Honey Eaters Factsheet - the Living Smart Program

Honey Eaters Factsheet - the Living Smart Program

Honey Eaters Factsheet - the Living Smart Program

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

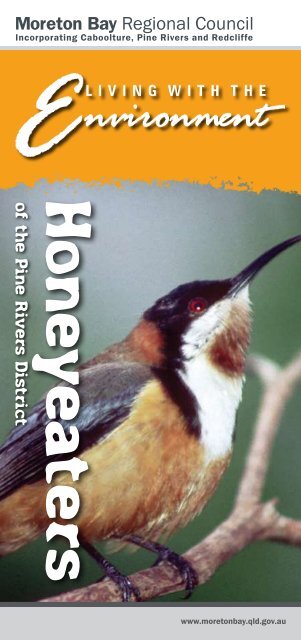

<strong>Honey</strong>eaters belong to one of Australia’s mosttypical and largest bird families, Family Melaphagidae. Theyare restricted to <strong>the</strong> region from Bali, New Guinea, Australiaand New Zealand to <strong>the</strong> central Pacific.Of <strong>the</strong> 165 or sospecies, 67 occurin Australia.<strong>Honey</strong>eaters range in size from tiny to fairly large. Theyvary in colour from plain olive-greens, greys and brownsto rich reds, yellows, blues, black and white. They aretypically vocal, active and often aggressive birds. The billis usually long, slender and curved downwards, notchedand often with teeth, but never bristled. As an adaptationto feeding on nectar, <strong>the</strong> tongue can be protruded andhas longitudinal channels or grooves, and <strong>the</strong> end is splitinto four tips, each with a brush for mopping up <strong>the</strong> nectar.To assist honeyeaters in clambering and climbing on smallbranches and twigs to reach flowers, <strong>the</strong>ir feet are strongwith sharp claws.Nectar is mostly water and sugars, with only minuteamounts of o<strong>the</strong>r food substances. Sugar provides <strong>the</strong>energy that honeyeaters need for <strong>the</strong>ir nonstop activity,but does not supply <strong>the</strong> proteins, vitamins and lipids (fats& oils) essential for growth, repair and functioning of <strong>the</strong>irtissues. Eating insects and small quantities of pollenprovides <strong>the</strong>se nutrients. Some honeyeaters eat a lot offruit; o<strong>the</strong>rs are particularly insectivorous; but all eatnectar. <strong>Honey</strong>eaters drink often and love to ba<strong>the</strong>.

Hordes of insects seek out nectar and pollen – butterflies,moths, bees, wasps, ants, beetles and bugs; and <strong>the</strong>seattract multitudes of insectivorous animals – birds in<strong>the</strong> daytime, bats and marsupials at night. Australianplants <strong>the</strong>refore are <strong>the</strong> centres of innumerablefood webs that provide for our local wildlife.Planting and retention of <strong>the</strong>se ensure biodiversity, even insuburbia.The unnecessary and unfortunate removal of nativeplants, and <strong>the</strong>ir replacement by exotic plants for gardens,streets, roads and parkland, guarantees that fewer nativeanimals will inhabit our towns and cities of <strong>the</strong> future. Poorenvironmental decisions of <strong>the</strong> past and those of todayas to what to plant will impact upon our suburban nativewildlife for generations – possibly permanently.Plants with abundant nectar for honeyeaters includeeucalypts, corymbias, angophoras, callistemons,melaleucas, grevillias, banksias, hakeas and mistletoes.O<strong>the</strong>rs include Black Bean, Batswing Coral, native heaths,apple berries, kangaroo paws and Christmas Bells.Several species of honeyeater may live and feed in onearea, sometimes sharing flowers of <strong>the</strong> same plants, butusually feeding on flowers of certain species, andfrom particular levels within <strong>the</strong> habitat. Some seekfood near ground level and in low shrubs, some within <strong>the</strong>mid-storey and o<strong>the</strong>rs high in <strong>the</strong> canopy. Feeding occurswith boisterous chasing, squabbling and calling betweenmembers of <strong>the</strong> same or o<strong>the</strong>r species.

Nests of honeyeaters are shallow to deep cups hung fromor seated upon branches or twigs, from close to <strong>the</strong> groundto high in <strong>the</strong> canopy. They are made from a variety offibrous and o<strong>the</strong>r materials woven toge<strong>the</strong>r – strips of bark,rootlets, grass, cobwebs, lichens, etc. Breeding is oftenopportunistic, occurring when conditions are favourable forsurvival, such as after good rain and when nectar yields andinsects are prolific. Breeding may occur from spring to lateautumn, usually between August and December.Some honeyeaters migrate north-south, moving northin <strong>the</strong> winter. O<strong>the</strong>rs migrate to coastal regions from <strong>the</strong>Great Dividing Range in winter and stay until <strong>the</strong> warm earlysummer. O<strong>the</strong>r species are essentially nomadic, following<strong>the</strong> flowering flushes of food plants. Some species andsome individual birds may stay throughout <strong>the</strong> year wherefood, water, shelter and breeding needs are provided (forexample, in well-planted native gardens).Why we need honeyeatersin our bush and gardens:• They bring a natural joy to our surroundings with <strong>the</strong>iruntiring activity, beauty and cheerful songs,• <strong>Honey</strong>eaters assist pollination – many nativeflowers are adapted so that honeyeaters transfer pollento o<strong>the</strong>r plants of <strong>the</strong> species. Some groups of plants,such as many grevilleas and hakeas, rely especially onhoneyeaters for pollination.• <strong>Honey</strong>eaters are major controllers of insectnumbers including insects that aggravatedieback in our native plants. All honeyeaters eatinsects, particularly before and during breeding. Somefeed mainly on insects and supplement this diet withnectar. Many catch insects on <strong>the</strong> wing; o<strong>the</strong>rs seekinsects, <strong>the</strong>ir larvae and pupae among flowers, leaves,twigs and branches.

How to attract honeyeatersto our gardens:The three essential requirements for honeyeatersif <strong>the</strong>y are to become permanent residents orregular visitors to our gardens are:Food – This can be totally supplied by retaining local bushland andgrowing a good variety of native plants in <strong>the</strong> garden, as street trees andin parkland. A variety of species is far better than a mono-culture. Becausewe are planting a majority of exotics that offer less insect food suitablefor honeyeaters and o<strong>the</strong>r small insect feeders, wildlife in suburbs isdecreasing.Water – A birdbath, a garden pool or dam for <strong>the</strong>ir drinking andbathing will encourage honeyeaters to stay and breed.Safety – Smaller honeyeaters (and o<strong>the</strong>r small birds) require refugefrom aggressive larger birds. Parkland, sports fields, streets, roadverges and gardens with lawns are attractive to <strong>the</strong> typically aggressivebirds of open spaces and forest edges – crows, currawongs, magpies,butcherbirds, noisy miners (<strong>the</strong>mselves native honeyeaters) and maskedlapwings. We have increased <strong>the</strong> size and number of open spaces whenwe need to have smaller areas of lawn and more native plants in all levels– understorey, midstorey and canopy. Some prickly or thorny nativeplants in our gardens will provide refuge for smaller birds. Cats and dogsand imported Common (Indian) Mynahs are o<strong>the</strong>r reasons we have fewersmall birds such as honeyeaters in urban areas.

Supply of artificial foods isnot recommended as a way toattract honeyeaters to gardens.The provision of artificial foodfor honeyeaters may cause <strong>the</strong>following problems:Malnutrition. <strong>Honey</strong> and sugar mixtures do not supplymany essential food substances and, if supplied regularlyand in anything but small amounts, can adversely affect <strong>the</strong>health of birds.Poisoning. Food mixtures left out too long, especially inhot wea<strong>the</strong>r, can become rancid and toxic.Overpopulation and dependency. Populationsof some species may become so high that, without constanthandouts, local natural food is insufficient, and many birdsdie if artificial feeding ceases.Pest species. Sparrows, Common (Indian) Mynahs,Spotted Turtledoves, rats and mice are some of <strong>the</strong>unwanted animals attracted to foods put out for nativeanimals.Decreased biodiversity. Constant supplies ofartificial food attract dominating species that drive <strong>the</strong>smaller timid birds away - defeating <strong>the</strong> purpose forartificial feeding.Specially-formulated nectar foods from reputable produce shops,supplied in small quantities, will probably not upset naturalbalances or affect <strong>the</strong> health of <strong>the</strong> honeyeaters. However, <strong>the</strong>seartificial foods are not a substitute for gardens (or better, wholesuburbs) with a variety of many native plants that will supply foodcontinuously throughout <strong>the</strong> year.

Some local honeyeaters in detailNoisy Friarbird (Philemon corniculatus)The Noisy Friarbird (also called Lea<strong>the</strong>r-head) is one of our largestand noisiest honeyeaters. They are particularly fond of <strong>the</strong> nectarof eucalypts, banksias and grevilleas and eat a range of insectson plants, and flying insects. Fruit is also eaten. They camp highin <strong>the</strong> canopy. In <strong>the</strong> morning after <strong>the</strong> repeated dawn (anddusk) call of ‘jacob’, <strong>the</strong>y commence feeding with a cacophonyof rollicking ‘happy’ cackles as <strong>the</strong>y hop about and hang in <strong>the</strong>foliage or chase each o<strong>the</strong>r, o<strong>the</strong>r birds, and flying insects.In autumn <strong>the</strong>y move from <strong>the</strong> mountains to <strong>the</strong> lowlands and flyhigh in groups as <strong>the</strong>y move northward. They return in spring at amore leisurely pace, feeding in smaller groups as <strong>the</strong>y go.Blue-faced <strong>Honey</strong>eater (Entomyzon cyanotis)This is ano<strong>the</strong>r of <strong>the</strong> larger honeyeaters. They are social birds thatfeed, roost, ba<strong>the</strong> and protect <strong>the</strong>ir territory as a group. They arefond of insects, catching <strong>the</strong>m on <strong>the</strong> wing or collecting <strong>the</strong>m in<strong>the</strong> foliage. They are particularly fond of <strong>the</strong> caterpillars that feedon palm fronds. They also eat fruit and may do some damage inorchards.Blue-faced <strong>Honey</strong>eatersbreed communally, usuallyclose to streams and where<strong>the</strong>re is a supply of food,such as stands of floweringpaperbarks and eucalypts.They often use old nestsof o<strong>the</strong>r birds, especiallythose of <strong>the</strong> Grey-crownedBlue-faced <strong>Honey</strong>eaterBabbler. The young have agreen cheek patch ra<strong>the</strong>rthan blue.

Noisy Miner (Manorina melanocephala)Noisy Miners are often accused of ‘chasing little birds away’ frompeople’s gardens. This is unfair – small birds are attracted to andwill remain in gardens and parks that are more environmentallyfriendly.If lawn areas are smaller and all levels of vegetationoccur (groundcovers, understorey, mid-storey and canopy), and<strong>the</strong>re is a variety of native plants, a wider range of birds will befound. Cottage gardens of introduced plants, and mowed acreageblocks do not favour most native birds and o<strong>the</strong>r animals. NoisyMiners set up <strong>the</strong>ir communal groups in open spaces and edgesof vegetation and will defend <strong>the</strong>se against o<strong>the</strong>r birds and mosto<strong>the</strong>r animals.Because <strong>the</strong>y have a very varied diet, including nectar and o<strong>the</strong>rplant juices, insects and <strong>the</strong>ir exudates (secretions), and fruit,<strong>the</strong>y are common near playgrounds, picnic spots and barbecueareas where <strong>the</strong>y eat human foods such as bread, honey, jam andbutter.The female builds <strong>the</strong> nest and <strong>the</strong>n may attract as many as twodozen males to assist in <strong>the</strong> feeding of <strong>the</strong> young. Females andyoung beg to be fed by calling, ‘Mick, Mick, …’ ; thus <strong>the</strong> commonname, ‘Micky Bird’. Noisy Miners have a wide range of calls – amorning song before sunrise, o<strong>the</strong>r social contact calls, andspecific alarm calls for warning of particular dangers.Noisy Miner

Lewin’s <strong>Honey</strong>eater (Meliphaga lewinii)This is a bird that lives in and near rainforests. Its calls of rapidlyrepeated ‘toots’, at dawn and less frequently through <strong>the</strong> day,are typical of rainforest. Lewin’s <strong>Honey</strong>eaters eat nectar, insectsand fruit, mostly from mid and upper canopies. They tend to besedentary, spending most of <strong>the</strong>ir time singly or in pairs in <strong>the</strong>irestablished territories, which <strong>the</strong>y defend against o<strong>the</strong>rs of <strong>the</strong>irkind and o<strong>the</strong>r honeyeaters. In winter <strong>the</strong> young of <strong>the</strong> previousseason usually move out to find new territories.Lewin’s <strong>Honey</strong>eaters will become permanent members ofsuburban gardens if we grow a variety of small native rainforesttrees and shrubs. Suitable ones include myrtles (Austromyrtusspp.), plum myrtles (Pilidostigma spp.), Rhodamnia species,Native Guava, Blueberry Ash and lilly pillies. Nectar-producingplants such as callistemons, melaleucas, and grevilleas alsoattract Lewin’s <strong>Honey</strong>eaters. They may eat some garden fruits.Lewin’s <strong>Honey</strong>eater – artificial feeding of birds should be limited.Scarlet <strong>Honey</strong>eater (Myzomela sanquinolenta)About <strong>the</strong> beginning of winter, this species, <strong>the</strong> smallest of ourhoneyeaters, moves down from <strong>the</strong> hills and mountains of <strong>the</strong>D’Aguilar Range to lower areas and stays until about November.Some also move up from <strong>the</strong> south at this time. As <strong>the</strong> breedingseason approaches, males sing <strong>the</strong>ir pretty tinkling song of aboutsix to eight notes, more often and more vigorously. Females uttera high-pitched chirp. She is not as colourful, lacking <strong>the</strong> scarletand black that make <strong>the</strong> male bird one of our most exquisitehoneyeaters.

The main food of <strong>the</strong> Scarlet <strong>Honey</strong>eater is nectar, and this isprocured from flowering eucalypts (such as Grey Ironbark andQueensland Blue Gum), bottlebrush, paperbarks and banksias.Insects are also eaten, more so during <strong>the</strong> breeding season.The female builds <strong>the</strong> nest and incubates <strong>the</strong> eggs, her dullcolours making her less conspicuous. The colourful male is verynoticeable and advertises his presence to rival males by hisrepeated singing.Scarlet <strong>Honey</strong>eater – many spend winter on <strong>the</strong> coast.Eastern Spinebill (Acanthorhynchus tenuirostris)Eastern Spinebills use <strong>the</strong>ir long bills and almost tube-liketongues for taking nectar. Tubular flowers are <strong>the</strong>ir specialty –appleberries (Billardeira), native heaths (Epacris), Christmas Bells(Blandfordia); and <strong>the</strong>y are important pollinators of <strong>the</strong>se plants.Eucalypts are also visited. If we grow <strong>the</strong>se plants and nativessuch as grevilleas, banksias, hakeas, crinkle bush (Lomatia),kangaroo paws and geebungs we can encourage spinebills to<strong>the</strong> garden. When feeding, usually alone, <strong>the</strong>y flit audibly fromflower to flower, hovering in front of some flowers and hangingfrom twigs to suck <strong>the</strong> nectar. They spend most of <strong>the</strong>ir time in<strong>the</strong> lower understorey. Though <strong>the</strong> adult diet is nectar and a fewinsects, <strong>the</strong>y feed <strong>the</strong>ir young almost entirely on insects. The maleassists in <strong>the</strong> feeding of <strong>the</strong> young, and may also help a little innest construction and incubation.

In Pine Rivers we mostly observe Eastern Spinebills towards <strong>the</strong>western, more hilly and mountainous areas. They are commonat Mt Glorious and Mt Nebo. Some individual birds come to <strong>the</strong>lower and coastal areas in <strong>the</strong> cooler months, and return when itbecomes warmer.Sweet Apple BerryEastern Spinebill – adapted to tubular flowers.Some less-common<strong>Honey</strong>eaters of Pine RiversNew Holland <strong>Honey</strong>eaterYellow-tufted <strong>Honey</strong>eaterBrush (Little) Wattlebird

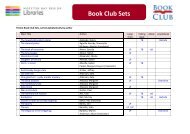

<strong>Honey</strong>eatersof Pine RiversCommon Name Scientific Name CommentsRed WattlebirdBrush (Little)WattlebirdStriped <strong>Honey</strong>eaterAnthochaeracarunculataAnthochaerachrysopteraPlectorhynchalanceolataRed wattles (fleshy lobes) on cheeks;eats nectar & insects; ‘chok’ soundsWattlebird, but lacks wattles; nectar& insect feeder; ‘chok’ soundsWarbling song; eats mostly fruit &insects, & some nectarNoisy Friarbird Philemon corniculatus Large honeyeater; knob on bill; barehead; eats insects, nectar & fruitLittle Friarbird Philemon citreogularis Smallest of our friarbirds; no knobon bill; eats insects, nectar & fruitRegent <strong>Honey</strong>eater Zanthomyza phrygia Rare honeyeater; metallic call; eatsmostly nectar, some insects & fruitBlue-faced<strong>Honey</strong>eaterEntomyzon cyanotisLarge honeyeater. Young have greenface; eats mostly insectsBell Miner Manorina melanophrys Famed ‘bellbird’ – eats mainly scaleinsects & <strong>the</strong>ir sugary coatingNoisy MinerManorinamelanocephalaNative of open spaces & margins;eats mainly insects, & fruit & nectarLewin’s <strong>Honey</strong>eater Meliphaga lewinii Rainforests and scrubby streams;eats fruit, nectar & insectsYellow-faced<strong>Honey</strong>eaterMangrove<strong>Honey</strong>eaterYellow-tufted<strong>Honey</strong>eaterFuscous <strong>Honey</strong>eaterBlack-chinned<strong>Honey</strong>eaterWhite-throated<strong>Honey</strong>eaterWhite-naped<strong>Honey</strong>eaterLichenostomuschrysopsLichenostomusversicolorLichenostomusmelanopsLichenostomusfasciogularisMelithreptus gularisMelithreptusalbogularisMelithreptus lunatusBreeds in south & migrates north inautumn; eats mainly nectar & insectsRestricted to mangrove and nearbyareasEucalypt forests; colonies often nearcreeksColonies in open forest, woodland;near creeksDrier areas of eucalypt woodland.Black centre line under chinBluish white above eye – Cf. Whitenaped<strong>Honey</strong>eaterRed mark above eye – Cf. Whitethroated<strong>Honey</strong>eaterBrown <strong>Honey</strong>eater Lichmera indistincta A common garden bird. Plain olivegreyPainted <strong>Honey</strong>eater Grantiella picta Eats mistletoe fruit – nomadic withfruitingNew Holland<strong>Honey</strong>eaterWhite-cheeked<strong>Honey</strong>eaterEastern SpinebillScarlet <strong>Honey</strong>eaterPhylidonyrisnovaehollandiaePhylidonyris nigraAcanthorhynchustenuirostrisMyzomelasanquinolentaFeeds mostly in small trees & shrubsCoastal heaths & woodlands; esp.BanksiaAudibly flutters; long curved bill;feeds in <strong>the</strong> understoreyThe smallest of our honeyeaters

All honeyeaters eat nectar and insects. Nectar and pollen attractinsects. The amount and food value, and <strong>the</strong> attractiveness ofpollen and nectar to insects, all vary – with plant species, wea<strong>the</strong>rconditions, and year to year. In natural bushland and where nativeplants are retained or planted, a continuous ’flow’ of nectar andpollen ensures that animals which feed on nectar, pollen andinsects are present throughout <strong>the</strong> year. The following chart shows<strong>the</strong> annual food cycle for honeyeaters.Nectar & Pollen Flow of Trees and Shrubs of Pine Rivers(excluding rainforest species)n = minor nectar; N = medium nectar; N = major nectar;p = minor pollen; P = medium pollen; P = major pollen;- = nil nectar or nil pollen + = suitable for small gardensFlow Species Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec- P Hickory Wattle • • • • •N P Pink Bloodwood • • •n P Grey Mangrove •n P Soap Bush/Red Ash • • •N - Gum-topped Box • • •n P Blackbutt • • •N P Swamp Paperbark • • • • • •n P Flooded Gum • • •n p +Hill Banksia • • • • • • • • •N P +Coast Banksia • •- p Forest She Oak • •- P +Black She Oak • • • • • • •- P River She Oak • • • • • • •n P Broad-leaf Ironbark • • • • • • • • •- P +Early Black Wattle • • •n p Swamp Messmate • •n P Spotted Gum • • • •- P +Hairy Bush Pea • • • • •- P Late Black Wattle • • •- P +Brisbane Wattle • • •n P Qld Blue Gum • • • • •N p Grey Ironbark • • • • • •n p Scribbly Gum • • • •n P +Red Bottlebrush • • •n P +Dogwood • • •n P Tallowwood • • •N P Narrow-leaf Ironbark • • • • •n P +Ball <strong>Honey</strong> Myrtle • •- p Swamp She Oak • •n P White Bottlebrush • •N P Narrow-leaf Red Gum • • • •N P +Wild May • •N P River Mangrove • •n P Snow-in-Summer • •n P +Heath Myrtle • • •N P White Mahogany • • •N p Swamp Box • • •n p Moreton Bay Ash • • • •N P Red Stringybark • • • •n P +Wallum Bottlebrush • • • • • •n P Rusty Apple Gum • •N p Brush Box • •n P Broad-leaf Apple • •n P Smudgee • •n p +Swamp Banksia • • • • • •N P Silver-leaf Ironbark • • •n P Small-fruit Grey Gum • • •n p +Grass Tree species • • • • • • • • • • • •

www.moretonbay.qld.gov.au© Moreton Bay Regional Council 2008

![Kumbartcho Brochure [PDF 540KB] - Moreton Bay Regional Council](https://img.yumpu.com/47220970/1/190x101/kumbartcho-brochure-pdf-540kb-moreton-bay-regional-council.jpg?quality=85)