- Page 2 and 3:

With Amusement for All

- Page 5:

Publication of this volume was made

- Page 9 and 10:

viii PrefaceIt has both provided im

- Page 11 and 12:

x Prefaceerences, presence, and per

- Page 13 and 14:

This page intentionally left blank

- Page 15 and 16:

2 With Amusement for Allsocieties a

- Page 17 and 18:

4 With Amusement for Allphy. Over t

- Page 19 and 20:

6 With Amusement for Allin the colo

- Page 21 and 22:

8 With Amusement for Allthat displa

- Page 23 and 24:

10 With Amusement for Allguished co

- Page 25 and 26:

12 With Amusement for Allwell as th

- Page 27 and 28:

14 With Amusement for Allone side

- Page 29 and 30:

16 With Amusement for Alllittle mor

- Page 31 and 32:

18 With Amusement for Allweapon wou

- Page 33 and 34:

20 With Amusement for Allblack folk

- Page 35 and 36:

22 With Amusement for Allthe histor

- Page 37 and 38:

24 With Amusement for Allbefore neg

- Page 39 and 40:

26 With Amusement for Allcommunitie

- Page 41 and 42:

28 With Amusement for Allshe picked

- Page 43 and 44:

30 With Amusement for Allspectators

- Page 45 and 46:

32 With Amusement for Alllist of po

- Page 47 and 48:

34 With Amusement for Allperiority.

- Page 49 and 50:

36 With Amusement for Alldence game

- Page 51 and 52:

38 With Amusement for Allparty expe

- Page 53 and 54:

40 With Amusement for Allthe boxes,

- Page 55 and 56:

42 With Amusement for Alllittle urb

- Page 57 and 58:

44 With Amusement for Allserve and

- Page 59 and 60:

46 With Amusement for Allbled, as F

- Page 61 and 62:

48 With Amusement for Allety of com

- Page 63 and 64:

50 With Amusement for Alllast words

- Page 65 and 66:

52 With Amusement for Allcharged pe

- Page 67 and 68:

54 With Amusement for All“Brudder

- Page 69 and 70:

56 With Amusement for All(about $31

- Page 71 and 72:

58 With Amusement for Allthe onset

- Page 73 and 74:

60 With Amusement for Allso central

- Page 75 and 76:

62 With Amusement for AllSchmidt ha

- Page 77 and 78:

64 With Amusement for AllBennett po

- Page 79 and 80:

66 With Amusement for Allcide that

- Page 81 and 82:

68 With Amusement for Allinternatio

- Page 83 and 84:

70 With Amusement for Allthe implic

- Page 85 and 86:

72 With Amusement for Allinfluenced

- Page 87 and 88:

74 With Amusement for Allthe circus

- Page 89 and 90:

76 With Amusement for Allcuses. Ant

- Page 91 and 92:

78 With Amusement for Allment with

- Page 93 and 94:

80 With Amusement for Allchildren.

- Page 95 and 96:

82 With Amusement for All“I am so

- Page 97 and 98:

84 With Amusement for Alllaziness o

- Page 99 and 100:

86 With Amusement for Allamusement

- Page 101 and 102:

88 With Amusement for Allwishing th

- Page 103 and 104:

90 With Amusement for Allsons than

- Page 105 and 106:

92 With Amusement for Allit with a

- Page 107 and 108:

94 With Amusement for Allognizable

- Page 109 and 110:

96 With Amusement for Allretire a s

- Page 111 and 112:

98 With Amusement for Allfied belie

- Page 113 and 114:

100 With Amusement for Alltown team

- Page 115 and 116:

102 With Amusement for Allmales to

- Page 117 and 118:

104 With Amusement for Allgame, the

- Page 119 and 120:

106 With Amusement for Allsense of

- Page 121 and 122:

108 With Amusement for Allcondescen

- Page 123 and 124:

110 With Amusement for AllSuffering

- Page 125 and 126:

112 With Amusement for Alling on th

- Page 127 and 128:

114 With Amusement for Allno impert

- Page 129 and 130:

116 With Amusement for Allbut illus

- Page 131 and 132:

118 With Amusement for Allyear afte

- Page 133 and 134:

120 With Amusement for Alltreachero

- Page 135 and 136:

122 With Amusement for Allberths.

- Page 137 and 138:

124 With Amusement for AllBurns not

- Page 139 and 140:

126 With Amusement for AllKubelski

- Page 141 and 142:

128 With Amusement for Allspaces. T

- Page 143 and 144:

130 With Amusement for AllCrazy abo

- Page 145 and 146:

132 With Amusement for Allplished m

- Page 147 and 148:

134 With Amusement for AllThe comin

- Page 149 and 150:

136 With Amusement for Allbecame th

- Page 151 and 152:

138 With Amusement for Allnecessari

- Page 153 and 154:

140 With Amusement for Allried the

- Page 155 and 156:

142 With Amusement for Allfence mov

- Page 157 and 158:

144 With Amusement for Alling point

- Page 159 and 160:

146 With Amusement for AllBible bet

- Page 161 and 162:

148 With Amusement for Allquences.

- Page 163 and 164:

150 With Amusement for All“We adm

- Page 165 and 166:

152 With Amusement for Allple who a

- Page 167 and 168:

154 With Amusement for Allsively cl

- Page 169 and 170: 156 With Amusement for Allranged fr

- Page 171 and 172: 158 With Amusement for AllAlthough

- Page 173 and 174: 160 With Amusement for Alland uncha

- Page 175 and 176: 162 With Amusement for Allsheet mus

- Page 177 and 178: 164 With Amusement for Allsouth of

- Page 179 and 180: 166 With Amusement for All“probab

- Page 181 and 182: 168 With Amusement for Alllar cultu

- Page 183 and 184: 170 With Amusement for Alland the e

- Page 185 and 186: 172 With Amusement for Allhis cynic

- Page 187 and 188: 174 With Amusement for Allerator wh

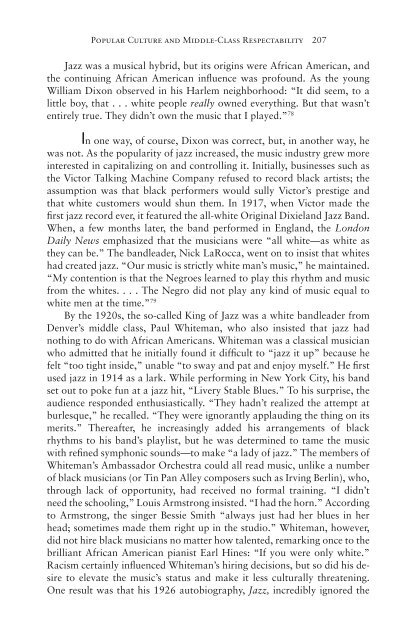

- Page 189 and 190: 6Popular Culture and Middle-ClassRe

- Page 191 and 192: 178 With Amusement for Alling “Bl

- Page 193 and 194: 180 With Amusement for AllCrucial t

- Page 195 and 196: 182 With Amusement for Allfined”

- Page 197 and 198: 184 With Amusement for Allately to

- Page 199 and 200: 186 With Amusement for Allnies were

- Page 201 and 202: 188 With Amusement for Allthey desp

- Page 203 and 204: 190 With Amusement for Alltheaters.

- Page 205 and 206: 192 With Amusement for AllOriental

- Page 207 and 208: 194 With Amusement for Allfrom adul

- Page 209 and 210: 196 With Amusement for Allfan becam

- Page 211 and 212: 198 With Amusement for AllZiegfeld

- Page 213 and 214: 200 With Amusement for Allthe Midwa

- Page 215 and 216: 202 With Amusement for All1926, her

- Page 217 and 218: 204 With Amusement for Allyour brot

- Page 219: 206 With Amusement for Allstarted l

- Page 223 and 224: 210 With Amusement for Allsetter, b

- Page 225 and 226: 212 With Amusement for Allbrilliant

- Page 227 and 228: 214 With Amusement for Alldemocracy

- Page 229 and 230: 216 With Amusement for AllStreet, U

- Page 231 and 232: 218 With Amusement for AllThe Warne

- Page 233 and 234: 220 With Amusement for Alllift sent

- Page 235 and 236: 222 With Amusement for Allture the

- Page 237 and 238: 224 With Amusement for Allonly said

- Page 239 and 240: 226 With Amusement for Allthe actor

- Page 241 and 242: 228 With Amusement for Allhard soci

- Page 243 and 244: 230 With Amusement for Alldid not c

- Page 245 and 246: 232 With Amusement for AllFranklin

- Page 247 and 248: 234 With Amusement for Allalmost fa

- Page 249 and 250: 236 With Amusement for Alltune.”

- Page 251 and 252: 238 With Amusement for Allbest band

- Page 253 and 254: 240 With Amusement for Allistration

- Page 255 and 256: 242 With Amusement for Alltance.

- Page 257 and 258: 244 With Amusement for Allboxing fa

- Page 259 and 260: 246 With Amusement for All$48 in 19

- Page 261 and 262: 248 With Amusement for Allmake perf

- Page 263 and 264: 250 With Amusement for Allnot contr

- Page 265 and 266: 252 With Amusement for AllThe growt

- Page 267 and 268: 254 With Amusement for AllChicago D

- Page 269 and 270: 256 With Amusement for Alldoor’s

- Page 271 and 272:

258 With Amusement for Allon the si

- Page 273 and 274:

260 With Amusement for Allthey were

- Page 275 and 276:

262 With Amusement for Allwar. Duri

- Page 277 and 278:

264 With Amusement for Allghost tow

- Page 279 and 280:

266 With Amusement for Allwhich hos

- Page 281 and 282:

268 With Amusement for AllBaltimore

- Page 283 and 284:

270 With Amusement for Allwe’re f

- Page 285 and 286:

272 With Amusement for Allarea, flo

- Page 287 and 288:

274 With Amusement for Allbeating u

- Page 289 and 290:

276 With Amusement for Allanother s

- Page 291 and 292:

278 With Amusement for Allfantasy s

- Page 293 and 294:

280 With Amusement for AllPopular c

- Page 295 and 296:

282 With Amusement for Allanother R

- Page 297 and 298:

284 With Amusement for Alllike tryi

- Page 299 and 300:

286 With Amusement for AllLeague ga

- Page 301 and 302:

288 With Amusement for AllPerhaps b

- Page 303 and 304:

290 With Amusement for Allcy with a

- Page 305 and 306:

292 With Amusement for Allproducts

- Page 307 and 308:

294 With Amusement for Allthe Motio

- Page 309 and 310:

296 With Amusement for Alljust join

- Page 311 and 312:

298 With Amusement for Allentertain

- Page 313 and 314:

300 With Amusement for AllGunsmoke

- Page 315 and 316:

9Counterpoints to Consensus“The s

- Page 317 and 318:

304 With Amusement for AllThe brood

- Page 319 and 320:

306 With Amusement for Alland all t

- Page 321 and 322:

308 With Amusement for Allhis hand.

- Page 323 and 324:

310 With Amusement for Alland, each

- Page 325 and 326:

312 With Amusement for Allof abunda

- Page 327 and 328:

314 With Amusement for Alltitles fe

- Page 329 and 330:

316 With Amusement for Alltial cand

- Page 331 and 332:

318 With Amusement for Allcultural

- Page 333 and 334:

320 With Amusement for Alla big bus

- Page 335 and 336:

322 With Amusement for Allclearly a

- Page 337 and 338:

324 With Amusement for AllCharlie P

- Page 339 and 340:

326 With Amusement for Alltant char

- Page 341 and 342:

328 With Amusement for AllWar fears

- Page 343 and 344:

330 With Amusement for Alling NBC

- Page 345 and 346:

332 With Amusement for AllStill, as

- Page 347 and 348:

334 With Amusement for Allfills a v

- Page 349 and 350:

336 With Amusement for AllWhen the

- Page 351 and 352:

338 With Amusement for Allorder. En

- Page 353 and 354:

340 With Amusement for Allwas the s

- Page 355 and 356:

342 With Amusement for Allcompeting

- Page 357 and 358:

344 With Amusement for AllAs the ev

- Page 359 and 360:

346 With Amusement for Allduced Fat

- Page 361 and 362:

10Popular Culture and1960s FermentD

- Page 363 and 364:

350 With Amusement for Allample, us

- Page 365 and 366:

352 With Amusement for Allment had

- Page 367 and 368:

354 With Amusement for Allasked,

- Page 369 and 370:

356 With Amusement for Allas the me

- Page 371 and 372:

358 With Amusement for AllMinow des

- Page 373 and 374:

360 With Amusement for Allers who w

- Page 375 and 376:

362 With Amusement for Allsues, of

- Page 377 and 378:

364 With Amusement for Alltheless,

- Page 379 and 380:

366 With Amusement for Allcapture a

- Page 381 and 382:

368 With Amusement for Allblack pla

- Page 383 and 384:

370 With Amusement for Allresisted

- Page 385 and 386:

372 With Amusement for AllI ever he

- Page 387 and 388:

374 With Amusement for Alltheir hai

- Page 389 and 390:

376 With Amusement for Allfacility.

- Page 391 and 392:

378 With Amusement for Allthem to

- Page 393 and 394:

380 With Amusement for Allincredulo

- Page 395 and 396:

382 With Amusement for Alltier maga

- Page 397 and 398:

384 With Amusement for Allmother an

- Page 399 and 400:

386 With Amusement for AllShot Libe

- Page 401 and 402:

388 With Amusement for Allback. As

- Page 403 and 404:

390 With Amusement for Allproductio

- Page 405 and 406:

392 With Amusement for Allaudiences

- Page 407 and 408:

11Up for GrabsLEAVING THE 1960SAs t

- Page 409 and 410:

396 With Amusement for All1946, tha

- Page 411 and 412:

398 With Amusement for AllThe exerc

- Page 413 and 414:

400 With Amusement for Allan infusi

- Page 415 and 416:

402 With Amusement for AllAs the ec

- Page 417 and 418:

404 With Amusement for Alloverwhelm

- Page 419 and 420:

406 With Amusement for Allthe actor

- Page 421 and 422:

408 With Amusement for Alltural ide

- Page 423 and 424:

410 With Amusement for Allwith best

- Page 425 and 426:

412 With Amusement for Allder but t

- Page 427 and 428:

414 With Amusement for Allitics (pa

- Page 429 and 430:

416 With Amusement for AllConfedera

- Page 431 and 432:

418 With Amusement for AllIn 1974,

- Page 433 and 434:

420 With Amusement for Alland had b

- Page 435 and 436:

422 With Amusement for Allaters and

- Page 437 and 438:

424 With Amusement for AllAwards, i

- Page 439 and 440:

426 With Amusement for Allterm for

- Page 441 and 442:

428 With Amusement for Allteen year

- Page 443 and 444:

430 With Amusement for Allcontracts

- Page 445 and 446:

432 With Amusement for Alloffered c

- Page 447 and 448:

434 With Amusement for Allfrom a di

- Page 449 and 450:

436 With Amusement for AllThe dance

- Page 451 and 452:

438 With Amusement for Allture in h

- Page 453 and 454:

440 With Amusement for Allmoment a

- Page 455 and 456:

442 With Amusement for Allniently m

- Page 457 and 458:

444 With Amusement for Alllighted i

- Page 459 and 460:

446 With Amusement for Allregarding

- Page 461 and 462:

448 With Amusement for Allon TV, on

- Page 463 and 464:

450 With Amusement for Allchild, bu

- Page 465 and 466:

452 With Amusement for Alldied.”

- Page 467 and 468:

454 With Amusement for Allstriction

- Page 469 and 470:

456 With Amusement for AllTed Turne

- Page 471 and 472:

458 With Amusement for Alltion. Pop

- Page 473 and 474:

460 With Amusement for Allturn with

- Page 475 and 476:

462 With Amusement for AllAmericans

- Page 477 and 478:

464 With Amusement for All2005, the

- Page 479 and 480:

466 With Amusement for AllSexual th

- Page 481 and 482:

468 With Amusement for Allits criti

- Page 483 and 484:

470 With Amusement for Allpeal and

- Page 485 and 486:

472 With Amusement for AllEarnhardt

- Page 487 and 488:

474 With Amusement for Allwho showe

- Page 489 and 490:

476 With Amusement for Allbag,” a

- Page 491 and 492:

478 With Amusement for Alldescripti

- Page 493 and 494:

480 With Amusement for AllCommunist

- Page 495 and 496:

482 With Amusement for AllDaughter

- Page 497 and 498:

484 With Amusement for AllCertainly

- Page 499 and 500:

486 With Amusement for Alllishing h

- Page 501 and 502:

488 With Amusement for Allconcernin

- Page 503 and 504:

490 With Amusement for Alland locko

- Page 505 and 506:

492 With Amusement for Alllegacy wa

- Page 507 and 508:

494 With Amusement for AllThe “en

- Page 509 and 510:

496 With Amusement for Allabout a p

- Page 511 and 512:

498 With Amusement for Alled up hel

- Page 513 and 514:

500 With Amusement for Allshort tim

- Page 515 and 516:

502 With Amusement for AllCBS fired

- Page 517 and 518:

504 With Amusement for Alltion: “

- Page 519 and 520:

506 With Amusement for Allscribed F

- Page 521 and 522:

508 With Amusement for Allit the pr

- Page 523 and 524:

510 With Amusement for Allchanging,

- Page 525 and 526:

512 With Amusement for Allcently pu

- Page 527 and 528:

514 With Amusement for AllBuruma wa

- Page 529 and 530:

516 With Amusement for Allised to p

- Page 531 and 532:

NOTESPreface1. Michael Mandelbaum,

- Page 533 and 534:

520 Notes to Pages 7-1417. Robert M

- Page 535 and 536:

522 Notes to Pages 20-2829. Christi

- Page 537 and 538:

524 Notes to Pages 38-4576. Tucher,

- Page 539 and 540:

526 Notes to Pages 53-6340. Finson,

- Page 541 and 542:

528 Notes to Pages 74-823. Isenberg

- Page 543 and 544:

530 Notes to Pages 89-9839. Toll, B

- Page 545 and 546:

532 Notes to Pages 109-1173. Toll,

- Page 547 and 548:

534 Notes to Pages 125-13636. DiMeg

- Page 549 and 550:

536 Notes to Pages 148-15712. Leith

- Page 551 and 552:

538 Notes to Pages 164-17151. Giddi

- Page 553 and 554:

540 Notes to Pages 180-18910. Ibid.

- Page 555 and 556:

542 Notes to Pages 197-206and a hos

- Page 557 and 558:

544 Notes to Pages 214-22196. Hilme

- Page 559 and 560:

546 Notes to Pages 229-236“Siblin

- Page 561 and 562:

548 Notes to Pages 247-25362. On ra

- Page 563 and 564:

550 Notes to Pages 261-269Baughman,

- Page 565 and 566:

552 Notes to Pages 277-284American

- Page 567 and 568:

554 Notes to Pages 289-296Frontier

- Page 569 and 570:

556 Notes to Pages 304-3096. See, e

- Page 571 and 572:

558 Notes to Pages 317-32441. Weyr,

- Page 573 and 574:

560 Notes to Pages 331-33877. Jones

- Page 575 and 576:

562 Notes to Pages 340-345100. Mill

- Page 577 and 578:

564 Notes to Pages 353-36212. Will

- Page 579 and 580:

566 Notes to Pages 372-378unorthodo

- Page 581 and 582:

568 Notes to Pages 386-394100. Slot

- Page 583 and 584:

570 Notes to Pages 403-411Bulls, 15

- Page 585 and 586:

572 Notes to Pages 419-427Waterman,

- Page 587 and 588:

574 Notes to Pages 435-444108. Geor

- Page 589 and 590:

576 Notes to Pages 451-45924. Ibid.

- Page 591 and 592:

578 Notes to Pages 465-472veys); Jo

- Page 593 and 594:

580 Notes to Pages 479-48498. Diamo

- Page 595 and 596:

582 Notes to Pages 492-499kane, WA,

- Page 597 and 598:

584 Notes to Pages 505-51026. Frank

- Page 599 and 600:

586 Notes to Pages 513-51720 (“ba

- Page 601 and 602:

588 BibliographyButsch, Richard.

- Page 603 and 604:

590 BibliographyKeetley, Dawn. “V

- Page 605 and 606:

592 Bibliography———. “Profe

- Page 607 and 608:

594 BibliographyBailey, Beth, and D

- Page 609 and 610:

596 BibliographyChenoweth, Lawrence

- Page 611 and 612:

598 BibliographyDiMeglio, John E. V

- Page 613 and 614:

600 BibliographyGilbert, James. A C

- Page 615 and 616:

602 BibliographyJohnson, Paul. Sam

- Page 617 and 618:

604 BibliographyLott, Eric. Love an

- Page 619 and 620:

606 BibliographyMurray, Susan, and

- Page 621 and 622:

608 BibliographyReyes, David, and T

- Page 623 and 624:

610 BibliographySmith, Suzanne E. D

- Page 625 and 626:

612 BibliographyWeyr, Thomas. Reach

- Page 627 and 628:

614 IndexAmerica: A Tribute to Hero

- Page 629 and 630:

616 IndexBelushi, John, 424Ben-Hur,

- Page 631 and 632:

618 IndexButton-Down Mind of Bob Ne

- Page 633 and 634:

620 Indexand Great Depression, 234;

- Page 635 and 636:

622 IndexDenver, John, 415, 420Depa

- Page 637 and 638:

624 IndexFirst Blood, 449First Mond

- Page 639 and 640:

626 IndexGuccione, Bob, 398-99Guess

- Page 641 and 642:

628 IndexI Spy, 361, 362“Is That

- Page 643 and 644:

630 IndexLast Picture Show, The, 40

- Page 645 and 646:

632 IndexMcCleary, Jonathan, 9McCom

- Page 647 and 648:

634 Index437; and minstrelsy, 19-20

- Page 649 and 650:

636 IndexPainted Dreams, 251Paley,

- Page 651 and 652:

638 Indexdent recording companies,

- Page 653 and 654:

640 IndexMTV, 468; and music indust

- Page 655 and 656:

642 IndexSitting Bull, 81, 84, 104S

- Page 657 and 658:

644 IndexTanguay, Eva, 125, 129-30,

- Page 659 and 660:

646 Indexies, 225-26; origins of, 1

- Page 661:

648 Index“Will You Love Me Tomorr