Ecofeminism in the twenty-first century

Ecofeminism in the twenty-first century

Ecofeminism in the twenty-first century

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

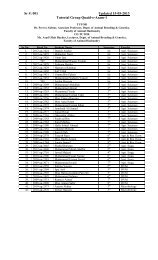

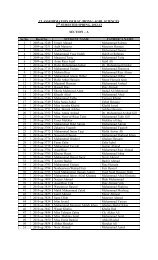

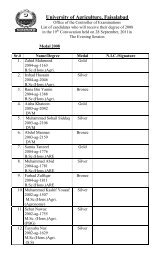

148 <strong>Ecofem<strong>in</strong>ism</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>twenty</strong>-<strong>first</strong> <strong>century</strong>Table 1 Strategies for l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g women and environmentBr<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g gender <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> environmentBr<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> environment <strong>in</strong>to gender1992 United Nations Conference on1995 United Nations 4th Conference onEnvironment and DevelopmentWomen and Platform of Action2002 World Summit on Susta<strong>in</strong>able Development UK Government Gender Ma<strong>in</strong>stream<strong>in</strong>g adviceEU Gender Ma<strong>in</strong>stream<strong>in</strong>g DGXI<strong>in</strong>corporates examples from <strong>the</strong> environment fieldEnvironmental Justice movement‘practical’ needs as better childcare (or, <strong>in</strong> environmentalterms, reduc<strong>in</strong>g nitrogen dioxide orparticulate pollution as a contributor to childhoodasthma) does noth<strong>in</strong>g to challenge exist<strong>in</strong>g powerstructures. However, strategic <strong>in</strong>terests (such aschalleng<strong>in</strong>g a society which values <strong>the</strong> machoimage of much car driv<strong>in</strong>g/ownership) take onexist<strong>in</strong>g patriarchal ‘paradigms of power’. Rai arguesthat an effective way of gender ma<strong>in</strong>stream<strong>in</strong>gwould be to frame women’s <strong>in</strong>terests (both practicaland strategic) <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> wider <strong>in</strong>terests of a justsociety ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> commonly adopted additivenature of gender analysis.The UN Conference on Environment andDevelopment (UNCED) <strong>in</strong> 1992 was <strong>the</strong> <strong>first</strong> UNconference to be significantly <strong>in</strong>formed by <strong>the</strong> nongovernmentalsector. Its centrepiece (or at least, <strong>the</strong>element that achieved <strong>the</strong> most publicity, and wasleast sca<strong>the</strong>d by <strong>the</strong> Rio +5 evaluation; see Osbornand Bigg 1998), Agenda 21, was a testament to <strong>the</strong>susta<strong>in</strong>ed lobby<strong>in</strong>g by women’s groups (as part of awider NGO presence, and local government). Thepreparatory meet<strong>in</strong>gs took place across <strong>the</strong> globe fortwo years and ensured a reasonably coherent lobbyfrom <strong>the</strong> women/environment movement worldwide,lead<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>clusion of a set of objectivesdef<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> Chapter 24 ‘Global action for womentowards susta<strong>in</strong>able development and equitable action’(United Nations 1992).The l<strong>in</strong>k between women and <strong>the</strong> environmentwas consolidated, <strong>in</strong>ternationally, at <strong>the</strong> 1995 4thUN Conference on Women <strong>in</strong> Beij<strong>in</strong>g. The result<strong>in</strong>gPlatform for Action identified ‘women and environment’as one of <strong>the</strong> critical areas of concern. UNED-UK’s ‘Gender 21’ group subdivided this concern<strong>in</strong>to education, health, marg<strong>in</strong>alized groups, plann<strong>in</strong>g,hous<strong>in</strong>g and transport, Local Agenda 21, andconsumption and waste (Barber et al. 1997).Ten years after UNCED, <strong>the</strong> World Summit onSusta<strong>in</strong>able Development (WSSD) did little toadvance women’s equality with respect to <strong>the</strong> environment,although <strong>the</strong> need to embed women’s(or sometimes termed ‘gendered’) concerns waswritten more thoroughly <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> Plan of Implementation.Few achievements were noted <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>terven<strong>in</strong>g ten years; for example, <strong>the</strong> UN hadexpressed frustration at <strong>the</strong> lack of progress onissues as wide as AIDS/HIV, globalization, poverty,and health – all of which are characterized bygender <strong>in</strong>equality.Po<strong>in</strong>t 20 of The Johannesburg Declaration onSusta<strong>in</strong>able Development commits to ensur<strong>in</strong>gthat ‘women’s empowerment and emancipation,and gender equality are <strong>in</strong>tegrated <strong>in</strong> all activitiesencompassed with<strong>in</strong> Agenda 21, The MillenniumDevelopment Goals and <strong>the</strong> Johannesburg Planof Implementation’ (Middleton and O’Keefe 2003).This plan variously refers to women, females,women and men, and gender, both generally (as<strong>in</strong> ‘<strong>the</strong> outcomes of <strong>the</strong> summit should benefitall, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g women . . .’), and with reference tospecific programmes. Such programmes <strong>in</strong>cludegood governance (item 4), poverty eradication (6),elim<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g violence (6), discrim<strong>in</strong>ation (6), health(6, 46, 47), economic opportunity (6), land ownership(10a), water (24), agriculture (38f), technology(49), energy (49), and area-specific programmessuch as mounta<strong>in</strong> areas and Africa (40c, 56). It alsoembeds gender considerations <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> means ofimplement<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Plan, such as education, datacollection, <strong>in</strong>dicator provision, public participationand decision mak<strong>in</strong>g. Such a thorough weav<strong>in</strong>g ofgender/women throughout <strong>the</strong> Plan of Implementationis, <strong>in</strong> some ways, an improvement on <strong>the</strong>targeted Chapter 24 focus<strong>in</strong>g on women <strong>in</strong> Agenda21, but it is too soon to establish whe<strong>the</strong>r it willhave any effect on signatory states’ treatment ofwomen, particularly <strong>in</strong> relation to <strong>the</strong> environment.Participants <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Women’s Platform at <strong>the</strong> NGOForum at <strong>the</strong> WSSD had mixed reactions: both welcom<strong>in</strong>ga more thoroughly embedded <strong>in</strong>clusion ofwomen <strong>in</strong> plans (Women’s Environment andDevelopment Organization 2002) and exasperationat <strong>the</strong> assumption <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> conference that‘women’s issues’ had already been dealt with atRio (Women’s Environmental Network/Women <strong>in</strong>Europe for a Common Future 2002). There is someevidence that <strong>the</strong> women’s groups were right tobe suspicious as, <strong>in</strong> preparation for <strong>the</strong> WSSD, <strong>the</strong>UN Commission for Susta<strong>in</strong>able Development, <strong>in</strong> its