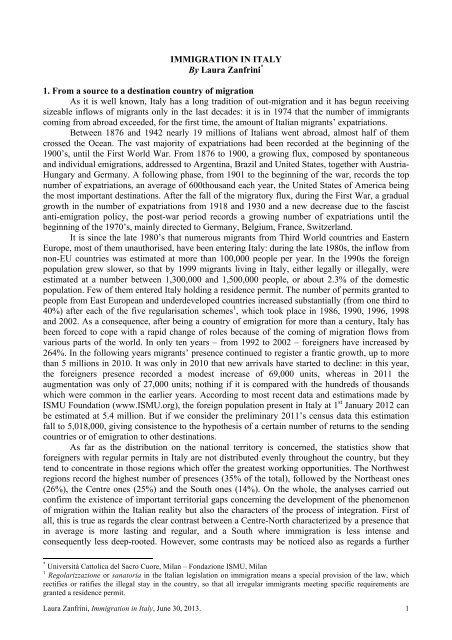

IMMIGRATION IN ITALY By Laura Zanfrini* 1. From a source to a ...

IMMIGRATION IN ITALY By Laura Zanfrini* 1. From a source to a ...

IMMIGRATION IN ITALY By Laura Zanfrini* 1. From a source to a ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>IMMIGRATION</strong> <strong>IN</strong> <strong>ITALY</strong><strong>By</strong> <strong>Laura</strong> Zanfrini *<strong>1.</strong> <strong>From</strong> a <strong>source</strong> <strong>to</strong> a destination country of migrationAs it is well known, Italy has a long tradition of out-migration and it has begun receivingsizeable inflows of migrants only in the last decades: it is in 1974 that the number of immigrantscoming from abroad exceeded, for the first time, the amount of Italian migrants’ expatriations.Between 1876 and 1942 nearly 19 millions of Italians went abroad, almost half of themcrossed the Ocean. The vast majority of expatriations had been recorded at the beginning of the1900’s, until the First World War. <strong>From</strong> 1876 <strong>to</strong> 1900, a growing flux, composed by spontaneousand individual emigrations, addressed <strong>to</strong> Argentina, Brazil and United States, <strong>to</strong>gether with Austria-Hungary and Germany. A following phase, from 1901 <strong>to</strong> the beginning of the war, records the <strong>to</strong>pnumber of expatriations, an average of 600thousand each year, the United States of America beingthe most important destinations. After the fall of the migra<strong>to</strong>ry flux, during the First War, a gradualgrowth in the number of expatriations from 1918 and 1930 and a new decrease due <strong>to</strong> the fascistanti-emigration policy, the post-war period records a growing number of expatriations until thebeginning of the 1970’s, mainly directed <strong>to</strong> Germany, Belgium, France, Switzerland.It is since the late 1980’s that numerous migrants from Third World countries and EasternEurope, most of them unauthorised, have been entering Italy: during the late 1980s, the inflow fromnon-EU countries was estimated at more than 100,000 people per year. In the 1990s the foreignpopulation grew slower, so that by 1999 migrants living in Italy, either legally or illegally, wereestimated at a number between 1,300,000 and 1,500,000 people, or about 2.3% of the domesticpopulation. Few of them entered Italy holding a residence permit. The number of permits granted <strong>to</strong>people from East European and underdeveloped countries increased substantially (from one third <strong>to</strong>40%) after each of the five regularisation schemes 1 , which <strong>to</strong>ok place in 1986, 1990, 1996, 1998and 2002. As a consequence, after being a country of emigration for more than a century, Italy hasbeen forced <strong>to</strong> cope with a rapid change of roles because of the coming of migration flows fromvarious parts of the world. In only ten years – from 1992 <strong>to</strong> 2002 – foreigners have increased by264%. In the following years migrants’ presence continued <strong>to</strong> register a frantic growth, up <strong>to</strong> morethan 5 millions in 2010. It was only in 2010 that new arrivals have started <strong>to</strong> decline: in this year,the foreigners presence recorded a modest increase of 69,000 units, whereas in 2011 theaugmentation was only of 27,000 units; nothing if it is compared with the hundreds of thousandswhich were common in the earlier years. According <strong>to</strong> most recent data and estimations made byISMU Foundation (www.ISMU.org), the foreign population present in Italy at 1 st January 2012 canbe estimated at 5.4 million. But if we consider the preliminary 2011’s census data this estimationfall <strong>to</strong> 5,018,000, giving consistence <strong>to</strong> the hypothesis of a certain number of returns <strong>to</strong> the sendingcountries or of emigration <strong>to</strong> other destinations.As far as the distribution on the national terri<strong>to</strong>ry is concerned, the statistics show thatforeigners with regular permits in Italy are not distributed evenly throughout the country, but theytend <strong>to</strong> concentrate in those regions which offer the greatest working opportunities. The Northwestregions record the highest number of presences (35% of the <strong>to</strong>tal), followed by the Northeast ones(26%), the Centre ones (25%) and the South ones (14%). On the whole, the analyses carried outconfirm the existence of important terri<strong>to</strong>rial gaps concerning the development of the phenomenonof migration within the Italian reality but also the characters of the process of integration. First ofall, this is true as regards the clear contrast between a Centre-North characterized by a presence thatin average is more lasting and regular, and a South where immigration is less intense andconsequently less deep-rooted. However, some contrasts may be noticed also as regards a further* Università Cat<strong>to</strong>lica del Sacro Cuore, Milan – Fondazione ISMU, Milan1 Regolarizzazione or sana<strong>to</strong>ria in the Italian legislation on immigration means a special provision of the law, whichrectifies or ratifies the illegal stay in the country, so that all irregular immigrants meeting specific requirements aregranted a residence permit.<strong>Laura</strong> Zanfrini, Immigration in Italy, June 30, 2013. 1

distinction, transversely <strong>to</strong> geographical coordinates, between large metropolitan provinces, such asRome, Milan, but also Naples, Palermo and Bari, and the so-called “minor provinces”. While theformer stand out because of relatively higher immigrants’ irregularity and density rates, the lattergive sometimes the impression that the phenomenon of migrations takes “second place”, with lowerirregularity levels and greater signals of taking root in the terri<strong>to</strong>ry and in local communities.As far as the single nationalities are concerned, the change in the structure of the foreignpopulation by nationality clearly confirms Italy’s status as an immigration country in which flowsare diversifying and are not just linked <strong>to</strong> a few countries: the number of sending countries is huge(around 200) and many of them are very distant and have never had economic or culturalrelationships with Italy. Nowadays, the largest foreign group is the Romanian (more than onemillion), followed by the Moroccan and the Albanian ones (both around half a million), by theChinese, Ukrainian and Filipino ones. Nevertheless, as it is clearly demonstrated by data reported inTable 1, the composition of the migrants’ presence in Italy has been repeatedly changing duringtime, augmenting the incidence of the European sending countries.Tab. 1 – Foreigners residents in Italy. First ten nationalities (only heavy migration pressure countries) and <strong>to</strong>tal.Years 1971-20111971* 1981* 1991* 2001* 2011**Yugoslavia 6,460 Iran 8,399 Morocco 63,809 Morocco 162,254 Romania 1,110,848Argentina 2,068 Yugoslavia 6,472 Tunisia 31,881 Albania 146,321 Albania 515,808Iran 1,752 Philippines 4,107 Philippines 26,166 Romania 69,999 Morocco 484,288Poland 1,504 Ethiopia 4,048 Yugoslavia 22,335 Philippines 65,073 China 231,199Venezuela 1,477 Egypt 3,139 Senegal 21,073 China 60,143 Ukraine 209,575Brazil 1,406 India 2,535 Egypt 14,183 Tunisia 45,972 Philippines 142,906India 1,057 Jordan 2,411 China 12,998 Yugoslavia 40,151 Moldova 136,675Syria 975 Cape Verde 2,168 Poland 10,933 Senegal 39,170 India 131,001Turkey 930 Libya 2,080 Brazil 9,364 Sri Lanka 33,789 Poland 125,110Libya 860 Argentina 2,018 Sri Lanka 8,747 Egypt 32,381 Tunisia 113,251Total 143,838 Total 198,483 Total 548,193 Total 1,379,749 Total 4,744,290* Data reported refer <strong>to</strong> the number of foreigners possessing a valid permit of stay.** Data reported refer <strong>to</strong> an estimation made by ISMU Foundation of foreigners regularly living in Italy.Source: Interior Ministry for the years 1971-2001; ISMU Foundation for the year 201<strong>1.</strong>The increase of the permanently settled immigrant population is responsible for therebalancing in the gender composition of different national groups; for the growth of the share ofthe foreign population under the age of 18; for the considerable increase of the numbers ofmarriages and above all for foreign citizens births.Even if the gender composition of the different national groups shows the variety ofmigra<strong>to</strong>ry models (with the two extremes, among the major communities, represented by Senegal,with 75.6% of males and Ukraine, with 79.8% of females), as the years go by we can observe a rebalancingtrend. In general terms a good equilibrium was already notable in 1997: males constituted55.2% and females 44.8% of the <strong>to</strong>tal number of foreigners present in Italy. In 2002, a completebalance was almost reached, with males constituting less than 52% of the <strong>to</strong>tal.An other interesting phenomena is represented by demographic events. Marriages in whichone or both persons were foreign accounted for 13% (26,617, among those the majority – 14,799 –is represented by the unions of an Italian man with a foreign woman) of all marriages contracted in2011 (but the divorce rate for marriages involving foreigners was twice as high).In the second half of the 1980s the proportion of foreign children born in Italy was only<strong>1.</strong>1% of the <strong>to</strong>tal number of births; this proportion has reached 4.5% in 1996, 9.4% in 2006 and14.5% in 2011: this figure is probably the most important indica<strong>to</strong>r that a significant proportion offoreigners is in the process of settlement on a permanent basis. In 2011, 105,975 new births (19.4%of the <strong>to</strong>tal new births) had at least one foreign parent; 21,213 an Italian father and a foreign motherand 5,501 an Italian mother and a foreign father.<strong>Laura</strong> Zanfrini, Immigration in Italy, June 30, 2013. 2

The about 50,000 minors registered by the 1991 census survey rose up <strong>to</strong> 284,000 units tenyears after, and further increased up <strong>to</strong> reach 502,000 units as <strong>to</strong> January 1 st 2005 and 993,238 unitsas <strong>to</strong> January 1 st 201<strong>1.</strong> Among those, the “Italians by birth” (albeit still foreigners) are half amillion, representing a proportion of about 60% of the <strong>to</strong>tal of foreign minors.Also the percentage of foreign minors attending the Italian school has been in uniform andconstant growth. In 1983/84 there were only 6,104 pupils with a non-Italian citizenship in theItalian schools (0.06% of the <strong>to</strong>tal); ten years later (1993/1994) they were 37,478 (0.41% of the<strong>to</strong>tal); in 2003/2004 they reached the amount of 282,683 (3.49% of the <strong>to</strong>tal), and in 2011/2012 (themost recent data available) they reached the number of 755,939 (8.4% of the <strong>to</strong>tal). <strong>From</strong> thebeginning of the century the yearly growth rate has not ceased <strong>to</strong> rise, sextupling over a decade [cf.Table 2]. Nowadays, the phenomenon has become stable and a slower growth can be noticed. Boththe higher number of foreign students (266,671) and the higher percentage on the <strong>to</strong>tal (9.5%) arerecorded in the primary school. Moreover, if the general trend is characterized by a slowdown in theincrease of students with non-Italian citizenship, there is a progressive transformation in thecomposition of the foreign school population, with a significant growth in the number and incidenceof those born in Italy from foreign parents (who often register the same educational performances astheir Italian mates) and a decrease in the number and incidence of newcomers (this latter being themost vulnerable category, needing a specific attention). Typical of the Italian context is finally theheterogeneity of nationalities. When comparing the largest groups of foreigner citizens present inthe Italian schools, it emerges that the most consistent quota of minors comes from Romania with141,050 students, followed by Albania with 102,719 students, Morocco (95,912), China (34,080),and Moldova (23,103). As for the scholastic legislation, the choice made by Italy is that of investingin interculturalism and in education <strong>to</strong> foster dialogue and coexistence within multicultural schoolcontexts, according <strong>to</strong> the direction indicated by the European Union. The ministerialpronouncements emphasise the complementarity of directives, which include integration of foreignstudents and intercultural exchanges in curricular and extracurricular activities.Tab. 2 – Students with non-Italian citizenship in the Italian school system. Years 1999/2000 – 2011/12School year N. of non-Italian students Per 100 students1999/00 119,679 <strong>1.</strong>42000(01 147,406 <strong>1.</strong>82001/02 196,414 2.22002/03 239,808 2.72003/04 307,141 3.52004/05 370,803 4.22005/06 431,211 4.82006/07 501,420 5.62007/08 574,133 6.42008/09 629,360 7.02009/10 673,592 7.52010/11 711,046 7.92011/12 755,939 8.4Source: Ministry of Education, ISMU Foundation.Finally, a crucial problem in the debate on immigration in Italy has been always representedby irregular immigration. Very rarely, however, has such a problem been dealt with the necessaryinstruments, which involve the availability of correct data about the real proportions of the problemitself, its structural features and distribution on the Italian terri<strong>to</strong>ry. It was only in the late 1980s thatthe first official estimates, produced by ISTAT (National Institute of Statistics) concerning thephenomenon were made public. The figures referring <strong>to</strong> the irregular immigrants were estimated asrunning as high as 500,000: in other words, one out of two immigrants was an irregular. Such afigure was significantly reduced when the first comprehensive law on immigration came in<strong>to</strong> force(law 39/90) and 220,000 new residence permits were issued as a result of the 1990 regularization. In<strong>Laura</strong> Zanfrini, Immigration in Italy, June 30, 2013. 3

migration industry. Irregular migration <strong>to</strong> Italy represents only a piece of a larger mosaic – such asthe phenomenon of persons’ mobility – which, as everybody knows, has been assuming a planetarycharacter and extent, with compositions and directions that have became increasingly unrelated <strong>to</strong>migration policies. Furthermore, Italy’s configuration and geographical position make it a nervecentre for illegal migration from the Mediterranean and Balkan areas, even though merely in transit<strong>to</strong> other European countries.In the particular case of migration from east European countries – from which the largestflows have originated, especially during the 2000s, – there are many incentive fac<strong>to</strong>rs, but migrationpressure has been driven by the deep changes in these societies along with the passage <strong>to</strong> marketeconomy. These fac<strong>to</strong>rs also depend on economic integration with EU member countries, that hasalready become tangible in several ways: through a process of production unit relocation carried outby several Italian enterprises; through geographical closeness and the ability <strong>to</strong> relatively easilyobtain entry visas; through the attractive power exerted by ethnic networks, which are not yet in theposition <strong>to</strong> organise their co-nationals’ legal immigration on a large scale, but at the same time arestill tempted <strong>to</strong> make a profit from the great amount of emigration candidates; and in the perception– especially among the female component – of a relative abundance of informal job opportunities insupporting Italian families.On the other hand, ethnic networks play a role that goes far beyond the migration flows fromeastern countries. An analysis of the results of the different regularisation provisions seems <strong>to</strong>confirm that in most cases illegal flows are generated by the same reasons that drive regularmigrations and not because some national groups are particularly inclined <strong>to</strong> avoid ordinary entryprocedures. Contiguity with the industry of illegal immigration and human trafficking forexploitation, calling systems on a family and community basis, and mechanisms of emulatingemigrated co-nationals are some of the fac<strong>to</strong>rs that contribute <strong>to</strong> make ethnic networks a strategicelement in providing migration flows with a self-propulsive dynamics. The 2002 big regularisationmade this role particularly visible: we need only think that 11% of regularisation applications weresubmitted by foreign employers, quite often belonging <strong>to</strong> the same community of the worker <strong>to</strong> beregularised; the Chinese community alone submitted about 23,000 regularisation applications. Inthe following years, the advent of a sort of “demandist” orthodoxy – according <strong>to</strong> which the mereexistence of an employer, real or fake, willing <strong>to</strong> hire a migrant would determine a right <strong>to</strong> entry or<strong>to</strong> be regularized – has contributed <strong>to</strong> overestimate actual employment opportunities and <strong>to</strong> neglectthe basic element of the self-propelling nature of migrations, that is <strong>to</strong> say, their tendency <strong>to</strong>become, over time, relatively independent both of law constraints, and of integration chances in thehost society. Actually, the “culture of illegality” is deeply rooted in the culture of migration ofmany migrants’ communities living in Italy (and even in the organizational cultures of many privateand public agencies that deal with immigrants), as a consequence of their ample familiarity with theblack market labour [see § 3].In reality, the major attractive fac<strong>to</strong>r for illegal immigration has undoubtedly been theshadow economy spreading and taking root, a phenomenon characterising the whole country, butwhich has some peculiar regional and sec<strong>to</strong>ral features. In absolute values, the northern regions,thanks <strong>to</strong> their abundance of job opportunities, take the great majority of undocumented migrants.Nonetheless, it is in the southern regions that irregularity becomes a sort of “normal” element in aninstitutional development and operational model that we might define as a “widespread illegalitymodel”. In those regions, infringements of labour regulations have structural features showingvarious levels of seriousness and can even lead <strong>to</strong> the establishment of “phan<strong>to</strong>m” enterprises thatfind in illegal immigration a particularly profitable recruitment area.In the particular case of agriculture, immigrants’ concealed labour is included in a system ofmutual benefits involving employers, new immigrants and, for some aspects, local workers whoenjoy public unemployment benefits. This system is encouraged by the high terri<strong>to</strong>rial mobility ofthe immigrant workforce, which during the year moves from one region <strong>to</strong> another (the “seasonalworkers’ circuit”) following the calendar of fruit and vegetable production. Immigrants’ propensity<strong>Laura</strong> Zanfrini, Immigration in Italy, June 30, 2013. 5

<strong>to</strong> abandon this sec<strong>to</strong>r and move <strong>to</strong> regions that offer better-paid job opportunities constantlyregenerates the demand for labour, which finds in irregular and illegal immigration a “natural”answer.In the economically more dynamic regions, immigrants’ irregular employment is insteadcontiguous <strong>to</strong> a general tendency <strong>to</strong> multiply “bad jobs” and make job relations precarious, andmixed up with an impudent use of only apparently legal contractual solutions. The case of thebuilding industry, a sec<strong>to</strong>r which collects a significant part of irregular immigration andemployment, is particularly impressive, as this is a sec<strong>to</strong>r in which outsourcing logics moreevidently have gone along with labour precariousness. In low-qualification services, and in thewhole area of “bad jobs”, concealed labour may be described as the last stage of a dismantlingaction carried out on the typical institutions and rights of the société salariale, where immigrants’labour discrimination and underpayment easily give rise <strong>to</strong> social dumping phenomena.Because of the rigid link in law between occupational condition and residence rights, theinformalisation of job relations has ended by being strictly connected with migration dynamics. Onthe one hand, because it has attracted new irregular flows driven by the belief that people will easilyfind a place in the shadow economy. On the other hand, by exposing regular immigrants <strong>to</strong> the riskof not obtaining, on expiry, a residence permit extension, the law has contributed <strong>to</strong> the socialconstruction of irregularity, on which Italian researchers have focused for a long time. It is thisstrict connection sanctioned by law between job condition and residence right, sealed by theprovision for a “residence contract” (contrat<strong>to</strong> di soggiorno) that leads <strong>to</strong> an outcome that is just theopposite of what was expected.Finally, we must add that a chronic lack of inspection activities and a substantial nonapplicationof sanctions (some of a penal nature), which the law instead provides for those whoemploy irregular migrants, <strong>to</strong>gether make the law quite ineffective as a potential discouragement.This is even more valid for home help and carer jobs in families, where the decisive fac<strong>to</strong>rs leading<strong>to</strong> irregularity mostly depend on a family need <strong>to</strong> limit the cost of those services, the urgency withwhich these needs reveal themselves, the ease of concealing a worker’s presence, the rarity ofchecks or inspections, a lack of institutionalisation, a lack of deterrent public policies, and the factthat this market represents a “normal” outlet for newcomers who come <strong>to</strong> Italy illegally or with a<strong>to</strong>urist visa: these are the major reasons that almost physiologically expose this sec<strong>to</strong>r <strong>to</strong> the risk ofinformality. On the other hand, expulsion provisions are normally used for the safeguard of publicorder and not as a strategic <strong>to</strong>ol <strong>to</strong> fight irregular immigration and employment. This circumstanceheavily affects its deterrent value, even during the stages that seem politically less “friendly” <strong>to</strong>migrants.Notwithstanding its present dimensions, the phenomenon of irregularity has stronglyinfluenced migrants’ relations with the institutions of the Italian society, their inclusion processes inthe welfare structures (up <strong>to</strong> cause their “informalization”, that is, their actual opening also <strong>to</strong> nonentitledparties when safeguard requirements deemed fundamental are at stake), as well as theimmigrants’ image spread by mass media. The formal system of rights and controls, whichregulates immigration for economic and humanitarian reasons, goes along, in fact, with an informalsystem of employment, social support, “<strong>to</strong>lerance” <strong>to</strong>wards irregular presence and labour.Furthermore, any legisla<strong>to</strong>r’s action aimed at renewing the juridical framework concerningimmigration has unavoidably been followed by an amnesty, which has always been announced bythe public authority as the last one, with the wish that the new regulations would preventreconstructing another area of irregularity over time. A wish that clearly has not come true, sinceinstead, the recurrence of regularization measures – <strong>to</strong>gether with the transformation of the planningdecrees in<strong>to</strong> their functional equivalent – may have actually contributed <strong>to</strong> de-legitimize thenormative structure, and strengthen the belief that both the Italian borders and the Italian society areextremely “porous” with respect <strong>to</strong> irregular immigration.The migration “normalization” process, certified by its indissoluble ties with the everydaylife of the Italian society (and by the fact that it is perceived in this way by the public opinion), has<strong>Laura</strong> Zanfrini, Immigration in Italy, June 30, 2013. 6

ultimately kept up with a repeated resort <strong>to</strong> “exceptional” regularization actions. The number ofmigrants who have been “regularized” is so important as <strong>to</strong> significantly weigh not only upon theresident foreign population volume, but also upon the whole population itself. An overwhelmingmajority of regular migrants who live and work in Italy have been through an irregular approachwith the country and by a more or less long permanence in illegal conditions. Quite often, eventhose who have always been regular migrants succeeded in migrating thanks <strong>to</strong> the presence of arelative who had passed <strong>to</strong> legality through an amnesty. This datum alone provides tangibleevidence of the failure of sovereignty, or better, of its central manifestation, which in thecontemporary international juridical paradigm is represented by control on migration flowmovements. The price that the Italian society is going <strong>to</strong> pay represents a dangerous discredit of theprinciple of legality, with all the consequences that this implies for the social cohesion.3. The evolution of Italian legislationTraditionally an emigration country <strong>to</strong>wards America, Australia and Northern Europe, Italyexperienced a migration turning point between the late 1970s and the early 1980s, that is, during apeculiar stage of the his<strong>to</strong>ry of international migrations, characterized by the rise of restrictivepolicies, and particularly, by the closing of the traditional Central-North-European destinationareas. The role of his<strong>to</strong>rical and political fac<strong>to</strong>rs in structuring migration flows has been by far lessimportant than in other European countries with an earlier migration tradition. Those migrationflows were in fact “spontaneous”, and migrants began <strong>to</strong> flow independently of any activerecruiting policy, usually with no links with the colonial past, attracted by the relative facility withwhich they could enter the country and stay despite an irregular status, and by the possibility <strong>to</strong>mask the real motivations of their permanence, considering Italy’s <strong>to</strong>urist vocation. Along withoffering many opportunities <strong>to</strong> include those migrants in shadow economy, this phenomenoncontributed <strong>to</strong> further increase a widespread irregularity, in terms of persons’ presence and labour,and was destined <strong>to</strong> weigh for a long time upon integration processes <strong>to</strong> such an extent as <strong>to</strong> beidentified as one of the distinctive features of what was later called, by some authors, the“Mediterranean immigration model”. It <strong>to</strong>ok several years <strong>to</strong> make Italy, as well as the other South-European countries, aware of its new role within the international migration system, and an evenlonger time before it recognized the existence of requirements for imported labour, considering thesudden turnabout of its demographic trends. In a situation of overall normative and institutionaldeficit, which characterized Italy’s migration transition, lay and religious associations andorganizations acted as real substitutes for an insufficient and inadequate public intervention action(<strong>to</strong> such an extent that several scholars talk about a situation of “functional overload” in charityorganizations, which were obliged <strong>to</strong> make themselves responsible also for tasks that did notconcern them).Juridical vagueness has thus become a basic element in the structure of the relationsbetween immigrants and Italian society. In fact, the first law on immigration dates back <strong>to</strong> 1986,that is, more than ten years after the “turning point” of 1974 (the year in which, as we have seen, forthe first time the number of incoming foreigners exceeded that of the Italians who emigratedabroad). Law 943/1986, besides establishing an entry and access mechanism <strong>to</strong> the labour market(which however remained substantially not enforced), granted equal protection <strong>to</strong> Italian andforeign workers, and acknowledged <strong>to</strong> the latter a few social rights, including the right <strong>to</strong> familyreunifications. Broader was the reach of the so-called “Martelli Law” (Law 39/1990), which besidesintroducing a yearly flow planning system, also laid down some regulations concerning foreigners’legal protection, expulsion, asylum, and self-employment.The first organic set of rules came only in 1998, through the passing of the “Napolitano-Turco” Law (Law Decree 286/98), which was also the fruit of the pressures of third-sec<strong>to</strong>rinstitutions and civil society. In countertendency with the juridical frame prevailing in Europe inthose years, this law acknowledged, along with pull fac<strong>to</strong>rs in the sending countries, also theexistence of attraction elements strictly connected with Italy’s economic requirements for imported<strong>Laura</strong> Zanfrini, Immigration in Italy, June 30, 2013. 7

workforce, by providing for a special mechanism aimed at determining every year the requiredincoming immigration quotas for labour purposes (in addition <strong>to</strong> the flows for family orhumanitarian reasons, which are unpredictable and cannot be planned). Apart from those reasons,these measures are based on four fundamental principles, which describe the “Italian integrationmodel” (according <strong>to</strong> the definition formulated by the Commission for Integration instituted by theGovernment):a. Interaction based on security: the law provides for a set of <strong>to</strong>ols aimed at combating irregularimmigration, carrying out expulsions, fighting criminality and human being trafficking;b. Safeguard of personal rights extended <strong>to</strong> irregular migrants: the law provides for compulsoryeducation granted <strong>to</strong> all foreign children, regardless of their residence title; in addition, itguarantees essential healthcare also <strong>to</strong> irregular migrants and introduces a residence permitissued for social protection purposes in order <strong>to</strong> safeguard the victims of trafficking;c. Regular migrants’ integration: the law ratifies the same civil and social rights as those granted<strong>to</strong> Italian citizens, acknowledges the right <strong>to</strong> family reunifications and introduces the institutionof a residence paper (carta di soggiorno, a permanent right <strong>to</strong> stay in the country), which canbe obtained by those who have achieved a residence seniority in Italy of five years at least;d. Pluralism and communication: the law respects cultural differences also through the safeguardof the language and the culture of the country of origin; at the same time, it acknowledges theright <strong>to</strong> literacy; finally, it provides for the involvement of voluntary organizations in carryingout integration policies.The integration model outlined by the legisla<strong>to</strong>r shows considerable openings <strong>to</strong> socialrights, but a substantial closure in terms of political rights. In addition, an anachronistic law oncitizenship, passed in 1992 and based on the descent principle, emphasizes the “familistic” andabscriptive characteristics of the Italian model. Because of the legislation in force and thefunctioning of the procedures, the grant of citizenship (except for the case of marriage) requiresvery long implementation times both for immigrants and for their children. Moreover, theprocedures in this regard are still rather uncertain. Face <strong>to</strong> face with a growing stabilised migrantpopulation, there are several million adults permanently residing in Italy without any political rightand destined <strong>to</strong> remain in this condition for a long time.Actually, the most relevant limits do not refer so much <strong>to</strong> the text of the law, but rather <strong>to</strong> itsactual enforcement. The debate which preceded and followed the passing of the Consolidated Actwas monopolized by the theme of security, meant both as border controls and as fight againstcriminality attributed <strong>to</strong> foreigners, as well as by a very strong media exposure of the wholemigration question. Those circumstances diverted the public opinion’s attention from somequalifying aspects of this law, such as the introduction of a residence paper, implemented howeverwith great delay, and the norms concerning fight against discrimination, which from a certain poin<strong>to</strong>f view, “go beyond” the directions of the European Union (insofar as they extend the principle ofequal treatment also <strong>to</strong> citizens from third countries). Along with the well-known farrago andineffectiveness of the Italian bureaucracy – made even more evident by the impact with migrants –several researchers have noticed in norm application an excessive administrative discretion, andquite often, a considerable terri<strong>to</strong>rial diversification in the treatment reserved by the publicadministration <strong>to</strong> immigrants, further increased by an opera<strong>to</strong>rs’ and managers’ insufficientinformation and sensitization action. The number of convictions concerning crimes with racialdiscrimination purposes is negligible, for the time being, also because foreigners, and particularlyirregular migrants, tend for different reasons not <strong>to</strong> denounce the episodes, quite often committedby other foreign subjects, of which they are the victims. This turns also in<strong>to</strong> a lack of a sufficientlyabundant case law <strong>to</strong> which reference can be made. Furthermore, the establishment of a contactcentre against racial discrimination at the President’s Office of the Council of Ministers does notseem <strong>to</strong> have had an impact as significant as that of similar services implemented in other countries.Finally, by analyzing migrants’ inclusion processes, the consequences of the peculiarities of theItalian welfare system cannot be neglected, since its strongly “familistic” characterization penalizesthe subjects who cannot rely on the support of family and neighbouring ties. Therefore, the right <strong>to</strong>equal treatment granted <strong>to</strong> foreign and Italian subjects in acceding any re<strong>source</strong> and social<strong>Laura</strong> Zanfrini, Immigration in Italy, June 30, 2013. 8

opportunity clashes with a situation of widespread discrimination (especially as regards somesec<strong>to</strong>rs of society, such as the real-estate market) and with a socially shared expectation that aprivileged access <strong>to</strong> re<strong>source</strong>s and opportunities should be reserved <strong>to</strong> the local population.Consequently, if on the one hand, Italian citizens have become increasingly aware of the usefulnessof immigrant labour, on the other hand, they are still convinced that Italians are those who are firstentitled <strong>to</strong> benefit from certain rights and services.For some aspects, the “Bossi-Fini” Law, passed in 2002, has acknowledged thesesubordinate incorporation expectations by:a. limiting entry possibilities (through abolition of entry possibilities aimed at allowing migrants<strong>to</strong> go in search of a job, reintroduction of the principle of local workforce unavailability aimedat filling some jobs for which an authorization <strong>to</strong> a foreigner’s entry is required, restriction ofthe criteria regulating family reunifications);b. introducing some restrictions concerning immigrants’ permanence, which in any case resultsmore strictly bound <strong>to</strong> being in possession of a job contract (besides the abolition of entriesaimed at allowing migrants <strong>to</strong> go in search of a job, this law has also reduced residence permitduration – particularly in the case of unemployment);c. increasing penalties and measures aimed at fighting irregular immigration, through theintroduction of a new kind of crime in the case of a further migrant’s irregular entry in theItalian terri<strong>to</strong>ry after expulsion, the provision for forced expulsion in case of irregularpermanence, the extension of “administrative detention” (which may arrive <strong>to</strong> 60 days).Finally, in 2008 the Government included new amendments in the so-called security package(pacchet<strong>to</strong> sicurezza), which identified a new kind of crime (so-called “rea<strong>to</strong> di clandestinità”)consisting in illegal entry/residence in the terri<strong>to</strong>ry of State and extended <strong>to</strong> 18 months the period ofdetention in special centres (CIE – Centres for Identification and Expulsion) waiting for themigrant’s actual compulsory expulsion. These new rules provoked a sharp debate and were accused<strong>to</strong> infringe some fundamental human rights; actually, they were revised in 2011 following apronouncement of the European Court of Justice.According <strong>to</strong> our opinion, one of the most vulnerable point in the juridical regulations onimmigration still in force consists in the distance between the norms that regulate entries for labourpurposes and the actual procedures through which usually migrants’ economic inclusion is carriedout. Despite the troubled preparation process undergone by the entry management system in force,and the important number of granted authorizations (quotas) over time 2 , which has made Italy oneof the major countries officially importing workforce [cf. Table 3], still there is a worrisome gapbetween granted authorizations and actual number of immigrants who enter every year the Italianlabour market without holding a residence permit in the position <strong>to</strong> allow them working regularly.Tab. 3 – Planning evolution. 1995-2012Non-seas.workersSeasonalworkersAu<strong>to</strong>nomousworkersPrivilegedquotas*Of whichSpecificcategories**Search ofjob1995 15,000 10,000 - - - - 25,0001996 10,000 13,000 - - - - 23,0001997 20,000 - - - - 20,0001998 54,500 - 3,500 6,000 - - 58,0001999 54,500 - 3,500 6,000 - - 58,0002000 66,000 2,000 18,000 - 15,000 83,0002001 27,000 39,400 2,000 15,000 5,000 15,000 89,4002002 14,000 60,000 3,000 63,600 2,500 - 79,5002003 9,700 68,500 - 72,300 1,300 - 79,5002004 46,500 66,000 - 106,400 3,000 - 115,0002005 115,500 45,000 - 145,500 18,500 - 179,0002006 558,500 80,000 - 288,500 51,500 - 690,0002007 167,000 80,000 3,000 127,100 112,900 -- 252,0002 We must also note that the admission of specific categories of workers (in particular professional nurses <strong>to</strong> beemployed in public and private healthcare structures) is not limited by the quotas system.<strong>Laura</strong> Zanfrini, Immigration in Italy, June 30, 2013. 9Total

2008 150,000 80,000 -- 44,600 105,400 230,0002009 80,000 -- -- -- -- 80,0002010 80,000 4,000 36,000 -- 120,0002011 98.080 60,000 -- 68,080 30,000 -- 158,0802012 11,850 35,000 2,000 -- -- -- 48,8502013*** -- 30,000 -- -- -- -- 30,000*Quotas assigned <strong>to</strong> countries which are expected <strong>to</strong> cooperate in contrasting irregular migrations. Including quotasassigned <strong>to</strong> new EU countries. They are comprised or not comprised, depending on the year, in the <strong>to</strong>tal amount ofseasonal and non seasonal entries.**Categories such as professional nurses, managers, IT experts, house helpers and care givers.***Updated May 2013.Source: ISMU Documentation Center.According <strong>to</strong> several researchers and key informants, this gap is the outcome of threedifferent fac<strong>to</strong>rs: a) a quota restriction policy, which has resulted undersized not only in relation <strong>to</strong>the migration pressure from abroad, but also <strong>to</strong> the requirements declared by the economic system;b) law procedures that scarcely reconcile themselves with the urgency characteristics through whichthe demand for workforce reveals itself, and in general, with the procedures through which labourdemand and offer meet within a post-Fordist economic system, where labour demand is pulverizedand a relevant share of imported labour offer is absorbed by families and micro-production units; c)above all, spreading and rootedness of shadow economy, which represents an enormous absorptionreservoir for immigrants’ concealed labour, disregarding the effect of further increasing it, related <strong>to</strong>migration dynamics themselves (considering that, according <strong>to</strong> the Italian law, the possibility <strong>to</strong> beregularly employed is excluded for those who are not in possession of a valid and effectiveresidence permit) (cf. § 2).Furthermore, the years before the beginning of the crisis coincided with the advent of a sor<strong>to</strong>f “demandist” orthodoxy: as we have already observed, besides other consequences, it hascontributed <strong>to</strong> underestimate the migrations’ tendency <strong>to</strong> become, over time, relatively independentboth of law constraints, and of integration chances in the host society. Not surprisingly, the jobapplications submitted on the occasion of the last flows decrees – after the beginning of the crisis –seem <strong>to</strong> have lost any correspondence with the actual size of imported workforce requirement. Theirnumber and characteristics (considering the difficult economic phase) are sufficient <strong>to</strong> prove theartificial character of most of the alleged demand for immigrant labour, as well as the inevitabledisadvantage suffered by those candidates who wish <strong>to</strong> comply with the legal procedures, patientlywaiting for the approval of a decree <strong>to</strong> plan their entry in<strong>to</strong> Italy.Conclusively, the serious employment crisis has removed the veil of hypocrisy that hasalways accompanied the “planning of the admissions”: while formally aimed at addressing theneeds of the economy, the planning decrees quickly turned out <strong>to</strong> be functional equivalents ofamnesties and, more recently, instruments <strong>to</strong> grant legal entry under the justification of fictitiousemployment relationships simulated by friends and fellow-countrymen or bought at a high pricein the criminal market. To summarize, the recession gave the coup de grace <strong>to</strong> a legislativeframework that has not met any of its objectives; certainly not that of preventing illegal arrivals, butneither that of satisfying the needs of the employers, nor, even less, that of managing the flow ofworkers from abroad in accordance with a plan aimed at enhancing the competitiveness ofenterprises and <strong>to</strong> guarantee social cohesion.4. The insertion in the labour marketAs it is well known, between the late 1960s and the early 1970s, the major Europeandestination countries put an end <strong>to</strong> active recruitment policies. The oil shock in 1973 marked thedefinitive conclusion of the previous stage: from then onwards, migrations began <strong>to</strong> put on thecharacter of “undesired” presences, either <strong>to</strong>lerated or rejected, depending on circumstances, but inany case increasingly less legitimated by economic needs. Immigration, more and more manifestlynot depending on planning policies any longer, began <strong>to</strong> be depicted as an emergency from which<strong>Laura</strong> Zanfrini, Immigration in Italy, June 30, 2013. 10

European societies have <strong>to</strong> defend themselves. It was actually during that period, dominated byrestrictive policies and spontaneous migrant flows, that South-European countries, at the head ofwhich was Italy, began their transformation in<strong>to</strong> destination areas for heterogeneous flows arrivedout of any active recruitment policy, and destined <strong>to</strong> be introduced in the numerous niches of aneconomy that just in that period knew its transition <strong>to</strong> post-Fordism.The particular stage in which Italy knew its migra<strong>to</strong>ry transition did considerably weighupon the analyses dedicated <strong>to</strong> this theme. In the other European countries, immigration had beenstudied as an industrial phenomenon, which involved themes and problems connected <strong>to</strong> classrelations and industrial clash, identification processes with the working class, the relationshipbetween local and immigrant workers, trade union actions, social mobility strategies, and socialmovements. The social integration of immigrants and of their families, and all the problemsassociated with inter-ethnic coexistence started <strong>to</strong> attract the attention of both researchers andgovernmental authorities at a later stage, as soon as immigration began <strong>to</strong> transform itself from asubstantially economic matter in<strong>to</strong> a political one. To some extent, in the Italian case this processwas opposite, since the economic functionality of immigration was far from being taken forgranted. Thanks <strong>to</strong> the first studies, carried out in several local realities, it was possible <strong>to</strong> outline amap, albeit fragmentary and incomplete, of immigrant work. <strong>From</strong> the Tunisians employed in thefishing industry at Mazara del Vallo (Sicily) <strong>to</strong> the thousands of seasonal labourers working in theMediterranean agricultural industry, from the street vendors wandering from the Salen<strong>to</strong> <strong>to</strong> theRomagna Riviera <strong>to</strong> the large crowds of women working as domestic helpers in the cities, and soon, up <strong>to</strong> the first experiments of immigrants’ inclusion in some industrial districts in EmiliaRomagna and their early entrepreneurial activity forms. The first two regularizations, launchedrespectively in 1986 and 1990, allowed the emergence of dozen of thousands work relations, butmost of all allowed newly regularized workers <strong>to</strong> gain access <strong>to</strong> the opportunities that in themeantime had opened in the Italian labour market, or more precisely, in the northern part of thecountry. In confirmation of the chronic dualism characterizing the national economy, researchersidentified that a mobility process inside the country was in progress, following the direction of the1950s and 1960s migrations from the south <strong>to</strong> the north of the country. Provinces such as Bergamo,Brescia, Modena, Reggio Emilia, Verona, Vicenza, Tren<strong>to</strong>, Treviso (besides, obviously, Milan),characterized by a widespread economic welfare, unemployment rates much below the nationalaverage, a growing access <strong>to</strong> secondary and tertiary education, thus making workers’ turnoverincreasingly problematic. And just in those local realities a peculiar integration model began <strong>to</strong> takeshape (along with the typical urban model, characterized by a prevalence of the tertiary industryproviding services <strong>to</strong> enterprises and families and by a marked foreign presence “feminization”),whose ideal-type figure is the immigrant worker employed in small and medium enterprises,particularly in the metal-mechanical and building industries. On the basis of those empiricalevidences, several authors identified different terri<strong>to</strong>rial models of immigrants’ integration, whereimmigration was assumed as a sort of “litmus test” of the peculiar characteristics of local labourmarkets. The second significant heritage of that season is the idea of complementarity between localand immigrant labour force, an idea almost unanimously shared by researchers despite thepersisting employment difficulties for an absolutely non-negligible share of the Italian labour force,and motivated referring <strong>to</strong> the growing au<strong>to</strong>nomy of the domestic labour supply.The idea of complementarity will begin a sort of axiom in the analysis of migrants’ role inthe Italian labour market. In any case, <strong>to</strong> understand phenomena that have been increased farbeyond all expectations, it is necessary <strong>to</strong> take in<strong>to</strong> account some characters of Italian economicsystem:- The very high incidence of non-qualified and manual workers within the employment and thenew hirings. In all advanced economies, the advent of the service society had stimulated thegrowth of non-qualified jobs – often “bad jobs” – largely filled by migrant workers. But in Italythis demand is also fed by traditional sec<strong>to</strong>rs, and it often concerns skilled manual workers, evenmore difficult <strong>to</strong> recruit. Heavy jobs, mobility depending on building yard transfer, exposure <strong>to</strong><strong>Laura</strong> Zanfrini, Immigration in Italy, June 30, 2013. 11

climatic/environmental conditions, relative job uncertainty, represent the major fac<strong>to</strong>rs, whichdrive young Italians away from the building industry, even those who are not in possession ofany training credit, and generate a strong demand for migrants <strong>to</strong> be employed as masons,manual workers, carpenters, and assemblers: actually, foreigners’ employment in the buildingsec<strong>to</strong>r is more than twice as high as Italians’. In the metal and mechanical industry, well-knownare the recruitment problems deriving from the disaffection with fac<strong>to</strong>ry work shown by thenew generations entering the labour market: actually, a large part of predicted hiring of migrantsconcerns skilled workers, plant opera<strong>to</strong>rs and unskilled personnel;- The Italian model of social protection that, as it is known, represents the “familistic” varian<strong>to</strong>f welfare regimes. Having <strong>to</strong> face the growing care demand determined by the population’sageing process, Italian families have increasingly resorted <strong>to</strong> migrant workers (largely female),<strong>to</strong> the point <strong>to</strong> give birth <strong>to</strong> a “parallel welfare” whose dimensions are larger than those of thenational health system. Migrants’ role in feeding this segment of the labour market is attested bytheir percentage out of the <strong>to</strong>tal number of house-help workers registered by Inps (NationalInstitute for Social Security), that <strong>to</strong>uched 75% in 2002 and continued growing in the followingyears;- The employers’ tendency <strong>to</strong> address themselves <strong>to</strong> migrant workers <strong>to</strong> fill jobs alreadycharacterized by their presence. Together with the au<strong>to</strong>nomous and self-propulsive initiative ofmigrant workers – who enter the labour market largely using ethnicized channels – thistendency have contributed <strong>to</strong> stigmatize some kind of occupations, subsequently labelled as“migrants’ jobs”, without necessarily reflect real recruiting difficulties. This process contributes<strong>to</strong> reinforce the ethnicisation of the labour market (involving the risk of migrants’ occupationalsegregation and wage discrimination), but also <strong>to</strong> erect material and symbolic barriers whichobstruct the access <strong>to</strong> these jobs by the Italian workers still available. The most eloquent case isrepresented by persons assigned <strong>to</strong> cleaning services, the job profile that, in collectiveimagination, represents the example par excellence of a low social prestige job;- The growing number of self-employed migrants and entrepreneurs, a process which hascounterbalanced, in recent years, the progressive reduction of Italian independent workers. Atthe <strong>source</strong> of this phenomenon there are several different reasons, which may refer both <strong>to</strong> aparticular propensity, shown by some groups <strong>to</strong> self-employment and <strong>to</strong> the emerging newstructure of opportunity. The traditional spreading of self-employment, one-man businesses andmicro-firms in the Italian reality, the general drop in earning capacity involving many activities(which has diverted the interest of local entrepreneurs in them), the need for a generationturnover depending on the fact that many artisans and self-employed workers have become wellon in years, the growth of an outlet market formed by migrants themselves, the interest shownby some Italian consumers’ segments in “exotic” products, are all fac<strong>to</strong>rs that may haveencouraged the development of self-employment among migrants. Along with these fac<strong>to</strong>rs, weshould consider also some structural changes that are at the base of the emerging newmetropolitan economies, and of the resulting springing up of firms operating in the area of retailtrade, food (shops and restaurants), cleaning services, transports, house upkeep services, and soon, and in the second place, in the spreading of outsourcing logics, which have strengthened theneed <strong>to</strong> have available a network of small suppliers <strong>to</strong> which less profitable activities can be left.The self-employment phenomenon should be therefore interpreted also in the light of the labourmarket changes that have gradually made the boundaries of self-employment, subordinateemployment and unemployment more permeable and indefinite than in the past. Most firmsestablished by migrants are in fact one-man businesses that, <strong>to</strong> simplify, might in somecircumstances represent a sort of functional equivalent of the resort <strong>to</strong> atypical contracts. Theadaptability of first-generation migrants, but also their juridical vulnerability, may contribute <strong>to</strong>explain their peculiar “propensity” <strong>to</strong> set up businesses on their own, although the boundariesbetween their search for greater au<strong>to</strong>nomy and their subjection <strong>to</strong> the terms imposed bycus<strong>to</strong>mers can be however hardly traced out.<strong>Laura</strong> Zanfrini, Immigration in Italy, June 30, 2013. 12

There are no doubts that the massive inclusion of immigrant workforce is one of the majorelements characterizing the changes occurred in the last decades in the Italian labour market. Sincethe beginning of the 1990s, the number of both active and employed migrant workers have beencontinuously growing, conferring <strong>to</strong> the Italian labour market a more and more evident multi-ethniccomposition [see Table 4].Tab. 4 – Employed workers per economic activity sec<strong>to</strong>r, gender and geographical areas. Absolute values(thousands of units). Year 2012Comm.Total Agricult.TotalindustryBuildingindustryManuf.industryTertiaryindustryandtrade OthersItalians 20,564.7 734.5 5,59<strong>1.</strong>6 1,422.3 4169.3 14,238.6 4,232.6 10,006.0Italy Foreign. 2,334.0 114.6 770.4 33<strong>1.</strong>7 438.7 1449.0 418.4 1,030.6Total 22,898.7 849.1 6,362.0 1,754.0 4608.0 15,687.6 4,65<strong>1.</strong>0 11,036.6Italians 10,50<strong>1.</strong>7 273.8 3,360.5 69<strong>1.</strong>8 2668.7 6,867.4 2,09<strong>1.</strong>9 4,775.4North Foreign. 1,398.8 4<strong>1.</strong>2 54<strong>1.</strong>3 192.1 349.2 816.3 22<strong>1.</strong>4 594.9Total 11,900.6 315.0 3,90<strong>1.</strong>8 883.9 3017.9 7,683.7 2,313.3 5,370.4Italians 6,010.0 11<strong>1.</strong>2 1914.8 405.9 1508.8 3,984.0 1,160.2 2,824.0Foreign. 803.2 17.6 288.0 112.6 175.5 497.5 12<strong>1.</strong>1 376.4North-WestNorth-EastCanterTotal 6,813.2 128.8 2,202.8 518.5 1684.3 4,48<strong>1.</strong>5 1,28<strong>1.</strong>3 3,200.2Italians 4,49<strong>1.</strong>7 162.6 1,445.7 285.9 1159.9 2,883.4 93<strong>1.</strong>7 1,95<strong>1.</strong>7Foreign. 595.6 23.6 253.2 79.5 173.7 318.8 100.3 218.5Total 5,087.4 186.2 1,699,0 365.4 1333.5 3,202.2 1,032.0 2,170.2Italians 4,195.3 87.3 976.6 265.3 71<strong>1.</strong>4 3,13<strong>1.</strong>4 867.8 2,263.5Foreign. 622.5 28.0 170.4 10<strong>1.</strong>3 69.1 424.0 116.5 307.5Total 4,817.8 115.3 1,147.1 366.6 780.5 3,555.3 984.3 2,57<strong>1.</strong>0Italians 5,867.6 373.3 1,254.4 465.2 789.2 4,239.8 1,272.8 2,967.0Foreign. 312.7 45.3 58.7 38.2 20.5 208.7 80.5 128.1SouthTotal 6,180.3 418.7 1,313.1 503.4 809.7 4,448.5 1,353.3 3,095.1Source: Eurostat, 2012This growth hasn’t been broken up even during the present economic recession. The impac<strong>to</strong>f the crisis on immigration has proved <strong>to</strong> be more soft than in other countries, thus revealing thepeculiarities but also the weakness of the Italian labour market. Suffice <strong>to</strong> observe that, from 2005<strong>to</strong> 2012, employed migrants had almost doubled, and during the most acute phases of the crisis, theoverall employment has increased thanks solely <strong>to</strong> the foreign component. The additional foreignemployment that has been produced in these turbulent years amounts <strong>to</strong> over one million; i.e., avolume significant enough <strong>to</strong> force us <strong>to</strong> face the question of its consequences for the Italianworkforce. What is certain is that the substantial need for foreign labour expressed by Italianfamilies – for tasks decidedly unattractive <strong>to</strong> most of the native labour force – is not enough byitself <strong>to</strong> account for the extraordinary absorption capacity demonstrated by Italian economy.In order <strong>to</strong> explain migrants’ occupational performance we can suggest that the law qualitywhich is a distinctive mark of migration in Italy, has contributed “<strong>to</strong> protect” migrants. Actually,despite some initial signals <strong>to</strong>wards a qualitative labour improvement and up-grading, the crisisended up in a downward realignment of the employment structure, the deterioration of the overallemployment quality and a growth in the number of low-salaried jobs. <strong>By</strong> affecting mainly low-skilloccupations and more traditional sec<strong>to</strong>rs, the new jobs created exacerbated the traditional forms ofsegregation by gender and nationality. Actually, the distribution of employed workers byoccupation [Table 5] clearly demonstrates migrants’ segregation in the lowest levels of the jobs’hierarchy in all the years for which data are available.As data reported in Table 5 clearly demonstrate, employed foreigners’ distribution outlines anoverall picture characterized by substantial immobility. Certainly, at an individual level, there areseveral examples of upward mobility processes, which take shape as migra<strong>to</strong>ry seniority grows, andoutline the paths <strong>to</strong> emulate. However, at a general level, the needs expressed by firms and familiesseem <strong>to</strong> unavoidably reroute foreign labour <strong>to</strong>wards those segments which are already widely<strong>Laura</strong> Zanfrini, Immigration in Italy, June 30, 2013. 13

characterized by its presence and which, in some cases, satisfy the need <strong>to</strong> cover jobs deserted byItalian workers (such as it happens in the typical case of home-caretakers). In this situation, thedeskilling of well educated migrants has soon emerged as a distinctive trait of the Italianexperience, which has been confirmed by all the following inquiries: just <strong>to</strong> cite an example,according <strong>to</strong> the “Immigrant Citizens Survey” (May 2012), the percentage of employed immigrantswho believe that their main job does not require the level of skills or training that they have isdecidedly most significant in the two Italian <strong>to</strong>wns than in all the other European cities involved inthe research; furthermore, the percentage that have applied for recognition of qualifications, is inItaly dramatically lower than that recorded in the other countries.Tab. 5 – Employment by nationality and occupation (%), 2005-20102005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010Italians Foreign. Italians Foreign. Italians Foreign. Italians Foreign. Italians Foreign. Italians Foreign.Skilledworkers 35.5 9.2 37.8 9.3 38.8 9.9 38.4 8.3 37.5 7.2 36.8 7.1Clerical.Service/salesworkers 27.7 16.8 26.8 18.2 26.7 18.6 27.5 18.3 28.4 17.1 29.3 16.4Manualworkers 27.5 4<strong>1.</strong>1 26.5 43.0 26.0 43.0 25.7 4<strong>1.</strong>4 25.6 39.7 25.1 38.7Elementaryoccupations 8.2 32.9 7.8 29.5 7.4 28.5 7.2 32.0 7.3 35.9 7.6 37.7Armedforces <strong>1.</strong>2 0.1 <strong>1.</strong>2 0.0 <strong>1.</strong>2 0.0 <strong>1.</strong>1 0.0 <strong>1.</strong>2 0.0 <strong>1.</strong>3 0.0Total 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0Source: ISTAT, Indagine continua sulle forze di lavoro, 2005-2010.Conclusively, it should has be noted that the context in which the present discipline onimmigration <strong>to</strong>ok its first steps significantly changed. It is not by chance that some concerns aboutthe competition immigration might exert mostly <strong>to</strong>wards the weaker segments of local labour offer,which have long remained asleep due <strong>to</strong> a sort of exaltation of the idea of complementarity, havebegun <strong>to</strong> become manifest. As it already happened in other national experiences, the immigrationissue started <strong>to</strong> feed new conflicts and disclose the difficulty <strong>to</strong> find solutions in the position <strong>to</strong>combine different claims: altruistic claims, that is, those coming from large areas of civil society,which however sometimes seem <strong>to</strong> undervalue the consequences in the medium-long term of aninflow of a highly adaptable labour force such as the immigrant one; claims from the enterpriseworld, which is scarcely inclined <strong>to</strong> do without the benefits that resorting <strong>to</strong> immigrants’ labourindisputably brings about, particularly – or perhaps, chiefly – in a difficult economic period, whenthe need <strong>to</strong> improve work productivity by limiting costs becomes increasingly urgent; and finally,the claims of the social categories that might be more penalized by immigration, as their voice endsup by being represented by political and social “anti-immigrant” forces. The priority that till nowhas been given <strong>to</strong> the issue of entry selection should therefore give way <strong>to</strong> a reflection on the mostsuitable way <strong>to</strong> manage migrants’ impact on the labour market and <strong>to</strong> valorise their potentialthrough the recognition of their skills and competences, through the promotion of their role as adriving force for the internationalization of local and national economies, and, last but not least,through the adoption of strategies of human re<strong>source</strong> administration inspired by the perspective ofcross-cultural management. But, first of all, it is indispensable <strong>to</strong> rethink the idea of integration,which until <strong>to</strong>day has been strongly unbalanced <strong>to</strong>wards the purely working dimension, bypromoting a fuller and more equilibrate conception of migrants’ membership in the Italian society.Sources:ISMU Foundation, Italian Reports on Migrations, various years (www.ismu.org)<strong>Laura</strong> Zanfrini, Immigration in Italy, June 30, 2013. 14