Schottenstein Case Law to Trial Brief - Ninth Judicial Circuit Court of ...

Schottenstein Case Law to Trial Brief - Ninth Judicial Circuit Court of ...

Schottenstein Case Law to Trial Brief - Ninth Judicial Circuit Court of ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

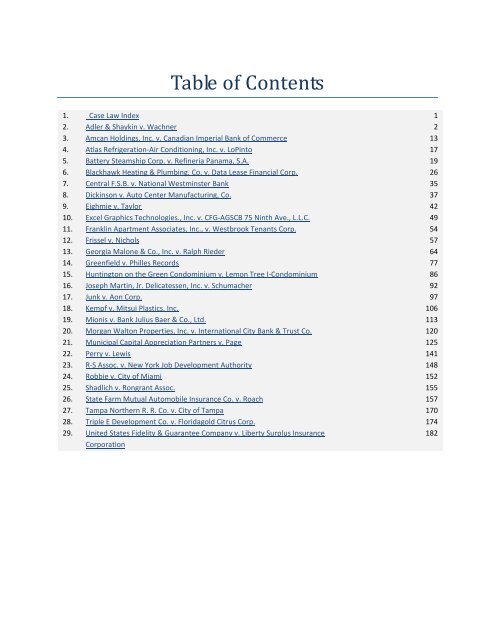

Table <strong>of</strong> Contents<br />

1. <strong>Case</strong> <strong>Law</strong> Index 1<br />

2. Adler & Shaykin v. Wachner 2<br />

3. Amcan Holdings, Inc. v. Canadian Imperial Bank <strong>of</strong> Commerce 13<br />

4. Atlas Refrigeration-Air Conditioning, Inc. v. LoPin<strong>to</strong> 17<br />

5. Battery Steamship Corp. v. Refineria Panama, S.A. 19<br />

6. Blackhawk Heating & Plumbing, Co. v. Data Lease Financial Corp. 26<br />

7. Central F.S.B. v. National Westminster Bank 35<br />

8. Dickinson v. Au<strong>to</strong> Center Manufacturing, Co. 37<br />

9. Eighmie v. Taylor 42<br />

10. Excel Graphics Technologies., Inc. v. CFG-AGSCB 75 <strong>Ninth</strong> Ave., L.L.C. 49<br />

11. Franklin Apartment Associates, Inc., v. Westbrook Tenants Corp. 54<br />

12. Frissel v. Nichols 57<br />

13. Georgia Malone & Co., Inc. v. Ralph Rieder 64<br />

14. Greenfield v. Philles Records 77<br />

15. Hunting<strong>to</strong>n on the Green Condominium v. Lemon Tree I-Condominium 86<br />

16. Joseph Martin, Jr. Delicatessen, Inc. v. Schumacher 92<br />

17. Junk v. Aon Corp. 97<br />

18. Kempf v. Mitsui Plastics, Inc. 106<br />

19. Mionis v. Bank Julius Baer & Co., Ltd. 113<br />

20. Morgan Wal<strong>to</strong>n Properties, Inc. v. International City Bank & Trust Co. 120<br />

21. Municipal Capital Appreciation Partners v. Page 125<br />

22. Perry v. Lewis 141<br />

23. R-S Assoc. v. New York Job Development Authority 148<br />

24. Robbie v. City <strong>of</strong> Miami 152<br />

25. Shadlich v. Rongrant Assoc. 155<br />

26. State Farm Mutual Au<strong>to</strong>mobile Insurance Co. v. Roach 157<br />

27. Tampa Northern R. R. Co. v. City <strong>of</strong> Tampa 170<br />

28. Triple E Development Co. v. Floridagold Citrus Corp. 174<br />

29. United States Fidelity & Guarantee Company v. Liberty Surplus Insurance<br />

Corporation<br />

182

<strong>Schottenstein</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Trial</strong><br />

<strong>Brief</strong><br />

CASE LAW INDEX TO DEFENDANT’S TRIAL MEMORANDUM<br />

VINTAGE CAPITAL MANAGEMENT, LLC, ET AL. V. ARI SCHOTTENSTEIN<br />

CASE NO.: 2010 CA 017823-O<br />

TAB CASE CITE<br />

1. Adler & Shaykin v. Wachner 721 F. Supp. 472<br />

2. Amcan Holdings, Inc. v. Canadian Imperial Bank <strong>of</strong> Commerce 70 A.D.3d 423<br />

3. Atlas Refrigeration-Air Conditioning, Inc. v. LoPin<strong>to</strong> 821 N.Y.S.2d 900<br />

4. Battery Steamship Corp. v. Refineria Panama, S.A. 513 F.2d 735<br />

5. Blackhawk Heating & Plumbing, Co. v. Data Lease Financial Corp. 302 So.2d 404<br />

6. Central F.S.B. v. National Westminster Bank 176 A.D.2d 131<br />

7. Dickinson v. Au<strong>to</strong> Center Manufacturing, Co. 639 F2d 250<br />

8. Eighmie v. Taylor 98 N.Y. 288<br />

9.<br />

Excel Graphics Technologies, Inc. v. CFG/AGSCB 75 <strong>Ninth</strong> Ave.,<br />

L.L.C.<br />

767 N.Y.S. 2d 99<br />

10. Franklin Apartment Associates, Inc., v. Westbrook Tenants Corp. 43 A.D. 3d 860<br />

11. Frissel v. Nichols 114 So. 431<br />

12. Georgia Malone & Co., Inc. v. Ralph Rieder 926 N.Y.S.2d 494<br />

13. Greenfield v. Philles Records 98 N.Y.2d 562<br />

14.<br />

Hunting<strong>to</strong>n on the Green Condominium v. Lemon Tree I-<br />

Condominium<br />

874 So.2d 1<br />

15. Joseph Martin, Jr. Delicatessen, Inc. v. Schumacher 417 N.E. 2d 541<br />

16. Junk v. Aon Corp. 2007 WL 4292034<br />

17. Kempf v. Mitsui Plastics, Inc. 1996 WL 673812<br />

18. Mionis v. Bank Julius Baer & Co., Ltd. 749 N.Y.S.2d 497<br />

19.<br />

Morgan Wal<strong>to</strong>n Properties, Inc. v. International City Bank & Trust<br />

Co.<br />

404 So.2d 1059<br />

20. Mun. Capital Appreciation Partners v. Page 181 F. Supp. 2d 379<br />

21. Perry v. Lewis 6 Fla. 555<br />

22. R/S Assoc. v. New York Job Development Authority 98 N.Y.2d 29<br />

23. Robbie v. City <strong>of</strong> Miami 469 So.2d 1384<br />

24. Shadlich v. Rongrant Assoc. 66 AD3d 759<br />

25. State Farm Mutual Au<strong>to</strong>mobile Insurance Co. v. Roach 945 So.2d 1160<br />

26. Tampa Northern R. R. Co. v. City <strong>of</strong> Tampa 140 So. 311<br />

27. Triple E Development Co. v. Floridagold Citrus Corp. 51 So.2d 435<br />

28.<br />

United States Fidelity & Guarantee Company v. Liberty Surplus<br />

Insurance Corporation,<br />

550 F.3d 1031<br />

Page 1 <strong>of</strong> 185

<strong>Schottenstein</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Trial</strong><br />

<strong>Brief</strong><br />

721F.Supp.472<br />

(Citeas:721F.Supp.472)<br />

UnitedStatesDistrict<strong>Court</strong>,<br />

S.D.NewYork.<br />

ADLER&SHAYKIN,aNewYorkpartnership,<br />

PlaintiffandCounterclaimDefendant,<br />

v.<br />

LindaJ.WACHNER,DefendantandCounterclaim<br />

Plaintiff.<br />

No.87Civ.6938(JMW).<br />

Dec.12,1988.<br />

Partnership brought action for the return <strong>of</strong> a<br />

portion <strong>of</strong> defendant's distribution from plaintiff's<br />

settlement with a third party, which distribution<br />

was paid <strong>to</strong> defendant under a written agreement.<br />

The parties cross-moved for summary judgment.<br />

TheDistrict<strong>Court</strong>,Walker,J.,heldthatparolevidence<br />

<strong>of</strong> an alleged oral agreement concerning defendant'sdistributionwasinadmissible.<br />

Defendant'smotiongranted.<br />

WestHeadnotes<br />

[1]Evidence157 397(2)<br />

157Evidence<br />

157XI Parol or Extrinsic Evidence Affecting<br />

Writings<br />

157XI(A)Contradicting,Varying,orAdding<br />

<strong>to</strong>Terms<strong>of</strong>WrittenInstrument<br />

157k397ContractsinGeneral<br />

157k397(2)k.Completeness<strong>of</strong>Writing<br />

and Presumption in Relation There<strong>to</strong>; Integration.MostCited<strong>Case</strong>s<br />

If parties have reduced their agreement <strong>to</strong> integratedwriting,parolevidenceruleoperates<strong>to</strong>excludeevidence<strong>of</strong>allpriororcontemporaneousnegotiations<br />

or agreements <strong>of</strong>fered <strong>to</strong> contradict or<br />

modifyterms<strong>of</strong>theirwriting.<br />

[2]Evidence157 397(2)<br />

157Evidence<br />

157XI Parol or Extrinsic Evidence Affecting<br />

Writings<br />

157XI(A)Contradicting,Varying,orAdding<br />

<strong>to</strong>Terms<strong>of</strong>WrittenInstrument<br />

157k397ContractsinGeneral<br />

157k397(2)k.Completeness<strong>of</strong>Writing<br />

and Presumption in Relation There<strong>to</strong>; Integration.MostCited<strong>Case</strong>sPartyrelyingonparolevidencerule<strong>to</strong>baradmission<strong>of</strong>evidencemustfirstshowthatagreement<br />

is integrated, which is <strong>to</strong> say, that writing completelyandaccuratelyembodiesall<strong>of</strong>mutualrights<br />

and obligations <strong>of</strong> parties; under New York law,<br />

contract which appears complete on its face is integratedagreementasmatter<strong>of</strong>law.<br />

[3]Evidence157 397(2)<br />

157Evidence<br />

157XI Parol or Extrinsic Evidence Affecting<br />

Writings<br />

157XI(A)Contradicting,Varying,orAdding<br />

<strong>to</strong>Terms<strong>of</strong>WrittenInstrument<br />

157k397ContractsinGeneral<br />

157k397(2)k.Completeness<strong>of</strong>Writing<br />

and Presumption in Relation There<strong>to</strong>; Integration.MostCited<strong>Case</strong>s<br />

Under New York contract law, in absence <strong>of</strong><br />

mergerclause,courtmustdeterminewhetherornot<br />

there is integration by reading writing in light <strong>of</strong><br />

surrounding circumstances, and by determining<br />

whether or not agreement was one which parties<br />

would ordinarily be expected <strong>to</strong> embody in the<br />

writing.<br />

[4]Evidence157 442(1)<br />

©2012ThomsonReuters.NoClaim<strong>to</strong>Orig.USGov.Works.<br />

Page1<br />

157Evidence<br />

157XI Parol or Extrinsic Evidence Affecting<br />

Writings<br />

157XI(C) Separate or Subsequent Oral<br />

Agreement<br />

157k440PriorandContemporaneousCol-<br />

Page 2 <strong>of</strong> 185

<strong>Schottenstein</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Trial</strong><br />

<strong>Brief</strong><br />

721F.Supp.472<br />

(Citeas:721F.Supp.472)<br />

lateralAgreements<br />

157k442Completeness<strong>of</strong>Writing<br />

157k442(1)k.InGeneral.Most<br />

Cited<strong>Case</strong>s<br />

Parol evidence rule operated <strong>to</strong> exclude evidence<strong>of</strong>allegedoralagreementbydefendant<strong>to</strong>return<br />

portion <strong>of</strong> her distribution from settlement<br />

amountincaseplaintiffhad<strong>to</strong>paymore<strong>to</strong>itslimitedpartners;partiesintendedagreement<strong>to</strong>contain<br />

mutual promises <strong>of</strong> parties with respect <strong>to</strong> settlement<br />

amount, and thus it was valid integrated<br />

agreement.<br />

[5]Evidence157 442(1)<br />

157Evidence<br />

157XI Parol or Extrinsic Evidence Affecting<br />

Writings<br />

157XI(C) Separate or Subsequent Oral<br />

Agreement<br />

157k440PriorandContemporaneousCollateralAgreements<br />

157k442Completeness<strong>of</strong>Writing<br />

157k442(1)k.InGeneral.Most<br />

Cited<strong>Case</strong>s<br />

Evenifagreementisintegrated,parolevidence<br />

maycomeinifallegedagreementiscollateral,that<br />

is, one which is separate, independent, and complete,althoughrelating<strong>to</strong>sameobject.<br />

[6]Evidence157 441(1)<br />

157Evidence<br />

157XI Parol or Extrinsic Evidence Affecting<br />

Writings<br />

157XI(C) Separate or Subsequent Oral<br />

Agreement<br />

157k440PriorandContemporaneousCollateralAgreements<br />

157k441InGeneral<br />

157k441(1)k.InGeneral.Most<br />

Cited<strong>Case</strong>s<br />

Evidence in support <strong>of</strong> allegedly collateral<br />

agreement will be allowed only if agreement is in<br />

formacollateralone,agreementdoesnotcontradict<br />

excess or implied provisions <strong>of</strong> written contract,<br />

andagreementisonethatpartieswouldno<strong>to</strong>rdinarily<br />

be expected <strong>to</strong> embody in writing, i.e., oral<br />

agreement must not be so clearly connected with<br />

principaltransactionas<strong>to</strong>bepartandparcel<strong>of</strong>it.<br />

[7]Evidence157 441(1)<br />

157Evidence<br />

157XI Parol or Extrinsic Evidence Affecting<br />

Writings<br />

157XI(C) Separate or Subsequent Oral<br />

Agreement<br />

157k440PriorandContemporaneousCollateralAgreements<br />

157k441InGeneral<br />

157k441(1)k.InGeneral.Most<br />

Cited<strong>Case</strong>s<br />

Alleged oral agreement that defendant would<br />

return portion <strong>of</strong> her distribution from settlement<br />

agreement in case plaintiff had <strong>to</strong> pay more <strong>to</strong> its<br />

limited partners was not collateral <strong>to</strong> contract<br />

between defendant and plaintiff which addressed<br />

defendant's share <strong>of</strong> settlement; thus, parol evidencepertaining<strong>to</strong>allegedoralagreementwasinadmissible.<br />

[8]Evidence157 448<br />

157Evidence<br />

157XI Parol or Extrinsic Evidence Affecting<br />

Writings<br />

157XI(D) Construction or Application <strong>of</strong><br />

Language<strong>of</strong>WrittenInstrument<br />

157k448k.GroundsforAdmission<strong>of</strong>ExtrinsicEvidence.MostCited<strong>Case</strong>s<br />

Evenifagreementisintegrated,parolevidence<br />

may be admitted if underlying contract is ambiguous.<br />

[9]Evidence157 434(8)<br />

©2012ThomsonReuters.NoClaim<strong>to</strong>Orig.USGov.Works.<br />

Page2<br />

157Evidence<br />

157XI Parol or Extrinsic Evidence Affecting<br />

Writings<br />

157XI(B)InvalidatingWrittenInstrument<br />

157k434Fraud<br />

Page 3 <strong>of</strong> 185

<strong>Schottenstein</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Trial</strong><br />

<strong>Brief</strong><br />

721F.Supp.472<br />

(Citeas:721F.Supp.472)<br />

157k434(8)k.InContractsinGeneral.<br />

MostCited<strong>Case</strong>s<br />

Parol evidence rule has no application in suit<br />

brought<strong>to</strong>rescindcontrac<strong>to</strong>nground<strong>of</strong>fraud.<br />

[10]Fraud184 41<br />

184Fraud<br />

184IIActions<br />

184II(C)Pleading<br />

184k41k.Allegations<strong>of</strong>FraudinGeneral.MostCited<strong>Case</strong>s<br />

UnderNewYorklaw,<strong>to</strong>pleadprimafaciecase<br />

<strong>of</strong>fraud,plaintiffmustallegerepresentation<strong>of</strong>materialexistingfact,falsity,scienter,deception,and<br />

injury.<br />

[11]Fraud184 12<br />

184Fraud<br />

184IDeceptionConstitutingFraud,andLiabilityTherefor<br />

184k8FraudulentRepresentations<br />

184k12k.ExistingFactsorExpectations<br />

orPromises.MostCited<strong>Case</strong>s<br />

Contractualpromisemadewithundisclosedintentionnot<strong>to</strong>performitconstitutesfraudand,despite<br />

so-called merger clause, plaintiff is free <strong>to</strong><br />

provehewasinducedbyfalseandfraudulentmisrepresentations.<br />

[12] Implied and Constructive Contracts 205H<br />

55<br />

205HImpliedandConstructiveContracts<br />

205HINatureandGrounds<strong>of</strong>Obligation<br />

205HI(D)Effec<strong>to</strong>fExpressContract<br />

205Hk55k.InGeneral.MostCited<strong>Case</strong>s<br />

Existence<strong>of</strong>validandenforceablewrittencontract<br />

governing particular subject matter ordinarily<br />

precludes recovery in quasi contract for events<br />

arisingou<strong>to</strong>fsamesubjectmatter.<br />

*474 Russell E. Brooks, Milbank, Tweed, Hadley<br />

&McCloy,NewYorkCity,fordefendant.<br />

JosephS.Allerhand,Weil,Gotshal&Manges,New<br />

YorkCity,forplaintiff.<br />

©2012ThomsonReuters.NoClaim<strong>to</strong>Orig.USGov.Works.<br />

Page3<br />

OPINIONANDORDER<br />

WALKER,DistrictJudge:<br />

Currently before the <strong>Court</strong> are cross motions<br />

forsummaryjudgmentmadepursuant<strong>to</strong>Rule56<strong>of</strong><br />

theFederalRules<strong>of</strong>CivilProcedure.Forthereasons<br />

set forth below, the <strong>Court</strong> grants defendant's<br />

motion.Asaresult,the<strong>Court</strong>neednotaddressthe<br />

AmendedCounterclaims. FN1<br />

FN1.Wachner'sCounterclaimsarepleaded<br />

in the alternative. The <strong>Court</strong>'s disposition<br />

<strong>of</strong> her motion for summary judgment<br />

rendersthemmoot.<br />

BACKGROUND<br />

This case revolves around a series <strong>of</strong> agreements<br />

entered in<strong>to</strong> by the parties: the plaintiff,<br />

Adler&Shaykin(“A&S”),aNewYorkpartnershipbetweenFrederickAdlerandLeonardShaykin<br />

thatmanagesaleveragedbuyoutfund,thepurpose<br />

<strong>of</strong> which is <strong>to</strong> acquire equity in a series <strong>of</strong> leveragedacquisitions;andthedefendant,LindaWachner,<br />

now a Los Angeles executive who was first<br />

employedbyA&SinDecember<strong>of</strong>1984.Wachner<br />

hasmovedforsummaryjudgmentandthushasthe<br />

burden <strong>of</strong> establishing that no genuine dispute exists<br />

as <strong>to</strong> any material fact. See, e.g., Beyah v.<br />

Coughlin, 789 F.2d 986, 989 (2d Cir.1986).<br />

Moreover,“[a]mbiguitiesorinferences<strong>to</strong>bedrawn<br />

fromthefactsmustbeviewedinalightmostfavorable<br />

<strong>to</strong> the party opposing the summary judgment<br />

motion.”ProjectReleasev.Prevost,722F.2d960,<br />

968(2dCir.1983).<br />

Wachner and A & S entered in<strong>to</strong> their first<br />

agreement(“theRetentionAgreement”)onDecember14,1984.Bytheterms<strong>of</strong>theRetentionAgreement,<br />

Wachner was <strong>to</strong> identify potential acquisitionsforA&Sinthebeautymarketandthenhead<br />

the acquired company. A & S formed the Beauty<br />

AcquisitionCorporation(“BAC”)forthatpurpose.<br />

Afterseveralmonths,BACagreed<strong>to</strong>buyRevlon's<br />

beautyandfragrancesbusiness(“theBACTransac-<br />

Page 4 <strong>of</strong> 185

<strong>Schottenstein</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Trial</strong><br />

<strong>Brief</strong><br />

721F.Supp.472<br />

(Citeas:721F.Supp.472)<br />

tion”).However,byDecember<strong>of</strong>1985,Wachner's<br />

RetentionAgreementwithA&Shadexpired;the<br />

BAC Transaction had collapsed due <strong>to</strong> Pantry<br />

Pride's acquisition <strong>of</strong> Revlon; and A & S faced a<br />

drawnoutlitigationagainstRevlon.TheRetention<br />

Agreement between the parties had no provision<br />

that would entitle Wachner <strong>to</strong> any share <strong>of</strong><br />

whatever break-up fees or damages A & S might<br />

eventuallyrecoverfromRevlon.Asaresult,Wachner<br />

and Adler negotiated an agreement dated<br />

December 12, 1985 (“the 1985 Agreement”). That<br />

agreementaddressedvariousdistributionpossibilities<strong>of</strong>anybreak-upfeereceivedfromRevlon.<br />

FN2<br />

FN2. Paragraph Three <strong>of</strong> the 1985 Agreementcontainedfoursubparagraphsthataddressedthebreak-upfee:<br />

a)Firstshallbedeductedallexpenses...<br />

b) Then shall be deducted any amounts<br />

due<strong>to</strong>theBanksandEquitable[A&S's<br />

lenders,who,aseventsturnedout,were<br />

paid a separate break-up fee <strong>of</strong> $21.3<br />

millionbyRevlononOc<strong>to</strong>ber27,1986.<br />

Thisprovisionandtheseparatebreak-up<br />

fee <strong>to</strong> the lenders in part form the basis<br />

for Wachner's counterclaims. See below.]<br />

c)Then<strong>of</strong>thefirst$20,000,000breakup<br />

fee or settlement paid, you shall be entitled<strong>to</strong>25%<strong>of</strong>thenetpr<strong>of</strong>itsbeforeallocution<strong>to</strong>limitedpartners.<br />

d) Then <strong>of</strong> amounts in excess <strong>of</strong> such<br />

gross $20,000,000, you shall be entitled<br />

<strong>to</strong>15%<strong>of</strong>thenetpr<strong>of</strong>itscomputedafter<br />

deduction<strong>of</strong>anypaymentsmade<strong>to</strong>limitedpartners.<br />

After several months <strong>of</strong> litigation, on December2,1986,Revlonpaida$23.7millionbreak-up<br />

fee(“theSettlementAmount”)<strong>to</strong>A&Spursuant<strong>to</strong><br />

theSettlementAgreementnegotiatedbytheparties.<br />

A letter agreement between A & S and Wachner,<br />

©2012ThomsonReuters.NoClaim<strong>to</strong>Orig.USGov.Works.<br />

Page4<br />

dated December 5, 1986 (“the 1986 Agreement”),<br />

addressed her share <strong>of</strong> that fee. The 1986 Agreement<br />

runs a little longer than two full, singlespaced<br />

typewritten pages. Following an introduc<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

paragraph that refers its readers <strong>to</strong> the 1985<br />

Agreement as well as other relevant *475 agreements,<br />

the 1986 Agreement provides: “In view <strong>of</strong><br />

the settlement provided in the Settlement Agreement,<br />

it is agreed as follows ...” The agreement<br />

betweenA&SandWachnerprovidesthat,inconsideration<strong>of</strong>$2.785million<strong>to</strong>Wachner,shewould<br />

releaseA&Sandrelatedentitiesfromallactions<br />

and future demands regarding the Settlement<br />

Agreement. The 1986 Agreement also outlined in<br />

detail, with several formulae, an agreement<br />

between the parties that called for them <strong>to</strong> share<br />

whateverfuturetaxesmightbeassessedagainstthe<br />

SettlementAmount.<br />

According <strong>to</strong> A & S, at the time <strong>of</strong> the 1986<br />

Agreement,thepartiesentered in<strong>to</strong>aseparateoral<br />

“understanding.” Wachner disputes this claim, but<br />

for the purposes <strong>of</strong> her motion for summary judgment,<br />

the <strong>Court</strong> accepts A & S's recitation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

facts.Theterms<strong>of</strong>this“understanding”werethat<br />

we[A&S]wouldpayher[Wachner]theamount<br />

shewasentitled<strong>to</strong>receiveundertheformulawe<br />

hadworkedout($2,785,000),based,however,on<br />

the planned distribution <strong>of</strong> $4,600,000 <strong>to</strong> the<br />

LimitedPartners[fromtheabortedBACTransaction].Inligh<strong>to</strong>fthefactthattheLimitedPartnerswereobjecting<strong>to</strong>thatdistributionandmightultimately<br />

succeed in causing A & S <strong>to</strong> increase it,<br />

Wachner and I [Adler] further agreed that her<br />

sharewouldberecalculatedifandwhenwehad<br />

<strong>to</strong> increase the payment <strong>to</strong> the Limited Partners<br />

andshewouldrepaythedifference.<br />

AdlerAff.¶15.Adleragreed<strong>to</strong>payWachner<br />

her share before a final determination <strong>of</strong> what the<br />

Limited Partners would get because Wachner<br />

“needed money. She owed a lot <strong>of</strong> money <strong>to</strong> the<br />

banks, money on which she was paying interest.”<br />

AdlerDep.at23-24.AdlerandWachnerwerealso<br />

longtime friends. Wachner and Shaykin, however,<br />

Page 5 <strong>of</strong> 185

<strong>Schottenstein</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Trial</strong><br />

<strong>Brief</strong><br />

721F.Supp.472<br />

(Citeas:721F.Supp.472)<br />

were not on friendly terms. Indeed, he described<br />

howattimeshehad<strong>to</strong>withdrawfromnegotiations<br />

with Wachner over the 1985 Agreement because<br />

the negotiations had become “so acrimonious.”<br />

Shaykin Dep. at 129. The two engaged in at least<br />

one“heateddiscussion.”Id.at56.<br />

Because<strong>of</strong>hisfriendshipwithWachner,Adler<br />

didnotfeelitwasnecessary<strong>to</strong>memorializehisfurtherunderstandingwithWachnerthatshemightreturn<br />

a portion <strong>of</strong> her share <strong>of</strong> the Settlement<br />

Amount.HeandWachnerhadaseries<strong>of</strong>conversationsduringwhichsheneverquestionedherobligation<br />

<strong>to</strong> return a portion <strong>of</strong> the money, but rather<br />

only questioned the amount. Wachner <strong>to</strong>ld Adler<br />

thatshewanted<strong>to</strong>bekeptadvised<strong>of</strong>A&S'scontinued<br />

dealings with its Limited Partners. In her<br />

ownwords,shewanted“<strong>to</strong>seeandunderstandany<br />

givebacks” <strong>to</strong> the “Limited Partners” and “wanted<br />

<strong>to</strong>beapar<strong>to</strong>fit.”WachnerDep.at144.<br />

Furthermore, Adler felt it was unwise <strong>to</strong> raise<br />

the possibility <strong>of</strong> additional payments <strong>to</strong> A & S's<br />

limited partners “in a writing [ ] the Limited Partners<br />

had every right <strong>to</strong> view”: “Such a provision<br />

wouldhavefueledthedisputebetweenA&Sand<br />

the Limited Partners concerning how much the<br />

Limited Partners were <strong>to</strong> receive.” Pl.'s Mem. in<br />

Opp.at19-20.<br />

Asitturnedout,onApril23,1987,A&Spaid<br />

itsLimitedPartnersroughly$9.94million,not$4.6<br />

million.Fromthepaperssubmitted,itremainsunclear<br />

why A & S increased the distribution <strong>to</strong> its<br />

LimitedPartners.Atthehearingbeforethis<strong>Court</strong>,<br />

A&Sadmittedthatithasacontinuingrelationship<br />

withitsLimitedPartners,uponwhomitexpects<strong>to</strong><br />

relyinfuturetransactions.A&S<strong>of</strong>ferednothing<strong>to</strong><br />

contradictWachner'sassertionthatA&Sincreased<br />

thepayment<strong>to</strong>theLimitedPartnersinorder<strong>to</strong>insure<br />

a continued harmonious and productive business<br />

relationship. Based upon the actual distribution,A&SnotifiedWachnerthatsheowedanadditional<br />

$810,375. By May <strong>of</strong> 1987, Shaykin, on<br />

behalf <strong>of</strong> A & S, forwarded <strong>to</strong> Wachner a “new<br />

Agreementpreparedforthepurpose<strong>of</strong>superceding<br />

[sic][the1986Agreement].”<br />

ThisMay1987Agreementisvirtuallyidentical<br />

<strong>to</strong> the 1986 Agreement except for the fact that it<br />

takes in<strong>to</strong> consideration Wachner's alleged oral<br />

agreement <strong>to</strong> return a portion <strong>of</strong> her distribution<br />

fromtheSettlementAmountincaseA&Shad<strong>to</strong><br />

*476paymore<strong>to</strong>itsLimitedPartners.Asaresult,<br />

itprovidesforWachner<strong>to</strong>return$810,375<strong>to</strong>A&<br />

S.TheMay1987Agreementstates:“Exceptasexpresslysetforthherein,the1986Letterwillremain<br />

infullforceandeffect(includingbutnotlimited<strong>to</strong><br />

the release and tax indemnification provisions<br />

there<strong>of</strong>).” The May 1987 Agreement, like all the<br />

previous agreements between the parties, did not<br />

containamergerorintegrationclause.<br />

Some time after the parties entered in<strong>to</strong> the<br />

1986Agreement,Wachnerrepaida$50,000loan<strong>to</strong><br />

A&S.Theloanwasoriginallymade<strong>to</strong>coverexpenses<br />

Wachner had incurred while working in<br />

NewYorkforA&SontheproposedBACTransaction.<br />

A & S brought this action <strong>to</strong> recover that<br />

$810,375.Relyingonthe1986Agreementandthe<br />

parol evidence rule, Wachner moved for summary<br />

judgment and, in the alternative, asserted as counterclaims<br />

her right <strong>to</strong> an additional $1.97 million,<br />

based upon what she argues is the correct calculation-given<br />

the formulae in the 1985 Agreement-<strong>of</strong><br />

hershare<strong>of</strong>theSettlementAmount.Inaddition<strong>to</strong><br />

opposing Wachner's motion, A & S cross-moved<br />

for summary judgment on Wachner's amended<br />

counterclaims based on Wachner's release in the<br />

1986 Agreement. After a careful reading <strong>of</strong> the<br />

parties'papers,depositionsandaffidavits;andafter<br />

oralargument,the<strong>Court</strong>grantssummaryjudgment<br />

forWachner.Hercounterclaimsarethusmoot.<br />

DISCUSSION<br />

A.TheParolEvidenceRule:<br />

1.Integration:<br />

©2012ThomsonReuters.NoClaim<strong>to</strong>Orig.USGov.Works.<br />

Page5<br />

[1]Wherethepartieshavereducedtheiragree-<br />

Page 6 <strong>of</strong> 185

<strong>Schottenstein</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Trial</strong><br />

<strong>Brief</strong><br />

721F.Supp.472<br />

(Citeas:721F.Supp.472)<br />

ment <strong>to</strong> an integrated writing, the parol evidence<br />

rule operates <strong>to</strong> exclude evidence <strong>of</strong> all prior or<br />

contemporaneous negotiations or agreements<br />

<strong>of</strong>fered <strong>to</strong> contradict or modify the terms <strong>of</strong> their<br />

writing. See, e.g., Marine Midland Bank-Southern<br />

v.Thurlow,53N.Y.2d381,387,442N.Y.S.2d417,<br />

419-420, 425 N.E.2d 805, 807-08 (1981).<br />

(“Although at times this rule may seem <strong>to</strong> be unjust,‘onthewholeitworksforgood’byallowinga<br />

party <strong>to</strong> a written contract <strong>to</strong> protect himself from<br />

‘perjury, infirmity <strong>of</strong> memory or the death <strong>of</strong> witnesses.’”)(citationsomitted).SeealsoMeinrathv.<br />

Singer, 482 F.Supp. 457, 460 (S.D.N.Y.1979)<br />

(“One <strong>of</strong> the oldest and most settled principles <strong>of</strong><br />

NewYorklawisthatapartymayno<strong>to</strong>fferpro<strong>of</strong><strong>of</strong><br />

prior oral statements <strong>to</strong> alter or refute the clear<br />

meaning <strong>of</strong> unambiguous terms <strong>of</strong> written, integratedcontracts<strong>to</strong>whichassenthasvoluntarilybeen<br />

given”) (Weinfeld, J.) (footnote omitted), aff'd<br />

withou<strong>to</strong>p.,697F.2d293(2dCir.1982).<br />

[2]Thepartyrelyingontherule<strong>to</strong>bartheadmission<strong>of</strong>evidencemustfirstshowthattheagreementisintegrated,whichis<strong>to</strong>say,thatthewritingcompletelyandaccuratelyembodiesall<strong>of</strong>themutualrightsandobligations<strong>of</strong>theparties.See,e.g.,<br />

Leev.JosephE.Seagram&Sons,Inc.,413F.Supp.<br />

693 (S.D.N.Y.1976), affirmed, 552 F.2d 447 (2d<br />

Cir.1977),Mitchillv.Lath,247N.Y.377,160N.E.<br />

646 (1928). And “under New York law a contract<br />

whichappearscompleteonitsfaceisanintegrated<br />

agreementasamatter<strong>of</strong>law.”BatteryS.S.Corp.v.<br />

RefineriaPanama,S.A.,513F.2d735,738n.3(2d<br />

Cir.1975), Happy Dack Trading Co., Ltd. v. Agro-<br />

Industries, Inc., 602 F.Supp. 986, 991<br />

(S.D.N.Y.1984).<br />

[3] However, under New York law, in the absence<strong>of</strong>amergerclause,“thecourtmustdetermine<br />

whether or not there is an integration ‘by reading<br />

the writing in the light <strong>of</strong> surrounding circumstances,<br />

and by determining whether or not the<br />

agreementwasonewhichthepartieswouldordinarily<br />

be expected <strong>to</strong> embody in the writing.’ ”<br />

Braten v. Bankers Trust Co., 60 N.Y.2d 155, 162,<br />

©2012ThomsonReuters.NoClaim<strong>to</strong>Orig.USGov.Works.<br />

Page6<br />

468 N.Y.S.2d 861, 864, 456 N.E.2d 802, 805<br />

(1983). The New York <strong>Court</strong> <strong>of</strong> Appeals long ago<br />

providedaguidelineforthisdetermination:<br />

Ifuponinspectionandstudy<strong>of</strong>thewriting,read,<br />

it may be, in the light <strong>of</strong> surrounding circumstances<br />

in order [<strong>to</strong> determine] <strong>to</strong> its proper understandingandinterpretation,itappears<strong>to</strong>containtheengagements<strong>of</strong>theparties,and<strong>to</strong>define<br />

*477 the object and measure the extent <strong>of</strong> such<br />

engagement, it constitutes the contract between<br />

them, and is presumed <strong>to</strong> contain the whole <strong>of</strong><br />

thatcontract.<br />

Eighmiev.Taylor,98N.Y.288(1885),Leev.<br />

Joseph E. Seagram & Sons, Inc., 413 F.Supp. at<br />

701(citationomitted).<br />

Fac<strong>to</strong>rs New York courts consider include:<br />

whetherthedocumentinquestionrefers<strong>to</strong>theoral<br />

agreement, or whether the alleged oral agreement<br />

betweentheparties“isthesor<strong>to</strong>fcomplexarrangement<br />

which is cus<strong>to</strong>marily reduced <strong>to</strong> writing”<br />

ManufacturersHanoverTrustCompanyv.Margolis,<br />

115 A.D.2d 406, 407-8, 496 N.Y.S.2d 36, 37<br />

(1stDep't1985);whetherthepartieswererepresentedbyexperiencedcounselwhentheyenteredin<strong>to</strong><br />

theagreement,Pecorellav.GreaterBuffaloPress,<br />

Inc., 84 A.D.2d 950, 446 N.Y.S.2d 709 (4th Dep't<br />

1981);whetherthepartiesandtheircounselnegotiatedduringalengthyperiod,resultinginaspecially<br />

drawnoutandexecutedagreement,andwhetherthe<br />

conditionatissueisfundamental,Bratenv.Bankers<br />

TrustCo.,60N.Y.2dat162,468N.Y.S.2dat864,<br />

456 N.E.2d at 805 (1983); if the contract, which<br />

does not include the standard integration clause,<br />

nonethelesscontainswordinglike“‘[i]nconsideration<br />

<strong>of</strong> the mutual promises herein contained, it is<br />

agreed and covenanted as follows,” and ends by<br />

statingthat‘theforegoingcorrectlysetsforthyour<br />

understanding <strong>of</strong> our Agreement’ ”, Lee v. Joseph<br />

E.Seagram&Sons,413F.Supp.at701.<br />

[4] Having examined both the document itself<br />

and the circumstances surrounding it, the <strong>Court</strong><br />

concludesthatthepartiesintendedthe1986Agree-<br />

Page 7 <strong>of</strong> 185

<strong>Schottenstein</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Trial</strong><br />

<strong>Brief</strong><br />

721F.Supp.472<br />

(Citeas:721F.Supp.472)<br />

ment<strong>to</strong>containthemutualpromises<strong>of</strong>theparties<br />

withrespect<strong>to</strong>theSettlementAmount.Itthusisa<br />

valid integrated agreement and the <strong>Court</strong> will excludeevidence<strong>of</strong>priororcontemporaneousnegotiationsoragreementswhichwouldvaryorbeinconsistentwithitsterms,aswouldtheallegedoralunderstandingbetweenAdlerandWachner.The<strong>Court</strong><br />

basesitsdecisiononseveralgrounds.<br />

The document itself supports the <strong>Court</strong>'s conclusion.Althoughthe1986Agreementcontainsno<br />

mergerclause,itdoescontainthewords:“Inview<br />

<strong>of</strong>thesettlementprovidedintheSettlementAgreement,itisagreedasfollows...”,and“Pleaseconfirmyouragreementwiththeforegoingbysigningandreturningacopy<strong>of</strong>thisletter...”Thewordsindicateanintention<strong>to</strong>addressfullytheissue<strong>of</strong>the<br />

Settlement Amount, and <strong>to</strong> be bound by the terms<br />

<strong>of</strong> the agreement. In addition, the superseding<br />

agreementproposedbyA&Sisvirtuallyidentical<br />

<strong>to</strong> the 1986 Agreement (with the exception <strong>of</strong><br />

providing for Wachner's repayment <strong>of</strong> $810,375).<br />

The superseding agreement also contains a provision<br />

that explains, “Except as expressly set forth<br />

herein,the1986Letterwillremaininfullforceand<br />

effect(includingbutnotlimited<strong>to</strong>thereleaseand<br />

taxindemnificationprovisionsthere<strong>of</strong>).”(emphasis<br />

added) The emphasized portion undercuts A & S's<br />

contention before this <strong>Court</strong> that the 1986 Agreement“merelycontainedtwosubstantiveprovisions:aone-wayreleasefromWachner<strong>to</strong>A&Sinconsideration<strong>of</strong>thepaymen<strong>to</strong>f$2,785,000anda‘tax<br />

indemnification’ from Wachner <strong>to</strong> A & S in the<br />

even<strong>to</strong>fanadversetaxruling...”Pl.'sMem.at16.<br />

Thepresence<strong>of</strong>aone-wayratherthanamutual<br />

release does not alter this <strong>Court</strong>'s conclusion that<br />

the 1986 Agreement was integrated. The <strong>Court</strong>'s<br />

own calculations, based on the formulae provided<br />

inthe1985Agreementthatgovernpotentialbreakupfees,convincesitthatA&Shadgoodreason<strong>to</strong><br />

seek a release from Wachner. Simply put-and<br />

without passing judgment on this point-based on<br />

the1985Agreement,hershare<strong>of</strong>thebreak-upfee<br />

arguablycouldhavebeensignificantlyhigherthan<br />

©2012ThomsonReuters.NoClaim<strong>to</strong>Orig.USGov.Works.<br />

Page7<br />

the$2.785millionprovidedforinthe1986Agreement.<br />

FN3 TherewasnoreasonforWachner<strong>to</strong>seek<br />

areleasefromA&S.The1986Agreementclearly<br />

addresses, and was clearly meant <strong>to</strong> address, a<br />

straightforward*478 transaction: in consideration<br />

forWachner'srelease,A&Spaidher$2.785million.<br />

FN3.Indeed,Wachner'sCounterclaimsbeforethis<strong>Court</strong>suggestjustthesor<strong>to</strong>flitigation<br />

one imagines A & S intended <strong>to</strong><br />

avoidbysecuringherrelease.<br />

Furthermore, the parties were represented and<br />

aidedbyexperiencedcounselindraftingtheagreementatissue.SeeShaykinDep.at67;19;135-36.<br />

The complex tax indemnification provision in the<br />

1986 Agreement reveals their ability <strong>to</strong> address a<br />

potential recalculation <strong>of</strong> Wachner's share <strong>of</strong> the<br />

SettlementAmountwhenthepartiessodesired.Regardless<br />

<strong>of</strong> whether the oral agreement was madeand,forthepurposes<strong>of</strong>thismotion,the<strong>Court</strong>assumes<br />

that it was-the <strong>Court</strong> concludes that it remainsjustthesor<strong>to</strong>fcomplexarrangementcus<strong>to</strong>marily<br />

reduced <strong>to</strong> writing and which the parties<br />

would ordinarily be expected <strong>to</strong> embody in the<br />

writing. See Braten, supra; Manufacturer's Hanover<br />

Trust, supra. It stretches credulity <strong>to</strong>o far <strong>to</strong><br />

believethat,aftermorethanayear<strong>of</strong>work,WachnerwouldgrantA&Swhatamounts<strong>to</strong>unlimited<br />

discretion<strong>to</strong>reducetheonethingshehad<strong>to</strong>show<br />

forherwork:$2.785million.Thesurroundingcircumstancesconvincethe<strong>Court</strong>thattheoralagreement<br />

was “so clearly connected with the principal<br />

transactionas<strong>to</strong>bepartandparcel<strong>of</strong>it.”Mitchill<br />

v.Lath,247N.Y.at381,160N.E.646.<br />

The <strong>Court</strong> is unconvinced by A & S's contentionthatthepartieshadanongoingrelationshipthatwas“nevergovernedbythestrictterms<strong>of</strong>contractualprovisions.”Pl.Mem.inOpp.at3.Thatrelationship,<br />

A & S alleges, is best illustrated by the<br />

$50,000 loan, made without an underlying written<br />

contract.Theloan,however,concernedanentirely<br />

separate aspect <strong>of</strong> the parties' relationship and had<br />

nothing <strong>to</strong> do with the subject matter <strong>of</strong> the 1986<br />

Page 8 <strong>of</strong> 185

<strong>Schottenstein</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Trial</strong><br />

<strong>Brief</strong><br />

721F.Supp.472<br />

(Citeas:721F.Supp.472)<br />

Agreement: Wachner's share <strong>of</strong> the Settlement<br />

Amountandherrelease<strong>of</strong>A&Sfromanyfuture<br />

claims.Asfarasthatsubjectisconcerned,the1986<br />

Agreement remains integrated. Similarly, Wachner'scontinuedinterestinA&S'sdealingswithits<br />

LimitedPartnersdoesnotalterthe<strong>Court</strong>'sanalysis.<br />

For more than a year, she had worked on the proposedBACTransactionwithA&S.SheandAdler<br />

were longtime friends. Her desire <strong>to</strong> “see and understand<br />

any givebacks” and “<strong>to</strong> be a part <strong>of</strong> it,”<br />

WachnerDep.at144,isnotsufficient<strong>to</strong>changethe<br />

<strong>Court</strong>'sconclusionthatthe1986Agreementwasintegrated.<br />

2.WhethertheAgreementwasCollateral:<br />

[5][6]Undercertaincircumstances,parolevidencemaybeadmittedevenifanagreementisintegrated.<br />

First, parol evidence may come in if the allegedagreementiscollateral,thatis,“onewhichis‘separate,independentandcomplete...althoughrelating<br />

<strong>to</strong> the same object.’ ” Lee v. Joseph E.<br />

Seagram & Sons, Inc., 413 F.Supp. at 701; aff'd<br />

552F.2d447(2dCir.1977).Onlywherethreeconditions<br />

are met will the <strong>Court</strong> allow evidence in<br />

support <strong>of</strong> an allegedly collateral agreement. Id.<br />

The New York rule in this area was established<br />

earlyonintheleadingcase<strong>of</strong>Mitchillv.Lath,247<br />

N.Y.377,160N.E.646(1928):<br />

[B]eforesuchanoralagreementasthepresentis<br />

received<strong>to</strong>varythewrittencontractatleastthree<br />

conditionsmustexist,(1)theagreementmustin<br />

form be a collateral one; (2) it must not contradict<br />

express or implied provisions <strong>of</strong> the written<br />

contract;(3)itmustbeonethatpartieswouldnot<br />

ordinarily be expected <strong>to</strong> embody in the writing<br />

... [The oral agreement] must not be so clearly<br />

connectedwiththeprincipaltransactionas<strong>to</strong>be<br />

partandparcel<strong>of</strong>it.<br />

247N.Y.at380-81,160N.E.646.<br />

[7]Theallegedoralunderstandingatissuehere<br />

isnotcollateral.Asnotedabove,itis“partandparcel”<strong>of</strong>theunderlyingagreement,preciselythesor<strong>to</strong>fprovision“thepartieswouldordinarilybeexpec-<br />

©2012ThomsonReuters.NoClaim<strong>to</strong>Orig.USGov.Works.<br />

Page8<br />

ted <strong>to</strong> embody in the writing.” See discussion,<br />

supra.Moreover,A&S'sexplanations<strong>of</strong>theprovision's<br />

absence are unconvincing. First, Adler's<br />

friendshipwithWachnerdidnotpreventhimfrom<br />

having her execute at least three highly specific<br />

contracts. His friendship did not prevent him from<br />

explaining with precise formulae Wachner's exact<br />

share <strong>of</strong> any future taxes that might be levied<br />

againsttheSettlementAmount.A&S'srelianceon<br />

*479 Lee v. Joseph E. Seagram & Sons, 552 F.2d<br />

447 (2d Cir.1977), is misplaced. In that case, the<br />

Second <strong>Circuit</strong> allowed parol evidence in part because“therewasacloserelationship<strong>of</strong>confidence<br />

andfriendhsipover[thirty]yearsbetweentwoold<br />

men[whoweretheparties<strong>to</strong>theallegedagreement<br />

at issue]”. Id. at 452 (emphasis added). The <strong>Court</strong><br />

doesnotbelievethatsuchauniqueandlongstandingrelationshipiscurrentlybeforeit.Moreover,the<br />

friendshipbetweenthepartiesinLeewasonlyone<br />

<strong>of</strong>severalfac<strong>to</strong>rsthecourtreliedoninitsdetermination<br />

<strong>to</strong> accept parol evidence. Id. And, as noted<br />

above, Adler's friendship with Wachner represents<br />

only half the s<strong>to</strong>ry; Wachner's relationship with<br />

Shaykin was, by the parties' own testimony, not<br />

friendly.<br />

Adler'sfear<strong>of</strong>theLimitedPartnersissimilarly<br />

unconvincing. Simply put, he and Wachner could<br />

haveagreedthatshewouldreturnaportion<strong>of</strong>her<br />

distribution without explicitly alerting the Limited<br />

Partners <strong>to</strong> this possibility. For instance, the 1986<br />

AgreementcouldhaveprovidedthatWachner'sdistributionwas“contingen<strong>to</strong>naplanneddistribution<br />

<strong>of</strong>$4.6million<strong>to</strong>theLimitedPartners,”oritcould<br />

have included a boilerplate conclusion that “this<br />

Agreement remains subject <strong>to</strong> a final accounting<br />

pursuant <strong>to</strong> the formulae contained in the 1985<br />

Agreement.”Itdidneither.<br />

A&S'srelianceonHicksv.Bush,10N.Y.2d<br />

488, 225 N.Y.S.2d 34, 180 N.E.2d 425 (1962) is<br />

also unpersuasive. In that case, the oral agreement<br />

inquestionwas“thesor<strong>to</strong>fconditionwhichparties<br />

wouldnotbeinclined<strong>to</strong>incorporatein<strong>to</strong>awritten<br />

agreementintendedforpublicconsumption.”Id.at<br />

Page 9 <strong>of</strong> 185

<strong>Schottenstein</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Trial</strong><br />

<strong>Brief</strong><br />

721F.Supp.472<br />

(Citeas:721F.Supp.472)<br />

493, 225 N.Y.S.2d 34, 180 N.E.2d 425. The 1986<br />

Agreementwasnotintendedfor“publicconsumption.”AndevenifitwereseenbyA&S'sLimited<br />

Partners, there is no reason why it would have <strong>to</strong><br />

undermine A & S's interests. As noted above, it<br />

wouldnothavebeendifficult<strong>to</strong>draftacontractual<br />

clause that at once both guaranteed that Wachner<br />

wouldreturnaportion<strong>of</strong>herpaymentintheevent<br />

the Limited Partners received a greater share, and<br />

explainedthatA&SitselfdidnotbelievetheLimitedPartnerswereentitled<strong>to</strong>agreatershare.<br />

Finally,inthe<strong>Court</strong>'sjudgment,theallegedoral<br />

understanding squarely contradicts the unambiguousterms<strong>of</strong>the1986Agreement.<br />

3.Ambiguity:<br />

[8] Even if an agreement is integrated, parol<br />

evidencemaybeadmittediftheunderlyingcontract<br />

is ambiguous. See, e.g., Ralli v. Tavern on the<br />

Green, 566 F.Supp. 329, 331 (S.D.N.Y.1983)<br />

(“Wherethelanguageemployedinacontractisambiguousorequivocal,thepartiesmaysubmitparol<br />

evidence concerning the facts and surrounding the<br />

making <strong>of</strong> the agreement in order <strong>to</strong> demonstrate<br />

theinten<strong>to</strong>ftheparties”);ScheringCorp.v.Home<br />

InsuranceCo.,712F.2d4,9(2dCir.1983)(“where<br />

contract language is susceptible <strong>of</strong> at least two<br />

fairlyreasonablemeanings,thepartieshavearight<br />

<strong>to</strong> present extrinsic evidence <strong>of</strong> their intent at the<br />

time<strong>of</strong>contracting”).Asbothsidesagree,thetraditionalviewisthatthesearchforambiguitymustbe<br />

conducted within the four corners <strong>of</strong> the writing.<br />

See,e.g.,WesternUnionTelegraphCo.v.AmericanCommunicationsAss'n,299N.Y.177,86N.E.2d<br />

162(1949).<br />

Under this analysis, it is self-evident that the<br />

1986 Agreement is not ambiguous. There are no<br />

wordsorphrasesthatappear“susceptible<strong>of</strong>atleast<br />

two fairly reasonable meanings.” As discussed at<br />

length above, the fact that the agreement contains<br />

onlyaone-wayreleasedoesnotcreateanyambiguity.<br />

4.Fraud:<br />

[9][10][11]“Theparolevidencerulehasnoapplicationinasuitbrought<strong>to</strong>rescindacontrac<strong>to</strong>n<br />

the ground <strong>of</strong> fraud.” Sabo v. Delman, 3 N.Y.2d<br />

155,161,164N.Y.S.2d714,717,143N.E.2d906,<br />

908(1957)(emphasisinoriginal).UnderNewYork<br />

law, “<strong>to</strong> plead a prima facie case <strong>of</strong> fraud the<br />

plaintiffmustallegerepresentation<strong>of</strong>amaterialexisting<br />

fact, falsity, scienter, deception and injury.”<br />

*480Lanzi v. Brooks, 54 A.D.2d 1057, 1058, 388<br />

N.Y.S.2d 946, 947 (3d Dep't 1976), aff'd, 43<br />

N.Y.2d 778, 402 N.Y.S.2d 384, 373 N.E.2d 278<br />

(1977);Renov.Bull,226N.Y.546,550,124N.E.<br />

144 (1919). “In short, a contractual promise made<br />

with the undisclosed intention not <strong>to</strong> perform it<br />

constitutes fraud and, despite the so-called merger<br />

clause,theplaintiffisfree<strong>to</strong>provethathewasinduced<br />

by false and fraudulent misrepresentations<br />

...”Sabo,supra,3N.Y.2dat162,164N.Y.S.2dat<br />

718,143N.E.2dat909.<br />

However, Judge Weinfeld has explained what<br />

thefraudexceptionisnotintended<strong>to</strong>reach:<br />

©2012ThomsonReuters.NoClaim<strong>to</strong>Orig.USGov.Works.<br />

Page9<br />

Althoughpro<strong>of</strong><strong>of</strong>fraudcanvitiateanagreement,<br />

suchpro<strong>of</strong>mayonlybe<strong>of</strong>fered<strong>to</strong>show‘theintention<strong>of</strong>thepartiesthattheentirecontractwas<strong>to</strong>beanullity,notasheretha<strong>to</strong>nlycertainprovisions<strong>of</strong>theagreementwere<strong>to</strong>beenforced.’Heretheplaintiffisnotclaimingthatnoagreementexisted<br />

... [H]e is not seeking rescission, but enforcement<br />

<strong>of</strong> the contract, albeit upon terms ...<br />

markedly different from those in the writing ...<br />

Heretheplaintiffseeksmaterially<strong>to</strong>alter,byintroducing<br />

prior parol evidence, a single unambiguouslyexpresseditem-theterms<strong>of</strong>compensation-inacomprehensivecontractthatincludes[a<br />

mergerclause].Toallowhim<strong>to</strong>dosowouldbe<br />

<strong>to</strong>evisceratetheparolevidencerule...<br />

Meinrath,supraat460-61(emphasisinoriginal;footnotesomitted).InMeinrath,JudgeWeinfeldthusrejected“plaintiff'sattempt<strong>to</strong>avoidthestrictures<strong>of</strong>theparolevidencerulebyallegingfraudulentinducement.”Id.<br />

Judge Weinfeld's opinion in Meinrath is dis-<br />

Page 10 <strong>of</strong> 185

<strong>Schottenstein</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Trial</strong><br />

<strong>Brief</strong><br />

721F.Supp.472<br />

(Citeas:721F.Supp.472)<br />

positivehere.The<strong>Court</strong>willnotallowtheplaintiff<br />

<strong>to</strong> introduce parol evidence <strong>to</strong> alter the unambiguousterms<strong>of</strong>anintegratedagreement.<br />

FN4<br />

FN4. Moreover, it appears that this claim<br />

failsforapleadingdefect.Plaintiffdidnot<br />

amend its Complaint <strong>to</strong> assert a claim <strong>of</strong><br />

fraud.Indeed,thecircumstancessurroundingfraudmustbepleadedwithparticularity.<br />

See Rule 9(b), Federal Rules <strong>of</strong> Civil<br />

Procedure.<br />

B.TheRemainingCounts:<br />

A & S's action sounds primarily in contract.<br />

However, it has also alleged three additional<br />

counts: unjust enrichment, conversion and money<br />

hadandreceived.Each<strong>of</strong>theadditionalcountsrepresents<br />

an attempt <strong>to</strong> get through the back door a<br />

claimthis<strong>Court</strong>willnotallowthroughthefront.<br />

1.UnjustEnrichmentandQuasiContract:<br />

[12]The<strong>Court</strong>'sdecisionontheseissuesturns<br />

on whether or not it concludes as a matter <strong>of</strong> law<br />

thatthe1986Agreementdefinedfullytherelationship<br />

between the parties as far as the Settlement<br />

Amount was concerned. Since the <strong>Court</strong> has so<br />

found, a recent New York <strong>Court</strong> <strong>of</strong> Appeals case<br />

controls the present dispute. In Clark-Fitzpatrick<br />

Inc.v.LongIslandRailRoadCo.,70N.Y.2d382,<br />

521N.Y.S.2d653,516N.E.2d190(1987),aunanimouscourtexplainedthat“theexistence<strong>of</strong>avalidandenforceablewrittencontractgoverningaparticularsubjectmatterordinarilyprecludesrecoveryin<br />

quasi contract for events arising out <strong>of</strong> the same<br />

subjectmatter.”Thecourtcontinued:<br />

A‘quasicontract’onlyappliesintheabsence<strong>of</strong><br />

anexpressagreement,andisnotreallyacontract<br />

atall,butratheralegalobligationimposedinorder<br />

<strong>to</strong> prevent a party's unjust enrichment ...'<br />

<strong>Brief</strong>ly stated, a quasi-contractual relationship is<br />

one imposed by law where there has been no<br />

agreement or expression <strong>of</strong> assent, by word or<br />

act,onthepar<strong>to</strong>feitherpartyinvolved.Itisimpermissible,however,<strong>to</strong>seekdamagesinanaction<br />

sounding in quasi contract where the suing<br />

©2012ThomsonReuters.NoClaim<strong>to</strong>Orig.USGov.Works.<br />

Page10<br />

party has fully performed on a valid written<br />

agreement,theexistence<strong>of</strong>whichisundisputed,<br />

andthescope<strong>of</strong>whichclearlycoversthedispute<br />

betweentheparties.<br />

Clark-Fitzpatrick, supra at 388-89, 521<br />

N.Y.S.2d 653, 516 N.E.2d 190 (citations omitted;<br />

emphasisinoriginal).<br />

2.Conversion:<br />

The <strong>Court</strong> has determined as a matter <strong>of</strong> law<br />

thatWachnerhadanabsoluterightbasedonanintegrated<br />

agreement <strong>to</strong> the *481 $2.785 million she<br />

received. Thus, no claim for conversion will lie.<br />

See, e.g., Hinkle Iron Co. v. Kohn, 184 A.D. 181,<br />

183-84, 171 N.Y.S. 537 (1st Dep't), reversed on<br />

othergrounds,229N.Y.179,128N.E.113(1918)<br />

Cf.Clark-Fitzpatrick,Inc.,supra.Theresultwould<br />

benodifferenteveniftheoralunderstandingwere<br />

allowed <strong>to</strong> vary the unambiguous terms <strong>of</strong> the integrated<br />

agreement. See Hinkle Iron, supra at<br />

183-4,171N.Y.S.537(“Thefailure<strong>to</strong>payi<strong>to</strong>ver<br />

was simply a breach <strong>of</strong> contract, and the plaintiff<br />

cannot,bychangingtheform<strong>of</strong>theaction,change<br />

thenature<strong>of</strong>thedefendant'sobligationandconvert<br />

in<strong>to</strong>a<strong>to</strong>rtthatwhichthelawdeemsasimplebreach<br />

<strong>of</strong>anagreement...”).<br />

3.MoneyHadandReceived:<br />

The <strong>Court</strong> finds no colorable grounds for this<br />

equitableremedy.<br />

In an action for money had and received, the<br />

[movant]‘mustshowthatitisagainstgoodconsciencefor[hisadversary]<strong>to</strong>keepthemoney.’...[Suchanaction]isfoundeduponequitableprinciplesaimedatachievingjustice.<br />

Federal Insurance Co. v. Groveland State<br />

Bank, 37 N.Y.2d 252, 258, 372 N.Y.S.2d 18, 21,<br />

333N.E.2d334,336(1975).Nomaterialtriableissue<br />

exists on this score. The alleged oral understanding<br />

between Adler and Wachner, which the<br />

<strong>Court</strong> assumes existed, does not dictate a contrary<br />

result.Thepartiesaresophisticatedbusinesspeople<br />

whose relationship was governed by detailed con-<br />

Page 11 <strong>of</strong> 185

<strong>Schottenstein</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Trial</strong><br />

<strong>Brief</strong><br />

721F.Supp.472<br />

(Citeas:721F.Supp.472)<br />

tracts.Infact,equitydictatesthatthepartieshonor<br />

theirfreelynegotiatedandintegratedagreemen<strong>to</strong>f<br />

December5,1986.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

For the reasons set forth above, defendant's<br />

motionforsummaryjudgmentisgranted.<br />

SOORDERED.<br />

S.D.N.Y.,1988.<br />

Adler&Shaykinv.Wachner<br />

721F.Supp.472<br />

ENDOFDOCUMENT<br />

©2012ThomsonReuters.NoClaim<strong>to</strong>Orig.USGov.Works.<br />

Page 12 <strong>of</strong> 185<br />

Page11

<strong>Schottenstein</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Trial</strong><br />

<strong>Brief</strong><br />

70A.D.3d423 Page1<br />

70A.D.3d423<br />

(Citeas:70A.D.3d423,894N.Y.S.2d47)<br />

AmcanHoldings,Inc.vCanadianImperialBank<strong>of</strong><br />

Commerce<br />

70A.D.3d423,894N.Y.S.2d47<br />

NY,2010.<br />

70 A.D.3d 423, 894 N.Y.S.2d 47, 2010 WL<br />

375162,2010N.Y.SlipOp.00786<br />

AmcanHoldings,Inc.,etal.,Appellants-Respondents<br />

v<br />

CanadianImperialBank<strong>of</strong>Commerce,Respondent-Appellant,etal.,Defendants.Supreme<strong>Court</strong>,AppellateDivision,FirstDepartment,NewYork<br />

February4,2010<br />

CITETITLEAS:AmcanHoldings,Inc.vCanadian<br />

ImperialBank<strong>of</strong>Commerce<br />

Parties<br />

Standing<br />

*424<br />

Contracts<br />

Formation<strong>of</strong>Contract<br />

HEADNOTES<br />

Actionforbreach<strong>of</strong>contractbasedondefendants'<br />

failure<strong>to</strong>closeloanwasdismissedbecausecontract<br />

was never formed; parties negotiated “Draft Summary<br />

<strong>of</strong> Terms and Conditions” (draft summary)<br />

outlining proposed terms <strong>of</strong> two credit lines and<br />

“Summary <strong>of</strong> Terms and Conditions” (summary),<br />

both <strong>of</strong> which clearly stated that credit facilities<br />

would “only be established upon completion <strong>of</strong><br />

definitiveloandocumentation”containingno<strong>to</strong>nly<br />

terms and conditions in draft summary and summarybutalsosuch“othertermsandconditions...<br />

as [bank] may reasonable require”; although summary<br />

was detailed in its terms, it was clearly dependen<strong>to</strong>nfuturedefinitivecreditagreement;atno<br />

point did parties explicitly state that they intended<br />

©2012ThomsonReuters.NoClaim<strong>to</strong>Orig.USGov.Works.<br />

<strong>to</strong>beboundbysummarypendingfinalcreditagreement,nordidtheywaivefinalization<strong>of</strong>suchagreement.<br />

Scolaro, Shulman, Cohen, Fetter & Burstein, P.C.,<br />

Syracuse (Chaim J. Jaffe <strong>of</strong> counsel), for appellants-respondents.<br />

Skadden,Arps,Slate,Meagher&FlomLLP,New<br />

York(ScottD.Mus<strong>of</strong>f<strong>of</strong>counsel),forrespondentappellant.<br />

Order,Supreme<strong>Court</strong>,NewYorkCounty(HelenE.<br />

Freedman, J.), entered June 17, 2008, which granted<br />

defendants' motion <strong>to</strong> dismiss the complaint <strong>to</strong><br />

theexten<strong>to</strong>fdismissingallcauses<strong>of</strong>actionagainst<br />

defendants Canadian Imperial Holdings, CIBC<br />

World Markets, and CIBC, Inc., and the cause <strong>of</strong><br />

action for breach <strong>of</strong> the implied covenant <strong>of</strong> good<br />

faith and fair dealing against defendant Canadian<br />

Imperial Bank <strong>of</strong> Commerce (CIBC), unanimously<br />

modified, on the law, the remaining causes <strong>of</strong> action<br />

against CIBC dismissed, and otherwise affirmed,withcostsagainstplaintiffs.<br />

Plaintiff companies are all controlled by one<br />

Richard Gray, who, in 2001, approached CIBC <strong>to</strong><br />

obtain financing for the acquisition <strong>of</strong> a company<br />

called CWD Windows Division (CWD Division),<br />

aswellasrefinancingfortheexistingdeb<strong>to</strong>fAmcan<br />

and another company owned by Amcan, B.F.<br />

Rich Co. (BF Rich). Gray also sought funding for<br />

thecontinuingoperations<strong>of</strong>CWDDivisionandBF<br />

Rich.Morespecifically,plaintiffssoughtacommitment<br />

from CIBC <strong>to</strong> furnish two separate lines <strong>of</strong><br />

credit:(1)arevolvingcreditline<strong>to</strong>provideworkingcapital,and(2)anonrevolvingtermloan.<br />

Thepartiesnegotiateda“DraftSummary<strong>of</strong>Terms<br />

andConditions”(draftsummary),outliningtheproposedterms<strong>of</strong>thetwocreditlines.Afteradditional<br />

negotiations,thepartiesexecutedawritingentitled<br />

“Summary <strong>of</strong> Terms and Conditions” (summary).<br />

Bothdocumentscontainedahighlightedboxatthe<br />

<strong>to</strong>p <strong>of</strong> the first page with the following language:<br />

Page 13 <strong>of</strong> 185

<strong>Schottenstein</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Trial</strong><br />

<strong>Brief</strong><br />

70A.D.3d423 Page2<br />

70A.D.3d423<br />

(Citeas:70A.D.3d423,894N.Y.S.2d47)<br />

“TheCreditFacilitieswillonlybeestablishedupon<br />

completion <strong>of</strong> definitive loan documentation, including<br />

a credit agreement . . . which will contain<br />

thetermsandconditionsse<strong>to</strong>utinthisSummaryin<br />

addition<strong>to</strong>suchotherrepresentations...andother<br />

termsandconditions...asCIBCmayreasonably<br />

require.”<br />

The summary itself contained specifics on a number<strong>of</strong>items,including,interalia,detaileddescriptions<strong>of</strong>thecreditlines,theamoun<strong>to</strong>ffunding<strong>to</strong>be<br />

provided under each, amortization and interest<br />

rates, fees, security, a proposed closing date and<br />

definitions<strong>of</strong>key**2terms.TheborrowerwaslistedasCWDDivisionandBFRich.*425<br />

Under the subheading “Fees,” the summary<br />

provided for a $500,000 fee <strong>to</strong> CIBC, payable as<br />

follows:$50,000payableonacceptance<strong>of</strong>thedraft<br />

summary, $150,000 payable upon acceptance <strong>of</strong><br />

this committed <strong>of</strong>fer and $300,000 payable upon<br />

theclosing<strong>of</strong>thistransaction.Itisundisputedthat<br />

plaintiffs paid the first two installments, which<br />

werenotrefundedbydefendantswhenthedealwas<br />

terminated.<br />

Underthesubheading“ConditionsPrecedent”were<br />

included what was “[u]sual and cus<strong>to</strong>mary for<br />

transactions <strong>of</strong> this type,” such as—for “Initial<br />

Funding,” the “[e]xecution and delivery <strong>of</strong> an acceptable<br />

formal loan agreement and security . . .<br />

documentation,whichembodiesthetermsandconditionscontainedinthisSummary.”<br />

Although there is a dispute over what happened<br />

next,itappearsthatprior<strong>to</strong>theexecution<strong>of</strong>thefinal<br />

loan documents and credit agreement, CIBC<br />

discovered Gray had failed <strong>to</strong> disclose that certain<br />

entities he controlled, including Amcan, were subject<strong>to</strong>apreliminaryinjunctionissuedbyNewYork<br />

CountySupremeCour<strong>to</strong>nOc<strong>to</strong>ber21,1996,which<br />

prohibited Amcan from assigning BF Rich shares<br />

as security for the loan, a condition precedent <strong>to</strong><br />

closing the deal. Additionally, defendants claim<br />

plaintiffsfailed<strong>to</strong>disclosethatGrayhadbeenheld<br />

incontemptforviolatingtheinjunction,whichcon-<br />

©2012ThomsonReuters.NoClaim<strong>to</strong>Orig.USGov.Works.<br />

temptwasupheldtwiceonappeal.Plaintiffsargue<br />

that defendants were aware <strong>of</strong> Gray's prior actions<br />

but proceeded with the deal in spite <strong>of</strong> that knowledge.<br />

CIBC broke <strong>of</strong>f negotiations and the deal<br />

wasneverconsummated.<br />

Six years later, plaintiffs commenced this action,<br />

asserting causes <strong>of</strong> action for breach <strong>of</strong> contract<br />

based on defendants' failure <strong>to</strong> close the loan,<br />

breach <strong>of</strong> defendants' obligation <strong>of</strong> good faith and<br />

fair dealing, and fraud. Defendants moved <strong>to</strong> dismissthecomplaintpursuant<strong>to</strong>CPLR3211(a)(1)<br />

and (7). Defendants argued that the summary was<br />

not a binding agreement, but a mere agreement <strong>to</strong><br />

agree,andthattheydidnotactarbitrarilyinbreaking<strong>of</strong>fnegotiationsafterlearningaboutthepreliminary<br />

injunction and contempt orders. Defendants<br />

further argued that assuming arguendo that the<br />

summarywasabindingagreement,plaintiffsfailed<br />

<strong>to</strong> state a cause <strong>of</strong> action because they did not<br />

identifyprovisions<strong>of</strong>thesummarydefendantshad<br />

allegedlybreached.Finally,defendantsarguedthat<br />

Chariot Management lacked standing <strong>to</strong> sue, as it<br />

wasneitheraparty<strong>to</strong>,norathird-partybeneficiary<br />

<strong>of</strong>,thesummary.<br />

The motion was granted <strong>to</strong> dismiss against all defendants<br />

other than CIBC, holding that they were<br />

not parties <strong>to</strong> any agreement. The court also dismissed<br />

plaintiffs' cause <strong>of</strong> action *426 against<br />

CIBC for breach <strong>of</strong> good faith and fair dealing,<br />

holding this claim duplicative <strong>of</strong> the breach<strong>of</strong>-contract<br />

cause <strong>of</strong> action. In addition, it denied<br />

the motion <strong>to</strong> dismiss the cause <strong>of</strong> action against<br />

CIBC for breach <strong>of</strong> contract, finding that the circumstances<br />

presented at this preliminary stage <strong>of</strong><br />

theproceedingsdidnotpermitadeterminationas<strong>to</strong><br />

whether the summary was a binding agreement or<br />

merely an agreement<strong>to</strong> agree. Thecourtalso held<br />

thattheportion<strong>of</strong>themotion<strong>to</strong>dismiss,forlack<strong>of</strong><br />

standing, plaintiff Chariot Management's cause <strong>of</strong><br />

actionforbreach<strong>of</strong>contractwaspremature.<br />

The claim that defendants breached the implied<br />

covenant <strong>of</strong> good faith and fair dealing was properly<br />

dismissed as duplicative <strong>of</strong> the breach-<br />

Page 14 <strong>of</strong> 185

<strong>Schottenstein</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Trial</strong><br />

<strong>Brief</strong><br />

70A.D.3d423 Page3<br />

70A.D.3d423<br />

(Citeas:70A.D.3d423,894N.Y.S.2d47)<br />

<strong>of</strong>-contract claim, as both claims arise from the<br />

samefacts(LoganAdvisors,LLCvPatriarchPartners,LLC,63AD3d440,443[2009])andseekthe<br />

identicaldamagesforeachallegedbreach(seeDeer<br />

Park Enters., LLC v Ail Sys., Inc., 57 AD3d 711,<br />

712[2008]).<br />

The causes <strong>of</strong> action asserted by Chariot Management<br />

against all defendants should have been dismissed<br />

for lack <strong>of</strong> standing. The documents belie<br />

plaintiffs' allegation that Chariot **3 Management—which<br />

was not identified as a “Borrower,”<br />

orlistedasasigna<strong>to</strong>ry<strong>to</strong>eitherthesummaryorthe<br />

draftcreditagreement—wasanintendedthird-party<br />

beneficiary<strong>of</strong>thesummary(seeLaSalleNatl.Bank<br />

vErnst&Young,285AD2d101,108-109[2001]).<br />

“In determining whether a contract exists, the inquiry<br />

centers upon the parties' intent <strong>to</strong> be bound,<br />

i.e.,whethertherewasa‘meeting<strong>of</strong>theminds'regarding<br />

the material terms <strong>of</strong> the transaction” (<br />

Central Fed. Sav. v National Westminster Bank,<br />

U.S.A., 176 AD2d 131, 132 [1991]). Generally,<br />

wherethepartiesanticipatethatasignedwritingis<br />

required,thereisnocontractuntiloneisdelivered(<br />

see Scheck v Francis, 26 NY2d 466, 470-471<br />

[1970]).<br />

Here, both the draft summary and summary documentsclearlystatethecreditfacilities“willonlybeestablisheduponcompletion<strong>of</strong>definitiveloandocumentation,”<br />

which would contain not only the<br />

terms and conditions in those documents but also<br />

such“othertermsandconditions...asCIBCmay<br />

reasonably require.” Although the summary was<br />

detailedinitsterms,itwasclearlydependen<strong>to</strong>na<br />

future definitive agreement, including a credit<br />

agreement. At no point did the parties explicitly<br />

state that they intended <strong>to</strong> be bound by the summary<br />

pending the final credit agreement, nor did<br />

they waive the finalization <strong>of</strong> such agreement (see<br />

Prospect St. Ventures I, LLC v Eclipsys Solutions<br />

Corp.,23AD3d213[2005];seealsoHollingerDigitalvLookSmart,Ltd.,267AD2d77[1999]).*427<br />

Thepartiesdisagreeonwhetherthedraftsummary<br />

©2012ThomsonReuters.NoClaim<strong>to</strong>Orig.USGov.Works.<br />

andsummaryfallin<strong>to</strong>atypeI(fullynegotiated)or<br />

type II (terms still <strong>to</strong> be negotiated) preliminary<br />

agreement, commonly used in federal cases addressingtheissue<strong>of</strong>whetheraparticulardocument<br />

is an enforceable agreement or merely an agreement<strong>to</strong>agree(seeTeachersIns.&AnnuityAssn.<strong>of</strong><br />

Am. v Tribune Co., 670 F Supp 491, 498 [SD NY<br />

1987]).However,ourCour<strong>to</strong>fAppealsrecentlyrejected<br />

the federal type I/type II classifications as<br />

<strong>to</strong>o rigid, holding that in determining whether the<br />

documentinagivencaseisanenforceablecontract<br />

or an agreement <strong>to</strong> agree, the question should be<br />

askedinterms<strong>of</strong>“whethertheagreementcontemplatedthenegotiation<strong>of</strong>lateragreementsandiftheconsummation<strong>of</strong>thoseagreementswasaprecondition<br />

<strong>to</strong> a party's performance” (IDT Corp. v Tyco<br />

Group,S.A.R.L.,13NY3d209,213n2[2009]).<br />

Here,thesummarymadeanumber<strong>of</strong>references<strong>to</strong><br />

future definitive documentation, starting with the<br />

boxonpageone<strong>of</strong>thesummary.Thefactthatthe<br />

summary was extensive and contained specific information<br />

regarding many <strong>of</strong> the terms <strong>to</strong> be contained<br />

in the ultimate loan documents and credit<br />

agreementsdoesnotchangethefactthatdefendants<br />

clearly expressed an intent not <strong>to</strong> be bound until<br />

thosedocumentswereactuallyexecuted.Asaresult,<br />

the motion <strong>to</strong> dismiss the complaint should<br />

have been granted in its entirety with respect <strong>to</strong><br />

CIBC.**4<br />

Basedontheforegoing,thereisnoneed<strong>to</strong>address<br />

theremainingissuesraisedbythepartiesontheappeal<br />

and cross appeal. Concur—Mazzarelli, J.P.,<br />

Sweeny, Catterson, Acosta and Abdus-Salaam, JJ.<br />

[Prior <strong>Case</strong> His<strong>to</strong>ry: 20 Misc 3d 1104(A), 2008<br />

NYSlipOp51218(U).]<br />

Copr.(C)2012,Secretary<strong>of</strong>State,State<strong>of</strong>New<br />

York<br />

NY,2010.<br />

AmcanHoldings,Inc.vCanadianImperialBank<strong>of</strong><br />

Commerce<br />

70 A.D.3d 423, 894 N.Y.S.2d 476022010 WL<br />

3751629992010 N.Y. Slip Op. 007864603, 894<br />

N.Y.S.2d 476022010 WL 3751629992010 N.Y.<br />

Page 15 <strong>of</strong> 185

<strong>Schottenstein</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Trial</strong><br />

<strong>Brief</strong><br />

70A.D.3d423 Page4<br />

70A.D.3d423<br />

(Citeas:70A.D.3d423,894N.Y.S.2d47)<br />

SlipOp.007864603,894N.Y.S.2d476022010WL<br />

3751629992010N.Y.SlipOp.007864603<br />

ENDOFDOCUMENT<br />

©2012ThomsonReuters.NoClaim<strong>to</strong>Orig.USGov.Works.<br />

Page 16 <strong>of</strong> 185

<strong>Schottenstein</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Trial</strong><br />

<strong>Brief</strong><br />

33A.D.3d639,821N.Y.S.2d900,2006N.Y.SlipOp.07304<br />

(Citeas:33A.D.3d639,821N.Y.S.2d900)<br />

Supreme<strong>Court</strong>,AppellateDivision,SecondDepartment,NewYork.<br />

ATLASREFRIGERATION–AIRCONDITION-<br />

ING,INC.,respondent,<br />

v.<br />

Salva<strong>to</strong>reLOPINTO,Jr.,appellant.<br />

Oct.10,2006.<br />

Goldberg Rimberg & Friedlander, PLLC, New<br />

York,N.Y.(IsraelGoldberg<strong>of</strong>counsel)forappellant.<br />

Jaffe, Ross & Light, LLP, New York, N.Y. (EdwardJaffeandRobertA.Bruno<strong>of</strong>counsel),forrespondent.<br />

*639Inanaction<strong>to</strong>forecloseamechanic'slien,<strong>to</strong>recoverdamagesforbreach<strong>of</strong>contract,and<br />

<strong>to</strong>recoverinquantummeruitforservicesrendered,<br />

the defendant appeals from a judgment <strong>of</strong> the Supreme<br />

<strong>Court</strong>, Kings County (Jacobson, J.), dated<br />

November 4, 2004, which, after a nonjury trial, is<br />

infavor<strong>of</strong>theplaintiffandagainsthimintheprincipalsum<strong>of</strong>$120,000,withinterestfromJune30,<br />

1997, in the sum <strong>of</strong> $75,150, plus costs and disbursementsinthesum<strong>of</strong>$1,280,forthe<strong>to</strong>talsum<br />

<strong>of</strong>$196,430.<br />

ORDERED that the judgment is modified, on<br />

thelawandintheexercise<strong>of</strong>discretion,bydeleting<br />

from the first decretal paragraph there<strong>of</strong> the<br />

words “with interest from June 30, 1997, in the<br />

amount <strong>of</strong> $75,150.00” and “making a <strong>to</strong>tal <strong>of</strong><br />

$196,430.00,” and substituting therefor the words<br />

“withinterestfromOc<strong>to</strong>ber15,1999,”assomodified,thejudgmentisaffirmed,withcosts<strong>to</strong>therespondent,andthematterisremitted*640<strong>to</strong>theSupreme<strong>Court</strong>,KingsCounty,fortherecalculation<strong>of</strong><br />

prejudgment interest in accordance herewith and<br />

for the entry <strong>of</strong> an appropriate amended judgment<br />

accordingly.<br />

©2012ThomsonReuters.NoClaim<strong>to</strong>Orig.USGov.Works.<br />

Page1<br />

Inorder<strong>to</strong>establishaclaiminquantummeruit,<br />

aclaimantmustestablish(1)theperformance<strong>of</strong>the<br />

servicesingoodfaith,(2)theacceptance<strong>of</strong>theservices<br />

by the person <strong>to</strong> whom they were rendered,<br />

(3) an expectation <strong>of</strong> compensation therefor, and<br />

(4)thereasonablevalue<strong>of</strong>theservices(seeRossv.<br />

DeLorenzo, 28 A.D.3d 631, 813 N.Y.S.2d 756;<br />

Tesserv.AllboroEquip.Co.,302A.D.2d589,590,<br />

756N.Y.S.2d253;Matter<strong>of</strong>Alu,302A.D.2d520,<br />

755N.Y.S.2d289;Geraldiv.Melamid,212A.D.2d<br />

575, 576, 622 N.Y.S.2d 742; **901Moors v. Hall,<br />

143A.D.2d336,337–338,532N.Y.S.2d412;Umscheid<br />

v. Simnacher, 106 A.D.2d 380, 382–383,<br />

482 N.Y.S.2d 295). Here, the plaintiff adduced<br />

evidenceattrial<strong>to</strong>establishallfourelements.<br />

The Supreme <strong>Court</strong> providently exercised its<br />

discretion in granting the plaintiff's application,<br />

madeafteritrested,<strong>to</strong>reopenitsprimafaciecase<br />

<strong>to</strong>presentspecificevidence(seeCPLR4011;Morgan<br />

v. Pascal, 274 A.D.2d 561, 712 N.Y.S.2d 48;<br />

Lagana v. French, 145 A.D.2d 541, 542, 536<br />

N.Y.S.2d95).<br />

TheSupreme<strong>Court</strong>furtherproperlydismissed<br />

the defendant's counterclaim alleging willful exaggeration<br />

<strong>of</strong> a mechanic's lien. The mechanic's lien<br />

in this case was declared null and void by the Supreme<br />

<strong>Court</strong> because it had not been timely filed<br />