PT40 shopping for yiddish - Yiddish Book Center

PT40 shopping for yiddish - Yiddish Book Center

PT40 shopping for yiddish - Yiddish Book Center

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

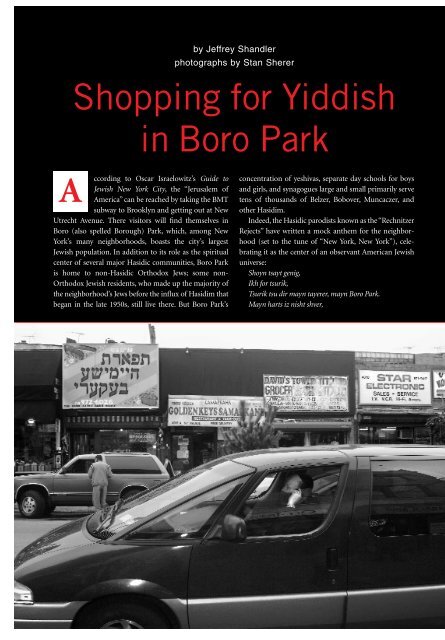

y Jeffrey Shandlerphotographs by Stan ShererShopping <strong>for</strong> <strong>Yiddish</strong>in Boro ParkAccording to Oscar Israelowitz’s Guide toJewish New York City, the “Jerusalem ofAmerica” can be reached by taking the BMTsubway to Brooklyn and getting out at NewUtrecht Avenue. There visitors will find themselves inBoro (also spelled Borough) Park, which, among NewYork’s many neighborhoods, boasts the city’s largestJewish population. In addition to its role as the spiritualcenter of several major Hasidic communities, Boro Parkis home to non-Hasidic Orthodox Jews; some non-Orthodox Jewish residents, who made up the majority ofthe neighborhood’s Jews be<strong>for</strong>e the influx of Hasidim thatbegan in the late 1950s, still live there. But Boro Park’sconcentration of yeshivas, separate day schools <strong>for</strong> boysand girls, and synagogues large and small primarily servetens of thousands of Belzer, Bobover, Muncaczer, andother Hasidim.Indeed, the Hasidic parodists known as the “RechnitzerRejects” have written a mock anthem <strong>for</strong> the neighborhood(set to the tune of “New York, New York”), celebratingit as the center of an observant American Jewishuniverse:Shoyn tsayt genig,Ikh <strong>for</strong> tsurik,Tsurik tsu dir mayn tayerer, mayn Boro Park.Mayn harts iz nisht shver,21 PAKN TREGER 21 PAKN TREGER

Ikh zorg zikh nit mer,Shoyn, shoyn, ikh <strong>for</strong> aheym tsu aykh, mayn Boro Park.Dort vu der shabes un der yontef iz nisht shvakh,Vu yidn lernen a blat, tog un nakht.[It’s high time now,I’m coming back,Back to you, dear Boro Park.My heart isn’t heavy,I no longer worry,I’m coming back to you, my Boro Park.There, where the Sabbath and holidays are strong,Where Jews study a page of the Talmud day and night.]Boro Park is a decidedly balebatish, or well-heeled, Hasidicneighborhood, with an elaborate and distinctive consumerculture. Eve Jochnowitz, who is a Ph.D. candidate at New YorkUniversity researching contemporary Jewish life in Brooklynand who conducts walking tours of Boro Park, notes that thedress and comportment of the local Hasidim are governed bya uniquely urban aesthetic that combines the laws of tsnies(modesty) with concern <strong>for</strong> balebatish respectability. “Youcould dress sloppily and still be sufficiently covered to be consideredtsniesdik,” she explains on a recent visit to the neighborhood,“but Hasidic dress in Boro Park also requires anattention to detail that shows respect <strong>for</strong> oneself and others.”mean not only buying books, periodicals, sound recordings,and videos in <strong>Yiddish</strong>, but also encountering <strong>Yiddish</strong> in thepublic sphere: on signs, posters, and advertisements, as well asthrough the spoken word. Here <strong>Yiddish</strong> is a language of themarketplace – albeit a very different one from those of JewishEastern Europe be<strong>for</strong>e World War II. In his 1979 study of theneighborhood, sociologist Egon Mayer cautioned visitors that,while “shtetl-like” in some respects, this part of Brooklyn is not“a re-created East European shtetl.” Those who visit Boro Parktoday will discover it is a twenty-first-century Americanneighborhood as much as it is a Hasidic one, as revealed by theuse of <strong>Yiddish</strong> they find here.Thirteenth Avenue: Boro Park’s Main StreetThough other Jewish <strong>shopping</strong> strips to the east and westmark the expansion of Orthodox settlement in the neighborhood,Thirteenth Avenue, from about 40th to 55th Streets,remains the commercial hub of Boro Park. In addition to groceries,butchers, bakeries, pharmacies, and other small shopsthat typically line commercial streets throughout Brooklyn arebusinesses catering to the particular needs of the haredi community:wig stores and hat stores, their wares enabling marriedwomen to observe rules of modesty in public appearance; shopsthat sell satin bekeshes (long robes) and shtraymlekh (furtrimmedhats), the holiday garb of Hasidic men. Some local dryIndeed, the wide array of goods and services available here testifiesto the considerable level of com<strong>for</strong>t Hasidim enjoy in thisBrooklyn neighborhood, as do its large new school and synagoguebuildings and the growing number of residential blocksoccupied exclusively by haredi (ultra-Orthodox) families. Hereis an extensive community that, within a half-century, has establisheditself both spiritually and materially in its new home.For scholars and enthusiasts of <strong>Yiddish</strong> culture, whatevertheir religious convictions, Boro Park holds a special attraction,as it is one of the best places to shop <strong>for</strong> <strong>Yiddish</strong>. By this Icleaners offer the services of a shatnez inspector, who will checkthe composition of clothes to make sure they do not contain amix of linen and woolen fibers, which is unacceptable accordingto rabbinic law. And there are signs advertising the services ofsofrim (scribes), who copy sacred texts onto pieces of parchmentthat are placed in mezuzes and tfiln, as well as penningtorah scrolls and megiles.<strong>Yiddish</strong> appears on signs above a number of Boro Parkstorefronts. Typically, these signs feature two or three languages;besides <strong>Yiddish</strong>, English, and Hebrew, some signage is22 FALL 2002

in Russian, <strong>for</strong> the benefit of recent immigrantsfrom the <strong>for</strong>mer Soviet Union. InBoro Park, <strong>Yiddish</strong> on a shop’s sign servesnot so much to identify what sort of businessis within as it does to indicate that thebusiness is, in local terminology, heymish –meaning, in this context, that it is not onlylocal and familiar but also appropriate tothe specific needs and sensibilities ofBrooklyn’s Hasidim. <strong>Yiddish</strong> is widelyemployed throughout Boro Park, in speechas well as print, to signify what is considered heymish. Evensome of the local ATMs offer the option of banking in<strong>Yiddish</strong>.As in haredi neighborhoods in Israel, posters play astrategic role in Boro Park, in<strong>for</strong>ming, exhorting, andenticing members of the community. They trans<strong>for</strong>m thestreet into a constantly updated bulletin board or want-adsection of a newspaper, announcing events, goods, and services.Posters change with the season: in the early fall, <strong>for</strong>example, they advertise temporary sites <strong>for</strong> per<strong>for</strong>ming theritual of shlogn kapores in the days be<strong>for</strong>e Yom Kippur. “Aleunzere tshikens hobn pampers” (“All our chickens havePampers”) one recent sign boasted, in a typical mix of<strong>Yiddish</strong> and English, thereby assuring shloggers that theBoro Park is adecidedly balebatish,or well-heeled,Hasidic neighborhood,with an elaborateand distinctiveconsumer culture.A landmark of Boro Park’s main commercialstreet is the newsstand on the cornerof Thirteenth Avenue and 49th Street, withits bilingual sign: “Newspapers/Tsaytungen.”Prominent among the newspapers andmagazines available here are Orthodoxand Hasidic publications: The Jewish Press,Jewish Action (a magazine published by theOrthodox Union), Hamachne Hachareidi(an English/Hebrew newspaper), Der algemeynerzhurnal (a <strong>Yiddish</strong> weekly publishedby Chabad), Di tsaytung, (“The <strong>Yiddish</strong> Paper of Record”).Also sold at this newsstand are the major Israeli dailies. Notavailable are the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, orthe Forward in any of its languages. But there is a sampling ofmainstream English-language magazines <strong>for</strong> sale, includingFortune, Newsweek, and Martha Stewart Living.The newsstand is just a few doors from Mostly Music (4815Thirteenth Avenue), one of several stores that cater to the community’saudio-visual interests. This small shop offers anextensive and wide-ranging selection of sound recordings,including vintage <strong>Yiddish</strong> vocals by the likes of Molly Piconand Pesach’ke Burstein, classic cantorial per<strong>for</strong>mances, as wellas the latest klezmer and avant-garde Jewish recordings, Israeliartists, and contemporary American spiritual recordings fromkapore-hindl (sacrificial fowl) will not soil them during theritual of atonement; this involves raising a hen or roosterabove one’s head while reciting a prayer that symbolicallytransfers one’s sins <strong>for</strong> the past year to the bird, which is thenslaughtered. Soon thereafter, signs appear announcing placesto buy skhakh, lulavim, and esrogim <strong>for</strong> the holiday of Succos.The end of winter brings news of upcoming purim-shpiln(Purim plays), followed soon thereafter by posters <strong>for</strong> sales ofPassover foods and special amusements <strong>for</strong> the period ofkholhamoyed peysekh, during which schools are closed.Debbie Friedman and New York congregation B’nai Jeshurun.There is also a less extensive selection of videotapes <strong>for</strong> sale,with some classic <strong>Yiddish</strong> films among the children’s videos(lots of Uncle Moishy, Torah Tots), Hasidic musicians in concert,Israel travelogues, and the occasional Orthodox exercisevideo featuring modestly clad instructors. But Mostly Musicdevotes pride of place to recordings by Mordecai Ben David(locally known simply as MBD), Shlomo Carlebach, AvrahamFried, the Miami Boys Choir, and other mainstays of Brooklyn’sOrthodox popular music scene. Many of the vocal recordings23 PAKN TREGER

feature selections in <strong>Yiddish</strong> as well as English and Hebrew.<strong>Yiddish</strong> names are also given to some contemporary instrumentalpieces, an indication that this music is heymish – as arelabels warning listeners not to play recordings on the Sabbath andJewish holidays, and that duplication of the recording is “againsthalacha”as well as a violation of copyright law.<strong>Yiddish</strong> Titles <strong>for</strong> the Haredi ReaderTwo blocks from Mostly Music is another important destination<strong>for</strong> the <strong>Yiddish</strong> consumer: Eichler’s bookstore (5004Thirteenth Avenue). Claiming to be “The Largest JudaicaStore in the World,” Eichler’s is certainly the largest of theneighborhood’s several Jewish bookstores (and there appearsto be no other kind of bookstore inthe area). A visit to Eichler’s providesan overview of Jewish literacyas it is understood in Boro Park.The store’s vast inventory has littlein common with the Judaica sectionof a Barnes & Noble or other mainstreambookstore or, <strong>for</strong> that matter,with many an American synagoguelibrary. You will not find the novelsof Cynthia Ozick or Philip Roth atEichler’s, nor the philosophical writingsof Heschel or Levinas; likewise,there are no works of modern secular <strong>Yiddish</strong> or Hebrewauthors (in original or translation). The store’s most extensiveofferings are s<strong>for</strong>im, including handsomely bound sets of theTalmud and makhzorim. Secular books include kosher cookbooksas well as a few familiar titles dealing with theHolocaust or Israel. Biographies, though, appear to deal exclusivelywith the lives of Hasidic and rabbinic sages.Like other Judaica bookstores (not to mention the itinerantmoykher-s<strong>for</strong>im of bygone days), Eichler’s also offersother goods, ranging from ritual objects and clothing torecordings and children’s games. The ritual items in Eichler’stestify to the elaborate haredi domestic culture that hasevolved in Boro Park. The store boasts a wide selection o<strong>for</strong>nately decorated boxes <strong>for</strong> storing bentsherlekh (smallbooklets with the text <strong>for</strong> grace after meals) at the dinnertable, all manner of ewers and basins <strong>for</strong> ritual handwashing,and kiddush fountains, which allow one to bless onelarge goblet of wine and then pour it simultaneously intoeight or more small cups <strong>for</strong> family and guests (morehygienic, if less traditional, than passing one wine gobletfrom person to person around the table, notes Jochnowitz).Though these ritual items are much more likely to bearHebrew inscriptions, some are labeled in <strong>Yiddish</strong>.For the <strong>Yiddish</strong> reader, Eichler’s offers titles that testify tothe language’s role in maintaining traditional cultural literacyamong haredim. One can find <strong>Yiddish</strong> anthologies of Biblecommentaries, selections from the Shulhan Arukh, andinstructional volumes on Jewish holidays and sages of the past.Some works maintain the long standing association of <strong>Yiddish</strong>with the pious female reader. For example, Der kroyn fun tsnies(The Crown of Modesty, published in Brooklyn in 2000), a guideto conduct <strong>for</strong> the modern Hasidic woman, explains the moresof proper dress and restrictions on activities ranging fromriding a bicycle to talking on a cell phone in public.A very recent development – apparently only within thelast few years – is a spate of entertainment literature writtenin <strong>Yiddish</strong> that meets the haredi community’s exactingconcerns. Some of these worksare suspense novels – such asDer shpion vos iz antlofn (The SpyWho Escaped) by F. Royz, publishedin Monroe, New York,in 2000; the book’s title pagedescribes it as “a suspenseful story,with many stormy moments anddramatic descriptions, with livelyscenes of a Russian spy underCommunist rule.” Other titles fallinto the category of historical fiction,such as Antdekt Amerike(America Discovered) by Y. Sh. Gros,“a suspenseful, dramatic,and instructive story that takes place during the time of thesearch <strong>for</strong> America by the explorer ‘Columbus the Jew,’” publishedin Kiryas Joel, New York, in 1997. Typically, these booksopen with haskomes, letters of endorsement from rabbinicauthorities; some include prefaces from the publisher offeringa rationale <strong>for</strong> this new literary genre. The introduction to Dershpion vos iz antlofn explains that “dramatic books” such asthis are a product of modern times, and that reading fictionhas become an important part of life not only <strong>for</strong> gentiles, but<strong>for</strong> Jews as well. It goes on to describe how these Jews – assimilationistsand followers of the Jewish Enlightenment – turnedat first to books in other languages, but then began readingsecular books in <strong>Yiddish</strong>. Such works by “<strong>Yiddish</strong>ists,” withtheir “false knowledge,” created upheaval among traditionallyobservant Jews, we are told. And now there are similar booksin modern Hebrew and English to contend with as well. Toalleviate this problem, rabbis have turned to “trustworthyauthors” to write works of fiction in <strong>Yiddish</strong> that are “worthyof being brought into respectable Jewish homes.”To the scholar of <strong>Yiddish</strong> literature, this argument soundsstrangely familiar. Centuries ago, similar prefaces appeared insome of the first published <strong>Yiddish</strong> books, such as vernaculartranslations of the Bible and compendia of morally instruc-24 FALL 2002

tive tales and fables, which strove to locatea place <strong>for</strong> this innovative literature in theJewish world. These books occupied anew middle ground in what the linguistMax Weinreich described as the “levelsof holiness” that codify traditionalAshkenazic culture. As works of vernacularculture, <strong>Yiddish</strong> books were lower instatus than canonical s<strong>for</strong>im written inloshn-koydesh, yet they ranked abovebooks by gentiles written in German and other Christian vernaculars.Pious <strong>Yiddish</strong> books, then as well as now, offer theJewish reader texts whose contents are culturally familiar andmorally appropriate within the appealing <strong>for</strong>m of popularentertainment genres.Another contemporary rendering of the traditional use of<strong>Yiddish</strong> to create works that entertain as well as edify is foundon the shelves in Eichler’s media section, which sells bothaudio and audio-visual recordings of recent per<strong>for</strong>mances inHasidim value <strong>Yiddish</strong>as a traditional vehicleof Hasidic lore and<strong>for</strong> its new role ofdistinguishing Hasidimfrom other Jews.keeping with Hasidic notions of femalemodesty in public, and includes dramatizationsof episodes from Jewish history inwhich Jews triumphed over persecutionby anti-Semites, as well as Mekires Yoysef,the classic purim-shpil recounting the biblicalstory of the selling of Joseph intoslavery by his brothers and ending withtheir reunion in Egypt.The beginning <strong>Yiddish</strong> reader of any agewill find plenty of <strong>Yiddish</strong> titles among Eichler’s sizableinventory of children’s books. Most are designed to introduceyoung readers to the mores of a traditionally pious life,describing daily routines or holiday observance; other children’sbooks relate stories of Hasidic sages of the past. Thereare a few <strong>Yiddish</strong> titles that deal with the secular world,notably a multivolume Entsiklopedye far yugnt (Encyclopedia<strong>for</strong> Young People), printed in Israel in 1999. Especially interestingare the readers and workbooks <strong>for</strong> the young student<strong>Yiddish</strong> “durkh heymishe yingelayt,” “by our own youngpeople.” These purim-shpiln and other plays are per<strong>for</strong>med toamuse the rebbe (and, secondarily, his community of followers)on special occasions during the year when such activitiesare permitted. The repertoire features all-male casts, inof <strong>Yiddish</strong>, most published by Hasidic girls’ schools, such asthe Satmar community’s Beys Rokhl schools. The incorporationof <strong>Yiddish</strong> into American Hasidic school curricula,which began about a generation ago, is a telling sign of whatsociolinguist Miriam Isaacs sees as a shift in the character of26 FALL 2002

<strong>Yiddish</strong> among postwar Hasidim from an “immigrantlanguage” to a “minority language.” Today, <strong>Yiddish</strong> primers,activity books, and even stickers (teachers can rewardstudents with a colorful “Zeyer gut!” or “Gevaldig!” or“Geshmak!”) both teach the language to haredi children andimbue it with meaning as a signifier of piety in daily life.Eichler’s also sells a variety of games and puzzles thatincorporate <strong>Yiddish</strong> into children’s play activities. Among themore elaborate games is Handl erlikh (“Deal honestly”),a knock-off of Monopoly that replaces the streets of AtlanticCity with place names of importance to the Hasidic world,past (Cracow and Lublin) and present (London, Montreal,and, of course, Boro Park). As players work their way aroundthe board, buying and renting properties, they are taughtlessons in piety as well as proper social and business conduct.The game’s instruction booklet explains in <strong>Yiddish</strong> thatHandl erlikh will “implant in children good character andreverence <strong>for</strong> God. Whoever deals honestly will have muchsuccess.” Players must tithe all their income, and khezhbnhanefesh(personal reckoning) cards penalize players <strong>for</strong> disobeyingone’s parents, <strong>for</strong>getting to recite a brokhe, watchingtelevision – or <strong>for</strong> speaking either English or modern Hebrew.The Meaning of <strong>Yiddish</strong> in Boro ParkThis implicit endorsement of <strong>Yiddish</strong> as the Hasidic vernacularof choice should not be mistaken <strong>for</strong> <strong>Yiddish</strong>ism,which the haredi community typically regards with greatsuspicion. In fact, a recent letter to the editor in Mayles, amonthly <strong>Yiddish</strong> magazine <strong>for</strong> Hasidic families publishedin Monsey, New York, criticizes the journal <strong>for</strong> what thereader considers a tendency toward <strong>Yiddish</strong>ism, evinced byits ef<strong>for</strong>ts to explain <strong>Yiddish</strong> grammar and provide glossariesof <strong>Yiddish</strong> terminology. (“Who says that there has tobe a <strong>Yiddish</strong> word <strong>for</strong> everything?” asks the letter’s author.“Not all languages are equally rich.”) Indeed, Hasidim whospeak <strong>Yiddish</strong> do not celebrate the language as the fountainheadof a wide-ranging, thousand-year-old Ashkenazicheritage that embraces labor movements and avant-gardepoetry as well as Hasidism, and they are suspicious ofef<strong>for</strong>ts to cultivate <strong>Yiddish</strong> <strong>for</strong> its own sake. Instead, theyvalue <strong>Yiddish</strong> both as a traditional vehicle of Hasidic loreand <strong>for</strong> its new role – one that has emerged in the post-Holocaust era – of distinguishing Hasidim from other Jews.Not surprising, then, that the non-Hasid who goes to BoroPark hoping to try out his or her <strong>Yiddish</strong> on the locals mayfind such ef<strong>for</strong>ts frustrated. Some Hasidim will refuse torespond to an outsider’s <strong>Yiddish</strong> in the language but willanswer in English instead. Literary scholar Richard Fein wroteof his largely unsuccessful ef<strong>for</strong>ts to engage LubavitcherHasidim in <strong>Yiddish</strong>, when he visited the community in CrownHeights, another Brooklyn neighborhood, in the late 1970s:Only later did I realize that the members of the familydid not speak to me in <strong>Yiddish</strong> because Hasidim don’twant to advance the presence of a secular Jew whospeaks <strong>Yiddish</strong>....<strong>Yiddish</strong>, <strong>for</strong> the Hasidic family, is thedaily part and parcel of a religious way of life. It is not alanguage that one cultivates <strong>for</strong> personal or intellectualor cultural reasons, as they correctly saw me doing.<strong>Yiddish</strong> was certainly not simply a language like anyother that one might help someone else to learn. While<strong>Yiddish</strong> was basic to me, they saw it as merely incidentalin my life, merely “an interest.” <strong>Yiddish</strong> was basic tothem, but in a completely different way.Like Fein, many devotees of <strong>Yiddish</strong> have come to it as a“discovery” (or, in Fein’s case, a rediscovery of a language hehad heard and even briefly studied as a child, as he explains inhis memoir, The Dance of Leah). They encounter <strong>Yiddish</strong> inclassrooms, festivals, and other venues where lovers of the languageconvene – places removed from their daily routines, inwhich they generally use other languages. For Fein and manyother <strong>Yiddish</strong>ists, the appeal of seeing <strong>Yiddish</strong> in situ, materializedin an environment in which the language is indigenous– the desire to pay a visit to <strong>Yiddish</strong>land – cannot be underestimated.Boro Park isn’t <strong>Yiddish</strong>land; indeed, some <strong>Yiddish</strong>istsdeplore the state of <strong>Yiddish</strong> among contemporary Hasidim,complaining that it isn’t regarded as a full or “pure” languageand that Hasidim regularly flout linguistic standards, or eventhe idea of standards. Nevertheless, the neighborhood offersan encounter with <strong>Yiddish</strong> that other settings cannot provide.Whatever their religious convictions, <strong>Yiddish</strong> enthusiastsshould not shrink from visiting Boro Park or other Hasidicneighborhoods in New York and elsewhere, but they shouldbear in mind that their attraction to places where <strong>Yiddish</strong>thrives in the marketplace does not con<strong>for</strong>m to the communities’own commitments, including their commitment to<strong>Yiddish</strong>. Such encounters can not only pose challenges; theycan enrich one’s awareness of cultural creativity among Jewstoday, and expand one’s concept of the possibilities of <strong>Yiddish</strong>in its second millennium. PTJeffrey Shandler is an assistant professor in the Department ofJewish Studies at Rutgers University. He is the author ofWhile America Watches: Televising the Holocaust (Ox<strong>for</strong>dUniversity Press, 1999) and the editor of Awakening Lives:Autobiographies of Jewish Youth in Poland be<strong>for</strong>e theHolocaust (Yale University Press, 2002). He is currentlyworking on a study of <strong>Yiddish</strong> culture after World War II.27 PAKN TREGER