Cimino&Ghiselin-tmpZXYZ:Template Proceedings_1.qxd.qxd

Cimino&Ghiselin-tmpZXYZ:Template Proceedings_1.qxd.qxd

Cimino&Ghiselin-tmpZXYZ:Template Proceedings_1.qxd.qxd

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

206 PROCEEDINGS OF THE CALIFORNIA ACADEMY OF SCIENCES<br />

Series 4, Volume 60, No. 10<br />

It would be fallacious to argue against the protective role of a metabolite on the grounds that<br />

the delivery system might be improved. The most effective arrangements must have been evolved<br />

over a long series of generations, and we would only expect to find intermediate stages in their<br />

elaboration. Likewise, one must not be misled by the fact that defensive metabolites are not completely<br />

effective against predators. We should expect them to reduce the amount of predation, and<br />

to occur together with other means of defense. The opisthobranch Oxynoe feeds upon the alga<br />

Caulerpa, and uses metabolites from it defensively. However, it is well camouflaged on the alga.<br />

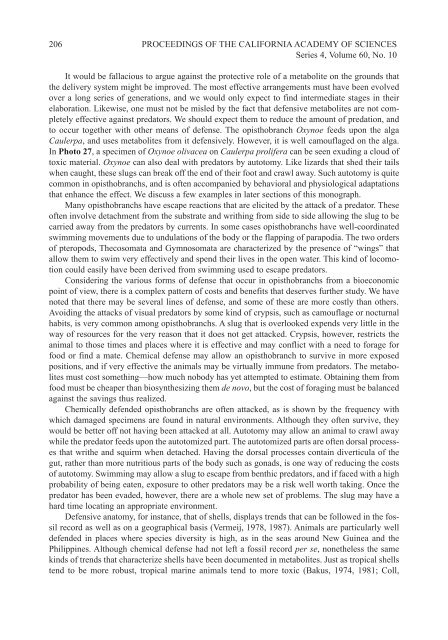

In Photo 27, a specimen of Oxynoe olivacea on Caulerpa prolifera can be seen exuding a cloud of<br />

toxic material. Oxynoe can also deal with predators by autotomy. Like lizards that shed their tails<br />

when caught, these slugs can break off the end of their foot and crawl away. Such autotomy is quite<br />

common in opisthobranchs, and is often accompanied by behavioral and physiological adaptations<br />

that enhance the effect. We discuss a few examples in later sections of this monograph.<br />

Many opisthobranchs have escape reactions that are elicited by the attack of a predator. These<br />

often involve detachment from the substrate and writhing from side to side allowing the slug to be<br />

carried away from the predators by currents. In some cases opisthobranchs have well-coordinated<br />

swimming movements due to undulations of the body or the flapping of parapodia. The two orders<br />

of pteropods, Thecosomata and Gymnosomata are characterized by the presence of “wings” that<br />

allow them to swim very effectively and spend their lives in the open water. This kind of locomotion<br />

could easily have been derived from swimming used to escape predators.<br />

Considering the various forms of defense that occur in opisthobranchs from a bioeconomic<br />

point of view, there is a complex pattern of costs and benefits that deserves further study. We have<br />

noted that there may be several lines of defense, and some of these are more costly than others.<br />

Avoiding the attacks of visual predators by some kind of crypsis, such as camouflage or nocturnal<br />

habits, is very common among opisthobranchs. A slug that is overlooked expends very little in the<br />

way of resources for the very reason that it does not get attacked. Crypsis, however, restricts the<br />

animal to those times and places where it is effective and may conflict with a need to forage for<br />

food or find a mate. Chemical defense may allow an opisthobranch to survive in more exposed<br />

positions, and if very effective the animals may be virtually immune from predators. The metabolites<br />

must cost something—how much nobody has yet attempted to estimate. Obtaining them from<br />

food must be cheaper than biosynthesizing them de novo, but the cost of foraging must be balanced<br />

against the savings thus realized.<br />

Chemically defended opisthobranchs are often attacked, as is shown by the frequency with<br />

which damaged specimens are found in natural environments. Although they often survive, they<br />

would be better off not having been attacked at all. Autotomy may allow an animal to crawl away<br />

while the predator feeds upon the autotomized part. The autotomized parts are often dorsal processes<br />

that writhe and squirm when detached. Having the dorsal processes contain diverticula of the<br />

gut, rather than more nutritious parts of the body such as gonads, is one way of reducing the costs<br />

of autotomy. Swimming may allow a slug to escape from benthic predators, and if faced with a high<br />

probability of being eaten, exposure to other predators may be a risk well worth taking. Once the<br />

predator has been evaded, however, there are a whole new set of problems. The slug may have a<br />

hard time locating an appropriate environment.<br />

Defensive anatomy, for instance, that of shells, displays trends that can be followed in the fossil<br />

record as well as on a geographical basis (Vermeij, 1978, 1987). Animals are particularly well<br />

defended in places where species diversity is high, as in the seas around New Guinea and the<br />

Philippines. Although chemical defense had not left a fossil record per se, nonetheless the same<br />

kinds of trends that characterize shells have been documented in metabolites. Just as tropical shells<br />

tend to be more robust, tropical marine animals tend to more toxic (Bakus, 1974, 1981; Coll,