Status Report, Vol. 35, No. 5, May 13, 2000 - Insurance Institute for ...

Status Report, Vol. 35, No. 5, May 13, 2000 - Insurance Institute for ...

Status Report, Vol. 35, No. 5, May 13, 2000 - Insurance Institute for ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

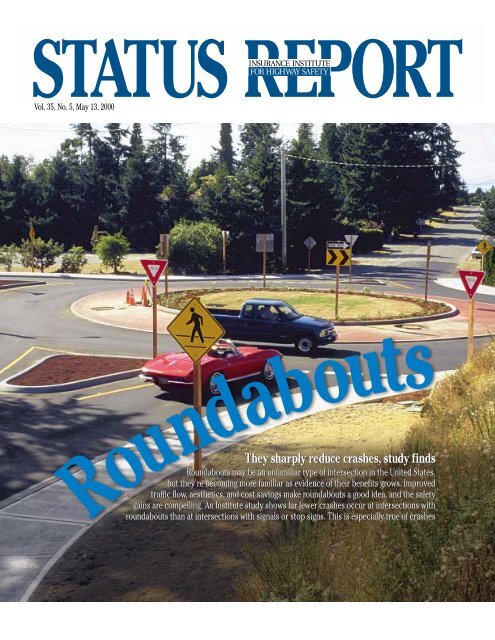

<strong>Vol</strong>. <strong>35</strong>, <strong>No</strong>. 5, <strong>May</strong> <strong>13</strong>, <strong>2000</strong>They sharply reduce crashes, study findsRoundabouts may be an unfamiliar type of intersection in the United States,but they’re becoming more familiar as evidence of their benefits grows. Improvedtraffic flow, aesthetics, and cost savings make roundabouts a good idea, and the safetygains are compelling. An <strong>Institute</strong> study shows far fewer crashes occur at intersections withroundabouts than at intersections with signals or stop signs. This is especially true of crashes

2 <strong>Status</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, <strong>Vol</strong>. <strong>35</strong>, <strong>No</strong>. 5, <strong>May</strong> <strong>13</strong>, <strong>2000</strong>resulting in occupant injuries. Researchersat Ryerson Polytechnic University, the <strong>Institute</strong>,and the University of Maine studiedcrashes and injuries at 24 intersections be<strong>for</strong>eand after construction of roundabouts.The study found a 39 percent overall decreasein crashes and a 76 percent decreasein injury-producing crashes. Collisions involvingfatal or incapacitating injuries fell asmuch as 90 percent.These findings are consistent with thosefrom other countries where roundaboutshave been used extensively <strong>for</strong> decades.They also are consistent with preliminarystudies of U.S. roundabouts.The safety benefits don’t come at the expenseof traffic flow. In fact, where roundaboutsreplace intersections with stop signsor traffic signals, delays in traffic can be reducedby as much as 75 percent.“Given the magnitude of these crash reductions,there’s no doubt that roundaboutsare an important countermeasure <strong>for</strong> manyintersection safety problems,” says <strong>Institute</strong>president Brian O’Neill. “Replacing signalsor stop signs with roundabouts will reducethe number of crashes and save lives whileat the same time improving traffic flow.”The recent study focuses on urban andrural intersections in Cali<strong>for</strong>nia, Colorado,Florida, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, SouthCarolina, and Vermont. The roundabouts replacedstop controls or traffic signals.Old idea improved: Rotary intersectionsaren’t new. They predate the automobile.In 1905, the first U.S. traffic circle, thenknown as a “gyratory,” was constructed inNew York City, and European countries builtthem in great numbers through the earlypart of this century.In its basic <strong>for</strong>m, a traffic circle consistsof a raised island at the center of an ordinaryright-angle intersection. The island,which directs cars counterclockwise, is intendedto reduce speeds, although this goalisn’t always achieved. Other configurationscan be more complex. They may involvesplit lanes and combinations of yield signs,stop signs, and traffic lights — all of whichcan be confusing to drivers trying to negotiatethem.The modern roundabout improves onsuch designs. This is an important distinction,because the older traffic circles aren’talways easy to navigate, so they haven’tbeen very popular.“At modern roundabouts, triangular islandsat each entrance slow approaching vehicles,”explains Richard Retting, <strong>Institute</strong>senior traffic engineer and an author of thestudy. “In older traffic circles, no physicalstructures prevent drivers from speedingright into the intersection. This lack of controlcontributes to high-speed conflicts insidethe circle” — a problem solved by theislands at roundabouts.Another feature is that vehicles approachingroundabouts yield to circulatingtraffic. <strong>No</strong> stopping is required. Some oldertraffic circles and many conventional intersectionsalternate traffic with stop signs orsignals. Roundabouts enable all cars tomove continuously through intersections atthe same low speed.“People assume that because there areso many traffic signals out there, they mustbe efficient. The fact is, they’re not. Whenhalf of the cars are stopped at an intersectionat any given time, delays are inevitable.It may seem counterintuitive that roundaboutsincrease capacity while loweringspeeds, but that’s exactly what happens,”Retting points out.Other design elements set roundaboutsapart from traffic circles. Pedestrians crossonly at the perimeter, vehicles can’t turn leftahead of the central island, and parking isn’tallowed inside the circle. These requirementsminimize distractions and opportunities<strong>for</strong> collisions.More common in other countries: Thetraffic calming properties of roundaboutsmay explain why they’ve been widely usedin other countries but not in the UnitedStates. The American penchant <strong>for</strong> fast drivinghas created a culture where “slowingdown” seems an encroachment on convenience.But the bias <strong>for</strong> speed isn’t justamong drivers. American universities andinstitutions that influence road planning andengineering have rein<strong>for</strong>ced the historicalpractice of building high-speed intersec-

<strong>Status</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, <strong>Vol</strong>. <strong>35</strong>, <strong>No</strong>. 5, <strong>May</strong> <strong>13</strong>, <strong>2000</strong> 3tions. Teachings haven’t emphasized trafficcalming as a preventive measure, at leastnot until recently.“The priority <strong>for</strong> road planners and engineersin this country has been to processas much traffic as possible. Traffic signalshave become the technology of choice. It’shard to deviate from that approach,” O’Neillexplains. “Countries in Europe and elsewherehave been much more progressive infocusing on traffic calming and making intersectionssafe <strong>for</strong> pedestrians. They caughton long ago to something we’ve ignored becauseof our fascination with technology.Recent interest in roundabouts in the UnitedStates is one sign that priorities finallyare shifting.”Geometry eliminates the worst crashes:Roundabouts benefit from good geometry,exhibiting only a fraction of the troublesomecrash patterns typical of right-angleintersections. Such intersections “place vehicleson a high-speed collision course,with crashes avoided only if drivers obeytraffic laws and use good judgment. Researchshows many drivers don’t, so thepotential is high <strong>for</strong> right-angle, left-turn,and rear-end conflicts,” Retting explains.Such conflicts make up about two-thirds ofpolice-reported crashes on urban arterials.The geometry of roundabouts eliminatesmany of the angles and traffic flows thatcreate opportunities <strong>for</strong> crashes, particularlythe right-angle and rear-end kind thattend to produce injuries. The lack of rightangles, combined with reductions in speed,make the intersections safer <strong>for</strong> pedestriansand bicyclists as well as people in cars. Thespeed depends on the intersection but generallyremains at about 15 mph. At thatspeed, drivers and others on the road havemore time to react, so there’s a smallerchance of collision. When crashes do happen,most will be minor.Fewer pedestrian crashes: Concern hasbeen expressed that installing roundaboutsmight endanger pedestrians, but these fearsappear unfounded. Experience in Europeshows roundabouts reduce the risk of pedestriancrashes. Such crashes also declinedat the U.S. roundabouts (continues on p.6)

4 <strong>Status</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, <strong>Vol</strong>. <strong>35</strong>, <strong>No</strong>. 5, <strong>May</strong> <strong>13</strong>, <strong>2000</strong>In pedestrian crashes,it’s vehicle speedthat matters the mostElderly pedestrians are atgreater risk of dying thanyounger pedestriansRegardless of age, pedestrians involvedin crashes are more likely to be killed as vehiclespeeds increase. In crashes at anyspeed, older pedestrians are more likely todie than younger ones. These are the twomain findings of a report on pedestrianinjuries recently prepared by the PreusserResearch Group <strong>for</strong> the National HighwayTraffic Safety Administration.Analyzing crashes across the country, researchersfound that fewer than 2 percent ofstruck pedestrians died in crashes that occurredwhere posted speed limits were slowerthan 25 mph. Where speed limits were 50mph or higher, more than 22 percent ofstruck pedestrians died. The correlation wasmuch the same when researchers looked atvehicle travel speeds — crash data fromFlorida show the proportion of serious injuriesand fatalities among pedestrians wentup along with vehicle speeds, as estimatedby police investigating the crashes.“Pedestrians age 65 and older are morethan 5 times as likely to die in crashes thanpedestrians age 14 or less, and the likelihoodof death increases steadily <strong>for</strong> ages inbetween,” the authors observe. Youngerpedestrians generally have a greater chanceof withstanding impacts unharmed, while elderlypedestrians are more susceptible toserious injury or death.These findings aren’t surprising giventhe physical disproportions between carsand pedestrians. Anyone who has walkedalong a street and felt the rush of carswhizzing by has a visceral sense of the danger.Car occupants have several tons of metalsurrounding them, and safety belts andairbags buffer them from crash <strong>for</strong>ces. Incontrast, pedestrians are unprotected andweigh a small fraction of any car that strikesthem, so they’re extremely vulnerable.The logical solution is to limit vehiclespeeds in areas where pedestrians are present,because speed determines impactseverity. With every small increase in speed,pedestrian deaths go up even faster. The authorscite research concluding that about5 percent of pedestrians hit by a vehicletraveling 20 mph will die. The fatality ratejumps to 40 percent <strong>for</strong> cars traveling 30 mph,80 percent <strong>for</strong> cars going 40 mph, and 100 percent<strong>for</strong> cars going 50 mph or faster.Lowering speed limits alone can bringsmall improvements. In most studies, the authorsreport, actual travel speeds droppedby a quarter or less of the posted speed limitreductions. Effective en<strong>for</strong>cement is morecritical. <strong>Institute</strong> senior vice president AllanWilliams explains that “<strong>for</strong> en<strong>for</strong>cement toLowering speedlimits can bring smallimprovements, buteffective en<strong>for</strong>cementis more critical. Theconsequences of gettingstopped <strong>for</strong> speeding haveto be meaningful enoughto keep drivers fromknowingly takingthe risk.deter speeding, drivers must believe the en<strong>for</strong>cementef<strong>for</strong>ts are being made in the specificlocations where they drive and at thetimes when they drive there. Even the presenceof en<strong>for</strong>cement isn’t enough. The consequencesof getting stopped <strong>for</strong> speedinghave to be meaningful enough to keep driversfrom knowingly taking the risk.”It’s impossible to put a police officer onevery street, so cameras are a practicalmeans of increasing the perception of en<strong>for</strong>cement.Red-light cameras already havewon favor in jurisdictions around the country.Speed cameras aren’t as popular, butthey’re equally effective deterrents (see <strong>Status</strong><strong>Report</strong>, March 11, <strong>2000</strong>; on the web atwww.highwaysafety.org).6050403020101-20 21-25Percent of struck pedesby pedestrian age14 or younger15-2425-4445-6465 or older26-30Estimated vehicle t

<strong>Status</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, <strong>Vol</strong>. <strong>35</strong>, <strong>No</strong>. 5, <strong>May</strong> <strong>13</strong>, <strong>2000</strong> 5On the other hand, the designs of roadwaysoften encourage drivers to go fasterthan the posted speed limits. Travel speedscan be restricted by introducing road treatmentssuch as humps, rumble strips, pavingstones or other rough surfaces instead of asphalt,and by road narrowing (see <strong>Status</strong><strong>Report</strong>, <strong>May</strong> 2, 1998; on the web at www.highwaysafety.org). With the right planning,modern roundabouts and other road treatmentsdesigned to reduce speeds can servepedestrian safety as well as ease other trafficproblems.To make roads safer <strong>for</strong> pedestrians, engineersalso should place crosswalks awayfrom stop lines and merge areas. Traffic signalintervals should be set to allow pedestriansenough time to cross. And installingsidewalks or better lighting can prevent unnecessarycollisions.“Literature review on vehicle travelspeeds and pedestrian injuries” by W.A. Leafand D.F. Preusser is available by writing tothe National Technical In<strong>for</strong>mation Service,Springfield, VA 22161. Or find the study atwww.nhtsa.gov/people/injury/research/pub/HS809012.html.trians with fatal injuries,and vehicle speed31-<strong>35</strong> 36-45 46+travel speed (mph)

6 <strong>Status</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, <strong>Vol</strong>. <strong>35</strong>, <strong>No</strong>. 5, <strong>May</strong> <strong>13</strong>, <strong>2000</strong>(continued from p.3) in the new study, butthe numbers were too small to be significant.The combination of a rotary design andyield at entry, as opposed to right anglesTechnical guide on the wayThe Federal Highway Administration(FHWA) has laid some groundworkto support roundabouts. Theagency’s new guide aims to be “thedefinitive source of in<strong>for</strong>mation relatedto the planning, operation, design,and configuration of modern roundaboutsin the United States.”As FHWA points out, roundaboutshave limitations as well as strengths.The guide presents in<strong>for</strong>mation onboth positives and negatives to helpengineers and planners make the bestdecisions about when and how to useroundabouts.This in<strong>for</strong>mation comes just intime. “Interest in modern roundaboutshas grown as a result of positiveinternational experience,” saysFHWA’s Joe Bared, who directed theproject. “Hundreds of research papersare now available, and designsare being copied from the Australiansand Europeans.” The publication interpretsbest practices from aroundthe world in light of accepted U.S. designstandards.“Designing roundabouts requiresa lot of skill,” Bared notes. “It's nothigh tech, but it takes skill to get thespeed right and leave enough roominside the circle <strong>for</strong> vehicles to maneuver.”This attention is important inboosting roundabout construction —and helping towns and cities reap thebenefits. “The more roundabouts, thebetter,” Bared says.“Roundabouts: an in<strong>for</strong>mationalguide” (FHWA-RD-00-067) will be onthe internet at www.tfhrc.gov. It alsowill be available by faxing FHWA’s<strong>Report</strong> Center, 301/577-1421.and stop controls, lends other safety benefits.Because there are no traffic signals toobey, drivers don’t feel compelled to “beatthe red light” or be first to cross the linewhen the light turns green. This not only reducescollisions but also takes the edge offat least one manifestation of aggressive driving.Plus the absence of a traffic signal andthe curved roadway associated with roundabouts<strong>for</strong>ce drivers to pay attention totheir surroundings, which further enhancesroad safety.Cheaper, cleaner, and a nicer view:Roundabouts are becoming popular in theUnited States <strong>for</strong> more than just safety reasons.They’re less expensive than intersectionscontrolled by traffic signals, saving upto $5,000 per year per intersection in electricityand maintenance.Fewer traffic snarls due to blocked intersectionsor backups can mean additionalsavings. For example, a pair of roundaboutsintroduced at a freeway interchange in Vail,Colorado, saves $85,000 each year in trafficcontrol costs.Environmental and aesthetic benefitsadd to the appeal. Roundabouts cut vehicleemissions and fuel consumption by reducingthe time drivers sit idling at intersections.Traffic that moves more slowlythrough intersections creates less noise andcongestion, minimizing the expressway lookand feel of roads in urban and suburban areas.Landscaping on the islands replaces theasphalt of conventional intersections,which offers visual appeal and restores a bitof nature. Roundabouts also create visualgateways to communities or neighborhoods,and in commercial areas they canimprove access to adjacent properties.“Roundabout construction should bestrongly promoted as an effective safetytreatment at intersections,” Retting concludes.“There’s nothing to lose from constructingthem and everything to gain. Theproof is already there.”For a copy of “Crash reductions followinginstallation of roundabouts in the UnitedStates” by B. Persaud et al., write: Publications,<strong>Insurance</strong> <strong>Institute</strong> <strong>for</strong> Highway Safety,1005 N. Glebe Rd., Arlington, VA 22201.Worst theft losses are<strong>for</strong> Mercedes model;2 of 3 worst are AcurasThe Mercedes S class, a very large luxurycar, heads the list of passenger vehicleswith the highest insurance losses <strong>for</strong> theft.Overall losses <strong>for</strong> this car are 10 times higherthan the average <strong>for</strong> all passenger cars.

<strong>Status</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, <strong>Vol</strong>. <strong>35</strong>, <strong>No</strong>. 5, <strong>May</strong> <strong>13</strong>, <strong>2000</strong> 7This is the first time in five years that a utilityvehicle hasn’t topped the list of vehicleswith the worst theft losses, which are publishedannually by the Highway Loss Data<strong>Institute</strong> (HLDI).“The Mercedes S class has appeared onthe 10 worst list <strong>for</strong> 5 years. It’s obviouslyan attractive target <strong>for</strong> professional thievesbecause of its value,” says Kim Hazelbaker,HLDI senior vice president.The two-door Acura Integra has the secondworst result, with losses also 10 timeshigher than the average among 1997-99 passengervehicles. These high overall lossesare produced by different factors, Hazelbakerexplains. The Mercedes has extremelyhigh average loss payments per claim, whilethe Acura’s claim frequency is very high.The four-door Integra has the third highestoverall theft loss result. <strong>No</strong>w Honda,which manufactures Acuras, has equippedall Integras <strong>for</strong> the <strong>2000</strong> model year withpassive immobilizing antitheft devices.During the 1980-99 model years, theftclaim frequencies have declined significantly,but this trend has been mostly offset byincreasing theft losses per claim. In 1999,the last year <strong>for</strong> which in<strong>for</strong>mation is available,the average theft loss payment perclaim also declined.Worst overall theft lossesMake and series Model years Size and type ResultMercedes S class long wheelbase 1997-99 Very large luxury four-door car 1001Acura Integra 1997-99 Small two-door car 996Acura Integra 1997-99 Small four-door car 757Mitsubishi Montero Sport 4 wheel drive 1997-99 Midsize four-door utility vehicle 616Mercedes SL class convertible 1997-99 Small sports car 539Nissan Maxima 1997-99 Midsize four-door car 509Lexus GS 300/400 1997-99 Large luxury four-door car 421BMW 3 series 1997-99 Midsize luxury two-door car 409BMW 7 series long wheelbase 1997-99 Very large luxury four-door car 387Lincoln Navigator 4 wheel drive 1998-99 Large four-door utility vehicle 387<strong>No</strong>te: Results are relative average loss payments per insured vehicle year; 100 represents the average <strong>for</strong> all cars.<strong>Insurance</strong> theft claim frequencies andaverage loss payments per claim, 1980-991815Claim frequency per 1,000 insured vehicle yearsAverage loss payment per claim$6,000$5,00012$4,0009$3,0006$2,0003$1,0001980 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99Model Year

STATUS REPORT1005 N. Glebe Rd., Arlington, VA 22201703/247-1500 Fax 703/247-1588Internet: www.highwaysafety.org<strong>Vol</strong>. <strong>35</strong>, <strong>No</strong>. 5, <strong>May</strong> <strong>13</strong>, <strong>2000</strong>NON-PROFIT ORG.U.S. POSTAGEPAIDPERMIT NO. 252ARLINGTON, VARoundabouts are becoming more familiar on U.S.roads, not just <strong>for</strong> safety reasons ...................... p.1Pedestrian deaths increase with the speed ofcrashes; older pedestrians die more often incrashes at all speeds ............................................ p.4New FHWA guide to roundabouts ...................... p.6<strong>Insurance</strong> theft losses vary widely among passengervehicles ............................................................. p.6Photos on pp. 1-3 courtesy of WalkableCommunities, Inc.Contents may be republished with attribution.This publication is printed on recycled paper.ISSN 0018-988XThe <strong>Insurance</strong> <strong>Institute</strong> <strong>for</strong> Highway Safety is an independent, nonprofit, scientific and educational organization dedicated to reducingthe losses — deaths, injuries, and property damage — from crashes on the nation’s highways. The <strong>Institute</strong> is wholly supported by automobileinsurers:Alfa <strong>Insurance</strong>Allstate <strong>Insurance</strong> GroupAmerican Express Property and CasualtyAmerican Family <strong>Insurance</strong>American National Property and CasualtyAmica Mutual <strong>Insurance</strong> CompanyAmwest <strong>Insurance</strong> GroupAuto Club South <strong>Insurance</strong> CompanyAutomobile Club of Michigan GroupBaldwin & Lyons GroupBituminous <strong>Insurance</strong> CompaniesBrotherhood MutualCali<strong>for</strong>nia <strong>Insurance</strong> GroupCali<strong>for</strong>nia State Automobile AssociationCameron CompaniesCGU <strong>Insurance</strong> GroupChubb Group of <strong>Insurance</strong> CompaniesChurch MutualColonial PennConcord Group <strong>Insurance</strong> CompaniesCotton StatesCountry CompaniesErie <strong>Insurance</strong> GroupFarmers <strong>Insurance</strong> Group of CompaniesFarmers Mutual of NebraskaFidelity & DepositFoundation ReserveFrankenmuthThe GEICO GroupGeneral Casualty <strong>Insurance</strong> CompaniesGMAC <strong>Insurance</strong> GroupGrange <strong>Insurance</strong>Harleysville <strong>Insurance</strong> CompaniesThe Hart<strong>for</strong>dIdaho Farm BureauInstant Auto <strong>Insurance</strong>Kansas Farm BureauKemper <strong>Insurance</strong> CompaniesLiberty Mutual <strong>Insurance</strong> GroupMerastarMercury General GroupMetLife Auto & HomeMiddlesex MutualMontgomery <strong>Insurance</strong> CompaniesMotor Club of America <strong>Insurance</strong> CompanyMotorists <strong>Insurance</strong> CompaniesMSI <strong>Insurance</strong> CompaniesNational Grange MutualNationwide <strong>Insurance</strong><strong>No</strong>rth Carolina Farm Bureau<strong>No</strong>rthland <strong>Insurance</strong> CompaniesOklahoma Farm BureauOld Guard <strong>Insurance</strong>Oregon Mutual GroupOrionAutoPalisades Safety and <strong>Insurance</strong> AssociationPekin <strong>Insurance</strong>PEMCO <strong>Insurance</strong> CompaniesThe Progressive CorporationThe PrudentialResponse <strong>Insurance</strong>Rockingham GroupRoyal & SunAllianceSAFECO <strong>Insurance</strong> CompaniesSECURAShelter <strong>Insurance</strong> CompaniesState Auto <strong>Insurance</strong> CompaniesState Farm <strong>Insurance</strong> CompaniesThe St. Paul CompaniesTokio MarineUSAAVirginia Mutual <strong>Insurance</strong> CompanyWarrior <strong>Insurance</strong> GroupYasuda Fire and Marine of AmericaZurich U.S.