Kelly Richardson - Forest Park - Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery

Kelly Richardson - Forest Park - Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery

Kelly Richardson - Forest Park - Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

CONTENTSPeril, Glee John Massier6Perpetual Anticipation:Crystal Mowry in conversationwith <strong>Kelly</strong> <strong>Richardson</strong>20List of works29About the contributors30artist’s BIOGRAPHY32

CAMP, 2001

Peril, Glee By John MassierDecades ago, Andy Warhol was interviewed about some of his extremely lengthy films and how audiencesmight consider them. He responded with typical aplomb: Well, look at them, then walk away.Then, come back and look at them again later. Look at them like you look at paintings. It was a remark thatdiscarded any narrative imperative and reiterated film’s image-based actuality. Is Warhol’s Empire aboutanything? Ambition? Imperialism? Sure, why not. Yet, fixated on a single image, Empire also articulates, ingorgeous black and white, an acute awareness of the present moment. There is a dogged insistence thatyou consider this moment. And all that implies. Beauty. Uncertainty. Expectation. Possibility.In one of <strong>Kelly</strong> <strong>Richardson</strong>’s earliest videos, 2001’s Camp, a fixed image of the moon at night issubtly affected by the rising vapors of a campfire and accompanied by the sound of popcorn popping. It islow-tech and simplistic and some viewers might have dismissed it as an unfulfilled joke with no punchline.But Camp exemplifies qualities of much of the video work that <strong>Richardson</strong> would subsequently produce.The cheapest of cheap tricks, it contains a specific effect applied to a single, persistent image. The addeddetail of popping popcorn undercuts the solemnity with a touch of comic absurdity, while that absurdityitself deepens the moment and makes more resonant its underlying humanity. There’s a lot going on whenyou’re looking at the moon.These elements arise again and again in <strong>Richardson</strong>’s videos. Whatever action there is, takes place asa localized event within the image, amplifying the tension within an otherwise relatively still image. A carstopped at a stopsign in the middle of nowhere, in front of a landscape, appears just as described, with the6

7Left: A car stopped at a stopsign in the middle of nowhere, in front of a landscape, 2001Right: howthedevil, 2002

added detail of a clouded sky scrolling by—the initial absurdity of the image is elongated by the visualcue of time, as depicted in a certain action. In some real sense, Time often functions as the protagonistof <strong>Richardson</strong>’s videos—within the scene depicted and within the viewer viewing.There are no other protagonists. Even within scenes where one might expect a human figure, noneare evident. Instead, <strong>Richardson</strong> is enfolding the viewer into successive imaginary spaces within whichthe essential ingredients are simultaneity of action and sensation. Action—even when limited—repeatsforever. Sensation—borne of repeated action and a seductive, engrossing image—blossoms to fill andexpand the moment. There is no single endpoint to this heady blend of elements—<strong>Richardson</strong>’s worksevoke the complex and contradictory sensation of life: anxious, hilarious, ominous, rapturous.howthedevil, in which a quiet scene in the woods is unhinged by a lone, epileptic bush, is bothdisquieting and funny. It has the aura of a revelatory moment, but a jittery rather than a burning bushsidesteps any onerous biblical connotations, minimizing the mythic and emphasizing the pathetic. But in<strong>Richardson</strong>’s work, pathos and absurdity are the keys to the kingdom because if one perceives peril in a<strong>Richardson</strong> video—and a jittery bush has an edge of peril about it, as does a car stopped in the middleof the desert—one must also recognize there is no small portion of glee sharing the image.In one of the few videos where <strong>Richardson</strong> utilizes a moving image, Ferman Drive, the repetitivebanality of tracking across a row of suburban homes begins to feel much like a still image. Therhythmic sameness rolls by for quite a while before the punchline hits the viewer and its impact is allthe more powerful because of the patience <strong>Richardson</strong> employs before delivering it. With a setting sofamiliar, real, and banal, Ferman Drive typifies <strong>Richardson</strong>’s method of proposing the implausible as plausible.It works because the ordinary is so carefully wrought. <strong>Richardson</strong> is not depending upon subtlety.8

9FERMAN DRIVE, 2005

Her gestures are overt and obvious, which makes it more critical that they be convincing gestures in andof themselves, blatant and beautiful lies that you must believe before they reveal any truth.A key element to these convincing realities is the perpetual use of ambient, understated soundtracks.<strong>Richardson</strong>’s sound choices do not heighten reality in the startling manner of her exaggeratedvisual motifs. If anything, the persistently ordinary character of her soundtracks are a subtle but effectivetool for grounding what are often preposterous visuals. Like a minor key, this subtlety slides byalmost unnoticed but enables us to find the incredible that much more authentic.The hidden layer in <strong>Richardson</strong>’s work is that her videos since Camp have involved an increasinglyarduous process. Warhol’s painting allusion is not merely relevant to an image-based comparisonbetween media. To arrive at a satisfaction with the precision of illusion—not to mention auditory cues—she is pursuing, <strong>Richardson</strong> still invests a painter’s time and process to her work. Initial photographyby the artist is augmented through numerous post-production elements, including color saturation, themanipulation of stock images purchased from film suppliers, hand-masking and repeating images, andfinal rendering of the finished work, which can easily take several weeks or even months.Her more recent videos increasingly reflect this buffing of production values, but the centralpremise of a perilous glee remains constant. In contrast to many visual artists who have appropriatedthe deep reservoirs of cinema history for their work, often to compelling effect, <strong>Richardson</strong> creates herown imagery by adopting cinematic tropes, particularly its potential for startling moments of acuity,including her increasingly adept use of deep, rich colors and her transition to a panoramic aspect ratio.If we are still talking about an expansive sense of presentness and possibility, these technical flourishesexpand the moment ever more fully.10

11Exiles of the Shattered Star, 2006

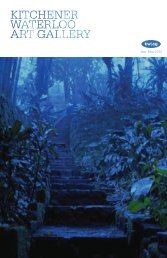

In Exiles of the Shattered Star (a heartbreaking title, if ever there was one), blobs of fire cascadeendlessly from the beautiful twilight sky. It’s a work both deeply ominous and weirdly soothing andit is in this contradictory space that <strong>Richardson</strong> is situates the viewer, locked and loaded in the Now.<strong>Richardson</strong> is not remarking on the disintegration of our livable environment or foretelling apocalypse(the work loops, so there is no disastrous dénouement), but these allusions are essential to feeding theambience emanating from the work. Yes, the sky is falling. And ain’t it grand?<strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Park</strong>, a new two-channel video, operates as a visual companion to Exiles. A wide stretch ofweeded land, the site of a pending housing development, is crowned by the burgeoning twilight sky anddotted with a delicate array of streetlights hovering over the scene. With the flickering lights visuallymimicking the soundtrack of crickets, <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Park</strong> emits the same hypnotic allure as Exiles. The sceneryis more sedate but there is the same sense of dark foreboding. And it is similarly irresistible, as thoughwe are being wrapped in something so mysterious we might call it anxious euphoria.Can you extract glee—however unspecific and inarticulate—from peril and unease, and what doesit mean to do that? In <strong>Richardson</strong>’s work, it becomes a matter of very specific faith—not in creed orscreed, but in possibility. When your universe consists of a series of interminably extended moments,there is always ample room for possibility, no matter the circumstance. In Wagons Roll, a car hangs inmid-air against a range of mountains and blue cloud-dotted sky, a plume of dust shooting from its rear.The average pop-saturated viewer will immediately recall Thelma and Louise and the freeze-frame imagethat ends that famous film is a somewhat appropriate reference—busting out of boundaries…total individualempowerment…friends to the end…yee haw. Ho and hum.<strong>Richardson</strong> employs a light touch that tends to sidestep such thematically obvious broadsides.12

13Wagons roll, 2003/07

More accurately, Wagons Roll is <strong>Richardson</strong>’s Chuck Jones moment. A longtime animation director, Jonessent Wile E. Coyote off a thousand cliffs, followed by a directional puff of smoke, only to hang in theair before cold reality set in and sent our anti-hero and his desire for roadrunner flesh plummeting in along, slow drop to reality. <strong>Richardson</strong> depicts the eternal moment before the fall. It might all collapsebut in <strong>Richardson</strong>’s work “might” is a two-way street. It might all come to end in a blaze of absurdity.Then again, we just might make it after all. Even the title of the work points to some indomitablepioneer spirit.Even <strong>Richardson</strong>’s most bald-faced one liner transforms, in an instant, into an eloquent moment ofpluck. A rubber tire lies flat on the road. Then it rouses itself, gets up, and ambles off screen. It is thework with the most gigantic cheek quotient, but it works precisely because it is so overt about its owncharm. It is no small proposition to make a rubber tire chaplinesque. Even describing it that way soundstrite, but it’s true. Even better, even sweeter, that it looked so harshly pathetic lying on the road underthe hot sun.It’s all so blatantly hokey and hilarious and ebullient. That it is titled The Sequel and we neverknow what preceded it is moot. How bad could it have been if you can dust yourself off and move onwith such panache? But hokum and hilarity are not <strong>Richardson</strong>’s ultimate arbiters of meaning. They arepart of a big bag of tricks—conceptual, compositional, technical—employed to suggest that if there is asword of Damocles hanging over all our heads, it is not only double-edged, but made of rubber.John Massier, Visual <strong>Art</strong>s Curator, Hallwalls Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>s Center, Buffalo, NY14

The sequel, 2004

<strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Park</strong>, 2008, Installation View at KW|AG.

Detail of frogs 2 (from the Supernatural series), 2001- present

Perpetual Anticipation:Crystal Mowry in conversation with <strong>Kelly</strong> <strong>Richardson</strong><strong>Kelly</strong> <strong>Richardson</strong>’s work has consistently offered viewers a beautified view of pending doom —a sense of awe and tranquil disaster via digitally manipulated images of unpopulated landscapes. Herrecent video works, in particular <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Park</strong> and Exiles of the Shattered Star, offer perpetual loops ofsophisticated hybrid landscapes. <strong>Richardson</strong> proposes a sublime mix of both fantasy and reality in imagesthat are as much about the present as they are the future. The following conversation with <strong>Kelly</strong> tookplace via email in December of 2007.CM: I wanted to start by asking you about your Supernatural Series (2001 - present)—a body of photographsdepicting landscapes from horror movies. In looking at them in relation to the video works of thelast five years, there seems to be a shared sense of artificial stillness. You’ve described the SupernaturalSeries in the past as depicting moments of serenity before or after a bloodbath—which to me soundslike a romantic version of the apocalypse penned by the English poet of your choice. This sense of stillnessthat you manage to create softens the blow of pending doom. Let me in on what attracts you tosuch images?KR: Throughout all of my work, I’ve been interested in simultaneity as a way of summating conflictingfeelings associated with the everyday. The Supernatural Series seemed to nail this in ways that previous20

works hadn’t by alluding to particular tensions around nature / society, promise / fear and the beautiful/ horrid. For me, they collapse a kind of fundamental and problematic condition of modern culture inrelationship with itself and that which supports it (the natural world) and articulates complex anxietiesand feelings associated with that.CM: The promise / fear dialectic you mentioned seems to be a natural fit for imagery with a connectionto the horror genre. Many of the films which are quoted for the Supernatural Series—B movies thatfew of us would even recognize (<strong>Forest</strong> of Fear?, Frogs 2?)—at some point depict the natural world asa brooding, sublime place where common sense doesn’t exist and the perimeter is hardly discernible. Itis a given that—in order to adhere strictly to this genre—there is at least one shot of said landscapeearly in the film. I can picture it, and I’m sure you can too. It’s usually nighttime or sunset, a forest ora jungle, without any humans visible in the landscape. This human absence seems pretty integral to theconvention, essential if viewers are to be convinced that the site is truly a risk. I’m curious about howyour work might employ a similar, though more sophisticated logic. Throughout your work we see landscapesthat we know have been visited by humans, yet these sites always seem as though they havebeen abandoned only to be discovered.KR: Within the opening scene-setting shot you mentioned, foreshadowing often occurs when the characterscomment on how beautiful it is. It’s true that a large number of these films depict the naturalworld as beautiful on one level and on another, a place which harbours something to be greatly feared,whether it’s a particularly lethal non-human predator (snake, wild boar, plague of vengeful frogs—take21

your pick) or some kind of human/animal/monster hybrid. I guess an aspect of my work is questioningwhat that is all about when in reality (to me) there is no competition between the danger we posevs. the rest of the non-human world; we win hands down. I try to make disquietingly peaceful, sublime,contemplative spaces which point to this trope while hopefully flipping it on its head somewhat.Similarly, human absence is integral to these works – not as a commitment to the conventionas such but by adopting it, it creates a vehicle for the viewer to find themselves within the work on amuch more personal level, as opposed to the focus being on a character or person. As Griselda Pollackputs it, “Landscape, as we know, can also be an imaginary space. More than topography, its paintedrepresentations have offered poetic means to imagine our place in the world. Represented land is moreoften than not a reflection of the human subjectivity which projects itself onto a space either of itssheltering habitation or its sublime otherness. The paradox of landscape is that it is both what is otherto the human subject: land, place, nature; and yet, it is also the space for projection, and can become,therefore, a sublimated self-portrait.”CM: The quote from Griselda Pollack makes me think of the mythical Minotaur creature, the half bull/ half human offspring from Pasiphaë’s tryst with a bull. In the myth, Pasiphaë has a wooden decoybull fabricated which she then wears to seduce the bull. What I find particularly interesting about thismyth is the aspect of mimicry and disguise. Though the success of the disguise seems completelyimplausible, I still love the ridiculousness of it. The Pasiphaë / Bull myth also captures that curiousaspect of our relationship with nature which both Pollack and you have also raised: though we may findourselves infatuated with its otherness, the romance is predicated on a perception that our “reason” and22

sophisticated industry will always keep things in our favour. How has mimicry and its motivations figuredin your recent work?KR: I’m quite interested in the idea of multiple realities, particularly with regards to our current mediaculture which acts as the interface through which we understand the world: TV, film, media, theinternet, etc. Within that, truth is difficult if not impossible to locate, it seems—with the line betweenfantasy and reality becoming more and more obscured. As such, over the last few years I’ve beenfocusing on creating photographs and video installations which reflect that in some way, combining bothreal and constructed elements.CM: While we are discussing fantasy, reality, and strategic mimicry it might make sense to address <strong>Forest</strong><strong>Park</strong>, the new work that you are showing here at KW|AG. To our regional audience, I am certain that thelandscape in <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Park</strong> will be familiar. Though you have divulged to me that <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Park</strong> was shot inthe nearby town of New Hamburg, viewers will also recognize the ubiquitous cleared lot that signals anew housing development. A frequent site in the recent years as the rural reaches of town seem to cedealmost overnight. <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Park</strong>’s vista is punctuated by numerous flickering streetlights, in what you havedescribed as a visual mimic of the sound of crickets. The effect is quite amazing and slightly unsettlingas it transforms a banal would-be suburb into a site of peculiar phenomena. For some reason, I can’thelp but suspect that the creation of this work was actually quite tedious and time consuming. How didthis piece evolve?23

FOrest <strong>Park</strong>, 2007KR: The streetlights in the space have been artificially lit in video post production in a way which notonly mimics the visual effect of mercury heating up within the first few minutes of turning on at duskbut as you’ve mentioned, flicker as if they are in conversation with the large choir of crickets chirpingwithin the landscape. The effect used has taken months to create on a home computer. I get theimpression that because special effects are found so readily within film and television people assumethat it is a fairly straight forward process to create them but it is actually fairly difficult to achieve onconsumer equipment given the huge amounts of data a single machine has to process. So the processfor producing this piece has been quite tedious, you’re not wrong—though by comparison to some of myideas, it has been a breeze.24

CM: In contrast to those “scratch-built” effects, found materials and images also seem to find their wayinto your practice, whether it’s in earlier sculptural works (broken drumsticks rebuilt with cork) or thenewer video works such as Exiles of the Shattered Star. Would you say that working this way, buildingfrom what’s already available, comes naturally to you?KR: Yes, very much so. I tend to collect elements of things that I come across within the everyday whichcatch my eye for one reason or another and hold onto them until they develop somewhat naturally intofully formed ideas, usually involving a combination thoughts and found materials, scenery, etc.CM: Is <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Park</strong> also, in some way, in some way an outcome of that tendency? Without any identifyingsignage, this cleared lot could be anywhere in the world. I wonder if the specificity—namely historicaland cultural baggage—of an existing location informs your decision to integrate it into your work?KR: In the case of <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Park</strong>, no not really; it’s more about the ever sprawling suburbia in Canada,overnight neighbourhoods full of promise and perfection. This one caught my eye because of the streetlightswhich had been installed despite the not-so-temporary lack of development which I found absurdlyamusing: the idea of illuminating an empty space. The ironic name for the subdivision “<strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Park</strong>”helped as well, considering that they cleared the land—sparing a spitting of trees in the bulldozer’swake. I originally filmed the landscape not knowing what I would eventually do with it, which lead ontoimagining electrical intelligence and a rather unlikely conversation.The location for Exiles of the Shattered Star was mainly chosen for the dramatic landscape, rather25

than the specificity of it as well. Though, the Lake District’s associations with early 19th centurypoetry seems fitting. I’m more interested in what these fairly ambiguous spaces allude to in terms ofour culture on the whole, rather than referencing something specific. That ambiguity allows for multiplereadings—and for me at least, a seemingly endless trail of thoughts.CM: Your work lends itself well to discussions of cinema—if not through its widescreen, 16:9 proportions,than certainly by its relationship to cinematic genres. The works featured in the KW|AG andHallwalls shows offer glimpses of quite differing locales and, though you mentioned that you favourthe ambiguous over the specific, there is still an overall sense of precision behind those choices. Atfirst blush, the works read as discrete tales with no apparent beginning or end, each existing in theirown nearly static version of time. But in considering the last six or so works you have made in recentyears, it is easier to see how they might be read as vignettes in what is essentially one larger, “frame”narrative.KR: I can understand that thinking. In some ways it is not dissimilar to any artist producing a body ofwork in whichever medium. There is certainly a larger framework which encapsulates the recent/currentdirection (as described above) but because of the cinematic language used, narrative often comes up inconversation. I’m not sure that I’m working with narrative any more than a painter would. I know whatI’m after and there is certainly a progression of ideas but to what end is unclear.CM: Since we started off talking about the sublime in a round-about way, I just wanted to return to that26

ief thread in our discussion. I read a quote recently that seemed resonant with your work, especiallywhen considering your last comment: “Perhaps the sublime is irony at its purest and most effective: apromise of transcendence leading to the edge of an abyss. Still, there may be a sense in which evensuch falls come to depend on ways of thinking that have no relation to any underlying material cause.” 1In its most basic form, the sublime has stood for effect—the overwhelming contrast between theimposing natural world (best represented by mountains and gorges) and the relative insignificance ofhuman perception. But postmodern versions of the sublime run the gamut from highlighting an almostcomic lack of certainty to attempts at creating sustained shock. I wouldn’t say your practice is eitherironic or shocking; but by dodging certainty in meaning, you offer up a heady comment on the sublimeand possibility.KR: Uncertainty is a rather apt note to end on. If these works act as visual metaphors for our modernreality: a wavering hybrid of fact and fiction—how can you speak of certainty within that?1. Philip Shaw, The Sublime (New York: Routledge, 2006), p. 1027

Detail of swamp thing (from the Supernatural series), 2001- present

LIST OF WORKS<strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Park</strong> | <strong>Kitchener</strong>-<strong>Waterloo</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>January 11 – March 23, 2008<strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Park</strong>, 20072 channel, high definition or standard definition video projectionProjected image is 25 feet x 7 feetExiles of the Shattered Star, 2006high definition, widescreen video loop, edition of 5, 29 min 59 secThe Edge of Everything | Hallwalls Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>s CenterJanuary 12 – February 16, 2008Exiles of the Shattered Star, 2006Ferman Drive, 2005standard definition video loop, edition of 5, 1 min 20 secWagons Roll, 2003/07standard definition, widescreen video loop, edition of 5, 24 min 37 sechowthedevil, 2002standard definition video, edition of 5, endless seamless loopThe Sequel, 2004standard definition video loop, edition of 5, 1 min29

About the ContributorsPrior to joining the staff of Hallwalls in early 2001, John Massier had been a curator and writer in Toronto for 13 years.From 1988 to 1998, he worked at the Koffler <strong>Gallery</strong> in Toronto, where he curated more than forty exhibitions of emergingand established Canadian artists. Massier has also curated exhibitions for the University at Buffalo <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, the SaidyeBronfman Centre in Montreal and Cambridge Galleries in Cambridge, Ontario. In 1997, he co-founded the local Toronto artjournal LOLA. He has written feature articles, profiles, and reviews for various galleries and visual art publications, includingCanadian <strong>Art</strong>, MIX magazine, Coagula <strong>Art</strong> Journal, THIS magazine, and <strong>Art</strong> In America.Crystal Mowry is a graduate of the Ontario College of <strong>Art</strong> and Design (AOCAD, 2000) and the Nova Scotia College of <strong>Art</strong>and Design University (MFA, 2002). Her work has been included in exhibitions at the <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> of Calgary, The KhyberCentre for the <strong>Art</strong>s, Halifax; the Klondike Institute of <strong>Art</strong> & Culture, Dawson City, YK; and most recently in Quantal Strife,a touring exhibition curated by Sally McKay and circulated by Doris McCarthy <strong>Gallery</strong> UTSC. In 2006 she co-curated TheTerrarium Project with Panya Clark Espinal, an interdisciplinary project featuring filmmaker Gail Singer, designer / historiansDavid Ross and Rebecca Duclos, artist / curator Andrew T. Hunter, and artist Denton Fredrickson. She is currently theAssistant Curator at the <strong>Kitchener</strong>-<strong>Waterloo</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>.<strong>Kelly</strong> <strong>Richardson</strong> was born in Canada (1972) where she studied fine art at the Ontario College of <strong>Art</strong> & Design (AOCADwith honours) and media studies at the Nova Scotia College of <strong>Art</strong> and Design (MFA studies). Her works have been exhibitedinternationally at various galleries including Le Mois de la Photo a Montreal / <strong>Art</strong>icule, Montreal (2007), Birch Libralato,Toronto (2006), The Nunnery, London, UK (2006), Northern <strong>Gallery</strong> for Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>, UK (2005), Gwangju Biennale,South Korea (2004), Stills <strong>Gallery</strong>, Scotland (2004), <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> of Nova Scotia, Canada (2004), <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> of Ontario,Toronto (2002-2003) and Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (2002). Her work was recently acquired by the Hirshhorn Museumand Sculpture Garden and will be featured in their upcoming exhibition The Cinema Effect: Illusion, Reality and the MovingImage (Feb-May, 2008). She lives and works in the United Kingdom and is represented by Birch Libralato, Toronto.30

<strong>Art</strong>ist’s Biography<strong>Kelly</strong> <strong>Richardson</strong>, Gateshead Tyne & Wear, UK | www.kellyrichardson.netBorn: 1972, Burlington, ON. CanadaEDUCATION2002-2003 Nova Scotia College of <strong>Art</strong> and Design – MFA, Media <strong>Art</strong>s program1993-1997 Ontario College of <strong>Art</strong> and Design – AOCAD with honours1993 Sheridan College – <strong>Art</strong> Fundamentals Intensive Program - DiplomaSOLO/TWO PERSON EXHIBITIONS2008 Birch Libralato, “Twilight Avenger”, Toronto, CanadaHALLWALLS, “The Edge of Everything” curated by John Massier, Buffalo, New York, USAKW|AG, “<strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Park</strong>”, <strong>Kitchener</strong>, Canada2007 <strong>Art</strong>icule, “Exiles of the Shattered Star”, as part of Le Mois de la Photo a Montréal, Montréal, Quebec, Canada2006 Birch Libralato, “Exiles of the Shattered Star”, Toronto, Canada2005 <strong>Art</strong>s Council England, “howthedevil”, Newcastle, UK2004 Cornerhouse (offsite), “howthedevil”, Manchester, UK<strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> of Nova Scotia, “Photopolis Photo Biennial: Future Perfect” curated by Bob Bean, Halifax, CanadaBodybuilder & Sportsman <strong>Gallery</strong>, Chicago, USA2002 Robert Birch <strong>Gallery</strong>, Toronto, CanadaHamilton <strong>Art</strong>ists Inc., Hamilton, Canada2001 Floating <strong>Gallery</strong>, “Picture This”. Winnipeg, Canada2000 Mercer Union Center for Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>, Toronto, Canada32

2000 Platform <strong>Gallery</strong>, “Jello”. Melbourne, AustraliaRed Head <strong>Gallery</strong> Showcase, “Birdhouse” curated by Jenifer Papararo, Toronto, Canada1998 .in/attendant. <strong>Gallery</strong>, “Mimic”. Toronto, CanadaSELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS2008 Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, “The Cinema Effect: Illusion, Reality and the Moving Image”, curatedby Kerry Brougher and <strong>Kelly</strong> Gordon, Washington, USA2007 Berwick Film and Media Festival, “Film on Film”, curated by Rebecca Shatwell and Iain Pate, Berwick, UKBig Screen Federation Square, “Otherworldy”, curated by Michelle Kasprzak, Melbourne, AustraliaTANK TV, www.tank.tv, London, UK2006 The Nunnery, “Visions at the Nunnery”, London, UKCastlefield <strong>Gallery</strong>, “The Sequel”, Manchester, UK2005 Northern <strong>Gallery</strong> of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>, “Thinking the Unthinkable”, curated by Alistair Robinson, Sunderland, UKKoch und Kesslau, Berlin, GermanyMSVU <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, “Free Sample”, curated by <strong>Kelly</strong> Mark, Halifax, Canada2004 Gwangju Biennale, curated by Kerry Brougher and Milena Kalinovska for the Americas, South KoreaStills <strong>Gallery</strong>, “DRIFT”, curated Iliyana Nedkova, Edinburgh, ScotlandSESC Vila Mariana, “Imagens que jamais voce jamais verá na TV”, Sao Paulo, BrazilChiang Mai University <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, “Switch Media Festival”, Bangkok, ThailandCine Buraco, “hole”, Rio de Janeiro, BrazilRobert Birch <strong>Gallery</strong>, “Worts: Another Dimension”, Toronto, Canada2003 Anna Leonowens <strong>Gallery</strong>, “Grade School”, Halifax, Canada2002 <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> of Ontario, “Provisional Worlds” curated by Jessica Bradley, Toronto, Canada2002 Pompidou Center, “Polyphonix Festival – Polyphonix 40” Paris, FranceIslip <strong>Art</strong> Museum, “Accumulations”, curated by Karen Shaw, Long Island, New York, USA2001 <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> of Ontario, “Video Primer”, curated by Michelle Jacques, Toronto, CanadaHuashan <strong>Art</strong> District, “Orange Marble”, curated by Manray Hsu. Taipei, Taiwan33

2000 Smack Mellon, “White Hot”, curated by Regine Basha and Moukhtar Kocach. Brooklyn, NYGalerie SKOL, “Companie”, curated by Sally MacKay & Daniel Olson. Montréal, Quebec1999 HALLWALLS, “Phenotypology”, curated by Maureen McQuillan. Buffalo, NYRobert Birch <strong>Gallery</strong>, “here”, curated by Michelle Jacques, Toronto, CanadaCold City <strong>Gallery</strong>, “Video Survey”, curated by Pamela Meredith. Toronto, Canada1998 Koffler Center for the <strong>Art</strong>s, “Edge of Everything”, curated by John Massier. North York, CanadaCOLLECTIONSHirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington DC, USAMusée d’art contemporain de Montréal, CanadaPrivate collectionsRESIDENCIES AND AWARDS2008 ISIS <strong>Art</strong>s <strong>Art</strong>ist in Residence, Newcastle, UK2007 Canada Council for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travel Grant2006-2007 /sLab International <strong>Art</strong>ist in Residence, Sunderland, UK2005 Canada Council for the <strong>Art</strong>s Project Grant2004 <strong>Art</strong>s Council England Project Grant; Canada Council for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travel Grant2002 Canada Council for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travel Grant; Nova Scotia College of <strong>Art</strong> and Design MFA entry scholarship2001 Ontario <strong>Art</strong>s Council Project Grant2000 Ontario <strong>Art</strong>s Council Project Grant; Canada Council for the <strong>Art</strong>s Travel GrantOntario <strong>Art</strong>s Council Exhibition Assistance Grant, Robert McLaughlan <strong>Gallery</strong>2000 Ontario <strong>Art</strong>s Council Exhibition Assistance Grant, Mercer UnionOntario <strong>Art</strong>s Council Exhibition Assistance Grant, WARC1999 Ontario <strong>Art</strong>s Council Exhibition Assistance Grant, McMaster Museum of <strong>Art</strong>34

SELECTED REVIEWSDault, Gary Michael, “A peaceful apocalypse”, The Globe and Mail, August 12, 2006Goddard, Peter, “Fiery missiles on a restful day”, Toronto Star, August 17, 2006Lau, Charlene K., “Provisional Worlds”, samplesize, 2003Deal, John. “Intersections”, View, vol. 8 no.2, p 16. January, 2002Kendzulak, Susan. “<strong>Art</strong>ists lose their marbles”, interview with Manray Hsu, Taipei Times. March 11, 2001McKay, Sally, “Birdhouse”, shotgun review in Lola 6. summer, 2000Papararo, Jenifer, “In Studio-<strong>Kelly</strong> <strong>Richardson</strong>”, Lola 5, 2000Armstrong, John, “Location-Location-Location”, [review of 10 years of Robert Birch <strong>Gallery</strong>], C Magazine, Sept-Oct., 1999MacKay, Gillian. “here”, The Globe and Mail, <strong>Gallery</strong> Going. February 27, 1999CATALOGUE ESSAYS / BROCHURESGordon, <strong>Kelly</strong>, catalogue essay for “The Cinema Effect” at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, 2008Massier, John and Crystal Mowry, catalogue essay/interview for “<strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Park</strong>” at the KW|AG/HALLWALLS, 2008Fraser, Marie, catalogue essay for “Le Mois de la Photo a Montreal: Replaying Narrative”, 2007Corsano, Ortino, catalogue interview for “Free Sample”, March 2005Robinson, Alistair, “Thinking the Unthinkable”, exhibition brochure for the Northern <strong>Gallery</strong> of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>, 2005Kalinoska, Milena, “Gwangju Biennale”, exhibition catalogue for the Gwangju Biennale, 2004Shapiro, Beverly, “<strong>Kelly</strong> <strong>Richardson</strong>: Gwangju Biennale”, exhibition catalogue, 2004Bean, Robert, “Photopolis Photo Biennial exhibition brochure for the <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> of Nova Scotia, 2004Nedkova, Iliyana, “DRIFT”, DRIFT exhibition brochure, 2004Bradley, Jessica, “Provisional Worlds”, exhibition catalogue for the <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> of Ontario. November, 2002 – March, 2003Shaw, Karen, “Accumulations”, exhibition catalogue for Islip <strong>Art</strong> Museum. September – November, 2002Milne, Anne, “Intersections”, exhibition brochure for Hamilton <strong>Art</strong>ists Inc., January 2002Hsu, Manray, “Orange Marble”, exhibition brochure for Orange Marble. February 2001Jacques, Michelle. “Video Primer”, exhibition brochure for the <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> of Ontario. April 7, 2001 – March 24, 200135

Massier, John. exhibition brochure for Mercer Union. May 25 - June 28, 2000McKay, Sally and Daniel Olson, “Companie”, Galerie Skol / YYZ <strong>Art</strong>ists’ Outlet exhibition brochure. March 2000Papararo, Jenifer, “Birdhouse”, exhibition brochure for Red Head Showcase <strong>Gallery</strong>. April 2000McQuillan, Maureen. “Phenotypology”, exhibition brochure and calendar for Hallwalls Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>s Center. April 1999Jacques, Michelle. “here”, exhibition brochure for the Robert Birch <strong>Gallery</strong>. February 1999ARTIST TALKS / GUEST LECTURER2008 Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington DC, USAUniversity of Lethbridge, Lethbridge, Alberta, CanadaKW|AG, <strong>Kitchener</strong>, CanadaHALLWALLS, Buffalo, New York, USA2007 BALTIC Centre for Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>, Gateshead, UKNorthern <strong>Gallery</strong> for Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>, Sunderland, UK<strong>Art</strong>icule, Montreal, CanadaNewcastle University, Newcastle, UK/sLab, University of Sunderland, Sunderland, UK2006 Blyth Community College, Blyth, UK2003 Anna Leonowens <strong>Gallery</strong>, Halifax, Canada2002 <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> of Ontario, Toronto, Canada2001 ICRT radio interview, Taipei, TaiwanHuashan <strong>Art</strong> District, Taipei, TaiwanTainan <strong>Art</strong> Institute, Tainan, Taiwan2000 Toronto School of <strong>Art</strong>, Toronto, Canada1999 Ontario College of <strong>Art</strong> and Design, Toronto, Canada36

<strong>Kelly</strong> <strong>Richardson</strong> wishes to thank Crystal Mowry (KW|AG), John Massier (Hallwalls), James Hollis, Jonathan Rust, Eric and JuneWhittaker, Ian Newton, and the installation crew who worked on mounting each of the shows.<strong>Kelly</strong> <strong>Richardson</strong> is represented by Birch Libralato, Toronto.Cover: Detail of <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Park</strong>, 2007. Image treatment for cover by James Hollis.Installation images by K.J. Bedford, KW|AG. All Images are courtesy of the artist.Copyright© 2008 <strong>Kitchener</strong>-<strong>Waterloo</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, Hallwalls Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>s Center, and the artistISBN: 978-0-9782669-8-1Cover Design: James HollisPublication Design: C.MowryPrinted by Embassy Pro Books, Oakville, ON<strong>Kitchener</strong>-<strong>Waterloo</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>101 Queen St. North | <strong>Kitchener</strong>, Ontario N2H 6P7 | CANADA | www.kwag.on.caHallwalls Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>s Center341 Delaware Avenue | Buffalo, NY 14202 | USA | www.hallwalls.org