HACCP Implementation in K-12 Schools - National Food Service ...

HACCP Implementation in K-12 Schools - National Food Service ...

HACCP Implementation in K-12 Schools - National Food Service ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>HACCP</strong> <strong>Implementation</strong><strong>in</strong>K-<strong>12</strong> <strong>Schools</strong><strong>National</strong> <strong>Food</strong> <strong>Service</strong> Management InstituteThe University of Mississippi#ET61-052005

AcknowledgmentsWRITTEN AND DEVELOPED BYCenter for Educational Research and EvaluationThe University of MississippiMax<strong>in</strong>e Harper, EdDKathleen Sullivan, PhDTiffany EdwardsStelenna LloydApril WilliamsDepartment of Family and Consumer SciencesThe University of MississippiDiane Tidwell, PhD, RD, LDKathy Knight, PhD, RD, LD<strong>National</strong> <strong>Food</strong> <strong>Service</strong> Management InstituteThe University of MississippiEnsley Howell, MS, RD, LDPROJECT COORDINATOREnsley Howell, A. Howell, MS, MS, RD, RD LDEXECUTIVE DIRECTORCharlotte B. Oakley, PhD, RD, FADA

Table of ContentsExecutive Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1Introduction/Purpose of Study. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4Review of Literature . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15Research Design . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16Figures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21Conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46Discussion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51Appendices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

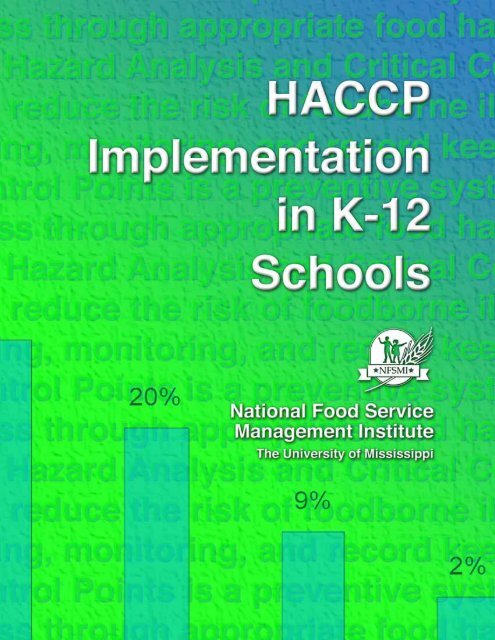

Executive SummaryIntroductionHazard Analysis and Critical Control Po<strong>in</strong>ts (<strong>HACCP</strong>) is a preventative system to reducethe risk of foodborne illness through appropriate food handl<strong>in</strong>g, monitor<strong>in</strong>g, and record keep<strong>in</strong>g.<strong>HACCP</strong> is now mandated for Child Nutrition Programs (CNP) effective July 1, 2005 due to agrow<strong>in</strong>g concern for food safety <strong>in</strong> schools. The <strong>National</strong> <strong>Food</strong> <strong>Service</strong> Management Institute(NFSMI) contracted with the Center for Educational Research and Evaluation (CERE) toconduct a survey of the extent of <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation <strong>in</strong> schools across the United States.A review of the literature concern<strong>in</strong>g <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation <strong>in</strong>dicated the rate ofimplementation among schools <strong>in</strong> the United States to be around 20% to 30%. Barriers to<strong>HACCP</strong> implementation with<strong>in</strong> schools <strong>in</strong>cluded lack of funds and/or time, as well as employeemotivation and confidence, as reported by Giampaoli et al. (2002a). In general, however, theliterature <strong>in</strong>dicated that school foodservice directors recognized the benefits of <strong>HACCP</strong>,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g a reduction <strong>in</strong> foodborne illness, compliance with health department regulations, andthe use of <strong>HACCP</strong> as <strong>in</strong>surance aga<strong>in</strong>st liability (Sneed and Henroid, 2003).Research DesignThe study was designed to determ<strong>in</strong>e the extent of <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation <strong>in</strong> schools;characteristics of the implementation process (why <strong>HACCP</strong> was implemented, source oftra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, length of time needed to implement, and status of implementation); benefits of <strong>HACCP</strong>implementation; and challenges associated with <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation. Frequencies andpercentages were used to report the overall results of each item on the survey, and the chi-squaretest was used to identify significant differences <strong>in</strong> responses <strong>in</strong> relation to region or schooldemographic variables.To study current <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation <strong>in</strong> schools <strong>in</strong> the United States, a pr<strong>in</strong>tedsurvey was adm<strong>in</strong>istered by mail to 2,200 school foodservice managers. The survey <strong>in</strong>cludedquestions about the school’s implementation of <strong>HACCP</strong> as well as questions about school andfoodservice manager demographics. Researchers surveyed 2-3% of foodservice managers <strong>in</strong>each United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) region and obta<strong>in</strong>ed a f<strong>in</strong>al response rateof approximately 18% overall. Although this rate was relatively low, comparison of responses bydate received, as well as comparison with non-respondents through phone <strong>in</strong>terviews, suggestedthat survey responses are not likely to have been substantially different with a higher responserate.Extent of <strong>HACCP</strong> <strong>Implementation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Schools</strong>The overwhelm<strong>in</strong>g majority of respondents (90%) reported hav<strong>in</strong>g standard or formalfood safety procedures <strong>in</strong> their schools. More than half of the respondents (65%) reported thattheir schools had begun implement<strong>in</strong>g <strong>HACCP</strong>. With<strong>in</strong> all regions therewas a higher rate of <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation than lack of <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation. There was nosignificant relationship between region and <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation.A significantly lower percentage of respondents from rural communities reportedimplement<strong>in</strong>g standard food safety procedures. <strong>Schools</strong> <strong>in</strong> major cities had a significantly higherpercentage of <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation (91%) than schools <strong>in</strong> other types of communities.However, a higher percentage of respondents were located <strong>in</strong> small towns, and only 67% of theserespondents had implemented <strong>HACCP</strong>.<strong>National</strong> <strong>Food</strong> <strong>Service</strong> Management Institute . . . . 1

Characteristics of the <strong>Implementation</strong> ProcessOf the schools that reported implement<strong>in</strong>g <strong>HACCP</strong>, 30% began the program more thanthree years ago, and 23% began the program between one and three years ago. Only 10% beganthe program less than one year ago. More than half (57%) of the schools that have notimplemented <strong>HACCP</strong> do not plan to beg<strong>in</strong> the program, while 43% do plan to beg<strong>in</strong>implement<strong>in</strong>g <strong>HACCP</strong>.In almost half of the respond<strong>in</strong>g schools (48%), the decision for implement<strong>in</strong>g <strong>HACCP</strong> isthe responsibility of the district foodservice director, and <strong>in</strong> 27% of the respond<strong>in</strong>g schools thedecision is the responsibility of the school foodservice manager. More than half of therespond<strong>in</strong>g schools (56%) reported that support from their foodservice director helped topromote <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation at their facility. Further, 41% of the respond<strong>in</strong>g schoolsreported that support from the school’s foodservice workers helped to promote <strong>HACCP</strong>implementation.The majority of the respond<strong>in</strong>g schools reported keep<strong>in</strong>g the follow<strong>in</strong>g types of recordsas part of their <strong>HACCP</strong> program: 1) refrigeration and freezer temperature logs and 2) record oftemperature to which food is cooked. Almost 50% of the schools keep records of preparationprocedures, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>ternal food temperature throughout preparation, as well as records ofthe temperature at which food is held on the serv<strong>in</strong>g l<strong>in</strong>e or <strong>in</strong> a hold<strong>in</strong>g cab<strong>in</strong>et. Between 22%and 37% of the schools keep other types of records as part of their <strong>HACCP</strong> program.The largest number of respondents (almost 50%) reported that their role <strong>in</strong> the <strong>HACCP</strong>program <strong>in</strong>cluded coach<strong>in</strong>g food service personnel on a daily basis. More than one-third reportedthat their role <strong>in</strong> the <strong>HACCP</strong> program <strong>in</strong>cluded monitor<strong>in</strong>g/complet<strong>in</strong>g <strong>HACCP</strong> paperwork, andmore than 20% of respondents reported that their role <strong>in</strong>cluded coord<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g <strong>HACCP</strong>implementation or tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g.Although 39% of the total number of respondents did not state whether their school ordistrict had a formal <strong>HACCP</strong> team, 38% reported that they did not have a formal <strong>HACCP</strong> team.Eleven percent reported hav<strong>in</strong>g a school <strong>HACCP</strong> team, and 13% reported hav<strong>in</strong>g a district<strong>HACCP</strong> team. The most common members of the <strong>HACCP</strong> team were reported to be the districtschool foodservice director, the school foodservice manager, and the school foodservice worker.With regard to the provision of <strong>HACCP</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the school, the highest percentage ofrespondents (23%) reported that district personnel provided tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. Next <strong>in</strong> order were the localHealth Department staff, the School Nutrition Association (SNA, formerly the American School<strong>Food</strong> <strong>Service</strong> Association), and the State Department of Education staff.Barriers to <strong>HACCP</strong> <strong>Implementation</strong>With regard to barriers affect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation, the lack of resources (time andpersonnel) and the burden of required documentation were the most commonly reported barriershav<strong>in</strong>g a significant effect on <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation. The proportion of respondents from theWestern region who reported that lack of available tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g had a significant effect on <strong>HACCP</strong>implementation was significantly higher than the comb<strong>in</strong>ed proportion of respondents from theall other regions who reported that lack of tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g was a major barrier. A significantly higherproportion of respondents from the Western region also reported that high employee turnoverhad a moderate or significant effect on <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation. In the Midwest region, theproportion of respondents report<strong>in</strong>g that the burden of required documentation procedures had asignificant effect on <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation was significantly higher than the comb<strong>in</strong>edproportion of respondents from all other regions who reported that documentation procedureswere a significant barrier. In the Western region, the proportion of respondents report<strong>in</strong>g that the2 . . . . <strong>HACCP</strong> <strong>Implementation</strong> <strong>in</strong> K-<strong>12</strong> School

urden of required documentation procedures had no or m<strong>in</strong>imal effect on <strong>HACCP</strong>implementation was significantly higher than the comb<strong>in</strong>ed proportion of respondents from otherregions who reported that documentation was not a major barrier.Benefits of <strong>HACCP</strong> <strong>Implementation</strong>A majority of respondents (55%) reported that the benefits of <strong>HACCP</strong> <strong>in</strong>cluded the factthat employees were practic<strong>in</strong>g good hygiene. Almost half the respondents (48.5%) reported that<strong>HACCP</strong> promoted a rout<strong>in</strong>e clean<strong>in</strong>g and sanitation program. Slightly more than one-third of therespondents stated that the benefits of <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation <strong>in</strong>cluded a facility designed toensure that it can be kept clean and sanitary; awareness of <strong>HACCP</strong> as an organized, step-by-step,easy-to-use approach to food safety; specifications that require food safety measures; andvendors’ provid<strong>in</strong>g safe food when delivered. Almost 25% of respondents reported reducedliability as a benefit of <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation.Plans for Expand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>HACCP</strong> <strong>Implementation</strong>The largest number of respondents (46%) reported that their schools plan to implementpractices to support all seven <strong>HACCP</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciples. Less than 10% of the respondents plan toexpand <strong>HACCP</strong> to other sites or other programs.<strong>National</strong> <strong>Food</strong> <strong>Service</strong> Management Institute . . . . 3

IntroductionHazard Analysis and Critical Control Po<strong>in</strong>ts (<strong>HACCP</strong>) is a preventative system to reducethe risk of foodborne illness through appropriate food handl<strong>in</strong>g, monitor<strong>in</strong>g, and record keep<strong>in</strong>g.<strong>HACCP</strong> is now mandated for Child Nutrition Programs (CNP) effective July 1, 2005 due to agrow<strong>in</strong>g concern for food safety <strong>in</strong> schools. This concern for food safety <strong>in</strong> schools has<strong>in</strong>tensified primarily because children, especially very young children, are at a higher risk ofbecom<strong>in</strong>g seriously ill or dy<strong>in</strong>g from foodborne illnesses than adults and because large numbersof children would be impacted should foodborne illness occur <strong>in</strong> schools.Purpose of StudyThe purpose of this study was to determ<strong>in</strong>e the extent, challenges, and benefits of<strong>HACCP</strong> implementation <strong>in</strong> K-<strong>12</strong> schools. F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs from this study can be used by the <strong>National</strong><strong>Food</strong> <strong>Service</strong> Management Institute (NFSMI) to assist <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g <strong>HACCP</strong> and other foodsafety tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g materials and determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g how these tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g materials can best be presented toschool foodservice staff.Review of LiteratureFor this research, a review of literature perta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g to <strong>HACCP</strong> <strong>Implementation</strong> <strong>in</strong> schoolswas provided by Diane Tidwell, PhD, RD, LD, and Kathy Knight, PhD, RD, LD, from theDepartment of Family and Consumer Sciences at The University of Mississippi.IntroductionThe Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Po<strong>in</strong>t (<strong>HACCP</strong>) system is a prevention-basedfood safety program. The <strong>National</strong> Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for <strong>Food</strong>s(1998) def<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>HACCP</strong> as “a systematic approach to the identification, evaluation, and control offood safety hazards.” Bryan (1999) stated, “<strong>HACCP</strong> is the art and science of food safety.” A<strong>HACCP</strong> plan is a written document that is based on the pr<strong>in</strong>ciples of <strong>HACCP</strong> and del<strong>in</strong>eates theprocedures that must be followed. A <strong>HACCP</strong> system is the result of the implementation of the<strong>HACCP</strong> plan.The objective of <strong>HACCP</strong> is to design systems that will prevent occurrences of potentialfood safety problems. Depend<strong>in</strong>g on the type of food operation, <strong>in</strong>herent risks are specificallyidentified <strong>in</strong> the production of foods or the preparation and serv<strong>in</strong>g of foods, and necessary stepsare determ<strong>in</strong>ed that will control the identified risks. The <strong>HACCP</strong> system replaces end producttest<strong>in</strong>g with a preventive system for produc<strong>in</strong>g safe food that has universal application to anytype of food operation.The <strong>HACCP</strong> system began <strong>in</strong> the 1960’s with the purpose of provid<strong>in</strong>g safe food forastronauts. The Pillsbury Company pioneered it with participation from the <strong>National</strong> Aeronauticand Space Adm<strong>in</strong>istration, the United States Air Force Space Laboratory Project Group, and theUnited States Army Natick Laboratories. Application of <strong>HACCP</strong> created food for the spaceprogram that approached 100% assurance aga<strong>in</strong>st contam<strong>in</strong>ation by bacterial and viralpathogens, tox<strong>in</strong>s, and physical or chemical hazards that could cause illness to astronauts. It hasbecome widely recognized worldwide as an effective system for food safety (Hudson, 2000).The <strong>HACCP</strong> system was first implemented by the food <strong>in</strong>dustry for the manufactur<strong>in</strong>gand process<strong>in</strong>g of foods that have a high risk for potential foodborne illnesses such as meat,poultry and milk, and canned foods if cann<strong>in</strong>g procedures were not followed correctly. Afteroutbreaks of botulism were reported <strong>in</strong> the early 1970’s from commercially canned foods and theisolation of Clostridium botul<strong>in</strong>um <strong>in</strong> canned mushrooms, the United States <strong>Food</strong> and DrugAdm<strong>in</strong>istration (FDA) <strong>in</strong>itiated a mandatory <strong>HACCP</strong> program for low-acid canned foods. More4 . . . . <strong>HACCP</strong> <strong>Implementation</strong> <strong>in</strong> K-<strong>12</strong> School

ecently, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has mandated the use of <strong>HACCP</strong>systems for all meat and poultry process<strong>in</strong>g plants, and the FDA has mandated the use of<strong>HACCP</strong> for seafoods, fresh fruits and vegetables, <strong>in</strong> addition to low-acid canned foods (Bryan,1999).A major reason for the emergence of <strong>HACCP</strong> was that emphasis on sanitary or health<strong>in</strong>spections and f<strong>in</strong>al product, or end product test<strong>in</strong>g was <strong>in</strong>effective <strong>in</strong> reduc<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>cidence offoodborne illness (Bryan, 1999). The traditional <strong>in</strong>spection process used by the USDA <strong>Food</strong>Safety and Inspection <strong>Service</strong> is a system designed to detect problems and unsafe conditions. Incontrast, the <strong>HACCP</strong> system is designed to prevent problems and unsafe conditions througheffective implementation of the pr<strong>in</strong>ciples of <strong>HACCP</strong>. The <strong>HACCP</strong> system has seven pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesthat were developed by the <strong>National</strong> Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for <strong>Food</strong>s,which was formed <strong>in</strong> 1988, and has many representatives and experts from federal and stateagencies, military, academia, consumer groups, and the food <strong>in</strong>dustry. The <strong>National</strong> AdvisoryCommittee on Microbiological Criteria for <strong>Food</strong>s (1998) adopted the <strong>HACCP</strong> system <strong>in</strong> 1992.<strong>HACCP</strong> Pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesThe <strong>HACCP</strong> system encompasses a systematic approach to the identification, evaluation,and control of food safety hazards based on the follow<strong>in</strong>g pr<strong>in</strong>ciples:Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 1. Conduct a hazard analysis.Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 2. Determ<strong>in</strong>e the critical control po<strong>in</strong>ts (CCPs).Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 3. Establish critical limits to control CCPs.Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 4. Establish procedures to monitor CCPs.Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 5. Establish corrective actions when a monitor<strong>in</strong>g procedureidentifies the violation of a critical limit.Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 6. Establish procedures to verify that the <strong>HACCP</strong> system isfunction<strong>in</strong>g and work<strong>in</strong>g properly.Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 7. Establish effective record keep<strong>in</strong>g that documents the <strong>HACCP</strong> system.<strong>National</strong> <strong>Food</strong> <strong>Service</strong> Management Institute . . . . 5

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 1: Conduct a hazard analysisPotential hazards can be divided <strong>in</strong>to three categories: biological (bacteria), chemical(clean<strong>in</strong>g agents, pesticides), and physical (environment, equipment). Biological hazards, orfoodborne bacteria, are usually the focus of <strong>HACCP</strong> systems due to the illness that can occur iffood is mishandled. More than 200 known diseases are transmitted through the <strong>in</strong>gestion of foodvia bacteria, viruses, parasites, and tox<strong>in</strong>s. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention(CDC) estimated that approximately 76 million illnesses, 325,000 hospitalizations, and 5,000deaths occur <strong>in</strong> the United States annually due to diseases caused by contam<strong>in</strong>ated food (Mead etal., 1999). Although CDC has reported a decrease <strong>in</strong> some bacterial foodborne illnesses, CDChas not revised its estimates of the overall <strong>in</strong>cidence of foodborne illness <strong>in</strong> the United States(GAO, 2002; CDC 2003; McCabe-Sellers and Beattie, 2004).When identify<strong>in</strong>g hazards, the likelihood that the hazard will occur and the severity if itdoes occur is determ<strong>in</strong>ed. Hazards that are of a low-risk nature and not likely to occur are notaddressed by <strong>HACCP</strong>. There are numerous issues to consider dur<strong>in</strong>g hazard analysis that <strong>in</strong>cludeall processes and handl<strong>in</strong>g practices related to food safety <strong>in</strong> the purchas<strong>in</strong>g, stor<strong>in</strong>g, prepreparation,cook<strong>in</strong>g, serv<strong>in</strong>g, and handl<strong>in</strong>g of leftovers. Flow diagrams that del<strong>in</strong>eate all thesteps <strong>in</strong> process<strong>in</strong>g and handl<strong>in</strong>g of food are usually used to identify hazards that could possiblyoccur <strong>in</strong> each step.After identify<strong>in</strong>g the hazards, specific procedures or preventive measures must bedeterm<strong>in</strong>ed for prevent<strong>in</strong>g the hazards. For example, if a hazard analysis were conducted for thepreparation of hamburgers from frozen beef patties, pathogenic bacteria <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>com<strong>in</strong>g rawmeat would be identified as a potential hazard. Cook<strong>in</strong>g the meat to an appropriate temperaturethat would kill the bacteria would be the preventive measure.Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 2: Determ<strong>in</strong>e the critical control po<strong>in</strong>ts (CCPs)A CCP is a step where a control measure can be applied and is essential to prevent orelim<strong>in</strong>ate a food safety hazard, or reduce it to an acceptable level. Any step or procedure wherebiological, chemical, or physical factors could cause a food safety problem and can be controlledis a CCP. Us<strong>in</strong>g CCP flow diagrams or CCP decision trees is useful <strong>in</strong> identify<strong>in</strong>g if a step orprocedure is a CCP. A CCP decision tree is a sequence of questions that determ<strong>in</strong>es if a controlpo<strong>in</strong>t is critical or not critical (<strong>National</strong> Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for<strong>Food</strong>s, 1998). There are many control po<strong>in</strong>ts <strong>in</strong> food preparation but few are actually CCPs.Steps or procedures that do not impact food safety are not <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the <strong>HACCP</strong> plan.Different facilities prepar<strong>in</strong>g the same foods can differ <strong>in</strong> the risk of hazards and CCPs due todifferent equipment, facility layout, or the use of different processes (Hudson, 2000).A CCP for the preparation of hamburgers from frozen beef patties that may havepathogenic bacteria <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>com<strong>in</strong>g raw meat would be the f<strong>in</strong>al cook<strong>in</strong>g step before serv<strong>in</strong>g.This is the last opportunity <strong>in</strong> the food preparation system to kill the bacteria.Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 3: Establish critical limits to control CCPsA critical limit is the maximum and/or m<strong>in</strong>imum level that a biological, chemical, orphysical parameter must be controlled at a CCP to prevent, elim<strong>in</strong>ate, or reduce the food safetyhazard to an acceptable level (<strong>National</strong> Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for<strong>Food</strong>s, 1998). A critical limit or preventive measure criterion is established for each CCP.Critical limits are thought of as boundaries of safety for each CCP and may <strong>in</strong>clude temperature,time, pH, physical space, and may be derived from various sources. There are numerousregulatory standards and guidel<strong>in</strong>es available to determ<strong>in</strong>e critical limits, <strong>in</strong> addition to scientificliterature and consultation experts (Hudson, 2000).6 . . . . <strong>HACCP</strong> <strong>Implementation</strong> <strong>in</strong> K-<strong>12</strong> School

Us<strong>in</strong>g the above example, if a hazard analysis is conducted for the preparation ofhamburgers from frozen beef patties, pathogenic bacteria <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>com<strong>in</strong>g raw meat would beidentified as a potential hazard. Cook<strong>in</strong>g the meat to a temperature that would kill the bacteriawould be the preventive measure. The critical limit would be cook<strong>in</strong>g the meat to an <strong>in</strong>ternaltemperature of 160°F as recommended by the USDA <strong>Food</strong> Safety and Inspection <strong>Service</strong> (2002).Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 4: Establish procedures to monitor CCPsEstablish<strong>in</strong>g procedures to monitor CCPs is necessary to verify that the <strong>HACCP</strong> plan isbe<strong>in</strong>g followed. Monitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>volves planned sequences of observations or measurements thatdeterm<strong>in</strong>e if a CCP is under control. Monitor<strong>in</strong>g is essential to food safety management <strong>in</strong> that itfacilitates track<strong>in</strong>g of the foodservice operation. Monitor<strong>in</strong>g is used to determ<strong>in</strong>e when there isloss of control or deviation of a CCP, and it provides written documentation for use <strong>in</strong> <strong>HACCP</strong>verification (<strong>National</strong> Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for <strong>Food</strong>s, 1998).Us<strong>in</strong>g the example above, the visual observation of the cooked hamburger patties, andnot<strong>in</strong>g the time and end-po<strong>in</strong>t temperatures to verify that the correct cooked temperature hasbeen obta<strong>in</strong>ed are procedures that monitor CCPs. Record<strong>in</strong>g cook<strong>in</strong>g times and temperatures of asampl<strong>in</strong>g of the hamburger patties are examples of establish<strong>in</strong>g procedures to monitor CCPs.Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 5: Establish corrective actions when a monitor<strong>in</strong>g procedureidentifies the violation of a critical limit.When a monitor<strong>in</strong>g procedure identifies a deviation of an established critical limit,corrective actions are necessary. The violation of a critical limit has the potential of caus<strong>in</strong>g ahealth hazard. Criteria must be <strong>in</strong> place to correct the deviation and prevent foods that may behazardous from reach<strong>in</strong>g the consumer. The <strong>HACCP</strong> plan should specify the corrective action,who is responsible for implement<strong>in</strong>g the corrective action, and that a record of the action isma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed.When receiv<strong>in</strong>g frozen hamburger patties, the receiv<strong>in</strong>g procedures should <strong>in</strong>dicate thatfrozen products must be received as frozen. If there is evidence that the hamburger patties are notfrozen or are <strong>in</strong> a thaw<strong>in</strong>g state, the temperature should be checked and recorded. If the frozenfood is not at an acceptable temperature, it should be rejected.Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 6: Establish procedures to verify that the <strong>HACCP</strong> system isfunction<strong>in</strong>g and work<strong>in</strong>g properlyEstablish<strong>in</strong>g verification procedures that the <strong>HACCP</strong> system is function<strong>in</strong>g properly<strong>in</strong>cludes a variety of activities. Types of activities <strong>in</strong>clude establish<strong>in</strong>g appropriate verification<strong>in</strong>spection schedules, review of the <strong>HACCP</strong> plan, review of CCP records, review of deviationsand resolutions, visual <strong>in</strong>spections of operations to observe if CCPs are under control, randomsampl<strong>in</strong>g of foods and microbiological test<strong>in</strong>g, review of critical limits to verify that they areadequate to control hazards, review of all written records, validation of the <strong>HACCP</strong> plan<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g on-site review and verification of flow diagrams of CCPs, and review of modificationsof the <strong>HACCP</strong> plan. Verification reports should also <strong>in</strong>clude who is responsible foradm<strong>in</strong>ister<strong>in</strong>g and manag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>HACCP</strong>, and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and knowledge of <strong>in</strong>dividuals for monitor<strong>in</strong>gCCPs (Hudson, 2000).Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 7: Establish effective record keep<strong>in</strong>g that documents the <strong>HACCP</strong> systemThis pr<strong>in</strong>ciple requires the preparation and ma<strong>in</strong>tenance of a detailed written <strong>HACCP</strong>plan. The system used for record keep<strong>in</strong>g must be organized and extensive; however, as Hudson(2000) notes, “the simplest effective record keep<strong>in</strong>g system that lends itself well to <strong>in</strong>tegrationwith<strong>in</strong> the exist<strong>in</strong>g operation is best.” Traditional records such as receiv<strong>in</strong>g records, temperature<strong>National</strong> <strong>Food</strong> <strong>Service</strong> Management Institute . . . . 7

logs and charts, and written recipes with specific directions work well. The record keep<strong>in</strong>gsystem <strong>in</strong> an organization ultimately makes the <strong>HACCP</strong> system work.<strong>HACCP</strong> PrerequisitesPrerequisite programs such as current Good Manufactur<strong>in</strong>g Practices that <strong>in</strong>clude basicfood safety education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g of employees are an essential foundation for the developmentand implementation of every <strong>HACCP</strong> system. Prerequisite programs provide the basicenvironmental and operat<strong>in</strong>g conditions required for safe food (<strong>National</strong> Advisory Committee onMicrobiological Criteria for <strong>Food</strong>s, 1998). Examples of prerequisite programs <strong>in</strong>clude:1. The establishment’s facilities are located, constructed, and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed accord<strong>in</strong>g tosanitary design pr<strong>in</strong>ciples. Traffic control and the flow of food products should be suchthat cross-contam<strong>in</strong>ation of raw and cooked items is prevented.2. Facilities should assure that suppliers follow effective Good Manufactur<strong>in</strong>g Practices andfood safety pr<strong>in</strong>ciples.3. All equipment should be constructed and <strong>in</strong>stalled accord<strong>in</strong>g to sanitary design pr<strong>in</strong>ciples.Preventive ma<strong>in</strong>tenance and temperatures (if applicable) should be established anddocumented. Thermometers should be <strong>in</strong> all freezers and refrigerators, and <strong>in</strong> dry storage.Temperatures should be rout<strong>in</strong>ely recorded.4. All procedures for clean<strong>in</strong>g and sanitation of equipment and the facility should beestablished and documented.5. All employees and <strong>in</strong>dividuals enter<strong>in</strong>g the facilities should follow the requirements forpersonal hygiene.6. All employees should receive documented tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> personal hygiene and safety,clean<strong>in</strong>g and sanitation procedures, and their role <strong>in</strong> the <strong>HACCP</strong> system.7. Documented procedures must be <strong>in</strong> place for the proper use and storage of nonfood itemssuch as clean<strong>in</strong>g chemicals, pesticides, and any other chemicals.8. Proper receiv<strong>in</strong>g, stor<strong>in</strong>g, and label<strong>in</strong>g procedures must be documented and followed forall raw products and materials.9. Effective pest control programs should be documented and followed.10. Proper employee food and <strong>in</strong>gredient handl<strong>in</strong>g practices should be documented andfollowed.11. Recipes should be standardized and these recipes should be followed for foodpreparation.Prerequisite food safety procedures provide the foundation for <strong>HACCP</strong> systems, andtherefore, effective implementation of a <strong>HACCP</strong> system is dependent on <strong>HACCP</strong> prerequisites.There are many sources available for education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> food safety and sanitation. Hwanget al. (2001) reported 62% of Indiana school foodservice operations had a sanitation-tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gprogram for employees. The most common source of <strong>in</strong>formation for develop<strong>in</strong>g sanitationprograms was the foodservice operation itself, followed by local health departments andextension programs. Other sources <strong>in</strong>cluded the Indiana School <strong>Food</strong> <strong>Service</strong> Association,Indiana State Department of Education, School Nutrition Association, <strong>National</strong> RestaurantAssociation, widely available videotapes, and private companies.Application of <strong>HACCP</strong> to School <strong>Food</strong>serviceMore than 33 million meals are served daily to children <strong>in</strong> schools through the <strong>National</strong>School Lunch and School Breakfast programs adm<strong>in</strong>istered by the USDA <strong>Food</strong> and Nutrition<strong>Service</strong>. In 1997 and 1998, an estimated 1,609 <strong>in</strong>dividuals experienced foodborne illnessresult<strong>in</strong>g from food served <strong>in</strong> school meal programs (GAO, 2000). In 2002, the United StatesGeneral Account<strong>in</strong>g Office further discussed food safety <strong>in</strong> meals served <strong>in</strong> schools, and reportedthat current analysis shows an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> the number of school-related outbreaks. However, theextent to which these outbreaks were caused by school foodservice programs could not bedeterm<strong>in</strong>ed. GAO noted that another possible source of foodborne illness could be foods brought8 . . . . <strong>HACCP</strong> <strong>Implementation</strong> <strong>in</strong> K-<strong>12</strong> School

from home (GAO, 2002). Overall, the number of foodborne illnesses result<strong>in</strong>g from school foodservice is a relatively small number compared to the millions of meals served daily; however, itis preventable. The <strong>HACCP</strong> system offers a preventable approach to food safety.The <strong>HACCP</strong> system is relatively new to the foodservice arena <strong>in</strong> contrast to the foodprocess<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dustry, especially the meat and poultry <strong>in</strong>dustry. However, the <strong>HACCP</strong> system’suniversal emphasis on provid<strong>in</strong>g safe food can be applied to any type of food operation. TheFDA has recommended the implementation of <strong>HACCP</strong> <strong>in</strong> foodservice establishments because itis the most effective and efficient method of ensur<strong>in</strong>g that food products are safe (Hudson,2000). The School Nutrition Association (2003) stated <strong>in</strong> a position statement that the associationsupports the development and implementation of a systematic approach to food safety <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g<strong>HACCP</strong> <strong>in</strong>to school foodservice systems. The Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization ACT of2004 now mandates that, effective July 1, 2005, all districts will implement a food safetymanagement program based on <strong>HACCP</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciples.Several states have provided <strong>HACCP</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g to schools. The Wiscons<strong>in</strong> Department ofPublic Instruction through the Wiscons<strong>in</strong> School <strong>Food</strong> Safety Program offered <strong>HACCP</strong> classesto school foodservice staff dur<strong>in</strong>g summer workshops at several locations, and at statewideconferences to help managers and directors effectively implement <strong>HACCP</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciples <strong>in</strong> theirschools (Wiscons<strong>in</strong> Department of Public Instruction, 2003).The New York City’s school foodservice system serves more than 150,000,000 meals ayear at approximately 1,400 sites with 10,000 workers, and has <strong>in</strong>stituted a <strong>HACCP</strong> program.The Board of Education’s Office of School <strong>Food</strong> and Nutrition <strong>Service</strong>s for New York Cityformed a <strong>HACCP</strong> Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Team consist<strong>in</strong>g of ten <strong>in</strong>dividuals to provide oversight of<strong>HACCP</strong> implementation and serve as an extension of the tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g program. The <strong>HACCP</strong>Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Team members were given fairly extensive tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>HACCP</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciples and NewYork City’s specific <strong>HACCP</strong> plan for schools. Three areas were identified “as potentialbottlenecks <strong>in</strong> implementation of its <strong>HACCP</strong> program: the critical control po<strong>in</strong>t analysis,tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, and oversight of implementation” (Gill, 2000).The New York City’s school foodservice department simplified the analysis of CCPs bygroup<strong>in</strong>g similar processes together, for example us<strong>in</strong>g the same <strong>HACCP</strong> model for prepar<strong>in</strong>gprecooked, breaded fish fillets and precooked, breaded chicken cutlets as well as precooked,ground beef patties. Probably the biggest challenge of <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation was the tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gof 10,000 employees. This was accomplished by tak<strong>in</strong>g a two-tiered approach where one tier, orgroup, received extensive tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and the other group received specialized, or tailored, tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g.The third bottleneck was the oversight of <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation, which was achieved by theform<strong>in</strong>g of the <strong>HACCP</strong> Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Team. The primary objectives of the team were to visitkitchens, monitor <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation us<strong>in</strong>g checklists, and share results with managers,supervisors, and employees who work <strong>in</strong> the kitchens to re<strong>in</strong>force correct actions and correct<strong>in</strong>appropriate actions (Gill, 2000).The Val Verde Unified School District <strong>in</strong> Perris, California, <strong>in</strong>stituted a <strong>HACCP</strong>program. The School <strong>Food</strong>service Director, Michael Bazan, was reported as say<strong>in</strong>g “you don’twait until you have a problem-you prevent it” (Riell, 1997). <strong>HACCP</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g was be<strong>in</strong>g phased<strong>in</strong> gradually <strong>in</strong> the school district’s foodservice operation. One <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t was the use of astrict dress code for foodservice employees. In addition to wear<strong>in</strong>g protective gloves, closed-toeshoes and appropriate clothes, jewelry is kept to “an absolute m<strong>in</strong>imum,” as well as nail polishand artificial f<strong>in</strong>gernails (Riell, 1997).<strong>National</strong> <strong>Food</strong> <strong>Service</strong> Management Institute . . . . 9

Another California school district that implemented a <strong>HACCP</strong> program was the LongBeach Unified School District’s Nutrition Center <strong>in</strong> Long Beach, California. It is a large schooldistrict with a large cook-chill facility that prepares and distributes 75,000 meals a day to 85district school sites. The food production center is located <strong>in</strong> a former warehouse. A $10 millionconversion of the warehouse <strong>in</strong>to a new food production center with efficient workflow spaceand equipment ensured the atta<strong>in</strong>ment of <strong>HACCP</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciples <strong>in</strong> all phases of the operation (Doty,2000).Research Investigat<strong>in</strong>g the Use of <strong>HACCP</strong> <strong>in</strong> School <strong>Food</strong>serviceYoun and Sneed (2003) conducted a study to determ<strong>in</strong>e implementation of food safetyprocedures and practices related to <strong>HACCP</strong> and <strong>HACCP</strong> prerequisites <strong>in</strong> school foodservice. Aquestionnaire was sent to a random national sample of 600 district school foodservice directorsand all 536 Iowa school foodservice directors, and 33 directors of school districts known to havecentralized foodservice systems. A response rate of 35.4% was obta<strong>in</strong>ed and 22% of directorsstated that they had implemented a comprehensive <strong>HACCP</strong> program. Factor analysis was usedfor identify<strong>in</strong>g underly<strong>in</strong>g factors for items related to <strong>HACCP</strong> procedures and practices such asmeasur<strong>in</strong>g and record<strong>in</strong>g end-po<strong>in</strong>t temperatures of all cooked foods, measur<strong>in</strong>g and record<strong>in</strong>gtemperatures of foods on serv<strong>in</strong>g l<strong>in</strong>es, and measur<strong>in</strong>g and record<strong>in</strong>g temperatures of milk uponreceiv<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>in</strong> the coolers. Significant differences (p

have a <strong>HACCP</strong> program <strong>in</strong> place, and many were unsure what <strong>HACCP</strong> was or how to apply it <strong>in</strong>their operations. While it appears that school foodservice managers believe that food safety isimportant, <strong>HACCP</strong> is confus<strong>in</strong>g to many foodservice employees. Although approximately twothirdsof school foodservice directors have food safety certification (Youn and Sneed, 2003),implementation of HAACP programs <strong>in</strong> school foodservices is still not widespread.Barriers to <strong>Implementation</strong> of <strong>HACCP</strong>The perception that <strong>HACCP</strong> is complicated, difficult, and time-consum<strong>in</strong>g may be just afew reasons for not implement<strong>in</strong>g <strong>HACCP</strong>. An organized and effective record-keep<strong>in</strong>g system isat the center of every good <strong>HACCP</strong> system. Norton (2003) stated that a good record-keep<strong>in</strong>gsystem is essential. An early barrier <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g a <strong>HACCP</strong> plan is writ<strong>in</strong>g out <strong>in</strong> specific detailthe procedures to follow for simple food-handl<strong>in</strong>g and preparation techniques. Youn and Sneed(2003) reported that many school foodservice directors did not have written procedures forthaw<strong>in</strong>g food, tak<strong>in</strong>g temperatures, stor<strong>in</strong>g food and chemicals, clean<strong>in</strong>g and sanitiz<strong>in</strong>g, andhandl<strong>in</strong>g leftovers.Norton (2003) listed common pitfalls that must be avoided by employees such as enter<strong>in</strong>gdata ahead of time, enter<strong>in</strong>g false data, fail<strong>in</strong>g to record process deviations or corrective actions,fail<strong>in</strong>g to record equipment calibrations, and fail<strong>in</strong>g to sign and date all records. Record keep<strong>in</strong>gis the key component for manag<strong>in</strong>g and validat<strong>in</strong>g a <strong>HACCP</strong> program. However, many managersand workers <strong>in</strong> the food <strong>in</strong>dustry are bogged down by the regulatory requirements and dislike allthe paperwork. Also, it was reported that food cha<strong>in</strong> operators were plagued by problemsregard<strong>in</strong>g the lack of uniformity of the requirements as well as <strong>in</strong>terpretation and enforcement by<strong>in</strong>spectors. Different health <strong>in</strong>spectors may <strong>in</strong>terpret <strong>HACCP</strong> specifications differentlydepend<strong>in</strong>g on their knowledge base of <strong>HACCP</strong> (Anonymous, 1999).Taylor and Taylor (2004) stated that research on barriers to <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation hasbeen limited <strong>in</strong> terms of both amount and depth. In a qualitative study, four professionals whoown and manage their own foodservice operations were questioned concern<strong>in</strong>g the difficulty ofHAACP implementation, the burden of <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation, the perceived necessity of<strong>HACCP</strong> implementation, and staff problems with <strong>HACCP</strong>. When they learned about <strong>HACCP</strong> forthe first time, each of the <strong>in</strong>terviewees found it confus<strong>in</strong>g and difficult to understand. One ownerstated that he tried to copy someone else’s <strong>HACCP</strong> plan, not realiz<strong>in</strong>g that each program had tobe <strong>in</strong>dividualized for each particular operation. Two of the owners stated that the books they readon <strong>HACCP</strong> had contradictory advice and were very “round about”. One of the ma<strong>in</strong> compla<strong>in</strong>tsfrom the <strong>in</strong>terviewees was that <strong>HACCP</strong> was a burden, especially for small bus<strong>in</strong>esses becausethey did not have the staff or the time to deal with the documentation required for the program.Other perceived burdens were time and additional money required to tra<strong>in</strong> employees.As far as the perceived necessity of <strong>HACCP</strong>, most of the bus<strong>in</strong>ess owners gave theimpression that they did not th<strong>in</strong>k that <strong>HACCP</strong> was necessary even though they could articulatethe benefits of the program. They felt that they were already produc<strong>in</strong>g safe food and viewed<strong>HACCP</strong> as “added documentation”. In terms of staff problems with <strong>HACCP</strong>, one of the ownersstressed how difficult it was to get staff <strong>in</strong>volved with <strong>HACCP</strong> and mentioned staff motivation ashis biggest problem with <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation. All the owners believed that without propertra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, the staff would cont<strong>in</strong>ue to see <strong>HACCP</strong> as unnecessary and just “more bureaucracy”(Taylor and Taylor, 2004).<strong>National</strong> <strong>Food</strong> <strong>Service</strong> Management Institute . . . . 11

These perceived barriers to <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation, while com<strong>in</strong>g from Taylor andTaylor's (2004) qualitative study, are echoed <strong>in</strong> the results from more quantitative methods.Speer and Kane (1990) conducted research with state food protection directors <strong>in</strong> 50 states. Theyfound that challenges to certify<strong>in</strong>g employees were time, limited funds, and the perceived burdenof certification. These directors also stated that managers did not appear to be motivated to putfood safety practices <strong>in</strong>to effect, and believed certification to be unnecessary <strong>in</strong> terms of ensur<strong>in</strong>gfood safety.In a study to develop and test an audit tool for assess<strong>in</strong>g employee food-handl<strong>in</strong>gpractices <strong>in</strong> school foodservice, Giampaoli et al. (2002b) exam<strong>in</strong>ed time and temperature abuse,employee hygiene, and cross-contam<strong>in</strong>ation. The audit resulted <strong>in</strong> the identification of areas ofnoncompliance with safe food-handl<strong>in</strong>g procedures. Time and temperature abuse appeared to bethe most problematic. In 10 of the 15 kitchens tested, employees were not observed tak<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>ternal temperatures of hot food at any time dur<strong>in</strong>g pre-preparation. Dur<strong>in</strong>g preparation andservice, the most frequently observed problem was the handl<strong>in</strong>g of food with bare hands.In a structured <strong>in</strong>terview survey of food bus<strong>in</strong>ess operators <strong>in</strong> Glasgow, Scotland, Ehiri etal. (1997) <strong>in</strong>terviewed 70 sample food operations. Forty-five (64%) of the operations werefoodservice establishments, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g hotels, restaurants, hospital and nurs<strong>in</strong>g home kitchens,and school foodservices. The rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g 25 (36%) were food manufactur<strong>in</strong>g or process<strong>in</strong>gbus<strong>in</strong>esses. A total of 1,052 persons were employed <strong>in</strong> these operations. All 70 food bus<strong>in</strong>essoperators were asked various questions to assess their awareness and op<strong>in</strong>ions about <strong>HACCP</strong>.More than half (59%) had not heard of <strong>HACCP</strong> prior to the study. However, after <strong>HACCP</strong> wasexpla<strong>in</strong>ed, 41% strongly agreed and 50% agreed that <strong>HACCP</strong> was more effective than what theywere currently do<strong>in</strong>g to secure food hygiene. There was general consensus that <strong>HACCP</strong> hadgood potential to offer a good defense of due diligence with regard to an offence under the law.When asked whether <strong>HACCP</strong> would be expensive to develop and implement, the op<strong>in</strong>ions variedgreatly. N<strong>in</strong>eteen percent strongly disagreed and 37% disagreed that it would be expensive.However, 10% strongly agreed and 14% agreed that it would be expensive to develop andimplement a <strong>HACCP</strong> program. The largest perceived barrier to <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation wastime. When asked if <strong>HACCP</strong> would be a time consum<strong>in</strong>g strategy, 21% strongly agreed and 37%agreed.An <strong>in</strong>dependent survey on the implementation of <strong>HACCP</strong> <strong>in</strong> Ireland (Research andEvaluative <strong>Service</strong>s of Ireland, 2001) questioned 710 food bus<strong>in</strong>esses to measure such factors asawareness of <strong>HACCP</strong>, efficiency of food safety management systems used by the bus<strong>in</strong>esses,and perceived barriers to <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation. Lack of understand<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>HACCP</strong> wasidentified as one of the ma<strong>in</strong> barriers to <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation; 46% reported that they didn’treally know what <strong>HACCP</strong> was while 14% said it was too complicated. Fifty-two percent of therespondents had not even heard of the term <strong>HACCP</strong> prior to the survey. Of those who had heardthe term, 5.6 % agreed that they did not really know what <strong>HACCP</strong> was and <strong>12</strong>% agreed that itwas too complicated. A high percentage agreed with the statement that expressed a need formore food safety checks by government authorities. A smaller number of respondents agreedwith the statements that food safety is not really a bus<strong>in</strong>ess priority and they saw no benefits tothe <strong>HACCP</strong> system. The researchers concluded that the ma<strong>in</strong> barrier to implement<strong>in</strong>g a <strong>HACCP</strong>system was lack of knowledge. Despite the high percentage of small bus<strong>in</strong>esses participat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>this study, the m<strong>in</strong>ority of respondents highlighted the barriers that are typically associated withsmall bus<strong>in</strong>esses. The researchers felt that this reflected the lack of understand<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>HACCP</strong> bythe bus<strong>in</strong>ess owners.<strong>12</strong> . . . . <strong>HACCP</strong> <strong>Implementation</strong> <strong>in</strong> K-<strong>12</strong> School

These f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs are consistent with the report of a World Health Organization (WHO)Consultation on strategies for implement<strong>in</strong>g <strong>HACCP</strong> <strong>in</strong> small or less developed bus<strong>in</strong>esses(World Health Organization, 1999). This report identified potential barriers to <strong>HACCP</strong>implementation that <strong>in</strong>cluded lack of government commitment, lack of customer and bus<strong>in</strong>essdemand, absence of legal requirements, f<strong>in</strong>ancial constra<strong>in</strong>ts, human resource constra<strong>in</strong>ts, lack ofknowledge and/or technical support, <strong>in</strong>adequate <strong>in</strong>frastructure and facilities, and <strong>in</strong>adequatecommunications.In the study by Giampaoli et al. (2002a), school foodservice directors <strong>in</strong>dicated that thelargest barriers to <strong>HACCP</strong> implantation for them were not time and money, differentiat<strong>in</strong>g themfrom the small food bus<strong>in</strong>ess owners. These directors reported that the biggest problem for themwas that their employees were nervous about tak<strong>in</strong>g the food safety exam. The second largestproblem was employees not feel<strong>in</strong>g comfortable with change. Both of these barriers to <strong>HACCP</strong>implementation seem to be more concerned with efficiency of tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g rather than time ormoney. The researchers concluded that improv<strong>in</strong>g employees’ confidence <strong>in</strong> their food safetyknowledge and their ability to make changes are two areas <strong>in</strong> which school foodservice directorsshould focus attention. They suggested that tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, supervision, and feedback are all strategiesthat might improve employee confidence <strong>in</strong> their food safety knowledge and ability to implement<strong>HACCP</strong> programs.Youn and Sneed (2002) developed a written questionnaire that measured tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g andperceived barriers to <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation. N<strong>in</strong>e statements related to potential barriers toimplement<strong>in</strong>g food safety practices were <strong>in</strong>cluded. Barrier statements were related to time,money, <strong>HACCP</strong> plan availability, employee motivation, and knowledge about food safetypractices, facility design, and hav<strong>in</strong>g a food safety specialist. Like Giampaoli et al. (2002a),Youn and Sneed (2002) also found that approximately two-thirds of the directors stated that theyheld food safety certification. Twenty-two percent of the school foodservice directors reportedthat they had implemented a <strong>HACCP</strong> program <strong>in</strong> their district.Regard<strong>in</strong>g barriers to follow<strong>in</strong>g food safety practices, two barrier factors were identified:employee barriers (6 items) and resource barriers (3 items). Employee tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g was rated as thegreatest <strong>in</strong>dividual barrier item. Twenty-two percent of the foodservice directors strongly agreedand 43% agreed that employees needed more tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g to improve food safety practices. Inaddition, hav<strong>in</strong>g an established <strong>HACCP</strong> plan, time and employee motivation were other reportedbarriers. Twenty percent strongly agreed and 34% agreed on the need for supervisors to havemore time to follow food safety practices and 48% either strongly agreed or agreed thatemployees needed more time to follow food safety. Seventeen percent strongly agreed and 37%agreed that employees should be more motivated to follow food safety practices. Money wasalso a perceived barrier <strong>in</strong> this study. Twenty-one percent of the directors strongly agreed and25% agreed that they needed more money to devote to food safety. The researchers suggestedthat school foodservice directors consider strengthen<strong>in</strong>g employee-tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g programs, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gfood safety certification for all employees. Also, s<strong>in</strong>ce time and money were resource barriers,school foodservice directors need to exam<strong>in</strong>e how resources are allocated <strong>in</strong> their districts andmay need to reallocate funds for food safety and <strong>HACCP</strong>. Another suggestion was to give one ortwo employees primary responsibility for <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation s<strong>in</strong>ce this reduces barriers toimprov<strong>in</strong>g food safety (Youn and Sneed, 2002). For small school districts, technical assistancefrom such groups as the USDA, state agencies responsible for child nutrition programs, or the<strong>National</strong> <strong>Food</strong> <strong>Service</strong> Management Institute could be useful.Worsfold and Griffith (2003) surveyed 100 foodservice employees <strong>in</strong> the UnitedK<strong>in</strong>gdom about their perceptions of hygiene tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and attitudes towards risk managementsystems and <strong>HACCP</strong>. At a later date, the workers attended a tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g course on food safety and<strong>HACCP</strong>, which helped the researchers observe the workers’ knowledge. The results <strong>in</strong>dicatedthat the understand<strong>in</strong>g of risk, hazards, and risk management was low, but the workers were nothostile to the idea of <strong>HACCP</strong>. Nearly 70% of the workers claimed that their bus<strong>in</strong>ess had risk<strong>National</strong> <strong>Food</strong> <strong>Service</strong> Management Institute . . . . 13

Even though barriers exist, most school foodservice directors have a positive attitudetoward <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation. In general, school foodservice directors realize the benefits of<strong>HACCP</strong>, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g reduction <strong>in</strong> foodborne illness, compliance with health departmentregulations, and hav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>HACCP</strong> as an <strong>in</strong>surance policy aga<strong>in</strong>st liability (Sneed and Henroid, Jr.,2003). Other benefits and advantages of <strong>HACCP</strong> cited by the World Health Organization (1999)<strong>in</strong>clude <strong>in</strong>creased awareness of basic hygiene, <strong>in</strong>creased confidence <strong>in</strong> the food supply, improvedquality of life with improved public health and reduced medical costs, <strong>in</strong>creased consumer andgovernment confidence, reduction <strong>in</strong> food production costs due to reduced food recalls andreduced food waste, and improved staff and management commitment to food safety. Theapplication of <strong>HACCP</strong> to all types of facilities that process, prepare, and/or serve food can br<strong>in</strong>ga focus to food safety that traditional food <strong>in</strong>spection methods have lacked.Research DesignTo study current <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation <strong>in</strong> schools <strong>in</strong> the United States, researchersused a pr<strong>in</strong>ted survey adm<strong>in</strong>istered by mail to school foodservice managers. The survey <strong>in</strong>cludedquestions about the school’s implementation of <strong>HACCP</strong> as well as questions about school andfoodservice manager demographics. (See Appendix C, p. 66.) Through the survey, researchersproposed to measure the extent and effects of <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation and sought to determ<strong>in</strong>ewhether significant differences existed <strong>in</strong> responses <strong>in</strong> relation to region or school demographicvariables (e.g., school size, location, number of meals served daily, type of operation [selfoperatedor operated by a management company], or type of food production [e.g., on-site,central, satellite/receiv<strong>in</strong>g, vended]). Frequencies and percentages were used to report the overallresults of each item on the survey, and the Pearson chi-square test was used to determ<strong>in</strong>e whetherthere was a significant difference <strong>in</strong> responses <strong>in</strong> relation to region or school demographicvariables.Research ObjectivesThis study was designed to determ<strong>in</strong>e:• the extent of <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation <strong>in</strong> schools• characteristics of the implementation process (why <strong>HACCP</strong> was implemented, sourceof tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, length of time needed to implement, and status of implementation)• benefits of <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation• challenges associated with <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation.Description of Survey InstrumentResearchers met with representatives from the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Food</strong> <strong>Service</strong> ManagementInstitute (NFSMI) and from the University of Mississippi’s Department of Family and ConsumerScience to develop a list of questions that exemplified the types of <strong>in</strong>formation that should bederived from this research.Researchers designed a draft survey <strong>in</strong>strument based on the questions listed above, thenobta<strong>in</strong>ed feedback from NFSMI and from the representatives of the Department of Family andConsumer Science. Follow<strong>in</strong>g revisions based on suggestions from these <strong>in</strong>dividuals, NFSMIsubmitted the draft survey <strong>in</strong>strument to the Education Information Advisory Committee (EIAC).Researchers revised the <strong>in</strong>strument based on recommendations from EIAC. This <strong>in</strong>strument wasthen used <strong>in</strong> a pilot study to determ<strong>in</strong>e whether there were any unclear items that needed to berevised prior to conduct<strong>in</strong>g the full survey.Researchers developed a sample of school foodservice managers to whom the researcherswould send a pilot survey, the results of which would be used <strong>in</strong> further ref<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the survey form.This sample was obta<strong>in</strong>ed from a list of foodservice directors provided by NFSMI. On January 5,2004, researchers sent a blanket email to approximately 100 foodservice directors ask<strong>in</strong>g for the16 . . . . <strong>HACCP</strong> <strong>Implementation</strong> <strong>in</strong> K-<strong>12</strong> School

names and addresses of two to four school foodservice managers who worked under theirsupervision. This email was sent aga<strong>in</strong> on January <strong>12</strong>, 2004. Researchers received contact<strong>in</strong>formation for 100 school foodservice managers and 30 school foodservice directors.Researchers mailed the pilot surveys on January 26-27, 2004. Seventeen surveys werereturned and exam<strong>in</strong>ed for feedback regard<strong>in</strong>g unclear items. Respondents provided nocomments suggest<strong>in</strong>g changes. The survey <strong>in</strong>strument was resubmitted to EIAC and receivedf<strong>in</strong>al approval on March 26, 2004.The f<strong>in</strong>al survey <strong>in</strong>strument consisted of four parts. The first part <strong>in</strong>cluded the follow<strong>in</strong>g13 items that dealt with the extent and characteristics of <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation <strong>in</strong> the school:1) Do you have standard or formal food safety procedures to follow <strong>in</strong> your school?2) Have you begun implement<strong>in</strong>g the food safety procedure known as <strong>HACCP</strong> <strong>in</strong> yourschool? If no, are you consider<strong>in</strong>g start<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>HACCP</strong> program <strong>in</strong> yourschool?3) How many employees do you supervise? How many employees have receivedformal tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>HACCP</strong>?4) Estimate the date when <strong>HACCP</strong> began to be implemented at your school.5) Which of the follow<strong>in</strong>g types of records are kept as part of the <strong>HACCP</strong> program atyour school?6) The decision for implement<strong>in</strong>g <strong>HACCP</strong> <strong>in</strong> your school is the responsibility ofwhom?7) What has helped to promote <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation at your facility?8) What are your school’s plans for cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g/expand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation?9) What is your role <strong>in</strong> the <strong>HACCP</strong> program <strong>in</strong> your school?10) Does your school or district have a formal <strong>HACCP</strong> team? If yes, who serves on it?11) Who provides <strong>HACCP</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g for your school?<strong>12</strong>) Where has corrective action been taken <strong>in</strong> your facility?13) What have been the benefits of <strong>HACCP</strong> implementation at your facility?The second part of the survey asked respondents to rate each of 17 <strong>HACCP</strong> practicesaccord<strong>in</strong>g to whether the practice: 1) was currently <strong>in</strong> place at their school, 2) had been <strong>in</strong> place<strong>in</strong> the past but had been discont<strong>in</strong>ued, or 3) had never been <strong>in</strong> place at their school. The 17practices correlated with the seven <strong>HACCP</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciples.The third part of the survey asked respondents to rate the follow<strong>in</strong>g possible barriers to<strong>HACCP</strong> implementation <strong>in</strong> terms of their effect on their school’s food safety program, us<strong>in</strong>g thescale of: 1 = No or m<strong>in</strong>imal effect, 2) Moderate effect, 3) Significant effect.1) Lack of familiarity with <strong>HACCP</strong>2) Lack of fund<strong>in</strong>g3) Lack of resources <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g time and personnel4) Inadequate support from adm<strong>in</strong>istration5) Lack of available tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g6) High employee turnover7) Inadequate facilities8) Complexity of foodservice operation9) Burden of required documentation procedures10) Other (Please list)The fourth part of the survey <strong>in</strong>cluded the follow<strong>in</strong>g demographic <strong>in</strong>formation:1) What type(s) of school do you work <strong>in</strong>?2) How many students are enrolled <strong>in</strong> the school(s) that you supervise?3) How many lunches are served daily?4) Which meals do you serve?5) What type of food production is used by your school(s)?<strong>National</strong> <strong>Food</strong> <strong>Service</strong> Management Institute . . . . 17

6) What type foodservice management is used <strong>in</strong> your operation?7) How many years have you worked <strong>in</strong> school foodservice?8) How many years have you served <strong>in</strong> your current position?9) What is your highest level of education?10) What certifications do you hold?11) In what state do you work?<strong>12</strong>) In what type of community is your school located?Sample PopulationThe primary person responsible for ensur<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>HACCP</strong> is implemented <strong>in</strong> schools isthe district foodservice director, who works through the foodservice manager at each school.Because the school foodservice managers have the most direct knowledge of food safetyimplementation at their sites, they were the primary target audience for this survey of <strong>HACCP</strong>implementation. Researchers’ <strong>in</strong>itial sampl<strong>in</strong>g plan was based on a sample size of 2,200 schoolfoodservice site managers who would be selected at random from a list of all foodservicemanagers <strong>in</strong> the United States. This sample size was chosen because it was high enough to yieldan acceptable level of confidence (at least 95%) and sampl<strong>in</strong>g precision (sampl<strong>in</strong>g error less than5%) even with a relatively low return rate (as low as 16%).The orig<strong>in</strong>al plan for obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the sample population was to contact the responsible stateagencies <strong>in</strong> 50 states and the District of Columbia to request the names and addresses of allschool foodservice site managers. However, the <strong>in</strong>dividuals contacted did not have <strong>in</strong>formationat the school level. Therefore, the researchers obta<strong>in</strong>ed a list of school districts from the <strong>National</strong>Center for Education Statistics (NCES) website for 2001-2002. The subsequent plan was torandomly sort the districts and call foodservice directors <strong>in</strong> order of the randomized list andobta<strong>in</strong> names and addresses of foodservice managers who worked under them. This procedurewas to be followed until the desired sample of 2,200 foodservice managers was obta<strong>in</strong>ed. Onceaga<strong>in</strong>, this plan proved not to be feasible because of the length of time required to contact theappropriate <strong>in</strong>dividual and obta<strong>in</strong> the necessary <strong>in</strong>formation.Researchers concluded that the most feasible option was to obta<strong>in</strong> a list of all schoolswith<strong>in</strong> the United States and its territories from the NCES website. The researchers used arandom number generator to assign a number to each of these 88,223 schools, then sorted the listby random number and selected the 2,300 schools with the lowest random numbers. (Althoughonly 2,200 schools were needed for the sample, an additional 100 schools were drawn tocompensate for any unusable cases.) The researchers matched the selected schools with theirdistricts us<strong>in</strong>g the identify<strong>in</strong>g seven-digit number assigned to each district. Approximately 20“schools” that appeared to be special cases (i.e., that would not have food services <strong>in</strong> theirfacility, such as homebound programs and district offices) were deleted from the sample.Data CollectionThe f<strong>in</strong>al survey form was mailed to 2,200 school foodservice managers on April 21,2004. Names of foodservice managers were not available; therefore envelopes were addressed toschools with “<strong>Food</strong>service Manager” as the first l<strong>in</strong>e. Cover letters (Appendix B, p. 64)requested that the surveys be returned by April 30, 2004. Stamped, self-addressed envelopeswere <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the f<strong>in</strong>al survey mail<strong>in</strong>gs to foodservice managers. <strong>Food</strong>service managers wereasked to complete and return the survey by mail or by fax.NFSMI planners also stipulated that the researchers were to send a copy of the survey<strong>in</strong>strument to the foodservice director supervis<strong>in</strong>g each of the selected managers, along with aletter <strong>in</strong>form<strong>in</strong>g the supervisor that a manager from their district had been asked to participate <strong>in</strong>the survey. To comply with this request, the researchers sent the <strong>in</strong>strument and directors’ letter(Appendixes C and A, respectively, p. 66 and p.62) to 1,760 school foodservice directors <strong>in</strong> the18 . . . . <strong>HACCP</strong> <strong>Implementation</strong> <strong>in</strong> K-<strong>12</strong> School