Acculturative Stress, Anxiety, and Depression among Mexican ...

Acculturative Stress, Anxiety, and Depression among Mexican ...

Acculturative Stress, Anxiety, and Depression among Mexican ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

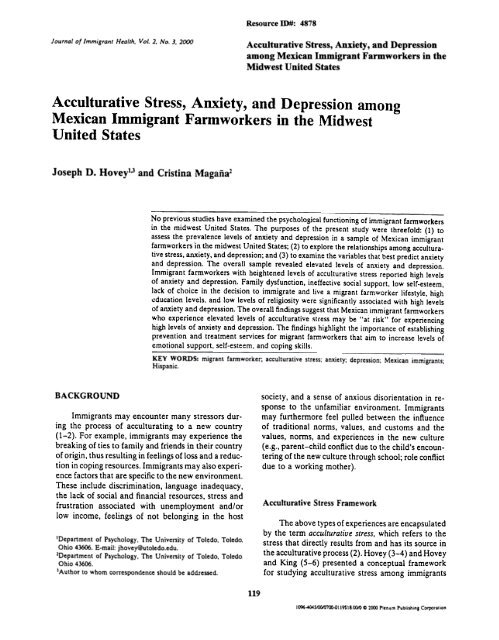

119Resource ID#: 4878Journal of Immigrant Heallh, Vol. 2, No.3, 2000<strong>Acculturative</strong> <strong>Stress</strong>, <strong>Anxiety</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Depression</strong><strong>among</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> Immigrant Farmworkers in theMidwest United States<strong>Acculturative</strong> <strong>Stress</strong>, <strong>Anxiety</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Depression</strong> <strong>among</strong><strong>Mexican</strong> Immigrant Farmworkers in the MidwestUnited StatesJoseph D. Hoveyl.3 <strong>and</strong> Cristina Magaiia2No previous studies have examined the psychological functioning of immigrant farmworkersin the midwest United States. The purposes of the present study were threefold: (1) toassess the prevalence levels of anxiety <strong>and</strong> depression in a sample of <strong>Mexican</strong> immigrantfarmworkers in the midwest United States; (2) to explore the relationships <strong>among</strong> acculturativestress. anxiety. <strong>and</strong> depression; <strong>and</strong> (3) to examine the variables that best predict anxiety<strong>and</strong> depression. The overall sample revealed elevated levels of anxiety <strong>and</strong> depression.Immigrant farmworkers with heightened levels of acculturative stress reported high levelsof anxiety <strong>and</strong> depression. Family dysfunction. ineffective social support, low self-esteem,lack of choice in the decision to immigrate <strong>and</strong> live a migrant farmworker lifestyle. high~ducation levels. <strong>and</strong> low levels of religiosity were significantly associated with high levelsof anxiety <strong>and</strong> depression. The overall findings suggesthat <strong>Mexican</strong> immigrant farmworkerswho experience elevated levels of acculturative 5tress may be "at risk" for experiencinghigh levels of anxiety <strong>and</strong> depression. The findings highlight the importance of establishingprevention <strong>and</strong> treatment services for migrant farm workers that aim to increase levels ofemotional support, self-esteem, <strong>and</strong> coping skills.-KEY WORDS: migrant farmworker; acculturative stress; anxiety; depression; <strong>Mexican</strong> immigrants:Hispanic.BACKGROUNDImmigrants may encounter many stressors duringthe process of acculturating to a new country(1-2). For example. immigrants may experience thebreaking of ties to family <strong>and</strong> friends in their countryof origin, thus resulting in feelings of loss <strong>and</strong> a reductionin coping resources. Immigrants may also experiencefactors that are specific to the new environment.These include discrimination, language inadequacy,the lack of social <strong>and</strong> financial resources, stress <strong>and</strong>frustration associated with unemployment <strong>and</strong>/orlow income, feelings of not belonging in the host'Department of Psychology, The University of Tol~do, Toledo,Ohio 43606. E-mail: jhovey@utoledo.edu.IDepartment of Psychology, The University of Toledo, ToledoOhio 43606.]AuthoT to whom corTespondence should be addressed.society, <strong>and</strong> a sense of anxious disorientation in responseto the unfamiliar environment. Immigrantsmay furthermore feel pulled between the influenceof traditional norms, values, <strong>and</strong> customs <strong>and</strong> thevalues, norms, <strong>and</strong> experiences in the new culture(e.g., parent-child conflict due to the child's encounteringof the new culture through school; role conflictdue to a working mother).<strong>Acculturative</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> FrameworkThe above types of experiences are encapsulatedby the term acculturatiue stress, which refers to thestress that directly results from <strong>and</strong> has its source inthe acculturative process (2). Hovey (3-4) <strong>and</strong> Hovey<strong>and</strong> King (5-6) presented a conceptual frameworkfor studying acculturative stress <strong>among</strong> immigrants1~~S~oo.o! 19118~ C 2(xx) Plcnum Publishinl Co""ralion

no<strong>and</strong> its relationship to psychological functioning.These authors extended Berry's (2, 7-8) acculturativestress model to include possible consequences ofelevated levels of acculturative stress, rather thanfocusing on predictors of acculturative stress as haveother researchers (9-11). The revised framework hastwo components. First, it suggests that acculturatingindividuals experience varying levels of acculturativestress, <strong>and</strong> that high levels of acculturative stress mayresult in significant levels of anxiety <strong>and</strong> depression.In other words, the model suggests that individualswho experience high levels of acculturative stress maybe at risk for the development of anxiety <strong>and</strong> depression.Second, the model identifies the cultural <strong>and</strong>psychological factors that may account for high versuslow levels of anxiety <strong>and</strong> depression. These includesocial support found within the new community;support from immediate <strong>and</strong> extended familysupport networks; socioeconomic status (SES); premigrationvariables, such as adaptive functioning(self-esteem, coping ability), knowledge of the newlanguage <strong>and</strong> culture, <strong>and</strong> control <strong>and</strong> choice in thedecision to immigrate (voluntary vs. involuntary);cognitive attributes, such as expectations for the future(hopeful vs. nonhopeful); religiosity; <strong>and</strong> thenature of the larger society-that is, the degree oftolerance for <strong>and</strong> acceptance of cultural dive~itywithin the new environment. These variables mayserve as predictors of anxiety <strong>and</strong> depression. Acculturatingindividuals with positive expectations for thefuture <strong>and</strong> relatively high levels of social supportmay, for example, experience less depression thanindividuals without the same expectations <strong>and</strong>support.Hovey used the above framework to guide pastresearch that explored the psychological functioningof immigrants. For example, Hovey <strong>and</strong> King (5)explored the relationship <strong>among</strong> acculturative stress,depressive symptoms, <strong>and</strong> suicidal ideation in a sampleof adolescent <strong>Mexican</strong> immigrants. They foundthat acculturative stress was positively associatedwith depression <strong>and</strong> suicidal ideation, <strong>and</strong> that acculturativestress, perceived family dysfunction, <strong>and</strong>nonhopeful "expectations for the future" were significantpredictors of depression <strong>and</strong> suicidal ideation.Hovey (3-4) found the same positive relationship<strong>among</strong> acculturative stress, depression, <strong>and</strong>suicidal ideation in samples of adult <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>and</strong>Central American immigrants. These latter two studiesalso found that family dysfunction, ineffective socialsupport, low levels of religiosity, nonhopeful expectationsfor the future, lack of choice in the decisionHovey <strong>and</strong> Maganato immigrate. <strong>and</strong> low levels of education <strong>and</strong> incomesignificantly predicted high levels of depression <strong>and</strong>suicidal ideation. Hovey's overall findings suggestthat those acculturating individuals experiencing elevatedlevels of acculturative stress are "at risk" forexperiencing critical levels of psychological distress,<strong>and</strong> that buffering variables such as those above mayhelp protect against distress during the acculturativeprocess.Characteristics of Migrant FannworkersThere are approximately 1 million migrantfarm workers in the United States (12-13). Migrantfarmworkers are individuals who annually migratefrom one place to another to earn a living in agriculture.This is in contrast to seasonal farmworkers, wholive in one location during the year. Migrant farmworkersgenerally live in the southern half of theUnited States during the winter <strong>and</strong> migrate northbefore the planting or harvesting seasons. Three migrantstreams have been identified (12.14). The WestCoast stream is primarily compo~ed of <strong>Mexican</strong> immigrantswho return to Mexico or the southwestUnited States after the ha:vest season. The EastCoast stream is primarily composed of Puerto Ricans<strong>and</strong> African-Americans who migrate from Florida.The Midwest stream is primarily composed of <strong>Mexican</strong>migrants who return to Mexico or Texas afterthe agricultural season.Several authors (12-16) have noted the difficul.ties intrinsic to a migrant farmworker lifestyle. Forexample, migrant farm workers are socially marginal.This situation is intensified by the physical isolation,discrimination, <strong>and</strong> limited opportunities experiencedby migrants. Most migrant farm workers earnless than $6,(00 per year, making them one of themost economically deprived groups in the UnitedStates. Farm labor is strenuous. Migrant workers areoften subjected to dangerous working conditions,such as being sprayed with pesticides, <strong>and</strong> thus, notsurprisingly, farm labor has the highest incidence ofworkplace fatalities in the United States. Child laboris cornmon, <strong>and</strong> thus the average migrant worker hasa sixth-grade education. Migrant workers typicallyfind housing in labor camps provided by their employers.However, the housing <strong>and</strong> sanitation are oftensubst<strong>and</strong>ard. For example, one-room homes thatlack water <strong>and</strong> toilet facilities are common, <strong>and</strong> drinkingwater <strong>and</strong> toilet facilities are often not readilyavailable in the fields. Finally, although their health

<strong>Anxiety</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Depression</strong> <strong>among</strong> Immigrant FarmworkersUIconditions are <strong>among</strong> the worst in the United States(average life expectancy: 49 years), migrant farmworkershave very limited access to health care.Given their difficult living conditions, migrantfarmworkers may be at psychological risk, <strong>and</strong> thussusceptible to problems such as anxiety <strong>and</strong> depression.Very little research, however, has explored themental health of migrant farmworkers in theUnited States.Previous Research of Mental Health <strong>among</strong>Migrant FarmworkersVega et al. (17) examined psychological distress<strong>among</strong> 501 <strong>Mexican</strong>-American farmworkers in centralCalifornia. They measured psychological distresswith the Health Opinion Survey (HOS) (18), a measureof general psychopathology. They found thathigh levels of psychological distress were related toreduced health statuses <strong>and</strong> an occurrence of environmentalstressors over the previous year. In addition.they found that middle-age individuals (40-59years) reported elevated levels of psychological distressin comparison to other age groups. Vega et al.conjectured that middle age is an especially high-riskperiod for farmworkers because significant occupational<strong>and</strong> life hazards exist to progressively degradefannworkers' health <strong>and</strong> functional capacities. Accordingto Vega et al.. the severe lifestyle (e.g., highfrequencies of environmental stressors, such as hazardousworking conditions) experienced by <strong>Mexican</strong>-American farm workers places them at extraordinarypsychological risk.Vega et al. (17) is the only study that has examinedpredictors of mental health <strong>among</strong> migrantfannworkers in the United States. However, theirwork was limited. In their analyses, Vega et al. did notseparate migrant farmworkers from seasonal farmworkers.This distinction is important because a numberof authors (12-14) have suggested that, due totheir migratory <strong>and</strong> unstable lifestyle, migrant farmworkersare at greater risk for health problems thanseasonal farmworkers. Second, Vega et al. did notdirectly measure stressors that are specific to thefannworker lifestyle. Level of environmental stresswas based on one question. The participants wereasked whether they experienced a stressful life eventin the previous 12 months, such as the loss of a job,an accident. or the death of a family member orfriend. Finally. as noted, Vega et al. examined psychologicalrisk in a general fashion. Thus the data do notreveal whether the farmworkers are at greater riskfor anxiety or depression. for example.Purpose of Present StudyThe first purpose of the present study is to assessthe prevalence levels of anxiety <strong>and</strong> depression in asample of <strong>Mexican</strong> immigrant farmworkers in themidwest United States. Given the stressors associatedwith both immigration <strong>and</strong> migrant farmwork, it isexpected that the sample will reveal elevated levelsof anxiety <strong>and</strong> depression. The second purpose isto determine the relationships. <strong>among</strong> acculturativestress, anxiety, <strong>and</strong> depression. It is expected thatelevated levels of acculturative stress will be positivelyassociated with high levels of anxiety <strong>and</strong> depression.The third purpose is to determine the bestpredictors of anxiety <strong>and</strong> depression. The predictorvariables explored are acculturative stress, familyfunctioning, social support, self-esteem, religiosity,control <strong>and</strong> choice in the decision to immigrate, control<strong>and</strong> choice in the decision to live as a migrantfarmworker, education, <strong>and</strong> income.METHODParticipants <strong>and</strong> ProcedurePanicipants were 45 <strong>Mexican</strong> migrant farmworkers(20 females, 25 males) in the northwestOhio/southeast Michigan area. The age of the sampleranged from 17 to 65 (M = 33.53, SD = 11.03).Twenty-four percent (24.4%) of the sample were aged16-25 years; 33.3Cfo were 26-35; 26.7% were 36-45;13.3% \J,.ere 46-55; <strong>and</strong> 2.2% were 56-65. All of theparticipants were first-generation individuals. Thenumber of years living in the United States rangedfrom 1 to 35 years (M = 11.71, SD ; 8.87). Thirtythreepercent (33.3%) of the sample had lived in theUnited States for 1-5 years; 22.2% of the sample hadlived in the United States for 6-10 years; <strong>and</strong> 44.5%of the sample had lived in the United States for morethan 10 years.Sixty-two percent (62.2%) of the participantswere married; 24.5% were never married; 4.4% wereseparated or divorced; <strong>and</strong> 8.9% were in a commonlawmarriage or living together. Eighty-two percent(82.2%) of the participants were Catholic; 6.7Cfo were"Christian"; 8.9% reported "other" religious affiliations;<strong>and</strong> 22% reported no religious affiliation.

il2The primary investigator established contactwith community agencies who have well-establishedties with migrant fannworker camps. These agencieshelped coordinate data collection by accompanyingthe present researchers to the camps <strong>and</strong> introducingthe researchers to the migrant farmworkers. The primaryinvestigator <strong>and</strong> four research assistants collecteddata from nine camps. The four research assistantsunderwent intensive training that providedinstruction on the administration of the instruments<strong>and</strong> focused on issues of cultural competence. Thetraining was conducted by the primary investigatorwho has extensive experience in community-basedresearch with Latin populations.At each labor camp, the researchers recruitedone fannworker from each dwelling. In instances inwhich several unrelated families lived in the samehousehold, more than one participant was recruitedso that each family was represented. Following consent,each participant completed an open-ended interview.The purpose of these interviews was to capturethe phenomenology of the migrant fannworkerlifestyle. The interview data is reported in a separatepaper. After the interview, each participant completeda questionnaire. Because of the low educationallevels <strong>among</strong> some migrant farm workers, theinterviewers offered to read <strong>and</strong> clarify, if necessary,the questionnaire items to each participant. Approximately33% of participants requested assistance. Theparticipants had the option of participating in eitherSpanish or English. Eighty-seven percent (86.7%) ofindividuals partic\pated in Spanish; 13.3% participatedin English. The interview <strong>and</strong> questionnairerequired approximately 1 hour to complete. Eachindividual was reimbursed $20.00 for her or his participation.;\teasuresA self-administered battery of questionnaireswas used. A background information form assessedage, gender, marital status, ethnicity, generationalstatus, religious affiliation, influence of religion,church attendance, education, family income, languageuse, control <strong>and</strong> choice in the decision to immigrateto the United States, <strong>and</strong> control <strong>and</strong> choice inthe decision to live as a migrant farmworker.Religion VariablesTo assess perception of religiosity, influence ofreligion, <strong>and</strong> church attendance, the background in-Hovey <strong>and</strong> Maganaformation form asked three questions. These questionswere previously used (19) to assess religion<strong>among</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> immigrants. They were as follows:"How religious are you?" (Possible responses werethe following: 1 = not at all religious; 2 = slightlyreligious; 3 = somewhat religious; 4 = very religious.)"How much influence does religion have upon yourlife?" (Possible responses were the following: 1 =not at all influential; 2 =:= slightly influential; 3 =somewhat influential; 4 = very influential.) "Howoften do you attend church?" (Possible responseswere the following: 1 = never; 2 = once or twice ayear; 3 = once every 2 or 3 months; 4 = once amonth; 5 = two or three times a month; 6 = once aweek or more.)Control <strong>and</strong> Choice in the Decision to Immigrate tothe United StatesTo assess perception of control <strong>and</strong> choice inthe decision to immigrate to the United States, theparticipants were asked the following questions (4):"Did you contribute to the decision to move to theUnited States?" (Possible responses were the following:1 = not at all; 2 = some [a little bit]; 3 = moderate[pretty much]; 4 = very much [a great deal].) "Didyou agree with the decision to move to the UnitedStates?" (Possible responses wert the following: 1 =strongly disagreed; 2 = disagreed; 3 = agreed; 4 =strongly agreed.)Control <strong>and</strong> Choice in the Decision to Live as aMigrant FarmworkerTo assess perception of control <strong>and</strong> choice inthe decision to live as a migrant fannworker, theparticipants were asked whether they contributed tothe decision to live as a migrant fannworker (1 =not at all; 2 = some; 3 = moderate; 4 = very much)<strong>and</strong> whether they agreed with the decision to live asa migrant farmworker (1 = strongly disagreed; 2 =disagreed; 3 = agreed; 4 = strongly agreed).Family Assessment DeviceThe General Functioning subscale of the FamilyAssessment Device (FAD) (20) was used to measurefamily functioning. The FAD is a self-report scaleconsisting of statements that participants endorse in

<strong>Anxiety</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Depression</strong> <strong>among</strong> Immigrant FarmworkersU3terms of how well each statement describes their family.Items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale("strongly agree" to "strongly disagree"), with scaledscores for each dimension ranging from 1.00 (healthy)to 4.00 (unhealthy). The General Functioning subscaleconsists of 12 items. Examples of items includethe following: "In times of crisis we can turn to eachother for support" <strong>and</strong> "We avoid discussing ourfears <strong>and</strong> concerns." The FAD has been found (4,20-21) to have adequate internal consistency reliability(.71-.92), test-retest reliability (.66-.76), <strong>and</strong> constructvalidity <strong>among</strong> general <strong>and</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong>-Americansamples. The Cronbach alpha for the present studywas.72, thus indicating adequate internal consistencyreliability.The Personal Resource QuestionnaireThe Personal Resource Questionnaire-Part 2(PRQ85) (22) was used to measure social support.This scale measures the perceived effectiveness ofsocial support <strong>and</strong> consists of 25 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale ("strongly disagree" to "stronglyagree"). Possible scores range from 25 to 175. Higherscores indicate higher levels of perceived social support.Examples of items include the following: "1belong to a group in which 1 feel important"; "1 havepeople to share social events <strong>and</strong> fun activities with";..1 can't count on my friends to help me with problems";<strong>and</strong>" Among my group of friends we do favorsfor each other." The PRQ85-Part 2 has been found(4,22-24) to have adequate internal consistency reliability(.85-.93), test-retest reliability (.72), <strong>and</strong>construct validity <strong>among</strong> general <strong>and</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong>-Americansamples. The Cronbach alpha for the presentstudy was .92.Adult Self-Perception ScaleSelf-esteem was measured with the Global Self-Worth sub scale of the Adult Self-Perception Scale(25). The subscale consists of 6 items, each of whichis scored 1 to 4, with possible scores ranging from 6to 24. Higher scores indicate higher levels of selfesteem.The Global Self-Worth subscale has beenfound (25-26) to have adequate internal consistencyreliability. test-retest reliability, <strong>and</strong> construct validity<strong>among</strong> general <strong>and</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong>-American samples.SAFE Scale<strong>Acculturative</strong> stress was measured with theSAFE scale (9). This scale consists of 24 items thatmeasure acculturative stress in social. attitudinal. familial,<strong>and</strong> environmental contexts. in addition toperceived discrimination toward acculturating populations.Participants rate each item that applies tothem on a 5-point Likert scale ("not stressful" to"extremely stressful"), Examples of items include thefollowing: "People think I am unsociable when infact 1 have trouble communicating in English"; "Itbothers me that family members I am close to do notunderst<strong>and</strong> my new values"; <strong>and</strong> "Because of myethnic background, I feel that others exclude me fromparticipating in their activities," If an item does notapply to a participant, it is assigned a score of O.The present investigators slightly revised the scaleby adding two additional items: "I feel guilty because1 have left family or friends in my home country";<strong>and</strong> "I feel that I will never gain the respect that Ihad in my home country," The scale used in thisparticular study thus consisted of 26 items, with possiblescores ranging from 0 to 130, Higher 'scores indicatehigher levels of acculturative stress. The SAFEscale has been found (4, 9-10) to have adequateinternal consistency reliability (.89-.90) <strong>and</strong> constructvalidity <strong>among</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong>-American samples.The Cronbach alpha for the present study 'Nas.88.Personality Assessment Inventory (PAl)The <strong>Anxiety</strong> scale of the Personality AsscssmentInventory (PAl) (27) was used to measure anxiety,This scale measures clinical features of symptomatologyrelated to anxiety disorders <strong>and</strong> consists of 24items rated on a 4-point scale ("false, not at all true"to "very true"). Higher scores indicate higher anxietylevels. Examples of items include the f01lowing: "Iam so tense in certain situations that I have greatdifficulty getting by"; "When I'm under a lot of pressure,I sometimes have trouble breathing"; "I oftenhave trouble concentrating because I'm nervous";<strong>and</strong> "I usually worry about things more than Ishould," The accepted caseness threshold is 60, Ascore of 60 or more represents potentially significantanxiety, which may impair functioning. It is estimated(27) that 16% of general population individuals willreach caseness. The PAl <strong>Anxiety</strong> scale has beenfound (27-29) to have adequate internal consistencyreliability (.80-.90), test-retest reliability (.85-.88),

U4<strong>and</strong> construct validity <strong>among</strong> general <strong>and</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong>-American samples. The Cronbach alpha for the presentstudy was .91.Center for Epidemiologic Studies <strong>Depression</strong> ScaleThe Center for Epidemiologic Studies <strong>Depression</strong>Scale (CES-D) (30) was used to measure depression.The CES-D assesses level of depressive symptomswithin the previous week <strong>and</strong> consists of 20items rated on a 4-point scale ("rarely or none of thetime" to "most or all of the time"). Possible scoresrange from 0 to 60. Higher scores indicate higherdepression. The accepted caseness is a score of 16 ormore, which represents the upper 18% of scores (31).A score of caseness indicates the presence of potentiallysignificant depressive symptomatology. Severalstudies (4, 32-33) have found that the CES-D hasadequate internal consistency reliability (.81-.90)<strong>and</strong> construct validity <strong>among</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong>-Americansamples. The Cronbach alpha for the present studywas .80.TranslationThe Spanish version of the PAl (34) that wasused in the present study was translated by PsychologicalAssessment Resources, Inc. The backgroundinformation form, the FAD. the PRQ-85, the AdultSelf-Perception Scale, the SAFE, <strong>and</strong> the CES-Dwere translated into Spanish through the doubletranslationprocedure (35) with the help of two translators.Data AnalysesThe data analyses are presented in three steps.Descriptive statistics are presented first. Second, correlationcoefficients that were used to assess the relationships<strong>among</strong> the predictor variables (i.e., acculcurativestress, family functioning, social support,self-esteem, church attendance, perception of religiosity,influence of religion, contribution to the decisionto immigrate, agreement with the decision toimmigrate, contribution to the decision to live as amigrant farmworker, agreement with the decision tolive as a migrant farm worker, education, <strong>and</strong> income)<strong>and</strong> dependent variables (anxiety <strong>and</strong> depression)are presented. Finally, two forward stepwise multipleHovey <strong>and</strong> Maganaregression analyses are presented. They were conductedto determine the best predictors pf anxiety<strong>and</strong> depression. For each regression analysis, the criteriafor entering the equation was set at F = 3.84.RESULTSDescriptive StatisticsEducation <strong>and</strong> IncomeTable I shows the frequency distributions foreducation <strong>and</strong> income. Most individuals reported relativelylow levels of education <strong>and</strong> extremely lowlevels of income. The median level of education was6-8 years of schooling. Thirteen percent (13.3%) ofthe sample reported high education levels, which isrepresented by high school graduation <strong>and</strong> greater.Church Attendance, Perception of Religiosity, <strong>and</strong>Influence of ReligionTable I shows the frequency distribution forchurch attendance. About two-thirds of individualsattended church at least 2 or 3 times per month. Themean score for perception of religiosity was 2.41Table t. Sample Distributions for Sociodemographic Variables-EntireVariable Females Males sampleEducalion0-2 years or school3-5 years or school6-8 years or school9-11 years or schoolHigh school graduateSome collegeIncomeSO-S4,999S5,

<strong>Anxiety</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Depression</strong> <strong>among</strong> Immigrant Famlworkers 125(SD = 0.76). This mean represents a moderate levelof perceived religiosity. The mean score for influenceof religion was 2.93 (SD = 1.00). This mean representsa relatively high level of influence of religion.Contribution to <strong>and</strong> Agreement with the Decision toImmigrate to the United StatesThe mean score for contribution to the decisionto immigrate was 3.05 (SD = 1.12). The mean scorefor agreement with the decision to immigrate was3.21 (SD = 0.97). These means represent a relativelyhigh level of contribution <strong>and</strong> agreement.Contribution to <strong>and</strong> Agreement with the Decision toLive as a Migrant FarmworkerThe mean score for contribution to live as amigrant farmworker was 3.20 (SD = 1.14). The meanscore for agreement to live as a migrant fannworkerwas 3.07 (SD = 0.97). These means represent a relativelyhigh level of contribution <strong>and</strong> agreement inthe decision to live as a migrant fannworker.Family Functioning <strong>and</strong> Social SupportThe mean score for the General Functioningsubscale of the FAD (family functioning) was 2.07(SD = 0.43). The mean score for the PRQ85 (socialsupport) was 126.09 (SD = 33.24). These two meansrepresent overall moderate levels of support.Self-EsTeemThe mean score for self-esteem was 18.51 (SD =3.24). This represents a moderate level of self-esteem.Accu/turative <strong>Stress</strong>, <strong>Anxiety</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Depression</strong>Table II lists the means <strong>and</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ard deviationsfor the SAFE scale (acculturative stress). the PAlTable II. Mean Scores <strong>and</strong> St<strong>and</strong>ard Deviations on Measures of<strong>Acculturative</strong> <strong>Stress</strong>, <strong>Anxiety</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Depression</strong>OverallFemalesMales<strong>Acculturative</strong>stress <strong>Anxiety</strong> <strong>Depression</strong>Mean (SD) Mean (SD) Mean (SD)57.8 (21.4)55.3 (17.6)59.9 (24.2)55.0 (14.0)56.5 (13.9)53.8 (14.3)14.5 (10.2)13.8 (9.4)15.0 (10.9)(anxiety). <strong>and</strong> the CES-D (depression). The presentsample revealed a relatively high level of anxiety(M = 55.0) in comparison to the expected mean of50 (27) in general population individuals (r [44J =2.4, P < .01). Twenty-nine percent (28.9%) of theparticipants reached caseness on the PAl with a scoreof 60 or greater, compared to the expected 16% (27).The present sample revealed a relatively high levelof depression. Thirty-eight percent (37.8%) of theparticipants reached caseness with a score of 16 orgreater on the CES-D, compared to the expected18% (31).To note, ANDY As revealed no significant maineffects for gender, generation level, age (16-25 years,26-35.36-45,46-55.56-65), <strong>and</strong> language of participationon acculturative stress, anxiety, <strong>and</strong> de.pression.Correlations <strong>among</strong> Predictor Variables<strong>and</strong> <strong>Anxiety</strong>Table III shows the correlations <strong>among</strong> the predictorvariables <strong>and</strong> anxiety. Greater education, lowlevels of perception of religiosity, low levels of influenceof religion. low contribution to the decision toimmigrate, low contribution to the decision to liveas a migrant farmworker, low self-esteem, ineffectiveTable Ill. Correlations <strong>among</strong> Prcdictor Variables <strong>and</strong> <strong>Anxiety</strong><strong>and</strong> <strong>Depression</strong>'EducationIncomePerception of religiosityPerceived influence of religionChurch attendanceContribute to decision to immigrateAgreement with decision toimmigrateContribute to migrant farmworkAgreement with migrantfarm workSelf-esteemSocial supportFamily functioning<strong>Acculturative</strong> stress<strong>Anxiety</strong><strong>Anxiety</strong>.25**.07-.24**-.29*.-.06-.24**<strong>Depression</strong>-.01-.06.23..-.01-.25..-.19--.01 -.23---.2988 -.13-.14 -.41----.34----.25--'Significance levels are based on one-tailed tests..p < .10; ..p < .05; ...p < .01; p < .001.-.03.64-.53 -.52.1S..57

.00)U6social support. <strong>and</strong> high levels of acculturative stresswere related to high levels of anxiety.Correlations <strong>among</strong> Predictor Variables<strong>and</strong> <strong>Depression</strong>Table III lists the correlations <strong>among</strong> the predictorvariables <strong>and</strong> depression. Greater education,infrequent church attendance, low contribution tothe decision to immigrate, low agreement with thedecision to immigrate, low agreement with the decisionto live as a migrant farmworker, low self-esteem,ineffective social support, family dysfunction, highlevels of acculturative stress, <strong>and</strong> high levels of anxietywere related to elevated levels of depression.Multiple Regression Analysis or <strong>Anxiety</strong>Table IV shows a stepwise multiple regressionanalysis that was conducted to determine the bestpredictors of anxiety. In this analysis, education, perceptionof religiosity, influence of religion, contributionto the decision to immigrate, contribution to theHovey <strong>and</strong> Maganadecision to live as a migrant farmworker. self-esteem.social support. <strong>and</strong> acculturative stress were enteredas predictors of anxiety. Significant independent predictorsof anxiety were acculturative stress (13 = .59.1 = 4.9. P < .(xx)1). contribution to the decision tolive as a migrant farmworker (13 = -.37. t = -3.2,p < .003), <strong>and</strong> influence of religion (13 = -.20.1 =-1.7. P < .10). As seen in Table IV. these variablesaccounted for 50% of the variance in anxiety. Theother variables added minimal variance to the equation.The overall equation accounted for 53% of thevariance in anxiety.Multiple Regression Analysis of <strong>Depression</strong>Table V shows a stepwise multiple regressionanalysis that was conducted to determine the bestpredictors of depression. Education, church attendance,contribution to the decision to immigrate,agreement with the decision to immigrate, agreementwith the decision to live as a migrant farmworker,self-esteem, social support, family functioning, acculturativestress. <strong>and</strong> anxiety were entered as predictorsof depression. Significant independent predictors of<strong>Anxiety</strong> symptoms (PAl)"SAFESAFE. Contribute to migra-,t CarmworkSAFE. Contribute to migrant farrnwork,influenceSAFE, Contribute to migrant Carrnwork.influence, contribute to moveSAFE. Contribute to migrant farrnwork,influence. contribute to move, religiositySAFE. Contribute to migrant farrnwork,influence, contribute to move. religiosity,PROSAFE, Contribute to migrant farrnwork,influence. contribute to move, religiosity,PRO, self.esteemSAFE, Contribute to migrant farrnwork,influence. contribute to move, religiosity,PRO, self-esteem, education22.0617.5213.13(1,41)(2,40)(3,39).000.000.00035.046.750.210.10 (4,38) .(XX) 51.58.05 (5.37)6.68 (6.36)52.1.COO 52.75.65 (7.35) .00) 53.14.83 (8.34) .(XX) 53.2'PAI = <strong>Anxiety</strong> subscaJe oc Personality A5sessment Inventory; PRQ= Persona! Resource Questionnaire(social support); SAFE = Socia!. Attitudinal. Familial, <strong>and</strong> Environmental acculturative stress scale;Inftuence = inftuence of religioa; Contribute to move = contribution to the decision to immigrateto the United States; Contribute to migrant Cannwork = contribution to the decision to live as amigrant Cannworker.

<strong>Anxiety</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Depression</strong> <strong>among</strong> Immigrant Fannworkers 127Table V. Multiple Regression of <strong>Depression</strong> <strong>among</strong> Migrant FarmworkersTotalpercentageDependent <strong>and</strong>variancepredictor variables F Cd/) p accounted forDepressive symptoms (CES-D)"PAlPAl, PRO.PAl, PRO, Self-esteemPAl, PRO, Self-esteem, attendancePAl, PRO, Self-esteem, attendance, agreewith migrant fannworkPAl, PRO, Self-esteem, attendance, agreewith migrant fannwork, contribute to movePAl, PRO, Self-esteem, attendance, agree withmigrant fannwork, contribute to move, SAFEPAl, PRO, Self-esteem, attendance, agree withmigrant fannwork, contribute to move, SAFE,agree with movePAl, PRO, Self-esteem, attendance, agreewith migrant fannwork, contribute to move,SAFE, agree with move, educationPAl, PRO, Self-esteem, attendance, agreewith migrant fannwork, contribute to move,SAFE, agree with move, education, FAD20.3418.7114.9113.39(1.40)(239)(3.38)(4.37).000.000.000.00011.64 (5.36) .00010.31 (635) .(XX)9.04 (7.34) .0007.85 (8.33) .(XX)6.83 (9.32) .(XX)6.00 (10.31) .(XX)33.749.054.159.161.8'CES.D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies <strong>Depression</strong> Scale; PAl = <strong>Anxiety</strong> subscale of PersonalityAssessment Inventory; PRQ := Personal Resource Questionnaire (social support); FAD -FamilyAssessment Device; SAFE = Social, Attitudinal, Familial, <strong>and</strong> Environmental acculturative stress scale;Attendance = church attendance; Contribute to move = contribution to the decision to immigrate tothe United States; Agree with move = agreement with the decision to immigrate to the United States;Agree with migrant farmwork = agreement with the decision to live as a migrant farmworker.63.965.065.665.865.8depression were anxiety ({3 = .58, t = 4.5, p < .0001),social support ({3 = -.40, t = -3.4, P < .002), selfesteem({3 = -.28, t = -2.3, p < .03), church attendance({3 = -.24, t = -2.4, p < .03), <strong>and</strong> agreementwith the decision to live as a migrant fannworker({3 = -.21, t = -1.8, p < .10). These five variablesaccounted for 62% of the variance in depression. Theremainder of the variables added little variance. Theoverall equation accounted for 66% of the variancein depression.DISCUSSIONThe major theme of this study is that the immigrationexperience in conjunction with the migrantfarmworker lifestyle may put an individual at psychologicalrisk. As mentioned, no previous studies haveaddressed the psychological functioning of immigrantfarmworkers in the midwest United States. Therefore,a purpose of the present study was to examineacculturative stress, anxiety, <strong>and</strong> depression withinthis context. These findings contribute critical informationboth to the acculturative stress literature <strong>and</strong>to the cross-cultural literature on depression <strong>and</strong>anxiety.Because qualitative data portray a sense of individualexperience that is often lacking in quantitativedata. the following discussion is highlighted with examplesof narrative responses from the interviews.<strong>Acculturative</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> in Relation to <strong>Anxiety</strong><strong>and</strong> <strong>Depression</strong>In the present study, migrant farm workers experiencingelevated levels of acculturative stress alsoreported high levels of anxiety <strong>and</strong> depression. Theseacculturating fannworkers may feel caught betweencultures. That is, these individuals may feel pulledbetween the influence of traditional customs, values,<strong>and</strong> norms <strong>and</strong> the values, nonns, <strong>and</strong> customs foundin the mainstream society. Experiences of economichardship, language difficulties, <strong>and</strong> discrimination

usmay further contribute to distress during the acculturativeprocess. Many farrnworkers reported experiencingdiscrimination <strong>and</strong> exploitation. For example,the following narrative, reported by a 26-year-oldmale, captures such experiences.There are lots of thieves. On one occasion I caughtone guy who was trying to steal from our home. Itook him to the police. The police said we couldpress charges. so we did. but the thief was releasedon the third day because he was a U.S. citizen. Thebottom line is that they let him go free becausewe are not U.S. citizens. so the police did not payattention to our charges.They are supposed to pay us weekly or every otherweek, but they take longer to pay us. They makeexcuses such as they don't have the checks, or theymay say to come back another day. We need themoney right away but they still don't pay us. Usuallythe contractors take advantage of the people whoare new <strong>and</strong> who know nothing about being a farmworker.Levels of <strong>Anxiety</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Depression</strong> <strong>among</strong>Migrant FarmworkersRelatively high levels of anxiety <strong>and</strong> depressionwere found in the present sample. As noted, 38% ofthe sample reached depression caseness with a CES-D score of 16 or greater. This percentage appears tobe high. As a comparison, about 18% of individualsfrom general population samples reach the casenessthreshold (30, 36). As a further comparison, Vega etat. (31) noted the very high prevalence of depressivesymptoms found within their sample of <strong>Mexican</strong> immigrants.They found that 42% of their sample scored16 or greater. It is important to note that the highoverall rate of anxiety <strong>and</strong> depression found in thepresent sample does not imply that all immigrantfarmworkers, per se, are highly anxious <strong>and</strong>/or depressed,but that the experiences that go into beingan immigrant farmworker (e.g., discrimination, languageinadequacy, reduced self.esteem, financialstressors, lack of family <strong>and</strong> social support) potentiallyinfluence psychological status.The present study measured depression as a constellationof symptoms <strong>and</strong> did not obtain specificclinical information about the onset, duration, <strong>and</strong>severity of the symptoms. Although the CES-D isnot a diagnostic instrument, it was found (37) to havea concordance of 85% for current major depressionusing the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (38). There.Hovey <strong>and</strong> Maganafore, the present findings have relevance for clinicalwork <strong>and</strong> research <strong>among</strong> immigrant farmworkers.Predictors of <strong>Anxiety</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Depression</strong>Social Support <strong>and</strong> Self-EsteemThe present study measured the perceived effectivenessof social support rather than access to socialsupport networks. Several authors (39-41) havenoted that larger social networks do not ensure thatthe support will be of higher quality or more effective,<strong>and</strong> therefore the perceived quality of social supportmay be a more accurate predictor of psychologicaldistress than is quantity of social support. The presentfindings indicated that ineffective social support wasstrongly related to heightened levels of anxiety <strong>and</strong>depression. These findings thus lend support to theidea that social support of high quality may helpimmigrant farm workers cope against anxiety <strong>and</strong> depression.<strong>Mexican</strong> culture traditionally emphasizes collectivistvalues <strong>and</strong> affiliation (42). <strong>Mexican</strong> immigrantsmay thus feel particularly vulnerable when they lacksocial support. Because social support helps provideindividuals with a sense of belonging <strong>and</strong> identity,ineffective social support may lead acculturating individualsto feel undervalued <strong>and</strong> contribute to lowself-esteem (43). Moreover, given that self-esteemmay help buffer against distress during the acculturativeprocess (44), low self-esteem may place an individualat greater risk for distress. Not surprisingly, thepresent findings indicated a very strong relationshipbetween low self-esteem <strong>and</strong> elevated levels of anxiety<strong>and</strong> depression.Control <strong>and</strong> Choice in the Decisions to Immigrate<strong>and</strong> to Live as a MigrantFarmworkerSalgado de Snyder (45) <strong>and</strong> Vega er ai. (46),in their respective studies of depression risk factors<strong>among</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> immigrants, found that those individualswho voluntarily immigrated ("wanted to") to theUnited States revealed significantly less depressivesymptoms than those individuals who involuntarilyimmigrated ("had to"). These findings suggest thatindividuals who are willing to immigrate may be atless risk for depression than those who are not willing.In other words, greater depression <strong>among</strong> those whodo not choose to immigrate may be due to the effects

<strong>Anxiety</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Depression</strong> <strong>among</strong> Immigrant Farmworkers 129of the lack of empowerment to control their liveswhen migration occurs. This notion has relevance forthe present study. The present study assessed bothinternational migration <strong>and</strong> the participants' migrationas farm workers. The farmworkers were askedwhether they contributed to <strong>and</strong> agreed with movingto the United States, <strong>and</strong> whether they contributedto <strong>and</strong> agreed with the decision to live as a migrantfarmworker, or whether they were involved in fannworkdue to the desire of others. Not surprisingly,it was generally found that those farmworkers whowillingly migrated reported less anxiety <strong>and</strong> depressionthan those who did not.EducationBerry et al. (47) noted that education may helpprovide acculturating individuals with the resourcesto cope with the larger society. They believed thatthose individuals with more education may havegreater cognitive, economic, <strong>and</strong> social resources withwhich to deal with changes. The direction of educationas a predictor in the present study was thereforesurprising. High education was associated with depression.This finding may depend partly on the questionof comparison. Some fannworkers may comparetheir current situation to a lower socioeconomic experiencein Mexico. However, farmworkers who aremore educated may be more sensitive to the discrepancybetween their current life conditions <strong>and</strong> thoseof other individuals in the United States. Those whoare more educated may also have set life <strong>and</strong> careergoals other than migrant farmwork, <strong>and</strong> may havefelt that they have failed to reach these goals. Thefollowing narrative is from a relatively educated (highschool graduate) 39-year-old male who seems awareof the disparity between his current socioeconomicsituation <strong>and</strong> those of others in the United States:We receive such miserable pay as migrants. I believethat migrants are a resource. We are a very importantpart of the growth <strong>and</strong> feeding of this country. <strong>and</strong>I believe we have a right to be recognized for ourhard work. either by the government or the labordepartment. They pay no more than minimum wage<strong>and</strong> that is too little to get by. Everything is so expensive.We should have better pay. It is our right.Suggestions for Prevention <strong>and</strong> TreatmentCurrently, in the area sampled, there is little tono prevention <strong>and</strong> treatment options available forimmigrant farmworkers who experience psychologicalproblems. This situation may also exist in otherareas of the United States. The present findings, however,suggest the need for prevention. assessment,<strong>and</strong> treatment services for immigrant farmworkers.It is crucial that prevention efforts be directedtoward those farmworkers who are at risk for anxiety<strong>and</strong> depression. These include farmworkers who areisolated, lack emotional support <strong>and</strong> self-esteem, <strong>and</strong>who experience elevated levels of acculturativestress. Possible preventive strategies include the establishmentof support groups, at the camps or localcommunity centers, \1I11ere migrant workers can talkabout their difficult experiences <strong>and</strong> the ways inwhich they can cope with these difficulties. Supportgroups would provide emotional support <strong>and</strong> increaseself-esteem. Several participants in the presentstudy expressed interest in the establishment of supportgroups.Second, educational workshops <strong>and</strong> presentations(48-49) can be conducted by health professionals.Because for utmost prevention it is importantthat these educational workshops <strong>and</strong> presentationsbe accessible to migrant workers, they should be establishedat easily accessible locations such as migrantcamps, community centers, or local schools. Theselectures <strong>and</strong> workshops can address specific topicssuch as risk factors for anxiety <strong>and</strong> depression, substanceabuse, <strong>and</strong> how to cope with the stress of amigratory lifestyle. These educational programswould be preventive in that active participationwould help thwart future problems in these areas.The church can be another possible site for prevention.Several characteristics of the church may bepreventive (19). Religious organizations foster socialnetworking <strong>and</strong> thereby reduce risk through socialsupports. Moreover, church attendance providesgreater exposure to basic religious beliefs thought toincrease coping. As expected, the present findingsindicated a negative relationship betWeen religiosity<strong>and</strong> distress. Church members may also use theirministers or priests as sources of support in times ofdistress. In addition to such supportive roles, clergymembers may disseminate information to farmworkersregarding the availability of other community services.Because the cultural importance of the churchextends beyond the scheduled religious services, outreachprograms that are sponsored by the churchbutnot necessarily held at the church-are likely tohave the respect of migrant workers.Finally, preventive efforts can be incorporatedinto lay health-worker programs (50-51). Lay health-

130 Hovey <strong>and</strong> Mag:ciiaworker programs use individuals who are former orcurrent migrant farmworkers who are trained to providehealth information to migrant farmworkers. Thelay health-workers organize <strong>and</strong> run educational <strong>and</strong>preventive workshops (sample topic: HIV / AIDS prevention)<strong>and</strong> act as liaisons between communityagencies/health services <strong>and</strong> migrant farmworkers.Lay health-worker programs have been shown to beeffective preventive resources (51) <strong>and</strong> to be veryempowering for migrant farmworkers (50). In additionto being educational, these programs may helpprovide social contacts <strong>and</strong> increase self-esteem<strong>among</strong> migrant workers.For the farm worker who may be experiencingacculturative stress, anxiety, <strong>and</strong>/or depression, thefindings highlight the importance of assessment <strong>and</strong>treatment within a cultural context. In other words,clinical evaluation <strong>and</strong> treatment should carefully addressthe stress related to farmwork; the stress relatedto acculturation; family <strong>and</strong> social support; the farmworker'ssense of self; the farmworker's hopes <strong>and</strong>expectations for the future; <strong>and</strong> past <strong>and</strong> present copingstrategies, including religion. Treatment for migrantworkers should be short term in focus becauseof the migratory nature of their lifestyle. Moreover.the clinician should be aware of mental health servicesthat are available in the farmworker's otherareas of residence.Limitations <strong>and</strong> Directions for Future ResearchThis study should be considered preliminary becauseof its relatively limited sample size, its selfreportmethod, <strong>and</strong> its cross-sectional design. In addition.the homogeneity of the sample in terms ofethnicity <strong>and</strong> area sampled suggests that these findingsshould not be generalized to the West Coast <strong>and</strong>East Coast migrant farmworker streams. Similarly,the findings should not be generalized to migrantfarrnworkers of other ethnicities in the Midweststream. Although the instruments used were shownto be reliable in the present study <strong>and</strong> have previouslybeen validated on <strong>Mexican</strong> immigrants, thesescales have yet to be fully validated on <strong>Mexican</strong>migrant farmworkers. The present study assessedthe influence of religiosity on anxiety <strong>and</strong> depression.It is unclear how the findings would have differedif spirituality was also measured. Future researchshould thus use a more comprehensive measure ofreligion that is able to distinguish between the socialaspects, religious practices, <strong>and</strong> spiritual dimensionsof religion.Further research should concentrate on increasingthe study's generalizability. This includes researchof a representative nature that examines the specificpathologies found <strong>among</strong> migrant farm workers, exploresthe mental health differences between migrant<strong>and</strong> seasonal farmworkers, <strong>and</strong> examines the psychologicalfunctioning of migrant farm workers in othermigrant streams. Qualitative research is needed toidentify those stressors specific to the migrant farmworkerlifestyle <strong>and</strong> the coping mechanisms that areemployed in response to these stressors. This informationwill be useful in establishing preventive ser-..;ces for migrant farmworkers.ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThis work was supported in part by a SummerResearch Fellowship <strong>and</strong> Research Grant, UniversityResearch Awards <strong>and</strong> Fellowship Program, Universityof Toledo. The authors thank Migrant HealthPromotion, Inc., <strong>and</strong> Rural Opportunities, Inc., fortheir help in arranging data collection.REFERENCES1. Hovey JD: Psychosocial prediclo~ of acculluralive stress inCentral American immigrants. J Immigrant Health 1999;1:187-194:. Williams CL. Berry JW: Primary prevention of acculturativestress <strong>among</strong> refugees: Application of psychological theory<strong>and</strong> practice. Am Psycho I 1991; 46:632-6413. Hovey JD: <strong>Acculturative</strong> stress. depression. <strong>and</strong> suicidal ideation<strong>among</strong> Central American immigrants. Suicide LifeThreat Behav 2roo; 30:125-1404. Hovey JD: <strong>Acculturative</strong> stress, depression, <strong>and</strong> suicidal ideationin <strong>Mexican</strong> immigrants. Cultural Diversity <strong>and</strong> Ethnic~iinorily Psychology 200>; 6:134-1515. Hovey JD, King CA: <strong>Acculturative</strong> stress. depression. <strong>and</strong>suicidal ideation <strong>among</strong> immigrant <strong>and</strong> second generation Latinoadolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996:35:1183-11926. Hovey JD. King CA: Suicidality <strong>among</strong> acculturating <strong>Mexican</strong>-Americans: Current knowledge <strong>and</strong> directions for research.Suicide Life Threat Behav 1997; 27:92-1037. Berry JW: Psychology of acculturation. In: Berman JJ, ed.:..'ebraska Symposium on Motivation: Vol. 37. Cross-CulturalPe~pectives. Lincoln: Unive~ity of Nebraska Press; 1990:201-2348. Berry JW, Kim U: Acculturation <strong>and</strong> mental health. In: DasenP. Berry JW, Sartorius N. eds. Health <strong>and</strong> Cross-Cultural Psy-~bology: Towards Application. London: Sage; 1988: 207-2369. Mena FJ. Padilla AM. Maldonado M: Accullurative stress <strong>and</strong>spe~jfic coping strategies <strong>among</strong> immigrant <strong>and</strong> later generationcollege students. Hispani~ J Behav ~i 1987; 9:207-22510. Padilla AM. Alvarez M. Lindholm KJ: Generalional status

<strong>Anxiety</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Depression</strong> <strong>among</strong> Immigrant Fannworkers 131<strong>and</strong> personality factors as predictors of stress in students. HispanicJ Behav Sci 1986; 8:275-28811. Dona G. Berry JW: Acculturation attitudes <strong>and</strong> acculturativestress of Central American refugees. International Journal ofPsychology 1994; 29:57-7012. Barger WK. Reza EM: The Fann Labor Movement in theMidwest. Austin: University of Texas Press; 199413. Rothenberg D: With These H<strong>and</strong>s: The Hidden World ofMigrant Farmworkers Today. New York: Harcourt Brace &Company; 199814. Goldfarb RL: Migrant Farm Workers: A Caste of Despair.Ames: Iowa State University Press; 198115. Farm Labor Organizing Committee: Fannworkers <strong>and</strong> FannLabor Conditions [online]. Available: http://www.iupui.edu/-fioclfws.htm; 199816. Valdes DN: AI Norte. Austin: University of Texas Press; 199117. Vega W. Warheit G, Palacio R: Psychiatric symptomatology<strong>among</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong> American fannworkers. Sac Sci Med 1985;20:39-4518. MacMillan A: The Health Opinion Survey: Technique forestimating prevalence of psychoneurotic <strong>and</strong> related types oCdisorders in communities. Psychol Rep 1957; 3:325-32919. Hovey JD: Religion <strong>and</strong> suicidal ideation in a sample of LatinAmerican immigrants. Psycho I Rep 1999; 85:171-17720. Epstein NB. Baldwin LM. Bishop DS: The McMaster FamilyAssessment Device. J Marital Fam Ther 1983; 9:171-18021. Halvorsen JG: Self-report family assessment instruments: Anevaluative review. Family Practice Res J 1991; 11:21-5522. Weinert C: A social support measure: PRO85. Nun Res1987; 36:273-27723. Weinert C. Br<strong>and</strong>t PA: Measuring social support with thePersonal Resource Questionnaire. Western J Nurs Res1987: 9:589-60224. Weinert C. TildenVP: Measures of social support: Assessmentof validity. Nurs Res 1990; 39:212-21625. ~1esser B. Harter S: Manual: Adult Self-Perception Scale. Denver:University of Denver Press: 198626. Knight GP. Virdin LM. Ocampo KA. Roosa M: An examinationof the cross-ethnic equivalence of measures of negativelife events <strong>and</strong> mental health <strong>among</strong> Hispanic <strong>and</strong> Anglo.American Children. Am J Community Psychol 1994;22:767-78327. Morey LC: Personality Assessment Inventory: ProCessionalManual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources; 199128. Fantoni-Salvador P. Rogers R: Spanish versions of the MMPI.2 <strong>and</strong> PAl: An investigation of concurrent validity with His.panic patients. Assessment 1997; 4:29-3929. Rogers R. Flores J. Ustad K, Sewell KW: Initial validation ofthe Personality Assessment Inventory-Spanish version withclients from <strong>Mexican</strong> American communities. J Pers Assessment1995; 64:340-34830. Radloff LS: The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scalefor research in the general population. Appl Psycho I Meas1977; 1 :385-40131. Vega W A, Kolody B. Valle R, Hough R: Depressive symptoms<strong>and</strong> their correlates <strong>among</strong> immigrant <strong>Mexican</strong> women in theUnited States. Sac Sci Med 1986; 22;645-65232. Golding JM, Aneshensel CS: Factor structure of the Centerfor Epidemiologic Studies <strong>Depression</strong> scale <strong>among</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong>Americans <strong>and</strong> non-Hispanic whites. Psychol Assessment1989; 1:163-16833. Golding 1M. Aneshensel CS. Hough RL Responses to depressionscale items <strong>among</strong> <strong>Mexican</strong>-Americans <strong>and</strong> non-Hispanicwhites. 1 Clin Psycholl991; 47:61-7534. Morey LC: Personality Assessment Inventory: Spanish Translation.Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources; 199235. Brislin RW: Translation <strong>and</strong> content analysis of oral <strong>and</strong> writtenmaterial. In: Tri<strong>and</strong>is HC. Berry JW. eds. H<strong>and</strong>book ofCross-Cultural Psychology: Vol. 2. Methodology. New York:Wiley: 1980: 389-44436. Weissman M. Meyers J: Rates <strong>and</strong> risks of depressive symptomsin a United States urban community. Acta PsychiatrSc<strong>and</strong> 1978: 57:219-23137. Hough. R: Comparison of psychiatric screening questionnairesfor primary care patients. Final Report prepared for AD-AMHA. Division of Biometry <strong>and</strong> Epidemiology. NationalInstitute of Mental Health (Cantract No. 278-81-0036): 198338. Robins LN. Helzer JE. Croughan J. Ratcliff K: Nationallnstituteof Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: Its history.characteristics. <strong>and</strong> validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry1981; 38:381-38939. Golding 1M. Burnam MA: <strong>Stress</strong> <strong>and</strong> social support as predictorsof depressive symptoms in <strong>Mexican</strong> Americans <strong>and</strong>non-Hispanic whites. J Sac Clin Psychol 1m-. 9:268-28740. Hovey JD: The moderating influence or socia! support onsuicidal ideation in a sample of <strong>Mexican</strong> immigrants. PsycholRep 1999: 85:78-7941. Sarason IG. Levine HM. Basham RB. Sarason BR: Assessingsocial support: The Social Support Questionnaire. J Pers SacPsychoI1983; 44:127-13942. Alvarez RR: Familia. Berkeley: University of CaliforniaPress; 198743. Smart IF. Smart DW: <strong>Acculturative</strong> stress of Hispanics: Loss<strong>and</strong> challenge. J Counsel Devell995; 73:390-39644. Espin OM: Psychological impact of migration on Latinas. PsycholWomen Q 1987; 11:489-50345. Salgado de Snyder VN: Factors associated with acculturativestress <strong>and</strong> depressive symptomatology <strong>among</strong> married <strong>Mexican</strong>immigrant women. Psychol Women Q 1987; 11:475-48846. Vega WA, Kolody B. Valle lR: Migration <strong>and</strong> mental health:An empirical test of depression risk factors <strong>among</strong> immigrant<strong>Mexican</strong> women. Inl Migration Rev 1987; 21:512-53047. Berry lW. Kim U. Minde T, Mok D: Comparative studies ofacculturative stress. Int Migration Rev 1987; 21:491-51148. Davis 1M, S<strong>and</strong>oval J, Wilson MP: Strategies for the primaryprevention of adolescent suicide. School Psychol Rev 1988;17:559-56949. S<strong>and</strong>oval J: Crisis counseling: Conceptualizations <strong>and</strong> generalprinciples. School Psychol Review 1985; 14:257-26550. Booker VK, Robinson JG, Kay BJ. Gutierrez-Najera L. StewartG: Changes in empowerment: Effects of panicipation ina lay health promotion program. Health Educ Behav 1997;24:452-46451. Harlan C. Eng E. Watkins E: Migrant lay health advisors: Astrategy for health promotion. In: McDuffie HH. Dosman JA.Semchuk KM. Olenchok SA, eds. Agricultural Heallh <strong>and</strong>Safety: Workplace, Environment, Suslainability. New York:CRC Press; 1995:499-502