Teaching Students to Self-Monitor Their Academic & Behavioral ...

Teaching Students to Self-Monitor Their Academic & Behavioral ...

Teaching Students to Self-Monitor Their Academic & Behavioral ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

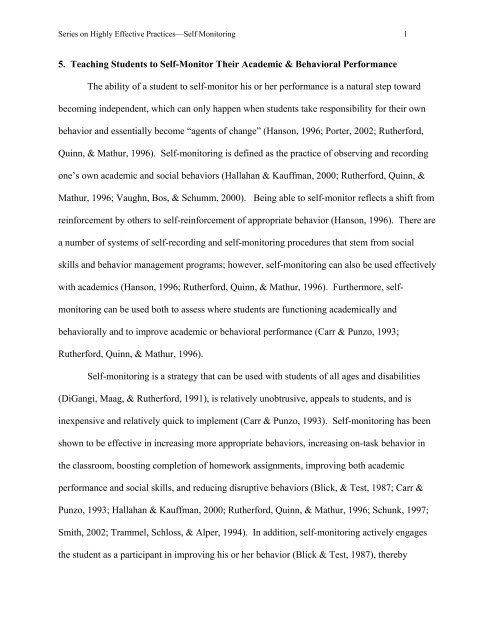

Series on Highly Effective Practices—<strong>Self</strong> Moni<strong>to</strong>ring 15. <strong>Teaching</strong> <strong>Students</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Self</strong>-Moni<strong>to</strong>r <strong>Their</strong> <strong>Academic</strong> & <strong>Behavioral</strong> PerformanceThe ability of a student <strong>to</strong> self-moni<strong>to</strong>r his or her performance is a natural step <strong>to</strong>wardbecoming independent, which can only happen when students take responsibility for their ownbehavior and essentially become “agents of change” (Hanson, 1996; Porter, 2002; Rutherford,Quinn, & Mathur, 1996). <strong>Self</strong>-moni<strong>to</strong>ring is defined as the practice of observing and recordingone’s own academic and social behaviors (Hallahan & Kauffman, 2000; Rutherford, Quinn, &Mathur, 1996; Vaughn, Bos, & Schumm, 2000). Being able <strong>to</strong> self-moni<strong>to</strong>r reflects a shift fromreinforcement by others <strong>to</strong> self-reinforcement of appropriate behavior (Hanson, 1996). There area number of systems of self-recording and self-moni<strong>to</strong>ring procedures that stem from socialskills and behavior management programs; however, self-moni<strong>to</strong>ring can also be used effectivelywith academics (Hanson, 1996; Rutherford, Quinn, & Mathur, 1996). Furthermore, selfmoni<strong>to</strong>ringcan be used both <strong>to</strong> assess where students are functioning academically andbehaviorally and <strong>to</strong> improve academic or behavioral performance (Carr & Punzo, 1993;Rutherford, Quinn, & Mathur, 1996).<strong>Self</strong>-moni<strong>to</strong>ring is a strategy that can be used with students of all ages and disabilities(DiGangi, Maag, & Rutherford, 1991), is relatively unobtrusive, appeals <strong>to</strong> students, and isinexpensive and relatively quick <strong>to</strong> implement (Carr & Punzo, 1993). <strong>Self</strong>-moni<strong>to</strong>ring has beenshown <strong>to</strong> be effective in increasing more appropriate behaviors, increasing on-task behavior inthe classroom, boosting completion of homework assignments, improving both academicperformance and social skills, and reducing disruptive behaviors (Blick, & Test, 1987; Carr &Punzo, 1993; Hallahan & Kauffman, 2000; Rutherford, Quinn, & Mathur, 1996; Schunk, 1997;Smith, 2002; Trammel, Schloss, & Alper, 1994). In addition, self-moni<strong>to</strong>ring actively engagesthe student as a participant in improving his or her behavior (Blick & Test, 1987), thereby

Series on Highly Effective Practices—<strong>Self</strong> Moni<strong>to</strong>ring 2increasing his or her investment in the process. Finally, self-moni<strong>to</strong>ring techniques is aneffective <strong>to</strong>ol for generalizing and maintaining skills over time, because students can performthem any time and in any setting without needing an adult <strong>to</strong> help them (Blick & Test, 1987;Rutherford, Quinn, & Mathur, 1996). However, students first need <strong>to</strong> be taught how <strong>to</strong> selfmoni<strong>to</strong>rtheir academic and social behaviors.To be successful self-moni<strong>to</strong>rs, students need <strong>to</strong> learn <strong>to</strong> keep track of what they aredoing and how they are thinking so they can adjust their behaviors and thoughts in order <strong>to</strong> meetgoals or complete tasks (Porter, 2002; Smith, 2002). The first step in teaching students <strong>to</strong>moni<strong>to</strong>r themselves is <strong>to</strong> select and clearly define a target behavior (Carr & Punzo, 1993;Stainback & Stainback, 1980; Vaughn, Bos, & Schumm, 2000). Next, a student or observerrecords instances of the behavior <strong>to</strong> provide evidence of the problem and its frequency (Carr &Punzo, 1993; Schunk, 1997; Vaughn, Bos, & Schumm, 2000). The next step is <strong>to</strong> set learningand performance goals and identify consequences for meeting or failing <strong>to</strong> meet their goals(Schunk, 1997; Vaughn, Bos, & Schumm, 2000). There is then a cognitive component <strong>to</strong> selfmoni<strong>to</strong>ringbehavior that requires students <strong>to</strong> talk themselves through a set of instructions (selftalk)for completing a task or <strong>to</strong> ask themselves a question or series of questions about theirfeelings or behaviors (Brophy, 1996; Kamps & Kay, 2002; Porter, 2002; Smith, 2002). If astudent is moni<strong>to</strong>ring his or her on-task behavior, for example, he or she may ask “Am I ontask?” when a timer goes off and tally the answer on a recording sheet. As the student learns <strong>to</strong>moni<strong>to</strong>r his or her performance on a regular basis, the timer is phased out (Blick & Test, 1987).<strong>Students</strong> can also be taught <strong>to</strong> ask themselves questions about their academic learning andperformance, such as asking, “How many math problems have I completed in the last 10minutes? How many are correct?” (Carr & Punzo, 1993). If the goal is <strong>to</strong> moni<strong>to</strong>r reading

Series on Highly Effective Practices—<strong>Self</strong> Moni<strong>to</strong>ring 3comprehension, a student might be taught <strong>to</strong> ask, “What am I studying this passage for? What isthe main idea of this paragraph?” (Wong, 1986). <strong>Students</strong> will need <strong>to</strong> practice repeatedly eachof these steps and then implement them in actual social or academic situations. These steps caneither be taught by a teacher (Schunk, 1997; Smith, 2002) or with the assistance of peers(Gilberts, 2000). <strong>Students</strong> must be taught <strong>to</strong> self-evaluate their success each day (Vaughn, Bos,& Schumm, 2000). The probability of the internalization of these skills increases if the studentparticipates in a structured and predictable school environment. Finally, the teacher should beprepared <strong>to</strong> periodically introduce a scaled-down version of the original instruction, if there is adecline in these skills.To make self-moni<strong>to</strong>ring most effective, strategies should be used constantly and overtlyat first and then faded <strong>to</strong> less frequent use and more subtle use across time (Stainback &Stainback, 1980). It is also important <strong>to</strong> ensure that students have learned the skills andbehaviors that teachers want them <strong>to</strong> perform as they are using the self-moni<strong>to</strong>ring strategies. Tohelp maintain and generalize positive behavioral changes, self-moni<strong>to</strong>ring should be combinedwith methods that allow students <strong>to</strong> evaluate themselves against their earlier performance and <strong>to</strong>reinforce themselves for their successes (Goldstein, Harootunian, & Conoley, 1994; Hallahan &Kauffman, 2000; Porter, 2002; Schunk, 1997; Smith, 2002; Stainback & Stainback, 1980;Vaughn, Bos, & Schumm, 2000). Cognitive strategies such as “self-talk” (e.g. “hey—good job”or “I knew I could do it”) are especially useful.Catherine Hoffman Kaser, M.A.

Series on Highly Effective Practices—<strong>Self</strong> Moni<strong>to</strong>ring 4References and Additional Sources of InformationBlick, D. W., & Test, D. W. (1987). Effects of self-recording on high-school students’ on-taskbehavior. Learning Disability Quarterly, 10(3), 203-213.Brophy, J. (1996). <strong>Teaching</strong> problem students. New York: The Guilford Press.Carr, S. C., & Punzo, R. P. (1993). The effects of self-moni<strong>to</strong>ring of academic accuracy andproductivity on the performance of students with behavioral disorders. BehaviorDisorders, 18(4), 241-50.DiGangi, S. A., Maag, J. W., & Rutherford, R. B. (1991). <strong>Self</strong>-graphing of on-task behavior:Enhancing the reactive effects of self-moni<strong>to</strong>ring of on-task behavior and academicperformance. Learning Disability Quarterly, 14(3), 221-230.Gilberts, G. H. (2000, March). The effects of peer-delivered self-moni<strong>to</strong>ring strategies on theparticipation of students with disabilities in general education classrooms. Paperpresented at Capitalizing on Leadership in Rural Special Education: Making a Differencefor Children and Families, Alexandria, VA.Goldstein, A. P., Harootunian, B., & Conoley, J. C. (1994). Student aggression: Prevention,management, and replacement training. New York: The Guildford Press.Hallahan, D. P., & Kauffman, J. M. (2000). Exceptional learners: Introduction <strong>to</strong> specialeducation (8 th ed.). Bos<strong>to</strong>n: Allyn and Bacon.Hanson, M. (1996). <strong>Self</strong>-management through self-moni<strong>to</strong>ring. In K. Jones & T. Charl<strong>to</strong>n(Eds.), Overcoming learning and behaviour difficulties: Partnership with pupils (pp.173-191). London: Routledge.Kamps, D. M., & Kay, P. (2002). Preventing problems through social skills instruction. In B.

Series on Highly Effective Practices—<strong>Self</strong> Moni<strong>to</strong>ring 5Algozzine, & P. Kay (Eds.), Preventing problem behaviors: A handbook of successfulprevention strategies (pp. 57-84). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.Porter, L. (2002). Cognitive skills. In L. Porter (Ed.), Educating young children with specialneeds (pp. 191-209). Crows Nest, Australia: Allen & Unwin.Rutherford, R. B., Quinn, M. M., & Mathur, S. R. (1996). Effective strategies for teachingappropriate behaviors <strong>to</strong> children with emotional/behavioral disorders. Res<strong>to</strong>n, VA:Council for Children with <strong>Behavioral</strong> Disorders.Schunk, D. H. (1997, March). <strong>Self</strong>-moni<strong>to</strong>ring as a motiva<strong>to</strong>r during instruction withelementary school students. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the AmericanEducational Research Association, Chicago, IL.Smith, S. W. (2002). Applying cognitive-behavioral techniques <strong>to</strong> social skills instruction.ERIC/OSEP digest. Arling<strong>to</strong>n, VA: ERIC Clearinghouse on Disabilities and GiftedEducation.Stainback, S., & Stainback, W. (1980). Educating children with severe maladaptive behaviors.New York: Grune & Strat<strong>to</strong>n.Trammel D. L., Schloss, P. T., & Alper, S. (1994). Using self-recording, evaluation, andgraphing <strong>to</strong> increase completion of homework assignments. Journal of LearningDisabilities, 27(2), 75-81.Vaughn, S., Bos, C. S., & Schumm, J. S. (2000). <strong>Teaching</strong> exceptional, diverse, and at-riskstudents in the general education classroom (2 nd ed.). Bos<strong>to</strong>n: Allyn and Bacon.Wong, B. Y. L. (1986). Instructional strategies for enhancing learning disabled students’reading comprehension and comprehension test performance. Canadian Journal forExceptional Children, 2(4), 128-132.