Water and Sanitation in Tanzania - Poverty Monitoring

Water and Sanitation in Tanzania - Poverty Monitoring

Water and Sanitation in Tanzania - Poverty Monitoring

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

ForewordBAKARI A. MAHIZAPERMANENT SECRETARYMINISTRY OF WATER AND LIVESTOCKDEVELOPMENT<strong>Tanzania</strong>’s <strong>Poverty</strong> Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP) recognizes, elim<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>gpoverty will not be done without provid<strong>in</strong>g every person with access to safedr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water.In 2001 <strong>Tanzania</strong> developed a <strong>Poverty</strong> Monitor<strong>in</strong>g System to coord<strong>in</strong>ate thegather<strong>in</strong>g of evidence on the welfare of poor people. Sources for this evidence<strong>in</strong>clude national surveys, the census, rout<strong>in</strong>e data collected by m<strong>in</strong>istries <strong>and</strong>local government as well as specific pieces of research <strong>and</strong> analysis.Over the past year the M<strong>in</strong>istry of <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> Livestock Development hasbeen work<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>Water</strong>Aid, the Eastern Africa Statistical Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Center<strong>and</strong> the National Bureau of Statistics on this study look<strong>in</strong>g at povertymonitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the water <strong>and</strong> sanitation sector.The study, supported by the Department for International Development(DFID), evolved out of a water <strong>and</strong> sanitation stakeholders’ workshop, held <strong>in</strong>September 2001, which reviewed the <strong>in</strong>dicators <strong>and</strong> highlighted gaps <strong>in</strong> both thelist of <strong>in</strong>dicators <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> the data collection systems designed to measure the<strong>in</strong>dicators. The poverty monitor<strong>in</strong>g study that emerged was guided by anAdvisory Team with representation from MoWLD, MoH, UNICEF, UCLAS,NETWAS, NBS, ESTAC, REPOA <strong>and</strong> Concern Worldwide.The study evaluates water <strong>and</strong> sanitation <strong>in</strong>dicators used by rout<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong>survey data collections systems <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>and</strong> exam<strong>in</strong>es the way <strong>in</strong> which dataon water <strong>and</strong> sanitation is recorded <strong>and</strong> collated. It also reports on trendsderived from exist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dicators <strong>and</strong> from those trends reflects on the utility of<strong>in</strong>dicators used. F<strong>in</strong>ally the report recommends changes to <strong>in</strong>dicators for bothrout<strong>in</strong>e data collection <strong>and</strong> national surveys.The f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs were shared at the technical level at a workshop held at thePlann<strong>in</strong>g Commission on the 22nd of May 2002. The presentation was shared <strong>and</strong>discussed by staff from PO-PP, VPO, MoWLD Directors, the National Bureauof statistics, the Local Government Reform Programme, ESRF, REPOA, Bankof <strong>Tanzania</strong>, DFID, JICA, UNDP, Netherl<strong>and</strong>s International Cooperation(DGIS), Concern Worldwide <strong>and</strong> WATSANET.Cont<strong>in</strong>ued collaboration will be key to ensur<strong>in</strong>g that the necessarymodifications are consolidated <strong>in</strong> the relevant national surveys <strong>and</strong> that thequality <strong>and</strong> consistency of water <strong>and</strong> sanitation data is improved. In turn thiswill be a significant step towards strengthen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Tanzania</strong>’s poverty monitor<strong>in</strong>gsystem <strong>and</strong> our efforts to eradicate poverty.Bakari A. MahizaPermanent SecretaryM<strong>in</strong>istry of <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> Livestock Development

AcknowledgementsThis study was a collaborative project for the water <strong>and</strong> sanitation sector led bythe M<strong>in</strong>istry of <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> Livestock Development, <strong>Water</strong>Aid - <strong>Tanzania</strong> withEastern Africa Statistical Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Centre <strong>and</strong> National Bureau of Statistics.This report was written by Jenni Marshall, <strong>Water</strong>Aid-<strong>Tanzania</strong> with Dr ZakyaoMsokwa EASTC <strong>and</strong> Mr Felix Ngamlagosi, MoWLD. Mrs Naomi Lupimo ofMoWLD contributed significantly to earlier stages of the work. Mr Said Aboud<strong>and</strong> the HBS team from the National Bureau of Statistics also assisted. Theanalysis was carried out with <strong>in</strong>put from Advisory Team (as above plus MrsMary Swai, M<strong>in</strong>istry of Health; Mrs Rebecca Budimu, UNICEF; Eng RichardEvans, Concern Worldwide; Professor Kironde, UCLAS, with <strong>in</strong>put fromNETWAS <strong>and</strong> WATSANET). The study also benefited from conceptual supportfrom Alana Albee, Senior Social Development Adviser DFIDEA(T) <strong>and</strong> theResearch <strong>and</strong> Analysis Work<strong>in</strong>g Group of the <strong>Poverty</strong> Monitor<strong>in</strong>g System.© 2002 MoWLD, <strong>Water</strong>Aid, EASTC <strong>and</strong> NBS, <strong>Tanzania</strong>

Contents91.0 INTRODUCTION TO POVERTY MONITORING FOR WATER AND SANITATION1.1 <strong>Water</strong>, <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>1.2 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>: Monitor<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>in</strong>formed poverty eradication strategies1.3 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>: <strong>Poverty</strong> Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Indicators1.4 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>: the study objectives112.0 DATA SOURCES AND THEIR COMPARABILITY2.1 National household surveys used2.1.1 Household Budget Survey 1991 <strong>and</strong> 2000/12.1.2 Demographic <strong>and</strong> Health Surveys <strong>in</strong> the 1990s2.1.3 Population Census 1978 <strong>and</strong> 19882.1.4 Surveys referenced but not <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the analysis2.2 Comparability <strong>and</strong> consistency of surveys2.2.1 Compar<strong>in</strong>g sample designs2.2.2 Consistency of data sets collected through surveys2.2.3 Comparability of questions <strong>and</strong> response options2.3 Other data sources for reference2.4 Quantitative data analysis - po<strong>in</strong>ts to remember173.0 WATER IN TANZANIA3.1 Longer-term trends <strong>in</strong> dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water source use - for rural <strong>and</strong> urban areas3.1.1 Use of piped water for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g 1978 to 20013.1.2 Use of well water for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g 1978 to 20013.1.3 Use of surface water for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g 1978 to 20013.2 Use of improved water sources as an estimation of access to safe water3.2.1 What do we mean by access to safe water?3.2.2 Measur<strong>in</strong>g the PRSP <strong>in</strong>dicator: Improved water source use <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>in</strong> 2000/13.2.3 Use of improved water sources for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g by rural, urban <strong>and</strong> Dar based households3.3 Distance <strong>and</strong> time to water source3.3.1 (Not) measur<strong>in</strong>g the policy target - estimat<strong>in</strong>g distance3.3.2 Trends <strong>in</strong> distance to water <strong>in</strong> the dry season3.3.2 Trends <strong>in</strong> time taken to fetch water3.4 Regional differences <strong>in</strong> use of <strong>and</strong> distance to water sources3.4.1 Regional differences <strong>in</strong> use of improved water sources3.4.2 Regional differences <strong>in</strong> time to water sources <strong>in</strong> the dry season324.0 SANITATION IN TANZANIA4.1 Use of toilets <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>345.0 WATER, SANITATION, GENDER AND INCOME POVERTY5.1 Gender <strong>and</strong> water <strong>and</strong> sanitation <strong>in</strong> the surveys5.1.1 What participatory research tells us5.1.2 Female headed households <strong>and</strong> piped water5.1.3 Female headed households <strong>and</strong> use of surface water5.1.4 Female-headed households <strong>and</strong> use of improved water5.2 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>and</strong> basic needs poverty

5.2.1 Basic needs poverty5.2.2 Basic needs poverty <strong>and</strong> use of improved (piped <strong>and</strong> protected) water sources5.2.3 <strong>Poverty</strong> qu<strong>in</strong>tiles <strong>and</strong> use of improved water sources5.2.4 Poorer households <strong>and</strong> their distance to water5.2.5 Regional patterns: access to water <strong>and</strong> basic needs poverty5.3 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> education456.0 SOME POLICY IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS6.1 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> sanitation as priority sector for poverty reduction6.1.1 The state of water <strong>and</strong> sanitation <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>6.1.2 Prioritis<strong>in</strong>g the sector6.2 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> sanitation targets for poverty reduction6.2.1 Geographical <strong>in</strong>equalities <strong>in</strong> water <strong>and</strong> sanitation6.2.2 Dar es Salaam: pro poor plann<strong>in</strong>g?6.2.3 Pro-poor targets for the PRS?6.3 Quality data <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation for <strong>Poverty</strong> Monitor<strong>in</strong>g6.3.1 Data quality <strong>and</strong> consistency6.3.2 Which data source to use?477.0 POVERTY MONITORING FOR THE SECTOR:RECOMMENDED MODIFICATIONS BASED ON THE SURVEY RESULTS7.1 Mak<strong>in</strong>g recommendations7.2 The recommendations7.3 Indicators for <strong>in</strong>form<strong>in</strong>g poverty eradication strategies - whose access?7.4 Tak<strong>in</strong>g it forward: possible research priorities7.4.1 Surveys <strong>and</strong> census7.4.2 Rout<strong>in</strong>e Data Systems7.4.3 Qualitative research7.4.4 Tak<strong>in</strong>g on the challenges as a coalition56REFERENCES59DATASETS60APPENDICIES

Executive Summary<strong>Tanzania</strong>’s <strong>Poverty</strong> Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP) recognizes that theeradication of poverty will not be achieved without provid<strong>in</strong>g every person withaccess to safe dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water.In 2001 <strong>Tanzania</strong> developed a <strong>Poverty</strong> Monitor<strong>in</strong>g System to coord<strong>in</strong>ate thegather<strong>in</strong>g of evidence on the welfare of poor people, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g their access tosafe water <strong>and</strong> sanitation. Sources for this evidence <strong>in</strong>clude national surveys, thecensus, rout<strong>in</strong>e data collected by m<strong>in</strong>istries <strong>and</strong> local government as well asspecific pieces of research <strong>and</strong> analysis.This study reviews water <strong>and</strong> sanitation <strong>in</strong>dicators used by national surveys<strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>. It exam<strong>in</strong>es the way <strong>in</strong> which data on water <strong>and</strong> sanitation isrecorded <strong>and</strong> collated. The study reports on trends derived from exist<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>dicators <strong>and</strong> from those trends reflects on the usefulness of exist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dicators.F<strong>in</strong>ally the report recommends changes to <strong>in</strong>dicators for use with nationalsurveys.“The study reports ontrends derived fromexist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dicators <strong>and</strong>from those trendsreflects on theusefulness of exist<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>dicators. “Compar<strong>in</strong>g surveys for analysisAnalysis of water <strong>and</strong> sanitation data collected by national surveys was carriedout us<strong>in</strong>g the Household Budget Survey (HBS), the Demographic <strong>and</strong> HealthSurvey (DHS) <strong>and</strong> the Population <strong>and</strong> Hous<strong>in</strong>g Census. Each of these studiesgives national figures <strong>and</strong> can be disaggregated by rural <strong>and</strong> urban areas. TheHBS 2001 sample allows greater disaggregation, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g disaggregation atregional level.Word<strong>in</strong>g of the <strong>in</strong>dicators for water <strong>and</strong> sanitation makes comparison acrossall three surveys limited. However, where the word<strong>in</strong>g of questions wassufficiently clear <strong>and</strong> consistent - such as for ‘percentage of households us<strong>in</strong>gpiped water’ - this study demonstrates that the results of the three surveys canbe compared.Measur<strong>in</strong>g Safe <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> Effective <strong>Sanitation</strong>The def<strong>in</strong>ition of safe water used <strong>in</strong> the PRSP <strong>in</strong>dicator ‘Proportion ofhouseholds with access to safe dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water (<strong>in</strong> rural <strong>and</strong> urban areas)’ is notdirectly measured by any of the surveys. Some surveys do however measure useof improved sources, which is a commonly accepted proxy for safe watersources. In addition to piped water, improved sources <strong>in</strong>clude wells or spr<strong>in</strong>gsthat have been protected by enclos<strong>in</strong>g the source to prevent contam<strong>in</strong>ation byrun-off water. Use of improved sources has been recorded by the HBS s<strong>in</strong>ce1991 <strong>and</strong> by the DHS s<strong>in</strong>ce 1999.<strong>Sanitation</strong> data is not comparable across the three surveys. The DHSrecords ownership while the HBS records use of toilet facilities. Both surveysrecord questionably high percentages, above 90% for most regions. In additionthe response options for toilet facilities are confus<strong>in</strong>g - the term VIP (ventilatedimproved pit) be<strong>in</strong>g too specific <strong>and</strong> the term ‘pit latr<strong>in</strong>e’ be<strong>in</strong>g too broad.Notably there are no survey data on sewage systems.Trends <strong>in</strong> use of water sourcesLong-term trends for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water sources were analysed for piped water,well water <strong>and</strong> surface water. As sources of well water <strong>in</strong>clude both protected(improved) <strong>and</strong> unprotected wells it is not possible to assess long-term trends ofaccess to safe water.Trends over the period 1978 to 2000 do not reveal significant changes <strong>in</strong> thepercentage of households served by piped or well water. However, thepopulation has grown from 17 million <strong>in</strong> 1978 to around 32 million <strong>in</strong> 2000 so theabsolute number of households served has nearly doubled.Rural-urban disparity throughout the period is very large. Households us<strong>in</strong>gpiped supplies <strong>in</strong> urban areas be<strong>in</strong>g around 80% compared to rural areas withpiped supplies <strong>in</strong> the 20-25% range for the same period.<strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 20025

In rural areas the percentage of households us<strong>in</strong>g surface water (dams, lakes,ponds, rivers <strong>and</strong> streams) has dropped from just under 30% <strong>in</strong> 1991 to around17% <strong>in</strong> 2000. This is positive as surface water sources are associated with higherhealth risks than other sources.For a more detailed analysis of the proportion of households with access tosafe water this study focused on the 1991 <strong>and</strong> 2000 Household Budget Surveys.In l<strong>in</strong>e with the def<strong>in</strong>itions used for the Millennium Development Goals thisstudy analyses improved sources as a proxy for safe sources. The analysis for‘use of improved water sources’ was broken down <strong>in</strong>to three parts; rural areas,Dar es Salaam <strong>and</strong> urban centers other than Dar es Salaam.In rural areas the proportion of households us<strong>in</strong>g improved sources (piped<strong>and</strong> protected) rose by 11%. This is contributed to by a comb<strong>in</strong>ed rise <strong>in</strong> the useof piped sources (up 3%) <strong>and</strong> protected wells <strong>and</strong> spr<strong>in</strong>gs (up 8%).In Dar es Salaam the proportion of households us<strong>in</strong>g piped water dropped byjust over 7%. This drop <strong>in</strong> use of piped water has been compensated for by a shiftto protected sources (up 4%) as well as small shifts to unprotected sources (up2%), tankers <strong>and</strong> vendors.There was little change <strong>in</strong> urban areas other than Dar es Salaam with only asmall rise <strong>in</strong> the proportion households us<strong>in</strong>g improved sources (up 4%).Trends <strong>in</strong> accessDistance <strong>and</strong> time to water source give a partial <strong>in</strong>dication of the burden ofdomestic water management felt by women <strong>and</strong> children <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>and</strong> is an<strong>in</strong>dication of time that could be spent on more productive <strong>and</strong> social activities.Surveys are not consistent <strong>in</strong> their measurement of time <strong>and</strong> distance towater <strong>and</strong> none of them measure the National <strong>Water</strong> Policy target of ‘with<strong>in</strong> 400meters’. This study, however, recommends ‘time to fetch water’ as a more useful<strong>in</strong>dicator than ‘distance to water source’.The <strong>in</strong>dicator ‘time to fetch water’ <strong>in</strong>cludes go<strong>in</strong>g to the water source,wait<strong>in</strong>g, collect<strong>in</strong>g water <strong>and</strong> return<strong>in</strong>g home. The Demographic <strong>and</strong> HealthSurvey, illustrates the change <strong>in</strong> ‘time to fetch water’ over the 1990s. In urbanareas there has been a 14% drop <strong>in</strong> the proportion of urban households tak<strong>in</strong>gless than 30 m<strong>in</strong>utes to fetch water. This is particularly significant given that theHBS reported that the ‘proportion of urban households with access to waterwith<strong>in</strong> less than one kilometer’ actually rose by 3%. So ‘time to fetch water’ is abetter <strong>in</strong>dicator of the chang<strong>in</strong>g dem<strong>and</strong> or stress that manag<strong>in</strong>g water puts on,particularly, women.Regional variation <strong>in</strong> use of improved water sourcesRegional differences <strong>in</strong> the use of water sources can be compared us<strong>in</strong>g the HBSdata sets. There is a clear pattern between the ‘proportions of households withimproved water sources’ <strong>and</strong> Government/donor funded water supplyprogrammes. Though this is reveal<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>tra-regional differences are hidden asHBS data can only be disaggregated to the regional level. As districts are thepr<strong>in</strong>cipal agencies for implement<strong>in</strong>g development activities, surveys wouldideally collect sufficient data to enable analysis by district. Though the cost ofdo<strong>in</strong>g this for national surveys may be prohibitively expensive the ref<strong>in</strong>ementsto 2002 Census water <strong>in</strong>dicators should enable analysis of protected <strong>and</strong>unprotected sources by district.The HBS also records high regional disparities <strong>in</strong> household water use fromprotected sources <strong>in</strong> rural areas, L<strong>in</strong>di 11% as compared to Kilimanjaro 74%.These figures differ considerably from the M<strong>in</strong>istry of <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> LivestockDevelopment’s rout<strong>in</strong>e data figures for the same year (L<strong>in</strong>di 34% <strong>and</strong>Kilimanjaro 48%). Two factors may contribute to this. First, that rout<strong>in</strong>e data iscollected on the basis of population coverage rather than households. Second,that the HBS data is based on samples whereas rout<strong>in</strong>e data is collated fromregion wide adm<strong>in</strong>istrative sources. These differences emphasise the need tomake sources clear when quot<strong>in</strong>g national statistics.“Surveys are notconsistent <strong>in</strong> theirmeasurement oftime <strong>and</strong> distance towater <strong>and</strong> none ofthem measure theNational <strong>Water</strong> Policytarget of ‘with<strong>in</strong> 400meters’.”Gender <strong>and</strong> waterFemale headed households - as recorded by the HBS - were 7% more likely to beus<strong>in</strong>g piped water than male headed households. Surface water use by female6 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 2002

“The fact that thisanalysis relies soheavily on the datacollected by the HBSis evidence that dataquality <strong>and</strong>consistency acrossnational surveysneeds to beimproved.”headed households was also 5% lower than that for male headed households.This suggests that women headed households tend to choose protected watersources <strong>and</strong>/or prioritise water with<strong>in</strong> the household budget. This an area forfurther research.Education <strong>and</strong> waterSchool aged children liv<strong>in</strong>g with<strong>in</strong> 15 m<strong>in</strong>utes of their dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water sourcewere 12% more likely to be attend<strong>in</strong>g school than children liv<strong>in</strong>g over one hourfrom their source of dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water.<strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>and</strong> waterThe basic needs poverty l<strong>in</strong>e (derived from expenditure data), developed by theNational Bureau of Statistics, is used by this study to look at differential accessfor households above <strong>and</strong> below the poverty l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the year 2000.Though poverty was greater <strong>in</strong> rural areas, <strong>in</strong>equality was greater <strong>in</strong> urbanareas. In rural areas 51% of households above the poverty l<strong>in</strong>e were us<strong>in</strong>gunprotected sources compared to 57% of households below the poverty l<strong>in</strong>e; arelatively small difference. In contrast, though only 12% of urban householdswere us<strong>in</strong>g unprotected sources, those households were twice as likely to bebelow the poverty l<strong>in</strong>e. In Dar es Salaam this <strong>in</strong>equality is even greater. Thoughonly 7% of households were recorded as us<strong>in</strong>g unprotected sources thesehouseholds were six times more likely to be those below the poverty l<strong>in</strong>e.Summary of recommendationsThe HBS recorded that 46% of rural households <strong>in</strong> the year 2000 were us<strong>in</strong>gwater from improved sources (up 11% from 1991). In urban areas the surveyrecords that 88% of households were us<strong>in</strong>g water from improved sources.However, <strong>in</strong> Dar es Salaam access to improved water sources had dropped by3% s<strong>in</strong>ce 1991. In addition the DHS recorded that urban households able to fetchwater <strong>in</strong> under 30 m<strong>in</strong>utes has dropped by 14% to 64% over the same period.The fact that this analysis relies so heavily on the data collected by the HBSis evidence that data quality <strong>and</strong> consistency across national surveys needs to beimproved. In order to improve consistency <strong>and</strong> comparability this studyrecommends a number of modifications to national surveys data collection. Ofthese, the five key recommendations are:1. differentiate between protected <strong>and</strong> unprotected water sources so thataccess to improved water sources can be measured.2. adopt the <strong>in</strong>dicator ‘time taken to fetch water’3. reth<strong>in</strong>k questions to capture the reality of the sanitation situation <strong>in</strong><strong>Tanzania</strong> e.g. ownership does not necessarily mean use of toilet facilities4. ensure that improved water <strong>and</strong> sanitation data is collected by the census<strong>and</strong> is analysed at the level of district5. ensure comparable formats of questions on water <strong>and</strong> sanitation issuesacross surveys <strong>and</strong> censuses<strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 20027

AcronymsCWIQDANIDADAWASADFIDDHSDPP-MoWLDEasEASTCESRFGTZHBSHIPCJICAKfWLGRPMoHMoWLDNBSO&MOPMLPMSPRSPRSPPWMIREPOARWSDTASTCRSTSEDUCLASUNDPUNICEFURoTVIPWAWAMMACore Welfare Indicator QuestionnairesDanish International Development AgencyDar es Salaam <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> Sewerage AuthorityDepartment for International DevelopmentDemographic <strong>and</strong> Health SurveyDirectorate of Policy <strong>and</strong> Plann<strong>in</strong>g - M<strong>in</strong>istry of <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> Livestock DevelopmentEnumeration AreasEastern Africa Statistical Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g CentreEconomic <strong>and</strong> Social Research FoundationDeutsche Gesellschaft fur Technische ZusammenarbeitHousehold Budget SurveyHighly Indebted Poor CountryJapan International Cooperation AgencyKreditanstalt fur WiederaufbauLocal Government Reform ProgrammeM<strong>in</strong>istry of HealthM<strong>in</strong>istry of <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> Livestock DevelopmentNational Bureau of StatisticsOperation <strong>and</strong> Ma<strong>in</strong>tenanceOxford Policy Management Limited<strong>Poverty</strong> Monitor<strong>in</strong>g System<strong>Poverty</strong> Reduction Strategy<strong>Poverty</strong> Reduction Strategy Paper<strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>and</strong> Welfare Monitor<strong>in</strong>g IndicatorsResearch on <strong>Poverty</strong> AlleviationRural <strong>Water</strong> Supply Database<strong>Tanzania</strong> Assistance Strategy<strong>Tanzania</strong> Christian Refugee Services<strong>Tanzania</strong> Socioeconomic DatabaseUniversity College of L<strong>and</strong>s, Architectural SciencesUnited Nations Development ProgrammeUnited Nations Childrens FundUnited Republic of <strong>Tanzania</strong>Ventilated, Improved Pit<strong>Water</strong>AidWafadhili Maji, Maendeleo ya Jamii na Afya8 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 2002

Introduction to poverty monitor<strong>in</strong>g forwater <strong>and</strong> sanitation1.01.1 <strong>Water</strong>, <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>All of those <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the water <strong>and</strong> sanitation sector know from experiencethat improvements <strong>in</strong> access to clean <strong>and</strong> safe water supplies <strong>and</strong> goodsanitation have extensive <strong>and</strong> multi-dimensional impacts on people’s lives. Asimpact studies have shown, better access to water <strong>and</strong> sanitation leads toimprovements <strong>in</strong>, for example: girls, boys, women <strong>and</strong> men’s health <strong>and</strong> hygiene;rural <strong>and</strong> urban livelihoods; children’s attendance at school; people’s, especiallywomen’s, psychological wellbe<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> social <strong>in</strong>teraction (<strong>Water</strong>Aid, 2000;Narayan, 1997; MoWLD, 2002).As <strong>Tanzania</strong>’s <strong>Poverty</strong> Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP) recognises, wecannot achieve the goals of poverty reduction <strong>and</strong> ultimately povertyelim<strong>in</strong>ation without provid<strong>in</strong>g every person with access to safe dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water(URoT, 2000). This access should be susta<strong>in</strong>able <strong>and</strong> to an improved source, thatis reliable all year round (adapted from the Millennium Development Goalssigned up to by <strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>in</strong> 2000). To meet the aim of universal access, the watersector has been identified as a priority sector for the poverty reductionstrategies <strong>and</strong> budgets. The <strong>Poverty</strong> Monitor<strong>in</strong>g System monitors whether suchaims are be<strong>in</strong>g reached.1.2 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>:Monitor<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>in</strong>formed poverty eradication strategiesFigure 1.2.1. <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> data<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation collection, analysis <strong>and</strong>dissem<strong>in</strong>ation through the PMSThe <strong>Poverty</strong> Monitor<strong>in</strong>g System (PMS) was developed <strong>in</strong> 2001 to “ensure theavailability of timely <strong>and</strong> reliable evidence on poverty” <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> (URoT,2001b). This evidence is required to determ<strong>in</strong>e whether activities implementedunder the National <strong>Poverty</strong> Eradication Strategy (URoT, 1997), <strong>Tanzania</strong>Assistance Strategy (TAS) (draft, 2001) <strong>and</strong> PRSP (URoT, 2000, URoT 2001a)are really improv<strong>in</strong>g the welfare of poor people <strong>in</strong> the country.The system advances a co-ord<strong>in</strong>ated national-level approach to data <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>formation collection, analysis <strong>and</strong> communication that focuses on the fourareas shown <strong>in</strong> figure 1.2.1 below. <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> sanitation data <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation istherefore collected by surveys <strong>and</strong> census, through rout<strong>in</strong>e or adm<strong>in</strong>istrativesystems <strong>and</strong> through commissioned pieces of research/analysis (see Tsikata <strong>and</strong>Mbil<strong>in</strong>yi, 2001 for overview of priorities for research). Improvements to thewater <strong>and</strong> sanitation rout<strong>in</strong>e data systems (see appendix 1.2.1 for a diagram of<strong>in</strong>formation flow) are, however, still be<strong>in</strong>g developed. Partly for this reason, <strong>and</strong>because surveys are an important data collection method, we focus on<strong>in</strong>formation ga<strong>in</strong>ed from surveys <strong>and</strong> census.Rout<strong>in</strong>e Data SystemsMoWLD - eg RWSDMoH - eg MTUHALocal Government Monitor<strong>in</strong>g DatabaseResearch <strong>and</strong> AnalysisParticipatory <strong>Poverty</strong> AssessmenstOther qualitative <strong>and</strong> community based researchSurveys <strong>and</strong> CensusHousehold Budget SurveyDemographic <strong>and</strong> Health SurveysCensusDissem<strong>in</strong>ationSensitisation <strong>and</strong>Advocacy<strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 20029

BOX 1.3.1 Indicators for <strong>in</strong>form<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Poverty</strong> Reduction/Eradication Strategies<strong>Poverty</strong> Reduction Strategy Paper• Population with access to safe water (for rural <strong>and</strong> urban)<strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>and</strong> Welfare Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Indicators• Percentage of households with access to adequate amount of safe dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water with<strong>in</strong> 400m• Percentage of households with access to adequate supplies of water with<strong>in</strong> 400m• Percentage of households with (i) toilet facility (ii) access to toilet facility• Percentage of urban households with access to garbage disposal facilities• Percentage of urban households with (i)access to sewage systems (ii) cesspool empty<strong>in</strong>g (iii) access to (waste)disposal facility (suggested)• Percentage of population contribut<strong>in</strong>g to water services1.3 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>:<strong>Poverty</strong> Monitor<strong>in</strong>g IndicatorsThe Vice President’s Office <strong>Poverty</strong> <strong>and</strong> Welfare Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Indicators (URoT1999) were developed to monitor the National <strong>Poverty</strong> Eradication Strategy.The PRSP has one water <strong>in</strong>dicator <strong>in</strong> its list of core <strong>in</strong>dicators for the sector(URoT, 2000, URoT 2001a). See box 1.3.1. Other monitor<strong>in</strong>g systems <strong>and</strong>strategies conta<strong>in</strong> variations of these ma<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dicators.A water <strong>and</strong> sanitation stakeholders’ workshop was held <strong>in</strong> September2001 reviewed the <strong>in</strong>dicators <strong>and</strong> highlighted gaps <strong>in</strong> both the list of <strong>in</strong>dicators<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> the data collection systems designed to measure the <strong>in</strong>dicators. Appendix1.3.1 details the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs. The plans for this study of national surveys evolvedfrom the September meet<strong>in</strong>g.1.4 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>: the study objectivesThis study was designed to <strong>in</strong>form <strong>Tanzania</strong>’s <strong>Poverty</strong> Reduction Strategy. Itexplores the changes <strong>in</strong> people’s access to water <strong>and</strong> sanitation <strong>in</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong><strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>and</strong> relationships between water <strong>and</strong> poverty. Due to access <strong>and</strong> thentechnical problems with some of the data, the depth of the analysis is limited <strong>in</strong>some aspects.The study brought together key national level stakeholders work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> thewater <strong>and</strong> sanitation sector <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g ones with strong l<strong>in</strong>ks to District <strong>and</strong>community based stakeholders. The collaborative work was led by theDepartment of Policy <strong>and</strong> Plann<strong>in</strong>g from the M<strong>in</strong>istry of <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong>Livestock Development (MoWLD) <strong>and</strong> <strong>Water</strong>Aid-<strong>Tanzania</strong> with astatistician contracted from EASTC. Other partners <strong>in</strong> the work <strong>in</strong>cluded:Government <strong>and</strong> UN• MoWLD (Departments of Rural<strong>Water</strong> Supply <strong>and</strong> <strong>Water</strong>Resources)• M<strong>in</strong>istry of Health (Departmentof Preventative Services)• UNICEF, UNDP, DFIDNGOs with water <strong>and</strong> sanitationfocus/programmes• Concern Worldwide• WATSANET• NETWASResearch organisations/ agencies• Eastern Africa StatisticalTra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Centre (EASTC)• National Bureau of Statistics(NBS)• UCLAS• REPOAOther poverty monitor<strong>in</strong>gactors• Local Government ReformProgramme• TSED10 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 2002

Data sources <strong>and</strong> their comparability 2.02.1 National household surveys usedSee appendix 2.1.1 for details of the surveys <strong>and</strong> their relevant variables.2.1.1 Household Budget Survey 1991 <strong>and</strong> 2000/1The Household Budget Surveys (HBS) collect data on key socio-economiccharacteristics of household members, household liv<strong>in</strong>g conditions, householdeconomic activity, <strong>in</strong>come <strong>and</strong> expenditure. The HBS has been carried out <strong>in</strong> 1969,1976/7, 1991 <strong>and</strong> 2000/1. It is planned for 2006 <strong>and</strong> 2011 (URoT 2001b). This studyonly used the 1991 <strong>and</strong> 2000/1 surveys for the follow<strong>in</strong>g reasons:• The raw data was only available <strong>in</strong> a readable format for 1991 <strong>and</strong> 2000/1surveys (see NBS <strong>and</strong> OPML, 2000 for details);• Complete sets of reports <strong>and</strong> questionnaires could not be located foreither the 1969 <strong>and</strong> 1976/7 surveys that detailed the methodology <strong>and</strong>sample weight<strong>in</strong>g used;• The questions <strong>and</strong> response options for water <strong>and</strong> sanitation used <strong>in</strong> theolder surveys are not comparable with the later surveys.Raw data sets for both the 1991 <strong>and</strong> 2000/1 surveys were obta<strong>in</strong>ed from theNational Bureau of Statistics. Both data sets used were those re-cleaned <strong>and</strong> reweightedfor the poverty analysis <strong>in</strong> 2002, rectify<strong>in</strong>g oversampl<strong>in</strong>g of certa<strong>in</strong>(particularly urban areas) <strong>and</strong> compensat<strong>in</strong>g for those areas not covered when thesample size was reduced mid-way through the HBS 2000.For water <strong>and</strong> sanitation, the key variables for the study are:• Ma<strong>in</strong> dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water supply for household• Toilet facilities used by household• Garbage disposal methods used by household• Distance (<strong>and</strong> time for 2000/1) to dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water source <strong>in</strong> the dry season• Expenditure on water2.1.2 Demographic <strong>and</strong> Health Surveys <strong>in</strong> the 1990sThe Demographic <strong>and</strong> Health Surveys (DHS) collect data on key health issuessuch as family plann<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>fant <strong>and</strong> child mortality, maternal <strong>and</strong> child health <strong>and</strong>nutrition <strong>and</strong> HIV/AIDS <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Zanzibar). The surveys werecarried out <strong>in</strong> 1992, 1994, 1996 <strong>and</strong> 1999 <strong>and</strong> are planned for 2004 <strong>and</strong> 2009 (URoT2001b). This study uses <strong>in</strong>formation from the household surveys from all foursurveys carried out <strong>in</strong> the 1990s <strong>and</strong> data from the women’s survey for the DHS1996. Raw data sets for all surveys were obta<strong>in</strong>ed from Macro International(www.measuredhs.com) although the National Bureau of Statistics also holdthem. All of the data sets used were weighted us<strong>in</strong>g the appropriate weightsconta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the surveys to rectify over-sampl<strong>in</strong>g of certa<strong>in</strong> areas, as directed byMacro International.Zanzibar figures have been removed for 1996 <strong>and</strong> 1999; the 1994 survey wasma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> only <strong>and</strong> 1992 the regions are classified <strong>in</strong> zones mak<strong>in</strong>g it impossible toremove the isl<strong>and</strong>s. It should be noted that the effect of <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Zanzibar <strong>in</strong> thesample for 1992 is likely to be small; <strong>in</strong> 1996 the percentage of households us<strong>in</strong>gpiped water <strong>in</strong> the sample <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Zanzibar was 0.8% higher than the sample not<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Zanzibar.For water <strong>and</strong> sanitation, the key variables for the study are:• Ma<strong>in</strong> dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water supply for members of the household• Toilet facilities the household has• Time taken to go to ma<strong>in</strong> dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water source, to collect water <strong>and</strong> return• Incidence of diarrhoea for <strong>in</strong>fants (past 2 weeks)<strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 200211

2.1.3 Population Census 1978 <strong>and</strong> 1988The Population Census (Census) collects basic demographic data for all people <strong>in</strong><strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>and</strong> more detailed population data plus <strong>in</strong>formation on hous<strong>in</strong>g conditionsfor a sample (about 1/4 of households). The census <strong>in</strong>formation used <strong>in</strong> the study isfrom those carried out <strong>in</strong> 1978 <strong>and</strong> 1988. The Population <strong>and</strong> Hous<strong>in</strong>g Census 2002is currently underway <strong>and</strong> the next is planned for 2012 (URoT 2001b). Onlyreports were used for the Census <strong>in</strong>formation although the vast data sets areaccessible through the NBS. The reports were sufficient for a rural <strong>and</strong> urbantrend analysis <strong>and</strong> the questions used prevented any useful more detailed analysis.For water <strong>and</strong> sanitation, the key variables are:• dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water source used <strong>and</strong>• toilet facilities owned2.1.4 Surveys referenced but not <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the analysisThe Labour Force Survey (eg 2000/1) does not, <strong>in</strong> its current state, give<strong>in</strong>formation on water <strong>and</strong> sanitation. The Agricultural Surveys were not <strong>in</strong>cluded.CWIQ (Core Welfare Indicator Questionnaires) were referred to for <strong>in</strong>dicatordevelopment but no data was <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the analysis as the survey’s methods arenot comparable <strong>and</strong> they are not national level surveys. Other surveys carried outby research <strong>in</strong>stitutions were also not <strong>in</strong>cluded for a range of reasons, primarilybecause the comparability of the ma<strong>in</strong> national surveys carried out by the NBSprovided enough challenges!2.2 Comparability <strong>and</strong> consistency of surveys2.2.1 Compar<strong>in</strong>g sample designsRefer to table 2.2.1 over the page, summarised below to compare the surveys used:• Coverage <strong>and</strong> estimates possible. The study must be ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> only <strong>in</strong>order for all surveys to be <strong>in</strong>cluded (remember<strong>in</strong>g DHS 1992 has to <strong>in</strong>clude Zanzibar).There is a huge range <strong>in</strong> survey sample size but all surveys give national (ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong>)<strong>and</strong> rural/urban estimates. Only the HBS allows Dar to be analysed separately.• Sample designs <strong>and</strong> weights. Sample designs are different for the differentsurveys. The DHS are based on Census enumeration areas. The HBS are based onthe National Master Sample orig<strong>in</strong>ally based on agro-economic zones <strong>and</strong> created <strong>in</strong>1988. The DHS <strong>and</strong> HBS are both weighted (though us<strong>in</strong>g different weight<strong>in</strong>gsystems) to rectify over-sampl<strong>in</strong>g of urban areas <strong>and</strong> some regions. The weight<strong>in</strong>g<strong>and</strong> re-weight<strong>in</strong>g of data has a significant effect on the figures. For example,percentage of households us<strong>in</strong>g piped water <strong>in</strong> 1991 as recorded by the HBS isreported to be:- 57.4% <strong>in</strong> the HBS 1991/2 report data tables (URoT, 1994b) (known to beun-weighted valid percentages although the report does not specify this)- 40.1% <strong>in</strong> basel<strong>in</strong>e development work (NBS <strong>and</strong> OPML, 2000) (withorig<strong>in</strong>al weight<strong>in</strong>g which did not sufficiently allow for rural-urbanproportions of the population)- 35.9% (re-weighted valid percentages used for HBS 2000/1 analysis <strong>and</strong>used for this study)• Errors. Sampl<strong>in</strong>g errors are estimated to be low although water <strong>and</strong>sanitation variables are not <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the estimation of sampl<strong>in</strong>g errors carried outfor the surveys (see United Republic of <strong>Tanzania</strong>, 1993; Bureau of Statistics <strong>and</strong>Macro International, 1997; National Bureau of Statistics <strong>and</strong> Macro InternationalInc., 2000; NBS <strong>and</strong> OPML, 2000). In all surveys, households <strong>in</strong> rural enumerationareas or survey clusters have reta<strong>in</strong>ed their rural status (rather than ga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g periurbanor urban status) despite the expansion of urban areas <strong>in</strong>to the countryside.This type of sample error is by nature more evident <strong>in</strong> the more recent surveys thanthose close to the 1988 Census. Similar non-sampl<strong>in</strong>g errors (for example, failure tolocate <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terview the correct household, misunderst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>gs of the questions - bythe <strong>in</strong>terviewer or respondent - <strong>and</strong> data entry errors) are likely for all surveys, areimpossible to avoid <strong>and</strong> difficult to evaluate statistically (Bureau of Statistics <strong>and</strong>Macro International, 1997).12 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 2002

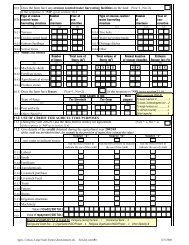

TABLE 2.2.1. Compar<strong>in</strong>g survey sample size <strong>and</strong> designSURVEY SAMPLE SIZE COVERAGE AND SAMPLE DESIGN(households)DISAGGREGATION POSSIBLECensus 1978 3,555,000 National 2 stage sampl<strong>in</strong>g:(ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Zanzibar) 1) Enumeration AreasTotal/rural/urbansystematically r<strong>and</strong>omly sampled<strong>in</strong> each region. 2) Eas divided <strong>in</strong>toclusters on basis of number ofhouseholds & population(max 600 pple)Census 1988 4,420,000 National S<strong>in</strong>gle stage sampl<strong>in</strong>g(ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Zanzibar) Pre survey enumeration- mapp<strong>in</strong>gTotal/rural/urbanhouseholds to give EAs . ThoseRegionalsurveyed selected based onsystematic equal probabilitysampl<strong>in</strong>gHBS 1991/2 4924 re-cleaned Ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> only National Master SampleMarch 2002. 4,290,332 Total/rural/Dar/other urban of 222 E A s (100 rural, 122 urban)re-weighted Mar 02 Disaggregation by demographic<strong>and</strong> poverty related variablespossibleHBS 2000/1 22,189 re-cleaned Ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> only Based on National Master SampleMar 02, 6,453,755 Total/rural/Dar/other urban but budget cuts reduced numberre-weighted Mar 02 Regional of households sampled, esp rural(average 1109 hhlds each) (7627 rural, 14551 urban)Disaggregation by demographic<strong>and</strong> poverty related variablespossibleDHS 1991/2 8327 hhlds (weighted) National Census enumeration areas(Ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Zanzibar)Urban/ruralDHS 1994 4023 hhlds (weighted) Ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> only Census 88 enumeration areasDHS 1996 7740 hhlds (weighted) National Census 88 enumeration areas8120 women (15-49) (ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Zanzibar)Rural, urban(for hhlds/women/men)DHS 1999 3615 hhlds (weighted) National Census 88 enumeration areas(ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Zanzibar)Total/rural/urbanNOTE: Sampl<strong>in</strong>g Error was not calculated us<strong>in</strong>g water <strong>and</strong> sanitation variables <strong>in</strong> any of the surveys.St<strong>and</strong>ard Error is not possible to estimate for the survey data used, prevent<strong>in</strong>g any plott<strong>in</strong>g of confidence <strong>in</strong>tervals fordata po<strong>in</strong>ts.<strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 200213

FIGURE 2.2.2. Percentage of Households us<strong>in</strong>g piped water as their ma<strong>in</strong> dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g source over time45.0% of households40.035.030.025.020.022373136343536 373915.010.05.0HBS 1977HBS 1978197919801981198219831984198519861987CENSUS 198819891990HBS 1991/2DHS 19921993DHS 19941995DHS 199619971998DHS 1999HBS 20002.2.2 Consistency of data sets collected through surveysThe graph <strong>in</strong> Figure 2.2.2 above takes households us<strong>in</strong>g piped water to check thecomparability of surveys through the consistency of the data obta<strong>in</strong>ed. Use of apiped source was used as it is easier for a respondent to identify a pipe/tapsource compared to identify<strong>in</strong>g a well or surface source which sometimes getconfused (see below). The graph highlights the different figures ga<strong>in</strong>ed from thedifferent surveys <strong>and</strong>, <strong>in</strong> particular, the reason for dropp<strong>in</strong>g the HBS 1976-7from the study (see reasons given above for this difference). The other figuresare generally consistent although the differences between the HBS 1991/2 <strong>and</strong>DHS 1991/2 <strong>and</strong> the DHS 1999 <strong>and</strong> HBS 2000/1 <strong>in</strong>dicate that only general trendsshould be read from the graphs; percentage changes from one survey to the nextshould not be quoted.2.2.3 Comparability of questions <strong>and</strong> response optionsThe table <strong>in</strong> appendix 2.2.3 relates the questions <strong>and</strong> response options of thema<strong>in</strong> surveys to the ma<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dicators for water <strong>and</strong> environmental sanitation (as<strong>in</strong> Box 1.3.1 plus others that ARE measurable). It shows the lack ofcomparability of surveys <strong>in</strong> terms of the questions that they ask <strong>and</strong> theresponse options allowed. For example:• Different response options for types of water source used are given <strong>in</strong> eachof the surveys - some focus on ownership of water po<strong>in</strong>ts, some on protection.Some of these are likely to be confused by respondents, for example ‘private’ownership - is this a tap or well owned by a household or one controlled by aprivate company/<strong>in</strong>dividual sell<strong>in</strong>g water?• HBS records distance <strong>and</strong> time to dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water source <strong>in</strong> the dry season;DHS records time to fetch water from the ma<strong>in</strong> dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g source• DHS measures the ownership of toilet facilities, HBS the use of facilitiesRelat<strong>in</strong>g the questions <strong>and</strong> response options to <strong>in</strong>dicators for the sectordemonstrates that:• Population with access to safe water (for rural <strong>and</strong> urban) is onlymeasured by the HBS <strong>and</strong> DHS 1999, <strong>and</strong> then only if this is taken to be use ofimproved water sources.• Percentage of households with access to water with<strong>in</strong> 400m is notmeasured by any survey14 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 2002

IMPLICATIONS FOR STUDY• The only classification possible for anytrend analysis us<strong>in</strong>g more than one type ofsurvey is: piped water, wells, spr<strong>in</strong>gs,ra<strong>in</strong>water, surface sources <strong>and</strong> other(unspecified or those rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g).• Only those <strong>in</strong>dicators <strong>in</strong> Box 2.2.3 canbe measured <strong>and</strong> the study heavily relies onthe HBS data sets as these record improvedwater sources.• We need to ensure consistency withpast surveys when recommend<strong>in</strong>gmodifications for the future.• The HBS response options for garbage disposal facilities do not provideuseful <strong>in</strong>formation. No survey gives data on use of sewerage systems• Misclassifications with<strong>in</strong> the NBS dur<strong>in</strong>g data entry mean that the water<strong>and</strong> hygiene expenditure data has been miscoded <strong>and</strong> these <strong>in</strong>dicators are notmeasurable. Entries <strong>in</strong> the HBS expenditure diaries for purchases from watervendors, for example, were classified as ‘bottled dr<strong>in</strong>ks, fruit juices <strong>and</strong> icecream’!S<strong>in</strong>ce the late 1990s, there has been a noticeable effort with<strong>in</strong> the NationalBureau of Statistics to make their survey questions more comparable (see DHS1999, HBS 2000/1, forthcom<strong>in</strong>g Census 2002). This is a positive move but itshould be noted that chang<strong>in</strong>g the response options for a questionnaire can haveserious implications for data consistency. The graph <strong>in</strong> Figure 2.2.3 below showsthe effect of chang<strong>in</strong>g the response options offered to those tak<strong>in</strong>g part <strong>in</strong> thedemographic <strong>and</strong> health surveys 1996 <strong>and</strong> 1999. In 1999 the well water optionswere altered to water from open or unprotected well AND water from coveredwell or borehole (<strong>in</strong> 1996 they were well <strong>in</strong> residence/yard/plot ANDpublic/private well). An open, unprotected well that is dug <strong>in</strong>to a river bed orperceived to be more of a hole <strong>in</strong> the ground rather than a public or private wellwas likely to have been classified as a surface source <strong>in</strong> 1996 but reclassified tothe well category <strong>in</strong> 1999.FIGURE 2.2.3. Change <strong>in</strong> the percentage of households us<strong>in</strong>g piped, well <strong>and</strong> surface sources for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water from 1992 to1999 (DHS 1992-99)45.040.035.038WELL% of households30.025.020.030242923292215.010.05.013SURFACE SOURCEHBS 1992 (91/2)1993DHS 19941995DHS 199619971998DHS 1999<strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 200215

BOX 2.2.3 Basic <strong>in</strong>dicators possible to use <strong>in</strong> analysis✔✔✔✔✔✔✔✔✔✔✔✔✔Percentage of households us<strong>in</strong>g different dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water sources as ma<strong>in</strong> source classified <strong>in</strong>to: piped, wells,spr<strong>in</strong>gs, surface sources, ra<strong>in</strong>water, unspecified othersPercentage of households us<strong>in</strong>g improved dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water source as ma<strong>in</strong> source (commonly used as measure of‘access to safe water’, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g piped water, protected wells <strong>and</strong> covered spr<strong>in</strong>gs)Households with piped water <strong>in</strong>to the home (house or plot)Percentage of households liv<strong>in</strong>g with<strong>in</strong> 1km of a dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water supply <strong>in</strong> the dry seasonAverage distance to water supplyPercentage of households liv<strong>in</strong>g with<strong>in</strong> x number of m<strong>in</strong>utes from dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water supply <strong>in</strong> the dry seasonPercentage of households tak<strong>in</strong>g x number of m<strong>in</strong>utes to reach the source, collect water <strong>and</strong> return homeAverage time spent fetch<strong>in</strong>g waterPercentage of households us<strong>in</strong>g different toilet facilities (flush, latr<strong>in</strong>es, ‘other’ facilities)Percentage of households not us<strong>in</strong>g toilet facilitiesPercentage of households dispos<strong>in</strong>g of rubbish by throw<strong>in</strong>g it outside or by putt<strong>in</strong>g it <strong>in</strong> a pit or b<strong>in</strong>Household expenditure on water (only estimate possible due to mis-classification of water vendors)Percentage of members of households surveys suffer<strong>in</strong>g from diarrhoea <strong>in</strong> 4 weeks prior to survey.2.3 Other data sources for referenceAlthough the study focuses on data from the ma<strong>in</strong> national surveys <strong>and</strong> census,some other qualitative <strong>and</strong> quantitative research <strong>and</strong> monitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formationwas <strong>in</strong>cluded:• Rout<strong>in</strong>e/adm<strong>in</strong>istrative data generated by the M<strong>in</strong>istry of <strong>Water</strong><strong>and</strong> Livestock Development. Official coverage figures for population withaccess to water from a water scheme used by the Department of Policy <strong>and</strong>Plann<strong>in</strong>g were obta<strong>in</strong>ed from the annual budget speeches given <strong>in</strong> Parliament bythe M<strong>in</strong>ister (Jamhuri ya Muungana wa <strong>Tanzania</strong>, 1986, 1988, 1992, 1996, 1998,2000, 2001; URoT, 1987). These are used to compare survey <strong>and</strong> rout<strong>in</strong>e figures.• Participatory <strong>Poverty</strong> Assessment (Narayan, 1997) <strong>and</strong> Look<strong>in</strong>gBack (<strong>Water</strong>Aid, 2000). Both participatory assessments generated<strong>in</strong>formation on water <strong>and</strong> sanitation <strong>and</strong> poverty <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> that providedvaluable <strong>in</strong>sights <strong>in</strong>to some of the trends.2.4 Quantitative data analysis - po<strong>in</strong>ts to rememberThe strengths <strong>and</strong> weaknesses of survey-based approaches have been reviewedby many <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Calvalho <strong>and</strong> White, 1997 (<strong>in</strong> Appleton <strong>and</strong> Booth, 2001).Surveys provide data that can be aggregated <strong>and</strong> the reliability of results can bemeasured. However, quantitative <strong>in</strong>formation should always be taken as<strong>in</strong>dicative not truth-reveal<strong>in</strong>g. This is because:• errors are <strong>in</strong>evitable <strong>in</strong> survey design, implementation <strong>and</strong> analysis,particularly <strong>in</strong> a country the size of <strong>Tanzania</strong>;• surveys miss what is not easily quantifiable;• household surveys fail to capture <strong>in</strong>tra-household allocation.The regional level disaggregation possible with the HBS also fails to capture<strong>in</strong>tra-regional, <strong>in</strong>tra-District, <strong>in</strong>tra-ward <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>tra-village/street differences.Therefore, this study aims to highlight broad trends, to reveal areas for furtherexploration with qualitative research <strong>and</strong> to draw recommendations forimprov<strong>in</strong>g the way surveys capture water <strong>and</strong> sanitation data <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation.16 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 2002

<strong>Water</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 3.03.1 Longer-term trends <strong>in</strong> dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water source use - for rural<strong>and</strong> urban areasThe ma<strong>in</strong> trend analyses that it is possible to carry out over the differentsurveys from 1978 to 2001 (see table 3.1) are:• Households us<strong>in</strong>g piped water as the ma<strong>in</strong> source for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g 1978 to 2001• Households us<strong>in</strong>g well water as the ma<strong>in</strong> source for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g 1978 to 2001• Households us<strong>in</strong>g surface water sources as the ma<strong>in</strong> source for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g1991-2001Households us<strong>in</strong>g ra<strong>in</strong>water <strong>and</strong> spr<strong>in</strong>gs are also possible to record. Howeverthe use of ra<strong>in</strong>water as a ma<strong>in</strong> dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water source is very low (0.0-0.3%).Spr<strong>in</strong>gs will be referred to <strong>in</strong> section 3.1.2.TABLE 3.1. Percentage of households us<strong>in</strong>g piped, well, ra<strong>in</strong>, spr<strong>in</strong>g, surface <strong>and</strong> other dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water sources 1978-2000/1PIPEDWELLRAINSPRINGSURFACEOTHERTOTALRURALURBAN TOTALRURALURBAN TOTALRURALURBAN TOTALRURALURBAN TOTALRURAL URBAN TOTALRURALURBAN TOTALRURAL URBAN TOTALCensus1978*27.788.037.246.48.440.4749678Census1988*18.579.231.560.517.551.3799783HBS199124.578.835.939.213.833.90.10.10.111.80.39.423.22.418.81.24.71.9100100100DHS1991/219.478.633.835.113.329.80.30.00.211.81.39.329.94.923.93.41.83.0100100100DHS199420.282.935.434.213.529.20.10.00.116.60.712.728.92.222.50.00.70.2100100100DHS199624.777.536.432.915.428.90.20.00.115.41.912.426.94.521.90.01.10.2100100100DHS199922.079.637.146.913.838.30.00.00.013.51.810.517.32.013.30.12.80.8100100100HBS2000/128.478.939.339.715.634.50.20.20.215.32.012.415.82.112.80.71.20.8100100100* Census 1978 <strong>and</strong> 1988 gives ony ‘piped’, ‘well’ <strong>and</strong> ‘other’ as optionsNOTE: us<strong>in</strong>g valid percentages. None of the surveys show significant ‘miss<strong>in</strong>g’ data for the source variables3.1.1 Use of piped water for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g 1978 to 2001The percentage of households us<strong>in</strong>g piped water supplies often gives an<strong>in</strong>dication of :• Those covered by larger scale water schemes <strong>and</strong> therefore the recipientsof large scale government or development assistance <strong>in</strong>vestment;• Those us<strong>in</strong>g an improved source which <strong>in</strong> some, particularly urban, areasis treated for improved water quality <strong>and</strong> often brought closer to people’shomes for easier access;• Those more likely to be pay<strong>in</strong>g for water (s<strong>in</strong>ce the new water policy<strong>in</strong>volves cost shar<strong>in</strong>g) as piped schemes, especially those distribut<strong>in</strong>gwater from deep bore holes with pump eng<strong>in</strong>es, have higher operation <strong>and</strong>ma<strong>in</strong>tenance costs.It should be noted that piped water alone does not show the percentage ofhouseholds access<strong>in</strong>g improved sources as protected wells <strong>and</strong> spr<strong>in</strong>gs are usedby many, especially rural, households.<strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 200217

FIGURE 3.1.1. Change <strong>in</strong> percentage of households on <strong>Tanzania</strong>n Mail<strong>and</strong> us<strong>in</strong>g piped water for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g 1978-2001 by urban<strong>and</strong> rural10090.080.070.0888079 7983778079URBAN PIPED% of households60.050.040.030.020.039373636 3735313428 2825252219 2018TOTAL PIPEDRURAL PIPED10.0CENSUS 1978197919801981198219831984198519861987CENSUS 198819891990HBS 1991/2DHS 19921993DHS 19941995DHS 199619971998DHS 1999HBS 2000Refer to graph <strong>in</strong> figure 3.1.1. It shows:• The percentage of total households <strong>in</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> us<strong>in</strong>g pipedwater for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g as their ma<strong>in</strong> source fell through the 1980s but hasrisen aga<strong>in</strong> slightly through the 1990s (HBS 1991 to 2000/1 shows a 3%<strong>in</strong>crease). This rise through the 1990s was slight but steady - thefluctuations are as likely to be due to survey sample design as they are tobe due to changes <strong>in</strong> access.• This total households’ trend mirrors that of rural households due to<strong>Tanzania</strong>’s population be<strong>in</strong>g predom<strong>in</strong>antly rural. The urban trend,however, decl<strong>in</strong>es through the 1980s but rema<strong>in</strong>s more consistent throughthe 1990s rather than ris<strong>in</strong>g.The percentage figures for rural households do not show a different situation <strong>in</strong>2000/1 from 1978 (both 28%) (sources: HBS 2000/1 data <strong>and</strong> Census 1978 <strong>in</strong>URoT 1994a). The percentage of urban households us<strong>in</strong>g piped water <strong>in</strong> 2000/1appears to be lower than that <strong>in</strong> 1978. However, consider the population growthover this period. In 1978 the population of the ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> was around 17 million;<strong>in</strong> 2000 it was around 32 million (Bureau of Statistics, 1994; HBS 2000/1). Thismeans that <strong>in</strong> real terms more people <strong>and</strong> more households used piped supplynow than <strong>in</strong> 1978.• The rural-urban disparity is vast throughout the period covered. Compar<strong>in</strong>gthe disparity <strong>in</strong> 1978 <strong>and</strong> 2000/s shows that perhaps the gap has reduced but<strong>in</strong> rural areas <strong>in</strong> 2000/1, some 28% of households used piped water <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>urban areas just under 80% used piped water (source: HBS 2000/1).WHY THE CHANGE?• Technical explanation: Many householdsclassified as rural may well be peri-urban orurban (with higher piped use). This is because,despite us<strong>in</strong>g advanced weight<strong>in</strong>g systems torectify sample design biases, the urban/ruralclassification of enumeration areas or clustersdoes not allow for all expansions of urbanareas.• Changes <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>and</strong> policy: In the1970s there was significant <strong>in</strong>vestment pipedschemes that gradually ceased to functiondur<strong>in</strong>g the 1980s (URoT, 1994a; DPP-MoWLDpers comm). In the 1990s a new National<strong>Water</strong> Policy that focused on improvedoperation, ma<strong>in</strong>tenance <strong>and</strong> management ofschemes was set <strong>and</strong> there has been<strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong>vestment particularly <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong>geographical areas (DPP-MoWLD, pers comm;Jamhuri ya Muungana wa <strong>Tanzania</strong> 1986,1988, 1990, 2000).• Increas<strong>in</strong>g will<strong>in</strong>gness <strong>and</strong> ability topay: As many piped water schemes require apayment from the household either per bucketor on a monthly/annual basis, the <strong>in</strong>creaseduse of piped water could be the result of morehouseholds see<strong>in</strong>g the benefits (for health ortheir livelihood, for example) of us<strong>in</strong>g improvedrather than unprotected water sources <strong>and</strong>be<strong>in</strong>g more able to contribute f<strong>in</strong>ancially.18 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 2002

FIGURE 3.1.2. Change <strong>in</strong> percentage of households us<strong>in</strong>g wells as a dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g watersource <strong>in</strong> rural <strong>and</strong> urban areas of <strong>Tanzania</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> (a) Census 1978-1988 <strong>and</strong> (b)HBS 1991-2000/170.060.060RURAL WELL% of households50.040.030.0464051TOTAL WELL20.018URBAN WELL10.080CENSUS 1978 CENSUS 198870.060.050.0% of households40.030.039344035RURAL WELLTOTAL WELL20.010.01416URBAN WELL0HBS 1991 HBS 2000WHY THE CHANGE IN WELL USE?It is difficult to draw out explanations <strong>in</strong>terms of <strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>in</strong> groundwaterdevelopment as there is no way of know<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> most of the surveys (especially Census)whether or not the sources have beenimproved. Households resort<strong>in</strong>g to wells fordr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water as their piped waterschemes broke down <strong>in</strong> the 1980s isapparent (URoT, 1994a) but there does notappear to have been a shift back <strong>in</strong> the1990s. This could be because nosatisfactory alternative is available to thehouseholds.3.1.2 Use of well water for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g 1978 to 2001It is not possible to look at the longer-term trends <strong>in</strong> more detail than ‘use ofwells for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water’. The trends <strong>in</strong> the data are affected by changes <strong>in</strong>survey questions <strong>in</strong> the DHS (see section 2.2.3) <strong>and</strong> by different responseoptions <strong>in</strong> the different surveys (the censuses ask about use of piped, wells orother whilst the other surveys are more specific about what the ‘other’ watersources are). For these reasons, the graphs <strong>in</strong> figures 3.1.2 (a) <strong>and</strong> (b) belowshow only Census <strong>and</strong> HBS trends <strong>and</strong> only the general trends should be notedas the percentages are not comparable. These graphs show:• The use of wells for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water <strong>in</strong>creased through 1980s <strong>in</strong> rural <strong>and</strong>urban areas. (URoT, 1994a).• In the 1990s, there is little change evident <strong>in</strong> the percentage ofhouseholds us<strong>in</strong>g wells for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water <strong>in</strong> both rural <strong>and</strong> urban areas.• Remember<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> population over the period studied, manymore people <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> use well water for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> 2000/1 than <strong>in</strong>1978.<strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 200219

The percentage of households us<strong>in</strong>g spr<strong>in</strong>gs for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g fluctuates between 9.4-12.7% through the 1990s (see table 3.1) though the HBS shows a clearer <strong>in</strong>crease<strong>in</strong> their use. As with wells, perceptions of whether or not the source is a spr<strong>in</strong>g,well or pond differ.3.1.3 Use of surface water for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g 1978 to 2001Surface water sources (dams, lakes, ponds, rivers <strong>and</strong> streams) are generallyunprotected <strong>and</strong> often deemed to be ‘unsafe’ for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g, contam<strong>in</strong>ated byanimal, human <strong>and</strong> agricultural waste. Households us<strong>in</strong>g surface water sourcesmake up a large component of those us<strong>in</strong>g unprotected sources (the categorythat also <strong>in</strong>cludes unprotected wells <strong>and</strong> spr<strong>in</strong>gs, see section 3.2.1). Theexistence of surface water sources for use, however, depends on the area:semiarid zones are far more likely to have unprotected groundwater sourcesrather than surface ones.It is unfortunate that the Census questions do not provide data for surfacesource use from 1978 to 1988. Figures 3.1.3 (a) <strong>and</strong> (b) above show:• Between 1991 <strong>and</strong> 2001 there has been a reduction <strong>in</strong> the percentage ofhouseholds us<strong>in</strong>g surface water for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g, ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong> rural areaswhere more households use surface sources than <strong>in</strong> urban areas.• This trend is evident <strong>in</strong> both the DHS <strong>and</strong> the HBS. The DHS figures areaffected by question word<strong>in</strong>g but the change produced data moreconsistent with the HBS.FIGURE 3.1.3. Change <strong>in</strong> percentage of rural <strong>and</strong> urban households us<strong>in</strong>g surfacesources for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water on <strong>Tanzania</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> 1991-2000 (a) DHS <strong>and</strong> (b) HBS.40.035.0% of households30.025.020.015.030 292423272217RURAL SURFACE10.013TOTAL SURFACE505242URBAN SURFACEDHS 91/2INCL. ZANZIBAR1992 1993 DHS 94 1995 DHS 96HH - SCHEDULE1997 1998 DHS 9940.035.0% of households30.025.020.015.010.023191613RURAL SURFACETOTAL SURFACE502 2URBAN SURFACEHBS 91/2 HBS 200020 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 2002

FROM SURFACE TO PIPEDSOURCESIt is from surface to piped source use thatthe shift appears to have occurred <strong>in</strong> the1990s for possible reasons covered <strong>in</strong>section 3.1.1.It is clear that a more detailed study must focus on change over the 1990s <strong>and</strong>it must be accepted that it is necessary to rely on either the HBS or the DHS(depend<strong>in</strong>g on the <strong>in</strong>dicator be<strong>in</strong>g explored). It should be noted that <strong>in</strong> thefuture, given the move towards comparable surveys, a more <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g longertermanalysis should be able to be carried out.3.2 Use of improved water sources as an estimation ofaccess to safe water3.2.1 What do we mean by access to safe water?The <strong>in</strong>dicator ‘population with access to safe water’ is one of the core PRSP<strong>in</strong>dicators (URoT, 2001b). But what do we mean by safe? Ideally the waterquality of every water source <strong>in</strong> the country would be tested <strong>and</strong> recorded byDistrict level water <strong>and</strong> sanitation staff. The new national water policy <strong>and</strong> theplanned activities <strong>in</strong> the PRSP identify water quality monitor<strong>in</strong>g as a priority<strong>and</strong> databases are under construction that would store the <strong>in</strong>formation (egRural <strong>Water</strong> Supply Database). Given the issues of resources <strong>and</strong> capacity <strong>in</strong> acountry the size of <strong>Tanzania</strong>, measur<strong>in</strong>g quality is unlikely to be achieved on alarge scale for a long time. It could also be questioned whether this is a feasiblepriority for budgets aimed at poverty reduction, given the commonly acceptedpr<strong>in</strong>ciple that a larger quantity of water, rather than higher quality is likely tohave a bigger impact for people’s health (Cairncross <strong>and</strong> Feacham, 1988).In the absence of quality data, we need to take the commonly used approachof classify<strong>in</strong>g water sources <strong>in</strong>to ‘better’ <strong>and</strong> ‘worse’ for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g - at best onlyan estimation of relative safeness. Even then, there is no perfect classificationsystem. Pipes could be pip<strong>in</strong>g water from a contam<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>and</strong> untreated source.Deep boreholes <strong>and</strong> sealed shallow wells can both be polluted by nearby latr<strong>in</strong>esor sal<strong>in</strong>e water. Some open wells <strong>and</strong> surface water sources have clean waterwith very low faecal coliform counts. The suitability of ra<strong>in</strong>water for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>gcan depend on air pollution levels as well as method of storage. A very generalclassification is sufficient, as, even if the water source is protected, treated <strong>and</strong>‘safe’ to dr<strong>in</strong>k, contam<strong>in</strong>ation of the water can still occur dur<strong>in</strong>g transportationor storage <strong>in</strong> the home. The general classification system outl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the boxbelow was agreed upon with the Department of Policy <strong>and</strong> Plann<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> appliedfor the study (Mrs Naomi Lupimo, Mr Felix Ngamlagosi, Mr Shirima <strong>and</strong> MyNyenza, personal communication, Nov 2001-Mar 2002).WATER SOURCESImprovedPIPED• All piped water - <strong>in</strong>to the hous<strong>in</strong>gunit or plot, <strong>in</strong>to a neighbour’shouse, to a community st<strong>and</strong>post,to a privately-run water po<strong>in</strong>t.PROTECTED• Protected wells -boreholes/tubewells,medium/shallow wells withh<strong>and</strong>pumps• Covered spr<strong>in</strong>gsNot ImprovedUNPROTECTED• Unprotected wells• Uncovered spr<strong>in</strong>gs• Surface sources - dams, ponds <strong>and</strong>lakes, rivers <strong>and</strong> streamsOTHER(those not possible to classify)• Ra<strong>in</strong>water (as not recordedwhether stored <strong>in</strong> sealed or opentank)• Other unspecified sources (likelyto <strong>in</strong>clude tankers, water vendors,bottles which until recorded as aseparate category cannot beclassified.<strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Sanitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 200221