the Brandenburg ostrich - Landesamt für Umwelt, Gesundheit und ...

the Brandenburg ostrich - Landesamt für Umwelt, Gesundheit und ...

the Brandenburg ostrich - Landesamt für Umwelt, Gesundheit und ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

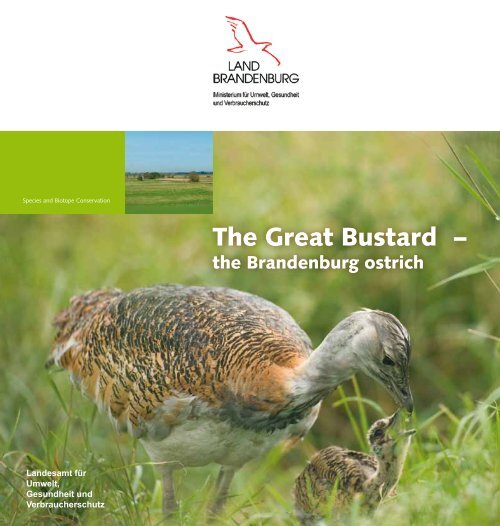

Species and Biotope ConservationThe Great Bustard –<strong>the</strong> <strong>Brandenburg</strong> <strong>ostrich</strong><strong>Landesamt</strong> für<strong>Umwelt</strong>,<strong>Ges<strong>und</strong>heit</strong> <strong>und</strong>Verbraucherschutz

The Great Bustard –<strong>the</strong> <strong>Brandenburg</strong> <strong>ostrich</strong>1

2 The Great Bustard – <strong>the</strong> <strong>Brandenburg</strong> <strong>ostrich</strong>ContentsThe Great Bustard – has it been saved?<strong>Brandenburg</strong>’s <strong>ostrich</strong>Once a steppe bird ... today on fields and meadowsOnce in <strong>the</strong> thousands in <strong>Brandenburg</strong> ... today a rare birdGreat Bustard looking for a wife ... and with successful matingCocks go traveling ... flight from hard wintersHelp in situ ... international responsibilitiesA look beyond <strong>the</strong> horizonA Bustard-friendly habitatPlease do not disturb!The artificial henFosterlings in needThe Great Bustard in conflictWings in <strong>the</strong> windWhat individuals can do for <strong>the</strong> Great BustardA feast for <strong>the</strong> eyes: observing BustardsBuckow: <strong>the</strong> cradle of <strong>Brandenburg</strong>’s Great Bustard conservationHand in HandAdditional informationLiterature, Internet, addressesImprint56681218202224262729313234384042444648

The Great Bustard – <strong>the</strong> <strong>Brandenburg</strong> <strong>ostrich</strong>3Did you know...that a mature male greatbustard can be as heavyas a deer, weighing up to17 kilograms? The greatbustard is among one of<strong>the</strong> heaviest flying birds in<strong>the</strong> world. Not only that,but <strong>the</strong> difference in weightbetween <strong>the</strong> male andfemale great bustard is greaterthan that of any o<strong>the</strong>rbird species in <strong>the</strong> world.

4 The Great Bustard – <strong>the</strong> <strong>Brandenburg</strong> <strong>ostrich</strong>Did you know...earlier <strong>the</strong> Great Bustardwas consideredbig game and couldonly be hunted by<strong>the</strong> kaisers, kings, andnobility? The administratorsof <strong>the</strong> king’scourt hunt recorded820 bustards killed byhunting in Prussia in<strong>the</strong> year 1900.Courtship display of a Great Bustard cock

6Habitat and BiologyThe <strong>Brandenburg</strong> <strong>ostrich</strong>Historical representationsof GreatBustards: from“Brehms Tierleben”(“Brehm’sAnimal Life”)1893 (above) aswell as <strong>the</strong> GreatBustard cock, artistunknown, archiveof H. Litzbarski(below)Once a steppe bird...The original habitats of <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard werewide-open steppe landscapes. Forest clearing in<strong>the</strong> Middle Ages created fields, meadows, andheathlands – so-called “cultured steppes” – thatwere attractive to <strong>the</strong> bustards and which <strong>the</strong>yquickly settled. In <strong>the</strong> 18th and 19th centuries <strong>the</strong>large birds belonged to <strong>the</strong> typical, widely distributedspecies on <strong>the</strong> agricultural lands of Europe.They were even present in sou<strong>the</strong>rn Sweden andin large parts of England.Did you know...earlier <strong>the</strong> GreatBustard was called<strong>the</strong> Ackertrapp (FieldBustard) or Trappgans(bustard goose)? InUpper Wendish it wascalled “Dudak” andin Lower Wendish“Groupun.”

Habitat and Biology7...today on fields and in meadowsAdditional habitats came about in Central Europewhen large swamps and lowland moors weredrained. Pure agricultural landscapes have sincelost <strong>the</strong>ir suitability for Great Bustards. But evengrassland by itself is not an optimal habitat becauseof its cool and moist microclimate and <strong>the</strong>corresponding vegetation structure. For decadesnow <strong>the</strong> coexistence of field and lowland moorshas characterized <strong>the</strong> habitat of <strong>the</strong> bustards inGermany.Although <strong>the</strong> species is able to get through <strong>the</strong>winter with just a few stems of rapeseed, itbelongs to <strong>the</strong> most demanding birds of agriculturallandscapes. For one, it requires large,contiguous, and <strong>und</strong>isturbed areas over which <strong>the</strong>bird can keep a good view. For ano<strong>the</strong>r it needsrichly-structured vegetation with light, sunnyareas. Many insects, spiders, worms, and o<strong>the</strong>rinvertebrate species live in this diverse plant worldthat <strong>the</strong> bustard requires for <strong>the</strong> rearing of <strong>the</strong>iryoung.

8Habitat and BiologyOne in a thousand in <strong>Brandenburg</strong>...Bustard hunter in <strong>the</strong>Middle Ages, afterGEWALT (1959).Distribution of <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard in <strong>Brandenburg</strong> in 1934, after GEWALT (1959).Did you know...The Great Bustard isstill considered ananimal that may behunted, although it isout of season for <strong>the</strong>whole year?The Mark <strong>Brandenburg</strong> was always <strong>the</strong> strongholdof <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard in Germany. That is why<strong>the</strong> bird is also known as <strong>the</strong> “Märkische Strauß”or <strong>Brandenburg</strong> <strong>ostrich</strong>. While <strong>the</strong> authoritiesvalued <strong>the</strong> bird for hunting and eating, <strong>the</strong>farmers always complained about <strong>the</strong> damage to<strong>the</strong>ir fields. For this reason one began to control<strong>the</strong> Great Bustards beginning in 1753 with <strong>the</strong>permission of Frederick II in order to reduce <strong>the</strong>damage to agriculture. At <strong>the</strong> beginning of <strong>the</strong>20th century school children still had to collectbustard eggs from <strong>the</strong> fields.In 1939, in <strong>the</strong> former Mark <strong>Brandenburg</strong>, <strong>the</strong>rewere aro<strong>und</strong> 3,400 bustards – more than half ofall <strong>the</strong> birds settled in Germany. The population<strong>the</strong>n sank rapidly in <strong>the</strong> following decades.

Habitat and Biology9...a rare birdThe intensification of agriculture since <strong>the</strong> middleof <strong>the</strong> 19th century f<strong>und</strong>amentally altered <strong>the</strong>conditions of <strong>the</strong> farming landscape and <strong>the</strong>rebydestroyed <strong>the</strong> habitat of numerous plants andanimals – also that of <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard. First <strong>the</strong>ydisappeared from <strong>the</strong> pure agricultural landscapes,later also from <strong>the</strong> marsh areas that increasinglybecame transformed into grassland monocultures.In <strong>the</strong> 1970s and 80s successful breeding of wildbustards in <strong>Brandenburg</strong> was already extremelyrare, although <strong>the</strong>re were still a few h<strong>und</strong>redindividuals. Many clutches of eggs fell victim to<strong>the</strong> frequent work processes on <strong>the</strong> farmland, andwhere chicks did hatch <strong>the</strong>y became trapped and<strong>the</strong>n starved in <strong>the</strong> high, dense, and insect-poorvegetation. The long life expectancy of <strong>the</strong> olderbirds alone was enough to delay <strong>the</strong> populationreductions. In today’s agricultural conditions inGermany suitable habitats for <strong>the</strong> Great Bustardscan only be retained in reserve areas with largescale,extensive land use and specially designedcultivation schemes.

10Habitat and BiologyCauses for <strong>the</strong> decline of <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard❚❚❚❚❚increase in mowing ando<strong>the</strong>r work processesintensive fertilizationpesticidessoil compactionhigher livestock densities❚❚❚❚time between work processesno longer sufficient forbreeding and rearingdense and high vegetationwith unfavorable microclimatespecies-poor plant stocksdecline in invertebrates(number of species andbiomass)❚❚❚❚large losses due to machineuse (clutches, young andadult birds)insufficient sunny areas for<strong>the</strong> chickshigh resistance to movementstarvation due to acute lackof invertebrates

Habitat and Biology11100 cm75 cm50 cm25 cm0 cmOnly extensively utilised meadows (right), arable land and fallow gro<strong>und</strong> offer enough food for great bustard chicks; <strong>the</strong>y have no chance ofsurvival in high, thick, intensively used grassland (left). The photo (below) shows an area of arable gro<strong>und</strong> which is particularly rich in insects.

12Habitat and BiologyGreat Bustard seeks a mate...Great bustards do not live in pairs, but in breedingcommunities (internationally know as “leks”).This can consist of up to 130 animals and take ina area of between 30 to 80 square kilometres.Outside <strong>the</strong> breeding period <strong>the</strong> adult bustardstend to live in groups split by gender, but <strong>the</strong>young of <strong>the</strong> last brood remain with <strong>the</strong> femalegroups. Males and females find one ano<strong>the</strong>r primarilyin <strong>the</strong> courting period.The birds return to <strong>the</strong> same place every year forcourting; as a rule <strong>the</strong>se are spots that have beenused for generations.Cocks skirmishingat <strong>the</strong> edge of <strong>the</strong>courting gro<strong>und</strong>.

Habitat and Biology13The courtship is an incredible sight. The cocktransforms himself into a large, white ball of fea<strong>the</strong>rs– to do so, he turns <strong>the</strong> brown, patterned flight fea<strong>the</strong>rsout so that <strong>the</strong> white <strong>und</strong>erside and <strong>the</strong> whitefea<strong>the</strong>rs of <strong>the</strong> elbow face upwards. The tail flipsup to <strong>the</strong> back and shows only <strong>the</strong> white down fea<strong>the</strong>rs.The long beard fea<strong>the</strong>rs stand straight up. Thetransformation is swift and complete. The puffed upneck makes <strong>the</strong> cock seem even bigger. Easily visiblefrom afar <strong>the</strong> cocks attract receptive females at agreat distance. In small, isolated groups <strong>the</strong> hens flyover 10, sometimes even 30 kilometers, to reach <strong>the</strong>cocks at <strong>the</strong> next breeding gro<strong>und</strong>. To brood <strong>the</strong>yreturn to <strong>the</strong>ir familiar territory, as <strong>the</strong> cocks haveno duties during <strong>the</strong> brooding and upbringingtimes whatsoever. It was previously thought that <strong>the</strong>hens usually bred within a five kilometre radius of<strong>the</strong> mating gro<strong>und</strong>. According to <strong>the</strong> latest resultsfrom Spain, <strong>the</strong> breeding gro<strong>und</strong>s are on average8 kilometres from <strong>the</strong> mating gro<strong>und</strong>, but can beup to a maximum of 54 kilometres away.The choice of partner is made by <strong>the</strong> hens. Theychoose one of <strong>the</strong> strongest cocks for <strong>the</strong> fertilizationof <strong>the</strong>ir eggs. For this reason <strong>the</strong> older hensare more likely to procreate.Did you know...during <strong>the</strong> courtship<strong>the</strong> heart rateof <strong>the</strong> cocks canreach 900 beatsper minute?

14Habitat and BiologyThe clutch consists of one to three (usually two)eggs, for which <strong>the</strong> hens merely construct a flathollow in <strong>the</strong> gro<strong>und</strong> of a field of grassland – usuallywithout any nesting material.

Habitat and Biology15Did you know...<strong>the</strong> adult animalseat herbs, floweringstocks, insects, andsmall mammals, but<strong>the</strong> young animalsare initially only fedon insects? In <strong>the</strong>first two weeks of lifeGreat Bustard chicksneed more than10,000 insects –almost a kilogram –in order to survive....and with successful matingAfter a brooding period of about 25 days <strong>the</strong> eggshatch, and <strong>the</strong> chicks weigh about 90 grams. Eventhough <strong>the</strong>y immediately leave <strong>the</strong> nest, <strong>the</strong>y areonly able to follow <strong>the</strong> hen clumsily and slowly in<strong>the</strong> first days of life.The hen continually feeds <strong>the</strong>m small bits of foodwith her beak: initially only insects. From <strong>the</strong> tenthday on <strong>the</strong> portion of plant fare increases dramatically.But without a sufficient source of insects <strong>the</strong>chicks have no chance of survival.

16 Habitat and BiologyEven though <strong>the</strong> young bustards are beginningto fly at four to five weeks, <strong>the</strong>y still try to avoiddangers for many weeks by squatting down into<strong>the</strong> gro<strong>und</strong> vegetation – a fateful strategy! For <strong>the</strong>n<strong>the</strong>y can be caught up in and killed by <strong>the</strong> farmmachines that work <strong>the</strong> fields and grasslands.Only after 10 to 12 weeks do <strong>the</strong>y try to flyaway – by that time having reached approximately<strong>the</strong> size of <strong>the</strong> hen. The male chicks quicklygrow larger than this, but even in <strong>the</strong> autumn <strong>the</strong>mo<strong>the</strong>r – now much smaller than <strong>the</strong>y – still feedssome of <strong>the</strong>m.Females usually become sexually mature at <strong>the</strong>age of 2, whereas males become sexually maturebetween 4 and 5 years old.

Habitat and Biology17Annual Cycle of <strong>the</strong> Great BustardOct.Sep.Nov.Aug.Dec.WINTERING IN GROUPSJulyCHICKSJan.BROODING TIMEJuneCOURTSHIP PERIODFeb.MayMar.April

18Habitat and BiologyCocks go traveling...The Great Bustards on Russian territory are almostexclusively migratory birds. Even <strong>the</strong> Spanish bustards,especially <strong>the</strong> cocks, change <strong>the</strong>ir territoryregularly between brood and wintering areas witha distance between <strong>the</strong>m of up to 250 kilometers.In contrast, <strong>the</strong> Central European Great Bustardsare significantly less mobile. Under normalcircumstances <strong>the</strong>y go no fur<strong>the</strong>r than 15 to 25kilometers from <strong>the</strong>ir brooding gro<strong>und</strong> outside of<strong>the</strong> breeding season.O<strong>the</strong>r migrations are <strong>und</strong>ertaken primarily by <strong>the</strong>cocks that haven’t yet reached reproductive age– less frequently by hens. These “excursions” cancover h<strong>und</strong>reds of kilometers in all directions.Earlier <strong>the</strong> birds would have met o<strong>the</strong>r membersof <strong>the</strong>ir species who <strong>the</strong>y could join. The fact that<strong>the</strong> migrations often “come to nothing” <strong>the</strong>sedays reduces <strong>the</strong> survival chances of <strong>the</strong> “bachelors.”Migrating great bustards also collide withoverhead powerlines; <strong>the</strong> risk of collision with windturbines has so far not been estimated.

Habitat and Biology19Severe winters causegreat loss among<strong>the</strong> bustards – after<strong>the</strong> 1978/89 wintermigration as well ashigh losses among<strong>the</strong> remaining birdsreduced <strong>the</strong> populationin Germany by45 percent....Flight from hard wintersOnly in winters with heavy snows do <strong>the</strong> localbirds stray far from <strong>the</strong>ir brooding gro<strong>und</strong>s, flyingwestward and sometimes even making an appearancein France. Escaping <strong>the</strong> winter in this way, ashappened in <strong>the</strong> winters of 2009/10 and 2010/11after almost a twenty-year break, always resultin losses. In <strong>the</strong> mild winters before 2009 <strong>the</strong>bustards remained “at home”. During times ofsnow it is possible to help <strong>the</strong> bird by clearing rapeseed fields, <strong>the</strong>ir preferred winter feeding gro<strong>und</strong>.It is possible that great bustards will be among <strong>the</strong>long-term winners of global warming, at least inCentral Europe.Models of Great Bustard and climate data predictthat <strong>the</strong> bustards could benefit from climatechange in East Germany more than in any o<strong>the</strong>rarea in Central Europe. But what is decisive is <strong>the</strong>type of land use <strong>und</strong>er <strong>the</strong>se new climate conditions.The international responsibility of Germanyto protect this species is <strong>the</strong>refore all <strong>the</strong> greater.Did you know...Great Bustards arepowerful and indefatigablefliers in spiteof <strong>the</strong>ir weight? Whilein Central Europe<strong>the</strong>y primarily live assedentary birds, inRussia <strong>the</strong>y are migratorybirds that migratecirca 1,000 kilometersto <strong>the</strong>ir winter quartersin Ukraine.

20ConservationHelp in situ...

Conservation21...international responsibilitiesMore than thirty areas in <strong>the</strong> former GDR weredesignated “bustard sanctuaries.” But effectiveconservation measures were only present in a fewof <strong>the</strong> areas. In all <strong>the</strong> places where <strong>the</strong> designation“bustard sanctuary” was only an emptyphrase <strong>the</strong> large birds have since disappeared.They survived only in areas where <strong>the</strong>re wereintense efforts to protect <strong>the</strong> birds and <strong>the</strong>irhabitat – in <strong>the</strong> Havelländisches Luch, <strong>the</strong> BelzigerLandschaftswiesen, and in <strong>the</strong> Fiener Bruch.Today <strong>Brandenburg</strong> State Office for Environmentis <strong>the</strong> supporting agency for <strong>the</strong> Great Bustardconservation project with significant help of <strong>the</strong>Great Bustard Conservation Fo<strong>und</strong>ation, which isalso active in Saxony-Anhalt. That is also where<strong>the</strong> state responsibility is located, at <strong>the</strong> LandkreisJerichower Land, Untere Naturschutzbehörde(Lower Conservation Administration of JerichowCounty).Buckow7003HavelländischesLuchBuckow<strong>Brandenburg</strong>a.d.HavelPotsdam<strong>Brandenburg</strong>a.d.HavelBaitzPotsdamFrankfurt (O.)7022Fiener Bruch7003Belziger BaitzLandschaftswiesenSpecial Protection Areas(SPA) according to<strong>the</strong> EC Birds Directive(79/409/EWG)Cottbus

22ConservationDid you know...<strong>the</strong> Great Bustard hasan enormous distributionreaching fromSpain to Mongolia,but that <strong>the</strong>y nowonly live in isolatedpopulations?A look beyond <strong>the</strong> horizonThe conservation of <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard in Germanyis part of an international effort to protectthis species. The basis is formed by European andeven international agreements – especially <strong>the</strong> ECBirds Directive that are aimed not only at <strong>the</strong> birds<strong>the</strong>mselves but also <strong>the</strong>ir habitats. These parts of<strong>the</strong> Europe-wide network NATURA 2000 havebeen designated as Special Protection Areas (SPA).This network consisting of SPAs and “special areasof conservation” pursuant to <strong>the</strong> FFH Directive,aims to help maintain <strong>the</strong> plant and animal worldin Europe – very much in <strong>the</strong> sense of <strong>the</strong> BiodiversityConvention that is supposed to ensure adiversity of life on Earth beyond just <strong>the</strong> EU. GreatBustards are a part of this diversity.There is even an agreement that is dedicated solelyto <strong>the</strong> Great Bustards in Central Europe – <strong>the</strong>so-called “Memorandum of Understanding.” Thissub-agreement of <strong>the</strong> Bonn Convention for <strong>the</strong>Conservation of Migratory Animals regulates <strong>the</strong>international efforts in research and protection of<strong>the</strong> Great Bustard. In this context <strong>the</strong>re have beentwo conferences at which <strong>the</strong> twelve signatorycountries agreed to an international work programand critically inspected <strong>the</strong> status of <strong>the</strong>implementation of <strong>the</strong> memorandum. The GreatBustard conservationists in <strong>Brandenburg</strong> workespecially closely with <strong>the</strong>ir colleagues in Spain,Austria, Hungary, Ukraine, and Russia. As a strictlyprotected species <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard also falls<strong>und</strong>er <strong>the</strong> trade restrictions of CITES.According to <strong>the</strong> Red List of Threatened Birds of<strong>the</strong> World <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard is considered “vulnerable”– this corresponds to category 3 “endangered”in Germany. Red lists are points of orien-tationfor conservation strategies and political decisions.On <strong>the</strong> Red List of birds in Germanyand <strong>Brandenburg</strong> <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard is ranked incategory 1, “threatened by extinction.”The State of <strong>Brandenburg</strong> is aware of its responsibilityand has implemented all possible measuresto protect and conserve <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard,for it was one h<strong>und</strong>red years ago that <strong>the</strong> Mark<strong>Brandenburg</strong> was <strong>the</strong> area in which <strong>the</strong> greatestnumber of Great Bustards lived in Germany, by far.

Conservation23The conservation of <strong>the</strong>Great Bustard in <strong>Brandenburg</strong>is achieved by...❚❚❚❚“Bustard-friendly” configurationof habitats and <strong>the</strong>extensification of agricultureminimizing disturbancesreintroduction of young bustards,as long as <strong>the</strong>re is anacute risk of extinctionefforts to protect <strong>the</strong> reproductionof bustards from <strong>the</strong>high predation pressure

Conservation25Did you know...bustards are moreclosely relatedto cranes than tochickens?109876543210198219831984198519861987198819891990199119921993199419951996199719981999200020012002200320042005200620072008200920102011The progress made by reptiles and amphibians after stopping <strong>the</strong> use of fertiliser and <strong>the</strong> discontinuation of ploughing of fieldsis represetativeof many groups of animal and plant species. In <strong>the</strong> picture <strong>the</strong> number of species ascertained in <strong>the</strong> “HavellandLuch” Nature Protection Area in what used to be an area of creeping velvet grassland and after <strong>the</strong> start of extensive utilisation.

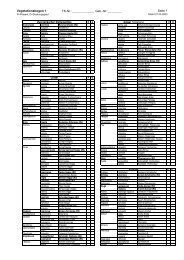

Conservation27The artificial henLarge-scale habitat protection began in <strong>the</strong> late1980s in <strong>the</strong> two bustard territories of <strong>the</strong> HavelländischesLuch and <strong>the</strong> Belziger Landschaftswiesen.Before <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> species could only beprotected by finding clutches during agriculturalwork and <strong>the</strong>n saving <strong>the</strong>m. But <strong>the</strong> brooded andraised young birds <strong>the</strong>n had to be released backinto <strong>the</strong> same unsuitable habitat from which <strong>the</strong>eggs came.Today <strong>the</strong> artificial incubation of rescued eggs and<strong>the</strong> rearing of young birds by humans is still a partof <strong>the</strong> protection strategy, but only as a complementto <strong>the</strong> protection of habitats. The goal is a“sustainable” population that requires no more artificialpopulation support. In <strong>the</strong> HavelländischesLuch this goal is already quite close.The results of <strong>the</strong> artificial brood and rearingTime frameHatching success ratesof fertilized eggsReleased birds as a percentageof hatched chicksNumber ofreleased birds1980-89 64,7 % 53,6 % 3381990-99 69,6 % 69,9 % 1432000 – 11 70,9 % 76,1 % 338This table shows <strong>the</strong> results of <strong>the</strong> brooding and rearing in recent decades. While <strong>the</strong> results of rearing haveconstantly improved, <strong>the</strong> brooding success rate has stabilized below 70 percent.

28ConservationThe eggs for <strong>the</strong> artificial brood are from clutchesinadvertently mown free, but are also sometimesspecifically ga<strong>the</strong>red. But doesn’t it endanger <strong>the</strong>population when <strong>the</strong> eggs are just “taken away”from <strong>the</strong> Great Bustards? Long-term observationshave shown that so-called “predators”, primarilyfoxes, eat a large percentage of <strong>the</strong> clutches. Notonly Great Bustards, but also many species thatbrood on meadows are increasingly suffering thisfate, and especially in large swaths of CentralEurope. For <strong>the</strong> Great Bustards it is primarily <strong>the</strong>earlier clutches that end in <strong>the</strong> stomachs of predators,at times when <strong>the</strong> vegetation doesn’t provideenough cover. Since <strong>the</strong>se eggs would be lostin any case and as <strong>the</strong> hens regularly lay severalsubsequent clutches <strong>the</strong> responsible parties in <strong>the</strong>Environmental Agency and <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard ConservationFo<strong>und</strong>ation decided to take a portion of<strong>the</strong>se clutches to brood and raise at <strong>the</strong> hands ofmen. The natural tendency to subsequent clutchesmeans that eggs are fo<strong>und</strong> into July and youngbirds into August. The rescued eggs are artificiallybrooded in an incubator and humans <strong>the</strong>n rear <strong>the</strong>hatched chicks. The bustards are not allowed toget used to being cared for like house pets.To ensure <strong>the</strong> freed birds behave in a mannerappropriate to <strong>the</strong> species it is necessary:❚ to reduce contact with humans to a minimum❚ to limit contact to a few, uniformly dressedpersons❚ to begin <strong>the</strong> process of returning <strong>the</strong>m to <strong>the</strong>wild at aro<strong>und</strong> six weeks.In <strong>the</strong> HavelländischesLuch <strong>the</strong> goalof a self-sustainingpopulation has almostbeen reached. Thepopulation, whichhas almost quadrupledsince 1996, wasbuilt largely withoutartificial brooding,but wouldn’t havebeen possible withoutintensive managementof <strong>the</strong> wild broodsinside a fox-proofprotection fence. Theslump in 2011 was aWinter flight caused.7060504030201001996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

Conservation 29Fosterlings in needOver centuries humans have changed <strong>the</strong> habitatof <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard and its entire plant andanimal world. Predator-prey relationships and competition between <strong>the</strong> individual species have tofind a new balance <strong>und</strong>er constantly changingconditions – ecologists speak of “dynamic equilibrium.”Many factors have led to <strong>the</strong> increasedfrequency in <strong>the</strong> last decades of animal speciesthat belong to <strong>the</strong> predators of bustards and<strong>the</strong>ir eggs, such as foxes and ravens. Additionally<strong>the</strong>re are invasive species such as <strong>the</strong> raccoon andraccoon dog that pose potential risks. This shift in<strong>the</strong> species structure primarily has negative effectson <strong>the</strong> reproduction of <strong>the</strong> Great Bustards, whichwould have reached rock bottom were it not forconservation efforts.This is a problem for many o<strong>the</strong>r bird species thatbrood on <strong>the</strong> gro<strong>und</strong>, not only in <strong>Brandenburg</strong>,but also in large parts of Central Europe. These include<strong>the</strong> lapwing, grey partridge, and <strong>the</strong> curlew.While foxes can also be a danger to adult bustards, raccoons (middle) and raccoon dogs (right) pose risks primarily to <strong>the</strong> clutches andyoung animals.

30ConservationWhile <strong>the</strong> hunt for Fox and o<strong>the</strong>r predatorymammals hasn’t improved <strong>the</strong> reproductionrate of <strong>the</strong> bustards, <strong>the</strong> fox-proof fences in<strong>the</strong> conservation areas have demonstrated<strong>the</strong>ir worth. With <strong>the</strong>ir sense for safety <strong>the</strong>free ranging adult hens now seek out <strong>the</strong>sefenced-in areas for <strong>the</strong>ir broods. Above allin <strong>the</strong> Havelländisches Luch <strong>the</strong>y prefer <strong>the</strong>“pens” to <strong>the</strong> surro<strong>und</strong>ing landscape. Up to15 hens brood here at once on an area of 18hectares and bear up to 11 fledged youngper year – significantly more than outside <strong>the</strong>protection fences. One can hope that this aidmeasure will only be temporarily necessaryand that <strong>the</strong> bustards will one day be able tosuccessfully brood in <strong>the</strong> wild.20181614121086420Number of fledged youngper year1990199119921993199419951996199719981999200020012002200320042005200620072008200920102011500450400350300250200150100500gef<strong>und</strong>eneBrutplätzeOpen landProtection fencegeschlüpfteKükenflügge KükenProtecting <strong>the</strong> birds from gro<strong>und</strong> predators in <strong>the</strong> fenced-in areas has led toan increasing reproduction rate in <strong>the</strong> German Great Bustard project.Comparison of <strong>the</strong> reproduction rate in <strong>the</strong> wild and in <strong>the</strong>fenced-in areas in <strong>the</strong> Havelländisches Luch 1990-2011.

Conservation 31Great Bustard in ConflictThe Great Bustard achieved an ambiguous famein some media outlets in <strong>the</strong> 1990s as “<strong>the</strong> mostexpensive bird in <strong>the</strong> world.” The reason behindthis was <strong>the</strong> railway line from Berlin to Hannoverthat went right through <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard territoryin <strong>the</strong> Havelländisches Luch. What had previouslyonly been used as noise control for human settlementswas now to be used to protect <strong>the</strong> bustards– walls on ei<strong>the</strong>r side of <strong>the</strong> tracks to avoidcollisions between <strong>the</strong> birds and <strong>the</strong> trains or <strong>the</strong>iroverhead wires.The project was a complete success for all involved,including <strong>the</strong> Deutsche Bahn (GermanRailway). The section of <strong>the</strong> line was completedon time and <strong>the</strong> costs came in <strong>und</strong>er budget. Theyamounted to a small portion of what <strong>the</strong> alternatives– a long bypass or a tunnel – would havecost. The implemented measures are also advantageousfor many o<strong>the</strong>r bird species as well asbeavers and European otters, for which a specialpassage beneath <strong>the</strong> tracks was built. The bustards<strong>the</strong>mselves tolerate <strong>the</strong> train line.Did you know...Great Bustardssleep on <strong>the</strong>irbelly? They pull<strong>the</strong>ir headbetween <strong>the</strong>irshoulders.The “BustardWall” also allowso<strong>the</strong>r birds, such as<strong>the</strong> cranes (above)to safely cross <strong>the</strong>train line.

32ConservationWings in <strong>the</strong> windThe conflict between <strong>the</strong> wind turbines and <strong>the</strong>Great Bustards has fo<strong>und</strong> resonance in <strong>the</strong> media.The large wind turbines change <strong>the</strong> landscape andcan obstruct habitats and flight paths. To some species<strong>the</strong>y also pose an accident risk. To date no GreatBustards are known to have fallen victim, but studieshave only been conducted in a few wind parks.At present we don’t know how <strong>the</strong>se large birdswill behave toward <strong>the</strong> wind parks within <strong>the</strong>irtraditional migration routes. However it has beenshown that <strong>the</strong> bustards avoid a wind park on <strong>the</strong>edge of <strong>the</strong> Fiener Bruch and have <strong>the</strong>reby lostan important part of <strong>the</strong>ir habitat.Whe<strong>the</strong>r this will have an effect on <strong>the</strong> largerpopulation is not yet clear. A gradual acclimatizationof at least some animals – as with o<strong>the</strong>rspecies – is not out of <strong>the</strong> question, but would<strong>the</strong>reby increase <strong>the</strong> risk of collision.A recent study has shown that currently onlyaro<strong>und</strong> 10% <strong>the</strong> environment of <strong>the</strong> last threeGerman great bustard territories is uninterruptedand <strong>und</strong>eveloped and <strong>the</strong>refore of use to <strong>the</strong> greatbustard.

Conservation 33Compensation and mitigation for <strong>the</strong> wind parksis meant to ensure that <strong>the</strong> ability of <strong>the</strong> potentiallyaffected species to maintain <strong>the</strong>mselves is notdamaged. Thus, for example, <strong>the</strong> extensificationof agricultural areas with terms of up to 20 yearsare being financed. Parallel to this is a monitoringeffort – that is an investigation into <strong>the</strong> effectson <strong>the</strong> animal world, including <strong>the</strong> Great Bustards.The results will be made available for futureplanning.Recent developments in <strong>the</strong> agricultural politicshave added to <strong>the</strong> plight of <strong>Brandenburg</strong>’s <strong>ostrich</strong>:<strong>the</strong> increasing orientation toward regenerativeresources as a source of energy means afur<strong>the</strong>r reduction in <strong>the</strong> species’ habitat. Areasthat were designated fallow land by <strong>the</strong> EU until2007 are now being planted with corn, sorghum,and o<strong>the</strong>r fast growing cultures. In <strong>Brandenburg</strong><strong>the</strong> percentage of fallow land was reduced by45 percent within one year. Fur<strong>the</strong>r habitats for<strong>the</strong> Great Bustard are disappearing, for example<strong>the</strong>ir “stepping stones” outside <strong>the</strong> conservationareas.Did you know...<strong>the</strong> Great Bustardcannot stand onone leg like a storkbecause it doesn’thave a hind toe?Many speciessuffer from <strong>the</strong>reduction of fallowland, including <strong>the</strong>corn bunting (left)and <strong>the</strong> whinchat(right).

34ConservationWhat individuals can do for <strong>the</strong> Great BustardFarmers in <strong>the</strong> nature reserves “HavelländischesLuch” and “Belziger Landschaftswiesen” areincluded in <strong>the</strong> conservation efforts. They workwithin <strong>the</strong> guidelines of <strong>the</strong> Agri-EnvironmentalPrograms and <strong>the</strong> conservation agreementsand have adapted <strong>the</strong> farming practices towardbustard-friendly land use. There are similarapproaches for <strong>the</strong> third remaining Great Bustardterritory: <strong>the</strong> “Fiener Bruch.” In all three areasbustard conservationists maintain regular contactwith <strong>the</strong> hunters, who for <strong>the</strong>ir part, consider <strong>the</strong>demands of <strong>the</strong> Great Bustards. As <strong>the</strong> numberof bustards increases one can expect to also findbroods outside of <strong>the</strong> protected areas. Therefore<strong>the</strong> attention and support of <strong>the</strong> farmersand hunters in <strong>the</strong> broader surro<strong>und</strong>ings of <strong>the</strong>protected areas are also important. Above allwhen <strong>the</strong>re is a brood or suspicion of one <strong>the</strong>responsible institutions should be contacted (see“Addresses” on p. 47).

Conservation 35With <strong>und</strong>erstanding and consideration visitorsand inhabitants of <strong>the</strong> surro<strong>und</strong>ing communitieshelp to protect <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard. Only approvedroutes and paths should be used, and <strong>the</strong> necessaryprohibitions against entry and closed areasshould be tolerated. Disturbances do not justbo<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> bustards but also visitors who havetravelled from afar only to find an empty courtinggro<strong>und</strong>. Please heed <strong>the</strong> instructions on <strong>the</strong> informationboards in <strong>the</strong> protected areas.Notification of Great Bustard sightings, particularlyoutside <strong>the</strong> known territories, are alwaysappreciated by <strong>the</strong> responsible institutions. Theycomplete our picture of <strong>the</strong> bustards’ room use,fill gaps in <strong>the</strong> ongoing monitoring, and can aid inintegrating <strong>the</strong> farmers of <strong>the</strong> relevant land usedby <strong>the</strong> birds. Ornithologists with good opticalequipment should, if <strong>the</strong>y discover a Great Bustard,pay attention to <strong>the</strong> ringing of <strong>the</strong> birds. Thecolored leg rings can be seen with binoculars upto a point. The reading of <strong>the</strong> ring codes requiresa good spotting scope with which <strong>the</strong> necessarydistance can be kept.Whoever would like to do morefor <strong>the</strong> Great Bustards...is welcome to get in contact with a staffmember at <strong>the</strong> care centers (see “Addresses”on page 47). Support is also possible through<strong>the</strong> Great Bustard Conservation Fo<strong>und</strong>ation.

36ConservationFor more than ten years now Great Bustards areequipped with transmitters to follow <strong>the</strong>ir movements;tail and neck transmitter (small photo),backpack transmitter (large photo).

Conservation 3716014012010080rescued eggsfledged youngyoung set freewild populationDid you know...Great Bustards canlive to be 20 to 25years old?60402001990199119921993199419951996199719981999200020012002200320042005200620072008200920102011The overall conservation measures are currently leading to an increase in <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard population in Germany– <strong>the</strong> first time after decades of decreases. The chart shows that setting birds free as well as a stabile number offledged young bustards contribute to <strong>the</strong> population increases.A striking demonstrationof<strong>the</strong> difference insize, between <strong>the</strong>cock and hen.

38ObservationA feast for <strong>the</strong> eyes: observing bustards

Observation39For <strong>the</strong> viewer it is an unforgettable experiencewhen, in <strong>the</strong> failing light at dusk, <strong>the</strong> cock birdstransform <strong>the</strong>mselves from dull shapes to brilliantwhite beacons and <strong>the</strong>n almost disappear again.In order to enjoy this spectacle of <strong>the</strong> bustard’scourtship without disturbing <strong>the</strong> birds <strong>the</strong>re arethree observation towers in <strong>the</strong> HavelländischesLuch and <strong>the</strong> Belziger Landschaftswiesen. They areopen year ro<strong>und</strong> and no registration is necessary(see map section on pages 42 and 43). With alittle luck one might also meet a barn owl in <strong>the</strong>towers; <strong>the</strong>y leave <strong>the</strong>ir traces in <strong>the</strong> form of whitesplotches.In mild wea<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> courting of <strong>the</strong> bustardsbegins as early as February and continues on – ifnot so intensely – until <strong>the</strong> early summer. The bestbustard observations can generally be made from<strong>the</strong> beginning of April to <strong>the</strong> end of May. Themorning and evening hours are particularly suitable,although in <strong>the</strong> fen mires it can be foggy in<strong>the</strong> early hours. As summer approaches <strong>the</strong> bustardsare increasingly “invisible.” It is occasionallypossible to see <strong>the</strong> birds from <strong>the</strong> road, for examplein <strong>the</strong> winter months when <strong>the</strong>y leave <strong>the</strong>core areas of <strong>the</strong> protected area. Sometimes <strong>the</strong>bustards stand on <strong>the</strong> side of <strong>the</strong> road, but quicklyincrease <strong>the</strong>ir distance from stopping cars andespecially people getting out of cars by severalh<strong>und</strong>red meters. Good optics can help you see <strong>the</strong>birds well from a greater distance withoutGuests from all over Europe and even from abroadvisit <strong>the</strong> observation tower in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Brandenburg</strong> GreatBustard territories.disturbing <strong>the</strong>m. If you adapt to <strong>the</strong> bustards, youhave a good chance of experiencing <strong>the</strong> birds and<strong>the</strong>ir natural habitat.During <strong>the</strong> courting period <strong>the</strong> Great BustardConservation Fo<strong>und</strong>ation offers a visitors’ servicein <strong>the</strong> exhibition of <strong>the</strong> Bird Conservation Centrein Buckow as well as guided excursions. Detailscan be fo<strong>und</strong> on <strong>the</strong> Internet site of <strong>the</strong> fo<strong>und</strong>ationas well as in <strong>the</strong> local media. The rangers of<strong>the</strong> Westhavelland Nature Park also offer GreatBustard tours.

40State Bird Conservation CentreBuckow: <strong>the</strong> cradle of <strong>Brandenburg</strong> Great Bustard conservation1978 marks <strong>the</strong> “birth hour” of <strong>the</strong> Buckow NatureConservation Station in <strong>the</strong> HavelländischesLuch. Changes in <strong>the</strong> organization of state natureconservation, greater personal commitment, anda great deal of voluntary support have ensuredthat in 1979 full-time work for <strong>the</strong> protection of<strong>the</strong> Great Bustard could begin.

State Bird Conservation Centre41From <strong>the</strong> beginning <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard has been adominant species – a representative of <strong>the</strong> manyo<strong>the</strong>r animal and plant species on farmlands thatwere afflicted by <strong>the</strong> intensification of agriculture.The spectrum of tasks ranged from f<strong>und</strong>amentalwork like research and bird censuses to practicallandscape work, seminars with farmers and volunteerconservationists all <strong>the</strong> way to coordinatedefforts in conservation.Fo<strong>und</strong>ing district work groups – for predatorybirds or mammals – helped pool voluntarycommitment. International conferences for <strong>the</strong>Great Bustard were a sign of cooperation beyondcountry borders; two of <strong>the</strong>m took place in <strong>the</strong>region that is today <strong>Brandenburg</strong>. The focus wason questions regarding <strong>the</strong> causes of <strong>the</strong> speciesretreat and <strong>the</strong> possible counter measures thatcould be done through conservation. Even during<strong>the</strong> GDR period is was possible in Westhavellandand in <strong>the</strong> Belziger Landschaftswiesen to removeseveral thousand hectares from intensive cultivationand introduce extensive use. For <strong>the</strong> first timeit was possible to protect <strong>the</strong> habitat – going farbeyond <strong>the</strong> previous possibilities.Protection of species diversity on farmland – from <strong>the</strong> beginning thishas been <strong>the</strong> core of <strong>the</strong> Buckow Nature Conservation Station’s work.Eurasian curlew (above); a field’s edge in bloom (below).

42State Bird Conservation CentreStechowB 188Ra<strong>the</strong>nowBammeFriesackL 982L 991GräningenL 98BahnhofNennhausenMützlitzNennhausenBuckow b.NennhausenMarzahne,<strong>Brandenburg</strong>an der HavelL 991L 982Bus 572/574Ra<strong>the</strong>now - KieckRa<strong>the</strong>now - MützlitzGarlitzMarzahne,<strong>Brandenburg</strong>an der HavelLiepeDammeTurmBuckowTurmGarlitzHand in HandThe political upheaval in 1989 brought new opportunitiesfor <strong>the</strong> conservation of Great Bustards.Privatization and a new orientation of agriculturewere used to improve <strong>the</strong> situation for <strong>the</strong> GreatBustard in <strong>the</strong> territories of <strong>the</strong> HavelländischesLuch, Belziger Landschaftswiesen and <strong>the</strong> FienerBruch in cooperation with farmers. Since 1991this has been carried out <strong>und</strong>er <strong>the</strong> auspices of<strong>the</strong> <strong>Brandenburg</strong> State Office for Environment.LIFE projects forged <strong>the</strong> preconditions for <strong>the</strong>subsequent agricultural-environmental measuresand <strong>the</strong> permanent protection of <strong>the</strong> areas. Thiswas also aided by <strong>the</strong> acquisition of land for GreatBustard conservation, supported by sponsorssuch as <strong>the</strong> Zoologische Gesellschaft Frankfurt(Frankfurt Zoological Society). A fo<strong>und</strong>ation for<strong>the</strong> protection of <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard was established.International cooperation in research andconservation also gained tailwind. From Spain toMongolia <strong>the</strong>re is no country with Great Bustardsthat hasn’t in <strong>the</strong> past or doesn’t now take partin common activities. In 1995 an internationalconference on <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard took place in<strong>Brandenburg</strong> from which comprehensive proceedingswere created.The first twenty years of <strong>the</strong> nature protectionstation are inseparably linked with <strong>the</strong> names DrHeinz Litzbarski and Dr Bärbel Litzbarski, who werehonoured for <strong>the</strong>ir dedication in 2011 with <strong>the</strong>Order of Merit of <strong>the</strong> Federal Republic of Germany.In later decades Heinz Litzbarski was active as <strong>the</strong>head of <strong>the</strong> fo<strong>und</strong>ation for Great Bustard conservationfor which he received <strong>the</strong> Nature ConservationPrize of <strong>the</strong> State of <strong>Brandenburg</strong> in 2008.

State Bird Conservation Centre43In 1998 – restructuring and a fresh start. Out of<strong>the</strong> “Bustard Station” comes <strong>the</strong> <strong>Brandenburg</strong>State Bird Conservation Centre with <strong>the</strong> NatureConservation Station in Baitz as satellite station.GolzowFreienthalThe area of responsibility is expanded to include<strong>the</strong> entire state and a variety of new tasks areadded – bird conservation even outside xx farmland,conservation projects for o<strong>the</strong>r endangeredspecies, <strong>the</strong> coordination of bird monitoring andbird ringing in <strong>Brandenburg</strong>, new topics such asclimate change or <strong>the</strong> interplay between windenergy and bird conservation.Parallel to this was <strong>the</strong> continuing work on site.The cooperation with <strong>the</strong> farms had to beconstantly reorganized <strong>und</strong>er changing guidelines,not only to protect <strong>the</strong> bustards but also <strong>the</strong>farmers who are managing <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard’shabitats.All this also required a reorganization of <strong>the</strong> divisionof labor with <strong>the</strong> fo<strong>und</strong>ation that took on aportion of <strong>the</strong> practical work as well as <strong>the</strong> publicrelations work for <strong>the</strong> conservation of <strong>the</strong> GreatBustard. The care of <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard projectgoes hand in hand today, not least because <strong>the</strong>fo<strong>und</strong>ation and <strong>the</strong> bird protection station areboth located in <strong>the</strong> same place.BaitzB102SchwanebeckBelzigLüsseTurm BelzigerLandschaftswiesenSchutzhütte amRadweg 1Bhf. BaitzB 246PlaneNeschholzTrebitzGrömnigkBrückLeipzigBhf. Brück(Mark)ASTLin<strong>the</strong>A9A9ASTBeelitzBerlinerRingLin<strong>the</strong>TreuenbrietzenMap sections and photos of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Brandenburg</strong> State BirdConservation Centre in Buckow (left) and its satellitestation in Baitz (right).

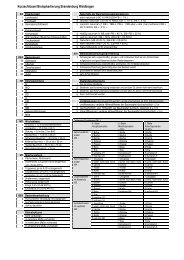

44InformationAdditional information...Status of <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard in EuropeIndividual count for <strong>the</strong> 2008 breeding seasonMin. Max. Trend since 2004 AccuracySpain 27.500 30.000 + ARussia 6.000 12.000 - BPortugal 1.399 1.399 + AHungary 1.378 1.378 + ATurkey 762 1.250 - BUkraine 520 680 - BAustria 185 198 + AGermany 110 110 + ASerbia 35 38 0 ACzech Republic 0 2 0 ABulgaria 0 6 - CMoldavia 0 0 0 CRumania 0 8 ? CSlovakia 0 3 - AGreat Britain(Reintroduction project) 7 15 + ATotal 37.896 47.087Accuracy: A – very accurate, B – relatively accurate, C – uncertainInternational cooperation in Great Bustard conservation: <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard Conservation Fo<strong>und</strong>ationat work on projects in Russia, Mongolia, and Spain (from left to right).

Information45National and international legal fo<strong>und</strong>ationsEuropean Bird Conservation GuidelinesThe EC Birds Directive (79/409/EWG from April 2, 1979) came into effect in 1979. It forms <strong>the</strong>legal fo<strong>und</strong>ation for <strong>the</strong> EU-wide protection of all native, wild bird species. It aims to conserve orrestore a sufficient diversity and habitat area for <strong>the</strong> European bird species in <strong>the</strong> EU.Bonn Convention for <strong>the</strong> Conservation of Migratory SpeciesThe agreement for <strong>the</strong> protection of migratory wild animal species was signed on June 23, 1979.The agreement includes <strong>the</strong> duties of <strong>the</strong> signatory countries: measures for <strong>the</strong> worldwide protectionof migratory animal species. Worldwide it is estimated that <strong>the</strong>re are 8,000 to 10,000 migratoryanimal species. Aro<strong>und</strong> 1,200 species, or regionally delimited populations, are included in <strong>the</strong>agreement that are acutely threatened by extinction or whose population is <strong>und</strong>er great danger.Memorandum of UnderstandingAgreement between several countries in <strong>the</strong> framework of <strong>the</strong> Bonn Convention, that aims toresearch and protect specific species or species’ groups.Biodiversity ConventionThe preservation of biological diversity is <strong>the</strong> object of this internationally binding treaty since <strong>the</strong>UN Conference for Environment and Development held in Rio de Janeiro. The most importantgoals are:❚ <strong>the</strong> protection of biological diversity,❚ sustainable use and,❚ <strong>the</strong> fair division of benefits from <strong>the</strong> use of genetic resources. To this end countries must developnational strategies and action plans. In <strong>the</strong> implementation of <strong>the</strong> convention <strong>the</strong> industrializedcountries are required to support <strong>the</strong> developing countries.Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).International agreement between governments. Its aim is to ensure that international trade inspecimens of wild animals and plants does not threaten <strong>the</strong>ir survival.

46InformationLiteratureInternationaler Workshop „Conservation and Managementof <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard in Europe”.Naturschutz <strong>und</strong> Landschaftspflege in <strong>Brandenburg</strong> 5, Heft 1/2: 120 S. (1996)BLOCK, B., P. BLOCK, W. JASCHKE, B. LITZBARSKI,H. LITZBARSKI & S. PETRICK (1993):Komplexer Artenschutz durch extensive Landwirtschaft im Rahmen des Schutzprojektes „Großtrappe“.Natur <strong>und</strong> Landschaft 68: 565-576EISENBERG, A., T. RYSLAVY, M. PUTZE & T. LANGGEMACH (2002):Ergebnisse der Telemetrie bei ausgewilderten Großtrappen (Otis tarda) in <strong>Brandenburg</strong> 1999-2002.Otis 10: 133-150Eschholz, N. (1996):Großtrappen (Otis t. tarda L., 1758) in den Belziger Landschaftswiesen.Naturschutz <strong>und</strong> Landschaftspflege in <strong>Brandenburg</strong> 5, Heft 1/2: 37-40Gewalt, W. (1954):Die großen Trappen. Verlag Dietrich Reimer. Berlin. 178 S.Gewalt, W. (1959):Die Großtrappe. Die Neue Brehm-Bücherei. A. Ziemsen Verlag. Wittenberg Lu<strong>the</strong>rstadt. 124 S.LANGGEMACH, T. & H. LITZBARSKI (2005):Results of Artificial Breeding in <strong>the</strong> German Great Bustard (Otis tarda) Conservation Project.Aquila 112: 191-202LITZBARSKI, B. & H. LITZBARSKI (1996):Zur Situation der Großtrappen Otis tarda in Deutschland. Vogelwelt 117: 213-224LITZBARSKI, H. & N. ESCHHOLZ (1999):Zur Bestandsentwicklung der Großtrappe (Otis tarda) in <strong>Brandenburg</strong>. Otis 7: 116-122LITZBARSKI, H. & H. WATZKE (Hrsg.) (2007):Great Bustards in Russia and Ukraine. Bustard Studies 6. 138 S.SCHWANDNER, J. & T. LANGGEMACH (2011): Wie viel Lebensraum bleibt der Großtrappe (Otis tarda)?Infrastruktur <strong>und</strong> Lebensraumpotenzial im westlichen <strong>Brandenburg</strong>. Ber. Vogelschutz 47/48: 193-206

Information47Internet ResourcesAddresseswww.mugv.brandenburg.de/info/vogelschutzwartewww.grosstrappe.dewww.grosstrappe.atwww.tuzok.mme.huwww.greatbustard.comwww.proyectoavutarda.comwww.cms.intwww.birdlife.orgState Office of Environment, Health andConsumer Protection of <strong>the</strong> Federal Stateof <strong>Brandenburg</strong>Staatliche Vogelschutzwarte(<strong>Brandenburg</strong> State Bird Conservation Centre)Buckower Dorfstraße 34D-14715 Nennhausen, Ortsteil BuckowTel. 033 878 / 60 257Fax 033 878 / 60 600vogelschutzwarte@lugv.brandenburg.deState Office of Environment, Health and ConsumerProtection of <strong>the</strong> Federal State of <strong>Brandenburg</strong><strong>Brandenburg</strong> State Bird Conservation Centre,satellite station BaitzIm Winkel 13D-14822 Brück, Ortsteil BaitzTel. / Fax 033 841 / 30 220doris.block@lugv.brandenburg.deFörderverein Großtrappenschutz e. V.(Great Bustard Conservation Fo<strong>und</strong>ation)c./o.: Staatliche Vogelschutzwarte (Buckow)Tel. 033 878 / 60 194Fax 033 878 / 60 600bustard@t-online.deFörderverein Großtrappenschutz e. V.(Great Bustard Conservation Fo<strong>und</strong>ation)Geschäftsstelle Königsroder HofKönigsrode 1D-39307 TucheimTel. 0174 / 71 41 683<strong>Landesamt</strong> für<strong>Umwelt</strong>,<strong>Ges<strong>und</strong>heit</strong> <strong>und</strong>Verbraucherschutz

48InformationImprintPublisherMinistry of Environment, Health andConsumer Protection State of <strong>Brandenburg</strong>Heinrich-Mann-Allee 10314473 PotsdamState Office of Environment, Health and ConsumerProtection of <strong>the</strong> Federal State of <strong>Brandenburg</strong>Editor: Office for Environmental Information /Public RelationsSeeburger Chaussee 2D-14476 PotsdamTel. 033 201 / 442 (0)-171Fax 033 201 / 436 78infoline@lugv.brandenburg.dewww.lugv.brandenburg.deSpecialist EditingTorsten LanggemachDepartment of Ecology, Conservation, WaterOffice Ö2Staatliche VogelschutzwarteBuckower Dorfstraße 34D-14715 Nennhausen, OT BuckowTel. 033 878 / 60 257Fax 033 878 / 60 600vogelschutzwarte@lugv.brandenburg.dewww.mugv.brandenburg.de/info/vogelschutzwarteWe thank <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard ConservationFo<strong>und</strong>ation for <strong>the</strong>ir supportTranslationSydem Sprachdienstwww.sydem.comFotosTitle page: D. NillB. Block (small photo)U 2 <strong>und</strong> p. 1: D. NillU 3: F. KovacsArchive of <strong>the</strong> Great Bustard ConservationFo<strong>und</strong>ation: p. 33 bottom r.S. Bich: p. 28T. Bich: p. 14 topB. Block: pp. 11, 14 backgro<strong>und</strong>, 15 bottom,17 backgro<strong>und</strong>, 18, 20, 24 o., 25, 27, 31 o., 33 o.,34 u., 35, 36 bottom, 38 bottom, 39, 40 bottom,41 l. and bottomP. Block: p. 30C. Blumenstein: p. 5J. Chobot: p. 14 bottomN. Eschholz: p. 7N. Kraneis: p. 40 topI. Langgemach: p. 42T. Langgemach: p. 10H. Litzbarski: pp 9, 15 bottom, 19, 22, 31 bottom,32 bottom, 33 bottom l., 37, 41 top r., 44D. Nill: pp 1, 3, 4, 12, 13, 16, 21, 23, 26, 29 top,bottom l., 32 top., 38 top.F. Plücken: p. 24 bottomJ. Teubner: p. 29 bottom center and r.Y. von Gierke: p. 34 top l. and r., 36 topDrawings: Nikolai KraneisDesign: Goscha Nowak, BerlinSecond edition, As of May 2012printed on® FSC-certified paper

Ministry for Environment, Health,and Consumer Protection State of <strong>Brandenburg</strong>Office of Press and Public RelationsHeinrich-Mann-Allee 10314473 PotsdamTel.: 0331 / 866 70 17Fax: 0331 / 866 70 18pressestelle@mugv.brandenburg.dewww.mugv.brandenburg.deState Office of Environment, Health and ConsumerProtection of <strong>the</strong> Federal State of <strong>Brandenburg</strong>Office of Environmental Information, Public RelationsSeeburger Chaussee 214476 Potsdam, OT Groß GlienickeTel.: 033 201 / 44 21 71Fax: 033 201 / 43 678infoline@lugv.brandenburg.dewww.mugv.brandenburg.de/info/lugvpublikationen