人、天、魔——《女仙外史》中的歷史缺憾與 - 中國文哲研究所

人、天、魔——《女仙外史》中的歷史缺憾與 - 中國文哲研究所

人、天、魔——《女仙外史》中的歷史缺憾與 - 中國文哲研究所

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

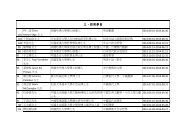

0 3 4394 人 、 天 、 魔——《 女 仙 外 史 》 中 的 歷 史 缺 憾 與 「 她 」 界 想 像 一 、 前 言(399-403) 2009 219 9443 99 04-9-9-43-

(33/3?-4/?) (40) 99 -3 () 9 9-4 9 3 3-34 (I) (00-90) 003 -393 0-9 003 -44-

刹 00 -39 -45-

二 、 人 間 事( 一 ) 呂 熊 其 人 其 時 3 巵 呌 00 3 () -46-

10 11 (3-3) (3-) () (?-) (3-3) (-3) 12 13 9-99 9 339c-339c49 09-009 10 崐 99 9 11 009 4 b-a12 9 0-00 99 - 3 99 9 -013 2003 325-335-47-

14 15 () () (9) 16 17 18 19 (4-09) 20 Ellen Widmer, The Margins of Utopia: Shui-hu hou-chuan and the Literature ofMing Loyalism (Carmbridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1987) 13-49—— 19 1 2001 6 219-24814 00 4 0-33-4015 4 3-416 0417 00 -49-918 Wilt L. Idema, Wai-yee Li, and Ellen Widmer eds., Trauma and Transcendence in Early QingLiterature (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2006), pp. 42-43.19 25 18a20 -48-

(9-) 21 22 23 ( 二 )「 靖 難 」 書 寫 (4-4) 24? -40 [3] ?-40 [3] 021 稾 00 9 b 3922 23 9 00 9 -024 000 430-49-

25 26 27 (4) 28 29 44-0 [4] 25 晗 晗 9 3926 99 4 4 27 000 3b 3 Hok-lam Chan, “The Rise of Ming T’ai-tsu(1368-98): Facts and Fictions in Early Ming Official Historiography,” in China and the Mongols:History and Legend under the Yüan and Ming (Aldershot, Hampshire, Great Britain; Brookfield,Vt., USA: Ashgate, 1999), pp. 679-715. Hok-lam Chan, “Legitimating Usurpation: HistoricalRevisions under the Ming Youngle Emperor (r. 1402-1424),” in The Legitimation of New Orders:Case Studies in World History , ed. Philip Yuen-sang Leung (Hong Kong: Chinese UniversityPress, 2007), pp. 75-158.28 99 0 329 99 3-3-50-

?-34 [] (4-4) (44-3) (490-) (49-) (499-) 30 31 [] (3-3) 32 (94-) (0-90) 003 -3Peter Ditmanson, “Venerating the Martyrs of the1402 Usurpation: History and Memory in the Mid and Late Ming Dynasty (1368-1644),” T’oungPao 93.1 (2007): 110-158.30 94 331 9-3 9 b 332 ?- [3] (3-03) [] (-)-51-

(-90) (-4) (-3) 33 ( 三 )《 女 仙 外 史 》 中 的 靖 難 34 35 33 499 4 9 -034 99 43-994 99 35 9 43-52-

36 37 (3-3) 38 (49-) 39 (499-) 40 (-3) 吴 94 009 4-036 39 3 9037 0 0 鼂 38 9039 00 34440 94 3-4-53-

47 48 49 50 47 990 0a-b Chan, Hok-lam, “Liu Chi (1311–75) in the Ying-Lieh-Chuan: The Fictionalizationof a Scholar-hero,” The Journal of the Oriental Society of Australia 5:1-2 (Dec. 1967): 26-42. 00 33-3048 49 950 4-55-

51 52 5351 952 0053 0-09-56-

54三 、 天 、 仙 55 56 5754 0055 993 0- 99 9 0-00 9-956 57 -57-

58 59 60 61 62 58 59 99 360 99 3-3361 0999 -962 -58-

63 Wai-yee Li, Enchantment andDisenchantment : Love and Illusion in Chinese Literature (Princeton: Princeton University Press,1993) Martin W. Huang, Desire and Fictional Narrative in Late Imperial China (Cambridge,Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2001) 眞 眞 003 眞 004 眞 004 009009 63 999 303-3999 40--59-

64 65 64 65 -60-

66 67 66 1067 993 94 30-61-

68 経 鬪 來 69 70 71 旉 68 9 4 999 9- 3 999 -300 30-3004 3-33949-4069 a 9370 -371 0-62-

72 旉 旉 旉 旉 73 72 旉 旉 073 00-63-

74 却 7574 Patrick Hanan, The Invention of Li Yu (Cambridge,Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1988)009 9- 晩 9-375 9-30-64-

76 77 78 79 80 (40-) 81 (-90) (34-4) (4-0) (39-) (-93) 76 99 77 478 (II) (00-90)003 -79 80 381 3-4-65-

82 (0-933) 83 Ann Waltner 84 Waltner 85 82 999 4 039-04090 39-34900 3 93-9400 4 Ann Waltner, “T’an-Yang-Tzu and Wang Shih-Chen: Visionary and Bureaucrat in the Late Ming,” Late ImperialChina 8.1 (June 1987):105-13399 Catherine Despeux and Livia Kohn eds., Women inDaoism (Cambridge, Mass.: Three Pines Press, 2003). Suzanne E. Cahill, Divine Traces of theDaoist Sisterhood: Records of the Assembled Transcendents of the Fortified Walled City by DuGuangting (850-933) (Magdalena, NM : Three Pines Press, 2006).83 99 00 0-004009 Philip Clart, “Translator’s Introduction,” The Story of HanXiangzi: The Alchemical Adventures of a Daoist Immortal (Seattle: University of WashingtonPress, 2007), pp. XVI-XXXV84 Ann Waltner, “Telling the Story of Tanyangzi,” 3-4085 Ann Waltner, “The Grand Secretary’s Family: Three Generations of Women in the Family ofWang Hsi-chüeh,” 99 4--66-

86 (4-0) 87 (4-33) 88 89 86 携 牀 却 a-b4a 39-393987 90 4 0488 9 3 -3 4 499 3-389 -67-

90 91 92 90 003 3-34091 994 b3b 92 4a 39 (0-) 壻 00 3 -999 -9-68-

四 、 魔 、 女 93 94 95 96 97 93 994 995 96 99 997 99 99 3099 499 9-69-

98 99 (Manicheism) (Mani) 100 101 98 94-934 9 9a-99 3b- c100 (-?) (-3)994-99 9 00 33-499 4101 09-70-

102 103 (māra) 104 102 003 3 00 -4103 93 3-3104 9-71-

105 106 107 108 109 110105 3106 94107 30108 30109 9110 3-72-

121 122 123 121 94 a 9122 33123 99 0-75-

124 125 戡 124 44125 30-76-

126 (?-4) 127 128 129 126 127 3 -9 39-0 a-b 4-490128 129 4-77-

130 131 132 133 134 135 136 130 9-99131 9132 133 3134 0-03135 0 - 136 40-78-

(4-04) 139139 -80-

140 141 142 (9-9)140 0 9 0 141 Wai-yee Li, “Heroic Transformations: Women and National Trauma in Early Qing Literature,”Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 59.2 (Dec., 1999): 363-443.142 Ibid., p. 365.-81-

(09-)五 、 結 語-82-

143 144 143 (Andrew H. Plaks) (Anthony C. Yu) 00 3 00 3 -43144 (lyricism) 啓 33 00 9 9-83-

145 146 147 148 149 145 004 -9Judith Zeitlin, “The Return of the Palace Lady: The Historical Ghost Story and Dynastic Fall,” inDynastic Crisis and Cultural Innovation: From the Late Ming to the Late Qing and Beyond, ed.David Der-wei Wang and Shang Wei (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2005),pp.151-99. 3 00 9 3-146 (Avadâna) 0 4 999 3- 0 3 -147 2004 385-412Wai-yee Li, “Women as Emblems of Dynastic Fall in Qing Literature,” in Dynastic Crisis andCultural Innovation : From the Late Ming to the Late Qing and Beyond , pp. 93-150. 7 2 2010 12 289-344148 1980 2 61-62149 Enchantmentand Disenchantment: Love and Illusion in Chinese Literature -84-

150 150 1987 -85-

人 、 天 、 魔——《 女 仙 外 史 》 中 的 歷 史 缺 憾 與 「 她 」 界 想 像關 鍵 詞 :《 女 仙 外 史 》 呂 熊 唐 賽 兒 靖 難 他 界 魔-86-

Man, Heaven and Māra:Historical Loss and Fantastic Invention in The UnofficialHistory of Female ImmortalsLIU Chiung-yunThis paper examines how the historical and fantastic modes of writing interactin the late seventeenth century novel, The Unofficial History of Female Immortals,written by Lü Xiong, regarding the 1402 usurpation. I first provide a brief overviewof the author’s background, his possibly ambivalent feelings towards the fallen Mingdynasty and the consolidating Qing rule, and the Ming-Qing historians’ diverseopinions on the 1402 usurpation. I then demonstrate that by re-presenting Tang Saieras the reincarnation of the Goddess of Moon banished to the human world for herexcessive emotions (qing), the author establishes a celestial agent who shares andresponds to the human desire for justice. To counter historical reality, in which theprincipally virtuous Jianwen emperor and his male officials lost power to the militantand valiant Yongle, the author draws from the Chinese religious tradition to construct asect of female Māras, characterized by their extraordinary competence, fervent passionand lack of conventional female virtues. I argue that writing in the fantastic modeenables Lü to create an imagined alternative to heal the wounds in history. At the sametime, he is only too aware that the power he has projected onto the female immortalsand Māras is but a constructed fantasy.My reading of this novel is especially important in three aspects. First, theextent to which the author embeds his mixed sentiments in his historical-fantasticnarrative gives it an almost self-expressive, lyrical quality, which invites us toreevaluate the capacity of the so-called novels of gods and demons (shenmo xiaoshuo)of the Ming-Qing period. Secondly, it reminds us that in our discussion of theflexibility of female characters as metaphors of national trauma, Māra and Rākṣasīconstitute another noteworthy category. Finally, in terms of the development of Ming-Qing novels, the connection between the Dream of the Red Chamber and UnofficialHistory of Female Immortals, distinguished for its depiction of a realm of impassionedfemale immortals, may be deeper than it appears.Keywords: Nüxian waishi Lü Xiong Tang Saier 1402 usurpationthe fantastic Māra-87-

徵 引 書 目 90 0 9 0 -0099 4 4 9994 004 33 00 9 -3 90009 994 00399 3-399 99 99 9 003 004994-99 9 9 003 -3-88-

9 99 994 99 993 (I) (00-90) 003 3 999 -3 (Avadâna) 0 4 999 3-99 9 0099 00 00 9-344 4 993 99 9 0-00 99 999 003 00 -400 -89-

9 00 99 9 00 94-934009 99 999 93 3-3003 99 99 993 999 990 0 94-934 9 94-93499 004 00 9 9-99 00000 -400 9- 3 9 99 000 -90-

(II) (00-90) 003 94 9 99 999 3 00 9 3-009 00 94-934 99 004 9-4 9 9 00 9 -0990 99 -00 9 99 4009 94-934 9 94-934 94-934 003 004 004 -91-

90 0-93 0- 99 999 009 4 9 39-0 9 99 00 003 300 3 -43 99 9 00 94 9 009 3 99 9 -09 9 9 00 9-4009 00 9 99 00 -92-

009 0 3 -9 93 9-3 9 9 4 999 9-399 94 Chan, Hok-lam. “Liu Chi (1311–75) in the Ying-Lieh-Chuan: The Fictionalization of a Scholar-hero,”The Journal of the Oriental Society of Australia 5:1-2 (Dec. 1967): 26-42._____________. China and the Mongols: History and Legend under the Yüan and Ming. AldershotHampshire, Great Britain; Brookfield, Vt., USA: Ashgate, 1999._____________. “Legitimating Usurpation: Historical Revisions under the Ming Youngle Emperor (r.1402-1424).” In The Legitimation of New Orders: Case Studies in World History. Ed. PhilipYuen-sang Leung. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2007.Cahill, Suzanne E. Divine Traces of the Daoist Sisterhood: “Records of the Assembled Transcendentsof the Fortified Walled City” by Du Guangting (850-933). Magdalena, NM. : Three PinesPress, 2006.Clart, Philip. The Story of Han Xiangzi: The Alchemical Adventures of a Daoist Immortal. Seattle:University of Washington Press, 2007.Despeux, Catherine and Livia Kohn ed. Women in Daoism. Cambridge: Three Pines Press, 2003.Ditmanson, Peter. “Venerating the Martyrs of the 1402 Usurpation: History and Memory in the Midand Late Ming Dynasty.” T’oung Pao 93.1 (2007): 110-158.Hanan, Patrick. The Invention of Li Yu. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1988.Huang, Martin W. Desire and Fictional Narrative in Late Imperial China. Cambridge, Mass.:Harvard University Press, 2001.Idema, Wilt L., Wai-yee Li, and Ellen Widmer ed. Trauma and Transcendence in Early QingLiterature. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2006.Li, Wai-yee. Enchantment and Disenchantment: Love and Illusion in Chinese Literature. Princeton:Princeton University Press, 1993.____________. “Heroic Transformations: Women and National Trauma in Early Qing Literature.”Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 59.2 (Dec. 1999): 363-443.____________. “Women as Emblems of Dynastic Fall in Qing Literature.” In Dynastic Crisis and-93-

Cultural Innovation : From the Late Ming to the Late Qing and Beyond. Ed. David Der-weiWang and Wei Shang. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2005.Waltner, Ann. “T’an-Yang-Tzu and Wang Shih-Chen: Visionary and Bureaucrat in the Late Ming,”Late Imperial China 8.1(Jun. 1987):105-133.___________. “The Grand Secretary’s Family: Three Generations of Women in the Family of WangHsi-chüeh.” 99___________.“Telling the Story of Tanyangzi.” 003Widmer, Ellen. The Margins of Utopia: Shui-hu hou-chuan and the Literature of Ming Loyalism.Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1987.Zeitlin, Judith. “The Return of the Palace Lady: The Historical Ghost Story and Dynastic Fall.” InDynastic Crisis and Cultural Innovation :From the Late Ming to the Late Qing and Beyond.Ed. David Der-wei Wang and Wei Shang. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University AsiaCenter, 2005.-94-