Scandinavian-Britain

Scandinavian-Britain

Scandinavian-Britain

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Attainrwiaancse6COCOF-nb ihe late

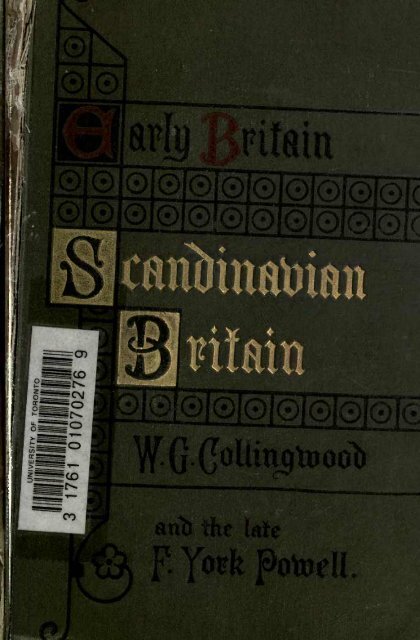

EARLY BRITAINSCANDINAVIANBRITAINBYW. G. COLLINGWOOD, M.A., F.S.A.PROFESSOR OF FINE ART, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, READINGEDITOR TO THE CUMBERLAND ANDWESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETYWITH CHAPTERS INTRODUCTORY TO THESUBJECT BYTHE LATE F. YORK POWELL, M.A.SOMETIME REGIUS PROFESSOR OF HISTORY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORDWITH MAPLONDONSOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGENORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE, \V.C. ; 43, QUEEN VICTORIA STREET, E.G.[BRIGHTON: 129, NORTH STREETNEW YORK: E. S. GORHAM1908

PUBLISHED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE GENERALLITERATURE COMMITTEE3 A

CONTENTSCHAPTERS INTRODUCTORY BY THE LATE PRO-FESSOR YORK POWELL-PAGEI. MATERIALS 7II. MOTHER-LAND AND PEOPLES . .* 12III. THE WICKING FLEETS .... 28SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINI. THE EARLIEST RAIDS .... 43II. THE DANELAW 821. THE AGE OF ALFRED .... 822. EAST ANGLIA IOI3. THE FIVE BOROUGHS . . . . IO84. THE KINGDOM OF YORK .. .1195. SVEIN AND KNUT 1446. THE DOWNFALL OF THE DANELAW . 1 67III. THE NORSE SETTLEMENTS . . . .1821. WALES 1832. CHESHIRE AND LANCASHIRE . . .IQI3. CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND . 2O24. DUMFRIESSHIRE AND GALLOWAY . .2215.MAN AND THE ISLES .... 2266. THE EARLDOM OF ORKNEY . ..244INDEX 265MAP OF SCANDINAVIAN BRITAIN . To face Title

PREFATORY NOTEIN the part of this work for which I am responsible, that isto say from page 43 onward, kind assistance in proof-readinghas been given by the Rev. Edmund McClure, Secretary tothe S.P.C.K., and by Mr. Albany F. Major,Editor (o theViking Club. The chapters on Northumbria (pp. 119-181)have been read by Mr. William Brown, F.S. A., and the chapteron Orkney by Mr. Alfred W. Johnston, F.S. A. Scot., Editorof Orkney and Shetland Old Lore.W. G. C.

SCANDINAVIAN BRITAININTRODUCTORY CHAPTERSBy the late ProfessorYork PowellI. MATERIALSLibros ipsos relegi quorum quamvis verba non reciio sensustamen et res actas credo me integre retinere. JORD., DeGet., Pro!.THE last great wave of Teutonic Migration (beforethe discovery of America), is that by which greatparts of the British Islands and Gaul were conqueredand settled by new-comers from the <strong>Scandinavian</strong>peninsulas. It is with the part of this movement whichconcerns <strong>Britain</strong>, that this little book will briefly deal.The results of this Migration are great enough tojustify our spending some little time and trouble uponits history, for our population, our laws, and ourlanguage still show clear proofs of its influence, andamong the several circumstances that have distinguishedthe history of our own country from thatof other parts of West Europe, the incoming of theNorthmen cannot be held the least.

8 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINIt will be well before speaking of this movement,its causes, progress, and effects, to give some accountof the chief sources upon which our knowledge of itmust be based. The sources are of twofold origin,springing from books or from things. The latter compriseall the facts and ideas that can be drawn fromphysical geography, from archaeologic discoveries,and from numismatics. The former, our writtenauthorities, may be grouped under the heads ofBritish, <strong>Scandinavian</strong> ,and Continental.Under the firstheading come the Old EnglishChronicle by various anonymous authors, in its variousMSS., vernacular and Latin, ranging over nearly threecenturies, of the highest importance, as the work oftruthful contemporaries the different references; byOld English authors, from King Alfred to BishopWulfstan, to historical events of their days, andseveral poems. To these we must add several lives ofsaints, in Latin or English, and that vast collectionof deeds and records that makes up our Old EnglishDiplomatarium, a mine of information on places andpersons during the ninth and tenth centuries.Next come the careful and accurate Irish chronicles,especially Tighernach's Annales, the compiled Annalsof Inisf alien Chronicon>Scotorum, and the compilationknown as the Annals of the Four Masters, whichgives us an orderly mass of facts not found elsewhere,and are of main use in fixing the difficult chronologyof the periods they cover.The list of British authorities is concluded by theWelsh chronicles, especially the Brut y Tywysogion

MATERIALS 9and Annales Cambria, and by stray facts and namesfrom other Welsh sources. To these must be addedthe Latin Chronicle of Man.First at the head of <strong>Scandinavian</strong> authorities standsAre the historian, whose works the Book of theSettlements in Iceland^ the Libellus Islandorum (asketch of early Icelandic history), and Book of theKings of Norway (which we have as edited by SnorreSturlason in the thirteenth century), with manymemoranda from other of his writings no longerextant give the best and fullest information on thecondition of heathen Norway, and on the fortunesand deeds of such of the emigrants therefrom, asfinally, after years of foray and conquest in the BritishIslands, passed on to the new-found and uninhabitedshores of the Faroes, Iceland, and Greenland. Thehistory of King Half and some of the family Sagas ofIceland, give what is probably independent information.But on this side we should get an incompletenotion of those wickings, or sea-rovers, whose exploitshelped to make our history, without the help of theso-called Eddie poems, a series of epic and dramaticlays, chiefly of the ninth and tenth centuries, manyof which were, we may confidently hold, composedwithin the four seas, and no doubt reflect accuratelythe spirit of the very men that first made and heardthem, the conquering <strong>Scandinavian</strong> settlers in Great<strong>Britain</strong> or Gaul. Among these there are found in theMS. that has luckily preserved much of them to us, apoem or two, the earliest, that we may1ascribe to theSee Origines Islandias, Vigfusson and Powell [1906].

10 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINgeneration before the exodus in old, sturdy, practical,heathen Norway and also one or; two, the latest,that are Christian, and mirror for us the feelingswith which a Northern convert of the Celtic Churchregarded the common but absorbing problems oflife, and death, and the hereafter. A few poemsrelating to actual historical events have also survived,more or less completely embedded in the Lives ofkings or heroes, such as the Lay of the Darts, translatedby our Gray ;the praise and the dirge of EiricBlood-axe, twice King of York ;and the Raven songon Harold Fairhair.These compositions are all in the old Northerntongue, but in Adam of Bremen, and his like, thereare Latin accounts of <strong>Scandinavian</strong> affairs based onvernacular and other sources ;and Saxo the Long,the Danish monk, has in a remarkable work, whichfor plan and treatment reminds one of our Geoffreyof Monmouth, preserved many interesting facts andtraditions, often drawn from works and poems nowlost, but furnished to him in great part by Arnoldthe poet, a travelled Icelander, his contemporary atWaldemar's Court.The chief Continental authorities are early Latinchronicles by Saxons, and Franks, and Aquitanians, andcontemporary notices of the Spanish-Arabic historians.Of the many scholars that in modern days have dealtwith the analysis and synthesis of these documentsreading, appreciating, and digesting them, and givingtheir results to the public the most useful are theNorwegian, Munch, whose keen geographic instinct

MATERIALSIIand vast industry served him well the; Dane,Steenstrup, whose scientific method and trained skilland patience have helped him to unravel many anenigma that puzzled his predecessors; Freeman, theEnglishman, who has taught a generation of hiscountrymen the way to learn what may be learntfrom the past ;and the Icelander, Gudbrand Vigfusson,who, possessing an unrivalled knowledge of IcelandicMSS., and giving unflinching devotion to his work,has been able in every branch of old Northernlearning, from chronology to metric, to do more toadvance our knowledge of this great <strong>Scandinavian</strong>exodus than any man of his time.Among other historical workers who have attackedvarious sides of the subject, and who should justlybe referred to here, are Dr. Jessen, Dr. Storm, Mr.[Sir H.] Howorth, the historian of the Mongols, andJ. R. Green, who gave the last few hours of his short lifeto an eager and undaunted study of the subject whichhe never lived to complete, but which remains as apiece of suggestive, if necessarily imperfect work.Such being the materials upon which this littlebook is based, it remains to fix its scope and aims.Beginning with a sketch of the conditions amidwhich the migrations took place, and an endeavourto grasp their character and origin, it will thenseek if possible to follow the several phases andphenomena of the various migrations and settlementsthat affected the British Islands, and finally try toweigh the results and effects of those settlements.

12 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINII.MOTHER-LAND AND PEOPLESEx hac igitur Scandza insula quasi officina gentium aut certevelut vagina nationum . . .quondam memorantur egressi.JORDANIS, De Get., cap. 4.EVER since we have any historic record of itsexistence, we are told by successive historians andpoets how the <strong>Scandinavian</strong> peninsula sent forthswarm after swarm of itspure-blooded, tall, fairhaired,white-skinned children, southward over theBaltic, to seek warmer and more fertile homes.These migrations followed two main routes in earlytimes, the East way and the South way. Over theEast way went the Goths, by Wilna along the broadriver-plains to Uampa-stead (as they called Kiev),around which Giberic and Ermanaric built up thefirst great Teutonic Empire. On the South way,by the peninsula we now call Denmark, and up therivers that run into the North Sea, there had probablypassed tribe after tribe in migrations of which wehave no written record. In the fifth century a newroute seems to have been struck, the West way, andfrom the beech-clad islands and sandy links of theDanish peninsula, and the broad flat pastures aboutthe river mouths between Elbe and Rhine, theresailed westward many a ship-load of armed emigrantsfrom the great tribal leagues, Eotish, English, andSaxon. For they had heard the news that there

MOTHER- LAND AND PEOPLES 13were new homes to be won in the weakly defendedRoman diocese, and already bands of sea-rovers fromamong them had harried the coasts on their ownaccountWhat time the Orkneysor foughtreeked with Saxon deadCLAUDIAN.over the land in the service of the hardpressedrulers of <strong>Britain</strong>. So all along the " Saxonicshore," from the reedy broads south of the Wash to thesandy dunes about the Humber mouth, and furthernorth up to the " Frisic Sea," the Firth of Forth, andfurther west into the breaks of the Southdowns, upthe Belgic plain between the marshes and the wood,into the fat meadow-lands of the Bajocasses and onthe warm Islands of the Channel Vectis and Caesareaand the rest, they came and settled with their wives,and children, and cattle, and set up new states andflourished exceedingly.For three centuries after this there seems to havebeen no further emigration east, south, or west. Allwe hear from Northern tradition has to do with thestruggles and feuds of Swedes, Goths, and Danes,round and over the Scandian peninsula. The fifthcentury is accounted for by the epic cycle of Ingiald,whom Alcuinus spurns as a heathen hero, and ofBeowolf; the sixth is covered by the exploits ofHrodwolf Grace and his kinsmen and champions ;while the mighty deeds of Ingwar Widefathom remainfrom the end of the seventh century, ending with thenever forgotten fight of Bravalla, won by Sigfred Ring

14 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINover Harold War-tooth, in the eighth century,a successionof efforts, in fact, on the part of vigorouskings to raise an empire, such as Ermanaric had setup and ruled over for so many glorious years. Theseefforts to bring the three great peoples under onehead failed, but for three centuries they seemed tohave absorbed the energiesof the <strong>Scandinavian</strong>folk.The end of the eighth century saw the renewalof the migrations from the north. Eastward wentRuric and Olga, to found the realm of Holm -garthor Garth-ric, with Newgarth (the Russian Nov-gorod)and Kiev for their capitals, pushing whence southwardthey brought their ships up to besiege the wallsof Mickle-garth itself, that New Rome, which was therichest, most populous, and mightiest city of thewhole world. But with their fortunes we have not todo here. Southward^ the great confederacies, Frisian,Saxon, and Frankish, were, though hard put to it nofresh settlersdoubt, yet strong enough to repulse anyfrom the North.The West way was stillopen, and over it theresailed fleet after fleet for 220 years. This westernmovement is made up of two distinguishable streamsof migration ; one, mainly Danish, starting from theWick and from the Gothic coast, and Danish islesand headlands, and creeping down the Frisian coastto the Rhine delta ;then roving to the East Englishland, or up the Thames mouth to the East Saxon orKentish shores, or passing on down Channel attackingthe fruitful and open country on either side, occupying

MOTHER-LAND AND PEOPLES 15the islands as depots and arsenals ;thence pushingon to Ireland or rounding the Cornish peninsula, tomake the British Channel or the South Welsh havens ;or weathering the rocky Breton headlands and trendingsouthwards along the Frankish, Gascon, Spanish,and Moorish shores.The fleets that took this route were mainly Danesand Gotas, and their leaders of Danish blood, andthey followed the path by which their predecessors,the Saxons, Angles, and Eotes, had come three centuriesearlier, only going further because they did notfind such an easy prey.The second stream of migration, that followed bythe Northmen^ was a new one. Its fountain head isthe deep firths of the west coast of Norway, whenceit crosses to the Isles of the Caledonians and Picts(Shetland, Orkney, and Pentland coasts), whence itturns south to Fife, and as far as the Northumbrianand Lincoln lands jor curving round through theHebrides into the Sea of Man, touches that islandand all the fair coasts, Pictish, Irish, and British, thatlie about it ;thence south, lapping the west and southof Ireland.From the Northmen's settlements in our own islandsthere later went forth on new ventures, to unpeopledand dimly known lands, many venturous souls, overthe Haaf (the Atlantic) by way of the Sheep Islands(Faroes) to Iceland, setting up prosperous colonieswhere the feet of no man, save the Irish hermit, hadever trod. Whence, again, bolder stillspirits bravedthe Arctic Sea, and established two settlements on the

J6SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINwest coast of Greenland. The furthest bound of thismigration was reached when Icelanders and Greenlanderssailed down the polar current to Stonelandand Wineland, along the desert, rockspread shores ofLabrador, to the fishing-grounds and forest-cladhavens of that vast estuary we call after St.Lawrence.To gather some explanation of the causes thatmade possible such astonishing enterprise as this, wemust turn back to Norway. Aloof from the secularstruggles which created and welded the tribal confederaciesof the Baltic shores, Danes, Swedes,Wandals, Burgunds, Bards, and Goths, there weregrowing up along the coast and in the upland dalesof the North way, in primitive isolated tribes,Throwends, Reams, Aens, Neams, Haurds, Rugians,Granes, Heins, Thules, and the like, each under theirown rulers, a hardy and vigorous race, woodmen,shepherds, farmers, fishers, who had, by the end ofthe eighth century, colonised the long and narrowwinding strip of soil between sea and glacier whichwas called Haloga-land ; developed great and lucrativefisheries, and the hunting of whales, seal, and walruses ;opened out a fur trade with the Finns, and kept upa half merchant, half piratical intercourse with theBeormas of the White Sea round the cold NorthCape.How admirable a training-ground nature had grantedthese Northmen is clear when one looks at the map.The west coast, that over against the British Islandsfrom Cape Start to the Naze, the Sailor's Naze,

MOTHER-LAND AND PEOPLES 17Lidhandesnes, is a succession of buttresses or limbsof the central Doverfell backbone, stretching seawardsat right angles to it,and parted by sheer deep valleyshalf filled with water running far up into the land ;round these deep firths lie little scattered plots ofarable land, about the mouth of a stream or in acombe of the hills ;above lie black woods, and onthe upper hill here and there pasture-slopes wherethe cattle graze in the summer. Each of these firthshas a life of its own, its only outlet is the sea ;outside,clustered about the mouths of each firth andits headlands, is a fringe of islands, large and small,which farther north form a regular skerry or barrierreefsuch as our Hebrides, but here lie closer to land,like Skye, and Mull, and Isla. In this part of Norwaythere are three great inlets Sogn, belonging to theHaurds; Hardanger, the HAURDS' Firth, with thefamous stations, Bergwin (Bergen), and Alrecstead(Alrecsstad) on the coast and; Stafanger, the Firth ofthe RUGIANS, with Stafanger, Ogwaldsness, Out-stone(Ut-stan) on its isles and coastlands, and the Goat'sFirth (Hafrs-Firth) just outside it.The southern ness of Norway with its port, Qwin, andthe coast eastward halfway to the head of the GreatWick, belongs to the Egda-folk, a division of theHaurds. Next to them up to the top of the bay liesWestmere, then the Land of the GRENS (which justtouches the Wick), and then Westfold, probably aREAM settlement ; Sciringshall is its great port nearthe great Most and above it lay the later Tunsberg.Opposite Westfold comes Wingul-mark, with SarpborgB

1 8 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINfor its chief place, and opposite the Egda-folk,Ranrice jat the extremity of which, upon the Goth'sriver, was an old border trysting-place of the <strong>Scandinavian</strong>kings. These are the lands that border theWick, east and west.North of the Sogn firth come the Feles (Fialar) andFirths, but past Cape Start, where the land turns andruns north-east, we come to the northern land of theREAMS, North and South Mere and Reamsdale, stretchingup over two degrees of latitude. Through NorthMere pierces the great inland sea of the Throwends,with its numerous creeks and headlands, such asAgda-ness, Nith's oyce or Nidaros, Frosta the mootsteadof the Throwends, each notable from someevent in Norwegian history. Down to this greatloch slope many deep and long dales, Orca-dale,Gaula-dale, and others, from the upland hill-countryeast and south.North of Throwend-ham or Thrond-heim liesNeam-dale with its coast station, Hrafnista, and, northof that, Haloga-land's barren five degrees of latitudestretch along by the sea, north-east, ending in Westfirthand the great islands that head the Skerry,islands .only visited by Finnish fowlers, fishers orhuntsmen in those far-off days.Such being the land, what manner of men dwelttherein at the end of the eighth and the ninth century ?All the evidence we have points one way, that alongthe west coast there were growing up vigorous fishingand coasting trades (those true nurseries for seamenhere as elsewhere, for example in Hellas and England).

MOTHER-LAND AND PEOPLES 19Our King Alfred's friend, Oht-here, a Haloga-lander,1tellsof the fur-trade^ which depended mainlyon theyearly tribute from the Finns, each chief of that peoplehaving to furnish 15 martin skins, i rein-deer pelt,i bear-skin, i bear or otter-skin coat, 40 ambers offeathers, 2 ship ropes of 60 ells (i of horse-whale skin,i of seal-skin). He also spoke of the whale fishing,especially the chase of the horse-whale or walrus.He says that as many as sixty were killed by six menin a day.2Their ivory and skins were chieflyvaluable. He notices the port of Sciringshall in theWick, which would have been the chief emporium forNorthern Danes and Goths, and of Heaths (the laterHeath-by), which was no doubt the main tradecentrefor Saxons, Danes, and Goths. He gives anaccount of his own voyage to Beorma-land, anexpedition of fifteen days' sail, being three days tothe furthest whale-fisheries' station used, and threemore days thence to North Cape; four days thenceto where the land lay east, and again five days upthe White Sea, running south, where he reached1This Oht-here bears a name found chiefly in connexion withthe famous family from Haurda-land, the patriarch of which isHaurda-Care. He is evidently one of the last settlers inHaloga-land, for he dwells northernmost, as he told Alfred.For an Oht-here, known as Oht-here the foolish, the curiousgenealogical poem " Hyndla's Lay" was composed. Thefamily of Haurda-Care is later connected with the Orkneys,wherein descendants, if anywhere, should exist.2 I take it, the clause about the big whales is simply transposedhere. Oht-here is talking of walruses, but the scribehas put into the middle of his talk another bit of informationabout big whales. It may have been taken, we might guess,from Alfred's rough notes in the Hand-book.

20 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINthe peopled and settled land of the Beormas orPerms.Oht-here makes it a month's sail, stopping everynight, from his home to Sciringshall, and six days thenceto Heath-by. His account of his own wealth is noteworthyhe;had 600 rein-deer he had bred or caught," unbought," as he says, 6 stale or dec9y deer, 20 headof neat and the same number of sheep and swine.He has horses, too, which he uses for ploughing, arare thing in those days, but how many, he or KingyElfred forgets to tell us.A border warfare, probably chiefly carried on bythe outlying Northern settlers, Neams, Throwends,and Haloga-landers, against the Cwsens, a tribe ofFinnish affinities, is also spoken of by Oht-here.He says the Cwaens used to bring their light boatsup on to the inland lakes of the <strong>Scandinavian</strong>peninsula.And voyages like Oht-here's were not singular cases.The Story of Kings Heor and Half, found in Are'sLandnama-b6c as well as appended to the later HalPs-Saga and Sturlunga-Saga, tells how a king of theRugians and Haurds went warring on the land of theBeormas or Perms, and wedded the Beorm king'sdaughter, Lufina. We also hear of a Tryst ofKings, held apparently at regular intervals somewherein the south of the <strong>Scandinavian</strong> land, probablyby the Gota-river mouth, a very ancient meetingplace.Such trading journeys and forays, identical in objectgain, like our adventures in the days of Elizabeth

MOTHER-LAND AND PEOPLES 21needed trained men, seamen, and fighters, and wemight even without expressevidence be sure thatevery small folk-king and nobleman kept up aslarge and well-equipped a comitatus as he couldsupport.The character of the peopleof the west coast ofin some measure by certain poems inNorway about the end of the eighth centuryis illustratedthe Eddie collection,which we take to be of earlier date than therest, and which, unlike the rest, bear pretty plainmarks of Norwegian origin. From these it ispossible to get a picture of the population whence theWicking emigrant carne it is of a;type which we prideourselves upon as essentially British a sturdy, thrifty,hard-working, law-loving people, fond of good cheerand strong drink, of shrewd, blunt speech, and a stubbornreticence when speech would be useless or foolish ;a people clean-living, faithful to friend and kinsman,truthful, hospitable, liking to make a fair show, butnot vain or boastful ;a people with perhapslittleplay of fancy or great range of thought, but coolthinking,resolute, determined, able to realise theplainer facts of life clearly and even deeply. Of coursesome of these characteristics are those common toother nations in their rank of development, but takentogether they show a character such as no other raceof that day could probably claim, and enable us tounderstand how that quiet storage of force had goneon which, when released, was capable of such results,as the succeeding three centuries witnessed withamazement. The following proverbs in verse are

22 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINcited from such poems as the "Guest's Wisdom," 1" Lodd-Fafne's, or Hoard-Fafne's, Lesson," 1 "TheSong of Saws," l and the " Old Wolsung Lay."Anything will pass at home.Anythingis better than to be false.He is no friend to another that will only say onething [that which is pleasing],A fool when he comes among men,It is best that he hold his peace.No one can tell that he knows nothing,Unless he speaks too much.An unwelcome guest always misses the feast.A man should be a friend to his friend,And requite gift with gift.He that woos will win.Fire is best among the sons of men,And the sight of the sun,His health if a man may have it,And live blameless :A man is not altogether wretched though he be of illhealth ;Some such be blessed with sons,Some with kinsfolk, some with wealth,Some with goodMan deeds.is man's delight.Many a man is befooled by riches.Middling wise should every man be,Never overwise,For a wise man's heart is seldom glad,If he be all-wise.No man but has his match.No man is so good but there is a flaw in him,Nor so ill that he isgood for nothing.A man should be a friend to his friend,To himself and his friend ;1These three poems are found in the Eddie collection ofthe Copenhagen MS. Codex Regius, all jumbled together,with bits of other poems, under the " title Hava-mal, theHigh One's Speech." See Corpus Poeticum Boreale [cited lateras C. P. B.], vol. i., pp. 1-23 and 459-463,

MOTHER-LAND AND PEOPLES 23But no man should be the friendOf the friend of his foe.Men should give back laughter for laughter,And leasing for lies.Bashful is the bare man.Better quick than dead :A live man may always get a cow ;The halt may ride a horse, the handless drive a herd,The deaf fight and do well :Better be blind than burnt \i.e., dead and gone],A corpse isgood for naught.Cattle die, kinsmen die,One dies oneself;I know one thing that never dies,The renown of a dead man.Folly he talks that is never silent.Gift always looks for return.Give and give-back make the longest friends.No better baggage can a man bear on his wayThan a weight of wisdom.One's own house is best though it be but a cottage,A man is a man in his own house.Only the mind knows what lies next the heart.Open-handed bold-hearted men live best,But the sluggard and the coward fear everything.The coward thinks he shall live for everIf he keep out of battle ;But Old Age will give him no quarterThough the spear may.The herds know when they must go homeAnd get them out of the grass,But the fool never knowsThe measure of his maw.To these morsels from "The Guest's Wisdom,""The Song of Saws," which especially inculcatesprudence, will give a supplementary course :At eventide praise the day, a woman when she is burnt[i.e., dead and gone],A sword when it is proven, a maid when she is married,Ice when it is crossed, ale when it is drunk.

24 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINLet no man trust an early sown acre,Nor too soon in his son.Weather makes the acre and wit the son ;Each of them is risky.A creaking bow, a burning blaze,A gaping wolf, a cawing crow,A grunting sow, a rootless tree,A waking wave, a boiling kettle,A flying shaft, a falling billow,Ice one night old, a coiled snake,A bear's play, or a king's son.A burnt house, a very fast horse,For the horse is useless if one leg be brokenBe no man so trusting as to trust one of these. 1. . . The tongueis the death of the head.There is often a stout hand under a shabby coat.The weather changes often in five days,But more often in a month.From " The Lesson of Lodd-Fafne," which isdidactic throughout, one may cite:Never bandy words with fools.Never laugh at a hoary counsellor.Know this, if thou hast a friend in whom thou trustestGo and see him often,Because with brambles and with high grass is chokedThe way that no man treadeth.Be thou never the firstTo break with thy friend.Shoe-maker be thou not, nor shaft-maker,Save for thyself only ;If the shoe be ill-shapen, or the shaft crooked,Thou gettest ill thanks.1Shakespeare knows by tradition a bit like this :" He that trusts in the tameness of a wolf," &c.King Lear. Act 3. Scene 8.

MOTHER-LAND AND PEOPLES 25There is much in Hesiod and Theognis and evenin Pindar and the Greek tragedians that runsto these saws.The old Play of theof the like type :Wohungs givesparallelseveral maximsManifold are the woes of men.No man knows where he may lodge at night ;111 it is to outrun one's luck.Not many a man is brave when he is oldIf he were cowardly as a child.The doomed man's death lies everywhere.A good heart is better than a strong swordWhen the wroth meet in fray,For I have often seen a brave manWin the day with a blunt blade.The cheerful man fares better than the whinerWhatever betide him.All evils are meted out [by fate].The home verdict is a parlous matter.Wine is a great wit-stealer.Most miserable is the man-sworn.These examples of popular lore form no bad indexto the feelings and ideas of the men and women inwhose mouths they took shape and life. What hasbeen said and cited above may give some index alsoto the material state of culture reached by thosewest-coast folk. The finds in Scandinavia and Denmarkshow that as early as the third and fourthcenturies many of the Roman implementsof metalhad reached the North, which had long been inthe possession of bronze weapons. .Iron weaponsand tools were known and used in the North asfreely almost as in <strong>Britain</strong> or Gaul, and in dress,

26 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINfood, and handicraft the <strong>Scandinavian</strong> differed littlefrom his cousin the Englishman, who had precededhim in his western exodus. Only in cultivation ofland, and possibly of cattle, was the <strong>Scandinavian</strong>of the northern peninsula behind-hand. The Englishmanhad succeeded to the system of agriculture setup by the Romans in <strong>Britain</strong>, whereas the -<strong>Scandinavian</strong>stillpossessed the more primitive cultivationof the early Teutons, and dwelt in a land that wasstill but half reclaimed from the forest. In art the<strong>Scandinavian</strong> had already developed a peculiar typeof ornament, of which the bronze collections atCopenhagen, Stockholm, and Christiania preserveample specimens, 1 a type which, while it runs parallelto the Celtic metal work, has markworthy characteristicsof its own.Though writing was not used for books or letters,yet the art of writing was known, and weapons, gravestones,and ornaments have inscriptions on them.The peculiar letters known as runes are of the oldergeneral North and West Teutonic type, derived fromsome classic alphabet (that of an Hellenic Black Seacolony possibly, as Canon Taylor thinks the North;Etruscan alphabet, as Professor Bugge believes; oras Dr. Wimmer with less probability affirms, from theLatin alphabet).The letters were arranged in an order, the reasonfor which is as yet unknown,as follows :1The illustrated catalogues of these museums are cheap andgood, and will give the English student fair means of studyingthe finds in Scandinavia in connexion with those of <strong>Britain</strong>.

MOTHER-LAND AND PEOPLES 27F, U, Th, A, R, C, G, W,H, N, I, J, E?, P, S, Z,T, B, E, M, L, Ng, O, D.The characters used for F, Th, A, R, T, H, B,M, S, E might come from several of the classicalalphabets ;those for U, C, G, W, J, L, Ng, O, arecertainly Hellenic rather than Latin, correspondingwith the Greek O, r, X, Y, early I, A, IT (as inGothic), O. The character for D DD is placed backto back, and other compounds were added later.The names of these letters, as in our own children'salphabets and other old alphabets, were taken fromsome object with like initial. T was the god Tew,N was nail, H hail, I ice, while (as in Irish) B wasbirch, Th thorn (earlier perhaps, Thurse orgiant),Yyew.The use of these runes in the North differed littlefrom that of the same alphabet in England duringthe sixth, seventh, and eighth centuries. Bracteatesimitative of Roman or Greek medals or coins,memorial stones, implements and ornaments wouldbe engraved or scratched with these letters. Thepossession of the knowledge of writinghad littleeffect upon the people of either countrytill theirold alphabet was superseded by the general West-European Roman alphabet, which, as we shall see,came into the north with Christianity, and soonproved in Iceland and Denmark, as it had in Ireland,England, and Germany, a new factor in civilisation.

28 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINIII.THE WICKING FLEETSThou Sea that pickest and cullest the race in time, and unitestnations,Suckled by thee, old husky nurse, embodying theeIndomitable, untamed as thee.THE development of national life in Norway, consequenton the increase of trade and population, bythe end of the eighth centuryis shown by the growthof tribal leagues, and by the increased appreciationof common laws and common peace over large areasthat rendered possible the career of the lawyer king,Halfdan the Black, who succeeded in establishing akind of imperial sway over a broad territory, hithertoparcelled out under small tribal kings. But forour present purpose the points to dwell on are theimprovement of the ship and war organisation.The earlier Swedish graven stones, anS earlier boatshaped,stone-marked graves, show that, as Tacitustells from the report of some Teuton traveller orcaptive of his day, the Suiones [Swedes] had fleets ofboats, with prows at either end, but without sailsor regular row of oars. These were long canoesprobably shaped of wood and skin-covered wattle,and moved by paddles. But the Ueneti of Brittany,at least as early as 60 B.C., had already, helped nodoubt by seeing some foreign models (possiblyCarthaginian galleys), got to building vessels thatwould stand the rough weather of the Atlantic, and

THE WICKING FLEETS 29were principally moved by sails. Caesar describesthem as made wholly of timber and strongly built,with iron bolts and iron cables, and leather sails.He says they were more flat-bottomed than theRoman ships for the convenience of the light draughtof water, that they had tall prows, and a quarter deckconsequently rather high. He describes them as goodsea boats, able to withstand even the shock of beingrammed, hard to grapple with or board, because ofthe height of their fighting deck, but not so fast asthe Roman row-galley.The <strong>Scandinavian</strong>s worked out the problem ofbuilding a boat, handy, fast, safe, and suited to theirown coasts and seas, in their own way, having seenfrom the Roman galleys that, under Drusus and otherRoman commanders, operated in the North Seas inthe first century, possibilities of better craft thanthose they had hitherto had. The sail-less, seamsewn,paddled canoe gives way to the ribbed andkeeled clinker-built boat with mast, yard, sail, siderudderand oars.The Roman galley may be described as a long, low,narrow hull, like that of a modern canal-barge, witha pair of light, long boxes fitted to the uppermosttimbers on each side. In the hull were the storesand ballast; in it was stepped a mast fitted with ayard and square sail fore and aft were half; decks,joined by a narrow platform running between. Therudder, a broad oar fixed to the starboard quarter,was steered from the quarter-deck. In the side boxesthe oarsmen sat and pulled the long narrow-bladed

30 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINsweeps that were the chief motive power of thegalley, and could drive the bronze-beaked prow, thatwas fixed to the curving end of the keel close to thewater, at a deadly rate into the enemy's quarter, orthrough his extended oarage. From this model the<strong>Scandinavian</strong> took the mast, sail, rudder, and possiblyoar, but he did not servilely copy the build, whichwas unsuited to the Northern Sea, though admirablyadapted to the Mediterranean, where it had beenperfected by the Greeks.The finds of the last fifty years enable us to seefor ourselves what manner of ships the Norwegiansailors who were the first sailors to make long runsout of sight of land, and to cross the North Sea andAtlantic regularly year by year built and sailed.From the Nydam boats of the latter part of thethird century, by which time the type was alreadyformed, to the Gokstad ship of the eighth century,which representsit in its perfection, the chain ofevidence iscomplete for Sweden and Norway andthe Baltic coasts. We can see before us in thesecraft, the very kind of ship such as the Byzantinehistorians tell us threatened new Rome, the greatcity, Mickle-garth, from the middle of the ninth tothe middle of the tenth centuries, built with plankson a keel of a single tree sixty feet or more in length :masted, ruddered, holding from twenty to forty men,with weapons, water, and food. The Nordland boatof the Norwegian fisherman to-day is almost identicalin all essentials to the wicking ship of a thousandyears ago.

THE WICKING FLEETS 31The main peculiarities of the Norwegian wicldngship of the " iron age " may be summed up somewhatas follows, from the Gokstad ship, the latest andmost perfect. She was 67 feet long at keel, and 79^feet from stem to stern \of 1 7 feet beam, and about4 feet depth amidships ;clinker-built of eight strakesof solid oak planks fastened with tree-nails and ironbolts, and caulked with cord of cow hair plaited ;herplanks are fastened to the ribs with bast ties, whichgives the frame-work great elasticity. She is undecked(possibly there were lockers fore and aft),with movable bottom boards whereunder could bestowed ballast, stores, weapons, sails, spare spars andoars, and the like ;her mast was stepped in a hugesolid block, which is so cunningly supported that,while the mast stands steady and firm, there is nostrain on the light elastic frame of the ship. Heroars, sixteen a side, pass through rowlocks cut in themain strake (the third) and neatly fitted with shuttersagainst bad weather; the oars are twenty feet long,and beautifully shaped. Her rudder, stepped to thestarboard quarter, is a large short oar of cricket-batshape, fitted with a movable tiller, and fastened to theship by a curious but simple contrivance, giving theblade play, and keepingit clear of the ship's side.The mast, which is a 40- feet stick, has a heavy longyard with square sail, the stays and rigging are ofbast, the mast and yard when shipped lay on twocrutches clear of the deck the ; awning was of tentlikeform, of white web with red stripes, fitted withhemp cords by which it was seized 'to the ship's sides

32 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINand to its x shaped supports, and the pole thatstretched between them parallel to the keel. Twosmall boats, one masted, of similar type accompanythe Gokstad ship; they are of 22 J feet and 14 feetkeel respectively. A cauldron with chain for cooking,an iron plate for carrying lamp or fire safely, cups,buckets, a landing plank or bridge, bedstead, an ironanchor, kettle, platters, and a draughtland morrisboard with men were found aboard her.This description will serve fairly for the Nydamboats [two oak, one fir)of the third century, and theTune boat (oak) which is plainly of the fifth, savethat the Nydam boats are none of them masted, andone of them, the fir one, was probably fitted with aspur to one end of the keel. The biggest Nydamboat was of 60 feet keel, 77 feet between stem andstern, lof feet beam, and about 3^ feet depth; shehad a large piece of wickerwork for her bottom boards,she had five strakes, and was clinker-built. 2The Tune ship was of 45 1 feet keel, 14 \ feet beam,and about 3 feet depth clinker-built of;of six strakes,oak, caulked with cow hair and pitch, masted, and sideruddered.All these boats, save the Gokstad ship, had the1The draught game was not our sixty-four square game, butthe older one, probably the same as that played to-day in manyparts of the East.2The Nydam boats found in a moss, once an arm of the sea,were probably a votive offering (of the kind mentioned byAmmianus, Tacitus, and Adam of Bremen) after a victory. Thecoins of Macrinus, 217 A.D., give the highest upward date.There were beautiful damascened iron swords and some arrowshafts, rune-inscribed.

THE WICKING FLEETS 33characteristic rowlocks of the Nordland boat, a crutchof tough wood JL seized with bast to the upper strake,with a loop of bast to prevent the oar-loom fromslipping in getting forward.We have in these beautiful vessels, and in the lesswell-preserved relics which have been discovered byThames, or Lea, or Seine, or by Southampton Water,the clearest proofs of the skill, originality, and successof the <strong>Scandinavian</strong> shipwright, whose observationand patience had been able to produce a boat able torow or sail, ride out a gale or make way in a calm,which should have " give " enough in her hull to standa shock that would stave in and sink a stiff-built boat,but be stanch enough to carry a heavy mast and sailwithout strain ;which should be of such light draughtwithout being crank or unseaworthy, as to be able tocreep into any haven, but of burthen enough tocarry fiftymen with stores and gear for a month ormore.And this model, so carefully adapted to its -conditionsof use, held its own till the twelfth centurywhen the heavy, slow, carvel-built mediaeval cog tookits place as a vessel of burthen and war. The famousLong Serpent of Anlaf Tryggwason, built in 996 byhis shipwright, Thorberg Shafting at Lathe-hammer,with a 74 ell (148 feet) keel and 34 benches, was perhapsthe highest pitch of perfection to which anyvessel on these lines ever attained.To handle such craft as the Gokstad boat so as toget the most out of her and keep her out of dangerin a galein the North Sea, or a squall off thec

34 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINcoast, 1 needed good sailors and trained men, whocould and would obey orders, and act together at amoment's notice. The whale-fishery and the coastingtrade, and the buccaneering voyages to the North andup the Baltic, had trained a school of such men.In Half s-Saga we have read of his crew of " Champions,or merry men," a comitatus of picked men asgood at the helm or the oar as they were with axe orsword : and there are to be gathered out of variousearly sources some tradition of the Articles of Warand Ship's Regulations, so to speak, of these Northernwar vessels. 2No man was taken except between the two ages1 (6and 60), or in special cases between 18 and 50, or 20and 60.No man was admitted without a trial of his strengthand activity.All taken in war was to be brought to the Pile orStake and there sold and divided according to rule,and this war-booty (wal-rauf) was personal (not partof the heritage that went to a man's kindred) and wasburied with him.The crew ate and drank in messes, two or threetogether, and the cook for the day was probably, as inmerchantmen, drawn by lot or on duty in turn.Several times we hear of the Northmen suffering great loss1from heavy gales in spite of all their seamanship, e.g., on thedeadly English east coast in 794, on the south coast in 877, andat the entry of the Mediterranean.2Compare the " Laws of the Feens," as quoted in O'Curry's" Lectures," vol. ii., for the Irish counterpart to those oldTeutonic ' ' Wicking Laws. "

THE WICKING FLEETS 35There must be no feud or old quarrel taken upwhile on board or on service.Women were not allowed on board ship or inside afort.News was to be reported to the captain alone.(See Origines Islandicce^ Book II, sec. 2.)The famous crew of King Anlaf's Long Serpent (themuster-roll of which reads like that of David's mightymen) and the 45 ships' companies (last relics of thebuccaneer city of lorn) that followed Thor-cytel theTall to fight for or against /Ethelraed, or his rival Cnut,and afterward formed the nucleus of that renownedguard, the house carles of the English kings, the peersof the Warangians themselves, these were but thehighest expression of a discipline, skill, and power,that were present in more or less perfect form onboard every ship in the fleets that were the terror ofevery European coast throughout the ninth century.The fact is that ship lifegave to every free Northman much of the training and skill that were inEngland and France peculiar to the immediate following of the prince, his gesiths, antrustiones, so/ones, asthey are variously called in various Teutonic tribes.Even the personal obligation of honour to the lordthat paid and fed him, so strongly felt by the comes,was felt in some degree towards the captain of eachship by the crew.For warlike purposes, or external action of anykind, the <strong>Scandinavian</strong> lands were organised likeother Teutonic lands, the country being divided intodistricts, from each of which so many picked free

36 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINmen, one from each household, were ready for thelevy the force thus raised was called in the North;here (host),and the district heradh (host-district).Of course, in great emergencies for defensive purposes,a full levy the whole male population betweensixteen and sixty, and all horses over two years oldmight be called out, but such occasions were rare.In general the ordinary levy sufficed for all offensiveor defensive purposes. The men composingit werearmed with sword and spear, and such as had metalhead-pieces or mail-coats wore them. The axe wascarried more for work thanfor war, the sword beingthe chief weapon in close fight ;the bow isspoken ofin the poems, but more as a weapon of the enemythan of the Northman. The spear-shaft was ash,the sword iron or bronze, the shield wood or wickerstrengthened with metal and leather, the bow of yewor elm. Stones were greatly used in warfare, and asa boat's ballast was largely made up of stones, theywere to hand in such sea fights as Hafrsfirth,c. 890.Any one who knows one of our larger fishingports will have a better idea of the organisation,composition, and character of a wicking fleet thanaught else could give him. The preparation of gear,clothes, stores; the overhauling of the craft, hull,sails, rigging the; making up of the crews, the finalwith a fair breeze, the whole place emptied ofsailingitsyoung and middle-aged men for the two or threemonths that the cruise lasts; the home-coming, therejoicing, the burst of trade, the influx of riches, won

THE WICKING FLEETS 37from the sea, the steady flourishing of the wholecountry-side as long as the cruises are gainful; thebuilding of new vessels, the eagerness of the youngfor the life of adventure, unchecked by the terribledisasters that ever and anon mar the good fortuneof the fleet, disasters that may sweep away nearly allthe men folk of the place and check its growth for adozen years, such phenomena are common to ourfishing life now-a-days, and to the old Northman'sbuccaneering life so long ago. And when crossingthe North Sea one steams through the Grimsby orLowestoft fleet, hundreds of big boats out for theherring, one can form even a visible imageof what awicking fleet must have looked like as the ships ingreat groups sped out with a fair north-easter, eagerfor the work before them, or hurried homewards witha sou'-wester behind them, deeply laden with Englishand Irish gold and silver, and raiment and jewels, andslaves and wine and weapons.The "Helge Lays," best of all the Eddie poems,express the spirit of the wicking.Messengers thence the king sentover land and sea to call out the levy:Gold in good storethey ivere to 1promise the warriors and their sons."Do ye bid them get aboard forthwith,and make ready to sail from Brandey \pr Sword Island]."There the prince waited until thither there camewarriors by hundreds from Hedinsey.1Of course, when a chief or king held a levy for a wickingcruise, not a war, men came or not as they chose, and theprospect of booty and certainty of pay would be the chiefattraction.

38 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINAnd forthwith out from Stane'snessthe host stood to sea, fair and adorned with gold.Then Helge asked Heor-laf" Hast"thou mustered the blameless host?And the one king said to the other" Long were it to tell over out from Crane- EyreThe tall-stemmed ships with their crews aboard,that sailed out from larrow Soundtwelve hundred trusty men !Yet at High-town there lie as many again,the war-levy of a king. We must look for battle."The men furled the bow-awningsat the king's bidding, when the host awoke,and men could see the brow of day,and the warriors hoisted upon the yardthe striped canvas sail web,and ran upto the mast headthe woven target of war in Warin's firth.Then there came the oars' plash and the irons clash,clattered shield on shield the wicking soundWith foaming wake under the crews there ranthe king's fleet far out from land.It was to the ear when they came together,Colga's sisters [the billows] and the long keels,as if the surf were breaking against the rocks.Helge bade them hoist the top-sails higher.The seas held tryst upon the hulls,as Eager's dreadful daughter [the ocean wave]strove to whelm the bows of the helm-horses ;but the heroes themselves Sigrun [the Walcyrie] from abovethat battle-bold lady kept safe and their craft also.It was wrested by main strength out of Ran's handsthe king's brine-beast off Cliff-holt,so that at even in Unesvoethe fair-found fleet was riding safely.But the sons of Gran-mere from Swarin's howeoffHarm mustered their host.Then made enquiry Godmund the god-born," Who is the prince that steers the shipwith a golden war-banner at his bows ?No shield of peace methinks do I see in the van,but war-targets in a row wrap the wickings about."Helge Lay, i. 80-127.

THE WICKING FLEETS 39And, again, another passage by the same poetruns :There are turning hither to our shore lithe keels,ring-stags [ships] with long sail-yards,many shields, shaven oars,a noble sea-levy, merry warriors.Fifteen companies are coming ashore,but out in Sogn there lie seven thousand more.There lie here in the dock off Cliff-holtsurf-deer [ships] swart-black and gold adorned.There isby far the most of their host.Helge Lay, i. 197-206.The following piece of dialogue between the hero,Helge, and the Walcyrie, Cara, is also characteristic :CARA. Who are ye that let your ship ride off the shore ?Where, warriors, is your home ?What do ye wait for in Bear-bay ?Whither are ye bound ?HELGE. It is Hamal that lets his ship ride off the shore.We have a home in Leesey.We wait for a fair wind in Bear-bay.Eastward are we bound.CARA. When hast thou wakened War, O king,and sated the birds of the sister of Battle?Why is thy mail-coat flecked with blood ?Why eat ye raw meat, helmed ?HELGE. That was the last deed of the Wolfing's sonswest of the main, if it like thee to know,1when I slew Beorn in Woden's grove,and fed the eagles' brood full with my spear-point.Now I will tell thee, maiden, why our meat is raw ;We get little roast steak at sea, maiden.Helge> iii.1Brage's grove is exactly equivalent to Woden's sacred wood,or Odinse island.

40 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINAnother piece of dialogue of the same typeisprobably by the same poet :NICKAR (Woden}. Who are they that are riding on Revil'ssteeds [ships]over the high billows, the sounding sea?The sail -coursers are splashed with foam,The wave-horses cannot stand against the wind.REGIN. Here are we Sigfred and I on our sea-trees [ships]We have a fair wind for ...The steep billows are breaking high over our bows.The surge-coursers are plunging. Who is it thatasketh ?Western Wolsung Lay, 23-34.In a laterpoem of the tenth century the wickingleader speaks :We were three brothers and sisters.We were deemed unyielding.We went abroad ;we followed Sigfred.We roved about, each steered his own ship.We sought adventures till we came east hither.We slew kings ... we divided their land.Nobles came to our hands [did homage to us] it betokenedtheir fear.We called from the wood [inlawed] him whom we wished tojustify.We made him wealthy that had nought of his own.Greenland Attila Lay, 354-6.Of the details of wicking warfare it is also possibleto collect some information from our authorities.The regular formation of troops in wedge or line(acies or cuneus, as Tacitus gives it)was known.The crew of a single ship seems to have been thetactical unit; these were massed in battalions orto whombrigades under the banner of the earl or kingthe fleet belonged. The captain of each ship led his

THE WICKING FLEETS 4 1own men, his second in command was the captain ofthe forecastle, or stem-man, who was apparently entrustedwith the night-watch when the ships were1lying off the shore.Horses were used to ride on forays or to battle,but all fighting was on foot the North and West;Teutons had not learnt the art of fighting on horseback,which their Eastern brethren, the Goths, were,the first to practise. The quickness of their movements,on board ship or on horseback, was one ofthe causes that led to the marvellous successes ofthe wickings even in lands like Gaul and <strong>Britain</strong>,where there were good roads of Roman make.By night the warriors went forth, studded with their mailcoats,their shields shone in the light of the waning moon.They alit from their saddles at the Hall-gable.WeylancTs Lay, 27-29.There were three kinds of warlike operations ;stratagems, such as night-attacks, ambushes, woodbarricades,surprises, assaults with fire, such as hadalways formed part of Teutonic warfare and feud :battles, regular pitched fights, for which a place andday were named and a fair trial of strength made ;and sieges. These were conducted both by blockadeand assault, the Northmen and Danes having ample1See, for instance, C. P. B.,i.151, Flyting of Attila andRimegerd, n, 12, and 45, 46:RIMEGERD. The prince must trust thee well to let thee standat his ship's fair stem.ATTILA. I must not go hence till the men waken,but keep ward over the king.

4 2 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINskill (being expert carpenters and shipwrights) inmaking palisades, shelter-works, wooden towers forassailing tall walls, and the like, and good knowledgein throwing up earthen lines and dykes, diggingtrenches, and making portages to haul their ships overdifficult ground, in those cases where the use of fire, orfair words, or a sudden and bold attack was impossible.The numbers of the hosts varied greatly, butreckoning the average crew as forty men and upwards,we hear 'of fleets of hundreds of ships. These largefleets were made up of lesser fleets, two or threesailing together on some enterprise too weighty forone sea-king's command to deal with. There wereseldom less than two leaders, each a king or king'sson, to a fleet, and usually two captains to each vessel,one to each watch, no doubt. This had its use inlessening the chance of a commander's death breakingup the expedition, or leading to disaster in battle.Itmay be noted that Earl is used for the first time,itseems, as a technical term for a leader of less rankthan king, in these wicking voyages, and in the ninthcentury. It is especially used by the North-men ;the Danes are led by sea-kings.lCf. B.M. Anglo-Saxon Coin Catalogue, C. F. Keary, No.11077, p. 230. Sitric Coins.

SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINI. THE EARLIEST RAIDS"WHILST the pious King Bertric was reigning overthe western parts of the English, and the innocentpeople, spread through their plains, were enjoyingthemselves in tranquillity and yoking their oxen tothe plough, suddenly there arrived on the coast afleet of Danes, not large, but of three ships only: thiswas their first arrival. When this became known, theking's officer, who was already dwelling in the town ofDorchester, leaped on his horse and rode with a fewmen to the port, thinking that they were merchantsand not enemies. Giving his commands as one thathad authority, he ordered them to be sent to theking's town ;but they slew him on the spot, and allwho were with him. The name of this officer wasBeaduheard. A.D. 787. And the number of yearswas above 344 from the time when Hengist andHorsa arrived in <strong>Britain</strong>."Such was the tradition, a century and a half later,of the beginning of <strong>Scandinavian</strong> <strong>Britain</strong>. ^Ethelwerd,ealdorman and historian, who wrote the notice, hadaccess to special sources of information, such as theroyal family to which he belonged must have preserved ;and his story tallies with the shorter entry of the43

44 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINChronicle that " 'three ships of Northmen [MS. A, ofDanes ']came from Hserethaland ;and then the reeverode to the place, and would have driven them to theking's town, because he knew not who they were andthere they slew him."If there isany discrepancy between the two tales,/Ethelwerd's has the advantage. For a century afterthis date the word " Northmen " is not used of theVikings in the English chronicles. The entry is aninterpolation, about which it is hardly worth inquiringtoo minutely. The date, usually given with definitenessif not with accuracy in the Chronicle, iswanting we;are only told that it was in the reign of King Beorhtric.The placeis not named, whereas the annals areotherwise careful to name the sites of battles, thoughwe cannot always identify them.The three ships aresuspiciously like the three keels of Hengist and Horsa,to whom ^thelwerd actually refers ;he also givingfor date only the marriage of Beorhtric, in whose daysthe event happened. There must have been somesong or story of a raid, which an editor of chronicleshas tried to turn into history. The word " H^erethaland "does not appear in the Chron. MS. A, and is a laterinsertion into an entry which itself is an interpolation.Consequently, it is useless to build a theory of thehome of these first Vikings to hold, with Munch,that they came from Hardeland in Jutland, or, withothers, that Hordaland, the country of the Hardangerfjord in Norway, is meant.This is not the only instance of doubtful or fallaciousstatement in the history of the Vikings in <strong>Britain</strong>, as

THE EARLIEST RAIDS 45we find it in old writings and in modern authors.Any account of the period must be tentative andprovisional, depending on annals and sagas whichcannot be trusted implicitly, and on inferences whicha wider knowledge may upset. But there is one classof misstatements which ought tobe cleared away atthe beginning the wide-spread belief in the prehistoricViking. There is no reason to assert that<strong>Scandinavian</strong> sea-robbers, as distinct from the Anglesand Saxons of the fifth and sixth centuries, appearedon the coasts of <strong>Britain</strong> before the end of the eighthcentury.In a well-known book, justly popular on account ofits wealth of illustration, the late Paul du Chaillu usedthe argument from this doubtful entry of " Northmenfrom Haerethaland " to enforce his idea that the " socalledSaxons," as he was careful to call them, wereprecisely the same people as the <strong>Scandinavian</strong> Vikings,whose sagas, he remarked, never called the English" Saxons," as the Celtic nations did. He contendedthat from Roman days to the twelfth century there wasa continuous stream of invasion setting in from theBaltic shores to <strong>Britain</strong> ;littus Saxonicum was aViking settlement the ; English came from Engelholmon the Cattegat, and from places named Engeln inSweden ;Tacitus mentioned the boats of the Suiones,"and surely their mighty fleets " must have beenemployed between the days of Agricola and those ofCharlemagne in more than local traffic; the wholemillennium was a Viking Age.Burton also (Hist. Scotland, i. 302) wrote that

46 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAIN"droves of them (Scando-Gothic sea-rovers) cameover centuries before the Hengest and Horsa of thestories, if they were not indeed the actual large- boned,red-haired men whom Agricola described to his sonin-law."He supported his theory with a reference toDr. Collingwood Bruce, the historian of the RomanWall, who, describingan altar found near Thirlwallabout 1757, said: "Hodgson (the historian ofNorthumberland)remarks thatOdin, as we find in the Death-songVithris was a name ofof Lodbroc . .If Veteres and the <strong>Scandinavian</strong> Odin are identical,we are thus furnished with evidence of the earlysettlement of the Teutonic tribes in England." Butthis altar, and another he mentions from Condercum(Ben well Hill, Northumberland.), compared with altarsnow at Chesters on the Wall, and inscribed " DibusVeteribus," are more likelyto have been dedicated" To the Ancient Gods " than to the Vidhrir of theEdda, many hundred years later. Huxley (in Laing'sPrehistoric Remains of Caithness] suggested that byanthropological evidence, long before the well-knownNorse and Danish invasions, a stream of <strong>Scandinavian</strong>shad come into Scotland ;Professor Rolleston connectedthe Round-headed men of the Bronze Age in Yorkshirewith Denmark, but this refers to the racial originof tribes three thousand years ago. Such facts do notsupport speculation, misled by the hope of findinggrains of truth in Ossianic poetry, Arthurian legendand late <strong>Scandinavian</strong> sagas, in all of which there isthe same tendency to antedate incidents and to losethe perspective of history.

THE EARLIEST RAIDS 47The Ossianic poems are full of references toLochlann and the Norse as the opponents of Fionnmac Cumhall, whom Macpherson curiously called"Fingal," which means " the Norseman," and a ^aspersonal name was introduced and used by thea pirate)Vikings. Irish and Hebridean folklore relates thatbefore the Christian era the islands were ruled by seakingscalled Fomorians (homfom/wr, agiant }and popularly identified with the <strong>Scandinavian</strong> pirates.The confusion existed in old Irish historians ;DualdMac Firbis, writing in the seventeenth century andfollowingauthors of the fourteenth and fifteenthcenturies, in his tract on the Fomorians and theLochlannachs (edited by Prof. Alex. Bugge, Christiania,1905) classed them together, though he knew that" the Fomorians were the first who waged war againstthe country " of Ireland." The Wars of the Gaedhiland the Gaill" tells an impossible tale of themythological King Nuada of the Silver Hand andthe Fomorians who came from Lochlann or Norway :and when the Norse King Magnus Barefoot of theeleventh century became an important figure inCeltic folklore, as he was in the sixteenth century,the story-tellers found no difficulty in pitting himagainst Fionn mac Cumhall in a great battle foughton the island of Arran. Giraldus Cambrensistells the tale of Gurmundus, who, though aNorwegian, came from Africa inthe sixth century toIreland, and then invading <strong>Britain</strong>, took Cirencesterfrom its Welsh king, and ruled the realm. Now latechronicles, like the Book of Hyde and Gaimar, called

48 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINGuthorm-^Ethelstan " Gurmund " ;he held Cirencesterin 879-880. Here again we have no trace of a prehistoricViking, but only of history distorted andantedated. The grains of truth in all these Celticlegends must be looked for in the real events of theninth to the twelfth centuries.Not only in folklore, but in well-meant historicalstudy the same tendency is visible. In the Annals ofthe Four Masters under A.D. 743 occurs this entry :" Arasgach, abbot of Muicinsi Reguil, was drowned."A similar entry appears in the Ulster Annals for 747 ;meaning that the abbot of the " Hog-island of St.Regulus" (Muckinish in Lough Derg) so met hisdeath. But according to John O'Donovan's note (ed.1849) the former editor, Dr. O'Conor, had read for"Regutl," "re gallaibh," the abbot of Muckinishwas drowned "by strangers," the Gaill or Vikings,half a century before they were otherwise heard of.Following this error, Moore in his history describedan attack on " Rechrain," meaning Lambey, and thedrowning of the abbot's pigs by the Danes. "Thus,"says O'Donovan, "has Irish history been manufactured."to whom weThus, too, English history. Gaimar,are often indebted for a bright touch on our earlyannals, places the story of Havelock the Dane in thedays of Constantine, successor to King Arthur. NowHavelock is the Cumbrian legendary form of OlafCuaran, the tenth century king of York and Dublin(see pp. 138, 139), and though the story is wovenfrom early traditions, the setting is antedated.Many

THE EARLIEST RAIDS 49of the incidents worked into the Arthurian cyclemaydate from the times of /Elfred and EadmundIronside, whose series of battles with Halfdan andKniit offers analogies to Arthur's fights with theheathen. The Arthurian legend took form in theViking Age, and was put back into the "good oldtimes " according to the use and wont of storytellers,but contains some <strong>Scandinavian</strong> elements.For instance, the horse of Sir Gawain, according toProf. Gollancz, has been evolved out of the boat ofWade, the hero of the Volund myth ;Tristram andIsolt (a Pictish and a Teutonic name) seems to be alove-story from Strathclyde not earlier than the tenthor the eleventh century. That there are quite ancientCeltic myths in the Arthurian cycle is not disputed,but much of the material, as in the Ossianic legends,comes from that stirring and fruitful age ofstorm and stress when the contact of many variousraces and cultures, especially in the north of <strong>Britain</strong>,produced a really romantic era.Thus, again, has <strong>Scandinavian</strong> history been manufactured.The Ynglinga saga (chap, xlv.) tells howIvar Widefathom, who must have " flourished " inthe seventh century, subdued the fifth part of England.For Ivar Widefathom read Ivar "the Boneless" of two hundred years later, and we comenearer to historical truth, for "Northumbria is thefifth part of England," as Egil's saga says ;and thislater Ivar, though himself not entirely free from legendaryattributions, seems to have been the leading spiritof the conquest (p. 86). At the battle of Bravoll,

50 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINsupposed to have been fought about 700 A.D., KingHarald Hilditonn is said (in Sogubrof) to have hadthe help of Brat the Irishman and Orm the English.There is no great absurdity in supposing that a strayWesterner may have wandered into his service, butwhen the Fornmanna-sogurtell us that he died at theage of one hundred and eighty winters after owning akingdom in England, and this in the lifetime of Bede,the mythical nature of the story is apparent. SigurdHring, his kinsman and opponent at "Bravoll, bethoughthim of the kingdom which Harald hadowned in England, and, before him, Ivar Widefathom,then ruled by Ingjald, brother of Petr, Saxon king,"or rather (not to make the story more absurd than itneed be) the " West Saxon king," for the or p, Anglo-Saxon w, has been misread. So Sigurd invadedNorthumbria, fought battles in which Ingjald and hisson Ubbi fell, won the realm and left it under atributary King Olaf, son of Kinrik, cousin of IvarWidefathom, who was ultimately driven out by Eava,son of Ubbi (Eoppa). Munch (Norske Folks Historic^I., i., p. 281) points out that there were real Saxonkings to tally with the story ; Ingild, brother of Ini ofWessex, died :718 but the whole account seems tobe a garbled version of affairs in the middle of thetenth century, when Eirik (sometimes called Hiring,or Hring) and Olaf Cuaran were disputing the kingdomof Northumbria.Coming down to the threshold of history we havethe romantic figure of Ragnar Lodbrok, dragon-slayer,and son-in-law of the great dragon-slayer Sigurd Faf-

THE -EARLIEST RAIDS 51nisbani. He, it is said, to outdo Hengist and Horsaand the Northmen from Hserethaland, set out toconquer England with two ships. Captured by yEllaof Northumberland, he was thrown into the pitof snakes. His sons, Ivar the Boneless and hisbrethren, avenged him by the greatinvasion andconquest but their ; saga embroiders the true storywith picturesque and mythical ornament. It tells howIvar the Crafty, hanging back from the first fruitlessattempt, bargained with ALlla. for as much land asan ox-hide would cover, the old Hengist and Horsaplot.Thus founding London (or York), he gained./Ella's confidence, brought his brothers' army back,and avenged his father with the torture of ./Ella andSt. E-admund. The episodeis not made more historicalby placing the scene in Ireland, as Haliday (<strong>Scandinavian</strong>Dublin^ p. 28) tries to do. A historic Ragnarwas present at the siege of Paris in 845, and Ivarwith his brethren conquered East Anglia and Northumbria;but the legendary part of the saga is merely onevariant of the inevitable myth of explanation, inventedto show why the Vikings attacked <strong>Britain</strong>, othervariants being Roger of Wendover's tale of Bernethe huntsman and Lothbrok, and Gaimar's of BuernBuzecarle.It must be evident that such legends of prehistoricVikings Celtic, English and <strong>Scandinavian</strong> are thenatural growth of the story-telling genius at an agewhen the great movement was past. After every warwe have a crop of novels about it. At the sametime, the fact of piracy was no invention of the

52 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAIN<strong>Scandinavian</strong>s. Thucydides has described exactlythe same circumstances in the ^Egean at the dawn ofGreek history. Carausius in the third century of ourera was a sea-rover. St. Patrick was carried from<strong>Britain</strong> by pirates of the fourth century, and escapedfrom Ireland to Gaul in a merchant-ship. The life ofSt. Columba is full of sea-faring; the "Celtic horrorof the sea" did not exist in the fifth century, whenthe monks travelled far intheir skin-boats and sailorsfrom Gaul visited lona, when Ere stole the seals inthe monastery's preserves, and Joan mac Conal playedthe pirate among the Hebrides, as Adamnan relates(Life of Columba, i. 28, 41ii.; 41). These earlynotices of piracy among Celts, with the fact that onemonastery fought another and that Irish kings attackedchurches and slew monks, regardless of religiousawe, surely explain the massacre of Eigg(A.D. 617), in which Prof. A. Bugge sees a proof of<strong>Scandinavian</strong> presence at a very early date ( Vikingernei-P- I 37)- The two stories of this event one, thatthe monks trespassed on the pastures of the queen ofthe country and suffered in consequence; and theother, that pirates of the sea came and slew themare ingeniously reconciled by Skene (Celtic Scotlandii.153), but neither account requires the appearanceof Norse or Danish vikings. There was continualsea-faring and piracy among the natives and moreimmediate neighbours of our sea-coasts. St. Columban,in the sixth century, was sent in a merchant shipfrom Nantes to Ireland, and Bishop Arculf in theseventh century went from France to lona on board a

THE EARLIEST RAIDS 53trading-ship. In 684 Ecgfrith of Northumbria senthis army, under Berhtred, to Ireland, and ravagedMagh-breg, and in 685 Adamnan sailed to Englandto buy back the captives. In 728 the FourMasters mention a" "marine fleet of Dalriadawhich attacked Inisowen in Ulster. The Englishand Irish were already showing the example of thevery deeds they lamented with such bitterness alittle later. Is it to be supposed that no word ofsuch events reached Scandinavia, when the chiefsea-traders of the age were the Frisians, near neighboursof Denmark ?Why, one may ask, did notthe Viking raids begin sooner?As a matter of fact, they did; but we have norecord stating that they reached <strong>Britain</strong>. About515 King Chochilaicus, as Gregory of Tours callshim, or Hugleik, led a fleet from the Baltic to themouth of the Meuse or the Rhine, and was overcomeand slain by Theodebert, son of the Frankish kingTheodoric. This isBeowulf s Hygelac, king ofGoths ;and the existence of Beowulf shows thatthere was early connection, other than hostile, betweenScandinavia and England. But the invasion ofHugleik, like the Anglo-Saxon settlement, was a partof the great " folk- wandering " movement, not aViking raid of a few pirates adventuring for slaves andgold. Professor Alexander Bugge, in his recent worksVikingerne, i., 1904, and Vesterlandenes Inflydelsepaa Nordboernes i Vikingetiden, 1905, points outthat the period of Hugleik was full of such enterprises.Fifty years later (565)the Danes made a

54 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINsimilar expedition to the western seas from theirheadquarters in Sjseland at Leira, where was theroyal hall, named, from the antlers of deer at itsgables, Heorot) or Hart. Here King Hrodgar (Roar),son of Halfdan, and his nephew Hrolf Kraki, theSkjoldungs, fought the Hadobards from the Eastand drove them away; but in the end misfortunecame to the burg of the Skjoldungs, and Hrolf fellwith his men. Danes and Swedes in the folkwanderingepoch were already conscious of somecollective nationality ;race-union was begun while;the inhabitants of Norway were scattered into separatetribes and petty kingdoms until the beginning ofthe true Viking age. The first steps to extensionof power westward must naturally have been takenrom Denmark as a centre, the Swedes pushing eastto Russia. But Professor A. Bugge also thinks,agreeing with H. Zimmer, that the Norse of Norwayhad found their way across the sea to the Orkneys andShetland a hundred years before the Viking attacks arerecorded in England and Ireland. There seems tobe no reason to doubt that they did adventure on thehigh seas somewhat sooner than the usually assigneddate; for Dicuil, writing about 825, describes islandsdivided by narrow channels and swarming with sheep,which seem to be the Faeroes (sheep-isles), as inhabiteda century before by Irish monks, but thendeserted on account of heathen pirates ; and, in fact,the colony of Grim Kamban was made in 825. Butby then the Viking Age had begun and Prof. A.;Bugge would put their advent in <strong>Britain</strong> much earlier.

THE EARLIEST RAIDS 55His views (Vikingerne,i.p. 134) may be summarisedthus :Long before Ireland was attacked, viz. A.D. 700 orearlier, men from south-western NorwayHordaland,Ryfylke, Jaederen, and neighbouring settlements,may have sailed over the North Sea and landed inOrkney and Shetland. Several Shetland place-namesare formed in a way which had gone out of fashionwhen Iceland was colonised, 'as Dr. Jakob Jakobsennotes (in Aarbb'ger for nordisk Oldkyndighed, 1902).Further, the Viking Age settlers had owned their landso long that they could call it their odal or udal^ andthe tradition was that jarl Torf-Einar took the odallands away from the boendr, who got them back fromSigurd Hlodver's son ;whereas in Iceland, colonisedlate in the ninth century, no such word as odal isused : the Icelanders who left their native countryunder compulsion had their odals in Norway, notin Iceland. With the Norse mayhave come Gotlanders;stones inscribed with the earlier runes (ofthe kind used before the Viking Age) and found inNorway bear witness to a connexion with east Swedenand Gotland, and in Gotland there is a series ofpillar-stones dating from 700 or earlier, with spiralsand other ornaments of a Celtic type, which suggestsintercourse between Celtic countries and the Baltic,possibly by way of Orkney and Norway.With regard to these three lines of argument itmight be answered that a connexion between <strong>Britain</strong>and the Baltic in early ages need not be doubted, butthat it was more likely to have been by wayof Frisia ;

56 SCANDINAVIAN BRITAINand that there has been a tendency to antedate thedevelopment of Irish decorative art Prof. A. Buggeelsewhere gives a seventh-century date to the Book ofKells and consequently to antedate the monumentssupposed to have been influenced from Ireland. Thedate of Torf-Einar's seizure of the odals cannot bemuch before the end of the ninth century, whichwould allow for two or three generations of settlersin Orkney after the period at which Dicuil indicatestheir arrival. And as Iceland was not coloniseduntil 874, the earlier years of the ninth century arefarenough back to explain archaic place-names inShetland. Beyond that epochthere seems no needto go.The true Viking Age began during the last yearsof the eighth century; and itbegan with raids onthe coast nearest to Denmark. Lappenberg, in hisHistory of England under the Anglo-Saxon Kings(Thorpe's tr., ii. p. 19), quotes an epistle of Bregowineto Lullus (who died in 786) mentioning "frequentattacks of wicked men on the provinces of the Englishor on the regions of Gaul/' It is not clear that hemeant <strong>Scandinavian</strong> pirates, but we are coming verynear to the time and place where the earliest recordedattacks did occur ;and when they once began theycame thick and fast. However untrustworthy anygiven entry may be, Irish, English, and Frankishannals unite in asserting that Viking raids, outside theBaltic, began soon after this date, and continued fromthat time forward. Within the Baltic the <strong>Scandinavian</strong>tribes had been preying upon each other for

THE EARLIEST RAIDS .57centuries: now at last theyconquer. It was not that theyGaul and <strong>Britain</strong>, but that theyfound new worlds tohad never heard ofhad not been inducedor emboldened to venture so far in small parties forthe sake of robbery under arms.What, then, was the reason, or occasion, of thissudden outburst ?Steenstrup thought that overpopulation,through polygamy, had made emigration necessary: but the earlier raids were not emigration ;andK. Maurer argued that Harald Fairhair's attempts tocheck emigration showed that Norway was not toocrowded. J. R. Green, in his Conquest of England,suggested that as the unification of the small <strong>Scandinavian</strong>kingdoms had already begun, the more independentspirits preferred adventure and exile to alienrule ; adding that it is needless to look further fora reason than the hope of plunder. But attempts atunification had begun long before this period in Denmarkand Sweden, and in Norway Harald Fairhair'sdomination came after the Viking Age had alreadyset in. The hope of plunder was no doubt the motive,but why should this date stand as the moment whensuch hopes were formed ? Others have supposed thatheathendom was making reprisals for Charlemagne'swar on the Saxons ;but this idea involves a solidarityamong the <strong>Scandinavian</strong>s, and a sentiment of religion,wholly foreign to all we know of them. The Vikingraids may have been prompted partly by hate of theChristian invader, but they were not analogous tothe Crusades; they simply meant that the peopleof the Baltic awoke to the possibilityof successful