The Six Escapes - Finding Lost Civilizations

The Six Escapes - Finding Lost Civilizations

The Six Escapes - Finding Lost Civilizations

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

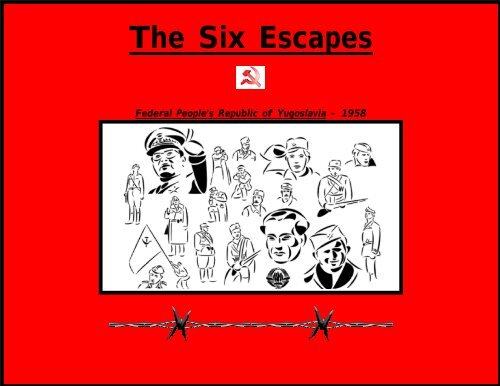

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Six</strong> <strong>Escapes</strong>Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia - 1958

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Six</strong> <strong>Escapes</strong>ByRafael AugustinPublished ByAlexander KerekesCarmel, California USA

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Six</strong> <strong>Escapes</strong>ByRafael AugustinAll rights reserved under International and Pan-Americancopyright conventions. No part of this book may be usedor reproduced in any manner whatsoever withoutwritten permission except in the case ofbrief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.Printed in the U.S.A.First U.S. Edition December 2009Published byAlexander KerekesCarmel, Californiawww.storiesbyalex.com

Chapters:Introduction..................................................................................................6First Escape..................................................................................................7Second Escape..............................................................................................11Third Escape.................................................................................................25Fourth Escape..............................................................................................41Fifth Escape.................................................................................................46<strong>Six</strong>th Escape – Freedom............................................................................59

IntroductionYugoslavia was a former country ofsoutheast Europe bordering on the AdriaticSea. It was formed in 1918 as the Kingdomof Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes after thecollapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empireand was renamed Yugoslavia in 1929.Communist party control ended in 1990,and four of the six republics, Slovenia,Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, andMacedonia declared independence in1991.<strong>The</strong> <strong>Six</strong> <strong>Escapes</strong> takes place in1958 - 1959 and is a true story of RafaelAugustin’s six attempts to flee from atyrannical regime, his capture,imprisonment, and his final miraculous anddesperate escape to Germany via Austriato seek asylum for a better life in Canada.This story is a true testament to thedesire of the human spirit to be free.Rafael and his beautiful lady, Yolanda, livinga free and beautiful life in San Pedro deLagunillas, Mexico

<strong>The</strong> First Escape - 1958I chose May 1 st for two good reasons.One, it was a national holiday and walkingsome 20 kilometers to a town near theAustrian border would be less suspicious.Second, one of my technical schoolcolleagues told me that he lived near theAustrian border and that on 1 May manylocal people would be drinking andcelebrating all night at the local restaurant/ bar.My friend Josef and I had a few days toget ready and promised to tell absolutelynobody of our plan. We would travel lightand I brought two shirts, a suit, shoes, araincoat, and a package of ground blackpepper mixed with hot red pepper. <strong>The</strong>pepper was meant for nasty farm andborder dogs. Also, I managed to buy on theblack market some Austrian schillings,since the banks weren't allowed to sellforeign money to the general public. Nowwe were ready for the escape.We met at 5 p.m. on May 1 st at the OrelHotel in Moribor, and by sundown webegan walking toward the border, some 15kilometers away. <strong>The</strong> first few kilometerswas on paved road, then on a gravellymountain country road. We passedoccasional farms, but soon ascending tothe forested mountain. At one time aGerman Shepard dog attacked us. But, Isprinkled on the ground some of mypepper, which the dog sniffed and thensneezed and ran home. On a fewoccasions we hid in the forest to hide fromthe people passing by. Here the peoplewere known to report people to the local

police or the border guards when seeingstrangers near the border. At one time weheard a sneaky dog snarling at us, whenhis owner showed up on a bicycle. <strong>The</strong>man stepped off the bicycle and asked,“Where are you going?” I said,” To meetmy friend and to celebrate May Ist, at therestaurant.” He replied, "Oh yes, there arealready a lot of people and music." He goton his bike and continued down hill.Walking another 15 minutes, we heard themusic. It was about 10 p.m. We observedthe place carefully from a distance, seeingpeople but no border guards. Slowly weapproached and walked in while mosteverybody was dancing. We sat down at acorner table, and ordered a dinner withdrinks. Meanwhile, I noticed a uniformedborder guard dancing, which made meuncomfortable. Our plan was to cross theborder at 2 a.m. According to ourinformation, it was best time, since theborder guards were changing shifts andthus, any noise made by us while crossingwouldn't be so suspicious.From across the room one of my schoolcolleagues recognized me and came togreet me. We talked about the school, andthen I asked him if he lived up the hillcloser to the border. I thought this mightgive me a better idea of the location of theborder. He said, "Yes, it's just 10 minutes’walk." After a while he left to visit withsome friends. Later, I noticed that he wastalking to the boarder guard, who looked atus. I was sure that we were in trouble. I toldmy companion friend that it would be best ifwe go through the kitchen and cross the

order immediately, despite the fact that itwas now only about midnight.We discreetly sneaked through thekitchen but once outside, four soldierguards surrounded us. One shouted, “Stop!And hands up." <strong>The</strong>y were pointingmachine guns at us. One of them said, "Weknow you're trying to escape to Austria!" Isaid, "No, we're just on the way homenow." We were frisked now from head totoes, our ID's and documents taken, butfortunately they didn't find my hiddenAustrian money, which was sewn into mypants under my belt. Had they found that,we not only would be guilty, but they wouldconfiscate the money. Nonetheless, theyinterrogated us for an hour, threatening totake us to jail. <strong>The</strong>n finally they took usback into the restaurant and two guards satdown with us at a table.By sunrise, most of the guests haddisappeared and so had the musicians.Our conversation and/or interrogation wasdone in Serb-Croatian, since the borderarmy guards were all from other provinces.In turn the Slovenian soldiers were sent toserve the army to their provinces. InSlovenia, we learned Serb-Croatian,including the Cyrillic writing. <strong>The</strong> thirdYugoslav language, the Macedonian, wasan option at schools.Sometime later a new army guard, withsome rank came to our table, took ourdocuments from the two guards, anddismissed them. Once again we wereinterrogated at length with questions suchas "Who do you know in Austria and other

Western countries? Who else is trying toescape with you? How many times beforehave you tried to escape?" Finally, he said,"OK, I'll walk you part-way down themountain, then you must go home. Afterhalf an hour he handed us the documentsand said, "If you try to escape again, I'llpersonally take you directly to prison.'"Well, both of us now were greatly relived,but mad at my school colleague, ”thesquealing pig.” While walking back to thecity of Maribor, we decided not to go home,but instead, ironed out another escapeplan.Photograph of my friends and I beforemy escape. I am seated in the center

Second EscapeWe assumed it would be too risky to tryto cross the border today at the samelocation. So, we went directly to the railwaystation in Maribor. From here, we wouldtake a train heading for Austria, but get offone station before the border at Sentilj,then continue on foot over the mountains.Sitting and recuperating from our 30kilometer walking misadventure at therailway's restaurant and waiting for the 8p.m. train departure, we were beingconstantly vigilant and ready for an instantgetaway, should we be approached bypolice who may have been informed of ourintent. While having dinner, we probablylooked like two rabbits eating carrots out inthe field, always on a lookout for apredator.A well-dressed, middle-aged man with abriefcase walked into the restaurant andcame directly to our table, asking if he mayjoin us. I said, "Yes, of course." Both of uswere apprehensive, but it was too late torun if he was an undercover policeman. Hewasted no time in asking me, "What is yourdate of birth?" I told him, and then hepulled out of his briefcase a sheet of typedpaper and handed to me. It was ahoroscope; I read it and found many thingsvery agreeable about my life. Onequotation struck me most: "Your main goalin life is to go to foreign country." I was nowquite puzzled and thought, what in the hellis he up to? Meanwhile he asked my friendfor his date of birth and handed himanother paper. He too was amazed ofmany agreeable quotations, but no mention

of foreign country. <strong>The</strong>n the man asked usto each pay 50 dinars. After we paid, hegot up and left. I'd heard of horoscopebefore, but never had an opportunity tolearn about it, since under the Communistregime it was, to say the least, disapprovedof and discouraged.At 8 p.m. we boarded a train bound forVienna, Austria. As we were boarding I sawa uniformed man boarding the very frontcar. I assumed it was an immigrationofficer, so I told my friend and we moved tothe very rear car. I thought and hoped hewouldn't have a chance to examinedocuments before our next station, wherewe were going to get off. Our move provedto be prudent and we got off at the stationbefore the border. Wasting no time, weheaded into the mountains, carefullyavoiding people and farmhouses, mainly bywalking across the orchards and vineyards.At one time a huge St. Bernard attackedus. Again, I sprinkled some of my pepper athim, he sneezed and disappeared.By 11 p.m. we arrived at the top of themountain, which I assumed to be near theborder. We laid down on the damp andcold ground in the forest to wait until 2 a.m.for our crossing. We were dead tired fromwalking across muddy fields and ascendingto the top of the mountain, and fell asleepin no time. We woke up at sunrise (noalarm clock). "Now what?" my friend asked.I said, "We'll try to cross the borderregardless of the risk." We walkedcautiously down the mountain looking forany border markings or signs, but no luck.By about 9 a.m. we slowed down, thinking

we must be in Austria by that point. Well,we were now somewhat relieved andbegan walking more casually. After an hourwe walked to the top of the hill, where tomy surprise, looking down below was a bigriver. I assumed it to be the Mura; therewas also a village nearby. Now we weren'tsure at all whether we were still inYugoslavia or in Austria. In just fewminutes our answer came — in a bigdisappointing predicament. We heard loudnoises coming from our left, and lookingdown we saw was a large building with aYugoslav flag on it. <strong>The</strong>re were armyguards lined up and receiving instructionfrom an officer. After a few minutes, theyrapidly — with their riffles — began scalingthe hill toward us. We took off with lightningspeed to circumvent them and the armyguards’ outpost building. As we wererunning they shouted, "Stop or we shoot!"We kept running into a thick forest on veryrocky terrain. A few shots were fired; Icould hear the bullets whistle by. After halfhour of running, we came to the river, dovein, and swam across. Now I was sure wewere in Austria. Looking back we saw theguards coming to the river, so wecontinued running but they didn’t follow us.We sat down and joyfully laughed, wet andexhausted, with sore and blistered feet.We proceeded across the fields until wecame to a stream. We sat down, washedour muddy clothing and shoes, rested foran hour and happily walked barefootacross farm fields and forests, avoiding thepeople. Late in the afternoon we had nochoice but to walk into the village to get

water and food. At the beginning of thevillage, we approached the housecautiously. A lady was working in thegarden. I greeted her; she turned aroundand greeted me with a friendly expression.I asked her if there was a store nearbywhere we could buy drinks and food? Shereplied, "Only in the next village,” thenadded, “Well, please come into my houseand I'll give you water to drink." We eachdrank many glasses, I'm sure she musthave thought, where are these two thirsty'camels' coming from? She looked us upand down and said, "Your feet are full ofblisters and sores, I'll bring you someiodine to disinfect." After she asked me if Iknew how to fertilize and turn the soil in thegarden? I said, "Of course, we arefarmers." She then said, "If you do mygarden, I'll pay you." I said, "We'll be gladto do it." <strong>The</strong>n I asked for the necessarytools. She replied, "First I'll make supper forall of us, then I'll give you the rooms tosleep, and tomorrow morning you can startworking." I asked her if she had a family?“Oh yes, but I live alone now." I was glad tohear that, since a jealous husband orsomebody else may not be so kind to usand even perhaps report us to the police.<strong>The</strong> next morning we began workingand the lady was very generous with mealsand drinks all day long. By nightfall wecompleted the garden work, which wasabout 20 by 30 meters in size. <strong>The</strong> ladycould hardly believe everything we did inone day and thanked us for such a nicework. She then paid us and said, "You'rewelcome to stay the night here." I thanked

her for her kindness and understanding. Ibelieve she knew from where we had justcome, but she never asked us. Early nextmorning, she made a breakfast for us andsandwiches for our journey to the town ofLeibnitz, some 40 kilometers away. Ithanked the 'Grand Lady,' she wished usgood luck, and then we were on the waybarefoot across the fields and forest.Avoiding the villages and people, bysundown we arrived to Leibnitz railwaystation. Inside the station there was apoliceman reading a local newspaper. Wasit his routine? Or was he waiting for us? Iwas sure the Grand Lady didn't report us,but perhaps somebody else? We bought anewspaper and pretended to read whilewaiting for the policeman's move. Myfriend, who didn't speak any German, wasthe problem and concern. I told him,"Should the policeman give us any trouble,we'll make a run along the railway trackstowards the city of Graz (Austria)." I wassure we could outrun the fat policeman whowas over 50 years old and reach ourintended destination.After a while the policeman disappeared.We walked in and while I was buying thetickets, the policeman returned, asking myfriend, "Where are you going?" My friendkept quiet. I turned around and said to thepoliceman, "My friend doesn't hear well andwe're going home to Salzburg (Austria)."<strong>The</strong>n he asked for the documents. We tookoff with lightning speed toward the railroadtracks and ran along them. <strong>The</strong> policemanfollowed us for about a kilometer, and thenhe stopped, realizing he was no match. But

we kept running, and the policeman walkedback to the station. As luck would have it, afreight train was approaching slowly frombehind. We stopped and pretended to beworking along the tracks. <strong>The</strong>n we jumpedon the last wagon, hoping the policemandidn't see us, and also hoping that the trainwould keep on rolling. Soon the train begangaining speed and an hour later we arrivedat the city of Graz. We carefully and slowlysnuck into the station — with our shoes on.We were trying to conceal the pain of oursemi-healed blisters. I discovered that themoney we had would take us to Salzburg.As we were discussing our predicament,we walked through that very busy stationadmiring all those vending machines, whichwe had never seen before. And, while wewere in the photo booth, a middle-agedman stood waiting outside. He must haveheard us talking in Slovenian, because aswe stepped out, he greeted us inSlovenian. I asked him if he lived in Graz?He said, "Yes, for many years." <strong>The</strong>n heinvited us to a restaurant for some drinks,where we confessed to him of our intentionto go to Salzburg Refugee Camp. He wassympathetic and invited us to overnight athis apartment. I was a bit skeptical, butaccepted, with thanks. I boarded atramway, while my friend had a ride on theman’s motorcycle. He lived alone in a onebedroomapartment and made somesandwiches for us. Soon he began makingsome sex remarks and some advances; weboth realized he must be a homosexual.Both of us were appalled and rejectedfurther advances. He then gave up and

gave us two sofas to sleep on. In themorning he made us breakfast and told usto go to Bruck auf der Mur Refugee Campinstead of Salzburg. Assuring us we wouldnot be deported from there, and besides,he knew we had enough money for thetrain to take us there. We agreed, although,we never heard of that camp. In theafternoon we arrived at this town with riverMur running through it, the very same weone swam across on our escape at theborder. I asked several people about theRefugee Camp, but no one had heard of it.Now we knew that the gay man, thescoundrel, had gotten even with us. Wedecided to walk back to the railway station,buy tickets onward, to as far as our moneywould take us, and then walk the rest of thedistance to Salzburg.At an intersection we were approachedby a policeman, who greeted us, thenasked us where we were from. I said,“From Salzburg." <strong>The</strong>n he asked to see ourI.D.s. I told him that we had forgotten themat home. "Oh so," he replied. <strong>The</strong>n heordered us to walk in front of him — andguided us right into the police station. Helocked us into a small cell and thendemanded that we empty our pockets andhand over the contents to him. He andanother officer looked at the Yugoslavdocuments, but didn't return them. Nowthat the cat was out of the bag, I told him ofour desire to report to the Refugee Camp inSalzburg. Later the officer made somephone calls, and then left us in suspensefor hours. Late in the evening I asked forwater and food. About an hour later he

eturned with water and some sandwiches.I asked him, "How long do you intend tokeep us here?" He replied, "Ya, yatomorrow you'll know."<strong>The</strong> next day about noon, we werehandcuffed and without any explanation,taken to a local prison. First they made ustake a shower, and then we were eachgiven a stripped prison robe. We werelocked into a large cell, with four Austrianinmates, some serving terms up to tenyears. <strong>The</strong> inmates were not happy aboutus two — mainly for not having anycigarettes, since neither of us smoked.<strong>The</strong>y were begging the guards for the cigarettebutts.After few days I was able to getinformation on why and how long we weregoing to be locked up. <strong>The</strong> warden said,"Soon you'll be transferred to the LeibnitzRefugee Camp." I said that we wouldprefer the Salzburg Camp. His answer was"It's too far." Well, we were kind of relievedbut disappointed, fearing being deportedfrom that camp, according to the rumors wehad heard back at home.<strong>The</strong> inmates were mostly interested inhearing about life in the Communistcountries, but expressed some displeasureat the refugees and/or immigrants inAustria. We played cards together and Ihad a chance to learn the German Austrianaccent / dialect. A week later the two of uswere handcuffed and taken by police car tothe Leibnitz Refugee Camp. It was locatedon the outskirts of the town, enclosed withhigh wire fence, and had a locked gateentrance. First we were taken to the

Warden / Camp Director's office. Ourdocuments were handed over, then wewere uncuffed and the two policemen left.<strong>The</strong> Director asked us, "What is yourreason for coming to Austria? Did theCommunists send you? Who else camewith you? Where are the Yugoslav armyinstallations? What country would you liketo go to? Do you have any close relativesin Austria or other Western country?” Andmany other similar questions. Afterquestioning, we were taken to one of the10 wooden barracks, allocated a doublebunk bed, a towel with soap, a dish, spoon,knife and fork. <strong>The</strong>n we learned the rules ofthe camp, for example, stay away from thefence; there will be three meals a day,served in the courtyard; wash your owndishes afterward; to leave this camp for anyreason, you'll need a permit from the CampDirector.Most of the 200 or so refugees wereyoung men, with some young women and afew children. Most of them were fromYugoslavia, some from Hungary, othersfrom Bulgaria and Romania. <strong>The</strong> rumorsamong the refugees were that many werebeing deported lately, but a disturbing bit ofinformation was that everyone under age18 would be deported, according to recentregulations. <strong>The</strong> daily life at the camp wasquite jovial, but occasionally, ratherannoying. Sometimes not only arguments,but actual fights occurred mainly betweenthe Croats and Serbs — carrying on the olddisputes and animosity. We, theSlovenians, were trying to keep neutral, butthe Bosnians and Macedonians were not

head for Germany. I asked him,” Whywould you want to escape?" He said, "I'vebeen here for four months and believe I'llbe deported as well." <strong>The</strong> three of usagreed and made a plan to escape thenext evening.<strong>The</strong> next morning at about 9 a.m. thepolice car stopped at the Director's office.<strong>The</strong>n, on the intercom, my friend’s nameand mine were called out, telling us toreport to the office. As soon as we entered,two policemen slapped handcuffs on us,and then drove us out of the camp anddirectly to Leibnitz prison. This time it didn'ttake a genius to figure out who was the“Squealing Pig.” When I asked thepolicemen, "Why did you bring us toprison?" His answer was "Yaaa, soon you'llfind out." <strong>The</strong> prison warden told us toundress totally, and then the doctor camein and examined us. Unfortunately, wepassed the physical test. After a shower,we were given the prison's robe, then takento a large cell, which was shared with someten other inmates who were all Austrian.Once again, we were asked for cigarettesand disappointed them. When I asked theWarden, "Why and how long are we to belocked up?" he said, "Soon you'll find out."It was always his answer. So for the nexttwo weeks, I had a chance to improve myGerman, play cards, and every second daywas an hour of courtyard walk (in a lineformation and no talking).After two weeks and a day the two of uswere handcuffed and led to a waiting van,where three other prisoners were sittingalso handcuffed with two policemen. And

without any explanation, we were driven toSentilj, on the Slovenian Yugoslav border.On our arrival, the Austrian police handedour documents over to the Yugoslav police,who re-handcuffed us with the Yugoslavbrand. I asked the policeman, "Where areyou taking us?" He said, "No talking isallowed." Our three companion prisonerswere Bosnians. In an hour we arrived toMaribor's Court House prison.Here I was locked up in very small cell,as for the rest I had no idea. <strong>The</strong> next day Iwas interrogated, which revealed the otherside of the coin. I was asked, "Who wasyour guide and where did you cross theborder?” “How many times before have youescaped?” “Who else was with you?”“Which places in Austria have you seen?”“Where are the army installations?” Andmore. Within ten days I was interrogatedthree times and always by a differentofficers. I asked about my friend's fateseveral times, but the answer was alwaysthe same: "He is here somewhere." Herethe daily routine was reading books, andtwice a week a courtyard walk —and notalking to other prisoners. Three meagermeals a day, served in the cell, by aprisoner, accompanied by a guard.

On the tenth day I was set free andthough I was very happy, I had no moneyat all. Besides, I didn't want to go home. Iwasn't willing to reveal my failure to myfriends, and especially not to my parents.But I was curious to find out whether myfriend Josef had also been released. So Iwalked two hours to my village, Dobrovce. Ifirst went to my friend's house. His motherwas happy to hear that he was alive andwell but said he hadn't come home yet. Ipresumed he was still in jail. I asked hisfamily not to tell anybody of ourmisadventure. But they told me there wererumors we both had escaped. I thoughtsooner or later the cat would be out of thebag, so I went home. My parents werefurious, but my brothers and sisters wereglad to see me. I asked my father to lendme some money so I could find ablacksmith job in the city. He said, "<strong>The</strong>reis plenty of work at home,” and sent me outto the field to work. Well, it was better thanlistening to ridicule of my parents at home.Later I worked part-time on a collectivefarm where at least I was paid, howeverlittle. A few days later my friend camehome from prison. He too was skepticalabout coming home to face his defeat.In a few weeks time I was able to buymuch-needed clothes and shoes. Myyounger brother was the one who wasmost chased around the courtyard byFather for any infraction he was known todo. Sometimes he would chase him withlethal home tools. Soon my youngerbrother persuaded me to escape to Austriaagain. It would be his second escape as

well. I consulted my friend Josef about ournext escape, but he was still trying to forgetthe ordeal that we'd endured and decidednot to go. We collected enough money togo by train all the way to Germany.Unfortunately, I was unable to buy Austrianand German money. Nonetheless wedecided to go within a week. Beforeleaving, I went to see my Aunt Angela inthe village of Pesnica. She was alwaysfond of me, since apparently I was the onlyone in our family who resembled mymother and her side of the family.Freedom is the right to live as wewishEpictetus

Third EscapeThrough my Aunt Angela, I found out thatbesides our uncle in Graz, Austria, we alsohad a cousin who lived just 20 kilometersacross the border. This, coincidentally,was the region where my friend and I werecaught at the border. <strong>The</strong>n my aunt said,"Don't count on him or your uncle too muchfor help.” I trusted my aunt, since she too atage 16 escaped to Vienna. She worked fora while, but her father made her come backbecause she was under age. Thishappened in the year 1920, after the FirstWorld War, when so many Europeans hadimmigrated to the New World of North andSouth America.My brother and I gathered enoughmoney for the train fare to take us acrossAustria to Germany. Unfortunately I hadbeen unable to change dinars into Austrianand German currencies. <strong>The</strong> solution forthis was to cross the border near my firstfailed attempt, and then reach my cousin,who would hopefully change our money.This time I made sure we had cotton sockswith good, comfortable shoes and lots ofhot and black pepper for snarling dogs.We discreetly departed home atsundown, walking through Maribor andcontinued on the now-familiar roads intothe mountains. Late in the evening it beganto rain with thunder and lightning. <strong>The</strong>dusty mountain road turned to slip-slidingmud. But that was an advantage: fewerpeople to meet or hide from, includingthose nasty farm dogs. Once we had tohide and wait in the forest to let by a slow,

oxen-pulled wagon that had a dog, and dueto rain the dog didn't see or sniff us out.At 10 p.m. we arrived at the restaurantwhere I had been apprehended with myfriend during our first escape. This time wecarefully circumvented the restaurant, andthen found a place to hide and wait until 2a.m. to cross the border. This time I madesure I stayed awake. <strong>The</strong> rain and thundersoon ended. After midnight, we heardstrange, loud noises coming from the valleybelow. We tried to figure out what wasgoing on because it sounded likesomebody was in pain or being tortured.We were thinking perhaps it was the borderand that the border guards were trying theold-fashioned way to obtain a confessionfrom an escapee. After an hour, the noisesdiminished. We waited a bit longer and,then started on the muddy, slippery, rockyterrain. Due to rain it made walking quieterthan on a dry ground; there was nocrackling of dry tree branches and leaves.<strong>The</strong> flashlight we had brought became veryhandy for observing our heading on thatvery dark night. We were looking for thegreen-colored moss, which is on the northside of the trees, and usually near theground.We kept steady, slip-sliding pace on therugged terrain until sunrise. As we walkedthrough a vineyard, I noticed thegrapevines were strung on wires there,rather than attached to wooden sticks, aswas practiced in Slovenia. We were greatlyrelieved and our clothes nearly dry from therain. In a while we spotted a farmhouse,and approached it very carefully. I asked

my brother to hide in the bushes. He wasn'tugly, but something much worse: he didn'tspeak any German, should somebody seehim and ask questions. I then snuck quietlyto the front of the house; a man came outwith his German Shepard and proceededto the barn. That gave me had a chance tonote the house plate. Happily, it was inAustrian. My brother and I proceededtoward our cousin’s village, passingthrough vineyards, orchards, and forests.We spotted a family working in the fieldsand approached them to ask where andhow far it was to the village of Leutchach.We told them that our cousin wasexpecting us. <strong>The</strong> lady said, "Yes, it’sabout 10 kilometers and you may walk on afarm road.” We continued, but stuck tocrossing the fields for safety. By 2 p.m. wearrived at the village and found the houseaccording to my aunt's description.Outside the house a young fellow wasworking. We greeted him and explainedwho we were. I asked him his name. Hetold me and then I said, "We're cousins."He replied, "Yaa ah so." He didn't invite usinto the house, but continued with his work.I then said, "We would greatly appreciate ifyou would exchange our money; the dinarsto schillings?" "Well, I don't have anymoney," he replied. He then disappearedbehind the house, leaving us standingthere for an hour. We decided to give up onour cousin and continued our journeyacross the fields.In an hour we came to a village where Iwent to a general store to buy something toeat and drink. <strong>The</strong> lady said,” I don't accept

dinars.” I then offered at half its rate, whichshe accepted. We proceeded on a dirt roadtoward the town of Leibnitz some 25kilometers ahead. After half an hour ofwalking, we spotted a policeman with abicycle standing under a tree. Wedisappeared into a cornfield that was waisthigh, laid down, and waited for him todisappear. But he came toward us, got offthe bike, pulled out his pistol, and shouted,"Come out with your hands up!"We thought about running, but decidedto talk to him instead. I explained that wehad visited our cousin, but live in Graz.Because we had forgotten to take alongour I.D.s we were trying to avoid the police.He said, "Ah so," then slapped handcuffson us and told us to walk ahead of him tothe next village as he directed us into thepolice station. <strong>The</strong>re, another policemantook everything out of our pockets andlocked us in a small cell.Some 40 years later, in 200I, I wasinvited by my good cousin in Slovenia to aparty to celebrate the meeting of all ourcousins on Mother's side. <strong>The</strong> partyincluded both the cousins from Leutchachand Graz, whom I'd visited and whoignored me. During the party bothpersonally apologized to me for theirunfriendliness and arrogance.<strong>The</strong>y soon made phone calls, and laterwe were escorted into the office and leftalone with the door closed. We heard twomen talking in the next room, so I said tomy brother, "Let's make a run," He agreed,so I opened the door. <strong>The</strong>re was nobodyaround, so we quietly tiptoed through the

hallway. But as we came out, hell, therewas the policeman talking to someone. Heshouted,” Stop!“ and with his pistol in hand,he placed us back into the cell. Later byevening they put two small cots in our cellwith a sandwich and water for each of us.<strong>The</strong> next day at noon, they handcuffedus and put us in a police car. Whatever Iasked the two policemen they ignored meentirely. In just twenty minutes, we wereback to the now-familiar Sentilj Yugoslavborder. Again we were handed over to theYugoslav police, who re-handcuffed us withthe Yugoslav brand and put us into awaiting van with four other misfortunateyoung men. In half an hour we were backin Maribor. But this time they took us into awomen's prison and locked us all into a cellthat was already full of young men. It wasso crowded, that we could only standupright. Many of the prisoners were fromCroatia; others were from Serbia, Bosnia,or Macedonia.In about an hour my brother and I werecalled for interrogation. <strong>The</strong> questions werenow very similar, but unfortunately, theinterviewer looked into a large book, andsaid to me, "Well, you have escapedbefore, and how many times?" I said,”Once," Fortunately for my brother, he wasnot in the book. It was actually his secondtime. <strong>The</strong>n after an hour of grilling, we weretaken to separate cells. I was sharing withanother inmate, who was very edgy, noisy,and angry. Because he had already spentmany days in the cell alone, he demandedto be released. <strong>The</strong> Warden showed up,took him out, and said, “Now, you

miserable, you will stay in a basementsolitary dungeon.” That was the last I sawof him. Within a week I was interrogatedseveral times. One morning I washandcuffed and taken to the office, wheretwo Croatian fellows were handcuffedtogether. <strong>The</strong> policeman told us to walk infront of him at all times, and no tricks ortalking. We were walking on a busy mainstreet, as "partisans." I was embarrassedand kept my head down in hopes thatnobody would recognize me. In fifteenminutes we ended up at a railway stationand boarded a train for Zagreb, Croatia.Along the way I was unable to find out fromthe policeman where he was taking us.After about two hours we arrived at thesmall town of Brestanica (formerlyReichenburg), which is located somekilometers before the Croatian border. Atthis point we got off and walked on awinding dirt road all the way to the top of apine-forested hill. We were led into a bigcastle, where we were intercepted byuniformed guards, then walked through acourtyard full of prisoners (mostly youngmen, but also some women and children).Next we were taken to the second floor andinto a large room to share with maybe 15other inmates. We were given a blanket,and told to sleep on the wooden raisedfloor, which sloped slightly down from thewall. It took me days to get any sleep onthe hard floor. I also had to listen to theother inmates’ complaining or telling theirescape adventures. Some of them hadbeen caught before; others had beendeported from Austria, or Italy.

We were all political prisoners, and fromall Yugoslav provinces; Slovenia, Croatia,Serbia, Bosnia Hercegovina, Crna Gora,and Macedonia. Here too, the friction wasobvious, mainly among the Croatiansand Serbs, but the guards were mostlyCroatians. I was interrogated almost dailyby different officers, and in addition to theusual questions they were trying to learnwhat I had told the Austrians about theYugoslav's army; they also wanted to knowthe locations of their armies, etc. By mostaccounts, as a second timer I was facingup to six months of precious summer timein jail. After few days I was moved to abetter accommodation, a room with singlebeds sharing with some 20 inmates, andwith a window overlooking the town below.A day later one of the interrogators came toMy prison – Castle Reichenberg-Slovaniaour room and said, "As of today, Rafaelwill be your room orderly, and you all mustcooperate, with him to maintain the prison'srules and regulations." A Sloveniancellmate asked me to help him to work in aboiler room, mainly to steam/disinfectclothing of the incoming prisoners while

they were taking showers. He confided inme and confessed that not only would Ihave more and better food, but I could alsomake some hush money. Some prisonershad but just one good-quality suit on themand would pay him money not to steamand ruin their clothes. Due to the risk, hewould accept the money; it would at leastbe useful to buy extra food. Everybodycomplained about the prison’s meagerfood.Of course, there was another exitingadvantage: while the women wereshowering, we had a chance to see themnude, which my good friend cleverlyinvented a reason for our presence.Almost daily we had new prisonerscoming while others were leaving. <strong>The</strong>daily life was usually in the castle'senclosed courtyard, and on the average,there were some hundred prisonersmingling and exchanging stories. Thosewho were too noisy or complaining wereoften beaten up by the guards. One day afellow refused to chop wood for the furnaceand was clobbered, then pushed down thestairway. He tumbled into the basement,merely because he told them he’d neverhandled an axe before, and so for sometime the poor fellow was unable to sitdown, or walk about. Since it was done inthe courtyard in front of most prisoners, italmost sparked a riot.After two weeks, I was no longer calledin for the interrogations, and daily life wastaken up by few hours of work, seeing thatour large room was neat and clean at alltimes, arguments or disputes to be kept

under moderation, and cards were playedwithout money bets. Unfortunately therewere hardly any books to read. <strong>The</strong> two ofus had food served in a boiler room; we gotwhatever the guards were served, whichwas usually some meat, and vegetables.As for the rest of prisoners, it was a rareluxury.Reichenburg Castle, the prison and thevillage had a rich historical past; Remainshad been preserved from the prehistoricera as well as from the time of the RomanEmpire. <strong>The</strong> Roman road "Neviodunum-Celia” went through this area. Brestanica,the old stone bridge across river Sava,bears witness to that. <strong>The</strong> castle may havebeen built by year 838, but was firstmentioned in 895 when King Amolf gavepossession to Lord Valtun, thus it is the firstmedieval castle in Slovenia. It wasdemolished and rebuilt between 1131and1147 by the Bishop of Salzburg. <strong>The</strong>family Reichenburg owned the Castle from1410 to 1570. After that there were manyowners, until Trappist Monks bought it fromFrance in the 1880s, who transformed it toa monastery. <strong>The</strong>re were strict rules for themonks: absolute silence, with a principle,“What you need in your life you shouldmake yourself." In 1941 the Germansexiled the Trappists and the castle wastransformed into a transit camp. Some45,000 Slovenians went through this camp,some tortured or killed, and others sent intoexile. After the war the Trappists returned,and later in 1947 the order of Trappists wasdisbanded. <strong>The</strong>n it became a prison whereI was locked in for two months in 1958.

<strong>The</strong>re were stories that many newly bornbabies had been found buried around thecastle after the Trappists left. In 1968 thiscastle was altered into today's museume.g., the interrogation room is now aRomanesque chapel.On my visits in 1999 and 2002, I had topay an entry fee, but at half price, after Itold the kind, sympathetic young lady of myimprisonment here.In mid-August, I and some 20 otherSlovenian prisoners were loaded onto acavernous, covered truck, and driven forsome two hours until we made a stop atsome village restaurant where the guardstook refreshment. One of our eldest, a oneleggedprisoner, asked for water. <strong>The</strong>guard hit him twice with the club. With tearsin his eyes, he said to the guard, “I lost myleg during the war fighting against Nazisbefore you were born.“ It was a hotsummer day and we were all dying of thirstbut nobody dared to ask for water afterthat. We continued for another hour. Wemade another stop; I think it was in the cityof Celje. We were all guessing since wecould not see out at all. Here some 15prisoners were taken off the truck. Nowonly five of us were transferred into a smallvan without windows or seats. By sundownwe were on our way — thirsty, hot, andhungry, we arrived what we assumed to beMaribor. I thought it was Partizanska Road.Here they stopped; the guards got out ofthe van and disappeared. We were left forat least an hour in a steamy hot van,dehydrated, airless and suffocating. We allconcluded that, for all they cared we might

e dead by the time they return. Wemutually agreed to brace ourselves againstthe rear door and force the door to openand escape, with a plan to cross the borderto Austria. Just as we were ready to pushthe guards returned; we all felt stupid forwaiting too long. A few minutes later wearrived at the city's courthouse and wereindividually led into separate jail cells. I wasput in a cell to share with an elderly inmatewho was awaiting his trial for allegedlydefrauding the company as a director whileon business in Germany. <strong>The</strong> cell had twosmall beds, a latrine, and a small windowclose to the ceiling, but we were notallowed to be seen looking through it. <strong>The</strong>meager food was served to our cell byother inmates escorted by a guard. FortunatelyI was able to buy extra food withthe money I made by not steaming someclothes at the previous jail. My inmate'swife brought weekly some food to herhusband, and often he would share it withme. Here we had books to read, cards andchess to play, plus a half hour walk in thecourtyard every second day. I wroteseveral letters to my younger brother to findout whether he was still in jail or had beenfreed and was running loose, but to noavail.Weeks went by and none of us wascalled for a trial, apparently due to the factthat most judges were on summer vacation.I began thinking; why not create aversion of the story for my trial. I could saythat my brother and I were looking for a jobnear the border where someone had toldme of a blacksmith’s shop that would hire

us. While looking we inadvertently crossedthe border, where we asked the police tobe allowed to return. My learned, kindinmate thought it to be a good idea, andsaid, "<strong>The</strong> judge may buy it, andyou will be free." My inmate was a politeman; every time he would sit down on thelatrine he covered his face with a towel.When I asked him, "Why do you do that?"he said, “I don't want you to see myembarrassing face." We had our own newsreports on daily bases whatever was goingon in the prison: by gently knocking on thewall. Every knock meant a letter, forexample one knock was letter A, threeknocks letter C, followed by a pause, etc. Isoon learned all of the alphabet'scorresponding numbers by heart. One day Ilearned one of my village friends was alsoserving time for his attempted escape toAustria. Soon, to my surprise, he wasserving me food, escorted by a guard. <strong>The</strong>next day, he placed a note under my plate,and told me that my brother was free andworking now. After a while he no longershowed up serving food. I later saw him inthe courtyard with shaven, shiny head.Apparently he tried to escape, and that wasthe usual punishment for it.In mid-September I was finally slated fortrial, and since I was still 17 and under age,they gave me a defense lawyer after aconsultation. He skeptically accepted myversion, but said, “Your brother and yourfather will be at your trial as well." Thatworried me a bit, since my brother didn'tknow of my new version of our story. I washoping that I would be the first to testify. As

for father, he knew nothing about the case,so no problem here.It was a small courtroom with a middleagedjudge accompanied on either side bya lady and a stenographer. <strong>The</strong>re was myfather and brother; I was seated beside mylawyer. <strong>The</strong> judge asked me to explain mystory. <strong>The</strong>n my brother was asked ifeverything I had said was true. My brothercorroborated, but on cross-examinationsome discrepancies were noted, at whichtime I was allowed to reprove the errors.<strong>The</strong>n the judge asked me, "Who did all thework at home, and the farming?" I said, "I,my brothers, and sisters." <strong>The</strong>n he askedme how many sets of clothing and shoesdid I have?" I said, "Only what I have onme, and a set of work clothes, which is athome." "And how many pairs of shoes?”the judge asked. I said, "Only the ones Ihave on." I added, "We worked at home, aswell as in the fields barefoot unless therewas snow on the ground.” <strong>The</strong> judge wasinterrupted by my father, who said. “<strong>The</strong>reason he and other children are leavinghome or escaping is that they are lazy anddon't want to work.” <strong>The</strong>n the judge askedhim, “Who does the work now?" Fathersaid the two youngest sons. "And how oldare they?" the judge asked. "One is ten,and the other six.” That somewhatinfuriated the judge, who said, ”I will fromnow on, hear no criticism or any morecomments from you.” <strong>The</strong> judge thenconferred quietly with both ladies.After few minutes the judge asked me,"If you were free today, where would yougo?" I said, “To my aunt, and start looking

for a job." He asked me to stand up, andsaid, "You are free as of now." I wasrelieved, and happy. <strong>The</strong>n, the judge saidwith a somewhat whimsical smile, "I dosuggest, not to look for a job near theborder next time, for there is no blacksmithin that area anyway."As I stepped outside the courthouse Ifelt like a million, even though I had not adime on me. <strong>The</strong>re across the street wasparked the horse and buggy with my fatherand stepmother on board. When theynoticed me, father asked me to jump onand come home. I declined, and told themgoodbye. <strong>The</strong>y left and I began walking toPesnica to see my aunt, which is some 10kilometers from Maribor.This was the last time I saw mystepmother. In 1969 she committedsuicide. And my father, I didn't see him for12 years, until 1970. <strong>The</strong>n I drove himaround by car to see places, but his stem,domineering attitude never changed. In1986 he died due to an accident. May theyrest in peace.My Aunt Angela and uncle were veryglad to see me, and said, “You arewelcome to stay here, but you're ratherskinny and pale." My uncle was nowretired. Years ago he had had his ownblacksmith's shop before the Communistregime, and after worked for a statecompany. With his help and influence, I gotthe job within a week. Aunt Angela alsohas had a restaurant/bar; both businesseswere located at their home, but now shehad the fanners milk collection business,besides some five hectares of farmland,

which I was glad to help with after mycompany's work and on the weekends.<strong>The</strong> company was in Maribormanufacturing, repairing train locomotives,wagons, etc. As a beginner I was given thedirtiest and noisiest job, riveting with an airhammer on the inside of the meter-and-ahalf-diameterboiler drums. Within few daysI lost my hearing completely. My uncle saidit is not permanent, as he too hadexperienced the same when he workedthere. Of course he now was hard ofhearing. So that was not exactly anyconsolation. After some weeks I slowlybegan to recuperate my hearing. (Today Idon't hear, only, what I don't want to.)After a few months I bought my first newbicycle (to commute to work), and somebadly needed clothing. Under theCommunist regime the pay was low, butsimple — no deductions of any sorts, nopapers or files to maintain. Since the twobusinesses were state-owned, socialsecurity, medical, education, etc., were allfree of charge.Once again I had to attend militiatraining, one afternoon a week. I had adreary army uniform that I disliked most,especially after my experiences with boththe border and the prison guards. Onceagain I was fined for failing to attendoccasionally, with my made-up excuse ofhaving to work overtime. When the finewas mailed to the company's manager, Iexplained, and got hell for it. But the statecompany paid for me. Since my overtimejob was operating a crane, which nobodyelse was trained for.

My stay at aunt Angela’s place was verypleasant; my uncle, their daughter, son andhis wife aII treated me very well. My aunt,the sister of my mother, often said. "lf yourfather was not so work-demanding," ormore reasonable, “your poor mother wouldstill be alive." May she rest in peace.In the spring of 1959 I'd received thedreaded army draft notice to begin servinglater that year, in September, for the periodof two years in the province of Croatia.Besides army training, I would be workingin a blacksmith's shop, maintaining armyvehicles, shoeing horses, etc. Escape wason my mind again; there was no way I'dwaste two years of prime life in some stinkybarracks, obeying strict orders that wereusually unreasonable, if not stupid(according to the accounts of others whohad already served). On top of that werethe overzealous, and pompous officers. Notto mention the principal of the armytraining: basically, to kill people.Fortunately I had a few months to planthe escape, but with army draft notice in myhand, should my fourth escape (third byrecords) be unsuccessful, it meant up totwo years in prison, then a direct escort intothe army.Who speaks of liberty while thehuman mind is in chains?

Fourth EscapeI told my brother of my predicament andintentions. He was not only was ready toescape again, but also said, "One of ourrelatives' wants to come with us." I wasskeptical, but agreed. Meanwhile my aunt'sgood old friend, who was of retirement age,had lived and worked in Austria for manyyears. He came back to Yugoslavia, butwas denied the passport to return. He washappy to hear of my escape, and asked meto take him along. His pension was due inAustria, he spoke good German, and hehad the typical Austrian green clothes, anda hat with a feather. "Well, this would be anadvantage to all of you," my auntconcluded. My preoccupation was of hisage, his heavy pipe smoking, with frequentcoughing, which could give us up at theborder, and also if the guards startedchasing us in the rugged mountain terrain.But I accepted. And the plan was in motion.Except for one dilemma: my beautifulgirlfriend, who had repeatedly asked me totake her along should I ever escape again.She was only 16 years old, and her familywas good friends with my Aunt Angela. Ipondered this for a week, wondering whatto do. Finally, I asked my aunt for heropinion. She too had no easy answer,since she was also 16 when she escaped,and her father made her come back, due toher age. Above all she was the onlydaughter. We both came to conclusion thatI should not tell or take my girlfriend, butinstead, should I be successful, bring hersometime later to join me, wherever,

whenever, and however possible.This time I managed to change somemoney into Austrian schillings and Germanmarks. I took three days’ vacation from myjob. Our plan was to go to Germany, exceptfor the older friend, who would say goodbyeto us in Austria.On a sunny mid-April day we all met atnow-usual meeting place, Hotel Orel inMaribor. After a good, good-bye lunch, thefour of us started our walking mission intothe mountains on that old, familiar road tothe border. On my recommendation we allhad money well hidden/sewn into ourpants, good shoes, a flashlight, and blackpepper powder.Our walking was slower this time due toour old friend, who looked slightly flashywith his Austrian all green outfit. As usualwe had to do some hiding and waitingalong the way, not only from people butalso from nasty barking farm dogs.By about midnight we were at theborder, sat down, and waited two hours tocross. Because there were four of us, itwas hard not to make noise in the forest.By dawn, somehow the others felt I wasguiding them into too westerly of adirection, and persuaded me to head forthe beautiful valley ahead of us to the left.In about an hour we reached the valley,which had a stream and a farmhouse I toldthem to wait, hidden, while I investigatedwhether we were in Austria. I crawled everso carefully along the fence to the front ofthe house. I was shocked to see thehouse's nameplate in Slovenian. I crawledback to tell them the bad news. <strong>The</strong>y were

all very disappointed. I had believed thatwe were already in Austria, before myfriends were fooled by the appealing, easyto-reach green valley. Now what?Continue? Hide and wait till the nextmorning? Our old friend confessed that hewas too tired to continue at that point. Andthe nagging, spineless relative was alsotoo tired, and too hungry, to continue. Isaid, “Fine, we do have something veryessential here: the drinking water from thecreek." As for finding any food on a farm orin the fields in April, that would be amiracle; it was at least a month too early inthe year.It occurred to me we should circumventthe farmhouse, and instead walk somedistance down along the creek. In about 15minutes we reached the road and I realizedit was the road we came up on. We found agood hiding place on a hill with a good viewof the road should somebody be passingby, or looking for us. By noon our spinelessrelative insisted on going back, and buyingsandwiches for everybody at a restaurantthat was at least some 5 kilometers away.He promised to be back before 5 p.m. Ithought maybe he actually wanted toabandon the escape, and simply go home.I said, "OK, but, if for any reason you aren'tback by nightfall, we will assumesomething went wrong: either you werecaught by border guards, the police, or yousimply went home." He said, "Don't worry, Iwill be back."We sat drinking plenty of creek water,after discovering it was clean and safebecause we had no ill effects after the

initial two hours. Seeing several peoplepassing by on the road, I decided weshould not wait there, but relocate to theother side of the creek on a hill, whichwould give us a good view of our presentlocation should the relative be caught andtell them of our whereabouts. That way wewould have a chance to escape.By 5:30 p.m. we spotted a policemanwith a bike accompanied by two other mencoming up the road. We concluded that ourrelative had been caught and spilled thebeans. <strong>The</strong> three of us decided that it wastoo risky at that point to cross the border;instead, we would return home. Should thepolice be looking for us at our homes, wecould simply deny our venture. And in fewdays, we would try again, at a differentregion, and without our relativeWe were running across the mountainstoward Maribor on new terrain, trying toavoid the upcoming road. It took us untilmidnight to reach Maribor, and I felt sorryfor our older friend, who was beat andwalking sideways like a crab. Since it wasafter midnight, we had no choice but tocontinue walking another 12 kilometers tomake it home. <strong>The</strong> same was true for mybrother but he was going in a differentdirection.<strong>The</strong> two of us arrived home at 4 a.m. Myaunt opened the door with an expression ofdisbelief and surprise. She said, “My God,you two must have been through hell." Sheinvited us in, and the first thing she broughtus was iodine for our scrapes and bruises.<strong>The</strong>n we made us a good breakfast. Iasked her if any police had come asking for

us. She said, “No." We felt semi-relieved,but realized they may show up at any timeyet.Our old friend was licking his woundsand recuperating until late afternoon beforehe was able to drag himself home, whichwas only a kilometer away. And I waswaiting for my brother to show up and letme know what had happened to ourrelative (since he lived in a nearby village,and as I'd asked him to do before ourdeparture at midnight in Maribor).<strong>The</strong> next day I visited my old friend whostill recuperating and said, "I don't think I'llbe ready for the next escape at least foranother week." I agreed to wait.My brother still hadn’t show up, whichworried me a bit. I wondered what mighthave happened to either of them. On theother hand, my brother was not exactlymost reliable person with regard to keepinghis promises. I decided to go back to work,pretending as if nothing happened.Nobody but my aunt knew of ourmisadventure. After work I went to see mybrother, who said, ”No police visited yet,and as soon as I find our relative I willinform you." And the he added, “Let’s waitfew weeks before we make anotherescape."

Fifth EscapeTo my surprise, I'd received a letter fromGermany; it was from my village friendwhom I'd last seen in Maribor's prison withhis shaven, shiny head some sevenmonths before. He wrote, "I escaped fromMaribor's prison soon after you werereleased, and later escaped throughAustria all the way to Germany, and ampresently in a Nuremberg refugee campawaiting the asylum papers." Andcontinued, "Not only are you my goodfriend, but also as misfortunate as I was intrying to come to Germany. For this reasonI and my friend here, whom you also knowfrom the next village of ours, have decidedto come and escort you all the way to here.<strong>The</strong> only thing that we need on arrival isour travel expense money, about 15,000dinars."I was very happy to hear that. Andimmediately wrote back, "I'm very pleasedto have such good friend and happy to seeyou finally succeeded. But I think it wouldbe much too risky for the two of you toreturn. But indeed I would appreciate it ifyou tell, or advise me of, where and howdid you make it.”A week later he wrote back, saying,"Rafael, don't worry about us, we're comingto pick you up within few days, be ready."Meanwhile my brother wrote me a letterfrom Canada informing me of the twofriends who would help me escape toGermany. I was a bit uneasy about seeingspecifics in a letter, since it was notuncommon for the post office to open and

ead foreign mail, especially with my pastrecord of escapes.I informed my younger brother, who said,“Don’t leave without me." I said, “OK, beready, but do not tell our spinelessrelative." I'd informed my older friend whowas still in recuperation mode and whowould only go as far as Austria. He told me,"I may after all get pension here, but I needto wait." I agreed, and thought in this case,it would be best for him to stay.<strong>The</strong> only other person I'd confided inabout my plan was my Aunt Angela. AgainI did not mention it to my girlfriend, after allmy friends would probably not accept theidea of her coming along.One early morning during the first weekof May there was a knock on a door just asI was ready to go to work. To my bigsurprise, the two friends from the refugeecamp stood there. <strong>The</strong>y looked cheerful,but obviously exhausted. I invited them in,made a good breakfast for them, and toldthem to rest, and stay in confidence in ourhouse as long as they wanted. I said “I'll dowhatever is necessary outside this housefor you to get in touch with your family,friends, or business. Since it's unsafe, andrisky for either one of you to ventureanywhere should someone recognize you,spread the news and/or report you." <strong>The</strong>yappreciated my gesture, but told me "Wehave some important matters to do, andonly we can do them. Besides, we do wantto visit our families before heading back toGermany." I was trying to persuade them,at least not to return to their villages, sinceeverybody there knew them personally. It

was to no avail, and they told me again notto worry. <strong>The</strong>n they asked me, "Can youget us two bicycles, and the 15,000 dinarsfor our expenses, so that we can buysomething?" I gave them the money (mysix months’ wages) and borrowed twobikes for them. I asked my company for twodays’ leave by pretending I had to attendthe funeral of a close relative.<strong>The</strong> next morning we were off, cyclingthrough Maribor with no problems. But justas we were on the other side of the city, alady approached us on a bicycle, and myfriend said, “It’s my wife!" She recognizedhim and stopped, got off the bike, andangrily said, "What the hell are you doinghere?" He was perplexed, anduncomfortable, and all of us were worriedas we stepped off the bikes. He said, "Icame to see my children." From across thebusy street, she continued sayingsomething about the children. She then goton back on the bike and left. And so did we— in the opposite direction.Once again I asked my friends not to goon, but instead to let me make thearrangements so they could see theirfamilies and friends." Both said, “We’ll becareful; after all, we're experts in hide andseek." In few minutes we came to anintersection and agreed that we all wouldreturn to my aunt's house by nightfall. I left,taking a road to where my brother waspresently working with our relatives on afarm, to inform him of our escape plan intwo days’ time while my friends continuedwith their families. My brother was ecstaticto hear the news, and said, "I'll be ready."

As I left, few blocks down the road at maincrossroads were two police cars in front ofa restaurant/tavern and three policementalking to some local people. I thought itwas very unusual, so I walked into therestaurant to find out what was going on.Inside was another policeman talking to theowner. I sat down and ordered a drinkhopes of hearing whatever was knocking. Ifinally heard the policeman say, “If you seethe two fellows, make sure you call me."He left, and I asked the owner (whom Iknew personally, but I think he didn'trecognize me), "Who are they looking for?"He said, “Two fellows, one from this village,and the other from Dobrovce." <strong>The</strong>n Iasked him, "What happened?” "Well, theyare trying to escape across the border."Now I was sure it was about my friends,and maybe me, and my brother. I rushedback to inform my brother. Meanwhile Icame up with a scheme. For me to go andinvestigate in our village about my friendswas now too suspicious, and risky, due tomy direct involvement. My brother agreedand was glad to help, since so far he wasnot suspected. Besides our friend'syounger brother was his best friend. Beforewe parted, I told him I would wait for hisnews at the nearby village, Miklavz, in therestaurant Lipa.At 9 p.m. two policemen came into therestaurant. <strong>The</strong>y looked over the fewguests, including me (reading anewspaper). <strong>The</strong>y sat down, had a drink,and left — but the remained standingoutside for about an hour, as if they werewaiting for somebody. <strong>The</strong>n they left. By

11:30 p.m. my brother had shown up,obviously nervous and worried. He said,"<strong>The</strong> friend's house was surrounded withmany policemen, with guns, and nobodywas allowed in or out, but finally my bestfriend made it out." And he told me, "Soonafter you parted in Maribor the policebegan chasing them into the forest. Manyshots were fired. It's when the other friendfell, while my friend kept cycling and madeit home. In just 15 minutes policesurrounded his house, but he escapedthrough the back window, and made it intothe forest. He is waiting for me there, tobring him the bicycle as soon as the policeare gone." And he told me, “You shouldmeet him after midnight at the lakeMiklavz." I said to my brother, "We bettersplit. You go straight home and cometomorrow to my place, but make surenobody follows you." And I was thencarefully on my way to meet my friend atthe lake.I waited until 1 a.m. when I heardsomebody slowly coming through thebushes. He whispered, "Are you alone?""Yes," I said. <strong>The</strong>n I gave him sandwichesand a drink I had bought for him in therestaurant. He said, “When the policechased us, many shots were fired. Ourfriend fell, and if I had stopped, I surelywouldn't be here now." I asked him, "Doyou think he just fell, or was he hit by abullet?" "I think he was hit," he answered.I thought it best for us to go to my placein Pesnica, hoping that our captured friendhadn’t told the police about me. We had tocross the River Drava on a bridge. I

thought the two bridges in Maribor might beguarded by that point, so we decided tocross over a bridge in Duplek about 3kilometers away, on the farm roads,through the fields, and along the RiverDrava. <strong>The</strong>reafter, we would follow alongthe river again and then onto a countryroad that would lead us to Pesnica. Thatway allowed us to avoid the otherwiseeasier and more familiar way throughMaribor.We proceeded partly walking and cyclingon a muddy field road, my friend obviouslytired, strained, and worried. Before wearrived to the bridge, I said, "I'll cross thebridge first, while you hide. If I'm not back itmeans the police are guarding or I'm introuble, in which case, go along the river.After 8 kilometers you will get to Maribor'srailway bridge. Make sure no train is tryingto muscle across at the same time,because it is too narrow for both of you.<strong>The</strong>n try to make it to my place."I crossed the bridge and suddenly apoliceman appeared and stopped me. Heasked,"Your name? And where're youcoming from?" I told him my name, andsaid I was going home from my eveningwork shift. <strong>The</strong>n he asked for my I.D.; helooked it over and then let me go. Now Iknew it would be too risky to go back. So Icycled on for a few minutes then turnedonto a farm’s dirt road and made it back tothe river to see if the police woulddisappear. At the same time I was trying tolisten should my friend make a move on theopposite bank, as it was too dark to seeanybody some 100 meters across the river.

I sat for some 15 minutes, it was all deadquiet except for the river's gentle waterflow. All of a sudden I heard two shots, thestarting of the jeep and some lights comeon across the river. I heard shouting—“Stop! Stop!” <strong>The</strong>n another shot was fired. Iwas sure my friend was in trouble,hopefully not caught or dead. I waited awhile and then heard some noises from thebushes across the river. I assumed theymust be chasing him now by jeep, but Iknew that the dirt road ended on the otherside after only 50 meters along the riverand doubted that the policemen wouldpursue my friend on foot after that. <strong>The</strong>jeep had stopped, but the lights were on forsome five minutes, and then I saw it turnaround, and go slowly back to the bridge.At this point I was not sure whether myfriend was caught or had gotten away. Iconcluded that there was nothing I coulddo. Sad and worried, I got on my bike andmade my way home at daylight. I wentstraight to bed.About noon I got up and told my aunt ofthe situation. She was sympathetic, andsaid, "It's terrible, this to be happening toyoung people." Later in the afternoon myyounger brother showed up, and told me,"Our friend is hiding at his youngerbrother's business place in Maribor, sinceearly this morning. But unfortunately theother friend is in hospital recuperating froma gun wound to his head, and is in criticalcondition." <strong>The</strong>n he added, "Did you knowthat the two friends had madearrangements to take our village neighbor’s16-year-old girl also with us to Germany?" I

said, "No, they never mentioned it to me,"<strong>The</strong>n he added, "Apparently the two havetaken other people across the border in thepast."It became clearer why the police weremaking such an effort to catch them, or us.To visit our friend in hospital would be toorisky; with his head wound he maysubconsciously reveal our identity. So I toldmy brother to go to our village and find outwhatever he could, and then to return thenext day at sundown—possibly with aborrowed bicycle (before the police gethold of his bike as well, and link me to thecase).<strong>The</strong> next morning I went back to work.When I returned at my usual time, 2.30p.m., I noticed two men on the bridge overa nearby creek just 100 meters from ourhouse. <strong>The</strong>y were appearing or pretendingto be reviewing the bridge, and had twodark-blue bicycles leaning against the post.I was sure they were plain-clothespolicemen, not engineers. I took my bike tothe back of the house in case I needed totake off in a hurry.My aunt said, "<strong>The</strong> two men on thebridge have been observing our house forthe past hour. l think they are the policedetectives." I thought it was best for me todisappear and stay with my oId escapematefor few nights. My aunt said, "Yesgood idea." As I gathered a few items andgot to my bike, one man approached mevia the front door; the other came aroundthe back. He asked me, "Is your nameAugustin?" I said, "Yes, and who are you?"<strong>The</strong>y never answered, but instead, said,

“We want to ask you a few questions!" Isaid, “That’s fine. Let’s sit down, and may Ioffer you some drinks?" One said, "Yes,just water please." <strong>The</strong>n he said, "We knowof your connection with the two fellows whocame from Germany, and we know youalso plan to escape to Germany withthem!" I said, "This is not true at all. I haveno reason: I have a good-paying job and agood place now to live." One of thepolicemen then asked, "Do you know thetwo fellows?” He mentioned their names. Isaid, “Yes, but they now live in Germany."<strong>The</strong>y looked at each other, got up, andsaid, “We will be back, if any of that is nottrue."<strong>The</strong>y left, and I was sure that, so far,they did not know the whole story. Aboutan hour later my brother came, along withthe bike I had borrowed for my nowfugitivefriend who was still hiding at hisbrother's business place in Maribor. <strong>The</strong>other borrowed bike was still held by thepolice, we concluded. My brother found outthat the police had investigated ourneighbor girl, alleging her of trying toescape with my friends. Her older brotherhad escaped to Germany some monthsbefore. I was wondering now just howmuch, and what she, being young andinexperienced, might have told the police.Before he left I asked my brother to keephis eyes and ears wide open, and to meetme the following day at my company'splace in Maribor after I finished work at 2p.m.I waited for him the next day until 3 p.m.;he didn't show up so I went home, a bit

puzzled. As I entered the house's hallwaymy aunt appeared, her finger pressedacross her mouth. I knew something iswrong, so I quietly proceeded into thekitchen. All of a sudden I was surroundedby police with guns drawn. Two wereholding machineguns, coming from mybedroom in the basement and from thebackyard. <strong>The</strong> one in plain clothes told meto sit down and wait until they finishedsearching the house, and my bedroom.After a while, he said, "we know you'rehiding your friend here, and we also knowof your plans of escape with them andother people!" I said, "None of this is true."<strong>The</strong>n he escorted me into my bedroom,and said," Now you better show me; whereis your correspondence hidden?" Everydrawer was opened, my clothing scatteredall over, but one highly visible item on mynight table was untouched—my homeremedy medicine book. This was where allmy letters were tucked carefully betweenpages; all those of my fugitive friend, andthose from my brother in Canada thatmentioned the two friends coming to fetchme. If they had found those, I would'vebeen cooked. But they kept grilling me,asking, "If you tell us now, of all those whowould escape, we'll not take you to prison."I said, "I don't plan to escape now or in thefuture, and don't know of anybody else whowould escape." I added, “But if you take meto prison, for one, I know I'll lose my job.<strong>The</strong>n as soon as I'm out of prison, I'll havea good reason to escape."He thought for a while, and said, "OK,you may visit your friend in hospital, and

you must report yourself every evening atour police station." I agreed, and they left.My aunt said, "You handled them verywell." I said, "After all, I'd know by now fromexperience."Aunt Angela – Photo taken in 1977 - Withouther help I would not have been able toescape<strong>The</strong> next day after my work, I wasreading the local newspaper while waitingfor my brother. I sadly found out that ourfriend in the hospital died—just hoursbefore I'd planned to visit him. He was 22years old, and left behind his wife, and twochildren. May he rest in peace.My brother hadn't shown by 3 p.m., so Iwas on the way home, stopping andreporting myself at the police station, wherethey also confirmed my friend's death.<strong>The</strong> next day, there was more bad news.I learned through the newspaper that ourfugitive friend had been captured, and wasin jail. I told my brother, “Let’s puteverything on hold and keep a watchful,low profile for a week or two. And see whataction will be necessary for us take, at anygiven moment.”I not only lost one good friend forever,but my other friend was now set to spendsome time in jail. I had also lost my

money, and my friend’s bicycle, which washeld by the police. And if I should claim thebicycle, that would implicate me in beinginvolved from the very beginning. (A newbicycle in those days cost a year of savingsfor the average worker; it was the mostimportant, if not the only, transportation formost people.) Still, a more perplexing andprecarious matter was my possibleforthcoming implication in the case.Because of that uncertainty I decided tosell my bicycle in case it would furtherimplicate me in the case. This would alsolet me escape in a hurry with some money.After few days I asked my jailed friend'sbrother to claim the bicycle from the police,under the pretext that the bike was takenfrom their place of business without his ortheir knowledge.It worked. A few days later, I picked it uplate one night at his business place andreturned it to my old friend, who said, "Ifyou sell yours, you’re welcome to usemine, for work, or any time.”After reporting faithfully to the policestation on a daily basis for about a month,the police asked me to do so only onMondays from then on. I guess they gottired of my face. I'd tried to visit my friend inprison, and was told I could but only afterhis trial. I was hoping he would escape. Butwith his past record of jail escapes, thechances were slim.I sold my bike, bought some Austrianschillings and German marks on the blackmarket. I was ready to escape at anymoment.

It was in the first week of August when Ireceived a summons to appear in court formy friend's trial on escape number 5, Ibelieve. I was now facing not only the trialand a possible lengthy jail sentence, but Iwas also being branded to serve two yearsin the Army, which was scheduled to startthe last week September. I had no secondthoughts: escape was my solution. Due tomy previous experiences, I decided to goalone.Nobody can give you freedom. Nobodycan give your equality or justice oranything. If your a man you take it.Malcolm X, 1965

<strong>Six</strong>th Escape - FreedomI went to the library to get detailed mapsof the Austrian and German borders, andmaps of each country. Studying them well,I noted the villages, especially near theborders, the cities, the country roads, thehighways and byways, the railways, therivers, and the best and shortest routeleading to my destination—the refugeecamp in Nuremberg, Germany.On 1 September 1959, at 9 p.m. I wasoff, with my foreign money well hidden,sewn into my pants. I wore a double shirt, atie, good shoes, and carried a flashlight,raincoat, and a nice briefcase to look morelike a student while walking in a town orcity. And of course, last but not least, theblack pepper powder mixed with devilishlyhot red pepper.Walking from Pesnica to the border nearSentilj is about 20 kilometers; about fivehours of tracking. I crossed hills that hadscattered farms, vineyards, and cattle, thenbegan ascending into the forestedmountains near the border. This time I wasdetermined not to make the same mistakeas during my second escape, when wewalked into the border guardhouse. I knewthat when I hit the River Mura, crossed it,and then walked upstream along the riveras far as Graz, or even to Bruck ouf derMur, things would be different this time.This was where, on our second escape, wewound up in jail.It was a very dark, cloudy night, and Iavoided farms, people, and dogs very

carefully, and successfully, all the way intothe mountains, enjoying along the way myfavorite seasonal fruits: grapes, apples,and pears. It was about 2 a.m. when Irealized that the border must be near. I satdown. It was dead quiet, except for a nightowl. <strong>The</strong>n I could hear the river flowing; Ithought it must be the Mura River. I resteda while and then continued. All of a suddenI fell over some wooden logs, and the logsrolled down the mountain making a hell ofnoise. About 200 meters away a dog burstinto barking; it sounded like a Germanshepherd. It was followed by a man shouting,"Stop, whoever you are, or I willshoot you!" I thought it must be a borderguard, and since it was too dark for him tosee me, or even aim at me, I decided todash toward the river. As I ran, a shot wasfired and soon the dog started closing in onme. I kept running full steam, and thensuddenly fell into a steep gorge, tumblingdown until I hit the water. I got up andbegan crossing—it was fast flowing, bellydeep, and difficult to resist the current. Istumbled over a rock, and down I went.After drifting for a minute, I got up andcrossed the river, which I concluded to beMura.And then I was in Austria – Freedom.<strong>The</strong> dog kept barking, and the manbeside the dog kept telling it to keep quiet. Ibegan running away, upstream of the river

for about an hour, where I sat down, totallywet, but happy nonetheless. <strong>The</strong> first, andmost important obstacle was now behindme. Soon I resumed running, trying toavoid getting pneumonia. By daylight I wasdry, and was able to clean off my soiledclothing, shoes, and retrieve my sewn-inAustrian schillings from my pants.I thought it would be safest to journey toSalzburg, Austria or the German border byfoot. It was about 350 kilometers away andwould take four to five days of walking.Time was something I had, also the moneyfor food and drink, because I was notspending it on train tickets. It would meanwalking on farm roads crossing manyfields, rivers, and streams, climbing overmany hills and mountains. Walking on oralong the highways would be risky becauseof police patrols, (except at nighttime, whenthe advancing lights would give me achance to hide).In an hour I came to a small village, wentto a general store and bought sandwiches,milk, etc. Fortunately the person workingthere was a friendly young girl, who askedme, "Do you live here in this village?" Isaid, "No, in Graz." She said, “That’s what Ithought." I guess I’d fooled her, sporting myclean white shirt and a tie. I continuedwalking across the potato, corn, wheat,turnip, and carrot fields. Here and there Iwalked through orchards, and so wasassured of the fruit along the way. Avoidinghouses, villages, and towns as much as Icould, I kept close to the River Mura.Although my shoes were comfortable, I stillwalked barefoot most of the time. <strong>The</strong> first