ArtesanÃa de Galicia - POTSFINK

ArtesanÃa de Galicia - POTSFINK

ArtesanÃa de Galicia - POTSFINK

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

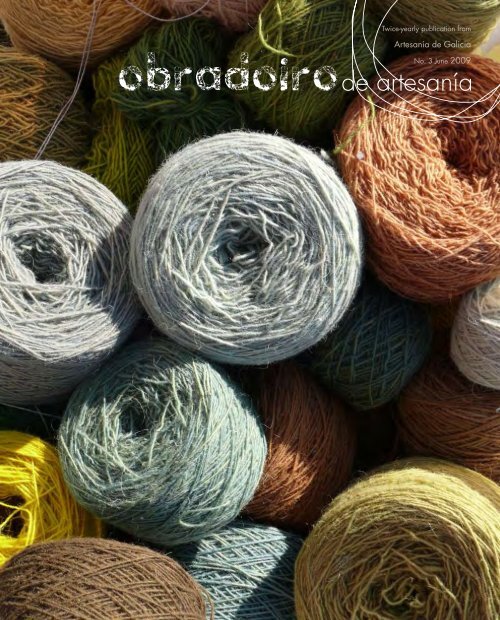

Twice-yearly publication fromArtesanía <strong>de</strong> <strong>Galicia</strong>No. 3 June 2009

Foreword - issue 03Through this new issue we intend to turn the magazine Obradoiro <strong>de</strong> Artesanía [Craft Workshop]into a dual tool for communication, cohesion, <strong>de</strong>velopment and the promoting of the <strong>Galicia</strong>n craftsector. On the one hand – and just as we have proven in two previous issues – this publication functionsas an internal means of communication between the sector and the initiatives that are beingset up from the Economics and Industry Council through the General Directorate of Tra<strong>de</strong> and the<strong>Galicia</strong>n Craft and Design Centre Foundation. It is also a swift communication tool within the sector,so that the craftsmen themselves can get to know the work that is being carried out in the country,can have a platform for exhibiting both the contemporary craftwork that is being ma<strong>de</strong> in <strong>Galicia</strong>and also the relations that this sector holds with other areas such as <strong>de</strong>sign, photography, architecture,fashion and art. In<strong>de</strong>ed, in this third issue we are including an example of the link betweenarts and crafts through the gaze of the director of the Luís Seoane Foundation on the engravings bythe craftswoman Anne Heyvaert.On the other hand it is also a manner of divulging the sector abroad, a way of opening up craftworkthrough different distribution channels. The main one, as it grants greater access, is throughthe web page for <strong>Galicia</strong>n Crafts, which up to now allowed one to make a free of charge PDFdownload. In this issue we are introducing the novelty of the possibility of consulting each of thesections of the magazines through a web space of its own, which can be reached through the pagewww.artesania<strong>de</strong>galicia.org so that access may be ma<strong>de</strong> available to all those interested in thecontents inclu<strong>de</strong>d in each issue.The other methods of distributing the magazine, which will start from this third issue, will bring itto the tourist establishments throughout <strong>Galicia</strong>, to the international fairs which have institutionalcraft stands, to the schools and training centres related to craftwork, and, of course, to the shopsthat have adhered to the <strong>Galicia</strong>n Crafts brands. In this manner we hope to increase the presenceof our sector both in society and on the markets, and at the same time manage to show the greatpossibilities that craftwork has a sector with a future.As for the contents, we would like to highlight the central role played by the first edition of the <strong>Galicia</strong>nHandicraft Exhibition (MOA), held in February of this year, as well as the strong presenceof the traditional craft techniques that, as has become habitual, occupy an important place in thismagazine. In this sense we should highlight the reportages on two areas of <strong>Galicia</strong> that are greatlyconnected to tourism: one the one hand Ribeira Sacra, where the weaver Anna Champeney works,and, on the other, Ancares, where the basket-maker Carlos González is carrying out an importanttask of research and recuperation. The work of the clog-maker Alberto Geada, that of the Taxuslathe workshop, the Códice bookbin<strong>de</strong>rs and the craft application by Luthiers to current <strong>Galicia</strong>nmusic, are a good example of the combination between innovation and <strong>de</strong>sign on traditional craftworkthat is taking place nowadays in <strong>Galicia</strong>.Finally, this issue also stands out because it binds together two activities that are not usually relatedwith craftwork, such as scenography – which we will know through the hands of the characters andthe sets from the Kukas workshop – and then the making of nets, through a report on the O FeitalNet-makers Association from Malpica. The intention is thus to offer an overview of the heterogeneityof the <strong>Galicia</strong>n crafts sector and to stimulate its great possibilities of <strong>de</strong>velopment in the future.

summary04 Textiles with the Ribeira Sacra official <strong>de</strong>nomination12 Patterns of Life18 Between Wicker and Mego Baskets24 Nets, the Invisible Work30 Gallery40 Opinion46 Makers of Harmony52 At the Heart of theWood58 Prêt à Porter Clogs64 Literature Tailors70 To Duplicate Reality. Anne HeyvaertPublished byDirección Xeral <strong>de</strong> ComercioConsellería <strong>de</strong> Economía e IndustriaCoordinated byMaruxa Ledo Arias / María GuerreiroFundación Centro Galego da Artesanía e do DeseñoL25MN Área Central 15707 Santiago <strong>de</strong> CompostelaTN: 881 999 523 Fax 881 999 170e-mail: prensa.artesania@xunta.eswww.artesania<strong>de</strong>galicia.orgDesign, edition and productiondardo dsdardo@dardo-ds.comPhotographyMiguel Calvo, Marcio Machado, dardo ds andcontributions from the craftsmenTranslationDavid PrescottL.D.: C-4788-2008

Textiles with the RibeiraSacra official <strong>de</strong>nominationFabric surrounds us all throughout our lives. It i<strong>de</strong>ntifies us culturally and socially.And yet it goes unnoticed, eclipsed by fashion and ephemeral ten<strong>de</strong>ncies.Anna Champeney, an English ethnographer, has invested in revitalising a techniquethat is natural to the region but which was about to become forgotten:<strong>Galicia</strong>n pile fabric. Although it is not precisely documented, this technique isaround one thousand five hundred years old. Ten years ago she left her life inNorfolk, which is her home in the south of England, and moved to the heart ofRibeira Sacra, to Cristosen<strong>de</strong>, in a house with a view over the River Sil, whereshe makes cloth “with roots”, which release all the strength of the soil and theculture in which they are ma<strong>de</strong>.Anna Champeney discovered Os Ancares in 1995 when she was making a study on popularcraft work, where she discovered a bed coverlet ma<strong>de</strong> with the technique of <strong>Galicia</strong>n pile fabricthat was in a very bad state. “When I touched it in or<strong>de</strong>r to take a photograph of it, it cameapart, and I thought, ‘What a nice piece of work and in such a bad state.’” This aroused aninterest that led her to draw up a project exclusively <strong>de</strong>dicated to these coverlets. “I got the i<strong>de</strong>athat this is what I wanted to do, to take up a tradition that is about to be lost and give it lifeagain, to resuscitate a tradition”. So this English ethnographer <strong>de</strong>ci<strong>de</strong>d to make a halt in herprofessional life and <strong>de</strong>vote herself to textile production in the company of her husband, theCatalan craftsman Lluis Grau, who produces craftwork basket in which he also recovers traditional<strong>Galicia</strong>n basketwork.“What we arepromoting areoriginal works,we want thereto be pri<strong>de</strong> inthis traditionhere in thiscountry”Cristosen<strong>de</strong>, a village on the banks of the River Sil, was the place chosen when almost ten yearsago they started out on an overall project in or<strong>de</strong>r to link craftwork with a sustainable rural farmingi<strong>de</strong>a. Here they are not only producing textiles and baskets, but are also preparing a ruraltourism inn which provi<strong>de</strong>s the possibility to take training courses in their workshops. And sincethey arrived in Cristosen<strong>de</strong> life in this tranquil village has been changing: visitor numbers grew,particularly coming from abroad and from places that are quite unusual in areas like these. InOctober, for example, a stu<strong>de</strong>nt will be coming from Mauritius.“All of us <strong>Galicia</strong>n weavers need to seek a place of our own and make very special products, andone of the ways of doing this is to connect the works to a tradition or to a zone, in my case to RibeiraSacra”. Anna Champeney is aware oft he fact that her works reflect the colours of this land. Not onlythis, she has also taken traditional works from the area, which were the red sacks, and has recuper-

<strong>Galicia</strong>n Pile FabricThis technique that Anna Champeney is recuperatingis estimated to be 1,500 years old,even though it is not well documented as it hashardly been researched. It consists of pullingout each bouclé by hand, which makes it verypainstaking work, given that in a small item,like a cushion, there are over 3,000 bouclés.The coverlets were ma<strong>de</strong> in bright colours andwere <strong>de</strong>corated with floral motifs or geometricforms.“At every step in makingated them for usetoday. “I make aline of sacks andlittle sacks, whichare the works inspiredby the redsacks of RibeiraSacra, items thatno one uses anymore to pick chestnuts, which was what theywere used for before. But instead for bread, for garlic, forspices... It is another way of taking a traditional work andgiving it a new life”.the fabrics there is aphilosophy of respect fornature”In her work the sources of inspiration are two very differentiatedones. On the one hand this is the fruit of a reflectiveprocess which is very closely linked to the origin andmeaning of the works. The other is more in keeping with thetechnical production: “It is the textile structure and the <strong>de</strong>signin itself, the crossing of the stitches, the interweaving, theinteraction of the colours, which change in the weaving andaffect perception”. For her, the act of weaving itself only representsa quarter of everything that goes into the process ofmaking. “I always start out by making a drawing on paperand then I go on to make samples, sometimes mistakes, butI always try to do things differently”. The textile drawing hassomething “technical and mathematical” about it, which isbrought into play with the creative part. What she is workingwith now are cloths that crease. “The challenge is to workwith different combinations of threads in or<strong>de</strong>r to make clothwith texture, textiles with a great <strong>de</strong>al of life”.When it is a matter of works ma<strong>de</strong> in <strong>Galicia</strong>n pile fabric,she tries to explore new uses and different i<strong>de</strong>as thatare now no longer daily use items, which were those thathave traditionally been ma<strong>de</strong> but which, due to their technicalcomplexity, nowadays have very high costs. In this fieldshe makes cushions and is also preparing a collection ofpictures. All of this using a handicraft technique that is asold as <strong>Galicia</strong>n pile fabric, which grants an ad<strong>de</strong>d valueto the works. “I am interested in expressing myself throughthe cloth, thinking of <strong>Galicia</strong>n culture, in my experience asa foreigner resi<strong>de</strong>nt in <strong>Galicia</strong>, in the passion that I have forthe <strong>Galicia</strong>n people, in the history of weaving in”. And sheconclu<strong>de</strong>s, “For me it is a dialogue between myself as anEnglish woman and <strong>Galicia</strong>n culture”.Research“The craft of the weaver is one of the most complex ones, becauseas a craftsman you have problems in finding sourcesof good material, you have difficulties at the time of drawingup patterns and selling your work is not always easy”. In<strong>de</strong>ed,Anna believes that this is why the weaver women thatshe has met have such a strong personality. Like her teacherof <strong>Galicia</strong>n pile fabric, Ermelinda Espín, an eighty-year-oldwoman from Lugo from whom she learned the technique thatshe would then research in greater <strong>de</strong>pth. “Between 1995and 1998 I came across a large number of women whoworked on textiles – retired women, their daughters, customers– and little by little I started to un<strong>de</strong>rstand this traditionbetter, but above all it is the quilts that really teach one

Creative TourismChampeney and Grau propose a different kind of holiday, through creativetourism, an i<strong>de</strong>a that is not yet established in <strong>Galicia</strong> but which hasmany attractive qualities. The i<strong>de</strong>a is to bring together a leisure stay, suchas a weekend or a week, with training in the area of fabrics or basket-making.A training extra for a different way of enjoying a stay in the uniquelandscape of Ribeira Sacra, for which one may board at the A Casa dosArtesáns [The Artisans’ House] rural tourism lodge. A house in which onemay see original coverlets ma<strong>de</strong> using the technique of <strong>Galicia</strong>n pile fabricor a collection of portraits of craft workers ma<strong>de</strong> by Champeney herself. Inthis sense they highlight the importance that they take on in relation to theknowledge and the creative experience of this type of stay, which are goodfor people’s well-being. For this reason they provi<strong>de</strong> different possibilities,both for beginners and for those who wish to perfect their technique ascraft workers who want to refresh their knowledge. “For people who havenever thought of doing craftwork and perhaps had doubts about their capacityto do it, we have introductory sessions that are easy and have goodresults with relatively little effort”, Anna explains, as she indicates that she11

The Colours of Natureconceives the improvement sessions as “a creativeretreat in an environment conducive to creativity”.In<strong>de</strong>ed, Champeney stresses that this type of approachfavours an increasing of sensitivity towardscraftwork: “the more the public tries out and gets toknow the process of craftwork, the more they willappreciate the works we make. I think that in <strong>Galicia</strong>we need to carry out a dynamic and interactivedivulging of this work”.On the other hand, they are seeing that this possibilityis having more success abroad than in theirown country: they have received visits from peoplefrom Denmark and from Great Britain, but stillhaven’t had any <strong>Galicia</strong>ns. “It has to be said thatit is relatively easier to come to Ribeira Sacra forsome creative summer holidays from La Corunnaor Madrid, and I hope that in the future we will beable to connect to the interest that there is in <strong>Galicia</strong>and in the rest of the State”.Anna ChampeneyCristosen<strong>de</strong>, 7832765 A TeixeiraTN: 669 600 620www.annachampeney.comwww.casa-dos-artesans.comlluisyanna@terra.esThe threads that AnnaChampeney uses bear thecolours of Ribeira Sacra.Both the linen and the wool,or even the sophisticatedCashmere are naturallydyed by herself. Althoughshe has to buy some of theplants because they do notgrow well in this area, suchas indigo, she takes otherones straight from nature.Gorse or onion bulbs aresome of these, and have awi<strong>de</strong>-ranging spectrum ofcolours, some so intensethat it seems incredible thatit is possible to obtain themin a natural way. “I consi<strong>de</strong>rthat they are unique coloursand have a special harmony,they combine verywell, and thus gives me awi<strong>de</strong> range of colours”, butthis also solves a practicalproblem common to manycraftsmen: “It is very difficultto find quality thread. I ambuying them from a Catalancompany, and I have to buyin large quantities; it wouldbe impossible to collect somuch of each colour”. Soshe is consi<strong>de</strong>ring the possibilityof commercialising thethreads.“I love having close contactwith the materials, beingable to go out of my houseand find the plants. Thisalso gives me the chance tomake works that have rootshere, which are the coloursof Ribeira Sacra”, AnnaChampeney states.13

Patterns of LifeKukas’s PuppetsSomeone once stated that being a puppeteer wassomething bad. Kukas and Isabel have <strong>de</strong>votedthemselves to this for thirty years, and believethat it is the best profession in the world. Kukasis today the indisputable name in the making oflarge-hea<strong>de</strong>d carnival figures or puppets, withoutever stopping imagining, or pergheñar, asthey say locally. A tra<strong>de</strong> that mixes the stage artsand plastic arts, literature and music and magic.Over these years he has been gathering the viceof thinking, the healthy vice of never stoppingcreating. They are therefore convinced that thebest thing about <strong>Galicia</strong>n craftwork is the creativitythat it releases, that stands out whereverit goes. Kukas’s puppets have exchanged thefold-away theatre box for magnificent stagingsand huge casts like the <strong>Galicia</strong>n Royal Philharmonic,without ever losing the essence of thecompany: everything remains to be invented.14

“We have always takenrisks on the plastic andconceptual levels andthere have never beenany problems”“We have had to struggle, going around with our gear in a rucksack.Nowadays we perform in very important theatres, the Arriaga,the Campoamor…, huge theatres”. Thus speaks Marcelino<strong>de</strong> Santiago, better known as Kukas, a name inseparable from thehistory of puppets in <strong>Galicia</strong>. Because if today it is possible to enjoya puppet show, it wasn’t the case only thirty years ago when hebegan his career as a puppeteer and maker of marionettes. “Atthe beginning there was nothing; we are self-taught”. A work ofacknowledging and dignifying this craft was always present in theirprofessional course. But that is also the stimulus, when everythinghas to be done. Even the word. Isabel Rei, who, along with Kukas,is one of the pillars of Kukas’s puppets, smiles as she recalls thatthey chose the name “monicreques” for the company because of itssound qualities, and which referred to the rag dolls that got carriedon one’s back. “Before no one used this term, and now people evencorrect us if we say ‘marionettes’”.Dolls, rag dolls, ugly face dolls, puppets, big-heads, marionettes…,whatever they are called, they are their lives. Kukas’s hands havebeen building, carving and shaping the recent history of marionettesin <strong>Galicia</strong>. His company is <strong>de</strong>voted both to the production of showsand to the making of the sets that we usually see in theatres or on TV,such as in the Xabarín Club. And they are easily recognizable, with astyle and a <strong>de</strong>sign that are clearly colourist, brutally expressive, andfull of strength and emotion. An eclectic style, as Isabel and Kukascall it, as each work is unique. “Each work has its own style. I don’tthink that a work has to be ma<strong>de</strong> by the same standard. It is like achild. I’m not really in favour of this matter of copying oneself andmaking fifty copies of the same thing”. Isabel highlights the explosionof colour in her work, along with her finishing touches. “A lot of peopleknow you due to the way you finish the work, both marionettesand stage sets, treating them pictorially like paintings”.The protagonists of Seven Capital Stories are ma<strong>de</strong> out of papier-mâché for the heads, and the bodies are ma<strong>de</strong> of carved and painted wood.15

The show Untitled 4x8x6. Mixed media on stage set, used the creativeprocess of a craftsmen who makes puppets which, in a leap ofmagic, jump out of the sketch on the paper into reality, producinga whole puppet show on the boards, ma<strong>de</strong> with the same materialsand the most unlikely techniques, ranging from classical rod marionettesto others ma<strong>de</strong> with pots, clothes hangers and scrap material.Kukas, as a craftsman, has a very clear and stable working process,in which the first and longest phase is that of thinking, “going roundin one’s head” until coming to the point at which the <strong>de</strong>sign can bevisualized, to go on to the technical phase of production, which only<strong>de</strong>pends on his technical skills.And the creative freedom is also greater, both on the technical andconceptual level. Having a studio in Compostela thirty years ago wasmuch more complicated, as finding mechanisms or slightly unusualmaterials implied having to go to Madrid or Barcelona. Nowadays,thanks to the Internet, it is much simpler and everything is within reach.And on the conceptual level everything remained to be done, so therewas nothing left to do but take a chance. “In the theatre and withmarionettes it is important to run certain risks. There was no school,so we tried things out ourselves, and at best we would have to eat theshow with potatoes”, yet Isabel tones down Kukas’s reasoning: “Wealways took risks on the plastic level and on the text and conceptuallevel, and we had no problems”. For this reason each type of show isthought out, discussed and <strong>de</strong>bated, and its plan is drawn up accordingto the i<strong>de</strong>a. Each work requires it own puppet, with its style andits language. “The characteristic of our shows is that we work hard onthe articulated puppet, with unusual or invented mechanisms, with acardboard articulated head and a woo<strong>de</strong>n body”, Isabel explains.Doubts are arising in relation to the continuity of this craft, somethingwhich often threatens so many crafts and workshops. This is generallypositive, although, like everything else, thinks could be improved,and Kukas points out that training is nee<strong>de</strong>d for the tradition not to belost. This is the direction they are taking, with an ambitious large-scaleproposal. The Puppet House is a project that is at the moment goingthrough the phase of “negotiation”, explains Isabel, a centre that isindispensable today, as a logical step to take on their trajectory. “Thisis very ambitious for <strong>Galicia</strong>, but there are similar things throughoutthe world”, so Kukas sees that its viability and pertinence would bejustified. “We are trying to set about creating a centre that will inclu<strong>de</strong>training as well as a museum”, something which Isabel feels is verynecessary. “We have a vast heritage, we have all the marionettes,which are a part of the history of marionettes in <strong>Galicia</strong>, and a veryimportant part. We have kept all the settings, and when we exhibitour puppets we do this as a set, as a part of the show”, somethingwhich is very showy but which occupies a lot of space. Now, for example,they are in the <strong>Galicia</strong>n Craftwork Centre, in Lugo. “We havemore or less structured the basis of what will be the permanent exhibitionof our work”, a space that will also receive temporary showingsfrom other companies and from other places.“Kukas is a person who as a maker, as a craftsman, is very wellknown, and it is a shame if this experience and expertise is lost”,and Isabel thinks that the workshop, both in terms of making puppetsand in teaching others, would be a way of bringing stabilityto the profession and providing jobs. Because research and experimenthave always been a constant factor in <strong>de</strong>signing Kukas’s puppets,in which they acknowledge the great influence on them in thissense by Paco Peralta and Matil<strong>de</strong> <strong>de</strong>l Amo. “They came to givea course in <strong>Galicia</strong>, and they taught us a new way of <strong>de</strong>signingmarionettes, here we had kept to glove and rod puppets”, and theyconsi<strong>de</strong>r themselves to be disciples of these two Andalusian puppeteers.“They gave the vice to me.” She finishes off by acknowledgingKukas himself. One of his major contributions as a craftsman is theresearch he has done into the string support, which has greatly sim-16

plified the manipulating of the puppet, and which, accordingto Isabel, has amazed the eastern European puppeteers,who have a greater tradition in the field of marionettes.The first recognition that Kukas received as a creator andmanipulator of puppets was in Bilbao, in 1997, from thePuppet Documentation Centre. Two years earlier the Peoplesof Spain Theme Park in Kintsetsu in Japan commissioned sixmarionettes from him, which one can visit in its permanentexhibition. They are, in<strong>de</strong>ed, one of the companies with thegreatest distribution outsi<strong>de</strong> <strong>Galicia</strong>, because, according toKukas, “the only thing we can really export are the puppetswhenever we are at international festivals”. And withoutsimplifying or standardising, “our marionettes are purelyand legitimately <strong>Galicia</strong>n,” says Kukas. “We are exportingvalue. It seems to me that this globalization business aims at<strong>de</strong>stroying all cultures, and I reject this, so just as we bringthe Vietnamese here, I want to be taken there as a <strong>Galicia</strong>n,not through being globalised”.Kukas and Isabel came to the field of puppets in or<strong>de</strong>r to fill acultural gap they <strong>de</strong>tected in <strong>Galicia</strong>, somewhat by chance.“It was the inertia of the fact that there were no marionettes in<strong>Galicia</strong> and this carried out a function and people started callingfor us from everywhere” and, as Kukas points out, “andthen we realized we were immersed in this world”. Why?Because in the puppets they discovered theactivity that complemented their interests:plastic arts, literature, poetry and music.Now, with a vast career, involving over fortyshows, after collaborations from such as the<strong>Galicia</strong>n Royal Philharmonic, they only talkabout satisfaction and effort when they lookback and do not forget that there is still agreat <strong>de</strong>al to be invented.“Thirty years ago no one calledthem puppets, and now peopleeven correct us when we call themmarionettes”Set for the TV programme TVG Xabarín Club, at the mo<strong>de</strong>l stage, during construction and when finished.17

“My process is to think for a long time untilI see everything really clearly”In the thirty years thatKukas and Isabel havebeen working with puppets,although the productionof shows is their most popularactivity, their workshop has alwaysbeen another fundamentalaspect of the company.Is the marionette workshop oneof the ways of making this businessprofitable?ISABEL: Of course. There are seasons with a lot of showsand others without so many. And there is also a <strong>de</strong>mand.KUKAS: There are also certain jobs such as making propsand sets, or even making marionettes for other companies,which we have also done.I: In<strong>de</strong>ed. It is a job that makes Kukas an artist and a craftsman,doing what is required, making marionettes, props,posters and sets … Because in fact these works are allinterrelated. We have three fundamental activities in thecompany: the production of puppet shows or puppets withactors; then the craft workshop for sets, props and papiermâché;and we have another activity to which we <strong>de</strong>votetime, which is teaching. Kukas spends a lot of time almostexclusively giving Occupational Training course in theCraft Centre in the Theatre Course at the University; almostevery year we give courses in making and manipulatingpuppets, especially in Lugo.This is a mixture between a handicraft componentand an artistic one. How does this relationshipwork? Where do the two meet and separate?K: Well I’m not really sure where the crafts end and theart starts, or vice-versa. I see things that say “This is art”,and I think, “Well, because you say so”, I just see a handthat worked; it doesn’t transmit anything to me. And othertimes they say, “No, this is a piece of handicraft”. But look,working on stone like Master Mateo worked, what wasthat, craftwork or art? I don’t really know where it startsand stops.K: Handicraft work is usually un<strong>de</strong>rstood as that of producingseries, and so we don’t ever do that. Each work isunique. But the person who makes individual works is alsoa craftsmen. At best craftwork is a type of art that can moreeasily become accessible to the people, and art is somethingthat only capitalists and millionaires can achieve. Idon’t know the difference.I: Crafts also have a more practical, useful aspect.K: But if it doesn’t have a functional element, I don’t knowup to what point craftwork is not art, such as in the case ofa <strong>de</strong>corative plate. In <strong>Galicia</strong> there was a time when therewere some fantastic ceramicists, and there still are, and Ialways won<strong>de</strong>red why this wasn’t art, because I adoredthat type of craft work, it was so interesting. And if thecraftsman is the creator … I think <strong>Galicia</strong>n craftwork isvery creative. What impresses everyone outsi<strong>de</strong> of <strong>Galicia</strong>is that it is so creative.The last show, Untitled 4x8x6, portrayed theprocess of the artistic creation of the puppets. Init the drawings leap out of the paper into realitythrough a magical trance. The real process willbe somewhat different...K: I don’t know how other artists do things. I know how Ido it. There are creators who start out by scribbling on thefloor and look at the scribbles, to see what they discover.I have a process that involves spending a long time thinking,getting up early, going over things in my head until Isee things clearly. When I see them clearly I draw them onpaper. I have to see them very clearly. The process of thinkingtakes me a long time, and doing it takes a short time.Other artists or craftsmen start mo<strong>de</strong>lling the clay as if thework might tell them what is insi<strong>de</strong> it. But when I make theclay I’ve already seen what’s insi<strong>de</strong> it. My process is moreof a mental one, of going round in my head first.And then is it easy to reach the aim?K: Very easy. Then it’s a matter of technique, like writing.These are craft techniques, whether it is painting or sculpting,nothing odd. What you have to learn is the language,the process. Then the creative force <strong>de</strong>pends on each person.No one teaches that at any school.I: A lot of the work that we do has in principle a handicraftpart, and then it has an artistic si<strong>de</strong>. They are normallyunique works, ma<strong>de</strong> with an artistic intent.18

Types of puppetsRod PuppetThe movement of the puppet’s limbs is ma<strong>de</strong> usingrods.“Research hasalways been presentin our marionettes,firstly because weare self-taught, andthen due to a need,like a vice”Glove PuppetManipulated by hand insi<strong>de</strong> it.MarotteThe puppet’s hand are replaced by those of thepuppeteer.String MarionetteManipulated through strings attached to a crosspiece.Finger PuppetSmall heads set on the finger like a thimble.Flat PuppetUsually flat woo<strong>de</strong>n or card figures moved frombelow with rods.Direct Hand PuppetThe puppet is manipulated in full view of the spectators.Chinese ShadowsA silhouette of the moving figures is projected.Pe<strong>de</strong>stal PuppetThese have a rod on their upper part and a woo<strong>de</strong>nsupport like a pe<strong>de</strong>stal below.Marcelino <strong>de</strong> Santiago (Kukas) and Isabel Reifoun<strong>de</strong>d Kukas’s Puppets in 1979.They <strong>de</strong>vote themselves to <strong>de</strong>signing and makingpuppets, masks, big ugly head dolls, propsand stage sets, posters and programmes.They have produced around forty puppet showsand regularly give courses in countries such asPortugal, Brazil and Greece.Kukas produccións artísticas S.L.Lino Villafínez, 11 –1º D15704 Santiago <strong>de</strong> CompostelaTN/fax: 981 562 734609 884 630 / 660 298 070www.kukas.biocultural.netmonicreques@mundo-r.commonicreques@hotmail.com19

Traditional basketryThere are three specialties in traditional basketry: wicker, thatch and wood.Wicker basket work is also known as twig basket work, given that one can use othertypes of flexible twig bushes such as willow, gorse, genista, cytisus, myrtle, hazel orelm. These twigs are woven with different techniques and are ma<strong>de</strong> into different forms<strong>de</strong>pending on their use. Stripped wicker corresponds to urban basketry, while wickerwith skin is for rural uses.In thatch or rye straw basketry one rolls a sheaf into the shape of a spiral, tied up witha strip from another plant. They are very tightly woven baskets, so they were i<strong>de</strong>al forthe carrying seeds, grain and even flour.The basket-maker has to manipulate the split or sliced wood, getting the bla<strong>de</strong>s fromthe trunks of chestnuts, willows or oaks. In intertwining these strips one can above allmake the patelas, elongated and shallow baskets used particularly for carrying fish.22

“Our work used to beconsi<strong>de</strong>red as a complement ofthe men’s work”Nets, the Invisible WorkThe making and repairing of nets was work that was not recognised as such for a long time. Over recent years alot of work has been carried out to dignify this craft, which in most cases was in the un<strong>de</strong>rground economy withextremely low wages. In this sense a vitally important role was played by the vindications of the net-makers themselves,as most of the net-makers are women.Ángeles Millé is a net-maker, presi<strong>de</strong>nt of the O Fieital Association, in Malpica, and is also the secretary of the “OPeirao” Fe<strong>de</strong>ration of Craft Net-makers, a group thanks to which her voice is heard lou<strong>de</strong>r and in many other places.And she brings us to this craft, in a struggle half way between labour recognition and the feminine.At what time does the day start for a net-maker?We start at seven in the morning and, <strong>de</strong>pending on the work wehave, we don’t stop until eight or nine. And as we are autonomous,we also divi<strong>de</strong> domestic work with this work. We don’t have a fixedtimetable, and when there is a big workload we sometimes go onuntil ten at night. It’s something we have in common with other autonomousworkers.How did the Fe<strong>de</strong>ration of Craft Net-makers comeabout?The association was formed after several meetings with the FisheriesCommission. One could see that there was a craft that was beinglost and that was remaining anonymous. One didn’t see it. Peoplestarted to come together from all the ports in <strong>Galicia</strong>, and theyfound that there were people with many common concerns. The associationsstarted to be formed in 2002, and after the catastropheof the Prestige oil spill we agreed to form a fe<strong>de</strong>ration that woul<strong>de</strong>xist for all the ports in <strong>Galicia</strong>.How did the Prestige disaster give an impulse to thenet-makers’ union?Until that moment we didn’t have any contacts among us. Manypeople worked on the ships and others did the work at home, andas a consequence of Prestige, we started to get to know each other.We nee<strong>de</strong>d to be heard, because after the sinking of the Prestigewe wanted to earn, like everyone, because we were registered andpaying contributions.Did it affect you in the same way as the fishermen?Ours was a sector that was hit badly and is still being affected bythe other problems in the fishing sector. When there is a shutdown,if you are working on an art you have to stop working. Sometimesyou can do some other art, but on other occasions you can’t, becauseyou don’t have access to it or it doesn’t exist where you live.In these cases you just watch things come and we carry on withoutcounting on help.What has been the Net-makers’ Fe<strong>de</strong>ration’s main strugglesince its creation?Since the beginning we have struggled to get our professional dignityrecognized, because as women we are marginalised. Our workis recognised as a complement. It is like the man is the one whobrings the money home and you help him doing this. But it isn’t likethat.At the moment, the Fe<strong>de</strong>ration has been looking at professionalillnesses so that we don’t get told when we get an illness that it isa common disease. Cervical pains, arthritis, tendonitis or carpaltunnel syndrome, which affects one’s wrist, are consequences ofthe repetitive movements and the postures we have while working.Tiredness is normal in all jobs, but there are forms of tiredness thatlead to illness, and that is what affects net-makers most.The work of the net-makers has traditionally been seenas a complement to the work of the fisherman, and forthis reason they worked irregularly, without registeringas autonomous workers. Is it still like that?Unfortunately that still happens. It is the un<strong>de</strong>rground economy that isprovoked by the chandlers and by the intermediaries. It is something27

we have been <strong>de</strong>nouncing in the OPeirao Fe<strong>de</strong>ration and through theassociations themselves, becausethis is very harmful to us in manyways. On the one hand you haveno work, because they only giveyou work when the others havetoo much. When there is no oneto turn to they <strong>de</strong>ci<strong>de</strong> to cometo us who are legalised. Most ofthe time this is what happens, becauseit is much easier for the intermediaryto take the work to a house where,besi<strong>de</strong>s the woman, the children work orother people who work with them.What percentage of people who <strong>de</strong>vote themselves tomaking and repairing nets work in an irregular manner?According to a study ma<strong>de</strong> by the Industry Commission a year ago,in <strong>Galicia</strong> there are over two thousand people doing this work,but registered is only seven hundred are registered. That meanswe have sixty-five percent infiltrations. We are mainly talking aboutpensioners, but a person who is seventy or eighty finds it difficultto work. There are fishermen who retire before reaching sixty and<strong>de</strong>ci<strong>de</strong> to play cards in the afternoon and spend the morning workingon the nets. The fishermen have a lot of experience and can helpthe net-makers, guiding them in their work, but they are workingagainst us, competing with us. We had the opportunity to travel tothe Basque Country, where we met other net-makers from the wholeof the Cantabrian coast. We saw that they nee<strong>de</strong>d the help of theretired people, people with experience, and when they need themthey called them and they were there.Why does precisely the opposite happen in <strong>Galicia</strong>?The ports most affected by this situation in <strong>Galicia</strong> are Guarda,Malpica and Ribeira. It is precisely where the chandlers are, whogive work to the intermediaries. The latter prefer to give the workout to the houses, rather than to the professionals, whereas in theother areas, where they work directly with the ship owners, illegallabour doesn’t exist.Is your salary suited to the work you do?What isn’t normal is that we have a day’s work of eight, twelve orthirteen hours in or<strong>de</strong>r to earn a salary that is below the minimumwage. Now we are trying to unify the salaries in the different portsin <strong>Galicia</strong>. The work is the same in the different areas, but the paymentvaries from place to place.How did you start working on the nets?I did a lot of different things before I became a net-maker. I studieduntil I was nineteen. I took a course in administration, but I preferredto <strong>de</strong>vote myself to my house. When I saw that the children weretwelve or thirteen and could look after themselves I started workingin agriculture, and one day, by chance, an intermediary offeredme a job working on repairing nets. I started doing it and liked it,but I never imagined financial in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nce. No matter how littleyou earn you see that you are contributing towards the house andthat ma<strong>de</strong> me feel good. At the end I <strong>de</strong>ci<strong>de</strong>d to leave agricultureand I <strong>de</strong>ci<strong>de</strong>d to get into this on a professional level. Fourteen yearsago.Is there enough work for the net-makers?There is a great <strong>de</strong>al of work. The problem is that it is badly divi<strong>de</strong>dup. If they improved the conditions and we had a worthy salary thatpaid well for the day’s work then young people would get involvedin this. I’m involved in teaching this to young people so they canwork, but with a salary that allows them to live. The ones we aremaking now are in or<strong>de</strong>r to keep up our contributions, because atour age, between forty and fifty, there isn’t much more to turn to.In or<strong>de</strong>r to improve your situation you first have to getyour work to stop being anonymous. Is the Fe<strong>de</strong>rationworking towards obtaining this recognition?We are managing the professional qualification of the net-makers,we are <strong>de</strong>manding that our work be recognised. In or<strong>de</strong>r to registeryou need a diploma, and that contributes towards people not doingit un<strong>de</strong>rground, because training is very important. The FisheriesCommission manages the courses through local guild associations,which is what we know, but we net-makers don’t belong to theseguilds, which are only for fishermen and people who extract thingsfrom the sea. That isn’t our case, because our work is only thatof making or maintaining the nets. We are in<strong>de</strong>pen<strong>de</strong>nt from theguilds.It also <strong>de</strong>pends on the Administration to obtain professionalrecognition.Yes. We achieved something from the Vice Presi<strong>de</strong>ncy, which thisyear brought out the Arlinga programme. This accepts the net-makers,but can’t go any further, because the Vice Presi<strong>de</strong>ncy has noauthority over the sea. In the Fisheries Commission, in training, wehave a hundred percent, but we still have to solve the problem ofunregistered workers.What can you do to end unfair competition?That’s in the hands of the Work Commission. They intend to dosomething, and they are seeing whether the Treasury Office cando something to get the un<strong>de</strong>rground economy up on the surface.They have to control it; there have to be receipts to prove where theboats get the material and who did the work. The situation is thatwe are a very pacific group and here everything works on the basisof struggle and war. Once we called a <strong>de</strong>monstration and after twodays we had an inspection in the ports. If we don’t do anything noone pays us any attention, and I believe that it’s also because weare women.The Indispensable HandIs there any industrial alternative to hand-ma<strong>de</strong> nets?It has been tried, but manual work always has to be there. It also<strong>de</strong>pends on the nets. In the case of the frame in the past it was alldone with hemp and cotton string. Now these arrive and what thenet-maker does is to put them together or repair them. In the smallernets one used to work with the same strings and the women repairedthe nets, but now they come ready ma<strong>de</strong>. Our work consistsof linking them, tying one piece to another. In the case of the long28

line nets they tried to use a machine to make the knots in the net, but they were alwaysslipping and coming loose when they went into the sea. The only thing to do was to goback to manual labour. Up to now no one’s invented a machine that can do our job.What fishing nets do you work with?They are different in the north and south of <strong>Galicia</strong>. In Malpica we have trawling nets,that the men usually work with, as they are very heavy. Then there are the ring frame, thesmaller nets and the long line ones.Let’s take this in parts; what is a trawler net like?“There are over2,000 peopleworking as netmakers,butonly 700 areregistered”It is a large size net. It is based on a bag that is dragged along the sea bed and is closedwhen the fish is insi<strong>de</strong>.You said that the trawler nets are mainly used by the men. What are theones you work on most?I work on the smaller one and the long line nets.What is a long line net?It is a selective net. We can distinguish between a <strong>de</strong>ep long line net, a surface one andshort one. Each of them is ma<strong>de</strong> up of a “mother line” on which the hooks are hung, an<strong>de</strong>ach one catches a fish. It is a smaller fish than in the trawler net, which captures all thefish together and it reaches the boat all crushed up. When they get to the fish auction thelong line fish are of better quality and fetch a better price. They also require a lot of workfrom the net-makers. I think that within five years I will have to stop this job. You have toAsociación <strong>de</strong> Re<strong>de</strong>iras O FieitalMuelle Norte, 5015113 MalpicaA CoruñaTN: 618 311 79829

stand up and do the same repetitive movements, and when one getsto fifty we go on to the smaller nets.What are the smaller nets?They are nets ma<strong>de</strong> of cloths that are tied to a rope and that aremainly used in shallow water fishing. They used to get repairedwhen they came back from the sea damaged, but now the quickestand most economical thing to do is to take the cloths of and tie somenew ones on. You save a lot of time. Before you used to spend thewhole day repairing the mesh and now you can change several inone day.What materials do you use to make the nets?Depending on the thickness of the mesh you use one string or another.Those that are for Gran Sol have plastic strings that can be usedand taken off. When it is to tie up (to attach the cloths to a rope) youcan’t use these strings because they slip, being plastic. Mostly wework with synthetic materials, but we still use cotton for the long linethreads because we need them to keep really tight.Has there been an evolution in the materials over recentyears?They’ve been modified, but the net is still the same. The materialsare more accessible and more resistant, but the manual work isstill the same. The mesh has to be treated in the same way with thesame steps.You have had the chance to exchange knowledge withother net-makers in the Basque Country. Are the netsma<strong>de</strong> in the same way here in <strong>Galicia</strong> as in the rest ofthe Cantabrian cornice?It’s the same. In<strong>de</strong>ed, we make a lot of long line nets here for theBasque Country. The intermediaries and the chandlers give us a lotof commissions for work for abroad, as <strong>Galicia</strong> is the place wherewe make more nets. We work for the Basque Country and Asturias,but also for France, Argentina and Chile...Is the business going to do well in the future or will ittail off?It’s not going to be lost because it is a craft. Until they invent machinesto replace us, and maybe they will, handwork will be necessary.Can there be nets without net-makers?The fishermen also work with the nets on the boats, and when thebad weather comes there is no work for us but just for them. Thosewho work in shallow water fishing, when they have to stay on land,occupy themselves repairing the nets, and so they save money. Ifthey have to go to sea next day they need to rest and so then wehave more work. In the case of the fishermen who go to Gran Sol,who take at best two thousand nets on each ship, they give us thework to do over a fortnight and we have to work all the hours possible.When they have less quantity they themselves repair the nets.How important is it for you to hold live exhibitions, likeyou did at the MOA?Many people leave this when they can’t make a living, and nowwe are going to diversify our activity. Just like we showed our workat the MOA, we want to go to schools to teach our work to youngpeople, because we believe that it also good for the young peopleto know it. What we do is a part of <strong>Galicia</strong>n culture, and wassomewhere in the background without anyone realizing that thesewomen were here doing this work. The important thing is not onlywhat you are earning, it is what you can transmit to people who areinterested in your work at events like the MOA. There were groupsof people who wanted me to explain what we did to them. Whenwe eat fish we don’t ask where it came from and we don’t knowwhat the nets are like, or how they are used. Even ol<strong>de</strong>r people aresurprised by what we explain to them. It is important for the worldof the sea to be present in these fairs, and we thank the MOA forthinking of us.Your movement has a good <strong>de</strong>al of feminist complaint...The situation has evolved, and the women themselves have achievedmany rights for which we had to fight, but we still have a lot to do.It is like men have to bring the money home and that we do, if wecan do so, it’s even better, but the fact is that work is there for men.Fortunately this is changing. Women are getting on to the labourmarket, and our professional labour has to be recognised.Were you able to convince them that in the small fishingvillages there is work for them?Of course there is work! In<strong>de</strong>ed there is someone who does it. Whatis not normal is that there is so little work officially registered in billsto the Treasury if there is so much work going on. The un<strong>de</strong>rgroun<strong>de</strong>conomy has to come to the surface sometime.Are you managing to get young people into your activity?Young people are nee<strong>de</strong>d, like in all jobs, because we have theexperience, but young people have a great <strong>de</strong>al to offer. When youpass things on to other people you see things that you have missedbecause you are fed up of doing the same work all the time. Youngpeople bring you freshness, they liven you up, and that is necessary.30

Belategui RegueiroLugar <strong>de</strong> Outeiro, 15. Cambre / TN: 981 674 55733

Encaixes MónicaDor 92. Ponte do Porto / TN: 981 730 46034

Olería <strong>de</strong> GundivósConcello <strong>de</strong> Sober35

Tejidos vegetalesHortas 7, Cela. Outeiro <strong>de</strong> Rei / TN: 982 390 66636

Pendant: Mayer Joyeros [necklace: A mouga]Espasan<strong>de</strong> 2, Luou.Teo / TN: 981 893 094 37

SedaníaÓrbigo 14, 3A, Virgen <strong>de</strong>l Camino. León / TN: 987 300 80538

Marion GeissbühlerVon Tavelweg Konolfingen. Switzerland / TN: +0041 317 910 32239

Chonín Ruesga NavarroOrégano 5, Palomares <strong>de</strong>l Río. Seville / TN: 955 763 26141

“The MOA has been set up in a settingof the most original creative diversity”Aure ChardonSpecialised Press, Grupo Dúplexwww.grupoduplex.comWe believeit is veryimportant toparticipate inthis role asa promoterof “Ma<strong>de</strong> in<strong>Galicia</strong>”Quality. What stands out is the quality of thosewho are here to display and the products onshow, both due to its excellence on the artisticand craftwork levels. With reference to the jewellerysector – a field in which the Grupo Dúplex isa specialist with over thirty years of experienceat the forefront of the specialized press – we arehighlighting the great participation of this productivesegment that is so important in <strong>Galicia</strong>, withconsecrated names such as Óscar Rodríguez,Ar<strong>de</strong>ntia, Fink Orfebres or A Feitura, among others.In these cases we are talking not only aboutrecognition of the handicraft aspect, but also theproductive capacity, facts that are <strong>de</strong>monstratedas these companies grow throughout their professionalcourse.Creative Diversity. Jewels, objects for thehome and for <strong>de</strong>coration, ceramics, bags, musicalinstruments... The MOA was started in atrue setting of the most original creative diversity,not only within our bor<strong>de</strong>rs. The existenceof an invited country, Switzerland in this first edition,contributes towards enriching the range ofsuggestions for the customer, providing a veryinteresting multicultural dialogue both for the exhibiterand the visitor.Supply. From the most attainable to the mostexclusive item. At the MOA there was room forall price levels, so that the visitor could in factfind everything all together. Fortunately the originalitywas in the product and not in its cost.Image. We particularly call attention to thechoice of the colour orange (a dynamic and activecolour) and the single aisle concept, whichgrant a very pleasant touch to the showing. At thesame time visitors to the MOA could enjoy someservices and a programme of events <strong>de</strong>signedfor their total comfort and satisfaction (restaurantarea, a choice of evening shows, etc.).Ma<strong>de</strong> in <strong>Galicia</strong>. With the MOA we are notjust talking about the good event called uponto be consecrated as a setting for the protectionof the craft and of its product. We believethat it is very interesting to focus on its role asa promoter of what is “ma<strong>de</strong> in <strong>Galicia</strong>”, stimulatingcollaboration among the several differentsectors involved and the institutions towards thedivulging of traditional <strong>Galicia</strong>n craftwork andits cultural heritage on the national and internationallevel.Pioneering Initiative. In Spain there arefew, or we can almost say hardly any exampleslike that oft he MOA. For this reason itspioneer nature, its vocation for the future and itsrelevance as an element that promotes ad<strong>de</strong>dvalue inherent to work by individual authors isundoubtable.42

What say the murmurers?OpinionDavid BarroArt Critic and Exhibition CuratorThe challenge was difficult: to set up an innovating and pioneering fair in <strong>Galicia</strong> in or<strong>de</strong>r to put our craftson an international perspective. There will be those who didn’t un<strong>de</strong>rstand, who haven’t travelled andseen how these things take time and effort, who believe that the costs don’t justify the result. But the factgoes far beyond what one can see over three days, and the promoting of our handicrafts will remain inthe memory of those who only heard of it, of those who were only aware of that reality when they saw theadvertising, of those who had the opportunity to look at the catalogue, of those who were able to enjoythe promotional vi<strong>de</strong>os, of those who <strong>de</strong>lve into the memory-book published days after the fair or of thosewho are reading this magazine.There is no lack of i<strong>de</strong>as in <strong>Galicia</strong>, but there is a lack of connections, intermediate spaces, bridgingplaces for the up and coming elements of our craftwork can <strong>de</strong>velop, for us all to become aware of itsuniversal character and of its existence beyond the topics. On many occasions we have spoken about theperiphery and about our position, more than due to the physical situation, this concept comes about becauseof budget restrictions and efforts that haven’t been carried out. <strong>Galicia</strong>n culture and our handicraftshave abused of an imaginary that insisted on their exclusively rural origins, and in that sense it is necessaryfor it to acknowledge itself also as being avant-gar<strong>de</strong>, with neither reticence nor prejudgments. Andthis was possible at the MOA, in the quality of its exhibitors and their products, in the mo<strong>de</strong>rnization oftheir image, in the diversity of the proposals, in its condition as a meeting point and as a place to <strong>de</strong>velopand grow. The effort was great and was important, although certainly not enough, because it is urgent tocarry on, to go forward on the path of the normalization and internationalization of the handicrafts sectoras has been achieved in other sectors.For those who now the universe of fairs, managing to get eighty one exhibitors is something exceptional.As is the quality of some of the craft workers and artists who participated in the exhibition. In the Gallerythe aim was to expand the concept of craftwork, precisely seeking out the less commercial products and aconfrontation between <strong>Galicia</strong>n handicraft and contemporary international handicraft. Thus there was thesetting up and presenting of the works assuming the unusable area of the space for a series of performancesthat granted life and movement to the exhibition. We were thus able to move through the imagesand empower the i<strong>de</strong>a of a parallel “event” in or<strong>de</strong>r to give primacy to surprise and to explore that placeas a craftwork space in which anything might happen. Important craft items, some of a monumental size,surroun<strong>de</strong>d a meeting point or a leisure area presi<strong>de</strong>d over by a radio programme that granted a voiceto the true protagonists of the fair, the exhibitors and guests. Always starting from one premise: to connectthe country and comprehend that which Tolstoy stated: “paint your village and you will be universal”.43

Switzerland at the MOAPeter FinkExhibitor (Switzerland)PotsfinkRoute du Petit Epene<strong>de</strong>s 3Epene<strong>de</strong>s-Fribourg. Switzerlandwww.potsfink.chinfo@potsfink.chMOA is the foremost professionalevent for those who work in thecraft and <strong>de</strong>sign sectors. Thisis the best place for creatingnew collaboration and businessnetworks:Expocoruña covers 7,500 m 2 .1,200 accredited professionalvisitors.A hundred exhibitors bring quality,<strong>de</strong>sign and innovation.High quality international guests.The exhibition was accompaniedby concerts, artistic performancesand other cultural events.The MOA showing has beenplanned to be an annual event,and is organized by the <strong>Galicia</strong>nFoundation for Handicraft andDesign, with the aim of becoming apermanent fixture in this field.They walked the path. The authentic one, theone that leads us right into the heart of eachone of us, which might change a man. Aneternal seeking, that path. Nineteen yearslater on I am off again, but this time I amin the company of fellow craft workers, andthe path does not take us to the cathedral ofSantiago <strong>de</strong> Compostela but rather to» Expocoruña,the burgeoning new exhibition centrethat has been set up in La Corunna. Thistime our professional activities are our centreof interest. We are all professional handicraftcreators. Sharing our know-how, exchangingi<strong>de</strong>as with our colleagues from <strong>Galicia</strong>,discovering another market far away from usand, besi<strong>de</strong>s this, receiving commissions.From my house in Lausanne I took 72 days toreach the hill that dominates the city; this timewe could do with a few hours before leavingour bags in the hotel on the other si<strong>de</strong> of thestreet that separated us from the exhibitionsite. Preparation for the whole journey is veryimportant: the phase of uncertainty, dreams,technical preparation. I was in charge offorming a group of Swiss quality craft workers,mixing up many different styles, but balancedand representative. I couldn’t havedreamt of anything better, <strong>de</strong>spite the tighttime schedule, an unknown fair and severalaspects that nee<strong>de</strong>d clarifying.In a click, and after some returned correspon<strong>de</strong>nce,the technologies allow me tocontact hundreds of Swiss craft workers whoare potentially interested in the project. Thenumber of replies was consi<strong>de</strong>rable: not one,not two, twenty-five enrolments were thosethat came together and proposed themselvesfor consi<strong>de</strong>ration by the Foundation. And agroup of ten craft workers is chosen. Later oneperson withdrew and was replaced; anotherone was eliminated when it was discoveredthat they produced everything in Asia, andyet another was unable to keep to this commitment.Others presented themselves, butafter the time period allowed. So then therewere eight of us craft workers from differentareas. The textile section, <strong>de</strong>spite being verystrong in Switzerland, was absent. A shame.Then comes the trip itself. The time of action,but also of suffering and fun. In the time ofthe journey on foot I would put my walkingboots on, put my rucksack on my back, havemy maps handy and the direction clear. Thefirst kilometre would start and there were twothousand more left. This year was the same.Collaboration and communication with theorganisation are extraordinary; everythingworks perfectly. On arriving, our works arealready there, the stands ready, and weplace our objects on them. The translator introducesherself; Cristina will always be thereto help us! We visit the exhibition in the assemblyphase. Will there really be a crowd ofpeople tomorrow? The three days that it lastsare a hurricane, the press is there, we makecontacts, and we compare and share ourknowledge. Exhibitions, music, dance andgastronomical pleasures. After the fair travelaround the country, presenting our work andtraining interested young people. Anotherstrong point for us in relation to feeling thehistory of <strong>Galicia</strong> was unforgettable – seeingsome craft workers from Sarga<strong>de</strong>los in theirworkshops.Return from a pilgrimage has a bitter taste.One has to go back to real life and getback to work as if nothing had happened.Yet these 72 hours in nature with only myessential needs had a <strong>de</strong>ep effect on me.Returning from the MOA, as such, leaves usoverwhelmed by the innovation and boldnesson the part of the organisation to proposeexhibitions, concerts and other cultural eventswithin a commercial fair. We didn’t expectthis. On our si<strong>de</strong> we kept to our mission: toenrich and diversify the MOA, showing whatis done – very differently – far from <strong>Galicia</strong>.Back in Switzerland I get messages from craftworkers: they tell me about the coming year.A new Swiss group calmly takes shape. TheMOA has become visible beyond <strong>Galicia</strong>,the path is fertile and the generosity of Finisterrahas en<strong>de</strong>d. But there is still more ambition,to do things clearer, better and muchbetter, and that is the way forward, the onlyway forward. The true craft worker will alwaysfollow it.44

Opinion“The MOA is importantas a meeting pointbetween products andtra<strong>de</strong>spersons”Luís SantínExhibitor (Artesanía <strong>de</strong> <strong>Galicia</strong>)Luís Santín has been a professional leather craft worker for twenty-seven years inhis Santín workshop in Cambre. A period during which his distribution strategieshave changed as his workshop became consolidated and his products were settledon the market. For this reason Santín is convinced that tra<strong>de</strong> fairs like the MOAare fundamental to stimulate and facilitate relationships between tra<strong>de</strong>spersons andcraft workers. “I went from selling in the street to going to international tra<strong>de</strong> fairslike I do now”, Santín explains. “Professional tra<strong>de</strong> fairs by sectors are necessary,because these are the contexts in which we can sell to shops”, and in this sense theinternational vocation is crucial, not only due to sales, but also to grant visibility to<strong>Galicia</strong>n handicrafts. “If we are not there, like on the Internet, we do not exist”, heargues.“For me the MOA is indispensable, but it is important not to make a political war outof it”, given that, according to Santín, the MOA has been set up as a commercialand professional meeting point, and should therefore be consolidated as an annualevent in this sector. “The name ‘MOA’ itself is a heritage, one which will increasewith every passing year and that can’t be taken away”.In addition to this, he thinks that it is necessary to change the manner of assessingthe succession and the repercussions of this type of event. “In <strong>Galicia</strong> my productsare in more than 160 shops, and I have a distribution firm. So it is these tra<strong>de</strong> fairslike the MOA where people meet Santín and Santín gets to know the shops, andthat is very important”, he states. “That meeting means a verbalising of the objects,setting my products against what people think. The MOA allows us to find somecontact with reality, which means the shops, giving us very important information”,he assures.SantínUrb. Camiño, 31. SigrásCambrewww.santincuero.comluis@santincuero.comSo the results of a tra<strong>de</strong> fair should never exclusively be the sum of the or<strong>de</strong>rs at theend of the meeting, but rather the relationships and the contacts that are establishedduring these events have a value that is as much or more important than direct sales,as is shown by this workshop specialized in leather work. “Analysing the value justthrough the or<strong>de</strong>rs is a mistake”, he guarantees. “The fair is important in the sensethat it proposes a meeting point between the products and the tra<strong>de</strong>rs”. In<strong>de</strong>ed, afterhaving been at the MOA he is receiving more or<strong>de</strong>rs from the contacts he ma<strong>de</strong>there: “The fairs are a space of contact and opening”, he conclu<strong>de</strong>s.This does not mean that there has to be a <strong>de</strong>ep analysis of the results of the MOAfrom several different points of view through discussion among the different sectorsinvolved in or<strong>de</strong>r to improve the coming editions yet granting primacy to the permanenceof the event: “If the fair doesn’t happen we will no longer have a referent forthe situation of <strong>Galicia</strong>n crafts”.45

Replying to the proposal by the <strong>Galicia</strong>n Centre of Crafts and Design Foundation,I atten<strong>de</strong>d the MOA, the first Exhibition of <strong>Galicia</strong>n Crafts, whichwas held in La Corunna in February 2009. The fair was created with thefocus that many of the craft workers <strong>de</strong>dicated to tra<strong>de</strong> with shops, galleriesand large-scale sales establishments have been calling for over recentyears.Eighty-five craft workers accepted the challenge, although almost all ofus knew that this was a bold step, without doubt those of us who tra<strong>de</strong>dthrough other professionals <strong>de</strong>man<strong>de</strong>d and nee<strong>de</strong>d an event in which wecould reach our potential customer in a clear manner without being mixedup with other products that had nothing to do with the type of public that<strong>de</strong>als with handicraft works.Susana Aparicio OrtizCarrer Perill nº41 bajoBarcelonasussanglass@hotmail.com“In my personalexperience, theMOA shouldcontinue”Susana AparicioExhibitor (Barcelona)“The atmosphere was ‘sensational’. Despite the situation resulting from theeconomic crisis that is affecting Europe and that is provoking the closure of alarge number of workshops throughout the state, there were few long faces,and most of us knew how to fit into this reality that, on the other hand, weall knew”.The standard of the products presented by the participants was very high,and once again <strong>de</strong>monstrated that Spain has a healthy group of seriousprofessionals capable of competing on any market.The guest country at the fair was Switzerland, which impressed most of uswith its creativity and minimalism, and the Swiss craft workers took advantageof their stay to create links, to make contact with other craftspeople, tovisit workshops and to propose i<strong>de</strong>as for possible future projects.The MOA layout had a good interior distribution of the stands, which werevery <strong>de</strong>tailed, although no doubt if this layout is repeated at other eventsa different type of stands would have to be consi<strong>de</strong>red given that some ofthe participants did not find them suitable to their needs. Yet in general theywere well adapted to all the products shown.Many visitors, companions, politicians and institutions from different Spanishcities came to see the fair.Shop owners also came to see or to make requests from craftspeople withwhom they already worked. On Saturday afternoon and on Sunday onecould see consi<strong>de</strong>rable real interest among the people, with notebooks intheir hands, making notes and taking cards. What might become futurerequests is a usual practice by those who have shops, and more so now thatthey are selling almost day by day, as the sales in shops <strong>de</strong>velop. We’ve allbeen dragging our feet.In my personal experience the MOA should be continued, but it is importantfor more resources to be allocated to commercially attracting the professionalvisitor, given that even though the fair and the participants were ofan exceptional standard, its continuity will not be possible if there isn’t aneconomic movement to justify the effort and the investment both by the craftworkers and the <strong>Galicia</strong>n government. The craftsman has to sell in or<strong>de</strong>r togrow, in or<strong>de</strong>r to maintain jobs and to improve on a daily basis. This is theaim that has to be achieved.I believe that it is the time to make an effort if we want this mo<strong>de</strong>l that wehave wanted for so many years to prosper, and all pull together. Spain isone of the few countries in Europe nowadays that does not have a strongevent of this kind and which has effective results. I believe there is no shortageof will on the part of the crafts workers, associations and institutions.We have to keep on working.46

For several years Rosa Sega<strong>de</strong> has hea<strong>de</strong>d A Mouga, a shop specialisingin crafts, both traditional and more recent ones, and in which <strong>Galicia</strong>n craftwork occupies a privileged place. In her establishment one can find the mostvaried products ma<strong>de</strong> by the hands of our craft workers, ranging from potteryto avant-gar<strong>de</strong> jewellery, and including one of her specialties: traditionalcostume. Despite having a fluid relationship with the craft workers, an eventlike the <strong>Galicia</strong>n Craft Exhibition was an i<strong>de</strong>al place to measure the state ofproduction in the sector.OpinionWhat i<strong>de</strong>a did you have about the MOA at first?What I expected to find was basically <strong>Galicia</strong>n craft workers, and then whenI got there I was surprised to see people from other places, which I also thinkis a good i<strong>de</strong>a. But at the MOA I expected to find <strong>Galicia</strong>n craft workers withavant-gar<strong>de</strong> products, that was the i<strong>de</strong>a I had when I went to buy things formy shop. I didn’t have any preconceived i<strong>de</strong>a.And did it live up to your expectations?There was a little of everything. I already knew a lot of the craft workers, becauseas I am from here it is easier to get to know them than what is done in<strong>Galicia</strong>n crafts. T thought the fair was excellent, very well set up. And in<strong>de</strong>edI bought things I didn’t have.Do you think that this MOA, the <strong>Galicia</strong>n Craft Exhibition, isnecessary as a meeting point between the craft worker and theshop?“I believe that theMOA is the righttype of fair”Rosa Sega<strong>de</strong>Professional VisitorTo some extent, because the small craft workers usually come to the shopa lot. Then when they are established they logically visit fairs because theyhave access to a wi<strong>de</strong>r public. Being a shop we have the advantage that thesmaller craft workers who make a special product usually come to the shop toask if we are interested in it. So until now they have been supplying us. Evenso there are always unemployed people or those who work on a very smalllevel. I work with all kinds of craft items, I have works from other places, butI try to work within what I can with people from here. So it seems to me thata fair held here and with craft workers from here provi<strong>de</strong>s me with a greaterquantity of attractive products, of a certain standard and of a more avantgar<strong>de</strong>character than one sees here in <strong>Galicia</strong>. That’s what I was looking forat the MOA.And what did you think about the standard of the works?Generally good. Although in my case this didn’t surprise me because I alreadyknew the work of most of the craftsmen and women. But I believe thatthe people who came from abroad would find a really good level of craftwork.I discovered some firms that I really liked, and in the Swiss representationthere were some special and very striking works, it was a very pretty andimaginative craftwork. At the MOA there was a lot of choice. For examplethere were plate-makers with intricate works, although we don’t work withthem in the shop. There were many craft workers who had very pretty products,well-ma<strong>de</strong> and of high quality.A MougaRúa Xelmírez 26Santiago <strong>de</strong> CompostelaSo you would recommend other shops to visit it?Without any doubt. It seemed very well organised to me. One has to consi<strong>de</strong>rthat it was the first edition, and that these things usually improve: you realisewhat was lacking in the previous edition, and people already know the fair andturn up more. I mean that a first edition will always have fewer participants.Would you suggest any changes?Not really. I didn’t see anything lacking. I think it is the right type of fair.47

Makers of Harmony“The great artists are going back to the mostrudimentary things a priori, which means craftwork”Abe Rába<strong>de</strong>A tambourine with applications ma<strong>de</strong> of Swarovsky glass... forwhom? “The artists request it a lot, they have to stand out when theyare on stage”, according to the percussion craftsman Xosé ManuelSanín. And not only a question of aesthetics, but they also want agood instrument, and the music creators agree: the best are handma<strong>de</strong>. Although technology has been coming into the making of instruments,the craftsman’s knowledge, and above all his ear, are stillindispensable when the instruments are ma<strong>de</strong>. And who better to<strong>de</strong>fend this than their main users, the artists. Four of the names whoare most heard on the contemporary <strong>Galicia</strong>n scene: Nor<strong>de</strong>stinas,Bonovo, Nova Galega <strong>de</strong> Danza and Susana Seivane talk aboutthe presence of handma<strong>de</strong> crafts in their work.“Handicraft, not only on the level of making the instruments, buton other levels, goes alongsi<strong>de</strong> with music, opening up new marketsbeing very experimental and having a good standard”. GuadiGalego <strong>de</strong>votes his life to music, particularly traditional music, andhe knows full well the importance of the craftsman’s hand in makinga musical instrument, a close and inseparable relationship, thatprovokes and takes advantages of the <strong>de</strong>velopments in both directions.Nowadays, thanks to the time and worked being invested bymaster craftsmen, the chromatic scale that a set of bagpipes has ispractically complete. And this is achieved through that will that sooften appears in an implicit and organic manner in the craftsman’swork: that of seeking, experimenting and evolving.Nor<strong>de</strong>stinas is a project which is also given voice, besi<strong>de</strong>s GuadiGalego, by Ugia Pedreira, singing songs about the sea in therhythms of jazz, with the suggestive harmonies of Abe Rába<strong>de</strong>,who is convinced that the pianos that make the best sounds arema<strong>de</strong> by craftsmen. “The great artists, the good ones, are curiouslygoing back to the most rudimentary things a priori, which meanscraftwork, manual work. Among the great elite of the piano wefind those that are ma<strong>de</strong> by hand, the Bonendorfer, the Bechstein,the Steinway and Sons... Even though Yamaha is the most standardized,it always has a manual part to finish off the instrument”,48

ecause in processes like tuning the participation of the human factoris indispensable. The three members of Nor<strong>de</strong>stinas agree thatit is the name of the craftsman that is the guarantee of the product.For Galego, the musician “looks for the signature of a craftsman,whenever he has a set of bagpipes by so-and-so or a hurdy-gurdyby someone else, it is always different from the other one”.Nor<strong>de</strong>stinas, in their relationship with music, go beyond the purelyinstrumental. The set that accompanies their concerts is ma<strong>de</strong> by thecraftsman sculptor Caxigueiro from Mondoñedo, a relationship thatcomes from way back, when Ugía Pedreira ma<strong>de</strong> a soundtrack foran exhibition by the artist. In Pedreira’s opinion the true revolutionon the instrumental musical panorama lies in the hurdy-gurdy, andthe new craftsmen, who are making and selling more. It is an instrumentthat is the tip of the spear in Europe”, and he quotes performerslike Xermán Díaz or Óscar Fernán<strong>de</strong>z.After being a member of such well-known groups as Cempés andBonovo, this is this latest project by one of the greatest and mostactive <strong>Galicia</strong>n hurdy-gurdy players, Óscar Fernán<strong>de</strong>z, who formsthe group along with Pulpiño Viascón and Roberto Grandal. Theywork un<strong>de</strong>r the <strong>de</strong>signation electro-acoustic folk, which, more thanreferring to a musical style, talks about the mediums they use. “Theyare not two types of music, but this refers to the purely crafted toolsthat we use, ma<strong>de</strong> by hand, and other electric ones”, Fernán<strong>de</strong>z explains.Their instruments are classic, but with names: a midi hurdygurdy,an electro-acoustic accordion or even a musical saw. Tuning,as they call it.The question is that to find these instruments one has to go abroad,because in <strong>Galicia</strong>, for example, it is a long time since anyonema<strong>de</strong> accordions by hand, Roberto Grandal points out. “Hurdygurdies,yes. What happens is that they don’t make the type thatI use”, explains Óscar Fernán<strong>de</strong>z, for whom the spirit of <strong>Galicia</strong>ncraftwork lies in its own way of conceiving and producing the music,and it is recognizable in the sound. “In<strong>de</strong>ed, we produce in acompletely crafted recording studio”, he comments, given that theirfirst record, Bonovo, is an example of self-management in whichthey control all the processes.And they also agree on their investigating and experimental <strong>de</strong>sire,like the curious instrument that, using friction, Pulpiño Viascón managesto get a unique and spectacular sound out of it: the saw. Alarge saw that, as Roberto Grandal explains, “can just as easily cuta tree-trunk as make a melody”.They all share a concept and a way of creating with one of thedance companies that is most being talked about now, even outsi<strong>de</strong>of <strong>Galicia</strong>, Nova Galega <strong>de</strong> Danza, a solid and coherent initiativethat changes the usual face of this discipline in or<strong>de</strong>r to propose aformula in which the most traditional element is the essence of ourcontemporary condition. Their last show, Tradicción, is directed by50