Where Now for European Social Democracy? - Policy Network

Where Now for European Social Democracy? - Policy Network

Where Now for European Social Democracy? - Policy Network

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

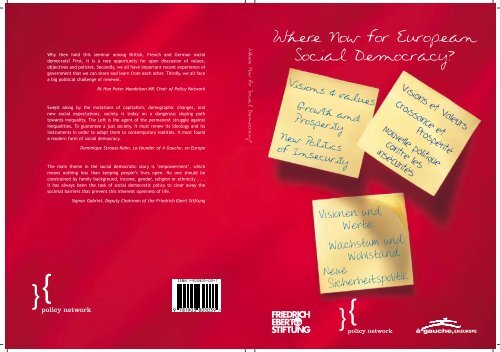

<strong>Where</strong> <strong>Now</strong> <strong>for</strong><strong>European</strong><strong>Social</strong> <strong>Democracy</strong>?

WHERE NOW FOREUROPEANSOCIAL DEMOCRACY?

Published in 2004 by <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Network</strong>info@policy-network.netwww.policy-network.netCopyright © 2004 <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Network</strong>All rights reservedISBN 0 1-903805-03-1 paperbackProduction & Print:Asset GraphicsDrury House, 34-43 Russell StreetLondon WC2B 5HA

<strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Network</strong> is an international think-tank launched in December2000 with the support of Tony Blair, Gerhard Schröder, GiulianoAmato and Göran Persson following the Progressive GovernanceSummits in New York, Florence and Berlin. <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Network</strong>’sobjective is the promotion and cross-fertilisation of progressivepolicy ideas among centre-left modernisers. <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Network</strong>facilitates dialogue between politicians, policy makers and expertsacross Europe and democratic countries around the world.The Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) is part of Germany’s system ofpolitical foundations. It is committed to the principles and basicvalues of social democracy, and operates in more than 100 countriesworldwide to provide a plat<strong>for</strong>m <strong>for</strong> debate on political and socioeconomicissues. The London office of the FES was established in1988 to foster dialogue and promote better understanding in British-German relations, mainly by means of seminars and reports onpolitical trends in both countries.The French organisation A gauche, en Europe was co-founded byDominique Strauss-Kahn (<strong>for</strong>mer French Minister <strong>for</strong> the Economy)and Michel Rocard (<strong>for</strong>mer French Prime Minister). It brings togetherindividuals from different political as well as cultural background,who all share the view that an intellectual renewal is necessary <strong>for</strong>the re<strong>for</strong>med Left and that such an ef<strong>for</strong>t only makes sense if itoccurs within a <strong>European</strong> perspective.v

AcknowledgementsThis collection of essays was prepared <strong>for</strong> a trilateral seminar on thefuture of social democracy co-organised by <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Network</strong>, theFriedrich-Ebert-Stiftung and A Gauche, en Europe. The event, heldin London on the 26th and 27th of February 2004, brings together 15progressive politicians, thinkers and policy-makers from each of thethree countries involved: France, Germany and the United Kingdom.We would like to thank Joanne Burton and Katerina Rudiger inthe <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Network</strong> office <strong>for</strong> their help in organising this event.David Levaï and Ruth Ziegler also deserve thanks <strong>for</strong> co-ordinatingthe visiting delegations from France and Germany respectively.We hope that this seminar will be the first of many similargatherings. The discussions triggered by the contributions containedin these pages should be considered the starting point of an ongoingdebate on the future of social democracy. We would like to thankthe authors <strong>for</strong> their commitment and interest in this project.Special thanks are also due to Francesca Sainsbury and NathanielCopsey, who tirelessly edited and translated the publication. Withouttheir dedication this pamphlet would never have been possible.Matt Browne, Director of <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Network</strong>Olivier Ferrand, Secretary General of A Gauche, en EuropeFrançois Lafond, Deputy Director of <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Network</strong>Gero Maass, Director of the London Office of theFriedrich-Ebert-StiftungLondon, February, 2004vii

ContentsAcknowledgementsviiNotes on the Contributors 1Preface 3Tony BlairIntroduction 5Peter MandelsonVisions and ValuesWhat is a just society? 11Dominique Strauss-KahnRediscovering the need <strong>for</strong> vision 23Sigmar GabrielPermanent re<strong>for</strong>mism: the social democratic challenge of the future? 31Patrick DiamondGrowth and ProsperityIs the Lisbon process lost? 43Angelica Schwall-DürenGrowth policies <strong>for</strong> Europe: Is there a common social democratic agenda? 49Jean Pisani-FerryLisbon: A missed opportunity <strong>for</strong> <strong>European</strong> social democracy 57Roger LiddleThe New Politics of InsecurityThe place of security in progressive politics 75David BlunkettFreedom in security: A social democratic vision 85Brigitte Zypries<strong>Social</strong> insecurities 93Marisol TouraineEndnotes 101ix

Notes on the ContributorsTony Blair is the British Prime Minister.David Blunkett is the UK Home Secretary. Previously, Mr Blunkett(1994) was appointed as Shadow Secretary of State <strong>for</strong> Education,and in 1995 this position was expanded to include employment aswell as education. In May 1997 Mr Blunkett was appointed to theCabinet in the post of Secretary of State <strong>for</strong> Education andEmployment.Patrick Diamond is a Special Adviser in the UK Prime Minister's <strong>Policy</strong>Directorate. He was <strong>for</strong>mally a Special Adviser at the NorthernIreland Office. He writes here in a personal capacity.Sigmar Gabriel has been a Member of the Land Parliament of LowerSaxony since 1990. He leads the SPD group in the Land Parliamentand was Prime Minister of Lower-Saxony (1999-2003). He is amember of the National Executive Committee of the SPD and alsoDeputy Chairman of the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.Roger Liddle is Special Adviser to Prime Minister Tony Blair on<strong>European</strong> Affairs and writes here in a personal capacity.Peter Mandelson is Chair of <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Network</strong> and has been theMember of Parliament <strong>for</strong> Hartlepool since 1992. He was <strong>for</strong>merlySecretary of State both <strong>for</strong> Northern Ireland, and <strong>for</strong> Trade andIndustry.Jean Pisani-Ferry is Professor at the Université Paris-Dauphine. Heis a member of the Conseil d’analyse économique. He was co-authorof the Sapir report from the High-Level Study Group appointed byRomano Prodi in 2003.1

2WHERE NOW FOR EUROPEAN SOCIAL DEMOCRACY?Angelica Schwall-Düren has been a Member of the Bundestag<strong>for</strong> Münsterland (Nordrhein-Westfalen) since 1994 and DeputyChairwoman of the SPD group in the Bundestag (on <strong>European</strong> Affairs)and a member of the National Executive Committee of the SPDsince 2002.Dominique Strauss-Kahn is the <strong>for</strong>mer Minister <strong>for</strong> Economy,Finance and Industry (1997-1999). He was also Minister <strong>for</strong> Trade andIndustry (1991-1993).Marisol Touraine is the national Secretary <strong>for</strong> Solidarité at theParti <strong>Social</strong>iste. Previously, she was a Member of Parliament <strong>for</strong> theIndre-et-Loire constituency (1997-2002).Brigitte Zypries has been the Federal Minister of Justice sinceOctober 2002. Previously she was Director General in the StateChancellory of Lower Saxony (1995 to 1997) and State Secretary inthe Federal Ministry of the Interior (1998-2002).

PrefaceTONY BLAIRI welcome this publication that marks the occasion of an important <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Network</strong>seminar bringing together leading British, French and German social democrats.<strong>European</strong>s are right to celebrate their diversity. There is no uni<strong>for</strong>m <strong>European</strong>model of market capitalism; no identical social system. Within Europe, even withinthe EU 15 and the eurozone, there are wide differences of economic per<strong>for</strong>manceand social outcome. But <strong>European</strong>s still have a lot to learn from each other. SinceNew Labour came to power in 1997, Britain has done well in terms of growth andemployment. We are catching up on productivity, but despite the sustainedprogramme of investment this government has put in place, there is still some wayto go be<strong>for</strong>e Britain matches the high-quality public services that many of our<strong>European</strong> partners enjoy. Despite our impressive record in tackling child poverty,Britain is still scarred by a legacy of inequality and social exclusion which, on theContinent, is much less pronounced. This is the ‘progressive deficit’ that is NewLabour’s driving mission to overcome.So, we welcome fellow progressives to London to debate the challenges thatface us. In or out of office, social democrats have always sought to devise agoverning strategy that combines economic dynamism with social cohesion. For weknow that, unless we master the politics of production, the politics of equalitybecome impossibly difficult.In today’s world, that means devising a politics of production that is equal tothe challenges of competitiveness in a world where China is emerging as a majorindustrial power and India as a successful international service economy. It meansensuring greater investment in knowledge (where, in research and higher education,Europe, as a whole, is lagging woefully behind the United States) and strengthenedinnovation capacity. And it means modernising our Welfare States and labourmarkets not simply to cope with the realities of demography, life expectancy andchanges in family life, but also with the demands of a different type of advancedeconomy.As social democrats from Britain, France and Germany, we face these commonchallenges on the basis of shared values of social justice and genuine opportunity<strong>for</strong> all. Our parties have proud histories. As a result, there is always a tendency tolook to the great days of our parties’ golden age: Willy Brandt’s championing ofOstpolitik; the achievements of the Popular Front in France; and the creation of theWelfare State under the Attlee Government in Britain.But our values do not belong to the past. They are the basis <strong>for</strong> facing thechallenges of social justice today and we have to be tough-minded with ourselves inapplying those values to present-day problems. That is why this common progressivedialogue really matters.3

INTRODUCTION<strong>Where</strong> <strong>Now</strong> <strong>for</strong><strong>European</strong> <strong>Social</strong> <strong>Democracy</strong>?PETER MANDELSONThe publication of this book of essays marks the occasion of a seminarin London of British, French and German social democrats to discussthe way ahead <strong>for</strong> social democracy.The seminar is an in<strong>for</strong>mal gathering, not a meeting of Partyrepresentatives. It has no official status. But it is, nevertheless, animportant event. I cannot think of anything similar that has happenedin my 20 years experience that has involved senior members of theBritish Labour Party.There is a paradox here. Politicians talk very little about politics topoliticians in other <strong>European</strong> countries. Yet integration is a centralreality of all our political lives. Economically, what happens in Franceand Germany impacts greatly on Britain, and vice-versa, becausewell over half our trade is with the <strong>European</strong> Union. I read a paperprepared <strong>for</strong> a recent international conference that the Chancellorof the Exchequer, Gordon Brown, hosted in London on enterprise: itcontained the statement that 50 per cent of the regulation affectingbusiness, and thereby jobs and prosperity, is now decided upon by the<strong>European</strong> Union.Yet <strong>for</strong> all the realities of integration and interdependence,political dialogue is, at best, weak. Of course, there are intensiverelations between the governments of Europe, whatever their politicalcolour. National civil servants, across a wide range of departments, arein constant touch, bilaterally and in hundreds of official workinggroups that meet in Brussels, to crawl over technical dossiers. Ministerscome together more intermittently at Councils and bilateral meetings,but often to debate an agenda that reflects a pre-set national positionon issues that have been ‘in the system’ <strong>for</strong> some considerable time.5

6WHERE NOW FOR EUROPEAN SOCIAL DEMOCRACY?As politicians, they often feel locked in and frustrated by the lack ofopen dialogue on the ‘real issues’ that we share in common.There are fledgling <strong>European</strong> political parties. The Party of<strong>European</strong> <strong>Social</strong>ists does provide a useful <strong>for</strong>um <strong>for</strong> mutual contact.The recent report 1 on globalization prepared by a working groupchaired by Poul Nyrup Rasmussen, the <strong>for</strong>mer Danish Prime Minister,is, <strong>for</strong> instance, admirable in its content and wisdom.But the main focus of the PES ef<strong>for</strong>t has understandably been the<strong>European</strong> Parliament. MEPs have played a considerable part in itswork. Dialogue between members of national political parties is muchrarer and suffers from the problem of every representativeorganisation that every affiliate demands the right to be represented.Practical constraints mean that in the new EU of 25, intimate dialoguewill have to proceed on an in<strong>for</strong>mal basis between self selectinggroups.Why then hold this seminar among British, French and Germansocial democrats? First, it is a rare opportunity <strong>for</strong> open discussion ofvalues, objectives and policies. Secondly, we all have important recentexperience of government that we can share and learn from eachother. Thirdly, we all face a big political challenge of renewal.In Britain, we have started to look <strong>for</strong>ward to an unprecedentedthird term. In the post-Hutton, post-tuition fees climate of opinion,the challenge is to re-engage the Party in a bold agenda of re<strong>for</strong>m sothat New Labour can govern with confidence, rather than relapse intoa mind-set of cautious consolidation.In Germany, the SPD spent 2003 coming to terms with thechallenge of the Schröder Government’s Agenda 2010, includingpainful and difficult Welfare State and labour market re<strong>for</strong>ms. 2004began with the SPD promulgating a bold agenda on innovation withhope of lifting the Party’s <strong>for</strong>tunes as the year progresses and economicrecovery takes hold.In France, the Parti <strong>Social</strong>iste is coming up to the secondanniversary of Jospin’s third place in the first round of the Presidentialelections. Despite growing problems <strong>for</strong> the centre-right government,it still needs to show fresh unity of purpose and ideological renewal tobecome a credible challenger <strong>for</strong> power.

VisionsandValues

What is a just society?For a radical re<strong>for</strong>mismDOMINIQUE STRAUSS-KAHNWhat is a just society? This question is at the heart of our socialistidentity, and the source of our values as men and women of the Left.The search <strong>for</strong> social justice, <strong>for</strong> equality between citizens, and <strong>for</strong>collective solidarity constitutes the principal objective of the <strong>European</strong>social democratic project.But the world has changed. Collective values are evolving.Capitalism is undergoing a profound period of change. The traditionalWelfare State, the providential state, is in crisis. The internationalcontext is in the process of a radical redefinition of its post-Cold Waridentity, in which the September 11th, 2001 attacks are a key element.The world has changed. However, our political agenda hasremained the same. It remains anchored in the doctrine of traditionalpost-1945 social democracy.Our responses to this new order must evolve. To achieve itsobjective of social justice, twentieth century social democracy had aprogramme adapted to the rhythm of its times. To achieve the sameobjectives, socialists today must renew our ideological corpus. Wemust launch a new age of social democracy.In our traditional political vision, a just society is a society foundedon redistribution. Capitalism produces inequalities, and the role ofsocial democracy is to correct these inequalities, by redistributing theprofits of the economic machine to those who have not benefited, orto those who have been its victims.This is what all social democrats have done since the Second WorldWar, in building the Welfare State. This model emerged from a virtuouscircle between production and redistribution: strong growth allowedthe financing of redistribution, which in turn, supported consumption11

DOMINIQUE STRAUSS-KAHN 13the distance between the successful and everyone else.• Capitalism was standardised; it has become ‘post-Fordist’. Fordistcapitalism was based on the model of the large industrialenterprise and strong class identities. The standardisation of tasksalong a chain, and there<strong>for</strong>e the common interest of those whoworked along it permitted a sense of rapport between employersand the workers’ representatives. Employees had clear rights, withequal conditions of work <strong>for</strong> all. The modern economy, founded onthe differentiation between tasks, flexibility, and direct relationswith the client, has called the Fordist model into question. Largeenterprises have disappeared to the benefit of more atomisedunits, class barriers have broken down, and jobs have becomemore individualised. The result of this evolution is that theemployees’ rights have been eroded, they have been put intocompetition with each other, and paid according to theirper<strong>for</strong>mance. As a corollary of this, inequalities in pay are rising.• Capitalism was national; it has become global. Globalization hasenlarged the salary range. Globalization weighs heavily onrevenues, and especially the salaries of the least qualifiedemployees in Western countries, who have to compete with thelow salaries of developing countries. Waves of delocalisation andrapid deindustrialisation in Europe – at least of labour intensiveindustries – bear witness to the gloomy effects of globalization.At the other end of the scale, globalization increases the value ofthe new cadre of international executives, whose function is toorganise the nomadic nature of business. This group is rewardedwith stock options, bonuses and so on.The redistributive capacity of the Welfare State has diminishedWith the growth of inequalities caused by the market, the need <strong>for</strong>redistribution has grown, if we wish to maintain a just society. TheWelfare State has come under attack on three fronts: ideological,demographic, and economic.The liberal ideology has won hearts and minds. It seems tocriticise redistribution as being harmful to growth. Redistribution

14WHERE NOW FOR EUROPEAN SOCIAL DEMOCRACY?might suppress the spirit of enterprise. It creates a benefits culture,and puts a break on the return to work of the unemployed. It increasesthe costs of production and limits the profitability of businesses, andconsequently the level of investment.Demographic evolution threatens the providential state. This is theresult of a fall in the number of people who contribute to the socialstate and a rise in those who benefit from state assistance. In France,until the end of the twentieth century, there were once three activeworkers <strong>for</strong> every pensioner. By 2020, there will only be one worker <strong>for</strong>every pensioner. The growth in life expectancy has been coupled witha huge rise in health spending, especially on those dependent and atthe very end of their lives.Economic globalization produces a tension between growth andredistribution, which threatens the Welfare State. The success of postwarsocial democracy rests on the equilibrium between productionand redistribution, regulated by the state. With globalization, thisequilibrium is broken. Capital has become mobile: production hasmoved beyond national borders, and thus outside the remit of stateredistribution. Production thus depends on attracting internationalinvestment. For strong liberals welfare spending detracts from astate’s attraction as a destination <strong>for</strong> mobile capital: to achievegrowth, the Welfare State would have to be sacrificed. Growthwould oppose redistribution; the virtuous circle would become avicious circle.The providential state has there<strong>for</strong>e been shaken. In theseconditions, the risk is strong that it will no longer be able to controlthe growth of inequalities. Even worse, its disengagement at theprecise moment when the mutations of capitalism are causing thegrowth of inequality, could lead the machinery of inequality to spinout of control. This is the case in the United States: over the past20 years, the richest one per cent have increased their share ofnational wealth from eight per cent to 14 per cent, close to the1900 level of 18 per cent. Even if nothing is done, Europe couldfollow the same path.

DOMINIQUE STRAUSS-KAHN 15<strong>Social</strong> expectations of the Welfare State have evolvedIn traditional social democracy, social expectations were at firstcollective: to improve the condition of the working class, and to betterredistribute the profits of labour. Today, our societies are expressing astrong demand <strong>for</strong> individual promotion. This is explained by anevolution of collective values: the growth of individualism, aspirations,and a stronger desire <strong>for</strong> personal accomplishment – and its rewards.This is further explained by the evolution of post-Fordist capitalism.Yesterday, workers were ensnared by a social class that woulddetermine their individual destinies. Today, with the decline of theidea of class, and the enfeeblement of collective identity, eachindividual plays their own hand. Everyone is responsible <strong>for</strong> theirprofessional development, <strong>for</strong> his or her success or failure. This isexplained by the democratisation of education, a very recent process. InFrance, between 1987 and 1997, the median age <strong>for</strong> finishing educationpassed from 19 to 22 years of age; the number of those with a bachelor’sdegree has more than doubled from 30 per cent to 63 per cent.These expectations of individual success and social promotion aredeceptive. <strong>Social</strong> mobility is feeble in our societies: inequalities ofdestiny are vast. Statistics show an unbelievable stability in thereproduction of inequalities. Intergenerational inequalities aregrowing: social mobility is even weaker, the chances that a worker’schild will become an executive are still slim. <strong>Social</strong> mobility is evenweaker than it was in the past: in 1960, a French worker could expectto attain the salary of an executive in 30 years; today it would take 150... Contemporary society has a less justifiable level of inequality thanduring the middle of the twentieth century. Today’s discourse createsterrible frustration because it leads us to believe that all responsibilityis personal, in other words: if you fail, it’s your own fault. Classconsciousness is disappearing and the social structures that went withit are fading. Since the democratisation of education has mostbenefited families of modest means, it is this group who will suffermost from disillusionment.The Welfare State responds badly to the new social expectations.It was constructed to regulate the relations between classes. It rests

16WHERE NOW FOR EUROPEAN SOCIAL DEMOCRACY?on the reparation of the injustices of capitalism meted out to thepopular classes. Its message was: “You have nothing to expect from thecapitalist – you will always be the losers. There’s nothing you can doabout it; the popular classes are always exploited by the dominantclasses. Only the social democratic state is able to correct theinequalities that you suffer”. This is why the social democraticprovidential state created a system to deal with injustices ex post. Themarket produced inequalities which the state then corrected, aposteriori. But contemporary society has liberated individuals from thefatal embrace of class. Our fellow citizens thirst <strong>for</strong> personal success.They say to us: “Do not interest yourselves only in providing a measureof security <strong>for</strong> us in case of set backs, give us also the means tosucceed. Give everyone a real equality of opportunity”. It is thisdemand that we must address.Swept along by the mutations of capitalism, demographic changes,and new social expectations, society is today on a dangerous slopingpath towards inequality. The Left is the agent of the permanentstruggle against inequalities. To guarantee a just society, it must renewits ideology and its instruments in order to adapt them tocontemporary realities. It must found a modern <strong>for</strong>m of socialdemocracy.In order to do this, I propose a three-pronged vision of socialism:redistributive socialism; socialism of production; and empoweringsocialism. This vision should take material <strong>for</strong>m in a new area ofregulation: Europe.Faced with the growth of market inequalities,‘redistributive socialism’ must be strengthenedThe historic programme of social democracy is redistribution. We mustnot flinch from this task at the precise moment when the market isincreasing inegalitarian pressures. On the contrary we must make thesystem more redistributive: it is imperative if we want to stabilise thegap in disposable income between the richest and the poorest,because at the same time the difference in incomes increases evenbe<strong>for</strong>e redistribution.

DOMINIQUE STRAUSS-KAHN 17Confronted with constraints that are affecting our redistributivecapacity, the Welfare State needs profound and courageous re<strong>for</strong>ms.I wish to sketch out two courses:• Increase the efficiency of the redistributive system. In all countriesthere is a margin <strong>for</strong> manoeuvre. This is particularly true <strong>for</strong>France. We have certainly created a machine that redistributeshalf of national income. But it does this poorly: despite thisglobally huge volume, our taxes contribute little to the correctionof inequalities. The overall demands made on physical persons areabout the same at every end of the pay scale, both <strong>for</strong> executivesand the ordinary employee – that is, deductions amount to50 per cent to 60 per cent of gross income. If we were able toaccommodate this in the 30-year post-war boom, it is no longer thecase today. This is why a vast reconsideration of our whole taxsystem is needed, in the wider perspective of a global planwhich will encompass all instruments and allow us to find anoverall coherence.• Re<strong>for</strong>m whilst protecting existing rights. The re<strong>for</strong>m of our WelfareStates is necessary, as a result of, amongst other things, thedemographic evolutions currently underway. Those who sayotherwise and pretend the system can avoid re<strong>for</strong>m aredemagogues. But the re<strong>for</strong>ms that have been carried out byconservative administrations in Europe, and in particularly inFrance, are shocking. They threaten the fundamental rights andrupture the implicit tie between the state and its citizens. Let usconsider the case of the French civil service. Those who enter theadministration do so on the basis of an implicit contract: on theone hand, salaries are worse than in the private sector; on theother hand, jobs are safer and pensions much better. If civilservants are deprived of these and conditions aligned with theprivate sector, the contract is broken. This is even worse if thecontract has been long term, in some cases an individual’s entireworking life. That re<strong>for</strong>m is necessary is incontestable, but it isquite simple if it only concerns new entrants into the civil service:everyone should decide if he or she wishes to enter public serviceunder the new conditions. It is more complex if it also concerns

18WHERE NOW FOR EUROPEAN SOCIAL DEMOCRACY?civil servants already in post. It would be unfair if the re<strong>for</strong>m wereretroactive on citizens, who in other circumstances would havemade different career choices. This is why re<strong>for</strong>ms must recogniserights acquired in the past: this should be taken into considerationby an indemnity to protect existing rights. It is under this conditionthat re<strong>for</strong>ms of our Welfare State, unpleasant although necessary,will respect the objective of social justice.To regulate modern capitalism and <strong>for</strong>bid the proliferation ofinequalities, we have to develop a ‘socialism of production’We can no longer watch passively as the market creates inequalitiesand correct them afterwards. Inequalities grow, and in certain cases,they can become psychologically unacceptable and cause resentment.That is why we can no longer allow the market to generate theseinequalities: we must attack them at the root, and intervene in thesystem of production. We, as socialists, have too long hesitated to dothis: in the name of maximising ideology we have <strong>for</strong>bidden ourselvesfrom re<strong>for</strong>ming the capitalist machine from the inside. This has beenthe case in several <strong>European</strong> countries, particularly in Latin countries,where any attempt at re<strong>for</strong>m has been seen as a betrayal of theworking class. In such circumstances the Left remains inert. “Theyhave clean hands, but they don’t have hands”, as Péguy remarked. Toorganise the ‘socialism of production’, is to accept getting ourhands dirty.This ‘socialism of production’ has a fecundity of directions:corporate governance, regulation of financial markets, and thesupervision of delocalisation ... I wish quite simply to insist on onepoint: to secure the worker over the course of their life, also known asprofessional social security.Since capital has become ultra-mobile, because industrial sites candelocalise more easily, because companies rise and fall more quickly,linear careers in one organisation have disappeared. Everyone nowchanges not only company several times in their life, but also theircareer. However, workers are in a fundamentally inegalitarian positionas a result of these changes. The highly skilled part of the work<strong>for</strong>ce

DOMINIQUE STRAUSS-KAHN 19has qualifications that make them attractive to new employers.Indeed, these professional changes are often an opportunity <strong>for</strong> themto accelerate their professional development, renegotiating theirresponsibilities and their salaries. The poorly qualified worker has onlythe internal recognition of the quality of his or her work in a particularcompany. This recognition cannot be redeemed to impress a futureemployer: he or she is condemned to be unemployed, or at best, tobegin again from nothing. For the unskilled worker, professionalchange is a rupture, sometimes definitive, in his or her career.One must take charge of this rupture and guarantee the period oftransition between losing one job and finding another. In La Flamme etla Cendre, 2 I call this the mutualisation of the risks of professionalmobility. In the past, with professional rights, it was the job that wasprotected. It should be the individual that is protected, not the job.The practical solutions are obviously the most difficult to put intopractice: this is a new social right. We must build a real ‘professionalsocial security’. We <strong>European</strong> social democrats must all work togetherwith our social partners to accomplish this.To create real equality of opportunity, and a guarantee of socialpromotion <strong>for</strong> all, we must invent ‘empowering socialism’Intervening at the heart of the system of production to limitinequalities is not enough. We must also intervene further upstream,since we have seen that ordinary citizens do not have the means toensure their professional success. There are intelligent workers andchildren in both rich communities and in deprived neighbourhoods.Nonetheless, statistically, the <strong>for</strong>mer succeed, and the latter fail.‘Personal capital’, that is to say individual origins and their visiblesigns – if one is black, white or brown – the family context , and thesocial-urban environment all determine personal accomplishment.From this point of view, the market does not create new inequalities –it makes them apparent. It simply continues, in terms of financial andprofessional success the inequalities of the cradle.This is why I propose the construction of an ‘empowering socialism’to allow the reality of social mobility. This rests on two principles.

20WHERE NOW FOR EUROPEAN SOCIAL DEMOCRACY?In the first place, the correction of inequalities at an earlier stage.We must leave behind the old idea of correcting inequalities a postieri– the logic of the old Welfare State – and correct inequalities a priori.Second principle, the concentration of public resources. The objectiveof an empowering socialism is to guarantee to everyone a real equalityof opportunity. Not just a simple equality guaranteed by law: ‘you allhave the same rights, competition is open, so may the best man win!’But a real equality. In order to do this, we have to give more to thosewho have the least – more public services to those who have lessnatural capital.This approach is a return to the origins of socialism, and theempowerment of the citizen. It opens the perspective of radicalre<strong>for</strong>m in our public services which are the principal guarantors ofequality of opportunity: childcare, education, housing, urban renewaland integration ...I only want to take a single example, schooling. Today in France,in the name of republican equality, we offer in principle the sameeducation to all our children: the same course, the same subjects, thesame number of hours of tuition <strong>for</strong> all. This is not true in practice: theschools in deprived neighbourhoods are far less well kept because thelocal councils are much poorer, the teachers are of a poorer quality,since they remain in post <strong>for</strong> a much shorter period. Even if theprinciple of <strong>for</strong>mal equality were respected, it would still be a falseequality, since schools are so egalitarian they reproduce and legitimiseexisting inequalities of opportunity. We must break with this <strong>for</strong>malequality and concentrate our resources on those who need them most,to ensure a true equality of opportunity. If a child needs 30 hours oftuition to learn mathematics instead of the 20 <strong>for</strong>mally allotted by thetimetable, the school should be able to provide them. We must givemore to those pupils who have the most need.Modern social democracy must re-define the territory ofregulation and invest in the <strong>European</strong> fieldThe Welfare State is enfeebled because it no longer operates on themost pertinent territory. Capital has become mobile, and can easily

DOMINIQUE STRAUSS-KAHN 21avoid national regulation by delocalising. The territory of politicalregulation should become again the same as that of economics. Theglobalization of regulation should follow the globalization of theeconomy. In order to do this, we must put all our energy into theconstruction of Europe, which is alone in possessing the clout tobring about global regulation, partly through the construction ofinternational institutions. The state was the instrument of twentiethcentury social democracy. Europe should be our new horizon, and thelever of tomorrow’s social democracy.In this perspective, the current debates on the <strong>European</strong>Constitution are essential. ‘Technical Europe’, the entity that hascome into being since the Treaty of Rome in 1957, has been aremarkable instrument <strong>for</strong> the construction of the Single <strong>European</strong>Market. But it does not facilitate the construction of a socialdemocratic programme <strong>for</strong> Europe. This is, by definition, a politicalambition – and political institutions alone, responsible to <strong>European</strong>citizens, can put this into place. Whatever its weaknesses, the<strong>European</strong> Constitution marks the first founding step towards thispolitical Europe. It is urgent that all the <strong>European</strong> parties of the Leftmobilise to push <strong>for</strong> its adoption.We live in a period of transition towards a new political cycle. Onepolitical cycle is coming to a close: post-war social democracy. A newcycle is under construction: social democracy <strong>for</strong> the twenty-firstcentury.The world has changed – our political framework cannot remain thesame, anchored in the doctrine inherited from the Second World War.We are in ideological retreat; we are out of step with the politicaldemands of our fellow citizens, whom we offer policies that are notadapted to the rhythm of our times. This is the origin of the presentdemocratic crisis.This crisis is a fact, but it is not terminal. We have to respond tothe democratic challenge and work to rebuild our intellectualfoundations. We have to create a political project adapted to themutations of modernity, a vision of society capable of offering the keyto the future, a new identity that can face up to the fall of the oldcollective remedies. This perspective rejects the passive response to

22WHERE NOW FOR EUROPEAN SOCIAL DEMOCRACY?current trans<strong>for</strong>mations. Left re<strong>for</strong>mism is not an abdication be<strong>for</strong>ethe market, it is on the contrary a constituent part of a radicalre<strong>for</strong>mism, capable of changing the course of the world.This is the collective ambition that we must fix ourselves upon.

Rediscovering theNeed <strong>for</strong> VisionSIGMAR GABRIELIn recent months, wherever German social democrats meet to discussthe state of our party and its government’s policy, we hear thissentence resounding like a short, fervent prayer. Whenever the SPD isin government many party members wonder if and how the politicsof the day can be brought into alignment with the historic mission ofthe SPD.The on-going discussion over a new SPD policy agenda should helpto satisfy this longing <strong>for</strong> a modernised social democratic narrative.However, if one listens closely a ‘secret course of instruction’ in thepolicy debate is also revealed: some suggest that in view of thedifficult decisions of Agenda 2010 they are able to pacify thesomewhat unwieldy and disgruntled political grass roots – cynics evenclaim they are able to keep them occupied. Others hope that througha new social democratic ‘vision’ they are simply better able to explainthe harsh realities of government policy.Others simply want to escape from this severe government policy.Based on the motto: if we already feel very uneasy when consideringthe difficult decisions associated with Chancellor and – at least untilrecently – Party Chairman Gerhard Schröder’s Agenda 2010, then wewant to at least play a neutral role in the policy debate of the SPD.The SPD’s regenerative energy source:freedom and empowermentNothing would be worse than following this ‘secret course ofinstruction’. It is correct that the SPD is a party that needs a surplusof hope and utopia in order to engage people <strong>for</strong> longer than just the23

24WHERE NOW FOR EUROPEAN SOCIAL DEMOCRACY?brief moment of a singular electoral decision. In its 140-year history,the SPD has experienced and survived enormous historical breaksin Germany. Charismatic personalities, or savvy re<strong>for</strong>m projects andlegislative plans do not suffice to explain why this party has survived<strong>for</strong> so long and even remained young and attractive: through the daysof empire, to the Weimar Republic and National <strong>Social</strong>ism and againstthe lively antithesis of Communism. Even the visible eclipse of ourhistorical sister movement – the labour movement – which has beentaking place <strong>for</strong> decades, has not changed this.The SPD’s fountain of youth was and is the main theme in thesocial democratic story. Its central idea is ‘empowerment’, whichmeans nothing less than keeping people’s lives open. No one shouldbe constrained by family background, income, gender, religion orethnicity. And it has always been the task of social democratic policyto clear away the societal barriers that prevent this inherent opennessof life. <strong>Where</strong> hurdles obstruct this openness in the life course, socialdemocrats want to train the muscles of every individual to enablethem to jump over them. We want to achieve this particularly throughgood education and vocational training. <strong>Where</strong> the social barriers aretoo high <strong>for</strong> even the strongest muscles, we want to work together topull down these barriers.There<strong>for</strong>e, freedom is not only a collective goal of socialdemocracy in building a democratic society – but also always a centralcategory <strong>for</strong> the blueprint of life of every individual. We want toensure life chances <strong>for</strong> all, from the outset, to take part in theopportunities of their society. In order to achieve that, a responsibility<strong>for</strong> communal life has to be a part of the right to individual freedom.For social democracy, freedom and autonomy on the one hand, andpublic welfare and social responsibility on the other, were always twosides of the same coin. The combination of these, along with thenotion of empowerment and of ‘another’ life <strong>for</strong> every individual in‘another’ society that developed from this were the regenerativesource of energy that has been the SPD’s driving <strong>for</strong>ce <strong>for</strong> more than140 years.

SIGMAR GABRIEL 25The task of the SPD remains:strengthening people and opening pathsToday, what is the meaning of freedom, justice and solidarity ina modern society considering the dramatic change in the economy,social structure and demographic developments? 140 years ago,when members of craft guilds and workers organised, freedom andjustice were existential values in a society that prevented theirimplementation to a great extent. Solidarity was then a merit that wasfirst and <strong>for</strong>emost practiced daily by the labour movement throughself-organisation, because Imperial Germany did not want to grantsolidarity to the workers. In the last 140 years, social democrats havelaboriously struggled, at times bitterly, <strong>for</strong> a high degree of freedom,justice and solidarity. However, no one will deny that today theGerman social state is arranged fundamentally differently than theclass-based society of 1863. This is precisely because of socialdemocracy, which has throughout the years achieved significantchanges and improvements <strong>for</strong> people and their co-existence.In our modern society there are also barriers <strong>for</strong> the personalopportunities of the individual as well as <strong>for</strong> societal developments:educational opportunities continue to be strongly linked to socialinheritance; children are a poverty risk <strong>for</strong> families; bringing upchildren can be incompatible with having a job; increasing massunemployment; the recurrent failure to integrate <strong>for</strong>eigners andre-settlers; and, the decreasing ability of our cities to create socialintegration, to list just some of the problems. It is precisely thetraditional voter groups of the SPD who increasingly feel that we areno longer sufficiently aware of these barriers and the everydayconcerns. Young families that can only af<strong>for</strong>d children or holidays, thetechnician or engineer who at the age of 50 can no longer findemployment, the craftsman who must spend 10 per cent of his netincome on nursery school spaces <strong>for</strong> his two children or the pensionerwho has not moved in 30 years, but in the meantime no longer feels athome, 70 per cent of those living in his part of town now being <strong>for</strong>eigners.Thus there are enough tasks <strong>for</strong> a party that has devoted itself tothe principle capability of emancipating the individual and society.

26WHERE NOW FOR EUROPEAN SOCIAL DEMOCRACY?In addition it is a good social democratic tradition to not only care<strong>for</strong> national – or today <strong>European</strong> – tasks, but at the same time alsoincrease awareness <strong>for</strong> people living together at the internationallevel. Starvation, environmental catastrophes or violent conflicts arebound inseparably to the environmental and social conditions ofdeveloped industrial nations and are a worldwide challenge <strong>for</strong> socialdemocratic policy.The new tasks <strong>for</strong> the SPDThere are, however, great differences between the empowering contentof social democratic policy of 20 or 30 years ago and that of today. Oneimportant difference lies in the historic success of social democracy initself. This success has not only led to the disbanding of the classicsocial democratic environment, but also the opinion <strong>for</strong>mers, electedofficials and functionaries of the SPD are now further removed fromthe conflict-laden daily experiences of traditional SPD voters.In the past, social democratic municipal council members werein<strong>for</strong>med of conflicts through their involvement in sports clubs, inschool parents’ councils or in workers’ councils. Today, in many citiesthey perhaps attend the respective annual general meeting but live ina sphere that is otherwise disconnected. The consequence of this is notonly a lack of mutual commitments, but also in part the denial ofexisting conflicts that do not suit particular political positions. Thisis most noticeable time and again in the fear-laden inner-partydiscussions over the real, existing conflicts between Germans and<strong>for</strong>eigners.There<strong>for</strong>e, the SPD must urgently change the social structure of itsmembers, functionaries and elected officials. This requires not justrejuvenation. Most importantly, it must also be extended to theeveryday experiences in occupational and social life. In <strong>for</strong>mer timesthere was a lack of women in the SPD, and now in addition there is alsoa lack of skilled workers, craftsmen, technicians, nurses, policemen,workers’ councils and the self-employed. In essence, the purpose isto bring together as many different experiences and viewpoints aspossible to confront one another in the SPD. Only in this way can

SIGMAR GABRIEL 27exciting discussions and reasonably sure-footed decisions emerge.The second main, important difference in a new policy concept <strong>for</strong>German (and international) social democracy is that the classicalstrategy of re-allocating social wealth no longer reaches out enough toremove the social barriers that exist in today’s world.On the contrary, the structures and systems of social securitybuilt on this strategy have in themselves become an obstacle to anempowering development <strong>for</strong> many people in our society. On the onehand we have been living <strong>for</strong> decades by mortgaging the future,because the political class’ strategy of conflict avoidance – includingsocial democrats – has increasingly financed its social programmesthrough borrowing. A completely different redistribution has arisen,namely <strong>for</strong> the benefit of those who are living at the expense of futuregenerations.Today, the result of this already is that we are confined to copingwith the past and we are not free to act <strong>for</strong> the future. In Germany,we spend each year €114 billion on debt-servicing and pensions andonly €25 billion on investment. For research and technology, only€12 billion are allotted in the federal budget. A society that spendsten times more on managing the past than it does <strong>for</strong> the future isquickly a thing of the past.On the other hand, the combination of a hedonistic policy on thefamily and the lack of childcare options has led all the <strong>for</strong>mulas of oursocial security system to fall apart. Because we would like to retainour traditional <strong>for</strong>m of social security, we have been confronted <strong>for</strong>years now with rising contributions and decreasing benefits. Thissimultaneous destruction of the freedom of the state to develop andthe margin <strong>for</strong> decision making of the individual is ultimately thegreatest danger <strong>for</strong> Germany’s social state model. The climax wasfound precisely under a political leadership that gladly gives theoutward appearance that it would like the exact opposite. TheCDU/CSU and the FDP with Helmut Kohl, Count Lambsdorff andtheir party supporters shunned re<strong>for</strong>ming financial policy and thesocial systems just as they preached freedom instead of socialism.Financing German Unity on credit and at the expense of labourersand white-collar workers in the social security system will cling

28WHERE NOW FOR EUROPEAN SOCIAL DEMOCRACY?to our feet like lead weights <strong>for</strong> decades to come.The result is public discrediting of the social state, particularly byemployees. As paradoxical as it may sound, what once helped toovercome the risks in life – that is the whole German social securitysystem – has in its traditional mode of organisation now become anobstacle to a free and self-determined life <strong>for</strong> many people. Aftersocial deductions from hard-earned gross salaries not much moneypasses into net pay packets. Particularly young families see thisincreasingly as a barrier <strong>for</strong> the freedom of choice on the one hand and<strong>for</strong> taking part in the existing social opportunities on the other.There<strong>for</strong>e, in the meantime, the willingness to partake in collectiveprotection from the risks in life is massively diminishing.If the SPD wants to preserve joint finance of the social securitysystems, due to changed occupational biographies and dramaticdemographic change it must decide on a new model of the social state.Much of what was in <strong>for</strong>mer times necessary <strong>for</strong> collective protectionhas today become obsolete at least <strong>for</strong> a large number of people,because increased income enables autonomy and provision.In principle it is a matter of reviving our concept of solidarity:acting responsibly to oneself and also towards others. How muchautonomy and personal provision may be expected in our society, howdo we create more individual decision-making authority, which risks inlife require collective protection, which public welfare interests mustbe financed through the taxes of all citizens instead of through thesocial insurance contributions of labourers and white-collar workers?The answer to these questions in no way comprises a threat oreven a departure from the social state. On the contrary, the only waywe can create a new and attractive model of the social state is withnew confidence and trust in the personal competence of everyindividual and in the efficiency of common social security systems.Take a chance on more policyLast but not least, in Germany we need to re<strong>for</strong>m our constitution initself. In reality, it is not the supposedly influential associations andlobbyists that make re<strong>for</strong>ms, creativity and innovation difficult. It is

SIGMAR GABRIEL 29the constitutional practice of state institutions themselves, becausenowhere else in the world does the respective opposition have as muchinfluence over the governing majority’s legislative practice as it doesin Germany – in fact without having a real interest in improvements.At the same time, all parliaments and governments of the post-war erahave greatly contributed to the fact that the expansion of legislation,and of the concomitant growth in administration has led to abureaucratic explosion today.Instead of safeguarding freedom and justice, people frequentlyexperience state institutions as an obstacle that restricts creativity,dynamism and the will to organise. And this is not actually just inthe case of the often-cited founders of new businesses, but alsoof associations, cultural initiatives or individual involvement. Ourpolitical system has achieved a truly organised irresponsibility if welook at the parallel jurisdiction of the municipal, state, federal and EUlevels. Not only does this in the meantime institutionally hinder theefficiency of democratically elected parliaments and governments, butalso it obstructs the tempo of essential investments and innovationsin science and the economy. It is precisely the <strong>Social</strong> Democratswho, referring to Willy Brandt, could dare and call <strong>for</strong> much moredemocracy. In order to do this, though, they must above all dare totake a chance on more policy.A re<strong>for</strong>m of our state institutions and of federalism is overdue. Asocial democracy that is less obsessed with the details of perfectinglegislation from above, and which instead opens a path <strong>for</strong> morefreedom and responsibility <strong>for</strong> the individual as well as <strong>for</strong> respectivegovernmental levels in the federation, states and municipalities wouldbe considerably more appealing.The social democratic story remains grippingThus there is not a lack of obstacles <strong>for</strong> societal and also individualprogress. The SPD has every reason to link up with its emancipatingtradition self-confidently. It must wager on freedom and socialresponsibility and cannot in the process <strong>for</strong>m contrasts. Both the wishof every individual <strong>for</strong> freedom of decision and the awareness of

30WHERE NOW FOR EUROPEAN SOCIAL DEMOCRACY?collective responsibility <strong>for</strong> the development of society as a wholecontinue <strong>for</strong> us today to be reciprocal conditions.The SPD was always the party of the modern, a party of dynamismand movement. It was the SPD that knew that achievement breaksprivileges, that what is earned and worked <strong>for</strong> is more important thanwhat is inherited. It was social democracy that cleared away barriersand blockades, broke with many taboos and as a result enabled allpeople new access to the state, economy and society. It was the SPDthat always opened up a new opportunity <strong>for</strong> the ‘excluded’.This social democratic idea is just as lively and attractive as in thelast 140 years. It comprises the story of a young society that once moreperceives children as an exciting enrichment to our lives, thatencourages competence and orientation in education and bringing upchildren, that provides social security but also requires autonomy, andit is a society that is at least as active internationally in the struggleagainst starvation and poverty as it is against despots and terrorists.We are obliged to explain to people what social democratic meanstoday and why the policies that we have today have something to dowith why we set off on this path 140 years ago. Only when we havesucceeded in this convincingly will the SPD also regain people’s trustand respect.

Permanent re<strong>for</strong>mism:the social democratic challengeof the future?PATRICK DIAMONDIt is commonplace today to advocate a strategy of ‘permanentre<strong>for</strong>mism’ 1 <strong>for</strong> the <strong>European</strong> Left. <strong>Social</strong> democrats should distinguishthe enduring goals of public policy from the contingent means throughwhich they are pursued. The revisionist tradition does not represent afixed body of ideas or programme, but rather a constant questioningof the means by which traditional social democratic aims can beachieved.Conservative parties, it is argued, stand <strong>for</strong> maintaining order – thestatus quo – while social democrats seek to advance human progress,and by embracing ‘permanent re<strong>for</strong>mism’, envisage the creation of asociety more equal, more free, more inclusive, more communitarian,and less disfigured by human misery and suffering.Permanent re<strong>for</strong>mism af<strong>for</strong>ds huge opportunities <strong>for</strong> the Left andcould be the foundation <strong>for</strong> its long-term recovery – returning indeedto the situation at the end of the 1990s when Left parties held officein 11 out of 15 <strong>European</strong> Union countries.But we must begin by debating the structural obstacles to re<strong>for</strong>m,what Anthony Crosland termed “the psychological resistance torevisionism”, and its consequences <strong>for</strong> the electoral <strong>for</strong>tunes of socialdemocratic parties – <strong>for</strong> revitalising the Left in Europe intellectuallyand politically over the coming years 2 .Throughout the 1990s many centre-left parties turned to re<strong>for</strong>mistideas in the belief that they should not merely accept the marketeconomy, but embrace the values of enterprise, personal responsibilityand hard work. No single <strong>European</strong> social democratic model emerged.Instead, three distinct and coherent modernising projects havedeveloped since the early 1990s: the modernising statism of France,31

32WHERE NOW FOR EUROPEAN SOCIAL DEMOCRACY?the consensual corporatism of Germany, and the globalized socialdemocracy of Britain.These transitions are founded on a paradigm shift within <strong>European</strong>social democracy since the mid-1980s.• The Left should remain steadfast in its commitment to socialdemocratic values, but maximise innovation in the means ofdelivery.• Liberty and freedom are the means, as much as the ends, of socialdemocratic politics and Left parties should reclaim their roots insocial liberalism.• The production of wealth is as fundamental as its redistribution: acoherent strategy <strong>for</strong> increasing productive capacity and long-termsustainable economic growth is fundamental.• Parties of the Left must embrace new currents in civic societyand seek to draw strength from the <strong>for</strong>ces of change – namelyfeminism, environmentalism, and internationalism.The history of socialism revisionismA revisionist approach is, of course, nothing new on the Left – and weshould guard against scorched earth thinking. The current revision ofsocialist doctrine is in fact strikingly similar to the revisionism of thepast. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, socialists in Britain, France,Germany, Italy and elsewhere re-examined their doctrine andattempted to free themselves of ideological baggage they regarded ascounter-productive – with varying degrees of success. The German SPDwas the path-breaker at Bad Godesberg in 1959 presenting itself as agradualist social democratic party with the slogan: “planning wherenecessary, the market whenever possible”.As Thomas Meyer has argued, Bad Godesberg achieved a dramaticbreak with the past by ending the deeply ingrained dualism on theLeft between orthodoxy at the ideological level and half-heartedpragmatism in practice 3 . Gaitskell and Crosland pursued precisely thiscourse <strong>for</strong> the British Labour Party culminating in the failed revision of‘Clause IV’ in 1959.There are other striking similarities between the revisionism of the

PATRICK DIAMOND 331950s and 1960s and what Donald Sassoon terms the ‘neo-revisionism’of today 4 . The two movements have occurred after a lengthy period ofright-wing hegemony. In both eras sociologists were predicting ‘the endof ideology’ as Kirchheimer heralded the embourgeoisement of theworking-class. There is another parallel. In both eras, a period ofpessimism about capitalism’s survival was followed by its remarkablerecovery. Since the beginning of the 1990s capitalism has provedglobally resilient despite the comparatively weak per<strong>for</strong>mance of the<strong>European</strong> economy during those years.There are of course major contrasts with the 1950s and 1960s, notleast the Left’s recent embrace of constitutional re<strong>for</strong>m – as opposedto a defence of the ‘bourgeois state’ which had first legitimised socialdemocracy in the late nineteenth century. The internal process ofrevisionism is nonetheless ceaseless.The SPD recently published a new ‘framework <strong>for</strong> the just renewalof Germany’ as part of its Agenda 2010 re<strong>for</strong>ms, embracing ‘a cultureof innovation’ in public policy 5 . By calling <strong>for</strong> the establishment ofnational ‘elite universities’ <strong>for</strong> example, Chancellor Schröder hasbroken a post-war taboo of German social democracy, as he seeks toaddress the skills gap while tapping more effectively into scientificinnovation.The leading French politician Dominique Strauss-Kahn has setout the case <strong>for</strong> a ‘radical re<strong>for</strong>mism’ in the Parti <strong>Social</strong>iste as thefoundation stone <strong>for</strong> the modernisation of French society. He has called<strong>for</strong> greater investment in education and human capital, housing andthe health sector, drawing on experience from Britain and Scandinavia,alongside fiscal and regulatory re<strong>for</strong>ms – widening access to decent andsecure jobs 6 .The British Prime Minister Tony Blair has argued recently in apamphlet published by the Fabian Society 7 : “It is time to acknowledgethe 1945 settlement was a product of its time and we must not be aprisoner of it. We must recognise that what was absolutely right <strong>for</strong> atime of real austerity no longer meets the needs and challenges in anage of growing prosperity and consumer demand”.

34WHERE NOW FOR EUROPEAN SOCIAL DEMOCRACY?Are we there<strong>for</strong>e all revisionists now?Political <strong>for</strong>ces can’t survive without regular self-questioning. Thesocialist philosopher R.H. Tawney set out the challenge <strong>for</strong> socialdemocratic parties with characteristic brilliance in the early 1950s: “totreat sanctified <strong>for</strong>mulae with judicious irreverence and to start bydeciding precisely what is the end in view”. 8 Our parties still have tonegotiate very different national political cultures and legacies – inaddition to different electoral and parliamentary situations.Nevertheless, social democrats in Europe face common challenges as aresult of globalization and the rise of ‘anti-politics’, antagonised bychanging class structure. This squeezes Left parties and <strong>for</strong>ces us toadapt to change.But this commitment still begs fundamental questions. Is theattachment to permanent re<strong>for</strong>mism really tenable in the long-term?Crosland understood that the revisionist project “is an explicitadmission that many of the old dreams are dead or realised; andthis brutal admission is resented … it destroys the old simplicity,certainty, and unquestioning conviction” 9 . Can social democraticparties there<strong>for</strong>e adopt such a vision without retreating to thecom<strong>for</strong>ting myths of the past, and can revisionists renew themselves?We should be conscious of the dilemmas posed by permanentrevisionism.Revisionist dilemmas: public service re<strong>for</strong>mThe British example is instructive. In re-casting Clause IV of the PartyConstitution in 1995 to fully embrace the market economy, New Labourended the historical antagonism between the Left and the privatesector in Britain, and abandoned <strong>for</strong>ever the dream of wholesalenationalisation of ‘the commanding heights’. It was a triumphal actof revisionism.However, such a shift has had profound long-term consequences.The consolidation of the centralised post-1945 welfare state hasemerged even more avowedly as the principal objective of the LabourParty since the mid-1990s. To swallow the market, some on the Left

PATRICK DIAMOND 35have hardened their attitude to the public sector, judging onlycentralised state provision to be compatible with the commitmentto equity.The provision of public services by traditional state providers isregarded by many in the party as the touchstone of social justice.Hence the raging disputes since 1997 over Public Private Partnershipprojects <strong>for</strong> capital infrastructure, the use of private agencies in theNHS and schools, establishing ‘foundation hospitals’ in the healthservice, and the outsourcing of public administration functions toprivate operators.This orthodoxy on public services has also been rein<strong>for</strong>ced byLabour’s abandonment of the rhetoric and aspiration of socialisttrans<strong>for</strong>mation that reached its climax with Nye Bevan in the 1950s. Bydiscarding the bold aim of replacing capitalism with socialism, aminority in the Party have settled <strong>for</strong> a more modest and conservativedefence of the traditional Welfare State as the pinnacle of socialistambition.Public services are rightly fundamental to the social democraticconception of the good society. But the removal of one rigid orthodoxyabout markets is in danger of hardening new orthodoxies in relation tothe public sector. As Andrew Gamble has persuasively argued 10 , thequestion of whether there should be public services at all has beenconfused with how the provision itself is delivered.Public services and the public sector have been equatedunambiguously when they are in fact quite different entities. That thepublic sector should be regarded as an island of altruism in a sea ofprivate interest and greed, and private profit must never be allowedto intrude, is obviously too simplistic.This intransigence puts at risk the continuous innovation essentialto achieving Labour’s aspirations <strong>for</strong> public services. The foundingprinciples of the public service to which Labour is most attached, theNHS, are that it should be universal and free at the point of delivery,not that it should be provided through a particular structure or set ofemployees.PPPs are intended not to weaken public provision, but to add a newdimension drawing on capabilities across both the state and private

36WHERE NOW FOR EUROPEAN SOCIAL DEMOCRACY?sector – tapping into the disciplines, incentives and expertise thatprivate firms can provide.But there is another rationale <strong>for</strong> PPPs beyond the shallowerappeal of ‘what matters is what works’. Partnership and collaborationprovide deeper benefits. As Martin Summers has pointed out in relationto local government: “one of the most valuable benefits of opening upwhat have traditionally been local government domains to outsideorganisations – whether they be commercial organisations, quangos,charities, NHS trusts or housing associations – is that there has beenopportunity to see how different means of decision-making per<strong>for</strong>m;thus presenting alternatives to the traditional monolithic, hierarchicaland departmentalised local authority model” 11 .Well-planned and executed partnerships can also give users andcitizen groups a stronger role in commissioning services, and achieve astronger focus on outcomes. This could ultimately mean communitiesfeel a stronger sense of ownership of public services, helping to <strong>for</strong>genew coalitions of support <strong>for</strong> adequate levels of public expenditure.Many of the most ambitious and innovative programmes undertaken bythe UK Government since 1997, including Sure Start <strong>for</strong> the early yearsand Learn Direct <strong>for</strong> adult learning, were founded with a strong ethosof partnership at the core.Formal involvement with public organisations can also trans<strong>for</strong>mthe operating behaviour of private sector firms. Such firms are calledupon to act within a regulated framework of employment law,disclosure of in<strong>for</strong>mation, integrity, and accountability. This implies,correctly, that there are no rigid ideological or institutional boundariesbetween the state, private and third sector. Both state and market areembedded in, and dependent on, social institutions. Equally, ‘privatesector involvement’ is not a catch all solution to every social policychallenge, nor is it necessarily an appropriate device <strong>for</strong> interventionwhen existing provision fails.The Labour Government in Britain has taken great strides inre<strong>for</strong>ming public services since 1997. It is striking that influentialconstituencies and interests on the Left are coming to accept the need<strong>for</strong> greater devolution and pluralism in public provision. But thedangers of new structural barriers to re<strong>for</strong>m, both institutional and

PATRICK DIAMOND 37ideological, are ever-present, as a period of revisionism andenlightenment in the 1990s risks giving way to the familiar chorus ofheresy and betrayal today.Refreshing the Third WayA second dilemma relates to the specifically Anglo-American socialdemocratic re<strong>for</strong>m project of the third way. Again, there is a dangerthat in regarding this project as the only catalyst of policy‘modernisation’, those who advance the third way <strong>for</strong>get that it tooneeds to be revised. They become by implication ‘old’ New Labour.The third way as envisaged by President Clinton in the mid-1990s wasrooted in a politics of aspiration – how to appeal to those groups in thelower middle and working-class, famously termed ‘the ReaganDemocrats’, who became alienated from the Left in the early 1970s.However, the dominant <strong>for</strong>ce in the economy and society today is oneof pervasive insecurity.The economism and futurism implicit in the third way in fact servesto undermine the revisionist approach since it implies that history hasan ultimate, fixed destination. Yet there are always new frontiers tobe conquered. The historian Larry Siedentop shows in ‘<strong>Democracy</strong> inEurope’ that the tendency to reduce politics to a solely economicmatter, a strong disposition in much of Britain and the US, carries gravedangers 12 . Equally, we should be alive to the threat of futurism – thenotion fundamental to Thatcherism that we know what the future isgoing to be; we have no choice but to embrace it; and those who graspthe future are entitled by virtue of their superior insight to lead therest of us towards it.Fatalism is the enemy of the revisionist approach. Fundamentally,if global capitalism and its <strong>for</strong>ces conquer all be<strong>for</strong>e them, how canpolitics have an ethical dimension any longer? This mentalityexacerbates cynicism and corrodes trust in public institutions bydisqualifying any scope <strong>for</strong> moral argument. The underlyingassumptions of the third way project there<strong>for</strong>e need to be re-visited.New thinking should be rooted in a broader and more coherent politicalnarrative that is unambiguously couched in the values of the Left.

38WHERE NOW FOR EUROPEAN SOCIAL DEMOCRACY?Equally, those who consider <strong>European</strong> social democracy to bein irreversible decline are too pessimistic. Embracing ‘permanentre<strong>for</strong>mism’ opens new doors and unleashes new opportunities:electoral, political and intellectual. Fundamentally, revisionism is aradical cast of mind that provides a critical framework <strong>for</strong> thinkingexpansively about human affairs, to develop strategies and policiesthat take account of change. But the Left, while embracing therevisionist project, must also be aware of its dilemmas in order togain renewed intellectual and electoral relevance.The ideal of a <strong>European</strong> Union able to offer an effective counterweightto the ‘Washington consensus’ of the IMF and World Bank hasrich potential. Economic globalization is still far from comprehensive.For all the emphasis on globalization, and the challenging structuraladjustments in the <strong>European</strong> economy it requires, trade has grownfaster within the EU than outside. Markets <strong>for</strong> goods and services, inparticular, remain far more <strong>European</strong> than global. There is still scope<strong>for</strong> macro-economic policies at both national and <strong>European</strong> level.Hence there is a golden opportunity to deepen integration in a socialand economic direction at the same time as expanding the Uniontowards eastern and central Europe.A new <strong>European</strong> social democratic model:life chance guarantees?We should there<strong>for</strong>e pursue existing initiatives such as the 2010 LisbonAgenda, while opening up new routes to economic dynamism andsocial justice. Europe needs a social architecture that is in strongerharmony with the kind of economy, employment and family structurethat is developing based around what Esping-Andersen terms ‘lifechance guarantees’ 13 . A new <strong>European</strong> social democratic model thatprovides a compelling response to insecurity yet does not imperileconomic competitiveness is still eminently achievable. But improvingproductivity and growth per<strong>for</strong>mance within the Euro zone is anessential prerequisite. It is a harsh reality, but there are no longer anynational roads to socialism.This is an open field <strong>for</strong> the Left as the Right risks imploding in the

PATRICK DIAMOND 39face of its own contradictions. Across Europe, a disparate array ofconservative parties express continuing hostility to the EU withouthaving the courage to discard its institutions. Their ef<strong>for</strong>t to createcoherence, by seeking to exploit anxiety about ‘outsiders’ whilesimultaneously affirming neo-liberalism, has provided short-termsuccess by the ruthless exploitation of insecurity – bracketing togetheranxieties about crime, migration, identity, public services, andterrorism. Yet this is deeply confused and in the long-term mayfracture the electoral constituencies of Right-wing parties beyondrepair.Conclusion: next stepsAll modern <strong>European</strong> socialist parties recognise that there is no goingback. Embracing permanent re<strong>for</strong>mism has many attractions. But weshould not delude ourselves that committing to it at the theoreticallevel will somehow dissolve all structural barriers to the revisionistproject. It will not. The hard grind of analysis, clarification,prescription and persuasion lies ahead of us. Yet if social democracy isto survive, we must do more than catch up with the changes of the last20 years. We must chart a new path <strong>for</strong> the future.

GrowthandProsperity

Is the Lisbon Process Lost?ANGELICA SCHWALL-DÜRENThree years into the EU’s Lisbon economic re<strong>for</strong>m agenda, the<strong>European</strong> Union still remains far from achieving its goal of becomingthe “most dynamic and competitive knowledge-based economy in theworld by 2010”. Despite this, notable progress has been made at the<strong>European</strong> level in implementing many parts of the Lisbon agenda – suchas energy liberalisation, financial services integration and the adoptionof a Community Patent, though we are still waiting <strong>for</strong> the positiveeffects on growth and employment that were <strong>for</strong>ecast. Today it isquestionable whether we can meet the ambitious targets <strong>for</strong> reducingunemployment, raising employment rates <strong>for</strong> women and olderworkers and increasing expenditure on research and development tothe three per cent of GDP set at Lisbon.In view of the budget deficits in Germany, Portugal, France, Italyand The Netherlands, continuing slow growth rates and labour marketproblems – one might say that the Stability and Growth Pact ensuresneither stability nor growth and so call <strong>for</strong> changes to be made. ButI will not do so. Why?First, some remarks on the Stability and Growth Pact.At the <strong>European</strong> level, the rationale <strong>for</strong> the Stability and GrowthPact and the observance of sound fiscal rules in all the Eurozonecountries is as valid today as it was in 1997, when the Pact wascreated. If countries share a common currency, they need a set of keyrules <strong>for</strong> their fiscal policies and some kind of fiscal coordination.Without this, it could push up inflation and result in the ECB’s interestrates going higher than they otherwise would. Breaking the rules wouldalso send the wrong signal to the accession countries – showing that thecurrent Member States are unable to implement the necessary re<strong>for</strong>ms43

44WHERE NOW FOR EUROPEAN SOCIAL DEMOCRACY?and secure sound finances.In my view, the overall framework <strong>for</strong> stability-oriented economicand monetary policy in Europe is broadly appropriate, and there isno need <strong>for</strong> dramatic changes. Nevertheless, I do see scope <strong>for</strong>improvement. I believe the EU needs fiscal rules that are flexibleenough to allow governments and parliaments to react to economicdifficulties, but strict enough to ensure the sustainability of publicfinances. The Stability and Growth Pact – in my opinion – gives us thisflexibility. I will return to this point later on.What is wrong in Germany?In my opinion, the budgetary problems in Germany, France, Italy andalso in The Netherlands are not caused by the Stability and GrowthPact or the euro. There is no doubt that the German economy – whichis highly dependant on exports – has been very badly affected by theuncertainty and poor growth seen in the global economy since 2001.The unfavourable economic conditions during the last three years havehad, and are still having, a particularly adverse effect on tax revenues,making additional expenditure on the labour market and social securitynecessary. But there are also other, special factors – such as thenecessary continuation of (very high) transfer payments to the newLänder, or constituent states, of the <strong>for</strong>mer East Germany; Germany’ssubstantial net contribution to the EU budget and last but not least:the fact that over many years (under the Kohl government) there wasa failure to implement real re<strong>for</strong>ms in Germany.The conjunction of all these factors has brought about the currentsituation, which restricts Germany’s fiscal room <strong>for</strong> manoeuvre.In consequence, the ‘German political class’ and the Parliament inparticular has been engaged in very tough debates, which are stillcontinuing, about how to overcome the economic slowdown and risingunemployment, how to stimulate growth and ensure fiscal stability,and how to implement the unavoidable structural re<strong>for</strong>ms withoutlosing the next elections.I think the main task is to find the right policy mix: one that willensure the long-term sustainability of public finances, growth, more