See Preview - Cordillera Studies Center - UP Baguio

See Preview - Cordillera Studies Center - UP Baguio

See Preview - Cordillera Studies Center - UP Baguio

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

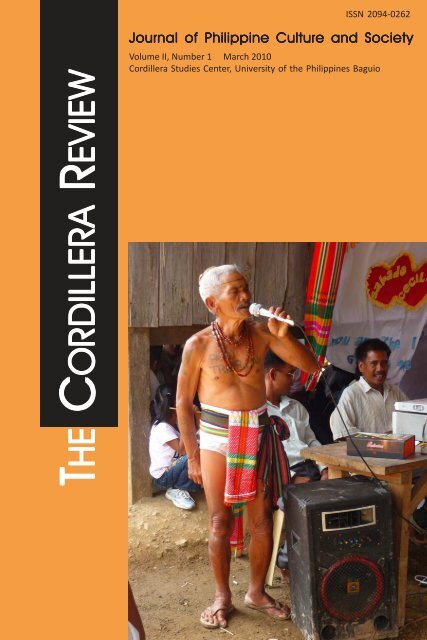

ISSN 2094-0262THECORDILLERAREVIEWJournal of Philippine Culture and SocietyVolume II, Number 1 March 2010<strong>Cordillera</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> <strong>Center</strong>, University of the Philippines <strong>Baguio</strong>

THEHE CORDILLERAREVIEWJournal of Philippine Culture and SocietyVolume 2, Number 1 March 2010ContentsJULES DE RAEDTTHE BUNTUK ORIGIN MYTHExplorations in Buaya MythologyForeword / 3I. Introduction / 7An Exercise in Myth AnalysisMyth Collecting: Its ProblemsReview of LiteratureII. The Setting / 21The Ethnographic BackgroundThe Physical Setting: The Buntuk SceneIII. The Syncretic Myth / 29Four SamplesThe Talanganay MythThe Kabunyan-Patubog MythThe Two Myths ComparedIV. The Talanganay Myth Analyzed / 49The Creation of Man and His FoodThe First SacrificeHuman NatureGod, Man and BeastThe First Sexual EncountersSiblings, Spouses and ParamoursHousehold, Political Ties, and FriendshipIncest is DivineThe Test of AlternativesDivine Romance and Female InadequacyDivine Romance and Male Brutality

The Buntuk Origin Myth 3ForewordThis special issue of The <strong>Cordillera</strong> Review presents the posthumouspublication of a work on Kalinga mythology written by Jules De Raedt,former professor of anthropology at the University of the Philippines<strong>Baguio</strong>, who passed away in December 2004, after a lingering illness.Although Prof. De Raedt worked intermittently on the manuscript duringthose years when he was no longer in the best of health, we can easilysurmise from the manuscript that this project began to take shape at amuch earlier time, when the author embarked on a long and sustainedreflection on <strong>Cordillera</strong> culture and society after doing field work inKalinga in the 1960s.What could warrant the publication of this old work at this time?The answer lies in what it could contribute to the advance of scholarshipon local folklore. Almost four decades have passed since E. ArsenioManuel, one of the founding fathers of Philippine <strong>Studies</strong>, first tooknote of the woeful state of folklore studies in the Philippines. Surveyingthe theses and dissertations submitted by Filipino students to graduateschools all over the country, Manuel decried the substandard work thatoften passed for folklore scholarship in the Philippines. Most of theseworks, according to Manuel, betrayed an appalling ignorance of propermethodologies in the collection and documentation of folklore, and alsofailed to come up with theoretically informed analysis of their data. Adecade after making that verdict, he wrote that “we have not yet actuallypassed the collecting stage in folklore studies.”With a few outstanding exceptions, not much has changed sinceManuel made these pronouncements. De Raedt himself writes in theopening section of his work: “The study of Philippine mythology is stillon a level comparable to the collection of bows and arrows in earlyethnology. Whatever work has been done beyond collecting, i.e.,methodologically acceptable collecting, has been in terms of generalclassifications and attempts at interpretation inspired by the Propp-Dundes tradition. A reflection of later anthropological advances is hardlydetectable.” More recently, in the blurb that he wrote for a book onPhilippine indigenous oral traditions (Herminia Meñez Coben’s VerbalArts in Philippine Indigenous Communities), anthropology professorEufracio C. Abaya indirectly gave an assessment of the contemporarystate of Philippine folklore scholarship when he said that “Byinterpreting quite successfully themes and subthemes of verbal art andits performance/production in specific ethnographic, ecological andhistorical contexts, this work distinguishes itself from other studies in

4 The <strong>Cordillera</strong> ReviewPhilippine folklore that have not gone beyond the classificatory/thematic analysis.” Abaya’s statement, which points to the lack ofanalytical rigor in Philippine folklore studies, repeats the earlierjudgments by Manuel and De Raedt.In “The Buntuk Origin Myth,” the author presents what he calls“an exercise in myth analysis.” The primary perspective isanthropological, as to be expected, given the author’s disciplinarytraining. De Raedt’s earliest foray into myth analysis may be found in“Myth and Ritual: A Relational Study of Buaya Mythology, Ritual andCosmology,” the doctoral dissertation he submitted to the University ofChicago in 1969. The second chapter of the dissertation presents theauthor’s earliest reflections on the subject of the Buntuk origin myth,along with what is perhaps the first extended discussion of the Kalingaepic form known as gasumbi. This work reflects the influence of, amongothers, two eminent anthropologists, Victor Turner and Terence Turner,who were mentors and members of the dissertation committee. The twoTurners continue to figure in De Raedt’s later musings on the Buntukorigin myth, but the expanded nature of this later reflection can be feltin the inclusion of new concepts and methodologies derived fromstructuralist anthropology (primarily Claude Levi-Strauss),psychoanalytic theory, and the study of symbols (e.g., the work ofClifford Geertz, whose classic study of the Balinese cockfight isprominently cited here). The rather eclectic approach is explained bythe author’s intention to present “as complete an analysis of two relatedKalinga creation myths” as his knowledge and analytical skills wouldallow. Such an analysis must perforce comprehend “the socialstructural, cultural/semantic and ecological contexts” of the myths.We thus have in the present work an analysis whose incisivenessis seldom encountered in Philippine folklore study. De Raedt’s attemptsto tease out various meanings from the vocabulary of the myth and itsmetaphors through semantic analysis and references to the ethnographiccontext make for a nuanced analysis of the narratives. However, despitethe comprehensiveness of the analysis, it must be pointed out that whatwe have here is actually an incomplete work.The manuscript on which the following text of “The Buntuk OriginMyth” was based is an imperfect photocopy of the manuscript given tothe editor when the author was still alive. The original manuscript,which could no longer be located, was a combination of typewrittenand computer-encoded pages, with extensive corrections and additionsin the author’s handwriting. The photoduplication was, in many parts,unsatisfactory, and some illegible sections of the manuscript had to bedeciphered or even reconstructed, using internal evidence. In those partswhere nothing could be done with the typographic problem, the editorcould only resort to omission. In every instance, the omitted part isindicated by a bracketed ellipsis. Another problem had to do with the

The Buntuk Origin Myth 5way the manuscript pages were put together. Many sections consistingof loose pages were unpaginated and some sequencing issues had to beresolved. Still another problem was, in two instances (“The TalanganayMyth” and “The Two Myths Compared” in the third chapter), theexistence of two versions of a particular section. Which of the twoversions represents the author’s final intention? This too had to beresolved.The greater problem is perhaps the problem of incompleteness.Two pages are missing in the copy of the manuscript used for editing.In one case (“Approaches from Psychology: Symbols” in the Review ofLiterature section), the missing page was reconstructed by using anearlier version of the review which appeared as “Myth Analysis: Truthin Myth” in the Saint Louis University Research Journal (1982). The othermissing section, which could not in any way be reconstructed, is againindicated by a bracketed ellipsis.The manuscript is incomplete for another reason. First, although ithas parenthetical citations, it has no reference list. The list wasreconstructed by referring to the author’s available works (where manyof the cited sources are also used) and through library and Internetsearch. Second, the present work ends with the author’s discussion of“Divine Romance and Male Brutality” (section 3 of Chapter 4) but weknow that the work does not properly end here because the author left apreliminary table of contents which shows that after this is a discussionof “God, Man and Heroes,” followed by a fourth section on “The NewCosmos” under which the author is supposed to have discussed “DivineWithdrawal,” “Mediums and Headhunters,” and “Sacrifice: TheSynthesis.” Then, too, there is supposed to be a last chapter where thesummary and conclusions are given.These sections, originally thought to be missing, were nevercompleted by the author, according to Lourdes Gimenez who assistedProf. De Raedt in the preparation of the manuscript before he died. Onecan get an intimation of some of the things possibly discussed in theseuncompleted sections by referring to the author’s Chicago dissertation,particularly Chapter 2 (“Mythology,” where he discusses, in additionto the Buntuk origin myth, the Kalinga epics, ritual myths, and thepolymorphous figure of Kabunian), Chapter 3 (“Man and His Cosmos,”on Kalinga cosmogony, notions of the supernatural, the headhuntingcomplex, and the role of the medium in native rites), and Chapter 4(“Animal Sacrifice,” where De Raedt discusses the various stages of theanitu rites; a revised version of this chapter was published as amonograph, Kalinga Sacrifice, by the <strong>Cordillera</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> <strong>Center</strong> in 1989.)However, when referring to the dissertation, one has to keep in mindthat the material in this early work was subsequently re-thought andre-interpreted as De Raedt considered new perspectives and brought innew material drawn from later investigations in Kalinga.

6 The <strong>Cordillera</strong> ReviewWhile it is regrettable that the present text of De Raedt’s work onthe Buntuk origin myth is incomplete, we maintain that even in thisform it represents a thorough and penetrating discussion of Kalingamyth and can stand by itself. It is a distinct contribution to <strong>Cordillera</strong><strong>Studies</strong> and offers a model of myth analysis that is backed up both bytheory and intimate knowledge of the culture and society from whichthe myth originated.In addition to the editing and reconstruction work discussed inthe preceding paragraphs, there are a few editorial corrections and theusual silent emendation of spelling inconsistencies, typographicalerrors, and the like. Editorial judgments are seldom faultless. The editortakes full responsibility for mistakes and inaccuracies arising from thepreparation of the final copy on which the following text was based,with the hope that none of these lapses constitutes an egregious mistake.We would like to thank Dr. Carol Brady and Ms. Gimenez forcooperating with us and for providing us important information, andDr. June Prill-Brett for reviewing the manuscript. We also thank thestaff of the <strong>Cordillera</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> <strong>Center</strong>—Alicia Follosco, Raulita Gutierrez,Ruel Lestino, and Joey Rualo—for assistance in various stages of thisproject. Needless to say, the greater debt is to the author himself, Prof.Jules De Raedt, whose friendship and trust I acknowledge with fondaffection.DELFIN TOLENTINO, JR.Editor

The Buntuk Origin Myth 7I IntroductionThis monograph is an attempt at an anthropological analysis of aPhilippine myth. It is a pioneering and exploratory work, and does notpretend to be the final word on the subject.Myths are succinct statements by a culture about its core concepts.Myths are symbolic statements, held in the hands of individualnarrators, and as such potentially told in as many versions of what therecorder-analyst (it is hard to see how the two could be different persons)must translate into universally comprehensible statements about theculture that produced these myths.The study of Philippine mythology is still on a level comparable tothe collection of bows and arrows in early ethnology. Whatever workhas been done beyond collecting, i.e., methodologically acceptablecollecting, has been in terms of general classifications and attempts atinterpretation inspired by the Propp-Dundes tradition. A reflection oflater anthropological advances is hardly detectable.1. An Exercise in Myth AnalysisThis study is an exercise in myth analysis. Such an enterprise is notonly of great interest because myths are—to use a mining metaphor—instances of high grade cultural material; it is also a challenge becausethe extraction of the precious contents from this ore can be donesuccessfully only with the greatest effort and care. As in the treatment ofcertain types of ore, a good deal of guesswork is involved in the analysisof myths.Like other instances of human behavior—and mineral ore, for thatmatter—the empirical form in which myths present themselves is not ofa nature that immediately reveals its full meaning or content. To beginwith, the text rarely consists of a neat, well rendered sequence of editedsentences, uniformly rendered by the average adult of the community.Rather, as rendered empirically, the myth is never narrated the sameway, not even by the same individual. In each narration there may beomissions and changes in the order of events, aside from the presenceof standard variants which by now we have come to accept as part ofthe nature of things. In the case of the myth that is the subject of thisstudy, we have the further difficulty of having to deal with variousattempts at syncretisms of two or more myths by the different narrators.

8 The <strong>Cordillera</strong> ReviewOnce the syncretic problem is resolved, the real issue is one ofmethodology. Myths, like other cultural material, are “imaginative worksbuilt out of social materials” (Geertz 1973, 449). The purpose of thisstudy is to give as complete an analysis of two related northern Kalingacreation myths, together, in their syncretic form, referred to as the“Buntuk origin myth,” as my knowledge of the life experiences of thepeople who tell the myths, and my skills at analysis, permit. This meansthat I will draw on the social structural, cultural/semantic and ecologicalcontexts of the myth, as well as psychoanalytic theory. The myth seemsto demand a certain structuralist approach which I will follow whereverit may (or may not) lead. My basic interests lie, however, with what isgenerally called the semiotic approach.The main symbol in the Buntuk origin myth is sexual intercourse.This study shall look at the meanings of those sexual relations whichcarry great significance in local life. What the myth seems to be all aboutis a statement about human nature, both ontological and moral, as theBuaya and their neighbors experience it and conceive of it. The workpresented here is, therefore, an instance of cultural interpretation, or thecomprehensive interpretation—looking into all suggested relationshipswith the rest of culture—of a single empirical piece of cultural material,a myth.Whatever theoretical import the present study may have is almostpurely accidental. The steps taken will reveal my own level ofunderstanding of what myth analysis is or should be all about. Of course,what one does oneself, and believes to be right, he loves to see confirmedin the practice of others. My own preferences should reveal themselvesin the section on review of literature and in various parts of the study. Iwill neither defend nor refute explicitly certain approaches. Rather, letthis analysis speak for itself.2. Myth Collecting: Its ProblemsThe texts from which the myth is reconstructed are potentially asnumerous as the adult and pre-adult members of the communities whosemyth it is. There are no special occasions on which the myth is told; itcan be related and heard by all at any time. From an early age, all knowabout the myth, but many will direct the collector to a few individualswho are generally considered to know the myth better. Theseindividuals, it is generally agreed, can narrate the myth in more detailand with a greater degree of authority (based on acceptance) than others.This respect for certain narrators is partly based on the relative confidencewith which they narrate the myth, the relative completeness of thenarration, the quality of their prose, the age of the narrator, and otherqualities of these persons that make their versions more authoritative

The Buntuk Origin Myth 9and satisfying to the listeners. Consequently, those versions, or elementsin them, that received universal or near-universal rejection were notalways retained as worthwhile data, and will not be presented here.The people of this community, as well as neighboring communities,do not seem bothered by the existence of different versions. Similarvariations can also be found in the description of the cosmos and in theperformance of rituals. Each narrator bases his or her version on theauthority of an ancestor, usually a grandparent, from whom the version,as told, is said to have been learned. There is, of course, substantialagreement in all the versions, but some of the differences are quite strikingto the outside observer.Faced with the same problem of myth collecting (and analysis)among the Australian aborigines, Stanner (1966, 84) noted: “There isno univocal version of the Kunmanggur myth; nor, indeed, in myopinion, of any aboriginal myth.” Fully aware that the variations arenumerous, Stanner mentions such causes and motivations as“forgetfulness, lack of interest, mentality, prejudice and notion of whata questioner wishes to hear, or should be told,… jealousy, shame, adesire to shine, and an unfathomable malice” (86). In the present case,some narrators, even good narrators, were found to start their narrationat any point in the general sequence of the myth, and jump to otherepisodes as these came into their minds. All these sources of variation,and others similar to them, are common knowledge. A narrator nevertells the myth twice in exactly the same manner.It is the analyst’s task, then, to find his way through this maze ofvariations. He has to make decisions and cannot let them rest on mereintuition or the degree of unarticulated empathy the collector has (orclaims to have reached) with the people’s mentality. As Stanner (84)noted, “the variations do indeed have inspirations and a logic of theirown.” He adds that “the complexity of the myth or those elements ofhuman frailty referred to above are not the more important causes ofvariation,” and he focuses on “the dramatic potential” of the myth,which makes it “variably open to development by men of force, intellectand insight,” suggesting further that this is part of the process by whichmythopoeic thought nurtures and is nurtured” (85). This, however,leaves many questions unanswered.Stanner, and most others, will agree that a successful analysisshould be able to account for all the popularly acceptable variants in amanner that is more sophisticated than superficial knowledge of theculture or a mechanistic approach in the form of some statistical orcommon denominator formula. Stanner is close to the solution of theproblem when he refers to the process of myth making, saying that,“Mythopoeic thought is probably a continuous function of aboriginalmentality, especially of the more gifted and imaginative minds, whichare not few” (85). He ends his discourse quite lamely, however: “The

10 The <strong>Cordillera</strong> Reviewanthropologist is thus under a practical necessity to decide on a version,and under a moral and intellectual duty to decide what is representative.But his decision is also one of art” (86).We will come closer to a firm basis for such decisions if we canarrive at a better understanding of the process of myth making. TheAustralian aborigines quite appropriately call it “the dreaming” whenthey refer to the mythical past as the ground and source of all things.Perhaps an analogy with certain elements in dream-work will permitus to detect a better and more solid ground for the necessary decisionsthat must be made as we face those variants that go deeper than merealternatives which are in the nature of common synonyms. It should berather empiricist to assume that all the variants, just because they arethere and have adherents, are expressions of the same level of discourse.They all do have value and importance, as we shall see, but not for whatthey literally say. In their literal meaning they may actually come closeto contradicting each other. Yet, all of them are true.Since for the sake of ‘credibility and factuality’ it would be bothimpossible and irrelevant to collect all the possible variants of the myth,I collected the versions of as many as a dozen middle-aged and oldadults. All of these persons were considered by their village mates asmore reliable informants. My own growing familiarity with the mythmade me progressively confident that I had a fair representation of themajor variants. In addition, I consulted two dozen persons more, whomI had come to know as rather knowledgeable about custom and belief,and also about these narrations and their variants.The collection of this myth was done mainly during two periods offield work, one from October 1964 until December 1966, and the otherfrom July to October 1971. It was further followed up with occasionalcontacts in the years that followed, and again more intensely fromNovember 1975 until May 1977 through a trained assistant.That the people under study do not have their scribes who mightattempt to streamline their oral traditions has for advantage that theirreligion is not bookish. Actually, the biblical scribes did not do too wellin their selection and editorial work, and had forged what appears tohave been a quite varied tradition of oral literature into a single, artificial,official version which by this very nature hampers analysis. When oralliterature can be recorded in its multivariate expression, as so manyattempts to say the same thing, it is more accessible to analysis.3. Review of LiteratureMany authorities could be cited in support of most of the opinionsexpressed in this monograph. Such an enterprise would be pedanticand boring. As one reads around a topic or problem, one inevitably

The Buntuk Origin Myth 11picks up new ideas which are not always annotated. In this section Iintend to refer especially to the more striking influences on my thinking,and those authors with whom I am in greater sympathy.Field MethodsIn the section on myth collecting, I discussed Stanner (1966). KennethS. Goldstein (1964) devoted an entire essay to research methods inmythology, and has a good deal of good advice to give. I may also referto E. Arsenio Manuel (1975), where he discusses the level of scholarshipthat has gone into the collection and analysis of oral literature in thePhilippines. Manuel has a few studies to recommend, and offers hisown solid criteria of scholarship. As I now see, I have not alwaysfollowed his advice myself, as when he demands a biography of each ofthe story tellers.FormalismAs we look back in time, most folkloristic work has been done outsideanthropology, by humanists. Inside anthropology, its development wascarried by the general theoretical orientation of the time, from Boas’spainstaking collection of texts to Levi-Straussian formalism.During the past half century or more, considerable effort has beenmade toward a systematic treatment of oral literature, both inside andoutside anthropology, as summarized in Dundes (1965). Of particularinterest outside the anthropological tradition is Propp (1968; originallywritten in 1927), who greatly influenced Dundes’s (1964) work. Theseand other scholars attempted to push analysis beyond mere interest inthe tracing of geographical origins of tales, or their classification, to astudy of their form or structure. In due time they became known asformalists or structuralists. Their interest was to find common structuresin folktales, which structures became empty skeletons, consisting ofstrings of motifs whose meanings became ever more abstract andmeaningless as they were stretched to accommodate more and moretales. This reminds us of the fruitless efforts in anthropology to arrive atempirical universals. These humanist scholars, like the anthropologistsjust referred to, created a monster—a hybrid of empiricism andnationalism. Aside from this, Dundes himself had many good things tosay in connection with the study of oral literature. A careful selectionfrom among his numerous articles was published in book form (Dundes1975). On the whole, it seems that the Propp tradition has exhausted itsusefulness for modern myth analysis.The humanist tradition has largely remained untouched bydevelopments in anthropology. One example of an honest attempt atinterdisciplinary contact can be found in Kirk (1970). I can here also

THE AUTHORJULES DE RAEDT was Professor of Anthropology at the University ofthe Philippines <strong>Baguio</strong> from 1974 until his retirement in 1991. Born inBelgium in 1926, he was ordained as a priest of the CongregatioImmaculati Cordis Mariae (Congregation of the Immaculate Heart ofMary) in 1950, and sent to the Philippines the following year to domissionary work. After a decade of various postings in <strong>Baguio</strong>, Kalingaand Nueva Vizcaya, he left in 1961 to do graduate work in the UnitedStates, receiving his M.A. (1963) and Ph.D. (1969) from the University ofChicago. On coming back, Prof. De Raedt taught for a few years at SaintLouis University, a CICM school, before transferring to <strong>UP</strong> <strong>Baguio</strong>, bywhich time he had left the priesthood. His master’s thesis on religiousrepresentations in Northern Luzon appeared in a special issue of theSaint Louis Quarterly (1964), while his works on Buaya society haveappeared in various books and journals, including Kalinga Sacrifice(1989) and Buaya Society (1993), both published by the <strong>Cordillera</strong> <strong>Studies</strong><strong>Center</strong>.The photograph above, from the files of the Philippine Province of CICM, showsJules De Raedt in Kalinga in the 1960s. Photo courtesy of Dr. Carol Brady.

108 The <strong>Cordillera</strong> ReviewTHECORDILLERAREVIEWJournal of Philippine Culture and SocietyVol. 1, No. 1 (March 2009)Who are the Indigenous?Origins and TransformationsLAWRENCE A. REIDVoices from the Other Side:Impressions from Some Igorot Participants inU.S. Cultural Exhibitions in the Early 1900sJUNE PRILL-BRETTBreaking Barriers of Ethnocentrism:Re-examining Igorot Representation throughMaterial Culture and Visual Research MethodsANALYN SALVADOR-AMORESTechnologies for Disciplining Bodies and Spacesin Abra (1823-1898)RAYMUNDO D. ROVILLOSIsabelo’s Archive: The Formationof Philippine <strong>Studies</strong>RESIL B. MOJARESVol. 1, No. 2 (September 2009)Textiles that Wrap the Dead: Some Ritualand Secular Uses of the Binaliwon Blanketof Upland Kalinga, Northern LuzonRIKARDO SHEDDENPolicy Innovations and Effective Local Managementof Forests in the Philippine <strong>Cordillera</strong> RegionLORELEI CRISOLOGO MENDOZAGoverning Indigenous People: IndigenousPersons in Government Implementing theIndigenous Peoples’ Rights ActPADMAPANI L. PEREZExploring the Capabilities of Selected MuslimWomen in <strong>Baguio</strong> City, Northern PhilippinesMA. THERESA R. MILALLOS & ROZEL BALMORESExploring the Pangasinan-<strong>Cordillera</strong> Connection:The Pangasinenses and the IbaloisERWIN S. FERNANDEZFilipino Writers in the United States:Toward a Contemporary RevaluationE. SAN JUAN, JR.

THECORDILLERAREVIEWJournal of Philippine Culture and SocietyTHE CORDILLERA REVIEW is the official research journal of theUniversity of the Philippines <strong>Baguio</strong>. TCR is a multidisciplinary journaldevoted to studies on Philippine culture and society. Given thegeographical location and research thrust of the University of thePhilippines <strong>Baguio</strong>, TCR puts an emphasis on research pertaining to the<strong>Cordillera</strong> region and other parts of Northern Luzon, Philippines. Itencourages submission of comparative studies and papers that contributeto the debate on theoretical and methodological approaches to the studyof indigenous and upland societies. It also accepts reviews of recentpublications related to <strong>Cordillera</strong> and Philippine <strong>Studies</strong>. Although itcannot accommodate scientific or empirical papers in the hard sciences,the journal welcomes articles on science and technology that relate toPhilippine issues and concerns.Review processTCR is a refereed publication that subscribes to the established standardsof academic publications. Articles submitted to the journal are subjectedto a double-blind review process. Initial screening of manuscripts is doneby the Board of Editors. Articles that meet the requirements of the journalare then referred, for comments and recommendation, to external reviewersfrom different academic institutions in the Philippines and abroad. Thefinal decision is made by the Editor-in-Chief in consultation with theother members of the Board of Editors. Together, they review the entirereferee process, to ensure that all editorial suggestions have been addressed.Submission guidelinesThe prescribed length for regular articles is 15 to 50 double-spaced,typewritten pages, inclusive of endnotes and reference list. Longer workscan be considered, based on merit.Manuscripts must be in MS Word format. For typeface, use Times NewRoman, 12 points. Illustrations, figures, and tables should use the MSOffice package facilities and must be in their proper place in the Worddocument. As an alternative, graphic materials can be sent as separatefiles, their placement properly indicated in the manuscript. All illustrations,figures, and tables should be appropriately captioned.TCR follows the author-date documentation system of the Chicago Manualof Style, 16 th edition. Sources are briefly cited in the text, with fullbibliographic information provided in a list of references. All notes shouldappear at the end of the article. Below are some examples of materials

cited in this style, showing the format for in-text citation (T) and referencelistentry (R).Book by one authorT: (Keesing 1962, 201)R: Keesing, Felix. 1962. The ethnohistory of Northern Luzon. Stanford:Stanford University Press.Book with editor as “author”T: (Banks and Morphy 1977, 43)R: Banks, Marcus, and Howard Morphy, eds. 1997. Rethinking visualanthropology. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.Component part by one author in a work by anotherT: (Ileto 1995, 64-65)R: Ileto, Reynaldo. 1995. Cholera and the origins of the Americansanitary order in the Philippines. In Discrepant histories:Translocal essays on Filipino culture, ed. Vicente Rafael, 51-81.Manila: Anvil.Article in journalT: (Worcester 1906, 839-840)R: Worcester, Dean C. 1906. The non-Christian tribes of NorthernLuzon. The Philippine Journal of Science 8 (1): 791-864.Unpublished workT: (De Raedt 1969, 86)R: De Raedt, Jules. 1969. Myth and ritual: A relational study ofBuwaya mythology, ritual and cosmology, PhD diss.,University of Chicago.Article in online publicationT: (Galloway 2001)R: Galloway, Robert C. 2001. Rediscovering the 1904 World’s Fair:Human bites human. The Ampersand, July. http://www.webster.edu/corbetre/dogtown/fair/galloway.html (accessedJuly 22, 2008).For a quick guide to Chicago-style citation, see:The manuscript should be sent as e-mail attachment to any of the followingaddresses:tcr@upb.edu.phcsc@upb.edu.phcordillerastudies@gmail.comContributors must submit a short curriculum vitae, with all the relevantcontact information. They should also certify that their manuscript hasnot been published, and is not being considered for publication elsewhere.

THEHECORDILLERAREVIEWJournal of PhilippineCulture and SocietyVolume II, Number 1 March 2010THE BUNTUK ORIGIN MYTHExplorations in Buaya MythologyJULES DE RAEDT<strong>Cordillera</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> <strong>Center</strong>UNIVERSITY OF THE PHILIPPINES BAGUIO2600 <strong>Baguio</strong> City, Philippines