PDF-file (The same edition. Another cover. 2.2 Mb)

PDF-file (The same edition. Another cover. 2.2 Mb)

PDF-file (The same edition. Another cover. 2.2 Mb)

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

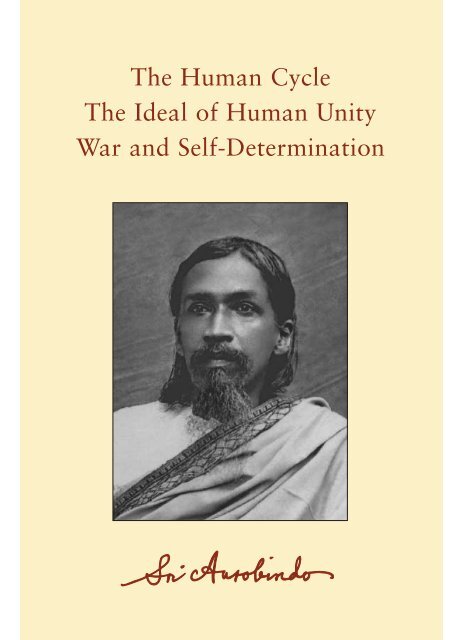

<strong>The</strong> Human Cycle<strong>The</strong> Ideal of Human UnityWar and Self-Determination

VOLUME 25THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO© Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust 1997Published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication DepartmentPrinted at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, PondicherryPRINTED IN INDIA

<strong>The</strong> Human Cycle<strong>The</strong> Ideal of Human UnityWar and Self-Determination

Publisher’s Note<strong>The</strong> Human Cycle was first published in monthly instalments inthe review Arya between August 1916 and July 1918 under thetitle <strong>The</strong> Psychology of Social Development. Each chapter waswritten immediately before its publication. <strong>The</strong> text was revisedduring the late 1930s and again, more lightly, in 1949. That yearit was published as a book under the title <strong>The</strong> Human Cycle.<strong>The</strong> Publisher’s Note to the first <strong>edition</strong>, which was dictated bySri Aurobindo, is reproduced in the present <strong>edition</strong>.<strong>The</strong> Ideal of Human Unity was written and published in monthlyinstalments in the Arya between September 1915 and July 1918.In 1919 it was brought out as a book. Sri Aurobindo wrotea Preface to that <strong>edition</strong> which is reproduced in the presentvolume. He revised the book during the late 1930s, before theoutbreak of World War II. References to political developmentsof the period between the world wars were introduced at thistime, often in footnotes. In 1949 Sri Aurobindo undertook afinal revision of <strong>The</strong> Ideal of Human Unity. He commentedon the changed international situation in footnotes and madealterations here and there throughout the book, but broughtit up to date mainly by the addition of a Postscript Chapter.In 1950 the revised text was published in an Indian and anAmerican <strong>edition</strong>.Five of the essays making up War and Self-Determination werepublished in the Arya between 1916 and 1920. In 1920 three ofthem — “<strong>The</strong> Passing of War?”, “<strong>The</strong> Unseen Power” and “Self-Determination” — along with a Foreword and a newly writtenessay, “<strong>The</strong> League of Nations”, were published as a book. Inlater <strong>edition</strong>s the other two Arya essays, “1919” and “After theWar”, were added by the editors.

CONTENTSTHE HUMAN CYCLEChapter I<strong>The</strong> Cycle of Society 5Chapter II<strong>The</strong> Age of Individualism and Reason 15Chapter III<strong>The</strong> Coming of the Subjective Age 26Chapter IV<strong>The</strong> Dis<strong>cover</strong>y of the Nation-Soul 35Chapter VTrue and False Subjectivism 44Chapter VI<strong>The</strong> Objective and Subjective Views of Life 55Chapter VII<strong>The</strong> Ideal Law of Social Development 63Chapter VIIICivilisation and Barbarism 73Chapter IXCivilisation and Culture 82Chapter XAesthetic and Ethical Culture 92Chapter XI<strong>The</strong> Reason as Governor of Life 102Chapter XII<strong>The</strong> Office and Limitations of the Reason 114

CONTENTSChapter XIIIReason and Religion 124Chapter XIV<strong>The</strong> Suprarational Beauty 136Chapter XV<strong>The</strong> Suprarational Good 146Chapter XVI<strong>The</strong> Suprarational Ultimate of Life 155Chapter XVIIReligion as the Law of Life 173Chapter XVIII<strong>The</strong> Infrarational Age of the Cycle 182Chapter XIX<strong>The</strong> Curve of the Rational Age 192Chapter XX<strong>The</strong> End of the Curve of Reason 208Chapter XXI<strong>The</strong> Spiritual Aim and Life 222Chapter XXII<strong>The</strong> Necessity of the Spiritual Transformation 232Chapter XXIIIConditions for the Coming of a Spiritual Age 246Chapter XXIV<strong>The</strong> Advent and Progress of the Spiritual Age 261

CONTENTSTHE IDEAL OF HUMAN UNITYPART IChapter I<strong>The</strong> Turn towards Unity: Its Necessity and Dangers 279Chapter II<strong>The</strong> Imperfection of Past Aggregates 285Chapter III<strong>The</strong> Group and the Individual 290Chapter IV<strong>The</strong> Inadequacy of the State Idea 296Chapter VNation and Empire: Real and Political Unities 304Chapter VIAncient and Modern Methods of Empire 312Chapter VII<strong>The</strong> Creation of the Heterogeneous Nation 323Chapter VIII<strong>The</strong> Problem of a Federated Heterogeneous Empire 330Chapter IX<strong>The</strong> Possibility of a World-Empire 337Chapter X<strong>The</strong> United States of Europe 344Chapter XI<strong>The</strong> Small Free Unit and the Larger ConcentratedUnity 355Chapter XII<strong>The</strong> Ancient Cycle of Prenational Empire-Building— <strong>The</strong> Modern Cycle of Nation-Building 364

CONTENTSChapter XXIV<strong>The</strong> Need of Military Unification 475Chapter XXVWar and the Need of Economic Unity 485Chapter XXVI<strong>The</strong> Need of Administrative Unity 494Chapter XXVII<strong>The</strong> Peril of the World-State 505Chapter XXVIIIDiversity in Oneness 513Chapter XXIX<strong>The</strong> Idea of a League of Nations 523Chapter XXX<strong>The</strong> Principle of Free Confederation 533Chapter XXXI<strong>The</strong> Conditions of a Free World-Union 540Chapter XXXIIInternationalism 548Chapter XXXIIIInternationalism and Human Unity 554Chapter XXXIV<strong>The</strong> Religion of Humanity 564Chapter XXXVSummary and Conclusion 571A Postscript Chapter 579

CONTENTSWAR AND SELF-DETERMINATION<strong>The</strong> Passing of War? 606<strong>The</strong> Unseen Power 612Self-Determination 623A League of Nations 6341919 664After the War 668APPENDIXESAppendix I 685Appendix II 686

Sri Aurobindo in Pondicherry

A page of the Arya with changes made in the 1930s

<strong>The</strong> Human Cycle

Publisher’s Note to the First Edition<strong>The</strong> chapters constituting this book were written under the title“<strong>The</strong> Psychology of Social Development” from month to monthin the philosophical monthly, “Arya”, from August 15, 1916to July 15, 1918 and used recent and contemporary events aswell as illustrations from the history of the past in explanationof the theory of social evolution put forward in these pages.<strong>The</strong> reader has therefore to go back in his mind to the eventsof that period in order to follow the line of thought and theatmosphere in which it developed. At one time there suggesteditself the necessity of bringing this part up to date, especiallyby some reference to later developments in Nazi Germany andthe development of a totalitarian Communist regime in Russia.But afterwards it was felt that there was sufficient previsionand allusion to these events and more elaborate description orcriticism of them was not essential; there was already withoutthem an adequate working out and elucidation of this theory ofthe social cycle.November, 1949

Chapter I<strong>The</strong> Cycle of SocietyMODERN Science, obsessed with the greatness of itsphysical dis<strong>cover</strong>ies and the idea of the sole existenceof Matter, has long attempted to base upon physicaldata even its study of Soul and Mind and of those workings ofNature in man and animal in which a knowledge of psychologyis as important as any of the physical sciences. Its very psychologyfounded itself upon physiology and the scrutiny of the brainand nervous system. It is not surprising therefore that in historyand sociology attention should have been concentrated on theexternal data, laws, institutions, rites, customs, economic factorsand developments, while the deeper psychological elementsso important in the activities of a mental, emotional, ideativebeing like man have been very much neglected. This kind ofscience would explain history and social development as muchas possible by economic necessity or motive, — by economy understoodin its widest sense. <strong>The</strong>re are even historians who denyor put aside as of a very subsidiary importance the workingof the idea and the influence of the thinker in the developmentof human institutions. <strong>The</strong> French Revolution, it is thought,would have happened just as it did and when it did, by economicnecessity, even if Rousseau and Voltaire had never written andthe eighteenth-century philosophic movement in the world ofthought had never worked out its bold and radical speculations.Recently, however, the all-sufficiency of Matter to explainMind and Soul has begun to be doubted and a movement ofemancipation from the obsession of physical science has set in,although as yet it has not gone beyond a few awkward andrudimentary stumblings. Still there is the beginning of a perceptionthat behind the economic motives and causes of social andhistorical development there are profound psychological, evenperhaps soul factors; and in pre-war Germany, the metropolis of

6 <strong>The</strong> Human Cyclerationalism and materialism but the home also, for a century anda half, of new thought and original tendencies good and bad,beneficent and disastrous, a first psychological theory of historywas conceived and presented by an original intelligence. <strong>The</strong>earliest attempts in a new field are seldom entirely successful,and the German historian, originator of this theory, seized ona luminous idea, but was not able to carry it very far or probevery deep. He was still haunted by a sense of the greater importanceof the economic factor, and like most European science histheory related, classified and organised phenomena much moresuccessfully than it explained them. Nevertheless, its basic ideaformulated a suggestive and illuminating truth, and it is worthwhile following up some of the suggestions it opens out in thelight especially of Eastern thought and experience.<strong>The</strong> theorist, Lamprecht, basing himself on European andparticularly on German history, supposed that human societyprogresses through certain distinct psychological stages whichhe terms respectively symbolic, typal and conventional, individualistand subjective. This development forms, then, a sort ofpsychological cycle through which a nation or a civilisation isbound to proceed. Obviously, such classifications are likely toerr by rigidity and to substitute a mental straight line for the coilsand zigzags of Nature. <strong>The</strong> psychology of man and his societiesis too complex, too synthetical of many-sided and intermixedtendencies to satisfy any such rigorous and formal analysis. Nordoes this theory of a psychological cycle tell us what is theinner meaning of its successive phases or the necessity of theirsuccession or the term and end towards which they are driving.But still to understand natural laws whether of Mind or Matterit is necessary to analyse their working into its dis<strong>cover</strong>ableelements, main constituents, dominant forces, though these maynot actually be found anywhere in isolation. I will leave asidethe Western thinker’s own dealings with his idea. <strong>The</strong> suggestivenames he has offered us, if we examine their intrinsic sense andvalue, may yet throw some light on the thickly veiled secret ofour historic evolution, and this is the line on which it would bemost useful to investigate.

8 <strong>The</strong> Human Cyclethe hymn of the Rig Veda which is supposed to be a marriagehymn for the union of a human couple and was certainly usedas such in the later Vedic ages. Yet the whole sense of the hymnturns about the successive marriages of Suryā, daughter of theSun, with different gods and the human marriage is quite asubordinate matter overshadowed and governed entirely by thedivine and mystic figure and is spoken of in the terms of thatfigure. Mark, however, that the divine marriage here is not, as itwould be in later ancient poetry, a decorative image or poeticalornamentation used to set off and embellish the human union;on the contrary, the human is an inferior figure and image of thedivine. <strong>The</strong> distinction marks off the entire contrast between thatmore ancient mentality and our modern regard upon things. Thissymbolism influenced for a long time Indian ideas of marriageand is even now conventionally remembered though no longerunderstood or effective.We may note also in passing that the Indian ideal of therelation between man and woman has always been governed bythe symbolism of the relation between the Purusha and Prakriti(in the Veda Nri and Gna), the male and female divine Principlesin the universe. Even, there is to some degree a practical correlationbetween the position of the female sex and this idea. In theearlier Vedic times when the female principle stood on a sort ofequality with the male in the symbolic cult, though with a certainpredominance for the latter, woman was as much the mate asthe adjunct of man; in later times when the Prakriti has becomesubject in idea to the Purusha, the woman also depends entirelyon the man, exists only for him and has hardly even a separatespiritual existence. In the Tantrik Shakta religion which puts thefemale principle highest, there is an attempt which could not getitself translated into social practice, — even as this Tantrik cultcould never entirely shake off the subjugation of the Vedanticidea, — to elevate woman and make her an object of profoundrespect and even of worship.Or let us take, for this example will serve us best, the Vedicinstitution of the fourfold order, caturvarṇa, miscalled the systemof the four castes, — for caste is a conventional, varṇa a

<strong>The</strong> Cycle of Society 9symbolic and typal institution. We are told that the institutionof the four orders of society was the result of an economicevolution complicated by political causes. Very possibly; 1 butthe important point is that it was not so regarded and couldnot be so regarded by the men of that age. For while we aresatisfied when we have found the practical and material causesof a social phenomenon and do not care to look farther, theycared little or only subordinately for its material factors andlooked always first and foremost for its symbolic, religious orpsychological significance. This appears in the Purushasukta ofthe Veda, where the four orders are described as having sprungfrom the body of the creative Deity, from his head, arms, thighsand feet. To us this is merely a poetical image and its sense isthat the Brahmins were the men of knowledge, the Kshatriyasthe men of power, the Vaishyas the producers and support ofsociety, the Shudras its servants. As if that were all, as if themen of those days would have so profound a reverence for merepoetical figures like this of the body of Brahma or that other ofthe marriages of Suryā, would have built upon them elaboratesystems of ritual and sacred ceremony, enduring institutions,great demarcations of social type and ethical discipline. We readalways our own mentality into that of these ancient forefathersand it is therefore that we can find in them nothing but imaginativebarbarians. To us poetry is a revel of intellect and fancy,imagination a plaything and caterer for our amusement, ourentertainer, the nautch-girl of the mind. But to the men of oldthe poet was a seer, a revealer of hidden truths, imagination nodancing courtesan but a priestess in God’s house commissionednot to spin fictions but to image difficult and hidden truths;even the metaphor or simile in the Vedic style is used with aserious purpose and expected to convey a reality, not to suggesta pleasing artifice of thought. <strong>The</strong> image was to these seers arevelative symbol of the unrevealed and it was used because itcould hint luminously to the mind what the precise intellectual1 It is at least doubtful. <strong>The</strong> Brahmin class at first seem to have exercised all sorts ofeconomic functions and not to have confined themselves to those of the priesthood.

10 <strong>The</strong> Human Cycleword, apt only for logical or practical thought or to express thephysical and the superficial, could not at all hope to manifest. Tothem this symbol of the Creator’s body was more than an image,it expressed a divine reality. Human society was for them anattempt to express in life the cosmic Purusha who has expressedhimself otherwise in the material and the supraphysical universe.Man and the cosmos are both of them symbols and expressionsof the <strong>same</strong> hidden Reality.From this symbolic attitude came the tendency to makeeverything in society a sacrament, religious and sacrosanct, butas yet with a large and vigorous freedom in all its forms, — afreedom which we do not find in the rigidity of “savage” communitiesbecause these have already passed out of the symbolic intothe conventional stage though on a curve of degeneration insteadof a curve of growth. <strong>The</strong> spiritual idea governs all; the symbolicreligious forms which support it are fixed in principle; the socialforms are lax, free and capable of infinite development. Onething, however, begins to progress towards a firm fixity and thisis the psychological type. Thus we have first the symbolic idea ofthe four orders, expressing — to employ an abstractly figurativelanguage which the Vedic thinkers would not have used nor perhapsunderstood, but which helps best our modern understanding— the Divine as knowledge in man, the Divine as power,the Divine as production, enjoyment and mutuality, the Divineas service, obedience and work. <strong>The</strong>se divisions answer to fourcosmic principles, the Wisdom that conceives the order and principleof things, the Power that sanctions, upholds and enforces it,the Harmony that creates the arrangement of its parts, the Workthat carries out what the rest direct. Next, out of this idea theredeveloped a firm but not yet rigid social order based primarilyupon temperament and psychic type 2 with a correspondingethical discipline and secondarily upon the social and economicfunction. 3 But the function was determined by its suitabilityto the type and its helpfulness to the discipline; it was not the2 guṇa.3 karma.

<strong>The</strong> Cycle of Society 11primary or sole factor. <strong>The</strong> first, the symbolic stage of this evolutionis predominantly religious and spiritual; the other elements,psychological, ethical, economic, physical are there but subordinatedto the spiritual and religious idea. <strong>The</strong> second stage,which we may call the typal, is predominantly psychological andethical; all else, even the spiritual and religious, is subordinate tothe psychological idea and to the ethical ideal which expresses it.Religion becomes then a mystic sanction for the ethical motiveand discipline, Dharma; that becomes its chief social utility, andfor the rest it takes a more and more other-worldly turn. <strong>The</strong> ideaof the direct expression of the divine Being or cosmic Principle inman ceases to dominate or to be the leader and in the forefront;it recedes, stands in the background and finally disappears fromthe practice and in the end even from the theory of life.This typal stage creates the great social ideals which remainimpressed upon the human mind even when the stage itself ispassed. <strong>The</strong> principal active contribution it leaves behind when itis dead is the idea of social honour; the honour of the Brahminwhich resides in purity, in piety, in a high reverence for thethings of the mind and spirit and a disinterested possession andexclusive pursuit of learning and knowledge; the honour of theKshatriya which lives in courage, chivalry, strength, a certainproud self-restraint and self-mastery, nobility of character andthe obligations of that nobility; the honour of the Vaishya whichmaintains itself by rectitude of dealing, mercantile fidelity, soundproduction, order, liberality and philanthropy; the honour of theShudra which gives itself in obedience, subordination, faithfulservice, a disinterested attachment. But these more and morecease to have a living root in the clear psychological idea or tospring naturally out of the inner life of the man; they become aconvention, though the most noble of conventions. In the endthey remain more as a tradition in the thought and on the lipsthan a reality of the life.For the typal passes naturally into the conventional stage.<strong>The</strong> conventional stage of human society is born when the externalsupports, the outward expressions of the spirit or the idealbecome more important than the ideal, the body or even the

12 <strong>The</strong> Human Cycleclothes more important than the person. Thus in the evolutionof caste, the outward supports of the ethical fourfold order, —birth, economic function, religious ritual and sacrament, familycustom, — each began to exaggerate enormously its proportionsand its importance in the scheme. At first, birth does not seem tohave been of the first importance in the social order, for facultyand capacity prevailed; but afterwards, as the type fixed itself, itsmaintenance by education and tradition became necessary andeducation and tradition naturally fixed themselves in a hereditarygroove. Thus the son of a Brahmin came always to belooked upon conventionally as a Brahmin; birth and professionwere together the double bond of the hereditary convention atthe time when it was most firm and faithful to its own character.This rigidity once established, the maintenance of the ethicaltype passed from the first place to a secondary or even a quitetertiary importance. Once the very basis of the system, it camenow to be a not indispensable crown or pendent tassel, insistedupon indeed by the thinker and the ideal code-maker but notby the actual rule of society or its practice. Once ceasing to beindispensable, it came inevitably to be dispensed with except asan ornamental fiction. Finally, even the economic basis began todisintegrate; birth, family custom and remnants, deformations,new accretions of meaningless or fanciful religious sign andritual, the very scarecrow and caricature of the old profoundsymbolism, became the riveting links of the system of caste inthe iron age of the old society. In the full economic period ofcaste the priest and the Pundit masquerade under the name ofthe Brahmin, the aristocrat and feudal baron under the name ofthe Kshatriya, the trader and money-getter under the name ofthe Vaishya, the half-fed labourer and economic serf under thename of the Shudra. When the economic basis also breaks down,then the unclean and diseased decrepitude of the old system hasbegun; it has become a name, a shell, a sham and must either bedissolved in the crucible of an individualist period of society orelse fatally affect with weakness and falsehood the system of lifethat clings to it. That in visible fact is the last and present stateof the caste system in India.

<strong>The</strong> Cycle of Society 13<strong>The</strong> tendency of the conventional age of society is to fix, toarrange firmly, to formalise, to erect a system of rigid grades andhierarchies, to stereotype religion, to bind education and trainingto a traditional and unchangeable form, to subject thought toinfallible authorities, to cast a stamp of finality on what seems toit the finished life of man. <strong>The</strong> conventional period of society hasits golden age when the spirit and thought that inspired its formsare confined but yet living, not yet altogether walled in, not yetstifled to death and petrified by the growing hardness of thestructure in which they are cased. That golden age is often verybeautiful and attractive to the distant view of posterity by itsprecise order, symmetry, fine social architecture, the admirablesubordination of its parts to a general and noble plan. Thus atone time the modern litterateur, artist or thinker looked backoften with admiration and with something like longing to themediaeval age of Europe; he forgot in its distant appearance ofpoetry, nobility, spirituality the much folly, ignorance, iniquity,cruelty and oppression of those harsh ages, the suffering andrevolt that simmered below these fine surfaces, the misery andsqualor that was hidden behind that splendid façade. So toothe Hindu orthodox idealist looks back to a perfectly regulatedsociety devoutly obedient to the wise yoke of the Shastra, andthat is his golden age, — a nobler one than the European inwhich the apparent gold was mostly hard burnished copperwith a thin gold-leaf <strong>cover</strong>ing it, but still of an alloyed metal,not the true Satya Yuga. In these conventional periods of societythere is much indeed that is really fine and sound and helpfulto human progress, but still they are its copper age and not thetrue golden; they are the age when the Truth we strive to arriveat is not realised, not accomplished, 4 but the exiguity of it ekedout or its full appearance imitated by an artistic form, and whatwe have of the reality has begun to fossilise and is doomed to belost in a hard mass of rule and order and convention.For always the form prevails and the spirit recedes and4 <strong>The</strong> Indian names of the golden age are Satya, the Age of the Truth, and Krita, theAge when the law of the Truth is accomplished.

14 <strong>The</strong> Human Cyclediminishes. It attempts indeed to return, to revive the form,to modify it, anyhow to survive and even to make the formsurvive; but the time-tendency is too strong. This is visible in thehistory of religion; the efforts of the saints and religious reformersbecome progressively more scattered, brief and superficialin their actual effects, however strong and vital the impulse. Wesee this recession in the growing darkness and weakness of Indiain her last millennium; the constant effort of the most powerfulspiritual personalities kept the soul of the people alive but failedto resuscitate the ancient free force and truth and vigour orpermanently revivify a conventionalised and stagnating society;in a generation or two the iron grip of that conventionalism hasalways fallen on the new movement and annexed the names ofits founders. We see it in Europe in the repeated moral tragedyof ecclesiasticism and Catholic monasticism. <strong>The</strong>n there arrivesa period when the gulf between the convention and the truthbecomes intolerable and the men of intellectual power arise,the great “swallowers of formulas”, who, rejecting robustly orfiercely or with the calm light of reason symbol and type andconvention, strike at the walls of the prison-house and seekby the individual reason, moral sense or emotional desire theTruth that society has lost or buried in its whited sepulchres. Itis then that the individualistic age of religion and thought andsociety is created; the Age of Protestantism has begun, the Ageof Reason, the Age of Revolt, Progress, Freedom. A partial andexternal freedom, still betrayed by the conventional age thatpreceded it into the idea that the Truth can be found in outsides,dreaming vainly that perfection can be determined by machinery,but still a necessary passage to the subjective period of humanitythrough which man has to circle back towards the re<strong>cover</strong>y ofhis deeper self and a new upward line or a new revolving cycleof civilisation.

Chapter II<strong>The</strong> Age of Individualismand ReasonAN INDIVIDUALISTIC age of human society comes as aresult of the corruption and failure of the conventional,as a revolt against the reign of the petrified typal figure.Before it can be born it is necessary that the old truths shallhave been lost in the soul and practice of the race and that eventhe conventions which ape and replace them shall have becomedevoid of real sense and intelligence; stripped of all practicaljustification, they exist only mechanically by fixed idea, by theforce of custom, by attachment to the form. It is then that menin spite of the natural conservatism of the social mind are compelledat last to perceive that the Truth is dead in them and thatthey are living by a lie. <strong>The</strong> individualism of the new age is anattempt to get back from conventionalism of belief and practiceto some solid bed-rock, no matter what, of real and tangibleTruth. And it is necessarily individualistic, because all the oldgeneral standards have become bankrupt and can no longer giveany inner help; it is therefore the individual who has to become adis<strong>cover</strong>er, a pioneer, and to search out by his individual reason,intuition, idealism, desire, claim upon life or whatever otherlight he finds in himself the true law of the world and of his ownbeing. By that, when he has found or thinks he has found it,he will strive to rebase on a firm foundation and remould in amore vital even if a poorer form religion, society, ethics, politicalinstitutions, his relations with his fellows, his strivings for hisown perfection and his labour for mankind.It is in Europe that the age of individualism has taken birthand exercised its full sway; the East has entered into it only bycontact and influence, not from an original impulse. And it is toits passion for the dis<strong>cover</strong>y of the actual truth of things and for

16 <strong>The</strong> Human Cyclethe governing of human life by whatever law of the truth it hasfound that the West owes its centuries of strength, vigour, light,progress, irresistible expansion. Equally, it is due not to anyoriginal falsehood in the ideals on which its life was founded,but to the loss of the living sense of the Truth it once held and itslong contented slumber in the cramping bonds of a mechanicalconventionalism that the East has found itself helpless in thehour of its awakening, a giant empty of strength, inert massesof men who had forgotten how to deal freely with facts andforces because they had learned only how to live in a world ofstereotyped thought and customary action. Yet the truths whichEurope has found by its individualistic age <strong>cover</strong>ed only the firstmore obvious, physical and outward facts of life and only such oftheir more hidden realities and powers as the habit of analyticalreason and the pursuit of practical utility can give to man. Ifits rationalistic civilisation has swept so triumphantly over theworld, it is because it found no deeper and more powerful truthto confront it; for all the rest of mankind was still in the inactivityof the last dark hours of the conventional age.<strong>The</strong> individualistic age of Europe was in its beginning arevolt of reason, in its culmination a triumphal progress ofphysical Science. Such an evolution was historically inevitable.<strong>The</strong> dawn of individualism is always a questioning, a denial.<strong>The</strong> individual finds a religion imposed upon him which doesnot base its dogma and practice upon a living sense of eververifiable spiritual Truth, but on the letter of an ancient book,the infallible dictum of a Pope, the tradition of a Church, thelearned casuistry of schoolmen and Pundits, conclaves of ecclesiastics,heads of monastic orders, doctors of all sorts, all ofthem unquestionable tribunals whose sole function is to judgeand pronounce, but none of whom seems to think it necessaryor even allowable to search, test, prove, inquire, dis<strong>cover</strong>. Hefinds that, as is inevitable under such a regime, true science andknowledge are either banned, punished and persecuted or elserendered obsolete by the habit of blind reliance on fixed authorities;even what is true in old authorities is no longer of any value,because its words are learnedly or ignorantly repeated but its real

<strong>The</strong> Age of Individualism and Reason 17sense is no longer lived except at most by a few. In politics hefinds everywhere divine rights, established privileges, sanctifiedtyrannies which are evidently armed with an oppressive powerand justify themselves by long prescription, but seem to haveno real claim or title to exist. In the social order he finds anequally stereotyped reign of convention, fixed disabilities, fixedprivileges, the self-regarding arrogance of the high, the blindprostration of the low, while the old functions which mighthave justified at one time such a distribution of status are eithernot performed at all or badly performed without any sense ofobligation and merely as a part of caste pride. He has to rise inrevolt; on every claim of authority he has to turn the eye of aresolute inquisition; when he is told that this is the sacred truthof things or the command of God or the immemorial order ofhuman life, he has to reply, “But is it really so? How shall I knowthat this is the truth of things and not superstition and falsehood?When did God command it, or how do I know that this was thesense of His command and not your error or invention, or thatthe book on which you found yourself is His word at all, orthat He has ever spoken His will to mankind? This immemorialorder of which you speak, is it really immemorial, really a lawof Nature or an imperfect result of Time and at present a mostfalse convention? And of all you say, still I must ask, does itagree with the facts of the world, with my sense of right, withmy judgment of truth, with my experience of reality?” And if itdoes not, the revolting individual flings off the yoke, declares thetruth as he sees it and in doing so strikes inevitably at the rootof the religious, the social, the political, momentarily perhapseven the moral order of the community as it stands, because itstands upon the authority he discredits and the convention hedestroys and not upon a living truth which can be successfullyopposed to his own. <strong>The</strong> champions of the old order may beright when they seek to suppress him as a destructive agencyperilous to social security, political order or religious tradition;but he stands there and can no other, because to destroy is hismission, to destroy falsehood and lay bare a new foundation oftruth.

18 <strong>The</strong> Human CycleBut by what individual faculty or standard shall the innovatorfind out his new foundation or establish his new measures?Evidently, it will depend upon the available enlightenment of thetime and the possible forms of knowledge to which he has access.At first it was in religion a personal illumination supported inthe West by a theological, in the East by a philosophical reasoning.In society and politics it started with a crude primitiveperception of natural right and justice which took its originfrom the exasperation of suffering or from an awakened senseof general oppression, wrong, injustice and the indefensibilityof the existing order when brought to any other test than thatof privilege and established convention. <strong>The</strong> religious motiveled at first; the social and political, moderating itself after theswift suppression of its first crude and vehement movements,took advantage of the upheaval of religious reformation, followedbehind it as a useful ally and waited its time to assumethe lead when the spiritual momentum had been spent and,perhaps by the very force of the secular influences it called toits aid, had missed its way. <strong>The</strong> movement of religious freedomin Europe took its stand first on a limited, then on anabsolute right of the individual experience and illumined reasonto determine the true sense of inspired Scripture and the trueChristian ritual and order of the Church. <strong>The</strong> vehemence ofits claim was measured by the vehemence of its revolt fromthe usurpations, pretensions and brutalities of the ecclesiasticalpower which claimed to withhold the Scripture from generalknowledge and impose by moral authority and physical violenceits own arbitrary interpretation of Sacred Writ, if not indeedanother and substituted doctrine, on the recalcitrant individualconscience. In its more tepid and moderate forms the revoltengendered such compromises as the Episcopalian Churches, ata higher degree of fervour Calvinistic Puritanism, at white heata riot of individual religious judgment and imagination in suchsects as the Anabaptist, Independent, Socinian and countlessothers. In the East such a movement divorced from all politicalor any strongly iconoclastic social significance would have producedsimply a series of religious reformers, illumined saints,

<strong>The</strong> Age of Individualism and Reason 19new bodies of belief with their appropriate cultural and socialpractice; in the West atheism and secularism were its inevitableand predestined goal. At first questioning the conventional formsof religion, the mediation of the priesthood between God andthe soul and the substitution of Papal authority for the authorityof the Scripture, it could not fail to go forward and question theScripture itself and then all supernaturalism, religious belief orsuprarational truth no less than outward creed and institute.For, eventually, the evolution of Europe was determined lessby the Reformation than by the Renascence; it flowered by thevigorous return of the ancient Graeco-Roman mentality of theone rather than by the Hebraic and religio-ethical temperamentof the other. <strong>The</strong> Renascence gave back to Europe on one handthe free curiosity of the Greek mind, its eager search for firstprinciples and rational laws, its delighted intellectual scrutiny ofthe facts of life by the force of direct observation and individualreasoning, on the other the Roman’s large practicality and hissense for the ordering of life in harmony with a robust utility andthe just principles of things. But both these tendencies were pursuedwith a passion, a seriousness, a moral and almost religiousardour which, lacking in the ancient Graeco-Roman mentality,Europe owed to her long centuries of Judaeo-Christian discipline.It was from these sources that the individualistic age ofWestern society sought ultimately for that principle of order andcontrol which all human society needs and which more ancienttimes attempted to realise first by the materialisation of fixedsymbols of truth, then by ethical type and discipline, finally byinfallible authority or stereotyped convention.Manifestly, the unrestrained use of individual illuminationor judgment without either any outer standard or any generallyrecognisable source of truth is a perilous experiment for ourimperfect race. It is likely to lead rather to a continual fluctuationand disorder of opinion than to a progressive unfolding of thetruth of things. No less, the pursuit of social justice throughthe stark assertion of individual rights or class interests anddesires must be a source of continual struggle and revolutionand may end in an exaggerated assertion of the will in each to

20 <strong>The</strong> Human Cyclelive his own life and to satisfy his own ideas and desires whichwill produce a serious malaise or a radical trouble in the socialbody. <strong>The</strong>refore on every individualistic age of mankind there isimperative the search for two supreme desiderata. It must finda general standard of Truth to which the individual judgmentof all will be inwardly compelled to subscribe without physicalconstraint or imposition of irrational authority. And it mustreach too some principle of social order which shall be equallyfounded on a universally recognisable truth of things; an order isneeded that will put a rein on desire and interest by providing atleast some intellectual and moral test which these two powerfuland dangerous forces must satisfy before they can feel justifiedin asserting their claims on life. Speculative and scientific reasonfor their means, the pursuit of a practicable social justice andsound utility for their spirit, the progressive nations of Europeset out on their search for this light and this law.<strong>The</strong>y found and held it with enthusiasm in the dis<strong>cover</strong>ies ofphysical Science. <strong>The</strong> triumphant domination, the all-shatteringand irresistible victory of Science in nineteenth-century Europeis explained by the absolute perfection with which it at leastseemed for a time to satisfy these great psychological wants ofthe Western mind. Science seemed to it to fulfil impeccably itssearch for the two supreme desiderata of an individualistic age.Here at last was a truth of things which depended on no doubtfulScripture or fallible human authority but which Mother Natureherself had written in her eternal book for all to read who hadpatience to observe and intellectual honesty to judge. Here werelaws, principles, fundamental facts of the world and of our beingwhich all could verify at once for themselves and which musttherefore satisfy and guide the free individual judgment, deliveringit equally from alien compulsion and from erratic self-will.Here were laws and truths which justified and yet controlledthe claims and desires of the individual human being; here ascience which provided a standard, a norm of knowledge, arational basis for life, a clear outline and sovereign means forthe progress and perfection of the individual and the race. <strong>The</strong>attempt to govern and organise human life by verifiable Science,

<strong>The</strong> Age of Individualism and Reason 21by a law, a truth of things, an order and principles which allcan observe and verify in their ground and fact and to whichtherefore all may freely and must rationally subscribe, is theculminating movement of European civilisation. It has been thefulfilment and triumph of the individualistic age of human society;it has seemed likely also to be its end, the cause of thedeath of individualism and its putting away and burial amongthe monuments of the past.For this dis<strong>cover</strong>y by individual free-thought of universallaws of which the individual is almost a by-product and bywhich he must necessarily be governed, this attempt actuallyto govern the social life of humanity in conscious accordancewith the mechanism of these laws seems to lead logically tothe suppression of that very individual freedom which madethe dis<strong>cover</strong>y and the attempt at all possible. In seeking thetruth and law of his own being the individual seems to havedis<strong>cover</strong>ed a truth and law which is not of his own individualbeing at all, but of the collectivity, the pack, the hive, the mass.<strong>The</strong> result to which this points and to which it still seems irresistiblyto be driving us is a new ordering of society by a rigideconomic or governmental Socialism in which the individual,deprived again of his freedom in his own interest and that ofhumanity, must have his whole life and action determined forhim at every step and in every point from birth to old age bythe well-ordered mechanism of the State. 1 We might then have acurious new version, with very important differences, of the oldAsiatic or even of the old Indian order of society. In place of thereligio-ethical sanction there will be a scientific and rational ornaturalistic motive and rule; instead of the Brahmin Shastrakarathe scientific, administrative and economic expert. In the placeof the King himself observing the law and compelling with theaid and consent of the society all to tread without deviation1 We already see a violent though incomplete beginning of this line of social evolutionin Fascist Italy, Nazi Germany, Communist Russia. <strong>The</strong> trend is for more and morenations to accept this beginning of a new order, and the resistance of the old orderis more passive than active — it lacks the fire, enthusiasm and self-confidence whichanimates the innovating Idea.

22 <strong>The</strong> Human Cyclethe line marked out for them, the line of the Dharma, therewill stand the collectivist State similarly guided and empowered.Instead of a hierarchical arrangement of classes each with itspowers, privileges and duties there will be established an initialequality of education and opportunity, ultimately perhaps witha subsequent determination of function by experts who shallknow us better than ourselves and choose for us our work andquality. Marriage, generation and the education of the childmay be fixed by the scientific State as of old by the Shastra.For each man there will be a long stage of work for the Statesuperintended by collectivist authorities and perhaps in the enda period of liberation, not for action but for enjoyment of leisureand personal self-improvement, answering to the Vanaprasthaand Sannyasa Asramas of the old Aryan society. <strong>The</strong> rigidityof such a social state would greatly surpass that of its Asiaticforerunner; for there at least there were for the rebel, the innovatortwo important concessions. <strong>The</strong>re was for the individualthe freedom of an early Sannyasa, a renunciation of the socialfor the free spiritual life, and there was for the group the libertyto form a sub-society governed by new conceptions like theSikh or the Vaishnava. But neither of these violent departuresfrom the norm could be tolerated by a strictly economic andrigorously scientific and unitarian society. Obviously, too, therewould grow up a fixed system of social morality and custom anda body of socialistic doctrine which one could not be allowedto question practically, and perhaps not even intellectually, sincethat would soon shatter or else undermine the system. Thuswe should have a new typal order based upon purely economiccapacity and function, guṇakarma, and rapidly petrifying bythe inhibition of individual liberty into a system of rationalisticconventions. And quite certainly this static order would at longlast be broken by a new individualist age of revolt, led probablyby the principles of an extreme philosophical Anarchism.On the other hand, there are in operation forces which seemlikely to frustrate or modify this development before it can reachits menaced consummation. In the first place, rationalistic andphysical Science has overpassed itself and must before long be

<strong>The</strong> Age of Individualism and Reason 23overtaken by a mounting flood of psychological and psychicknowledge which cannot fail to compel quite a new view ofthe human being and open a new vista before mankind. Atthe <strong>same</strong> time the Age of Reason is visibly drawing to an end;novel ideas are sweeping over the world and are being acceptedwith a significant rapidity, ideas inevitably subversive of anypremature typal order of economic rationalism, dynamic ideassuch as Nietzsche’s Will-to-live, Bergson’s exaltation of Intuitionabove intellect or the latest German philosophical tendency toacknowledge a suprarational faculty and a suprarational orderof truths. Already another mental poise is beginning to settleand conceptions are on the way to apply themselves in the fieldof practice which promise to give the succession of the individualisticage of society not to a new typal order, but to a subjectiveage which may well be a great and momentous passage to a verydifferent goal. It may be doubted whether we are not already inthe morning twilight of a new period of the human cycle.Secondly, the West in its triumphant conquest of the worldhas awakened the slumbering East and has produced in its midstan increasing struggle between an imported Western individualismand the old conventional principle of society. <strong>The</strong> latter ishere rapidly, there slowly breaking down, but something quitedifferent from Western individualism may very well take itsplace. Some opine, indeed, that Asia will reproduce Europe’sAge of Reason with all its materialism and secularist individualismwhile Europe itself is pushing onward into new formsand ideas; but this is in the last degree improbable. On thecontrary, the signs are that the individualistic period in the Eastwill be neither of long duration nor predominantly rationalisticand secularist in its character. If then the East, as the result ofits awakening, follows its own bent and evolves a novel socialtendency and culture, that is bound to have an enormous effecton the direction of the world’s civilisation; we can measure itsprobable influence by the profound results of the first reflux ofthe ideas even of the unawakened East upon Europe. Whateverthat effect may be, it will not be in favour of any re-orderingof society on the lines of the still current tendency towards a

24 <strong>The</strong> Human Cyclemechanical economism which has not ceased to dominate mindand life in the Occident. <strong>The</strong> influence of the East is likely to berather in the direction of subjectivism and practical spirituality,a greater opening of our physical existence to the realisation ofideals other than the strong but limited aims suggested by thelife and the body in their own gross nature.But, most important of all, the individualistic age of Europehas in its dis<strong>cover</strong>y of the individual fixed among the idea-forcesof the future two of a master potency which cannot be entirelyeliminated by any temporary reaction. <strong>The</strong> first of these, nowuniversally accepted, is the democratic conception of the rightof all individuals as members of the society to the full life andthe full development of which they are individually capable.It is no longer possible that we should accept as an ideal anyarrangement by which certain classes of society should arrogatedevelopment and full social fruition to themselves while assigninga bare and barren function of service alone to others. Itis now fixed that social development and well-being mean thedevelopment and well-being of all the individuals in the societyand not merely a flourishing of the community in the mass whichresolves itself really into the splendour and power of one ortwo classes. This conception has been accepted in full by allprogressive nations and is the basis of the present socialistictendency of the world. But in addition there is this deeper truthwhich individualism has dis<strong>cover</strong>ed, that the individual is notmerely a social unit; his existence, his right and claim to live andgrow are not founded solely on his social work and function.He is not merely a member of a human pack, hive or ant-hill;he is something in himself, a soul, a being, who has to fulfilhis own individual truth and law as well as his natural or hisassigned part in the truth and law of the collective existence. 2 Hedemands freedom, space, initiative for his soul, for his nature,for that puissant and tremendous thing which society so much2 This is no longer recognised by the new order, Fascist or Communistic, — here theindividual is reduced to a cell or atom of the social body. “We have destroyed” proclaimsa German exponent “the false view that men are individual beings; there is no liberty ofindividuals, there is only liberty of nations or races.”

<strong>The</strong> Age of Individualism and Reason 25distrusts and has laboured in the past either to suppress altogetheror to relegate to the purely spiritual field, an individualthought, will and conscience. If he is to merge these eventually,it cannot be into the dominating thought, will and conscience ofothers, but into something beyond into which he and all mustbe both allowed and helped freely to grow. That is an idea, atruth which, intellectually recognised and given its full exteriorand superficial significance by Europe, agrees at its root with theprofoundest and highest spiritual conceptions of Asia and has alarge part to play in the moulding of the future.

Chapter III<strong>The</strong> Coming of the Subjective AgeTHE INHERENT aim and effort and justification, thepsychological seed-cause, the whole tendency of developmentof an individualistic age of mankind, all go backto the one dominant need of redis<strong>cover</strong>ing the substantial truthsof life, thought and action which have been overlaid by thefalsehood of conventional standards no longer alive to the truthof the ideas from which their conventions started. It would seemat first that the shortest way would be to return to the originalideas themselves for light, to rescue the kernel of their truth fromthe shell of convention in which it has become incrusted. But tothis course there is a great practical obstacle; and there is anotherwhich reaches beyond the surface of things, nearer to the deeperprinciples of the development of the soul in human society. <strong>The</strong>re<strong>cover</strong>y of the old original ideas now travestied by conventionis open to the practical disadvantage that it tends after a time torestore force to the conventions which the Time-Spirit is seekingto outgrow and, if or when the deeper truth-seeking tendencyslackens in its impulse, the conventions re-establish their sway.<strong>The</strong>y revive, modified, no doubt, but still powerful; a new incrustationsets in, the truth of things is overlaid by a more complexfalsity. And even if it were otherwise, the need of a developinghumanity is not to return always to its old ideas. Its need is toprogress to a larger fulfilment in which, if the old is taken up,it must be transformed and exceeded. For the underlying truthof things is constant and eternal, but its mental figures, its lifeforms, its physical embodiments call constantly for growth andchange.It is this principle and necessity that justify an age of individualismand rationalism and make it, however short it may be, aninevitable period in the cycle. A temporary reign of the criticalreason largely destructive in its action is an imperative need for

<strong>The</strong> Coming of the Subjective Age 27human progress. In India, since the great Buddhistic upheavalof the national thought and life, there has been a series of recurrentattempts to redis<strong>cover</strong> the truth of the soul and life andget behind the veil of stifling conventions; but these have beenconducted by a wide and tolerant spiritual reason, a plastic soulintuitionand deep subjective seeking, insufficiently militant anddestructive. Although productive of great internal and considerableexternal changes, they have never succeeded in getting ridof the predominant conventional order. <strong>The</strong> work of a dissolventand destructive intellectual criticism, though not entirely absentfrom some of these movements, has never gone far enough; theconstructive force, insufficiently aided by the destructive, has notbeen able to make a wide and free space for its new formation.It is only with the period of European influence and impact thatcircumstances and tendencies powerful enough to enforce thebeginnings of a new age of radical and effective revaluation ofideas and things have come into existence. <strong>The</strong> characteristicpower of these influences has been throughout — or at any ratetill quite recently — rationalistic, utilitarian and individualistic.It has compelled the national mind to view everything froma new, searching and critical standpoint, and even those whoseek to preserve the present or restore the past are obliged unconsciouslyor half-consciously to justify their endeavour fromthe novel point of view and by its appropriate standards ofreasoning. Throughout the East, the subjective Asiatic mind isbeing driven to adapt itself to the need for changed values oflife and thought. It has been forced to turn upon itself both bythe pressure of Western knowledge and by the compulsion of aquite changed life-need and life-environment. What it did notdo from within, has come on it as a necessity from without andthis externality has carried with it an immense advantage as wellas great dangers.<strong>The</strong> individualistic age is, then, a radical attempt of mankindto dis<strong>cover</strong> the truth and law both of the individual being andof the world to which the individual belongs. It may begin, as itbegan in Europe, with the endeavour to get back, more especiallyin the sphere of religion, to the original truth which convention

28 <strong>The</strong> Human Cyclehas overlaid, defaced or distorted; but from that first step itmust proceed to others and in the end to a general questioningof the foundations of thought and practice in all the spheres ofhuman life and action. A revolutionary reconstruction of religion,philosophy, science, art and society is the last inevitableoutcome. It proceeds at first by the light of the individual mindand reason, by its demand on life and its experience of life; butit must go from the individual to the universal. For the effort ofthe individual soon shows him that he cannot securely dis<strong>cover</strong>the truth and law of his own being without dis<strong>cover</strong>ing someuniversal law and truth to which he can relate it. Of the universehe is a part; in all but his deepest spirit he is its subject, a smallcell in that tremendous organic mass: his substance is drawnfrom its substance and by the law of its life the law of his lifeis determined and governed. From a new view and knowledgeof the world must proceed his new view and knowledge of himself,of his power and capacity and limitations, of his claim onexistence and the high road and the distant or immediate goalof his individual and social destiny.In Europe and in modern times this has taken the formof a clear and potent physical Science: it has proceeded by thedis<strong>cover</strong>y of the laws of the physical universe and the economicand sociological conditions of human life as determined by thephysical being of man, his environment, his evolutionary history,his physical and vital, his individual and collective need. Butafter a time it must become apparent that the knowledge of thephysical world is not the whole of knowledge; it must appearthat man is a mental as well as a physical and vital being and evenmuch more essentially mental than physical or vital. Even thoughhis psychology is strongly affected and limited by his physicalbeing and environment, it is not at its roots determined by them,but constantly reacts, subtly determines their action, effects eventheir new-shaping by the force of his psychological demand onlife. His economic state and social institutions are themselvesgoverned by his psychological demand on the possibilities, circumstances,tendencies created by the relation between the mindand soul of humanity and its life and body. <strong>The</strong>refore to find the

<strong>The</strong> Coming of the Subjective Age 29truth of things and the law of his being in relation to that truthhe must go deeper and fathom the subjective secret of himselfand things as well as their objective forms and surroundings.This he may attempt to do for a time by the power of thecritical and analytic reason which has already carried him so far;but not for very long. For in his study of himself and the world hecannot but come face to face with the soul in himself and the soulin the world and find it to be an entity so profound, so complex,so full of hidden secrets and powers that his intellectual reasonbetrays itself as an insufficient light and a fumbling seeker: itis successfully analytical only of superficialities and of what liesjust behind the superficies. <strong>The</strong> need of a deeper knowledge mustthen turn him to the dis<strong>cover</strong>y of new powers and means withinhimself. He finds that he can only know himself entirely bybecoming actively self-conscious and not merely self-critical, bymore and more living in his soul and acting out of it rather thanfloundering on surfaces, by putting himself into conscious harmonywith that which lies behind his superficial mentality andpsychology and by enlightening his reason and making dynamichis action through this deeper light and power to which he thusopens. In this process the rationalistic ideal begins to subjectitself to the ideal of intuitional knowledge and a deeper selfawareness;the utilitarian standard gives way to the aspirationtowards self-consciousness and self-realisation; the rule of livingaccording to the manifest laws of physical Nature is replaced bythe effort towards living according to the veiled Law and Willand Power active in the life of the world and in the inner andouter life of humanity.All these tendencies, though in a crude, initial and illdevelopedform, are manifest now in the world and are growingfrom day to day with a significant rapidity. And their emergenceand greater dominance means the transition from the rationalisticand utilitarian period of human development whichindividualism has created to a greater subjective age of society.<strong>The</strong> change began by a rapid turning of the current of thoughtinto large and profound movements contradictory of the oldintellectual standards, a swift breaking of the old tables. <strong>The</strong>

30 <strong>The</strong> Human Cyclematerialism of the nineteenth century gave place first to a noveland profound vitalism which has taken various forms fromNietzsche’s theory of the Will to be and Will to Power asthe root and law of life to the new pluralistic and pragmaticphilosophy which is pluralistic because it has its eye fixed onlife rather than on the soul and pragmatic because it seeks tointerpret being in the terms of force and action rather than oflight and knowledge. <strong>The</strong>se tendencies of thought, which haduntil yesterday a profound influence on the life and thoughtof Europe prior to the outbreak of the great War, especially inFrance and Germany, were not a mere superficial recoil fromintellectualism to life and action, — although in their applicationby lesser minds they often assumed that aspect; they were anattempt to read profoundly and live by the Life-Soul of theuniverse and tended to be deeply psychological and subjectivein their method. From behind them, arising in the void createdby the discrediting of the old rationalistic intellectualism, therehad begun to arise a new Intuitionalism, not yet clearly awareof its own drive and nature, which seeks through the forms andpowers of Life for that which is behind Life and sometimes evenlays as yet uncertain hands on the sealed doors of the Spirit.<strong>The</strong> art, music and literature of the world, always a sureindex of the vital tendencies of the age, have also undergone aprofound revolution in the direction of an ever-deepening subjectivism.<strong>The</strong> great objective art and literature of the past nolonger commands the mind of the new age. <strong>The</strong> first tendencywas, as in thought so in literature, an increasing psychologicalvitalism which sought to represent penetratingly the most subtlepsychological impulses and tendencies of man as they started tothe surface in his emotional, aesthetic and vitalistic cravings andactivities. Composed with great skill and subtlety but withoutany real insight into the law of man’s being, these creationsseldom got behind the reverse side of our surface emotions, sensationsand actions which they minutely analysed in their detailsbut without any wide or profound light of knowledge; they wereperhaps more immediately interesting but ordinarily inferior asart to the old literature which at least seized firmly and with a

<strong>The</strong> Coming of the Subjective Age 31large and powerful mastery on its province. Often they describedthe malady of Life rather than its health and power, or theriot and revolt of its cravings, vehement and therefore impotentand unsatisfied, rather than its dynamis of self-expression andself-possession. But to this movement which reached its highestcreative power in Russia, there succeeded a turn towards a moretruly psychological art, music and literature, mental, intuitional,psychic rather than vitalistic, departing in fact from a superficialvitalism as much as its predecessors departed from the objectivemind of the past. This new movement aimed like the new philosophicIntuitionalism at a real rending of the veil, the seizure bythe human mind of that which does not overtly express itself, thetouch and penetration into the hidden soul of things. Much ofit was still infirm, unsubstantial in its grasp on what it pursued,rudimentary in its forms, but it initiated a decisive departure ofthe human mind from its old moorings and pointed the directionin which it is being piloted on a momentous voyage of dis<strong>cover</strong>y,the dis<strong>cover</strong>y of a new world within which must eventually bringabout the creation of a new world without in life and society.Art and literature seem definitely to have taken a turn towardsa subjective search into what may be called the hidden insideof things and away from the rational and objective canon ormotive.Already in the practical dealing with life there are advancedprogressive tendencies which take their inspiration from thisprofounder subjectivism. Nothing indeed has yet been firmlyaccomplished, all is as yet tentative initiation and the first feelingout towards a material shape for this new spirit. <strong>The</strong> dominantactivities of the world, the great recent events such as the enormousclash of nations in Europe and the stirrings and changeswithin the nations which preceded and followed it, were ratherthe result of a confused half struggle half effort at accommodationbetween the old intellectual and materialistic and the newstill superficial subjective and vitalistic impulses in the West.<strong>The</strong> latter unenlightened by a true inner growth of the soul werenecessarily impelled to seize upon the former and utilise themfor their unbridled demand upon life; the world was moving

32 <strong>The</strong> Human Cycletowards a monstrously perfect organisation of the Will-to-liveand the Will-to-power and it was this that threw itself out in theclash of War and has now found or is finding new forms of lifefor itself which show better its governing idea and motive. <strong>The</strong>Asuric or even Rakshasic character of the recent world-collisionwas due to this formidable combination of a falsely enlightenedvitalistic motive-power with a great force of servile intelligenceand reasoning contrivance subjected to it as instrument and thegenius of an accomplished materialistic Science as its Djinn, itsgiant worker of huge, gross and soulless miracles. <strong>The</strong> War wasthe bursting of the explosive force so created and, even thoughit strewed the world with ruins, its after results may well haveprepared the collapse, as they have certainly produced a disintegratingchaos or at least poignant disorder, of the monstrouscombination which produced it, and by that salutary ruin areemptying the field of human life of the principal obstacles to atruer development towards a higher goal.Behind it all the hope of the race lies in those infant andas yet subordinate tendencies which carry in them the seed of anew subjective and psychic dealing of man with his own being,with his fellow-men and with the ordering of his individual andsocial life. <strong>The</strong> characteristic note of these tendencies may beseen in the new ideas about the education and upbringing of thechild that became strongly current in the pre-war era. Formerly,education was merely a mechanical forcing of the child’s natureinto arbitrary grooves of training and knowledge in which hisindividual subjectivity was the last thing considered, and hisfamily upbringing was a constant repression and compulsoryshaping of his habits, his thoughts, his character into the mouldfixed for them by the conventional ideas or individual interestsand ideals of the teachers and parents. <strong>The</strong> dis<strong>cover</strong>y that educationmust be a bringing out of the child’s own intellectualand moral capacities to their highest possible value and must bebased on the psychology of the child-nature was a step forwardtowards a more healthy because a more subjective system; butit still fell short because it still regarded him as an object to behandled and moulded by the teacher, to be educated. But at least

<strong>The</strong> Coming of the Subjective Age 33there was a glimmering of the realisation that each human beingis a self-developing soul and that the business of both parentand teacher is to enable and to help the child to educate himself,to develop his own intellectual, moral, aesthetic and practicalcapacities and to grow freely as an organic being, not to bekneaded and pressured into form like an inert plastic material.It is not yet realised what this soul is or that the true secret,whether with child or man, is to help him to find his deeper self,the real psychic entity within. That, if we ever give it a chanceto come forward, and still more if we call it into the foregroundas “the leader of the march set in our front”, will itself take upmost of the business of education out of our hands and developthe capacity of the psychological being towards a realisation ofits potentialities of which our present mechanical view of lifeand man and external routine methods of dealing with themprevent us from having any experience or forming any conception.<strong>The</strong>se new educational methods are on the straight way tothis truer dealing. <strong>The</strong> closer touch attempted with the psychicalentity behind the vital and physical mentality and an increasingreliance on its possibilities must lead to the ultimate dis<strong>cover</strong>ythat man is inwardly a soul and a conscious power of the Divineand that the evocation of this real man within is the right objectof education and indeed of all human life if it would find and liveaccording to the hidden Truth and deepest law of its own being.That was the knowledge which the ancients sought to expressthrough religious and social symbolism, and subjectivism is aroad of return to the lost knowledge. First deepening man’s innerexperience, restoring perhaps on an unprecedented scale insightand self-knowledge to the race, it must end by revolutionisinghis social and collective self-expression.Meanwhile, the nascent subjectivism preparative of the newage has shown itself not so much in the relations of individualsor in the dominant ideas and tendencies of social development,which are still largely rationalistic and materialistic and onlyvaguely touched by the deeper subjective tendency, but in thenew collective self-consciousness of man in that organic massof his life which he has most firmly developed in the past, the

34 <strong>The</strong> Human Cyclenation. It is here that it has already begun to produce powerfulresults whether as a vitalistic or as a psychical subjectivism,and it is here that we shall see most clearly what is its actualdrift, its deficiencies, its dangers as well as the true purpose andconditions of a subjective age of humanity and the goal towardswhich the social cycle, entering this phase, is intended to arrivein its wide revolution.

Chapter IV<strong>The</strong> Dis<strong>cover</strong>y of the Nation-SoulTHE PRIMAL law and purpose of the individual life isto seek its own self-development. Consciously or halfconsciouslyor with an obscure unconscious groping itstrives always and rightly strives at self-formulation, — to finditself, to dis<strong>cover</strong> within itself the law and power of its own beingand to fulfil it. This aim in it is fundamental, right, inevitablebecause, even after all qualifications have been made and caveatsentered, the individual is not merely the ephemeral physical creature,a form of mind and body that aggregates and dissolves, buta being, a living power of the eternal Truth, a self-manifestingspirit. In the <strong>same</strong> way the primal law and purpose of a society,community or nation is to seek its own self-fulfilment; it strivesrightly to find itself, to become aware within itself of the law andpower of its own being and to fulfil it as perfectly as possible, torealise all its potentialities, to live its own self-revealing life. <strong>The</strong>reason is the <strong>same</strong>; for this too is a being, a living power of theeternal Truth, a self-manifestation of the cosmic Spirit, and it isthere to express and fulfil in its own way and to the degree of itscapacities the special truth and power and meaning of the cosmicSpirit that is within it. <strong>The</strong> nation or society, like the individual,has a body, an organic life, a moral and aesthetic temperament,a developing mind and a soul behind all these signs and powersfor the sake of which they exist. One may say even that, likethe individual, it essentially is a soul rather than has one; it is agroup-soul that, once having attained to a separate distinctness,must become more and more self-conscious and find itself moreand more fully as it develops its corporate action and mentalityand its organic self-expressive life.<strong>The</strong> parallel is just at every turn because it is more than aparallel; it is a real identity of nature. <strong>The</strong>re is only this differencethat the group-soul is much more complex because it has

36 <strong>The</strong> Human Cyclea great number of partly self-conscious mental individuals forthe constituents of its physical being instead of an association ofmerely vital subconscious cells. At first, for this very reason, itseems more crude, primitive and artificial in the forms it takes;for it has a more difficult task before it, it needs a longer time tofind itself, it is more fluid and less easily organic. When it doessucceed in getting out of the stage of vaguely conscious selfformation,its first definite self-consciousness is objective muchmore than subjective. And so far as it is subjective, it is aptto be superficial or loose and vague. This objectiveness comesout very strongly in the ordinary emotional conception of thenation which centres round its geographical, its most outwardand material aspect, the passion for the land in which we dwell,the land of our fathers, the land of our birth, country, patria,vaterland, janma-bhūmi. When we realise that the land is onlythe shell of the body, though a very living shell indeed and potentin its influences on the nation, when we begin to feel that its morereal body is the men and women who compose the nation-unit,a body ever changing, yet always the <strong>same</strong> like that of the individualman, we are on the way to a truly subjective communalconsciousness. For then we have some chance of realising thateven the physical being of the society is a subjective power, nota mere objective existence. Much more is it in its inner self agreat corporate soul with all the possibilities and dangers of thesoul-life.<strong>The</strong> objective view of society has reigned throughout thehistorical period of humanity in the West; it has been sufficientlystrong though not absolutely engrossing in the East. Rulers,people and thinkers alike have understood by their nationalexistence a political status, the extent of their borders, theireconomic well-being and expansion, their laws, institutions andthe working of these things. For this reason political and economicmotives have everywhere predominated on the surfaceand history has been a record of their operations and influence.<strong>The</strong> one subjective and psychological force consciously admittedand with difficulty deniable has been that of the individual. Thispredominance is so great that most modern historians and some

<strong>The</strong> Dis<strong>cover</strong>y of the Nation-Soul 37political thinkers have concluded that objective necessities areby law of Nature the only really determining forces, all else isresult or superficial accidents of these forces. Scientific historyhas been conceived as if it must be a record and appreciation ofthe environmental motives of political action, of the play of economicforces and developments and the course of institutionalevolution. <strong>The</strong> few who still valued the psychological elementhave kept their eye fixed on individuals and are not far fromconceiving of history as a mass of biographies. <strong>The</strong> truer andmore comprehensive science of the future will see that theseconditions only apply to the imperfectly self-conscious periodof national development. Even then there was always a greatersubjective force working behind individuals, policies, economicmovements and the change of institutions; but it worked forthe most part subconsciously, more as a subliminal self thanas a conscious mind. It is when this subconscious power ofthe group-soul comes to the surface that nations begin to enterinto possession of their subjective selves; they set about getting,however vaguely or imperfectly, at their souls.Certainly, there is always a vague sense of this subjectiveexistence at work even on the surface of the communal mentality.But so far as this vague sense becomes at all definite,it concerns itself mostly with details and unessentials, nationalidiosyncrasies, habits, prejudices, marked mental tendencies. Itis, so to speak, an objective sense of subjectivity. As man has beenaccustomed to look on himself as a body and a life, the physicalanimal with a certain moral or immoral temperament, and thethings of the mind have been regarded as a fine flower andattainment of the physical life rather than themselves anythingessential or the sign of something essential, so and much morehas the community regarded that small part of its subjectiveself of which it becomes aware. It clings indeed always to itsidiosyncrasies, habits, prejudices, but in a blind objective fashion,insisting on their most external aspect and not at all goingbehind them to that for which they stand, that which they tryblindly to express.This has been the rule not only with the nation, but with