INDI LEISA - Leisa India

INDI LEISA - Leisa India

INDI LEISA - Leisa India

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

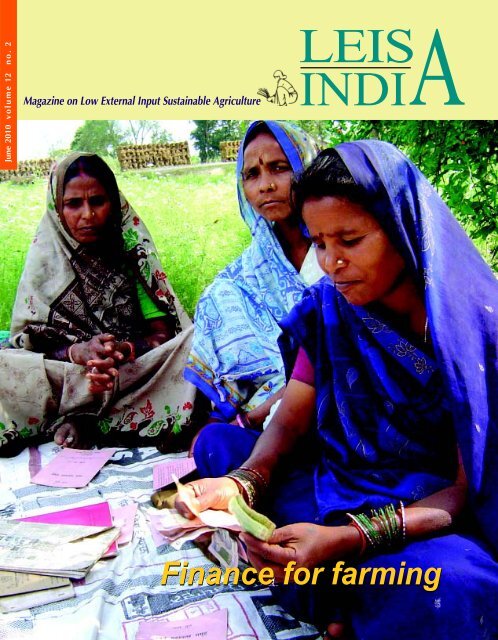

June 2010 volume 12 no. 2Magazine on Low External Input Sustainable Agriculture<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>INDI</strong>Finance for farming<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>INDI</strong>A • JUNE 20101

ALEIS<strong>INDI</strong>June 2010 Volume 12 no. 2<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>India</strong> is published quarterly by AMEFoundation in collaboration with ILEIAAddress : AME FoundationNo. 204, 100 Feet Ring Road,3rd Phase, Banashankari 2nd Block, 3rd Stage,Bangalore - 560 085, <strong>India</strong>Tel: +91-080- 2669 9512, +91-080- 2669 9522Fax: +91-080- 2669 9410E-mail: amebang@giasbg01.vsnl.net.in<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>India</strong>Chief Editor : K.V.S. PrasadManaging Editor : T.M. RadhaEDITORIAL TEAMThis issue has been compiled by T.M. Radha,K.V.S. Prasad and Poornima KandiADMINISTRATIONM. Shobha MaiyaSUBSCRIPTIONSContact: M. Shobha MaiyaDESIGN AND LAYOUTS Jayaraj, ChennaiPRINTINGNagaraj & Co. Pvt. Ltd., ChennaiCOVER PHOTOWomen farmers in Uttar Pradesh are adept inmanaging group accounts.Photo: S Jayaraj for GEAGThe AgriCultures NetworkILEIA is a member of the AgriCultures Network(http://www.leisa.info). Farming Matters ispublished quarterly by ILEIA. Eight organizationsof the AgriCultures Network that provideinformation on small-scale, sustainableagriculture worldwide, and publish are:<strong>LEISA</strong> Revista de Agroecología (Latin America),<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>India</strong> (in English), SALAM MajalahPertanian Berkelanjutan (Indonesia),Agridape (West Africa, in French),Agriculturas, Experiências emAgroecologia (Brazil),<strong>LEISA</strong> China (China) andKilimo Endelevu Africa (East Africa, in English).The editors have taken every care to ensurethat the contents of this magazine are as accurateas possible. The authors haveultimate responsibility, however, for thecontent of individual articles.The editors encourage readers to photocopyand circulate magazine articles.Dear ReadersFinancial Inclusion is the new buzz word being heard everywhere, meaning different thingsto different people – from a mere credit access to a range of financial services to the poor.Most often, farm credit is inherently associated with large farmers, under the assumptionthat only commercial agriculture needed finance. But the reality is, majority of small holdersalso need credit which is timely and inexpensive, to remain in farming and make a reasonableliving.A number of initiatives are being tried by formal as well as development agencies, usingdifferent models and methods with varying degrees of success. Also, there are a wide rangingissues and relevant questions - Is credit sufficient to promote sustainable livelihoods forsmall holders? Do farmer groups have a role to play in accessing credit? Are self help groupsbecoming an easy platform for reaching the credit targets by the government? Is sufficientinvestment being made in making these institutions sustainable? In this issue, we have includedexperiences which address some of these issues. Also, included are views of pioneers ofsome of these movements, and those making tremendous efforts even in mainstreaminstitutions. Hope you find them informative and inspirational.Some of our readers are giving their feedback using our new website. We are extremelypleased with their response. We look forward to many more visiting our website, givingfeedback, and also initiating discussion on <strong>LEISA</strong>. You can see more details about the websiteon page 22.We are also receiving a lot of encouragement and support for our language editions beingbrought out as special translated editions in Hindi, Kannada, Tamil, Telugu and Oriya. Theyare available on the website.Many of our readers are contributing voluntarily and we thank them for their support. Wewould like to inform you that the contributions made to <strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>India</strong> are exempted under80CC of Income Tax regulations. Kindly avail this opportunity and donate generously.The Editors<strong>LEISA</strong> is about Low-External-Input and Sustainable Agriculture. It is about the technicaland social options open to farmers who seek to improve productivity and income inan ecologically sound way. <strong>LEISA</strong> is about the optimal use of local resources andnatural processes and, if necessary, the safe and efficient use of external inputs. It isabout the empowerment of male and female farmers and the communities who seekto build their future on the bases of their own knowledge, skills, values, culture andinstitutions. <strong>LEISA</strong> is also about participatory methodologies to strengthen the capacityof farmers and other actors, to improve agriculture and adapt it to changing needs andconditions. <strong>LEISA</strong> seeks to combine indigenous and scientific knowledge and toinfluence policy formulation to create a conducive environment for its furtherdevelopment. <strong>LEISA</strong> is a concept, an approach and a political message.AME Foundation promotes sustainable livelihoods through combining indigenous knowledge and innovative technologies for Low-External-Input natural resource management. Towards this objective, AME Foundation works with small and marginal farmers in the Deccan Plateauregion by generating farming alternatives, enriching the knowledge base, training, linking development agencies and sharing experience.AMEF is working closely with interested groups of farmers in clusters of villages,to enable them to generate and adopt alternative farming practices. Theselocations with enhanced visibility are utilised as learning situations for practitionersand promoters of eco-farming systems, which includes NGOs and NGO networks.www.amefound.orgBoard of TrusteesDr. R. Dwarakinath, ChairmanDr. Vithal Rajan, MemberMr. S.L. Srinivas, TreasurerDr. M. Mahadevappa, MemberDr. N.K. Sanghi, MemberDr. Lalitha Iyer, MemberDr. N.G. Hegde, MemberDr. V.N. Salimath, MemberDr. T.M. Thiyagarajan, MemberILEIA - the Centre for Learning on sustainableagriculture and the secretariat of the globalAgriCultures network promotes exchange ofinformation for small-scale farmers in the Souththrough identifying promising technologies involvingno or only marginal external inputs, but building onlocal knowledge and traditional technologies andthe involvement of the farmers themselves indevelopment. Information about these technologiesis exchanged mainly through Farming Mattersmagazine (http://ileia.leisa.info/).2<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>INDI</strong>A • JUNE 2010

Southern RevivalS S JeevanWhile management of natural resources iscrucial, micro finance is a catalyst forachieving sustainable agriculture. Theexperience of HIH shows how microfinance has played a supportive role in theecological journey of a large number offarmers in Tamil Nadu.Linking small-scale farmers tocredit institutionsCh Ravinder Reddy, P Parthasarathy Rao , Ashok S Alur,A Rajashekar Reddy, Sanju Birajdhar, A Ashok Kumar,Belum VS Reddy and CLL GowdaImprovement of farmers livelihoods depends on the strength of theircoming together. Access to resources is influenced by the extent towhich farmers are organized and the institutional arrangementsavailable and finally the contextual social and political structure.Farmers’ organizations, therefore, would have a vital role to play inrural change.Financing small farmers – an innovativemethodologyL H ManjunathFarmers need credit for various reasons.But their inability to repay has been animportant reason for not being able toaccess timely credit. Pragathibandhu is aninnovative programme which makes thepoor bankable by diversifying incomesources and facilitating labour sharing.Community Biodiversity Management(CBM) Fund for sustainable rural financeShree Kumar Maharjan, Bhuwon Ratna Sthapit andPitambar ShresthaCommunity empowerment is adriving force to motivate ruralpeople for conservation efforts.Access to knowledge andfinancial resources are basicrequirements for the communityto translate their acquiredknowledge and skills intopractices that lead to their wellbeing. The CBM fund is used asa mechanism to achieve the twin goal of biodiversity conservationand livelihood improvements in Western Tarai regions of Nepal.9132335CONTENTSVol. 12 no. 2, June 2010Including Selections from International Edition4 Editorial6 Marginal and small farmers require freedom andoptions, not financial inclusionAloysius Prakash Fernandez9 Southern RevivalJeevan11 Microfinance for livelihood improvementUtkarsh Ghate13 Linking small-scale farmers to credit institutionsCh Ravinder Reddy, P Parthasarathy Rao , Ashok S Alur,A Rajashekar Reddy, Sanju Birajdhar, A Ashok Kumar,Belum VS Reddy and CLL Gowda17 Self regulation of SHGs and SHG federationsS Rama Lakshmi20 Strength lies in building empowered communitiesInterview with Dr Venkatesh Tagat23 Financing small farmers – an innovative methodologyL H Manjunath25 Financing sustainable farming through strong localinstitutionsD Ranganatha Babu27 Thinking beyond creditJan Douwe van der Ploeg30 Bank credits – boon or bane?Prasanth31 Arecanut chain – adding value with lowerenvironment impactS 3 idf32 The Narayana Reddy ColumnTimely credit is the key33 Sources34 New Books35 Community Biodiversity Management (CBM) fund forsustainable rural financeShree Kumar Maharjan, Bhuwon Ratna Sthapit andPitambar Shrestha<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>INDI</strong>A • JUNE 20103

EditorialFinance for farming<strong>India</strong>’s rural poor are overwhelmingly dependent on agricultureas their primary source of income; the majority are marginalor small farmers, and the poorest households are landless. Ruralhouseholds typically depend on two types of incomes: farm incomewhich is seasonal and part-time wage labor which is highlyirregular. Farmers need money for various purposes which typicallyfalls under consumption needs and production needs. Also amajority of rural households have to deal with unexpectedexpenditures which they are forced to finance either from cash athome, or through informal loans from family, friends, ormoneylenders.The need for multiple financial servicesCredit is not the only financial service needed by small holders.They need to save and also want to cover themselves against risksthrough insurance. The poor need a wide range of financial services,from small advances to tide over consumption needs to loans forinvestment for productive purposes and long term saving that helpthem manage life cycle needs.<strong>India</strong> has a range of rural financial service providers, includingthe formal sector financial institutions at one end of the spectrum,informal providers (mostly moneylenders) at the other end of thespectrum, and between these two extremes, a number of semiformal/microfinanceproviders. The formal sector financialinstitutions which include Commercial banks, Regional rural banks,Cooperatives and Insurance Companies account for almost allinstitutional loans to rural areas. However, the formal loans arethe least preferred by farmers owing to longer processing timeand untimeliness of credit. Studies indicate that it takes, on anaverage, 33 weeks for a loan to be approved by a commercialbank. Bankers too find it high risk and high cost proposition toserve the rural poor. The transactions costs of rural lending in<strong>India</strong> are high, mainly due to the small loan size, high frequencyof transactions in rural finance, large geographical spread,heterogeneity of borrowers, and widespread illiteracy. Notsurprisingly, informal borrowing despite the high interest rates isvery important for the poorest, who are the most deprived of formalfinance.Improving credit access - the micro finance modelsAs access to financial services reduces vulnerability and helps poorpeople increase their income, improving this access has becomean important part of many development initiatives. In light of theinefficiencies that characterize <strong>India</strong>’s rural finance markets andthe relative lack of success of the formal rural finance institutionsin delivering timely finance to the poor, NGOs, financialinstitutions, and government have made efforts, in partnership, todevelop new financial inclusion approaches to service the financialneeds of the rural poor. These approaches – or “microfinance”programs – have been designed to overcome some of the risks andcosts associated with formal financing.One approach to microfinance that has gained prominence in recentyears is the self help group (SHG)-bank linkage program, pioneeredby a few NGOs such as MYRADA in Karnataka and PRADAN inRajasthan with strong support from NABARD. SHG-bank linkageinvolves organizing the poor, usually 15-20 women, into self-helpgroups (SHGs), inculcating in the group the habit of saving, linkingthe group to a bank and rotating the saved and borrowed fundsthrough lending within the group. The SHGs thus save, borrowand repay collectively.Over the last 10 years, the SHG-linkage model has become thedominant mode of micro finance in <strong>India</strong>, and the model has beensuccessful in encouraging significant savings and high repaymentrates. The number of SHGs linked to banks has increased fromjust 500 in the early 1990s, to over 69,53,000 by 2010. The SHGbanklinkage program today reaches around 97 million poorhouseholds.The other model is Micro Finance Institutions (MFI), which has areach of around 1 million clients. This sector has emerged to doleout small loans to poor people unable to access conventionallending mechanisms. In <strong>India</strong>, in the year 2010, the microfinancesector after growing into huge proportions, (supposedly 25000crore or 41 million euro industry) is facing a crisis. Presently, thesector is facing criticism for its rate of interest, the purpose forwhich it has lent, and extending multiple loans, ignoring the abilitiesto repay. Also it is felt that the micro finance institutions, bytargeting individuals has weakened the existing social cohesion.(Venkatesh Tagat, p. 20)Moving beyond creditIn an impact assessment study carried out by BASIX six yearsafter inception, brought out that the micro credit programmeaddressed the issue of livelihoods only peripherally. The studyfound that only 52% percent of the three-year plus microcreditcustomers reported an increase in income, 23% reported no changewhile another 25% actually reported a decline. The reasons statedwere (i) un-managed risk (ii) low productivity in crop cultivationand livestock rearing and (iii) inability to get good prices from theinput and output markets. It is therefore necessary to broaden theparadigm from microcredit to Livelihood Finance.“May be its time to suggest that the focus on credit for ‘agriculture’should shift to ‘credit to families’ living in rural areas”, saysAlsoyius Fernandez, former Director of MYRADA, who pioneeredthe SHG movement. Declining size of holdings, increasing risksgenerated by shifting to high cost inputs, declining quality of soilsand fluctuating market prices has made it difficult for small holdersto increase farm productivity using credit. With this changed focus,farming families especially small and marginal farmers in drylandareas can increase and diversify the income generating activitiesin their portfolio of livelihood activities and continue to be creditworthy (A. Fernandez, p. 6).4<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>INDI</strong>A • MARCH JUNE 2010 2010

Management of natural resources is crucial in enabling betterreturns from land. Micro finance is only a catalyst in achievingsustainable agriculture. Therefore focus should be on building upnatural resources using credit and not just dump credit withouthelping communities on how to use it productively. For instance,Hand in Hand besides providing access to credit has organizedworkshops and field training for farmers to take up organic farmingand guided them to practice sustainable agriculture. Today, manyfarmers in Thiruvannamalai district have switched over to organicpaddy cultivation and are reaping benefits.(Jeevan, p. 9). Similarlythe fishermen federation of Orissa used credit as a tool to conservethe marine biodiversity (Utkarsh, p. 11).Some innovative mechanisms have been developed by thedevelopment agencies to help farmers access as well as strengthentheir repayment capacities. The Pragathinidhi, an innovativefinancing development fund promoted by SKDRDP in Karnataka(Manjunath, p. 23), encourages farmers to take up several farmrelated activities and enterprises which increases their incomesource. Similar is the Community Biodiversity Management Fundwhich is used as a mechanism to achieve the twin goal ofbiodiversity conservation and livelihood improvements in WesternTarai regions of Nepal (Shree Kumar Maharjan et.al., p. 35).Also credit needs to be supplemented with supportive services.The support services like veterinary care, fodder and water are notavailable often because the poor do not have access to theseresources. Strong local institutions like the Social Affinity Groups(SAG) can help overcome even this hurdle by organised lobbying(A. Fernandez, p. 6).It is assumed that credit can automatically translate into successfulmicro-enterprises. Micro credit is a necessary but not a sufficientcondition for micro enterprise promotion, says Vijay Mahajan ofBASIX. Other inputs are required, such as identification oflivelihood opportunities, selection and motivation of the microentrepreneurs,business and technical training, establishing ofmarket linkages for inputs and outputs, common infrastructure andsome times regulatory approvals. In the absence of these,microcredit by itself, works only for a limited set of activities –small farming, livestock rearing and petty trading, and even thosewhere market linkages are in place.Strong organizations - Self regulation and managementAccess to resources is influenced by the extent to which farmersare organized and the institutional arrangements available andfinally the contextual social and political structure. Farmers’associations are viable platforms to bring farmers together, buildtheir capacities and enable them to gain access to resources, credit,inputs and markets. This would directly help them in cuttinguncertainty and transaction costs, and empower them to makechoices relating to feasibility, productivity and profitability of farmenterprises. It would also help to pinpoint asymmetric access rules,and allow farmers to raise their voice and have it heard. Farmers’organizations, therefore, have a vital role to play in access to ruralfinance.Handholding by an external agency like an NGO is imminent inbuilding the capacities of group members in using creditproductively, thus making the groups strong and sustainable.For instance, the dynamics of thousands of SHGs nurtured by Handin Hand over the years has been such that most farmers have beenable to pay back the amount and also improved their livelihoodstandards. It is also in the process of evolving a marketingmechanism to make products viable in different markets.Simultaneously, the organization has undertaken severalconfidence-building measures to motivate poor farmers(Jeevan, p. 9).However, it is also important that these groups and their federationsat a higher level, become independent in all aspects and take fullownership. Future of SHGs and their federations lies in memberstaking full responsibility for the entire structure – the SHG andtheir federation. This means that the facilitating agencies shouldminimise their role, and enable representatives of the movementto take full ownership, especially for the agenda of promotingincreased member-control and ownership. Hence promotinginstitution needs to focus on bottom up approach and ensure thatthe self regulation of SHGs and their federations, should bedesigned, implemented and managed by the women themselves(Rama Lakshmi, p. 17).SustainabilityWhile some of these programs have been more successful thanothers, their limited outreach, scalability and financial sustainabilityremain matters of concern. SHGs have become a means to quicklyreach targets in the government programmes. The emphasis ontargets without adequate attention to nurturing and strengtheningthe SHGs could lead to a general deterioration in the quality ofgroups promoted, threatening the longer term credibility andviability of the entire program.Groups can become financially sustainable if their resources arebuilt on internal savings rather than depending on external fundingand subsidies. Big loans from formal sources could be riskyespecially for small and marginal farmers group when their meansare limited. This may push them into a new spiral of debts andsuicides as is evident with the experience of MFIs in several statesin <strong>India</strong>.Making systems and procedures simpler can help increase accessto formal sources of finance. Also, better credit information anduse of ICTs like mobile phone banking, Kisan credit cards andbiometric ATMs can go a long way in reducing the transactioncosts, ultimately reaching out to larger number of small farmers.References:<strong>INDI</strong>A: Scaling-up Access to Finance for <strong>India</strong>’s Rural Poor;September 6, 2004; Finance And Private Sector Development Unit;South Asia Region, The World Bank.NABARD, Status of Micro Finance in <strong>India</strong> - 2010.•<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>INDI</strong>A • • MARCH JUNE 20105

Marginal and small farmersrequire freedomand options,not financial inclusionAloysius Prakash FernandezSmall farmers need credit and other supporting services fordiverse activities which comprise a family’s livelihood strategy.Self Help Affinity Groups (SAGs) are the most appropriateinstitutions which provide the necessary space, resources andskills required by a poor family to develop a livelihood strategy.Marginal and small farmers especially in drylandareas have been the “target” of financial inclusion policyand practice since 1904 when the first CooperativeSociety was registered in Gadag taluk in Karnataka.. Since thenseveral major steps have been taken to expand the network offinancial institutions in order to “include” marginal and smallfarmers in to the country’s financial sector; the major ones beingthe nationalisation of banks in 1969; the launching of NationalBank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) in 1975;launching of Regional Rural Banks (RRB) in 1975-76 andintroduction of the SHG-Bank Linkage program in 1992. Severalmicro finance schemes managed by these institutions targetingthe small and marginal farmers were launched, starting with theIntegrated Agricultural Development Program (IADP) in 1960-67 to the SGSY in 2000. These institutions, especially the RRBsand SHGs and the various schemes provided micro finance (MF)as well as subsidies, no frills accounts, kisan credit cards etc.The word “Micro Finance” was not used till the for-Profit NBFIs(Non-Banking Financial Institutions) gained momentum after1999. They targeted “inclusion” of the poor not into the formalfinancial system of the country but more into the more efficientand extractive neo liberal globalised financial sector withconsequences which have unfurled in the past few months. Thefeatures which characterise the neo liberal model are: investmentfrom private and venture capitalist, quick growth, high profits,high costs (interest and salaries), IPOs and quick exits. Littleconcern is given to value creation and building skills of clients touse capital effectively; hence the impact on poverty mitigation isminimal.In spite of these initiatives of Government to include the smalland marginal farmers into the country’s financial sector, studiesshow that the number of small loans provided by financialinstitutions for agriculture is declining steadily over the years. Thecredit-deposit indicates an outflow of credit from the rural areas.The percentage of rural savings is less than urban and overall thegrowth in the agricultural sector has languished behind the servicesand manufacturing sectors. Though the government has takenseveral measures to increase credit flow to the rural sector (whichis interpreted and restricted to agriculture) the demand does notseem to be improving.What is a SAG?There are a few features which constitute the DNA of an SHG:i) The process starts by using PRA methods like wealthranking so that people can identify the poor in the village;ii) The identified poor are given a short description aboutan SAG and requested to form groups;iii) The members self select themselves – the basis is affinityamong members which is based on relations of mutualtrust and support and cuts across caste and religions andactivities;iv) The groups are given institutional capacity building - atleast 12 modules;v) Alongside they start regular meetings and savings;vi) They start a group common fund in which their savingsgo and later the loans from Banks – there is only onegroup account;vii) They start taking loans from the common fund;viii) After 6 months the SHG Bank Linkage program kicks in –one loan to the entire group allowing the group to decideon individual loans. Different from all so called JLGswhere the Bank decides on each individual loan.6<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>INDI</strong>A • JUNE 2010

Box 1: Two cases of members of Self Help Affinity group Chikkajajur, Holalkere Taluk, Chitradurga Dt.,Karnataka(1) Kausar Banu *(2) Nagarathnamma1996 1,000 Trading 1997 2,000 Education1996 3,000 Trading 1997 500 Education1997 5,000 Trading 1997 2,000 Education1997 500 Education 1998 4,000 LPG for home use1997 5,000 Medical expenses 1998 5,000 Education1997 300 Medical expenses 1998 5,000 Vehicle loan repayment1998 4,000 Trading 1999 7,100 House repair1998 5,000 Trading 1999 8,000 Vehicle loan repayment1998 5,000 Trading 2000 8,000 Vehicle loan repayment1999 5,000 Trading 2000 15,000 Vehicle loan repayment1999 12,000 Trading 2000 325 To purchase SHG uniform2000 25,000 To release house mortgage 2001 18,000 Business2000 325 To purchase SHG uniform 2002 30,000 Vehicle repairs2001 2,000 Education 2003 28,000 Vehicle loan repayment2002 40,000 House purchase 2003 8,325 Sewing machine (SGSY)2003 325 Household expenses 2004 2,300 LPG for home use2003 8325 Sewing machine (SGSY) 2005 40,000 Vehicle repairs2003 50,000 Agriculture land purchase 2005 1000 Jewellery loan2004 2300 LPG for home use 2006 2,000 Jewellery loan2005 58,000 To release agriculture land 2007 62,000 Tempo purchase and goldfrom mortgage2005 6,000 House repair 2008 22,820 Tempo repair and insurance2005 1,000 Jewellery loan 2009 11,000 Tempo repair2006 2,000 Jewellery loan 2010 40,500 House repair and gold2007 2,000 Gold2008 53,820 Cycle shop business and gold2009 Nil -2010 500 GoldTotal 4,59,390 Total 3, 22,870Maybe its time to suggest that the focus on credit for “agriculture”should shift to “credit to families” living in rural areas. The majorreason for this shift is the declining size of holdings, increasingrisks generated by shifting to high cost inputs, declining quality ofsoils and fluctuating market prices. As a result, farming familiesespecially small and marginal farmers in dryland areas haveincreased the number of income generating activities in theirportfolio of livelihood activities. They now have livelihoodstrategies which comprise several activities. This has resulted inthe need for credit for a variety of purposes including several nonagricultural ones which are not provided by the regular schemeswhich focus on agriculture. There are other reasons like thestandardised credit packages and asset units (3-5 cows, 20 plus1 sheep) which may be considered “viable” but which the familycannot manage, fixed repayment schedule (monthly /weekly) whenrural incomes are lumpy and the same interest rates for all types ofloans.One reason for Government’s policy to remain restricted to “creditfor agriculture” is the data from surveys like the NSSO whichshow that about 60%-70% of the population are “farmers”. Thequestion asked is: “During the part year have you done agriculturefor 30 days?” If the answer is “yes” the person is listed as a “farmer”even though he does other activities for the rest of the year. Besides,other members of the family also take up activities which are oftennot related to agriculture. This needs to be changed. Loans need tobe given to the rural family, not for agriculture alone.SAGs – the most appropriate institutionsThe position taken in this article is that the Self Help AffinityGroups (SAGs) are the most appropriate institutions to providethe space, resources and skills required by a poor family to developa livelihood strategy which enables it rise and remain abovepoverty. The SAGs provided space to invest in many diverselivelihood activities which comprise a family’s livelihood strategy,they customise the size of loans and interest rates and cope withirregular cash flows of the family when repayment to Banks/MFIsis difficult since Banks/MFIs have a fixed schedule ofrepayment.<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>INDI</strong>A • JUNE 20107

Let us give two profiles of the livelihood strategies of two membersof Self Help Affinity groups in Myrada which bring out the diversityin livelihood strategies (See Box 1).In case of Kausar Banu, the major traditional activity of the family’slivelihood strategy was trading; their land had been mortgagedbefore the SAG was formed for capital to do trading; later severalloans were taken from the SAG for trading. As income from tradingincreased, the family reclaimed the mortgaged land and purchasedland and dug a well. Income generating activities increased to three:i) trading ii) cycle shop iii) agriculture and long term investmenteducation. They took only one small loan for household expenses.Finally, loans were taken for gold and jewellery- a sign that theyare now confident. The total investment was Rs 4.5 lakhs.In case of Nagarathamma, the family owned dry land but decidednot to invest in agriculture. Instead it opted to invest in a preownedTempo. The SAG provided capital for maintenance.Alongside, they gave priority to education. She also purchased gold.The total investment in family livelihood strategy -Rs. 3.2 lakhs.The SAG strategy gave the family the space and freedom to decidein what activities to invest, how much to invest and when. Thesewere not imposed as standardised product.The criticism therefore that SAGs provide loans only forconsumption is wrong. Further the data which gives the averageloan size as Rs 4000 is misleading. The members of SAGs take anumber of loans of different sizes as per their requirement. Thetotal amount must be taken into consideration. Schemes like theIRDP and SGSY provide one or two loans amounting to approxRs 50,000; this is insufficient. Even if the lending institutions haveestimated that the asset is “viable” ( 3-5 cows or 20 plus 1 sheep),the support services like veterinary care, fodder and water are notavailable often because the poor do not have access to theseresources. The SAG helps to overcome even this hurdle byorganised lobbying; SAGs and their federations have been able tochange oppressive power relations. There was no subsidy attached;but the family only took loans when it was sure that it has all thesupport services required to make the loan productive and to earnan income.The second reason why SAGs are appropriate is that they do nothave fixed or standardised packages or products related to creditor assets. The different purposes of loans and of loans sizes takenby the two families brings this out clearly.The third reason is that the repayment rates of a member in anSAG can be adjusted when unexpected problems arise. Yet theSAG is able to repay the Bank/MFI loans in time because of i)cash flow from other members and ii) savings and interest whichaccrues to the groups common fund. Has this eroded the groupscommon fund? There is no evidence that it has. The total commonfund has increased year after year.When the SAGs first emerged in Myrada’s projects in 1984-85 asa result of the large Cooperative Societies breaking down thepractice was to apply differential interest rates. The rates for loanstaken for health and food were very low (2%-5% per annum) whilethe rates for trading were high (15% to 25%). This was very similarto one of the features of sharia or Islamic Banking where the incometo the investor is a share in profits. Unfortunately, the demand forstandardisation imposed by software changed this practice.Aloysius Prakash FernandezFormer Director,MyradaE-mail: Fernandez@myrada.org•Themes for<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>India</strong>Vol. 13 No. 1, March 2011The role of a new generation of farmersAs agreed by the UN General Assembly, the year starting on12 August 2010 has been proclaimed as the InternationalYear of Youth. Twenty-five years after the first InternationalYouth Year was celebrated, the world has seen many changes.What impact do these changes have on the younger membersof the 400 million farmer families all over the world? TheMarch 2011 issue of Farming Matters will look at the specificrole which youngsters play in family farming.Youngsters form the largest population group in manycountries, and their numbers and relative size keep ongrowing. What is the capacity of agriculture and small-scalefamily farming for attracting and “absorbing” them, providingthem with work, income and a decent livelihood? Recentdecades have seen a strong trend of migration. With moreyoung people moving to the cities, what is the future of familyfarming?We want to look not only at the roles and responsibilities ofyoung people, but also at the contributions that they canmake. Youngsters are known to be much more interested in(and knowledgeable about) mass media tools andcommunication devices than the older generation. Whatbenefits can the information highway bring to farming? Weare also interested in youngsters’ own perspectives on farming,the specific difficulties they face and the steps needed tosolve them.Please send your articles to the Editor atleisaindia@yahoo.co.inDeadline for submission of articles - 1 st March, 20118<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>INDI</strong>A • JUNE 2010

Southern RevivalJeevanWhile management of natural resources is crucial,micro finance is a catalyst for achievingsustainable agriculture. The experience of HIHshows how micro finance has played a supportiverole in the ecological journey of a large numberof farmers in Tamil Nadu.In the past 100 years or so, the role of the State has been criticalto the changes in the ecological chain in <strong>India</strong>. While rapidurbanization has cast its shadow over traditional water sourcesand farm lands, the role of the local communities in managingnatural resources has decreased. Simultaneously, there has been agrowing dependence on surface water and groundwater, and lesson rainwater and floodwaters. This has not only led to a decline ingroundwater tables and agricultural yields, but led to more areasbecoming highly degraded throwing millions of poor farm peopleout of jobs. Finding ways to harvest and store rain water in rural<strong>India</strong> as well as to involve communities in the management ofnatural resources has become the challenge.The Natural Resource Management Programme (NRM) of Handin Hand was launched in October 2006 with the major objectiveof reviving a degraded environment and involving local people inits management. The way to do this was to forge partnerships withgovernment agencies and local organizations to fund projects thatwould not only protect natural resources and revive agriculturalactivities, but more importantly, by undertaking the restoration ofwatersheds, so that the poorest of the poor in rural <strong>India</strong> wouldgain employment and improve their living standards. This wouldcheck ecological imbalances, promote clean living and greenfarming and create avenues for new marketing mechanisms.Today, nine micro watersheds have been taken up for regenerationtill now in three districts of Tamil Nadu – Kancheepuram,Thiruvannamalai and Cuddalore – and Chamrajanagar district inKarnataka, directly benefiting over 2,500 poor people, andgenerating nearly 10,473 man days of work. The NRM activitiesform a part of the Environment Pillar of Hand in Hand – one ofthe five Pillars of the organization. The other pillars are Self-HelpGroups, Microfinance, Health and Citizen Centers Pillars.Hand in Hand is working towards the goal of creating 1.3 millionjobs to eliminate extreme poverty and strengthen livelihoods amongimpoverished communities.Adimoolam, who has a tiny agricultural land in Arapedu,Kancheepuram, Tamil Nadu, has benefitted from the integratedwatershed management approaches of Hand in Hand. The smallloose rock check dams and stone outlets have enabled the retentionand proper flow of water in his farms. These structures have alsohelped increase soil fertility because of the retention of the moisturein the soil and also checked the velocity of water during heavyrains. “Hand in Hand initiatives have helped recharge wells inthe area. We are able to store water almost throughout the yearand yields too have gone up,” says Adimoolam. Today, thousandsof poor people such as Adimoolam as well as those who wereinvolved in the watershed restoration activities have reason tosmile.Now, other states too want to be part of the NRM programme. Forinstance, in Karnataka in collaboration with the VivekanandaGirijana Kalyana Kendra (VGKK), a local NGO, watershedprogramme, and, WADI, an orchard development programme fortribals in Chamrajanagar district are being implemented.Government programmes have often been designed to cover poorpopulations, but the delivery and scale have not been enough; andin many cases insufficient, not scaled-up enough to cover the vastimpoverished populations. The NRM programme attempts toaddress the gaps that exist in the agricultural and agro-basedsectors.Methods and ApproachThe Arapedu watershed comprising four villages and three hamletscovers an area of 1,092 hectares. It was planned at a cost of<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>INDI</strong>A • JUNE 20109

Adimoolam on his farmRs 96 lakh, with financial assistance of Rs 85 lakh from NABARD,and the remaining amount was mobilized from communitycontribution. The watershed activities are based on traditional waterharvesting technologies pioneered by people for centuries andlocalized to suit the environment and its inhabitants. For instance,water absorption trenches were constructed along the foothills ofthe mountains to hold and regulate the flow of water from thehills. And digging ponds, contour trenches and supply channelsenabled and augmented the water flow.The mammoth task involved over 3,200 members who are part ofthe water associations in four villages, and they take collectivedecisions to implement the watershed activities. WatershedAssociations were formed and they elected members to theWatershed Committee, who are involved in the restoration andmanagement of watershed activities. The Watershed Committeeworks in close coordination with different stakeholders includingthe panchayats – village-level democratic institutions. “Thewatershed initiatives have had a positive impact on the village,”says R Rajendran, vice-president of Arapedu village. Crop yieldshave doubled in the area, he adds.Financing NRM activitiesThe organization is also making innovation as the key to widenthe scope of its activities. For instance, Hand in Hand has started arevolving fund and gives loans to farmer groups or Self-Help Group(SHG) members so that they take up agricultural or agro-basedactivity. The dynamics of thousands of SHGs nurtured by Hand inHand over the years has been such that most farmers have beenable to pay back the amount and also improved their livelihoodstandards. The organization has also started another revolving fundwith the help of NABARD, wherein landless farmers becomeeligible for loans to start any livelihood-based activity.Trench-cum-bund with plantationswitched over to organic paddy cultivation. “Earlier, our inputcost was high because of the use of pesticides and fertilizers. Butafter switching over to organic farming, we use less expensive(natural) inputs. This has increased the net profit,” says Jayaraman.Evolving a marketing mechanism to make such products viable indifferent markets is in the process. Simultaneously, severalconfidence-building measures to motivate poor farmers wereundertaken. It took a six acre degraded land about 80 km fromKancheepuram on a five-year lease in December 2008. Here, ithas constructed two ponds in the area and leveled the fields to dohorticulture plantation.In the adjoining villages it has adopted different approaches in thereclamation of land. In Murukkeri for instance – a tiny hamletlocated in Thiruvannamalai district – local people got involved inthe clearing of Prosopis juliflora, a wild weed and used machinesin leveling the land and promoted agricultural activities. InVilangadu village in the same district, this strategy has reclaimedover 100 acres of degraded lands. The NRM activities of Hand inHand connect us to the ecological journey ahead of us, one of theways to realize the potential of our poor rich planet.S S JeevanDirector - Communications Hand in Hand,No. 12/26, 3 rd Floor,Coats Villa/Southern FoundationCoats Road, T. Nagar,Chennai - 600017Website: www.hihseed.org•But the microfinance component is only a way to provide economicmobility. The NRM programme has organized workshops and fieldtraining for farmers to take up organic farming and guided themto practice sustainable agriculture. Today, many farmers such asJayaraman in Murukeri village in Thiruvannamalai district have10<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>INDI</strong>A • JUNE 2010

Microfinance forlivelihoodimprovementPhoto: S JayarajUtkarsh GhateMicrofinance can be profitable and viable if used as a capitalto promote micro enterprise. Samudram fishermen federationin Orissa used micro finance as an investment tool to achievebiodiversity conservation, income generation and women’sempowerment.Climate Change has hit the coastal ecosystem, the worst,with unprecedented decline in coral reefs and loss of fishyield, shift in their occurrence zone and migration routes.This has endangered not only many species like the Olive RidleyTurtle but also the livelihoods of fishermen who are poor, illiterateand lack assets, dependent entirely on coastal biodiversity.Moreover, the recent Coastal Management Zone (CMZ) regulationhas impoverished them further by giving freeway to the industrialoccupations of the coast. Industrial and urban effluents havereduced fish catch. Also, aquaculture ponds along the coast ownedby private parties exclude communities and pollute the coastfurther. Addressing the issue of pollution calls for shift to organicmethods of cultivation and also huge capital investments. Withthe land ownership resting with the rich, the poor have no optionto improve their incomes but to add value for better markets.Samudram fisherwomen federation in Orissa used microfinanceas an investment tool to achieve this.The InitiativeFishermen in the coastal regions of Orissa face problems commonto many other coastal sites such as reducing fish catch and quality,exploitation and cheating by the traders, apathy of the governmentetc. Their fishing rights have been further constrained owing tothe conservation initiative taken up on this coast to protect OliveRidley Turtle (ORT), an endangered species.With fishing rights severely constrained around three ORT nestingsites, many fisher families were prevented from fishing and had totake up other occupations or migrate. Few even committed suicidedue to indebtedness, hunger and loss of dignity after harassmentby wildlife sanctuary officials who confiscated their boats and nets,the only means of their livelihood. This triggered the formation ofSamudram Fisherwomen Federation.Orissa Marine Resource Conservation Consortium (OMRCC)emerged out of protest against this exploitation. OMRCC iscoordinated by the NGO United Artists Association (UAA) andaided by larger NGOs like Greenpeace. They decided to protectfishing rights of fisherwomen and enhance their income by valueaddition.Samudram activities include–a) Collective fish purchase.b) Hygienic drying/ processing.c) Collective sales to bulk buyers and retailers.d) Obtain bank loan to groups/ women members for doingbusiness.e) Conservation campaign, against pollution and over fishing,through CBO, NGO’s and media.f) Conservation efforts like artificial reef, ORT watch & ward,rescue, beach cleaning (of plastic/garbage).g) Alternative income generation programs (crab tattering,poultry, duckers).UAA assists Samudram in getting technology inputs for valueaddition, conservation, credit linkages and access to distantmarkets. Both the artificial reef and value addition technology areprovided by OMRCC partners. Artificial reef technology isprovided by CMFRI (Coastal Marine Fisheries Research Institute)of Govt. of <strong>India</strong>. It was funded by Ford Foundation through aproject of CCD, an OMRCC partner. Technologies were first triedand tested at Pulicat lake coastal ecosystem near Chennai by NGOPLANT, a CCD partner, in 2006-08. Since it was found successful,Samudram replicated it in 2009.<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>INDI</strong>A • JUNE 201011

Other partners in OMRCC like Greenpeace and ATREE (AshokaTrust for Research in Ecology and Environment, an NGO fromBangalore), Dakshin Foundation etc., assist Samudram incampaigns against upcoming port at Dhamra Special EconomicZones (for industries that may pollute the coast), foreign shippingvessels coastal intrusion etc.The management of Samudram federation rests with the womenleaders of the group, elected to the federation body. They reviewprogress periodically and decide action. Each group is assignedspecific responsibilities. The women groups purchase fish in coastalauctions from fishermen union (who are spouses sometimes) anddry them in a hygienic manner. Income from collective sales goesto the federation which is then distributed among the members.Financial documentation is well maintained at the federation level.SustainabilitySamudram is partly self sustainable. It can do local collectivemarketing of dry fish besides fresh fish on its own. But to seekdistant market access in <strong>India</strong> and abroad for dry fish and othervalue added products, it needs external support from UAA. It alsoneeds venture capital or donor grants to start these ventures thatmay incur initial losses in the first 2-3 years. Then, bank loan canfuel its growth and sustenance.So far, Samudram financed its activities by itself (30%), throughgrants from UAA (30%) and loans (30%). However, due to theirgrowing business character, bank loans will be sought. Grant willbe availed only for the welfare of the disabled, old, malnourishedetc. However, Samudram may still need to finance about 15% ofits budget by grants for another 2-3 years on training groups,providing documentation material, business development tools andservices, exposure visits and building linkage with banks andgovernment schemes.ImpactsHygienic drying methods have enhanced product price by about15%, increased fisher women income by 5-10% and has enhancedconsumer satisfaction. Other technologies like picking appears tobe promising to raise incomes through high product price. But,full benefits are yet to be realized by the majority of the communitydue to limited productivity and market access achieved so far.About 1,000 women earned about 15% extra income i.e. Rs. 500(five hundred) extra in their total fish sales of Rs. 3,000 each lastyear. This implies Rs. 0.5 million of total benefits. Another 5,000had marginal benefit of 5% extra income by aggregation, totallingRs. 0.75 million. The total benefit is around Rs. 1.25 million for2,500 women who are not yet Samudram members. Thus, there isalso a multiplier effect. About 2,500 women also got bank creditof Rs. 15 to 20 thousand each totalling, Rs. 5 million. About 60%repayment is on schedule.Environmental protection has ensured decent fish breeding andcatch. This is evident from sustained income despite decliningcatch. Rising number of turtle nests and eggs each year indicatesthis. Conservation campaign has succeeded in reducing industrialpollution in all the 3 sites. The fight against polluting industriesalong the coast and protest against increased trawling has kept thecoast safe and clean despite mounting pressures. Reconsiderationby the government on its SEZ policy is a huge achievement forclean environment.Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) is another area where Samudramand OMRCC had some success. The government of Orissa startedproviding compensation (livelihood) allowance to the fishermen’scooperatives in monsoon which is declared as no fishing period,to ensure breeding. Similarly, cheap credit, basic amenities likedrinking water, sanitation, housing, electricity are gradually beingavailed by the fishermen families.Women leadership has been nurtured. Ms. Chittama, SamudramChairperson, an illiterate woman, became a role model. Nationalmagazines published features on her dynamism in addressing theissues of poverty and vulnerability of her community. She alsoreceived the UN Equator award for biodiversity conservation andpoverty alleviation. Other women leaders like Ms. Devaki haveparticipated actively in many state and national level campaignsand workshops.Miles to goEven after five years since Samudram’s inception and a decade ofstruggle by OMRCC, the problematic situation continues to persist.Some problems are solved while new ones have emerged. Marketaccess problem is solved partly by the value addition. But industrialencroachment on the coast is growing, now aided by thegovernment policy such as SEZ.Samudram has been able to benefit only one thousand fisherwomenso far, through enterprise development. Samudram has to reachabout ten thousand families at the 3 ORT nesting sites who needthis type of help. Thus, much more needs to be done.Utkarsh GhateCovenant Centre for Development (CCD)North <strong>India</strong> office,2/25, Padmanabhpur,Durg City,Chattisgarh,<strong>India</strong> 491001E-mail:ccdnorth@gmail.comWebsite: www.ccd.org.in•12<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>INDI</strong>A • JUNE 2010

Linking small-scale farmers to creditinstitutionsCh Ravinder Reddy, P Parthasarathy Rao ,Ashok S Alur, A Rajashekar Reddy,Sanju Birajdhar, A Ashok Kumar,Belum VS Reddy and CLL GowdaPhoto: IDFImprovement in farmers livelihoods depends on the strengthof their coming together. Access to resources is influencedby the extent to which farmers are organized and theinstitutional arrangements available and finally thecontextual social and political structure. Farmers’organizations, therefore, would have a vital role to play inrural change.The demand for poultry feed is increasing in <strong>India</strong> due tofast growth (by 15-20%) of poultry sector, while the usualenergy source in the poultry feed, maize’s growth rate islimited to only 2-4% annually. This is because poultry feedmanufacturers are using sorghum and pearl millet in poultry feedformulations to some extent whenever there is a shortage of maizesupply. To improve the farm income and livelihoods of smallscalesorghum and pearl millet farmers in SAT regions of <strong>India</strong>, acollaborative project was launched by Common Fund forCommodities (CFC), The Netherlands, ICRISAT and FAO.The CFC-ICRISAT-FAO project titled ‘Enhanced utilization ofsorghum and pearl millet grains in poultry feed industry to improvelivelihoods of small-scale farmers in Asia’ aimed at mobilizinggroups of small-scale sorghum and pearl millet farmers in orderto improve the crop productivity and income by providing supportin terms of improved inputs, better information services, creditlinkages and post harvest operations. This paper exclusively dealswith the credit linkages component of the project.ApproachStrategic interventions were jointly made by ICRISAT and theconsortium partners along with ICRISAT to train the farmers, buildtheir technical capabilities and provide them further withinformation on improved crop production practices to enhancethe yields per unit area. Institutional linkages with various actorsin supply and market chains helped the farmers in reducing theoverall production and post harvest handling costs. However, it isa well-known phenomenon that the farmers in the absence ofsufficient funds dump their produce in the local markets or withmiddle men. They fall victim to the brokers and traders who takeadvantage of this distress sale position of the small-scale farmersand procure the commodities at low prices, un-remunerative tothe farmers.Thus, the importance of credit becomes very evident not only atthe time when the farmers have stored their produce to meet theirregular expenses but also when they are growing crop they needto buy various inputs like improved cultivar seeds, fertilizers, andpesticides.The baseline survey conducted before commencement of theproject was helpful in getting realistic picture of the constraintsfaced by the farmers prior to the project with regard to institutionalcredit. The major sources of credit prevalent in the villages wereprivate money lenders (individuals), local input dealers and grainmerchants, private finance companies, local agriculturecooperatives and public sector banks.The baseline survey results indicated that secure and equitableaccess to resources and markets was key to improving the incomesof small-scale farmers. This was the foremost action needed toaddress poverty issues and promote the overall development offarm families. Therefore, all the interventions in the project wereaimed to address these constraints.Organising farmer groupsOn the basis of interactions with farmers and the project team’sprevious experiences, it was felt that farmers’ associations wereviable platforms to bring farmers together, build their capacitiesand enable them to gain access to resources, credit, inputs andmarkets. This would directly help them in reducing uncertaintyand transaction costs, and empower them to make choices relatingto feasibility, productivity and profitability of farm enterprises.It would also help to pinpoint asymmetric access rules, and allowfarmers to raise their voice and have it heard.One of the major interventions of the project was to help increasefarm productivity. Farmers were organsied into groups as it was<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>INDI</strong>A • JUNE 201013

ealised as the best mode of reaching them with improvedtechnologies. Linkages with institutions were fostered. This projectalso identified a few areas for immediate collaboration indeveloping a common understanding of the issues of technologydevelopment as they relate to the needs of the rural poor: forinstance, sharing of experience between scientists and farmers,higher levels of coordination for ongoing field operations andsupport for initiative-linked activity, focusing on the developmentof farmers’ learning platforms.Access to institutional creditCredit is required usually for the period of crop production (sowingto harvest), mainly for purchase of quality seeds, fertilizers,pesticides and farm equipment/equipment hire charges; paymentof labour charges for sowing and harvest. The baseline surveyconducted in for this project clearly indicated that farmers alsoneed cash after the harvest for storing produce as well as for meetingimmediate family requirements. In the absence of institutionalcredit facilities, they sell their produce in the local markets or tomiddlemen soon after harvest at non- remunerative prices. Thus,post-production credit needs were given equal importance whiledesigning credit requirement strategies.In the first year of project execution, various possibilities of linkingbanks with the farmers were explored at the local (cluster) level.The branch managers of various banks located near to the clustervillages were briefed about the concept of the project. The privatebanks expressed that the amount of loan availed was very low,maintaining farmers records is cumbersome and it would not beeconomical for bank to cover up their costs. Moreover, for thewarehouses, there are collateral management charges that are tobe borne by the borrower and it will be very high and would raisethe cost of finance per farmer exorbitantly.In addition, most of the branch managers of nationalized banks atcluster level were reluctant to provide loans on the stored producein the godowns constructed under the project in the absence ofclear cut instructions or guidelines to finance private warehouses.They had clear guidelines for financing against produce stored inpublic warehouses such as the warehouses owned by CentralWarehouse Corporation (CWC) and State Warehouse Corporation(SWC). They however suggested that if they were giveninstructions from the top management to provide loans for CFCfunded godowns, they would have no procedural problems inproviding the loans.Top-down approachFrom the experience in the first year it was thought that in thesecond year a “top-down approach” would be best whereconsortium team members first talk to the top level departmentalheads of various nationalized banks namely State Bank ofHyderabad (SBH) and State Bank of <strong>India</strong> (SBI). Following this,a series of discussions with the different levels of departmentalmanagers of these banks was carried out by explaining projectobjectives and activities. Method of project approach wheremarketing linkages were established with the poultry feed industryfor buy-back of the produce of small-scale farmers gave themProject overviewThe project addressed various constraints identified through abaseline survey. Important interventions included introductionof farmer preferred best cultivars of sorghum and pearl millet,establishing sustainable linkages for long-term input supply,constitution of 5 farmers associations (one for each cluster) andbuilding their capacities to carry forward the interventions onlong term basis. Demonstrations on the farmer’s fields helpedthe farmers to test the performance of new cultivars, integratednutrient and crop management technologies that enhancedgrain yields from 19 to 111 percent in sorghum and 36 to 120percent in pearl millet; and fodder yields by around 25 percent.Farmer’s field days, expert’s visits, exposure trips and learningevents facilitated sharing of the knowledge and experiencesbetween the scientific community and the farmers. The ruralstorage structures constructed under the project helped thefarmers adopt safe and scientific storage of the bulked produceand thus avoid distress sale. Linking of farmers with alternativeend users (food, poultry feed, liquor industries) has beenachieved through a series of Farmers-Buyers dialogues. Lessonsacross the clusters indicate that multi-stakeholder initiativescan bring in synergistic and long lasting positive impacts onrural poverty reduction. Other important learnings includedproviding sufficient start-up time for planning; building strongcoherence and trust among partners; role clarity; capacitybuilding; adopting process-oriented systems.confidence and assurance on loan repayment. Both the banks werepositive on providing credit facilities to farmers associations bothin Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra states and passed on positivemessages to the concerned cluster level branch managers.It was decided that for Andhra Pradesh, the State Bank of <strong>India</strong>and for Maharashtra, the State Bank of Hyderabad would be invitedto initiate the process of providing loans to the farmers. This wasto be given both against their stored produce in the current seasonConstraints in Farm Credit• Non-availability of timely credit• High rates of interest when borrowed from private sources• Lengthy and complex procedures involved in availing farmcredit from banks• Complex credit-processing procedures• Time taken to process loan applications• Middlemen facilitating loans on a commission basis• Loan periods are usually shortThese constraints are related to• Policies of the government, which govern the overall outlayof finance for the farm sector• Legal and regulatory framework of farm credit agencies• Institutional diversity of credit/finance organizations providingcredit to farmers• Formalities and procedures of credit disbursement14<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>INDI</strong>A • JUNE 2010

and issue Kissan Credit Cards to the eligiblefarmers in the next year rainy (Kharif) season2006 to meet their crop productionexpenditure. With this decision two jointmeetings were organized at ICRISAT thatformed the major guiding activity withregard to making the model operational,Consortium Partnerseffective and establishing sustainablelinkages between the farmers and thebankers.Facilitating joint meetingsSeveral meetings were organized at thevillage and cluster levels to highlight theimportance of credit linkages with public sector banks. Thesemeetings also served to set at rest any apprehensions the farmersmay have had about sharing information with field-level workers.These meetings became platforms upon which farmers shared theircredit problems. To further gain the farmers’ confidence, publicsector bankers were invited to join these meetings to explain loanprocedures. Applications were filled and loan procedures madesimple for the farmers.The project partners and bank officials fixed convenient dates forthe farmers to visit the bank to discuss matters pertaining to loans.This was helpful in building confidence in the farmers. This practicehas become popular because farmers get undivided attention frombankers on these days.A joint meeting was held at ICRISAT with the participation ofvarious project partners, representatives from ICRISAT and alsofarmers from the clusters and farmers association office bears andwith the divisional and local heads of the Banks with the followingagenda.1. Finalizing the procedures for linking farmers’ associations(Udityal, Balanagar mandal, and Palavai, Maldakal mandal ofMahabubnagar district, Andhra Pradesh) with State Bank of <strong>India</strong>(SBI) for agricultural credit. Similarly joint meetings wereconducted in Anjanpur and Rohatwadi clusters in Beed districtand Koke cluster in Parbhani district of Maharashtra state.2. Issuing Kissan credit cards to project farmers.3. Finalizing the procedures for providing short-term credit toproject farmers against stored agricultural produce (sorghum andpearl millet) for the produce.A number of points emerged out of these discussions, the mainitem being that the bank would simplify the application proceduresand processing time to finance the project farmers based on certainessential conditions being met according to guidelines set by thebank administration. The concerned bank official will visit thevillage once in a week or fortnight and scrutinize the applications.The farmers association secretary will process all applications ofproject farmers with minimum documents sets, prior to the visitof bank officials and submit to the bank a set of 20 applicationsper group. This facility will avoid all the farmers visiting the bankto prove their identity and present their case for loan.Fig.1 The linkages developed in the projectInput linkage (credit,seeds, fertilizers etc.)Training on improved cropproduction practicesSmall-scale farmersBanks/ financial InstitutionsCredit linkageHigh grainand fodderyieldGrain storage( ware house)(Poultryfarmersand feedindustry)Enhancedutilization infeedA number of other points also emerged in this meeting. The bankersadvocated bundling the two products (KCC and warehouse loans)into a single product called ‘Cyclic Credit’ to be implemented nextyear and organization of farmers into groups as it wouldsignificantly reduce their transaction costs. The requirements ofthe short-term loans based on warehouse receipts are:• The farmers’ committee to have the capacity of maintainingthe required records such as Stock accounting register and otherbooks required at the warehouse• Identity of the farmer by the association - The association wouldmake arrangements to issue a numbered photo identificationcard to its member farmers indicating their name, address, landholdings and other details• Committee to operate and maintain the godowns• Committee to authorize signatories for issuing the warehousereceipt to the farmers who stock their produce.• Signing of a MoU with the bank for not releasing the stock tillthe bank loan is cleared and receipt is returned.• Scientific storage support to be sought for the safe and scientificstorage of grains by consortium institutions• Godown insurance and produce insurance to be sought againstany eventualitiesDuring farmer-banker interaction meetings at the village level,senior bankers provided information regarding various farm creditschemes, including short and medium-term loans. Project partnerswere advised to help the banks in identifying the farmers who wouldbe eligible for the loans. The size of loan amount was based on thesize of the farmers’ land holding and credit requirement. Thedocumentation for obtaining a credit card was also made simple.ImpactProject interventions has increased the participation of small-scalefarmers in credit linkages. They have availed more loan amountfrom other sources of finance with less effort, low interest rateand low processing fee. The impact study assessed farmer’sperceptions of benefits accrued to them from different componentsof the project (Table 1). About 83% of them said the crop productioncomponent held the most benefiting to them followed by formationof farmers association (76%). Bulking (61%) and credit linkages(56%) and bulk marketing (54%) were other components that were<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>INDI</strong>A • JUNE 201015

ClusterTable 1. Farmers feedback on project componentsPercent benefits gained by project farmers from village initiativesCrop Farmers Bulking and Bulk Credit Remarksproduction association storage marketing linkagesAndhra Pradesh1.Palavai 88 75 72 71 722. Uditiyal 82 86 78 71 78Maharashtra1. Koak 70 47 49 42 372. Anjanpur 92 93 61 55 573. Rohatwadi 85 82 47 31 40Average 83.4 76.6 61.4 54 56.8On an average 75% of projectfarmers benefited by creditlinkages in AP clustersOn an average 45% of projectfarmers benefited by creditlinkages in Maharashtra clusterscited as beneficial by the respondents. On an average, 75% ofproject farmers benefited by credit linkages in Andhra Pradeshand 45% farmers in Maharashtra cluster villages.Establishment of credit linkages targeted at small and marginalfarmers drew their credit preferences away from informal sourcesto formal sources with low interest charges. A majority ofparticipants in the project borrowed loans from formal sources.Around 75 percent farm families got benefited by credit linkagesin Andhra Pradesh and 45 percent in Maharashtra clusters, at lowinterest. Majority of the farmers were interested in linking withbanks rather than cooperatives and private money lenders as theinterest rates and processing fee was lower. Only about 10% ofthe project farmers revealed that they still depend on money lenders.The interventions undertaken by the project succeeded in makingthe farmers’ voice heard by finance institutions. The joint dialoguebetween farmers and financial institutions brought abouttremendous changes in the mindsets on either side. The farmerswere able to provide inputs to the bankers in the design of loanproducts for the farm sector. This mutual understanding of prioritiesand constraints had an effective impact on loan decisions. Forinstance, banks modified several of their administrative proceduresfor processing loan applications. They also gave priority to projectfarmers.Evidently, improvement of farmers livelihoods depends on thestrength of their coming together. Access to resources is influencedby the extent to which farmers are organized and the institutionalarrangements available and finally the contextual social andpolitical structure. Farmers’ organizations, therefore, would havea vital role to play in rural change. This study is one classicalexample in that direction.Ch Ravinder ReddyScientist (Technology Exchange)ICRISAT, Patancheru – 502324,Andhra Pradesh, <strong>India</strong>E-mail: c.reddy@cgiar.org•Food Security E-learning CoursesYou can now join the over 50,000 people who havetaken the food security e-learning courses.The courses were developed by the EC-FAO FoodSecurity for Information Decision MakingProgramme, The “EC/FAO Programme on LinkingInformation and Decision Making to Improve FoodSecurity,” is based at the Food and AgricultureOrganization of the United Nations (FAO)andfunded by the European Union’s “Food SecurityThematic Programme (FSTP)”. Its overall aim is toimprove the quantity and quality of food securityinformation and analysis and promote its use indecision making.The Learning Center offers self-paced e-learningcourses on a wide range of Food Security relatedtopics. The courses have been designed anddeveloped by international experts to supportcapacity building and on-the-job training at nationaland local food security information systems andnetworks.Courses also include materials for face-to-face(F2F) training to be used in traditional classroomand workshops activities. The face-to-face trainingmaterials are also available separatelyYou can take courses online, download them onyour PC, or request a CD-Rom that will be sent toyou free of charge. For details, visitwww.foodsec.org16<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>INDI</strong>A • JUNE 2010

Self regulation of SHGsand SHG federationsS Rama LakshmiSHG and their federations have become a movement in<strong>India</strong>. To sustain the benefits emerging from thismovement, it is important that they become independentin all aspects and take full ownership. This means that thefacilitating agencies should minimise their role,withdrawing gradually. Self regulation of SHGs and theirfederations, designed, implemented and managed by thewomen themselves will ensure this process.The slow pace of rural development in <strong>India</strong> has beenattributed to lack of production assets and credit. To addressthis issue, the Government of <strong>India</strong> took major policymeasures like the nationalization of private banks in 1969, theexpansion of rural branch network, priority sector lending and theintroduction of Regional Rural Banks in 1975. Also large amountsof donor funding substantially increased outreach to better-offfarmers. Yet, all this failed to reach the vast numbers of landlesspeople, agricultural labourers, illiterate women and microentrepreneurs.In the 1980s, policy makers took notice and worked withdevelopment organizations and bankers to discuss the possibilityof promoting SHGs. Banks which had found it difficult to lend tomeet their priority sector lending obligations, suddenly found, inthe SHGs, an amenable opportunity to meet those obligations, andprofitably. On the basis of an assessment, NABARD initiatedmainstreaming of SHG banking. With a small beginning as a PilotProgramme launched by NABARD by linking 255 SHGs withbanks in 1992, the programme has reached 69.5 lakh saving-linkedSHGs and 48.5 lakh credit-linked SHGs covering about 9.7 crorehouseholds under the programme. By the 1990s, SHGs wereviewed by state governments and NGOs to be more than just afinancial intermediation but as a common interest group, workingon other concerns as well. The agenda of SHGs included social,political and livelihood issues as well.The support of livelihoods is increasingly being seen as animportant area related to microfinance. Indeed, the term oflivelihood finance has been coined and is en vogue at leadingNGOs. SHGs provided credit from their own fund to memberswho were engaged in farming activities. Some SHGs introducedthe strategy of converting the grants provided to the watersheddevelopment institutions for watershed activities into loans fortreatment on members’ lands. The SHGs also lobbied withWatershed Management Institutions to give the landless the rightto harvest fodder from the protected areas (private lands lyingfallow, common lands). This strategy also helped to convertneglected lands into regenerated parks which increased biomassand played a more effective role in managing soil erosion but alsohelped to provide a livelihood base to landless by accessing fodderand the landless were able to purchase cattle with loans from SHGs.These types of interventions improved the quality of land and therewas significant diversification of crops.SHG Federations and promotion of livelihoodsNetworking of SHGs was inspired by the felt need of the SHGsunable to deal with issues beyond their reach. The small size ofSHGs leads to a low generation of internal funds, which hinderstheir ability to meet the financial needs of the members from theirown savings or to leverage funds from banks. Their ability tonegotiate with higher level institutions and to gain bargaining poweris limited. This is one of the reasons for informal SHG networkingbeing initiated. SHG federations have been promoted by NGOsand the Government since the mid 1990s to address the issues ofensuring quality while up-scaling, ensuring that promotion costsare low, and creating sustainable institutions. These federationsoffer different types of services - social, financial and livelihoodservices. In many cases, the SHG federations in <strong>India</strong> offer a rangeof services and can be termed as multi-purpose federations.The need for livelihood support is critical to SHGs developmentas livelihoods are typically financed by the loans that membersreceive from the SHG. In order to make SHGs and their federationsmore sustainable, promoting agencies have invested a lot incapacity building, and in making corpus and bank funds available<strong>LEISA</strong> <strong>INDI</strong>A • JUNE 201017