The Last Fugitive (pdf file) - Wisconsin Alumni Association

The Last Fugitive (pdf file) - Wisconsin Alumni Association

The Last Fugitive (pdf file) - Wisconsin Alumni Association

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

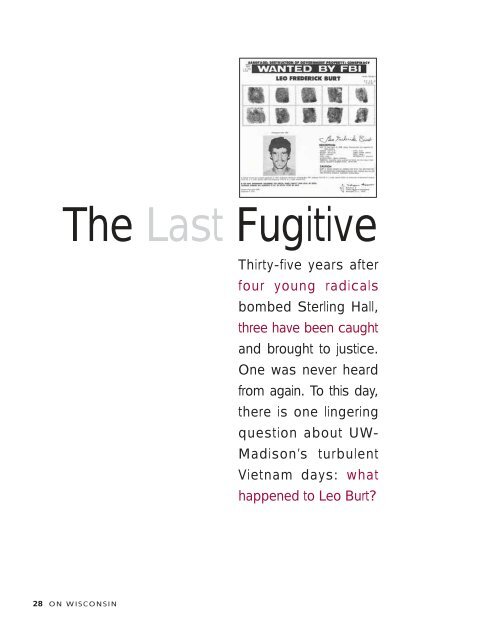

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Last</strong> <strong>Fugitive</strong>Thirty-five years afterfour young radicalsbombed Sterling Hall,three have been caughtand brought to justice.One was never heardfrom again. To this day,there is one lingeringquestion about UW-Madison’s turbulentVietnam days: whathappened to Leo Burt?28 ON WISCONSIN

By Doug Moe ’79<strong>The</strong> tips started comingalmost immediately.On October 31, 1970, two monthsafter a bomb exploded outsideSterling Hall on the UW-Madisoncampus, a waitress in a restaurantin Cleveland, Ohio, thought one ofher customers was Leo Burt, one offour men wanted in connection withthe bombing. She had seen his faceon an FBI Ten Most Wanted poster.Later that night, the customer fromthe restaurant came out of a Clevelandmovie theater, where he had justwatched Easy Rider. As he started toopen his car door, several uniformedpolice officers approached, guns drawn,and told him to put his hands over hishead. An FBI agent approached himand said, “You’re being charged as afugitive from justice.”After an hour of questioning, authoritiesrealized that the man was a secondyearlaw student named RichardRoutman, and not a notorious fugitive.Today, Routman is an attorney inKansas, and every once in a while, hewonders whatever became of Leo Burt.In 2003, thirty-three years after thatHalloween night in Cleveland, FBI specialagent Kent Miller got a call fromDenver. Someone had tipped police thata homeless man in the area might beBurt. Miller, who had worked the Burtcase for fifteen years out of the bureau’sMadison office, compared a photographof the Denver man to age-enhancedimages of Burt the bureau had made.<strong>The</strong>re were resemblances, although thehomeless man’s hair was longer.“He was real mysterious,” Millerrecalls. “He wouldn’t stay in the samehomeless shelter more than four or fivenights, wouldn’t tell anybody where hewas from.”<strong>The</strong> FBI enlisted an employee ofthe homeless shelter, who managed toretrieve a soda can the man had held.But the prints did not match. <strong>The</strong> homelessman was not Leo Burt.<strong>The</strong> tips keep coming, but they arealways wrong.This summer, thirty-five yearswill have passed since the August nightwhen four young radicals parked a vanfull of explosives in the driveway outsideSterling Hall. Targeted at the ArmyMath Research Center as a protestagainst U.S. involvement in the VietnamWar, the bomb killed Robert Fassnacht,a thirty-three-year-old postdoctoralresearcher in physics, and touched off anFBI manhunt for the bombers.Three men who carried out thebombing — erstwhile UW student KarletonArmstrong, his brother DwightArmstrong, and then-freshman DavidFine — were all eventually arrested,served time in prison, and have gotten onwith their lives. But their suspectedaccomplice, Leo Frederick Burt x’70,remains at large, making him perhaps thelast fugitive of the Vietnam era. Thousandsof tips have been investigated,hundreds of theories advanced, and themystery of Burt has only deepened.After he published Rads, his 1992book about the bombing, newspaperreporter Tom Bates MA’68, PhD’72thought he might hear from Burt. Whenhe didn’t, Bates grew even more fascinatedby the fugitive. In 1995, Bateswrote a long story for a newspaper inOregon, claiming Burt was theUnabomber, the domestic terrorist whokilled three people and injured dozensmore with bombs, usually mailed, from1978 to 1995. Bates based his claimlargely on similarities between theUnabomber’s “Manifesto,” which hadbeen recently published by the New YorkTimes and Washington Post, and an articlewritten by Burt for the left-wing journalLiberation after he disappeared into theunderground in 1972. <strong>The</strong>re were strikingsimilarities in the prose, but the maneventually arrested as the Unabomberwas Ted Kaczynski, not Leo Burt.Through the years, there have beenrumors of sightings — in Norman, Oklahoma,in the early 1970s; in Algeria in1972; and in Costa Rica in 1990. Nonehave panned out. If anything, it is theutter lack of credible information onwhat has become of Burt that most distinguishesthe case.That’s what struck Allan Thompson,the Madison FBI agent who handled the“Leo simply disappeared.investigation prior to Miller, about thecase when I talked to him in 1995. “I didfugitive work for twenty-three years. Inevery case I worked, someone in thewoodwork knew where the person was.Family, friends — somebody,” he toldme. “With Burt, there was an intenseinvestigation of his parents and relatives.Nothing came of it. Not one iota or indicationin twenty-five years that he’s beensighted, heard from, or spoken to.”But if Leo Burt has vanished, theinterest in him has not. Joe Brennan, Jr.,a thirty-six-year-old student in the graduatewriting program at Johns HopkinsUniversity, is currently revising a lengthymanuscript about Burt, with the workingtitle <strong>The</strong> <strong>Last</strong> Radical. Brennan’s interestin Burt comes from his father, who was aclassmate and rowing teammate of Burtat Monsignor Bonner High School inPennsylvania. Brennan thinks Burt’supbringing, and especially his involvementin rowing, is critical to understandingwhat happened in August 1970 andperhaps the years since.Burt was born April 18, 1948, into amiddle-class, Catholic Philadelphia family.He and his six siblings grew up in abrick bungalow, across the street from acemetery. Leo was an altar boy, and Fridaydinners in the Burt home were fishSUMMER 2005 29

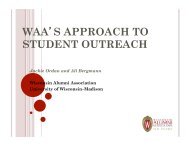

In 1970, Burt joined fellowradicals (from left) KarletonArmstrong, DwightArmstrong, and David Fineas part of the New Year’sGang, which vowed towreak havoc on operationsit saw as complicit in theVietnam War. <strong>The</strong> bomb atSterling Hall did little damageto its intended target,the U.S. Army MathResearch Center, but killeda researcher who wasworking inside the building.Burt’s co-conspiratorsall have been captured andsentenced for their roles inthe attack.UPI/BETTMANNor meatless spaghetti. He was a decentstudent, but it was crew — a widely popularsport around Philadelphia in thosedays — that interested him most. “<strong>The</strong>central thing in his life was rowing,” saysBrennan.A number of East Coast universitieswanted Burt to row for them, but hechose <strong>Wisconsin</strong>, which under coachRandy Jablonic ‘60 had established itselfas one of the best crew programs in thecountry. “He went to Madison solely tobe part of the men’s rowing team,” Brennansays. “He wanted to be with the best.It was a fateful decision.”Fateful because while Burt enjoyedsome success in his first year rowing inMadison, the hard reality was that at fivefeet, eleven inches tall, he was shorterthan the raw, big-boned kids Jablonicfavored. It was physics: a tall man canmove a boat faster than a shorter one.Burt’s experience and his intensity —remarked on by all who knew him —carried him for a time. He could outworkanyone and became a weight room legend.Yet by his junior year, with the Badgersscheduled for a big race out east,Burt was dropped from the travelingsquad. While he didn’t quit then, hebegan to clash with Jablonic, and whenthe coach told him to get a haircut, Burtcleaned out his locker.“His whole life was being a varsityrower,” Brennan says. “It left a hugehole.”Tim Mickelson ’71, a rower originallyfrom Deerfield, <strong>Wisconsin</strong>, may havebeen Burt’s best friend on the team, havingspent the summer of 1968 with Burtand his family in Pennsylvania, wherethey trained for Olympic trials and thecoming season. Mickelson remembersBurt as someone who never fought andrarely argued with anyone, even in thesometimes heated and competitiveatmosphere of the locker room. “Never<strong>The</strong> others rememberedBurt weeping in theback of the car whenthe radio delivered thenews a man had died.But then DwightArmstrong sensed achange. He lookedat Burt and thought,“He’s cold as steel.”swore, never told a dirty joke, never hada date, as far as I know,” Mickelsonrecalls. “It was rowing and studies. Leowas a good, but not great, student, andhe studied a lot.”When Burt left the team, he andMickelson remained friends, while seeingeach other less. “He let his hair grow andstarted writing a lot for the Daily Cardinaland SDS [Students for a DemocraticSociety],” Mickelson says. “At somepoint, he started believing what he waswriting.”Political activism was hard to avoidon campus in 1969. Two years earlier,student demonstrations against the DowChemical company had erupted intobloody riots. After he left the crew,Burt’s circle refocused around DailyCardinal reporters and the anti-waractivists he met while covering protests.He forged friendships with Fine andKarl Armstrong. “It became another culture,like rowing, for him to immersehimself in,” Brennan says.In the spring of 1970, when newsbroke that the National Guard had shotfour students during a protest at KentState University, the already edgy UW-Madison campus erupted. While coveringa melee between police and studentson Bascom Hill, Burt was beaten bypolice. And with that, he was no longeran observer.Over beers at the Nitty Gritty, Burttalked politics and revolution with theArmstrong brothers and Fine. “It was achance to be part of something biggerthan himself, yet be a big part of it himself,”says Brennan. <strong>The</strong>ir discussionsturned to the Army Math ResearchCenter, which had recently received a$1.8 million contract from the U.S.Department of Defense, and they startedto plot. Something had to be done.30 ON WISCONSIN

From the underground, thebombers wrote in the radicaljournal Kaleidoscopethat they regretted thedeath of Robert Fassnacht,but remained defiant thattheir actions were necessaryas part of a “worldwidestruggle to defeatamerikan imperialism.”In the predawn hours of August24, 1970, Kent Miller was working as asupport employee for the FBI in hishometown of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.In those days, FBI offices wererequired to test their teletype machinesevery twenty-four hours, and on thatnight, Miller was supposed to send messagesto the office in Milwaukee.“I’m merrily talking to this guy [byteletype],” Miller recalls, “and he sends amessage back that the phone was ringing.He comes back and says, ‘Big explosionat the university. Got to go.’ ”It was big, all right. <strong>The</strong> blast at SterlingHall killed Fassnacht and causedmore than $6 million in damages. But italso changed the course of Miller’s life.Eighteen years later, he would be inMadison, leading the FBI’s ongoinginvestigation, which by then centered onBurt, the only suspect whom they hadn’tsucceeded in finding.After planting the bomb, Burt, theArmstrongs, and Fine had packed into asmall Corvair and headed north out ofMadison, toward Sauk County. <strong>The</strong> otherslater remembered Burt weeping inthe back seat when the radio deliveredthe news that a man had died in thebombing. But then, as they sat on a bluffnear Devil’s Lake, Dwight Armstrong —as he would later tell author Tom Bates— sensed a change in Burt. <strong>The</strong> twentytwo-year-old,who had absorbed thework of the existential philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, reinvented himself as thesun came up. Armstrong looked at Burtand thought, “He’s cold as steel.”<strong>The</strong> four actually drove back toMadison, lying their way out of a potentialjam when they were stopped by SaukCounty police, before heading for NewYork. <strong>The</strong>y split up in Toledo; Karl andDwight kept the car and dropped Fineand Burt at the Greyhound station, withan agreement to meet a week later inTimes Square.That meeting never came off. WhileFine and Burt did go to New York, theywere intent on getting out of the UnitedStates. From New York, Burt sent a dispatchto the Madisonunderground paperKaleidoscope, whichlamented the death ofFassnacht but said:“<strong>The</strong> destruction ofAMRC was not anisolated act by‘lunatics.’ It was aconscious actiontaken in solidaritywith ... all otherheroic fightersagainst U.S. imperialism.”Burt alsowrote his parentsin Pennsylvania.He told them he waslooking for journalism work in NewYork City and added, “Did you hearabout the explosion in <strong>Wisconsin</strong>? Ididn’t get to see it, but you could hear itfar away.”From New York, Fine and Burthitched a ride with a friend to Boston,where they spent a night with Fine’s sister.According to Bates in Rads, fromthere the pair got a ride into Canada,checking into a rooming house in Peterborough,sixty miles northeast ofToronto. <strong>The</strong>y had only been there a daywhen the Royal Canadian MountedPolice appeared at the door. Bates wrote:“David and Leo hurriedly discardedtheir wallets with their IDs, useless nowthat they had registered with them, andexited by a rear window. <strong>The</strong>n theyparted company. David hitchhiked southand west, heading for the border crossingat Detroit.”Bates’s next sentence echoes acrossthirty-five years: “Leo simply disappeared.”Meanwhile, at a rowing event inCanada a few days after the bombing,Mickelson was approached by mountedpolice, who wanted to know if he’d heardfrom Burt. <strong>The</strong>y believed Burt was stillin Canada and might try to contact hisfriend for money. Mickelson recalls feeling“total surprise” when he heard hisfriend might be involved. He’d not beencontacted, but authorities would remaininterested in their friendship, followingup repeatedly over the next few years.Before the decade was out, the Armstrongsand Fine would be apprehended.All four of the alleged bomberswere immediately put on the FBI’sfamous Ten Most Wanted list, whichbrought the intense heat of a nationwidemanhunt on them. Since the debut ofthe list in 1950, more than 90 percent ofthe fugitives that have wound up therehave been captured.Karl Armstrong was the first onearrested; he’d been living under an aliasSUMMER 2005 31

in Toronto before he was caught in 1972.Another tip led to Fine, who was bustedin 1976 in San Rafael, California. A yearlater, Dwight Armstrong was captured inToronto. Dwight, Bates wrote, “was sotired of living underground that he hadin effect given up hiding.”It would seem nothing couldprepare someone for a life underground.Abbie Hoffman, a longtime fugitivefrom that era, wrote upon surfacing: “Afugitive’s brain is filled with a mass ofdata — Social Security numbers, jobhistories, birthdates, coded contacts,even different birth signs. <strong>The</strong>re are atleast two dozen names I used. If I examinedthe problem of who I was, somethingeveryone does in introspectiveperiods, the problem only gets magnified.A simple ‘’What’s your name?’ canproduce insane giggles.”It is the difficulty of life underground— the lies, the constant sense ofvulnerability, the complete cutting ofties to friends and family — that makessome people believe Leo Burt is not stillon the run.“I think he died, and nobody botheredto tell us,” Chuck Lulling, the leadMadison police detective on the case,once said.But there’s no proof of that, either.When he took over the investigation in1988, Miller sent copies of Burt’s fingerprintsto all the medical examiners inthe United States to compare with anyJohn Doe bodies.“That came back negative,” he says.Like Allan Thompson before him,Miller never did feel like the bureau wasclose to catching Burt, who would nowbe fifty-seven years old. Miller hadagents around the country take picturesof Burt’s living male relatives to createmodels of what Burt might look liketoday. He has also pitched the case totrue-crime television programs such asAmerica’s Most Wanted and Unsolved Mysteries.“I thought we were going to geton Unsolved Mysteries,” he says. “Butthen someone on the production teamOn the rowing team, Burt fit in with athletes like Tim Mickelson (left), who shared his workethic and competitive spirit. Mickelson recalls him as a serious student who never fought withanyone. But after Burt quit the crew, he drifted away from his former teammates and toward adifferent circle of friends.told me, ‘We really sympathize with thisguy. We were against the war, too.’ ”If he did survive, Burt’s life undergroundgot easier in 1976, when he wasremoved from the FBI’s most-wantedlist. Fine had been arrested andreturned to Madison to face charges,and a federal magistrate had grantedhim bail — unusual leniency for a manwho had spent six years running fromjustice. <strong>The</strong> FBI took that as a sign thatthe bombers were no longer regarded asserious threats and removed Burt fromits vaunted list.<strong>The</strong> practical effect for a fugitivewould have been huge. To be on that listis to have your picture everywhere.More than that, it means even distantrelatives have their phone recordschecked and their mail perused. Whenan agent is responsible for a suspect onthat list, Miller says, “every thirty daysyou have to submit a report to headquarterstelling them about all the finework you’re doing [and] all the hardinvestigating you’ve done and are planningto do in the next thirty days. It’s alot of work.”Burt wasn’t on the list when Millergot the case, which meant that the FBIchecked in with Burt’s brothers andfather (who is now deceased) from timeto time, but it didn’t maintain roundthe-clocksurveillance. “Every once in awhile, you might get a subpoena andpull some phone records to see if theyhad gotten a phone call from Ontario orsome place,” Miller says. “Of course, ifCOURTESY OF TIM MICKELSON32 ON WISCONSIN

FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATIONThree pictures capture how Burt might look now, when he would be fifty-seven years old. <strong>The</strong> FBI used pictures of Burt’s relatives and computertechnology to create the images, although agents admit the chances they will find Burt grow more remote every day.he’d been on the Ten Most Wanted list,we’d have been camped outside theirdoor.”But if the reduced attention makesit easier to stay in the shadows, it alsoreduces the risk of stepping out of them.After pleading guilty to a charge of second-degreemurder and receiving atwenty-three-year jail sentence, KarlArmstrong was paroled in 1980 andlives in Madison. Fine and DwightArmstrong each did short terms inprison and have returned to lives aboveground. Miller wonders why Burtwouldn’t have turned himself in,accepted a relatively light sentence, andbeen done with it.“That’s why, late on some nights,”Miller says, “I say, ‘Well, maybe he’s dead.’It’s either that, or he’s so comfortable as afugitive that he’s somewhere where he’sconvinced he’ll never be caught.”<strong>The</strong> truth is that we don’t know,and we may never find out. Firsthandknowledge of the case is fading. Batesdied of pancreatic cancer in 1999;Lulling passed away in 2000. BothMiller and Thompson have retired fromthe FBI.Tim Mickelson no longer gets callsfrom the FBI, which is just as well. Inthirty-five years, he has heard nothingfrom Leo Burt.But the theories live on. On theInternet, you can read countless farfetchednotions of what happened toBurt. One theory, largely discounted, isthat Burt was actually working undercoverfor the authorities against theanti-war movement.“He let his hair growand started writing a lotfor the Daily Cardinaland SDS,” Mickelsonrecalls. “At some point,he started believingwhat he was writing.”Brennan, who admits to havingsomething of an obsession with Burt,said recently that “everybody who knewhim has a theory of what has happenedto him.” Most everyone agrees that thestrength of will — the kind of mindover-bodystrength that earned an average-bodiedrower the attention of thenation’s elite crew programs — wouldhave served Burt well as he abandonedhis old life. “He’s cold as steel,” DwightArmstrong said, and that’s the kind ofresolve one would need.“I think he’s still alive,” Brennansays, “and I think he’s only caught if hewants to be caught.”In June 1999, police and FBI agentsacting on a tip surrounded a white minivanin the suburbs of St. Paul, Minnesota.<strong>The</strong> driver, a woman namedSara Jane Olson, was a mother of three,married to a doctor — except that sheturned out to be Kathleen Soliah, amember of the Symbionese LiberationArmy, a radical group perhaps bestknown for kidnapping Patty Hearst in1974. Soliah had been on the run fortwenty-five years.That leaves Burt, who vanished adecade ago longer than that, as the lastpiece of a puzzle that we can’t seem toput away. And we may never know thefull picture — because if he isn’t dead,he might as well be.“He won’t come forward,” Brennansays. “Remember this: whoever he hasbecome, he has been that person a lotlonger than he was Leo Burt.”Doug Moe ’79, former editor of Madison Magazineand now a columnist for the Capital Times, hasheard from dozens of people during his career whoclaim to know where Leo BurtSUMMER 2005 33