Alumni Magazine Spring 2010 - Green Meadow Waldorf School

Alumni Magazine Spring 2010 - Green Meadow Waldorf School

Alumni Magazine Spring 2010 - Green Meadow Waldorf School

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Contents<strong>Alumni</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong><strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2010</strong>FeaturesFOUR FOR THE LAW: THE CLASS OF 1999CRIMINAL JUSTICE, Rose Rivera ‘99A LEGACY OF FREEDOM, Jennie Love ‘99A REASONABLE PERSON, Katusha Galitzine ‘99AMERICAN LAW AND CULTURE, Ariel Henderson ‘99ON THE STREETA GOOD AND FAIR COP, Ramona Ruud ’91LAW AND JUSTICE Stephanie Antes ‘00WASHINGTONGREED AND THE AMERICAN DREAM, Jonah Crane ‘96JUSTICE FOR CONFLICT AND POST-CONFICT STATESTRANSITIONAL JUSTICE, Leijla Zvizdic ‘07WAR IN TRANSLATION, Ann Hunkins ‘84DepartmentsCOMMUNITY NEWSStrategic Plan Update, Kay HoffmanNEWS FROM THE ALUMNI OFFICETEACHER FEATURE CHANGING OF THE GUARDJim Henderson: Science and the Man, Karl FredricksonLeah Henderson: Guiding Light, Kay HoffmanJohn Hoffman: Buzzy Blows up the Lab, David SloanKay Hoffman: First in her Class, John WulsinWHAT WOULD STEINER SAY?Choosing to Champion Others, Jane Wulsin<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2010</strong> | 1

ContentsFeaturesDepartmentsFour for the Law: The Class of 199910 American Law and Culture, Ariel Henderson ’9912 A Legacy of Freedom, Jennie Love ’9913 A Reasonable Person, Katusha Galitzine ’9914 Criminal Justice: At Home and Abroad, Rose Rivera ’99On the Street16 A Good and Fair Cop, Ramona Ruud ’9117 Law and Justice, Stephanie Antes ’00Washington19 Greed and the American Dream: Rethinking EconomicJustice in the Wake of the Great Recession, Jonah Crane ’96Justice for Conflict and Post-Conflict States22 Transitional Justice, Lejla Zvizdic ’9724 War in Translation, Ann Hunkins ’84Community News2 <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong> Strategic Plan Summary, Kay Hoffman3 New Beginnings, Ivy <strong>Green</strong>steinTeacher Feature: Changing of the Guard4 Jim Henderson: Science and the Man, Karl Fredrickson6 Leah Henderson: Guiding Light, Kay Hoffman7 John Hoffman: Buzzy Blows up the Lab, David Sloan8 Kay Hoffman: First in her Class, John WulsinWhat Would Steiner Say?28 Choosing to Champion Others, Jane Wulsin<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2010</strong> | 1

Community News<strong>School</strong> News<strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong> Strategic Plan SummaryKay Hoffman, AdministratorThree years ago, the<strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong> Boardof Directors began astrategic planning initiative.Under the leadership ofBoard member Jake Lynn,strategic planning sessionswere held during thefollowing year and a halfin meetings with parents,Five strategic initiatives wereidentified...with the intentionof strengthening...CommunityEngagement, <strong>School</strong> Finances,Facilities, Educational Programsand Faculty/Staff.the Parent Council, theCollegium, the full faculty,the Board and members ofour sister institutions. Afterthe data had been collected,the framework of the planwas created. In the springof 2009, that framework waspresented to the Board andCollegium for discussion andrevision. The final strategicplan was crafted last summerand approved by both Boardand Collegium last fall.While we understand thatcircumstances beyond ourcontrol, such as the economy,might stand in the way of ourachievement of all our goals,we aspire to the objectivesset forth in this document.Representing our goals andintentions, the Strategic Planserves as a road map for ourschool for the next five years.Five strategic initiatives wereidentified in the StrategicPlan, with the intention ofstrengthening these five areas:Community Engagement,<strong>School</strong> Finances, Facilities,Educational Programs andFaculty/Staff. While examiningall the initiatives, theoverarching objectives havebeen to develop a plan whichwould be fiscally, socially andenvironmentally responsible;assure the educationalphilosophy of Rudolf Steinerinforms our work; be clear andtransparent in communicatingour purpose and practice andbe open and collaborativewith parents in order to assurea healthy <strong>Waldorf</strong> schoolcommunity.To strengthen CommunityEngagement as a model forunderstanding communitymembers and the appropriateways to engage them, the plancalls for the implementationof a Communications Plancreated with consultant input,assurance that communitygatherings meet the social/intellectual/spiritual needs ofthe parents, improvement inthe process of welcoming/orienting new families andstrengthening work with classparents, Parent Council andschool committees to promoteand recognize volunteerism.To strengthen <strong>School</strong>Finances, the plan callsfor an assessment of thesoundness and resilienceof school finances throughunderstanding and adjustingthe forecasting models forenrollment, tuition, tuitionassistance, staffing, salariesand benefits, operatingexpenses, marketing andoutreach, cash flow, capitalprojects and investmentincome and reserves. Inthe area of Development,it calls for rebuilding theAnnual Fund target levelsand decreasing the cost ratioof raising funds, designing acampaign and soliciting fundsfor long-term endowmentplanning, increasingtuition assistance capacity,reevaluating tuition levels anddeveloping grant solicitation.To renew and expandFacilities, the plan calls forimprovement in the physicalplant facilities and theirutilization by developing asafety/aesthetics/functionalityaction plan for the campus,renewing existing buildingsand grounds, completingthe expansions andimprovements coveredunder the work of theProject ManagementGroup, exploring avenuesfor renewable energyand conservation, andinvestigating future capitalimprovements such as afamily center for the EarlyChildhood program.2 | <strong>Alumni</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>

Community NewsTo enhance the Educational Program,the plan calls for adaptation ofeducational capabilities and supportservices to meet the needs of ourstudents and families by addressingthe challenge of the eight-yearcycle, the middle school years,the transition between sections,determination of optimal class sizeand remedial education. The planalso calls for programs to supportstudents’ organizational functions andcoordination and dissemination ofresearch which impact and support theimplementation of <strong>Waldorf</strong> education,such as research about the impact ofmarketing and media on children.To strengthen Faculty and Staff,the plan calls for enhancingprofessional development andtraining opportunities for facultyand staff, creating a succession plan,strengthening the attractiveness ofworking at GMWS through competitivesalaries for faculty and supervisory staffand developing a stronger relationshipwith <strong>Waldorf</strong> training institutions toassure access to potential applicants.The plan asks the school to consideran internal teacher training internshipprogram with modest internshipsalaries offered. The plan calls for theadministration to shift non-pedagogicaltasks to staff or consultants in order togive teachers more time to work in thepedagogical domain.Although there are different groupsdesignated to follow through tocompletion on the plan, the Boardand Collegium will review the plan’stimeline and milestones twice ayear to assure that the plan is beingimplemented. There is an expectationthat the Strategic Plan will bereevaluated every two to three yearsto keep it current and relevant.Anyone who wishes to view the fullplan will find it on our website. qNews from the <strong>Alumni</strong> OfficeNew BeginningsIvy <strong>Green</strong>stein, Director of Outreachand <strong>Alumni</strong> RelationsAs mentioned elsewherein this issue, this springsees four longtime <strong>Green</strong><strong>Meadow</strong> teachers leaving theschool. As I write this, Leah andJim Henderson have already left“the Ridge” and are busy settingup their new home in the PacificNorthwest. Soon, Kay and JohnHoffman will be on their way, too,settling into their new home inthe mountains of New Mexico.Replacing Leah as high schoolguidance counselor is JoanneMonteleone; Maskit Ronen isteaching Jim’s high school lifescience classes, and Renate Kurthis taking over John’s high schoolchemistry blocks.Moving into Kay’s office is TariSteinrueck, whose experienceas Collegium and CollegiumCommittee member, High <strong>School</strong>Chair, Teacher DevelopmentCommittee Chair, ForeignExchange Coordinator, ClassAdvisor and AWSNA delegate—plus, her background as a<strong>Waldorf</strong> <strong>School</strong> graduate and<strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong> parent—makeher just the right person totake over the reins as schooladministrator.We look forward to forging newrelationships as we celebratepast traditions!Before the Hoffmans leave,there will be a “farewell sendoff”for them on the afternoonof Saturday, September 25, inthe GMWS Gym, to which thecommunity—including all ouralumni and alumni parents—isinvited. Please also join us earlierthat morning for a new GMWSevent: a 5K walk/run that willraise money for the school aswe showcase our campus andcommunity with a course thatruns through <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong>, theFellowship and Duryea Farm, andon local roads, including HungryHollow. It promises to be a funfilled—andmemory-making!—day. Please also save the dateof Saturday, October 16, for FallFair <strong>2010</strong> and join us there for the<strong>Alumni</strong> Gathering, <strong>Alumni</strong> Paneland <strong>Alumni</strong> Dinner.While I look forward to seeingyou at these upcoming events,it will not be in the capacity of<strong>Alumni</strong> Director. After three yearsin the <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong> alumnidepartment, I am moving onmyself, handing this importantresponsibility over to KatieBurns ’06, who is taking over as<strong>Alumni</strong> Relations Coordinator soI can focus exclusively on <strong>Green</strong><strong>Meadow</strong> outreach efforts. I havetruly enjoyed being the “keeper”of GMWS alumni, workingon behalf of alumni relations,publications and events. I feelhonored to have been entrustedwith this post and grateful to havebeen welcomed by everyone.I know you are in good handswith Katie, and I look forward towatching you together form thenext chapter of <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong>alumni relations. My best wishesto you all. q<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2010</strong> | 3

Teacher Feature: Changing of the Guardbuilt up the curriculum witha dedication that inspired usall. For Jim, biology in all itsforms—from plant studiesto embryology—gives onethe opportunity to combinerigorous scientific thinkingwith a sense for the artisticand a deep spiritual striving.Many of you will have hadthe experience I’ve oftenhad with Jim, that throughdescribing the workings ofliving things he can quicklylead you into the mysteriesnot only of biology, but of thehuman spirit. Where does thiscome from? To understandthis part of Jim, you needto go back well before hisstudies of biology at EasternMichigan University. I wouldtrace it to his interest inEastern religion that arose inhis days in the Navy, when heused shore leaves in Japanto soak in the quiet world ofTaoist temples.Jim was drawn back tothe East during his ‘07-08sabbatical year, travelingthrough China, Vietnam andIndia. Through his blogsof that year, you can gainincredible insights into theways of Eastern thought.Reading them makes it clearjust how profoundly he hascarried these thoughts withhim during his teachingyears and how much thishas influenced his approachto biology. For Jim, anysubject—whether biology, artor his other passion, history—provides the opportunity togo ever more deeply into themysteries of existence.Jim brought his powers ofcalm reflection to the businessof the school in many ways,most notably perhaps inhis years on the FinanceCommittee and his strongpresence on the Collegium.But I particularly rememberthe dedication with whichhe brought us together toparticipate in study groupsor to present the fruits of ourresearch to each other or tothe public. He also joinedwith his colleagues StephenEdelglass, John Hoffmanand David Booth to hostnumerous conferences forscience teachers, drawingto our campus such sciencegreats as John Davy, JoachimBochemuhl and Hans Gebert.Important publications onscience arose out of this work.Of course, it is the students ofthree decades who will carrysome of the strongest—andmost delightful—memoriesof Jim, whether it be hisenthusiasm for what jumpsout from a microscope, theway he slogged with themthrough the streams ofOrange County, the patientway he guided them throughquadratic formulas, or thefamous “lobster rap” skit heperformed at Hermit Island.Many of his students havecarried what they learnedinto fields such as medicine,biochemistry, dentistry,farming and ecology, whileothers have simply beeninspired to learn ever moreabout the amazing naturalworld around us.Jim is going off to a littlefarm near Eugene, Oregon,where, amidst his vegetablesand goats, he will continuehis passion for the world ofgrowing things and the worldof the human spirit. q(Top) Jim with daughters, Ariel andNaomi, at a Main House Easter EggHunt, 1987; (above) Jim working in thelibrary in the 1990s.<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2010</strong> | 5

Teacher Feature: Changing of the GuardLeah Henderson: Guiding LightKay Hoffman, AdministratorLeah Henderson was alreadya <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong> facultywife and mother when,in 1984, the school prevailedupon her to step into the role ofguidance counselor two days aweek. Over the years, as Leah’stwo daughters (Ariel ’99 andNaomi ‘01) grew, it becamepossible for her to work threedays, then four, and, starting in1990, a full five-day work week.She then took on high schoolEnglish teaching and classadvising.From the very beginning, Leahbrought energy, enthusiasm anda firm point of view to her workat <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong> with studentsand colleaguesalike. She did nothesitate to set upand take down forclass-sponsoredactivities, to engagein backbreakingwork alongside thestudents to fundraisefor a <strong>Waldorf</strong> schoolin China, to meetwith parents inevenings and onweekends to orientthem toward thecollege preparationprocess, to work withstudents interestedin maintaininga healthy socialatmosphere and toact as the longestserving member ofthe school’s CareGroup.Leah has ledcountless studentsthrough thecollege admissionsprocess with frank engagement,listening compassionately totheir worries and concerns. HerEnglish students can attest toher love of a good story and herability to relate experiences andthoughts so that the listeners aretransported out of the classroom.They respect her as a voraciousreader who wants to transmit herenthusiasm to her students.Those of us who have known Leahover the years also know her as adedicated mother, a master in thekitchen and in the garden, a worldtraveler and a poet. She expressesher love of life through doing.We will miss her energy, her styleand her spirit; perhaps most of all,we will miss her laughter whichhas cascaded beyond the wallsof her office all these years. Shewill certainly make retirement afulfilling and satisfying experiencebecause she always finds waysto be creative, productive andhelpful. Godspeed, dear Leah. q(Above, right) Leah as a new <strong>Spring</strong> Valley arrivee, 1979;(at left, top) Leah on an outing with her daughters, Naomi andAriel, 1991; (near left) Leah with a “<strong>Green</strong> Guerilla,” making acommunity garden with high school students in the 1990s.6 | <strong>Alumni</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>

Teacher Feature: Changing of the GuardJohn Hoffman: Buzzy Blows Up the LabDavid SloanMention JohnHoffman’s nameto the legions ofgrateful alumni who firstencountered the marvelsof chemistry in his classes,and they will all speak inexclamatory sentences.“Even as a veteran teacher,he was like a kid with his firstchemistry kit!”“His preamblein the lab wouldoften begin witha warning thathe wasn’t exactlysure what wouldhappen, but thingsblowing up was adistinct possibility!”“Kids didn’t needpencils and paper in this class.They needed those goofyprotective glasses!”Over the years, chemistry labwith Mr. Hoffman has been lesslike a class than an adventure.His enthusiasm for theunknown, for the experimentwith the uncertain outcome,stirred such interest in hisstudents that after an hourand-a-halfclass they oftenfound themselves startled atthe bell.He was one of the school’sfirst “swing” teachers, whoalternated between elementaryschool and high school math,and who was as responsible asanyone for helping to develop adependable math curriculum inthe middle school. For years, hewas a member of the Buildingsand Grounds Committee; noteacher cared more about orspent more time involved withthe maintenance and upkeep ofthe school. When school dancesgot too loud, itwas Mr. Hoffmanwho policed themwith his “decibelregister.”Perhaps mostmemorablyof all, JohnHoffman was theoriginator of thefabulous “Buzzy”stories, charming, riveting talesof John’s own childhood andearly adolescence growingup in the Catskills. Students,teachers and parents alikehave relished hearing Johnread one of his yarns about theRiver Rats and their run-inswith the notorious Truckergang, or about his growinginfatuation with the lovelyChristina Wexler. Authorand mad (cap) scientist,John Hoffman retires withhis <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong> legacysecure—in the words ofthe Buzzy trilogy, in the heartsof his ex-students andcolleagues, and in the“mistakes” staining the ceilingof the chemistry lab! qDavid Sloan taught Englishand drama in the GMWSHigh <strong>School</strong> from 1980-2006.He currently is foundingteacher and faculty memberat Merriconeag <strong>Waldorf</strong> High<strong>School</strong> in Freeport, Maine.(Above) JohnHoffman, c. 2000;(inset) Buzzy andthe River Rats: Book1, by John Hoffman;(lower left) Johnwith stepdaughterTeresa at LakeGeorge, 1986;(below) John andKay, 2001.However, his role as highschool chemistry teacherhas been only one of thecrucial roles John Hoffmanhas played at <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong>over the past three decades.<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2010</strong> | 7

Teacher Feature: Changing of the GuardKay Hoffman: First in Her ClassJohn Wulsin, HS English TeacherIwent through theFoundation Year and<strong>Waldorf</strong> Teacher Trainingat Emerson College in Sussex,England in 1971-1972 in thecompany not only of DavidSloan, but also with the(Top) Kay with son David at Emerson College, England,1972; (above) Pictured with her brother David, Kay as anew waitress at Threefold, 1964.flamboyant Roger Sciarretta,who was there accompaniedby his quiet, patient wife, Kay,watching and listening in theshadows while taking careof newborn David andimminent Peter.The next year, Roger andKay joined the ThreefoldEducational community,and Roger taught art in thefledgling <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong><strong>Waldorf</strong> High <strong>School</strong> whileKay taught one secondgrade class in 1974 beforeretiring to welcome the birthsof Christopher and, later,Teresa. At home with fouryoung children, Kay starteda small organic/biodynamicfood cooperative out of theirhouse. As the Co-op grew,Monica Alexandra and KarenMcCraken joined with Kay toexpand the Co-op, first intothe garage under the schoolgym and, later, into one of theThreefold Brookside houseswhen Christine Sloan joinedthe group. Twenty-five yearslater, the Hungry Hollow Coopis now a prominent, tricountyenterprise presidingover the corner of HungryHollow Road and Route 45.<strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong> was foundedin 1950. As the schoolapproached thirty years ofage, many of the original,founding teachers moved on,and new teachers took over,including Kay, who in 1981began teaching French parttime.In the same year, RogerSciarretta, who had beenserving as the chairperson ofthe whole school, left family,school and community. Intime, John Hoffman, part-timechemistry and math teacher,and Kay found each other,and Kay Frahm Sciarrettabecame Kay Hoffman. Shealso joined a largely malefaculty as a full-time teacher inthe High <strong>School</strong>, establishingthe French program and ourforeign student exchangeprogram.During the early 1990s, Kayripened into serving as theHigh <strong>School</strong> Chair, workingefficiently and increasinglywisely. After seventeen yearsof teaching high schoolFrench and fruitful workteaching Parzival in a variety ofcontexts, Kay’s success as High<strong>School</strong> Chair and the school’sgrowing need for governanceled Kay to contemplate adramatic shift in her calling.With the school’s blessing,Kay Hoffman became <strong>Green</strong><strong>Meadow</strong> <strong>Waldorf</strong> <strong>School</strong>’s firstadministrator in 1996/7.To her gifts of quiet, patient,attentive listening, KayHoffman added her capacitiesto think, speak and workefficiently in service to the workof the faculty, staff and studentsof the <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong> <strong>Waldorf</strong><strong>School</strong>. Teachers, accustomedto shouldering administrativeresponsibilities, were freedup to focus more fully ontheir teaching, supportedby an utterly trustworthycolleague. With Kay at theadministrative helm of theschool, <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong> wasfinally able to clarify its newlyindependent relationship withthe Threefold EducationalFoundation. <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong>’s8 | <strong>Alumni</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>

Teacher Feature: Changing of the Guardown Board of Trustees beganto function with newfoundidentity, purpose andresponsibility in the service ofthe pedagogical work of theteachers. The Collegium, thegroup of teachers carryingprimary responsibility for thepedagogical and spiritualwell-being and identity of theschool, worked with increasinghealth and capability. As aresult, the many vital schoolcommittees overseen by theCollegium Committee (asmall working committee ofthe Collegium chaired by Kayas the school administrator)became more effective.The Finance Committee,a committee of the <strong>Green</strong><strong>Meadow</strong> Board, functionedwith clarity, foresight andcompetence, working closelywith our Business Manager,Claus Sproll.When people needed tospeak, Kay listened. Herquiet became courage. Hertact became truth. When theschool needed to address adifficult truth, Kay could berelied upon to speak withthat truth, tact and courage,whether to an individualor a large group. Whereasshe naturally acted withthe healing gesture of theArchangel Raphael, Kaybecame increasingly masterfulof the courageous gestureof the Archangel Michael.Her profound respect forthe individual informedany interaction, whetherharmonious or challenging.With mischievous humor,Kay could often alleviate theheaviest of moments. Herattention has seemed topermeate every inch of theschool, twenty-four hours aday, twelve months a year.The primary context, thepriority in any issue, was alwaysthe well-being of the children.Now, as <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong><strong>Waldorf</strong> <strong>School</strong> approachesthe milestone of sixty yearsof operation, teachers of the“middle era,” including Kayand John, will conclude theiryears of dedicated serviceto the school, allowing newteachers to step forward asthe school anticipates andmoves into a new era.As inconceivable as it hasbeen to many of us to imagineworking here without Kay,we will, of course, continue,strengthened, inspired andwell-prepared by Kay’s owndedicated efforts on behalf ofthe school over the decades.Like Kay, we will rise to meetwhatever comes to us in thecourse of the ongoing lifeof the school. For a numberof years now, we haveanticipated this inevitabletransition and worked to laya solid foundation for theschool’s continued vitality,productivity and viability aswe embark upon the nextthirty years of <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong><strong>Waldorf</strong> <strong>School</strong>. Kay plansto provide the school withtransitional assistance in themonths to come.At the end of Wolfram vonEschenbach’s Parzival, Repansede Schoie, the bearer of theGrail, marries Parzival’s brother,Feirefiz, and journeys with himto the East. Kay Hoffman hasespecially tended to the wellbeingof <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong>. Asshe and John head west toSanta Fe, we wish her play andjoy, gratefully. q(Top) Kay helping at an event in Mary DaileyField, 1994; (center) Kay and John, 1985;(bottom) Kay with her children, David ‘89,Christopher ‘94 and Peter ‘91 Sciarretta andTeresa Sciarretta Bellaby ‘97, 2005.<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2010</strong> | 9

Four for the LawA Legacy of FreedomJennie Love ’99I daresay there aren’t manypeople who knew me at <strong>Green</strong><strong>Meadow</strong> who would havethought that I’d become anattorney. I began thinkingabout joining the militaryduring my junior year at<strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong> because Iwas fascinated by the factthat there were Americanswho were willing to volunteerfour years of their lives toensure the freedom of others.The ideal of individualfreedom began here, wherethe distilled knowledge ofhistory found a receptiveplace in the hearts of theFounders of our nation.I served four years in collegeas a ROTC cadet and almostfive additional years as anAir Force officer. When Iseparated from the military, Ientered law school.For me, becoming an attorneyfollowed naturally frommy years of servicewith the US AirForce. Spendingall of that time“serving mycountry”incited mycuriosity tolearn moreabout theframeworkupon which ourrepublic rests.I took to heartthe words of James Madison,perhaps the most influentialand prescient of our nation’sFounders, who said, “Theadvancement and diffusionof knowledge is the onlyguardian of true liberty.”My law studies have clarifiedfor me why I instinctivelyjoined and spent nine yearsin the Air Force. In thehistory of humankind, it isonly during the Americanexperiment of the last 250years that the rights of theindividual have been elevatedabove the demands of thestate and its aristocracy.The ideal of individualfreedom began here, wherethe distilled knowledge ofhistory found a receptiveplace in the hearts of theFounders of our nation. Theyrecorded, in the Declarationof Independence, the idealthat had been impressedupon their collective spirit,and then bestowed upon usthe Constitution—the legalconstruct within which we wereto pursue that ideal.People are the same the worldover and have been sincethe beginning of time. Whatsets us and our history apartis not our people, but ourConstitution. Its protectionshave cultivated humanfreedom and given rise to thecreativity and ingenuity whichhas enabled the greatestexplosion of human progressin history. History has shownus that it is only when peopleare free to share knowledgethat society truly flourishes.This spark that our Foundersignited has been shiningfor a relatively short time. Itis our duty, not only to ourfellow Americans, but to allpeople, to see that it is notextinguished.With graduation only a fewshort months away, I do notknow what the future holdsfor me. I do know that I willbe living in Tucson, Arizonaand, while I am no longerin the military, I hope, in mylegal career, to find a path thatwill allow me to continue tofight to preserve the vision ofour Founding Fathers—thistime wearing heels instead ofcombat boots. qJennie LoveattendedVanderbiltUniversity,graduating in2003 with aBA in East Asian Languages.Upon graduation, she wascommissioned as an officer inthe US Air Force. During heryears in the Air Force, shewas stationed in Texas, SouthKorea and North Carolina, anddeployed to Iraq. She is dueto graduate in May <strong>2010</strong> fromNotre Dame Law <strong>School</strong>.12 | <strong>Alumni</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>

Four for the LawA Reasonable PersonKatusha Galitzine ’99After earning a degreein writing, literature andpublishing, I spent the nextfour years working to influencelawmakers with my writing.Now I believe more than everthat the triumph or defeatof justice resides in words. Iam sure that I complained asbitterly as any <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong>High <strong>School</strong> student at thememorization of Whitmanand Dante and wonderedloudly about the usefulness ofreading literature with such afine-toothed comb. Now, tenyears later and in the midstof my first year of law school,those texts, and the skills ofclose reading learned in highschool, come back to me whenI most need them.As a first-year law student,I read more deeply than Iever thought possible. Thewords that form the rulesthat govern our lives areboth incredibly simple, andfraught with meaning. Themost empowering discovery Ihave made is that our laws aresimply logic and standards,and understanding them is assimple, if time-consuming,as studying Songof Myself. Ithink of thatWhitman poemsometimeswhen I amconfrontedwith the mostubiquitousphrase in afirst-year lawcurriculum:“the reasonableperson.” This legal fictiongoverns nearly every aspect ofour lives. Generally, a personwho has acted reasonablywill not be expected to bearthe cost of an accident. Areasonable belief that yourlife is in danger will allow youto plead self-defense in acriminal case. A person whohas reasonably relied upona promise will be awardeddamages in a contract dispute.The phrase holds no magic.All that we as jurors, lawyers orjudges must do is determinehow favorably or unfavorablya person’s actions compareto those of “the reasonableperson.” It is the first questionwe ask ourselves when wejudge any situation. Did thisperson behave as we have aright to expect of him?Thankfully, our legal systemprovides that at the end ofevery legal dispute thereis a person, a judge, wholistens to all sides, considersthe behavior of eachperson and, based uponknowledge of the law andconsideration of the merits ofthe arguments presented,makes a judgment.Our standards areas flawed andimprecise asthe reasonablepeople whoapply them. Itwas a revelationto me thatjustice, whenread closely, isjust that simple.Of course there are exceptions.I have as much healthyskepticism and political angstas ever, but I am comfortedby the fact that every time Ire-read the precise languageof the law, I come up, not withthe loopholes and tricks thatare the stereotypical stock andI am comforted by the factthat every time I re-readthe precise language of thelaw, I come up, not withthe loopholes and tricks thatare the stereotypical stockand trade of my professionto-be,but with words.trade of my profession-to-be,but with words. When I readthem closely, the way I’ve beentaught, they simply say: Werequire from one another onlywhat we require from ourselves.That seems to me a good startto creating a just society. qKatusha Galitzinegraduatedfrom <strong>Green</strong><strong>Meadow</strong> in 1999.Following hergraduation fromEmerson Collegein 2004, Katusha worked for fouryears at PEN USA, a nonprofitwriters’ organization in LosAngeles, advocating for writersunjustly imprisoned around theworld. She is currently in her firstyear at Northeastern University<strong>School</strong> of Law.<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2010</strong> | 13

Four for the LawCriminal Justice:At Home and AbroadRose Rivera ’99Since the spring of 2009, I havehad two internships in criminaljustice. The first placed mein the office of the PublicDefender of Chicago, Illinois.The second took me to theInternational Criminal Court inThe Hague, Netherlands.As an intern with the CookCounty Public Defender ofChicago in the spring of2009, I discovered someof the challenges facingdefense counsel in the urbancourtroom. I witnessed theprosecution of a homelessman for stealing several sticksof deodorant and of a drugaddict for the theft of packetsof Kool Aid. The majorityof my clients were youngAfrican-American men whomthe state had undoubtedlyfailed. They were individualswho had grown up in poverty,received a sub-standardeducation and lacked asupportive family settingsince birth. A great numberwere mentally ill. What rolehad justice played in theirlives up until now?On many occasions, I sat withdefendants as they struggledover the choice of forcing thestate to prove its case, andtherefore risking a sentenceof twenty, forty or more yearsAround 90% of criminalcases in the United Statesend in guilty pleas asopposed to trials.Thisprocedural injustice hasbecome necessary in thename of efficiency.in prison, or agreeing toplead guilty in exchange for arelatively minor sentence, oftwo, four or perhaps six years. 1Around 90% of criminal casesin the United States end inguilty pleas, as opposed totrials. 2 This procedural injusticehas become necessary in thename of efficiency becauseof the sheer quantity ofindividuals the criminal justicesystem sweeps through itsdoors on a daily basis.In October 2009, I begana six-month internship atthe International CriminalCourt (ICC) with the DefenseSupport Section in The Hague,Netherlands. The work herediffers greatly from that of theCook County Public Defender’sOffice. The ICC does not sufferfrom the overwhelming numberof defendants and the resultingneed for efficiency that theCook County Courthousedoes. Here, the ICC Prosecutoris pursuing only four situations:Uganda, the DemocraticRepublic of the Congo, theCentral African Republic andDarfur, Sudan.The most recent newsout of the ICC is that thePre-Trial Chamber in theDarfur situation refused theProsecutor’s request to confirmcharges against Bahar IdrissAbu Garda, a military leaderaccused of killing AfricanUnion Peacekeepers, forwant of evidence. While thisdecision came as a blow tothe Prosecutor, the event alsomarks a triumph for proceduraljustice. In other words, the PretrialChamber has shown thatit is not a rubber stamp for theProsecutor, and the Prosecutormust not take lightly his duty14 | <strong>Alumni</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>

Four for the Lawto prove, with evidence ofcriminal activity, that chargesare warranted.Despite this triumph ofprocedural justice, the ICCis not immune to criticism.The ICC is limited greatly inits quest for justice by thepolitical reality that surroundsit. For example, all four ofthe situations currently beingprosecuted come from Africa.Africa is certainly not the onlyplace in the world where warcrimes are being committedand ought to be prosecuted.Therefore, the ICC’s limitedprosecutions at this timerepresent an imbalance in theICC’s response to the world’sconflicts. 3While the crime of militaryaggression is recognized as animportant crime in internationallaw and is included in the RomeStatute (the Statute of theICC), to date, the ICC has notbeen empowered to prosecutemilitary leaders for the crimeof aggression. When theRome Statute was negotiated,individual state parties couldnot come to agreement on sobasic a matter as a definitionfor the crime of aggression,nor could they agree on whatconditions would permit theICC to exercise jurisdictionover such a crime. Everystate believes that the wars itconducts are just. Coming toan international agreementover the circumstances underwhich military aggression isillegal has proved elusive. Thefailure of the Rome Statute todefine the crime of aggressionis just one example of thedifficult political reality withinwhich the ICC operates andthe challenges it must face indefining justice.The ICC is a young institutionand will have time to growand meet these challenges byexpanding its prosecutions tobe more representative of theworld’s conflicts and, maybe,by one day prosecuting militaryaggression. Even so, we willhave to ask the questions,whose military aggression arewe prosecuting, and why?The question of justice andfairness necessarily involves anexamination of the questions;who made the law, who willbe prosecuted and why thesecrimes and not others?There is a misconception thatjustice is perfect, that it canbalance good and bad andthat it makes all things right.The reality is that the questionof what is just is a difficultone to resolve. Our complexsystem of laws synthesizes amyriad of objectives, somewholly unrelated to justice.Within this framework, itis often easy to forget thatone side of the scale mustnecessarily go down in orderfor the other side to balanceup. Whether the scales ofjustice are equally balanceddepends entirely on one’sperspective. These are thelessons I have learned whileworking in the criminal justicesystem for the last year. qRose Riveragraduatedfrom <strong>Green</strong><strong>Meadow</strong> in1999 andfrom EarlhamCollege in 2003. She spent 2003-04 in Florence, Arizona, workingas a paralegal with the FlorenceImmigrant and Refugee RightsProject, a non-profit that provideslegal services to detained,indigent immigrants. From2004-06, she worked in Chicagoas a Bilingual Crisis Counselorat Trilogy, Inc, a communitymental health center. In 2006-09,she attended DePaul UniversityCollege of Law and graduatedcum laude with a certificate inInternational & ComparativeLaw. Rose is currently workingas a paid intern with theDefense Support Section of theInternational Criminal Court. Atthe end of her internship, sheplans to return home to Chicago.1. While the US Supreme Court has held that a defendant may not receive a higher sentence for exercising hisconstitutional right to a jury, there is little doubt that defendants in many courtrooms of the Cook County CriminalCourthouse receive significantly lighter sentences by agreeing to plead guilty. Ne i l P. Co h e n , e t a l., CriminalPro c e d u re: Th e Po s t -In v e s t i g a t i v e Pr o c e s s , Ca s e s, a n d Ma t e r i a l s 360 (3rd ed. 2008). The Supreme Court justified suchoutcomes in Brady v. United States, where it held that those who plead guilty may receive lighter sentences thanthose who do not accept responsibility for their actions and instead expend government resources in the form of atrial. 397 U.S. 742 (1979).2. Na n c y Am o u r y Co m b s , Gu i l t y Pl e a s in In t e r n a t i on a l Criminal La w: Co n s t r u c t in g a Re s t o r a t i v e Ju s t ic e Approach 4 (2007).3. Many excuse the situation, stating that of the four cases being prosecuted, three were self-referred to the ICC bythe countries themselves and the other, Sudan, was referred to the ICC by the UN Security Council As a world court,the ICC has the responsibility to appear impartial as regards the prosecutions it pursues, and as such, bears theresponsibility to correct this situation in the future.<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2010</strong> | 15

On the StreetA Good and Fair CopRamona Ruud ’91Each time a person stands upfor an ideal, or acts to improvethe lot of others, or strikesout against injustice, he sendsforth a tiny ripple of hope,and crossing each other froma million different centers ofenergy and daring, these ripplesbuild a current that can sweepdown the mightiest walls ofoppression and resistance.–Robert Francis KennedyGrowing up in <strong>Spring</strong>Valley, I had noperception of lawenforcement or the broadercriminal justice system.The secluded world ofThreefold was immunefrom the necessity of a lawenforcement presence. Itwas not until I was fifteenyears old that I had anyinteraction with members ofthe field of criminal justice.I was instantly opposedto the system, feeling myfreedoms and rights weresuppressed. This made merebel against the pressure toconform to what I perceivedas their rules. At the sametime, I was beginning todevelop a sense of the worldas a whole and the idea thatthere is a basic human needfor order. I started doing myown research into differenttypes of political structuresand philosophies and beganto understand that laws andtheir enforcement were vitalfor a just society.When I arrived at the Universityof Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Istarted studying toward adegree in political science withan emphasis in pre-law. I wasintroduced to a professor ofcriminal justice and becameone of her research assistantsin a study of police use ofdeadly force. Throughoutthe study, my responsibilitiesrequired me to interviewmany police officers. It wasthe first time in my life that Irealized that police officerswere people who took the jobto actually help people. It wasout of these interactions that Ideveloped a deep respect forthe profession and the peoplewho chose it.In 1997, I was in my final yearof college and looking tomy future. I really wanted togo to law school. However,I had three young childrenand knew I needed a jobthat would support them.During the research project,I developed a friendship withone of the police officers, andhe suggested I take the testto become a police officer.I agreed, thinking that I hadnothing to lose by trying.When I went to take thewritten test, I was amazed bythe experience. People hadcome from all over the countryfor a chance to become aMilwaukee police officer.There was a man in a tuxedowho came to take the test—even though he was gettingmarried within minutes of itscompletion. I suddenly reallywanted to become a policeofficer, but realized I camefrom a completely differentbackground than the rest ofthe people there, who weretelling stories of wanting to becops since they were children.In 1998, after going througha rigorous process, I washired by the MilwaukeePolice Department andstarted training at the policeacademy. I loved my lawclasses and hated my rulesand regulation classes. I wrotethe back of tickets like collegeessays and was told that Platoand Thomas Jefferson hadto be on my personal time,not part of my career. I wastold repeatedly that I wasthe only person making thejob harder for myself than itneeded to be. On the nightof my graduation, I was pulledaside by the command staffand told that I would eithermake one of the best cops inthe department or the worst.It was up to me.I hit the streets of Milwaukeewith a desire to do good andbe fair. I quickly learned thatI had chosen a thankless jobwith brutal hours and terrifyingmoments. Instead of saving theworld, I went from assignmentto assignment dealing withpeople who were desperateand in horrible situations andwho, for whatever reason, wereunable to help themselves.So they reached out and gotus. I tried always to be fair andunderstanding, to providethe service that I would wantone of my family members toreceive. I lived by the motto16 | <strong>Alumni</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>

WashingtonWhat we think of as “normal”never actually existed—it wasall fake, inflated by a creditbubble of historic proportions.Equality of opportunity—theoriginal promise of theAmerican Dream—is nolonger a reality for the vastmajority of Americans. Theworking class can no longergrasp the bottom rungs of theladder of upward mobility. Arecent study by the London<strong>School</strong> of Economics ofeight industrialized Westernnations found that the US hadthe lowest intergenerationalincome mobility and concludedthat “the idea of the US as ‘aland of opportunity’ … clearlyseems misplaced.” 8It’s far from clear that ourpolitical system is capableof solving these problems.Entrenched interests havethe means (and the incentive)to ensure the playing fieldremains tilted in their favor.For example, I spend moretime meeting with financialindustry lobbyists than doinganything else. As Matt Bainoted recently in the New YorkTimes <strong>Magazine</strong>: “anyone whospends any significant timein the political world knowsthat corporate money, raisedand leveraged by lobbyists, isperverting any notion ofgood policymaking, as surelyas ice dancing perverts theidea of sport.” 9But it’s not clear that limitingtheir voice is the right answer.Doesn’t the responsibility fallon the shoulders of our leadersto do what we elected themto do, look after the publicinterest? Our leaders need tofind the courage to do just that:lead. That means refusing tocave in to special interests. Italso means making unpopularchoices and persuading thepublic to fall in line behindthem, instead of slavishlyobeying the latest opinion poll.In the age of 24-hour cablenews, hyper-partisanshipand the perpetual campaign,political theater appears tohave replaced serious debate,even in the world’s mostdeliberative body. Here in thecapital, all the talk is aboutprocess and politics—aboutwhat reforms, if any, arepolitically feasible. Thereis precious little discussionabout what kind of reforms weactually need. As Frank Richput it in a recent New YorkTimes column, the debate“is again about the arcanaof process and bureaucraticmachinery, not substance.” 10That’s not entirely true, ofcourse. There are seriouspeople here in Washington,and many of our politicalleaders are dedicatedpublic servants. But thegamesmanship has reached alevel where the tail does, mostdays, appear to wag the dog.My job is not only to navigatethe “arcana of process” and“bureaucratic machinery,” butalso to try to make sure thatafter all the political theateris over, the final product isone that will help the countryovercome the challengesfacing it. Wish me luck … qAfter graduatingfrom NYU witha BA in politicsin 2000, JonahCrane workedconstruction for a year beforetaking a job as a paralegal at asmall law firm. From there, hewent on to attend NYU <strong>School</strong>of Law, graduating in 2005.After graduation, he workedas a mergers and acquisitionsattorney for Milbank, Tweed,Hadley & McCloy in NYC for fouryears. He left that firm last Julyto take a position as a policyadvisor to NY Senator CharlesSchumer on banking, finance andeconomic policy issues.1. Don Peck, “How A New Jobless Era Will Transform America,” The Atlantic (March <strong>2010</strong>).2. The views expressed are mine alone and do not necessarily represent those of Senator Schumer.3. James Truslow Adams, Epic of America (1931).4. Henry R. Luce, “The American Century,” speech, 1941.5. See David Kamp, “The Way We Were: Rethinking the American Dream,” Vanity Fair (April 2009).6. Edward N. Wolff, Recent Trends in Household Wealth in the United States: Rising Debt and the Middle Class Squeeze,Working Paper No. 502, The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College and Department of Economics, NYU (June 2007).See also John Schmitt, Inequality as Policy: The United States Since 1979, Center for Economic and Policy Research(October 2009); and Lawrence Mischel, Jared Bernstein and Heidi Shierholz, The State of Working America 2008-2009,Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press, 2008 (available at http://stateofworkingamerica.org/).7. See Wolff.8. http://cep.lse.ac.uk/about/news/IntergenerationalMobility.pdf9. http://www.nytimes.com/<strong>2010</strong>/03/07/magazine/07fob-wwln-t.html10. http://www.nytimes.com/<strong>2010</strong>/03/07/opinion/07rich.html<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2010</strong> | 21

Justice for Conflict and Post-Conflict StatesJusticeTransitionalLejla Zvizdic ‘97Both the idea andthe ideal of justicehave mobilizedme from an earlyage. My desire tounderstand what justice trulymeans and how to be a part ofits realization has shaped bothmy life and my professionalpath. My understanding of thedifferent elements comprisingjustice has evolved over time.Through school, particularlylaw school in the UnitedStates, I learned about thestandards and proceduresguaranteeing justice in theAmerican legal system. Mysubsequent work experience,however, has been in the fieldof international law, in anarea commonly referred to astransitional justice. Transitionaljustice is the process of reestablishingthe rule of law inpost-conflict societies wherea majority of the populationhas suffered some form ofinjustice. In such societies, theexpectations and ambitionsfor “getting justice” haveenormous urgency.I was a teenager when the warin Bosnia broke out in April1992. The frenzy and panicof war gave rise to reports ofunimaginable horrors takingplace throughout Bosnia.Inevitably, war imposed adifferent reality upon our lives.While the war came as a shock,the biggest injustice that Iexperienced as a thirteenyear-oldwas that my sociallife was interrupted. I refusedto resign myself to war anddecided then, although I hadno realistic way of achieving itat the time, that I would workto bring justice to Bosnia.Now, looking back, it is clearto me that I couldn’t evenbegin to understand the fulldimensions of the war nor thecomplexities of bringing justiceto Bosnia. It was only afterthe war ended that I beganto realize its full impact andconsequences. Over time, Ibecame increasingly interestedin pursuing justice, not only inBosnia, but in general.I should note from the startthat the perspective fromwhich I think about justice isthat of a post-conflict situation.My opinions on this issueare largely influenced by twofactors: my own experience ofliving through the Bosnian warand my professional careerworking with institutionsthat hope to deliver justiceto post-conflict societies. Inpost-conflict societies, someof the basic premises forequity and justice are oftenmissing. Compounding theproblem are the convergingstrategies of local, nationaland international intereststhat tend to postpone the reestablishmentof a just andself-sufficient society.Justice is a concept treateddifferently by almost all theparties involved or affectedby it. I have arrived atthis opinion only recently,prompted by my current jobworking with the InternationalCommission on MissingPersons (ICMP) in Sarajevo.ICMP provides technicalassistance to governmentsby using DNA testing toidentify the mortal remainsof persons missing as a resultof war. It is a fascinatingprocess in which the cuttingedge of science assistsgovernments to determinethe fate and whereabouts ofmissing persons. The resultsof the DNA-led identificationprocess can later be used inthe criminal prosecution ofindividuals responsible for thedisappearances of people andother related crimes.At ICMP, I have seen howmuch the issue of missingpersons, which accompaniesevery conflict, can impact thegeneral state of justice in asociety. The harm caused bythe disappearance of a personinvolves two violations—first,when the person is initiallyabducted and, later, when theidentification process by postwarauthorities is impededor inadequately pursued. It isabsolutely amazing how longthe search and identification ofmissing persons takes. In mostcountries, this issue is highlypoliticized and is consequentlynever addressed. Governments,for various reasons, are oftenuninterested in pursuing theidentification process. Yet theharm to families, communitiesand even states continuesuntil the missing persons(or their remains) are foundand identified. In the interim,human rights jurisprudencehas developed to permit thefamilies of missing persons toclaim reparations. Legally, thetwo violations I mentionedabove are regulated byinternational humanitarian22 | <strong>Alumni</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>

GJustice for Conflict and Post-Conflict Stateslaw and human rights law,and to a certain extentdictate the mode and theextent of the assistancethat ICMP can provideto governments in reestablishingthe rule of law.Before ICMP, I worked insuch classic legal settings asthe prosecutor’s office andthe courts, where the conceptof justice was encapsulatedin the criminal code and thecriminal procedure code.Discourse was limited tothe perpetrator and theprosecutor, who representsthe interests of the state orinternational community. Thecourt’s purpose is to assignaccountability for violationsof important principlesprotected by internationalcustomary law and generallydefined as being gravebreaches of the GenevaConventions, Crimesagainst Humanity, andGenocide. For a long time,this international criminallaw setting was a comfortzone for me. Internationallaw seemed comprehensiveenough to address thewar-time violations ofcustomary internationallaw, with the assumptionthat ensuing judgmentsprovided a sufficient basisfor the reinstatement of ajust society.I have learned sincethat justice consists of acombination of public andprivate interests. When thenorms characterizing justiceare translated into laws,however, the injured parties,whom the same laws seekto protect, are very oftenleft feeling unsatisfied. Fromthe societal perspective,there are certain objectivestandards that must bein place for a country orstate to be characterizedas just and for it to growand develop on a collectivelevel. However, individualunderstanding andexpectations of justice maybe completely different. Inpost-conflict settings, theinjured parties, referred toas victim groups (whosebasic rights have beenviolated), often feel that theviolations of their rights/interests committed duringwar continue in its aftermathbecause the post-warauthorities and institutionsare usually unable orunwilling to provide thenecessary protectionsand/or compensationsin accordance withinternational standardsof justice. While this isthe case to a certainTransitional justice is the processof re-establishing the rule of lawin post-conflict societies wherea majority of the population hassuffered some form of injustice.extent in all societies,this disparity betweenthe legal possibilities andpeople’s expectations isparticularly acute in postconflictsituations, where thedamage to society extendsbeyond what is measurable(loss of life, bodily injury,material and infrastructuredestruction, etc.), makingjustice quite difficult toimagine and even moredifficult to implement.It took me fourteen years toreturn to Bosnia, to Sarajevo.Assisted by geographicaldistance, the amenitiesof academic settings andjobs elsewhere, I skillfullypostponed my return. Foryears, I was comfortablewith the role of an outsiderand engaged in discussionsabout “achieving justice” inBosnia, or any other newlypeace-brokered successstory of the internationalcommunity, by reciting thelaw book arguments inthe context of the politicalsituation on the ground.After a while, this lost itsappeal.It was hard to come backto the place where mylong journey had begun.What started as a child’sdream, arising from theextraordinary conditionsimposed by war, haddeveloped into a careerpath where I exploredvarious standards andmodes of implementationof justice. Since myreturn to Sarajevo, I cansee that the process ofre-establishing justice isfar from complete. Theprocess is much morecomplex than I previouslythought. Being here hastaught me how much moredifficult it is to re-createsomething as compared toimproving it or building ona solid foundation. This isespecially true when thatsomething is justice, whichcovers so many aspectsof a society and requirescollective and individualinvolvement. So, justice hascome to mean just that—even though it is hardlyperfect anywhere, it is somuch easier to improve itthan to re-introduce theconcept after the basictenets of the society havebeen broken. Yet eventhis process can be avery positive experience.Bosnian society canemerge from its transitionaljustice process with clearlyarticulated legal standardsand practices that are bothstronger and better thananything that existed herebefore the war. qLejla Zvizdicwas bornand raisedin Sarajevo,Bosnia andHerzegovina. Inthe spring of 1995, assisted bythe Fellowship of Reconciliationand the Jerrahi Mosque, sheleft Bosnia to attend <strong>Green</strong><strong>Meadow</strong>, joining the Class of1997. She graduated fromthe <strong>School</strong> of Foreign Serviceat Georgetown University in2001 with a degree in foreignrelations and international law.That same year, Lejla started lawschool at Creighton Universityin Omaha, Nebraska, graduatingin 2006. After her secondyear in law school, she tooka two-year leave of absenceto pursue a legal clerkship atthe Office of the Prosecutor atICTY in The Hague and workedon the establishment of theWar Crimes Department atthe Bosnian State Prosecutor’sOffice. In the summer of 2006,Lejla sat for the bar exam inthe State of New York and inDecember 2006, started workas a Legal Officer at the UNMission to Kosovo, workingfor international judges with amandate to handle war crimesand ethnically and politicallyrelated crimes in Kosovo.Lejla returned to Sarajevoin May 2009 to work for theInternational Commission onMissing Persons.<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2010</strong> | 23

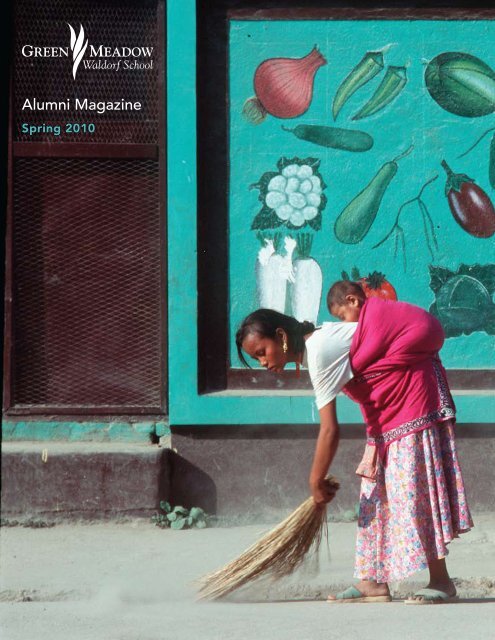

Justice for Conflict and Post-Conflict StatesWar in TranslationSurvivor of Violence by Ann HunkinsAnn Hunkins ’84Itraveled to Nepal for acollege semester in 1986and learned Nepali onan immersion program,living with a homestayfamily who spoke very littleEnglish. I fell in love with thecountry, and more specifically,with a young Nepali manwhose English about matchedmy Nepali. We were marriedfor five years, during whichtime I transferred to ColumbiaUniversity, where I studiedNepali intensively. In 1991,I began translating Nepalishort stories on a Fulbrightgrant. Over the next fifteenyears, I traveled back andforth to Nepal, developingrelationships with writersthere, working on a long-termproject photographing andinterviewing Nepali authorsabout their lives, while workingas a photojournalist in the US.Nepal has a long and troubledhistory of political upheaval.Long before my arrival, themonarchy had strenuouslyopposed Nepal’s multi-partydemocratic development.When a 1990 movement fordemocracy ended in a bloodbath,King Birendra agreedto a return of the multi-partysystem, resulting in Nepal’sfirst democratic electionsin thirty years. The king,however, retained controlof the armed forces. A smallparty called the Maoistssprang up. Frustrated withthe corrupt politics of thefledgling democracy, theytook to the jungles with gunsin 1996. In June 2001, the kingand most of the royal familywere killed in a massacre thathas never been satisfactorilyexplained, leaving Gyanendra,the king’s much-hatedyounger brother, on thethrone. It was Gyanendra whofirst deployed Royal NepalArmy soldiers, rather thanpolice, against the Maoists,after a rebel attack on an armybase. In 2005, King Gyanendrasummarily dismissed Nepal’s24 | <strong>Alumni</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>

GJustice for Conflict and Post-Conflict Statesdemocratic government. Theconflict escalated into a fullscalewar.In late 2005, I was inKathmandu giving interviewsabout a Nepali novel I’d justtranslated, editing films, proofreadingEnglish manuscriptsand translating poetry. Whilethe news was full of reports ofcountrywide unrest and almostdaily clashes between theRoyal Army and rebel forces,it was still possible to live inKathmandu and feel the warwas remote. I wanted to beinvolved, to make a positivecontribution. Two friendstold me that the UN Officeof the High Commissioneron Human Rights (OHCHR)was looking for internationaltranslators. I called and washired immediately, flying off toJanakpur on my first missionjust after the New Year, 2006.Before the huge, grinding UNbureaucracy could even catchup to my paperwork, I wasdescending into the freezingfog of southern Nepal, wearinga blue UN vest and cap, a twowayradio in hand, but withoutany briefing about what myjob entailed. I was far fromprepared for what lay ahead.During the three months Iserved as translator, I traveledcentral and southern Nepalwith UN teams typically madeup of two or three HumanRights Officers, a SecurityOfficer, a driver and a nationalor international interpreter.One of the Human RightsOfficers served as teamleader. The HROs were highlyexperienced, having served inBosnia, Rwanda, the Congoand other war-torn countries.No training was requiredfor translators beyond acompetent knowledge ofthe language. Internationaltranslators were preferred forcertain missions because oftheir neutrality.My first trip into the fieldlasted nine fifteen-hour days.On the third day, we visited aprison where we interviewedfourteen prisoners in a row,half of whom didn’t speakNepali. The TV was blastinga Hindi film, and an old manburst into tears. Many morewaited to talk with us, but wehad to move on to the nextjail, village and battlefield.Nearly every interview at thatfirst jail (and later jails) wentlike this: Do you know whyyou’re here? No. What’s thecharge against you? I don’tknow. Have you been givenany documents related toyour case? No. Have you hadaccess to a lawyer? No. Haveyou been presented beforea judge? No. How long haveyou been here? Months. Wereyou tortured? Yes. When weinformed the jailer he washolding people illegally, heargued that they were Maoistterrorists, detained underNepal’s terrorist act. He saidhe had their papers in safekeeping,that the prisonerswere lying about torture andthat they had had a courthearing. In some places,we contacted lawyers andasked them to visit individualprisoners, on a pro-bono basis,but we often heard later thatjailers denied them entry.Torture was routinethroughout the country.OHCHR conducted numerousinterviews of torture victimsin the field and in our offices.We spoke with men who, fora year, had lain blindfoldedon a floor in a Royal NepalArmy barracks, right in themiddle of Kathmandu, andwere dragged out periodicallyfor beatings and shocks.Translated interviews suchas these were gathered andincluded in a report to the UNGeneral Assembly regardingviolations of the GenevaConvention.Even when a Nepali legalprocess gets underway inNepal, the police and thecourts are by no means inagreement. The judicialprocess often goes like this:Nearly every interview at that first jail...went like this...What’s the charge againstyou? I don’t know... Have you had accessto a lawyer? No....Were you tortured? Yes.A man is brought to court,handcuffed, flanked by police.His attorney argues beforethe judges that the man hasbeen illegally detained andthat there was no proof he wasinvolved in any kind of terroristactivities. The prosecutionresponds, saying they caughtthe man carrying a radio, tworounds of ammunition and afolded pair of combat dressshorts. They cannot producethese articles. The defensecounters that the man was onan ordinary trip to town to buyoil and salt for his family andthat he has never been knownto be involved in Maoistactivities. The judges retire<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2010</strong> | 25

Justice for Conflict and Post-Conflict Statesfor thirty seconds, return andgive their decision: insufficientproof, illegal detention. Theyhurry to their chambers,change into civilian dressand rush out the courthousedoor, heading for home, asif not wanting to know whathappens next. It is five p.m.Inside, the man is takento a room to sign papers,still handcuffed. The youngeloquent lawyer says to thepoliceman: “Take off hishandcuffs, he’s been releasedby the court.” The policemansighs, rolls his eyes and uncuffsone hand, leaving the othercuff dangling. “Take off theother,” says the lawyer. Thepoliceman rolls his eyes again,shrugs and takes off the otherhandcuff. He doesn’t leave theman’s side as they descend thecourthouse steps and head forthe street. At the compoundgate, the man’s family iswaiting to see him for the firsttime in a year. His wife’s facelights up at the sight of him.At that moment, a police vanrounds the corner, pulls up atthe gate, cutting off the family.The policeman handcuffsthe man, again, and bundleshim into the police van. He isdriven back to jail.I translate for police, armygenerals, rebel commanders,journalists, lawyers, victimsand their families. We checkinto expensive hotels and ridearound in a huge van withVHF rabbit ears. We have toradio our location in codeonce an hour to headquarters.Four-wheel drive vehicles area necessity on mountain roadsin bad repair, as lumberingox carts and barreling busesappear out of the fog. It iswinter, and bridges are down;people are dying of the cold.My radio and ID card arenow a part of my body. Wepass through hundreds ofcheckpoints, examine shallowgraves, burnt-out houses,monitor demonstrations,try to avoid tear gas andbrickbats.I translate for a woman whodescribes her husband tryingto hold onto the pillar of thehouse as he was dragged awayby rebels, a hundred silentvillagers looking on, then thesound of two shots and findinghis body floating in a pond. Wejust have time to hear her out—we have to go. The women arethe ones left to hold togetherwhat remains of their families.It becomes obvious how manyWhat to say to bereaved parentsof a four-year-old boy, victim of ahelicopter bombing “mistake”?people are using the war as anexcuse to get back at personalenemies or to further their ownpolitical or financial aims.Teenagers stand guard withsubmachine guns as I sit ina farmhouse translating forMaoist commanders who usehighly complex vocabulary,creating new words I haven’theard of, to avoid usingEnglish. They want us toknow they always follow theGeneva Convention, thatany allegations of forcedconscription of child soldiersor summary executions bytheir cadres are totally falsified.What to say to bereavedparents of a four-year-old boy,victim of a helicopter bombing“mistake”? Yet even there, inthe two-room house whereseventeen people live, aswe examine the mortar hole,shrapnel in the bloodstainedbedclothes, in the midst ofgrief and the smell of heavydrinking, a woman holds abeautiful newborn baby, and atiny chick, dressed in a handsewnsweater, runs between talllegs, making everyone laugh.Yes, this translation work iswhat I wanted to do, andno, it’s not. Often I feelthat we’re here to gatherinformation about a tragedy,but we are powerless to giveany immediate assistance.Sometimes we do, but notusually. It’s not in our mandate.All day, I say what I am toldto say, go where I am toldto go, sleep where I am toldto sleep. That’s the reality ofbeing a translator. I’m alwaysspeaking someone else’swords, not my own. And, then,everything is confidential. I’mnot allowed to tell anyonewhat happened or even wherewe’ve been or where we’regoing. I’m the one who speaksthe language, so people makean emotional connectionwith me. Then we leave, andI never see them again, neverknow what happened in theirstory. Someone called me “aninvisible window.”After three months, I realizethat in the process of tryingto save the world, or onesmall piece of it, I am losingmyself. Everyone I work withhas coping mechanisms:chain-smoking, doing magic26 | <strong>Alumni</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>

GJustice for Conflict and Post-Conflict StatesMacchendranath Crowd by Ann Hunkinstricks, sleeping only four hoursa night, raging in anger. Iflew home to the US in April2006, after my health brokedown, literally on the eve ofrevolution. When I got home,I had no place to live, and twoclose friends were seriouslyill. I felt part of my brain hadbeen sheared away. I spentmy time watching the secondNepali revolution I was missingon the internet, and drinking.Democracy was reinstated,the Maoists put down theirarms and King Gyanendra waseventually dethroned. OHCHRemailed me three times overthe next few months, hopingI would return and work forthem again.After a difficult year, the deathof one friend and the recoveryof the other, I quit drinking,got a job at a bookstore,received an NEA grant totranslate another Nepali noveland started therapy for posttraumaticstress disorder. Ijoined a goat co-op, learnedto milk and make cheeses,kefir and yoghurt. I joineda community garden andgrew corn, beans, squashand herbs. I took a class onherbal healing. I tried to tellthe whole story to everyoneI knew, over and over again.Slowly, I’ve been recoveringmy health, though the eventsnever leave me.I haven’t returned to Nepalyet. I know OHCHR playeda significant part in endingthe war. It’s true that not asingle human rights violatorthat we investigated has beenbrought to trial in Nepal andthe country continues to hoveron the edge of dissolution ofits hard-won peace process.Still, I’m glad I could helppeople tell their stories. Thereare people whose lives weaffected positively, simply bylistening to them and bearingwitness to the injustice andpain they suffered. qAnn Hunkins (left, in the field with the UN team andvillagers) graduated from Barnard College in 1989. Apoet and photographer, she has lived and worked inboth the United States and Nepal. Her photographs ofNepali authors were presented at a 2003 exhibition inKathmandu. Ann received a National Endowment forthe Arts Translation Grant in 2008. Her translations havehelped bring the work of Nepali authors to internationalattention. She lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico.<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2010</strong> | 27

What Would Steiner Say?Choosing toChampion OthersJane Wulsin, Class Teacher of the Classes of ’91, ’99, ’07 and ’16As a Class Teacher, Iam very interestedin knowing whatdraws a <strong>Waldorf</strong>student to become a lawyeror to work in the enforcementof the law. There are manypossibilities: having a love forjustice, truth and fairness, forprotecting and championingthe rights of others, forclarifying and defining, forresearch and discovery, forthoughts and opinionsin order to develop theirown ability to make clearjudgments. From what I knowof these individuals, theyparticularly love intellectualstimulation and challenge, aproblem or mystery to solve,a new interpretation or use onwhich to expound. They enjoyengaging others verbally, andthey are excellent writers,historians and poets. Theywill make a difference. Theymust continue to strivefor a genuine knowledgeand understanding of life,of relationships and ofevents of our time. How is itpossible to bring a spiritualunderstanding to earthlysituations and events? How isit possible to bring spiritualimpulses into our earthly life?That is the question and thetask for all of us.They are striving to know themselves, forrepresentation and justice can only comefrom those who have developed their ownindependent capacity of thinking and judgment.creating new laws and policies,for bringing order; havingan interest in an individual’squestions and problems;having an interest in socialquestions and social problems;in short, having a love forhumanity and a passion formaking the world a betterplace in which to live.A good lawyer or law enforceris an excellent listener, for heor she knows that it is open,unprejudiced listening thatleads to understanding. The<strong>Green</strong> <strong>Meadow</strong> alumni whohave contributed to this issuehave learned how to quiettheir own thoughts, to listento and beyond the wordsof another, to be inwardlytolerant of other people’sare champions of others,particularly underdogs; theyare protectors and guardiansof rights. They carry withinthemselves a strong impulseto help their fellow men andwomen.People create society. Peoplechange the world. Everynew group of people bringsnew impulses and uniquecapacities into the world. Itis fortunate, indeed, that thisgroup of capable, grounded,strong-willed individualsis involved in this essentiallegal/political sphere. RudolfSteiner said that “withevery new generation, anew spiritual life will everincreasinglyappear on earth.”This group of individualsIdealism and a determinationthat human life andrelationships can be betterthan they are have led theseformer <strong>Waldorf</strong> studentsinto the field of law. They arepeople who have a genuineinterest in their fellow menand women, an interest whichenables them to take onothers’ situations, to walk intheir shoes. They are strivingto know themselves, forrepresentation and justicecan only come from thosewho have developed theirown independent capacity ofthinking and judgment. Theyare warriors because theystand up against adversityin winning for others whatthey themselves know tobe right and best. They aredeeply moral individualswho embrace hard work andwill do all that they can tobring positive impulses andpractices into the world. Theseare the <strong>Waldorf</strong> alumni I knowwho have taken up the bannerof justice. I salute all that theyare doing and will do! q28 | <strong>Alumni</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>

To truly know the world,look deeply within yourown being; to trulyknow yourself, take realinterest in the world.–Rudolf SteinerGMWS eighth graders walkingBoston’s Freedom Trail, fall 2009.Photo © Natt McFee <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2010</strong> | 3

307 Hungry Hollow RoadChestnut Ridge, NY 10977845.356.2514www.gmws.orgNON PROFIT ORGUS PostagePAIDPermit # 4HANOVER, PAThreefold Educational Foundation & <strong>School</strong>FORWARDING SERVICE REQUESTED4 | <strong>Alumni</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>