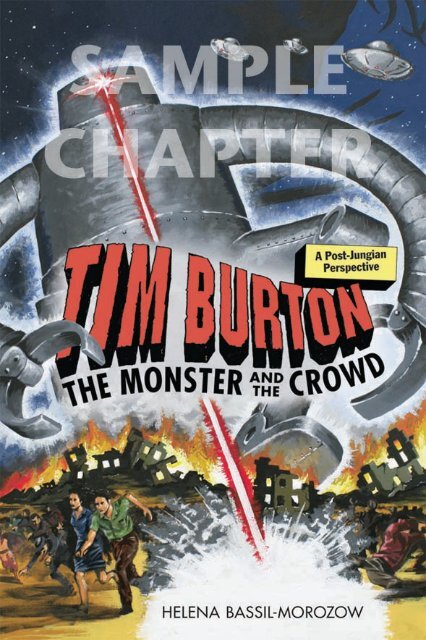

Tim Burton: The Monster and the Crowd - A Post-Jungian Perspective

Tim Burton: The Monster and the Crowd - A Post-Jungian Perspective

Tim Burton: The Monster and the Crowd - A Post-Jungian Perspective

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

First published 2010<br />

by Routledge<br />

27 Church Road, Hove, East Sussex BN3 2FA<br />

Simultaneously published in <strong>the</strong> USA <strong>and</strong> Canada<br />

by Routledge<br />

270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016<br />

Routledge is an imprint of <strong>the</strong> Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business<br />

Ø 2010 Helena Bassil-Morozow<br />

Typeset in <strong>Tim</strong>es by Gar®eld Morgan, Swansea, West Glamorgan<br />

Printed <strong>and</strong> bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd, Padstow,<br />

Cornwall<br />

Paperback cover design by Andrew Ward<br />

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or<br />

utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or o<strong>the</strong>r means, now<br />

known or hereafter invented, including photocopying <strong>and</strong> recording, or in<br />

any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing<br />

from <strong>the</strong> publishers.<br />

This publication has been produced with paper manufactured to strict<br />

environmental st<strong>and</strong>ards <strong>and</strong> with pulp derived from sustainable forests.<br />

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data<br />

A catalogue record for this book is available from <strong>the</strong> British Library<br />

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data<br />

Bassil-Morozow, Helena Victor, 1978-<br />

<strong>Tim</strong> <strong>Burton</strong> : <strong>the</strong> monster <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> crowd, a post-<strong>Jungian</strong> perspective /<br />

Helena Bassil-Morozow.<br />

p. cm.<br />

Includes ®lmography.<br />

Includes bibliographical references <strong>and</strong> index.<br />

ISBN 978-0-415-48970-6 (hardback) ± ISBN 978-0-415-48971-3 (pbk.) 1.<br />

<strong>Burton</strong>, <strong>Tim</strong>, 1958ÐCriticism <strong>and</strong> interpretation. 2. <strong>Monster</strong>s in motion<br />

pictures.3.Fantasyinmotionpictures.I.Title.<br />

PN1998.3.B875B37 2010<br />

791.4302'33092±dc22<br />

2009032724<br />

ISBN: 978-0-415-48970-6 (hbk)<br />

ISBN: 978-0-415-48971-3 (pbk)<br />

http://www.jungarena.com/tim-burton-<strong>the</strong>-monster-<strong>and</strong>-<strong>the</strong>-crowd-9780415489713

Contents<br />

Preface ix<br />

Foreword xi<br />

Acknowledgements xiii<br />

Introduction 1<br />

1 <strong>The</strong> child 33<br />

2 <strong>The</strong> monster 51<br />

3 <strong>The</strong> superhero 79<br />

4 <strong>The</strong> genius 113<br />

5 <strong>The</strong> maniac 139<br />

6 <strong>The</strong> monstrous society 159<br />

Conclusion 177<br />

Filmography 179<br />

Bibliography 185<br />

Index 195<br />

http://www.jungarena.com/tim-burton-<strong>the</strong>-monster-<strong>and</strong>-<strong>the</strong>-crowd-9780415489713

Introduction<br />

<strong>The</strong> child with a thous<strong>and</strong> faces<br />

`A poet has <strong>the</strong> imagination <strong>and</strong> psychology of a child, for his impressions<br />

of <strong>the</strong> world are immediate, however profound his ideas of <strong>the</strong> world may<br />

be,' says Andrey Tarkovsky in his self-exploratory book, Sculpting in <strong>Tim</strong>e.<br />

If <strong>the</strong> benchmark for true artistic creativity is purity of imagination, a<br />

certain naivety of outlook, freshness of vision <strong>and</strong> a stubborn faith in one's<br />

own work, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>Tim</strong> <strong>Burton</strong> passes <strong>the</strong> test with top grades. His `creative<br />

child', however, is much younger than that of Tarkovsky, in whom <strong>the</strong><br />

wide-eyed search for meaning is veiled with mature perspicacity <strong>and</strong> gravitation<br />

towards graceful existentialist symbolism. By contrast, <strong>Burton</strong>'s<br />

inner puer has not grown up into a fully ¯edged auteur. He has never<br />

mastered some of <strong>the</strong> indispensable principles of cinematic auteurism: <strong>the</strong><br />

depth <strong>and</strong> complexity of concepts, <strong>the</strong> re®nement <strong>and</strong> originality of cinematic<br />

movement or <strong>the</strong> stringent control over <strong>the</strong> narrative. <strong>The</strong> majority of<br />

his ®lms have vague, myth-like structures, <strong>and</strong> are so conceptually `uncluttered'<br />

(yet visually rich) that <strong>the</strong>y can be enjoyed by children <strong>and</strong> adults<br />

alike. Besides, his ®lms often are about children; to be more precise ± about<br />

one child, a misunderstood being whose inability (or refusal) to grow up<br />

puts him into a con¯ict with <strong>the</strong> `sensible', but senseless, society. What<br />

makes <strong>the</strong> puer different, <strong>and</strong> unique, is <strong>the</strong> ability to create new worlds ±<br />

something that `normal' people do not possess.<br />

This `outcast' image can appear in various forms in <strong>Burton</strong>'s movies: <strong>the</strong><br />

persecuted monster, <strong>the</strong> mad genius, <strong>the</strong> maniac, <strong>the</strong> un®nished young man<br />

living in his own Gothic dreamworld, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> disturbed superhero who<br />

®ghts his evil alter ego. <strong>The</strong>se guises overlap <strong>and</strong> amalgamate (`<strong>the</strong> child' is<br />

also `<strong>the</strong> monster', etc.), weaving a complex picture of <strong>the</strong> typical <strong>Burton</strong>ian<br />

male character ± a strange little boy who grows up to be a weird, but<br />

talented, mis®t. <strong>The</strong> mis®t invariably has a dark imagination, is never<br />

accepted by <strong>the</strong> common people, <strong>and</strong> is sometimes even hunted down by<br />

<strong>the</strong>m (Batman, Edward Scissorh<strong>and</strong>s, Willy Wonka). Surprisingly, despite<br />

http://www.jungarena.com/tim-burton-<strong>the</strong>-monster-<strong>and</strong>-<strong>the</strong>-crowd-9780415489713

2 Introduction<br />

his `introverted pariah' reputation, <strong>Burton</strong> enjoys great commercial success<br />

with <strong>the</strong> very `crowd' of which his characters are so wary.<br />

This book is about <strong>Tim</strong> <strong>Burton</strong>'s use of <strong>the</strong> different guises of <strong>the</strong> image<br />

of <strong>the</strong> `dark child' in his ®lms, including <strong>the</strong> monster, <strong>the</strong> genius, <strong>the</strong><br />

superhero, <strong>the</strong> maniac <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> trickster. Thus, Chapter 1 (`<strong>The</strong> Child')<br />

traces <strong>the</strong> mythological, literary <strong>and</strong> psychological roots of <strong>the</strong> image that<br />

dominates <strong>Burton</strong>'s ®lms. <strong>Jungian</strong> (mainly Jung <strong>and</strong> Erich Neumann) <strong>and</strong><br />

post-<strong>Jungian</strong> <strong>the</strong>ories are my principal tools in this chapter, which deals<br />

with <strong>the</strong> child archetype in mythology <strong>and</strong> psychology of <strong>the</strong> individual (my<br />

justi®cation of <strong>the</strong> choice of Jung over any o<strong>the</strong>r psychologies will appear<br />

later in <strong>the</strong> Introduction).<br />

Chapter 2 is devoted to <strong>the</strong> `monster' guise of <strong>the</strong> child, <strong>and</strong> covers<br />

Edward Scissorh<strong>and</strong>s, Frankenweenie, Batman Returns <strong>and</strong> Sweeney Todd. It<br />

explores <strong>the</strong> psychosocial aspects of <strong>the</strong> monster ®gure (introversion,<br />

nonconformity, disability, hatred <strong>and</strong> rejection by society, ab<strong>and</strong>onment by<br />

fa<strong>the</strong>r/God, borderline personality qualities); its religious, philosophical<br />

<strong>and</strong> mythological implications (<strong>the</strong> son±fa<strong>the</strong>r/man±God relationship <strong>and</strong><br />

its breakdown <strong>and</strong> representation of this relationship in world mythology<br />

<strong>and</strong> religions); <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> cinematic <strong>and</strong> ®ctional freaks that had impressed<br />

<strong>Burton</strong> in his youth (Boris Karloff as <strong>the</strong> Frankenstein monster, King<br />

Kong, Godzilla, etc.).<br />

Chapter 3 is about <strong>Tim</strong> <strong>Burton</strong>'s `superheroes'. <strong>The</strong> superhero part of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Burton</strong>ian male character, quite predictably, wants to free <strong>the</strong> world from<br />

evil. His twofold inner/outer ®ght with what he perceives as evil in his<br />

culture <strong>and</strong> his own psyche is a crucial part of his quest for psychological<br />

unity. Since Batman Returns (1992) <strong>the</strong> individuation of <strong>the</strong> male character<br />

in <strong>Burton</strong>'s ®lms became enhanced by encounters with charismatic (but<br />

menacing) anima ®gures ± Corpse Bride, Catwoman <strong>and</strong> Jenny/<strong>the</strong> witch in<br />

Big Fish. <strong>The</strong> hero's adventures will be analysed using <strong>the</strong> spiritual quest,<br />

doppelgaÈnger, anima <strong>and</strong> fa<strong>the</strong>r/God motifs. I will also discuss <strong>Burton</strong>'s<br />

infantile superheroes ± <strong>the</strong> Stainboy <strong>and</strong> Paul Reubens's original creation,<br />

Pee Wee from Pee Wee's Big Adventure (1985).<br />

Chapter 4 mainly concerns <strong>the</strong> `genius' guise of <strong>Burton</strong>'s male characters<br />

(Vincent, Victor from Frankenweenie, Ed Wood <strong>and</strong> Willie Wonka).<br />

<strong>Burton</strong>'s freaks grow up to become raw talents. As a rule, <strong>the</strong>ir creativity<br />

expresses itself in ra<strong>the</strong>r ambitious Frankensteinesque activities such as, for<br />

instance, monster-making. Vincent Malloy dreams of creating `a terrible<br />

zombie' out of his dog Abercrombie; little Victor from Frankenweenie<br />

realises this dream ± he actually revives his dog Sparky, who had been hit<br />

by a car, <strong>and</strong> turns him into a little `doggy' version of <strong>the</strong> Frankenstein<br />

monster; Ed Wood, a mad Hollywood director, makes painfully bad horror<br />

movies; <strong>and</strong> Willy Wonka, <strong>the</strong> virtuoso chocolatier, possesses a collection of<br />

weird wax dolls <strong>and</strong> produces monstrosities out of various edible substances.<br />

`<strong>The</strong> dark child' of <strong>Burton</strong> is invariably gifted, lonely, <strong>and</strong> perceived<br />

http://www.jungarena.com/tim-burton-<strong>the</strong>-monster-<strong>and</strong>-<strong>the</strong>-crowd-9780415489713

Introduction 3<br />

as insane by <strong>the</strong> hyperbolically `normal' people surrounding him. Following<br />

<strong>the</strong> footpath of <strong>the</strong> traditional Frankenstein narrative, <strong>Burton</strong> puts a lot of<br />

emphasis on <strong>the</strong> unique abilities of <strong>the</strong> creator, his overwhelming ambition,<br />

his difference from <strong>the</strong> crowd, <strong>and</strong> his strong association with <strong>the</strong> hideous<br />

freak to whom he gives life.<br />

<strong>The</strong> demonic side of <strong>Burton</strong>'s freaks is examined in Chapter 5 (`<strong>The</strong><br />

Maniac'). It picks up where <strong>the</strong> previous chapter left off, <strong>and</strong> focuses on <strong>the</strong><br />

anti-hero, <strong>the</strong> doppelgaÈnger (or <strong>the</strong> shadow, to use <strong>Jungian</strong> terminology). In<br />

<strong>Burton</strong>'s ®lms it usually manifests itself in <strong>the</strong> villainous (`Mr Hyde') side of<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Burton</strong>ian hero ± <strong>the</strong> dangerous psychopath. <strong>The</strong>se characters illustrate<br />

<strong>the</strong> evil, unstable, perverted, totally asocial <strong>and</strong> antisocial side of `<strong>the</strong><br />

genius'. <strong>The</strong> chapter will incorporate <strong>Burton</strong>'s ®rst commercially successful<br />

features, Beetlejuice, Sweeney Todd: <strong>The</strong> Demon Barber of Fleet Street,<br />

Batman <strong>and</strong> Batman Returns.<br />

<strong>Burton</strong>'s two famous tricksters, Michael Keaton's Betelgeuse <strong>and</strong> Jack<br />

Nicholson's Joker, could have been discussed ei<strong>the</strong>r under <strong>the</strong> `monster' or<br />

`<strong>the</strong> maniac' title, but I have chosen to put <strong>the</strong>m in <strong>the</strong> latter category<br />

because of <strong>the</strong> aggressive nature of <strong>the</strong>se characters. Betelgeuse is a<br />

trickster-like creature who oozes danger; he is rough, mad, evil <strong>and</strong> uncontrollable.<br />

Nicholson's Joker is even darker than Keaton's Betelgeuse, <strong>and</strong><br />

uses his sinister creativity to torture <strong>and</strong> murder people.<br />

Chapter 6 is devoted to <strong>the</strong> much-criticised Mars Attacks! <strong>and</strong> Planet of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Apes. <strong>The</strong>se ®lms are exceptions from <strong>Burton</strong>'s `<strong>the</strong> monster <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

crowd' routine. <strong>The</strong>y are not about <strong>the</strong> usual outcast's struggle for acceptance<br />

by society, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y are not built around <strong>the</strong> main character's internal<br />

®ght with <strong>the</strong> personal doppelgaÈnger. Instead, in <strong>the</strong>se ®lms <strong>Burton</strong><br />

attempts to go fur<strong>the</strong>r in his investigations of <strong>the</strong> con¯ict between individualism<br />

<strong>and</strong> collectivity, <strong>and</strong> focuses on society itself, on its dark, authoritarian<br />

<strong>and</strong> inhuman aspects. In Mars Attacks! <strong>and</strong> Planet of <strong>the</strong> Apes, <strong>the</strong><br />

collective shadow takes <strong>the</strong> form of an outside invader (Martians or<br />

humanoid apes) <strong>and</strong> attempts to eliminate <strong>the</strong> human race. In this chapter I<br />

will try to explain why <strong>Burton</strong>'s attempts to make ®lms about <strong>the</strong> personal<br />

shadow usually earn critical acclaim <strong>and</strong> have great commercial success,<br />

while his renditions of <strong>the</strong> collective shadow are seen as `over <strong>the</strong> top' <strong>and</strong><br />

super®cial.<br />

Of course, I could have organised <strong>the</strong> book diachronically ra<strong>the</strong>r than<br />

synchronically, i.e. examined <strong>Burton</strong>'s ®lms in chronological order. This<br />

would have given me <strong>the</strong> opportunity to study his `technical' progress as a<br />

®lm director, as well as examine <strong>the</strong> development of <strong>the</strong>mes <strong>and</strong> motifs in<br />

his ®lms. This is how it has been done by most of my predecessors 1 : Mark<br />

1 Except Alison McMahan, author of <strong>The</strong> Films of <strong>Tim</strong> <strong>Burton</strong> (2005), who discusses <strong>Burton</strong>'s<br />

works in terms of genre <strong>and</strong> stylistic features.<br />

http://www.jungarena.com/tim-burton-<strong>the</strong>-monster-<strong>and</strong>-<strong>the</strong>-crowd-9780415489713

4 Introduction<br />

Salisbury (<strong>Burton</strong> on <strong>Burton</strong>, 1995; 2000; 2006); Le Blanc <strong>and</strong> Odell (<strong>Tim</strong><br />

<strong>Burton</strong>, pocket essential series, 2005); Jim Smith <strong>and</strong> Clive Mat<strong>the</strong>ws (<strong>Tim</strong><br />

<strong>Burton</strong>, 2007); <strong>and</strong> Edwin Page (Gothic Fantasy: <strong>the</strong> Films of <strong>Tim</strong> <strong>Burton</strong>,<br />

2007). However, my opinion is that in <strong>Burton</strong>'s case, <strong>the</strong> classic careeroverview<br />

approach is not very effective ± simply because his style, methods<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>mes do not change signi®cantly throughout his directorial career.<br />

My choice of <strong>the</strong> synchronic layout is based on <strong>the</strong> assumption that <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>matic range of <strong>Burton</strong>'s ®lms is more interesting to examine than his<br />

evolution as a director. <strong>Jungian</strong> psychology, with its propensity towards<br />

syntagmatic analysis of myths <strong>and</strong> a certain lack of respect for paradigmatic<br />

systematisation, is always h<strong>and</strong>y for <strong>the</strong> investigation of <strong>the</strong>matic<br />

ranges.<br />

Besides, I still use diachrony ± but of a different kind. <strong>Burton</strong>'s ®lms<br />

traditionally deal with cultural <strong>and</strong> psychological issues pertaining to<br />

modern Western societies, from <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> eighteenth century to <strong>the</strong><br />

present day. While <strong>the</strong> synchronic approach breaks <strong>the</strong> unity of <strong>Burton</strong>'s<br />

oeuvre, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> continuity of his protagonist, into many fragments (<strong>the</strong><br />

different faces of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burton</strong>ian child), I can never<strong>the</strong>less pull <strong>the</strong> fragments<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r by putting <strong>the</strong>m onto <strong>the</strong> diachronic scale of modernity, thus<br />

establishing a new kind of continuity. This new diachrony reveals <strong>the</strong> face<br />

of <strong>the</strong> modern man as <strong>Burton</strong> usually depicts him ± broken into pieces,<br />

<strong>the</strong>n sewn toge<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>and</strong> struggling to ®nd a stable centre within himself ±<br />

<strong>the</strong> centre which would help him not to fall apart again.<br />

<strong>The</strong> question of style<br />

<strong>Tim</strong> <strong>Burton</strong> has a singular vision, now confused with highbrow directing,<br />

now with mainstream commercialism ± <strong>and</strong> yet he steadily remains in a<br />

league of his own. He is certainly not your typical `artistic' ®lmmaker; he is<br />

not a `camera <strong>and</strong> montage' person, breaking down, storyboarding each<br />

shot down to <strong>the</strong> ®nest detail, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n torturing his team <strong>and</strong> actors in an<br />

existential attempt to recreate his unique but ephemeral vision. Unlike for<br />

Hitchcock, who famously used to storyboard every shot in his ®lms, or<br />

Spielberg, whose narratives are so very neat <strong>and</strong> smooth, narrative perfection<br />

would be completely out of place in <strong>Burton</strong>'s works. In a <strong>Tim</strong><br />

<strong>Burton</strong> ®lm you will not ®nd a long take choreographed with surgical<br />

precision, nor encounter an iconographic horse or a marble lion suddenly<br />

squeezed in between two o<strong>the</strong>r shots ± so as to invoke complex references<br />

or highlight a higher idea. Nei<strong>the</strong>r will you stumble upon an elegant conceptual<br />

dissociation between <strong>the</strong> different cinematic codes <strong>and</strong> sub-codes<br />

(for instance, a ®rst-person camera moving about in an empty ¯at while <strong>the</strong><br />

invisible intradiegetic voice on <strong>the</strong> phone is having a seemingly banal<br />

conversation with his mo<strong>the</strong>r) in order to emphasise <strong>the</strong> deceptiveness <strong>and</strong><br />

transience of reality: <strong>the</strong> irreparable gap between <strong>the</strong> `inner' <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> `outer'.<br />

http://www.jungarena.com/tim-burton-<strong>the</strong>-monster-<strong>and</strong>-<strong>the</strong>-crowd-9780415489713

Introduction 5<br />

No, <strong>Burton</strong> does not aim at this level of <strong>the</strong>oretical <strong>and</strong> conceptual complexity,<br />

<strong>and</strong> does not combine <strong>the</strong> cinematic means of expression in<br />

unexpected, groundbreaking ways, to achieve it.<br />

And this is, perhaps, for <strong>the</strong> best. In fact, experimental tracking shots,<br />

lions, horses, clever camera angles <strong>and</strong> avant-garde points of view would<br />

not be suitable for his creative purposes. Growing up inspired by <strong>the</strong> style<br />

of Dr Seuss (`<strong>the</strong> rhythm of his stuff spoke to me very clearly', Salisbury,<br />

2006: 19), avidly watching Ray Harryhausen's work <strong>and</strong> devouring horror<br />

B-movies from around <strong>the</strong> world, <strong>Tim</strong> <strong>Burton</strong> developed a unique personal<br />

style whose essence can be described as `gr<strong>and</strong> effect by simple means' (of<br />

course, one can also call it popular). He remains ®rmly democratic in his<br />

use <strong>and</strong> combination of cinematic devices. In many of his ®lms he tells a<br />

fairly simple story, which, thanks to its straightforward sequentiality <strong>and</strong><br />

uncluttered symbolism, is immediately accessible for <strong>the</strong> spectator regardless<br />

of his or her age or background. A <strong>Burton</strong> story is traditionally illustrated<br />

with beautiful pictures which are far more eloquent than any words<br />

can be. Films like Edward Scissorh<strong>and</strong>s or Charlie <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chocolate Factory<br />

have at <strong>the</strong>ir core <strong>the</strong> childlike naivety, pain <strong>and</strong> anger aimed at <strong>the</strong><br />

insensitive crowd of adults who have long ceased to see <strong>the</strong> world in fresh<br />

colours. Despite being clear, his message is emotionally deep. To render <strong>the</strong><br />

suffering <strong>and</strong> confusion of his immature protagonists, <strong>Burton</strong> cannot use<br />

<strong>the</strong> elaborate sequential <strong>and</strong> combinatorial devices that are traditionally<br />

employed to show <strong>the</strong> complexity, multiplicity <strong>and</strong> unpredictability of <strong>the</strong><br />

adult world ± intricate montage, `philosophical' long takes with a series of<br />

complex compositions, freeze frames, rhythmic punctuation, logical discrepancies<br />

between picture <strong>and</strong> sound, clashes between <strong>the</strong> extradiegetic<br />

<strong>and</strong> intradiegetic planes, etc. Any `grown-up' instruments would only<br />

obscure <strong>the</strong> message, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> purity of youthful vision would be lost.<br />

Instead, <strong>Burton</strong> chooses to create an impact using different methods. At<br />

stake are not sequential editing or <strong>the</strong> position <strong>and</strong> movement of <strong>the</strong> camera<br />

but <strong>the</strong> quality <strong>and</strong> detailedness of <strong>the</strong> picture <strong>and</strong> its emotional correlation<br />

with music. In this sense, he is far less `cinematic' than many directors.<br />

<strong>Burton</strong> is more of a `mise-en-sceÁne director' who has always been praised for<br />

his extraordinary visual sense. His gr<strong>and</strong> imagery seems to be slapped onto<br />

narrative canvases like blobs of dark matter, like some unexplainable <strong>and</strong><br />

invincible forces, which effectively belittle both protagonists <strong>and</strong><br />

antagonists. <strong>Burton</strong>'s marvellous, powerful visuals are not organised into<br />

perfect arrangements. How <strong>the</strong> shots work as a sequence (ei<strong>the</strong>r `classic' or<br />

`avant-garde') has never been of much importance in his ®lms. In cinesemiotic<br />

terms, he is not as interested in <strong>the</strong> higher structural (syntagmatic)<br />

level as, for instance, such an extreme `syntagmatic' director as Alfred<br />

Hitchcock. Most of <strong>Burton</strong>'s directorial effort is put into single frames<br />

(morphemes); shots at most (words) ± but not `cleverly constructed'<br />

sequences (sentences, paragraphs, chapters). Experimental montage <strong>and</strong><br />

http://www.jungarena.com/tim-burton-<strong>the</strong>-monster-<strong>and</strong>-<strong>the</strong>-crowd-9780415489713

6 Introduction<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r forms of `authoritative' editing (Tarkovsky's `camera montage', for<br />

example) are indicative of a certain desire to control <strong>the</strong> narrative as a<br />

whole, of <strong>the</strong> venture to achieve <strong>the</strong> solidity of <strong>the</strong> text. <strong>Burton</strong>, however,<br />

does not support such authoritarianism. Here is, for instance, his perception<br />

of storyboarding: `I used to [storyboard] but I don't do as much anymore.<br />

In fact, I am getting anti-storyboard. I pretty much stopped on Beetlejuice.<br />

You storyboard things that need effects. I still do it to some degree. But<br />

certainly after <strong>the</strong> ®rst Batman, I really stopped. And now, I can't even come<br />

up with ± I'm getting twisted about <strong>the</strong> whole thing. <strong>The</strong>re is something<br />

about being spontaneous <strong>and</strong> working shots out. [. . .] <strong>The</strong>re's an energy <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>re's a working through things with people' (Fraga, 2005: 82).<br />

As for editing, it is a very melancholy process for <strong>Burton</strong>. One of his<br />

interviewers, David Edelstein, notes: `When I suggest to <strong>Burton</strong> that editing<br />

does not express him <strong>the</strong> way o<strong>the</strong>r parts of <strong>the</strong> process do, he muses that<br />

after a shoot ends, it's like breaking up with someone ± he edits in<br />

depression, which somehow gets incorporated into <strong>the</strong> ®lm' (Fraga, 2005:<br />

33). In ano<strong>the</strong>r interview, conducted by David Breskin, <strong>Burton</strong> admits to<br />

not paying much attention to shot sequences: `When I look at rushes<br />

[unedited footage] I sometimes get chills because it reminds me of shooting.<br />

But editing? What can I tell you? I don't slap <strong>the</strong>m toge<strong>the</strong>r, but I'm not<br />

going to win any editing awards. It's okay. It's ®ne' (Fraga, 2005: 83). He is<br />

not, by his own admission, going to `create some kind of trendy or hot<br />

editing' (Fraga, 2005: 33).<br />

His deliberate emphasis on mise-en-sceÁne, <strong>and</strong> noticeable disregard for<br />

<strong>the</strong> speci®c cinematic codes, won <strong>the</strong> heart of Anton Furst, who was hired<br />

as <strong>the</strong> production designer for Batman (1989). Furst said in an interview<br />

with Alan Jones that he had never felt so naturally in tune with a director ±<br />

`conceptually, spiritually, visually, or artistically' (Fraga, 2005: 22). Such a<br />

unique connection happened because <strong>the</strong> two shared <strong>the</strong> same philosophy<br />

of moviemaking. Both Furst <strong>and</strong> <strong>Burton</strong> are primarily concerned with<br />

creating visual impact, with delivering a powerful image. <strong>The</strong> impact lies<br />

not in camerawork but in <strong>the</strong> basics, in <strong>the</strong> ®rst impression: `When we ®rst<br />

met, we both independently mentioned how sick we were of <strong>the</strong> ILM 2<br />

school of ®lm-making [. . .] We both agreed <strong>the</strong> best special effect we could<br />

ever remember seeing was <strong>the</strong> house in Psycho because it registers such a<br />

strong image. Impact, that's what ®lms are about ± not effects. I felt much<br />

better after that conversation, knowing he was totally uninterested in<br />

camera tricks <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> clever, clever approach' (Fraga, 2005: 22). But <strong>Tim</strong><br />

<strong>Burton</strong> is a `clever, clever' director in <strong>the</strong> sense that he knows how to<br />

capture mass audiences without `cheapening' his ®lms on <strong>the</strong> one h<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong><br />

2 George Lucas's brainchild, Industrial Light <strong>and</strong> Magic ± a motion picture visual effects<br />

company.<br />

http://www.jungarena.com/tim-burton-<strong>the</strong>-monster-<strong>and</strong>-<strong>the</strong>-crowd-9780415489713

how to create highly original works without resorting to mind-blowing<br />

complexity on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

A different kind of auteur<br />

Introduction 7<br />

Despite his lack of ambition to control <strong>the</strong> narrative ± both its textual <strong>and</strong><br />

cinematic constituents ± <strong>Burton</strong> is universally hailed as one of <strong>the</strong> most<br />

important contemporary Hollywood auteurs. Which is, in a way, paradoxical,<br />

because he cannot be fur<strong>the</strong>r from an omniscient intellectual operating<br />

in riddles (like David Lynch) or an ace at complex, tonal montage (aÁ la Jim<br />

Jarmusch).<br />

Before trying to decide whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>Tim</strong> <strong>Burton</strong> deserves <strong>the</strong> nebulous auteur<br />

title, let us remind ourselves what this title implies. La politique des auteurs,<br />

since its emergence in France in <strong>the</strong> late 1940s, <strong>and</strong> throughout its long life<br />

as a half-formulated concept, never managed to become a fully ¯edged<br />

<strong>the</strong>ory. True, compared to Andre Bazin <strong>and</strong> FrancËois Truffaut's applications<br />

of <strong>the</strong> ®lmic authorship idea, Andrew Sarris's translation of it boasted<br />

more shape, but still lacked a quotable de®nition. As Sarris himself<br />

admitted, `<strong>the</strong> auteur <strong>the</strong>ory is not so much a <strong>the</strong>ory as an attitude, a table<br />

of values that converts ®lm history into directorial autobiography' (Sarris,<br />

1968: 30±34). Even so, despite <strong>the</strong> lack of de®nition, <strong>the</strong> term is as popular<br />

as ever <strong>and</strong> its common usage is constantly growing. Any `decent' auteur is<br />

required to possess any (or preferably both) of <strong>the</strong> following features:<br />

1. Control over all or most of <strong>the</strong> processes involved in making<br />

afilm<br />

This is a slightly utopian requirement because of <strong>the</strong> so-called `noise'<br />

(scriptwriter, editor, producer, cameraman, composer, <strong>the</strong> actors). According<br />

to <strong>the</strong> British ®lm <strong>the</strong>orist Peter Wollen, <strong>the</strong> directorial factor is only<br />

one of <strong>the</strong> many different contributions in <strong>the</strong> moviemaking process,<br />

`though perhaps <strong>the</strong> one which carries <strong>the</strong> most weight' (Wollen, 1969±<br />

1972: 104). <strong>The</strong> scriptwriter, for instance, can be very `noisy', for his vision<br />

of <strong>the</strong> ®lm's style, structure <strong>and</strong> meaning can be very different from that of<br />

<strong>the</strong> director. A very possessive auteur, Andrey Tarkovsky argued that <strong>the</strong><br />

®lm author's wholeness of vision should be placed higher than any creative<br />

contributions coming from <strong>the</strong> support team:<br />

When a writer <strong>and</strong> a director have different aes<strong>the</strong>tic starting-points,<br />

compromise is impossible. [. . .] When such con¯ict occurs <strong>the</strong>re is only<br />

one way out: to transform <strong>the</strong> literary scenario into a new fabric, which<br />

at a certain stage in <strong>the</strong> making of <strong>the</strong> ®lm will come to be called <strong>the</strong><br />

shooting script. And in <strong>the</strong> course of work on this script, <strong>the</strong> author of<br />

<strong>the</strong> ®lm (not of <strong>the</strong> script but of <strong>the</strong> ®lm) is entitled to turn <strong>the</strong> literary<br />

http://www.jungarena.com/tim-burton-<strong>the</strong>-monster-<strong>and</strong>-<strong>the</strong>-crowd-9780415489713

8 Introduction<br />

scenario this way or that as he wants. All that matters is that his vision<br />

should be whole, <strong>and</strong> that every word of <strong>the</strong> script should be dear to<br />

him <strong>and</strong> have passed through his own creative experience. For among<br />

<strong>the</strong> piles of written pages, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> actors, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> places chosen for<br />

location, <strong>and</strong> even <strong>the</strong> most brilliant dialogue, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> artist's sketches,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re st<strong>and</strong>s only one person: <strong>the</strong> director, <strong>and</strong> he alone, as <strong>the</strong> last<br />

®lter in <strong>the</strong> creative process of ®lm-making.<br />

(Tarkovsky, 1989: 18)<br />

Undeniably, <strong>the</strong> biggest `noise' of all comes from <strong>the</strong> people in charge of <strong>the</strong><br />

budget (which Tarkovsky, as a young ®lm-school graduate, quickly realised<br />

when his ®lms began to suffer at <strong>the</strong> h<strong>and</strong>s of Soviet censorship). Andrew<br />

Sarris recalls an old Hollywood anecdote which involves <strong>the</strong> studio head<br />

Samuel Goldwyn <strong>and</strong> a reporter. <strong>The</strong> latter `had <strong>the</strong> temerity to begin a<br />

sentence with <strong>the</strong> statement ``. . . when William Wyler made Wu<strong>the</strong>ring<br />

Heights''. <strong>The</strong> reporter never passed beyond <strong>the</strong> premise. ``I made Wu<strong>the</strong>ring<br />

Heights,'' Goldwyn snapped, ``Wyler only directed it''' (Sarris, 1968: 8).<br />

Leaving <strong>the</strong> Hollywood studio system, or indeed any system that controls<br />

<strong>the</strong> ®nancial base of <strong>the</strong> ®lm, seriously narrows <strong>the</strong> gap between `unlimited'<br />

<strong>and</strong> `limited' control over <strong>the</strong> project.<br />

<strong>The</strong> intrinsic complexity of <strong>the</strong> ®lmmaking process, in that it involves<br />

various people at different levels, makes it dif®cult to attain <strong>the</strong> goal of<br />

`absolute control'. Authorship can only be approximate; it can only be<br />

shared ± to a different degree in each individual case, of course ± because<br />

`writers, actors, producers <strong>and</strong> technicians challenge [<strong>the</strong> director] at every<br />

turn' (Sarris, 1968: 12).<br />

2. A distinct `voice' (recurrent <strong>the</strong>mes, motifs, characters,<br />

techniques, stylistic features)<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is no doubt that <strong>Tim</strong> <strong>Burton</strong> has a unique cinematographic style. `A<br />

distinct voice' sounds ambitious, but this is much easier to achieve than <strong>the</strong><br />

`sole authorship' prerequisite. <strong>The</strong> British ®lm scholar Geoffrey Novel-<br />

Smith argued that recognisable motifs are one essential corollary of <strong>the</strong><br />

auteur <strong>the</strong>ory: `<strong>The</strong> pattern formed by <strong>the</strong>se motifs . . . is what gives an<br />

author's work its particular structure, both de®ning it internally <strong>and</strong> distinguishing<br />

one body of work from ano<strong>the</strong>r (Caughie, 1981: 137).<br />

Just like any work of art, a ®lm should be original, recognisable <strong>and</strong> have<br />

an `identi®able' maker's mark `in <strong>the</strong> corner'. Originality, <strong>the</strong> covetable<br />

distinct style, can be fur<strong>the</strong>r subdivided into formal (montage, mise-ensceÁne,<br />

camera angles, punctuation, sequential organisation of <strong>the</strong> narrative,<br />

etc.) <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>matic. Like in a literary text, <strong>the</strong> two, <strong>the</strong> form <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> content,<br />

intertwine <strong>and</strong> support each o<strong>the</strong>r. Quite often, ®lm critics seem to equate<br />

`originality' with formal complexity. Tricks like `hot editing' (<strong>Burton</strong>'s<br />

http://www.jungarena.com/tim-burton-<strong>the</strong>-monster-<strong>and</strong>-<strong>the</strong>-crowd-9780415489713

Introduction 9<br />

term), unusual POV (think of <strong>the</strong> `soup's point of view' from Guy Ritchie's<br />

Lock, Stock <strong>and</strong> Two Smoking Barrels), <strong>and</strong> convoluted narratives (<strong>the</strong><br />

multi-layered, twisted, nightmarish plot in Lynch's Mulholl<strong>and</strong> Drive is a<br />

good example) are traditionally seen as part of <strong>the</strong> auteur culture <strong>and</strong><br />

intellectual moviemaking. Technical virtuosity, stubbornness <strong>and</strong> a certain<br />

inescapable elitism are traditionally associated with <strong>the</strong> concept of directorial<br />

`autership'. Also, <strong>the</strong>re is always a danger that <strong>the</strong> desire to `express<br />

oneself entirely in a ®lm' is interpreted as a sign of egotism <strong>and</strong> vanity, <strong>the</strong><br />

desire to `play God' <strong>and</strong> be <strong>the</strong> centre of attention.<br />

True, it would not be easy to squeeze <strong>Tim</strong> <strong>Burton</strong> into any of <strong>the</strong> auteur<br />

stereotypes. As a director, he is an oxymoron, or, as Le Blanc <strong>and</strong> Odell put<br />

it, `a Hollywood contradiction' (2005: 11). Whatever aspect of his creative<br />

life you examine, <strong>the</strong>re is always a paradox lurking in <strong>the</strong> background.<br />

Consider, for instance, <strong>the</strong> issue of unlimited control over one's work. On<br />

<strong>the</strong> surface of it, <strong>Burton</strong> is ®rmly rooted in <strong>the</strong> studio system. His career<br />

began at Disney, where he found himself after <strong>the</strong> California Institute of <strong>the</strong><br />

Arts, a training school created by Walt Disney in <strong>the</strong> 1960s. Eight of<br />

his ®lms, including Batman, Charlie <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chocolate Factory <strong>and</strong> Sweeney<br />

Todd, were produced by Warner Bro<strong>the</strong>rs; Edward Scissorh<strong>and</strong>s was<br />

®nanced by Twentieth-Century Fox, <strong>and</strong> Big Fish is a Columbia Pictures<br />

production. At <strong>the</strong> same time, he has always had a tempestuous relationship<br />

with <strong>the</strong> studio system, aiming to preserve his unique vision while keeping to<br />

<strong>the</strong> studio's budget. He regularly sounds disdainful when he speaks of his<br />

experience of dealing with <strong>the</strong> studio system, <strong>the</strong> phrase `F**k your system'<br />

being one of <strong>the</strong> most expressive of his opinions (Fraga, 2005: 57).<br />

And from <strong>the</strong> very start <strong>the</strong> fateful `system' intermittently hindered <strong>and</strong><br />

pushed forward <strong>Burton</strong>'s directorial career. He considered himself lucky to<br />

be picked by <strong>the</strong> Disney Review Board out of <strong>the</strong> crowd of ambitious<br />

contenders at Cal Arts, but soon realised that `<strong>the</strong> dream ticket' would only<br />

lead him to a dead-end: `Disney <strong>and</strong> I were a bad mix [. . .] <strong>the</strong>y want you to<br />

be an artist, but at <strong>the</strong> same time <strong>the</strong>y want you to be a zombie factory<br />

worker <strong>and</strong> have no personality. It takes a very special person to make<br />

those two sides of your brain coexist' (Salisbury, 2006: 9±10). He found <strong>the</strong><br />

atmosphere so sti¯ing <strong>and</strong> `anti-auteur' that he eventually left <strong>the</strong> studio in<br />

<strong>the</strong> middle of <strong>the</strong> 1980s after Frankenweenie, his black <strong>and</strong> white short, was<br />

deemed by Disney too `dark' for children's audiences (it was subsequently<br />

shelved until 1992).<br />

<strong>Tim</strong> <strong>Burton</strong>'s instinctive ability to appeal to <strong>the</strong> mass audience can easily<br />

be confused with an acute sense for marketable cinematic products. It is<br />

obvious that <strong>the</strong> studio system, despite its notorious habit of preferring<br />

successful entrepreneurs to creative recluses, has successfully exploited<br />

<strong>Burton</strong>'s Gothic fantasies ± which happen to sell well. Having watched so<br />

many horror ®lms as a child, <strong>and</strong> consequently having absorbed all <strong>the</strong><br />

basic principles of a marketable mass movie ± simpli®ed narrative, big<br />

http://www.jungarena.com/tim-burton-<strong>the</strong>-monster-<strong>and</strong>-<strong>the</strong>-crowd-9780415489713

10 Introduction<br />

drama, emotional symbolism, hyperbolised visuals, high stylisation, rich<br />

arti®ciality of sets, costumes <strong>and</strong> make-up ± <strong>Burton</strong> undoubtedly gained a<br />

sharp sense of `product' that would appeal to a mass audience (something<br />

that is quite unusual in an auteur aspirant). And anyway, <strong>Burton</strong> is known<br />

as a director who is prepared to ®ght for his creative vision. He chose<br />

Johnny Depp over Tom Cruise as Edward Scissorh<strong>and</strong>s at a time when<br />

Depp was no more than a teen `novelty idol' <strong>and</strong> Cruise was already a<br />

con®rmed superstar. Depp was eventually given <strong>the</strong> role ± apparently after<br />

much ®ghting <strong>and</strong> debate on <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> director. <strong>The</strong> actor could not<br />

believe his ears when his agent rang him weeks after <strong>the</strong> initial meeting with<br />

<strong>Burton</strong>: `I put <strong>the</strong> phone down <strong>and</strong> mumbled those words to myself. And<br />

<strong>the</strong>n mumbled <strong>the</strong>m to anyone I came in contact with. I couldn't f**king<br />

believe it. He was willing to risk everything on me in <strong>the</strong> role. Headbutting<br />

<strong>the</strong> studio's wishes, hopes <strong>and</strong> dreams for a big star with established boxof®ce<br />

draw, he chose me' (Salisbury, 2006: xi). <strong>Burton</strong>'s side of <strong>the</strong> story<br />

looked like this:<br />

<strong>The</strong>y are always saying, here is a list of ®ve people who are box-of®ce,<br />

<strong>and</strong> three of <strong>the</strong>m are Tom Cruise. I've learned to be open at <strong>the</strong> initial<br />

stage <strong>and</strong> talk to people. He certainly wasn't my ideal, but I talked to<br />

him. He was interesting, but I think it worked out for <strong>the</strong> best. A lot of<br />

questions came up ± I don't really recall <strong>the</strong> speci®cs ± but at <strong>the</strong> end<br />

of <strong>the</strong> meeting I did feel like, <strong>and</strong> even probably said to him, `It's nice<br />

to have a lot of questions about <strong>the</strong> character, but you ei<strong>the</strong>r do it or<br />

you don't do it'<br />

(Salisbury, 2000: 91)<br />

<strong>Burton</strong> feels justi®ed in arguing with studio executives over `details' like <strong>the</strong><br />

choice of actors <strong>and</strong> ®lm endings ± but not like some touchy, capricious<br />

auteur with a systematic vision aÁ la Adam Kesher in Mulholl<strong>and</strong> Drive.<br />

<strong>Burton</strong>, in his elated stubbornness, resembles a child prophet who believes<br />

that he has seen an apparition of <strong>the</strong> Virgin Mary, <strong>and</strong> is now adamant that<br />

<strong>the</strong> visitation was absolutely genuine. `If Beetlejuice turns out to be<br />

successful,' he said in one of his early interviews, `I will be so happy, <strong>and</strong> so<br />

perversely happy. I'm for anything that subverts what <strong>the</strong> studio thinks you<br />

have to do' (Fraga, 2005: 15).<br />

This amazing obstinacy, <strong>the</strong> force that bends even <strong>the</strong> pillars of <strong>the</strong> studio<br />

system, made <strong>the</strong> ®lm critic Jonathan Romney label him as `Hollywood's<br />

pet maladjusted adolescent' (Woods, 2002: 170). <strong>The</strong> `adolescent', however,<br />

knows how to deal with those sensible, reasonable adults:<br />

. . . <strong>the</strong>y don't know what you go through with studio people <strong>and</strong><br />

executives, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y take <strong>the</strong>ir cue a lot from critics, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> feeling is<br />

http://www.jungarena.com/tim-burton-<strong>the</strong>-monster-<strong>and</strong>-<strong>the</strong>-crowd-9780415489713

Introduction 11<br />

that `<strong>Tim</strong> can't tell a story out of a paper bag'. [. . .] And every time,<br />

when <strong>the</strong>y're developing a script <strong>and</strong> you're talking to <strong>the</strong> studio <strong>and</strong><br />

you have <strong>the</strong>se stupid meetings with <strong>the</strong>m, I can say that if <strong>the</strong>re is a<br />

problem with <strong>the</strong> movie it is nothing that you discussed. [. . .] And<br />

Beetlejuice was kind of <strong>the</strong> one movie that gave me, again, that feeling<br />

of humanity, that F**k Everybody! That made me feel very good, that<br />

<strong>the</strong> audience didn't need a certain kind of thing. Movies can be<br />

different things! Wouldn't it be great if <strong>the</strong> world allowed David<br />

Cronenberg to do his thing <strong>and</strong> people could tell <strong>the</strong> difference! And<br />

criticism would be on <strong>the</strong> whole o<strong>the</strong>r level! And <strong>the</strong> world be on <strong>the</strong><br />

whole o<strong>the</strong>r level!<br />

(Fraga, 2005: 57)<br />

`<strong>The</strong> difference', one might assume, lies in <strong>the</strong> amount of `noise' that<br />

gradually creeps into <strong>the</strong> ®lm in <strong>the</strong> process of its evolution from <strong>the</strong> initial<br />

concept to <strong>the</strong> ®nal product. All <strong>the</strong> while, <strong>and</strong> ra<strong>the</strong>r contrastingly, <strong>Burton</strong><br />

has respect for <strong>the</strong> people who h<strong>and</strong> out <strong>the</strong> cash, <strong>and</strong> willingly acknowledges<br />

<strong>the</strong> ®nancial responsibility for his creations: `I've never taken <strong>the</strong><br />

attitude of <strong>the</strong> artiste, who says I don't care about anything, I'm just<br />

making my movie. I try to be true to myself <strong>and</strong> do only what I can do,<br />

because if I veer from that everybody's in trouble. And when <strong>the</strong>re is a large<br />

amount of money involved, I attempt, without pretending to know what<br />

audiences are all about, to try <strong>and</strong> do something that people would like to<br />

see, without going too crazy' (Woods, 2002: 51). <strong>Tim</strong> <strong>Burton</strong> is not a purist;<br />

he had always had an eye on <strong>the</strong> commercial side of <strong>the</strong> movie business. In<br />

some of his interviews he expressed ra<strong>the</strong>r anti-auteurish opinions: `I care<br />

about money, which is why I get so intense when <strong>the</strong>se people are on my<br />

case saying I don't make commercial movies, because I've always felt very<br />

responsible to <strong>the</strong> people who put up <strong>the</strong> money. It's not like you're doing a<br />

painting. <strong>The</strong>re is a large amount of money involved, even if you're doing a<br />

low-budget movie, so I don't want to waste it (Salisbury, 2006: 51). It is his<br />

attempt to achieve <strong>the</strong> `golden middle', <strong>the</strong> ideal position in <strong>the</strong> triangle<br />

consisting of <strong>the</strong> director, <strong>the</strong> studio <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> audience, that makes him<br />

simultaneously accessible <strong>and</strong>, surprisingly, sophisticated.<br />

<strong>Burton</strong>'s visual style is extremely recognisable despite <strong>the</strong> fact that he does<br />

not harbour ambitions to produce avant-garde works <strong>and</strong> `explore new<br />

artistic territories'. Most of his creative efforts seem to be aimed at <strong>the</strong><br />

elements that are not exclusive to cinema, or, to use Christian Metz's term,<br />

at `non-speci®c cinematic codes' (for instance, soundtrack <strong>and</strong> codes of<br />

visual iconicity shared with painting) (Metz, 1974: 224±235). <strong>Burton</strong> is at his<br />

most con®dent with <strong>the</strong> components that traditionally determine `<strong>the</strong> main<br />

impression', or <strong>the</strong> general atmosphere of a ®lm: visual-iconic elements,<br />

lighting, music <strong>and</strong> story (but not plot). At <strong>the</strong> same time, he does not<br />

worship speci®cally cinematic properties such as sequentiality, movement of<br />

http://www.jungarena.com/tim-burton-<strong>the</strong>-monster-<strong>and</strong>-<strong>the</strong>-crowd-9780415489713

12 Introduction<br />

<strong>the</strong> image (camera) <strong>and</strong> movement in <strong>the</strong> image (actors). 3 <strong>The</strong> fact that<br />

<strong>the</strong> `picture' moves is an additional bene®t ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> main property<br />

of <strong>Burton</strong>'s creative product ± <strong>the</strong> movement allows him to tell a story,<br />

without foregrounding itself as a stylistic element. Much of his effort goes<br />

into <strong>the</strong> initial impression from <strong>the</strong> shot, hence <strong>the</strong> heightened attention<br />

to <strong>the</strong> static elements of <strong>the</strong> mise-en-sceÁne (<strong>the</strong> ones which cinema shares<br />

with photography): setting, decorations, texture, colours, lighting, framing,<br />

make-up <strong>and</strong> costumes. <strong>The</strong>y make <strong>Burton</strong>'s works highly atmospheric. His<br />

relative neglect of camera movement <strong>and</strong> editing gives his ®lms a charming<br />

imprecision ± which is perfect for <strong>Burton</strong>'s artistic purposes as this kind of<br />

background emphasises <strong>the</strong> magni®cent, luminous symbolism of his ®lms.<br />

<strong>Burton</strong>'s status in Hollywood is so ambiguous that some critics have<br />

altoge<strong>the</strong>r grouped his works with contemporary action movies, confusing<br />

his lack of narrative <strong>and</strong> stylistic precision with an interest in <strong>the</strong> action<br />

aspect of <strong>the</strong> ®lm. Alison McMahan, in a book entitled <strong>The</strong> Films of <strong>Tim</strong><br />

<strong>Burton</strong>, coins <strong>the</strong> term pataphysical ®lm, <strong>and</strong> irrevocably attributes <strong>Burton</strong>'s<br />

style to this genre. In her view, all pataphysical ®lms have in common <strong>the</strong><br />

following features:<br />

· An alternative narrative logic<br />

· Use of special effects in a blatant way<br />

· Thin plots <strong>and</strong> thinly drawn characters, `because <strong>the</strong> narrative relies<br />

more on intertextual, nondiegetic references'.<br />

(McMahan, 2005: 3)<br />

Examples of such movies include, for instance, Van Helsing (2004) <strong>and</strong><br />

Hulk (2003). It appears that <strong>the</strong> movies labelled pataphysical by Alison<br />

McMahan are predominantly commercial. <strong>The</strong>y privilege action over<br />

narrative <strong>and</strong> quite blatantly serve as a recycling factory for anything<br />

previously done in cinema, both stylistically <strong>and</strong> textually, mixing high <strong>and</strong><br />

low, old <strong>and</strong> new; r<strong>and</strong>omly combining genres, plots <strong>and</strong> recycled famous<br />

sequences from o<strong>the</strong>r ®lms. For instance, <strong>the</strong> seven-minute sequence at <strong>the</strong><br />

beginning of Van Helsing, incorporating segments from over 70 years of<br />

Draculas <strong>and</strong> Frankensteins, is not just an ironic statement, a reference that<br />

`got out of control'. It is ± decidedly ± an integral part of <strong>the</strong> movie.<br />

McMahan places <strong>the</strong> roots of this genre in <strong>the</strong> days of early cinema <strong>and</strong><br />

animation, Jules Levy's Les Art IncoheÂrents, <strong>and</strong> in <strong>the</strong> visual <strong>and</strong><br />

ideological legacy of Surrealism. She argues that <strong>the</strong> eccentric works of <strong>the</strong><br />

®rst animator, <strong>the</strong> French science teacher Emile Reynaud, 4 with <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

¯uidity of transformations, in¯uenced contemporary pataphysical ®lms.<br />

3 <strong>The</strong> last two are Metz's terms (Metz, 1974: 232).<br />

4 <strong>The</strong> director of Fantasmagorie (1908), <strong>The</strong> Hasher's Delirium (1910), etc.<br />

http://www.jungarena.com/tim-burton-<strong>the</strong>-monster-<strong>and</strong>-<strong>the</strong>-crowd-9780415489713

Introduction 13<br />

<strong>The</strong> inherited traits include, in McMahan's view, dependence on `excessive'<br />

special effects (which bring with <strong>the</strong>m `a change in narration <strong>and</strong> a ¯attening<br />

of <strong>the</strong> emotional aspects of <strong>the</strong> characters'), non-realistic narrative, <strong>and</strong><br />

tongue-in-cheek attitude (McMahan, 2005: 15). She also insists that <strong>the</strong>se<br />

®lms are not meaningless; ra<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong>y `have come to mean differently, to<br />

mean in new ways' (2005: 3). Unfortunately, <strong>the</strong> author does not explain<br />

what <strong>the</strong>se news ways of meaning are, or what exactly constitutes `<strong>the</strong><br />

alternative narrative logic' which <strong>the</strong> `pataphysical ®lms' appear to follow.<br />

Films like Hulk, Van Helsing, Bro<strong>the</strong>rs Grimm <strong>and</strong> <strong>The</strong> Matrix are<br />

blatantly lowbrow, populist <strong>and</strong> allusive to <strong>the</strong> point of non-stop recycling.<br />

Being fast-paced <strong>and</strong> powerfully visual, <strong>the</strong>y are openly aimed at <strong>the</strong><br />

spectator with a short attention span. <strong>The</strong>ir creators deliberately macerate,<br />

mix <strong>and</strong> match o<strong>the</strong>r ®lms <strong>and</strong> cinematic traditions in order to make <strong>the</strong><br />

product more digestible <strong>and</strong> super®cially attractive. People who make <strong>the</strong>m<br />

know that <strong>the</strong>y are producing a nakedly commercial product.<br />

McMahan's belief that <strong>Burton</strong>'s oeuvre belongs to <strong>the</strong> bulk of <strong>the</strong> `pataphysical<br />

style' is underst<strong>and</strong>able. His ®lms contain some formal attributes<br />

of <strong>the</strong> aforementioned group, such as schematic plots <strong>and</strong> characters,<br />

inter®lmic references <strong>and</strong> allusions, as well as `in your face' special effects<br />

(of which <strong>the</strong> freakish, DIY effects from Beetlejuice are a good example).<br />

<strong>Burton</strong>, a self-confessed fan of classic horror movies, is especially reliant on<br />

allusions: `Because I never read, my fairy tales were probably those monster<br />

movies. [. . .] I mean, fairy tales are extremely violent <strong>and</strong> extremely symbolic<br />

<strong>and</strong> disturbing, probably even more so than Frankenstein <strong>and</strong> stuff<br />

like that, which are kind of mythic <strong>and</strong> perceived as fairy-tale like'<br />

(Salisbury, 2000: 3). True, Frankenstein, in James Whale's realisation, was<br />

an important source of inspiration for <strong>Burton</strong>. Frankenweenie (1984) is<br />

bursting with direct references to both Frankenstein (1931) <strong>and</strong> <strong>The</strong> Bride of<br />

Frankenstein (1935), almost to <strong>the</strong> point of direct translation of Whale's<br />

vision into <strong>the</strong> children's pet story, in which Boris Karloff is replaced with a<br />

little monster dog, who dies but gets `resurrected' by a boy genius. Some<br />

®lmic allusions that <strong>Burton</strong> inserts into his ®lms are smaller <strong>and</strong> less<br />

obvious. For instance, <strong>the</strong> slowly melting dolls' heads in Charlie <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Chocolate Factory (2005) is a tribute to Andre de Toth's <strong>The</strong> House of Wax<br />

(1953) with Vincent Price.<br />

<strong>The</strong> misunderstood introverted punk Edward Scissorh<strong>and</strong>s is an original<br />

creation ± unlike many of his o<strong>the</strong>r powerful motifs <strong>and</strong> characters. In fact,<br />

it appears that only <strong>the</strong> characters who directly re¯ect <strong>Burton</strong>'s own<br />

psychology ± like Vincent <strong>and</strong> Edward ± are entirely original. <strong>The</strong> rest are<br />

borrowed from a variety of literary <strong>and</strong> cinematic sources <strong>and</strong> can be traced<br />

to <strong>the</strong>ir roots in popular culture <strong>and</strong> literature. <strong>The</strong> popular borrowings<br />

include, for instance, <strong>the</strong> superhero Batman, <strong>the</strong> brainy green Martians<br />

from Mars Attacks!, <strong>the</strong> demon barber Sweeney Todd, who made his debut<br />

in 1846 in <strong>the</strong> penny dreadful series entitled <strong>The</strong> String of Pearls: A<br />

http://www.jungarena.com/tim-burton-<strong>the</strong>-monster-<strong>and</strong>-<strong>the</strong>-crowd-9780415489713

14 Introduction<br />

Romance, <strong>and</strong> Ed Wood's circus of freaks <strong>and</strong> ghouls, including Bela<br />

Lugosi <strong>and</strong> Vampyra. <strong>Burton</strong>'s (undeniably mediated) literary in¯uences,<br />

are, too, many <strong>and</strong> diverse: Mary Shelley's Frankenstein <strong>and</strong> its numerous<br />

cinematic reworkings; Washington Irving's <strong>The</strong> Legend of Sleepy Hollow;<br />

Daniel Wallace's Big Fish: A Novel of Mythic Proportions; Roald Dahl's<br />

Charlie <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chocolate Factory; Pierre Boulle's Planet of <strong>the</strong> Apes; <strong>and</strong><br />

Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

Knowing that <strong>Tim</strong> <strong>Burton</strong> likes to reuse aspects of old ®lms, can we<br />

really tell <strong>the</strong> difference between `pataphysical' references <strong>and</strong> `important'<br />

references? Or, in o<strong>the</strong>r words, can one employ heaps of popular allusions<br />

in a meaningful manner?<br />

Action, symbol, introspection<br />

My argument is that associating <strong>Burton</strong>'s works with commercial, fastpaced,<br />

action-packed ®lms steeped with music-clip-like montage <strong>and</strong><br />

r<strong>and</strong>om narrative citations, would be a mistake. <strong>The</strong> `pop' nature of<br />

<strong>Burton</strong>'s ®lms is more of a lucky by-product of his creativity than an<br />

intended outcome. First of all, he is not an action director ± both objectively<br />

<strong>and</strong> self-confessedly ± <strong>and</strong> hence cannot be compared to Stephen<br />

Sommers, Rol<strong>and</strong> Emmerich, James Cameron or <strong>the</strong> Wachowski bro<strong>the</strong>rs.<br />

His action sequences in Batman <strong>and</strong> Planet of <strong>the</strong> Apes are limp, clumsy <strong>and</strong><br />

lacking in agility. `I've seen better action in my day' is <strong>Burton</strong>'s view of his<br />

own action-making skills (Fraga, 2005: 78). Ever <strong>the</strong> true nonconformist, he<br />

declares: `If you want it to be a James Cameron movie <strong>the</strong>n get James<br />

Cameron to do it. Me directing action is a joke; I don't like guns. I hear a<br />

gunshot <strong>and</strong> I close my eyes' (Salisbury, 2006: 114).<br />

Still, it would be unfair to expect a perfect h<strong>and</strong>ling of fast sequences<br />

from a predominantly introspective director. <strong>The</strong> action <strong>Burton</strong> is trying to<br />

express is more of a psychological than a `real' phenomenon. Even on <strong>the</strong><br />

visual level, <strong>the</strong> `quest' motif in his ®lms, along with its principal battles <strong>and</strong><br />

challenges, lacks <strong>the</strong> `physicality', brutality <strong>and</strong> (pseudo)realism of traditional<br />

action movies. It is <strong>the</strong> `inner', not <strong>the</strong> `outer' movement that <strong>Burton</strong><br />

is trying to convey. Unlike <strong>the</strong> `pataphysical' ®lms Alison McMahan<br />

recalls, <strong>Burton</strong>'s works are deemed to be slower, inward-looking <strong>and</strong> far<br />

more personal. All <strong>the</strong> pop-cinematic allusions he ga<strong>the</strong>rs in his ®lms ± be it<br />

<strong>the</strong> ragged Frankenstein monster, Ed Wood's aluminium tin ¯ying saucers<br />

or even <strong>the</strong> melting heads of wax dolls ± are linked, via different modes of<br />

projection, to <strong>the</strong> childhood feelings of dejection, failure to communicate,<br />

<strong>and</strong> alienation from one's surroundings. <strong>The</strong> monstrous, <strong>the</strong> Gothic <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

surreal are not, for <strong>Burton</strong>, simply effective, tried-<strong>and</strong>-tested vehicles for<br />

producing an entertaining narrative. <strong>The</strong>y are far more than communication<br />

aids <strong>and</strong> adequate means of expression. <strong>Burton</strong> may be groping for<br />

http://www.jungarena.com/tim-burton-<strong>the</strong>-monster-<strong>and</strong>-<strong>the</strong>-crowd-9780415489713

Introduction 15<br />

words in interviews, but his visual creations, his Gothic symbols, possess<br />

remarkable depth, clarity <strong>and</strong> precision.<br />

In interviews he also admits to having trouble creating a coherent<br />

cinematic narrative. He explains why he persistently `sacri®ces' <strong>the</strong> narrative<br />

for <strong>the</strong> sake of <strong>the</strong> visuals. Lack of delineation, de®nition <strong>and</strong> linguistic<br />

detailedness is <strong>Burton</strong>'s way of ensuring that his ®lms remain democratic<br />

<strong>and</strong> accessible:<br />

I guess it must be <strong>the</strong> way my brain works, because <strong>the</strong> ®rst Batman<br />

was probably my most concentrated effort to tell a linear story, <strong>and</strong> I<br />

realise that it's like a joke. [. . .] In any of my movies <strong>the</strong> narrative is <strong>the</strong><br />

worst thing you've ever seen, <strong>and</strong> that's constant. [. . .] Do Fellini<br />

movies have a strong narrative drive? I love movies where I make up<br />

my own idea about <strong>the</strong>m. [. . .] Everybody is different, so things are<br />

going to affect people differently. So why not have your own opinions,<br />

have different levels of things you can ®nd if you want <strong>the</strong>m, however<br />

deeply you want to go. That's why I like Roman Polanski's movies, like<br />

<strong>The</strong> Tenant. I've felt like that, I've lived it, I know what that's like. Or<br />

Repulsion, I know that feeling, I underst<strong>and</strong> it. [. . .] You just connect.<br />

It may not be something that anybody else connects with, but it's like I<br />

get that, I underst<strong>and</strong> that feeling. I will always ®ght that literal<br />

impulse to lay everything directly in front of you. I just hate it.<br />

Some people are really good at narrative <strong>and</strong> some people are really<br />

good at action. I'm not that sort of person. So, if I'm going to do<br />

something, just let me do my thing <strong>and</strong> hope for <strong>the</strong> best. If you don't<br />

want me to do it, <strong>the</strong>n just don't have me do it. But if I do it, don't<br />

make me conform.<br />

(Salisbury, 2006: 114)<br />

<strong>The</strong> gaps are to be ®lled with what <strong>Burton</strong> calls `<strong>the</strong> feeling', <strong>and</strong> what<br />

Tarkovsky describes as `something amorphous, vague, with no skeleton<br />

or schema. Like a cloud' (Tarkovsky, 1989: 23). Throughout his book<br />

Tarkovsky states that he prefers freedom of expression to any <strong>the</strong>ories,<br />

formulas, schemas or threadbare tricks. Like <strong>Burton</strong>, he does not normally<br />

describe his works in technical terms, attempting instead to paint `a feeling'.<br />

Narrative causality, in Tarkovsky's view, should be replaced with `poetic<br />

articulation': `<strong>The</strong>re are some aspects of human life that can only be faithfully<br />

represented through poetry. But this is where directors very often try to<br />

use clumsy, conventional gimmickry instead of poetic logic. I'm thinking of<br />

illusionism <strong>and</strong> extraordinary effects involved in dreams, memories <strong>and</strong><br />

fantasies. All too often ®lm dreams are made into a collection of oldfashioned<br />

®lmic tricks, <strong>and</strong> cease to be a phenomenon of life' (2000: 30).<br />

For <strong>Tim</strong> <strong>Burton</strong>, too, <strong>the</strong> poetry of <strong>the</strong> image comes ®rst. This `symbolic'<br />

approach seems to be dictated by <strong>the</strong> speci®cs of his creativity. By his own<br />

http://www.jungarena.com/tim-burton-<strong>the</strong>-monster-<strong>and</strong>-<strong>the</strong>-crowd-9780415489713

16 Introduction<br />

admission, his creative process is more intuitive than intellectual: `I don't<br />

trust my intellect as much, because it's kind of schizy,' <strong>Burton</strong> admits, `I<br />

feel more grounded going with a feeling' (Woods, 2002: 41). He starts with<br />

a vague image, <strong>and</strong> goes on to create a numinous symbol which often has<br />

personal signi®cance for him, such as a dishevelled boy with scissors instead<br />

of h<strong>and</strong>s, a rugged madman who calls himself a `bio-exorcist', a menacing<br />

urban panorama, a spooky countryside l<strong>and</strong>scape. <strong>The</strong> image of Edward<br />

Scissorh<strong>and</strong>s, for instance, `came subconsciously <strong>and</strong> was linked to a character<br />

who wants to touch but can't; who was both creative <strong>and</strong> destructive<br />

...Itwasvery much linked to a feeling' (Salisbury, 2006: 87).<br />

However, <strong>Burton</strong>'s habit of reworking existing narratives does not<br />

indicate a lack of creativity or de®ciency of imagination. It is true that he<br />

prefers to work with popular myths, but gives <strong>the</strong>m a new visual interpretation.<br />

His versions of pre-existent symbols ± <strong>the</strong> Joker, Batman, Willy<br />

Wonka, Topps Cards Martians, talking apes, Sweeney Todd ± if <strong>the</strong>y do<br />

not always outshine <strong>the</strong> original, are never<strong>the</strong>less instantly recognisable <strong>and</strong><br />

visually striking. Moreover, <strong>the</strong> distinctiveness <strong>and</strong> numinosity of his<br />

symbols compensate for <strong>the</strong> inadequacy of technical <strong>and</strong> narrative elements.<br />

With Edward Scissorh<strong>and</strong>s for a central character, one cannot<br />

lament <strong>the</strong> absence of a clever rhythmic pattern, inventively striking juxtapositions<br />

or intriguingly non-linear narrative. However eloquent <strong>and</strong><br />

beautiful <strong>the</strong>se tricks can be, <strong>Tim</strong> <strong>Burton</strong> simply does not need <strong>the</strong>m to get<br />

his message across. When he wants to tell a story ± his story ± he does not<br />

re®ne it until it becomes a shiny, robotic work of art. He leaves it in a<br />

vaguely raw, half-unconscious (his hallmark), twilight state, devoid of <strong>the</strong><br />

smoothness of <strong>the</strong> classic narrative ®lm on <strong>the</strong> one h<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> sharp<br />

precision of thought which is so typical of intellectual ®lmmaking on <strong>the</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>r. <strong>The</strong>re is enough power in Edward to charge <strong>the</strong> ®lm with energy <strong>and</strong><br />

poignancy. <strong>The</strong> creature with scissors is multi-layered <strong>and</strong> complex enough<br />

as a symbol to invite multiple, <strong>and</strong> con¯icting, interpretations.<br />

To sum up <strong>the</strong> ideas discussed on <strong>the</strong> previous pages ± <strong>Burton</strong> looks as<br />

unnatural in <strong>the</strong> `highbrow' corner as he does among <strong>the</strong> gang of `meaningless<br />

action' directors. All <strong>the</strong> while, his style is unique <strong>and</strong> easily recognisable,<br />

with repeating visual <strong>and</strong> narrative patterns. He tends to neglect <strong>the</strong><br />

textual aspect of ®lm; <strong>and</strong> in doing this, he places `<strong>the</strong> image' higher than<br />

`<strong>the</strong> word'. Consequently, <strong>the</strong> cinematic, `moving' narrative suffers alongside<br />

<strong>the</strong> textual aspect (storyline, dialogues, extradiegetic voices). In addition,<br />

he predominantly operates with simple, myth-like compositions. His<br />

®lms foreground `bigger' symbolism at <strong>the</strong> expense of syntactic intricacy<br />

<strong>and</strong> diegetic ploys, <strong>and</strong> gravitate towards intense <strong>and</strong> vivid, but less<br />

detailed, models <strong>and</strong> blocks. This inevitably steers <strong>Burton</strong>'s creative vision<br />

towards <strong>the</strong> realm of <strong>the</strong> fantastic, where such means of expression are<br />

appropriate, while almost totally neglecting realistic genres. <strong>Burton</strong> certainly<br />

feels `at home' with a number of traditionally popular genres such as<br />

http://www.jungarena.com/tim-burton-<strong>the</strong>-monster-<strong>and</strong>-<strong>the</strong>-crowd-9780415489713

science ®ction, fantasy, horror, myth <strong>and</strong> mystery, <strong>and</strong> freely uses dark <strong>and</strong><br />

Gothic imagery.<br />

His persistent use of simpli®ed mythological frames does not mean,<br />

however, that he misses out on psychological complexity. <strong>The</strong> psychological<br />

depth of <strong>Burton</strong>'s ®lms is as intense as that of a S Ï vankmajer or Lynch ± but<br />

his is <strong>the</strong> archetypal insight of a good fairy tale. Moreover, <strong>the</strong> lucidity of<br />

his narratives allows <strong>the</strong> audience to access this psychological content<br />

quicker, <strong>and</strong> appreciate it more fully. Far from being plain, downmarket<br />

<strong>and</strong> populist, <strong>Burton</strong>'s narratives are uncluttered, powerful <strong>and</strong> topical.<br />

Nei<strong>the</strong>r does he seem to care whe<strong>the</strong>r his material is original, <strong>and</strong> to what<br />

degree. His interpretations, however, are undoubtedly original <strong>and</strong> ± what<br />

is more important ± personal. Whatever images he utilises ± be it <strong>the</strong><br />

Frankenstein monster in <strong>the</strong> form of a little dog, Dracula in <strong>the</strong> guise of<br />

drug-dependent Bela Lugosi in Ed Wood, or <strong>the</strong> Penguin man who, in this<br />

version, behaves like a mistreated child ± <strong>the</strong> director always moulds <strong>the</strong>m<br />

into a story about a misunderstood, lonely outcast; or at least links <strong>the</strong>m to<br />

such a story.<br />

People who interview <strong>Tim</strong> <strong>Burton</strong> often notice his clumsiness, his introversion<br />

<strong>and</strong> his inability to express himself clearly <strong>and</strong> coherently. His<br />

creativity clearly visual <strong>and</strong> not linguistic, he often looks at a loss when<br />

trying to explain to journalists why <strong>and</strong> how he did a certain thing in his<br />

®lm. And journalists, usually being watchful <strong>and</strong> perceptive, notice his<br />

communication weaknesses immediately. One of his interviewers, David<br />

Edelstein, wrote: `To quote him is not to get him right; you miss <strong>the</strong> air of<br />

stoned melancholy, <strong>the</strong> spastically gesticulating h<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> sentences<br />