Gender diversity and corporate performance - The Workplace ...

Gender diversity and corporate performance - The Workplace ...

Gender diversity and corporate performance - The Workplace ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

August 2012Research InstituteThought leadership from Credit Suisse Research<strong>and</strong> the world’s foremost experts<strong>Gender</strong> <strong>diversity</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>corporate</strong> <strong>performance</strong>

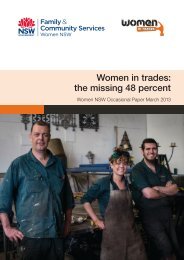

GenDeR DIveRSITY_2Contents3 Editorial4 <strong>Gender</strong> <strong>diversity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>corporate</strong>leadership6 Introduction9 <strong>Gender</strong> <strong>diversity</strong>: Latest data <strong>and</strong>recent trends12 Women on the board <strong>and</strong> stockmarket<strong>performance</strong>14 Women on the board <strong>and</strong> financial<strong>performance</strong>17 Rationalizing the link between<strong>performance</strong> <strong>and</strong> gender <strong>diversity</strong>20 <strong>The</strong> value of <strong>diversity</strong>Interview with ProfessorKatherine Phillips22 Achieving the targets –easier said than done!26 Barriers to change29 References31 Imprint/DisclaimerFor more information, please contact:Richard Kersley, Head of GlobalResearch Product, Credit SuisseInvestment Banking,richard.kersley@credit-suisse.comMichael O’Sullivan, Head of PortfolioStrategy & <strong>The</strong>matic Research, CreditSuisse Private Banking,michael.o’sullivan@credit-suisse.comCOveRPHOTO: THInKSTOCKPHOTOS.COM/DIGITal vISIOn. PHOTO: ISTOCKPHOTO.COM/MOODBOaRD_IMaGeS

GenDeR DIveRSITY_3Editorial<strong>The</strong>re has been considerable research on the impactof gender <strong>diversity</strong> on business. This report addressesone key question: does gender <strong>diversity</strong> within <strong>corporate</strong>management improve <strong>performance</strong>? While it isdifficult to demonstrate definitive proof, no one canargue that the results in this report are not striking. Intesting the <strong>performance</strong> of 2,360 companies globallyover the last six years, our analysis shows that itwould on average have been better to have investedin <strong>corporate</strong>s with women on their managementboards than in those without. We also find that companieswith one or more women on the board havedelivered higher average returns on equity, lowergearing, better average growth <strong>and</strong> higher price/bookvalue multiples over the course of the last six years.<strong>The</strong>re is not one easy answer to why gender <strong>diversity</strong>matters. While the facts <strong>and</strong> data we present areobjective, the interpretation of the results carriesmore than an element of subjectivity. We analyzed theacademic literature in this area <strong>and</strong> conducted severalinterviews with several experts on the topic. amongthese, we want to thank Professor Katherine Phillips(Paul Calello Professor of leadership <strong>and</strong> ethics atColumbia Business School) <strong>and</strong> Professor Iris Bohnet(academic Dean <strong>and</strong> Professor of Public Policy atthe Harvard Kennedy School <strong>and</strong> now a Director onthe Credit Suisse Group Board). With their help, weidentified seven possible explanations that, on ast<strong>and</strong>-alone basis or in some combination, helpexplain our findings.What is next? Several public bodies have becomemore vocal in supporting increased participation ofwomen in leadership roles in the <strong>corporate</strong> world.Some, like the norwegian government, have setm<strong>and</strong>atory targets; others have chosen to issue recommendationson board <strong>diversity</strong>. Ultimately, thetrend towards greater gender <strong>diversity</strong> within managementlooks set to continue – <strong>and</strong> going forwardwill provide another metric for those scrutinizing <strong>corporate</strong>governance. Our research suggests that aspecific consequence of greater board <strong>diversity</strong> forshareholders is one of reduced volatility – manifestedas enhanced stability in <strong>corporate</strong> <strong>performance</strong> <strong>and</strong> inshare price returns.Urs RohnerChairman of theBoard of DirectorsBrady W. DouganChief executive Officer

GenDeR DIveRSITY_4<strong>Gender</strong> <strong>diversity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>corporate</strong> leadership<strong>The</strong> impact of gender <strong>diversity</strong> on <strong>corporate</strong> leadership has beenwidely debated for many years. In our review of the topic, we lookat the impact from a global perspective by analyzing the <strong>performance</strong>of close to 2,400 companies with <strong>and</strong> without women boardmembers from 2005 onward.PHOTO: ISTOCKPHOTO.COM/MeDIaPHOTOS

GenDeR DIveRSITY_6Introduction<strong>Gender</strong> <strong>diversity</strong> within senior management teamshas become an increasingly topical issue for threerelated reasons. First, although the proportion ofwomen at board level generally remains very low, itis changing. Based on our numbers, only 41% ofMSCI aCWI stocks had any women on their boardsat the end of 2005, but this had increased to 59%by the end of 2011. Second, government interventionin this area has increased. In the past fiveyears, seven countries have passed legislationm<strong>and</strong>ating female board representation <strong>and</strong> eighthave set non-m<strong>and</strong>atory targets. Third – <strong>and</strong> mostinteresting – the debate around the topic hasshifted from an issue of fairness <strong>and</strong> equality to aquestion of superior <strong>performance</strong>. If gender <strong>diversity</strong>on the board implies a greater probability of<strong>corporate</strong> success, then it would make sense topursue such an objective, regardless of governmentdirectives.<strong>The</strong>re is a significant body of literature on thisissue; articles on the subject span several decades.Some suggest <strong>corporate</strong> <strong>performance</strong> benefitsfrom greater gender <strong>diversity</strong> at board level, whileothers suggest not.In the positive camp are the likes of McKinsey<strong>and</strong> Catalyst. Catalyst has shown that Fortune 500companies with more women on their boards tendto be more profitable. McKinsey showed that companieswith a higher proportion of women at boardlevel typically exhibited a higher degree of organization,above-average operating margins <strong>and</strong> highervaluations.Other studies, such as those conducted byadams <strong>and</strong> Ferreira or Farrell <strong>and</strong> Hersch, haveshown that there is no causation between greatergender <strong>diversity</strong> <strong>and</strong> improved profitability <strong>and</strong>stock price <strong>performance</strong>. Instead, the appointmentof more women to the board may be a signal thatthe company is already doing well, rather thanbeing a sign of better things to come.We note that much of the available literatureanalyzes the impact of women on the board withinone market or region. Usually, this is the USa oreurope or another isolated market. Hence, to addto the debate, we consider the issue from a globalperspective, looking at the impact on <strong>performance</strong>through time, both in terms of stock returns <strong>and</strong>commonly quoted financial metrics (ROe, ePSgrowth, gearing <strong>and</strong> P/Bv). Studying the data overtime, <strong>and</strong> encompassing periods of relative bull <strong>and</strong>bear markets, provides an opportunity to assessthe conditions under which female influence onleadership may deliver the best <strong>performance</strong> <strong>and</strong>highlights periods in which gender <strong>diversity</strong> on theboard may be less useful.Specifically, in our study we set out to answer fourbroad questions:1. What evidence is there to support the theorythat stock-market <strong>performance</strong> is enhanced byhaving a greater number of women on theboard?2. Is there any difference in the financial characteristicsof companies with a greater number ofwomen on the board?3. Why might it make a difference (better or worse)to have some gender <strong>diversity</strong> in company management?4. What factors might limit companies in increasingfemale representation?Some of the answers are obvious, some are lessso. For example, the extent to which subconsciousstereotyping can bias the selection process.Our key finding is that, in a like-for-like comparison,companies with at least one woman onthe board would have outperformed in terms ofshare price <strong>performance</strong>, those with no women onthe board over the course of the past six years.However, there is a clear split between relative<strong>performance</strong> in the 2005–07 period <strong>and</strong> <strong>performance</strong>post-2008. In the middle of the decadewhen economic growth was relatively robust, therewas little difference in share price <strong>performance</strong>between companies with or without women on theboard. almost all of the out<strong>performance</strong> in ourbacktest was delivered post-2008, since themacro environment deteriorated <strong>and</strong> volatilityincreased. In other words, stocks with greater gender<strong>diversity</strong> on their boards generally look defensive:they tend to perform best when markets arefalling, deliver higher average ROes through thecycle, exhibit less volatility in earnings <strong>and</strong> typicallyhave lower gearing ratios.We can therefore conclude that relative shareprice out<strong>performance</strong> of companies with women onthe board looks unlikely to be entirely consistent,but the evidence suggests that more balance onthe board brings less volatility <strong>and</strong> more balancethrough the cycle.PHOTO: ISTOCKPHOTO.COM/BIM

GenDeR DIveRSITY_7

GenDeR DIveRSITY_8PHOTO: ISTOCKPHOTO.COM

GenDeR DIveRSITY_9<strong>Gender</strong> <strong>diversity</strong>: Latest data <strong>and</strong> recent trendsPHOTO: ISTOCKPHOTO.COM/PIxDelUxeTo assess the impact of female board representation,we have compiled a database of the currentconstituents of the MSCI aC World index detailinghow many women were on the board of each constituentcompany at the end of each year since2005. This encompasses data for 2,360 companies<strong>and</strong> over 14,000 data points.Our key summary observations from this set ofdata are:1. Sectors that are closer to final consumerdem<strong>and</strong> have a higher proportion of women onthe board. Sectors closer to the bottom of thesupply chain tend to have a much lower proportionof women on the board.2. Certain regions (e.g. europe) <strong>and</strong> countries(e.g. norway) tend to have relatively high ratiosof women on the board, for others the numbersare extremely low (e.g. Korea).3. Larger companies are much more likely tohave women on the board than smaller companies.4. Over the past six years, the fastest rates ofchange in female representation have comefrom european companies.In Figure 1 we detail the proportion of companieswithin each sector that have zero, one, two orthree or more women on the board. Broadlyspeaking, sectors that are closer to final consumerdem<strong>and</strong> (for example, Healthcare <strong>and</strong> Financials)have a higher proportion of women at board level.Heavy industry <strong>and</strong> Information Technology (IT)have a much lower proportion of women boardmembers. More than 50% of the IT <strong>and</strong> Materialscompanies in our sample universe have no womenon the board.<strong>The</strong> dispersion in female representation is moresignificant at market <strong>and</strong> regional level than at sectorlevel. as we illustrate in Figure 2, 72% of thecompanies listed in emerging asia, within our sample,have no women on their boards compared toonly 16% of the companies listed in north america.<strong>The</strong> picture is amplified if we consider greaterdegrees of gender <strong>diversity</strong>. For instance, there is agreater proportion of european companies withthree or more female board members (27.6%) thanthere are european companies with no women onthe board (16.3%). Meanwhile in asia <strong>and</strong> latinamerica, the number of companies with three ormore women on the board is insignificant.Many of these differences reflect local legislation.various european governments have setm<strong>and</strong>atory or non-m<strong>and</strong>atory targets for femaleboard representation over the past five years <strong>and</strong>this has driven the numbers for the region tohigher levels. We look at this issue in more detailon page 25.Figure 1Proportion of companies in each sector split by numberof women on the board (end-2011)Source: Credit SuisseNumber of women on the board% in each sector 0 1 2 >=3 TotalHealthcareFinancialsUtilitiesConsumer DiscretionaryConsumer StaplesTelecommunication ServicesenergyIndustrialsMaterialsInformation Technology26.732.233.137.738.540.046.848.452.552.535.127.319.527.215.521.128.124.322.126.324.423.129.320.223.521.118.117.216.713.813.717.418.014.922.517.97.010.18.77.4100100100100100100100100100100Total 41.2 25.0 20.3 13.6 100Figure 2Proportion of companies in each region split by numberof women on the board (end-2011)Source: Credit SuisseNumber of women on the board% in each region 0 1 2 >=3 Totalnorth americaeuropeeMealatin americaDeveloped asiaemerging asia15.816.334.760.868.072.132.427.426.028.019.815.833.128.720.08.89.47.318.727.619.32.42.84.8100100100100100100Figure 3Average market cap (USD m) in each sector split bynumber of women on the boardSource: Credit SuisseNumber of women on the boardUSD m 0 1 2 >=3Consumer DiscretionaryConsumer StaplesenergyFinancialsHealthcareIndustrialsInformation TechnologyMaterialsTelecommunication ServicesUtilities8,45110,32014,0186,5866,2825,6497,8937,20514,4627,56113,1057,19627,94810,58612,6499,36323,8599,9877,9778,50711,94121,98429,46115,28224,49713,53724,94913,79831,73412,74317,43738,79033,00423,38255,12718,51247,98515,18632,69812,954Total 8,100 13,211 17,730 26,506

GenDeR DIveRSITY_10Figure 4Proportion of companies with one or more womenon the board (end-2005 vs. end-2011) by sectorSource: Credit Suisse80%70%60%50%40%30%20%10%0%2005Figure 5Proportion of companies with one or more womenon the board (end-2005 vs. end-2011) by regionSource: Credit Suisse90%80%70%60%50%40%30%20%10%0%2005ITMaterials2011Emerging AsiaIndustrialsDeveloped AsiaEnergyTelecommunicationServicesLatin AmericaConsumer StaplesConsumerDiscretionaryEMEAUtlitiesEuropeFinancialsHealthcareNorth AmericaTotalWe also note that the number of women on theboard typically rises with the size of the company.On average, it is the large cap, <strong>and</strong> higher profilecompanies that have added women at senior managementlevel. This holds true whether we categorizethe universe by sector or region. In Figure 3 wepresent the data aggregated by sector. On average,companies with three or more women on theboard have a market capitalization three timesgreater than that of companies with no womenboard members.<strong>The</strong> picture is changing, however. looking at thedata over the years we can see a clear trendtowards greater female board representation. at thesector level, the increase has been relatively uniformover the past six years. However, we note thatthe slowest rate of change has been in the asi<strong>and</strong>ominatedIT sector (there was only a 12 percentagepoint increase in IT companies promotingwomen to the board for the first time between 2005<strong>and</strong> 2011). Utilities <strong>and</strong> Financials have deliveredhigher than average female board appointments:there was a 20 percentage point increase in companieswithin each sector promoting at least onewoman to the board over the past six years.at the regional level, the fastest rate of changeover the past six years has been for european companies:just under 50% of european companies inour sample universe had one or more women onthe board at the end of 2005, but by the end of2011 this had increased to close to 84%. asianmarkets (both emerging <strong>and</strong> developed) have mostobviously lagged the trends in europe.<strong>The</strong> breakdown of the regional data into thecomponent markets (Figure 6) illustrates thedegree to which national cultures (<strong>and</strong> policies)influence the picture. <strong>The</strong> data suggest the Sc<strong>and</strong>inavianmarkets (where m<strong>and</strong>atory <strong>and</strong> non-m<strong>and</strong>atorytargets have been set) have the highest degreeof female representation at board level. Femaleboard representation looks low in Switzerl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong>Italy, compared with the other major european markets.Spain has seen the greatest improvementover the past six years: in 2005 only 22% of Spanishcompanies in the sample had one or more2011 women at board level; by the end of 2011 this hadincreased to 89%. Within australasia, female boardrepresentation is particularly low in Korea, Taiwan<strong>and</strong> Japan but much higher in new Zeal<strong>and</strong>, australia<strong>and</strong> Thail<strong>and</strong>. according to our numbers,China has seen the greatest improvement over thepast six years: only 6.5% of companies had anygender <strong>diversity</strong> at board level in 2005, but this hadincreased to 50% by the end of 2011.Within the eeMea markets, Israel <strong>and</strong> Southafrica st<strong>and</strong> out on the gender <strong>diversity</strong> front: wellover 90% of companies in our universe in bothmarkets have at least one woman on the board.

GenDeR DIveRSITY_11Figure 6Proportion of companies with one or more women on the board (end-2005 vs. end-2011) by marketSource: Credit Suisse% with 1 or more women on the board % change Number of companies2005 2011 2011 vs. 2005 in the sampleDeveloped Asia australia 60.9 88.2 27.3 68Hong Kong 28.8 51.6 22.9 93Japan 2.9 11.2 8.3 312new Zeal<strong>and</strong> 80.0 100.0 20.0 5Singapore 25.0 48.4 23.4 31Emerging Asia China 6.5 50.0 43.5 58India 30.4 46.5 16.0 71Indonesia 8.3 24.0 15.7 25Malaysia 4.3 42.9 38.5 42Philippines 58.8 38.9 -19.9 18South Korea 0.0 3.8 3.8 105Taiwan 4.3 9.2 4.9 98Thail<strong>and</strong> 44.4 80.0 35.6 20Europe austria 25.0 50.0 25.0 8Belgium 25.0 83.3 58.3 12Denmark 50.0 91.7 41.7 12Finl<strong>and</strong> 80.0 100.0 20.0 15France 47.8 97.1 49.3 70Germany 34.0 86.0 52.0 50Greece 25.0 75.0 50.0 4Irel<strong>and</strong> 33.3 33.3 0.0 3Italy 10.7 57.1 46.4 28luxembourg 33.3 66.7 33.3 3netherl<strong>and</strong>s 54.2 79.2 25.0 24norway 80.0 90.0 10.0 10Portugal 0.0 50.0 50.0 6Spain 22.2 88.9 66.7 27Sweden 97.0 100.0 3.0 33Switzerl<strong>and</strong> 39.5 65.8 26.3 38United Kingdom 62.3 84.9 22.6 106EEMEA Czech Republic 33.3 33.3 0.0 3egypt 10.0 50.0 40.0 10Hungary 25.0 0.0 -25.0 4Israel 100.0 100.0 0.0 11Morocco 0.0 0.0 0.0 3Pol<strong>and</strong> 25.0 60.0 35.0 20Russia 3.8 38.5 34.6 26South africa 86.0 95.9 9.9 49Turkey 30.0 50.0 20.0 24North America CanadaUnited States56.473.075.585.719.112.7102587Latin America Brazil 29.7 42.3 12.6 78Chile 11.1 15.8 4.7 19Colombia 50.0 60.0 10.0 5Mexico 31.8 45.5 13.6 22Peru 0.0 0.0 0.0 1Total 41.1 58.8 17.8 2,359

GenDeR DIveRSITY_12Women on the board <strong>and</strong> stock-market <strong>performance</strong>Figure 7Our headline result is that, over the past six years,Share price <strong>performance</strong> of all companiescompanies with at least some female board representation(with market cap > USD 10 bn) *outperformed those with no women onthe board in terms of share price <strong>performance</strong>.Source: Thomson Reuters, Credit Suisse* Calculated on a sector-neutral basisGetting to this result was not straightforward.180160<strong>The</strong>re is a bias from the skew in female representationtowards certain sectors (consumer-related),certain markets (europe) <strong>and</strong> towards large-cap140 stocks. Take the sector issue by way of example.<strong>The</strong> consumer staples sector ranks higher than120average in terms of female board representation,100but arguably the considerable share price out<strong>performance</strong>the sector has delivered over the past80few years has little to do with board composition60<strong>and</strong> much more to do with the very stable <strong>and</strong>Dec 05 Dec 06 Dec 07 Dec 08 Dec 09 Dec 10 Dec 11 defensive nature of its earnings in a world of considerableNo women on the board 1 or more women on the boardearnings uncertainty.Hence, in calculating the returns generated bycompanies with (a) one or more women on theFigure 8board compared with those with (b) no women onShare price <strong>performance</strong> of all companiesthe board, we have made three adjustments:(with market cap < USD 10 bn) *1. We look at <strong>performance</strong> from a sector-neutralstance. In other words, we have allocated the sameSource: Thomson Reuters, Credit Suisse* Calculated on a sector-neutral basissector weights in the calculations of both (a) <strong>and</strong>180160(b) in order to mitigate the impact of overall sector<strong>performance</strong>;2. We split the sample universe into two baskets:140one containing companies with market capitalizationgreater than USD 10 billion <strong>and</strong> one containing120companies with market capitalization less than100USD 10 billion. Hence, in broad terms, we are80aiming to compare women versus no women on theboard of large caps <strong>and</strong> separately, women versus60no women on the board of mid-to-small caps. InDec 05 Dec 06 Dec 07 Dec 08 Dec 09 Dec 10 Dec 11 this way, we can partially mitigate the survivor biasNo women on the board 1 or more women on the boardof small cap stocks in the construction of oursample universe; <strong>and</strong>3. We look at the returns generated (on a sectorneutralFigure 9basis) within each region as well as at theRelative share price <strong>performance</strong> of all companiesaggregate global level.(with market cap > USD 10 bn) *Figure 7 <strong>and</strong> Figure 8 illustrate the results forthe large-cap (greater than USD 10 billion) stocksSource: Thomson Reuters, Credit Suisse* Performance of stocks with some female board representation divided by the <strong>performance</strong> of stocks <strong>and</strong> for stocks of less than USD 10 billion in marketwith no women on the board, where all stocks have market capitalization greater than USD 10 bncapitalization, respectively, for the full global universe.140 1.30In both examples, the results demon-130 26% out<strong>performance</strong> over 6 years1.25 strate superior share price <strong>performance</strong> for120 1.20 the companies with one or more women on110 1.15 the board.100 1.10 Specifically, we find that for large-cap stocks90 1.05 (market cap greater than USD 10 billion), the companies80 1.00with women board members outperformed70 0.95 those without women board members by 26% over60 0.90 the past six years. For small-to-mid cap stocks, the50 0.85 basket of stocks with women on the board outperformedDec 05 Dec 06 Dec 07 Dec 08 Dec 09 Dec 10 Dec 11those without by 17% over the same period.MSCI AC World Rel. perf.: 1 or more vs. 0 women on the board (r.h.s.)However, the <strong>performance</strong> pattern is far from con

GenDeR DIveRSITY_13sistent over time. <strong>The</strong>re was little differentiation in<strong>performance</strong> during the stronger growth environmentthat characterized the 2005–07 period. <strong>The</strong>share price <strong>performance</strong> of the universe of companieswith women on the board really picked up withthe onset of the bear market in the second half of2008 <strong>and</strong> has been strong since then, as concernsover the global growth environment have continuedto weigh on market sentiment.<strong>The</strong> issue with our analysis is that while it is conductedon a sector-neutral basis <strong>and</strong> we have takenaccount of the size bias by splitting the universeinto big <strong>and</strong> smaller caps, our global portfolio ofcompanies with women on the board is still heavilyskewed towards european names <strong>and</strong> away fromasian ones. Hence, market sell-offs precipitated bythe macro crisis in europe were another significantinfluence on relative <strong>performance</strong> in our backtest.To isolate this effect, we have conducted the samesector-neutral analysis but looked at the returnsgenerated within each region, rather than just at aglobal level. Figure 11 <strong>and</strong> Figure 12 illustrate thepattern of returns generated within europe <strong>and</strong> theUSa along these lines.From this analysis, we can now see a muchclearer inverse correlation (–0.65 <strong>and</strong> –0.76 foreurope <strong>and</strong> the USa respectively) between therelative share price <strong>performance</strong> of companies withone or more women on the board compared withthose with no women on the board <strong>and</strong> the overallmarket.<strong>The</strong>re are two conclusions to be drawn from this:1. That stocks with a greater degree of genderdiversification appear to be relatively defensive innature; <strong>and</strong>2. That the out<strong>performance</strong> of stocks with womenon the board may not continue if the world shiftsback towards a more stable macro environment inwhich companies are rewarded for adopting moreaggressive growth strategies.Figure 10Relative share price <strong>performance</strong> of all companies(with market cap < USD 10 bn) *Source: Thomson Reuters, Credit Suisse* Performance of stocks with some female board representation divided by the <strong>performance</strong> of stockswith no women on the board, where all stocks have market capitalization less than USD 10 bn140 1.30130 1.25120 1.20110 17% out<strong>performance</strong> over 6 years1.15100 1.1090 1.0580 1.0070 0.9560 0.9050 0.85Dec 05 Dec 06 Dec 07 Dec 08 Dec 09 Dec 10 Dec 11MSCI AC WorldFigure 11Rel. perf.: 1 or more vs. 0 women on the board (r.h.s.)Share price relative <strong>performance</strong> of European stocks(with market cap > USD 10 bn) *Source: Thomson Reuters, Credit Suisse* Performance of european listed stocks with some female board representation divided by the <strong>performance</strong>of european listed stocks with no women on the board, where all stocks have market capitalization greaterthan USD 10 bn140 1.20130 1.15120 1.10110 1.05100 1.0090 0.9580 0.9070 0.8560 0.80Dec 05 Dec 06 Dec 07 Dec 08 Dec 09 Dec 10 Dec 11No women on the boardFigure 12Rel. perf.: 1 or more vs. 0 women on the board (r.h.s.)Share price relative <strong>performance</strong> of US stocks(with market cap > USD 10 bn) *Source: Thomson Reuters, Credit Suisse* Performance of US listed stocks with some female board representation divided by the <strong>performance</strong>of US listed stocks with no women on the board, where all stocks have market capitalization greaterthan USD 10 bn150 1.15140 1.10130 1.05120 1.00110 0.95100 0.9090 0.8580 0.8070 0.75Dec 05 Dec 06 Dec 07 Dec 08 Dec 09 Dec 10 Dec 11No women on the boardRel. perf.: 1 or more vs. 0 women on the board (r.h.s.)

GenDeR DIveRSITY_14Women on the board <strong>and</strong> financial <strong>performance</strong>Figure 13ROE: 0 vs. 1 or more women on the boardSource: Credit Suisse20%18%16%16%14%12%12%10%8%6%4%2%0%2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Avg0 women on the board 1 or more women on the boardWe have further used our dataset to consider theaverage financial metrics of companies with womenon the board versus those without. In Figure 13 toFigure 16, we illustrate the four key findings:1. Higher return on equity (ROE): <strong>The</strong> averageROe of companies with at least one woman on theboard over the past six years is 16%; 4 percentagepoints higher than the average ROe of companieswith no female board representation (12%).2. Lower gearing: net debt to equity of companieswith no women on the board averaged 50%over the past six years; those with one or morehave a marginally lower average, at 48%. However,we note the much faster reduction in gearing thattook place at companies with women on the boardas the financial crisis <strong>and</strong> global slowdown unfolded.3. Higher price/book value (P/BV) multiples:In line with higher average ROes, aggregate P/Bvfor companies with women on the board (2.4x) ison average a third higher than the ratio for thosewith no women on the board (1.8x).4. Better average growth: net income growth forcompanies with women on the board has averaged14% over the past six years compared to 10% forthose with no female board representation.Further analysis shows that these results are alsoseen at a regional <strong>and</strong> sector level.This financial <strong>performance</strong> is corroborated byother research. Catalyst Inc (2007) showed thatFortune 500 companies with more women on theirboards were found to outperform their rivals with

GenDeR DIveRSITY_15PHOTO: ISTOCKPHOTO.COM/KUPICOOreturn on sales 4 percentage points higher (13.7%versus 9.7% for the top <strong>and</strong> bottom quartilesranked by the number of women on the board),<strong>and</strong> return on equity 4.8 percentage points higher(13.9% versus 9.1% for the top <strong>and</strong> bottom quartilesrespectively). Similarly, using data on 1,500US companies from 1992 to 2006, Deszõ <strong>and</strong>Ross demonstrated the “strong positive associationbetween Tobin’s Q, return on assets, <strong>and</strong> return onequity, on the one h<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> the participation rate(of female top management) on the other.”Ultimately, these results support the hypothesisthat companies with a greater degree of genderdiversification at board level are relativelydefensive.as the european debt crisis has unfolded, thebest performers within the stock market havebeen those with stronger balance sheets (lowernet debt to equity), higher average ROes (oftensynonymous with higher cash-flow generation)<strong>and</strong> less volatility in the earnings cycle. In turn, ouranalysis shows that these characteristics are likelyto be associated with some (rather than no)women on the board.But, is it having a woman at board level thatmakes the difference to the structure of the businessor would that business have delivered thesame result regardless? none of our analysisproves causality; we are simply observing thefacts. In the discussion below, we consider thelinks that may or may not be driving the two sidesof the argument.Figure 14Net debt to equity: 0 vs. 1 or more women on the boardSource: Credit Suisse65%60%55%50%45%40%35%0 women on the boardFigure 15200520062007200820091 or more women on the board2010P/BV: 0 vs. 1 or more women on the boardSource: Credit Suisse3.53.52.52.01.51.0201150%48%Avg.1.82.40.502005200620072008200920102011Avg.0 women on the board1 or more women on the boardFigure 16Net income growth: 0 vs. 1 or more women on the boardSource: Credit Suisse60%40%20%0%-20%-40%-60%2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Avg.0 women on the board 1 or more women on the board

GenDeR DIveRSITY_17Rationalizing the link between<strong>performance</strong> <strong>and</strong> gender <strong>diversity</strong>PHOTO: ISTOCKPHOTO.COM/MaRCUSPHOTO1We can identify seven key reasons why greatergender <strong>diversity</strong> could be correlated with stronger<strong>corporate</strong> <strong>performance</strong>:1. A signal of a better company<strong>The</strong>re is a significant body of research that supportsthe idea that there is no causation betweengreater gender <strong>diversity</strong> <strong>and</strong> improved profitability<strong>and</strong> stock price <strong>performance</strong>. Instead the link maybe the positive signal that is sent to the market bythe appointment of more women: first because itmay signal greater focus on <strong>corporate</strong> governance<strong>and</strong> second because it is a sign that the company isalready doing well.adams <strong>and</strong> Ferreira (2009) looked at the impactof greater gender <strong>diversity</strong> on 1,939 US stocksbetween 1996 <strong>and</strong> 2003. On the face of it, theirdata showed positive gender <strong>diversity</strong> effects.However, using two different techniques to h<strong>and</strong>lereverse causation, they found statistically significantnegative effects on profits <strong>and</strong> stock value followingthe appointment of women to the board.Farrell <strong>and</strong> Hersch looked at 300 Fortune 500companies between 1990 <strong>and</strong> 1999 <strong>and</strong> showedthat firms with strong profits (ROa) are more likelyto appoint female directors but that female directorsdo not affect subsequent <strong>performance</strong>.<strong>The</strong> significant size bias that we found in ourown analysis of the MSCI aCWI universe also supportsthe idea that it is mostly the larger companiesthat, to some extent by definition, have alreadyperformed well, that are more likely to appointfemale board representatives. However, the strongout<strong>performance</strong> of companies with women on theboard, even in an exclusive comparison of thelarge caps, suggests there may be other facets tothe relationship.2. Greater effort across the boardOther evidence suggests that greater team <strong>diversity</strong>(including gender <strong>diversity</strong>) can lead to betteraverage <strong>performance</strong>. Professor Katherine Phillips(Paul Calello Professor of leadership <strong>and</strong> ethics atColumbia University) <strong>and</strong> her colleagues have studiedthe impact of greater <strong>diversity</strong> in team exercises<strong>and</strong> found that (a) individuals are, on average, likelyto do more preparation for any exercise that theyknow is going to involve working with a diverserather than a homogenous group; (b) that a widerrange of available data inputs are likely to bedebated in a diverse rather than a homogenoussetting; <strong>and</strong> (c) that the diverse group, in the end,is more likely to generate the correct answer to aparticular problem than is the case for the homogenousgroup. In conclusion, it is not necessarily the<strong>performance</strong> of the minority individuals that haveenhanced the result. Rather, it is the fact that themajority group improves its own <strong>performance</strong> inresponse to minority involvement. Simply put,nobody wants to look bad in front of a stranger.Hence, the greater the effort <strong>and</strong> attention todetail, the better average outcome in a morediverse environment. In the interview on page 20,we discuss these findings <strong>and</strong> other work in moredetail with Professor Phillips.In another fascinating study, Woolley et al(2010) provided evidence that the collective intelligenceof a group was not mostly determined by theaverage or maximum intelligence of the individualswithin the group but was better explained by thestyle <strong>and</strong> type of interaction between the groupmembers. Specifically, the authors showed that thecollective group intelligence was higher when (a)the social sensitivity of the individual group memberswas higher; (b) where there was a more evendistribution in the conversation between individualgroup members (rather than having the conversationdominated by one or two people); <strong>and</strong> (c) whenthere were more women in the group. <strong>The</strong> threeexplanations aren’t mutually exclusive: specifically,this test <strong>and</strong> other work has shown that women aretypically more socially sensitive (identified as betterat reading other people’s thoughts) than men.Hence, by virtue of having a greater proportion ofwomen in the mix, the social sensitivity of the groupis naturally likely to be higher.In other words the message is that, on average,most individuals in a working group will have somethingto offer (information, context, experience,processing powers) <strong>and</strong> provided each member ofthe group is given a chance to share their knowledge,the outcome for the team is likely to begreater than the sum of the parts. In practicalterms, the key takeaways are (1) good managementshould allow group members a chance tovoice their ideas to the rest of the team; <strong>and</strong> (2)gender <strong>diversity</strong> may be one way of skewing thesample in favor of this optimal outcome. From a<strong>corporate</strong> perspective, this also has to be the outcomethat is most likely to be aligned with maximizingprofit. By definition, profit is the economicvalue-added generated by combining various inputs

GenDeR DIveRSITY_18at cost. If the team result is better than the sum ofthe individual inputs, then it st<strong>and</strong>s to reason thatthe team has added value.<strong>The</strong> drawback in these examples (even in thesimulated situations of the laboratory) is that <strong>diversity</strong>may bring greater tension <strong>and</strong> conflict to thedecision-making process. Phillips et al showed thateven though the diverse groups were more likely toproduce a better result than the homogenous teams,their confidence in that result was lower <strong>and</strong> theworking environment was perceived to be more difficult.Indeed, other studies (Jackson et al) haveshown that the effects of conflict, poor communication<strong>and</strong> distrust can outweigh the potential positivesbrought on by different points of view. Ultimately,this is the challenge for management: to harness thepositives of <strong>diversity</strong> while avoiding the pitfalls.3. A better mix of leadership skillsMcKinsey has looked at the impact of greater gender<strong>diversity</strong> in the workplace in a series of reportsproduced over the last five years. In “Women Matter2” produced in 2008, they highlighted the differencesin male <strong>and</strong> female leadership styles. <strong>The</strong>crux of the argument was that there are nine keycriteria that, on average, define any good leader.Interestingly, women apply five of these nine leadershipbehaviors more frequently than men. Forinstance, women were found to be particularly goodat defining responsibilities clearly as well as beingstrong on mentoring <strong>and</strong> coaching employees. Menwere much better at taking individual decisions <strong>and</strong>then corrective action should things go awry. Hence,the idea that a degree of gender <strong>diversity</strong> at theboard level would foster a better balance in leadershipskills within the company may hold merit.naSa has completed various studies on theimpact of mixed gender crews. Similar to the McKinseyconclusions, women’s leadership styles havebeen characterized by task orientation, mentoringothers, <strong>and</strong> concern with the needs of others. allmaleexpeditions, on the other h<strong>and</strong>, have beencharacterized by competitiveness <strong>and</strong> little sharingof personal concerns. according to naSa, crewmembers have reported a general sense of “calmermissions” with women on board. Plus, 75% ofmale crew members also noted a reduction in rudebehavior <strong>and</strong> improved cleanliness (no bad thingwhen packed into a confined space for a longperiod of time.)4. Access to a wider pool of talentacross the majority of markets, women nowaccount for the greater proportion of graduates. aswe illustrate in Figure 17, data from UneSCOshow that by 2010, the proportion of female graduatesacross the world came to a median average of54%. This compares with a median average of51% female graduates in 2000. <strong>The</strong> trend towardsan even greater proportion of female graduateslooks set to continue if female success at primary<strong>and</strong> secondary school level is any guide. Data fromthe UK show that, in the national examinations(GSCes) taken by the majority of 16-year-old studentsin 2011, 26.5% of girls achieved at least oneof the top two grades whereas only 19.8% of boysachieved a top grade. Similar trends have been witnessedacross much of the Western world, whereschool retention rates have moved higher for girlsthan boys over the course of the last ten years.Hence, any company that achieves greater gender<strong>diversity</strong> is more likely to be able to tap into thewidest possible pool of talent implicit in these graduationstatistics. We note that the statistics haven’talways been skewed towards higher female grades.If the average board member is 50 years old, it isarguably more relevant to consider the graduationrates of 25–30 years ago (i.e. 1982 to 1987).However, as an explanation for weak gender <strong>diversity</strong>in the boardroom now, it is far from conclusive.according to UneSCO, male <strong>and</strong> female tertiarygraduation rates for north america <strong>and</strong> Westerneurope hit parity in the early 1980s <strong>and</strong> have continuedto move up in favor of higher female graduationrates since.5. A better reflection of the consumerdecision-makerIf we assume that women are, on average, likely tobe more responsible for household spending decisions,it could follow that a <strong>corporate</strong> board withfemale representation may enhance the underst<strong>and</strong>ingof customer preferences. according to abook published by Boston Consulting Group in2010, 73% of US household spending decisionsare controlled by women.not surprisingly, consumer-facing industriesalready rank among those with the greater proportionof women on the board. Basic materials <strong>and</strong>industrial companies rank among the lowest interms of female board representation.6. Improved <strong>corporate</strong> governanceFollowing the sc<strong>and</strong>als at several large <strong>corporate</strong>sin the late 1990s, the Sarbanes-Oxley act of 2002in the USa <strong>and</strong> the Higgs Review of CorporateGovernance in 2003 in the UK called for significantchanges to the composition of <strong>corporate</strong> boards.Both called for greater balance on the board to offsetthe relative lack of independent advice <strong>and</strong> toreduce the homogeneity of the directors.<strong>The</strong>re is unusually strong consensus within academicresearch that a greater number of women onthe board improves <strong>performance</strong> on <strong>corporate</strong> <strong>and</strong>social governance metrics. a study of Canadiancompanies (listed <strong>and</strong> unlisted) by Brown <strong>and</strong>anastasopoulos in 2002 entitled not Just the RightThing, but the “Bright” Thing, showed that boardswith three or more women performed much betterin terms of governance than companies with all

GenDeR DIveRSITY_19male boards. <strong>The</strong> study also found that the more Figure 17gender-diverse boards were more likely to focus on % of female graduates vs. GDP per capitaclear communication to employees, to prioritize Source: UneSCO, IMF, Credit Suissecustomer satisfaction, <strong>and</strong> to consider <strong>diversity</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>corporate</strong> social responsibility. More recent60000 GDP per capita (USD, PPP terms, 2010)Median = 54%research (2010) conducted by Harvard BusinessSingaporeSchool demonstrated similar results. 50000 Norwayadams <strong>and</strong> Ferreira also suggest that genderUSA<strong>diversity</strong> improves the <strong>performance</strong> of firms withweak governance but, on the downside, they point40000out that for firms where governance is alreadyUK Icel<strong>and</strong>JapanKoreastrong, greater gender <strong>diversity</strong> leads to “over-mon 30000Italyitoring” which interferes with efficient management<strong>and</strong> could lead to reduced profits <strong>and</strong> adverse stock20000price movements.as with everything, it seems to be a question ofTurkey10 000achieving the right balance.7. Risk aversion 0ChadBarbadosIndia China Guyana0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80%In research published in 2001, Odean <strong>and</strong> Barbe r% of female graduates (2010)showed that women tended to be much more risk-averse investors than men. Felton et al (2003)demonstrated that particularly optimistic men addedFigure 18to investment volatility: their portfolio <strong>performance</strong>Performance of European stocks with low gearing relativewas more likely to be extreme, whether great orto those with high gearingextremely poor. Meanwhile, the same result did notSource: Credit Suissehold true for women: there was no difference ininvestment style between more or less optimistic180women. Women just remained more risk averseregardless of their outlook.170Other research corroborates these conclusions.160a report compiled by Professor nick Wilson atleeds University Business School showed that150having at least one female director on the board140appears to reduce a company’s likelihood o fbecoming bankrupt by 20%, <strong>and</strong> that having two or130three female directors lowered the likelihood of120bankruptcy even further. Professor Wilson went onto state that “the negative correlation between110female directors <strong>and</strong> insolvency risk appears tohold good, irrespective of size, sector <strong>and</strong> owner100ship, for established companies as well as for newly90in<strong>corporate</strong>d companies.” 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013Our own analysis of the MSCI aC World con Europe: Stock <strong>performance</strong> of low-geared relative to high-geared stocksstituents showed that companies with women atboard level are more likely to have lower levels ofgearing than their peer group where there are nowomen on the board. We note that lower relativedebt levels have been a useful determinant ofequity market out<strong>performance</strong> over the last fouryears. as we illustrate in Figure 18, lower gearinghas delivered average out<strong>performance</strong> of 2.5% perannum over the last 20 years <strong>and</strong> 6.5% per annumover the last four years (within european listedequities). It is far from a consistent determinant of<strong>performance</strong>: in periods of rapid economic expansion <strong>and</strong> equity bull markets, low gearing is oftenan underperforming style. nevertheless, on average, the style has worked well <strong>and</strong> the inverse correlation between female management <strong>and</strong> riskaversion (or debt) is notable.

GenDeR DIveRSITY_20<strong>The</strong> value of <strong>diversity</strong>Interview with Professor Katherine Phillips, Paul Calello Professorof leadership <strong>and</strong> ethics, Columbia Business School, new YorkResearch Institute: Could you startby summarizing your principle fieldof research?Katherine Phillips: I am basically asocial psychologist by training. My PhDwas in Organizational Behavior <strong>and</strong> thework that I do focuses mainly on theissues of <strong>diversity</strong> in the workplace.Specifically, I look at how <strong>diversity</strong>influences team decision-making <strong>and</strong>organizational outcomes.What kind of data do you look at<strong>and</strong> collect in order to study theimpact of <strong>diversity</strong>?Katherine Phillips: Data sources inthis field have evolved over time. WhenI first started doing research on <strong>diversity</strong>,a lot of the work was based onsurveys completed by employees withinan organization. However, this hassince transitioned into experimentalmethodologies in a controlled environment.For example, we may collectdata from a series of experiments in aclassroom where we control the flow ofinformation to a group (or to individualswithin that group). In a controlled environmentsuch as this we can easilyalter the degree of <strong>diversity</strong> or homogeneity<strong>and</strong> we can tailor the test so thatthere is a right answer, which gives usan opportunity to quantify the effectivenessof the team.From a team perspective, what arethe main positives <strong>and</strong> negatives of<strong>diversity</strong>?Katherine Phillips: <strong>The</strong> main benefitof <strong>diversity</strong> is often assumed to be theimpact of the different perspectivesbrought to the table by the minoritygroup. <strong>The</strong> work that we have donesuggests this is far from the only benefit.We find that <strong>diversity</strong> really changesthe experience of all the people in thegroup. We find that people who are inthe social majority will actually thinkmuch more critically about the problemsthat they’re working on whenthey’re in a diverse group. In a diverseenvironment, individuals expect thereto be differences in perspectives, theyrecognize that those perspectivesshould exist, <strong>and</strong> they work harder toassimilate different ideas. On average,our studies show that the results generatedby the diverse teams are betterthan they are for the homogenousgroups.<strong>The</strong> downside to <strong>diversity</strong> is the feelingof greater conflict <strong>and</strong> tensionwithin the team. It’s not obvious at all tothe diverse team that they might comeout with a better result but they doknow that they are working hard <strong>and</strong>that assimilating conflicting viewpointscan be an uncomfortable experience.This typically undermines the confidencethat diverse teams have in thequality of their results.Will diverse groups that initiallywork badly (or think that they workbadly) together improve with time?Katherine Phillips: Yes, that is thecase. Some interesting work done byWatson, Kumar, <strong>and</strong> Michaelson hasshown that, although diverse groupsmight initially start off underperforming,over time their relative <strong>performance</strong>will probably exceed that of thehomogenous groups. a key variablehere is management feedback. Ifmanagement supports these diversegroups <strong>and</strong> encourages them to staytogether then there is a much higherprobability of success. Given the senseof greater conflict <strong>and</strong> stress in themore diverse setting, the initial messagefrom the team back to managementis unlikely to be that positive.If leadership allows this feedback todominate their judgment it is possiblethat <strong>diversity</strong> will be ab<strong>and</strong>oned beforeany positives can be reaped. Hence,the importance for leaders to stay thecourse <strong>and</strong> recognize that <strong>diversity</strong>should pay off over time.Does greater <strong>diversity</strong> always givepositive results?Katherine Phillips: My work is basicallyfocused on situations where peoplehave to learn from one another,where they will benefit from sharinginformation, where some creativity isrequired <strong>and</strong> where the problems thatthey’re trying to solve are complexenough. In these cases <strong>diversity</strong> is typicallybeneficial. In situations where youhave routine tasks <strong>and</strong> limited complexity,the benefits of <strong>diversity</strong> are likelyto be more limited.However, there is also the questionof making sure that your company hasaccess to the best possible talent.Given trends in globalization, immigration<strong>and</strong> demographics, the compositionof the work force is likely to look verydifferent in the long run. Greater <strong>diversity</strong>suggests a change in the workingenvironment in order to adapt to theneeds of different people. Companiesthat can do this better are more likely toattract the best talent, no matter whothat talent is. <strong>and</strong> that should be astrategic advantage for that company.Is gender <strong>diversity</strong> likely to be moreor less successful than other sortsof <strong>diversity</strong>?Katherine Phillips: Interestingly, theliterature doesn’t suggest that gender<strong>diversity</strong> is any more likely to be successfulthan any other type of <strong>diversity</strong>.<strong>The</strong> issues are two-fold: (1) a woman’sstatus is often perceived as lower thanthat of a man <strong>and</strong> hence she isn’tgiven the equal footing that we havefound to be a key ingredient in achievingsuccess through <strong>diversity</strong>; <strong>and</strong> (2)there is a significant body of evidencethat shows that women don’t speak

GenDeR DIveRSITY_21PHOTO: naTHan ManDellProfessor Katherine W. Phillips joined the faculty at Columbia Business School as the inauguralPaul Calello Professor of leadership <strong>and</strong> ethics in 2011. She has a PhD in OrganizationalBehavior from Stanford University's Graduate School of Business. She has published considerableresearch on issues of information sharing, <strong>diversity</strong>, status, minority influence, decisionmaking,<strong>and</strong> <strong>performance</strong> in work groups, <strong>and</strong> is the recipient of numerous professional awards,including recognition from the International association of Conflict Management, <strong>and</strong> the<strong>Gender</strong>, Diversity <strong>and</strong> Organizations Division of the academy of Management.up as much as men do in discussions,which means they are less likely tocause conflict but also means thedifferences in perspectives aren’t asreadily available to the other membersof the team either.From our own tests, the resultsshow that companies with greatergender <strong>diversity</strong> at the board levelperform better during times ofeconomic stress. Is risk aversion,driven by the female bias on theboard, the driving factor here?Katherine Phillips: Yes, recentresearch completed by Faccio, Marchica<strong>and</strong> Mura supports the resultsthat you have collected. <strong>The</strong>ir studyshows that CeO gender helps explain<strong>corporate</strong> decision making; that firmsrun by female CeOs have lower leverage,less volatile earnings <strong>and</strong> a higherchance of survival than firms run bymale CeOs. Other work conducted byJohn Coates at Cambridge Universityhas shown that not only do testosteronelevels increase with success butthat higher testosterone increases thetolerance for risk. arguably these traitshave exacerbated the degree of boom<strong>and</strong> bust in the markets. Given thatwomen <strong>and</strong> older men typically havemuch lower levels of testosterone, theirinfluence is likely to lend more balanceto the situation <strong>and</strong> reduce the degreeof risk taking.However, although some of the benefitsof greater <strong>diversity</strong> in leadershipmay be more obvious now at a time ofrelative economic stress, we shouldn’tconclude <strong>diversity</strong> is not necessarywhen the situation reverses. It’s reallyabout getting a balance in the room, togive the team the flexibility to respondappropriately depending upon theexternal environment.Can the benefits of <strong>diversity</strong> beachieved through quotas?Katherine Phillips: I actually believethat changing organizations <strong>and</strong> changingrepresentation in organizationssometimes does require something likea quota. In the short term this maycome with potentially negative sideeffects<strong>and</strong> it may appear that <strong>diversity</strong>is detrimental to <strong>performance</strong>. However,the benefits to <strong>diversity</strong> are reallydelivered over the longer term <strong>and</strong> ifsetting quotas is the only way to deliverchange then it may be a necessary <strong>and</strong>justifiable strategy.<strong>The</strong> lessons from affirmative actionare interesting in this respect. In hindsight,I think that affirmative action hasserved a very important role in openinga door to let people in but the responsibilityfor creating an equal playing fieldfor all does not stop there. let’s takeexperience as an example; of coursethe person with 20 years of experiencerelative to the person with no experienceis going to be better at a givenjob, but that’s not to say that peoplewith no experience (from the minoritygroup) cannot be equally competent ifgiven the same opportunities. <strong>and</strong> so Istrongly believe that quotas do serve animportant purpose, <strong>and</strong> that as thedoors are opened <strong>and</strong> greater <strong>diversity</strong>is allowed into the room, some of thebenefits will come through.Do you get the sense that the rateof change in <strong>diversity</strong> is increasing?Katherine Phillips: Many models ofchange show that there is a tippingpoint at which an idea, a trend or afashion can become suddenly ubiquitous.I get the sense that we are gettingclose to a tipping point over the issue of<strong>diversity</strong>. For large US <strong>corporate</strong>s, it isalmost out of step if you aren’t thinkingabout <strong>diversity</strong> issues. That’s not to saythat every company will join in the trend(some people never see that popularmovie, right?) but on average momentumappears to be building in favor ofgreater <strong>diversity</strong> generally, includinggreater gender <strong>diversity</strong>.

GenDeR DIveRSITY_22Achieving the targets – easier said than done! Figure 19Two scenarios for the working age population in EuropeSource: World Bank, US Census Bureau, Credit Suisse115 Total participation of working age population (millions)1101051009590Down 5% by 2050 vs. 2011Down 14% by 2050 vs. 20111990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050Assuming female participation rate is unchangedAssuming female participation rises to the male equivalentBeyond the potential positive implications of greaterfemale representation at the micro level, there arealso major macro implications of greater femaleparticipation. Greater female inclusion in the workplaceis a potential solution to the growing skillshortages faced by much of the Western world asworking age populations decline.In Figure 19, we illustrate the problem foreurope. <strong>The</strong> working age population is forecast todecline by 2.2% over the next ten years <strong>and</strong> 14%by 2050 (based on forecasts from the US CensusBureau). However, if the female participation ratefor europe gradually rises from an average 51% (in2010) to the male equivalent (65%) over the next40 years, then the european working age populationwould increase by 0.6% over the next tenyears <strong>and</strong> only decline by 4.7% by 2050.In Figure 20, we look at the position for individualmarkets across the world. <strong>The</strong> greatest differentialsin male <strong>and</strong> female participation rates are recordedin the north african <strong>and</strong> Middle eastern markets.PHOTO: KeYSTOne/PICTURe allIanCe/CUlTURa RM HOWaRD KInGSnORTH

GenDeR DIveRSITY_23<strong>The</strong> data for India also suggest a considerable gapbetween male (81%) <strong>and</strong> female (29%) participationrates. However, the incentive to raise femaleparticipation rates is arguably greatest in coreeurope, eastern europe <strong>and</strong> Japan, where forecastgrowth rates in working age population are weakest.It is perhaps not surprising that various europeanmarkets have taken relatively decisive actionto raise the profile of women in business, includingtheir representation at board level. <strong>The</strong> quota systemset by norway is probably one of the mostextreme measures undertaken. However, despitethe demographic pressures, Japan appears to havedone relatively little to promote female representationat board level according to the data.<strong>The</strong> targetsPublic <strong>and</strong> private policies aimed at raising the profileof women in the workplace <strong>and</strong> on the boardhave become more wide-ranging over the last fiveFigure 20Growth in working age population vs. the difference inmale <strong>and</strong> female participation ratesSource: World Bank, US Census Bureau, Credit Suisse60 Difference between male <strong>and</strong> female participation rates (% pts.)5040302010An obvious incentive toaddress female roles in theworkplaceITAJAPCZKRUSPOLHUN GERKORCHITHAUSARGCHLBRAAUSMORTURMEXIDO0-15% -10% -5% 0 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30%COLISRINDPEREGYMALVENForecast change in working age population (2022 vs. 2012)PHI

years. Demographic concerns, renewed focus on<strong>corporate</strong> governance issues in the wake of thefinancial crisis, as well as the debate over thepotential positives brought about by greater diversificationhave increased the focus on female boardrepresentation.a full range of solutions has been trialed acrossdifferent markets. norway has taken coerciveaction, the USa <strong>and</strong> Canada have encouraged voluntarycommitments, the UK has adopted a collaborativeapproach. Progress has been similarlyvaried. <strong>The</strong> Sc<strong>and</strong>inavian markets have deliveredsignificantly higher female board representation butother research suggests that forcing the issue viaquotas has been to the detriment of morale, theworking environment <strong>and</strong> potentially profitability.Meanwhile, progress in the southern europeanmarkets has been limited.In the table on the following page, we summarize thevarious measures that have been adopted acrossdifferent markets <strong>and</strong> the latest available numberson progress. It is striking that so many countries aretaking some kind of a stance on female board representation.By our calculations, seven countries havealready passed legislation incorporating m<strong>and</strong>atorytargets <strong>and</strong> a further eight countries have non-m<strong>and</strong>atorytargets. Of the major world economies, thereare still some notable exceptions to this trend (suchas Switzerl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> some of the larger asian markets).However, even in China the profile of womenin leadership roles is probably on the ascendancy:Credit Suisse expects a woman to be elected to thepowerful nine-man St<strong>and</strong>ing Committee of the Politburotowards the end of 2012. This would be thefirst time in its history that a woman has beenappointed to the St<strong>and</strong>ing Committee.PHOTO: KeYSTOne/PICTURe allIanCe/CUlTURa RM aDRIan WeInBReCHT

GenDeR DIveRSITY_25Figure 21Policies <strong>and</strong> progress in female board representationSource: Credit SuisseMarket Policy ProgressAustraliaAustriaBelgiumCanadaDenmarkEUFinl<strong>and</strong>FranceGermanyIcel<strong>and</strong>IndiaItalyMalaysiaNetherl<strong>and</strong>sNorwayPol<strong>and</strong>South AfricaSpainSwedenUKUSaustralian Securities exchange <strong>diversity</strong> guidelines require companies to disclose the number ofwomen on staff, in senior management <strong>and</strong> on the board.In mid March 2011, the austrian government agreed to the implementation of female quotas forsupervisory boards of state-owned companies. a quota of 25% is to be brought in by 2013 with anincrease to 35% by 2018. no sanctions for non-compliance have been set. <strong>The</strong> hope is that privatecompanies will follow the example set by the state-owned enterprises.Belgium’s parliament adopted a plan in June 2011 to force public enterprises, <strong>and</strong> companies thatare listed on the stock exchange, to give women 30% of the seats on management boards. Underthe new rules, each time a board member leaves he or she is to be replaced by a woman until thequota is fulfilled. Companies will have six years to reach the target, with small <strong>and</strong> medium-sizedenterprises (SMes) given eight years. Members of boards that do not reach the quota will lose thebenefits that come with their jobs.In the 2012 budget, the government proposed the creation of an advisory council of leaders fromthe private <strong>and</strong> public sectors to promote the participation of women on <strong>corporate</strong> boards.From 2008 the “comply or explain” code has required that <strong>diversity</strong> must be taken into account in allappointments.<strong>The</strong> european Commission is monitoring the progress of female board representation <strong>and</strong> has set atarget of 40% by 2020. no formal m<strong>and</strong>ates have been set.as of 1 January 2010, all listed companies have been required to have at least one man <strong>and</strong> onewoman on the board. <strong>The</strong>re are no penalties for non-compliance beyond the need to explain whythe target has not been met.Parliament passed a bill in mid January 2011 applying a 40% quota for female directors of listedcompanies by 2017. <strong>The</strong> quota also includes a target of 20% by 2014. <strong>The</strong> sanctions for noncomplianceare that nominations would be void <strong>and</strong> fees suspended for all board members.<strong>The</strong> German Corporate Governance Code was amended in May 2010 to include a statement recommendingboards of directors consider <strong>diversity</strong> when recruiting to fill board positions. <strong>The</strong> governmenthas discussed setting an aim of 30% representation by 2018.Passed a quota law in 2010 (40% from each sex by September 2013) applicable to publicly owned<strong>and</strong> publicly limited companies with more than 50 employees.<strong>The</strong> Ministry of Corporate affairs has proposed making at least one woman director m<strong>and</strong>atory in (asyet to be) prescribed types of companies. However, Parliament is yet to rule on any such legislation.a third of a company’s board must be women by 2015 or the business will face fines of up to eUR1 m, or USD 1.3 m, <strong>and</strong> the nullification of board election.all public <strong>and</strong> limited liability companies with over 250 employees are required to have at least 30%women on their boards or in senior management positions by 2016.Government guidelines suggest that a minimum 30% of the board members of all companies withmore than 250 employees should be women. If this goal is not reached by January 2016, companiesmust prepare a plan on how they intend to achieve it.In February 2002, the government gave a deadline of July 2005 for private listed companies to raisethe proportion of women on their boards to 40%. By July 2005, the proportion was only at 24%,<strong>and</strong> so in January 2006 legislation was introduced giving companies a final deadline of January2008, after which they would face fines or even closure. Full compliance was achieved by 2009.<strong>The</strong> <strong>corporate</strong> governance code recommends balanced gender representation on boards.Policies relating to Black economic empowerment (Bee) specifically targeted greater levels ofracial <strong>diversity</strong> at board level <strong>and</strong> have indirectly raised the profile of women on the board. a <strong>Gender</strong>equality Bill is being finalized. This may propose giving government the power to force companies toappoint women to half of all top positions.Passed a gender equality law in 2007 obliging public companies <strong>and</strong> IBex 35-quoted firms withmore than 250 employees to attain a minimum 40% share of each sex on their boards by 2015.Companies reaching this quota will be given priority status in the allocation of government contractsbut there are no formal sanctions.<strong>The</strong> “comply or explain” code requires companies to strive for gender parity on boards. Quotas havebeen discussed but not set.<strong>The</strong> government has asked FTSe 100 companies to aim for a minimum 25% female board representationby 2015 <strong>and</strong> further recommended that all FTSe 350 companies should explicitly set outtheir percentage targets for 2013 <strong>and</strong> 2015. <strong>The</strong> targets are not m<strong>and</strong>atory but are designed toencourage rather than coerce progress in female representation in top management.Under the Dodd-Frank act, Diversity Offices will implement rules to ensure the fair inclusion <strong>and</strong>utilization of minorities <strong>and</strong> women in all firms that do business with government agencies. <strong>The</strong> USSeC introduced a new code in December 2009, requiring the disclosure of how board nominationcommittees consider <strong>diversity</strong> in selecting c<strong>and</strong>idates for board positions.Women now account for 13.5% of aSx200directorships up from 8.4% at the end of 2010.7.5% of board members are women, accordingto the latest data from Catalyst.7.7% according to the latest Catalyst survey.Women make up just 14.5% of directors onCanada’s 500 largest company boards, accordingto a recent census by Catalyst.13.9% of board members are women,according to the latest data from Catalyst.14% of women across european boards oflisted companies are now women, up from12% in 2010.By april 2012, women accounted for 22% oflisted company board members, up from 12%in 2008.<strong>The</strong> rate of women on governing boards hasincreased from 8% in 2008 to 12% in 2010 toc. 14% now.Women make up 15.6% of the boards of largelisted companies.-5.3% according to 2011 data from Catalyst.Only 4.5% of Italy’s directors are women,according to GMI.as at november 2011, the percentage ofwomen in senior positions in 200 companieslisted on the Bursa Malaysia was 7.6%.18.5% of board members are women,according to Catalyst.achieved the 40% target of women on theboard by 2009.Just short of 11% of board seats are held bywomen.15.8% of board members are women,according to the latest data from Catalyst.Women made up 6.2% of boards in 2006 <strong>and</strong>11.2% by early 2011.latest data suggest 27% of board seats areoccupied by women, up from 22% in 2010 <strong>and</strong>6% in 2002.By the end of 2011, women accounted for16% of FTSe 100 positions, up from 12.2% in2009 <strong>and</strong> 7.2% in 2001.16.1% of board members are women,according to the latest data from Catalyst.No policies or proposals: Switzerl<strong>and</strong>, Japan, Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong, China, Brazil, Russia.

GenDeR DIveRSITY_26Barriers to changeas norway may have proved, forcing the pacethrough a quota system may yield the targetedresult. However, it is clear that there are plenty ofhurdles (some, but not all, of which are fairly structural)that are always likely to limit female representationon the board or indeed in other senior managementpositions.<strong>The</strong> double burden<strong>The</strong> so-called “double burden” refers to the dual roleundertaken by working women: one job in the formalworkplace <strong>and</strong> the other managing the household<strong>and</strong> family. Statistics calculated by eurostat suggestthat, on average, european women spend twice asmuch time doing domestic chores as men: fourhours <strong>and</strong> 29 minutes a day compared with twohours <strong>and</strong> 18 minutes for men. Over <strong>and</strong> above thispreponderance to perform household tasks, theother issue is children. Starting a family, on average,involves some kind of a break from the workplace<strong>and</strong> this is often not compatible with the dem<strong>and</strong>s ofa high profile leadership position. Maternity leave<strong>and</strong> reduced mobility are seen as impediments topromotion <strong>and</strong> fulfilling a management role: in theUSa, according to a Catalyst study, 62% of womensurveyed reported that family obligations were anobstacle to promotion. In France, 96% of femalegraduates from the “Gr<strong>and</strong>es ecoles” believed thathaving children, or being of child-bearing age, hinderedpromotion prospects.But it is not just the perception of femaleemployees that is the potential barrier to promotion;more women than men choose to opt out of a professionalcareer to have, or look after, a family. Thisautomatically reduces the talent pool that managerscan choose from <strong>and</strong> limits the number ofwomen available for board positions.<strong>The</strong> potential solution is to engineer a workingenvironment that is compatible with family life,which should be to the benefit of all employees,men <strong>and</strong> women. This is likely to require buy-infrom both the public <strong>and</strong> private sector. Public sectorremedies include tax breaks or credits to helpwith the cost of nursery fees <strong>and</strong> legislation onmaternity <strong>and</strong> paternity rights. Private sector remediescan come in many different forms: for example,flexible working hours, flexible working locations,provision of childcare services (e.g. an onsitecrèche) or job-sharing opportunities. From a managementperspective, the emphasis on careeradvancement should be focused on skills, capabilities<strong>and</strong> results, with less emphasis on time served.Social typecastingStereotyping is evident in all walks of life. It’s a usefulshortcut to lend context to any situation butcomes with a risk of perpetuating mistakes. aninteresting example is highlighted by MalcolmGladwell in his 2005 book entitled “Blink: Power ofThinking Without Thinking”. In the book, Gladwellfocused on the predicament of abbie Conant, whoauditioned for lead trombone with the Munich Philharmonicorchestra in 1980. Since another prospectivec<strong>and</strong>idate on the day was affiliated to theselection committee, the auditions were (unusuallyfor the time) conducted from behind a screen. allreports suggest Ms. Conant delivered an exceptional<strong>performance</strong> but the selection committeewere shocked (even horrified) to discover that shewas a woman. <strong>The</strong> committee overcame their biaslong enough to hire her but, sadly, not long enoughto afford her equal pay <strong>and</strong> equal rights (for thenext 13 years).<strong>The</strong> impact of blind auditions on <strong>diversity</strong> withinorchestras has been radical. a 1997 study conductedby Goldin <strong>and</strong> Rouse showed that prior tothe introduction of blind auditions less than 5% ofmusicians in the top five orchestras in the USawere women. Once blind auditions became st<strong>and</strong>ardpractice in the USa (over the 1970s <strong>and</strong>1980s), this number rose sharply to 25% <strong>and</strong> nowst<strong>and</strong>s at close to 50%.