the evolution of the western genre resulting from social changes in ...

the evolution of the western genre resulting from social changes in ...

the evolution of the western genre resulting from social changes in ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

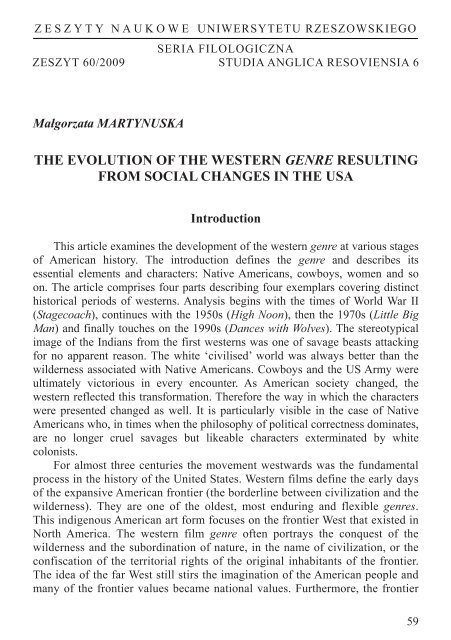

Z E S Z Y T Y N A U K O W E UNIWERSYTETU RZESZOWSKIEGOSERIA FILOLOGICZNAZESZYT 60/2009 STUDIA ANGLICA RESOVIENSIA 6Magorzata MARTYNUSKATHE EVOLUTION OF THE WESTERN GENRE RESULTINGFROM SOCIAL CHANGES IN THE USAIntroductionThis article exam<strong>in</strong>es <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>western</strong> <strong>genre</strong> at various stages<strong>of</strong> American history. The <strong>in</strong>troduction def<strong>in</strong>es <strong>the</strong> <strong>genre</strong> and describes itsessential elements and characters: Native Americans, cowboys, women and soon. The article comprises four parts describ<strong>in</strong>g four exemplars cover<strong>in</strong>g dist<strong>in</strong>cthistorical periods <strong>of</strong> <strong>western</strong>s. Analysis beg<strong>in</strong>s with <strong>the</strong> times <strong>of</strong> World War II(Stagecoach), cont<strong>in</strong>ues with <strong>the</strong> 1950s (High Noon), <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> 1970s (Little BigMan) and f<strong>in</strong>ally touches on <strong>the</strong> 1990s (Dances with Wolves). The stereotypicalimage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Indians <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> first <strong>western</strong>s was one <strong>of</strong> savage beasts attack<strong>in</strong>gfor no apparent reason. The white ‘civilised’ world was always better than <strong>the</strong>wilderness associated with Native Americans. Cowboys and <strong>the</strong> US Army wereultimately victorious <strong>in</strong> every encounter. As American society changed, <strong>the</strong><strong>western</strong> reflected this transformation. Therefore <strong>the</strong> way <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong> characterswere presented changed as well. It is particularly visible <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> NativeAmericans who, <strong>in</strong> times when <strong>the</strong> philosophy <strong>of</strong> political correctness dom<strong>in</strong>ates,are no longer cruel savages but likeable characters exterm<strong>in</strong>ated by whitecolonists.For almost three centuries <strong>the</strong> movement westwards was <strong>the</strong> fundamentalprocess <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> United States. Western films def<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> early days<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> expansive American frontier (<strong>the</strong> borderl<strong>in</strong>e between civilization and <strong>the</strong>wilderness). They are one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> oldest, most endur<strong>in</strong>g and flexible <strong>genre</strong>s.This <strong>in</strong>digenous American art form focuses on <strong>the</strong> frontier West that existed <strong>in</strong>North America. The <strong>western</strong> film <strong>genre</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten portrays <strong>the</strong> conquest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>wilderness and <strong>the</strong> subord<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> nature, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> name <strong>of</strong> civilization, or <strong>the</strong>confiscation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> territorial rights <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>al <strong>in</strong>habitants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> frontier.The idea <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> far West still stirs <strong>the</strong> imag<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> American people andmany <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> frontier values became national values. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, <strong>the</strong> frontier59

turn out to be cowards and frauds, while <strong>the</strong> outcasts provide flashes <strong>of</strong> nobility.As Andre Baz<strong>in</strong> noticed:[Stagecoach] demonstrates that a prostitute can be more respectable than <strong>the</strong>narrow-m<strong>in</strong>ded people who drove her out <strong>of</strong> town and just as respectable as an <strong>of</strong>ficer’swife; <strong>the</strong> dissolute gambler knows how to die with all <strong>the</strong> dignity <strong>of</strong> an aristocrat; that analcoholic doctor can practice his pr<strong>of</strong>ession with competence and devotion, that anoutlaw who is be<strong>in</strong>g sought for payment <strong>of</strong> past and possibly future debts can showloyalty, generosity, courage, and ref<strong>in</strong>ement, whereas a banker <strong>of</strong> considerable stand<strong>in</strong>gand reputation runs <strong>of</strong>f with <strong>the</strong> cashbox. (2004:146–147)Its Indian chase sequence across flats was thrill<strong>in</strong>g, and it had a decisive quote toend it: Saved <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> bless<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> civilization.More recently, <strong>in</strong> fact, critics and scholars have come to see Stagecoach <strong>in</strong>far more objective and complex terms with regard to <strong>changes</strong> not only <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>Western at <strong>the</strong> time but also <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hollywood film <strong>in</strong>dustry at large (Schatz2003:21). Stagecoach, <strong>in</strong> its days, was more <strong>of</strong>ten characterized as a melodramathan as a Western. On <strong>the</strong> whole <strong>the</strong> roles <strong>of</strong> women <strong>in</strong> Stagecoach, and <strong>in</strong> JohnFord's films <strong>in</strong> general, seem much more conventional than <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hollywoodmovies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1930s and 1940s (Garbowski 2006:65). In <strong>the</strong> course <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>journey two women achieve a new perspective on <strong>the</strong>ir personal qualities.However, nei<strong>the</strong>r Dallas nor Lucy has much <strong>in</strong> common with <strong>the</strong> heroic lead<strong>in</strong>gwomen <strong>of</strong> such films as The Philadelphia Story (1940) or Now, Voyager (1942),women who are passionately committed to <strong>the</strong>ir quests for selfhood. (Rothman2003:158)The first image <strong>of</strong> an Apache Indian <strong>in</strong> John Ford's Stagecoach (1939)follows a reaction shot <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> whiskey salesman Peacock, as he spots Yakima,<strong>the</strong> station-keeper Chris's wife. He warns everyone else that she is a savage! andChris replies jok<strong>in</strong>gly that she is a little bit savage, I th<strong>in</strong>k. He also allows thatshe is for him a k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> security, s<strong>in</strong>ce hav<strong>in</strong>g an Apache wife means <strong>the</strong> Apachesdon't bo<strong>the</strong>r me. These people have had to calculate <strong>the</strong>ir relationships for bothpleasure and safety. This scene illustrates how quickly and superficiallydeterm<strong>in</strong>ations about o<strong>the</strong>rs are made here. And especially subject to this quickjudgment are <strong>the</strong> Indians, whom, <strong>the</strong> film emphasizes, most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> whites knowonly by reputation or general appearance. The play <strong>of</strong> racial representation andjudgment or misjudgment echoes a number <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>stances <strong>of</strong> problematic racialrepresentation <strong>in</strong> Ford's films, while it also po<strong>in</strong>ts towards his larger concernwith <strong>the</strong> nature <strong>of</strong> civilization, particularly its fear <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r, its hardlyrepressed sense that even a little bit savage, usually seems far too excessive forAmerican tastes. (Telotte 2003:113)The movie is an allegory <strong>of</strong> American history <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> period before and afterWorld War II. It presents <strong>the</strong> formative period <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> American nation, <strong>the</strong>irvalues and ideals (Gobiowski 2004:413). Stagecoach symbolizes <strong>the</strong> civilized61

society meet<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> ‘o<strong>the</strong>rs.’ Ford elaborates on people’s behaviour <strong>in</strong> stressconditions <strong>result<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>from</strong> enter<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> unknown environment and <strong>the</strong> war path.Native Americans symbolize enemies, threat, danger, <strong>the</strong> ‘o<strong>the</strong>rs.’ A group <strong>of</strong>people drawn <strong>from</strong> all classes present a metaphor <strong>of</strong> American society – thatrides on <strong>the</strong> stagecoach <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> hostile environment fac<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> attack <strong>of</strong> wildsavages. The movie is an allegory <strong>of</strong> World War II with <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>me – <strong>the</strong>besieged condition <strong>of</strong> civilization.More Classic Westerns: High Noon (1952)High Noon (1952) was director Fred Z<strong>in</strong>nemann's only <strong>western</strong>. It is aclassic, dramatic morality tale <strong>of</strong> an abandoned lawman, carefully filmed <strong>in</strong>‘real-time.’ The m<strong>in</strong>imalist script written by Carl Foreman (who was blacklisteddur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> 50s' anti-Communist hear<strong>in</strong>gs) was a political allegory <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1950sMcCarthyism. Gary Cooper played <strong>the</strong> part <strong>of</strong> just-married (to Grace Kelly),small-town Marshal Kane who heroically stood up to four, gunsl<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g killerswithout assistance <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> townsfolk that he had defended for his entire career.This paralleled <strong>the</strong> historical <strong>in</strong>cident <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> early 50s' House Committee on Un-American Activities' witch-hunt for Communists <strong>in</strong> Hollywood, and <strong>in</strong>dictedthose who deserted <strong>the</strong>ir friends. 1 High Noon is an anti-HUAC allegory.Will Kane (Gary Cooper), <strong>the</strong> Marshal <strong>of</strong> Hadleyville, Kansas, has justmarried a pacifist Quaker Amy (Grace Kelly) and is prepar<strong>in</strong>g to move away tobecome a storekeeper. Then, however, <strong>the</strong> town learns that a psychopathiccrim<strong>in</strong>al Frank Miller is due to arrive on <strong>the</strong> noon tra<strong>in</strong> and his gang is wait<strong>in</strong>gfor him at <strong>the</strong> station. The worried townspeople encourage Kane to leave todefuse Miller’s desire for revenge. Only his former lover, an implied madamnamed Helen Ramírez (Katy Jurado) supports him. His wife threatens to leave on<strong>the</strong> noon tra<strong>in</strong> without him if he stays, but he stubbornly refuses to give <strong>in</strong>. Amychooses her husband’s life over her religious beliefs and shoots one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>gunmen and <strong>the</strong>n helps her husband to kill Miller. In front <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cowardlytownspeople who have come out <strong>of</strong> hid<strong>in</strong>g, Kane throws his Marshal’s Star <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>dirt and leaves town with his wife.High Noon is a portrait <strong>of</strong> a moral man who is opposed by his community,his friends, even his wife. The movie celebrated <strong>in</strong>dividuality and warned aga<strong>in</strong>st<strong>the</strong> failed public morality. The hero fights <strong>the</strong> villa<strong>in</strong>s not for <strong>the</strong> sake <strong>of</strong> society1 HUAC (House Committee on Un-American Activities) was <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Red Scare. Itopened hear<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> 1947 and exam<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>the</strong> motion picture <strong>in</strong>dustry for <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>of</strong>communism. S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong>y were photographed by newsreels and by <strong>the</strong> TV networks, <strong>the</strong>y ga<strong>in</strong>ed alot <strong>of</strong> public <strong>in</strong>terest. Cases <strong>of</strong> communism <strong>in</strong> Hollywood films were <strong>in</strong>vestigated and a blacklistconsist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> names <strong>of</strong> those suspected <strong>of</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g supporters <strong>of</strong> communism was compiled.62

ut out <strong>of</strong> his own sense <strong>of</strong> duty (Skwara 1985:43–47). The movie is an antitriumphalportrayal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> man <strong>of</strong> conscience set aga<strong>in</strong>st a society that refuses tospeak out aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>in</strong>justice (<strong>in</strong> this case <strong>the</strong> blacklist.) While Cooper’s Will Kanecarries most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> symbolic and dramatic weight, Grace Kelly’s Amy rema<strong>in</strong>s<strong>the</strong> character with <strong>the</strong> dilemma <strong>of</strong> conscience: she is <strong>the</strong> dedicated ‘pacifist’ whoallows her pacifist conscience to abandon her human loyalties. In <strong>the</strong> end,however, abstract moral convictions must give way to real life. A pacifist, facedwith her first real test, has just brought two men to <strong>the</strong>ir violent deaths and sheleaves town with her man. Grace Kelly’s naive Amy is no match for KatyJurado’s sensuous and know<strong>in</strong>g Helen. Her view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world is untested. Sheresolves abstract moral dilemmas <strong>in</strong>to real-life choices, and does what any realman or woman would do and chooses blood over <strong>the</strong> Bible. The dramatic appeal<strong>of</strong> High Noon is that even moral bravery must take on <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong> externalaction. While High Noon was unique <strong>in</strong> its time for its <strong>in</strong>ner tension, it stillrema<strong>in</strong>ed true to its action <strong>genre</strong> and resolved all conflict with that greatest <strong>of</strong>American magical symbols: <strong>the</strong> handgun.High Noon certa<strong>in</strong>ly asks us, on a deep mythic level, to understand conflictand courage. History has shown that nonviolence and peacemak<strong>in</strong>g are active<strong>social</strong>, political and certa<strong>in</strong>ly moral positions. They are played out <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> largercontext <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se <strong>social</strong> and political arenas, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> community, and rarely throughisolated action and certa<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong>volve personal courage and moral qualities.Plac<strong>in</strong>g Amy’s nonviolence with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Western myth where, by <strong>genre</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ition,personal violence is <strong>the</strong> only way to resolve moral issues, is ultimately ra<strong>the</strong>runfair. Amy’s dilemma is not that she is a moral person but that she is a fictionalcharacter: she faces a real, existential crisis <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Western town on <strong>the</strong> frontiers<strong>of</strong> reality. Here gunplay is <strong>the</strong> only means allowed to resolve conflict.Z<strong>in</strong>nemann used <strong>the</strong> mythical background <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Old West to attackcontemporary American values (especially dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> period <strong>of</strong> blacklists).Criticism <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cowardly majority and contempt for <strong>in</strong>tellectual conformismreflect <strong>the</strong> <strong>social</strong> reality <strong>of</strong> 1950s America. (Gobiowski 2004:414)Westerns <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1970s: Little Big Man (1970)Arthur Penn's Little Big Man (1970) is a fable about <strong>the</strong> expansion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Old West <strong>from</strong> an adaptation <strong>of</strong> Thomas Berger's novel. Dust<strong>in</strong> H<strong>of</strong>fman stars asJack Crabb, <strong>the</strong> only white survivor <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Battle <strong>of</strong> Little Big Horn (also knownas Custer's Last Stand), who is recount<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> days <strong>of</strong> his younger years. Helived his life amongst white settlers and <strong>the</strong> Indians, yet was always on <strong>the</strong>fr<strong>in</strong>ges. H<strong>of</strong>fman plays Jack <strong>from</strong> teen years <strong>in</strong>to old age. His story is a fantasticone: captured by Indians as a boy, raised <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> ways <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ‘Human Be<strong>in</strong>gs’ bypaternal mentor Old Lodge Sk<strong>in</strong>s, accept<strong>in</strong>g non-conformity and liv<strong>in</strong>g63

peacefully with nature. He constantly shuttles back and forth between <strong>the</strong> whiteand Indian worlds. Crabb apparently was adopted by Native Americans, adoptedby Christian fanatics, was <strong>the</strong> fastest gun <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> west, an honest bus<strong>in</strong>essman, anot so-honest bus<strong>in</strong>essman, a drunken slob, filthy rich. In <strong>the</strong> process, hebefriends everyone <strong>from</strong> Wild Bill Hickock to George Armstrong Custer and is agunsl<strong>in</strong>ger, a snake-oil salesman and an Army scout. Jack gets married to aSwedish woman but <strong>the</strong> Indians capture her. While search<strong>in</strong>g for his wife Jackgets back to his Cheyenne family who treat him as a tribe member. Jack preferslife as a ‘Human Be<strong>in</strong>g.’ Each switch between <strong>the</strong> white and Indian realitydeepen his isolation.The movie has elements <strong>of</strong> both comedy and tragedy and exposes <strong>the</strong> lies <strong>of</strong>U.S. history via a tall tale. As some reviewers claim Little Big Man is very mucha bullet<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> its time (Ventura 2003) The film was released dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> VietnamWar when <strong>the</strong> country was decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>from</strong> Eisenhowerian optimism to Nixoniancynicism. The US expansionist policy <strong>in</strong> Indoch<strong>in</strong>a is analogous to <strong>the</strong> Americansettlement westwards. The cowboys fight<strong>in</strong>g Indians symbolize Americansoldiers and <strong>the</strong> Viet Cong. However, it is no longer clear who represents <strong>the</strong>good guys. Penn used <strong>the</strong> <strong>genre</strong> as an area <strong>of</strong> protest aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong> U.S. expansion<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Old West.Native Americans <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> movie are no longer wild creatures butrepresentatives <strong>of</strong> a noble race <strong>of</strong> peaceful and civilized people who are be<strong>in</strong>gsystematically exterm<strong>in</strong>ated by <strong>the</strong> representatives <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> US government(Gobiowski 2004:415). The film’s lack <strong>of</strong> respect for historical characters ispresented with <strong>the</strong> embodiment <strong>of</strong> General Custer. Noteworthy for portray<strong>in</strong>gNative Americans as <strong>the</strong> good guys and General Custer as <strong>the</strong> bad guy, Little BigMan is a reversal <strong>of</strong> earlier Hollywood standards. The parallels to U.S. Indoch<strong>in</strong>apolicy are barely hidden. The most effective scene <strong>in</strong> Little Big Man is <strong>the</strong>Washita River Massacre, <strong>in</strong> which Custer's Cavalry kills an entire village,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g women and children. This cruel scene evokes <strong>the</strong> American <strong>in</strong>tensivephase <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Vietnam War – specifically <strong>the</strong> My Lai Massacre. Parallel<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>Vietnam tragedy, <strong>the</strong> film demythologized <strong>the</strong> past and revealed acts <strong>of</strong> crueltyperformed on ethnic Indians by US forces. It is an allegory about <strong>the</strong> bloodyresults <strong>of</strong> American imperialism.Through attacks on <strong>the</strong> logics <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world <strong>of</strong> <strong>western</strong>s and Wild Westmythology Penn contributed to <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> anti-<strong>western</strong> <strong>genre</strong>(Kolasiska-Pasterczyk 2007:188). The director focuses on <strong>the</strong> <strong>social</strong> andpsychological alienation <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividuals or groups different <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> majority –<strong>the</strong> so called <strong>the</strong> ‘o<strong>the</strong>rs’. Penn always portrays <strong>the</strong> m<strong>in</strong>ority group – <strong>the</strong> ‘o<strong>the</strong>rs’<strong>in</strong> a positive way. They have to stand aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong> society that can solve itsproblems only through <strong>the</strong> means <strong>of</strong> force and violence. The unprovokedmassacres <strong>of</strong> Indian villages, <strong>the</strong> cruelty and lack <strong>of</strong> any moral code or values <strong>of</strong>white soldiers, and <strong>the</strong> hopelessness and despair <strong>of</strong> Indians are <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>mes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>64

movie. The ma<strong>in</strong> issue is <strong>the</strong> clash <strong>of</strong> cultures. The whites seem to be obsessedwith <strong>the</strong>ir version <strong>of</strong> civilization and want to impose it upon everyone, even ifthat means destroy<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> unique Native American culture. However, <strong>the</strong> ‘whiteworld’ seems to lose when compared with <strong>the</strong> ‘red world.’ Penn destroys <strong>the</strong>myths <strong>of</strong> legendary heroes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Wild West. America is presented as a country <strong>in</strong>a state <strong>of</strong> value crisis.The Decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>of</strong> Westerns <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1990s: Dances with Wolves (1990)Dances with Wolves (1990) works on many levels. It is an adventure, atouch<strong>in</strong>g romance, and a stirr<strong>in</strong>g drama. The film is Kev<strong>in</strong> Costner's directorialdebut, noted as one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> few <strong>western</strong>s that cast Indians <strong>in</strong> act<strong>in</strong>g roles, usedLakota Sioux subtitles, and viewed Native Americans <strong>in</strong> a sympa<strong>the</strong>tic way andnot as blood-thirsty savages. The film describes <strong>the</strong> relationship between a CivilWar soldier and a band <strong>of</strong> Sioux Indians. It opens as Union lieutenant John W.Dunbar attempts to kill himself on a suicide mission, but <strong>in</strong>stead becomes anun<strong>in</strong>tentional hero. His actions lead to his reassignment to a remote post <strong>in</strong> SouthDakota. The fort turns out to be deserted with broken down shacks <strong>in</strong> a barevalley. He stays <strong>the</strong>re alone for months and his only companions are a friendlywolf that he names Two Socks and his faithful horse Cisco. Gradually, over time,he becomes comfortable with his peaceful surround<strong>in</strong>gs. When <strong>the</strong> Sioux come,<strong>the</strong>y are unfriendly and treat him with suspicion, even hostility. Dunbar behavesas he does towards <strong>the</strong> wolf, encourag<strong>in</strong>g, gentle and patient. At first, <strong>the</strong>re ismutual distrust, but, as Dunbar and <strong>the</strong> Sioux <strong>in</strong>teract and beg<strong>in</strong> to communicate(each learn<strong>in</strong>g a few words <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r's language), <strong>the</strong>y form a bond. Wi<strong>the</strong>very pass<strong>in</strong>g day, Dunbar f<strong>in</strong>ds himself more and more <strong>in</strong>fatuated with <strong>the</strong>Sioux way <strong>of</strong> life.Dances with Wolves conta<strong>in</strong>s several well-executed battle scenes but <strong>the</strong>most breathtak<strong>in</strong>g sequence is <strong>the</strong> buffalo hunt. It is a high adrenal<strong>in</strong>e sequencethat marks <strong>the</strong> moment when Dunbar f<strong>in</strong>ally rejects his old culture to embracehis new way <strong>of</strong> life. Attracted by <strong>the</strong> natural simplicity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sioux lifestyle, hechooses to leave his former life beh<strong>in</strong>d to jo<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>m, tak<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> name Danceswith Wolves. What happens, through a series <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>cidents, is that Dunbarbecomes accepted by <strong>the</strong> Indians and slowly <strong>in</strong>tegrates <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong>ir lives. This is anatural <strong>evolution</strong>, based on mutual respect. Even his love <strong>of</strong> Stands With A Fist(Mary McDonnell), a white woman captured by <strong>the</strong> tribe as a child, already awidow, takes time to grow. His peaceful existence is threatened, however, whenUnion soldiers arrive on <strong>the</strong> Sioux land.Dances with Wolves reverses <strong>the</strong> traditional roles <strong>of</strong> cowboys and Indians(Berardnelli). Costner portrays <strong>the</strong> Sioux tribe <strong>in</strong> a positive way, contrary to <strong>the</strong>irenemies, <strong>the</strong> Pawnee. The movie <strong>changes</strong> some conventions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>genre</strong>. Areas65

that used to be presented <strong>in</strong> black and white symboliz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> good and <strong>the</strong> evilare shown <strong>in</strong> a more complex way. For example <strong>the</strong> American soldiers are notthoughtless brutes but imperfect human be<strong>in</strong>gs. Costner tried to make <strong>the</strong> film asau<strong>the</strong>ntic as possible and cast only Native Americans as Indians. The Siouxspeak Lakota language and a full wolf is used for Two Socks.ConclusionThe Western represents adventure, achievement, optimism for <strong>the</strong> future, <strong>the</strong>beauty <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> land, and <strong>the</strong> courage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividuals who won <strong>the</strong> land. Theclassic <strong>western</strong> can be an allegory <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fight between good and evil. Americanvalues – <strong>in</strong>dividualism, self-reliance and equality <strong>of</strong> opportunity – were allpresent <strong>in</strong> both <strong>the</strong> frontier life and <strong>western</strong>s. Movie-makers used <strong>western</strong>s tocomment on historical and political events. The analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> historicalbackground and <strong>the</strong> <strong>changes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> American society prove <strong>the</strong>re is a connectionbetween <strong>the</strong> society and <strong>the</strong> <strong>western</strong>. Along with <strong>the</strong> <strong>changes</strong> <strong>of</strong> Americansociety <strong>the</strong> <strong>western</strong> <strong>genre</strong> underwent transformations as well. With <strong>the</strong>development <strong>of</strong> new perceptions some issues were presented <strong>in</strong> a different way.Especially <strong>the</strong> image <strong>of</strong> Native Americans was completely revised as Americansbecame more sensitive towards ethnic m<strong>in</strong>orities – <strong>the</strong> ‘o<strong>the</strong>rs.’ Beh<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong>simple plot and <strong>the</strong> characters <strong>the</strong>re is a hidden message. The function <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Western is to provide <strong>the</strong> vehicle for our dreams, s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>in</strong> most cases we havesettled on our realities. (Fen<strong>in</strong> 1962:341)ReferencesBooksBaz<strong>in</strong>, A. 2004. What is c<strong>in</strong>ema? Vol. II, (translated by Hugh Gray). Berkeley: University <strong>of</strong>California Press.Fen<strong>in</strong>, G.N. and W.K. Everson 1962. The Western, <strong>from</strong> Silents to C<strong>in</strong>erama. New York: BonanzaBooks.Gobiowski, M. 2004. Dzieje Kultury Stanów Zjednoczonych. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo NaukowePWN.Skwara, J. 1985. Western odrzuca legend. Warszawa: Modzieowa Agencja Wydawnicza.ArticlesGarbowski, Ch. 2006. „John Ford. Cigo i poszukiwanie” [<strong>in</strong>:] K<strong>in</strong>o Amerykaskie. Twórcy,E. Durys and K. Klejsy (eds), Kraków: Rabid, pp. 49–72.Kolasiska-Pasterczyk, I. 2007. “Arthur Penn – odkamywanie Ameryki” [<strong>in</strong>:] Mistrzowie K<strong>in</strong>aAmerykaskiego, .A. Plesnar and R. Syska (eds), Kraków: Rabid, pp. 185–208.66

Rothman, W. 2003. “Stagecoach and <strong>the</strong> Quest for Selfhood” [<strong>in</strong>:] John Ford's Stagecoach, B.K.Grant (ed.) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 158–177.Schatz, T. 2003 “Stagecoach and Hollywood's A-Western Renaissance” [<strong>in</strong>:] John Ford'sStagecoach, B.K. Grant (ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 21–47.Telotte, J.P. 2003. “»A Little Bit Savage« Stagecoach and Racial Representation” [<strong>in</strong>:] JohnFord's Stagecoach, B.K. Grant (ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 113–131.Internet ReviewsBerard<strong>in</strong>elli, J. Review <strong>of</strong> Dances with Wolveshttp://www.metacritic.com/video/titles/danceswithwolves.htmlVentura, E. 2003. “His So-Called Life” Review <strong>of</strong> Little Big Manhttp://www.popmatters.com/film/reviews/l/little-big-man.shtml67