Summer 2010 - PAWS Chicago

Summer 2010 - PAWS Chicago

Summer 2010 - PAWS Chicago

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

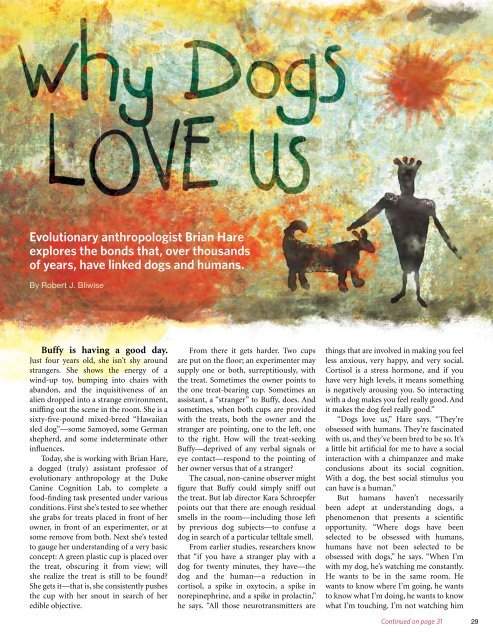

Evolutionary anthropologist Brian Hareexplores the bonds that, over thousandsof years, have linked dogs and humans.By Robert J. BliwiseBuffy is having a good day.Just four years old, she isn’t shy aroundstrangers. She shows the energy of awind-up toy, bumping into chairs withabandon, and the inquisitiveness of analien dropped into a strange environment,sniffing out the scene in the room. She is asixty-five-pound mixed-breed “Hawaiiansled dog”—some Samoyed, some Germanshepherd, and some indeterminate otherinfluences.Today, she is working with Brian Hare,a dogged (truly) assistant professor ofevolutionary anthropology at the DukeCanine Cognition Lab, to complete afood-finding task presented under variousconditions. First she’s tested to see whethershe grabs for treats placed in front of herowner, in front of an experimenter, or atsome remove from both. Next she’s testedto gauge her understanding of a very basicconcept: A green plastic cup is placed overthe treat, obscuring it from view; willshe realize the treat is still to be found?She gets it—that is, she consistently pushesthe cup with her snout in search of heredible objective.From there it gets harder. Two cupsare put on the floor; an experimenter maysupply one or both, surreptitiously, withthe treat. Sometimes the owner points tothe one treat-bearing cup. Sometimes anassistant, a “stranger” to Buffy, does. Andsometimes, when both cups are providedwith the treats, both the owner and thestranger are pointing, one to the left, oneto the right. How will the treat-seekingBuffy—deprived of any verbal signals oreye contact—respond to the pointing ofher owner versus that of a stranger?The casual, non-canine observer mightfigure that Buffy could simply sniff outthe treat. But lab director Kara Schroepferpoints out that there are enough residualsmells in the room—including those leftby previous dog subjects—to confuse adog in search of a particular telltale smell.From earlier studies, researchers knowthat “if you have a stranger play with adog for twenty minutes, they have—thedog and the human—a reduction incortisol, a spike in oxytocin, a spike innorepinephrine, and a spike in prolactin,”he says. “All those neurotransmitters arethings that are involved in making you feelless anxious, very happy, and very social.Cortisol is a stress hormone, and if youhave very high levels, it means somethingis negatively arousing you. So interactingwith a dog makes you feel really good. Andit makes the dog feel really good.”“Dogs love us,” Hare says. “They’reobsessed with humans. They’re fascinatedwith us, and they’ve been bred to be so. It’sa little bit artificial for me to have a socialinteraction with a chimpanzee and makeconclusions about its social cognition.With a dog, the best social stimulus youcan have is a human.”But humans haven’t necessarilybeen adept at understanding dogs, aphenomenon that presents a scientificopportunity. “Where dogs have beenselected to be obsessed with humans,humans have not been selected to beobsessed with dogs,” he says. “When I’mwith my dog, he’s watching me constantly.He wants to be in the same room. Hewants to know where I’m going, he wantsto know what I’m doing, he wants to knowwhat I’m touching. I’m not watching himContinued on page 3129