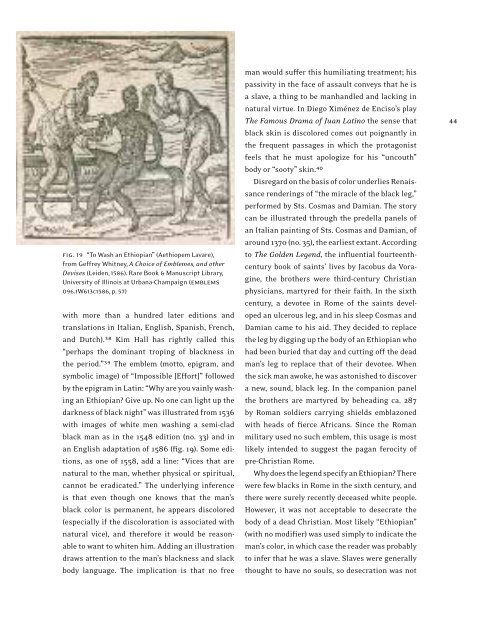

fig. 19 “To Wash an Ethiopian” (Aethiopem Lavare),from Geffrey Whitney, A Choice of Emblemes, and o<strong>the</strong>rDevises (Leiden, 1586). Rare Book & Manuscript Library,University of Ill<strong>in</strong>ois at Urbana-Champaign (emblems096.1W613c1586, p. 57)with more than a hundred later editions andtranslations <strong>in</strong> Italian, English, Spanish, French,and Dutch).38 Kim Hall has rightly called this“perhaps <strong>the</strong> dom<strong>in</strong>ant trop<strong>in</strong>g of blackness <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> period.”39 The emblem (motto, epigram, andsymbolic image) of “Impossible [Effort]” followedby <strong>the</strong> epigram <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong>: “Why are you va<strong>in</strong>ly wash<strong>in</strong>gan Ethiopian? Give up. No one can light up <strong>the</strong>darkness of black night” was illustrated from 1536with images of white men wash<strong>in</strong>g a semi-cladblack man as <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1548 edition (no. 33) and <strong>in</strong>an English adaptation of 1586 (fig. 19). Some editions,as one of 1558, add a l<strong>in</strong>e: “Vices that arenatural to <strong>the</strong> man, whe<strong>the</strong>r physical or spiritual,cannot be eradicated.” The underly<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>ferenceis that even though one knows that <strong>the</strong> man’sblack color is permanent, he appears discolored(especially if <strong>the</strong> discoloration is associated withnatural vice), and <strong>the</strong>refore it would be reasonableto want to whiten him. Add<strong>in</strong>g an illustrationdraws attention to <strong>the</strong> man’s blackness and slackbody language. The implication is that no freeman would suffer this humiliat<strong>in</strong>g treatment; hispassivity <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> face of assault conveys that he isa slave, a th<strong>in</strong>g to be manhandled and lack<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>natural virtue. In Diego Ximénez de Enciso’s playThe Famous Drama of Juan Lat<strong>in</strong>o <strong>the</strong> sense thatblack sk<strong>in</strong> is discolored comes out poignantly <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> frequent passages <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong> protagonistfeels that he must apologize for his “uncouth”body or “sooty” sk<strong>in</strong>.40Disregard on <strong>the</strong> basis of color underlies Renaissancerender<strong>in</strong>gs of “<strong>the</strong> miracle of <strong>the</strong> black leg,”performed by Sts. Cosmas and Damian. The storycan be illustrated through <strong>the</strong> predella panels ofan Italian pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g of Sts. Cosmas and Damian, ofaround 1370 (no. 35), <strong>the</strong> earliest extant. Accord<strong>in</strong>gto The Golden Legend, <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fluential fourteenthcenturybook of sa<strong>in</strong>ts’ lives by Jacobus da Vorag<strong>in</strong>e,<strong>the</strong> bro<strong>the</strong>rs were third-century Christianphysicians, martyred for <strong>the</strong>ir faith. In <strong>the</strong> sixthcentury, a devotee <strong>in</strong> Rome of <strong>the</strong> sa<strong>in</strong>ts developedan ulcerous leg, and <strong>in</strong> his sleep Cosmas andDamian came to his aid. They decided to replace<strong>the</strong> leg by digg<strong>in</strong>g up <strong>the</strong> body of an Ethiopian whohad been buried that day and cutt<strong>in</strong>g off <strong>the</strong> deadman’s leg to replace that of <strong>the</strong>ir devotee. When<strong>the</strong> sick man awoke, he was astonished to discovera new, sound, black leg. In <strong>the</strong> companion panel<strong>the</strong> bro<strong>the</strong>rs are martyred by behead<strong>in</strong>g ca. 287by Roman soldiers carry<strong>in</strong>g shields emblazonedwith heads of fierce Africans. S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> Romanmilitary used no such emblem, this usage is mostlikely <strong>in</strong>tended to suggest <strong>the</strong> pagan ferocity ofpre-Christian Rome.Why does <strong>the</strong> legend specify an Ethiopian? Therewere few blacks <strong>in</strong> Rome <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sixth century, and<strong>the</strong>re were surely recently deceased white people.However, it was not acceptable to desecrate <strong>the</strong>body of a dead Christian. Most likely “Ethiopian”(with no modifier) was used simply to <strong>in</strong>dicate <strong>the</strong>man’s color, <strong>in</strong> which case <strong>the</strong> reader was probablyto <strong>in</strong>fer that he was a slave. Slaves were generallythought to have no souls, so desecration was not44

45<strong>europe</strong>an perceptions of blackness as reflected <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> visual artsan issue.41 The subject was taken up elsewhere <strong>in</strong>Europe. In <strong>the</strong> charged atmosphere surround<strong>in</strong>gChristian attitudes toward Moriscos <strong>in</strong> sixteenthcenturySpa<strong>in</strong>, <strong>the</strong> imagery could be brutal. Thescene from an altarpiece for <strong>the</strong> Monastery of SanFrancisco <strong>in</strong> Valladolid is gruesome: <strong>the</strong> blackman is alive, scream<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> pa<strong>in</strong> and horror. It isdifficult today to understand how <strong>the</strong> image couldbe condoned, much less commissioned.The aes<strong>the</strong>tic evaluation of black Africans alsodepended on facial features, <strong>the</strong> broad, flat nose,and large lips associated with <strong>the</strong> Land of <strong>the</strong>Blacks, always contrasted with European ideals.Europeans travelers <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sub-Sahara might observea range of features, much as <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> faces ofEuropeans;42 however, <strong>in</strong> Europe <strong>the</strong> reason tocall attention to <strong>the</strong>m was usually to mark whatwere perceived to be stereotypic deficiencies. Thisis starkly exemplified by a caricature-like study(fig. 20) of about 1615 by <strong>the</strong> youthful Jacob deGheyn III drawn from a plaster cast <strong>in</strong> his fa<strong>the</strong>r’sstudio,43 possibly <strong>in</strong> preparation for a Mock<strong>in</strong>g ofChrist dated 1616,44 <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong> soldier threaten<strong>in</strong>gChrist caricatures a black African, his exaggeratedlylarge, parted lips and pig nose meantto convey savage bloodlust. Such images arerem<strong>in</strong>ders of <strong>the</strong> persistent belief that both <strong>in</strong>nerbeauty and corruption are manifested <strong>in</strong> outwardappearance.45Never<strong>the</strong>less, for most artists such as Veronese(nos. 53, 54) who made studies from life, usuallywith black chalk, of <strong>the</strong> heads of black Africans,it seems to have been more an <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> simply<strong>in</strong>troduc<strong>in</strong>g variety <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong>ir narrative subjectsthat prompted <strong>the</strong>ir studies. The pose and handgestures of <strong>the</strong> black man <strong>in</strong> an elegant, unpublishedstudy <strong>in</strong> Philadelphia (no. 57), loosely attributedto Lodovico Carracci, suggest it was <strong>in</strong>tendedfor such a usage but until <strong>the</strong> attribution can bemore securely anchored, this is speculation.A fur<strong>the</strong>r perspective on variation is providedby a text and illustration (fig. 21 and no. 36) <strong>in</strong>top fig. 20 Jacob de Gheyn III (Dutch, ca. 1596–1641),Studies from Plaster Casts. Black chalk, pen and brown<strong>in</strong>k, 21.3 × 28.3 cm. Musée de Louvre, Cab<strong>in</strong>et des Dess<strong>in</strong>s(19997)above fig. 21 Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471–1528),Four Proportional Studies of Heads, from Vier Bücher vonmenschlicher Proportion, no. 36. The Walters Art Museum,Baltimore (92.437, p. 95v)

- Page 2: evealing the african presencein ren

- Page 5 and 6: evealinhe AfricaPresence enaissan E

- Page 9 and 10: Director’s forewordRevealing the

- Page 12 and 13: or Slavic origin. The result was a

- Page 15 and 16: The Lives of African Slavesand Peop

- Page 17 and 18: 15the lives of african slaves and p

- Page 19 and 20: 17the lives of african slaves and p

- Page 21 and 22: 19the lives of african slaves and p

- Page 23 and 24: 21the lives of african slaves and p

- Page 25 and 26: 23the lives of african slaves and p

- Page 27 and 28: 25the lives of african slaves and p

- Page 29 and 30: 27the lives of african slaves and p

- Page 31 and 32: 29the lives of african slaves and p

- Page 33 and 34: 31the lives of african slaves and p

- Page 35: 69. Cf. Megan Holmes, “‘How a W

- Page 38 and 39: construction of identity, through t

- Page 40 and 41: Testament: as in Christ’s declara

- Page 42 and 43: men dressed as Hungarian soldiers,

- Page 44 and 45: 42fig. 17 Titian (Italian, ca. 1488

- Page 48 and 49: Albrecht Dürer’s Four Books of H

- Page 50 and 51: 48left fig. 24 Workshop of Girolamo

- Page 52 and 53: A telling comparison can be made in

- Page 54 and 55: fig. 29 Maerten van Heemskerck (Net

- Page 56 and 57: demonstrating the qualities of iron

- Page 58 and 59: 122-33, 174; Benjamin Braude, “Th

- Page 60 and 61: 49. As cited by Baker, Plain Ugly,

- Page 63 and 64: “Leo Africanus” PresentsAfrica

- Page 65 and 66: 63“leo africanus” presents afri

- Page 67 and 68: 65“leo africanus” presents afri

- Page 69 and 70: 67“leo africanus” presents afri

- Page 71 and 72: 69“leo africanus” presents afri

- Page 73 and 74: 71“leo africanus” presents afri

- Page 75 and 76: would look like in Fez or what he t

- Page 77 and 78: notes75“leo africanus” presents

- Page 79 and 80: 77“leo africanus” presents afri

- Page 81: 79“leo africanus” presents afri

- Page 84 and 85: placeholder82fig. 35 Johannes van D

- Page 86 and 87: is a self-portrait. Giorgio Vasari

- Page 88 and 89: 86fig. 38 Friedrich Hagenauer(Germa

- Page 90 and 91: 88fig. 39 Jan Jansz Mostaert (Nethe

- Page 92 and 93: fig. 41 Jacob de Gheyn II (Flemish,

- Page 94 and 95: notes1. A. C. de C. M. Saunders, A

- Page 96 and 97:

29. In examining the painting, Carl

- Page 98 and 99:

64. In contrast, Pontormo’s Portr

- Page 101 and 102:

Visual Representations of an Elite:

- Page 103 and 104:

101visual representations of an eli

- Page 105 and 106:

103visual representations of an eli

- Page 107 and 108:

105visual representations of an eli

- Page 109 and 110:

107visual representations of an eli

- Page 111 and 112:

109visual representations of an eli

- Page 113 and 114:

111visual representations of an eli

- Page 115 and 116:

notes113visual representations of a

- Page 117 and 118:

115visual representations of an eli

- Page 119:

List of LendersaustriaAlbertina, Vi

- Page 122 and 123:

provenance Collection of Edmond Fou

- Page 124 and 125:

1516[ 15 ]Mori neri [Black Moors]Fr

- Page 126 and 127:

[ 24 ]girolamo da santacroce (Itali

- Page 128 and 129:

color and prejudice3132[ 31 ]Court

- Page 130 and 131:

[ 40 ]Flemish or French (?)Black Wo

- Page 132 and 133:

slaves[ 48 ]Circle of Bartolomeo Pa

- Page 134 and 135:

[ 55 ]albrecht dürer (German, 1471

- Page 136 and 137:

[ 62 ]bronzino (agnolo di cosimo to

- Page 138 and 139:

69707172[ 69 ]cristofano dell’alt

- Page 140 and 141:

7778 79[ 77 ]andrés sánchez galqu

- Page 142 and 143:

Hahn, Thomas. “The Difference the

- Page 144 and 145:

Curator’s AcknowledgmentsSo many

- Page 146 and 147:

Photography CreditsAlbertina, Vienn