Are Prisons Obsolete?

Are Prisons Obsolete?

Are Prisons Obsolete?

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

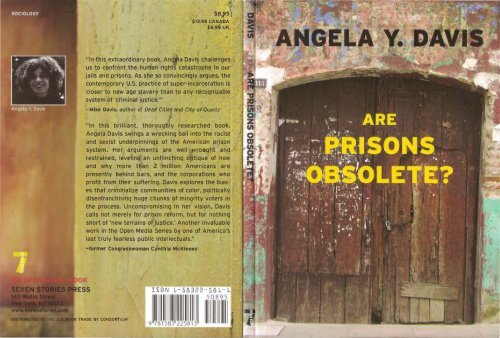

sa.jls:$13.95 CANADA£6.99 UK"In this extraordinary book. Ang la Davis challengesus to confront the human rights catastrophe In ourjails and prisons. As she so convincingly argues, thecontemporary U.S. practice of super-incarceration iscloser to new age slavery than to any recognizablesystem of 'criminal justice.'"-Mike Davis, author of Dead Cities and City of Quartz"In this brilliant, thoroughly researched book.Angela Davis swings a wrecking ball Into the racistand sexist underpinnings of the American prisonsystem. Her arguments are well wrought andrestrained, leveling an unflinching critique of howand why more than 2 million Americans arepresently behind bars, and the corporations whoprofit from their suffering. Davis explores the biasesthat criminalize communities of color, politicallydisenfranchising huge chunks of minority voters inthe process. Uncompromising in her vision, Daviscalls not merely for prison reform, but for nothingshort of 'new terrains of justice.' Another Invaluablework In the Open Media Series by one of America'slast truly fearless public intellectuals."-formor ConQresswoman Cynthia McKinneyISBN 1-58322-581-1"Tfill •• JK TRADE BY CONSORTIUM

ARE PRISONSOBSOLETE?AnCJela Y. DavisAn Open Media BookSEVEN STORIES PRESSNew York

© 2003 by Angela Y. DavisContentsOpen Media series editor, Greg Ruggiero.All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproiuced, stored ina retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, by any means, includ·ing mechanical, electric, photocopying, recording or otherwise, withoutthewritten permission of the publisher.In Canada: Publishers Group Canada, 250A Carlton Street, Toronto ,ONM5A211In the U.K.: Turnaround Publisher Services Ltd., Unit 3, OlympiaTrading Estate, Coburg Road, Wood Green, London N22 6TZIn Australia: Palgrave Macmillan, 627 Chapel Street, South Yarra,VIC 3141Cover design and photos: Greg RuggieroISBN·lO: 1·58322·581-1/ ISBN-I3: 978-1-58322-581-3Printed in Canada.9 8 7 6 5 4 3Acknowledgments . . . .. . . .. . ... .. . . .. . .. . .. .... . .7CHAPTER 1Introduction-Prison Reform or Prison Abolition? . . . . .. . 9CHAPTER 2Slavery, Civil Rights, and AbolitionistPerspectives Toward Prison . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . .. . 22CHAPTER 3Imprisonment and Reform . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . ... . .. .40CHAPTER 4How Gender Structures the Prison System . . . . . . . . . . . 60CHAPTERSThe Prison Industrial Complex .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84CHAPTER 6Abolitionist Alteruatives ... .. . . . . .. . . .. . . . . . . .. . 105Resources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .116Notes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 119About the Author . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . .. . . . . . . . . . . 1285

AcknowledgmentsI should not be listed as the sole author of this book, for itsideas reflect various forms of collaboration over the last sixyears with activists, scholars, prisoners, and cultural workerswho have tried to reveal and contest the impact of theprison industrial complex on the lives of people-within andoutside prisons-throughout the world. The organizingcommittee for the 1998 Berkeley conference, CriticalResistance: Beyond the Prison Industrial Complex, includedBo (rita d. brown), Ellen Barry, Jennifer Beach, Rose Braz,Julie Browne, Cynthia Chandler, Kamari Clarke, LeslieDiBenedetto Skopek, Gita Drury, Rayne Galbraith, RuthieGilmore, Naneen Karraker, Terry Kupers, Rachel Lederman,Joyce Miller, Dorsey Nunn, Dylan Rodriguez, EliRosenblatt, Jane Segal, Cassandra Shaylor, Andrea Smith,Nancy Stoller, Julia Sudbury, Robin Templeton, and SuranThrift. In the long process of coordinating plans for this conference,which attracted over three thousand people, weworked through a number of the questions that I raise in thisbook. I thank the members of that committee, includingthose who used the conference as a foundation to build theorganization Critical Resistance. In :2000, I was a member ofa University of California Humanities Research InstituteResident Research Group and had the opportunity to partic-7

We thus think about imprisonment as a fate reserved forothers, a fate reserved for the "evildoers," to use a termrecently popularized by George W. Bush. Because of the persistentpower of racism, 1/ criminals" and II evildoers" are, inthe collective imagination, fantasized as people of color. Theprison therefore functions ideologically as an abstract siteinto which undesirables are deposited, relieving us of theresponsibility of thinking about the real issues afflicting thosecommunities from which prisoners are drawn in such disproportionatenumbers. This is the ideological work that theprison performs-it relieves us of the responsibility of seriouslyengaging with the problems of our society, especiallythose produced by racism and, increasingly, global capitalism.What, for example, do we miss if we try to think aboutprison expansion without addressing larger economic developments?We live in an era of migrating corporations. Inorder to escape organized labor in this country-and thushigher wages, benefits, and so on-corporations roam theworld in search of nations providing cheap labor pools. Thiscorporate migration thus leaves entire communities inshambles. Huge numbers of people lose jobs and prospectsfor future jobs. Because the economic base of these communitiesis destroyed, education and other surviving socialservices are profoundly affected. This process turns the men,women, and children who live in these damaged communitiesinto perfect candidates for prison.In the meantime, corporations associated with the punishmentindustry reap profits from the system that managesprisoners and acquire a clear stake in the continued growthof prison populations. Put simply, this is the era of the prisonindustrial complex. The prison has become a black hole intowhich the detritus of contemporary capitalism is deposited.Mass imprisonment generates profits as it devours social16 1 Angela Y. Daviswealth, and thus it tends to reproduce the very conditionsthat lead people to prison. There are thus real and often quitecomplicated connections between the deindustrialization ofthe economy-a process that reached its peak during the1980s-and the rise of mass imprisonment, which also beganto spiral during the Reagan-Bush era. However, the demandfor more prisons was represented to the public in simplisticterms. More prisons were needed because there was morecrime. Yet many scholars have demonstrated that by thetime the prison construction boom began, official crime statisticswere already falling. Moreover, draconian drug lawswere being enacted, and "three-strikes" provisions were onthe agendas of many states.In order to understand the proliferation of prisons and therise of the prison industrial complex, it might be helpful tothink further about the reasons we so easily take prisons forgranted. In California, as we have seen, almost two-thirds ofexisting prisons were opened during the eighties andnineties. Why was there no great outcry? Why was theresuch an obvious level of comfort with the prospect of manynew prisons? A partial answer to this question has to dowith the way we consume media images of thc prison, evenas the realities of imprisonment are hidden from almost allwho have not had the misfortune of doing time. Culturalcritic Gina Dent has pointed out that our sense of familiaritywith the prison comes in part from representations ofprisons in film and other visual media.The history of visuality linked to the prison is alsoa main reinforcement of the institution of theprison as a naturalized part of our social landscape.The history of film has always been wedded to therepresentation of incarceration. Thomas Edison'sARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? 117

first films (dating back to the 1901 reenactment presentedas newsreel, Execution of Czolgosz withPanorama of Auburn Prison) included footage ofthe darkest recesses of the prison. Thus, the prisonis wedded to our experience of visuality, creatingalso a sense of its permanence as an institution. Wealso have a constant flow of Hollywood prisonfilms, in fact a genreJlSome of the most well known prison films are: I Want toLive, Papillon, Cool Hand Luke, and Escape from Alcatraz.It also bears mentioning that television programming hasbecome increasingly saturated with images of prisons. Somerecent documentaries include the A&E series The BigHouse, which consists of programs on San Quentin,Alcatraz, Leavenworth, and Alderson Federal Reformatoryfor Women. The long-running HBO program Oz has managedto persuade many viewers that they know exactly whatgoes on in male maximum-security prisons.But even those who do not consciously decide to watch adocumentary or dramatic program on the topic of prisonsinevitably consume prison images, whether they choose toor not, by the simple fact of watching movies or TV. It is virtuallyimpossible to avoid consuming images of prison. In1997, I was myself quite astonished to find, when I interviewedwomen in three Cuban prisons, that most of themnarrated their prior awareness of prisons-that is, beforethey were actually incarcerated-as coming from the manyHollywood films they had seen. The prison is one of themost important features of our image environment. This hascaused us to take the existence of prisons for granted. Theprison has become a key ingredient of our common sense. Itis there, all around us. We do not question whether it should18 I Angela Y. Davisexist. It has become so much a part of our lives that itrequires a great feat of the imagination to envision lifebeyond the prison.This is not to dismiss the profound changes that haveoccurred in the way public conversations about the prisonare conducted. Ten years ago, even as the drive to expand theprison system reached its zenith, there were very few critiquesof this process available to the public. In factI mostpeople had no idea about the immensity of this expansion.This was the period during which internal changes-in partthrough the application of new technologies-led the U.S.prison system in a much more repressive direction. Whereasprevious classifications had been confined to low, medium,and maximum security, a new category was invented-thatof the super-maximum security prison, or the supermax.The turn toward increased repression in a prison system,distinguished from the beginning of its history by its repressiveregimes, caused some journalistsl public intellectualsland progressive agencies to oppose the growing reliance onprisons to solve social problems that are actually exacerbatedby mass incarceration.In 1990, the Washington-based Sentencing Project publisheda study of U.S. populations in prison and jail, and onparole and probation, which concluded that one in fourblack men between the ages of twenty and twenty-nine wereamong these numbers.12 Five years later, a second studyrevealed that this percentage had soared to almost one inthree (32.2 percent). Moreover, more than one in ten Latinomen in this same age range were in jail or prison, or on probationor parole. The second study also revealed that thegroup experiencing the greatest increase was black women,whose imprisonment increased by seventy -eight percent.13According to the Bureau of Tustice Statistics, African-ARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? 119

Americans as a whole now represent the majority of stateand federal prisoners, with a total of 803,400 blackinmates-118,600 more than the total number of whiteinmates.14 During the late 1990s major articles on prisonexpansion appeared in Newsweek, Harper's, Emerge, andAtlantic Monthly. Even Colin Powell raised the question ofthe rising number of black men in prison when he spoke atthe 2000 Republican National Convention, which declaredGeorge W. Bush its presidential candidate.Over the last few years the previous absence of criticalpositions on prison expansion in the political arena hasgiven way to proposals for prison reform. While public discoursehas become more flexible, the emphasis is almostinevitably on generating the changes that will produce a betterprison system. In other words, the increased flexibilitythat has allowed for critical discussion of the problems associatedwith the expansion of prisons also restricts this discussionto the question of prison reform.As important as some reforms may be-the eliminationof sexual abuse and medical neglect in women's prison, forexample-frameworks that rely exclusively on reforms helpto produce the stultifying idea that nothing lies beyond theprison. Debates about strategies of decarceration, whichshould be the focal point of our conversations on the prisoncrisis, tend to be marginalized when reform takes the centerstage. The most immediate question today is how to preventthe further expansion of prison populations and how to bringas many imprisoned women and men as possible back intowhat prisoners call lithe free world." How can we move todecriminalize drug use and the trade in sexual services?How can we take seriously strategies of restorative ratherthan exclusively punitive justice? Effective alternativesinvolve both transformation of the techniques for addressing20 I Angela Y. Davis"crime" and of the social and economic conditions thattrack so many children from poor communities, and espeCially communities of color, into the juvenile system andthen on to prison. The most difficult and urgent challengetoday is that of creatively exploring new terrains of justice,where the prison no longer serves as our major anchor.ARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? 121

Slavery,2Civil RiQhts, andAbolitionist Perspectives TowardPrisonif Advocates of incarceration .. . hoped that the penitentiarywould rehabilitate its inmates. Whereas philosophersperceived a ceaseless state of war between chattelslaves and their masters, criminologists hoped to negotiatea peace treaty of sorts within the prison walls. Yetherein lurked a paradox: if the penitentiary's internalregime resembled that of the plantation so closely that thetwo were often loosely equated, how could the prison possiblyfunction to rehabilitate criminals?"-Adam Jay Hirsch15The prison is not the only institution that has posed complexchallenges to the people who have lived with it and havebecome so inured to its presence that they could not conceiveof society without it. Within the history of the UnitedStates the system of slavery immediately comes to mind.Although as early as the American Revolution antislaveryadvocates promoted the elimination of African bondage, ittook almost a century to achieve the abolition of the "peculiarinstitution." White antislavery abolitionists such as JohnBrown and William Lloyd Garrison were represented in the22dominant media of the period as extremists and fanatics.When Frederick Douglass embarked on his career as an antislaveryorator, white people-even those who were passionateabolitionists-refused to believe that a black slave coulddisplay such intelligence. The belief in the permanence ofslavery was so widespread that even white abolitionistsfound it difficult to imagine black people as equals.It took a long and violent civil war in order to legally disestablishthe "peculiar institution. II Even though theThirteenth Amendment to the u.s. Constitution outlawedinvoluntary servitude, white supremacy continued to beembraced by vast numbers of people and became deeplyinscribed in new institutions. One of these post-slaveryinstitutions was lynching, which was widely accepted formany decades thereafter. Thanks to the work of figures suchas Ida B. Wells, an antilynching campaign was graduallylegitimized during the first half of the twentieth century.The NAACP, an organization that continues to conductlegal challenges against discrimination, evolved from theseefforts to abolish lynching.Segregation ruled the South until it was outlawed a centuryafter the abolition of slavery. Many people who livedunder Jim Crow could not envision a legal system defined byracial equality. When the governor of Alabama personallyattempted to prevent Arthurine Lucy from enrolling in theUniversity of Alabama, his stance represented the inabilityto imagine black and white people ever peaceably living andstudying together. "Segregation today, segregation tomorrow,segregation forever" are the most well known words ofthis politician, who was forced to repudiate them someyears later when segregation had proved far more vulnerablethan he could have imagined.Although government, corporations, and the dominantARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? 123

me dia try to represent racism as an unfort un ate abe rration ofthe past that has been re le gate d to the graveyard of u.s. history,it continues to profoundly in flue nce co ntemporarystructures, attitudes, and be havio rs. Nevertheless, anyo newho wo uld dare to call fo r the reintro duct io n of slavery, theorganizat io n of lynch mobs, or the reestablishme nt of le galsegre gatio n wo uld be summarily dismissed. But it should beremembered that the an cestors of many of to day's mostardent libe rals co uld not have im agi ne d life wit ho ut slavery,life wit ho ut lynching, or life without se gregation. The 2001Wo rld Conference Against Racism , Racial Discrim in at io n,Xenophobia, and Re lated Intolerances he ld in Durban, SouthAfrica, div ulge d the immensity of the global task of elim inatingracism . The re may be many disagreements re garding whatco unts as racism and what are the most effective strategies toelim in ate it. Ho wever, espe cially wit h the do wnfal l of theap art heid re gime in South Africa, there is a global co nsensusthat racism should not de fine the fut ure of the planet.I have re ferre d to these historical ex amples of effo rts todism ant le racist inst itutions be cause they have co ns ide rablere levance to our dis cussion of prisons and prison abo lit io n. Itis true that slavery, lyn ching, and segregation acquire d sucha stalwart ideologi cal quality that many, if not most, co uldnot fo resee their de cline and co llapse. Slave ry, lyn ching, an dse gre gat ion are ce rt ainly compe llin g ex amples of so cial inst itutions that, like the prison, we re once co ns idered to be aseve rlasting as the sun. Yet, in the case of all three examples,we can point to movements that assumed the radical stanceof anno uncing the obsolescence of these institutions. It mayhe lp us gain perspective on the prison if we try to im agineho w stran ge and dis comforting the de bates about the obso lescence of slavery must have been to those who took the"pe culiar institution" fo r granted-an d espe cially to those24 1 Angela Y. Daviswho re aped dire ct benefits from this dre adful system of racistexploitation . And even though there was widespread resist ance among black slaves, there we re even some among themwho assumed that they and their progeny wo uld be alwayssubje cte d to the tyranny of slave ry.I have intro duce d three abo lit io n campaigns that we reeventually mo re or less successful to make the point thatso cial circumstances transform an d popular attit udes shift,in part in re spo nse to organize d so cial movements . But Ihave also evoked these historical campaigns be cause they alltargete d some expression of racism. U. S. chattel slavery wasa system of force d labor that re lie d on racist ide as and be liefsto justify the re le gation of people of African descent to thele gal st at us of property. Lynching was an extrale gal institutionthat surren de re d thousands of African-Ame rican livesto the violence of rut hless racist mobs. Un der segre gat io n,black people we re le gally de clare d se cond-class cit izens, fo rwhom voting, jo b, educat io n, an d ho us ing ri ghts we re drasticallycurt aile d, if they we re av ailable at all.What is the re lations hip between these historical expressionsof racism an d the ro le of the prison system today?Explo ring such co nnections may offe r us a diffe rent pe rspectiveon the current state of the punishme nt industry. If weare alre ady persuaded that racism should not be allowe d tode fine the planet's fut ure an d if we can success fully arguethat prisons are racist institutions, this may le ad us to takese rious ly the prospe ct of de claring prisons obso lete.Fo r the moment I am co ncentrat in g on the history ofantiblack racism in orde r to make the point that the priso nreveals co nge ale d fo rms of antiblack racism that ope rate inclandest ine ways. In other words , they are rarely re co gnizedas racist. But there are other racialize d histories that haveaffe cted the deve lopment of the U. S. punis hment system asARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? 125

well-the histories of Latinos, Native Americans, andAsian-Americans. These racisms also congeal and combinein the prison. Because we are so accustomed to talking aboutrace in terms of black and white, we often fail to recognizeand contest expressions of racism that target people of colorwho are not black. Consider the mass arrests and detentionof people of Middle Eastern, South Asian, or Muslim heritagein the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attacks onthe Pentagon and World Trade Center.This leads us to two important questions: <strong>Are</strong> prisonsracist institutions? Is racism so deeply entrenched in theinstitution of the prison that it is not possible to eliminateone without eliminating the other? These are questions thatwe should keep in mind as we examine the historical linksbetween U.S. slavery and the early penitentiary system. Thepenitentiary as an institution that simultaneously punishedand rehabilitated its inhabitants was a new system of punishmentthat first made its appearance in the United Statesaround the time of the American Revolution. This new systemwas based on the replacement of capital and corporalpunishment by incarceration.Imprisonment itself was new neither to the United Statesnor to the world, but until the creation of this new institutioncalled the penitentiary, it served as a prelude to punishment.People who were to be subjected to some form of corporalpunishment were detained in prison until the executionof the punishment. With the penitentiary, incarcerationbecame the punishment itself. As is indicated in the designation"penitentiary," imprisonment was regarded as rehabilitativeand the penitentiary prison was devised to provideconvicts with the conditions for reflecting on their crimesand, through penitence, for reshaping their habits and eventheir souls. Although some antislavery advocates spoke out26 1 Angela Y. Davisagainst this new system of punishment during the revolutionaryperiod, the penitentiary was generally viewed as aprogressive reform, linked to the larger campaign for therights of citizens.In many ways, the penitentiary was a vast improvementover the many forms of capital and corporal punishmentinherited from the English. However, the contention thatprisoners would refashion themselves if only given theopportunity to reflect and labor in solitude and silence disregardedthe impact of authoritarian regimes of living andwork. Indeed, there were significant similarities betweenslavery and the penitentiary prison. Historian Adam JayHirsch has pointed out:One may perceive in the penitentiary many reflectionsof chattel slavery as it was practiced in theSouth. Both institutions subordinated their subjectsto the will of others. Like Southern slaves, prisoninmates followed a daily routine specified by theirsuperiors. Both institutions reduced their subjects todependence on others for the supply of basic humanservices such as food and shelter. Both isolated theirsubjects from the general population by confiningthem to a fixed habitat. And both frequently coercedtheir subjects to work, often for longer hours and forless compensation than free laborers.l6As Hirsch has observed, both institutions deployed similarforms of punishment, and prison regulations were, in fact,very similar to the Slave Codes-the laws that deprivedenslaved human beings of virtually all rights. Moreover, bothprisoners and slaves were considered to have pronouncedproclivities to crime. People sentenced to the penitentiary inARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? 127

the North, white and black alike, were popularly representedas having a strong kinship to enslaved black people.17The ideologies governing slavery and those governingpunishment were profoundly linked during the earliestperiod of U.S. history. While free people could be legallysentenced to punishment by hard labor, such a sentencewould in no way change the conditions of existence alreadyexperienced by slaves. Thus, as Hirsch further reveals,Thomas Jefferson, who supported the sentencing of convictedpeople to hard labor on road and water projects, alsopointed out that he would exclude slaves from this sort ofpunishment. Since slaves alreadyhard labor, sentencingthem to penal labor would not mark a difference intheir condition. Jefferson suggested banishment to othercountries instead. isParticularly in the United race has always playeda central role in constructing presumptions of criminality.After the abolition of slavery, former slave states passednew legislation revising the Slave Codes in order to regulatethe behavior of free blacks in ways similar to those that hadexisted during slavery. The new Black Codes proscribed arange of actions-such as vagrancy, absence from work,breach of job contracts, the possession of firearms, andinsulting gestures or acts-that were criminalized onlywhen the person charged was black. With the passage of theThirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, slavery andinvoluntary servitude were putatively abolished. However,there was a significant exception. In the wording of theamendment, slavery and involuntary servitude were abolished"except as a punishment for crime, whereof the partyshall have been duly convicted. II According to the BlackCodes, there were crimes defined by state law for whichonly black people could be "duly convicted." Thus, former28 I Angela Y. Davisslaves, who had recently been extricated from a eonditionof hard labor for life, could be legally sentenced to penalservitude.In the immediate aftermath of slavery, the southern stateshastened to develop a criminal justice system that couldlegally restrict the possibilities of freedom for newly releasedslaves. Black people became the prime targets of a developingconvict lease system, referred to by many as a reincarnationof slavery. The Mississippi Black Codes, for example,declared vagrant /I anyone/who was guilty of theft, had runaway [from a job, apparently], was drunk, was wanton in conductor speech, had neglected job or family, handled moneycarelessly, and ... all other idle and disorderly persons."19Thus, vagrancy was coded as a black crime, one punishableby incarceration and forced labor, sometimes on the veryplantations that previously had thrived on slave labor.Mary Ellen Curtin's study of Alabama prisoners duringthe decades following emancipation discloses that before thefour hundred thousand black slaves in that state were setfree, ninety-nine percent of prisoners in Alabama's penitentiarieswere white. As a consequence of the shifts provokedby the institution of the Black Codes, within a short periodof time, the overwhelming majority of Alabama's convictswere black.2o She further observes:Although the vast majority of Alabama's antebellumwere white, the popular perceptionwas that the South's true criminals were its blackslaves. the 1870s the growing number ofblack prisoners in the South further buttressed thebelief that African Americans were inherentlycriminal and, in particular, prone to larceny.21ARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? ! 29

In 1883, Frederick Douglass had already written aboutthe South's tendency to "impute crime to color."22 When aparticularly egregious crime was committed, he noted, notonly was guilt frequently assigned to a black person regardlessof the perpetrator's race, but white men sometimessought to escape punishment by disguising themselves asblack. Douglass would later recount one such incident thattook place in Granger County, Tennessee, in which a manwho appeared to be black was shot while committing a robbery.The wounded man, however, was discovered to be arespectable white citizen who had colored his face black.The above example from Douglass demonstrates howwhiteness, in the words of legal scholar Cheryl Harris, operatesas property.23 According to Harris, the fact that whiteidentity was possessed as property meant that rights, liberandself-identity were affirmed for white people, whilebeing denied to black people. The latter's only access towhiteness was through "passing." Douglass's commentsindicate how this property interest in whiteness was easilyreversed in schemes to deny black people their rights to dueprocess. Interestingly, cases similar to the one Douglass discussesabove emerged in the United States during the 1990s:in Boston, Charles Stuart murdered his pregnant wife andattempted to blame an anonymous black man, and inUnion, South Carolina, Susan Smith killed her children andclaimed they had been abducted by a black carjacker. Theracialization of crime-the tendency to "impute crime tocolor," to use Frederick Douglass's words-did not witheraway as the country became increasingly removed fromslavery. Proof that crime continues to be imputed to colorresides in the many evocations of "racial profiling" in ourtime. That it is possible to be targeted by the police for noother reason than the color of one's skin is not mere specu-30 I Angela Y. Davislation. Police departments in major urban areas have admittedthe existence of formal procedures designed to maximizethe numbers of African-Americans and Latinos arrestedevenin the absence of probable cause. In the aftermath ofthe September 11 attacks, vast numbers of people of MiddleEastern and South Asian heritage were arrested and detainedby the police agency known as Immigration andNaturalization Services (INS). The INS is the federal agencythat claims the largest number of armed agents, even morethan the FBJ.24During the post-slavery era, as black people were integratedinto southern penal systems--and as the penal systembecame a system of penal servitude-the punishmentsassociated with slavery became further incorporated intothe penal system. "Whipping," as Matthew Mancini hasobserved, "was the preeminent form of punishment underslaverYi and the lash, along with the chain, became the veryemblem of servitude for slaves and prisoners. "25 As indicatedabove, black people were imprisoned under the lawsassembled in the various Black Codes of the southern states,which, because they were rearticulations of the Slave Codes,tended to racialize penality and link it closely with previousregimes of slavery. The expansion of the convict lease systemand the county chain gang meant that the antebellumcriminal justice system, which focused far more intenselyon black people than on whites, defined southern criminaljustice largely as a means of controlling black labor.According to Mancini:Among the multifarious debilitating legacies ofslavery was the conviction that blacks could onlylabor in a certain way-the way experience hadshown them to have labored in the past: in gangs,ARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? 131

subjected to constant supervision, and under thediscipline of the lash. Since these were the requisitesof slavery, and since slaves were blacks,Southern whites almost universally concluded thatblacks could not work unless subjected to suchintense surveillance and discipline.26Scholars who have studied the convict lease system pointout that in many important respects, convict leasing was farworse than slavery, an insight that can be gleaned from titlessuch as One Dies, Get Another (by Mancini), Worse ThanSlavery (David Oshinsky's work on Parchman Prison),27 andTwice the Work of Free Labor (Alex Lichtenstein's examinationof the political economy of convict leasing).28 Slaveowners may have been concerned for the survival of individualslaves, who, after all, represented significant investments.Convicts, on the other hand, were leased not as individuals,but as a group, and they could be worked literally todeath without affecting the profitability of a convict crew.According to descriptions by contemporaries, the conditionsunder which leased convicts and county chain gangslived were far worse than those under which black peoplehad lived as slaves. The records of Mississippi plantations inthe Yazoo Delta during the late 1880s indicate thatthe prisoners ate and slept on bare ground, withoutblankets or mattresses, and often without clothes.They were punished for "slow hoeing" (ten lashes),"sorry planting" (five lashes), and "being light withcotton"(five lashes). Some who attempted toescape were whipped" till the blood ran down theirlegs"; others had a metal spur riveted to their feet.Convicts dropped from exhaustion, pneumonia,32 1 Angela Y. Davismalaria, frostbite, consumption, sunstroke, dysentery,gunshot wounds, and "shaclde poisoning" (theconstant rubbing of chains and leg irons againstbare £leshJ.29The appalling treatment to which convicts were subjectedunder the lease system recapitulated and further extendedthe regimes of slavery. If, as Adam Tay Hirsch contends,the early incarnations of the U.S. penitentiary in the Northtended to mirror the institution of slavery in many importantrespects, the post-Civil War evolution of the punishmentsystem was in very literal ways the continuation of aslave system, which was no longer legal in the "free" world.The population of convicts, whose racial composition wasdramatically transformed by the abolition of slavery, couldbe subjected to such intense exploitation and to such horrendousmodes of punishment precisely because they continuedto be perceived as slaves.Historian Mary Ann Curtin has observed that many scholarswho have acknowledged the deeply entrenched racism ofthe post-Civil War structures of punishment in the South havefailed to identify the extent to which racism colored commonsenseunderstandings of the circumstances surrounding thewholesale criminalization of black communities. Evenantiracist historians, she contends, do not go far enough inexamining the ways in which black people were made intocriminals. They point out-and this, she says, is indeed partiallytrue-that in the aftermath of emancipation, large numbersof black people were forced by their new social situationto steal in order to survive. It was the transformation of pettythievery into a felony that relegated substantial numbers ofblack people to the "involuntary servitude" legalized by theThirteenth Amendment. What Curtin suggests is that theseARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? 133

charges of theft were frequently fabricated outright. They"also served as subterfuge for political revenge. After emancipationthe courtroom became an ideal place to exact racial retribution."3oIn this sense, the work of the criminal justice systemwas intimately related to the extralegal work of lynching.Alex Lichtenstein, whose study focuses on the role of theconvict lease system in forging a new labor force for theSouth, identifies the lease system, along with the new JimCrow laws, as the central institution in the development ofa racial state.New South capitalists in Georgia and elsewherewere able to use the state to recruit and discipline aconvict labor force, and thus were able to developtheir states' resources without creating a wage laborforce, and without undermining planters' control ofblack labor. In fact, quite the opposite: the penalsystem could be used as a powerful sanction againstrural blacks who challenged the racial order uponwhich agricultural labor control relied.31Lichtenstein discloses, for example, the extent to whichthe building of Georgia railroads during the nineteenth centuryrelied on black convict labor. He further reminds usthat as we drive down the most famous street in AtlantaPeachtree Street-we ride on the backs of convicts: "[TJherenowned Peachtree Street and the rest of Atlanta's wellpavedroads and modern transportation infrastructure,which helped cement its place as the commercial hub of themodern South, were originally laid by convicts."32Lichtenstein's major argument is that the convict leasewas not an irrational regression; it was not primarily athrowback to precapitalist modes of production. Rather, it34 I Angela Y. Daviswas a most efficient and most rational deployment of raciststrategies to swiftly achieve industrialization in the South.In this sense, he argues, "convict labor was in many ways inthe vanguard of the region's first tentative, ambivalent, stepstoward modernity."33Those of us who have had the opportunity to visit nineteenth-centurymansions that were originally constructedon slave plantations are rarely content with an aestheticappraisal of these structures, no matter how beautiful theymay be. Sufficient visual imagery of toiling black slaves circulateenough in our environment for us to imagine the brutalitythat hides just beneath the surface of these wondrousmansions. We have learned how to recognize the role ofslave labor, as well as the racism it embodied. But black convictlabor remains a hidden dimension of our history. It isextremely unsettling to think of modern, industrializedurban areas as having been originally produced under theracist labor conditions of penal servitude that are oftendescribed by historians as even worse than slavery.I grew up in the city of Birmingham, Alabama. Because ofits mines-coal and iron ore-and its steel mills thatremained active until the deindustrialization process of the1980s, it was widely known as "the Pittsburgh of theSouth." The fathers of many of my friends worked in thesemines and mills. It is only recently that I have learned thatthe black miners and steelworkers I knew during my childhoodinherited their place in Birmingham's industrial developmentfrom black convicts forced to do this work under thelease system. As Curtin observes,Many ex-prisoners became miners because Alabamaused prison labor extensively in its coalmines. By1888 all of Alabama's able male prisoners were leasedARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? I 35

to two major mining companies: the Tennessee Coaland Iron Company (TCI) and Sloss Iron and SteelCompany. For a charge of up to $18.50 per month perman, these corporations "leased," or rented prisonlaborers and worked them in coalmines.34Learning about this little-acknowledged dimension ofblack and labor history has caused me to reevaluate my ownchildhood experiences.One of the many ruses racism achieves is the virtual erasureof historical contributions by people of color. Here wehave a penal system that was racist in many respects-discriminatoryarrests and sentences, conditions of work,modes of punishment-together with the racist erasure ofthe significant contributions made by black convicts as aresult of racist coercion. Just as it is difficult to imagine howmuch is owed to convicts relegated to penal servitude duringthe nineteenth and twentieth centuries, we find it difficulttoday to feel a connection with the prisoners who produce arising number of commodities that we take for granted in ourdaily lives. In the state of California, public colleges and universitiesare provided with furniture produced by prisoners,the vast majority of whom are Latino and black.There are aspects of our history that we need to interrogateand rethink, the recognition of which may help us toadopt more complicated, critical postures toward the presentand the future. I have focused on the work of a few scholarswhose work urges us to raise questions about the past,present, and future. Curtin, for example, is not simply contentwith offering us the possibility of reexamining the placeof mining and steelwork in the lives of black people inAlabama. She also uses her research to urge us to thinkabout the uncanny parallels between the convict lease sys-36 I Angela Y. Davistem in the nineteenth century and prison privatization inthe twenty-first.In the late nineteenth century, coal companieswished to keep their skilled prison laborers for aslong as they could, leading to denials of "shorttime. " Today, a slightly different economic incentivecan lead to similar consequences. CCA[Corrections Corporation of America] is paid perprisoner. If the supply dries up, or too many arereleased too early, their profits are affected . . .Longer prison terms mean greater profits, but thelarger point is that the profit motive promotes theexpansion of imprisonment.35The persistence of the prison as the main form of punishment,with its racist and sexist dimensions, has createdthis historical continuity between the nineteenth- and earlytwentieth-centuryconvict lease system and the privatizedprison business today. While the convict lease system waslegally abolished, its structures of exploitation havereemerged in the patterns of privatization, and, more generally,in the wide-ranging corporatization of punishment thathas produced a prison industrial complex. If the prison continuesto dominate the landscape of punishment throughoutthis century and into the next, what might await cominggenerations of impoverished African-Americans, Latinos,Native Americans, and Asian-Americans? Given the parallelsbetween the prison and slavery, a productive exercisemight consist in speculating about what the present mightlook like if slavery or its successor, the convict lease system,had not been abolished.To be sure, I am not suggesting that the abolition of slav-ARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? 137

ery and the lease system has produced an era of equality andjustice. On the contrary, racism surreptitiously definessocial and economic structures in ways that are difficult toidentify and thus are much more damaging. In some states,for example, more than one-third of black men have beenlabeled felons. In Alabama and Florida, once a felon, alwaysa felon, which entails the loss of status as a rights-bearingcitizen. One of the grave consequences of the powerful reachof the prison was the 2000 (sJelection of George W. Bush aspresident. If only the black men and women denied the rightto vote because of an actual or presumed felony record hadbeen allowed to cast their ballots, Bush would not be in theWhite House today. And perhaps we would not be dealingwith the awful costs of the War on Terrorism declared duringthe first year of his administration. If not for his election,the people of Iraq might not have suffered death, destruction,and environmental poisoning by u.s. military forces.As appalling as the current political situation may be,imagine what our lives might have become if we were stillgrappling with the institution of slavery-or the convictlease system or racial segregation. But we do not have tospeculate about living with the consequences of the prison.There is more than enough evidence in the lives of men andwomen who have been claimed by ever more repressiveinstitutions and who are denied access to their families,their communities, to educational opportunities, to productiveand creative work, to physical and mental recreation.And there is even more compelling evidence about the damagewrought by the expansion of the prison system in theschools located in poor communities of color that replicatethe structures and regimes of the prison. When childrenattend schools that place a greater value on discipline andsecurity than on knowledge and intellectual development,38 I Angela Y. Davisthey are attending prep schools for prison. If this is thepredicament we face today, what might the future hold if theprison system acquires an even greater presence in our society?In the nineteenth century, antislavery activists insistedthat as long as slavery continued, the future of democracywas bleak indeed. In the twenty-first century, antiprisonactivists insist that a fundamental requirement for the revitalizationof democracy is the long-overdue abolition of theprison system.ARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? 139

3Imprison ment andReform"One should recall that the movement for reforming theprisons, for controlling their functioning is not a recentphenomenon. It does not even seem to have originated ina recognition of failure. Prison 'reform' is virtually contemporarywith the prison itself: it constitutes, as it were,its programme."-Michel Foucault36It is ironic that the prison itself was a product of concertedefforts by reformers to create a better system of punishment.If the words "prison reform" so easily slip from our lips, it isbecause "prison" and "reform" have been inextricablylinked since the beginning of the use of imprisonment as themain means of punishing those who violate social norms.As I have already indicated, the origins of the prison areassociated with the American Revolution and therefore withthe resistance to the colonial power of England. Today thisseems ironic, but incarceration within a penitentiary wasassumed to be humane-at least far more humane than thecapital and corporal punishment inherited from England andother European countries. Foucault opens his study,Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, with aic description of a 1757 execution in Paris. The man whowas put to death was first forced to undergo a series of formidabletortures ordered by the court. Red-hot pincers were40used to burn away the flesh from his limbs, and molten lead,boiling oil, burning resin, and other substances were meltedtogether and poured onto the wounds. Finally, he was drawnand quartered, his body burned, and the ashes tossed intothe wind.37 Under English common law, a conviction forsodomy led to the punishment of being buried alive, andconvicted heretics also were burned alive. "The crime oftreason by a female was punished initially under the commonlaw by burning alive the defendant. However, in theyear 1790 this method was halted and the punishmentbecame strangulation and burning of the corpse."38European and American reformers set out to end macabrepenalties such as this, as well as other forms of corporal punishmentsuch as the stocks and pillories, whippings, brandings,and amputations. Prior to the appearance of punitiveincarceration, such punishment was designed to have itsmost profound effect not so much on the person punished ason the crowd of spectators. Punishment was, in essence,public spectacle. Reformers such as John Howard in Englandand Benjamin Rush in Pennsylvania argued that punishment-ifcarried out in isolation, behind the walls of theprison-would cease to be revenge and would actuallyreform those who had broken the law.It should also be pointed out that punishment has not beenwithout its gendered dimensions. Women were often punishedwithin the domestic domain, and instruments of torturewere sometimes imported by authorities into the household.In seventeenth-century Britain, women whose husbands identifiedthem as quarrelsome and unaccepting of male dominancewere punished by means of a gossip's bridle, orilbranks, " a headpiece with a chain attached and an iron bitthat was introduced into the woman's mouth.39 Although thebranking of women was often linked to a public parade, thisARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? 141

contraption was sometimes hooked to a wall of the house,where the punished woman remained until her husbanddecided to release her. I mention these forms of punishmentinflicted on women because, like the punishment inflicted onslaves, they were rarely taken up by prison reformers.Other modes of punishment that predated the rise of theprison include banishment, forced labor in galleys, transportation,and appropriation of the accused's property. Thepunitive transportation of large numbers of people fromEngland, for example, facilitated the initial colonization ofAustralia. Transported English convicts also settled theNorth American colony of Georgia. During the early 1700s,one in eight transported convicts were women, and the workthey were forced to perform often consisted of prostitution.40Imprisonment was not employed as a principal mode ofpunishment until the eighteenth century in Europe and thenineteenth century in the United States. And Europeanprison systems were instituted in Asia and Africa as animportant component of colonial rule. In India, for example,the English prison system was introduced during the secondhalf of the eighteenth century, when jails were establishedin the regions of Calcutta and Madras. In Europe, the penitentiarymovement against capital and other corporal punishmentsreflected new intellectual tendencies associatedwith the Enlightenment, actIVIst interventions byProtestant reformers, and structural transformations associatedwith the rise of industrial capitalism. In Milan in 1764,Cesare Beccaria published his Essay on Crimes andPunishments,41 which was strongly influenced by notions ofequality advanced by the philosophes-especially Voltaire,Rousseau, and Montesquieu. Beccaria argued that punishmentshould never be a private matter, nor should it be arbitrarilyviolent; rather, it should be public, swift, and as42 I Angela Y. Davislenient as possible. He revealed the contradiction of whatwas then a distinctive feature of imprisonment-the factthat it was generally imposed prior to the defendant's guiltor innocence being decided.However, incarceration itself eventually became thepenalty, bringing about a distinction between imprisonmentas punishment and pretrial detention or detention until theinfliction of punishment. The process through whichimprisonment developed into the primary mode of stateinflictedpunishment was very much related to the rise ofcapitalism and to the appearance of a new set of ideologicalconditions. These new conditions reflected the rise of thebourgeoisie as the social class whose interests and aspirationsfurthered new scientific, philosophical, cultural, andpopular ideas. It is thus important to grasp the fact that theprison as we know it today did not make its appearance onthe historical stage as the superior form of punishment forall times. It was simply-though we should not underestimatethe complexity of this process-what made most senseat a particular moment in history. We should therefore questionwhether a system that was intimately related to a particularset of historical circumstances that prevailed duringthe eighteenth and nineteenth centuries can lay absoluteclaim on the twenty-first century.It may be important at this point in our examination toacknowledge the radical shift in the social perception of theindividual that appeared in the ideas of that era. With therise of the bourgeoisie, the individual came to be regarded asa bearer of formal rights and liberties. The notion of the individual'sinalienable rights and liberties was eventuallymemorialized in the French and American Revolution."Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite" from the French Revolutionand "We hold these truths to be self-evident: all men are cre-ARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? 143

ated equal ... /J from the American Revolution were new andradical ideas, even though they were not extended towomen, workers, Africans! and Indians. Before the acceptanceof the sanctity of individual rights, imprisonmentcould not have been understood as punishment. If the individualwas not perceived as possessing inalienable rights andliberties, then the alienation of those rights and liberties byremoval from society to a space tyrannically governed by thestate would not have made sense. Banishment beyond thegeographical limits of the town may have made sense, butnot the alteration of the individual's legal status throughimposition of a prison sentence.Moreover, the prison sentence, which is always computedin terms of time, is related to abstract quantification,evoking the rise of science and wh;;tt is often referred to asthe Age of Reason. We should keep in mind that this wasprecisely the historical period when the value of labor beganto be calculated in terms of time and therefore compensatedin another quantifiable way, by money. The computabilityof state punishment in terms ofmonths,years-resonates with the role of labor-time as the basis forcomputing the value of capitalist commodities. Marxist theoristsof punishment have noted that precisely the historicalperiod during which the commodity form arose is the eraduring which penitentiary sentences emerged as the primaryform of punishment.42Today, the growing social movement contesting thesupremacy of global capital is a movement that directly challengesthe rule of thehuman, animal, and plantpopulations, as well as its natural resources-by corporationsthat are primarily interested in the increased production andcirculation of ever more profitable commodities. This is achallenge to the supremacy of the commodity form, a rising44 I Angela Y. Davisresistance to the contemporary tendency to commodifyevery aspect of planetary existence. The question we mightconsider is whether this new resistance to capitalist globalizationshould also incorporate resistance to the prison.Thus far I have largely used gender-neutral language todescribe the historical development of the prison and itsreformers. But convicts punished by imprisonment in emergentpenitentiary systems were primarily male. This reflectedthe deeply gender-biased structure of legal, political, andeconomic rights. Since women were largely denied publicstatus as rights-bearing individuals, they could not be easilypunished by the deprivation of such rights through imprisonment.43This was especially true of married women, whohad no standing before the law. According to English commonlaw, marriage resulted in a state of "civil death," assymbolized by the wife's assumption of the husband's name.Consequently, she tended to be punished for revoltingagainst her domestic duties rather than for failure in her meagerpublic responsibilities. The relegation of white women todomestic economies prevented them from playing acant role in the emergent commodity realm. This was especiallytrue since wage labor was typically gendered as maleand racialized as white. It is not fortuitous that domestic corporalpunishment for women survived long after these modesof punishment had become obsolete for (white) men. Thepersistence of domestic violence painfully attests to thesehistorical modes of gendered punishment.Some scholars have argued that the word "penitentiary"may have been used first in connection with plans outlinedin England in 1758 to house "penitent prostitutes./I In 1777,John Howard, the leading Protestant proponent of penalreform in England, published The State of the <strong>Prisons</strong>,44 inwhich he conceptualized imprisonment as an occasion forARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? I 45

eligious self-reflection and self-reform. Between 1787 and1791, the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham publishedhis letters on a prison model he called the panopticon.45Bentham claimed that criminals could only internalize productivelabor habits if they were under constant surveillance.According to his panopticon model, prisoners were tobe housed in single cells on circular tiers, all facing a multilevelguard tower. By means of blinds and a complicated playof light and darkness, the prisoners-who would not seeeach other at all-would be unable to see the warden. Fromhis vantage point, on the other hand, the warden would beable to see all of the prisoners. However-and this was themost significant aspect of Bentham's mammoth panopticon-becauseeach individual prisoner would never be ableto determine where the warden's gaze was focused, eachprisoner would be compelled to act, that is, work, as if hewere being watched at all times.If we combine Howard's emphasis on disciplined selfreflectionwith Bentham's ideas regarding the technology ofinternalization designed to make surveillance and disciplinethe purview of the individual prisoner, we can begin to seehow such a conception of the prison had far-reaching implications.The conditions of possibility for this new form ofpunishment were strongly anchored in a historical era duringwhich the working class needed to be constituted as an armyof self-disciplined individuals capable of performing the requisiteindustrial labor for a developing capitalist system.John Howard's ideas were incorporated in thePenitentiary Act of 1799, which opened the way for themodern prison. While Jeremy Bentham's ideas influencedthe development of the first national English penitentiary,located in Millbank and opened in 1816, the first full-fledgedeffort to create a panopticon prison was in the United States.46 I Angela Y. DavisThe Western State Penitentiary in Pittsburgh, based on arevised architectural model of the panopticon, opened in1826. But the penitentiary had already made its appearancein the United States. Pennsylvania's Walnut Street Jailhoused the first state penitentiary in the United States,when a portion of the jail was converted in 1790 from adetention facility to an institution housing convicts whoseprison sentences simultaneously became punishment andoccasions for penitence and reform.Walnut Street's austere regime-total isolation in singlecells where prisoners lived, ate, worked, read the Bible (if,indeed, they were literate), and supposedly reflected andrepented-came to be known as the Pennsylvania system.This regime would constitute one of that era's two majormodels of imprisonment. Although the other model, developedin Auburn, New York, was viewed as a rival to thePennsylvania system, the philosophical basis of the twomodels did not differ substantively. The Pennsylvaniamodel, which eventually crystallized in the Eastern StatePenitentiary in Cherry Hill-the plans for which wereapproved in 1821-emphasized total isolation, silence, andsolitude, whereas the Auburn model called for solitary cellsbut labor in common. This mode of prison labor, which wascalled congregate, was supposed to unfold in total silence.Prisoners were allowed to be with each other as theyworked, but only under condition of silence. Because of itsmore efficient labor practices, Auburn eventually becamethe dominant model, both for the United States and Europe.Why would eighteenth- and nineteenth-century reformersbecome so invested in creating conditions of punishmentbased on solitary confinement? Today, aside from death,solitary confinement-next to torture, or as a form of torture-isconsidered the worst form of punishment imagina-ARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? 147

le. Then, however, it was assumed to have an emaneipatoryeffect. The body was placed in conditions of se;relatLOnand solitude in order to allow the soul to flourish. It is notaccidental that most of the reformers of that era were deeplyreligious and therefore saw the architecture andthe penitentiary as emulating the architecture and regimesof monastic life. Still, observers of the new penitentiary saw,early on, the real potential for insanity in solitary confinement.In an often-quoted passage of his American Notes,Charles Dickens prefaced a description of his 1842 visit toEastern Penitentiary with the observation that "the systemhere is rigid, strict, and hopeless solitary confinement. Ibelieve it, in its effects, to be cruel and wrong."In its intention I am well convinced that it is kind,humane, and meant for reformation; but I am persuadedthat those who devised this system of PrisonDiscipline, and those benevolent gentlemen whocarry it into execution, do not know what it is thatthey are doing. I believe that very few men are capableof estimating the immense amount of torture andagony that this dreadful punishment, prolonged foryears, inflicts upon the sufferers . . . I am only themore convinced that there is a depth of terribleendurance in it which none but the sufferers themselvescan fathom, and which no man has a right toinflict upon his fellow-ereature. I hold this slow anddaily tampering with the mysteries of the brain to beimmeasurably worse than any torture of the body . ..because its wounds are not upon the surface, and itextorts few cries that human ears can hear; thereforeI the more denounce it, as a secret punishment whichslumbering humanity is not roused up to stay.4648 I Angela Y. DavisofUnlike other Europeans such as Alexis de Tocquevilleand Gustave de Beaumont, who believed that such punishmentwould result in moral renewal and thus mold convictsinto better citizens,47 Dickens was of the opinion that"[t]hose who have undergone this punishment MUST passinto society again morally unhealthy and diseased. "48 Thisearly critique of the penitentiary and its regime of solitaryconfinement troubles the notion that imprisonment is themost suitable form of punishment for a democratic society.The current constmction and expansion of state and federalsuper-maximum security prisons, whose putative purposeis to address disciplinary problems within the penalsystem, draws upon the historical conception of the penitentiary,then considered the most progressive form of punishment.Today African-Americans and Latinos are vastlyoverrepresented in these supermax prisons and controlunits, the first of which emerged when federal correctionalauthorities to send prisoners housed throughout thesystem whom they deemed to be /I dangerous" to the federalprison in Marion, Illinois. In 1983! the entire prison was"locked down,'! which meant that prisoners were confinedto their cells twenty-three hours a day. This lockdownbecame permanent, thus furnishing the general model forthe control unit and supermax prison.49 Today, there areapproximately super-maximum security federal andstate prisons located in thirty-six states and many moresupermax units in virtually every state in the country.A description of supermaxes in a 1997 Human RightsWatch report sounds chillingly like Dickens's description ofEastern State Penitentiary. What is different, however, isthat all references to individual rehabilitation have disappeared.ARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? 149

Inmates in super-maximum security facilities areusually held in single cell lock-down, commonlyreferred to as solitary confinement ...[C]ongregateactivities with other prisoners are usually prohibited;other prisoners cannot even be seen from aninmate's cell; communication with other prisonersis prohibited or difficult (consisting, forofshouting from cell to cell); visiting and telephoneprivileges are limited.5oThe new generation of super-maximum security facilitiesalso rely on state-of-the-art technology for monitoring andcontrolling prisoner conduct and movement, utilizing, forexample, video monitors and remote· controlled electronicdoors. 51 "These prisons represent the application of sophisticated,modern technology dedicatedto the task ofsocial control, and they isolate, regulate and surveil moreeffectively than anything that has preceded them."52I have highlighted the similarities between the early U.S.penitentiary-with its aspirations toward individual rehabil·itation-and the repressive supermaxes of our era as areminder of the mutability of history. What was onceregarded as progressive and even revolutionary representstoday the marriage of technological superiority and politicalbackwardness. No one-not even the most ardent defendersof the supermax-would try to argue today that absolutesegregation, including sensory deprivation, is restorative andhealing. The prevailing justification for the supermax is thatthe horrors it creates are the perfect complement for the hor·rHying personalities deemed the worst of the worst by theprison system. In other words, there is no pretense thatrights are respected, there is no concern for the individual,there is no sense that men and women incarcerated in super-50 I Angela Y. Davismaxes deserve anything approaching respect and eomfort.According to a 1999 report issued by the National Instituteof Corrections,Generally, the overall constitutionality of these[supermax] programs remains unclear. As largernumbers of inmates with a greaterof char·acteristics, backgrounds, and behaviors are incar·cerated in these facilities, the likelihood of legalchallenge is increased. 53During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, absolutesolitude and strict regimentation of the prisoner's everyaction were viewed as strategies for transforming habits andethics. That is to say, the idea that imprisonment should bethe main form of punishment reflected a belief in the potentialof white mankind for progress, not only in science andindustry, but at the level of the individual member of societyas well. Prison reformers mirrored Enlightenmentassumptions of progress in every aspect of human-or to bemore precise, white Western-society. In his 1987 studyImagining theFiction and the Architecture ofMind inEngland, John Bender proposesthe very intriguing argument that the emergent literary genreof the novel furthered a discourse of progress and individualtransformation that encouraged attitudes toward punish·ment toThese attitudes, he suggests, heralded theconception and construction of penitentiary prisons duringthe latter part of the eighteenth century as a reform suited tothe capacities of those who were deemed human.Reformers who called for the imposition of penitentiaryarchitecture and regimes on the then existing structure of theprison aimed their critiques at the prisons that were primari·ARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? ] 51

ly used for purposes of pretrial detention or as an alternativepunishment for those who were unable to pay fines exactedby the courts. John Howard, the most well known of thesereformers, was what you might today call a prison activist.Beginning in 1773, at the age of forty-seven, he initiated aseries of visits that took him "to every institution for thepoor in Europe . .. [a campaign] which cost him his fortuneand finally his life in a typhus war of the Russian army atCherson in 1791. "55 At the conclusion of his first trip abroad,he successfully ran for the office of sheriff in Bedfordshire. Assheriff he investigated the prisons under his own jurisdictionand later "set out to visit every prison in England and Walesto document the evils he had first observed at Bedford."56Bender argues that the novel helped facilitate these campaignsto transform the old prisons-which were filthy andin disarray, and which thrived on the bribery of the wardens-intowell-ordered rehabilitative penitentiaries. Heshows that novels such as Moll Flanders and RobinsonCrusoe emphasized "the power of confinement to reshapepersonality"57 and popularized some of the ideas that movedreformers to action. As Bender points out, the eighteenthcenturyreformers criticized the old prisons for their chaos,their lack of organization and classification, for the easy circulationof alcohol and prostitution they permitted, and forthe prevalence of contagion and disease.The reformers, primarily Protestant, among whomQuakers were especially dominant, couched their ideas inlarge part in religious frameworks. Though John Howardwas not himself a Quaker-he was an independentProtestant-nevertheless[h]e was drawn to Quaker asceticism and adoptedthe dress " of a plain Friend." His own brand of piety52 I Angela Y. Daviswas strongly reminiscent of the Quaker traditionsof silent prayer, "suffering" introspection, and faithin the illumining power of God's light. Quakers, fortheir part, were bound to be drawn to the idea ofimprisonment as a purgatory, as a forced withdrawalfrom the distractions of the senses into silent andsolitary confrontation with the self. Howard conceivedof a convict's process of reformation in termssimilar to the spiritual awakening of a believer at aQuaker meeting. 58However, according to Michael Ignatieff, Howard's contributionsdid not so much reside in the religiosity of hisreform efforts.The originality of Howard's indictment lies in its"scientific," not in its moral character. Elected aFellow of the Royal Society in 1756 and author ofseveral scientific papers on climatic variations inBedfordshire, Howard was one of the first philanthropiststo attempt a systematic statisticaldescription of a social problem. 59Likewise, Bender's analysis of the relationship betweenthe novel and the penitentiary emphasizes the extent towhich the philosophical underpinnings of the prisonreformer's campaigns echoed the materialism and utilitarianismof the English Enlightenment. The campaign toreform the prisons was a project to impose order, classification,cleanliness, good work habits, and self-consciousness.He argues that people detained within the old prisons werenot severely restricted-they sometimes even enjoyed thefreedom to move in and out of the prison. They were notARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? I 53

compelled to work and, depending on their own resources,could eat and drink as they wished. Even sex was sometimesavailable! as prostitutes were sometimes allowed temporaryentrance into the prisons. Howard and other reformerscalled for the imposition of rigid rules that would "enforcesolitude and penitence, cleanliness and work."60ilThe new penitentiaries," according to Bender, "supplantingboth the old prisons and houses of correction!explicitly reached toward . . . three goals: maintenance oforder within a largely urban labor force, salvation of thesoul, and rationalization of personality."61 He argues thatthis is precisely what was narratively accomplished by thenovel. It ordered and classified social life, it represented individualsas conscious of their surroundings and as self-awareand self-fashioning. Bender thus sees a kinship between twomajor developments of the eighteenth century-the rise ofthe novel in the cultural sphere and the rise of the penitentiaryin the socio-Iegal sphere. If the novel as a cultural formhelped to produce the penitentiary, then prison reformersmust have been influenced by the ideas generated by andthrough the eighteenth-century novel.Literature has continued to play a role in campaignsaround the prison. During the twentieth century, prison writing,in particular! has periodically experienced waves of popularity.The public recognition of prison writing in theUnited States has historically coincided with the influence ofsocial movements calling for prison reform and/or abolition.Robert Burns's I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chainand the 1932 Hollywood film upon which it wasbased, played a central role in the campaign to abolish thechain gang. During the 1970s, which were marked by intenseorganizing within, outside, and across prison walls, numerousworks authored by prisoners followed the 1970 publica-54 I Angela Y. Davistion of George Jackson's Soledad Brother63 and the anthologyI coedited with Bettina Aptheker, If They Come in theMorning.64 While many prison writers during that era haddiscovered the emancipatory potential of writing on theirown, relying either on the education they had received priorto their imprisonment or on their tenacious efforts at selfeducation,others pursued their writing as a direct result ofthe expansion of prison educational programs during that era.Mumia Abu-Jamal, who has challenged the contemporarydismantling of prison education programs, asks in Live fromDeath Row,What societal interest is served by prisoners whoremain illiterate? What social benefit is there inignorance? How are people corrected while imprisonedif their education is outlawed? Who profits(other than the prison establishment itself) fromstupid prisoners?65A practicing journalist before his arrest in 1982 on chargesof killing Philadelphia policeman Daniel Faulkner, AbuJamal has regularly produced articles on capital punishment,focusing especially on its racial and class disproportions. Hisideas have helped to link critiques of the death penalty withthe more general challenges to the expanding U.S. prison systemand are particularly helpful to activists who seek to associatedeath penalty abolitionism with prison abolitionism.His prison writings have been published in both popular andscholarly journals (such as The Nation and Yale Law Tournai)as well as in three collections, Live from Death Row, DeathBlossoms,66 and All Things Censored. 67Abu-Jamal and many other prison writers have stronglycriticized the prohibition of Pell Grants for prisoners, whichARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? I 55

was enacted in the 1994 crime bill,68 as indicative of thecontemporary pattern of dismantling educational programsbehind bars. As creative writing courses for prisoners weredefunded, virtually every literary journal publishing prisoners'writing eventually eollapsed. Of the scores of magazinesand newspapers produced behind walls, only the Angolite atLouisiana's Angola Prison and Prison Legal News atWashington State Prison remain. What this means is thatprecisely at a time of consolidating a significant writing culturebehind bars, repressive strategies are being deployed todissuade prisoners from educating themselves.If the publication of Malcolm X's autobiography marksa pivotal moment in the development of prison literatureand a moment of vast promise for prisoners who try tomake education a major dimension of their time behindbars,69 contemporary prison practices are systematicallydashing those hopes. In the 1950s, Malcolm's prison educationwas a dramatic example of prisoners' ability to turntheir incarceration into a transformative experience. Withno available means of organizing his quest for knowledge,he proceeded to read a dictionary, copying each word in hisown hand. By the time he could immerse himself in reading,he noted, "months passed without my even thinkingabout being imprisoned. In fact, up to then, I never hadbeen so truly free in my life."7o Then, aceording toMalcolm, prisoners who demonstrated an unusual interestin reading were assumed to have embarked upon a journeyof self-rehabilitation and were frequently allowed specialprivileges-such as checking out more than the maximumnumber of books. Even so, in order to pursue this self-education,Malcolm had to work against the prison regime-heoften read on his cell floor, long after lights-out, by theglow of the corridor light, talting care to return to bed each56 I Angela Y. Davishour for the two minutes during which the guard marchedpast his cell.The contemporary disestablishment of writing and otherprison educational programs is indicative of the official disregardtoday for rehabilitative strategies, particularly thosethat encourage individual prisoners to acquire autonomy ofthe mind. The documentary film The Last Graduationdescribes the role prisoners played in establishing a four-yearcollege program at New York's Greenhaven Prison and,twenty-two years later, the official decision to dismantle it.According to Eddie Ellis, who spent twenty-five years inprison and is currently a well-known leader of the antiprisonmovement, "As a result of Attica, college programs cameinto the prisons. II 71In the aftermath of the 1971 prisoner rebellion at Atticaand the government-sponsored massacre, public opinionbegan to favor prison reform. Forty-three Attica prisonersand eleven guards and civilians were killed by the NationalGuard, who had been ordered to retake the prison byGovernor Nelson Rockefeller. The leaders of the prisonrebellion had been very specific about their demands. Intheir "practical demands" they expressed concerns aboutdiet, improvement in the quality of guards, more realisticrehabilitation programs, and better education programs.They also wanted religious freedom, freedom to engage inpolitical activity, and an end to censorship-all of whichthey saw as indispensable to their educational needs. AsEddie Ellis observes in The Last Graduation,Prisoners very early recognized the fact that theyneeded to be better educated, that the more educationthey had, the better they would be able to dealwith themselves and their problems, the problemsARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? I 57

of the prisons and the problems of the communitiesfrom which most of them came.Lateef Islam, another former prisoner featured in thisdocumentary, said, "We held classes before thecame. We taught each other, and sometimes under penaltyof a beat-up."After the Attica Rebellion, more than five hundred prisonerswere transferred to Greenhaven, including some of theleaders who continued to press for educational programs. Asa direct result of their demands, Marist College, a New Yorkstate college near Greenhaven, began to offer college-levelcourses in 1973 and eventually established the infrastructurefor an on-site four-year college program. The programthrived for twenty-two years. Some of the many prisonerswho earned their degrees at Greenhaven pursued postgraduatestudies after their release. As the documentary powerfullydemonstrates, the program produced dedicated menwho left prison and offered their newly acquired knowledgeand skills to their communities on the outside.In 1994, consistent with the general pattern of creatingmore prisons and more repression within all prisons,Congress took up the question of withdrawing college fundingfor inmates. The congressional debate concluded with adecision to add an amendment to the 1994 crime bill thateliminated all Pell Grants for prisoners, thus effectivelydefunding all higher educational programs. After twentytwoyears, Marist College was compelled to terminate itsprogram at Greenhaven Prison. Thus, the documentaryrevolves around the very last graduation ceremony on JulyIS, 1995, and the poignant process of removing the booksthat, in many ways, symbolized the possibilities of freedom.Or, as one of the Marist professors said, "They see books as58 I Angela Y. Davisfull of gold." The prisoner who for many years had served asa clerk for the college sadly reflected, as books were beingmoved, that there was nothing left to do in prison-exceptperhaps bodybuilding. "But/' he asked, "what's the use ofbuilding your body if you can't build your mind?" Ironically,not long after educational programs were disestablished,weights and bodybuilding equipment were also removedfrom most U.S. prisons.ARE PRISONS OBSOLETE? I 59