Screen - Dark Matter Archives

Screen - Dark Matter Archives

Screen - Dark Matter Archives

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

INTERNATIONAL INDEX TO FILM PERIODICALS 1978An annual guide (0 film literatureessential for film students and librariansPubillfted _",,,aUy Wlce 11HZ IlliJ Indu OOV'eQ thearbON th"t .ppul1:d dunn, cad. year 10 mOR !tun 100of the wortd'J $D111ITlpOrU1n1 filmjoumab. TIle; 1918mI~ torIUlDfOftf IO,OOOf-lllnn.1M .0111'*. d.ooed 11110 thRe maUl n ltpin IC'nem.,.bJc.:u flnc:looUIJ soaoqy of filla. l»odUCtiM,....1(1)'. 1t$lbet..:s., rI(".)~ fUms I~ rum ...,_~ or..Tlllm moul danllJ the yetr); and btop3phy (:teton.~Ion.cl~,)bUies ",dude allthor's .......,; hUe or art..:k. periodicalalll>Oll~ Ikl:lllll of IIluI.."tH)ftS. fill1lOCf11pb!rs CIt..; and"daalption of the QOcIlcnlJ of the attockllIoe Irtd" IS complkd by to_ JS rdlll,rduVlS lnrouaflOUI the "'Orid, mo. o( whom arc mnn~n or theInlomulllW Fc

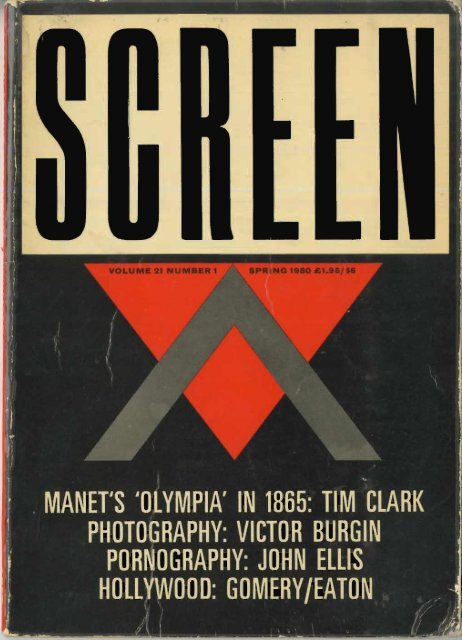

4FILM BOOKSPUBLISHED BY THE ARTS COUNCILOF GREAT BRITAINA PERSPECTIVE ON ENGLISH AVANT-GARDE FILM 84pp 37 illustrations £1.50 ISBN 0900229 54 3 An anthology of writings edited by Deke Dusinberre, covering a decade of film-making by English artists. 23 artists' statements and filmographies. FILM AS FILM formal experiment in film 1910-75 152pp 130 illustI1ltions £6.00 paperbound ISBN07287 0200 2 £8.00clothbound ISBN 07287 0201 0 A major hisroricaland critical survey offilms by artists. Articles on: abstract film, absolute film , avant·garde cinema, formal film, fururist film, kinetic theatre, Light-play, the non-objective film , notions of'avant-garde; 'other' avant-gardes, strucrural film, surrealist film. Statements, documentation and bio-filmographies from 100 international artist film-makers. ~~ft[[N----7I I15184381Spring 1980 Volume 21 Number 1published by the Society for Education in Film andTelevisionEditorialM 1 eKE A TON: Taste of the Past -on TelevisionCinema H istoryD O U G LA S GO MER y: Review - 'The Movie Brats'Preliminaries to a possibleTIM 0 THY J C L ARK:Treatment of ·Olympia' in 1865V leT 0 R BU R GIN:J 0 H N EL L I S: On pornographyPhotography. Phantasy. FunctIonSTANBRAKHAGE An American independent film-maker 46pp 63 illustrations £1.80 (£1.50 with exhibition) ISBN 09287 0218 5 Introduction to the work of one of America's most influential film-makers. Essays anda detailed chronology by Simon Field. An anthology ofBrakhage's own \\TItings, complete filmography. CORRECTION PLEASEor How We Got Into Pictures24pp 34 illustrations 90pThis booklet, containing 10 short observalionson film-language, isdesigned (0 complement Burch's 50 minute film 'Correction Please.'The film incorporates 10 complete films from the 'primitive' cinemaofl9OO-1906, and interweaves them with Burch'soWll wittynarrative, 're-constructed' according to evolving cinematic codes,DOCUMENTARIES ON THE ARTSlOOpp 110 illustl""dtions SOp ISBN 07287 0194 4Short background anicles and production delaiJs of75 films onpainting, sculprure, architecrure, music) pe.rfonnance) the-cltreetc, produced by the Arts Council ofGrear Britain.All enquiries should be addressed to the Film Office, ACGB,105 Piccadilly, London Wl. (Correction Plcase is also available fromMOMA, New York). February 19R0Arts CouncilOF GREAT HRITAI~E D iT O R: Mark Nash: ED I T O RI A.L OFF I CER: SusanHoneyford: ED ITO RI A LBO A R D: Ben Brewster, JohnCaughie, Elizabeth Cowie, Ian Connell, Phillip Drummond,Mi d;. Eaton, John Ellis, Stephen Heath, Claire Johnston,Mary Kelly, Annette Kuhn. Colin MacCabe, Steve Neale.Geoffrey Nowell-Smith. Paul Willemen, A D VE R T I SING MANAG E R: Ann Sachs D ES I G N : Julian Rothenstein. C O R R ES PO N 0 E Ne E should be addressed to: The Editor,S e RE E N, 29 Old Compton Street, London WI V 5PL.CON T R I B U T O R 5 should note that the Editorial Board cannotlake responsi bility fo r any manuscript submitted to <strong>Screen</strong>,Subscription rates : sec P ItO5 eR E E N is indexed in the International Index to FilmPeriodicals, and the International In dex to Televisio nPe ri odicals (FIAF). Photocopies and microfilm copies of<strong>Screen</strong> are available from University M icrofilms International18 Bedford RoW, London wet , and 300 North Zecb Road,Ann Arbour, Michigan 48106 USA.© 1980 The Society for Education in Film and Television,No artic le may b~ reproducl.!d or transmitted in any formor by any means, electronic or mechanical. including photocopy.recording, or any information stonlge and n:tricvalsystem without th e pl!rmission in writing of the Editor.ISSN 0036-9543.Printed in England by Vill iers Publications, London NW5.

6British Film InstituteSUMMER SCHOOL1980WHOlE CINEMAlEDITORIAL7, "j: ') ,~iUNIVERSITY OF KENT AT CANTERBURY JULY 25 - AUGUST 2Oet:aas and AppIicatioo Form from SumIl'l8l' School Seaetaty, BFI EOOcatioo. 81 DeanStreet, loodon W1 V6AA.2300 CELEBRITY HOME ADDRESSES Latest Edition' iI Verifiedcurrent home addresses oftop movi e, TV , sports, recording,VIP's and supe rstars available. Send $2.00($3 00 outside U.S.) for li stof names to:3utoclerk services Lincoln Savings Buildings 7060 Hollywood Boulevard Suite 1208H oll ywood Ca 90028I~I[USPECIAL OFFERBuy 4 back issues for theprice of 3Please state issues requiredand e ndose:UK £7.35Foreign £10,50 US $22.00(Postage and packing included)All issues from vol 15 no 3ava ilable, see inside back cover fordeta ils<strong>Screen</strong>'s work on visual representations has displaced traditionalcriticism of the artistic text as an object 'from' which aninherent meaning can be deciphered, to concentrate on theregimes of looking allowed to the spectator by texts and theirinstitutional plaCing. This displacement has been effected firstlyby semiotic analysis which insisted on the artistic text as theproduct of a social practice rather than a naturalised representationof reality. The extended consideration of realismwhich followed <strong>Screen</strong>'s discussion of semiotics introduced thecrucial area of extra-textual determination that has beencentral to recent debates in <strong>Screen</strong>. Secondly, the concern withpsychoanalysis and psychoanalytic concepts raised thequestion of the semiotic status and functioning of the imageitself _ but so far this has been addressed in <strong>Screen</strong> onlyin terms of the sequencing of images, of film as system andprocess.Consequently, a certain area of the ideology of the visualhas remained unexamined, including a whole range of positionsfro m notions of the image as an excess of signification, escapingnarrative constraints, to an affect fo unded in pre-linguisticprocesses or as an extra-discursive phenomenological essence.Perhaps it is in the field of artistic practices which are notspecifically cinematic that future issues of <strong>Screen</strong> can examinethis area productively for film criticism and also continue ourrevised project to engage a widet sphere of cultural work.While the articles by Clark, Burgin and Ellis in this issuedeal with radically different codes of representation and institutionaldiscourses. they are crucially related in a political

8 trajectory which questions received definitions of fine art,photography or pornogtaphy as discrete and self-referentialsystems. This is accomplished on the one hand by analysingthe histotical specificity of the critical discourses whichconsttuct these definitions, and on the other, by considetingthe specific relations of subjectivity that constitute a 'picture'in terms of the look it solicits and returns.Tim Clark's article is the first of several to extend <strong>Screen</strong>'sconcerns with visual representations into the area of artisticpractice traditionally designated as fine art, but which isreconsidered here in terms of a critical discourse whichexamines the conditions of the work's readability as pictorialtext. Clark analyses the ways rwo discourses (representationsof women and of aesthetic judgement in France in the 1860s)created an unreadable text in Manet's painting Olympia. Hemaintains that the hostile response of the critics of the Salonof 1865 turned fmally on the question of Olympia's ambiguoussexual identity (effected through the picture's uncertainty ofaddress, the transgression of the codes of drawing and conventionsof the nude). He also points to a changing recognitionof possible representations of the body which have subsequentlyincorporated this avant-garde text into mainstreamart history. Clark continues <strong>Screen</strong>'s discussion of the politicaleffectivity of artistic practice and the sociohistorical determinantsof their reading.Victor Burgin gives extended consideration to the questionof fetishism and atgues that the understanding it gives of theviewers' implication in the object of their vision enables us torecast the continuing debates about the social role of photographyand the possibilities of a progressive photographicpractice. In drawing on debates in the Soviet Union in the1920s he argues for combining the formalist approach (disruptingthe viewets' codes of reading - a position advocated byRodchenko) with an approach privileging progressive content,while at the same time recogniSing that struggles for meaningoccur within discutsive formations, at the interface of textand subject. He also argues against a modernist discourse(instanced in the criticism of Greenberg and Szarkowski) whichdefines categories of 'art' in terms of a medium (materialsubstrate) and calls for a consideration of representationalpractices within an 'intersemlotic and intertextual arena(q uoti ng Peter Wollen, 'Aesthetics and Photography', <strong>Screen</strong>vol 19 no 4).The issue of pornogtaphy is raised for the first time in<strong>Screen</strong> in an article by John Ellis. Questions such as whatconnects representations classed as 'pornographic', of whetherwe can say anything about their social effects are madeparticularly relevant in the context of the current debateinitiated by the Williams report. This Government commissionedstudy recommends the critetion of public acceptabilityin determining what materials should be on restricted Ot opensale. It differentiates between material media (writing/liveperformance/ film) for which diffetent criteria of potential harmcome into play. Whereas writing is not regarded as harmfuland therefore should not be subject to restrictions onavailability, film's 'realism' is regarded as sufficiently potentiallyharmful that they argue for the continuation of fUm censorship.Ellis initiates a study of the 'institution' of pornography andargues that a fuller understanding of the psychoanalyticmechanism of fetishism can help us understand existing formsof representation of sexuality in the struggle to displace currentforms with more progressive representations.MARY KELLYMARK N ASHROt. AND BAR THE 5 died in Paris on 26 March 1980 as a result of injuries sustained when he was knocked down by a van one month ear lier. He was 64. His work covered many topics central to <strong>Screen</strong>' s interestsand - from M~thologi e s to Elements of Semiology to S/Z bas been generally and decisively influential for our thinking, our projects. His last book, publisbed almost simultaneously with the accident that was to cost him his life, was an essay on thephotograph. La Ch ambre claire, in wbich certain of the ideas scattered in previous articles (notably 'The Tbird Meaning', the analysis of different levels of meaning in the response to someEisenstein stills) are taken up and developed in relation to thatconcem for the individual, the particular terms of the subjective, which had been so important to him in recent years (Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes, A Lover's Discourse). What we lose now with Bartbes. above all and quite simply, is a voice, a writing, an existence char constantly opened newquestions, proposed new forms of undem anding, changed thingsfor us.9

10RECENT BOOKS AND JOURNALS AVAILABLE FROM SEFTBooksD Bordwell and K ThompsonFilm as ArtM Chanan The Dream that Kick s : Prehistory andEarly Years of Cinema in Great Britain £12.50R DelmarB Edelma nG GenetteJ LotmanJ LotmanJoris IvensOwnership of the ImageNarrative DiscourseSemiotics of CinemaStructure of the Artistic textL Matejka and K Po merska (eds)Russian PoeticsReadings inA Mattelart· Multi national Corporations and theControl of CultureJ Mukarovsky Aes thetic Function, Norm andVal ue as s ocial FactM RaphaelProud hon, Ma rx , PicassoS Trukle Psychoanalytic Pol itics-Freud'sFrench RevolutionJ ournalsDiscourse/l (Riddles of the S phinx, Metzinterview etc )m / I nos 2.3Feminist Review nos 1,2.3October nos 5,6,7October nos 8.9Substance nos 20,21 ,22Ideology and Consciousness (Governing thePresent) no 6£8.25£2.45£1.95£8.95£2.00£3.50£3.50£14.95£2.00(8.25(6.95£3.00£1 .20£1 .50£3.40£1 .95(1 .95£1 .50$18.00$25.00$6.50$18.00$19.00$5.00$7.00$7.00$30.00$5.00$7.00$1 5.00$4 .00$4.00Pos tage and Packing 50p/ $1 .00 per item. Please makes cheq uespayable to SEFT, 20 Old Compton Street. Lo ndon WlMICK EATONTASTE OF THE PAST CINEMA HISTORY ON TELEVISION It should be of no little interest toreaders of <strong>Screen</strong> that in the past fewmonths the Hollywood cinema has beenthe subject of a wide-ranging process ofrehabilitation. A major Thames Televisionseries on the early days of Hollywood(Hollywood, the Pioneers) has recentlyfinished a 13 week run; the publishedspin-off from the series (same title.Collins, written by Kevin Brownlow, oneof the producer/ directors of the series)is in the hardback bestseller list and anexhibition at the Vic toria and AlbertMuseum on the 'Art of Hollywood', againpresented by Thames Television, has alsorecently finished. The research for theseries. conducted by Kevin Brownlow andhis colleagues. has taken several yearsand DC expense has been spared toacquire the best possible prints and totransfer them on to video at the speedsat which they should be shown, Giventhat the bulk of publications telati ng tothe 'history' of the cinema available onthe popular market are ill -researched.nostalgic fripperies merely perpetuatingtbe myt hs about the growth of theindustry. and given, also, that theknowledge of the silent cinema (not leastThis article is a revision and expansion of anearli er drafr written with Colin MacCabe.among those who teach film) is oftenextremely poor, this task is a laudableone. Brownlow and his collaborators wish[Q set the record straight. to reinstate thesilent cinema as an object of pop ularspeculation. However. perhaps it is timeto air a voice of dissent. to stand asidefrom the overwhelmingly uncriticalrecep tion of these projects by professionalcri tics . and to interrogate them. if onlybde£ly. from a position consonant withthe inquiry into foons of cinematicrepresenrarion articulated in the pages in<strong>Screen</strong> and elsewhere over the past fewyears.Almost by necessity this process ofrehabilitation is grounded on suchunde.fi ned and ultimately indefinablevalue5 as 'technique', 'artistry' and'quality'. The pioneers of the pte-soundcinema were not only achieving resultshenceforth unparalleled in the cinema.but the only reward they have receivedfor these ground-breaking tasks is tohave been forgo n en. 'History' becomes amatter of finding forgotten films,forgonen technicians. and inserting themback into their position of prominence .What emerges. then, is nothing less thana perpetuation of the old myths ofHollywood with a slight change ofemphasis and a somewhat larger [oster11

12 of leading characters. No longer is itpossible for us to dismiss the silentcinema. 'The magic of cinema' isenhanced. and our position as audiencewillingly implicated in the spectacles ofHollywood is confirmed. If anything wemay even feel a tinge of nostalgic regretthat those of us socialised to thef\inemalic experience through thehumdrum dramas of more recent yearsmay have missed Out on the more intensepleasures of our grandparents in thepicture palaces of yesteryear.The V and A exhibition poses slightlydifferent problems from those of thetelevision series - problems whichaccrue around the apparently contradictorynotions of authorship, and of film as a'collaborative art'. Rather than attemptingto introduce us to new possibilities ofcinematic spec(tac)ularit}', it took itsaudiences, assumed love of the cinemafor granted. co ncentrating ~on tried andtested memories of contemporary filmgoers. So there were rooms dedicated tothe movies that do good business inrevival houses - the 1930's musicals. thefilm noir - as well as all -time classicsof the screen - Intolerance, Gone with(he Wind and Citizen Kane, for example.In these rooms we were enjoined todiscover the talents of the art directors ofHollywood. In the pantheon of pleasurethe names of such 'forgotten figures ' asRichard Day, Anton Grot and Van NestPolglase can be added to those of Griffith ,Welles and Berkeley.Perhaps it is too much to expect the\....a1ls of the V&A or a peak-time televisionslot to be the sites of any historicalanalysis of how the cinema in Americamoved from being a minor fairgro undattraction to a vertically integrated,effective ly self-regulating major industrywith an annual investment of about oneand a half billion dollars, in a little lessthan twenty years. Perhaps it is also naive and idealistic to expect a television company to inaugurate any but the most superficial examination of the mechanics of visual pleasure and specularity in thecinema. The ramifications of this might befelt not only in the ratings. Obviously, thehistory of Hollywood as an industrycannOt be viewed in isolation from thewhole history of finance capital in theUSA. The investment in the possibility ofpleasure that the banks and big businessundertook in the early decades of thiscentury had directly determining effectson the fictional forms produced byHollywood. No simple relationship canof course exist between investments ofcapital and the pleasures of the audience.However, the way in which the Thamesseries continually skirts these issues doesnothing to make public knowledge of thedevelopment of Hollywood any more'historical' than it already is, and it isnot merely bad faith or academic gripingto insist on the necessity of the wri6ngof this history.Let us take a concre te example oferror by omission. In the third programmeof the series we were given an accoun[ ofa series of scandals in Hollywood which led to the eventual formation of the Motion PicnlCe Producers and Distributorsof America, the appointment of Will Haysas the 'moral watchdog' of the industry,and the establishment of a codecontrolling the coment of motion pic[Ures. The show presents this as a simple ideological decision: public outcryat the excesses of the stars' private livesand the films' treatment of sex andviolence results in the formation of aninstitution to curb these tendencies. Therealhy would, however. appear to bemuch more complicated. The majorstudios who formed the MPPDA welcomedthe opportunity for self-regulation, as thisprovided effective security of investmentand consolidation of control for thebanks who by that time had gained theeconomic whi p-hand in Hollywood, At thesame time, profiting from the economicchaos in Europe after the firsr world war.Hollywood was supplyi ng more and morefi lms for the world market. Theestablishment of the Hays Code ensuredthe industry's freedom from outsidecensorship by either state or federalgovernments. Similarly, the establishmentof the Code ensured that the studiosacquired a stranglehold over the outletsfor distribution throughout the States,The cinema becomes a much saferinvestment than, say, the press or radio.Perhaps even more important are [heeffects the Hays Code had on thedevelopment of fictional forms. This is,of course. easily determined withreference to content - American filmsfor [he European market continue to bemore sexual1y explicit. in terms of theexhibition of the female body, forexample. than the versions released onthe home market. Much more difficul t todetermine with any precision, and muchmore interesting, is the effect that, forexample, the 'control of sexualiry' exertedby the Code had on the organisation ofnarrative, We need only think of thetremendous weight given to marriage asan effective fo rm of closure in the classicHollywood fil m, and the narrativecomplexity generated by the repressionof the erotic, focus of much of theprogressive film theory generated inrecent years.It is in regard to the in vestment in anddevelopment of certain fictional forms.certain conventions of narrativeorganisation. that the series is lamentablydeficient_ In its incessant need to reclaimthe silent cinema as a popular an whichwas at least, if not more, technica lJyinventive, than its contemporarycounterpart. the most pertinent questionsare jettisoned in advance. \"'hat emergesis a fami li ar pattern : the 'natural' or'universal' language of the cinema liesdormant. presen-t from (he s tart in thetechnology, merely waiting to be draw nout by the appropriate pioneer. Thediscovery of this natural language,'Esperanto for the eyes' as Brownlowcalls it, becomes a process of trial anderror - the experiments of the pioneersare either sanctioned or not b)' theaudience:And if the experience took you out ofyourself and fltriched you, you talkedabout it to }'our friends, creating theprecious 'word of mouth' publicity thattile industry depended upon. You mayhave exaggerated a little. but the moviesSOon matched your hyperbole. Theytl'olved to meet the demands of theiraudience. (Preface, p 7)So one glaring omission of the seriesso far is the lack of any account of thedevelopment of the standard shotsequences to forms of narrative. Twobrief examples will suffice. The famoussequence from The Great Train Robbery(1903) in which the gang-leader fires hisgun directly out of screen is merelyaccompanied by the commentator'sassurance that this shot made theaudience feel more involved in the drama.So although 'primitive', Porter's workbecomes 'pure cinema'. What is howevermuch more in teresting about this 'famousfirst' is the fact that it has no place inthe narrative of rhe fil m at al l. Rapidlythe Hollywood cinema would developconventional forms such as the 30-degreerule which would ensure that thepossibiliry of breaking the spell ofcollusion betw'een audience and diegesiswould be severely curtailed. As NoelBurch makes cl ear in his discussion ofPorter (,Porrer, or Ambivalence', <strong>Screen</strong>Winter 1978/9 vol 19 no 4) rather thanthis shot being central in the developmentof the natural language of the cinema,it was in fact radically eccentric. So muchso tha t {he shot was delivered toexhibitors on a separate reel: 'it wasup to the exhibitors to decide whetherto stick it on at the beginning or end ofthe filin: Secondly, in the discussion ofGriffith (p 62) , Brownlow quotes from aBiograph advertisement :ltl cluded in the innovations which heintroduced and which are now generally13

14 lollowed by the most advanced producersare: the use 01 large close-up figures,distant views, the 'switchback', sus tainedsuspense , the 'lade-out' and restraint inexpressiotl. raising motion picture actingwhich has Won for it recognition as agenuine art.His comments on this weU~known piece ofhyperbole are as follows :Griffith was "ot responsible lor theclose-up or the lade-out nor would ithave made any difference il he hadbeetl. l1'hat counted was how such deviceswe re used. Griffith used them efficiently,sometimes brilliantly, and the ten dencyis to credit him with everything possiblein the cinema.We have already been told why Griffithshould have been the one to explOit thislanguage. Griffiths' days as a touring hamactor in melodrama gave him a knowledgeof audiences in the lower strata ofAmerican life. Karl Brown, Billy Bitzer'sassistant cameraman is quoted as fcHows(p 41):these same town-and-country yokelsbeca me the audietlCe upon which thenickelodeons depended lor their lile, liberty a"d the pursuit 01 happi"ess, Griffith k"ew th is. He also knew the psychology 01 the cheapest 01 cheap audietlccs as no New York producer evercould,Once again the complex determinationsoperating on the development of narrativecinema become naturalised, the questionof a simple transaction between audienceand producer. The cinema remains amonoJithic institution.In a recent harangue against semioticfilm criticism (,Cinematic Theology' _New Statesman, January 25, 1980 P 138)Brownlow expresses his desire to 'communicate to the Outside worJd', castigating <strong>Screen</strong> and others for their apparently fascistic disregard for rhenecessity of clear communication. Whenwe peer beneath the surface ofde-contexuaHsed fact and anecdote thatforms the veneer of his own particuJarprac tke it becomes clearer +hat what heso disparages is any attempt toundersrand..and to theorise the relationshipbetween the cbanging forms of film (both fictional and non-fictional) and changes in the technology and ins titutional forms(metbods of production and distribution) of the cinema. The unquestioning anirude to the forms of early cjnema is reproduced in the use of the forms of television in the Hollywood series. From the use ofthe authentica ting voice of the traditionalcommentator to the tantalising brevi ty ofthe film clips shown, and the use ofinterviews cu t into fragmen ts which onlyserve as a confirma tion of what we havealready seen and heard - every elementof the programme serves to confirm thenaturalness of the cinematic institutionand our love of it remains uncompromised.DOUGLAS GOMERYREVIEW: 'THE MOVIE BRATS' Mich:lel Pye, and Lynda Myles, The MovieBrats (New York: Holt, Rineha rt andWinston, 1979)Subtitled, 'How the film generation tookover Hollywood,' this volume" chroniclesand analyses the rise to power of FrancisCoppola, George Lucas, Brian DePalma,John Milius, Martin Scorsese, and StevenSpielberg. Tbese 'brats' created some ofHollywood's most spectacular box,officesuccesses during tbe past decade (forexample, The Godlather Parr 1 and II,Jaws, and Star Wa rs). The bulk of thisbook consists of standard 'biographical!critical' analyses of how these six (versusmany others who tried) were able togain a measure of power within tbecurrent Hollywood economic system.Little new material exists here (c 1978).The authors gleaned their data frommagazine articles in American Film, FilmComment, Esqu ire, and interviews. I shallnot critique their approach or sources forthis portion of the book; enough hasbeen done with such methods in <strong>Screen</strong>and elsewhere (compare Pye/ Myles'analysis of Jaws (pp 223-228) withStephen Heath's review in Frameworkno 4, Summer 1976).In the fi rsr quarter of their book Pye/Myles analyse how a new Holl ywoodeconomics replaced the classic studiosystem. in their own words 'how theplayground opened'. Pye/ Myles note thatthe US populace drifred away from thefilmgo ing habit after Worl d War II, andthen argue it took the six aforementioned'brats' to bring the masses back into thecinemas. Pye/Myles attempt to refute theconventional wisdom that television,principall y, and the 1948 US SupremeCourt Paramount Case and, secondarily,the McCarthyite Red Scare, caused theold Hollywood economic order to crumble.The two authors then argue tha t achanging social structure gave rise to theshift away from the movies. With theend of World War II, the principle focusof most US citizens turned to rais.ing afamil y and purchasing a single familydwelling. Pye/Myles assert thatThe young a"d educated, the mainaudience for film, were concen tra tingtheir attention on home and marriage.Television. cunningly. offered shows inwhich the star seemed to visit your home,addressed you confidently, and made theexperience of television a social actaround the hearth. More im portant.sitting in a darkened cinema did nothelp place you in a community, as goingto church did. It did not symbolize fa mily.It did not, like spectator sports, offer afo cIls to male solidarity away from Olefam ily. To families in suburbia. the cinemaserved no purpose. (p 18)Moreover the move to the su burbs tookthe new family un its fa r fro m downtownfirst-run cinemas. For Pye/Myles therelling statistics indicate that fil mattendance decl ined drastically from 194615

l13TIMOTHY J CLARKPRELIMINARIES TO A POSSIBLE TREATMENT OF 'OLYMPIA' IN 1865 zoc" < o'"MANET Olympia, Paris,MAN E TWA S N O T in the habit of hesitating before trying toput his l arge ~sc a l e works on public exhibition; he most often sentthem to the Salon the same year they were painted. But for reasonswe can only guess at. he kept tbe picture entitled Olympia in hisstudio for almost two years, perhaps repainted it, and submittedit to the Jury in 1865 (Figure 1). It was accepted for showing.initially hung in a good position, and was the subject of excitedpublic scrutiny and a great deal of writing in the daily newspapersand periodicals of the time. The 1860s were the beyday of theParisian press, and a review of the Salon was established as anecessary feature of almosr any journal; so that even a magazinecaJIed La Mode de Paris. which was little more than a set of coversfor fold-out dressmaking patterns, carried two long letters fromDumas the Younger in its May and June issues, entitled 'A Proposdu Sa lon. Alexandre Dumas a Edmond About'. The title - EdmondAbout was art critic of the Petit Journal - immediately suggeststhe degree of intertextuality involved . The 80·odd pieces of writingon the Salon in 1865, and the 60 or so which chose to mentionManer. were thoroughly aware of themselves as members of afamily, jibing at each other's preferences, borrOWing each other's[Urns of phrase, struggling for room (for 'originality') in a mono.tonous and consrricting discourse.~"

20BERTALL Caricature ofOlympia, L'lllustration,3 June 1865LIo IIIU.U, '11 cbll, 011 I. cbnbIlJUlI".......IJ....,II,• •n"-',n In" ........ 11 .. I .. n .. dl..ltl•."n,.• I\C, rI,.", r,o.,n . '''I,,,,l,. ~II.II. • ' jjl".a;.. ue'·n . ~ I< ~ " 1')01, I"~' L,· .,,,,,, . 1l'" ,"~.I.. hnl,fllp.!. I, t'h."""lI n~. I",1"''"''Ilict "'n' do.l ,.plt-r. )I . ~1.n "l. d _ """ , 101111,., I,on< ric I'Cxp

222 C MacCabe, 'TheDiscursive andthe Ideological inFilm', <strong>Screen</strong> vol19 no 4, p 36,3 P Willemen. 'Noteson Subjectivity On Reading 'SubjectiyityUnderSeige'. <strong>Screen</strong>vol 19 no I, p 55 .instead is to sketch the necessary components of such a study,to raise some theoretical questions which relate to <strong>Screen</strong>'s recentconcerns, and to give, in conclusion. a rather fuller account of theways in which this exercise might providea materialist reading !specifying/ articulations within the [picture}on determinate grounds. 2ITThere has been an impatience lately in the pages of <strong>Screen</strong> withthe idea tbat texts construct spectators, and an awareness thatfilms are read unpredictably, they can be pulled into more orless any ideological space, they can be mobilised for diverse andeven contradictory projects. 3This is an impatience I share, and in particular find myself agreeingwith Willemen thatthe activity of the text must be thought in terms of which set ofdiscourses it encounters in any particular set of circumstances, andhow this encounter may restructure both the productivity of thetext and the discourses with which it combines to form an intertextualfield which is always in ideology, in history. Some textscan be mdre or less recalcitrant if pulled into a particular field,while others can be fitted comfortably into it.It seems to me that Olympia in 1865 provides us with somethingclose to a limiting case of this recalcitrance; and one which,with the array of critical writing at our disposal. can be piecedout step by step. Recalcitrance is almost too weak a word, andinsignificance or unavailability might do better, for what we aredealing with in 1865 are the remains of various failures - a collectivefailure, minus Ravenel - to pull Olympia within the fieldof any of the discourses available. and restrucrure it in terms whichgave it a sense. There is a danger of exaggeration here, since thedisallowed and the unforgivable are in themselves necessary tropesof nineteenth century an critiosm : there ha d to be occupants ofsuch places in every Salon. But a close and comprehensive readingof the sixty texts of 1865 ought to enable us to distinguish betweena rhetoric of incomprehension. produced smoothly as part of theordinary discourse of criticism, and another rhetoric - a breakingor spoiling of the critical text's consistency - which is producedby something else. a real reca1citrance in the object of study. It isan open question whether what we are studying here is an instanceof subversive refusal of the established codes. or of a simple ineffectiveness;and it is an important question. given Olympia'scanonical (and deserved) status in the history of avant-garde art.IIIJ would like to know which set of discourses Olympia encounteredin 1865, and why the encounter was so unhappy. I think itis clear that two main discourses were in question: a discoursein which the relations and disjunctions of the terms WomanlNudelProstitute were obsessively rebearsed (which I shall call, clumsily,the discourse on Woman in the 1860s), and the complex but deeplyrepetitive discourse of aesthetic judgement in the Second Empire.These are immediately historical categories, of an elusive anddeveloping kind; rhey cannot be deduced from the critical textsalone, and it is precisely their absence from the writings onOlympia - their appearance there in spasmodic and unlikelyform - which concerns us most. So we have to establish, in thefamiliar manner of the historian, some picture of normal function·ing: the regular ways in which these two discourses worked, andtheir function in the historical circumstances of the 1860s.Olympia is a picture of a prostitute: various signs declare thatunequivocally. The fact was occasionally acknowledged in 1865:several critics called the woman courtisane, one described her as'some redhead from the quartier Breda' (the notorious headquartersof the profession). another referred to her as 'une manolo du basctage'. Ravenel tried to specify more precisely, calling her a 'girlof the night from Paul Niquet's' - in other words, a prostituteoperating right at the bottom end of the trade, in the all-night barru n by Niquet in Les Halles, doing business with a clientele ofmarket porters. butchers and chiffonniers. But by and large thiskind of recognition was avoided, and the sense that Olympia'swas a sexuality laid out for inspection and sale appeared in [hecritics' writings in a vocabulary of uncleanness. dirt, death.physical corruption and actual bodily harm. Now this is odd,because both the discourse on Woman in the 18605, and theestablished realm of arr, had normally no grear difficulty in includingand accepti ng the prostitute as one of their possible categories.There is even a sense, as Alain Corbin es rablishes in his study ofie discours prostilutionnel in the nineteenth century, in which theprostitute was necessary to the articulation of discourse onWoman in general:' She was maintained - anxiously and insistently- as a unity, which existed as the end-stop to a series ofdifferences which constituted the feminine. The great and absolutedifference was that between fille publique and fem me honnete:the twO terms were defined by their relation to each other. andtherefore it was necessary that the fille publique - or at least he rhaute bourgeoise variant. the courrisane - should have her repIe·senrations. The courtisane was a category in use in a well·estab·Iished and ordinary ideology: she articulated various (false) rela[ions between sexual identi[y. sexual power and social class. Of-----234 A Corbin, usFilles de noces.Misere sexuelle etprostitution aux1ge et 20e siedes,Paris 1978.

24 COULse at the same time she was declared to be almost unmentionable- at the furthest margin of the categorisable - but thatonly seemed to reaffirm her importance as a founding significationof Woman.So it was clearly not the mere fact - lhe palpable signs _ ofOlympia being a prostitute that produced the critics' verbalviolence. It was Some transgression of Ie discours prostitutionnelthat was at stake; or rather. since the characterisation of thecourtisane could nO[ be disentangled from tbe specification ofWoman in general in the 18605. it was some disturbance in thenormal relations between prostiwtion and fem ininity.When J introduced the notion of a discourse on Woman in the1860s, I included the nude as one of its terms. Certainly it deservesto take its place there, but the ,'ery word indicates tbe artificialityof the limits we have to inscribe - for description's sake _aro und our various 'discourses', The nude is indelibly a term of3rt and art criticism: the fact is that an criticism and sexual dis.COurse intersect at this point, and the one provides the other withcrucial representations, forms of knowledge, and standards ofdecorum. One could almost say that the nude is the mid·term ofthe series which goes from femme honnClc [0 fille publique: it isthe important form (the complex of established forms) in whicbsexuality is revea led and not·revealed, displayed and masked , madeout to be unproblematic. It is the frankness of tbe bourgeoisie:here, after aU, is wha't Woman looks like: and she can be known,in her nakedness, without too much danger of pollution. This tooOlympia called into question, or at least failed to confirm.One could put the matter schematically in this way. The criticsasked certain questions of Olympia in 1865. and did nOt get ananswer. One of them was: what sex is she, or has she? Has she asex at all? In other words, can we discover in the image of pre.ordained constellation of signifiers whkh keeps her sexuality inplace ? Further question: can Olympia be included within the dis.course on Woman/the nude/the prostitute? Can this particularbody, acknowledged as one for sale, be articulated as a term in anartistic tradition? Can it be made a modern example of the nude?Is there nOl a way in which the terms nude and fille pub/ique couldbe mapped on to each otber, and shown to belong together?There is no a priori reason wby nOt. (Though I think there may behistorical reasons why the mapping could not be done effectivelyin 1865: reasons to do with the special instabiHty of the term'prostitute' in the ] 860s, which was already producing. in thediscourse on \ 14 May1865, P ll; A JLorentz. DemitrJour de l'Exposi·tion de 1865,p B.25

26 _____6 See B Farwell,Manet and theNude, A Study inIconography in theSecond Empire.unpublished PhD,Unive rsiry ofCalifornia at LosAngeles 1973,pp 199-204.7 21 May 1865.I shall give two examples: one concerning Olympia's relation toTitian's so-called Venus of Urbina (Figure 5). and the otherRavenel's treatment of the picture's relation to the poetry ofBaudelaire. That Olympia is arranged in such a way as to invitecomparison with the Titian has become a commonplace of criticismin the twentieth century. and a simple charting of the stages ofManet's invention, in preparatory sketches for tbe work. is su{fivcient to show how deliberate was the reference back to the prototype.t;The reference was not obscure in tbe nineteenth century:the Titian painting was a hallowed and hackneyed example of thenude: when Maner had done an oil copy of it as a student, hewould have known he was learning the very alphabet of Art. Yetin the mass of commentary on Olympia in 1865, only twO criticstalked at all of this relation to Titian's Venus; only twice, in otherwords. was it allowed that Olympia existed 'with reference to'the great tradition of European painting. And the terms in whichit was allowed are enough to indicate why the other critics weresilent.'This Olympia: wrote Amedee Cantaloube in Le Grand Journal.the same paper that holds the bouquet in BertalJ's caricature,sort of female gorilla, grotesque in indiarubber surrounded byblack, apes on a bed, in a complete nudity, the horizontal attitude0/ the Venus 0/ Tit ian, the right arm rests on the body in the sameway, except fo r the hand which is flexed in a sort of shamelesscontraction. ~The other, a writer who called himself Pierror, in a fly -by-nightorgan called Les Tablettes de Pierrot, had this entry:a woman Ot1 a bed, or rather some form or other blown up like agrotesque in indiarubber; a sort oj monkey making fun of the posea1ld the movement of the arm of Titian' s Venus, with a handshamelessly fl exed.The duplication of phrases is too closely, surely, to be a matter ofchance, or even of dogged plagiarism. The two texts seem to meto be the wotk of the same hand - the same hack bashing out aswift paragraph in various places under various names. Whichmakes it one voice out of sixty, rather than two.In any case the point is this. For the most part, for almosteveryone, the reference back to tradition in Olympia was invisible.Or if jt could be seen, it could certainly not be said. And if, once,it could be spoken of, it was in these terms: Titian's arrangementof the nude was there, vestigially, but in the form of absolutetravesty, a kind of vicious aping wbich robbed the body of itsfem ininity, its humani ty, it very fleshiness, and put in its placeune forme quelconque, a rubber·covered gorilla flexing her dirtyhand above her crotch.I take Pierrot's entry, and the great silence of the other texts,as Hcense to say. quite crudely in the end, that the meaning contri..·ed in terms of Titian - on and against that privileged schemaof sex _ was no meaning . had no meaning , in 1865. (This is amatter which becomes fa miliar in the later history of the avantgarde: the moment at which negation and refutation becomessimply too complete; they erase what they are meant to negate,and therefore no negation takes place; they refute their prototypestoo effectively and the old dispositions are - sometimes literally painted our; they 'no longer apply'.)The example of Ravenel is more complex. J have already said thatRavenel's text is the only one in 1865 tbat cou ld possibly bedescribed as articulate. and somehow appropriate to the matter inhand. But it is an odd kind of articulacy. Ravenel's entry onOlym pia comes at rhe end of the eleventh long article in animmense series he published in L' Epoque, a paper of the far leftopposition.' It comes in the middle of an alphabetical listing ofpictures which he has so far let out of account, and not aUottedtheir proper place in the extended critical narrative of the fustten instalments of the Salon. The entry itself is a peculiar, bril·Iiant, inadvertent performance : a text which blurts out the obvious,blurts it out and passes on; ironic, staccato, as if aware of itsown uncertainty.~ 1. Manet - Olympia. The scapegoat 0/ the Sa lon, the vlcttmof Panslan lynch law. Each passer-by takes a srone and throws itin her fa ce. Olympia is a very cra zy piece of Spanis h madness.T ITIA."'l Venus of Urbino, Florence, Uf!izi8 7 June 1865.27

28 which is a thousand times better than the platitude and inertia ofPerhaps this alia podrida de toutes les CastiUes is not flatteringfor M. Manet, but all the same it is something. You do not29so many canvases on show in the Exhibition.Armed insurrection in the camp of the bourgeois: it is a glassmake an Olympia simply by wantingof iced water which each visitor gets full ill the face when he seesThjs is effective criticism, there is no doubt. But let me restrictthe BEAUTIFUL courtesan in full bloom.Painting of the school of Baudelaire, freely execu ted by a pu pilmyself to saying one thing about it. Ravenel - it is the achievementwhich first impreses us, I suppose - breaks the codes ofof Goya ; the vicious strangeness of the little faubourienne. womanof the night out of Paul Niguet, out of the mysteries of Pa ris andOlympia. He gers the picture right, and ties rhe picture down tothe nightmares of Edgar Poe. Her look has the sourness of someoneprematurely aged, her face the disturbing perfume of a fleurde mal; the body fatigued, corrupted ['corrum pu' also carries tbeBaudelaire and Goya: he is capable of discussing the image, halfplayfu lly and half in earnest, as deliberate provocation, designedto be anti-bourgeois: he can even give Olympia, for a moment, amean.ing "tainted', 'putrid'], but painted under a single transparentclass identity, and call her a petite faubourienne - a girl fromlight, with the shadows light and fine, tile bed and the pillowsare put down in a velvet modulated grey. Negress and flowe rsthe working-class suburbs - or a fille des nuits de Paul Niguel.insufficien t in execution, but with real harmony to t hem~ theshoulder and arm solidly established in a clean and pure light. Thecat arching its back makes the visitor laugl! and relax, it is whatsaves M. Mane t from a popular execution.De sa /o urrure tlOiTe [sic] et bruneSort un parIum 5i doux, qU'un soir}'en Ius embilume pour L'avoirCaresse [sic] une lois . .. rein qu·une.(From its black and brown fur / Comes a perfume sO sweet, thatone eve.ning / I was embalmed in it. from having / Caressed itonce . .. only once.)C'esl l'es prit lamilier du lieu;11 ;uge, il prtside, i/ inspireToutes chases d.:ms son empire;Peut-etre est-illee, est-it dieuJ(It is the familiar spirit of rhe place; / Ir judges. presides, inspires /AU things within its empire; / Is it perhaps a fairy. or a gad?)M. Mon et, instead of M. Astruc's verses would perJlaps havedone well to tilke as epigraph the quatrain devoted to Goya bythe most advanced painter oj Our epoch :GOYA-Cauchemar plein de chases incomwes Dc loetus qu'on fait cuire au milieu des sabbats , De vieilles au miroir et d'enfants toutes nues Pour tenter les demons ajustanr bien leurs bas. (Goya-- NighL-nare full of unknown rhings / Of foetuses cookedin the middle of wi tches' sabbarhs, / Of old women at the minorand children quite naked / To tempt demons who are making surerhei r stockings fit.)But getting tltings rigbt does not seem to enable Ravenel toaccede to meaning: it is almost as if brea king the codes makesmarcers worse from that point of vi ew: rhe more particu lar signifiers and signifieds are detected, the more perplexing and unstablethe totality of signs becomes. What, for instance, does the referenceto Baudelaire connote. for Ravenel? There are, as it were,four signs of that connotation in the text: the 'school of Baudelaire'leads on (1) to th e disturbing perfume of a fleur du "'

309 C MacCabe.<strong>Screen</strong>, op cit.p 36.ings does it open on to? It means nothing precise. nothing maintainable:it opens on to three phrases. 'fille des nuits de PaulNiquet, des mysteres de Paris et des caucbemars d'Edgar Poe',A working girl from the faubourgs/a woman from the farthestedges of fa prostitution populaire clandestine, soliciting the favoursof chiffonniers (one might reasonably ask: With a black maidbringing in a tribute of flowers? Looking like this, with theseaccessories, this decor, this imperious presentation of self?)/acharacter out of Eugene Sue 's melodramatic novel of the city'slower depths/a creature from Edgar Allen Poe. The shifts aremotivated clearly, but it is thoroughly unclear what the motivationis : the moves are too rapid and abrupt, they fail to confirmeach other's sense - or even to intimate some one thing, t ooelusive to be caught directly, but to which the various metaphorsof the text all tend.The identification of class is not a brake on meaning: it is thetrigger, once again, of a sequence of connotat.ions which do not addup, which fail to circle back on themselves, declaring their meaningevident and uniform. It may be that we are too eager, now, topoint to the ill usory quality of that circling back. that closureagainst· the 'free play of the signifier'. Illusion or not, it seemsto me the necessary ground on which meanings can be establishedand maintained : kept in being long enough, and endowed withenough co herence, for the ensuing work of dispersal and contradictionto be seen [Q matter - to have matter, in the text, towork against.VNashville articulates American politics and music in the space ofcinema, and that articulation can only be understood by mobilisinga heterogeneous set of knowledges (both cinematic and ideological)which will provide the specific analysis. Insofar as theknowledges we mobilise are, of necessity, heterogeneous, therecatl be no question that the reading produced is exhaustive.Between the alternatives of the formalist dream of the rea ding andthe voluntarist nightmare of my/our reading, both of whichexhaust the film' s significance, a materialist read ing specifiesarticulations within the film on determinate grounds.!)My questions about this passage would be: what determineswhich set of 'knowledges' are mobilised? Is there some means bywhich we can test which readings are, if not exhaustive, at leastappropriate? What is meant by 'determinate' in the last sentence?I suppose it will be obvious that my reading of Olympia will beproduced as a function of the analysis of its first readings: I donot claim that this gives it some kind of objectivity. or even someprivileged status 'within historical materialism'. But it providesthe reading with certain tests of appropriateness, or, to put itanother way. it presents the reading with a set of particular questions to answer, which have been produced as part of historical enquiry. (I do not object to the formula 'historian's practice' here. as long as we are free to debate whether there are some practices of knowledge with more articulated notions of evidence, t est ing and 'matching' than others.) My reading of Olympia would address the question: what is itin the image which produces, or helps produce, the critical silenceand uncertainty I have just described? What is it that induces thisinterminable displacement and conversion of meanings? I wouldlike. ideally. to give the answer to those questions an interleaved,almost a scholiastic form, tying my description back and back tothe terms of the critics' perplexity, and its blocked. unwilling insightinto its own causes. Clearly, the reading would hinge onOlympia's handling of sexuality. and its relation to the traditionof the nude. (It would also have to deal with its relation to a newand distinctive sub-set of that tradition: the burlesque and comicrefutation of the nude's conventions set in train by Courbet in the1850s. There is no doubt that the critics in 1'865 ~vanted Olympiato be part of that sub-set, whose terms they approximately understood.if only to abhor them; and there are ways in which thepicture does rela te to Courber's Realism. A painting of a prostitutein 1865 inevitably bore comparison with Courber's Demoisellesde la Seine or Venus Capitonnee; a comparison of subject-matter,obviously, but also of modes of address co the viewer, fo rms ofdisobedience to that 'p lacing of the spectator in a position ofimaginary knowledge' which was the nude's most delicate achievement.)I shall give some element .of the reading here.VIWe might approach the problem by asking. would it do to describethe disposition of signs in Olympia as producing some kind (variousforms) of ambiguity? The things I shall point out in the image mayseem at first sight nothing very different from this. And the wordwould provide us with a familiar critical comfort, since it seemsto legitimise the position of the a-historical 'interpreter' and allowthe open, endless procession of possible meanings to be the verynature of [he text, the way art (, li terature') works, as opposed tomere practical discourse. I do no t agree with that ethic of criticism,or the art practice it subtends. On the contrary. it seems to methat ambiguity is only functional in the text "...hen a certai n hierarchyof meanings is established and agree9 on, between text andreader - whether it be a hierarchy of exoteric and eso.reric, orcommon-sense and 'contrary', or narrative discourse and non31

3210 See B Farwell,op cit, p 233.narrative connotation. or whatever. There has to be a structure ofdominant and dominated meanings. within which ambiguity OCtursas a qua li fie r, a chorus. a texture of overtone and undertone arounda tone which the trained ear recognises or invents , To PUt itanother way, there bas to be. stabilised within the text. someprimary and partially systematic signified, in order that the playof the Signifier - the refusal of the signifi er to adhere completelyto that one set of signifieds - be construed as any kind of threat.It could be argued tbat Olympia's recalcitrance is different fromthis. The work of contradiction - to repeat and generalise thepoint made with reference to Titi an - might seem to be so completein this picture that the reader is left w ith no primary systemof signified s to refer to, as a test fo r deviations. Olympia could bedescr ibed as a tissue of loose ends, false starts. unfinishedsequences of s,ignification: none of them the ma in theme. nontaccompaniment exactly; neither systematic n Or floating serncs.The picture turnS, inevitably. on the signs of sexual identity. Iwant to argue that. for tbe critics of 1865 . sexual identity wasprecisely what Olympia did not possess. She failed to occupy aplace in the discourse on "" oman, and specifically she was neithera nude, nor a prostitute: by tbat I mean she was not a modifica.rion of the nude in ways which made it clear that what was beingshown was sexuality on the point of escaping from the constraintsof decorum - sexuality proffered and scandalous. There is noscandal in Olympia, in spite of the critics' effort to construct one.It was the odd coexistence of decorum and disgrace - the way inwhich neither set of qualities established its dominance ovet theother - which was the difficulty of the picture in 1865.For instance. since the structure is grossly obvious hete. thepicture's textual support. On the one hand. there is the title itself:classical apparently. and perceived by some critics as a tefetenceto a notorious courtisane of the Renaissance; but in 1865, takingits place in the normal repertoire of prostitution, pan of thetawdry, mock-classical lexicon of the rrade. 1 0 But that falseclassical does not subsist as the undisputed timbre of Olympia:in the Salon lil1ret. the reader was confronted by the fhte linesof 'explanatory' verse I have quoted already_ It is bad poetry, butcorrect. It is a performance in an established mode, Parnassian;restrained in diction', formal. euphemistic . Is th e reader (0 take itseriousl y? Is it to be Olympia. cynical pseudonym. or Taugustejeune fi1le en qui' - preposterous evasion- 'Ia flamme ve ille'?The disparity was obvious. I bave said. and the critics could dealwith it by simple. calm derision: they regula rly did.Other kinds of uncooperati\,eness were subtler and more complete,and the :critics could onl y rarely identify what it was thatrefused their various strategies. I shaH deal With three aspects of,he mltl

34a travesty of the norma l canons of 'Seallty', obvjously. and anattempt to make the nude, of all unlikely genres, exemplify theorders of social class. The Bather was meant to be read as abourgeoise, not a nude: she was intended to register as the unclothedopposite and opponent of male proletarian nakedness; andso Courbet displayed the painting in the Salon alongside anotherof roughly equal size, in which a pair of gnarled and exhaustedprofessional wrestlers went through thejr paces in the Hippodromedes Champs-ElySl!es.But The Bather broke the rules of the nude in other ways, whichwere hardly more subtle. hut perhaps more effective. It seemed tobe searching for ways to establish rhe nude in opposition to rhespectator, in active refusal of his sight. It did so grossly, clumsily,but not without some measure of success, so tbat the critic at thetime who called the woman 'this heap of matter, powerfully rendered,who turns her back with cynid sm on the spectator' had gotthe matter right. The pose and the scale and the movement of thefigure end up being a positive aggression, a resistance to visionin normal terms.There is no doubt that for Manet and his critics in 1865 theseprecedents were inescapabJe: as I have said already, the critleSwanted Ma·net to be a ReaBst in Courbet's terms, But Olympia , Iwo uld argue, takes up neither the arrangements by which thecanonical images of the nude establish access, nor Realism's knockaboutrefutations. What it contrives is stalemate, a kind of baulkedinvita tion, in which the spectator is given no estabHshed place forviewing and identification, nor offered the tokens of exclusion andresistance. This is done most potently, I suppose, by the woman'sgaze - the jet-black pupils, the slight asymmetry of the lids, thesmudged and broken corner of the mouth, the features halfadheringto the pla in ova l of the face. It is a gaze which givesno th ing away, as the reader attempts to interpret its blatancy : alook direct and yet guarded, poised very precisely between addressand resistance. So precisely, so deHberately, that it comes to beread as a production of the depicted person herself; there is aninevitable elision between the quaHties of preciSion and contri vance in the image and those quaHties as inhedng in the fictivesubject; it is her look, her action on us, her composure, her compositionof herself. But the gaze wou ld not function as it does- as the focus of other uncertainties - were it not aided andabetted by the picture's whole compOsition. Pre-eminent1y, if it isacccess that is in question, there is the strange indeterminate scaleof the image, neither in timate nor monumental: and there is thedisposition of the unclothed body in relation to the spectator'simaginary position: she is put at a certain , deliberate markedheight, on the two great mattresses and the flounced-up piJIows:in terms of the tradition, she is at a heigbt whicb is just too high,suggesting the stately, tbe body out of relation to the viewer'sbody; and yet not stately either, not looking down at us, nothieratic, not imperial: looking directly out and across, with asteadying, dead level interpellation. Tbe stalemate of 'placings' isimpeccable and typical, that is my point. If at this primary level_ the arrangemenr within the rectangle, so to speak, the laying. out in illusory depth - the spectator is offered neither access norexclusion, then the same applies, as I shall try to sbow, to thepicture's whole representation of the body.(b) Wbat the critics indicated by talk of 'incorrectness' in thedrawing of Olympia's body, and a wilder circuit of figures of dislocationand physical deformity, is, I would suggest, the way thebody is constructed in two inconsistent graphic modes. which onceagain are allowed to exist in too perfect and unresolved an equilibrium.One aspect of the drawing of Olympia's body is emphaticaUylinear: it was the aspect seized on by the critics, and given ametaphorical forc(>, in phrases like 'c ern~s de noir', ' dessin~e aucharbon', 'raies de drage' 'avec du charbon tout autour', 'Ie grosmatou noir . . air d~teint sur les contours de cette belle personne,apr~ s s'etre coule sur un ras de charbon'.ll (These arefigures which register also a reaction to Maner's elimination ofhalf-tones, and the abruptness of the shadows at the edges of hisforms: but this, of course, is an aspect of his drawing, taken inits widest sense.) The body is composed of smooth hard edges,deliberate intersections : the lines of the shou1ders, singular andsharp; the far nipp le breaking the contour of the arm with an artificial exactness; tbe edge of thigb and knee left flat and unmodulatedagainst the dark green and pink; the central hand markedout on a dark grey ground, 'impudiqument c ri sp~e' - in otherwords. as Pierrot implies. refusing to fade and elide with the sexbeneath, in the metaphoric way of Titian and Giorgione. Yet this isan incomplete account. 1he critics certainly conceived of Olympiaas toO definite - full of '!ignes heurtees qui brisent les ye ux'l~ but at the same time the image was accused of lacking definition.It was 'unfinished ', and drawing 'does not exist in it' ; it was'impossib le', elusive. 'informe'. Olympia was disarticulated, butshe was also inarticulate. I believe that this is a reaction on thecritics' part to other aspects of the drawing: the suppression ofdemarcations and definitions of parts: the indefinite contour ofOlympia's right breast, the faded bead of the nipple; the sliding,dislocated ]jne of the far fotearm as it crosses (tollches?) thebelly ; the elusive logic of the transition from breast to ribcage tostomach to hip to thigh. Tbere is a lack of atriculation here. It isnot unprecedented, this refusa1; and in a sense it tallies well with11 L de Laincel,C Echo deProvinces, 25 June1865, p 3.12 P Gill e, L' /nternational,1 June1865.35

36 the conventions of the nude. wbere the body is regularly offered asin 1865 it was not seen, or certainly not seen to do the things I37a flujd, infinite territory on which spectators are free to imposehave just described. And even if it is noticed - the connoisseur'stheir imaginary definitions. But the trouble here is the incompatibilityof this uncertainty and fu llness with the steely precisionof the edges which contain it. The body is. so to speak. tied downsmall reward for looking closely - it cannot. I would argue. beby drawing. held in place - by the hand. by the black tie aroundthe neck. by the brittle inscription of grey wherever flesh is to bedistinguished from flesh, or from the white of a piUow or thecolour of a cashmere shawl. The way in which this kind of drawingqualifies. or relates to. the other is unclear: it does not qualify it.because it does not relate : the two systems coexist: they describeaspects of the body. and point to aspects of that body's sexualidentity. but they do not bring those aspects together into somesingle economy of form.(c) The manipulation of· the signs of hair and hairlessness is adelicate matter for a painter of the nude. Peculiar matters ofdecorum are at stake, since hair let down is decent, but unequivocal:it is some kind of allowed disorder, inviting, unkempt,a sign of Woman's sexuality - a permissible sign, but qujte astrong one. Equally, hairlessness is a hallowed convention of thenude: ladies in paintings do not have hair in indecorous places,and that fact is one guarantee chat in the nude sexuality wiU bedisplayed but contained: nakedness in painting is nOt Jike nakednessin the world. There was no question of Olympia breaking therules entirely: pubic hair. for Manet as much as Cabanel andGiacomotti. was indicated by its abse nce. But Olympia offers usvarious substitutes. The hand itself. which insists so tangibly onwhat it hides; the trace of hair in the armpit; the grey shadowrunning up from the navel to the ribs: even, another kind ofelementary displacement. the frotbing grey. white and yellow fringeof the shawl. falling into the grey folds of pillow and sbeet - theone great accent in that open surface of different off· whites.There are these kinds of displacement. discreetly done; and thenthere is an odd and fastidious reversal of terms. Olympia's face isframed. mostly. by the brown of a Japanese screen. and theneutrality of that background is one of the things which makes tbeaddress and concision of the woman's face aU the sharper. But theneutrality is an illusion: to the right of Olympia's head there is ashock of auburn hair. just marked off enougb fr om the brown ofthe screen to be visible. with effort. Once it is seen, it changes thewhole disposition of head and shoulders: the flat. cut-out face issurrounded and rounded by the falling hair. the flower convertSfcom a plain silhouette into an object resting in the hair below ;the head is softened. given a more familiar kind of sexuality. Thequalification remains, however: once it is seen, this happens: butheld in focus. Because, once again, we are dealing with incompatibilitiespreCisely tuned: there are two faces, one produced by aruthless clarity of edge and a pungent cenainty of eyes and mouth.and the other less clearly demarcated. opening out into the surroundingspaces. Neither reading is suppressed by tbe other, norcan they be made into aspects of the same image, the sameimaginary shape. There is plenty of evidence of how difficult it wasto see , or keep seeing. this device. No critic mentioned it in 1865;the cartoonists eliminated it and seized, quite rightly, on the lackof loosened hair of Olympia's distinctive feature; even Gauguin,when he did a respectful copy of Olympia later. failed to includeit. The difficulty is vis ual: a matter of brown against brown. Butthat difficulty cannot be disentangled from th e other: the face andthe hair cannot be fitte d together because they do not obey theusual set of equations for sexual consistency, equations which tellus what bodies are like, how tbe world of bod ies is divided, intomale and fema le . resistant and yielding. closed and open, aggressiveand vulnerable, repressed and libidinous.Or we might want to make a more modest point. (Because ahidden feature is discovered, we sbould not necessarily treat ourselvesto a fea st of interpreta tion.) Whether it was noticed ('seenas') or not, the barely visible hair funC[ioned as a furth er interfer·ence in the spectator's fixing and appropriating of Olympia's gaze.Hair, pubic or otherwise, is a detail in Olympia, and should notbe promoted un duly. But the detail is significant. and it obe)'s thelarger rule I wish to indicate. The signs of sex are tbere in thepicture, in plenty, but drawn up in contradictory order ; one that isunfinished, or rather, more than one; orders interfering \\i th eachother. signs which indicate quite different places for Olympia inthe taxonomy of Woman ; and none of which she occupies.VIIA word on effectivt!ness, finally . t can see a way in which most ofwhat [ have said about Olympia could be reconciled with an enthusiasm,in <strong>Screen</strong> and else.where, for the 'dis-identificatory practices'of art, 'those practices wbich displace the agent from his orher position of subjective cenrrality', and , in general, with 'anemphasis on the body and the impossibility of its exhaustion inits representations'Y It \vould be phiHsrine not to take thatenthusiasm seriously, but there are aU kinds of nagging doubts- abo\'e all, about whether 'dis-identificatory practices' matter.The question is adumbrated by MacCabe when he writes:13 C MacCabe. 'OnDiscourse',Economy andSociety vol 8 no 3.pp 307. 308. 303.

38 It is through an emphasis on the body and the impossibility ofthis locale. In fact, as we have seen, the signs of social identity3914 C MacCabe.its exhaustion in its representations that one can understand theare as unstable as all the rest. Olympia has a maid, which seem~Economy and material basis with which the unconscious of a discursive forma [Q situate her somewhere on the social scale; but the maid is black,Society. op cit. tion disrupts the smooth functioning of the dominant ideologiesconvenient sign, stock property of any harlot's progress, derealised,P 303.and that this disruption is not simply the chance movement of thetelling us little or nothing of social class. She receives elaboratesignifier but the specific positioning of the body in the economic,bouquets of flowers , hut they are folded up in old newspaper; shepolitical and ideological practices,Uis faubourienne. Ravenel is right, in her face and her disabusedstare, but cQurtisane in her stately pose, her delicate shawl, herThis seems to address the quest jon which preoccupies me, andprecious slippers.which I would rephrase as follow s: Is there a differe nce - aLet me make what I am saying perfectly clear. Olympia refusesdifference with immediate. tactical implications - between anto signify - to be read according to the established codings for theallowed, arbitrary and harmless play of the signifier and a kind ofplay which contributes to a disruption of the smooth functioningnude, and take her place in the Imaginary. But if the picture wereto do anything more than that, it (she) would have to be given,of the dominant ideologies? If so - I am aware that I probablymuch more clearly, a place in another classed code - a place inexceed MacCabe's meaning at this point - artistic practice willhave to address itself to ·the specific positioning of the body inthe economic, political and ideological practices'; it cannot takeits own disruptions of the various signifying conventions as somehowrooted. autornaticaiJy, in the struggle to control and positionthe body in political and ideological terms; it has to articulate therelations between its own minor acts of disobedience and tbemajor struggles - the class struggle - which define the bodyand dismantle and renew its representations. Otherwise its actswi ll be insignificant - as Manet's were. I believe, in 1865.There is a danger of sounding a hectoring, or even a falselyoptimistic. note at this poim . Only a sense that the burden ofmodernity in the arts is this insignificance will save us from theabsurdity of feeling that we are not involved in Manet's failure;it might lead us to make a distinction between tbose works. likeOlympia. which succumb to modernity as a fate they do not welcome,and those bland battalions which embrace emptiness anddiscontinuity as their life's blood, their excuse their 'medium'.Olympia is not like these. its progeny; its failure to mean much isa sign of a certai n obdurate strength. It is adntirable in 1'865 for a .picture not to situate Woman in the space - the dominated andderealised space - of male fantasy. But this refusal - to soundagain the demanding note - is compatible with situating Womansomewhere else: making her part of a fully coded, public andfamiHar world, to which fantasy has entry only in its real, uncomfortable,dominating and dominated form. One could imagine adifferent picture of a prostitute, in which there would be depictedthe production of the sexual subject (the subject 'subjected', sub·ject to and subject of fantasy). Even. perhaps, the production ofthe sexual Subject in a particular class formation. But CO do that- CO put it crudely - Manet would have had to put a far lessequivocal stress on the signs of social identity in this body andthe code of classes. She would have to be given a place in theworJd which manufactures the Imaginary. and reproduces therelations of dominator/dominated, fantisiser/ fantasised.The picture would have to construct itself a position - it wo uldbe necessarily a complex and elliprical position. but it would haveto be readable somehow - within the actual conflict of imagesand ideologies surrounding the practice of prosotution in 1865.What that conflict consisted in was indicated, darkly, by thecritics' own fumbling for words that year - the shift betweenpetite faubourienne and courtisane. In other words, between theprostitute as proletarian, recognised as such and recognising herselfas such, and the other, 'normal' Second Empire situation: theendless exchange of social and sexual meanings, in which theprostitute is alternately - fantastically - recognised as proletarian,as absolutely abject, shameless, seller of her own flesh,and then, in a flash. misrecognised as dominator, as femme fa tale,as imaginary ru ler. (This dance of recognition and misrecognitionis one in which the prostitute shares, to a certain degree. But sheis always able - indeed liable - to flip back to the simple assess·mem of herself as JUSt another seller of an ordinary form of labourpower. She has to be constantly re-engaged in the dance of ideology.and made to coll ude again in her double role.)I think I should have to say that in the end Olympia lends itspeculiar confirmation to the latter structure, the dance of ideology.It erodes the term s in which the normal recognitions are enacted,but it leaves the structure itself intact. The prostitute is stilldouble. abject and dominant, equivocal. unfixed. To escape thatstructure what would be needed would be. exactly, another set ofterms - terms which would be discovered, doubtless. in the actof unsen li ng the old codes and conventions, but which would havethemselves to be settled, consistent, forming a f"inj shed sentence.

40~ It may be that 1 am asking for too much. Certainly 1 am askingfor the difficult. and equally certainly for something Manet didnot do. 1 am pointing to the fact that there are always othermeanings in any given social space - counter-meanings, alternativeorders of meaning. produced by the culture itself. in theclash of classes. ideologies and forms of contro l.~d 1 suppose Iam saying. ultimately. that any critique of the esrablis~d. domi~an[ systems 6f meaningW-iIl degenerate into a mere -refusal- tosignify unless it seeks to found its meanings - discover its contrarymeaning - not in some magic re-presentation, on the otherside of negation and refusal. but in signs which are already present,fighting for room _ meanings rooted in actual forms of life;repressed meanings. the meanings of the dominated.1How exactly that is to be done is another matter-. It will mostassuredly not be achieved in a single painting. (There is no hopefor 'Socialism in one Art-work', to borrow a phrase from ArtLanguage.) A clue to Manet's tactics in 1865. and their limitations.might come if we widened our focus for a moment and looked notjust at Olympia but its companion painting in the Salon, Jesusinsulted by the Soldiers (Figure 7) . This picture lVas also unpopularin 1865: some critics held it to be worse than Olympia. even; andmany agreed in seeing it as a deliberate caricature of religious art.But the operative word here is art: if the JeStls is paired with theOlympia. the effect of the pairing is to entrench both pictures inthe world of painting : they belong together only as contrastingartistic ca~g~ bizarre versions of the n~'!.nd tbealtarpie.ce~ T he contrasrWiili Courbet's procedure in 1853 isstriking: where the opposition of The Wrestlers" and The Batherundermined the possibility of instating either term in its normalplace in the canon. and reading it as pictures were meant to be~reaA. the conjunction oT'Oiympia and Jesus was meant to establishTitian (and perhaps even Baudelaire) all the more securely.Not that it did so. in fact; but this is the abiding paradox ofManer's art. In any case, Olympia and Jesus were far from beingManet's last word on the subject: the particular pairings and15 On The Wrestlers groupings of pictures in subsequent Salons. and the whole sequencein 1853 see of pictures displayed - or refused display - in the later 1860s. isK Herding. 'LesLutteurs "detestabIes":critique de Emperor Maximilian as the intended fo cus on the 1867 one-manmuch more open and erratic and rebarbative. (The Execution ofstyle, critique show ; The Balcony beside The Luncheon in the Studio in 1869; thesociale. Histoire etCritique des Arts, attempt to paint a big picture of a Bicycle Race in 1870.) But theno 4-5. May 1978. ambiguities of Manet's strategy are clear. What gives his workwhich again in the 1860s its peculiar force. and perhaps its continuing power ofexamines thecritical reaction example, is that at the same time as his art turns inward on itsin depth.own means and materials - clinging, with a kind of desperation.to the fragments of tradition left to it - it encounters and engagesa whole contrary iconography. Its subjects are vulgar; the fastidiousaction of paint upon tbem does not soften, but rather intensifies,their awk\ ....·ardness ; the painting's purpose seems to be to show usthe artifice of th is familiar repertoire of modern We. and . call inquestion the forms in which the city contrives its own appearance.Doing so. as we have seen, excluded Manet's are from the care andcomprehension of almost all his contemporaries; though whetherthat is mattcr for praise or blame depends, in the end. on our senseof the possible. now and then.41MANET Christ ins ult~par Ies soldats.Arc Institute of Chicago