Volume 10(2) - The California Lichen Society (CALS)

Volume 10(2) - The California Lichen Society (CALS)

Volume 10(2) - The California Lichen Society (CALS)

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Bulletinof the<strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong><strong>Volume</strong> <strong>10</strong> No.2 Winter 2003

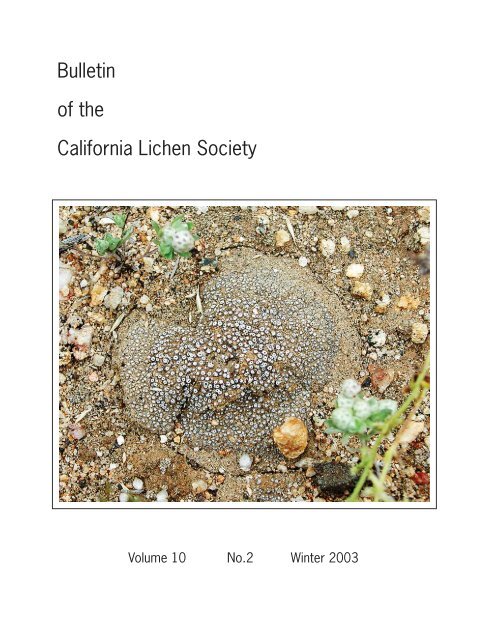

<strong>The</strong> <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> seeks to promote the appreciation, conservation and study ofthe lichens. <strong>The</strong> interests of the society include the entire western part of the continent, althoughthe focus is on <strong>California</strong>. Dues categories (in $US per year): Student and fixed income- $<strong>10</strong>, Regular - $18 ($20 for foreign members), Family - $25, Sponsor and Libraries- $35, Donor - $50, Benefactor - $<strong>10</strong>0 and Life Membership - $500 (one time) payable to the<strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong>, P.O. Box 472, Fairfax, CA 94930. Members receive the Bulletin andnotices of meetings, field trips, lectures and workshops.Board Members of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong>:President: Bill Hill, P.O. Box 472, Fairfax, CA 94930,email: Vice President: Boyd PoulsenSecretary: Judy Robertson (acting)Treasurer: Stephen BuckhoutEditor: Charis Bratt, 1212 Mission Canyon Road, Santa Barbara, CA 93015,e-mail: (See also below for Editorship change.)Committees of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong>:Data Base:Charis Bratt, chairpersonConservation: Eric Peterson, chairpersonEducation/Outreach: Lori Hubbart, chairpersonPoster/Mini Guides: Janet Doell, chairperson<strong>The</strong> Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> (ISSN <strong>10</strong>93-9148) is edited by Charis Bratt.Effective Januar 31, 2004 Tom Carlberg, Six Rivers National Forest, Eureka, CA 95501, will become editor. Manuscripts for Volumn 11(1) should be addressedto him. <strong>The</strong> Bulletin has a review committee including Larry St. Clair, Shirley Tucker,William Sanders and Richard Moe, and is produced by Richard Doell. <strong>The</strong> Bulletin welcomesmanuscripts on technical topics in lichenology relating to western North Americaand on conservation of the lichens, as well as news of lichenologists and their activities. <strong>The</strong>best way to submit manuscripts is by e-mail attachments or on 1.44 Mb diskette or a CDin Word Perfect or Microsoft Word formats. Submit a file without paragraph formatting.Figures may be submitted as line drawings, unmounted black and white glossy photos or35mm negatives or slides (B&W or color). Contact the Production Editor, Richard Doell, at for e-mail requirements in submitting illustrations electronically. Areview process is followed. Nomenclature follows Esslinger and Egan’s 7 th Checklist on-lineat . <strong>The</strong> editorsmay substitute abbreviations of author’s names, as appropriate, from R.K. Brummitt andC.E. Powell, Authors of Plant Names, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, 1992. Style follows this issue.Reprints may be ordered and will be provided at a charge equal to the <strong>Society</strong>’s cost. <strong>The</strong>Bulletin has a World Wide Web site at and meets at the group website .<strong>Volume</strong> <strong>10</strong>(2) of the Bulletin was issued December <strong>10</strong>, 2003.Front cover: Acarospora thelococcoides (Nyl.) Zahlbr. Riverside County, Southern <strong>California</strong>.1x. Photography by Jim Rocks. (See article on page 36 by Knudsen)

Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong><strong>Volume</strong> 11 No.1 Winter 2003Distributions and Habitat Models of Epiphytic Physconia in North-Central <strong>California</strong>Sarah JovanOregon State UniversityDepartment of Botany and Plant PathologyCorvallis, OR 97331-2902Abstract:-I examined the distributions of eight Physconia species in northern and central <strong>California</strong>: Physconiaamericana, P. californica, P. enteroxantha, P. fallax, P. isidiigera, P. isidiomuscigena, P. leucoleiptes,and P. perisidiosa. Distributions are based upon lichen community data collected for the Forest Inventory andAnalysis Program in over 200 permanent plots. Physconia californica was not found while P. leucoleiptes wasinfrequent across the landscape, occurring sporadically around the periphery of the Central Valley. Physconiaisidiomuscigena occurred only once in the study plots, growing on Quercus sp. in Stanislaus county. This siteis unusual in that this species is often saxicolous and known primarily from southern <strong>California</strong>. <strong>The</strong> remainingPhysconia species were more frequent across the landscape with distributions centered in the Central Valley. Iderived habitat models for these more common species using nonparametric multiplicative regression to help explainhow distributions relate to environmental variables. Distributions of P. enteroxantha, P. isidiigera, and P.perisidiosa were well described by one or more environmental gradients while P. fallax and P. americana wereonly weakly associated with single predictors. Considering that many Physconia species are considered nitrophilous(nitrogen-loving), the habitat models would probably be better had an estimate of ammonia deposition beenincluded. <strong>The</strong>re are not, however, any comprehensive estimates of ammonia deposition for the study area.IntroductionEpiphytic Physconia species are common, conspicuouscomponents of the lichen flora in northernand central <strong>California</strong> yet we know surprisinglylittle about their distributions and ecology. Severalspecies, such as P. americana, P. enteroxantha,P. isidiigera, and P. perisidiosa, are characteristicof hardwood stands in the Central Valley andSierra Nevada foothills, although distributionsin surrounding regions like the Modoc Plateau,northwest coast, and central <strong>California</strong> coast areless clear. We know even less about the regionaldistribution of P. leucoleiptes, a species common ineastern North America, and the three most recentlydescribed species, P. californica, P. fallax, and P. isidiomuscigena(Esslinger 2000). Distribution maps forthe latter three species were published for southern<strong>California</strong> (Esslinger 2001) although distributionsfor northern and central <strong>California</strong>, north of Ventura,remain largely unexplored. Physconia fallax isreported for northern <strong>California</strong> and Washingtonwhile most known P. isidiomuscigena and P. californicasites are reported from relatively dry Southern<strong>California</strong> counties (Los Angeles, Tulare, San Diego,and Riverside; Esslinger 2000).Our first objective was to describe the distributionsof eight epiphytic Physconia species in northernand central <strong>California</strong> using a large database oflichen community surveys. <strong>The</strong>se species includeP. americana, P. californica, P. enteroxantha, P. fal-29

Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 11(1), 2004lax, P. isidiigera, P. isidiomuscigena, P. leucoleiptes,and P. perisidiosa. Secondly, I used nonparametricmultiplicative regression (NPMR) with a localmean estimator to build habitat models describingwhich climatic, topographic, and stand descriptionvariables best explain the distributions of the mostcommon Physconia species. <strong>The</strong>se models will providea valuable first step towards understandingPhysconia ecology in the region. As habitat modelingwith NPMR methods is uncommon, the processwill be briefly described in this paper although amore rigorous background can be found at http://oregonstate.edu/~mccuneb/NPMR.pdf and inthe work of McCune et al. (2003), which describes arelated form of NPMR.MethodsDistribution maps were derived from two databasesof lichen community surveys conducted forthe USDA Forest Inventory and Analysis program(FIA). Because of their usefulness as bioindicators,the FIA program collects extensive data onepiphytic lichens in forested areas throughout theUnited States. Field crews collected vouchers andestimated the abundance of each epiphytic macrolichenspecies occurring above 0.5 m on woodyspecies or in the litter. <strong>Lichen</strong> community surveyslasted a minimum of 30 minutes and a maximumof two hours (methodology detailed in Jovan 2002& McCune et al. 1997). To characterize forest standstructure, crews measured total basal area, basalarea of hardwoods, basal area of softwoods, standage, overstory species diversity, and dominanttree species at each plot. Climatic variables wereextracted from the Precipitation-Elevation Regressionson Independent Slopes Model (PRISM; Dalyet al. 1994, 2001, 2002), which included mean annualdew temperature, maximum annual temperature,mean annual precipitation, mean number ofwet days per year, mean annual relative humidity,and minimum annual temperature.<strong>The</strong> larger of the two databases consists of 207plots surveyed in 1994 and from 1998-2001. Sitescovered all of northern and central <strong>California</strong> exceptthe Great Basin region. Plots were located on apermanent sampling grid and were typically 27 kmaway from their nearest neighbor. Plots were notsampled in non-forested areas, causing lower plotdensities in some parts of the study area such as thesouthern San Joaquin Valley. <strong>The</strong> second databaseconsists of 33 additional plots surveyed in 2002.Plots were located in urban parks throughout thegreater Central Valley, which encompasses the CentralValley, greater Bay area, northern central coast,and Sierra Nevada foothills.I re-examined all Physconia vouchers for P. fallax, P.californica, and P. isidiomuscigena, as most collectionswere identified before description of these species,and all three look similar to other species in thegenus. I did not include data from other studies orherbaria, because environmental data needed forthe models would not be available. However, plotsin the two databases are well distributed over thestudy area and span a wide range of environmentalconditions. Thus, the maps should approximate thelarger distribution trends in northern and central<strong>California</strong>.Habitat ModelingI used NPMR with a local mean estimator to investigatehow distributions of the most abundantPhysconia species are associated with environmentalgradients. Single-species habitat models weredeveloped using the NPMR add-in module for thePCORD statistical software package (McCune &Mefford 1999). NPMR is a form of nonparametricregression. In essence, this method analyzes environmentaldata from sites where the target speciesoccurs to build a habitat model. <strong>The</strong> models workby estimating species occurrence for new sitesbased upon the proportion of occurrences at knownsites with similar environmental conditions.Model building is an iterative process in whichNPMR searches through all possible multiplicativecombinations of environmental variables to determinewhich are the best predictors of a target speciesoccurrence. I used a Gaussian kernel functionin which weights between 0 and 1 were assignedto all data points (Bowman & Azzalini 1997). Thus,for a given point, not all known sites contributedequally to the estimate. <strong>The</strong> more similar the environmentalconditions of the known sites are to thenew site, the higher it is weighted in the model forthat new site. <strong>The</strong> form of the Gaussian functionused for weighting is based upon the standarddeviation (“tolerance”) of each environmental variable.30

Physconia Distribution and Habitat MadelsModel quality was appraised with leave-one-outcross validation: (1) one data point was removedfrom the dataset; (2) the dataset (minus the removedsite) was used to estimate the response forthat point, using various combinations of environmentalvariables and tolerances; (3) model accuracywas determined by comparing estimates of speciesoccurrence for the removed site to actual speciesoccurrence at that site; (4) this process was repeatedfor all plots in the dataset and; (5) a Bayesian statistic,the logB, was used to compare the accuracy(performance) of each model to the performance ofa naïve model. In the naïve model I used, probabilityof occurrence at a given site equals the overallfrequency in the study area. According to Kass andRaftery (1995), a model with a logB greater than 2performs decisively better than a naïve model.<strong>The</strong> Physconia habitat models were based upon allsites included in the distribution maps. <strong>The</strong> modelswere used to generate univariate species responsecurves that depict the probability of a species alongan environmental gradient. <strong>The</strong>se models may beused in the future to estimate species occurrence atother sites if the same environmental variables areprovided.this species is typically saxicolous and has beencollected only a couple times in <strong>California</strong> frommore southern locales near Los Angeles. Physconialeucoleiptes occurred in low abundance at 8 siteswidely distributed around the periphery of theCentral Valley, occurring in the Sierra Nevada foothills,as far south as Kern county, and as far north asTehama county (Figure 1b). This species is knownResults and DiscussionSpecies DistributionsPhysconia isidiomuscigena and P. leucoleiptes wererare across the landscape while P. californica wasabsent. Physconia isidiomuscigena was found in onlyone site (specimen resides with author), growingepiphytically on Quercus sp. in Stanislaus county(Figure 1a). <strong>The</strong> collection was unusual in thatto be much more common in the eastern UnitedStates so its low frequency is not surprising.Physconia fallax was occasional within the studyarea but where it occurred it was typically abundant(Figure 1c). In <strong>10</strong> of the 15 sites I estimatedthere were over <strong>10</strong> thalli on the plot. <strong>The</strong> sites werewidely spaced in the greater Central Valley, extendinginto the dry region of Lassen and Modoc counties.Physconia fallax was absent on the immediatecoast but did occur within 15 miles of the ocean ina montane, Quercus douglasii stand in Los PadresNational Forest.31

Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 11(1), 2004Physconia americana, P. enteroxantha, P. isidiigeraand P. perisidiosa were more common in the studyarea, having distributions centering in or near theCentral Valley (Figure 1d, e, f & g). All species weresparse in high elevation plots and in the relativelycool Modoc Plateau and northwest coast. Distributionsof these species were generally similaralthough modest variation is evident in figure 1.Most notably, P. enteroxantha and P. americana seemless common south of the Bay area than in thenorth. Physconia americana also appears to be morecommon in the northern <strong>California</strong> Coast Rangesthan the other species I examined. Physconia isidiigeraoccurred in all urban plots, including parksin downtown Fresno, Merced, and San Jose whereepiphytic lichen species richness was low, rangingfrom 3 to 7 species. Usually, however, multiple Physconiaspecies were found on the same plot, oftenintermixed on the same tree. In the greater CentralValley urban plots where substrate data was collected,all four species occurred on a wide range ofhardwood substrates but were consistently absenton coniferous trees.Species Response CurvesHabitat models were constructed for the 5 most32

Table 1: Summary of NPMR habitat models. Tolerances are reported for the multivariate models.ResponseVariables logB VariablePhysiconia Distribution and Habitat ModelsSpecies response curves for each predictor areshown in Figure 2. Any given response curvenecessarily shows only the relationship betweena species occurrence and a single environmentalgradient. While the full multivariate NPMR modelsare useful for estimating occurrence across thelandscape, the complex multiplicative relation-ToleranceVariable Tolerance VariableP. americana 9.2 Elevation (m) 1137.36 Humidity (%) 2.16 * *P. enteroxantha 5.7 Elevation (m) 473.90 * * * *P. fallax 0.8P. isidiigera 22.7P. perisidiosa 19.6Max. Temperature(ºC) 27.88 * * * *Dew Temperature(ºC) 14.76Hardwood Richness0.84 Humidity (%) 4.32ToleranceMax. Temperature(ºC) 9.84 * *Mean Temperature(ºC) 3.22common species: Physconia americana, P. enteroxantha,P. fallax, P. isidiigera, and P. perisidiosa (Table 1).<strong>The</strong> distributions of most Physconia species wererelatively well described by NPMR habitat modelswith high logB statistics (Table 1; Kass and Raftery1995). Nonparametric multiplicative regressionidentified elevation as the best predictor of P. enteroxanthaand maximum temperature as the bestpredictor for P. fallax. <strong>The</strong> remaining species werebetter described by more complex models: relativehumidity and elevation were the best predictorsof P. americana occurrence, dew temperature andmaximum temperature were the best for P. isidiigera,and mean temperature, relative humidity, anddiversity of hardwood species were the best predictorsof P. perisidiosa.Figure 2: Species response curves from NPMR habitat models. Each species has 1-3 response curves. SD =standard deviations (tolerances) for univariate models.33

Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 11(1), 2004ships between environmental predictors are difficultto visualize and interpret as graphics. Thus,for example, the response curve for P. americana andhumidity does not account for the effects of elevationon occurrence. When the NPMR model is usedto estimate P. americana occurrence at a particularsite, however, both variables are considered simultaneously.Interpretation of the single-gradient responsecurves is relatively straightforward. For example,the curves for P. americana would be interpretedas follows: relative humidity is a moderatelystrong predictor of P. americana occurrence andthe probability of finding this species is relativelyhigh (0.27-0.40) for humidity levels between 48-64%. <strong>The</strong> probability steeply declines at a relativehumidity below 42% and above 69%. Elevation isalso a moderately strong predictor of P. americanaincidence. At elevations between 518-<strong>10</strong>97 m,incidence is expected to be high (0.40-0.41). Probabilityof P. americana is less than .05 at elevationsover 2042 m. All response curves should be readin this fashion. Small fluctuations in the responsecurves (i.e. the response curves for P. americana andhumidity) probably result from noise in the datasetor the action of other factors not accounted for inthe analysis.<strong>The</strong> P. fallax model was relatively weak as evidencedby the low logB and lack of strong environmentalpredictors (Table 1). <strong>The</strong>re are two probable explanations:1) the model was based upon relativelyfew sites and 2) I did not provide NPMR with themost relevant, defining habitat characteristics forthis species. <strong>The</strong> number of P. fallax sites may be underestimatedsince most lichen community surveyswere conducted before this species was described.Due to its yellow soralia, field workers could haveeasily overlooked this species as P. enteroxantha.ConclusionsWhile climate and stand structure are typicallyimportant factors influencing lichen distributions,one can’t conclude that the environmental predictorsidentified by NPMR are the cause of speciespresence or absence. A predictor may instead be acorrelate of the actual causal factor that determineshabitat suitability. However, the models inspiremany questions about Physconia ecology. Forinstance, are P. americana distributions limited byatmospheric moisture as suggested by the habitatmodel? If that is the case, what morphological andphysiological aspect of this species makes it so?Why do distributions of many of the other commonspecies seem more related to temperature?<strong>The</strong>se habitat models may also be used in practicalapplications like estimation of species occurrenceacross the landscape and identification of areaswhere each species is most likely to occur.Understanding the distribution of Physconia speciesacross the landscape is particularly importantbecause of their potential utility as indicator species.Past research has shown it is possible to mapNH 3with the distributions of nitrophilous (“nitrogen-loving”)species (van Herk 1999 & 2001). Physconiaenteroxantha and P. perisidiosa are generallyconsidered nitrophilous while P. americana, P. fallax,and P. isidiigera may also be nitrophilous or at leasttolerant to high levels of NH 3deposition. In thisstudy, all five species seemed more abundant in areaswhere one would expect high NH 3deposition,such as on wayside trees near livestock enclosuresand near areas of high automobile traffic. A logicalextension of this work would be to examine therelative influences of NH 3deposition and climateon Physconia distributions, which would be aninvaluable step towards realizing the full indicatorpotential of these species.Acknowledgements:I would like to thank the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> forproviding a student grant to fund the data analysis andwrite up of this study. We are very appreciative of theUSDA-Forest Service, PNW Research Station, and theEastern Sierra Institute for Collaborative Educationfor funding for this research. I gratefully acknowledgethe Forest Inventory and Analysis Program of the U.S.Department of Agriculture for providing the lichen communitydatabases used in this project. I would also like tothank Bruce McCune and Erin Martin for guidance withNPMR modeling and thoughtful reviews of the manuscript.Jennifer Riddell helped greatly with data collection,specimen identification, and data entry. Thank youalso to Dr. <strong>The</strong>odore Esslinger for confirmation of somePhysconia identifications.34

Physconia Distribution and Habitat ModelsLiterature CitedBowman, A.W. & Azzalini, A. 1997. AppliedSmoothing Techniques for Data Analysis: thekernel approach with S-Plus illustrations. OxfordUniversity Press, New York.Daly, C., R. P. Neilson & D. L. Phillips. 1994. Astatistical-topographic model for mappingclimatological precipitation over mountainousterrain. Journal of Applied Meteorology 33:140-158.Daly, C., G.H. Taylor, W. P. Gibson, T. W. Parzybok,G. L. Johnson, & P. Pasteris. 2001. High-qualityspatial climate data sets for the United Statesand beyond. Transactions of the American <strong>Society</strong>of Agricultural Engineers 43: 1957-1962.Daly, C., W. P. Gibson, G. H. Taylor, G. L. Johnson,& P. Pasteris. 2002. A knowledge-based approachto the statistical mapping of climate.Climate Research 22: 99-113Esslinger, T.L. 2000. A key for the lichen genus Physconiain <strong>California</strong>, with descriptions for threenew species occurring within the state. Bulletinof the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> (7): pp 1-6.Esslinger, T.L. 2001. Physconia. pp 373-383 in NashIII, T.H., Ryan, B.D., Gries, C., Bungartz, F.(eds.) <strong>Lichen</strong> flora of the greater Sonoran Desertregion. Arizona: <strong>Lichen</strong>s Unlimited.Jovan, S. 2002. Air quality in <strong>California</strong> forests:current efforts to initiate biomonitoring withlichens. Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong>9:1-5.Kass, R.E. & A.E. Raftery. 1995. Bayes factors. Journalof the American Statistical Association 90:773-795.McCune, B., J. P. Dey, J. E. Peck, D. Cassell, K.Heiman, S. Will-Wolf, & P. N. Neitlich. 1997.Repeatability of community data: species richnessversus gradient scores in large-scale lichenstudies. <strong>The</strong> Bryologist <strong>10</strong>0: 40-46.McCune, B. & M.J. Mefford. 1999. Multivariateanalysis on the PC-ORD system. Version 4.MjM Software, Gleneden Beach, Oregon.McCune, B., Berryman, S.D., Cissel, J.H. & Gitelman,A.I. 2003. Use of a smoother to forecastoccurrence of epiphytic lichens under alternativeforest management plans. Ecological Applications13: 11<strong>10</strong>-1123.Van Herk, C.M. 1999. Mapping of ammonia pollutionwith epiphytic lichens in the Netherlands.<strong>Lichen</strong>ologist 31: 9-20.35

Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 11(1), 2004Type Specimens: Investigations and ObservationsKerry Knudsen33512 Hidden Hollow DriveWildomar, <strong>California</strong> 92595kk999@msn.comWhen a lichen is described and published as anew taxon, the author designates as holotype aspecimen by collector, collection number, and theherbarium where it is deposited. This holotypeshould be an average specimen. <strong>The</strong> descriptionof the taxon should contain information on the fullrange of variations that naturally occur in the speciesas well as a list of other specimens examined.That’s ideal. Sometimes a new taxon is describedfrom a single or a few collections. <strong>The</strong>re can onlybe one holotype. Any other specimen collected onthe same day at the same place is an isotype. <strong>The</strong>seare duplicates. For various reasons one might designatea new collection as being representative ofthe original type specimen and that’s called a lectotype.<strong>The</strong>re are legal conventions, agreed on by all,and enshrined in the Code of Botanical Nomenclaturethat govern these matters, including the nameof the taxon.<strong>The</strong> holotype and its description should serve toverify any future determination of a collection ofthat lichen. A good taxon is verifiable by repeatedapplication to living specimens. If problems arisein applying the taxon to reality, then eventually ataxon needs to be revised or even eliminated.That’s how we do it now. In the past things were abit looser.Recently at the University of <strong>California</strong> herbariumat Riverside (UCR) I had the pleasure of examiningsome “types” of several specimens collected byHerman Hasse on loan transfer from the ArizonaState University lichen herbarium (ASU) and fromthe Botanical Museum of Helsinki, Finland (H). I’dlike to share this experience because it is an excellentexample of the problems faced in the taxonomicrevision of lichens. It illustrates the problemsinvolved in using the old lichenological literature.And proves the value of types and herbaria.Recently I had collected a terricolous lichen in Riversideand San Diego Counties in <strong>California</strong>. It wasAcarospora thelococcoides (Nylander) Zahlbrucknerwith globular spores <strong>10</strong>-13µm in diameter. I usedBruce Ryan’s CD to determine it because there is nocurrent flora which includes it in the keys.Reading about A. thelococcoides in the old literature,I found Fink’s flora (1935) considers A. pleisoporaand A. pleistospora of Hasse’s flora (1913) synonymouswith A. thelococcoides. Reviewing Hasse’sdescriptions, I saw that A. pleiospora with spores<strong>10</strong>-13µm in diameter and an IKI+ red hymenial reactionis synonymous with A. thelococcoides. But A.pleiospora with spores 3-4 µm and an IKI+ blue reactionwould seem to be another species, contraryto Fink’s claim that it is same as A. thelococcoides. Iwondered if maybe a small-spore species existedbut got lost somewhere in this taxonomic tangle.I did not find a small-spored Acarospora in the SantaMonica Mountains or in the Verdugo Mountainswhere Hasse collected A. pleistospora.I examined Hasse’s exsiccati of A. pleiospora and A.pleistospora. <strong>The</strong>y both turned out to have <strong>10</strong>-13µmspores though they had various hymenial reactionsto IKI. I examined more recent collections ofA. thelococcoides too. I came to the conclusion therewas only this one species, A. thelococcoides, witha hymenium that could test IKI+ blue or red orboth! And with spores <strong>10</strong>-13 µm. I believe reportsof small-spore specimens were based on immaturespores and poor microscopes.To test my conclusions I first examined the “isotype”of Lecanora pleistospora which Hasse citesas the type of A. pleistospora (Hasse, 1913.) It wasfrom the National herbarium (US) and is part of theSmithsonian collections. It was actually a lectotypecollected at a different location and time and chosenby Hasse as same as the type.36

Type Specimen Investigations and ObservationsAs you can see from Frank Bungartz’s picture (seeback cover, Image 2) the specimen is in beautifulcondition. But it is not Acarospora thelococcoides. Imounted an apothecium. <strong>The</strong> specimen easily fitwith the taxon Acarospora obpallens (Nylander inHasse) Zahlbruckner which is distinguished byspores 4-5x1-1.5 µm, slender paraphyses (1-2µm),varied ascus shapes, even-to-flared exciple, withrugose-to-smooth brown thallus and black lowercortex formed around the rhizal attachment (Knudsen,unpubl).Did somebody put the wrong lichen in the packet?I doubt it. <strong>The</strong> problem is Hasse determined specimensof Acarospora pleistospora by the hymenial reactionof I+blue. A. thelococcoides can test either redor blue or both colors. Acarospora obpallens also hasvarious I hymenial reactions including blue. Hasseshared this lack of understanding of I reactions withNylander, who first introduced I as a hymenial reagentand died before he had a chance to learn hiserror (Orvo Vitikainen. 2001). Iodine tests are valuablewith some genera, like Peltula and Heppia, butin some genera can be very unpredictable. <strong>The</strong>yalso can be unpredictable based on concentrationsof I in solution (Bruce Ryan, pers.comm).To see if Hasse had misunderstood Nylander, I examinedthe type specimen from Helsinki, Finland,where the Nylander herbarium with 50,000 plusspecimens is preserved. <strong>The</strong>re are two specimensof Lecanora pleistospora (Hb.Nylander #24866 and#24867) with neither designated as holotype. <strong>The</strong>first one is an excellent specimen of what we nowcall A. thelococcoides. It looked like it was collectedyesterday by Wetmore. <strong>The</strong> other is a beautifulspecimen of A. obpallens with typical 4x1 µm spores,black cortical bottom and slender paraphyses. Asreported by Magnusson for A. obpallens, the specimenhad C+red reaction of cortex on microscopicslide (Magnusson, 1929) but this spot test I havefound to be as variable as IKI hymenial reactions.I was thankful Zahlbruckner solved this problemlong ago when he made Acarospora pleistospora andAcarospora pleiospora synonyms of Acarospora thelococcoides(Zahlbruckner, 1927).But where did the name Acarospora thelococcoidescome from?“Near Soldier’s Home:” type locality of manyspecies discovered by Hasse (post card circa 1890s)In 1886 Orcutt collected in San Diego County aspecimen of terricolous lichens. From this singlesmall collection Nylander first described Lecanorathelococcoides (Nyl., 1891). Magnusson examinedand diagnosed this collection as containing bothA. thelococcoides and A. obpallens (Magnusson 1929).William Weber on the packet confirms it is A.thelococcoides. James Lendemer (pers. comm.) hasexamined the type material of A. thelococcoides andconfirms that the type (see Lendemer in rev. for lectotypification)is conspecific with recent collectionsI have made. <strong>The</strong> type is in poor condition (as areother Acarospora types) and consists of only a fewfertile areoles. Because of the state of the type materialwe have chosen to also select an epitype to affixthe application of the name. Epitypes are specimenscollected by later authors when the type material isinadequate in order to aid later workers in understandinghow the name should be applied.In this case, Hasse and Nylander became confusedby results of IKI reactions and Zahlbruckner correctedthe problem. At present, lichenologists treatA. thelococcoides as one species and I agree with thisinterpretation.What is really great is that everybody depositedtheir “types” in herbaria and I could re-visit theproblem over a hundred years later and verifythe results with the “types.” <strong>The</strong> scientific value oftypes is also very evident in this next case.Hasse published Lecanora peltastictoides in <strong>The</strong> Bryologist,Vol. 17, pg. 63 in 1914. <strong>The</strong> specimen I examinedfrom the Farlow Herbarium at Harvard (FH) isconsidered the holotype. Hasse collected it in PalmSprings, Riverside County, <strong>California</strong>, 1901. As you37

Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 11(1), 2004can see from Frank Bungartz’s picture (see backcover, Image 3), the holotype is in excellent shape.It is not included in current Checklist of <strong>Lichen</strong>s ofNorth America (Esslinger and Egan, 1995.)Magnusson examined it on December 24, 1926, andwrote the following annotation by hand which is includedin the packet and is reproduced here exactlyas he wrote it: “Hym. 85µ white, uppermost 15-19µdirty brownish yellow, K+ pale, J+red. Par. In waterless discrete, K+dirty 1.8-2 µ thicken uppermost 2-4 joints swollen 5-6X3-4µ; Sp. Eight, 11-13X6.5-7µCortex 50-60 µ med (undecipherable) with particle,hyphae intricate, lumina 3-5 - 4-5 elongate or roundThal. All negative. Lecanora.”<strong>The</strong> apothecium I mounted did not stain to my satisfaction:it was possibly an Aspicilia-type but definitelynot an Acarospora. It was not clear to me thatit is the Lecanora-type. I saw fundamentally whatMagnusson described in his annotation especiallythe eight spores per ascus and the large size of thespores. <strong>The</strong> jointed paraphyses were moniliform. Ifelt one mount was all I should do because my aimwas to establish if it was a real species and thenlook for it in the field.To my knowledge Lecanora peltastictoides has neverbeen collected again.I see no reason why it is currently not includedin the checklist. I see good reason for it beingexcluded from Lecanora and transferred to Aspiclia.Members of <strong>CALS</strong> are actively looking for itaround the San Jacinto Mountains and I believewe will find it again. New collections are definitelyneeded for new taxonomic work to determine itscorrect genus.In this case the holotype verified its own taxon.And it will verify new collections when they aremade.Too often in the past in lichenology new specieshave been described or species have been put intosynonymy without adequate analysis of the typespecimens. But the preservation of types in herbariais the solution to these problems as my investigationsof Acarospora thelococcoides and Lecanorapeltastictoides show.AcknowledgementsSpecial thanks to Charis Bratt, Frank Bungartz,James Lendemer, Tom Nash, Bruce Ryan, AndySanders, Laurens B. Sparrius, Shirley Tucker, OrvoVitikainen, and Darrell Wright. I appreciate thehelp of James Lendemer and Darrell Wright in editingthe manuscript. Special thanks to the curatorsof the following herbaria: ASU, H, FH, MU, SBBG,US, and UCR.ReferencesEsslingler, <strong>The</strong>odore L., and Robert S. Egan.1995. A sixth checklist of the lichen-forming,lichenicolous and allied fungi of the UnitedStates and Canada. American Bryological and<strong>Lichen</strong>ological <strong>Society</strong>.Fink, Bruce. 1935. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> Flora of the UnitedStates. Ann Arbor, Michigan.Hasse, H. E. 1897. New species of lichens fromSouthern <strong>California</strong> as determined by Dr. Nylanderand the late Dr. Stizenberger. Bulletin ofthe Torrey Botanical Club, 24(9): 445-449.Hasse, H. E. 1913. <strong>The</strong> lichen flora of Southern<strong>California</strong>. Contributions to the United StatesNational Museum 17(1) 1-132.Magnusson, A.H. 1929. A monograph of the genusAcarospora. Kongl. Svenska Vetenskaps-AkademiensHandlingar, Stockholm 7:1-400.Ryan, Bruce. 2002. Keys to North American <strong>Lichen</strong>s.Privately-released CD.Nylander, W. 1891 Sertum <strong>Lichen</strong>eae Tropicae ELabuan et Singapore. Paris, France.Vitikainen, Orvo. 2001. “William Nylander (1822-1899) and <strong>Lichen</strong> Chemotaxonomy” <strong>The</strong> Bryologist<strong>10</strong>4(2):263-267.Zahlbruckner, A. 1927 Catalogus <strong>Lichen</strong>um Ubiversalis,Vol. 5. Gebrueder Borntraeger, Leipzig.Zahlbruckner, A. 1932. Catalogus <strong>Lichen</strong>umUniversalis. Vol. 8. Gebrueder Borntraeger,Leipzig.38

Abrothallus welwitschii in <strong>California</strong> on Sticta limbataMikki McGee8 Visitacion Avenue #<strong>10</strong>Brisbane, <strong>California</strong> 94005mikkimc@juno.comA number of collections of lichenicolous funguson Sticta limbata (Sm.) Ach. from coastal Central<strong>California</strong> have been identified as Abrothalluswellwitschii Tulasne. <strong>The</strong>se constitute first recordsfor the state.A. welwitschii is the name for an apotheciate/pycnidiate fungus that lives in the thallus ofS. limbata (also in S. fuliginosa (Hoffm.) Ach. inEurope). <strong>The</strong> apothecia are 0.3- 0.7mm diameter, appearingthrough angular ruptures onthe upper surface of this lichen.It is hemispheric, dark brownto black with, when young, anolive greenish pruina. <strong>The</strong>re areno rims or exciples (arthonioidcondition). Asci are large, thickwalled, and bitunicate. <strong>The</strong>eight ascospores are 16.6-17.6x 6.3-6.9µ (M. Cole, personalcommunication), obovate,unequally bilocular, brown,and punctate. <strong>The</strong> perfect stateusually accompanies the laterstages of the pycnidial form.broad base on the conidium seems to be a speciescharacter, other members of the form-genus havingmore narrowed bases.Collections have been made on Sweeney Ridge andSan Bruno Mt., in San Mateo Co., and on the <strong>CALS</strong>trip to the Pygmy Forest in Mendocino Co.I wish to thank Bill Hill for pointing out the initial<strong>The</strong> imperfect state is inthe pycnidial form-genusVouauxiomyces, characterizedby large globose to flaskshapedconidiophores withdistinctive black apertures. Conidia are 12-14x5-6µhyaline, essentially muffin shaped with a broadlytruncate base, unilocular, and a hemispheric toa short cylindrical shape, one end rounded. <strong>The</strong>Apothecia of Abrothallus welwitschii (the dark protrusions) on Stictalimbata. Author’s photo.collection (Sweeny Ridge), and Dr. MarietteCole and Dr. Paul Diederich for independentidentifications, and guidance in interpreting thestructure; and to Dr S. Tucker for critical commentson the manuscript.39

Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 11(1), 2004Questions and AnswersJanet Doell1200Brickyard Way #302Point Richmond, CA 94801rdoell@sbcglobal.net1. Question: What is the meaning of the word“exsiccati?”Answer: In lichenology, the word exsiccati refers toduplicate dried lichen specimens sent out to appropriateinstitutions and to colleagues. It is the pluralform of the Latin word exsiccat. <strong>The</strong> Latin verbexsiccare means to remove moisture or dry out, asdoes the English word exsiccate, which is a noun aswell as a verb. A system was set up eons ago, whenLatin was the language of science, to facilitate andorganize the distribution of duplicates to other lichenologistsaround the world.By the rules which were set up for these exchanges,when a lichenologist comes across an area wherethere is an abundance of a lichen with which he isthoroughly familiar, he can collect and prepare asmany packets of this species as he feels is justified.<strong>The</strong>n when he comes to another area where thesame condition exists for another species he knowswell, he can do the same thing. Eventually, he mayhave a large number of such packets. When he haspackets for 25 different species, he can put themtogether into a fascicle, and mail it off to herbariaor private collections. Each fascicle is numbered, asare all the packets. Along with the collections goesa small pamphlet listing all the names in the fascicleand information regarding the location whereeach specimen was collected. If he wants he cansend two fascicles, or 50 specimens. <strong>The</strong> number25 is not a hard and fast rule, but it is customary tosend that many at a time.<strong>The</strong> recipients then have specimens for their referencecollections which they know are correctlyidentified.2. Question: What determines a species in lichenology?40Answer: This question was left unanswered inthe last Bulletin in the discussion on classification.<strong>The</strong>re is no brief and succinct answer. <strong>The</strong> definitionwe learned in grade school, that members ofone species could breed with each other and notwith members of another species, is not applicableto lichens. Many of them reproduce vegetatively,and many details about how the exchange of geneticmaterial is carried out amongst the others areunclear. Thus the definition of a lichen species dependson similarities in morphology and anatomy,and in the past was subjective to some extent. Withthe advent of DNA studies and what they tell usof genetic makeup, along with modern microscopyand other new techniques this whole problem ofspecies definitions will eventually be solved. Inthe meantime lichenologists still depend largely onchemistry and structural details, and with observationsof the similarities between the members ofone species and the dissimilarities between it andother species.3. Question: What percentage of the lichenthallus does the photobiont (alga or cyanobacteria)represent, on the basis of volume?Answer: <strong>The</strong> photobiont represents 7% of the volumeof the lichen according to one reference, (Ahmadjian1993) and “no more than 20%, often muchless” in another (Purvis 2000).References:Ahmadjian, Vernon. 1993. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> Symbiosis.John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York.Brodo, I.M., S.S.Sharnoff, and S. Sharnoff, 2001.<strong>Lichen</strong>sof North America. Yale University Press,New Haven.Purvis, William, 2000. <strong>Lichen</strong>s. Smithsonian InstitutionPress, Washington, D.C.

<strong>CALS</strong> Educational Grants Program: $500.00 Available for 2004<strong>CALS</strong> Offers small academic grants to support researchpertaining to the <strong>Lichen</strong>s of <strong>California</strong>. Nogeographical constraints are placed on granteesor their associated institutions. <strong>The</strong> EducationalGrants Committee administers the EducationalGrants Program, with grants awarded to a persononly once during the duration of a project.Grant applicants should submit a proposal containingthe following information:1. Title of the project, applicant’s name, address,phone number, e-mail address. Date submitted.2. Estimated time frame for project.3. Description of the project: outline the purposes,objectives, hypotheses where appropriate, andmethods of data collection and analysis. Highlightaspects of the work that you believe areparticularly important and creative. Discusshow the project will advance knowledge of<strong>California</strong> lichens.4. Description of the final product: We ask you tosubmit an article to the <strong>CALS</strong> Bulletin, basedon dissertation, thesis or other work.5. Budget: summarize intended use of funds.If you received or expect to receive grants orother material support, show how these fit intothe overall budget.<strong>The</strong> following list gives examples of the kindsof things for which grant funds may be used ifappropriate to the objectives of the project:• Expendable supplies• Transportation• Equipment rental• Laboratory services• Salaries• Living expenses<strong>CALS</strong> does not approve grants for outrightpurchase of high-end items such as cameras,computers, software, machinery, or for clothing.6. Academic status: state whether you are a graduatestudent or an undergraduate student.7. Academic support: one letter of support froma sponsor, such as an academic supervisor ormajor professor, should accompany your application.<strong>The</strong> letter can be enclosed with theapplication, or mailed separately to the <strong>CALS</strong>Grants Committee Chair.8. Your signature, as the person performing theproject and the one responsible for dispersingthe funds.<strong>The</strong> proposal should be brief and concise.<strong>The</strong> Education Grants Committee brings its recommendationsfor funding to the <strong>CALS</strong> Board ofDirectors, and will notify applicants as soon aspossible of approval or denial.ReviewProposals are reviewed as received, by members ofthe committee using these criteria: Completeness,technical quality, consistency with <strong>CALS</strong> goals, intendeduse of funds, and likelihood of completion.Grant Amounts<strong>CALS</strong> grants are made in amounts of $500.00 orless.Obligations of Recipients1. Acknowledge the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> inany reports, publications, or other productsresulting from the work supported by <strong>CALS</strong>.2. Submit a short article to the <strong>CALS</strong> Bulletin.3. Submit any relevant rare lichen data to the<strong>California</strong> Natural Diversity Data Base usingNDDB’s field survey forms.How To Submit An ApplicationPlease email your grant application to:Lori Hubbart, Chair of <strong>CALS</strong> EducationalGrants Program: lorih@mcn.orgOr mail a hardcopy to:Lori HubbartP.O. Box 985Point Arena, CA 9546841

Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 11(1), 2004News and NotesUsnea WorkshopShingle Mill Preserve, San Mateo CountyMay 17, 2003A group of nine <strong>CALS</strong> members gathered at thehistoric cabin in San Mateo County where <strong>CALS</strong>was founded in 1994. History was not the themeof this outing, however. <strong>The</strong> surroundings there inthe Santa Cruz Mountains are heavily populatedby lichens of the genus Usnea, a group not knownfor ease of determination, and we wanted to try ourhand at identifying some of them.But before we got involved in that a short walk wasorganized to stretch our legs and check on someother examples of the lichen flora in that area. Wefound Peltigera polydactylon growing beside the trailabove Waterman Creek, and Cladonias in the mudbank nearby. In the mixed evergreen forest–Redwood,Doug Fir, Bay, Tanbark Oak, Madrone–wecame across many old friends such as Pseudocyphellariaanthraspis and P.anomala, Tuckermannopsisorbata, Evernia prunastri, Hypogymnia imshaugii, Pertusariaamara, Parmelia sulcata,and lots of Usnea.After eating our lunches at the historic cabin mentionedabove, we cleared the table and the Usneaspecimens were brought out for the workshop. <strong>The</strong>main thing we learned here was that Usneas reallyare very hard to key out.Using several keys we became acquainted withmany of the questions that arise in making thesedeterminations, i.e. Were isidiomorphs concave,tuberculate or superficial? How do fibrils, isidia,verrucae and papillae differ? Were the medullaryhyphae closely packed or loose? On the other hand,identifying the pinkish cord of U. ceratina (syn. californica)or the spiny apothecia of U.arizonica wereeasy.Finally we managed to key one out to theU.filipendula group with the help of “Macrolichensof the Pacific Northwest” by Bruce McCune andLinda Geiser.Present were Sara Blauman, Cherie Bratt, JanetDoell, Richard Doell, Bill Hill, Karen Howard,Kuni, Boyd Poulsen, and Ron Robertson.Reported by Janet Doell<strong>CALS</strong> Field trip to UC White MountainsResearch StationJuly 11-13, 2003<strong>The</strong> White Mountains are the highest ranges in theGreat Basin between the Sierra Nevada in <strong>California</strong>and the Wasatch Range in Utah. <strong>The</strong>y aresituated along the <strong>California</strong>-Nevada Border about225 miles east of the Pacific Coast. This area is thehome of the famous Bristlecone Pine forests. Treesover 4,500 years old have been dated, giving rise toa chronology back to 6,700 B.C. Because the woodof the Bristlecone Pine is very dense and resinous,it is resistant to decay. Dead, fallen, or even uprightindividuals persist on the landscape for thousandsof years.<strong>The</strong> UC White Mountains Research Station ofCrooked Creek is <strong>10</strong>,000 feet above sea level. Toget to the station, you must drive beyond SchulmanGrove, over a long, gravel road. Large graniteoutcrops surround and guard the entrance to theStation. Yellow-bellied marmots can be seen sunningon the boulders.Four buildings make up the station: one housesthe kitchen, dining area and upstairs−a large livingarea with couches, piano, and library, which alsoserves as a classroom with tables and black boards.<strong>The</strong>re are some adjacent rooms off the living areafor researchers and guests. Another large buildingis dormitory-like with 5 or 6 rooms with 2 to6 beds/bunk beds and communal bathrooms. <strong>The</strong>remaining buildings are called the Bristlecone cabins.<strong>The</strong>y are smaller spaces where there was more42

News and Notesprivacy, separate rooms with individual bathroomsand a small kitchen. <strong>The</strong> research station dates backto 1951, when there was only a Quonset hut calledthe ‘Met Hut’ because of the Meteorological studieshoused there.On Friday afternoon, July 11, <strong>CALS</strong> members beganto arrive at the station. At <strong>10</strong>,000’ elevation, weknew we had some altitude adjustment to make.Swollen ankles and wrists, headaches from theedema of high altitude affected most of us. Manydeveloped cracked lips and skin with the dryingair and winds.As we arrived, we walked up the trail by the graniteslope for our first survey of the lichens growingat this high altitude.After everyone arrived, we joined for dinner at 6:30. <strong>The</strong> station is well known for the excellent cuisineand we could attest to the truth of this claim.Mark Schrop, caretaker and also cook at the stationhad fixed delicious chicken with rice and bakedfresh berry pies for dessert. After dinner, Mark explainedthe rules of the station and told us some ofits history. Upstairs we had set up our microscopesand lap tops, books and identification gear, readyto look at our collections.Saturday morning started with breakfast of freshvegetables in eggs, turkey sausage and berry muffins.Our plans were to go to Sage Hen flat, an area abouta 25 minute walk from the station. Some made it tothe site, but many got too interested in the lichenson the way to move on.At noon we met back at the research station to eatour sack lunches of turkey, ham, and cheese sandwiches,cookies, fruit. We packed into our cars todrive to Patriarch Grove, at an elevation of 11,300feet, the highest Bristlecone Grove in the Mountains.Near tree line, the grove is the home of theworld’s largest Bristlecone Pine, the Patriarch Tree.<strong>The</strong> drive was spectacular. <strong>The</strong> light areas of dolomitesoils starkly contrast with the darker, shaleformations covered with sagebrush scrub growth.<strong>The</strong> Bristlecone Pine grows only on the poorer dolomitesoil. <strong>The</strong>se Groves were discovered in 1953so the forest district is celebrating a 50 th anniversarythis year.We explored for lichens at the upper BristleconePine Forest site, but found them very sparse on thedolomite, compared to the rich growth on the graniteoutcrops by Crooked Creek.Some decided to continue driving up the road tothe gate of the UC Barcroft Station. At an elevationof approximately 12,500ft, the treeless area waswindblown. Tiny alpine plants barely grew abovethe surface of the soil. After collecting lichens onthe rocks and soil, we drove the long way back tothe station where we had chili and cornbread, saladand homemade banana crème pie with ice creamfor dessert.We retired upstairs to microscopes and laptopswith photos for the evening.Sunday morning after cleaning the station, andhaving breakfast of eggs, potatoes, and muffins,we started our way out of the White Mtns.We hadsampled granite, dolomite and now were planningto look at the lichens on the shale and metamorphicrocks along White Mtn. Road. At the second stop,Andy, our resident archeologist found an atalaspear head that was approximately 3000 years old.<strong>The</strong> last stop was lunch stop and closing of the<strong>CALS</strong> White Mtn. field trip. All the cars but onewere parked facing the Eastern Sierra when thetragedy of the weekend happened. <strong>CALS</strong> President,Bill Hill fishtailed on the road behind us and rolleddown the hill probably 2 or 3 rolls. Miraculously, hewas not hurt as his seat belt held him tightly whilemicroscope boxes, cameras, books and laptop flewout of the car. <strong>The</strong> car landed right side up and Billwas able to open the door and get out, even thoughthe car was totaled. Andy heard Bill call and Andy,Boyd, Ron and Tamara rushed back to retrieve allof Bill’s belongings that were strewn down thehillside. Everyone headed off to the ranger stationat Schulman Grove where Bill put all of his belongingsin Sara Blauman’s car and the 2 drove toBishop. Bill’s car was towed out of the mountainsand Bill and Sara headed back to the Bay area.Participating were: Don Brittingham, Bill Madsen,43

Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 11(1), 2004Irene Winston, Sara Blauman, Kathy Faircloth,Tamara Sasake, Patty Patterson, Jerome Patterson,Boyd Poulsen, Bill Hill, Andy Pignoli, Judy andRon Robertson, Shirley and Ken Tucker, Janet andRichard Doell.Collectors:ST = Shirley and Ken TuckerSB = Sara BlaumanBP = Boyd PoulsenPP = Patti PattersonDB = Don BrittinghamJR = Judy and Ron RobertsonAcarospora smaragdula v. lesdainii H. Magn. STAcarospora strigata (Nyl.) Jatta STAcarospora thamnina(Tuck.) Herre ST, SB, JRAspicilia caesiocinerea (Nyl. ex Malbr.) Arnold ST, JRAspicilia contorta (Hoffm.) Kremp STAspicilia sp. (stalked) STBuellia bolacina Tuck. STBuellia lepidastroidea Imsh. (Ryan keys) ST, JRBuellia cf. papillata (Sommerf.) Tuck. STCaloplaca cf. ammiospila (Wahlenb.) H. Olivier STCaloplaca arenaria (Pers.) Müll.Arg. (C. Lamprocheilain some keys) ST,JRCaloplaca cf. castellana (Räsänen) Poelt STCaloplaca trachyphylla (Tuck.) Zahlbr. ST, SBCandelariella aurella (Hoffm.) Zahlbr. STCandelariella rosulans (Müll. Arg.) Zahlbr ST, SBCandelariella terrigena Räsänen ST, SB, JRCandelariella vitellina (Hoffm.) Müll ST, SBCatapyrenium sp. STCatapyrenium squamellum (Nyl.) J.W. Thomson JRChaenothecopsis debilis (Turner & Borrer ex Sm.)Tibell (on wood) STCladonia nashii Ahti STCollema tenax (Swartz) Ach. STDermatocarpon miniatum (L.) W. Mann JRDimelaena oreina (Ach.) Norman SB, JR, PPDiploschistes muscorum (Scop.) R. Sant. ST, JRLecanora cenisia Ach. ST, SB, JRLecanora garovaglii (Körber) Zahlbr. JRLecanora muralis (Schreber) Rabenh. ST, SB, JR, PPLecanora novomexicana H. Magn. SBLecanora polytropa (Hoffm.) Rabenh. ST,JRLecanora rupicola (L.) Zahlbr. JRLecanora. cf. sierrae B.D. Ryan & T. Nash STLecidea auriculata Th. Fr. ST, SB, JRLecidea atrobrunnea (Ramond ex Lam. & DC.)Schaerer ST, JR, PPLecidea diducens Nyl. STLecidea hassei Zahlbr. STLecidea lapicida (Ach.) Ach. var. lapicida (Ryan keys)STLecidea protabacina Nyl. STLecidea tessellata Flörke ST, JRLepraria neglecta (Nyl.) Erichsen STLeprocaulon subalbicans (Lamb) Lamb & Ward(squamules only, on sod) STLetharia vulpina (L.) Hue DBLobothallia alphoplaca (Wahlenb.) Hafellner ST, SB,PPMelanelia tominii (Oksner) Essl. SBPeltigera collina (Ach.) Schrader BPPeltigera ponojensis Gyelnik ST, JRPhyscia dubia (Hoffm.) Lettau ST, SB, JRPhyscia tribacia.(Ach.) Nyl. STPhysconia enteroxantha (Nyl.) Poelt. JRPhysconia isidiigera (Zahlbr.) Essl. JR, PPPhysconia isidiomuscigena Essl. STPhysconia muscigena (Ach.) Poelt ST, JRPlacidium squamulosum (Ach.) Breuss STPleopsidium chlorophanum.(Wahlenb.) Zopf ST, SB,JRPleopsidium flavum (Bellardi) Körber SBPolysporina simplex (Davies) Vezda STPseudephebe minuscule (Nyl. ex Arnold) Brodo & D.Hawksw. JR, BPPsora decipiens (Hedwig) Hoffm. SB, BP, JRPsora globifera (Ach.) Massal. ST, BPPsora pruinosa Timdal STRhizocarpon riparium Räsänen STRhizoplaca chrysoleuca (Sm.) Zopf. ST, SB, JR, PPRhizoplaca melanophthalma (DC.) Leuckert & PoeltST, SB, PPSarcogyne privigna (Ach.) A. Massal. STSarcogyne regularis Körber ST, DBSarcogyne similis H. Magn. STSporostatia testudinea (Ach.) A. Massal. JR, BPStaurothele drummondii (Tuck.) Tuck. ST, SB, JRUmbilicaria krascheninnikovii (Savicz) Zahlbr. ST,SB, PPUmbilicaria virginis Schaerer BP, JRVerrucaria sp. STVouauxiella lichenicola (Lindsay) Petrak & SydowSTXanthoparmelia coloradoensis (Gyelnik) Hale SBXanthoparmelia mexicana (Gyelnik) Hale SBXanthoria candelaria (L.) Th. Fr. SB44

News and NotesXanthoria elegans (Link) Th. Fr. ST, BP, SB, JRXanthoria sorediata (Vainio) Poelt SBReported by Judy Robertson<strong>CALS</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> Walk,San Pedro Valley Park,Saturday, Sept. 6, 2003San Pedro Valley Park is located in San Mateocounty near the city of Pacifica. It is a 1,150 acrepark with three fresh-water creeks: the south andmiddle forks of the San Pedro Creek, and BrooksCreek, which flow all year around. <strong>The</strong>se creeksprovide some of the few remaining spawning areasfor migratory Steelhead in the county.On Saturday, Sept. 6, Sara Blauman, Susanne Altermann,Stella Yang, Bill Hill, Loretta and JohnMcClelland, Jim Mackey, Brad Hinckley, CarolynPankow and Catherine Antista met for this lichenwalk with Judy Robertson as guide. <strong>The</strong> first 40minutes we gathered at a round picnic table to lookat an assemblage of lichen-covered twigs from thearea, learning the difference between foliose, fruticoseand crustose lichens; trying to discern yellowgreenfrom greenish-yellow, grayish white fromblue-gray; learning about the morphology and reproductivestructures of the specimens and keyingsome of the most common lichens in the park usinga simple key Judy had made.After this introduction to lichens we started the actualwalk in the park. We talked about lichen ecologyand that we would be seeing lichens growingon trees, soil, rocks and artificial surfaces throughoutthe day.<strong>The</strong> picnic area was filled with bay trees, willowand oaks. Interesting was a very old deciduous oaktrunk covered with a variety of lichen crusts on thehardened smooth squares of bark contrasted withthe deep grooves separating the squares, barren oflichens. <strong>The</strong> old trunk was covered with Ochrolechia,Lecanora, Graphis, Pertusaria, Caloplacaand Buellia species. We observed lichen successionfrom twig to trunk.We started up the Hazelnut trail and some of theparticipants were brave enough to taste the bitterPertusaria amara (Ach.) Nyl. on the live oak trunks.A small nucleus of Ramalina menziesii Taylor coveredthe branches on the beginning of the trailand Jim Mackey, resident botanist, said this wasthe only concentration of R. menziesii in the park.<strong>The</strong> moist coastal fog encouraged the growth ofDimerella lutea (Dickson) Trevisan on the oak trunkbeneath the Ramalina growth.<strong>The</strong> Hazelnut trail moves out of the oaks andthrough some open chaparral where we startedlooking at lichen growth on soil. Four species ofCladonia including Cladonia chlorophaea (Flörke exSummerf.). Sprengel and C. squamosa var. squamosa(Nyl. ex Leighton) Vainio with Fuscopannaria praetermissa(Nyl.) P.M. Jorg were growing on the soilbanks. <strong>Lichen</strong>s were not the only soil binders presentas a species of liverwort was also quite prevalentalong the trail.At the highest point in the walk we stopped at alive oak next to the trail. Covered with many folioseand fruticose lichens, this was a great place forlooking at lichen color contrasts and morphologydifferences and reinforcing what we had learned atthe picnic table at the beginning of the day. Again,the coastal influence was evident with Vermiliciniacephalota (Tuck.) Spjut & Hale and Heterodermia leucomelos(L.) Poelt growing on the trunk and twigs.Many foliose and fruticose lichens including Flavoparmeliacaperata (L.) Hale, Parmotrema chinense (Osbeck)Hale & Ahti, Parmelia sulcata Taylor, Puncteliasubrudecta (Nyl.) Krog, Xanthoria oregana Gyelnik,Nephroma helveticum Ach., Ramalina farinacea (L.)Ach. and R. pollinaria (Westr.) Ach. were growingon the tree.Judy challenged the participants to find a smallhummingbird nest hidden in the crook of thebranches, well camouflaged with lichens. It wasfound and photos taken. Sara Blauman, a birder,explained that the nest was probably never usedas it did not appear expanded as a nest would afterbeing filled with fledglings. <strong>The</strong> close proximity ofthe nest to the trail was the probable explanation.As we came back to the starting point of the hike,we circled through the Park Nature Trail to a lawnarea North of the Park Office. <strong>The</strong> smooth bark of45

Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 11(1), 2004the alder trees was a great place to see where lichencrusts completely covered the trunks. We couldhardly find a spot free of lichen growth. <strong>The</strong> smoothbark hosted Lecanora pacifica Tuck., Tephromela atra(Hudson) Hafellner, Caloplaca and Buellia speciesand the influence of the well-watered and fertilizedlawn area probably contributed to the growth ofXanthoria parietina (L.) Th. Fr. on the lower part ofthe trunks.<strong>The</strong> last stop was the cement in front of the Office.Earlier in the walk we found red, fuzzy trentepohliagrowing on the wood bridge crossing San Pedrocreek and here we would see an example of lichenon an artificial surface. <strong>The</strong> yellow-orange, sorediateCaloplaca citrina (Hoffm.) Th. Fr. was growingon the raised block of cement holding the flagpole.Many stayed for lunch in the picnic area wherewe talked about lichens and lichen projects. Bradbrought some slides of lichens and Bill and Judyhelped identify them. Carolyn Pankow of San PedroValley Park had organized the walk and Judypresented her with a CD and photos of the lichensin the park. It was an enjoyable day for all.Reported by Judy RobertsonField Trip to Cuyamaca Rancho State Park,San Diego CountyOctober 25, 2003Dr. Tom Nash III from Arizona State Universityguided us through a variety of lichen species inthe Cuyamaca Mountains of San Diego County. Wemade a loop hike beginning at Paso Picacho Campgroundthrough black oak and mixed coniferousforests. Dr. Nash had previously done some briefwork in the Cuyamaca Mountains, using the areaas a control for lichen-based air quality studies insouthern <strong>California</strong>.<strong>The</strong> goal of the trip was to explore the Cuyamacaarea further, and for most of us to.become morefamiliar with the southern <strong>California</strong> lichen species.Dr. Nash and Judy Robertson had permits forcollections while most of the group were just alongto learn and photograph. Ron Robertson also collecteda variety of mosses on the trip.We began at a series of rock outcrops and oaksnear the campground. Species included Dimelaenathysanota, Lecanora muralis, Lepraria sp. Diploschistesactinostomus, Lecidea atrobrunnea group, and Rhyzoplacamelanophthalma (Ram.) Leuckert & Poelt. Itwas interesting to see a very outstanding chocolatebrown Aspicilia that still has not been named. Onbark we noted Lecanora mellea(?) and Xanthoriapolycarpa.Most of the hike was spent along Azalia Creekin what were dense forests of incense cedar andwhite fur. <strong>The</strong> area had been burned in a low intensitycontrolled burn about 15 years ago and itwas nice to see a healthy variety of lichen speciesincluding large clumps of Hypogymnia. Bark alsocontained Lecanora carpenia, Lecidea sensustricta, Pertuseriamelanpunctia and Ochrolechia sp. Somewhatprophetically the topic of discussion turned to fireecology and we found outstanding colonies of Hypocenomycesp. and Trepeliopsis sp. on old burnedincense cedar stumps.We had lunch along the trail and continued by a seriesof rock outcrops with Dermatocarpon sp. beforereaching Azalia Springs. After a brief break therethe now tired group high tailed it back to the startingpoint. Many of the group then adjourned forsome socializing and dinner at Cuyamaca Lake.As we were leaving for home Wayne Armstrongand Steve noted a fire around dusk and as we droveback we noted two fire trucks coming from theMount Laguna area toward the beginnings of whatwould become the Cedar Fire. Little did any of thegroup know that this hike was our last opportunityto see the area as dense coniferous forest for quitesome time. By Monday night I watched from MountLaguna as the Cedar fire burned through the 500year old sugar pines near the top of Cuyamaca andMiddle Peak and on Tuesday afternoon, the firepicked up eastward speed and roared though thearea where we had just hiked three days before asa crown fire. Most of the trees in the area were lostalong with many of the nearby homes. Fire crewssaved the restaurant were we had dinner, but mostof the homes in the area were not so lucky.46

News and Notes<strong>The</strong> trip and the fire highlight the transitory andever changing nature of our environment. It alsopoints out how valuable collections are. <strong>The</strong> collectionsmade on this trip will be important guides bywhich to measure the future recovery of biologicaldiversity in the area. Wayne Armstrong of PalomarCommunity College took some great photographson the trip that are already up on his excellentwebsite at .Thanks again to our leader and all those who participated.<strong>The</strong> group included Dr. Tom Nash, student,volunteer, Judy Robertson, Ron Robertson,Andrew Pigniolo, Mary Ann Hawk, Wayne Armstrong,Wayne’s friend Steve, Sara Blauman, LawrenceGlacy, Kerry Knudsen, and Katz Hasebe.Reported by Andrew PignioloAn Introduction to Crustose <strong>Lichen</strong>sDarwin Hall, Rm 207, SSU, Cotati, CA.Noverber 15,2003Judy’s husband Ron Robertson had made a “teachingset” of crustose lichen specimens to use for thisworkshop. Each participant had the same 15 specimensto examine.We used the excellent descriptions of crustose lichenthalli in the <strong>Lichen</strong> Flora of the Greater SonoranDesert to compare and contrast the specimens. Weexamined different apothecial morphologies, thenused the compound microscopes to look at ourapothecial sections. Most types of spores wererepresented in the teaching set. We filled out worksheetsfor each specimen and then, the last activityin the afternoon, used all of the data to identify thespecimens. This was an intense day, with a lot fittedinto 6 hours but we ended with a pretty good feelfor crusts.Thank you to Dr. Chris Kjeldsen for making arrangementsfor the classroom in Darwin Hallwhere we could use the dissecting and new compoundscopes.Participating were Sara Blauman, Katz Hasebe,John and Loretta McClellan, Don Brittingham, TamaraSasake, Bill Hill, and Judy RobertsonReported by Judy RobertsonFrom our editor, Charis Bratt: “This is an SEMphoto of the spore of Texosporium sancti-jacobi– the ‘Woven spore lichen.’ A misnomer in myopinion, but the picture may be of interest.”Photo credit Dr. Sherwin Carlquist.See also article and illustrations of T. sancti–jacobi in <strong>CALS</strong> Bulletin 9(2), Summer 200220µ47

Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 11(1), 2004Upcoming EventsHowarth Park, Sonoma Co.Saturday, January <strong>10</strong>, 2004, <strong>10</strong> amNestled in the midst of the City of Santa Rosa isHowarth Park, 150 acres of oak woodland witha small lake, many walking paths and trailsidebenches. With mild climate and coastal fog, SonomaCounty is rich in lichen flora. Saturday, January <strong>10</strong>,Judy Robertson will be leading a lichen walk for thelocal CNPS chapter. <strong>CALS</strong> members are welcometo join. We will look for the common lichens in thePark, do some field identification, and talk aboutlichen ecology. We will start at <strong>10</strong> and end about 2.Bring a lunch.From Hwy <strong>10</strong>1 turn East on Hwy 12, continue Eastto Summerfield Road and turn left (North). <strong>The</strong>Howarth Park entrance will be on the right beforeyou get to Montgomery Drive. Turn right into thePark road and continue up the road to the largerparking lot by Lake Ralphine. Meet at the Naturetrailhead (by the maintenance shed).McClellan Ranch Park, Santa Clara Co.Saturday, January 17, 2003, <strong>10</strong> amThis is the <strong>CALS</strong> field trip originally planned forOctober 25, 2003 but cancelled due to the conflictwith the field trip to Cuyamaca State Park led byDr. Tom Nash. We have rescheduled it on this Januarydate.Following are the directions, but please refer to the<strong>CALS</strong> Summer 2003 bulletin for more informationabout the park. Directions: McClellan Ranch Parkis located in the city of Cupertino (Santa ClaraCounty). Take Highway 85 to the Stevens CreekBoulevard exit in Cupertino. Go west on StevensCreek for about a mile until it intersects with StevensCanyon Road. Make a left turn onto StevensCanyon Road, then proceed for about a third of amile (heading south), until you see McClellan Roadon your left. You may have to drive slowly to findthe street sign. Make a left turn onto McClellan,then proceed about one quarter of a mile, until youwill see a golf course on your right. At this pointslow down; the park will be on your immediateleft. <strong>The</strong>re is currently no admission fee.For more information about McClellan Ranch Park,please call Cupertino Parks and Recreation at (408)777-3120, or visit . We will meet in the parking lot at<strong>10</strong> am. Bring a lunch.Rock City Area Field Trip,Mt. Diablo, Contra Costa Co.<strong>10</strong>am, Saturday, January 31, 2004Followed by, at 5pm,<strong>CALS</strong> Potluck/Birthday Celebration/General MeetingBrickyard Landing ClubhousePoint RichmondThis promises to be a great day, full of <strong>CALS</strong> activities.We will start at the Rock Creek Area of Mt.Diablo at <strong>10</strong> am. Doris Baltzo, a long-time <strong>CALS</strong>member, will lead us on a lichen foray to this area,familiar to her as her Masters <strong>The</strong>sis was <strong>The</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong>sof Mount Diablo State Park. We will meet atthe Rock City Area of Mt. Diablo. Coming fromthe North or South on Hwy 680, watch for the MtDiablo signs, and turn east on Diablo Road (So. ofAlamo). Drive east to the South Gate. Rock Citywill be the first picnic area after the gate. This willbe our starting point. We may reach the summit,which has a fire trail around it with many rock lichens.Bring a lunch.At approximately 4 pm, we will drive to the BrickyardLanding Clubhouse in Pt. Richmond, wherewe will hold our annual <strong>CALS</strong> Potluck, BirthdayCelebration and General Meeting. If you need directionsto the clubhouse, contact Janet or Richardat or (5<strong>10</strong>) 236-0489After the meeting, Richard and Janet Doell willshow slides taken in connection with the preparationof their new mini guide to Southern <strong>California</strong><strong>Lichen</strong>s, which is approaching completion, and talkabout some of their experiences along the way.48

Upcoming Events<strong>CALS</strong> will furnish the cake, plates, utensils anddrinks for the Pot luck. Please bring your favoritedish to share.Contact Judy Robertson at or 707-584-8099 if you plan to attend the field trip and/ordinner.Beginning <strong>Lichen</strong> WorkshopUC Davis<strong>10</strong>am to 4pm, Saturday, February 28,2004This beginning lichen workshop is primarily forthe Davis Botanical Garden community, however,if there is available space, <strong>CALS</strong> members can attend.Please contact Judy Robertson if you areinterested.Point Reyes National Seashorefield trip to the lighthouse and PierceRanchSaturday, March 20, 2003A lichen walk at Pt. Reyes National Seashore. Wewill meet in the morning at the parking lot for theLighthouse at <strong>10</strong> AM and look at lichens in thatarea. <strong>The</strong>n we will proceed to the Pierce Ranchwhere there is a remarkable collection of lichens onthe old wooden fences there. Bring a lunch, a handlens, and warm clothes. <strong>The</strong>re will be no collecting.To sign up please contact Janet Doell at 512-236-0489 or e-mail her at .Northwest <strong>Lichen</strong>ologist MeetingEllensburg, WAshingtonMarch 25-27, 2004<strong>The</strong> NW <strong>Lichen</strong>ologist meeting will be in Ellensburg,WA, March 25-27, 2004. <strong>The</strong>re will be a fieldtrip on Saturday the 27th. Jeanne Ponzetti andRoger Rosentreter are in charge of the program,workshop and field trip. <strong>The</strong> “theme” is still notformalized at this point, but considering Jeanne’sand Roger’s expertise in soil crusts, that will probablybe the focus of the workshop and field trip.For more details as the date gets closer, go to the NW<strong>Lichen</strong>ologist Website at .Northern <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> TourSherwood Road, west of Willits andBrooktrails<strong>10</strong>am, Saturday, April 17, 2004<strong>The</strong> area is a wonderland of lush, lichen growth ofall kinds. <strong>The</strong> terrain is a transition zone betweenthe redwood and Douglas fir forest. <strong>The</strong>re are largeopen areas of meadows and wet zones with hugerock monoliths and out-crops providing a richenvironment for many species of lichens. <strong>CALS</strong>members Don Brittingham and the late Jerry Cookexplored this area for lichens. Don will guide usto the best lichen spots. Meet at the Skunk TrainRailroad Depot parking lot for carpooling to thevarious sites 15-20 miles away.In search of Verrucaria tavaresiae<strong>Lichen</strong> walk, bear valley trail to Arch RockPoint Reyes National Seashore, Marin Co.<strong>10</strong>am, sunday, may 1, 2004Dr. Dick Moe is an expert on the marine lichen Verrucariatavaresiae Moe. He will lead us to the site atArch Rock in Marin County where we will be ableto see this lichen that he described in the <strong>CALS</strong>Summer 1997 Bulletin (Vol. 4, No. 1). Dick claimsthat once you develop the right search image, thislichen will be a lot easier to spot elsewhere. We willstart at the Bear Valley Trail Parking lot. From theparking lot to Arch Rock is approximately 4 miles,so be prepared for a day of walking. We will explorefor lichens along the way. Bring a lunch andwater.Ongoing lichen identification workshopsDarwin Hall, Room 207, Sonoma State University.<strong>The</strong> 2 nd and 4 th Thursday of every month, 5 pm to8:30 pm. Join us every 2 nd and 4 th Thursday of eachmonth for these <strong>Lichen</strong> ID sessions at SSU. Webring our own specimens and use the classroomdissecting and compound scopes and a variety ofkeys to identify them. For more information contactJudy Robertson at .49

Bulletin of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 11(1), 2004AnnouncementsA Sincere Thanks<strong>The</strong> <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> would like to thankour benefactors, donors and sponsors for the secondhalf of 2003. <strong>The</strong>ir support is greatly appreciatedand helps in our mission to increase the knowledgeand appreciation of lichens in <strong>California</strong>.Benefactors:Irene BrownDonors:David MagneyPatti PattersonJohn PinelliSponsors:E. Patrick Creehan, M.D.Lawrence JanewayKerry KnudsenDonna MaythamElizabeth RushJames ShevockElection Time!<strong>CALS</strong> officers serve a two year term beginning inJanuary. January 2004 will be the beginning of the6 th term of officers. We are pleased to announce theproposed slate below. You will find a flyer in thisbulletin for you to cast your vote. Please returnthe ballot with your membership dues. A no votecast will be considered an affirmative vote for thefollowing slate:President Bill HillVice President Boyd PoulsenSecretary Sara BlaumanTreasurer Kathy Faircloth(Members at Large are the <strong>CALS</strong> BulletinEditors)Gift of Specimens<strong>The</strong> <strong>California</strong> <strong>Lichen</strong> <strong>Society</strong> has received from theHerbarium of Nonvascular Cryptogams, Monte L.Bean Life Science Museum, Brigham Young University,Larry St. Clair Curator, Fascicle No. 3 of“Anderson and Shushan: <strong>Lichen</strong>s of North America,”Nos. 51-75, except 60, 74, 7551. Cyphelium notarishii (Tul.) Blomb. & Forss.52. Dermatocarpon miniatum (L.) W. Mann53. Dimelaena oriena (Ach.) Norman54. Diploschistes muscorum (Scop.) R. Sant.55. Evernia divaricata (L.) Ach.56. Hypogymnia heterophylla L. Pike57. Icmadophila ericetorum (L.) Zahlbr.58. Imshaugia placorodia (Ach.) S.F. Meyer59. Lecanora novomexicana H. Magn.60. Lecanora varia (Hoffm.) Ach.61. Lobaria halllii (Tuck.) Zahlbr.62. Ochrolechia upsaliensis (L.) A. Massal.63. Parmelia sulcata Taylor64. Parmeliopsis ambigua (Wulfen) Nyl.65. Peltigera collina (Ach.) Schrader66. Peltigera venosa (L.) Hoffm.67. Physconia muscigena (Ach.) Poelt68. Pseudevernia intense (Nyl.) Hale & Culb.69. Psora nipponica (Zahlbr.) Gotth. Schneider70. Rhizoplaca chrysoleuca (Sm.) Zopf71. Solorina crocea (L.) Ach.72. Solorina octospora (Arnold) Arnold73. Sporastatia testudinea (Ach.) A. Massal.74. Tephromela armeniaca (DC.) Hertel & Rambold75. Unbilicaria deusta (L.) Baumg.Thank you Dr. St. Clair. <strong>The</strong>se specimens are nowin the <strong>CALS</strong> Herbarium Library. If you wish to borrowany of them, please contact Judy Robertson at. Postage is the responsibility ofthe borrower.See also specimen lists in <strong>CALS</strong> Bull. V<strong>10</strong>(1).(Announcements continued on p. 52)50