revealing-the-african-presence-in-renaissance-europe

revealing-the-african-presence-in-renaissance-europe

revealing-the-african-presence-in-renaissance-europe

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

eveal<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>african</strong> <strong>presence</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>renaissance</strong> <strong>europe</strong>

RT R

eveal<strong>in</strong>he AfricaPresence enaissan Europeedited byJoaneath Spicercontributions byNatalie Zemon DavisKate LoweJoaneath SpicerBen V<strong>in</strong>son III<strong>reveal<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>african</strong> <strong>presence</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>renaissance</strong> <strong>europe</strong><strong>the</strong> walters art museum

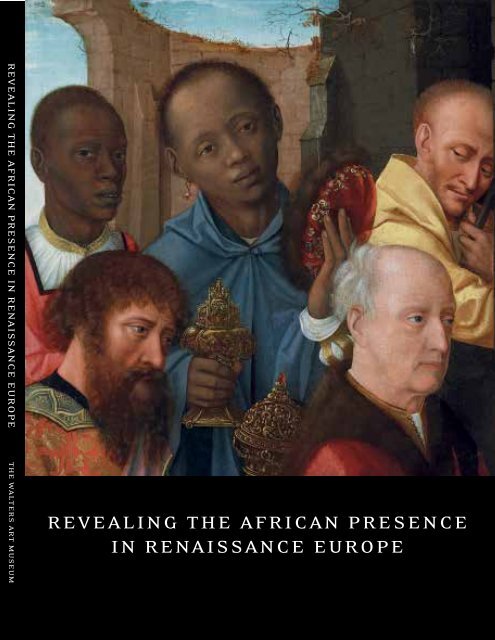

This publication has been generously supportedby <strong>the</strong> Robert H. and Clarice Smith Publication FundPublished by <strong>the</strong> Walters Art Museum, Baltimore© 2012 Trustees of <strong>the</strong> Walters Art GalleryThird pr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g, 2013All rights reserved.No part of <strong>the</strong> contents of this book may be reproduced,stored <strong>in</strong> a retrieval system, or transmitted <strong>in</strong> any formor by any means, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g photocopy, record<strong>in</strong>g, or o<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>formation and retrieval systems without <strong>the</strong> writtenpermission of <strong>the</strong> Trustees of <strong>the</strong> Walters Art Gallery.This publication accompanies <strong>the</strong> exhibition Reveal<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> African Presence <strong>in</strong> Renaissance Europe, held at <strong>the</strong>Walters Art Museum from October 14, 2012, to January 21,2013, and at <strong>the</strong> Pr<strong>in</strong>ceton University Art Museum fromFebruary 16 to June 9, 2013.This exhibition is supported by a grant from <strong>the</strong> NationalEndowment for <strong>the</strong> Humanities and by an <strong>in</strong>demnityfrom <strong>the</strong> Federal Council on <strong>the</strong> Arts and Humanities.Library of Congress Catalog<strong>in</strong>g-<strong>in</strong>-Publication DataReveal<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> African <strong>presence</strong> <strong>in</strong> RenaissanceEurope/edited by Joaneath Spicer ; contributions byNatalie Zemon Davis, Kate Lowe, Joaneath Spicer, BenV<strong>in</strong>son III ; The Walters Art Museum.p. cm.“This publication accompanies <strong>the</strong> exhibition Reveal<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> African Presence <strong>in</strong> Renaissance Europe, heldat <strong>the</strong> Walters Art Museum from October 14, 2012, toJanuary 21, 2013, and at <strong>the</strong> Pr<strong>in</strong>ceton University ArtMuseum from February 16 to June 9, 2013.”Includes bibliographical references.ISBN 978-0-911886-78-81. Africans <strong>in</strong> art—Exhibitions. 2. Blacks <strong>in</strong> art—Exhibitions. 3. Art, Renaissance—Exhibitions. 4. Blacks—Europe—History—16th century—Exhibitions. I. Spicer,Joaneath A. (Joaneath Ann) II. Davis, Natalie Zemon,1928– III. Lowe, K. J. P. IV. V<strong>in</strong>son, Ben, III. V. Walters ArtMuseum (Baltimore, Md.) VI. Pr<strong>in</strong>ceton University. ArtMuseum.N8232.R48 2012704.94209409031—dc23 2012018607All dimensions are <strong>in</strong> centimeters; height precedes widthprecedes depth unless o<strong>the</strong>rwise <strong>in</strong>dicated.The Walters Art Museum600 North Charles StreetBaltimore, Maryland 21201<strong>the</strong>walters.orgProduced by Marquand Books, Seattlemarquand.comDesigned and typeset by Susan E. KellyTypeset <strong>in</strong> Eidetic Modern, Eidetic Neo, and Voluta ScriptProofread by Carrie WicksColor management by iocolor, SeattlePr<strong>in</strong>ted and bound <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a by Artron Color Pr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g Co.cover and page 118 Workshop of Gerard David, Adorationof <strong>the</strong> K<strong>in</strong>gs (no. 1), detailpage 2 Domenico T<strong>in</strong>toretto, Portrait of a Man (no. 65)page 6 Girolamo da Santacroce, Adoration of <strong>the</strong> K<strong>in</strong>gs(no. 24)page 12 Chafariz d’el Rey <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Alfama District (no. 47),detailpage 34 Jan Muller, after Hendrick Goltzius, The First Day(Dies 1) (no. 38)page 60 Habits des habitans du Caire, from Leo Africanus,Historiale description de l’Afrique (no. 19)page 80 Portrait of a Wealthy African (no. 61)page 98 Andrés Sánchez Galque, Los tres mulatos deEsmeraldas (no. 77)

Director’s forewordReveal<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> African Presence <strong>in</strong> RenaissanceEurope <strong>in</strong>vites visitors to explore <strong>the</strong> varied rolesand societal contributions of Africans and <strong>the</strong>irdescendents <strong>in</strong> Renaissance Europe as revealed<strong>in</strong> compell<strong>in</strong>g pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>gs, draw<strong>in</strong>gs, sculpture,and pr<strong>in</strong>ted books of <strong>the</strong> period. The story of <strong>the</strong>Renaissance with its renewed focus on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividualis often told, but this project seeks a differentperspective, to understand <strong>the</strong> period <strong>in</strong> terms of<strong>in</strong>dividuals of African ancestry, whom we encounter<strong>in</strong> arrest<strong>in</strong>g portrayals from life, testify<strong>in</strong>g to<strong>the</strong> Renaissance adage that portraiture magicallymakes <strong>the</strong> absent present. We beg<strong>in</strong> with slaves,mov<strong>in</strong>g up <strong>the</strong> social ladder to farmers, artisans,aristocrats, scholars, diplomats, and rulers fromdifferent parts of <strong>the</strong> African cont<strong>in</strong>ent. Whilemany <strong>in</strong>dividuals can be identified, <strong>the</strong> names ofmost slaves and freed men and women are lost.Recogniz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> traces of <strong>the</strong>ir existence <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>art of <strong>the</strong> time and, where possible, <strong>the</strong>ir achievementsis one way of restor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir identities.The exhibition, conceived by Joaneath Spicer,James A. Murnaghan Curator of Renaissanceand Baroque Art at <strong>the</strong> Walters Art Museum, and<strong>the</strong> programs accompany<strong>in</strong>g it are an expressionof <strong>the</strong> engagement of <strong>the</strong> Walters, throughour collections and programm<strong>in</strong>g, with <strong>the</strong> AfricanAmerican community <strong>in</strong> Baltimore to createan <strong>in</strong>creased sense of a shared heritage and of<strong>the</strong> museum’s commitment to serv<strong>in</strong>g diverseaudiences, to which our second venue, Pr<strong>in</strong>cetonUniversity Art Museum, subscribes as well. Themuseum’s extensive collection of Renaissanceart, among <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>est <strong>in</strong> America, contributes substantiallyto <strong>the</strong> exhibition’s object list, and <strong>the</strong>exhibition’s <strong>in</strong>terpretive approach builds on <strong>the</strong>approach embedded <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Walters’ permanent<strong>in</strong>stallation of a late Renaissance “Chamber of Artand Wonders,” also conceived by Dr. Spicer, whichunderscores <strong>the</strong> cultural exchange among Europe,Asia, and Africa <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Age of Exploration.A project of this scope and ambition could nothave happened without <strong>the</strong> generous support ofmany <strong>in</strong>stitutions and <strong>in</strong>dividuals, first of all <strong>the</strong>Pr<strong>in</strong>ceton University Art Museum.We are deeply grateful to <strong>the</strong> many donorswho made <strong>the</strong> exhibition possible at <strong>the</strong> Walters,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Richard C. von Hess Foundation, <strong>the</strong>National Endowment for <strong>the</strong> Arts, <strong>the</strong> NationalEndowment for <strong>the</strong> Humanities, <strong>the</strong> Bernard Family,Christie’s, Andie and Jack Laporte, KathrynCoke Rienhoff, Lynn and Philip Rauch, <strong>the</strong> MarylandHumanities Council, Cynthia Alderdice, JoelM. Goldfrank, and o<strong>the</strong>r generous <strong>in</strong>dividuals.This publication is made possible by <strong>the</strong> Robert H.and Clarice Smith Publication Fund. The exhibitionis supported by an <strong>in</strong>demnity from <strong>the</strong> FederalCouncil on <strong>the</strong> Arts and Humanities.Gary VikanThe Walters Art Museum7

<strong>in</strong>troductionjoaneath spicerThe value placed on <strong>the</strong> identity and perspective of<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual may be one of <strong>the</strong> chief legacies of <strong>the</strong>European Renaissance to Western culture, but thatattention expanded to encompass those outside <strong>the</strong>cultural elites only very gradually and imperfectly.Given <strong>the</strong> conventionalized treatment of o<strong>the</strong>r marg<strong>in</strong>alizedgroups of <strong>the</strong> time such as peasants, <strong>the</strong>material available for illum<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> lives of <strong>in</strong>dividualAfricans <strong>in</strong> Renaissance Europe through <strong>the</strong>visual arts is considerable, though little known to<strong>the</strong> wider public. The focus here is on Africans liv<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> or visit<strong>in</strong>g Europe <strong>in</strong> what has been called <strong>the</strong>long sixteenth century, from <strong>the</strong> 1480s to around1610. The exhibition and essays seek to draw out notonly <strong>the</strong>ir physical <strong>presence</strong> but <strong>the</strong>ir identity andparticipation <strong>in</strong> society, as well as <strong>the</strong> challenges,prejudices, and <strong>the</strong> opportunities <strong>the</strong>y encountered.Address<strong>in</strong>g this rich material <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context of apublic exhibition offers <strong>the</strong> possibility to encouragebroad public discussion of <strong>the</strong> larger issues ofshared heritage—as well as those of race, color, andidentity—through <strong>the</strong> vehicle of great art.The exhibition experience is built around twoma<strong>in</strong> sections. Section 1 addresses conditions thatframe <strong>the</strong> lives of Africans <strong>in</strong> Europe—slavery andsocial status, perceptions of Africa, <strong>the</strong> representationof Africans <strong>in</strong> Christian art, blackness andcultural difference, as well as <strong>the</strong> aes<strong>the</strong>tic appreciationof blackness. Then <strong>in</strong> Section 2 <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividuals<strong>the</strong>mselves come to <strong>the</strong> fore—often through portrayalsfrom life—first as slaves and servants, followedby <strong>the</strong> surpris<strong>in</strong>gly wide range of free and freedAfricans liv<strong>in</strong>g ord<strong>in</strong>ary lives, and f<strong>in</strong>ally Africandiplomats <strong>in</strong> Europe and African rulers, present <strong>in</strong>Europe through <strong>the</strong>ir portraits commissioned forgreat pr<strong>in</strong>cely collections, images that may assertcultural difference and a keen understand<strong>in</strong>g ofself-representation <strong>in</strong> a way denied to o<strong>the</strong>rs. Theexhibition ends with <strong>the</strong> mesmeriz<strong>in</strong>g figure ofSt. Benedict <strong>the</strong> Moor, <strong>the</strong> Renaissance African-European with <strong>the</strong> greatest impact today.The orig<strong>in</strong> of <strong>the</strong> project was research undertaken<strong>in</strong> 2000 <strong>in</strong> response to a query as to <strong>the</strong>museum’s position on <strong>the</strong> conflict<strong>in</strong>g claims concern<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> identity of <strong>the</strong> child <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Walters’pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g by Jacopo Pontormo, <strong>the</strong>n called Portraitof Maria Salviati and a Child, datable to ca. 1539(no. 64). Formulat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> wider issues from <strong>the</strong> perspectiveof her identity and <strong>in</strong>deed <strong>the</strong> nature of<strong>the</strong> public response to that identity has <strong>in</strong>formed<strong>the</strong> current exhibition project. The parameters ofresearch were altered by a “game-chang<strong>in</strong>g” conferenceorganized at Oxford University (2001) by KateLowe and Thomas Earle, “Black Africans <strong>in</strong> RenaissanceEurope.” Over time it became clear that <strong>the</strong>rewere more than enough evocative, potentially borrowableobjects to create an exhibition that couldgenerate public conversation on racial identity. TheAmsterdam exhibition Black Is Beautiful (2008)raised important questions that cont<strong>in</strong>ue to benefit<strong>the</strong> field, and The Image of <strong>the</strong> Black <strong>in</strong> Western Artproject, edited by David B<strong>in</strong>dman and Henry LouisGates, Jr., and now generously hosted by <strong>the</strong> DuBoisInstitute at Harvard University, has become a majorforce. Never<strong>the</strong>less, by adopt<strong>in</strong>g an approach highlight<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> roles of <strong>in</strong>dividuals of African descent8

or Slavic orig<strong>in</strong>. The result was a grow<strong>in</strong>g African<strong>presence</strong> <strong>in</strong> Europe, some of <strong>the</strong> evidence forwhich is found exclusively <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> visual arts. Forexample, <strong>the</strong> dist<strong>in</strong>ctly <strong>in</strong>dividualized portraits oftwo black men <strong>in</strong>corporated by Gerard David <strong>in</strong>tohis Adoration of <strong>the</strong> K<strong>in</strong>gs (no. 1, cover), establish<strong>the</strong>ir <strong>presence</strong> <strong>in</strong> Antwerp around 1515, probably<strong>in</strong>itially as slaves of Portuguese merchants, as wasKathar<strong>in</strong>a (no. 55), drawn <strong>the</strong>re <strong>in</strong> 1521. However,to round out <strong>the</strong>ir lives, <strong>the</strong>ir probable manumission(slavery had no legal stand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands),we will need more than <strong>the</strong> few archivaldocuments presently known.Conditions rema<strong>in</strong>ed largely stable until <strong>the</strong>early 1600s, allow<strong>in</strong>g (with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> constra<strong>in</strong>ts of<strong>in</strong>gra<strong>in</strong>ed prejudice) for a gradually more nuancedview of blackness and of persons of African ancestryas well as for more varied roles for <strong>the</strong>m andespecially for <strong>the</strong>ir children with<strong>in</strong> society. Forreasons that are not entirely clear, around 1608–10<strong>the</strong>re occurred a series of political and cultural“events” <strong>in</strong> disparate locations that each <strong>in</strong> its ownway seemed to signal a new level of acceptanceand status for Africans <strong>in</strong> Europe, to pick four:<strong>the</strong> elaborate arrangements made by Pope Paul Vto receive <strong>the</strong> Congolese ambassador known <strong>in</strong>Europe as Antonio Manuel, Marquis of Na Vunda(who, however died upon arrival, see Lowe, “Ambassadors,”pp. 104–5, and fig. 46); Morocco and <strong>the</strong>Dutch Republic sign a landmark treaty establish<strong>in</strong>gtrade relations, <strong>the</strong> first between a Europeancountry and a non-Christian one; <strong>the</strong> Spanishplaywright Enciso writes a play celebrat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>life of <strong>the</strong> black humanist Juan Lat<strong>in</strong>o; Philip III ofSpa<strong>in</strong> orders a silver casket for <strong>the</strong> bones of Benedict<strong>the</strong> Moor (canonized <strong>in</strong> 1807). However, while<strong>the</strong>se events may appear to presage a new era ofnormalization, with <strong>the</strong> perspective of time <strong>the</strong>ylook more like markers of <strong>the</strong> end of an era.In <strong>the</strong> 1600s, <strong>the</strong> focus of European attentionshifted toward <strong>the</strong> Americas and Asia, whileever-<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g demands for cheap labor, especially<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> American colonies, meant that slaverybecame specifically associated with blackAfricans as it had not been <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> past. With familiarity,<strong>the</strong> exotic o<strong>the</strong>rness of “Africa,” her “astonish<strong>in</strong>gnovelty” so vividly highlighted <strong>in</strong> Mart<strong>in</strong> deVos’s 1589 Allegory of Africa (no. 2, from a series of<strong>the</strong> Four Cont<strong>in</strong>ents)2 and its accompany<strong>in</strong>g poem,becomes simply <strong>the</strong> “o<strong>the</strong>r” and more commonlysubject to exploitation. While <strong>the</strong> poem cites “<strong>the</strong>eternal pyramids” as <strong>the</strong> manifestation of this“novelty,” <strong>the</strong> composition balances <strong>the</strong> mentalachievement of <strong>the</strong> past <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> form of pyramids(actually obelisks are depicted, <strong>in</strong> a typical confusionof <strong>the</strong> time) with perceived extra-ord<strong>in</strong>arystrangeness and savagery of <strong>the</strong> present, manifested<strong>in</strong> a w<strong>in</strong>ged serpent and to <strong>the</strong> rear, nakednatives stand<strong>in</strong>g before caves.Indeed, this ambivalence toward forces beyondcontrol is a thread runn<strong>in</strong>g through many aspectsof Europeans’ perceptions of Africa, whe<strong>the</strong>r it is<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>credible ferocity of <strong>the</strong> “monstrous” crocodile,assumptions about exaggerated sexuality,or <strong>the</strong> vast sterility of <strong>the</strong> Sahara: to Europeansit was all extraord<strong>in</strong>ary <strong>in</strong> its excess. For Renaissanceartists and authors, Cleopatra VII of Egyptexemplified <strong>the</strong> dangers of excess <strong>in</strong> high places.Her life as pharaoh, with its cast of Roman emperorsand generals subjected to dramatic twists offate and emotional pathos, was perfectly suited to<strong>the</strong> revived <strong>the</strong>atrical genre of classical tragedy as<strong>in</strong> Cléopâtre Captive (1552–53) by Étienne Jodelle3or Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra (by 1608).4In <strong>the</strong> arts she was rarely <strong>the</strong> resourceful ruler buta voluptuously beautiful woman (often nude) committ<strong>in</strong>gsuicide follow<strong>in</strong>g that of her lover MarkAntony.5 In a lovely bronze statuette by NiccolòRoccatagliata (no. 22),6 Cleopatra leans <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong>asp’s embrace, <strong>the</strong> dramatic undulations of <strong>the</strong>poisonous snake underscor<strong>in</strong>g her destructivesexuality by referenc<strong>in</strong>g Eve’s fall. Perhaps <strong>the</strong>10

11<strong>in</strong>troductionmedium played a role. The color of Cleopatra’ssk<strong>in</strong> is not known, but she apparently had Egyptianblood as well as Greek.7 Renaissance pa<strong>in</strong>tersand playwrights generally represented her asEuropean, but Shakespeare has her describe herselfas “with Phoebus’s amorous p<strong>in</strong>ches black[blackened by <strong>the</strong> rays of <strong>the</strong> sun god PhoebusApollo]” while Antony’s friend Philo refers to heras “tawny,” <strong>in</strong> a passage imply<strong>in</strong>g an alignment ofdarker sk<strong>in</strong> with sexuality.The tendency to emphasize <strong>the</strong> baser natures offamous men and women of <strong>the</strong> African past helpsto illum<strong>in</strong>ate a taste of Italian scholars and <strong>in</strong>kwellsand oil lamps (nos. 8, 9) for <strong>the</strong> worktablemade amus<strong>in</strong>gly <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> shape of <strong>the</strong> head of anAfrican slave, imitat<strong>in</strong>g utility vessels of antiquity.The ev<strong>in</strong>ce casual disregard, whe<strong>the</strong>r beautifullyor crudely modeled. So for <strong>the</strong> Renaissancecollector, African exoticism had multiple sides:It would prompt disda<strong>in</strong> as well as profound fasc<strong>in</strong>ation(for which see <strong>the</strong> essay on blackness,pp. 35–59).The immensity, voluptuous strangeness, andseem<strong>in</strong>g unknowability of this cont<strong>in</strong>ent so closeand yet so far from Europe offered a fundamentalchallenge to Europeans <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1500s. Representationsevok<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>se qualities would unavoidably<strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>the</strong>ir perception of people of visibly Africanancestry <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir midst.notes1. On <strong>the</strong> atlas, see Paul B<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g, Imag<strong>in</strong>ed Corners: Explor<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> World’s First Atlas (London: Review, 2003), www.orteliusmaps.com/ort_background.html.2. Ann Diels and Marjole<strong>in</strong> Leesberg, The Collaert Dynasty,part VI, The New Hollste<strong>in</strong> Dutch and Flemish Etch<strong>in</strong>gs,Engrav<strong>in</strong>gs and Woodcuts, 1450–1700 (Rotterdam: Sound& Vision Publishers <strong>in</strong> cooperation with <strong>the</strong> Rijksprentenkab<strong>in</strong>et,Rijksmuseum, 1993–[2005]): no. 1316.3. For Jodelle’s play, see E. Balmas and M. Dassonville, eds.,La tragédie à l’époque d’Henri II et de Charles IX (Paris:Olschki, 1986); Charles Mazouer, Le théâtre français dela Renaissance (Paris: Champion, 2002). O<strong>the</strong>r plays of<strong>the</strong> period <strong>in</strong>clude François Rabelais, Cléopâtre dansl’Hadès (1553); Robert Garnier, Marc-Anto<strong>in</strong>e (ca. 1578);Mary Sidney, The Tragedy of Antonie (ca. 1592); Nicolas deMontreux, Cléopâtre (1594).4. See Ania Loomba, Shakespeare, Race, and Colonialism(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).5. On Cleopatra <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> art of <strong>the</strong> Renaissance, see Cél<strong>in</strong>eRichard-Jamet, “Cléopâtre: Femme forte or femme fatale?Une place equivoque dans les galleries de ‘femmes fortes’aux XVIe et XVIIe siècles,” <strong>in</strong> Cléopâtra dans le miroir del’art occidental, ed. Claude Ritschard and Allison Morehead,exh. cat. (Geneva, Musée Rath, 2004), 37–52; PhilippeBoyer, “Cléopâtre vs. Lucrèce: Du suicide comme vecteurde rapprochement,” <strong>in</strong> ibid., 53–57; Brian A. Curran, “Cleopatraand <strong>the</strong> Second Julius: Egypt and <strong>the</strong> Dream of Empire<strong>in</strong> High Renaissance Rome,” <strong>in</strong> The Egyptian Renaissance:The Afterlife of Ancient Egypt <strong>in</strong> Early ModernItaly (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 167–87.The <strong>in</strong>formative range of images <strong>in</strong> Cléopâtra dans leMiroir de l’Art does not really address portraiture, smallsculpture, or <strong>the</strong> decorative arts, so attention may becalled to Venetian, Portrait of an Unidentified Woman asCleopatra (ca. 1580?), Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (acc.no. 37.534); Pier Jacopo Alari Bonacolsi, called Antico, Bustof Cleopatra (1519–20), bronze, Museum of F<strong>in</strong>e Arts, Boston(acc. no. 64.2174); Severo da Ravenna, Cleopatra Committ<strong>in</strong>gSuicide (1530?), bronze, Metropolitan Museum ofArt, New York (10.9.2). Francesco Xanto Avelli, Dish withMarc Antony and Cleopatra (1542), maiolica, Museum ofF<strong>in</strong>e Arts, Boston (acc. no. 95.371).6. Manfred Lei<strong>the</strong>-Jasper is prepar<strong>in</strong>g a publication onthis piece to appear <strong>in</strong> 2012.7. The Ptolemies married with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir own (Greek) family,but Cleopatra’s fa<strong>the</strong>r’s mo<strong>the</strong>r was apparently an Egyptianfrom elite circles, so Cleopatra had Egyptian blood.She was <strong>the</strong> first of her dynasty to study and use <strong>the</strong>Egyptian language. See Susan Walker and Peter Higgs,eds., Cleopatra of Egypt: From History to Myth (Pr<strong>in</strong>ceton:Pr<strong>in</strong>ceton University Press, 2001), especially <strong>the</strong> citationfrom Plutarch on her appearance (210), and portraits nowthought to be her, most prom<strong>in</strong>ently no. 198, a marbleportrait from <strong>the</strong> Staatliche Museum, Berl<strong>in</strong>, which is consistentwith <strong>the</strong> summary portraits on her co<strong>in</strong>s. Gün<strong>the</strong>rHöbl, A History of <strong>the</strong> Ptolemaic Empire (London: Routledge,2001), 223, 231–56.

The Lives of African Slavesand People of African Descent<strong>in</strong> Renaissance Europekate loweThe first questions are: Who were <strong>the</strong> slaves <strong>in</strong>Europe <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Renaissance and where did <strong>the</strong>ycome from? Was <strong>the</strong>re a change over time <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>period from 1400 to 1600? There were two ma<strong>in</strong>routes by which enslaved Africans were brought toEurope: from <strong>the</strong> eastern Mediterranean or NorthAfrica, and from <strong>the</strong> west coast of Africa. But,with <strong>the</strong> exception of Spa<strong>in</strong>, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mid-fifteenthcentury before <strong>the</strong> commencement of <strong>the</strong> slavetrade from West Africa, only a small percentageof slaves <strong>in</strong> Europe were African; <strong>the</strong> vast majoritywere from <strong>the</strong> eastern Mediterranean, Russia, orCentral Asia. Dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Renaissance, slavery wasnot just a black phenomenon—slaves <strong>in</strong> Europewere both “white” and “black.” Europe had a longhistory of white slavery. There was mass whiteslavery <strong>in</strong> Europe before <strong>the</strong>re was black slavery,1and white slavery cont<strong>in</strong>ued after <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>flux ofblack slaves from sub-Saharan Africa <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> fifteenth,sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries, sothat often white and black slaves worked alongsideeach o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> same households or on <strong>the</strong>same properties. Because of its ancient settlementand diverse civilizations, European society <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>Renaissance was fractured and complex, and thishad consequences for <strong>the</strong> variety of ways <strong>in</strong> whichslavery developed.Slavery <strong>in</strong> fifteenth- and sixteenth-centuryEurope was usually not for life; <strong>in</strong>stead, on <strong>the</strong>death of a master or mistress, ei<strong>the</strong>r a slave wasfreed or a set period of fur<strong>the</strong>r enslavement was13

fixed. In Europe, a future freed life for slaves wasenvisaged, and consequently slaves always lived <strong>in</strong>hope that <strong>the</strong>y would be freed from bondage. Manumission,or <strong>the</strong> free<strong>in</strong>g of slaves, was a dist<strong>in</strong>ctprobability. The mechanism for this was normallyconta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> a will, where futures for slaves weremapped out, and where money was bequea<strong>the</strong>d formarriage, for sett<strong>in</strong>g up house, or for enabl<strong>in</strong>g aformer slave to make a liv<strong>in</strong>g. Clo<strong>the</strong>s and possessionswere also bequea<strong>the</strong>d. At its simplest andsmoo<strong>the</strong>st, <strong>the</strong>refore, slavery <strong>in</strong> Europe dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>Renaissance can be seen as just a stage <strong>in</strong> a life andnot a life sentence. As a result of this process ofbe<strong>in</strong>g freed with<strong>in</strong> a generation, and of hav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>possibility of <strong>in</strong>tegration, freed and free Africanswere socially mobile and very quickly appeared <strong>in</strong>professional and creative positions <strong>in</strong> Europe. Thelate fifteenth and sixteenth centuries saw <strong>the</strong> firstblack lawyers, <strong>the</strong> first black churchmen, <strong>the</strong> firstblack schoolteachers, <strong>the</strong> first black authors, and<strong>the</strong> first black artists.2 Superficially at least, <strong>the</strong>black African depicted <strong>in</strong> European dress by JanMostaert (see fig. 39) had been “Europeanized”through his acquisition of European accessoriessuch as a sword and <strong>the</strong> hat badge from a Christianshr<strong>in</strong>e, and he may have been an ambassadoror held a position at a European court.3 The sonof a black African slave couple <strong>in</strong> Europe <strong>in</strong> thisperiod even achieved sa<strong>in</strong>thood: <strong>the</strong> first blackEuropean sa<strong>in</strong>t, San Benedetto (St. Benedict,known as “il moro” or <strong>the</strong> Moor) lived <strong>in</strong> Sicily <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> sixteenth century, although he was not canonizeduntil 1807.4 “Moor” is an imprecise word that<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sixteenth century had been divested of itsorig<strong>in</strong>al religious mean<strong>in</strong>g of a Muslim, to becomea generic word most usually applied to an Africanor someone from <strong>the</strong> Ottoman empire. The worddoes not carry any <strong>in</strong>dication of ethnicity or sk<strong>in</strong>color: ra<strong>the</strong>r, fur<strong>the</strong>r descriptors labeled peopleas white moors, brown or tawny moors, and blackmoors.differentiat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> status of<strong>african</strong>s <strong>in</strong> representationsThe practice <strong>in</strong> Renaissance Europe of manumitt<strong>in</strong>gslaves dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir lifetimes had importantconsequences for <strong>the</strong> representation of Africans<strong>in</strong> whatever media <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Renaissance. AlthoughAfrican—especially black African—attendants andbystanders <strong>in</strong> European depictions (except <strong>in</strong> someparts of Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Europe) are usually assumed tobe slaves, <strong>in</strong> most cases legal status is not apparentand cannot be discerned from an image. InVenice, a niche occupation for freed black Africansexisted, l<strong>in</strong>ked to <strong>the</strong>ir prior skills as slaves, andpossibly also to <strong>the</strong>ir prior lives <strong>in</strong> West Africa:that of gondolier. 5 Two iconic Venetian Renaissancepa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>gs, Vittore Carpaccio’s Miracle of<strong>the</strong> True Cross at <strong>the</strong> Rialto Bridge, also known asThe Heal<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> Possessed Man, of 1494, which<strong>in</strong>cludes two black gondoliers, and his Hunt<strong>in</strong>g on<strong>the</strong> Lagoon of ca. 1490–95 (fig. 2), which <strong>in</strong>cludesa couple of black boatmen, show black Africansat work <strong>in</strong> water activities, but <strong>the</strong>re is no way oftell<strong>in</strong>g whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>y are enslaved or free. 6 Africans<strong>in</strong> Renaissance representations could be ei<strong>the</strong>rslaves, freedmen (that is, ex-slaves), or freemen(that is, people who had never been slaves, butone or both of whose parents probably had been).This latter category could have <strong>in</strong>cluded people ofpart-African ancestry, who had only one Africanparent, of whom with<strong>in</strong> a generation <strong>the</strong>re was asignificant number. In most cases, especially <strong>in</strong>representations of African heads, <strong>the</strong> legal statusof <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual depicted was beside <strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t; <strong>in</strong>a few cases, <strong>the</strong> artist wished to ensure that <strong>the</strong>viewer understood that <strong>the</strong> African was a slave,and so <strong>in</strong>cluded cha<strong>in</strong>s, manacles, or a slave collar.A small Italian cast-iron head of a bearded blackslave wear<strong>in</strong>g a slave collar from <strong>the</strong> second half of<strong>the</strong> sixteenth century (no. 52) is ra<strong>the</strong>r surpris<strong>in</strong>g,as most depictions of slaves <strong>in</strong> slave collars, which14

15<strong>the</strong> lives of <strong>african</strong> slaves and people of <strong>african</strong> descent <strong>in</strong> <strong>renaissance</strong> <strong>europe</strong>could be highly decorated, expensive pieces of jewelry,are from a later period. Leg irons and manacleswere usually used as a form of punishmentafter a slave had attempted to run away or when itwas suspected that <strong>the</strong>y would abscond if a chancearose; cha<strong>in</strong>s were not rout<strong>in</strong>ely employed. NorthAfrican Muslims, some of whom would have beencaptured <strong>in</strong> war, were placed <strong>in</strong> cha<strong>in</strong>s more frequentlythan sub-Saharan Africans. The Germanartist Christoph Weiditz from Strasbourg compileda costume book <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1520s and 1530s thatrecorded <strong>the</strong> dress and habits of people, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gslaves, <strong>in</strong> Spa<strong>in</strong> and <strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands. White galleyslaves and black slaves load<strong>in</strong>g water onto shipsfig. 2 Vittore Carpaccio (Italian, ca. 1460–ca. 1526),Hunt<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> Lagoon, ca. 1490–95. Oil on panel,75.6 × 63.8 cm. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles(79.pb.72)

left fig. 3 Black slave with a w<strong>in</strong>esk<strong>in</strong>, from ChristophWeiditz, Das Trachtenbuch (1529). Ink on paper. GermanischesNationalmuseum, Nuremberg (Hs 22474, fol 22v)above fig. 4 Characters, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> slave Ethiopissa,from Publius Terentius Afer, Comoediae (Strassbourg:Johan Gruen<strong>in</strong>ger, 1499). Ink on paper. The Walters ArtMuseum, Baltimore (91.1155, fol. 39v [detail])appear wear<strong>in</strong>g leg irons, and a black slave <strong>in</strong> Castilehas leg irons around both ankles and a heavycha<strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g one of <strong>the</strong>m to his waist (fig. 3). In<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>scription accompany<strong>in</strong>g this last image, it isexpla<strong>in</strong>ed that <strong>the</strong> cha<strong>in</strong> signifies that <strong>the</strong> wearerhas already attempted an escape.7 Includ<strong>in</strong>g an<strong>in</strong>scription or explanatory panel was ano<strong>the</strong>rroute by which artists could ensure that <strong>the</strong> viewerunderstood that <strong>the</strong> African depicted was a slave.For example, <strong>the</strong> black female slave designated by<strong>the</strong> label Ethiopissa <strong>in</strong> a German woodcut illustrat<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> list of characters <strong>in</strong> a 1499 edition ofTerence’s play The Eunuch (fig. 4) is a slave. Useof <strong>the</strong> word Ethiops or one of its variations <strong>in</strong> thisperiod simply <strong>in</strong>dicates that <strong>the</strong> person is a blackAfrican; it does not <strong>in</strong>dicate that <strong>the</strong> person camefrom Ethiopia.As far as representations of slaves are concerned,ancient historians have isolated factorssuch as smallness of stature, shortness of hair,and posture of <strong>the</strong> body that <strong>the</strong>y claim denotedslaves <strong>in</strong> representations from ancient Greece,8but it is not possible to do this <strong>in</strong> RenaissanceEurope. Occasionally, <strong>the</strong> depressed or despair<strong>in</strong>gexpression of <strong>the</strong> African <strong>in</strong>dicates that <strong>the</strong> persondepicted was probably a slave. This is <strong>the</strong> casewith <strong>the</strong> portrait <strong>in</strong> silverpo<strong>in</strong>t by Albrecht Dürerof a young black African woman called Kathar<strong>in</strong>a(no. 55), whom Dürer encountered <strong>in</strong> Antwerp <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> house of one of his patrons, <strong>the</strong> Portuguesefactor João Brandão. Described by Dürer <strong>in</strong> hisdiary as Brandão’s Mohr<strong>in</strong>, or Moor,9 she was veryprobably his slave ra<strong>the</strong>r than simply his servant,although as we shall see, slavery was not legal <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> Low Countries,10 and <strong>the</strong> word does not conveyany legal mean<strong>in</strong>g. Kathar<strong>in</strong>a was black, as isshown by Dürer’s draw<strong>in</strong>g, but his diary entry doesnot make this clear. Dürer himself <strong>in</strong>scribed <strong>the</strong>

17<strong>the</strong> lives of <strong>african</strong> slaves and people of <strong>african</strong> descent <strong>in</strong> <strong>renaissance</strong> <strong>europe</strong>fig. 5 Albrecht Dürer (German,1471–1528), Portrait Study of a BlackMan, 1508? Charcoal on paper. Albert<strong>in</strong>a,Vienna (A. Dürer <strong>in</strong>v. 3122)year, her name, and her age—twenty years old—on<strong>the</strong> draw<strong>in</strong>g, so <strong>the</strong>se are not <strong>in</strong> doubt. Kathar<strong>in</strong>a’s<strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>itely faraway expression, her downcast eyes,and her hair cover<strong>in</strong>g are mov<strong>in</strong>gly captured byDürer. The artist also drew a second black African,a man, at around <strong>the</strong> same date (fig. 5). Although<strong>the</strong> date “1508” appears on <strong>the</strong> draw<strong>in</strong>g, alongsideDürer’s monogram, <strong>the</strong> date is not consideredsecure. Noth<strong>in</strong>g is known of this man, andit could be that he is <strong>the</strong> Diener or servant of <strong>the</strong>same João Brandão whom Dürer writes he drewafter 14 December 1520. With a moustache andbeard <strong>in</strong> addition to close, curly hair, this Africanis less likely to have been a slave than Ka<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>a,as beards were usually forbidden to slaves, and hisexpression is less obviously despair<strong>in</strong>g.The position of <strong>the</strong> African <strong>in</strong> a scene visà-viso<strong>the</strong>r humans can also suggest <strong>in</strong>feriority,as <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> case with <strong>the</strong> young black childrenwho were so prized at European courts, and whowere sometimes pa<strong>in</strong>ted alongside <strong>the</strong>ir ownersor masters/mistresses, as <strong>in</strong> Titian’s portraitof Laura dei Dianti of ca. 1523 (fig. 6)11 and Cristóvãode Morais’s portrait of Juana of Austria of1555 (fig. 7).12 The black boy and girl are considerablysmaller than <strong>the</strong>ir mistresses, as <strong>the</strong>y are

18fig. 6 Titian (signed on sleeve“titi” “anus” “f”) (Italian,1488–1576), Portrait of Lauradei Dianti, ca. 1523. Oil on canvas,118 × 93.4 cm. Collection He<strong>in</strong>zKisters, Kreuzl<strong>in</strong>gen, Switzerlandfig. 7 Christóvão de Morais(Portuguese, active 1551–73),Portrait of Juana of Austria,1535–73, daughter of Charles V,1555. Oil on canvas, 99 × 81.5 cm.Musées royaux des Beaux-Artsde Belgique, Brussels (1296)

19<strong>the</strong> lives of <strong>african</strong> slaves and people of <strong>african</strong> descent <strong>in</strong> <strong>renaissance</strong> <strong>europe</strong>children, and <strong>the</strong>ir smallness of stature makes<strong>the</strong>m vulnerable and unimportant. However, <strong>the</strong>sechildren were not necessarily slaves, althoughmost of <strong>the</strong>m probably were; sometimes wholeblack families of free people were lured to <strong>the</strong>courts to work, <strong>in</strong> order that suitably young andattractive black children could be available toserve.13 In group scenes <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g both white andblack people, black Africans often appear <strong>in</strong> verymarg<strong>in</strong>al or lim<strong>in</strong>al positions, but once aga<strong>in</strong> thiscannot be taken as an <strong>in</strong>dication of legal ra<strong>the</strong>rthan social status.<strong>the</strong> lives of slavesSlavery <strong>in</strong> Europe was very much an urban phenomenon,and as a consequence, many slavesfound <strong>the</strong>mselves liv<strong>in</strong>g as ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> only slaveor one of two or three <strong>in</strong> a household. Householdswere often composed of both slaves and differ<strong>in</strong>gtypes of servants. Only very occasionallywould large groups of Africans have been ableto congregate <strong>in</strong> a European city, but one site <strong>in</strong>Lisbon provided just such an opportunity. Lisbonhad <strong>the</strong> greatest percentage of black people <strong>in</strong>Europe at this time, with perhaps 10 percent of <strong>the</strong>population be<strong>in</strong>g black.14 In an anonymous, latesixteenth-century pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> Lisbon waterfront,a probably Ne<strong>the</strong>rlandish artist has depicted<strong>the</strong> great concentration of black people of all socialand legal statuses, from slaves carry<strong>in</strong>g water topetty crim<strong>in</strong>als to knights, to be found around<strong>the</strong> Chafariz d’el Rey, <strong>the</strong> k<strong>in</strong>g’s water founta<strong>in</strong>(fig. 8, and no. 47).15 This genre scene is highlyunusual, and <strong>in</strong> addition to provid<strong>in</strong>g valuablevisual vignettes of Africans at work and at play,fig. 8 Chafariz d’el Rey <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Alfama District, no. 47.The Berardo Collection, Lisbon

fig. 9 Pietro Tacca (Italian, 1577–1640), figure of a slavefrom <strong>the</strong> Monumenti dei Quattro Mori, Piazza Micheli,Livorno, 1626. dea / R. Carnoval<strong>in</strong>i / De Agost<strong>in</strong>i PictureLibrary, Getty Imagesit allows <strong>the</strong> viewer to ga<strong>in</strong> a sense of black andwhite social and spatial <strong>in</strong>teraction <strong>in</strong> a sett<strong>in</strong>gwhere blacks and whites appear <strong>in</strong> roughly equalnumbers. Domestic slavery was <strong>in</strong> most cases <strong>the</strong>“easiest” form of slavery for men, less arduousand less physically dangerous than o<strong>the</strong>r forms ofslavery. Like female servants, female slaves wereeasy sexual prey wherever <strong>the</strong>y worked, although<strong>the</strong>re may have been safety as well as danger <strong>in</strong>liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> cramped conditions. Slaves were ownedby a great variety of people liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> cities andtowns: for example, one study of Valencia foundthat <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> period 1460–80, of 317 slaves, 8 percentwere owned by nobles, 8 percent by lawyersand doctors, 25 percent by merchants, shopkeepersand brokers, 11 percent by people <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> textile <strong>in</strong>dustry, 5 percent by those <strong>in</strong>volved<strong>in</strong> construction, and 4 percent by bakers.16 And<strong>in</strong> a list of black and white African female slavesshipped from Lisbon and sold <strong>in</strong> Italy through aTuscan bank <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1470s, owners <strong>in</strong>cluded goldbeaters,lea<strong>the</strong>r, wool, and silk merchants, shoemakers,a general manager of <strong>the</strong> Medici bank,<strong>the</strong> son of a humanist, and a count.17 In countrieswhere <strong>the</strong>re was a monarch, <strong>the</strong> monarchoften owned a number of slaves, and <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Italiancourts, <strong>the</strong> ruler owned slaves. The conditionsof enslavement often depended upon <strong>the</strong> statusof <strong>the</strong> owner. If a slave was owned by an artisan,s/he lived <strong>in</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> artisan’s house and atefood given by <strong>the</strong> artisan, but if a slave was ownedby a k<strong>in</strong>g or queen, or nobles, s/he was dressedwell, fed well, and housed well. Accounts from <strong>the</strong>Italian courts <strong>in</strong>clude many <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g paymentsfor slave clo<strong>the</strong>s, slave bedd<strong>in</strong>g, slave shoes, andslave artifacts. African slaves owned by monarchsand rulers also had access to excellent health care.For <strong>in</strong>stance, <strong>the</strong> Portuguese queen Ca<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>e ofAustria paid for one of her slaves who had a head<strong>in</strong>jury to be treated by her surgeon <strong>in</strong> 1552.18Those African slaves who did not live <strong>in</strong> urbancenters probably had worse lives. A particularlyunfortunate, non-urban group of about 125 blackAfricans was worked to death <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> silver m<strong>in</strong>esof Guadalcanal <strong>in</strong> Andalucia, owned by <strong>the</strong> crown,between 1559 and 1576;19 although not significant<strong>in</strong> numerical terms, <strong>the</strong>ir fate is a presentimentof <strong>the</strong> dehumanization later to befall manyo<strong>the</strong>r enslaved people. In Sicily20 and Madeira,slaves worked as agricultural laborers, some evenon sugar plantations,21 <strong>in</strong> situations that mayhave been <strong>the</strong> forerunners of plantation slavery<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Caribbean (no. 45) and United States. O<strong>the</strong>rslaves, both white and black, served on <strong>the</strong> galleys,some as punishment for a crime, o<strong>the</strong>rs because<strong>the</strong>y had been taken prisoner <strong>in</strong> war. Theoretically,most galley slaves too served time-limitedsentences, but <strong>the</strong> life was extremely hard and20

21<strong>the</strong> lives of <strong>african</strong> slaves and people of <strong>african</strong> descent <strong>in</strong> <strong>renaissance</strong> <strong>europe</strong>many died before rega<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir freedom. A monument<strong>in</strong> Livorno commemorated victory over<strong>the</strong> Ottomans <strong>in</strong> North African by Ferd<strong>in</strong>ando Ide’ Medici, <strong>the</strong> grand duke of Tuscany <strong>in</strong> 1607. Itwas composed of a marble statue of Ferd<strong>in</strong>andocompleted <strong>in</strong> 1599 and of four colossal ethnicallydiverse slaves <strong>in</strong> bronze, which were commissionedby Fernand<strong>in</strong>o’s son, Cosimo II de’ Medici,from Pietro Tacca and completed <strong>in</strong> 1626.22 TheMedici developed Livorno as an <strong>in</strong>ternationalport, sett<strong>in</strong>g up <strong>the</strong> huge bagno or depot for galleyslaves <strong>the</strong>re, and encourag<strong>in</strong>g settlement byforcibly converted ex-Jews,23 so it was populatedby an appropriately diverse population. One of <strong>the</strong>four cha<strong>in</strong>ed, nearly naked slaves, known as <strong>the</strong>Four Moors, on <strong>the</strong> base of <strong>the</strong> monument, hasblack African features (fig. 9), and had been modeled,as had <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r three, on real galley slaves.24The clean-shaven, young black man’s expression isof numbed despair, with worry l<strong>in</strong>es creas<strong>in</strong>g hishigh forehead. A note authoriz<strong>in</strong>g that Tacca takea wax cast of a slave <strong>in</strong> 1608 specified that <strong>the</strong>slave must be a well-behaved one (<strong>the</strong>refore presumablynot one with a crim<strong>in</strong>al past).25 Tacca followedclassical precedent <strong>in</strong> assembl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> mostperfect features from a number of slaves <strong>in</strong> orderto create his statues, so although <strong>the</strong> representationsof <strong>the</strong>se slaves were all taken from life, <strong>the</strong>rewere no four slaves whose faces and bodies lookedexactly as <strong>the</strong>se figures did.There are a considerable number of Renaissancerepresentations where rich and <strong>in</strong>fluentialpeople are depicted with <strong>the</strong>ir families or entourage,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir servants and slaves. Someof <strong>the</strong>se representations were almost certa<strong>in</strong>lyof real people, pa<strong>in</strong>ted or sculpted from life, and<strong>the</strong>se allow us a glimpse <strong>in</strong>to servants’/slaves’social realities. The image of <strong>the</strong> black huntsman<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> fresco of The Journey of <strong>the</strong> Magi by BenozzoGozzoli <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Medici Riccardi palace <strong>in</strong> Florenceof 1459–62 (fig. 10), which is full of portraits of <strong>the</strong>Medici and <strong>the</strong>ir friends and reta<strong>in</strong>ers, falls <strong>in</strong>tofig. 10 Benozzo Gozzoli (Italian, 1420–97), Journey of <strong>the</strong>Magi, detail of wall pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g from Palazzo Medici Riccardi,Florence, 1459–62.this category.26 One of <strong>the</strong> attractions of this veryextensive group of likenesses would have been <strong>the</strong>possibilities of recognition it afforded to contemporaries.The black African is positioned right at<strong>the</strong> front of <strong>the</strong> fresco on <strong>the</strong> east wall, betweenGaleazzo Maria Sforza, <strong>the</strong> ruler of Milan, andCosimo de’ Medici, <strong>the</strong> ruler of Florence, both ofwhose portraits would have been <strong>in</strong>stantly recognizable.At <strong>the</strong> time, <strong>the</strong> black African wouldprobably have been recognizable too, although noblack Africans have as yet been found <strong>in</strong> Cosimo’shousehold or employment. The face and headof <strong>the</strong> huntsman are strik<strong>in</strong>gly rendered, withtight, very short curls, high and deeply angled

cheekbones, wide nose, light moustache, and fulllips; he is dressed <strong>in</strong> a turquoise tunic with multicoloredhose, and holds a large bow but no arrows.Ra<strong>the</strong>r than be<strong>in</strong>g likenesses, o<strong>the</strong>r representations<strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g master and slaves were notbased on actual slaves but on imag<strong>in</strong>ed, generic,or impersonal slaves, with composite featuresor unstable African attributes, such as a turban.These, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir turn, allow us to see a differentaspect of <strong>the</strong> Renaissance attitude toward slavery.In <strong>the</strong> marble bust of 1553 attributed to <strong>the</strong> workshopof Leone Leoni (perhaps by Angelo Mar<strong>in</strong>i),<strong>the</strong> severe and impos<strong>in</strong>g Milanese judge and senator,Giacomo Maria Stampa (no. 43), is supportedby two semi-naked figures known as atlantes, onewear<strong>in</strong>g a turban.27 The occupation and pose of<strong>the</strong>se human pillars make it likely that <strong>the</strong>y weresupposed to represent slaves. Atlantes were a relativelycommon type of slave representation at <strong>the</strong>time, but <strong>the</strong> features of <strong>the</strong> atlantes <strong>the</strong>mselveswere imag<strong>in</strong>ed ra<strong>the</strong>r than “real,” <strong>in</strong> contrast tothose of <strong>the</strong> black huntsman. Even if it is merelya stylistic issue, Stampa is here represented as ahigher mortal, whose likeness is worthy of be<strong>in</strong>gremembered, held aloft by two stra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g lesserbe<strong>in</strong>gs of no consequence.Even when freed, it would have been almostimpossible for most sub-Saharan former slavesto return to <strong>the</strong>ir country of orig<strong>in</strong>. Exceptions tothis rule are provided by some of those taken on<strong>the</strong> first voyages by <strong>the</strong> Portuguese, who tra<strong>in</strong>ed<strong>the</strong>m as translators <strong>in</strong> Lisbon and took <strong>the</strong>mback on subsequent voyages to act as <strong>in</strong>terpretersfor <strong>the</strong>m,28 and some of those taken on <strong>the</strong>first English voyages, who stayed a period of time<strong>in</strong> England, probably to learn English, and <strong>the</strong>nwere taken back. Five Africans from Shama on<strong>the</strong> coast of what is now Ghana were taken to London<strong>in</strong> 1554–55. They were returned <strong>in</strong> 1556, andwere greeted with much joy, especially by <strong>the</strong> wifeof <strong>the</strong> bro<strong>the</strong>r of one of <strong>the</strong>m, and by <strong>the</strong> aunt of<strong>the</strong> same person.29 Return<strong>in</strong>g home was, however,a possibility for North Africans, especially fromSpa<strong>in</strong>, which was very close to North Africa; onestudy identified 330 freed moors who emigratedback from Valencia <strong>in</strong> Spa<strong>in</strong> to Islamic territoriesbetween 1470 and 1516, pay<strong>in</strong>g an exit tax <strong>in</strong>order to leave.30 There is also <strong>the</strong> famous case of<strong>the</strong> Muslim travel writer al-Hasan ibn Ahmad ibnMuhammad al-Wazzan, known as Leo Africanus <strong>in</strong>Europe (see Davis, pp. 61–79), who was captured,enslaved, and converted to Christianity underPope Leo X <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> second decade of <strong>the</strong> sixteenthcentury. As soon as <strong>the</strong> opportunity arose, hereturned to North Africa after years <strong>in</strong> Europe.31It is important to consider <strong>the</strong> types of collectiveactivities available to African slaves. In someparts of Europe, Africans were able to fight <strong>the</strong>irmasters through <strong>the</strong> courts (for example, <strong>in</strong> Valencia<strong>the</strong>y could appeal to an official called <strong>the</strong> Procuratorof <strong>the</strong> Wretched), and a surpris<strong>in</strong>g numberwere successful.32 In Portugal, Spa<strong>in</strong>, and Italy,<strong>the</strong>y also could belong to confraternities,33 whichwere social groups backed by <strong>the</strong> church devotedto good works, some of which were all-black, andwere heavily engaged <strong>in</strong> buy<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> freedom ofblack slaves.34 There were, <strong>in</strong> addition, parishes <strong>in</strong>Portugal and Spa<strong>in</strong> where a significant number ofAfrican people lived, which must have facilitatedmore of a sense of collective identity. The worstthreat was to say that a slave would be sold awayfrom his or her familiar surround<strong>in</strong>gs—<strong>in</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>landSpa<strong>in</strong>, difficult slaves were threatened withbe<strong>in</strong>g sent to Ibiza35 or Majorca, and <strong>in</strong> Portugal,slaves were brought to heel by <strong>the</strong> prospect ofbe<strong>in</strong>g sold <strong>in</strong> Spa<strong>in</strong>. Collective slave resistance isnot much <strong>in</strong> evidence; <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> case of black slaves,perhaps this was because slaves com<strong>in</strong>g from WestAfrica did not often speak <strong>the</strong> same, or a similar,dialect or language.However, governments were always fearful thatslaves might revolt, and so tried to limit access22

23<strong>the</strong> lives of <strong>african</strong> slaves and people of <strong>african</strong> descent <strong>in</strong> <strong>renaissance</strong> <strong>europe</strong>to dangerous weapons, or o<strong>the</strong>r implements thatcould be used as weapons, such as long staffs orknives, and to stop Africans meet<strong>in</strong>g toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>large numbers. So <strong>the</strong>y often passed laws forbidd<strong>in</strong>gslaves from carry<strong>in</strong>g weapons, forbidd<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> congregation of more than a certa<strong>in</strong> numberof Africans, forbidd<strong>in</strong>g slaves from go<strong>in</strong>g to taverns(K<strong>in</strong>g Manuel I of Portugal decreed that any<strong>in</strong>nkeeper <strong>in</strong> Lisbon who sold w<strong>in</strong>e or food to anyslave, black or white, would be f<strong>in</strong>ed),36 and even<strong>in</strong> some cases from carry<strong>in</strong>g drums or tambour<strong>in</strong>es,which might have led to a heady loss ofcontrol.37 Individual resistance ma<strong>in</strong>ly took <strong>the</strong>form of runn<strong>in</strong>g away; descriptions of runawayslaves were common, as are letters demand<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong>ir return. Only rarely did a slave kill his or hermaster, but <strong>the</strong> penalties for a slave who did sowere draconian. The tendency to view all blackpeople as slaves occurred <strong>in</strong> parts of Europe where<strong>the</strong>re were significant numbers of black slaves,and black non-slaves were sometimes required toprove <strong>the</strong>ir free status.38Fur<strong>the</strong>r important differences related to whereand how slaves were sold. Slave markets werenot designated physical spaces across much ofRenaissance Europe, which could be one reasonwhy <strong>the</strong>re are few, if any, illustrations of slavemarkets. A French pr<strong>in</strong>tmaker, Jacques Callot,made an etch<strong>in</strong>g of a scene of <strong>the</strong> ransom<strong>in</strong>g ofcaptives of ca. 1620 (no. 44),39 <strong>in</strong> a scene where virtuallyeveryone was white, which is not <strong>the</strong> sameas a slave market <strong>in</strong> Europe where newly capturedAfrican slaves are sold on to new owners. Here,<strong>in</strong>stead, white Europeans who have been capturedby pirates or overrun <strong>in</strong> war are ransomed by buyerswho take <strong>the</strong>m back to <strong>the</strong>ir homes. The sett<strong>in</strong>gappears to be a generic Mediterranean scenera<strong>the</strong>r than an actual location. Once aga<strong>in</strong>, sub-Saharan Africans were at a disadvantage becauseof <strong>the</strong> great distance between Europe and <strong>the</strong>irhomelands, so <strong>the</strong>y were not usually ransomed orexchanged. But one enterpris<strong>in</strong>g black African ofhigh status who had been captured and taken toEurope promised that if he was returned to Africa,his family would provide ten slaves <strong>in</strong> his stead,which <strong>the</strong>y duly did.40 Slaves <strong>in</strong> Italy were usuallysold from <strong>the</strong> agents’ or owners’ homes or premises,and only sometimes on public squares, and<strong>the</strong> same was probably true <strong>in</strong> all parts of Europewhere <strong>the</strong>re were not many slaves. For <strong>in</strong>stance,<strong>in</strong> Southampton a black slave was put up for sale<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1540s by his Italian owner <strong>in</strong> a square, butno buyer came forward, probably because slavery“did not exist” <strong>in</strong> England, and <strong>the</strong> English people<strong>in</strong> Southampton may not have liked <strong>the</strong> idea.41In Lagos <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Algarve, <strong>the</strong> first place <strong>in</strong> Europewhere black slaves from West Africa were disembarked,memory of <strong>the</strong> slave market where slaveswere sold is still alive hundreds of years later.42In Lisbon, a great center for arriv<strong>in</strong>g slaves, <strong>the</strong>rewas <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> fifteenth century a Slave House, <strong>the</strong>Casa dos Escravos, which handled all <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancialtransactions on behalf of <strong>the</strong> Crown. Slaveswere valued by crown officials and a price tagtied around <strong>the</strong> slave’s neck.43 Slaves could beviewed at <strong>the</strong> Slave House or were sold to contractorsor brokers, who re-sold slaves at <strong>the</strong> regularslave auctions <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> public square known as <strong>the</strong>Pelour<strong>in</strong>ho Velho.44 Procedures for sales differedgreatly with<strong>in</strong> Europe. At Valencia and at Mantua<strong>in</strong> Italy, for example, a crucial part of a slave salewas <strong>the</strong> “<strong>in</strong>terview” between <strong>the</strong> slave and his orher potential buyer,45 an occurrence that allowedslaves a measure of self-presentation. Some slaveswere very successful <strong>in</strong> refus<strong>in</strong>g to be sold away:<strong>the</strong>y feigned madness, were thoroughly objectionableand out of control, or self-harmed, as <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>case of a female slave who put a sew<strong>in</strong>g needle upher nose.46

treatment of slavesWhen newly enslaved African people arrived <strong>in</strong>Europe, <strong>the</strong>y had to beg<strong>in</strong> a difficult process ofadjustment to becom<strong>in</strong>g a slave. Be<strong>in</strong>g renamedwas an especially important part of this process,as it signaled a milestone on <strong>the</strong> long journeyof be<strong>in</strong>g forced to readjust to a life of new socialrealities <strong>in</strong> a new country, and to a new religiousallegiance. Many nam<strong>in</strong>g practices make trac<strong>in</strong>gAfricans <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> records complicated. It is difficultto know from fifteenth- and sixteenth-centurydocumentary sources who is an African, unless<strong>the</strong>ir place of orig<strong>in</strong> or sk<strong>in</strong> color is spelled out.When Africans were enslaved and taken to Europe,<strong>the</strong>y were given European Christian names andwere forced to drop <strong>the</strong>ir own names. A few NorthAfrican Muslims held onto <strong>the</strong>ir own names, so,for example, <strong>the</strong>re is a North African slave namedBarack <strong>in</strong> a Genoese document from 1432,47 butsub-Saharan Africans ma<strong>in</strong>ly did not. Some sub-Saharan Africans <strong>in</strong> Africa who were not slavesmay have chosen <strong>the</strong>ir own Christian nameswhen <strong>the</strong>y converted. The ruler of <strong>the</strong> Kongo, hisclose family and his “nobles,” when <strong>the</strong>y acceptedChristianity <strong>in</strong> 1491, were baptized with exactly<strong>the</strong> same names as <strong>the</strong>ir royal and noble counterparts<strong>in</strong> Portugal: <strong>the</strong> ruler was called João, afterK<strong>in</strong>g João II of Portugal, his consort was calledLeonor, after Queen Leonor, and <strong>the</strong>ir eldest sonwas called Afonso, after Afonso, <strong>the</strong> son of Joãoand Leonor.48 And so on with all <strong>the</strong> nobles. Slaveswere given Christian names, often from quite asmall pool, so <strong>in</strong> Italy <strong>the</strong>re are many slaves namedLucia, Giovanni, or Marta, and <strong>in</strong> Portugal <strong>the</strong>reare hundreds of slaves called Maria, António,Catar<strong>in</strong>a, or Francisco.49 They were often referredto by this Christian name <strong>in</strong> conjunction with <strong>the</strong>surname of <strong>the</strong>ir owner, which would change onceaga<strong>in</strong> if <strong>the</strong>y were sold to o<strong>the</strong>r owners. Many Africanswere given nicknames related to <strong>the</strong>ir sk<strong>in</strong>color (Carbone / Charcoal, or Maura / Moor),50 and<strong>the</strong>re were many “joke” names too, such as JohnWhite, or its equivalent, which is found acrossEurope. Occasionally, <strong>in</strong>stead of be<strong>in</strong>g given <strong>the</strong>surname of <strong>the</strong>ir owner, <strong>the</strong>y were given <strong>the</strong>irowner’s Christian name, and ano<strong>the</strong>r “joke” surnamewas “<strong>in</strong>vented” for <strong>the</strong>m. Edward W<strong>in</strong>ter<strong>in</strong> England gave his slave <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>vented surname“Swarthye” so that <strong>the</strong> slave was known as EdwardSwarthye.51 Fashion <strong>in</strong> slave names went throughperiods when classical names were common, forexample, Pompey or Fortunatus.Learn<strong>in</strong>g a new European language was ano<strong>the</strong>rvital element of <strong>the</strong> process of becom<strong>in</strong>g a slave<strong>in</strong> Europe. Europe was not a l<strong>in</strong>guistic entity, buta conglomeration of countries and areas, many ofwhich had different languages, so often Africanshad to learn more than one new European language.Vicente Lusitano was of African descentand wrote a famous book on musical <strong>the</strong>ory. Hewas born <strong>in</strong> Portugal, went to Rome <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> earlysixteenth century, and <strong>the</strong>n went on to a Germancourt, and he must have spoken <strong>the</strong> languagesof all <strong>the</strong>se places.52 The common written languageof <strong>the</strong> educated <strong>in</strong> Renaissance Europe wasLat<strong>in</strong>, which would have been even more difficultto acquire than a vernacular language. However,<strong>the</strong>re is evidence of Africans not only master<strong>in</strong>git,53 but also compos<strong>in</strong>g and publish<strong>in</strong>g works<strong>in</strong> it.54 In terms of spoken communication, creoleor pidg<strong>in</strong> were available to recent African arrivals<strong>in</strong> Renaissance Europe, although it is not knownhow extensively <strong>the</strong>y were used. Whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>ywere or not, <strong>in</strong> Portugal fala de Gu<strong>in</strong>é (Gu<strong>in</strong>easpeak—that is, <strong>the</strong> type of speech used by WestAfricans) and its Spanish equivalent habla denegros (black speak) were mocked <strong>in</strong> contemporaryplays, poems, and jokes.55There was discrim<strong>in</strong>ation at all levels, justas <strong>the</strong>re was acceptance at all levels, so <strong>the</strong> picturerema<strong>in</strong>s mixed. The sixteenth-century black24

25<strong>the</strong> lives of <strong>african</strong> slaves and people of <strong>african</strong> descent <strong>in</strong> <strong>renaissance</strong> <strong>europe</strong>Portuguese court jester or fool, João de Sá dePanasco, is a good example of a very talentedperformer who, while promoted and protected by<strong>the</strong> Portuguese monarchs, also suffered vicious<strong>in</strong>sults about his former slave status and hisblack sk<strong>in</strong> from <strong>the</strong> tongues of nobles and courtiersjealous of his position and success.56 However,he was successful enough to be made a knight of<strong>the</strong> Order of Santiago, one of only three black Africansto be so honored <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sixteenth century,<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r two be<strong>in</strong>g prom<strong>in</strong>ent black courtiersat African courts.57 More jokes aga<strong>in</strong>st him survivethan jokes that he made himself. These jokesreveal a great deal about reactions or responses toa successful black African liv<strong>in</strong>g a protected lifeat court.Nor should <strong>the</strong> sometimes punitive nature ofEuropean Renaissance slavery be ignored; as wasto be expected, this differed from place to place. Atits worst, for <strong>in</strong>stance <strong>in</strong> Valencia, slaves <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividualhouses were locked up at night <strong>in</strong> woodencages and restra<strong>in</strong>ed with ropes and stirrups,58but this was quite exceptional. Slaves could alsooften be physically punished for misdemeanorsmore severely than free people, a differentiationthat could be enshr<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> law. Slave-owners couldbe tried if a slave died as a result of punishment,but few were—societal pressure militated aga<strong>in</strong>sttoo harsh a cruelty more successfully than <strong>the</strong>law. It is also worth remember<strong>in</strong>g that nearly allgroups <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> household at this time were liable tophysical chastisement by <strong>the</strong> heads of <strong>the</strong> household:wives, children, servants, and slaves, soslaves were by no means <strong>in</strong> a unique position <strong>in</strong>this respect. Ano<strong>the</strong>r identify<strong>in</strong>g feature of slaveswas that <strong>the</strong>y could be branded: slaves belong<strong>in</strong>gto <strong>the</strong> Portuguese crown were branded on <strong>the</strong> arm.All slaves taken to São Tomé from Ben<strong>in</strong> or elsewhereafter 1519 were branded with a cross on <strong>the</strong>irupper right arm,59 later changed to a G, <strong>the</strong> marcade Gu<strong>in</strong>é.60 In Spa<strong>in</strong>, slaves were branded withan S on one cheek, and an I, signify<strong>in</strong>g a clavo, anail, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r, so that <strong>the</strong> whole read esclavo,<strong>the</strong> word for slave.61 In Italy and elsewhere, slaveswere branded only if <strong>the</strong>y ran away, not as a primarymeans of identification.The treatment of slaves can be grouped underseveral head<strong>in</strong>gs. First of all, Europe was not aplace of one religion. The established religion <strong>in</strong>mid-fifteenth-century Europe was Catholicism,but <strong>the</strong>re were also small but significant numbersof Jews and of Muslims. By <strong>the</strong> mid-sixteenthcentury, <strong>the</strong>re were also large numbers of Protestants,of many different types. The papacy usuallyapproved and backed up <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitution of slavery,and priests, bishops, card<strong>in</strong>als, and popes allowned slaves. The first cargo of slaves to <strong>in</strong>cludeblack slaves arrived <strong>in</strong> Europe at Lagos <strong>in</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rnPortugal <strong>in</strong> 1444, and some of this <strong>in</strong>itialcohort were sent to ecclesiastical establishments.In terms of conversion, black slaves brought fromWest Africa who were considered “animist,” wereoften summarily baptized by be<strong>in</strong>g spr<strong>in</strong>kledwith water on board ship or, if not, <strong>the</strong>y were supposedto be baptized by <strong>the</strong>ir new owners. Oftenthis compulsory baptism was more honored <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>breach than <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> observance, even at <strong>the</strong> highestlevels of society. K<strong>in</strong>g João II of Portugal offered<strong>in</strong>centives <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> form of cloth<strong>in</strong>g, called “victoryclo<strong>the</strong>s” if his slaves converted, but <strong>in</strong> 1493, atleast three of his slaves still reta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>the</strong>ir Africannames, transcribed <strong>in</strong>to Portuguese as Tanba,Tonba, and Baybry,62 which demonstrates that<strong>the</strong>y had not converted to Christianity because<strong>the</strong>y had not been given Christian names. PopeLeo X’s bull Eximiae devotionis of 1513 providedfor <strong>the</strong> erection of a baptismal font <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Churchof Nossa Senhora de Conçeição <strong>in</strong> Lisbon specificallyto cater for <strong>the</strong> baptism of newly arrivedblack slaves.63 Islamic North Africans, if <strong>the</strong>yconverted, sometimes had more elaborate baptismalceremonies (as did Jews) because Islam and

Christianity were locked <strong>in</strong> conflict and conversionof <strong>the</strong> “<strong>in</strong>fidel” was highly prized.64 Baptismdid not alter slave status. Slaves were afforded differentialtreatment accord<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong>ir perceivedreligion, ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong>ir sk<strong>in</strong> color. Muslimswere regarded less favorably than “animist” blackAfricans, only a small percentage of whom hadbeen Islamicized; because Muslims were <strong>the</strong> traditionalenemies of Christians <strong>in</strong> Europe, as slaves<strong>the</strong>y were believed to be more difficult and lesstrustworthy than non-Muslims.The European country of dest<strong>in</strong>ation mattered,as treatment could vary widely. There was a difference<strong>in</strong> how slaves were perceived and treatedbetween countries with differ<strong>in</strong>g political systems:monarchies, republics, courts. Countriesalso had differ<strong>in</strong>g traditions of slavery. In legalterms, slavery was enshr<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> Roman law, butvarious countries and cities <strong>in</strong> Europe ei<strong>the</strong>r didnot adhere to Roman law or promulgated localstatutes that overrode certa<strong>in</strong> aspects of it. Dist<strong>in</strong>ctivelaw codes were composed for societieswith large numbers of slaves. For <strong>in</strong>stance, royallaws promulgated <strong>in</strong> Portugal from 1481 to 1514—aperiod when many black Africans arrived—werecollected <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> law code called <strong>the</strong> OrdenaçõesManuel<strong>in</strong>as.There were special problems <strong>in</strong> parts of Nor<strong>the</strong>rnEurope such as Sweden and England, whereslavery was not legal because it had been abolished.In 1532, an <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g case arose <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> LowCountries. A “white Moor” called Simon, brandedwith a P on one cheek and an M on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r, whowas a slave of <strong>the</strong> Portuguese ambassador to <strong>the</strong>emperor Charles V, absconded by return<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong>Low Countries while his master cont<strong>in</strong>ued to Germany.When his return was requested through <strong>the</strong>usual diplomatic channels, <strong>the</strong> Grand Conseil, <strong>the</strong>highest court of law <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Low Countries, refusedto help, stat<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir country, personalslavery did not exist.65 Yet <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> fifteenth andsixteenth centuries, African “slaves” cont<strong>in</strong>uedto be brought <strong>in</strong>to England, Sweden, and <strong>the</strong> LowCountries by <strong>the</strong>ir masters, and were treated <strong>in</strong>precisely <strong>the</strong> same manner as <strong>the</strong>y had been when<strong>the</strong>y were liv<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>the</strong>ir “owners” <strong>in</strong> countrieswhere slavery was legal. To a certa<strong>in</strong> extent, <strong>the</strong>illegality of slavery <strong>in</strong> England must have beenknown, even if only by hearsay, as <strong>the</strong>re is a caseof a black African’s refusal to be someone’s slave.In 1587, Hector Nunes, a forcibly converted Portugueseex-Jew liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> London, bought a black maleslave from an English sailor for £4 10s. but, as hiswould-be master put it, <strong>the</strong> “slave” utterly refusedto serve him. When Nunes went to court to try toforce his “slave” to acquiesce, he found no satisfaction,<strong>in</strong>stead be<strong>in</strong>g told that his only recoursewas to apply to a debtors’ court for <strong>the</strong> repaymentof his costs.66 In addition, as slavery was not supposedto exist, slaves could not be freed by clauses<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir masters’ wills because <strong>the</strong> law of Englanddid not recognize <strong>the</strong>m as slaves <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> first place.There were also differences <strong>in</strong> how Africans wereviewed and treated that varied accord<strong>in</strong>g to howmany Africans <strong>the</strong>re were <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> area or country,and <strong>the</strong>refore how rare or common <strong>the</strong>y were. InGerman cities and <strong>in</strong> Scand<strong>in</strong>avia, where blackAfricans were <strong>the</strong> exception, <strong>the</strong>y stood out.It is important to notice how issues relat<strong>in</strong>g tosex and sexual relations, and to marriage, weredealt with <strong>in</strong> connection to slaves. Female Africanslaves—like all o<strong>the</strong>r slaves and servants liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>a household—were vulnerable to sexual assaultfrom <strong>the</strong>ir male masters, but <strong>the</strong>y were also at <strong>the</strong>mercy of many o<strong>the</strong>r men, both <strong>in</strong> and outside <strong>the</strong>household. The lies that slave-owners told <strong>in</strong> thisrespect are extraord<strong>in</strong>ary; one claimed <strong>in</strong> a Spanishcourt of law that it was not lust that had drivenhim to have sex with his slave, but a desire to f<strong>in</strong>drelief from <strong>the</strong> pa<strong>in</strong> of his kidney stones.67 Most26