198042.czech news - Czech Cultural Center Houston

198042.czech news - Czech Cultural Center Houston

198042.czech news - Czech Cultural Center Houston

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

New MembersVelke KoloBeatrice Mladenka-Fowler& Jesse FowlerFounderErvin Adam, MD &Vlasta Adam, MDHelen & Lynn BlankenburgMidred & Joseph BordenElizabeth CupittMarion & J.H. FreemanZahava HaenoshMarietta HetmaniakJerry & Victor HolyDoris & Edward JanekMary Jane RozypalSallie & Wayne WendtPatronSara Ann BartonJanet & Glenn RawlinsonShelly Sekula-Gibbs, MDMargaret & Albert SmaistrlaDan UrbanekSandra & Ken VoytekHon. J.C. Zbranek &Nelda ZbranekJerry ZmeskalFriendMelinda & Mark KubalaLinda MayElbert & Emma MachacMontgomeryTeryle & Lyle MorrowRev. Msgr. Dan ScheelValeria & Ben SheppardBetty Joyce SikoraPam VojacekStephen VranaMargaret WakemanTracey & Norman ZetkaCorporateJody BlazekFamilyLaura Bowne &Lana SullengerElise & John CyrRobert & Anne DybalaSharron & Tamim El HajeMildred & DonaldGrahmannLinda & Barry HluchanNellie & Louis RychlikClaudine & Chris SkuciusIndividualAnna AshmoreHelen A. BaineIn Memory of Peter J. BaineRosie BodienRaymond FitzgeraldAndrew Hardwick-BohovcikFrank HorakFrances JonesTommie LostakThomas PesekLaura PilgrimDorothy M. RainerPamela RezabekMatthew RobeyThomas RyzaLawrence SodolakLisa Sikora ThompsonMember Update (September 9, 2003 to January 9, 2004)Dorothy TumlinsonMember RenewalsMary Ann AkersBeatrice R. BarlerLadd BednarTerri K. BernathRobert & JoAnn BilyJoyce & Willie Bohuslav, Jr.Lucy & J. J. BroschMarge CalvertWilla Mae CervenkaNancy ChlodnickiDorothy H. ChowenskiViola Krejci CoxIrene CrossEsther Fojt Cunningham<strong>Czech</strong> Catholic UnionMarilyn DeMarcoTerri DockalJames DoubekPamela & William DrastataFr. Vincent DulockJan V. DuraEdward J. DworskyGladys & Marcial ForesterVeronica H FrostCarolyn & Glen GerkenHelen Komanec GreenCathy & Ted HajdikSibley & Milton HavlickEdwin HlavatyStephen HlavinkaJerrie & Victor HolyMary & Daniel HolubMargie HornColleen HruskaJoseph HurkaBette & Jerry HurtaDaniel I. JezekJean & Joe JungbauerAnn JureckaHenrietta KleckaViola KlinkovskyJuanita & Daniel KocianDennis KokasLynne & Doug KokasPalma & Jerry KoudelkaVictor KovarRichard KratovilLinda KutachDorothy & Emil KvapilKatherine & Eugene LabayErnest & Delores LaitkepJudith & John Lanik, Jr.Robert A. LoganHelen & Roger MarshLydia & Thomas MarshVickie MatochaCathy & Ronnie MatthewsVlasta MatticeSusan & Roger MechuraGrace A. MensikDonna & Guenter MerkleLeta Mae MiddletonDavid Miller, MD &Sally Miller, Ph.DLois & Paul MizerakDorothy & Alois MladenkaLinda & David MooreAnn & Charles OrsakElizabeth & Steve OrsakPat ParmaMary Grace & Tony PavlikAlice & W.F. PearsonElsie PecenaRonald D. PechacekJoseph PeslBernice & Robert PetruDonald Pisar, MDSr. Rosanne PlagensMary Ann PolkRichard PowellDolores PowerKay & Ronnie PruettVal & Jan RaslDennis RoederRose Marie Baca RohdeElsie RoznovskyBarbara Jircik Schlattman &Russell H. Schlattman II,DDSJean & Drew ShebaySylvia Jez SchillerAnna SchindlerLillie SchneiderMarilyn & Charles SikoraFrances SowderSPJST Lodge #172Sylvester SudaMary & Ben SymmankMargie Jez TomanDiane & Jorge TraconisCharlotte & Henry A. TyrochDorothy & Ben UlbrichMarjorie E. WhiteCarole & Clifford VacekRebecca & Roy VajdakSylvie C. VavraLinda & Gene VeselkaMaureen & SylvesterViaclovskyStanley VrlaCharles WaliguraCecile WheelerLoretta & Dale WhittingtonRita WilhiteNatalie WoodruffFrank Yanda, Jr.HonorsCecilia ForrestBob ForrestAndrew ZurikRobert Z. ZurikMemorialsAdele GlombCharles PustejovskyHarvey & Olga DolezalMeaselsDianna & Ken DormanAlfred Kolar & Frank SobolikKaren HallMemorial/Honor WallBurnette Jurica BoyettLucy & J. J. BroschClara & Johnny BrozRaymond R. Darilek, Jr.Lillian Horak DulaneyConnie & James EdeLinda G. EllisJ.H. & Marion FreemanAdelma GrahamZahava HaenoshJerry & Victor HolyLeslie & Gladys KahanekKelli & Phillip NevludClarence & Bobbie PertlBernice & Robert PetruPamela RezabekJustine Jurica RivoireT h e N e w s o f T h e C z e c h C e n t e r3Margaret & Albert SmaistrlaAnn Maresh WheelerCapital CampaignAnnual Fund GiftsSpecial BenefactorBetti & Charles SaundersBenefactorDelores Jansa &Arthur M. Jansa, MDLouis J. and Millie M.KocurekCharitable FoundationMBC FoundationMary Grace & Tony PavlikMary & Frank Pokluda, Jr.Patron SponsorJustine J. RivoireFounding FriendBank of America,Matching GiftMary Jane RozypalKarolina Adam, MD &John G. DickersonHelen & Lynn BlankenburgEugene CernanGeorgia KrauskopfMinnie PetrusekDebbie & Billy ShortnerNaomi Kostom SpencerPamela VojacekSpecial SponsorEdna & Bill CoxLillian DulaneyRobert J. DvorakJan V. DuraCharles HeydaAudrey KlumpKathy KokasDavid KvapilEleanor & Thomas LeibhamJeanette & James MalloryDennis MasarRev. George J. Olsovsky, Jr.Gerald OpatrnyErnest J. OpellaCathy & Thomas PolkAnnual SponsorJerry ElznerJean & Joe F. Jungbauer, Jr.Garry M. KramchakIsabel MatusekSylvester SudaAnnette M. ZinnRobert ZurikOtherRosalie & Frank BannertVeronica H FrostGarry Kramchak<strong>Houston</strong> Alumnae of ZTASr. Rosanne PlagensDonationNorma AshmoreRosie BodienJoseph HurkaKrogerLawrence SodolakClarence TarnowskiGala VIII UnderwritersBarbara Von Zuben FosdickCLUB 200Norma Ashmore*Martha & Earl AustinJoyce & Jim BrausVictoria CastleberryFather Paul ChovanecAllen+ & Dorothy ChernoskyMarvin Chernosky, MD &Jean ChernoskyRobert J. DvorakDanna & James ErmisCecilia & Bob ForrestCynthia GdulaLorraine Rod GreenOleta & Louis HanusLynn & Purvis Harper, MDVirginia & Henry HarperBernice Cernosek Havelka+Chris HlavinkaAnn HornakRoy M. HuffingtonDelores Jansa &Arthur M. Jansa, MDEdwin JureckaGladys & Leslie KahanekTomas Klima, MD &Marcella Klima, MDJulie Halek KloessLillian & Robert KokasTim Kostom+ &Rosa Lee Kostom+Betty & Mark Kubala, MDMarta R. LatschAnn & Elbert LinkCora Sue & Harry MachThelma Burnett MareshMBC FoundationJohn P. McGovern, MDJudy & Paul PasemannCharlie PavlicekLindsey, Sarah, &Sherry Rosene PierceTony & Mary Grace PavlikMary & Frank Pokluda, Jr.Frank Pokluda, IIIJustine RivoireEffie & Bill RoseneBetti & Charles SaundersDon Sheffield &Nancy Chernosky SheffieldGrace SkrivanekClarice Marik SnokhousRaymond J. SnokhousLilian & H.M. Sorrels, DDSWilliam E. SouchekNaomi Kostom SpencerJohn R. VacekPatsy A. Wells*Denotes new listing+DeceasedMembershipAmembership in the <strong>Czech</strong><strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Center</strong> <strong>Houston</strong>beside being rewarding to theindividual is a necessary andvital component of our organization.Please considerthese membership levels:Donor’s Circle MemberFriend $150 (3 year)Patron $500 (5 year)Founder $1,000 (lifetime)Benefactor $5,000 (lifetime)Velke Kolo $10,000 (lifetime)Basic Annual MemberFamily $40Individual $25Student $15Corporate $100Non-profit Org. $100

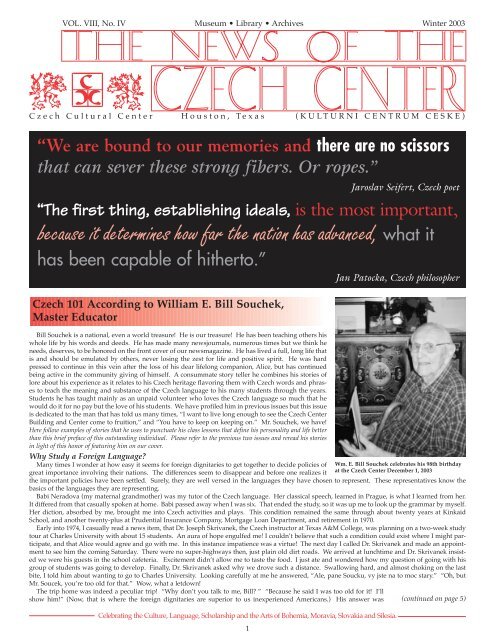

Board of DirectorsEffie M. Rosene, ChairmanJames E. Ermis, Vice ChairmanRev. Paul ChovanecRose Hrncir DeatheRobert J. DvorakAnn HornakRobert KokasBeatrice Mladenka-FowlerPaul PasemannSandra Jircik PickettLarry PflughauptBetti Friedel SaundersClarice Marik SnokhousPatsy Veselka WellsNatalie WoodruffHonorary Board MembersThelma Burnett MareshWilliam E. SouchekDorothy Chernosky &Allen Chernosky+Julie Halek KloessLouis & Oleta HanusBernice Cernosek Havelka+Tim+ & Rosa Lee Kostom+Leslie & Gladys KahanekFrank & Mary PokludaGrace SkrivanekNaomi Kostom SpencerJohn R. Vacek+DeceasedOfficersEffie M. Rosene, PresidentW. G. Bill Rosene, V. P.AdministrationJames E. Ermis, SecretaryAnthony E. Pavlik, TreasurerLindra Vondra Smith, Ass’tTreasurerHonorary <strong>Czech</strong> ConsulsRaymond J. Snokhous –(Texas)Kenneth H. Zezulka –(Louisana)It should be noted we appreciatethe work of former <strong>Czech</strong> Consul,Jerry Bartos of Dallas recentlyretired.Masterpiece: Our Lady of theHoly Rosary.<strong>Czech</strong> Republic Floods – A RetrospectiveAletter from the Prague Post Endowment Fund acknowledging receipt of a $1,000.00 donation to be used to restock books and rebuilddamaged structures of <strong>Czech</strong> schools and community libraries damaged or destroyed in the <strong>Czech</strong> Republic floods of August 2002 rekindleda thought of this momentous event that had been obscured by events here in the United States and events that were occurring affectingour own organization.Floods unlike any in living memory struck Bohemia beginning on August 7, 2002. The resulting disaster is unprecedented in modern<strong>Czech</strong> history. The flooding, which resulted in the highest water levels in more than a century, was primarily the result of rainfall over abroad area, including southern Bohemia. Here, in just a few days, more rain fell than is normal for the entire year. The first flooding tookplace on the Cerna Malse River flowing out of the Nove Hrady Mountains, along the <strong>Czech</strong>-Austrian border. Soon after, rivers all oversouthern and western Bohemia began to rise simultaneously.The first reports of flooded towns and villages came from Ceske Krumlov, a UNESCO world heritage site which found itself submergedunder 13.1 feet of water from the Vltava River. Seven bridges in and around the city were swept away and dozens of roads damaged ordestroyed. In the city of Ceske Budejovice, waters flooded the center of the city, two residential districts and an industrial area. The municipalarchives were totally flooded. Nearby towns also found themselves under water. The stone bridge in Pisek, which dates from the thirteenthcentury and is the oldest bridge in Central Europe was badly damaged and one of its Baroque statues was carried away in the torrent.(The <strong>Czech</strong> <strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Center</strong> contributors sent funds to aid in the restoration of this historic structure along with money to anelementary school in Pisek that had suffered damage to its library.) A catastrophe on this scale had not been recorded in the 755-year historyof Pisek.The Luznice River, swollen by waters from the huge fishponds around Trebon, flooded towns and cities all along its course. Fears thatthe dam holding back the Rozmberk pond would burst fortunately proved to be unfounded – the town ended up awash in “only” six andhalf feet of water. The swollen Dyje River in southern Moravia flowed over the dam of the Vranov reservoir flooding homes in the townof Znojmo. Majdalena and Metly, two southern Bohemian villages that were almost completely destroyed have become symbols of the<strong>Czech</strong>s’ futile struggle with the floods. Metly was wiped out of existence in only ten minutes by a 26-foot wave of floodwater from a burstdam. (Majdalena was the recipient of contributions from the CCCH for the repair of their church.)By Monday, August 12, it was clear that the floods posed a serious threat to Prague. First to be evacuated was Karlin, a day later policecleared Kampa Island. The Prague zoo had to be evacuated and unfortunately a number of rare animals were lost that could not be movedin time. The Vltava continued to rise and by the time it crested it was flowing at the rate of 159,000 cubic feet per second, a new record.Old town was partially flooded, Charles Bridge survived the onslaught, unlike other bridges and water gradually engulfed eight percentof the city territory.Tens of thousands of irreplaceable documents disappeared into the waters from the archives of the Academy of Science, the <strong>Czech</strong>Philharmonic, the <strong>Czech</strong> Statistical Office, several government ministries, the National Technical Museum and the Historical Institute ofthe Army. Water made its way into sixteen of Prague’s Metro stations in some cases reaching to the ceiling. Many parts of the City werewithout electricity. Even northern Bohemia was not spared. Damage is incalculable but estimates range from two billion dollars in propertylost from the flood.Ed: The <strong>Czech</strong> <strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Center</strong> <strong>Houston</strong> was proud to be a contributor in a small way to several villages, the Prague Post Endowment Fund and theJewish Museum thanks to the largesse of many caring individuals that are members of our organization. We thank them for their caring response. ❧Masterpiece PaintingsFound Restored at Fayetteville ChurchIt started with the surprise discovery of a beautiful old painting, found hiding behind a mirror in a room that was used for storage inthe rectory at St. John the Baptist Catholic Church in Fayetteville, Texas.Current priest, Father Jack Maddux, was clearing stored items to do a little remodeling in the rectory when he discovered the painting.A parishioner took the work of art to <strong>Houston</strong> to try and get it dated, and have it re-framed. Well known historic art restorer Antonio Loroof St. Mark’s Fine Arts Conservation and Restoration informed the parish priest that he had found a museum-quality work of art.Word of the find leaked out, and soon it was discovered that three more paintings were housed in the Fayetteville Museum on thesquare, where they had been in safekeeping for many years. Soon two ladies brought another one back to the church as it had been loanedout some years back. No one is really sure who loaned it to whom, but the women involved felt it was time to return it to the church.Finally, a last painting was found in what is called the “smallest Catholic Church in the world,” St. Martin de Tours Catholic Church inWarrenton.All of the paintings needed some restorative work, some more than others. But Father Maddux had a picture of the church from the1870's, from the inside that showed all the paintings in their original splendor inside the beautiful church.Loro did some research and discovered that the masterpieces were created by Ignaz Johann Berger, a Moravian artist who paintednumerous altarpieces. He was most known for his religious paintings, including several passion cycles that were of typical compositionand likenesses of the day. Ignaz Johann Berger was the artist who painted these masterpieces for St. John the Baptist Catholic Church inthe late 1800’s. A Moravian he was born July 8, 1822 and died June 29, 1901 in a small town called Neutitschein. Moravia was once partof the Austro-Hungarian Empire surrounded by Hungary, Bohemia, Austria, and Prussia. He was the father of Julius Victor Berger andthe nephew of Anton Berger, both painters as well. He worked with his uncle from 1842 to 1860 in the Company Workshop in Neutitschein.In 1841, he took a field trip for instruction to Vienna where he made numerous copies of old masters to improve his technique.Berger worked most actively in Moravia and Silesia as well as Slovakia where he painted numerous altarpieces. He was most wellknown for his religious paintings, including several passion cycles that were of typical composition and likenesses of the day. He did genrescenes as well as portraits. His genre paintings and historical paintings were painted more in the style of Biedermeier. His interpretationof flora and fauna in the backgrounds of his work was naïf in the style to Russeau. His paintings reflect a highly skilled and educatedartist. His skin tones are full of life and his likenesses are of real people that the onlooker can identify with. Berger was lucky to haveenjoyed great success in his life.There is a long list of parishes, which house his paintings, mostly in Moravia, but also in Poland and Hungary as well. Even after hisdeath, his work was seen and appreciated as etchings used to illustrate calendars, hymnbooks and religious texts.The six paintings include: St. Martin de Tours, right inside the church; and over the altar are, from left to right: Our Lady Queen ofHeaven, Sts. Peter and Paul, St. John baptizing Jesus, Sts. Cyril and Methodius, and Our Lady of the Holy Rosary.Father Maddux has documentation that the congregation, in the mid 1800’s, wrote to Frenstat requesting a <strong>Czech</strong>-speaking priest forFayetteville (the one they had spoke Polish and they couldn’t understand him) and a painting of their church’s namesake, St. John theBaptist. This is likely where they got that painting. How the church got the rest of the masterpieces remains a mystery.“I feel blessed to be a small part of this.” Maddux said. He quoted one parishioner, Louis Polansky, who said: “These other places havethe painted churches. We have the church of the paintings.”Cyndi Wright, Fayette County Record ❧T h e N e w s o f T h e C z e c h C e n t e r4

Bill Souchek (continued from page 1)correct! His meaning was: “Your age is toomuch more than the age of the college studentswho are going!” So forgive me, Dr. Skrivanek!Fate must have played a part in all that happenednext! The following week I drove toAlvin, Texas because I always saw its name inthe periodicals I received. Their CommunityCollege was well known and many <strong>Czech</strong>namedstudents lived in the surrounding area. Itwas relatively easy to get to see Dr. Webber, whowas in charge. After our introduction he askedwhat my visit was for. I told him, and receivedthe most cordial and interesting response.“Believe it or not, Mr. Souchek, but I have hadtwo calls already this morning about a <strong>Czech</strong>Language course. And to top it all, Ms. OlgaDolezal Measels just left this office and wants usto start an enrollment.” He asked about mybackground and how I had been employed. Heordered an application, asked about past experiencein teaching and other more minor questions.“Mr. Souchek, I’m sure this will check-outperfectly, so you might as well start gettingready for your next September class.” Wow, thatwas easy!The oldest record of the September, 1976 classcontains the following students: Foster Burnett,Annie Chovanec, Jan Jircik, Dorothy Kuchar,Tommie Lostak, Olga Measels, Harry W.Monych, Joe Netiack, Eddie Sebesta, HildaSebesta, Eleanor Stuksa, Dolores Tacquard, JoeVrazel, Nina Vrazel and Sally A. Mikulastik.They formed a dedicated, hard-working group,met promptly and were sincere in their efforts tohave a speaking knowledge of <strong>Czech</strong>. Recordsindicate many reregistered for future classes,and their efforts clearly show their love of<strong>Czech</strong>, the language of their forefathers. Thissincerity of purpose was evident during aboutten years of study. Frequently I hear from` a fewof the class even today.The Alvin class met once per week, and someoneheard there was a demand for a similar classat San Jacinto Community College. A brief meetingwith Dr. Honeycutt of San Jacinto assured usof a night-scheduled period. The registered listincluded: Francis Buchta, Kay Cernoch, StanleyCernoch, Elsie Esterak, Toni Hart, AndrewHolub, Edith Holub, Cecilia Klecka, HenryKorenek, Tommie Korenek, Joe Machann, VlastaMachann, Mary Masterson, Glenda Mikeska,Viola Mulraney, Billie Oliphint, Lillia Mae Peter,Victor Peter, Diane Prochazka and LarryProchazka. Just as in the Alvin class, all wereloyal students with the exception of two whowere anxious to show their importance. Theyknew a better instructor who quit after a shortperiod. Even today those misfits are all smiles,but watch-out!The third evening class was registered atSpring Branch. Like the Alvin class, it had studentswho were positive they wanted to learnthe language of their ancestors. The night drivingto the three classes was beginning to showits effects on my wife and me, so we had to giveup our interesting classes. At that time SPJSTwished to offer <strong>Czech</strong> classes, they suggestedmy doing the teaching. We also met once weekly,there was less nighttime driving and it totaledabout 14 years. Father time does keep hisadding machine oiled well and it indicates therestill is a serious request by the present day <strong>Czech</strong>population to learn more about their ancestors.You can get busy with the question, or let someother up-and-coming city do it!At this writing there is a three-grade level<strong>Czech</strong> language study being held at <strong>Czech</strong><strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Center</strong> <strong>Houston</strong>. There seem to bemany who are interested in learning about the<strong>Czech</strong> Republic and especially about the townsor villages of their ancestors. So, good luck inyour quest and study about the land of yourforefathers!Tombstones Reveal Our ThoughtsOur parents lived in Chicago for about twoyears where brother Joe was born. They didn’tlike it there very much because of the crowdedcity. Father had a pretty good job in Gary,Indiana at a steel mill. It was very heavy workand rather dirty, so when the opportunity aroseand several workers heard that the chances ofemployment in Iowa City were good, theymoved to Iowa to work in the limestone quarries.The work was just as tedious as in the steel millin Gary, but it was all in the open air and cleaner.Mr. Joseph Foucek was living alone. His wifehad passed away recently and he didn’t like livingalone. His home was in east Iowa City abouta mile from the quarry. As luck would have it,father and Mr. Foucek met accidentally. Mr.Foucek’s home was a one-story home with abasement apartment for it was built on a hillside.There was sufficient room for our family tomove-in, so two families with similar namesoccupied the one building. Mr. Joseph Foucek(the owner) and Mr. Joseph Soucek (the renter).Agreements were reached in all things mutually.Brothers Henry and George were born at thebasement apartment address. Sister Helen wasto be born soon and more space was required forcomfortable living. The neighborhood was whatthe folks liked so they purchased a lot for theirfirst home. There was space for a large garden,an area for chickens and a large barn for a cow..Money was needed for construction of a framehome and barn. They applied for a loan at CSPS,they became members of the organization, andbefore long they were building their first homein America.. Sister Helen was born there a fewmonths later. The quarry job, though difficult,paid $1.75 per day and mother walked aboutthree miles to do Dr. Saunders’ stacks of officelaundry. Life was good, they grew their ownvegetables, had all the eggs needed for makingnoodles, etc. and milk galore for the family. I wasto be born the next year, and grandmotherNerad together with aunt Vincie were to comelive with us. That was a grand idea, for mother’sworkload would be less with the help of grandmother.The greatest problem was housing ofthe whole group. Mother noticed a two-storyhome for sale while trudging through the snowto Saunders.The home at 1014 North Summit Street onfour acres, a large garden, beginning of a vineyard,an orchard and a barn. The cost was$2,000.00. CSPS was satisfied with the paymentsof the other home so gladly made another loanon the new home. I was born there December 1,1905. Good Luck played along with us becauseall of us worked as a team. There is where thegood old <strong>Czech</strong> work-habits gave the necessaryshove upwards.Mr. Josef Foucek became an atheist, he livedby himself after we moved but came to see usoften. He arranged all the details of his funeraleven to the selecting and making of a rather largetombstone. The stone was erected on his cemeterylot months before his death. It was aboutfive feet tall, the tall column supported a series ofround plates and the base was a series of foundationblocks. But the most noticeable featurewas the <strong>Czech</strong> epigraph inscribed in two curvedlines: Zaziva o Boha nedbal, A po smrti dabla se nebal.“While living he did not care for the Lord, andafter death he wasn’t afraid of the devil.”Whenever we’d take a summer vacation tripback home we always went to see the tombstone.About twenty years ago we went to seethe unusual tomb. We couldn’t find the stoneand regretted that we had never snapped a pictureof it. The sexton was digging a grave nearby,so we went to him with our question. Hetold us that about a year ago distant relatives ofJosef Foucek were ashamed of the stone, so theypurchased a special lot and had the bodiesmoved from the old lot to the new burial spot.Mushrooms at $1.29 a PintWhenever I hear the word mushroom I immediatelythink of Vlasta, my sister-in-law. When itbecame necessary for my two oldest brothers togive-up their title to their Dakota homesteadbecause Frank became ill with pneumonia, theymoved to Omaha. He finally, regained hishealth and both searched for employment. Tomsecured a job at a <strong>Czech</strong> print shop. A short timelater Frank also got a job there because theyspoke and wrote <strong>Czech</strong>. Line-o-type is a specialty-learnedtalent. There is where Tom metVlasta. The three of them moved back to IowaCity. Finding employment was relatively easyfor the two brothers. The Iowa City PressCitizen, the daily <strong>news</strong>paper, also printed for theUniversity. It was a standing joke among us,that the two never had any time for themselves.Though the use of mushrooms in cooking is astandard thing in a <strong>Czech</strong> family, we never didso at home. Vlasta, the big city (Omaha) daughter-in-law,introduced us to the delicacies. Wesoon learned that there are many varieties ofmushrooms, some are edible and some deadlypoisonous. The edible variety grows in cut-overtimberland and during certain seasons. Thosewere times we looked forward to. “Mark it onyour calendar, the last two weeks of Septemberand the first two weeks of November.”Saturdays were ‘no school days’ so those fourSaturdays meant doing something special. Afterour usual chores were accomplished, we’d headfor Stillwell’s pasture about two miles distant,climb the fence and start searching for mushrooms.We carried a bushel basket with usinstead of a flour sack so the prizes wouldn’t bemashed and ruined. The only other equipmentnecessary was a sharp kitchen knife. ❧T h e N e w s o f T h e C z e c h C e n t e r5

The House Signs of Old Pragueing, for instance “At the Iron Door,” or “Atthe Three Steps.”The first house signs appeared in Praguearound the middle of the fourteenth centuryon the imposing houses of the rich merchantclass in the city’s commercial center, and inthe coming centuries they spread to most ofthe buildings on the markets, squares andmain commercial streets. Because these werebuildings whose owners had the right tobrew and sell beer, the house signs also invitedpassers-by to come inside for a drink.In an era when hereditary family names andcoats-of-arms were the privilege of the aristocracy,and family names had not yet come intogeneral use, the house sign identified not onlythe buildings but also their owners. In shortenedform, the name of the house might wellbe taken for the family name: Simon Prsten(“Ring”), for example, was in fact the owner ofthe house that went by the name “At the Signof the Ring,” while city councilor Pstros(“Ostrich”) was really Havel from the house“At the Sign of the Ostrich.” Many names thatoriginally designated buildings then remainedpermanently as family names.Since house signs are in a sense the illegitimateoffspring of heraldry, they were originallygoverned by heraldic rules. This is clearfrom the figures that were used (the oldestknown being the stork, deer, lion, star, unicorn,hat, crayfish, lily, rose and so on) as wellas from the colors that were employed. Overthe course of time, house signs began to distancethemselves from the world of heraldryfor purely practical reasons. For example, theauthentic heraldic crayfish is red and mostcrayfish used as house sign over the centurieswere also red. But in order to distinguishbetween several houses employing the sign ofa crayfish, Praguers needed more colors, andso blue, green and even silver crayfishappeared. The range of medieval symbols wasnot great, and as the number of imposing housesgrew, the symbols began to be repeated.At the end of the seventeenth century cityofficials introduced a regulation (not widelyheeded) stipulating that in addition to thehouse sign, every building should also have avisible orientation inscription stating thename of the building, for example: “This goesby the name of At the Three Pheasants,” or“This goes by the name of At the GoldenHead.” The reason for this was to avoid confusionbetween genuine house signs and thegrowing number of votive statues and signboardsthat tradesmen and craftsmen placedoutside their shops. But because culturaldevelopments are seldom shaped by officialregulations, the officials in the end had to givein and accept more than one craftsman’s signboardand votive statue as valid house signs.In most cases, unfortunately, the origins ofthe hundreds of house signs derived fromcraftsmen’s signs will always remainunknown. Only exceptionally is it possible totrace one back to a specific individual. InT h e N e w s o f T h e C z e c h C e n t e r6They slumber timelessly above the changingstreets, like pale, dusty illustrations in along forgotten picture book. They are characterizedby a rich variety of shapes, colors,materials and styles. They include paintings,inscriptions, actual objects and symbols,heavenly bodies, wild animals and saints. Butonly some of them: those that gave the buildingstheir names – deliberately or by chance,as byproducts of the endlessly inventive fermentof cultural creation. They play theirsmall role in helping to create the specialatmosphere of the streets and have become somuch a part of the facades that only by lookingat them carefully are we able to perceivethem as something separate. Even then weare most interested in their form from theartistic point of view, sometimes more, sometimesless accomplished, at times very grandand at others charmingly simple.“One of the most modest arts,” as thepainter and writer Josef Capek put it, whendescribing the signs on the facades of thebuildings of Prague.More than three hundred house signs stilldecorate the facades of Prague buildings.Each of them has its own history, often morethan six hundred years old, as well as its distinctiveappearance and the charm of beingone of a kind. But how did people in the pastgo about choosing symbols for their homes sothat no one was misled or confused?House signs date from the Middle Ages,and were a product of the culture of the richurban merchant class. They were introducedfor very practical reasons. In the long streetsthe similar facades of the Gothic buildingsmerged into one another in such a way thatonly someone who knew them well could orienthimself: x lives opposite Jira the cobbler,beside the red door, where the blue shuttersare, behind the meat stands. But for anyonenew to the city, this was of little help. And soin the fourteenth century there suddenlyappeared visible designations of the housesthat took the form of highly visible signs withimages of various kinds. The rich merchantclass imitated the way the aristocracy andhigh clergy of the age of chivalry markedtheir property. While the coats-of-arms of thenobility were bound by strict rules of heraldry,the signs on the houses of the merchantclass took on all sorts of forms. Most oftenpanel paintings were found, but also statuesin wood and stone, frescoes painted directlyon fresh plaster, inscriptions and actualobjects hung from the facade of the building.But not everything affixed to the facadebecame a genuine house sign. This was onlytrue of those that were taken up by the peopleof the city, those that they quite unconsciouslycame to associate with particular buildingsand so employ as designations for the buildings.Sometimes a building received a nameby chance, as when some incidental detailwas transformed by the playful spontaneityof cultural creation into the sign of the buildtoday’sJungman Street, for example, the signof three bells was originally used by thefamous bell-maker Brikci; the sign of a wheelin Karmelitska Street goes back to the wheelwrightJan Stefl; the painting of three ostricheson the house at the western end of CharlesBridge was ordered from the painter DanielAlezius of Kvetna by Jan Fuchs, who madeornaments for hats (in which ostrich featherswere a key element).For practical reasons, the signs for alehousesand taverns (and later coffeehouses) were thesame all across Europe. This meant that noone was in any doubt as to the meaning of the“wisp” (small bundle of straw), green “bush”(bunch of vine leaves) or blue or goldengrapes that marked these establishments.These often became house signs, but eventhese signs changed with the times. So forexample in the seventeenth century redhedgehogs were popular as a sign for alehouse,while in the eighteenth century goldentigers could often be found on signboardsoutside coffeehouses.The profession of a former owner of a buildingcan often be deduced from the house signit bears, since people liked to dedicate theirhouses, which also served as their workshops,to the patron saint of their particular crafts.Even when the house sign depicted awhole scene from the life of a saint or holyperson, the house was sometimes namedafter a single detail, not necessarily thatsaint’s particular attribute. This can be seenparticularly often in the case of manyMadonnas, whose number meant that theycould hardly serve as identification markers.Buildings with statues of the Virgin Maryhave names like “At the Golden Grating,”(the grating protecting the statue), “At theGolden Rock” (the small mound on which thestatue stands, “At the Golden Apple” (held inthe hands of the infant Christ cradled by hismother), “At the Painting,” “At the GoldenFrame,” “At Our Lady of Mercy,” and so on.The gallery of saints in the streets of Praguedropped dramatically with the onset of theRenaissance, which led to a secularization ofthe motifs used in house signs and a rise inthe frequency of natural motifs. However,from the mid-seventeenth century on, theCounter Reformation set out deliberately toincrease the number of religious symbols. Butthe great variety of patron saints of crafts andtheir attributes found in the Middle Ages wasnever again attained. The main additionstended to be crucifixes, angels and paintingsof the Virgin Mary.In the eighteenth century, the steady urbanexpansion led to a realization that in the largeEuropean City that Prague was becoming, thesystem of house signs and names was a relicof the past, impractical for purposes of orientationas well as from an administrative pointof view.(continued on page 7)

The House Signs(continued from page 6)In 1770 Prague buildings were numberedfor the first time, and then again in 1795, butit was only with the third attempt in 1868 thatthe idea really caught on. Three generationsof Praguers stubbornly rejected the use ofnumbers, preferring in their conservativefashion to stick to the system of house names.Proof of this can be seen in a number of neoclassicalhouse signs from the end of the eighteenthand first half of the nineteenth centuriesthat include both the visual symbol ofthe house name and the number. They beareloquent testimony to the extent to whichhouse signs had become firmly associatedwith the buildings they graced and with theday-to-day life of the city dwellers.At almost the same time that house signsbegan to fade away and lose their significance,the first modern champions of the phenomenonappeared on the scene. They did notdefend the signs out of a love of the past perse; it was more that they regretted the way thestreets of the city were losing the modestbeauty that was so much a part of them.When the modernization of Prague at theend of the nineteenth century began to bringwith it the widespread demolition of oldbuildings and whole streets in some quarters,the priority shifted from defending the signsto rescuing them. The Prague MunicipalMuseum began to seek out signs recoveredfrom demolished buildings, in the end collectingaround seventy of them.The people of Prague are very proud of thesigns on the city’s old buildings. They lookafter them and take delight in them and tellstories about them. In the last decade in particular,when many of the city’s buildingshave been returned to their former owners ortheir descendants, they have regained theirold color. Their new owners have not onlycarefully restored the remaining signs, buthave in many cases made new signs toreplace the old ones that had long sincedisappeared, but which are attested to inhistorical records.Lydia Petranova, The Heart of Europe ❧“At the Three Hearts,” 14 Uvoz Street.<strong>Czech</strong> Language Lessons<strong>Czech</strong> is a hard nut to crack.This lesson we discuss peas, nuts, seeds andthe like. Although peas were a staple food inthis part of Europe only a couple of hundredyears ago, they were later replaced by the morefilling potatoes and never regained their onetimefame.Probably the most favorite type is the greenpea-hrach. If you are trying to persuade somebodyor make them do something and the personjust won’t listen to you, you can say to je jakoby hrach na stinu hazel or “it is like throwing peasagainst the wall,” or “it’s like talking to a brickwall.” Very large tears can be likened to greenpeas-slzy jako hrachy. About oversensitive andpicky people, especially women, you can saythey are like princezna na hrachu - the Princessand the Pea, who was so delicate that she couldfeel a single pea under twenty mattresses.Attractive, strong and healthy looking women -the opposite of the delicate princess - can bereferred to as holka jako lusk - a “girl like a pod.”Poppy seeds have an important place in<strong>Czech</strong> cuisine and it’s no wonder that theyfound their way into <strong>Czech</strong> phraseology as well.If you do not like something ani za mak - “not fora poppy seed” - you don’t like it at all. If somethingdoes not make an impression on you, if itis neither fish nor fowl, you can use the rhymingexpression ani takovy ani makovy - literally “neithersuch nor with poppy seeds,” neither onething, nor another. If you feel indifferenttowards something, for example if you don’tcare whether you buy black or brown shoes, youcan say you will take takovy nebo makovy. Theword for poppyhead - makovice is often used in ajoking way to describe a person’s head.A nut is orech in <strong>Czech</strong>. The figurative meaningof the word is “a difficult problem.” If a taskis described as tvrdy orech, it means it will be atough nut to crack. And to solve a difficult problemis rozlousknout orech-“to crack a nut.” Onetype of nut is the almond - usually used todescribe the beauty of a woman’s eyes - oci jakomandle.English and <strong>Czech</strong> share the expression “toplant a seed of doubt” - zasit semeno pochybnosti.Another agricultural metaphor is used toremind people that they will have to bear theconsequences of their acts. Co sis zasil, to si takysklidi what you have sown you will have to reap.Forest fruit and mushrooms.There are <strong>Czech</strong> idioms concerning wild floraspecifically for wild berries and mushrooms.Mushroom picking is a popular pastime in thecountry and maybe that’s why there are quite afew idioms using the words mushroom – houba -the boletus, a kind of edible mushroom. Anidiom: Nove domy rostou jako houby po desti - newhouses are springing up like mushrooms afterthe rain. New houses, or anything like that, suchas restaurants or factories, are shooting upeverywhere and very quickly. If something fitsinto its surroundings very well, if it sits prettilyin the middle of something, such as a house in agarden, we can say that it sits there like a mushroomin moss - jako houba v mechu.To describe someone in sterling health, we sayje zdravy jako houba - he’s healthy as a mushroom,he’s hale and hearty, he’s as fit as a fiddle.In informal language the word houby can bealso used instead of the word ne - no as anexpression of strong disagreement or it can beused as a synonym for the word nic - nothing.Muj zivot stoji za houby – my life is worth nothing,my life isn’t worth living. Another expressionusing the word mushrooms or houby iswhen parents or grandparents talk to little childrenabout the time before they were born; theysay, To jsi jeste byl na houbach - “It was when youwere still picking mushrooms,” or “It was whenyou were just a twinkle in your father’s eye.”But why unborn babies are thought to be pickingmushrooms is a mystery.About berries: A pretty girl can be likened to astrawberry - divce jako jahoda, or a raspberry-divcejako malina. The same comparison can be used todescribe appealing red lips: rty jako jahody, lipslike strawberries or rty jako maliny-lips like raspberries.If somebody is really hungry and wolfsdown his food, you can say slupnul to jako malinu- he gulped it down like a raspberry.The touch of wood lesson.The <strong>Czech</strong> word for wood or timber is drevo.In metaphorical use it also means a clumsyperson. One can also sleep like a piece of wood- spat jako drevo. People can be stupid like wood- hloupy jako drevo or deaf like wood - hluchy jakodrevo. Although <strong>Czech</strong>s more often say hluchyjako poleno - as deaf as a log, or hluchy jako parez -as deaf as a tree stump. The expression sladkydrevo or sweet wood is a poetic name for aguitar.The short <strong>Czech</strong> word les means forest. Nositdrevo do lesa is to carry wood to the forest, or touse an English idiom, to carry coals toNewcastle. If a child is growing up withoutenough supervision, if he or she is allowed torun wild, <strong>Czech</strong>s say roste jako drevo v lese - he orshe is growing up like timber in the forest.About people who can bear a lot, who let peoplebehave badly to them and do not protest, <strong>Czech</strong>ssay necha na sobi drevo tipat - “He lets others tochop wood on him” or he lets people walk allover him.The next expression has a similar meaning tothe English phrase “you can’t make an omeletwithout breaking some eggs.” It goes: kdy se kaciles, padaji trisky, and the literal translation is“when a forest is being cut down, splinters fall,”meaning there are unpleasant side effects toimportant things. Another idiom: Pro stromynevidit les means “not to see the wood for thetrees.” The meaning is the same in both <strong>Czech</strong>and English: to be so involved in the details andnot realize the real purpose or importance of thethings as a whole.Amoralizing phrase: Jak se do lesa vola tak se zlesa ozyva - “the way you shout at the forest, theway the sound comes back.” The closest Englishidioms would be “you get as much as you give”or “what goes around comes around.”Na shledanou.Thanks to Radio Prague ❧T h e N e w s o f T h e C z e c h C e n t e r7

Concert HowlThursday evening, the 23rd of October 2003,Zdenka and I arrived at the PragueRudolfinum concert hall, breathless as usual,for our regular Thursday night concert of the<strong>Czech</strong> Philharmonic. We’ve had our subscriptionseason tickets for thirty-five years, andearly on we managed to secure what we felt tobe the best seats in the house; 1st row balcony,seats one and two, on the right side curve justover the orchestra, with a clear view of the conductorand soloists. Attending these concertshas been one of our greatest pleasures inPrague over all these years. But on thisevening, for second time this season, there wasanother couple sitting in our precious seats –German tourists. As politely as we could, weinformed these people of their mistake. Theseat numbering could be confusing, and perhapsthey should have been on the left side ofthe great arc of the balcony. But no, they firmlydisplayed their tickets, and sure enough theyhad been issued the exact same seats as ours.I muttered to Zdenka, “With all their newcomputers, these ticketing nitwits were stillcapable of selling the same seats twice!” Shetrotted off to the balcony entrance and summonedthe usher, a gentle woman, who certainlydidn’t want any fuss just before the concertwas to begin. With a discreet glance atboth tickets, she suggested that the touriststake the two seats behind us, which luckilywere unoccupied.The concert was sensational, one of the verybest of the season. The brilliant star-quality ofthe new chief conductor of the <strong>Czech</strong>Philharmonic, Zdenek Macal, led the orchestrain a superb performance of Sergei Prokofiev’sPiano Concert in D Major, with the brilliantRussian/American pianist Alexander Toradze.We were dazzled and delighted that we didn’tmiss this major musical event.During the intermission, we went to ourusual spot in the Rudolfinum lobby for ourcustomary chat with old friends who share thesame concert dates. They are even older thanwe, and have both been in frail health. Theydidn’t appear, and we were worried aboutthem. Zdenka intended to phone them, but thenext morning we had to leave for Germany toattend an animation workshop in the city ofHalle. Our next concert was shortly after wereturned, and we hoped to see our friends thistime during the intermission. But as wearrived and settled in our usual seats, this timewithout squatters, we began to rave about theprevious concert with people who regularly sitnear us. They were baffled. “There wasn’t anyProkofiev concerto at the last concert,” theyinsisted.By this time surely, you can guess the endingof this story. We had mistakenly arrived atthe wrong concert, somehow gliding in, wavingour plastic season tickets and haughtilydisplacing the German couple who had paid ahigh price for these prime seats!Neither the concert hall doorman whowaved us in, nor the kindly woman ushernoticed that our tickets were for the wrongevening – nor of course had we, who arealways in a rush, and have something goingnearly every evening.Somewhere out there is an angry Germancouple, probably spreading the word about theinept ticket handling in the <strong>Czech</strong> Republic,and who may not wish to ever return! To themwe are on our knees, begging for forgiveness,and offering our most humble pie apologies!On the other hand, we enjoyed a sensationalsymphony concert, including a superb performanceof Beethoven’s 5th Symphony afterthe intermission, with prime seating, absolutelyfree! And we did have a funny story to tellour friends during the intermission of the nextconcert, which we properly attended with ourproper tickets!Gene Deitch – author of For the Love of Pragueon sale at our Gift Shop. See www.czechcenter.orgto order. ❧CSGSI Conference in <strong>Houston</strong>:President CSGSI,Paul Makousky andEffie Rosene.Guenter & Donna Merkle,<strong>Houston</strong> Folk Dancers.Robert Ermis, Sr. AnitaSmisek and at piano,Robert Dvorak performfor the <strong>Czech</strong>oslovakGenealogy SocietyInternationalConference in <strong>Houston</strong>October 2003.James Ermis, Mom and her son Mark Bigouette.Part of the CSGSI group tours the <strong>Czech</strong> <strong>Center</strong><strong>Houston</strong> Museum Gift Shop.Kroj Review at CSGSI conference under direction ofHelene Baine Cincebeaux.40th Annual Slavic FestivalDan & Kathy Hrna,Slavic Festival October2003.<strong>Czech</strong> Princess, SarahPierce and ProgramChair, Donna Merkle.<strong>Czech</strong> Heritage Singers & Dancers of <strong>Houston</strong>,Bessie Treybig, Isabel Matusek, Viola Dworaczyk,Mary Peska, Henrietta & Jaro Nevlud, Frances & BillBollom at the Slavic Festival.Leslie & Gladys Kahanek, daughter Diana andhusband Brian Weldon and flagbearers grandsons,Justin 18, Nathan 15, Andrew, 11.Fall Music FestivalConcert Master,ChristopherAnderson greetscomposer RobertDvorak at theNovember 22, 2003Regional FallPhilharmonic MusicFestival (both areCCCH members).T h e N e w s o f T h e C z e c h C e n t e r8

Paths of Glory and TribulationsThree historical vignettes will focus on crucialevents and leading personalities, whichshaped the history of a small, but by no meansinsignificant country in the heart of Europe.The purpose of these is to enhance the appreciationof their ethnic heritage.Beginning with an explanation of“Bohemia.” It is derived from the Latin termBoiohaemum, home of the Boio, coined byancient Romans in reference to a Celtic tribe ofBoii who inhabited this territory from the middleof the 4th century BC until the 1st centuryAD. The flowering of the fairly advancedCeltic civilization was interrupted by hostileinvasions of the Germanic tribe of Marcomanniwho in turn encountered the vanguards of theRoman legions. Emperor Marcus Aureliuswrote his Meditations on the banks of the HronRiver deep within a territory claimed by anotherGermanic tribe, the Quades.The original homeland from which theSlavic tribes began their migration sometimebefore the turn of the 5th century AD, wasbehind the Carpathian Mountains, between theriver Dnieper in the east and the Vistula Riverin the west. The cause of the mass Slavic migrationis the subject of speculation. It might havestemmed from the relative overpopulation ofthese regions where primitive agriculture wasnot productive enough to sustain populationgrowth, or in the aggressive drives of neighboringtribes to obtain more land for themselvesby pushing the Slavs from their settlements,or even drastic climatic changes. Thewestward movement of the Slavs to new territorieswas facilitated by the fact that manyregions had been either deserted by theGermanic tribes, or their population was decimatedby the plague pandemic that ravagedmany European locations during the 6thcentury.There are many legends relating to thearrival of the <strong>Czech</strong> people into their newhomeland. However, it is important to understandthat despite their plausibility and popularappeal, these stories, passed on throughoral tradition, fall into the category of fiction.These mythological tales which glorify thevaliant exploits of ancient heroes are foundamong many civilizations. The so called“Revivalist Movement” of the 19th centurywas aimed at reawakening of national awarenessand nourishing aspirations for autonomyamong the <strong>Czech</strong> people who were subjugatedunder the autocratic regime of the AustrianHabsburgs. The revivalists (buditele) in theirpatriotic zeal frequently embellished theseearly sagas to bolster the movement towardself-determination. This romantic trend toimmortalize the heroic past continued into theearly 20th century. Among the outstandingpainters who devoted much of their talent,time, and energy to extol the heroes and heroinesof <strong>Czech</strong> antiquity, were Josef Manes,Mikolas Ales, Frankisek Zenisek, VojtechHynais, Vaclav Brozik, and Alfons Mucha. Inthe sculptural genre it was primarily JosefVaclav Myslbek and Antonin Wagner whocreated remarkable classical statues conceivedhistorical figures. Many of these masterpieceswere awesome allegories based on harsh warfareas well as peaceful domestic life of theSlavic people. Alois Jirasek, an accomplishedstory teller and author of patriotic novels, succeededadmirably in popularizing legendarynarratives to the extent that they have becomewidely accepted by the populace as true historicalevents and were assigned as requiredreading in <strong>Czech</strong> schools.The first among the early legends is thestory describing the arrival of the <strong>Czech</strong> tribeunder the leadership of Forefather Cech(Praotec Cech – see Editor’s note) into the territoryknown by the Romans as Boiohaemum.This tale is undeniably analogous to theBiblical story of Moses leading the Israelitesinto the Promised Land. According to thisversion, after many months of peregrinationand struggle with hostile elements, the <strong>Czech</strong>scrossed the river Vltava and climbed upon thenearby mountain Rip, from all indications anextinct volcano. From its summit Cechviewed the fertile land below and pronouncedit highly suitable for permanent colonization.After appropriated sacrifices offered to theirpagan gods, the tribesmen decided to namethe new homeland “Cechy,” after theirrespected leader. These first <strong>Czech</strong> settlersengaged in agriculture, animal husbandry,hunting and fishing, while their arts and craftsdeveloped from various forms of idolatry andworship of dead ancestors.The alleged successor of Cech was aFrankish trader Samo who reportedly unifiedthe Slavic tribes and developed a successfulmilitary strategy against the invading Avars.Samo’s realm disintegrated after his death in659. Very few historical facts are availableabout the period of 174 years, between 659 –833. (There is well-documented history of theGreat Moravian Empire founded by Mojmir Iin 830.) Another early <strong>Czech</strong> legend is Samo’sheir apparent, a man called Krok, highlyesteemed for his judicial wisdom. Krok iscredited with moving his sovereign residencefrom Budec to a newly built fortress on theright bank of the Vltava River. His threedaughters were Kazi, Teta and Libuse. Kazibecame known for her healing skills, Teta forher priestly ability to communicate withpagan gods, and Libuse for her kindness, wisdomand prophetic powers. It was Libusewho ascended the throne after her father’sdeath. Unable to maintain full respect andconfidence of men, she chose a husband forherself, a nobleman named Premysl. Anappointed delegation of elders followedLibuse’s white horse that led them to a fieldthat was being plowed by Premysl. He at firstbemoaned the untimely arrival of the messengers,predicting that an unplowed field signifiedfuture scarcity of food, even famine, forthe land. Following the emissaries toVysehrad, Premysl was espoused to Libuseand together they founded the Premysliddynasty, which ruled Bohemia for several centuries.In an inspired moment Libuse prophesiedthe glorious future for the newly establishedtown of Prague in these words: “I see alarge metropolis whose glory will reach thestars.” The Libuse legend, especially herauguries, inspired the great <strong>Czech</strong> composer,Bedrich Smetana to create a highly patrioticopera, performed only in the <strong>Czech</strong> languageand presented on special occasions.Another ancient <strong>Czech</strong> legend describes thetime when the <strong>Czech</strong> women rebelled againstthe male domination. Under the leadership ofVlasta they waged war against the men oftheir tribe. At first the maidens were quitesuccessful in staging surprise attacks andscoring victories both in small skirmishes andeven in large battles. The turning point in thisMaidens’ War was a treacherous assault conceivedby an enchanting seductress Sarka,against a small hunting group of men led byCtirad. Pretending to have been chained to atree and abandoned by her female companions,Sarka convinced Ctirad and his retinueof her misfortune. After loosening her chains,the unsuspecting men drank from a flask ofintoxicating mead and fell asleep in the heat ofthe summer day. Deceitful Sarka, using ahunting horn, then summoned the femalewarriors hidden nearby who quickly attackedand slaughtered the drowsy male hunters.This tragic episode so angered the men thatthey staged a final attack upon the maidens’stronghold, Devin, which they burned downand killed all remaining female combatants.There are many other ancient <strong>Czech</strong> legends,which have over the years inspirednumerous <strong>Czech</strong> painters, sculptors, poetsand composers to create impressive works ofart. Most <strong>Czech</strong> schoolchildren can also recitefrom memory the names of the first eightPremyslid rulers: Premysl, Nezamysl, Mnata,Vojen, Vnislav, Kresomysl, Neklan, andHostivit.Tony Jandacek Hlas NarodaEd: Article submitted by Julie Skubal. The <strong>Czech</strong><strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Center</strong> <strong>Houston</strong> has acquired a beautifulpainting by <strong>Czech</strong> artist Jiri Grbavcic that has as itstheme and is based on the legend of Praotec Cech. Thispainting will be proudly displayed in our new culturalcenter building. ❧We Need You!Desperately!We are in need of bookkeeping/accounting assistance.We are in need of sales associates in theMuseum Gift Shop – The Market Place.We are in need of docents for the <strong>Czech</strong><strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Center</strong> <strong>Houston</strong>.We are in need of pretty much anythingyou could offer to assist.The <strong>Czech</strong> <strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Center</strong> <strong>Houston</strong> isbuilt on a Volunteer Foundation –people building a legacy. Flexiblehours would be available. You will besurprised at the pleasure and good feelingyou derive from working from theheart meeting other people as fine asyou. <strong>Czech</strong> heritage is helpful, butcertainly not a requirement.Thank you!Effie M. RoseneT h e N e w s o f T h e C z e c h C e n t e r9

<strong>Czech</strong> President’s Visit to DallasOn Monday, September 22, 2003 a delegationof Frank and Mary Pokluda, James andDanna Ermis, Father Paul Chovanec, RobertDvorak, Effie and Bill Rosene from the <strong>Czech</strong><strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Center</strong> <strong>Houston</strong> was present alongwith 350 others at an event at the AnatoleWyndham Hotel to hear economist and <strong>Czech</strong>President Vaclav Klaus in a dialogue with JohnGoodman, president of the National <strong>Center</strong> forPolicy Analysis, which organization arrangedfor his visit to Dallas.Mr. Klaus maintained that the <strong>Czech</strong>Republic’s whirlwind shift from socialism to afree enterprise system proves that marketswork and the subject of his visit was to discusshis part in the mammoth change.When Vaclav Klaus was inaugurated aspresident of the <strong>Czech</strong> Republic in March, hedeclined to deliver his first address from a balconyof the spectacular old palace overlookingthe square. He chose instead to speak in thesquare itself after which he ordered therestraining ropes removed and was mobbedby hundreds of his appreciative fellow citizenswhile the band played “When the Saints ComeMarching In.”The road from the “Velvet Revolution” of1989 through the “Velvet Divorce” of the<strong>Czech</strong> and Slovak sections of <strong>Czech</strong>oslovakiaat the end of 1992 to the relative prosperity ofthe present has been difficult.Klaus was appointed finance minister in thefirst post-communist government. His taskwas enormous: Change a Soviet-style socialistsystem into a free-market economy “as fast aspossible.” He noted that in 1989, “everythingwas in state hands.” Not a single privaterestaurant or hairdressing establishment couldbe found in gracefully aging Prague.“The people really expected some results,”so the new government decided to make thetransition from a centrally planned to a privatizedeconomy as abrupt as possible. Priceswere freed with a single stroke of the pen. “At8 o’clock in the morning, it’s done,” said Klaus.It was a dramatic step that led to an“inevitable” economic contraction that precededan acrobatic leap to prosperity. Within fouryears, 80 percent of the country’s assets hadbeen privatized. Klaus joked that MargaretThatcher has been justly praised for privatizingthree or four British firms per year. “Wedid three to four per hour.” Small companieswere sold at public auction. Major enterpriseswere liberated from state ownership via“voucher privatization,” in which ordinary citizenscould pay what Klaus called “a symbolic”(modest) price to acquire shares. “We werereally afraid that the people would not understandit,” Klaus explained. But 75 to 80 percentbought in, and “the stock market works.”President Klaus is an economist by academictraining, steeped in the free-market principlesof the Chicago and Austrian schools. Yethis “thinking was mostly formed by the irrationalityof the communist system,” heacknowledged.“In the 1980’s,” he said with a laugh, “therewere more Marxists on the Berkeley facultythan in all of <strong>Czech</strong>oslovakia.” And he added,“I didn’t know anyone who was a genuineMarxist.”Klaus’ evolution from economist to politicianwas spurred by this observation that the“crucial condition” for reforming a dysfunctionaleconomy “is to persuade the people thatit must be done.” So he organized a politicalparty and was elected Prime Minister.“Not all the <strong>Czech</strong> people feel better off,”Klaus admitted. Although everyone enjoysimproved material conditions “absolutely,”some have seen themselves decline relative toeconomic winners. Capitalism does not guaranteethat all enterprises prosper.President Klaus observed that he has notwon every political battle. He is not happythat his Republic’s membership in theEuropean Economic Union has come at a steepprice: adoption of Europe’s absurdly expensivewelfare system and rigidly controlledlabor markets.As an economist, Klaus understands thatthese burdens on production are destructive“in the long run.” But as a politician in a freecountry, the <strong>Czech</strong> president knows that hemust sometimes be flexible.Reported by Effie Rosene ❧His Excellency, <strong>Czech</strong> President, Vaclav Klaus(center) and Bill & Effie Rosene.Frank & Mary Pokluda and Bill Rosene.Paul Geczi, Effie Rosene,Professor Milan Reban.Rev. Paul Chovanec,Robert Dvorak.The President signsautographs.James & Danna Ermis,prior to event attendance.Fallout of Living underCommunist RuleThe first of May this year was just fine.Years ago when my niece was five she camehome from Kindergarten and said “Mommy,it’s OK if you die now, our Daddy Lenin willtake care of me.” My sister got one shock afteranother when soon after that, she caught thelittle girl cutting out pictures from a fashionmagazine she had been lucky to get fromsomebody coming from the West. “Why areyou angry?” she asked. “I’m just cutting outpictures of beautiful Soviet people. Ourteacher has told us about them.”When Chernobyl blew up at the end of Aprilsixteen years ago, the air was loaded with radiation.Our communist government tried tokeep the information from the people. Theirmain worry was that the people would notattend the traditional May Day Parade.I went away to the country with my childrenthat fine first of May Day. We were pickingdandelions to make dandelion honey. I hadexcused myself from attending the parade,stating that there were pressing family problems.Later, we threw out the dandelions eventhough the Party assured us that althoughthere had been an explosion, we had nothingto fear. It’s true that I have always been apeace-loving creature but at that moment mysincere wish was that the Soviet comrades aswell as ours, experience the very worst of tortures.The first of May 2003, <strong>Czech</strong> TV presentedits viewers with a lovely surprise. For a whole24 hours, people were able to watch old programsdating back to 1953 when TV broadcastinghad begun.What a variety of programs! The <strong>news</strong>reports dealing with May Day celebrationswere really fascinating, the marching throngswith banners proclaiming “Long Live theCommunist Party of <strong>Czech</strong>oslovakia!” thegoverning comrades on their tribunals lovinglywaving to the working masses. It wasmandatory for school children to march fromtheir school onto Wenceslas Square. Onlythere, were they allowed mixing in with thecrowd and disappearing. Nobody wanted tobear the banners and flags since it was thentheir job to carry them back to school.It is unbelievable that even today, fourteenyears after the official fall of communism, therestill exists a lot of totally confused people likemy little niece. They were there screaming inthe Letna Park. They no longer have the SovietUnion; all they have is Cuba and ComradeFidel Castro. It was in this spirit that thisdemonstration was being held. ComradeJirina Svorcova promised us from the tribunethat our land should again be happy after thecommunists gain back their power. Dear God,don’t let that happen! I’d rather be unhappylike I was yesterday as I picked the dandelionswith my grandchildren telling them about theMay Days of years ago. They laughed, notreally understanding, but found it amusing.For you my dear readers, I have a <strong>news</strong>paperclipping of those “beautiful Soviet people.”Well, not really Soviet, but <strong>Czech</strong> communistsin Letna Park.Eva Strizovska, <strong>Czech</strong> Dialogue, May 2003 ❧T h e N e w s o f T h e C z e c h C e n t e r12

Folk Painting on GlassFolk pictures on glass are from the very beginningof ethnographic activity some of the bestknown and the most collected products of folkart. Frantisek Mares paid attention to them in1893, two years before the <strong>Czech</strong>oslovakianEthnographic Exhibition was held in Prague.For those who were interested in folk art and forconnoisseurs of ethnography these pictureswere precious evidence of the folkways of lifeand their spiritual orientation. The next generations’attention was directed to the indisputableartistic value of the pictures, refined materials,alluring gaiety of colors and variety of individualthemes and subjects.Pictures prove, by their extraordinary form,graphic ability of folks of <strong>Czech</strong> and Moraviancountryside, as they show fundamental orientationof folk spiritual culture issuing from theinstigation, endeavor and devoutness ofBaroque time. Josef Pekar attempted to makeevident that roots of <strong>Czech</strong> folk culture fromboth ethnographic and art-historical point ofview lie in <strong>Czech</strong> patriotic Baroque, which is alsothe source of The National Revival. Similarly tomost of folk artifacts, painting on glass is not apure and sterile outburst of folk aesthetics andfolk habit as the romantic enthusiasts wished itto be. As well as folk woodcut and paintedNativity Scenes glass painting creates a transitionbridge from “high” norm-setting art to folkexpression. It is an evidence of mingling of<strong>Czech</strong> and Moravian culture and culture ofprovincial towns and cities as this process wasspeeded up in the 17th and 18th century. Glasspainting substantiates how impulses and stimuliinspired the so-called “culture of high classes”were reshaped in folk and semifolk environment.Nevertheless, to be able to fully understandthis process we have to disregard the widelyspread supposition about the impoverished andpoor countryside. The countryside was fairlywell economically self-sufficient and did notlead such a gloomy life. Quite often even thecountryside middle classes were on a higher economiclevel than towns where every adversity oflife (poor crop, epidemics, and wars) was easilyreflected. Government decrees objecting to theluxury of folk classes are the best evidence of theliving conditions in the countryside. A <strong>Czech</strong>Parliament ruling issued in 1545 (written in Old<strong>Czech</strong>) censures country people for wearing andbuying inappropriate and too showy clothes asgold lace bodices, cambric shirts embroideredwith gold, ostrich feathers, etc.The <strong>Czech</strong> countryside experienced similareconomic booms during the time of MarieTerezie’s reforms, during the French wars after1800 and especially as consequence of the devaluationof the Austrian fiduciary currency, socalled “schein” in 1811 and 1817.Pictures on glass together with faience andpewter dishes used to be a part of every cottageor manor house equipment. In addition to theirhousehold function they also played some sortof representative role, the quantity of themshowed wealth of the householder.People were buying them as suitable presentson various life occasions such as Baptism,Communion, Confirmation, church wedding,and later also saint’s name day. Believers collectedthem as reminders of pilgrimages to distantplaces.Pictures on glass created a significant dominantof otherwise whitewashed rustic chamber.They, as a rule, used to be placed on a ledge inthe corner over a corner cabinet in which thehouseholder used to keep documents, moneyand prayer books. This part of a cottage room inVallachia was called for the pictures placedthere, “holy corner,” and the place at the table onthis side was the most honorable one and wasreserved for the householder. Later the pictureswere hung symmetrically also in between windowsover a door or beds. In the second half ofthe 19th century they were gradually replacedby attractive pictures, made with industrialgraphic techniques as lithography, brominechromatographyand color prints.Painting on glass was popular in the15th century.Italian glass works in Venice produced inthe middle of the 16th century cycles on Christlife painted with precise renaissance techniques.From here popularity of glass painting wasspread to France where at the end of the 17thand beginning of the 18th century two mainstreams were separated. The old folk streamaffected Colmar and Alsace and ultimatelyGermany. The newer stream developed in theindustrial areas of France and was inspired bythen trendy miniature paintings. It depictedfirst and foremost world motives and drew itsinspiration partly from Boucher frivolous graphics.The process of transition from the styleforming art of glass painting to provincial art ofcraftsmen and painters of Altar Pieces developedin Bavaria and the Tyrol where someresearchers find roots of folk painting on glass inthis particular Bavarian - Austrian area of theSudeten. From this area these pictures wereexported in large quantities to <strong>Czech</strong> lands in the18th and 19th centuries.The Bohemian Forest (Sumava) is consideredthe cradle of glass painting in <strong>Czech</strong> lands. Theproduction of pictures on glass in the southBohemian town of Pohpro and Buchers and onthe Austrian side in the little town of Sandl isdocumented from the 18th century. Also at thesame time some centers in north Bohemia startedtheir production. Painting on glass inMoravia had fairly developed in the 18th centuryand that is why we can trace a strong influenceof late Baroque and Rococo.Approximately till 1700 pictures on glass preservedthe character of style arts and crafts andthey resembled with their style distemper paintings,if they were not painted with complicatedtechniques of enamel, grisaille or eglomisee.Not until classicism and empire were the characterof pictures more adapted to the style of thecountryside with its deeply preserved traditionalBaroque aesthetics. Secular themes were excludedand resplendent gaiety of red and gold colorscame back again. Rococo surrounded figureswith cartouches, medallions replaced more figuresor a whole series of scenes in the pictures.Pictures on glass were not produced only byglassmakers or professional glass painters inglass works (as it was thought beforehand), butalso by unskilled dilettantes. Authors were takingbasic material - most of the time defectivesheets of glass - from glass works. It does notmean that the production was concentrated inthe centers of glass industry. On the contrary,this gives an evidence of the development oftransport and trade. Sheets of glass were deliveredto painters even to quite faraway places.Considerable demand caused the necessity toincrease production. The production of pictureson glass was quickly manufactured. Specializedproducers, most of the time whole families,worked using and outlined pattern of the contoursof the pictures and then each of the otherworkers carried out according to his or her specializationa specific stage in the production. Forinstance one was an expert on faces, others onrobe folds, third on flower ornaments, etc. Atthe end the least skilled workers filled in thebackground. Folk producers drew their inspirationboth from older patterns and almost contemporaryart work from woodcuts, color printsand altarpieces and church decorations.There were many more centers of productionthan we are able to document today. Manywere in the Bohemian forest (Sumava), northand west Bohemia, Silesia (Jeseniky), the AshMountains, Javorniky (the Maple Mountains),Bohemian-Moravian Uplands (Ceskomoravskavysocina), central and south Moravia, and in theLuhacovice area.The paints were applied on the backside of asheet of glass. To emphasize the technique ofpainting “under glass” people used then atrendy term “underpainting.” This method ofpainting is very interesting. First the contourswere outlined, and then the actual painting wascarried out with parts of the picture that werecloser to the eye of an observer painted first.Fingers were painted before hands, eyes beforefaces, ornaments and folds of clothes before theactual dress. Then the background decoratedwith various ornaments was filled in. At the endthe picture was covered with the colored surfaceof background. The colored backgrounds weretypical for particular regions and bore evidenceof the origin of individual pictures: white fromSlovakia; black, south Bohemia and Moravia;light blue, north Bohemia and Silesia; marble,Frydek region. Glasspainters used first distemperor glue colors, later the pictures were paintedin oils. We should not forget to mention backgroundscreated by glass techniques such ascutting, matting either on regular glass or evenon mirror glass as such pictures are consideredto be produced in glass works alone.Pictures on glass are predominantly of religiousinspiration in folk environment and onlyrarely find secular motives as such as housenumbers, landscapes as in a cycle by Janosik, thefolk rebel, which was created at the end of the19th century and was rather a theme fromSlovak or Polish times. Janosik and “upperboys” were folk rebels from mountains andpainted out of purely commercial reasons.In the pictures one sees a whole rank of saints.They are patron saints of baptism and epidemics,Rochus, Rosalie, Sebastian; diseaseseyes, Ottillie, teeth, Apollonia; cattle pests,Wendelin and Linhart; and of blissful death,Barbara, Ann, Joseph. An important placebelongs to patron saints of different crafts andagrarian estate, Isidore, Lawrence, Urban. Someof the most popular are saints on horses, Martin,George, Anthony of Paduan, Francis of Assisi,Catherina, Wenceslas and John Nepomuk.Pictures depict saint of the Holy Family, Joseph;and of the life of Christ, The Miracle in Galilee,Whiplashing, the Last Supper, Ecce homo andHoly Sepulchre. Jesus as a child together withSt., John the Baptist is often portrayed. The mostwidespread are pictures of the Blessed VirginMary. There were more than 3000 pilgrim placesin <strong>Czech</strong> lands most of them being St. Mary’s(continued on page 14)T h e N e w s o f T h e C z e c h C e n t e r13