strong>of</strong> the availability <strong>of</strong> SFAand how to access it (e.g., do <strong>First</strong> Nations youth<strong>of</strong>ten think they are not eligible for assistancewhen they in fact are)?• What types <strong>of</strong> financial aid products are participantspursuing (e.g., private loans, band funding,Foundation bursaries)?• Do participants find that the processes <strong>of</strong>applying for PSE financial assistance are“user-friendly”?• Are the eligibility criteria for obtaining financialassistance fair and equitable? Are the applicationassessment procedures fair?• Does the current array <strong>of</strong> loans and other financialaid mechanisms meet participants’ needs?• Are there ways in which funding agencies hinderstudent access to post-secondary studies?Focus groups were organized and participantsidentified through multiple methods. Many organizationshelped to publicize the focus groups, andsome provided venues for holding the groups.<strong>Assistance</strong> was provided through the following types<strong>of</strong> organizations:• school boards and high schools;• Friendship Centres;• Aboriginal student associations and NativeCentres at universities and colleges;• community centres and recreation centres; and• <strong>First</strong> Nation Band <strong>of</strong>fices.Further information on the specific locations andtypes <strong>of</strong> groups is provided in Appendix A <strong>of</strong> this report.Key Informant InterviewsBetween November 2007 and March 2008, 41 keyinformant interviews were completed in-person or<strong>by</strong> telephone with a variety <strong>of</strong> key informants.In British Columbia, 18 interviews were conducted;in Manitoba, 15 interviews were conducted; and inSaskatchewan, eight interviews were conducted. Key

SECTION 2: RESEARCH APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY 7Table 2: Number <strong>of</strong> Key Informant Interviews <strong>by</strong> OccupationOccupation# <strong>of</strong> Interviews Completed<strong>First</strong> Nations support worker or counsellor at a college or university 8Director <strong>of</strong> Aboriginal <strong>Student</strong> Services at a college or university 7Government <strong>of</strong>ficial 6<strong>First</strong> Nations Education Coordinator/Director <strong>of</strong> Education <strong>of</strong> a <strong>First</strong> Nation 5Representative from a <strong>First</strong> Nations organization 3Public school board representative 3Other stakeholders from high schools and PSE institutions 9Total 41informants represented a wide range <strong>of</strong> occupationsrelated to Aboriginal post-secondary education. Asample <strong>of</strong> over 100 key stakeholders and serviceproviders working in these occupations was developed,from which 41 interviews were completed.Potential key informants were mailed an invitationletter prior to contact <strong>by</strong> the Consultant. Keyinformant interviews were undertaken usingsemi-structured key informant guides.Literature Review<strong>The</strong> research team conducted a literature review<strong>of</strong> issues pertaining to Aboriginal youth access t<strong>of</strong>inancial assistance for PSE. Drawing from existingresearch, the team addressed interdependenciesbetween cultural, social and psychological barriers aswell as access to financial assistance. <strong>The</strong> literaturereview also provides detailed information aboutexisting research gaps in the area. While theliterature review was largely completed prior tocommencement <strong>of</strong> primary data collection, it was a“living document” and was updated and revisedthroughout the course <strong>of</strong> the project as new sources<strong>of</strong> literature and documentation were identified.Environmental Scanand Inuit students) for PSE. 9 Information for each <strong>of</strong>these sources has been provided to the Foundationand the the Council <strong>of</strong> Ministers <strong>of</strong> Education,Canada (CMEC), which contributed financial tothe preparation <strong>of</strong> the literature review and theenvironmental scan, in an inventory in Micros<strong>of</strong>tOffice Excel.Research Considerations<strong>First</strong> Nations youth in Manitoba, Saskatchewan andBritish Columbia represent a wide variety <strong>of</strong>geographic areas, backgrounds and socio-economiccontexts. <strong>The</strong> perspectives and experiences <strong>of</strong> <strong>First</strong>Nations youth can also vary according to theirmembership or level <strong>of</strong> connection with a <strong>First</strong>Nation, including whether or not they are or havebeen living on-reserve.<strong>The</strong> extent to which the views <strong>of</strong> the youthconsulted for this study are representative <strong>of</strong> all<strong>First</strong> Nations youth in these three provinces is notknown. Interview and focus group findings representthe views <strong>of</strong> individual focus group and key informantparticipants only and should not be seen asnecessarily representative <strong>of</strong> the views <strong>of</strong> all <strong>First</strong>Nations youth or stakeholders.<strong>The</strong> Consultant conducted a comprehensive review<strong>of</strong> all sources <strong>of</strong> financial assistance currentlytargeted to Aboriginal students (<strong>First</strong> Nations, Metis9 This review excluded sources <strong>of</strong> funding available to all Canadians and funding specific to individual post-secondary institutions.

8FACTORS AFFECTING THE USE OF STUDENT FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE BY FIRST NATIONS YOUTHReport Structure<strong>The</strong> report has been structured to examine therelevant issues related to four specific areas. Whilethese areas provide a useful structure to organize thefindings, it should be noted that there are manyinstances in which these areas can overlap and affecteach other.Section 3 examines findings related to youthaspirations and overall perspectives <strong>of</strong> PSE.Section 4 discusses findings related to the level<strong>of</strong> awareness and understanding among youth <strong>of</strong>student funding options.Section 5 considers findings related to the accessthat <strong>First</strong> Nations youth have to the available forms<strong>of</strong> funding.Section 6 presents findings related to the perceivedadequacy <strong>of</strong> SFA for <strong>First</strong> Nations youth.Final observations are presented in Section 7.Figure 2: Categories <strong>of</strong> Research FindingsAwarenessAspirationsAdequacyAccess

9Section 3Aspirations for andPerspectives on PSEWhat are the plans that <strong>First</strong> Nations youth have for PSE? Who and what are influencing these plans?IntroductionPrevious research suggests that the PSE aspirations<strong>of</strong> young Aboriginal people are similar to those <strong>of</strong>Canadian youth overall. According to a survey <strong>of</strong> <strong>First</strong>Nations people living on reserves, 70 percent <strong>of</strong>respondents between the ages <strong>of</strong> 16 and 24 hopeto complete some form <strong>of</strong> PSE. 10 <strong>The</strong>se findingsmirror those <strong>of</strong> other Canadians within the same agegroup. 11 <strong>The</strong>re is evidence to suggest that both<strong>First</strong> Nations and non-<strong>First</strong> Nations parents alsoshare similar aspirations for their children in terms <strong>of</strong>PSE attainment. 12<strong>The</strong> literature suggests that planning for PSE isstrengthened through a family tradition <strong>of</strong> attendingPSE. 13 Findings from the Survey <strong>of</strong> Secondary School<strong>Student</strong>s confirm the influence <strong>of</strong> parents on youtheducational aspirations. This survey <strong>of</strong> general populationyouth found that 60 percent <strong>of</strong> students saidthat their parents had a very strong impact on theirdecisions after high school. 14 This is <strong>of</strong> particularrelevance for <strong>First</strong> Nations people, where the tradition<strong>of</strong> attending PSE is <strong>of</strong>ten less established.Other studies on the impact <strong>of</strong> rurality on postsecondaryaspirations suggest that because <strong>of</strong>differences in rural and non-rural labour markets,students from rural communities have limitedexposure to a wide range <strong>of</strong> educational and careeropportunities. A pair <strong>of</strong> Statistics Canada studies onthe role <strong>of</strong> distance in affecting access to highereducation reveals the extent to which rural youth faceunique barriers to post-secondary education. <strong>The</strong>author <strong>of</strong> the studies, Marc Frenette, suggests thatdistance may affect access in three ways: elevatedfinancial costs related to moving and living awayfrom home; emotional costs associated with leaving anetwork <strong>of</strong> family and friends; and a lower awareness<strong>of</strong> the benefits <strong>of</strong> higher education due to the lack <strong>of</strong>geographic exposure to a post-secondary institution. 15In a study <strong>of</strong> the effects <strong>of</strong> community <strong>of</strong> residence onthe post-secondary aspirations <strong>of</strong> high school seniorsfrom five different demographic settings in southernOntario, O’Neill demonstrated that students fromrural areas and villages had the lowest levels <strong>of</strong>post-secondary educational aspirations <strong>of</strong> all geo -graphic groups. 16 This may have particular relevancyfor residents <strong>of</strong> <strong>First</strong> Nations communities in remoteand rural areas <strong>of</strong> the country.<strong>The</strong> sections below provide more detailed findingsrelated to aspirations and perspectives on PSE basedon the focus groups and key informant interviewsconducted for this study.10 Ekos Research Associates Inc. (2002), Fall 2002 Survey <strong>of</strong> <strong>First</strong> Nations People Living on Reserve, Toronto: Ekos Research Associates Inc.11 Statistics Canada (2000), At a Crossroads: <strong>First</strong> Results for the 18- to 20-Year-Old Cohort <strong>of</strong> the Youth in Transition Survey, Ottawa: HumanResources Development Canada, Statistics Canada Catalogue number 81-591-XIE.12 R.A. Malatest & Associates Ltd. (2007), <strong>The</strong> Class <strong>of</strong> 2003—High School Follow-Up Survey, Montreal: Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation.13 Paul Anisef, Robert Sweet and Peggy Ng (2004), “<strong>Financial</strong> Planning for Post-Secondary Education in Canada: A Comparison <strong>of</strong> Savings and SavingsInstruments Employed across Aspiration Groups,” NASFAA Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Student</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> Aid, 34(2), 19-32.14 Prairie Research Associates (2005), Survey <strong>of</strong> Secondary School <strong>Student</strong>s, Montreal: Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation, 57-8.15 Statistics Canada (2004), “Distance as a Post-Secondary Access Issue,” Education Matters, Ottawa: Industry Canada, Statistics Canada Cataloguenumber 81-004-XIE.16 O’Neill, G.P. (1981), “Post-Secondary Aspirations <strong>of</strong> High School Seniors from Different Socio-Demographic Contexts,” <strong>The</strong> Canadian Journal <strong>of</strong>Higher Education, 11(2), 49-66.

10FACTORS AFFECTING THE USE OF STUDENT FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE BY FIRST NATIONS YOUTHPrimary InfluencesYouth were asked to share their perspectives onwhich individuals in their lives they feel have had thebiggest influence on their decisions and plans afterhigh school, including plans related to PSE. Influenceagents identified in the research included familymembers, children, teachers, counsellors, friendsand self-motivation.FamilyAcross all focus groups, <strong>First</strong> Nations youth mostfrequently cited family members as having had thebiggest influences on their future plans. Specifically,in order <strong>of</strong> frequency, the following types <strong>of</strong> familymembers were listed as influences: parents, siblings,aunts and uncles, and grandparents. Family memberswere said to be influencing youth in both positive andnegative ways.Many youth discussed the positive influence <strong>of</strong>family on their decision-making as it relates toeducation. Several said that family members hadverbally encouraged them to finish high school andattend college or university. This encouragementcame from both family members who had attendedPSE and those who had not. Youth were motivated toattend PSE because they would be the first in theirfamilies to do so or because they had positive rolemodels in their family who had attended themselves.One youth, for example, noted that her grandparentshad encouraged her to be the first member <strong>of</strong> theirfamily to finish high school. Another noted that hergrandmother “was one <strong>of</strong> the first Aboriginal womento graduate from UBC [University <strong>of</strong> BritishColumbia] in her program.”Several youth said that their family situationhad encouraged them to create a better life forthemselves. As one youth attending PSE said: “I haveseen my parents struggle and live in poverty, and Ididn’t want that for myself.” Others noted that theyfelt they had a responsibility to help their family andthat college or university would allow them to do so.One PSE student, for example, stated: “[I] wanted tobe a leader in my family.”Conversely, a number <strong>of</strong> youth noted that familyhad actually had a negative influence on theirdecision-making. In particular, a few youth notedthat they came from families with substance abuse oralcohol problems. Others said that their familymembers had introduced them to “partying” andother related negative influences, which had delayedtheir studies and led them “<strong>of</strong>f track” for years.ChildrenMany <strong>First</strong> Nations youth noted that their ownchildren played an important role in shaping theireducation plans. While having young children was<strong>of</strong>ten said to make completing upgrading or pursuinghigher education more difficult, many youth feltthat it also served as further motivation to do so. Inparticular, several youth noted that they wanted to begood role models for their children. One youth said:“I don’t want my daughter growing up, being 13 andlooking at me and saying, ‘Hey mom, you don’t haveyour Grade 12—why do I need mine?’”Other youth noted that <strong>by</strong> completing college oruniversity, they would be better able to provide futurefinancial security for their children. One individual,for example, said that through completing furthereducation she would be better able to obtain ahigher-paying “9 to 5” job and, as a result, wouldbe able to see her child more than if she worked ashift-work position.Teachers, Counsellors, Academic AdvisersA number <strong>of</strong> high school students spoke <strong>of</strong> thepositive influence teachers or guidance counsellorshad played in their decision to pursue PSE. Manystudents said that there had been “lots <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>fers tohelp” and that teachers and counsellors hadapproached them about potential scholarshipopportunities. At one high school in particular,several students spoke enthusiastically about ane-mail program set up <strong>by</strong> their high school guidancecounsellor to inform graduating students <strong>of</strong>upcoming scholarship deadlines, career fairs andPSE workshops.

SECTION 3: ASPIRATIONS FOR AND PERSPECTIVES ON PSE 11Some youth said that while the influence <strong>of</strong> teachersor guidance counsellors had been positive, it was notenough to increase their levels <strong>of</strong> motivation orpreparation. In particular, some youth noted thatwhile their teacher or guidance counsellors providedencouragement, the information they provided didnot give sufficient direction in terms <strong>of</strong> how theywould proceed with going on to college or university.For example, one youth recalled:“It would have been better if the informationwas broken down into how [the system <strong>of</strong> studentfunding] actually works and how you applyfor it. I had no idea how [applying for studentfunding] worked.”Where high school academic advisers are moreintegrated into the curriculum and school programming(and, consequently, develop relationships withstudents through spending considerable time withthem), they appeared to play a more significant rolein student decision-making processes.For example, youth who were enrolled in an adulthigh school mentioned that there were helpfulcounsellors and advisers at their school who hadhelped them to plan for further education. Severalyouth enrolled in adult high schools specificallycredited advisers with going out <strong>of</strong> their way toprovide students with information and assistance onhow to apply for and fund post-secondary students.<strong>The</strong>se sentiments were also shared <strong>by</strong> high schoolstudents at an Aboriginal-focused high school inWinnipeg that had an employment adviser whoworked closely with graduating students.FriendsYouth sometimes said that friends had played arole in influencing their decisions and plans. Someyouth mentioned that seeing friends go on to PSEmade them feel that they could do the same. Inthe words <strong>of</strong> one PSE student youth: “I saw that[the application process] wasn’t that tough and theyhelped me through it.”In contrast, several youth who had not gone on toPSE stated that their friends had had a largely negativeinfluence on their plans after high school. Manymentioned that they had fallen in with the “wrongcrowd” <strong>of</strong> friends. Perhaps not surprisingly, youthwho had not gone on to PSE were more likely to seetheir friends as negative influences than those whohad attended college or university after high school.Self-MotivationWhile many noted that other individuals had had aninfluence on their plans and decisions, <strong>First</strong> Nationsyouth <strong>of</strong>ten stated that self-motivation was theprimary driver behind their decisions and plansrelated to attending PSE. As previously discussed, thisis related to the desire <strong>of</strong> some youth to be rolemodels for family and others. Examples <strong>of</strong> relatedcomments from youth currently attending PSEincluded:“I really wanted to show the people back homeon my reserve that people can change.”“People don’t expect much from you becauseyou’re a native woman. I wanted to show peoplethat I am not a stereotype.”Comparing the responses from youth in the non-<strong>First</strong> Nations focus groups, <strong>First</strong> Nations youth weremore likely to say that self-motivation was a primaryinfluence on their decisions around PSE.Plans and ExpectationsAfter High SchoolPlans <strong>of</strong> High School <strong>Student</strong>sAlmost all <strong>First</strong> Nations high school students inthe focus groups expressed a desire or interest inattending PSE in the future. That said, while studentsoverwhelmingly stated that they planned to go on tocollege or university, youth were split between thosewho felt that they would immediately try to attendPSE after high school and those who felt that theywould take time <strong>of</strong>f from school before going on toPSE. For example, one high school student noted that“I don’t want to rush into something that I mightnot like,” while, in contrast, another student said:“A whole year <strong>of</strong> not doing anything, <strong>of</strong> not learninganything? I want to keep my mind fresh.”

12FACTORS AFFECTING THE USE OF STUDENT FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE BY FIRST NATIONS YOUTHMany <strong>First</strong> Nations youth who were attendingPSE at the time <strong>of</strong> the focus groups did not enrollimmediately after high school. Unlike the moretraditional or conventional pathways <strong>of</strong> non-<strong>First</strong>Nations PSE students, <strong>First</strong> Nations youth <strong>of</strong>tennoted that there had been a period between theirinitial attendance in high school and beginningcollege or university. Often this period had includedcaring for family members or children, working, oraddressing different personal issues.Plans and Expectations <strong>of</strong> Those WhoHad Not Pursued PSEYouth who had not pursued PSE discussed whatfactors had influenced their decisions and plans forafter high school. Many <strong>of</strong> these youth had droppedout <strong>of</strong> high school and <strong>of</strong>ten lacked the academicqualifications required to pursue college or universityeducations.Many youth with child dependants felt that schoolwas incompatible with being the parent <strong>of</strong> a youngchild. Lack <strong>of</strong> affordable or accessible childcare wasidentified as a major barrier for these youth. As oneyouth explained:“If you’re going to school you need to find someoneto watch your child, but you can’t really afforddaycare. That’s a really big problem for me.That’s why I am not in school right now.”Some youth who had not gone on to PSE notedsevere personal barriers, including substance abuseand involvement in criminal activities. Others felt thatPSE was not an option worth pursuing at that time.Non-<strong>First</strong> Nations youth who did not go on toPSE were more likely to say that they wanted toconcentrate on working and making money afterhigh school. In comparison, <strong>First</strong> Nations youth weremore likely to note that other personal issues hadbeen greater influences in their decision to notpursue PSE.Impact <strong>of</strong> System <strong>of</strong> Funding onYouth AspirationsKey informants were asked to what extent they feltthe current system and array <strong>of</strong> student funding hasan impact on high school students’ aspirations andexpectations <strong>of</strong> attending PSE.On the whole, opinions were mixed. Many keyinformants noted that they felt that the currentsystem was having a positive impact, as it generallyprovides the financial means for <strong>First</strong> Nations youthto attend PSE. In contrast, a similar number <strong>of</strong> keyinformants noted that the current system is verycomplicated, which may have a negative impact onyouth plans and expectations. In particular, becausefunding supports such as scholarships and loans mayseem unattainable, PSE itself may <strong>of</strong>ten seem out <strong>of</strong>reach to <strong>First</strong> Nations youth. As one <strong>First</strong> Nationeducation coordinator said, the funding system“is designed in a way that is neither helpful norencouraging.”Other key informants noted that financial considerationsaround PSE are not the major factorsimpacting the plans and hopes <strong>of</strong> youth. Significant,and <strong>of</strong>ten systemic, social barriers were sometimesfelt to be larger obstacles to PSE than financialconsiderations alone. For example, since manyyouth need academic upgrading before they canpursue PSE, the funding options related to college oruniversity are <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>of</strong> secondary (or less immediate)importance. Academic and financial barriers can also<strong>of</strong>ten be linked, since youth <strong>of</strong>ten require upgradingto be eligible for financial assistance and are lesslikely to get funding from outside sources.Some key informants also noted that training forskilled trades is under-funded in the current fundingsystem, which may have a negative impact onthose youth who do not see themselves in academicPSE programs but may be inclined to pursue anapprenticeship or other type <strong>of</strong> trades program.

SECTION 3: ASPIRATIONS FOR AND PERSPECTIVES ON PSE 13Reasons for AttendingPost-Secondary EducationYouth were asked the reasons why they had decidedto attend PSE or intended to do so in future.Creating a better life for themselves and theirfamily was the most frequently cited reason for goingon to PSE. This theme was <strong>of</strong>ten coupled with thedesire to be a role model for younger siblings,members <strong>of</strong> their community or their own children.In particular, the theme <strong>of</strong> giving back to thecommunity through the achievement <strong>of</strong> personalgoals was common. In the words <strong>of</strong> one PSE student:“I wanted to be able to do something for my community,and getting an education was a way to do that.”Often reasons were explicitly linked to employmentgoals. As one <strong>First</strong> Nations PSE student noted:“Four years working in dead-end, minimum-wagejobs motivated me to go to university [and] make abetter life for myself.”<strong>First</strong> Nations youth were less likely than non-<strong>First</strong>Nations youth to mention strictly employment orfinancial reasons, however. Many <strong>First</strong> Nations youthexpressed a strong desire to return to their communitiesonce they had finished their education in order toimprove the social and financial wellbeing <strong>of</strong> othercommunity members. Overall, stated goals forattending PSE related to community and familywere more common among <strong>First</strong> Nations youth thannon-<strong>First</strong> Nations youth. <strong>First</strong> Nations youth <strong>of</strong>tendemonstrated a strong motivation to use their educationto work to improve their community and family,whereas non-<strong>First</strong> Nations youth were more likelyto express individualistic goals.Challenges to AttendingPost-Secondary EducationMany current or potential challenges were notedamong youth who were planning to attend PSE orwere already in college or university. <strong>Financial</strong>reasons alone were not those that were mostfrequently discussed—financial challenges weregenerally felt to compound other challenges. Many <strong>of</strong>these challenges were related to:• <strong>The</strong> need to care for children or other familymembers.• <strong>The</strong> difficulties and stress <strong>of</strong> having to relocateoutside <strong>of</strong> their home community to take PSE.• Loneliness and a feeling <strong>of</strong> isolation, sometimesexacerbated <strong>by</strong> experiences <strong>of</strong> racism or “cultureshock” when leaving their communities. As one<strong>First</strong> Nation PSE student noted, it “was verydemoralizing—sometimes you’re the only <strong>First</strong>Nations person in the class.” This sense <strong>of</strong>isolation is <strong>of</strong>ten more acute for those studentsfrom northern and remote communities whocannot easily travel home during the school year.• Insufficient academic preparation, including nothaving the prerequisite courses or sufficient highschool grades. Some youth felt that their schoolinghad not provided them with sufficient readingor writing skills. For at least one student, thiswas related to English not being the primarylanguage in her family. Others spoke <strong>of</strong> perceiveddeficiencies in the education system or theeducation they received.Several youth attending PSE noted that arrangingchildcare and housing was a significant challenge.This included not just finding the resources to pay fordaycare and housing but also being able to find andsecure appropriate options (including supplyingreferences, etc.). This was also an issue raised <strong>by</strong> a

14FACTORS AFFECTING THE USE OF STUDENT FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE BY FIRST NATIONS YOUTHnumber <strong>of</strong> key informants. For example, on the issue<strong>of</strong> childcare, one key informant in Manitoba noted:“Funding for daycare is a huge issue for <strong>First</strong>Nations students. <strong>The</strong>re are not a lot <strong>of</strong> vacancies[at most daycares], and there is not enough moneygiven out to help pay for childcare.”Some youth who had not taken any college oruniversity courses mentioned that it was the result<strong>of</strong> not receiving band funding or believing that theywould not receive it if they did apply. <strong>The</strong>se youthdid not appear to have pursued other forms <strong>of</strong> SFA.Key informants also noted significant challengesfor youth that included family responsibilities, insufficientacademic preparation and other issues.Some key informants noted that low expectationsfrom teachers limited youth aspirations for PSE.In the words <strong>of</strong> one participant:“Often <strong>First</strong> Nations youth are marginalized<strong>by</strong> persistent low expectations from teachers.This creates a systemic barrier for students,diminishing their potential and hindering theirability to see opportunities for advancement.”Expectations <strong>of</strong> Costs <strong>of</strong> PSEFocus group discussions <strong>of</strong>ten demonstrated that thecosts <strong>of</strong> attending PSE are not well understood <strong>by</strong>high school students. Many high school studentslacked an understanding <strong>of</strong> tuition costs or the costs<strong>of</strong> books and living expenses.Many <strong>First</strong> Nations high school students appearedto believe that band funding would cover all <strong>of</strong> theirPSE-related expenses. As one PSE student explained:“I never really took the time to look into studentloans or scholarships. I thought that becauseband funding was my right the money wouldbe there for me…but it wasn’t like that.”Key informants also noted that <strong>of</strong>ten youth have alimited understanding <strong>of</strong> the costs <strong>of</strong> college anduniversity educations. For example, a Director <strong>of</strong>Enrolment Services at a post-secondary institutionnoted: “It doesn’t always occur to many <strong>First</strong> Nationsyouth that there is a cost associated with pursuingPSE or how high that cost is.”<strong>Financial</strong> Challenges <strong>of</strong> Current PSE <strong>Student</strong>s<strong>Financial</strong> challenges were a frequent concern amongthose who were enrolled in college or university.<strong>Financial</strong> challenges were frequently related to thecosts <strong>of</strong> caring or supporting children, the high (andincreasing) costs <strong>of</strong> rent and food, and other costs<strong>of</strong> transportation to and from (<strong>of</strong>ten distant) <strong>First</strong>Nations communities. <strong>The</strong> cost <strong>of</strong> housing was raisedin all focus groups, with students in Saskatchewanand British Columbia appearing to be especiallyconcerned about the costs and difficulties <strong>of</strong> findingappropriate housing in the province’s cities. <strong>The</strong> challenge<strong>of</strong> covering these costs was, in many cases,being faced without the support <strong>of</strong> family and friendsthat students had benefited from in their homecommunities. Many students mentioned that theyregularly struggled to meet their basic needs.Often these challenges forced PSE students tojuggle multiple priorities, including—in manycases—family, work and school. One <strong>First</strong> NationsPSE student wondered: ”How do I find a balance? Ineed to work so that I can afford to go to school, butat the same time I should be spending that timestudying…” Many students were raising children,which added to their financial challenges.Some students mentioned that they had had toreceive help from family members or resort to usingcredit cards to finance their day-to-day living. Oneyouth mentioned receiving help from a familymember who had moved to the city to help look afterthe student’s children during class time. Others notedthat they used food banks. While some studentsseemed resigned to some <strong>of</strong> the sacrifices they hadmade to pay for their PSE, others noted that theyhad had to make what they felt were unreasonablesacrifices. One student, for example, spoke abouthow she had had to send her children to live withdistant grandparents because she could not afford tolook after them while she was attending college.Some financial challenges were said to have beenthe result <strong>of</strong> administrative issues related to bandfunding. Many youth attending PSE mentioned thatthis had affected their studies at some point in time.Some youth spoke about receiving their bandfunding late in the registration process, for example,

SECTION 3: ASPIRATIONS FOR AND PERSPECTIVES ON PSE 15or not getting timely responses to questions abouttheir funding. Several key informants echoed thisconcern and pointed to inconsistencies in bandfunding. For example, one government <strong>of</strong>ficial inBritish Columbia noted:“<strong>The</strong>re is not a consistent level <strong>of</strong> expectation[for band funding]. <strong>The</strong> process <strong>of</strong> accessingfunds from your band can differ greatly fromone year to the next and from band to band.”Several students mentioned that they had takenlife skills or budgeting courses that had proven tobe useful in helping them to face their financialchallenges while in PSE.Barriers to Returning to PSEMany youth who had started but not completed PSEnoted that they faced financial barriers to returningto school. While finances were not generally givenas the primary or sole reason for leaving school, anumber <strong>of</strong> youth stated that a lack <strong>of</strong> financialresources was a significant barrier to returningto PSE.Several youth noted that it was more difficult to bechosen to receive band funding once an applicanthas already “stopped out” <strong>of</strong> school for a time. Somenoted that this was felt to be related to the fact thattheir <strong>First</strong> Nation may have seen them as a potentialdrop-out risk. Key informants echoed this sentiment:as one key informant in Saskatchewan noted, “thereare no second chances [with band funding]. If you failyour first time, you go to the bottom <strong>of</strong> the pile.”Other reasons for “stop-outs” included havingto look after children or dissatisfaction withthe program or with PSE generally. <strong>Financial</strong> reasonsappeared to be cited more <strong>of</strong>ten as a reason forleaving PSE <strong>by</strong> those youth who were lookingafter children.Summary <strong>of</strong> Major FindingsWhile the main theme <strong>of</strong> the focus group discussionswas financial issues, financial considerations were<strong>of</strong>ten shown to be linked to other areas.Overall, positive aspirations and perspectivessurrounding PSE were <strong>of</strong>ten shown to stem fromyouth wanting to be positive role models for theirfamily, children or other community members. Manyyouth enrolled in PSE or who had plans to attendPSE after high school noted that they would be thefirst in their family to attend college or university.Almost all <strong>First</strong> Nations high school students inthe focus groups expressed a desire or interest inattending PSE in the future. That said, many youthwho were attending PSE did not enroll immediatelyafter high school. Often the period or break prior toPSE included caring for family members or children,working, or “sorting out” personal issues.<strong>Financial</strong> challenges were a frequent concernamong those who were attending PSE as well as thoseseeking to return to school after a break or absence.<strong>Financial</strong> challenges (such as the high costs <strong>of</strong>childcare and housing costs) <strong>of</strong>ten compoundedpersonal challenges to attending PSE.

Section 4Awareness and <strong>Use</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Student</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Assistance</strong>What forms <strong>of</strong> funding do <strong>First</strong> Nations youth know about and use?IntroductionAccording to INAC data for 2004-05, over 22,000<strong>First</strong> Nations students received band funding to helpA review <strong>of</strong> the literature undertaken for this researchproject revealed that there are limited data availableon how <strong>First</strong> Nations students are paying for PSE orabout levels <strong>of</strong> awareness <strong>of</strong> different types <strong>of</strong> SFA.Research with secondary students suggests thatthe general population <strong>of</strong> Canadian youth know verylittle about SFA such as bursaries and scholarshipsbut are more familiar with credit cards and studentloans. 17 <strong>The</strong> study also found that secondary studentswere likely to use formal channels <strong>of</strong> accessinginformation on PSE and financial assistance, such asgovernment websites or speaking with representatives<strong>of</strong> post-secondary institutions. Moreover, onlytwo-thirds <strong>of</strong> high school seniors were willingto guess the tuition rate in their province, and apay for their college or university education throughthe Post-Secondary <strong>Student</strong> Support Program(PSSSP). 19 A 2001 survey <strong>of</strong> former British Columbiacollege, university-college and institute studentsdemonstrated that band funding is one <strong>of</strong> thelargest sources <strong>of</strong> financial assistance for <strong>First</strong>Nations students. According to the study, 35 percent<strong>of</strong> Aboriginal respondents selected “Indian BandFunding” as one <strong>of</strong> their top two sources <strong>of</strong> funding. 20In the British Columbia survey, Aboriginal respondentswere less likely than their non-Aboriginalcounterparts to cite personal savings, family supportand employment income as methods <strong>of</strong> payingfor PSE. Approximately 28 percent <strong>of</strong> Aboriginalrespondents claimed they had used governmentmajority <strong>of</strong> them overestimated <strong>by</strong> a factor <strong>of</strong> about student loans. 21 Moreover, the Canadian Collegetwo to one. Additional research confirms relativelylow levels <strong>of</strong> information about financing postsecondaryeducation among high school students<strong>Student</strong> Survey found that Aboriginal college studentswere somewhat less likely to receive student loansthan all students, but somewhat more likely toand their parents. Though 84% <strong>of</strong> parents reported receive grants. 22 A survey <strong>of</strong> students two yearstalking to their kids about post-secondary education,only 58% discussed financial issues a few times,36% discussed how they would fund post-secondaryafter they had completed high school found thatAboriginal youth were less able to rely on non-loansupport from family members than non-Aboriginaleducation and only 13% discussed governmentyouth. 23 1717 Prairie Research Associates (2005), Survey <strong>of</strong> Secondary School <strong>Student</strong>s, Montreal: Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation.18 Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation (2006), Closing the Access Gap: Does Information Matter? Millennium Research Note #3. Montreal.19 Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, Basic Departmental Data.20 British Columbia Ministry <strong>of</strong> Advanced Education, Outcomes Working Group and CEISS Research and IT Solutions (2002), 2001 B.C. College andInstitute Aboriginal Former <strong>Student</strong> Outcomes: Special Report on Aboriginal Former <strong>Student</strong>s from the 1995, 1997, 1999 and 2001 B.C. Collegeand Institute <strong>Student</strong> Outcomes Surveys.21 Ibid.22 Sean Junor and Alex Usher (2004), <strong>The</strong> Price <strong>of</strong> Knowledge 2004: Access and <strong>Student</strong> Finance in Canada, Montreal: Canada Millennium ScholarshipFoundation, 171-2.23 R.A Malatest & Associates Ltd. (2007), <strong>The</strong> Class <strong>of</strong> 2003: High School Follow-Up Survey. Montreal: Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation.

18FACTORS AFFECTING THE USE OF STUDENT FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE BY FIRST NATIONS YOUTHNeither the Canada <strong>Student</strong> Loans Program (atthe national level) nor the Foundation are able totrack the number <strong>of</strong> their student recipients who are<strong>First</strong> Nations. In Saskatchewan and Manitoba,millennium access bursaries are specifically allocatedto Aboriginal students in their first- or second-year <strong>of</strong>study. <strong>The</strong> Millennium Aboriginal Access Bursary inSaskatchewan provides approximately $2,000 in nonrepayablefinancial assistance to over 600 Aboriginalstudents each year. 24An environmental scan undertaken for this projectdemonstrated a wide range <strong>of</strong> scholarships availableto <strong>First</strong> Nations students. For example, the NationalAboriginal Achievement Foundation has disbursedover $23.5 million in scholarships to Aboriginalstudents since its inception; it awarded $2.8 millionto 934 recipients across Canada during the 2005-2006fiscal year. 25<strong>The</strong> literature has suggested that cultural attitudesabout government responsibility for PSE fundingmay affect the degree to which Aboriginal people areaware <strong>of</strong> or using student loans and other forms <strong>of</strong>student assistance. <strong>The</strong> Assembly <strong>of</strong> <strong>First</strong> Nationsasserts that PSE at all levels is a treaty right, whereasthe federal government sees the funding <strong>of</strong> <strong>First</strong>Nations and Inuit PSE as a social program for whichit need not be the only funding source. 26 In a survey<strong>of</strong> <strong>First</strong> Nations people undertaken for the Foundation,a majority (58 percent) said that governments havethe greatest responsibility for paying for PSE. 27<strong>The</strong> following section further explores <strong>First</strong>Nations awareness and use <strong>of</strong> SFA in the interviewsand focus groups undertaken for this project.Where <strong>First</strong> Nations YouthAre Finding Out about <strong>Student</strong>Funding OptionsBoth key informants and youth discussed how <strong>First</strong>Nations youth are finding out about SFA. <strong>The</strong> mostcommon methods are detailed below.Family and Friends: Among <strong>First</strong> Nations highschool and PSE students, word <strong>of</strong> mouth was themost common way <strong>of</strong> obtaining informationabout student funding. A number <strong>of</strong> youth said thatconversations with friends and family were theprimary way they obtained information about theirfunding options. Often, youth noted that they werecomfortable getting information from relatives orfriends who had themselves been to university orcollege. One PSE student explained, “I prefer to asksomebody who is already there: ‘How did you get towhere you are at, and how do I get there?’” Someyouth mentioned having family members whoworked at high schools or band <strong>of</strong>fices who theyfelt were well connected to the available informationon PSE funding options.Aboriginal <strong>Student</strong> Advisers: Most <strong>First</strong> Nationsyouth attending PSE knew about the Aboriginalstudent advisers at their college or university, andmany had visited an adviser to discuss financialissues. Nearly one-quarter <strong>of</strong> key informants alsonoted that Aboriginal student advisers were a source <strong>of</strong>information that <strong>First</strong> Nations youth were accessing.High School Teachers and Counsellors: Youthmentioned high school guidance counsellors orteachers far less commonly as sources <strong>of</strong> information.In contrast, key informants most commonly notedhigh school guidance counsellors and teachers as asource <strong>of</strong> information, and family and friends as thesecond most common source <strong>of</strong> information.Band Education Coordinators: Youth and keyinformants noted that band <strong>of</strong>fices and <strong>First</strong> Nations24 Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation website (2005), “New access bursary for Aboriginal post-secondary students”(www.millenniumscholarships.ca/images/PressReleases/saskatchewan-en.pdf/).25 National Aboriginal Achievement Foundation website (2007), “Education Program” (www.naaf.ca/html/education_program_e.html).26 Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (2005), Evaluation <strong>of</strong> the Post-Secondary Education Program, Ottawa: Indian and Northern Affairs Canada.27 Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation (2005), Changing Course: Improving Aboriginal Access to Post-Secondary Education in Canada:Millennium Research Note #2, Montreal: Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation.