Franziska Scholz, Yiya Chen, Lisa Lai-Shen Cheng, Vincent J. van ...

Franziska Scholz, Yiya Chen, Lisa Lai-Shen Cheng, Vincent J. van ...

Franziska Scholz, Yiya Chen, Lisa Lai-Shen Cheng, Vincent J. van ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

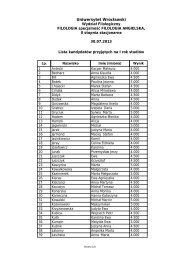

<strong>Franziska</strong> <strong>Scholz</strong>, <strong>Yiya</strong> <strong>Chen</strong>, <strong>Lisa</strong> <strong>Lai</strong>-<strong>Shen</strong> <strong>Chen</strong>g, <strong>Vincent</strong> J. <strong>van</strong> Heuven:Phrasing variation of verb-object constructions in Wenzhou ChineseDisyllabic verb-object constructions in Chinese can be either lexical compounds orphrasal concatenations of a monosyllabic verb and a monosyllabic object. The differenceis usually determined with respect to their lexicalization: If either of the parts ismorphologically bound or syntactically immobile, or if the combined meaning issemantically idiomatic, the resulting combination is treated as a lexicalized compound (Li& Thompson 1981). In the examples below, example (a) is lexicalized, since the object isa bound morpheme, and the whole disyllabic form is semantically idiomatic. Example (b)is non-lexicalized, since both syllables retain their individual meaning, can appear freely,and the object can be fronted.(1) Lexical status Example Gloss Predicted prosodya. lexicalized 洗 澡 ‘to wash’, ‘bath’ Tone Sandhitogether: ‘to shower’b. non-lexicalized 买 车 ‘to buy’, ‘car’ Phrasal prosodyThe southern Chinese dialect of Wenzhou represents an interesting test case forthe phonological realization of such verb-object constructions, since it treats lexicalcompounds different from phrases prosodically. If two syllables form a lexical word, theyare assigned phonological tone sandhi prosody. When two adjacent syllables are notlexicalized, they receive a phrasal prosody that largely retains the underlying tones of theindividual syllables (<strong>Chen</strong> 2000).Therefore, verb-object constructions in Wenzhou are predicted to systematicallyvary in their prosodic realization relative to their degree of lexicalization. This predictionwas tested with 10 young adult speakers of Wenzhou Chinese in three differentexperimental situations. The research question was whether the factors lexicalization,realization in isolation vs. in a carrier sentence, and presence vs. absence of regularcompounds within the experimental setup would influence the prosodic realization of theverb-object constructions.In the first experimental condition, three speakers (three repetitions each) werepresented with a list of 49 verb-object constructions, 17 of which (= 35%) were classifiedas non-lexicalized. The items were elicited in isolation, and their prosodic realizationswere expected to vary in correspondence with their degree of lexicalization.Degree ofProsodyLexicalization Phrasal Prosody Tone Sandhi Totalnon-lexicalized 139 (93.9%) 9 (6.1%) 148 (100.0%)lexicalized 177 (75.3%) 58 (24.7%) 235 (100.0%)Total 316 (82.5%) 67 (17.5%) 383 (100.0%)Table 1: Experimental condition (1): Verb-object constructions presented in isolation.

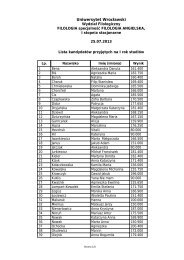

In accordance with the prediction, lexicalized examples received relatively more tonesandhi realizations than non-lexicalized examples. However, both lexical categories wererealized with phrasal prosody predominantly, in spite of the high amount of lexicalizedexamples in the test (65%). Therefore, although the difference between the prosodicrealization of lexicalized vs. non-lexicalized examples is stable, it is not as clear-cut asassumed in the literature.In the second and third experimental condition, eight different verb-objectconstructions were interspersed with disyllabic compound nouns, verbs, and adjectives.This was done to test whether the presence of regular compounds within the experiment,which unanimously received tone sandhi prosody, could bias the speakers towards usingmore tone sandhi prosody on the verb-object constructions. The amount of lexicalizedexamples among the verb-object examples was approximately equal to that in the firstexperimental condition (five of eight examples, or 62.5% of the cases lexicalized).Degree ofProsodyLexicalization Phrasal Prosody Tone Sandhi Totalnon-lexicalized 4 (22.2%) 14 (77.8%) 28 (100.0%)lexicalized 0 (0.0%) 29 (100.0%) 29 (100.0%)Total 4 (8.5%) 43 (91.5%) 47 (100.0%)Table 2: Experimental condition (2): Verb-object constructions interspersed with lexicalcompounds presented in isolation.For the second experimental condition, two speakers (three repetitions each) readout the verb-object constructions and lexical compound fillers in isolation. As shown intable 2, the pattern of prosodic realization for the verb-object constructions is invertedcompared to the first experiment: Most of the verb-object constructions in thisexperimental condition received tone sandhi prosody. Apparently, when lexicalcompounds are presented together with verb-object constructions, speakers prefer to usetone sandhi prosody on both, even though verb-object constructions in isolation exhibit apreference for phrasal prosody.The third condition tested the stability of this finding with 10 speakers (threerepetitions each) under the additional influence of a carrier sentence in which the lexicalcompounds and verb-object constructions were embedded. The results for the verb-objectconstructions mirror those of the second experimental condition (12.3% phrasal, 87.7%tone sandhi realizations). Therefore, presence vs. absence of a carrier sentence did notseem to influence the speakers’ choice for one prosodic pattern over the other.In conclusion, two of the three tested factors were found to influence thespeakers’ prosodic realization of verb-object constructions: The degree of lexicalization,and the presence of additional lexical compounds within the experimental situation. Ofthe two factors, presence vs. absence of lexicalization caused a stable 15-25% differencebetween the two categories in all three experimental conditions. However, the presencevs. absence of compound fillers biased the speakers towards tone sandhi vs. phrasalprosody to a much larger extent. Apparently, speakers took the liberty of adjusting theirprosodic realization of verb-object constructions to the prevailing surrounding prosodicpattern.

<strong>Chen</strong>, Matthew Y. 2000. Tone Sandhi. Patterns across Chinese dialects. (CambridgeStudies in Linguistics; 92). Cambridge: CUP.Li, Charles N. & Sandra A. Thompson. 1981. Mandarin Chinese. A Functional ReferenceGrammar. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.