Wildlife Habitat Planning Strategies, Design ... - Sonoran Institute

Wildlife Habitat Planning Strategies, Design ... - Sonoran Institute

Wildlife Habitat Planning Strategies, Design ... - Sonoran Institute

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

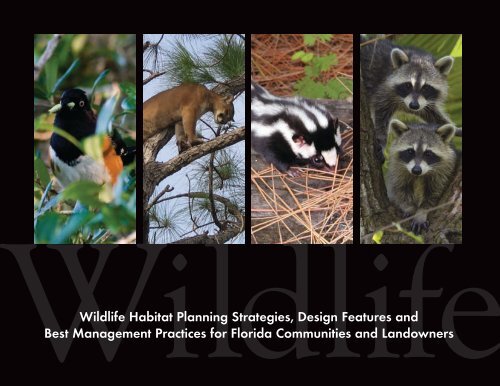

Headlinesubhead<strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Habitat</strong> <strong>Planning</strong> <strong>Strategies</strong>, <strong>Design</strong> Features andBest Management Practices for Florida Communities and Landowners

1 AcknowledgementsThis project was made possible by a grant from Florida’s<strong>Wildlife</strong> Legacy Initiative. The Legacy Initiative is a programof the Florida Fish and <strong>Wildlife</strong> Conservation Commission,with funding provided through State <strong>Wildlife</strong> Grants administeredby the US Fish and <strong>Wildlife</strong> Service. Additionalsupport was provided by the Florida <strong>Wildlife</strong> Federation,Jane’s Trust, The Martin Foundation, The BatchelorFoundation, the Elizabeth Ordway Dunn Foundation andthe Florida Department of Community Affairs.Special recognition is given to:Dan Pennington, 1000 Friends of Florida,research, writing and editingVivian Young, 1000 Friends of Florida,reviewJoanne Davis, 1000 Friends of Florida,photos and editing supportCharles Pattison, 1000 Friends of Florida,editing and content suggestionsKathleen Morris, 1000 Friends of Florida,reviewCatherine “Katie Anne” Donnelly,1000 Friends of Florida,research and writingKelly Duggar, 1000 Friends of Florida,research and writing,Kacy O'Sullivan, 1000 Friends of Florida,research and writing,Front Cover Photos Courtesy ofBird and Skunk: David Moynahan, FWC; Panther: Mark Lotz, FWC;Racoons: Charles Littlewood and the Florida <strong>Wildlife</strong> FederationBack Cover Photos Courtesy ofJoanne Davis, 1000 Friends of Florida1000 Friends of Florida would like to thank the following individuals for their generous contributions tothis document. This does not imply, however, that the following contributors endorse this document or itsrecommendation.Amy Knight and Jonathan Oetting, Florida Natural AreasInventory for significant input and editing of Chapter 4, “Dataand Analyses Development”Mark Easley of URS Corporation Southern and JoshuaBoan, Florida Department of Transportation, significant developmentof Chapter 8, “<strong>Planning</strong> for Transportation Facilities and<strong>Wildlife</strong>”Ronald Dodson, President and CEO, Audubon International,helping to write, edit and comment on Chapter 9, “<strong>Planning</strong><strong>Wildlife</strong>-Friendly Golf Courses in Florida”Benjamin Pennington, graphics and project web sitedevelopmentRebecca Eisman, Creative Endeavors, graphic designWill Abberger, Trust for Public Land • Dave Alden Sr., FWC • Matt Aresco, Nokuse Plantation • Ray Ashton, Ashton BiodiversityResearch & Preservation <strong>Institute</strong>, Inc. • Tom Beck, Wilson Miller, Inc. • Lisa B. Beever, PhD, AICP, Charlotte Harbor, National EstuaryProgram • Shane Belson, FWC • Anthony (Tony) Biblo, Leon County • Jeff Bielling, Alachua County • Dr. Reed Bowman,Archbold Biological Station • Tim Breault, FWC • Casey Bruni, Babcock Ranch • Mary Bryant, The Nature Conservancy • JohnBuss, City of Tallahassee • Billy Buzzett, The St. Joe Company • Gail Carmody, U S Fish and <strong>Wildlife</strong> Service • Gary Cochran,FWC • Vernon Compton, The Nature Conservancy • Courtney J. Conway, Arizona Cooperative Fish and <strong>Wildlife</strong> Research Unit •Marlene Conaway, KMC Consulting, Inc. • Ginger L. Corbin, U.S. Fish & <strong>Wildlife</strong> Service • John Cox, City of Tallahassee • SaraDavis, Florida <strong>Wildlife</strong> Federation • Richard Deadman, DCA • Craig Diamond, DCA • Eric Dodson, Audubon International •Tim Donovan, FWC • Eric Draper, Audubon of Florida • Mark Endries, FWC • Dr. James A. Farr, FDEP • Kim Fikoski,The Bonita Bay Group • Neil Fleckenstein, Tall Timbers Research Station • Charles Gauthier, DCA • Terry Gilbert, URSCorporation Southern • Greg Golgowski, The Harmony <strong>Institute</strong> • Stephen Gran, Manager, Hillsborough County • Kate Haley,FWC • Cathy Handrick, FWC • Bob Heeke, Suwannee River WMD • Rachel A. Herman, Sarasota County • Betsie Hiatt,Lee County Florida • William Timothy Hiers, The Old Collier Golf Club • Dr. Tom Hoctor, Geoplan, University of Florida • TedHoehn, FWC • Robert Hopper, South Florida WMD • David Hoppes, Glatting Jackson • Dr. Mark Hostetler, University of Florida• Greg Howe, City of Tampa • Anita L. Jenkins, Wilson Miller, Inc. • Bruce Johnson, Wilson Miller, Inc. • Rosalyn Johnson,University of Florida • Greg Kaufmann, FDEP • Debbie Keller, The Nature Conservancy • Carolyn Kindell, Florida Natural AreasInventory • Michael J. Kinnison, FDEP • Barbara Lenczewski, DCA • Kris Van Lengen, Bonita Bay Group • Douglas J. Levey,University of Florida • Katie Lewis, Florida Division of Forestry • Jay Liles, Florida <strong>Wildlife</strong> Federation • Jerrie Lindsey, FWC • BillLites, Glatting Jackson • Mark Lotz, FWC • Martin B Main, University of Florida • Laurie Macdonald, Defenders of <strong>Wildlife</strong> •Julia "Alex" Magee, Florida Chapter, American <strong>Planning</strong> Association • Jerry McPherson, Bonita Bay Group • Tricia Martin, TheNature Conservancy • Terri Mashour, St. Johns River WMD • Dr. Earl McCoy, University of South Florida • Kevin McGorty, TallTimbers Land Conservancy • Rebecca P. Meegan, Coastal Plains <strong>Institute</strong> and Land Conservancy • Julia Michalak, Defenders of<strong>Wildlife</strong> • Mary A. Mittiga, U.S. Fish and <strong>Wildlife</strong> Service • Rosi Mulholland, FDEP • Christine Mundy, St. Johns River WMD •Annette F. Nielsen, FDEP • Joe North, FDEP • Dr. Reed Noss, University of Central Florida • Cathy Olson, Lee County Florida •Matthew R. Osterhoudt, Sarasota County • John Outland, FDEP • Sarah Owen, AICP, Florida <strong>Wildlife</strong> Federation • HowardPardue, Florida Trail Association • Lorna Patrick, U.S. Fish and <strong>Wildlife</strong> Service • Nancy Payton, Florida <strong>Wildlife</strong> Federation •Jeffrey Pennington • Larry Peterson, Kitson & Partners • Paola Reason, Cresswell-Associates • Ann Redmond, BiologicalResearch Associates • Salvatore Riveccio, Florida <strong>Wildlife</strong> Federation • Preston T. Robertson, Florida <strong>Wildlife</strong> Federation •Christine Small, FWC • Scott Sanders, FWC • Keith Schue, The Nature Conservancy • Gregory Seamon, Wilson Miller Inc. •Vicki Sharpe, FDOT • Lora Silvanima, FWC • Daniel Smith, University of Central Florida • Joseph E. Smyth, FDEP, RainbowSprings State Park • Noah Standridge, Collier County • Hilary Swain, Archbold Biological Station • Kathleen Swanson, FWC •Vicki Tauxe, FDEP • Jon Thaxton, Sarasota County Commission • Walt Thomson, The Nature Conservancy • Sarah KeithValentine, City of Tallahassee • Keith Wiley, <strong>Wildlife</strong> Biologist, Hillsborough County • Michelle Willey, Kitson & Partners/Babcock Ranch• Donald Wishart, Glatting Jackson • Christopher Wrenn, Glatting Jackson • Julie Brashears Wraithmell, Audubon of Florida

Table of Contents 2List of Text Boxes by Chapter 3C HAPTER 1 — <strong>Design</strong>ing <strong>Wildlife</strong>-Friendly Communities in Florida 4• The Value of Green Infrastructure 6• A Tiered Approach to Conservation 8• The Top Tier: Toward a Statewide Green Infrastructure in Florida 8• Twenty-First Century Initiatives – Linkage Between Tiers 10• Promoting Green Infrastructure at the Middle Tier 11C HAPTER 2 — Community <strong>Wildlife</strong> and <strong>Habitat</strong> 13Conservation Framework and Principles• The North American Model of <strong>Wildlife</strong> Conservation 14• Ecological Principles for Managing Land Use 14• <strong>Design</strong>ing Functional Green Infrastructure for <strong>Wildlife</strong> 17• Merging Biology with <strong>Planning</strong> 21C HAPTER 3 — Envisioning and <strong>Planning</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> 22Friendly Communities• Goals for <strong>Planning</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong>-Friendly Communities 23• The First Steps 30C HAPTER 4 — Data and Analyses Development 35• Conducting a Birds-Eye-View Analysis 36• Taking Advantage of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) 36• Performing an Ecological Inventory 41• Developing Ecological Scoring Criteria and a Scoring System 42• Choosing From a Growing List of Analysis and Mapping Tools 42• Consulting Additional State and Regional <strong>Wildlife</strong> and <strong>Habitat</strong> Data Sources 45C HAPTER 5 — The Florida <strong>Wildlife</strong>-Friendly Toolbox 48• The Local Comprehensive Plan 49• Developments of Regional Impact 51• Sector Plans 54• Rural Land Stewardship Areas 57• Special Large Property Opportunities 61C HAPTER 6 — An Implementation Toolbox for Green Infrastructure 64• Easements 65• Subdivisions and Conservation Subdivisions 69• Upland <strong>Habitat</strong> Protection Ordinances 72• <strong>Habitat</strong> Conservation Plans 75• Mitigation and Restoration Plans 77• Federal, State and WMD Mitigation Banks and Parks in Florida 81C HAPTER 7 — Management and <strong>Design</strong> Factors 83• Managing for Fire 84• <strong>Wildlife</strong>-Friendly Lighting 89• <strong>Planning</strong> Stormwater Management and Waterbody Buffers for <strong>Wildlife</strong> Value 94• Ephemeral Wetlands and Pond Landscapes 95• <strong>Planning</strong> for Supportive Long-Term Behavior in a <strong>Wildlife</strong>-Friendly Community 97C HAPTER 8 — <strong>Planning</strong> for Transportation 99Facilities and <strong>Wildlife</strong>• Guidelines for Accommodating <strong>Wildlife</strong> 100• Identifying the Need and Goals for <strong>Wildlife</strong> Linkages 101• <strong>Design</strong> Considerations for <strong>Wildlife</strong> Linkages 104• Specific <strong>Design</strong> Environmental Factors of <strong>Wildlife</strong> Linkages 109• Linkages for ETDM Projects 115• Linkages for Non-ETDM Projects 117• Road and Highway Related Stormwater Facilities 118C HAPTER 9 — <strong>Planning</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong>-Friendly Golf Courses in Florida 120• <strong>Planning</strong> for <strong>Habitat</strong> and <strong>Wildlife</strong> Basics 121• <strong>Planning</strong> for the Birds 129• Integrate Fire Dependent Natural Communities and Golf Courses 131• Buffers for Waterbodies and Wetlands 131• Golf Course Stormwater Treatment Trains and Capturing <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Habitat</strong> Value 132• Engage Golf Course Staff and Golfers 133• Summary 133C HAPTER 10 — <strong>Wildlife</strong> Conservation and Restoration in 135Agricultural and Rural Areas• Starting Points 136• Federally Funded Farm Bill Programs 138• Non-Farm Bill Federal Initiatives 142• State Funded <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Habitat</strong> Cost-Share Programs 144• Agricultural Conservation Easements and Land Donations 145• Rural Land Stewardship Program 148• Conservation and Restoration Techniques 148• Agritourism Potential in Florida’s Rural and Agricultural Lands 149APPENDIX 1 — Sample Comprehensive Plan Goals, 151Objectives and PoliciesAPPENDIX II — References 164

3Informational Text Boxes by ChapterC HAPTER 1 — <strong>Design</strong>ing <strong>Wildlife</strong>-Friendly Communities in Florida• Important Ecosystem “Services” of Green Infrastructure• The Florida Fish and <strong>Wildlife</strong> Conservation CommissionC HAPTER 2 — Community <strong>Wildlife</strong> and <strong>Habitat</strong> Conservation Frameworkand Principles• What is the North American Model of <strong>Wildlife</strong> Conservation?• <strong>Wildlife</strong> Corridors Benefit Plant Biodiversity• Considerations of Corridor <strong>Design</strong>C HAPTER 3 — Envisioning and <strong>Planning</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> Friendly Communities• Managed Environmental Lands Add to the Quality of Life and Real Market Value• The Pattern of Land Development Relative to <strong>Habitat</strong> Spatial Problems• The Good Neighbor Approach: Oscar Scherer State Park in Sarasota County• Address All Phases of a Development• Capital Cascades Greenway, Tallahassee: Integrating “Hard” and “Green” Infrastructures• Volusia Forever ProgramC HAPTER 4 — Data and Analyses Development• Scale and Birds-Eye-View Tools• <strong>Wildlife</strong> and <strong>Habitat</strong> Information and Analyses Service Providers• Mapping and Analysis Tools• Additional State and Regional <strong>Wildlife</strong> and <strong>Habitat</strong> Data SourcesC HAPTER 5 — The Florida <strong>Wildlife</strong>-Friendly Toolbox• The West Bay Sector Plan• <strong>Wildlife</strong> Considerate BridgingC HAPTER 6 — An Implementation Toolbox for Green Infrastructure• Tall Timbers Land Conservancy• Upland Ordinances in Tampa and Martin County• Sarasota County HCP for Scrub-Jays• Lee County Capital Improvements Plan• Island Park Regional Mitigation Site at Estero Marsh PreserveC HAPTER 7 — Management and <strong>Design</strong> Factors• Fire in the Suburbs: Ecological Impacts of Prescribed Fire in Small Remnants of LongleafPine Sandhill• Lighting for Conservation of Protected Coastal Species• Desired <strong>Planning</strong>, <strong>Design</strong> and Management for Ephemeral Wetlands and PondsC HAPTER 8 — <strong>Planning</strong> for Transportation Facilities and <strong>Wildlife</strong>• <strong>Wildlife</strong> Crossings in Florida• <strong>Planning</strong> for a Eglin-Nokuse <strong>Wildlife</strong> Linkage• Intersecting Paths: Linear <strong>Habitat</strong>s and Roadways• Modeling Tools for <strong>Wildlife</strong> Crossings• Longer Bridge Spans Provide More Space for <strong>Wildlife</strong> Passage• <strong>Design</strong>, Installation, and Monitoring of Safe Crossing Points for Bats in Wales• Integrating Transportation and Stormwater Facility <strong>Planning</strong> with <strong>Wildlife</strong>-FriendlyCommunity <strong>Planning</strong>C HAPTER 9 — <strong>Planning</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong>-Friendly Golf Courses in Florida• Sustaining Fox Squirrels, As Is True Of Many Species, May Take A Little <strong>Planning</strong>• Twin Eagles Golf Course Community and Linkage to the Corkscrew Regional Ecosystem(CREW)• Quick Basic <strong>Planning</strong> for <strong>Wildlife</strong> Features• Audubon International’s Programs to Help Golf Courses and Communities be <strong>Wildlife</strong>-Friendly• University Of Florida IFAS Study Says Golf Is for the Birds• Golf Courses and <strong>Wildlife</strong> Friendly Environmental Practices• Encouraging Burrowing Owls at Golf CoursesC HAPTER 10 — <strong>Wildlife</strong> Conservation and Restoration in Agriculturaland Rural Areas• Hillsborough County: Proactive <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Habitat</strong> Protection and Agricultural Viability• Conservation Plans of Operation and <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Habitat</strong> Development Plans• Florida’s Federal Trust Species• The Rural and Family Lands Protection Act: Funding for Protection of Agriculture and NaturalResources in Florida• Babcock Ranch: Ecotourism Opportunities in Conjunction with Agriculture and SmartDevelopment

Chapter 1<strong>Design</strong>ing <strong>Wildlife</strong>-Friendly Communities in Florida4Photo Courtesy of Joanne Davis, 1000 Friends of Florida

5Chapter 1<strong>Design</strong>ing <strong>Wildlife</strong>-Friendly Communities in FloridaP O P U L A T I O NF O R E C A S T17.9 Million35.8 Million2005 2060Florida 2060:A Research Project of1000 Friends of FloridaBoth geologically and biologically, Florida is a very distinctregion of the United States. Southern Florida has a subtropicalclimate which transitions through the central part of the state to amore temperate climate in North Florida. Due to its peninsulargeography and this range of climates, Florida supports in excessof 700 terrestrial animals, 200 freshwater fish, and 1,000 marinefish, as well as numerous other aquatic and marine vertebrates,and many thousands of terrestrial insects and other invertebrates.While many of these species can be found elsewhere in NorthAmerica, there are also a number that are unique to Florida.As with so many other places in the world, Florida is facingrapid growth, which is resulting in major changes in land use andrelated impacts on the state’s natural resources. Florida’s populationgrew from approximately 3 million people in 1950 to morethan 18 million in 2005. Moderate projections indicate thatFlorida’s population could increase to 36 million by the year2060. If the historic patterns of development continue over thenext 50 years, Florida could stand to convert 7 million acres ofadditional land from rural to urban uses, including 2.7 millionacres of native habitat.Adding millions of new residents to this state will only serve toheighten the competition between wildlife and humans for land,water, food and air resources. Given the ability of humans toreshape entire landscapes to meet their needs, there is no doubtthat wildlife will not fare well. In the face of this unrelenting growthand development, it is imperative that Floridians recognize theneed to serve as wise stewards of the land, water, and theintertwined ecosystems.While protecting large tracts of undisturbed landscapes isbest from a wildlife perspective, unfortunately that is increasinglyimpossible in Florida. Future efforts, then, must include strategiesto maximize habitat within and adjacent to developed, managed,or otherwise human-influenced landscapes. The goal of thismanual is to share Florida-specific wildlife conservation toolsthat can be used by community planners, landscape architects,B E F O R EA F T E RFlorida 2060: A Research Project of 1000 Friends of Florida

7Chapter 1<strong>Design</strong>ing <strong>Wildlife</strong>-Friendly Communities in FloridaMany smaller creatures —from newts to eagles — canfinds sufficient habitat tosurvive in our suburban andurban environments if werecognize their basic needsand work to integratethem into the developedlandscape.IMPORTANT ECOSYSTEM “SERVICES” OFGREEN INFRASTRUCTURE•Sustain biodiversity.•Protect areas from impacts of flooding, storm damage ordrought.•Protect stream and river channels and coastal shores fromerosion.•Provide a carbon sink. As an example, 100 acres of woodlandcan absorb emissions equivalent to 100 family cars.•Offer pollution control. Vegetation has a significant capacityto attenuate noise and filter air pollution from motor vehicles.Wetland ecosystems are also effective in filtering pollutedrun-off and sewage.•Provide natural “air conditioning.” A single large tree can beequivalent to five room air conditioners and will supply enoughoxygen for ten people.•Provide microclimate control by providing shade, hold inhumidity and blocking winds and air currents.•Protect people from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet rays.•Cycle and move nutrients and detoxify and decomposewastes.Thoughtful planning at the community level can lessen theimpacts from these stressors. Many smaller creatures- — fromnewts to eagles — can finds sufficient habitat to survive in oursuburban and urban environments if we recognize their basicneeds and work to integrate them into the developed landscape.To promote sustained biodiversity, a community first must identifylocal wildlife and habitats, and then ensure that basic necessitiesfor survival are sustained, including food, cover, water, livingand reproductive space, and limits on disturbances.•Control agricultural pests and regulate disease carryingorganisms.•Generate and preserve soils and renew their fertility.•Disperse seeds and pollinate crops and natural vegetation.•Contribute to the health and wellbeing of our citizens.Accessible green space and natural habitats createopportunities for recreation and exercise, and studies haveshown that this increases our creative play, social skills andconcentration span.•Contribute to a community’s social cohesion. The activeuse of greenspaces, including streets and communalspaces, can encourage greater social interaction andcontribute to a lively public realm. Participation in thedesign and stewardship of green space can help strengthencommunities.•Enhance economic value. Natural greenspaces canincrease property values, reduce management overheads,and reduce healthcare costs.Adapted from: Ecosystem Services, Ecological Societyof America, 2000, at www.esa.org; and, Biodiversity by<strong>Design</strong>: A Guide for Sustainable Communities, Town andCountry <strong>Planning</strong> Association (TCPA), England, 2004.At the same time, ecosystems provide many “services” withlittle or no capital costs involved. These can range from protectingareas from flooding, to providing natural “air conditioning,”to offering pollution control. The ecological services of greeninfrastructure can be conserved and enhanced through carefulplanning. Extending the green infrastructure network to adjacentcommunities and regional, state or national managed environmentallands is often very possible and can further enhance thevalue and utility of the services.

Chapter 1<strong>Design</strong>ing <strong>Wildlife</strong>-Friendly Communities in Florida8In addition to the ecosystem service values, a community cangain monetary value from carefully integrating habitat into itsjurisdiction. The 2006 total retail sales from wildlife viewing inFlorida were estimated at $3.1 billion ($2.4 billion by residentsand $653.3 million by nonresidents). Since 2001, expendituresin Florida for wildlife viewing have almost doubled ($1.6 billionin 2001). These 2006 expenditures support a total economiceffect to the Florida economy of $5.248 billion. The 2006economic impact of wildlife viewing in Florida is summarizedbelow. (Information from, The 2006 Economic Benefits of<strong>Wildlife</strong> Viewing in Florida, Southwick Associates, Inc, 2008)2006 ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF WILDLIFE VIEWING IN FLORIDAResident Nonresident TotalRetail sales $2.428 billion $653.3 million $3.081 billionSalaries & wages $1.204 billion $391.8 million $1.595 billionFull & part-time jobs 38,069 13,298 51,367Tax revenuesState sales tax $243.1 million $69.7 million $312.8 millionFederal income tax $292.5 million $92.8 million $385.3 millionTotal economic effect $4.078 billion $1.170 billion $5.248 billionA TIERED APPROAC H TO CONSERVATIONOver the past few decades, a three-tiered approach to landconservation has evolved in Florida. The top tier includes largestatewide and regional land acquisition and protection effortsintended to establish “islands” of protected and relatively intacthabitats which are linked, where possible, by ecological greenways.These efforts have laid the foundation for a statewidegreen infrastructure in Florida.The bottom tier includes programs directed at protecting habitatswithin neighborhoods and in backyards. Often grassroots innature, these include the University of Florida’s Florida Yards andNeighborhoods program and the National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Federation’sBackyard <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Habitat</strong> Program, both of which are targetedat individual citizens, families, and/or neighborhoods.The middle tier focuses on creating regional and communitywidegreen infrastructure to promote conservation within largelandholdings, large developments, and neighborhoods. This tieris perhaps the least evolved of the three, but includes betterland use planning, development design, and best managementpractices by both the public and private sectors. It is the middletier at which most development approvals are issued. This tieroffers the greatest potential for better integration of human andwildlife habitat.THE TOP TIER: TOWARD A STATEWIDEGREEN INFRASTRUCTURE IN FLORIDABefore the phrase “green infrastructure” had even been coined,Florida launched an ambitious series of land acquisition and conservationplanning projects which laid the foundation for creatingFlorida’s existing green infrastructure. Building on earlier stateland acquisition programs, in 1990 Florida established thePreservation 2000 program. This 10-year program raised $3billion, and protected 1,781,489 acres of environmentallysensitive land. In 1999, the Florida Legislature created FloridaForever, also designed to dedicate $3 billion to land acquisitionover the following decade. As of December 2006, another535,643 acres of environmentally sensitive land had beenprotected through this effort.As these major land acquisition programs evolved, there wasa growing awareness of the need to be more strategic in landacquisition, and a series of efforts were launched in the 1990s.In 1994, researchers from the Florida Fish and <strong>Wildlife</strong> ConservationCommission (FWC) completed a very important report, Closingthe Gaps in Florida's <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Habitat</strong> Conservation. Thiscornerstone report used a geographic information systemapproach to identify key habitat areas to conserve in orderOver the past few decades,a tiered approach to landconservation has evolvedin Florida. The top tierincludes large statewide andregional land acquisition andprotection efforts intendedto establish “islands” ofprotected and relativelyintact habitats which arelinked, where possible, byecological greenways.

9Chapter 1<strong>Design</strong>ing <strong>Wildlife</strong>-Friendly Communities in FloridaAs part of this effort, theUniversity of Florida undertookthe Florida EcologicalNetwork Project, andcompleted the first phasein 1998. It used GIS datato identify large connectedecologically significantareas of statewide significance.The goal was tocreate a system of interconnectedlands protected fortheir ecological value tonative wildlife and plants,or for their provision ofecological services suchas water quality protectionand flood prevention.THE FLORIDA FISH AND WILDLIFECONSERVATION COMMISSIONThe Florida Constitution vests the Florida Fish and <strong>Wildlife</strong>Conservation Commission with regulatory and executivepowers of the state with respect to wild animal life. Inthe area of regulating hunting and specific wild animalmanagement actions, the principle of state wildlife primacyover local regulation is well established. Courts willinvalidate local ordinances in clear conflict with stateauthority on hunting and wildlife. On the other hand,when such regulations are not in clear conflict, the courtswill often seek to interpret local regulations and state lawharmoniously.By contrast, actions affecting habitat and biodiversityare not yet an organizing concept for federal or stateregulatory programs. Local governments have considerablediscretion to define their planning, managementand regulatory niche. So, for example, a local actionprescribing gopher tortoise protection or mitigation in amanner that conflicts with state regulations, would likelybe invalidated on preemption grounds, whereas a localregulation directed more generally to gopher tortoisehabitat might survive such a challenge. A local regulationdirected even more broadly to protection of entirenatural vegetative community types or ecosystems wouldcertainly not be preempted on these grounds.The Florida Ecological Greenway NetworkPhoto Courtesy of GeoPlan Center Graphic Courtesy of Noss & Cooperrider, 1994

Chapter 1<strong>Design</strong>ing <strong>Wildlife</strong>-Friendly Communities in Florida10to maintain key components of the state’s biological diversity.These areas, known as Strategic <strong>Habitat</strong> Conservation Areas(SHCA), continue to serve as a foundation for conservationplanning in Florida.Around the same time, the seed was being planted for Florida’sgreenways network. In the early 1990s, 1000 Friends of Floridaand The Conservation Fund launched a coordinated effort toidentify and protect a linked network of natural areas to accomplishboth ecological and recreation needs. This evolved into theFlorida Statewide Greenways <strong>Planning</strong> Project, established underthe Florida Department of Environmental Protection in 1990s.As part of this effort, the University of Florida undertook theFlorida Ecological Network Project, and completed the firstphase in 1998. It used GIS data to identify large connectedecologically significant areas of statewide significance. Thegoal was to create a system of interconnected lands protectedfor their ecological value to native wildlife and plants, or for theirprovision of ecological services such as water quality protectionand flood prevention. It helped to form the basis of the FloridaGreenways and Trails System and supports ecological connectivityconservation directed at priority landscape linkages. Thenetwork has been updated several times (most recently in 2004),primarily to take advantage of new data and methods andremove lands lost to development.The result of this process was an updated Florida EcologicalGreenways Network. This network provides a linked statewidereserve system containing most of each major ecologicalcommunity and most known occurrences of rare species. Itrepresents significant progress toward a more integratedapproach to biodiversity conservation in Florida.In 2000, the Florida Natural Areas Inventory released itsFlorida Conservation Needs Assessment. Prepared on behalf ofthe Florida Forever Advisory Council, this report focused on thegeographic distribution of natural resources, or resources-basedland uses (such as sustainable forestry) to guide conservationdecision making related to Florida’s second major state landacquisition program, Florida Forever.T WENT Y-FIRST CENTURY INITIATIVES —LINKAGE BET WEEN TIERSA new round of conservation planning has now begun,building on these earlier efforts. Begun in 2004 as part of anation-wide effort, the Florida Fish and <strong>Wildlife</strong> ConservationCommission’s <strong>Wildlife</strong> Legacy Initiative is an action plan toaddress the long-term conservation of all native wildlife and theplaces they live. The stated goal is to “prevent wildlife frombecoming endangered before they become more rare and costlyto protect.” The initiative focuses on creating partnerships tobetter protect Florida’s wildlife and their habitats. As part ofthe initiative, the Commission has created Florida’s <strong>Wildlife</strong>Conservation Strategy. This updates existing conservationplans from the last 30 years into a single state wildlife actionplan, providing a platform for proactive conservation. Florida’sState <strong>Wildlife</strong> Grants Program provides funds to assist withimplementing the Strategy.One outgrowth of the <strong>Wildlife</strong> Conservation Strategy is theCooperative Conservation Blueprint. The Florida Fish and <strong>Wildlife</strong>Conservation Commission, The Century Commission for aSustainable Florida and Defenders of <strong>Wildlife</strong> are providing leadershipon this project, the goal of which is to build agreementbetween government and private interests on using commonpriorities as the basis for state-wide land use decisions. Whencompleted, it will include a fully unified set of GeographicInformation System (GIS) data layers of conservation anddevelopment lands that will be available to all Floridians, anda package of recommended landowner incentives to applythe strategies statewide.A new round of conservationplanning has now begun,building on earlier efforts.Begun in 2004 as partof a nation-wide effort, theFlorida Fish and <strong>Wildlife</strong>Conservation Commission’s<strong>Wildlife</strong> Legacy Initiative isan action plan to addressthe long-term conservationof all native wildlife and theplaces they live.

11Chapter 1<strong>Design</strong>ing <strong>Wildlife</strong>-Friendly Communities in FloridaThe challenge for Floridacommunities is to craftsituations to healthily maintainthe maximum number ofwildlife species. This isbecoming increasinglydifficult as sprawlingdevelopment has pushedmuch wildlife to the wildernessedge. Additionally,human-to-wildlife contactis escalating, includingnegative interactions.The Florida Fish and <strong>Wildlife</strong> Conservation Commissionupdated Closing the Gaps in the 2006 report, <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Habitat</strong>Conservation Needs in Florida: Updated Recommendations forStrategic <strong>Habitat</strong> Conservation Areas. The report details anassessment to determine the protection afforded to focal species,including many rare and imperiled species, on existing conservationlands in Florida and to identify important habitat areasin Florida that have no conservation protection. These areas,known as Strategic <strong>Habitat</strong> Conservation Areas, serve as afoundation for conservation planning in Florida and depict theneed for species protection through habitat conservation. Thiswas further enhanced with development of The Integrated <strong>Wildlife</strong><strong>Habitat</strong> Ranking System. The Integrated <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Habitat</strong>Ranking System (IWHRS) ranks the Florida landscape basedupon the habitat needs of wildlife as a way to identify ecologicallysignificant lands in the state, and to assess the potentialimpacts of land development projects. The IWHRS is providedas part of the Commission’s continuing technical assistance tovarious local, regional, state, and federal agencies, and entitiesinterested in wildlife needs and conservation in order to: (1) determineways to avoid or minimize project impacts by evaluatingalternative placements, alignments, and transportation corridorsduring early planning stages, (2) assess direct, secondary, andcumulative impacts to habitat and wildlife resources, and (3)identify appropriate parcels for public land acquisition for wetlandand upland habitat mitigation purposes.The Integrated <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Habitat</strong> Ranking System, 2007.These resources and land acquisition funding sources havegone a long way toward creating a statewide green infrastructurenetwork, and can serve as valuable tools which can complementand/or leverage activities at the regional and locallevels. Building on these efforts is the Critical Lands/WatersIdentification Project (CLIP) sponsored by the Century Commissionfor a Sustainable Florida. The Century Commission was formedby the Florida Legislature in 2005 and is tasked with: envisioningFlorida’s future by looking out 25 and 50 years; making recommendationsto the Governor and Legislature regarding how theyshould address the impacts of population growth; and establishinga place where the "best community-building ideas" canbe studied and shared for the benefit of all Floridians. CLIP is aprocess to identify Florida's "must save" environmental treasuresand critical green infrastructure (see Chapter 4 for more informationon CLIP).PROMOTING GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE ATTHE MIDDLE TIERWhile much has been accomplished at the top and bottomtiers, a great deal still remains to be done at the regional andcommunity levels in Florida to conserve Florida’s wildlife andhabitats. Very little will happen at the middle tier to conserve,integrate or enhance wildlife habitat unless people plan, designand manage for this purpose. Fortunately, more and more com-Florida Fish and <strong>Wildlife</strong> Conservation Commission

Chapter 1<strong>Design</strong>ing <strong>Wildlife</strong>-Friendly Communities in Florida12munities, landowners and developers are beginning to integratewildlife features into their local landscapes.The challenge for Florida communities is to craft situations tohealthily maintain the maximum number of wildlife species. Thisis becoming increasingly difficult as sprawling development haspushed much wildlife aside. Additionally, human-to-wildlifecontact is escalating, including negative interactions. The publicsafety threat of large predators has been unintentionally marginalized(alligators, panthers and bears do kill people). Whilethere is, perhaps, a great appreciation of wildlife today, there isalso a growing “Not In My Back Yard” — or NIMBY--reactionthat wants wildlife to be put back “where it belongs.” Betterplanning, design, and use of best management practices at thelocal community level need to be used to help address theseissues.A new wildlife and habitat paradigm needs to be encouraged.It need not be a revolution, but instead, it can evolve from wherewe have been, using many of the same strategies, albeit ina new context. Keys to success will include using science toframe the issues, involving the public in making the decisions,and garnering sufficient support to fund the needed actions.Photo Courtesy David Moynahan PhotographySignage can help educatethe public regarding wildlifeconservation efforts.Photo Courtesy of Dan Pennington and JoanneDavis, 1000 Friends of Florida

13Chapter 2Community <strong>Wildlife</strong> and <strong>Habitat</strong> Conservation Framework and PrinciplesPhoto Courtesy of David Moynahan Photography

Chapter 2Community <strong>Wildlife</strong> and <strong>Habitat</strong> Conservation Framework and Principles14Numerous models, frameworks and principles have helpedto shape approaches to wildlife conservation in the UnitedStates. From the original North American Model of <strong>Wildlife</strong>Conversation to modern ecosystem management, wildlifeconservation has evolved to include the seminal works of E.O.Wilson, Michael E. Soule, Richard Forman, Larry Harris, ReedNoss and others. To meet the future challenge of sustainingwildlife, habitat and ecological systems, a wildlife and habitatconservation framework must be incorporated into land useplanning and land-management decisions.THE NORTH AMERIC AN MODEL OFWILDLIFE CONSERVATIONUnderpinning the approach to wildlife management in theUnited States and Canada is the North American Model of<strong>Wildlife</strong> Conservation. This model has evolved over the last175 years and is based on two basic principles — that our fishand wildlife belong to all citizens of North America, and thatthey should be managed in such a way that their populationswill be sustained forever.It is rooted in the Public Trust Doctrine, derived from the 1842U.S. Supreme Court case, Martin v. Wadell, where wildlifewas held in common ownership by the state for the benefit ofall. Thanks to this foundation, modern wildlife managementhas been hugely successful in restoring populations of gameanimals and their habitats. Species once generally regardedas nuisances, such as alligators, eagles and bears, are nowrevered by the public and have become icons for wild lands.ECOLOGIC AL PRINCIPLES FOR MANAGINGL AND USEThe Ecological Society of America, a scientific non-profit establishedin 1915, released a report in 2000 entitled EcologicalPrinciples for Managing Land Use. This includes a series offive ecological principles for managing land use to ensure thatthe “fundamental processes of Earth’s ecosystems are sustained.”According to the society, the responses of the land to changesin use and management by people depend on expressions ofthese fundamental principles:1. Time Principle — In order to effectively analyze the effectsof land use, it must be recognized that ecological processesoccur within a temporal setting, and change over time. Inother words, the full ecological effects of human activitiesoften are not seen for many years, and the imprint of a landuse may persist for a long time, constraining future land usefor decades or centuries even after it ceases. Also under thetime principle, given time, disturbed ecosystem componentscan often recover. This should guide a community to takea long view when striving to create and maintain habitatlinkage corridors.2. Species Principle — Individual species and networks ofinteracting species have strong and far-reaching effects onecological processes. These focal species affect ecologicalsystems in diverse ways:•Indicator species tell us about the status of other speciesand key habitats or the impacts of a stressor. Manyamphibians and bird species are often considered indicatorspecies. For example the Green Treefrog (Hyla cinerea)and Squirrel Treefrog (Hyla squirella) in Florida have servedthis function. Native indicator species are often used toassess system-wide ecological responses to land usechanges, analogous to the canary in the coal mine.Underpinning the approachto wildlife management inthe United States andCanada is the NorthAmerican Model of <strong>Wildlife</strong>Conservation. This modelhas evolved over the last175 years and is based ontwo basic principles — thatour fish and wildlife belongto all citizens of NorthAmerica, and that theyshould be managed in sucha way that their populationswill be sustained forever.

15Chapter 2Community <strong>Wildlife</strong> and <strong>Habitat</strong> Conservation Framework and PrinciplesIndividual species andnetworks of interactingspecies have strong andfar-reaching effects onecological processes.These focal species affectecological systems indiverse ways.WHAT IS THE NORTH AMERIC AN MODELOF WILDLIFE CONSERVATION?Derived from our rich national hunting heritage, the NorthAmerican Model of <strong>Wildlife</strong> Conservation includes a set ofguidelines known as the “Seven Sisters for Conservation.”These serve as a basis for the conservation of both gameand non-game wildlife. They are:1. <strong>Wildlife</strong> is a public resource. It is held in commonownership by the state for the benefit of all people.2. Markets for trade in wildlife have been eliminatedor publicly managed. Generally, it’s illegal to buyand sell meat and parts of game and non-game species.3. Allocation of wildlife by law. States allocate wildlifeuse and taking by law, not by market pressures, landownership or special privilege. The process fosters publicinvolvement in managing wildlife.4. <strong>Wildlife</strong> can only be killed for a legitimate purpose.The law prohibits killing wildlife for frivolous reasons.5. <strong>Wildlife</strong> species are considered an internationalresource. Some species, such as migratory birds,transcend boundaries and one country’s managementcan easily affect a species in another country.6. Science is the proper tool for discharge of wild--life policy. The concept of science-based, professionalwild-life management is central.7. The democracy of hunting. In the European model,wildlife was allocated by land ownership and privilege. InNorth America, anyone in good standing can participate.The enduring strategies of the North American Modelinclude collaboration, partnerships, coalition building, professionaldevelopment, science, political savvy, persistence,and open-minded approaches.Source: “The Zoo without Bars, <strong>Wildlife</strong> Management forthe New Millennium”, Tim Breault, FFWCC, 2007.Photo Courtesy of David Moynahan Photography

Chapter 2Community <strong>Wildlife</strong> and <strong>Habitat</strong> Conservation Framework and Principles16•Keystone species have greater effects on ecologicalprocesses than would be predicted from their abundanceor biomass alone. In Florida, the gopher tortoise can beconsidered a keystone species.•Ecological engineers alter the habitat and, in doing so,modify the fates and opportunities of other species. Floridaexamples include the gopher tortoise and beaver.•Umbrella species either have large area requirementsor use multiple habitats and thus overlap the habitatrequirements of many other species. These can includethe panther and black bear.•Link species are those that perform an important ecologicalfunction or provide critical links for energy transfer withinor across complex food webs. Their removal from thesystem would affect one or multiple other species (e.g.,alligators and their role in the creation and maintenanceof ponds and wet areas during times of drought).3. Place Principle — Each site or region has a unique setof organisms and aboiotic conditions influencing andconstraining ecological processes.4. Disturbance Principle — Disturbances are important andubiquitous events whose effects may strongly influence population,community, and ecosystem dynamics. Disturbances caninclude natural events such as fires, drought and inundation, aswell as man-made disturbances including building roads,drawing down water tables, adding night lighting, or clearingland for development. Land use changes that alter naturaldisturbance regimes or initiate new disturbances are likely tocause changes in species abundance and distribution, communitycomposition, and ecosystem function.5. Landscape Principle — The size, shape, and spatial relationshipsof habitat patches on the landscape affect thestructure and function of ecosystems. Settlement patterns andland use decisions fragment the landscape and alter naturalland cover patterns. <strong>Habitat</strong> fragmentation decreases in thesize or wholeness of habitat patches and can increases inthe distance between habitat patches of the same type. Thiscan greatly reduce or eliminate populations of organisms, aswell as alter local ecosystem processes.Two other commonly accepted principles can perhaps beadded to this list of ecological principles (Dr. T. Hoctor,University of Florida, Geoplan):1. Ecological Complexity Principle — Ecosystems are notonly more complex then we think, but they may be morecomplex than we can think.Link species are those thatperform an importantecological function orprovide critical links forenergy transfer within oracross complex food webs.Their removal from the systemwould affect one or multipleother species (e.g., alligatorsand their role in the creationand maintenance of pondsand wet areas during timesof drought).Photo Courtesy of: Panther in Tree: Mark Lotz,FWC; Manatee in Canel: Eric Weber; Cow-Nosed Rays: Jeffrey Pennington; Snake: MattAresco

17Chapter 2Community <strong>Wildlife</strong> and <strong>Habitat</strong> Conservation Framework and PrinciplesIn Florida, some commonplaceapplications includeavoiding sprawling developmentand minimizingthe need for new roadsand other infrastructure.Additionally, when planningnew or retrofitting olddevelopment, it is importantto maintain or restorelinkages between sizablepatches of critical areas,and minimize or compensatefor the effects of developmenton ecological processes.2. Precautionary Principle — When there is uncertainty inland planning and wildlife and habitat conservation needs(which is most always), err toward protecting too muchinstead of too little. It is difficult and, at times, impossible torestore what has been lost.The Ecological Principles for Managing Land Use report alsoincludes a series of guidelines to incorporate ecological principlesinto land use decision making. The society recommendsthat land managers should:1. Examine the impacts of local decisions in a regional context.2. Plan for long-term change and unexpected events.3. Preserve rare landscape elements and associated species.4. Avoid land uses that deplete natural resources.5. Retain large contiguous or connected areas that containcritical habitats.6. Minimize the introduction and spread of nonnative species.7. Avoid or compensate for the effects of development onecological processes.8. Implement land-use and management practices that arecompatible with the natural potential of the area.In Florida, some commonplace applications include avoidingsprawling development and minimizing the need for new roadsand other infrastructure. Additionally, when planning new or retrofittingold development, it is important to maintain or restore linkagesbetween sizable patches of critical areas, and minimize or compensatefor the effects of development on ecological processes.DESIGNING FUNCTIONAL GREENINFRASTRUCTURE FOR WILDLIFEOur understanding of how to design wildlife-sustainable greeninfrastructure has its roots in a field known as island biogeography.Scientists observed that islands and peninsulas around theworld generally hold fewer species than expected whencompared to larger land masses. In their 1967 book, TheTheory of Island Biogeography, Edward O. Wilson and R.H.MacArthur propounded that the number of species found on anisland is determined by the distance from the mainland and thesize of the island, both of which would affect the rate of extinctionon and immigration to the island. Thus, a larger island closerto the mainland would likely have a greater diversity of speciesthan a smaller island farther from the mainland. Later studieshave expanded this to include that habitat diversity may be as,or more important than, the island’s size.An “island” can include any area of habitat that is surroundedby areas unsuitable for species on the island — including forestfragments, reserves and national parks surrounded by humanalteredlandscapes. This theory has proven remarkably accurateand has become an important foundation of modern landscapeecology. It also has led to development of the habitat corridoras a conservation tool to increase the connections betweenhabitat islands. These corridors can increase the movementof species between protected lands, helping to increase thenumber of species that can be supported.As landowners and local governments work together to createwildlife-friendly communities, it is important to understand moreabout the key concepts of patches, corridors, and edge effectswhich have evolved out of the study of biogeography. In his1995 book, Land Mosaics: The Ecology of Landscapes andRegions, noted Harvard Professor of Landscape ArchitectureRichard T.T. Forman described these important concepts ingreat detail.Patches — Forman defined a patch as a relatively homogenousarea that differs from its surrounding. From a wildlife perspective,patches are discrete landscape areas which offer better survivalprospects for wildlife, and regularly meet living prerequisites,including food, cover, water, living space, and limits on disturbances.Human impacts tend to lead to smaller and smaller

Chapter 2Community <strong>Wildlife</strong> and <strong>Habitat</strong> Conservation Framework and Principles18Graphics by Benjamin PenningtonABA) A small patch of habitat, cut-off from similar habitat areas, is depleted overtimeof wildlife and the opportunities for wildlife replenishment.; B) <strong>Habitat</strong> patchshape, size and connectivity can be important to wildlife survival. A large patchwith a coherent interior environment is best for many species. Several smaller habitatpatches with reasonable cross-connections may sustain desired wildlife.Several patches in relative close proximity are often better than stretched-out orsmaller chopped-up patches that lose unique interior habitats and micro climates.patches — or islands—of living space. Patches are furtherfragmented by development impacts including roads andsubdivisions. Agricultural practices leading to increased fragmentationinclude tilling for crops, burning, over and under watering,dosing with fertilizers and pesticides, and livestock ranging.<strong>Habitat</strong> fragmentation can lead to changes in physical factors,shifts in habitat use, altered population dynamics, and changesin species composition. Patch (or island) size has been identifiedas a major feature influencing the health and sustainability of plantand animal communities (Monica Bond, Center for BiologicalDiversity, Principles of <strong>Wildlife</strong> Corridor <strong>Design</strong>, 2003). Thereare a few exceptions. For example, raccoons and mockingbirdshave adapted to human-dominated landscapes anddiscontinuous habitats.The composition and diversity of patches, as well as theirspatial relationship with one another, will determine the relativesustainability of a community’s green infrastructure. Patchesmay or may not be self evident, so it is important to haveexperienced input into the design of the community plan.Corridors — A corridor can be defined as a strip of landthat aids in the movement of species between disconnectedpatches of their natural habitat. This habitat typically includesareas that provide food, breeding ground, shelter, and otherfunctions necessary to thrive. Not only can human impactaffect the size of patches, as described earlier, but it can alsocause animals to lose the ability to move between the patches.Because they allow for long-term genetic interchange, corridorscan also reduce inbreeding, facilitate patch re-colonization,and increase the stabilities of populations and communities.Planners, landscape architects, land managers and conservationbiologists are faced with the task of reconnecting existingfragmented landscapes. Strategic conservation decisions needto be made within a larger community context. Clear financialA corridor can be definedas a strip of land that aidsin the movement of speciesbetween disconnectedpatches of their naturalhabitat. This habitat typicallyincludes areas that providefood, breedingground, shelter, and otherfunctions necessary to thrive.

19Chapter 2Community <strong>Wildlife</strong> and <strong>Habitat</strong> Conservation Framework and Principles<strong>Wildlife</strong> corridors appear tobenefit not only wildlife butalso plants. A six-year studyat the world’s largest experimentallandscape devotedto the corridors has foundthat more plant species -- andspecifically more native plantspecies — persist in areasconnected by the corridorsthan in isolated areas of thesame size. The resultssuggest that corridors arean important tool not only forpreserving wildlife but alsofor supporting and encouragingplant biodiversity.CASE STUDY<strong>Wildlife</strong> Corridors Benefit Plant Biodiversity<strong>Wildlife</strong> corridors appear to benefit not only wildlife but alsoplants. A six-year study at the world’s largest experimental landscapedevoted to the corridors has found that more plantspecies--and specifically more native plant species — persistin areas connected by the corridors than in isolated areasof the same size. The results suggest that corridors are animportant tool not only for preserving wildlife but also forsupporting and encouraging plant biodiversity.Researchers created a massive outdoor experiment at theSavannah River Site National Environmental Research Parkon the South Carolina — Georgia line. In two earlier studies,the researchers concluded that corridors encourage the movementof plants and animals across the fragmented landscapes.They also found that bluebirds transfer more berry seeds intheir droppings between connected than unconnected habitatpatches, suggesting that the corridors could help plants spread.The latest research tackled a much broader question: Docorridors increase plant biodiversity overall? The differencebetween the habitats studied was similar to the differencebetween urban and natural areas, where corridors are mostoften used. The experimental sites were created in 1999,and there was little difference between connected andunconnected patches of habitat one year later. But a differentpattern became clear in ensuing years. Not only were theremore plant species in connected than unconnected patches,there were also more native species. The difference arosebecause unconnected patches gradually lost about 10 nativeAn aerial photograph of one experimental landscape showing habitat patchconfigurations.species over the 5 years, whereas the natives persisted inconnected patches.Meanwhile, the corridors seemed to have no impact on thenumber of exotic or invasive species in the connected andunconnected patches. It seems that either exotic speciesalready were widespread, and did not rely on corridors fortheir spreading, or they remained in one place. The scientiststhink that invasive species, which by definition are good atspreading, are little affected by corridors. Native species,by contrast, are less invasive in nature and appear to beassisted more by the corridors and the linkages they provide.The researchers suggest it may be that corridors play to thestrengths of native species.Source: University of Florida News, 2006; Writer, AaronHoover, reporting on work by Douglas J. Levey, et al, Science,2005 “Effects of Landscape Corridors on Seed Dispersalby Birds.”Photo Courtesy of U.S. Forest Service

Chapter 2Community <strong>Wildlife</strong> and <strong>Habitat</strong> Conservation Framework and Principles20limitations related to land purchases, restoration options, easementsand other tools will shape the final outcome.Facilitating connections between Florida’s already protectedlands and outlying patches can be a valuable tool. Throughcareful planning and design, wildlife corridors can lessen thenegative effects of habitat fragmentation by linking patches ofremaining habitat. Corridors can be incorporated into thedesign of a development project either by conserving an existinglandscape linkage, or by restoring habitat to function as a connectionbetween protected areas onsite, off-site and through-site.There is still considerable debate over the effectiveness of corridorsand how they should be configured and sized. The answerdepends on the species under conservation consideration. Thelevel of connectivity needed to maintain a population of a particularspecies will vary, and depends on such issues as the sizeof the population, survival and birth rates, the level of inbreeding,and other demographics which can serve as baseline data todetermine whether a corridor is likely to be functional.In 1992, forestry experts Paul Beier and Steve Loe drafted,In My Experience: A Checklist for Evaluating Impacts to <strong>Wildlife</strong>Movement Corridors. They identified six steps for evaluatingcorridor practicality, including to:1. Identify and select several target species for the design of thecorridor (e.g., select "umbrella species" and the associatedbenefiting species).2. Identify the habitat patch areas the corridor is designed toconnect.3. Evaluate the relevant needs of each target and associatedspecies such as movement and dispersal patterns, includingseasonal migrations or environmental variations (e.g., somespecies depend on there being season wetlands available).4. For each potential corridor, evaluate how the area willaccommodate movement by each target species.Protected interior environment (brighter green), progressing to those that essentially become all edge environment and no interior.Graphic by Benjamin Pennington, remade from illustrations in Micheal E. Soule, Journal of the American <strong>Planning</strong> Association, “Land Use <strong>Planning</strong> and<strong>Wildlife</strong> Maintenance, Guidelines for Conserving <strong>Wildlife</strong> in an Urban Landscape,” 19915. Draw the corridor on a map and work with community toestablish a pragmatic plan to sustain or restore the connections.6. <strong>Design</strong> a monitoring program to gauge corridor viability,human community interface impacts and modification needs.When evaluating a potential corridor, it is important to considerhow likely the animal(s) will encounter the corridor’s entrance,actually enter the corridor, and follow it. Factors to evaluateinclude whether the corridor contains sufficient cover, food, andwater, or whether these features need to be created and maintained.It is also important to determine if the new developmentcontains or creates impediments to wildlife movement. Thesemay include topography, the introduction of new roads, and thetypes of road crossing, fences, outdoor lighting, domestic pets,and noise from traffic or nearby buildings, exotic plant migration,and other human or disturbance impacts.Edges — The “perimeter zone” of a patch can have a somewhatdifferent environment from the interior of the patch, due toits proximity to adjacent patches, changes in light penetration,noise, microclimate, and other factors. This “edge effect” canhave implications when planning for conservation areas. Forexample, a long, thin, habitat patch could essentially be all edge,while a circle has the minimum perimeter for a given area, andThere is still considerabledebate over the effectivenessof corridors and how theyshould be configured andsized. The answer dependson the species under conservationconsideration.

21Chapter 2Community <strong>Wildlife</strong> and <strong>Habitat</strong> Conservation Framework and PrinciplesEdge effects have implicationswhen planning themajor components of acommunity’s green infrastructuresuch as decidingwhether to work towarda single large or severalsmaller interconnectedreserves. In more developedareas, a carefully considerednetwork of varyingsized habitat patches withappropriately designedlinkage corridors may beappropriate.CONSIDERATIONS OF CORRIDOR DESIGN•The corridor should be as wide as possible. The corridorwidth may vary with habitat type or target species but arule of thumb is wider and larger areal extent is better.•The longer the corridor the wider it may have to be.•Maximize land uses adjacent to the corridor that reducehuman impacts to the corridor. Essentially, corridorssurrounded by intensive land uses should be wider thanthose surrounded by low intensity uses.•To lessen the impact of roads, maintain as much naturalopen space as possible next to any culverts and bridgeunder/overpasses to encourage their use.•Do not allow housing or other impacts to project into thecorridor or form impediments to movement and increaseharmful edge effects.•If buildings or housing are to be permitted next to thecorridor, establish a buffer and place a conservationeasement over this area.•Where the hydrology supports it, place the development’sstormwater retention/detention facilities between the managedland and conservation land as an added buffer.•Develop strict lighting restrictions for the houses adjacentto the corridor to prevent light pollution into the corridor.Lights must be directed downward and inward towardthe home. (This may involve adopting local “Dark Skies”lighting ordinances).Source: Adapted from Monica Bond, Center for BiologicalDiversity, Principles of <strong>Wildlife</strong> Corridor <strong>Design</strong>, 2003.thus the least edge. Some species, such as white-tailed deer,eastern cottontail, bobwhite, are edge-adapted and are notharmed by the edge effect. Many other common specieshave not adapted to the edge zone.Edge effects have implications when planning the major componentsof a community’s green infrastructure such as decidingwhether to work toward a single large or several smaller interconnectedreserves. In more developed areas, a carefullyconsidered network of varying sized habitat patches withappropriately designed linkage corridors may be appropriate.MERGING BIOLOGY WITH PL ANNINGIn 2003, Karen Williamson of the Heritage Conservancy producedGrowing with Green Infrastructure, which pulls togetherbiology and planning studies. She describes a network oflands that can make up green infrastructure. These lands canrange in size and shape, and require differing levels of conservationand protection from human impact, according to thetype of resources being protected.These include hubs, generally larger tracts of land which actas an ‘anchor’ for a variety of natural processes and providean origin or destination for wildlife. These can include wildlifereserves, managed native lands, working lands including farms,forests, and ranches, parks and open spaces, and recycledlands including mines, brownfields, and landfills that have beenreclaimed. Links “interconnect the hubs, facilitating the flow ofecological processes.” These may include linear conservationcorridors such as river and stream corridors and greenways, andbuffer lands such as greenbelts. Landscape linkages are “openspaces that connect wildlife reserves, parks, managed andworking lands, and provide sufficient space for native plants andanimals to flourish.” These may also include cultural resources,recreational areas and trails, scenic viewsheds, and even streetscapes.

Chapter 3Envisioning and <strong>Planning</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> Friendly Communities22Photo Courtesy of David Moynahan Photography

23Chapter 3Envisioning and <strong>Planning</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> Friendly CommunitiesOne of the best ways toensure a future for wildlife is towork toward developing anintegrated mix of connectedparcels or patches withinand near to our communitiesthat are planned, designedand managed for theirhabitat values.Reprinted by permission of the artist, Gene PackwoodA green infrastructure and wildlife friendly vision can providemany benefits to a community and its residents. One of the bestways to ensure a future for wildlife is to work toward developingan integrated mix of connected parcels or patches within andnear to our communities that are planned, designed and managedfor their habitat values. Impacts to wildlife habitat in a localcommunity occur, for the most part, as a result of developmentapprovals given incrementally over time. To sustain wildlife andbiodiversity within, or in close proximity to, “developed” land,sustained efforts must involve limiting and managing disturbanceto habitats and enhancing connectivity. Very little will happen atthe level of the community to conserve, integrate or enhancewildlife habitats unless people understand, plan, design andmanage for this purpose.GOAL S FOR PL ANNING WILDLIFE-FRIENDLYCOMMUNITIESFrom the perspective of planning a wildlife-friendly community,there are a number of goals around which an effective localeffort can be formulated, keeping in mind that each speciesrequires a particular mix of food, cover, water, living and reproductivespace and limits on disturbances.Goal 1 — Plan and maintain an overall habitat frameworkwith identified ecological corridors, linked to larger patches ofhabitat managed around systematic efforts to minimize habitatloss and its fragmentation. Supportive actions may include:•Linking (where possible) community and regional parks,mitigation areas, greenways and forests against the backboneof local watershed features (streams, bayous, wetlands, rivers,sink holes, etc.).•Integrating transportation and stormwater infrastructuredevelopment to capture wildlife supporting and enhancementopportunities.•Incorporating private green areas into the larger green infrastructurenetwork (e.g., golf courses, botanical gardens, largeparcel easements and set-asides).•<strong>Planning</strong> a hierarchy of open spaces. For example, one layermight include parks, another larger stormwater infrastructurecomponents that function as buffers to create planned separationof human and wildlife communities (this may be ofparticular importance in the planning of large new developmentsthat come up against large managed environmentalareas, especially those that support larger species such asFlorida black bear, panther, alligators, crocodiles, beaver.Such separation conversely discourages intrusion of domesticcats and dogs into the managed protected areas).Goal 2 — Preserve and enhance waterbody and riverinenative green edges (create combined upland buffer andin-water littoral edges that further link to larger habitat patches).Where possible, do not subdivide properties down to the water’sedge; instead, maintain a common community shoreline corridorwith an upland component that links to larger habitat patches.Following a tiered landscape conservation approach, acommunity can enhance or maximize buffer variety and size

Chapter 3Envisioning and <strong>Planning</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> Friendly Communities24Significant forested riparian edge has been left alongside this lake in Harmony inOsceola County. Even within the community, sizable tracts of forest wrap throughthe developed areas and golf course. Water quality and wildlife benefit, as dothe community residents that share the common natural land and lake resources.by leveraging connectedness to existing conservation areas.Importantly, wildlife linkage benefit is available across jurisdictionswhen upland and riparian habitats are conserved throughcorridors and buffers.Goal 3 — Carefully weigh the impacts of the pattern ofdevelopment when planning for larger areas or multiple smallerparcels (cities, counties, large landowners). Sprawl results inproportionately more fish and wildlife habitat loss and habitatfragmentation than compact patterns of development. Compactdevelopment patterns allow a linking of undeveloped parcelsthrough developed landscapes. In addition, sprawl’s disperseddevelopment pattern leads to a greater reduction of waterquality and quantity by increasing runoff volume and stormwatertreatment and facility maintenance costs, altering regular streamand/or wetland flow, lessening water height and duration, andaffecting watershed hydrology by reducing groundwaterrecharge and groundwater levels.Graphic Courtesy of Benjamin PenningtonMANAGED ENVIRONMENTAL L ANDSADD TO THE QUALIT Y OF LIFE ANDREAL MARKET VALUEIn most instances the value of land adjacent to parks, greenwaysand other environmental managed lands increases dueto the permanence and desirability of having assured naturallands as a neighbor. According to a study conducted for theTrust for Public Land in 2004, proximity to open space has asignificant effect on land values in Leon County and AlachuaCounty. In densely settled portions of Leon and AlachuaCounties, the report found buyers could expect to pay$14,400 and $8,200 more respectively for single-familyhomes if they were within 100 feet of open space. The studyalso found that proximity to open space raised the value ofvacant land. In Leon County, vacant parcels within 100 feetof open space commanded a premium of $31,800. Leonhad about 5,900 parcels close enough to open space tohave their values enhanced; Alachua had 8,100. The studyestimated that the aggregate impact on land values in LeonCounty was $159 million, and in Alachua County, $143million. At 2004 tax rates, the additional land values brought inan additional $3.5 million in property taxes for each county.In recognition of this value, local governments shouldconsider working hand-in-hand with the land managers ofmanaged environmental areas to establish buffered overlayareas (sometimes called Greenline areas or overlay zones)wherein new development or redevelopment receives an “upfront” review to addresses and resolve compatibility issues.Source: E. Moscovitch, (2004). Open Space Proximityand Land Values, Trust for Public Land study by Cape AnnEconomicsIncreased Property ValueResulting from Open Space Proximity160155150145140135130159Leon143Alachua

25Chapter 3Envisioning and <strong>Planning</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> Friendly Communities<strong>Habitat</strong> is impacted by aprogression of spatialdeterioration advancedby poor land developmentchoices overtime. Broadlythese include: dissection,fragmentation, perforation,shrinkage and eventualattrition.THE PATTERN OF L AND DEVELOPMENTREL ATIVE TO HABITAT SPATIAL PROBLEMLand development patterns affect existing habitat areas.As an area is being planned for development or redevelopment,actions can be taken to reduce or minimize thehabitat-damaging effects. First and foremost is to limit (orat least direct and manage) sprawling, low density patternsof development. Look for opportunities to concentratedevelopment in more compact formats while permanentlysetting aside linked habitat within common open spaceareas. This can be promoted using planning tools such asconservation subdivision, rural land stewardship areas,traditional neighborhood design patterns, sector plans andDevelopments of Regional Impact.<strong>Habitat</strong> is impacted by a progression of spatial deteriorationadvanced by poor land development choices overtime.Broadly these include: dissection, fragmentation, perforation,shrinkage and eventual attrition.Sources: 1) Soule, Michael. Land Use <strong>Planning</strong> and<strong>Wildlife</strong> Maintenance _ Guidelines for Conserving <strong>Wildlife</strong>in an Urban Landscape, 1991; 2) Forman, R. T. T. LandMosaics: The Ecology of Landscapes and Regions, 1995;and, 3) Ecological <strong>Design</strong> Manual for Lake County, 2001.<strong>Habitat</strong> dissection (a road through it), fragmentation (multiple roads), dissection with perforations (roads and development sites), habitat dissection with shrinkageand finally attrition (overall loss or reduction of habitat).Graphic Courtesy of Benjamin Pennington

Chapter 3Envisioning and <strong>Planning</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> Friendly Communities26Goal 4 — Where present, strive to maintain the rural characterand rural economic base. Sustain agriculture areas, infrastructureand working rural landscapes.Goal 5 — Recognize and plan for natural ecological maintenanceevents such as floods and fires. These events are a partof natural ecosystem dynamics and are important to nativehabitat health and continued existence. Plan communities toincorporate and sustain the flood prone areas as undevelopedcommon areas. Also, plan land uses around the ecologicalrealities of smokesheds incorporating “firewise” communitydesigns (see Chapter 7, “Management and <strong>Design</strong> Factors”).Goal 6 — Preserve a background matrix of predominate nativevegetation and habitat types. These features are adapted tolocal climate and soil conditions, support wildlife and likelyrequire less maintenance and water.Goal 7 — Preserve forested areas and the understory andnative soil associations. Minimize disturbance of such areas andremember that larger forested patches have a better chance ofpreserving localized micro-climate features supportive of uniqueplant and animal species (e.g., consider light and humidity).Goal 8 — Identify and avoid activities that dehydrate oralter the seasonal water flows or duration of inundation to wetlands,hammocks or waterbodies (e.g., diversions, drawdown,or damming effects from roads and berms, etc.).Goal 9 — Preserve and use natural systems (or even linkedfragments of natural systems) within a community to enhance,add value and distinction.Recognize and plan fornatural ecological maintenanceevents such as floodsand fires. These events area part of natural ecosystemdynamics and are importantto native habitat health andcontinued existence.Comparative scenario between two forested, lakeside development plans. Left shows a common Florida development pattern that removes or reduces thelakeside forest, places multiple piers into the lake and, segments the lake frontage into multiple individual lots. Right side shows a more wildlife friendlyapproach that clusters homes and roads away from the lake to preserve the forested edge, places one common community pier in the lake (accessible bya community trail) and, keeps the lake frontage un-segmented allowing linkage between aquatic and upland environments.Graphic Courtesy of Benjamin Pennington

27Chapter 3Envisioning and <strong>Planning</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> Friendly CommunitiesGraphic by Benjamin Pennington using a FDEP, Land Boundary Information System (LABINS) photoOscar Scherer State Park (outlined), like many managed environmental areas, is feeling the impact from neighboring developmentsC ASE STUDYThe Good Neighbor Approach: Oscar SchererState Park in Sarasota CountyAs with many other managed environmental areas,Oscar Scherer State Park in Sarasota County hasfaced development pressures from surroundingproperties that affect the sustainability of the parkitself. A comprehensive plan amendment for anincreased density development on a parcel adjacentto the park served as a catalyst for a partnershipbetween the local government, the developer andarea citizens. The resulting local Blackburn PointSector Plan was adopted by Sarasota Countythrough an ordinance.The plan provides guidance on how new developmentcan be designed to be habitat and wildlifefriendly. One of the most critical elements is the“Notice of Proximity,” which is recorded in the deedsand rental agreements on all properties within theSector Plan boundaries. It puts all property ownerson notice that the park is within close proximity andthat there are certain practices such as prescribedfire, pesticide usage, heavy machinery usage, andremoval of exotic plants and animals that take placein the park. The notice states that these propertyowners or renters shall be deemed to have knowledgeof and to have consented to these resourcemanagement practices. The State’s Division ofForestry routinely requires such notice for propertiesbordering its lands.

Chapter 3Envisioning and <strong>Planning</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> Friendly Communities28Further, the plan emphasizes that:•Adjacent developments use materials and colors thathelp to camouflage the appearance of buildings,fences and other structures to reduce their visualimpact on park visitors.•Stormwater ponds be designed along the parkboundary to minimize the impact of feral anddomestic cats and, conversely, discourage intrusionof wildlife into the backyards of residents.•Native vegetation buffer zones be used, and bemaintained to be free of exotic vegetation.•Consideration be given to wildlife friendly lighting,known as “Dark Skies Lighting.”Such a cooperative approach could also be usedto promote:•Clustering homes and development away andreducing the number of individual lot lines thatdirectly abut the park boundary, providing greaterbuffer between wildlife and people.•Expanded perimeter buffers of native vegetation tohelp address noise, light and other wildlife disturbanceissues.•Interconnections between the park and adjoiningdevelopment greenways and open spaces.•Development-wide use of native vegetation andlandscaping that blends with the native habitat butincludes consideration of fire and smokesheds andfirewise development.•Water conservation, use of reclaimed water, energyconservation and environmentally benign buildingmaterials.•Elimination or reduction of the use of pesticidesand fertilizers.•Homeowner involvement in park management andeducational programs.Adjacent developments use materialsand colors that help to camouflage theappearance of buildings, fences andother structures to reduce their visualimpact on park visitors.Stormwater management facilities for developments backing-up to managed environment areas can be strategically placed to create a barrierto developmental impacts such as lights, domestic cats, and children.Graphic by Benjamin Pennington using a LABIN photo