Education Resource - Drama Improves Lisbon Key Competences in ...

Education Resource - Drama Improves Lisbon Key Competences in ...

Education Resource - Drama Improves Lisbon Key Competences in ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

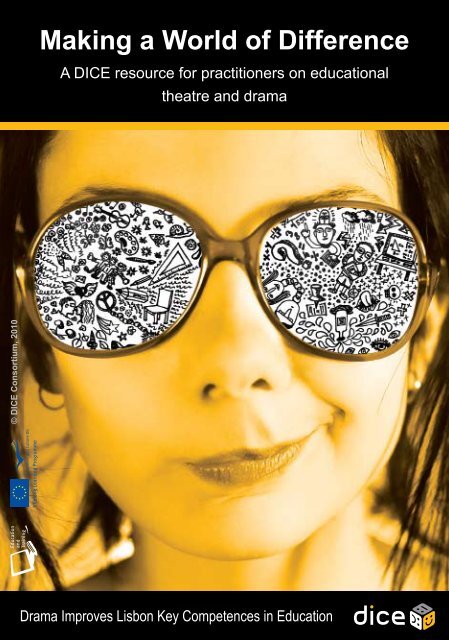

Mak<strong>in</strong>g a World of differenceA DICE resource for practitioners on educationaltheatre and dramaDICE – <strong>Drama</strong> <strong>Improves</strong> <strong>Lisbon</strong> <strong>Key</strong> <strong>Competences</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong>© DICE Consortium, 2010Belgrade Bergen Birm<strong>in</strong>gham Brussels Bucharest Budapest Gaza Gdansk<strong>Lisbon</strong> Ljubljana Prague Umea Wagen<strong>in</strong>gen

Credits & copyrightMembers of the DICE ConsortiumConsortium leader:• Hungary: Káva <strong>Drama</strong>/Theatre <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Association (Káva Kulturális Műhely) (Personnel <strong>in</strong> DICEproject: Cziboly Ádám, Danis Ildikó, Németh Szilvia, Szabó Vera, Titkos Rita, Varga Attila)Consortium members:• Netherlands: Sticht<strong>in</strong>g Leesmij (Personnel <strong>in</strong> DICE project: Jessica Harmsen, Suzanne Prak, SietseSterrenburg)• Poland: University of Gdansk (Uniwersytet Gdanski) (Personnel <strong>in</strong> DICE project: Adam Jagiello-Rusilowski,Lucyna Kopciewicz, Karol<strong>in</strong>a Rzepecka)• Romania: Sigma Art Foundation (Fundatia Culturala Pentru T<strong>in</strong>eret Sigma Art) (Personnel <strong>in</strong> DICE project:Cristian Dumitrescu, Livia Mohîrtă, Ir<strong>in</strong>a Piloş)• Slovenia: Taka Tuka Club (Durštvo ustvarjalcev Taka Tuka) (Personnel <strong>in</strong> DICE project: Veronika GaberKorbar, Katar<strong>in</strong>a Picelj)• United K<strong>in</strong>gdom: Big Brum Theatre <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Co. Ltd. (Personnel <strong>in</strong> DICE project: Dan Brown, ChrisCooper, Jane Woddis)Associate partners:• Czech Republic: Charles University, Prague (Personnel <strong>in</strong> DICE project: Jana Draberova, Klara Seznam) • Norway: Bergen University College (Høgskolen i Bergen) (Personnel <strong>in</strong> DICE project: Stig A. Eriksson,Katr<strong>in</strong>e Heggstad, Kari Mjaaland Heggstad)• Palest<strong>in</strong>e: Theatre Day Productions (Personnel <strong>in</strong> DICE project: Amer Khalil, Jackie Lubeck, Jan Willems,D<strong>in</strong>a Zbidat)• Portugal: Technical University of <strong>Lisbon</strong> (Universidade Técnica de Lisboa) (Personnel <strong>in</strong> DICE project:Margarida Gaspar de Matos, Mafalda Ferreira, Tania Gaspar, G<strong>in</strong>a Tome, Marta Reis, Ines Camacho)• Serbia: Center for <strong>Drama</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> and Art CEDEUM (CEDEUM Centar za dramu u edukaciji iumetnosti) (Personnel <strong>in</strong> DICE project: Ljubica Beljanski-Ristić, Sanja Krsmanović-Tasić, Andjelija Jočić)• Sweden: Culture Centre for Children and Youth <strong>in</strong> Umea (Kulturcentrum för barn och unga) (Personnel <strong>in</strong>DICE project: Helge von Bahr, Eleonor Fernerud, Anna-Kar<strong>in</strong> Kask)CopyrightThis document holds an “Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0” International Creative Commons licence.Summary of the licence:• You are free: to Share — to copy, distribute and transmit the document under the follow<strong>in</strong>g conditions:• Attribution — You must always attribute the work to the DICE Consortium and <strong>in</strong>dicate the www.dramanetwork.eu webpage as the source of the document• Noncommercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes.• No Derivative Works — You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.• Any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder.• For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work with a l<strong>in</strong>k to theCreative Commons web page below.• Further details and full legal text available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/142455-LLP-1-2008-1-HU-COMENIUS-CMP"This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the viewsonly of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the<strong>in</strong>formation conta<strong>in</strong>ed there<strong>in</strong>."ContentsCredits & copyright 2Contents 3Preface 8Readers Guide 9A. Introduction 10The DICE Project – What is DICE? The project outl<strong>in</strong>ed 10The DICE Project – consortium members and partner organisations 12<strong>Education</strong>al Theatre and <strong>Drama</strong> – What is it? 17The DICE Project – Our ethos 20Research F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs – A summary of key f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs 24B. How educational theatre and drama improves key competences 26A brief <strong>in</strong>troduction to the documented practices 26Learn<strong>in</strong>g to learn 291. Suitcase – drama workshop, Big Brum Theatre <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Company 29a. Workshop Summary 29b. Practitioners 30c. Target Audience/participants 30d. Duration 30e. What we were explor<strong>in</strong>g (objectives/learn<strong>in</strong>g areas) 30f. What we did and how we did it (structure of the project/workshop) 31g. Source Material 41h. Equipment 41i. Our approach (some of the th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g guid<strong>in</strong>g our practice) 41j. Further read<strong>in</strong>g 45k. Teachers: A guide to practice 452. Obstacle Race – theatre <strong>in</strong> education programme,Kava <strong>Drama</strong>/Theatre <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Association, Hungary. 48a. Programme summary 48b. Practitioners 49c. Target audience /participants 49d. Duration 49e. What we were explor<strong>in</strong>g (objectives/learn<strong>in</strong>g areas) 50f. What we did and how we did it (structure of the project/workshop) 51g. Source material 58h. Equipment 58i. Our approach (some of the th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g guid<strong>in</strong>g our practice) 59j. Further read<strong>in</strong>g 59k. Teachers: A guide to practice 60Introduction2 3

Cultural expression 613. The Human Hand - drama workshop,Bergen University College, Norway 61a. Workshop Summary 61b. Practitioners 61c. Target Audience/participants 62d. Duration 62e. What we were explor<strong>in</strong>g (objectives/learn<strong>in</strong>g areas) 63f. What we did and how we did it (structure of the project/workshop) 63g. Source Material 70h. Equipment 70i. Our approach (some of the th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g guid<strong>in</strong>g our practice) 71j. Further Read<strong>in</strong>g 71k. Teachers: A guide to practice 724. Kids for Kids - The Magic Grater,Theatre Day Productions, Gaza, Palest<strong>in</strong>e 73a. Project Summary 73b. Practitioners 74c. Target Audience/participants 74d. Duration 75e. What we were explor<strong>in</strong>g (objectives/learn<strong>in</strong>g areas) 76f. What we did and how we did it (structure of the project/workshop) 76g. Source Material 82h. Equipment 82i. Our approach (some of the th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g guid<strong>in</strong>g our practice) 82k. Teachers: A guide to practice 85Communication <strong>in</strong> the mother tongue 835. Towards the Possible,Centre for <strong>Drama</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> and Art CEDEUM, Serbia 87a. Workshop Summary 87b. Practitioners 88c. Target Audience/participants 88d. Duration 89e. What we were explor<strong>in</strong>g (objectives/learn<strong>in</strong>g areas) 89f. What we did and how we did it (structure of the project/workshop) 90g. Source Material 93h. Equipment 93i. Our approach (some of the th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g guid<strong>in</strong>g our practice) 94j. Further read<strong>in</strong>g 96k. Teachers: A guide to practice 966. Seek<strong>in</strong>g Survival – drama workshop, Eventus TIE, Norway. 100a. Workshop Summary 101b. Practitioners 101c. Target audience/participants 101d. Duration 101e. What we were explor<strong>in</strong>g (objectives/learn<strong>in</strong>g areas) 102f. What we did and how we did it (structure of the project/workshop) 103g. Source material 107h. Equipment 110i. Our approach (some of the th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g guid<strong>in</strong>g our practice) 110j. Further Read<strong>in</strong>g 112k. Teachers: A guide to practice 112Entrepreneurship 1147. A bunch mean<strong>in</strong>g bus<strong>in</strong>ess: an Entrepreneurial <strong>Education</strong>programme, University of Gdansk and POMOST, Poland 114a. Project Summary 114b. Practitioners 115c. Target Audience/participants 115d. Duration 115e. What we were explor<strong>in</strong>g (objectives/learn<strong>in</strong>g areas) 115f. What we did and how we did it (structure of the project/workshop) 116g. Source Material 120h. Equipment 120i. Our approach (some of the th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g guid<strong>in</strong>g our practice) 120j. Further read<strong>in</strong>g 1218. Early Sorrows – drama workshop, CEDEUM, Serbia 122a. Workshop Summary 122b. Practitioners 122c. Target Audience/participants 123d. Duration 123e. What we were explor<strong>in</strong>g (objectives/learn<strong>in</strong>g areas) 123f. What we did and how we did it (structure of the project/workshop) 124g. Source Material 129h. Equipment 129i. Our approach (some of the th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g guid<strong>in</strong>g our practice) 130j. Further read<strong>in</strong>g 130k. Teachers: A guide to practice 131Interpersonal, <strong>in</strong>tercultural and social competences, and civic competence 1349. The Stolen Exam – Leesmij, Netherlands 134a. Workshop Summary 134b. Practitioners 134c. Target Audience/participants 134d. Duration 135e. What we were explor<strong>in</strong>g (objectives/learn<strong>in</strong>g areas) 135f. What we did and how we did it (structure of the project/workshop) 135h. Equipment 138i. Our approach (some of the th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g guid<strong>in</strong>g our practice) 138Introduction4 5

j. Further Read<strong>in</strong>g 140k. Teachers: A guide to practice 14010. The Teacher – Theatre <strong>in</strong> education programme,Sigma Art, Romania 140a. Project summary 140b. Practitioners (who and how many practitioners createdand delivered the project) 141c. Audience/participants 141d. Duration 141e. What we were explor<strong>in</strong>g (objectives/Learn<strong>in</strong>g areas) 141f. What we did and how we did it (structure of the programme) 142g. Source material 146h. Equipment 146i. Our approach (some of the th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g guid<strong>in</strong>g our practice) 146j. Further read<strong>in</strong>g 147k. Teachers: A guide to practice 148C. Another throw of the DICE – What you can do 194Teachers 195Head teachers 195Theatre artists 196Students 197University lecturers <strong>in</strong> dramatic arts or teacher-tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g 198Policy-makers 199D. Appendices 200Appendix A. Term<strong>in</strong>ology 200Appendix B. F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g out more - where to f<strong>in</strong>d more <strong>in</strong>formation 206Appendix C. Contact<strong>in</strong>g consortium members 216IntroductionAll this and more.…. 15011. A W<strong>in</strong>dow - theatre <strong>in</strong> education programme,Big Brum Theatre <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> (TIE) Company, UK 150a. Project Summary 151b. Practitioners 151c. Target Audience/participants 151d. Duration 151e. What we were explor<strong>in</strong>g (objectives/learn<strong>in</strong>g areas) 152f. What we did and how we did it (structure of the project/workshop) 161g. Source Material 161h. Equipment 161i. Our approach (some of the th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g guid<strong>in</strong>g our practice) 161j. Further read<strong>in</strong>g 165k. Teachers: A guide to practice 16512. Puppets – a theatre <strong>in</strong> education programme,Káva <strong>Drama</strong>/Theatre <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Association, Hungary 169a. Programme summary 169b. Practitioners 170c. Target audience/participants 170d. Duration 170e. What we were explor<strong>in</strong>g (objectives / learn<strong>in</strong>g areas) 170f. What we did and how we did it (structure of the project) 171g. Source material 187h. Equipment 187i. Our approach (some of the th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g guid<strong>in</strong>g our practice) 190j. Further Read<strong>in</strong>g 190k. Teachers: a guide to practice 1906 7

PrefaceDear ReaderWelcome to the DICE <strong>Education</strong>al <strong>Resource</strong>. The DICE project has brought togetherpractitioners from 12 countries work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> educational theatre and drama (ETD). Thepurpose of our research has been to see how ETD impacts on 5 of the 8 <strong>Lisbon</strong> <strong>Key</strong><strong>Competences</strong> for lifelong learn<strong>in</strong>g. These are:• Communication <strong>in</strong> the mother tongue• Learn<strong>in</strong>g to learn• Interpersonal, <strong>in</strong>tercultural and social competences, and civic competence• Entrepreneurship• Cultural expressionWe view each competence as part of an <strong>in</strong>tegrated whole and value each one as anecessary part of a child’s development. We have also added a 6 th competence to ourresearch project:• All this and more.….This competence <strong>in</strong>corporates the other 5 but adds a new dimension to them becauseit is concerned with the universal competence of what it is to be human. An <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gconcern about the coherence of our society and develop<strong>in</strong>g democratic citizenshiprequires a moral compass by which to locate our selves and each other <strong>in</strong> the world andto beg<strong>in</strong> to re-evaluate and create new values; to imag<strong>in</strong>e, envisage, a society worthliv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>, and liv<strong>in</strong>g with a better sense of where we are go<strong>in</strong>g with deep convictions aboutwhat k<strong>in</strong>d of people we want to be. <strong>Education</strong>al theatre and drama is a social act ofmean<strong>in</strong>g-mak<strong>in</strong>g and it has the capacity to ignite the collective imag<strong>in</strong>ation to do this.The contents of these pages represent our struggle to open doors for young people tosee themselves and their world. The ethos underp<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g the DICE project (see The DICEProject – Our ethos) has been developed by the practice of the research project itself. Itreflects our own learn<strong>in</strong>g, the spirit of our collaboration and the ongo<strong>in</strong>g practice.The aim of this <strong>Education</strong>al <strong>Resource</strong> is to share what we have learned along the waywith fellow practitioners and those who are new to this field of work <strong>in</strong> the hope that it willencourage them to explore for themselves what we believe to be important work. You,dear reader, can respond to what we offer, add to and develop it, and hopefully jo<strong>in</strong> us onour journey.Reader’s GuideMak<strong>in</strong>g a World of Difference is an <strong>Education</strong>al <strong>Resource</strong> divided <strong>in</strong>to four sections.Section A is an <strong>in</strong>troduction to the DICE project: what the project was and set out toachieve, the partners, our ethos, the form of educational theatre and drama, and keyresearch f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs.Section B is broken down <strong>in</strong>to the six competences. The impact of educational theatreand drama activities on each competence is illustrated by documented practice, two percompetence. Each documented practice is broken down <strong>in</strong>to three sections:1 – the project/workshop/production – what we were do<strong>in</strong>g and how we did it.2 – our approach – an <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to some of the th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g guid<strong>in</strong>g our practice.3 – teachers: a guide to practice – recommendations, issues and questionsto consider if you were to take on the development of this work.The f<strong>in</strong>al part of each competence <strong>in</strong> Section B <strong>in</strong>cludes a short summary of the mostrelevant results related to each of the key competences.We view each competence as part of an <strong>in</strong>tegrated whole and value each one as anecessary part of a child’s development. There is no ascend<strong>in</strong>g order or primacy amongthem. In the spirit of this, rather than present the documented practice <strong>in</strong> numerical order,we rolled a dice to determ<strong>in</strong>e the order <strong>in</strong> which to share them with the reader. You, ofcourse, can choose your own order to read them <strong>in</strong>.Section C - Another throw of the DICE, focuseson what you can do to develop the use ofeducational theatre and drama <strong>in</strong> your owncontext and how to f<strong>in</strong>d out more about it.Section D has three very useful appendiceson term<strong>in</strong>ology, where to f<strong>in</strong>d more <strong>in</strong>formationand how to contact DICE partners.IntroductionChris CooperEditor8 9

RelevanceThe objectives of the project were:• To demonstrate with cross-cultural quantitative and qualitative research thateducational theatre and drama is a powerful tool to improve the <strong>Key</strong> <strong>Competences</strong>.The research was conducted with almost five thousand young people aged 13-16years.• To publish a Policy Paper, based on the research, and dissem<strong>in</strong>ate it amongeducational and cultural stakeholders at the European, national, and local levelsworldwide.• To create an <strong>Education</strong> <strong>Resource</strong> (the book you are read<strong>in</strong>g) - a publicationfor schools, educators and artistic practitioners about the different practices ofeducational theatre and drama. To dissem<strong>in</strong>ate this pack at the European, national,and local levels worldwide.• To compare theatre and drama activities <strong>in</strong> education <strong>in</strong> different countries and helpthe transfer of know-how with the mobility of experts.• To hold conferences <strong>in</strong> most of the partner countries <strong>in</strong> order to dissem<strong>in</strong>ate theresults of the project, as well as a conference <strong>in</strong> Brussels to dissem<strong>in</strong>ate the firstma<strong>in</strong> results to key EU leaders <strong>in</strong> the relevant areas of arts, culture, education andyouth.Introduction10IntroductionThe DICE Project– What is DICE? The project outl<strong>in</strong>edDICE (“<strong>Drama</strong> <strong>Improves</strong> <strong>Lisbon</strong> <strong>Key</strong> <strong>Competences</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong>”) was an<strong>in</strong>ternational EU-supported project. In addition to other educational aims, this two-yearproject was a cross-cultural research study <strong>in</strong>vestigat<strong>in</strong>g of the effects of educationaltheatre and drama on five of the eight <strong>Lisbon</strong> <strong>Key</strong> <strong>Competences</strong>. 1 The research wasconducted by twelve partners (leader: Hungary, partners: Czech Republic, Netherlands,Norway, Palest<strong>in</strong>e, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia, Sweden and UnitedK<strong>in</strong>gdom). All members are highly regarded nationally and <strong>in</strong>ternationally and represent awide variety of formal and non-formal sectors of education.1 In the document, we will sometimes refer to the “<strong>Lisbon</strong> <strong>Key</strong> <strong>Competences</strong>” as “<strong>Key</strong> <strong>Competences</strong>” only.We exam<strong>in</strong>ed the follow<strong>in</strong>g five out of the eight <strong>Key</strong> <strong>Competences</strong>:1. Communication <strong>in</strong> the mother tongue2. Learn<strong>in</strong>g to learn3. Interpersonal, <strong>in</strong>tercultural and social competences, civic competence4. Entrepreneurship5. Cultural expressionFurthermore, we believe that there is a competence not mentioned among the <strong>Key</strong><strong>Competences</strong>, which is the universal competence of what it is to be human. We havecalled this competence “All this and more”, and <strong>in</strong>cluded it <strong>in</strong> the discussion of theresearch results.These six are life-long learn<strong>in</strong>g skills and competences necessary for the personaldevelopment of young people, their future employment, and active European citizenship.The key outcomes of the project are the <strong>Education</strong> <strong>Resource</strong> and the Policy Paper, andhopefully also a long series of publications of the detailed research results <strong>in</strong> future years,beyond the scope of the project.The <strong>in</strong>novative aspect of the project is that this is the first research to demonstrateconnections between theatre and drama activities <strong>in</strong> education and the <strong>Key</strong><strong>Competences</strong>, with the added value that the research results will be widely shared withthe relevant communities and stakeholders. As many of the competences have rarely or11

Introductionnever been exam<strong>in</strong>ed before <strong>in</strong> cross-cultural studies, we also had to <strong>in</strong>vent and developnew measurement tools that might be useful <strong>in</strong> the future for other educational areas aswell. Besides some newly developed questionnaires for children, teachers, theatre anddrama practitioners and external assessors, we devised a toolkit for the <strong>in</strong>dependentobjective observation of educational theatre and drama classes.All materials used were identical <strong>in</strong> all twelve countries, andtherefore are applicable <strong>in</strong> any culture.DICE is not only a two-year-long project, butrather a journey and an enterprise that has justbegun with this research. In the past two yearsseveral hundred people have been work<strong>in</strong>g withus, from peer volunteers to members of nationalAcademies of Science. For some of us, thisproject has been one of the most challeng<strong>in</strong>g, ifnot the most challeng<strong>in</strong>g task of our professionalcareer, someth<strong>in</strong>g we have learned and cont<strong>in</strong>ue tolearn a huge amount from.The Netherlands: LEESMIJ opens the discussion on socially relevant themes by us<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>teractive theatre. LEESMIJ creates awareness and breaks taboos on subjects likeilliteracy, power abuse, bully<strong>in</strong>g and sexual <strong>in</strong>timidation. By us<strong>in</strong>g forum theatre (<strong>in</strong>spiredby Augusto Boal) it goes beyond talk<strong>in</strong>g and th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g; the audience is <strong>in</strong>vited to take anactive role <strong>in</strong> problem solv<strong>in</strong>g and test<strong>in</strong>g possible alternative behaviours on stage, <strong>in</strong> thisway practis<strong>in</strong>g for real life.Poland: University of Gdansk was founded <strong>in</strong> 1970. It is the largest <strong>in</strong>stitution of highereducation <strong>in</strong> the Pomeranian region. It offers the possibility of study<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> almost thirtydifferent fields with over a hundred specialisations. Such fields as Biology, Biotechnology,Chemistry, Psychology and Pedagogy are among the best <strong>in</strong> the country. There arealmost thirty-three thousand students <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>e faculties.The Institute of Pedagogy, which hosts the DICE project <strong>in</strong> the University of Gdansk,educates social workers, culture animators, teachers, etc. It is the only university <strong>in</strong>Poland that offers two-year Postgraduate <strong>Drama</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Studies. Curriculum ofthe studies conta<strong>in</strong>s such courses as: Sociodrama, Psychodrama, Developmental<strong>Drama</strong>, Theatre Workshops, Active Learn<strong>in</strong>g and Teach<strong>in</strong>g Methods, etc. The Instituteof Pedagogy collaborates with Shakespeare Theatre <strong>in</strong> Gdansk for drama <strong>in</strong> educationpracticum for students.IntroductionThe DICE Project– consortium members and partner organisationsHungary: The Káva <strong>Drama</strong>/Theatre <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Association is a public benefitorganisation provid<strong>in</strong>g arts and education projects, operat<strong>in</strong>g as an association s<strong>in</strong>ce1996. As the first Theatre <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> company <strong>in</strong> Budapest the ma<strong>in</strong> task of theCompany is to create complex theatre / drama <strong>in</strong> education programmes, <strong>in</strong> which socialand moral problems are analysed through action with the participants. The young peopleare not only observers, but also the writers, directors and actors of the story which iscreated through th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g, analys<strong>in</strong>g, compression, transformation and <strong>in</strong> many casesthrough perform<strong>in</strong>g certa<strong>in</strong> situations. Kava aims for the highest aesthetic values andthe complex application of various learn<strong>in</strong>g forms. The significance and effect of Kava’sprogrammes for children and youth goes far beyond the traditional frames of theatre.Teach<strong>in</strong>g democracy, exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g age problems, social and moral issues are the focus ofthe work. When work<strong>in</strong>g with children Kava uses theatre as a tool to f<strong>in</strong>d ways towardsa deeper understand<strong>in</strong>g. The Company work with groups of 9-18 year-old children andyoung people – many of them disadvantaged – all over the country.Romania: SIGMA ART Cultural Foundation for Youth is a Cultural-educational andArtistic resource centre which offers support (behaviour, attitude) to young people, artistsand to other organisations which have similar objectives. Founded <strong>in</strong> April 1995,SigmaArt Foundation is the only Theatre <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> group <strong>in</strong> Bucharest, Romania, with strong<strong>in</strong>ternational connections to similar organisations. Us<strong>in</strong>g theatrical techniques, <strong>in</strong> whichsocial and moral problems are analysed through workshops and performances, theyoung people became, <strong>in</strong> time, full participants and leaders of the artistic and educationalprocess. The entire process of select<strong>in</strong>g the scripts and produc<strong>in</strong>g the performances isclosely assisted by professional directors, actors and dancers. The performances takeplace mostly at Sigma Art’s Studio, <strong>in</strong> high schools, universities, professional theatres <strong>in</strong>Bucharest, national and <strong>in</strong>ternational theatre festivals. One of Sigma’s aims is to develop<strong>in</strong> Romania a new method of work<strong>in</strong>g with adults and young people that will have a socialimpact and successfully contribute to social <strong>in</strong>clusion. Basically, Sigma Art Foundation isoriented <strong>in</strong>to two ma<strong>in</strong> activity fields: <strong>Education</strong> and Art performance.Slovenia: Društvo ustvarjalcev Taka Tuka was established <strong>in</strong> the year 2002 as aresult of our years of work with deaf and hard of hear<strong>in</strong>g children and youth <strong>in</strong> the fieldof theatre. We soon discovered that through creativity we can contribute greatly to theirdevelopment on their way to adulthood. The basic aim of the Association is development,research, implementation and promotion of theatre and drama as a tool for personaldevelopment and teach<strong>in</strong>g personal, social and emotional skills.1213

IntroductionThe ma<strong>in</strong> activities of the Club are: creative workshops (theatrical, dance and f<strong>in</strong>e art)for children, young people and adults; sem<strong>in</strong>ars for mentors, teachers of ma<strong>in</strong> streamschools and specialist who work with people with special needs; parent<strong>in</strong>g schools;sem<strong>in</strong>ars for deaf adults. There are more than 60 children <strong>in</strong> the Club and young peopleare permanently <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> different activities.United K<strong>in</strong>gdom: Big Brum Theatre <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Company (Big Brum) is aregistered charity founded <strong>in</strong> 1982 <strong>in</strong> Birm<strong>in</strong>gham, England. Big Brum seeks to providehigh quality theatre <strong>in</strong> education programmes for children and young people of all ageranges and abilities, <strong>in</strong> schools, specialist units, colleges, community environments andarts venues. The Company is committed to br<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g theatre to young people who wouldnot normally have access to it. As practitioners, the Company proceeds from the premisethat children are not undeveloped adults but human be<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> their own right. Art is amode of know<strong>in</strong>g the world <strong>in</strong> which we live and Big Brum uses educational theatre anddrama to work alongside young people to make mean<strong>in</strong>g of their lives and the worldaround them. Big Brum has developed a 15-year artistic relationship with the worldrenowned British dramatist Edward Bond, and his work and theoretical approaches todrama have strongly <strong>in</strong>fluenced the artistic model of the Company.The <strong>Drama</strong> Department has pioneered studies <strong>in</strong> drama education <strong>in</strong> Norway s<strong>in</strong>ce 1971,when the first one-year full time course for drama teachers <strong>in</strong> the Nordic countries wasestablished. The department offers a variety of drama courses, from <strong>in</strong>troductory drama<strong>in</strong> the general teacher education, via Bachelor-level courses, to a 2-year Masters degree<strong>in</strong> drama education.Palest<strong>in</strong>e: Theatre Day Productions (TDP)“I go to the theatre because I want to see someth<strong>in</strong>g new, to th<strong>in</strong>k, to be touched, toquestion, to enjoy, to learn, to be shaken up, to be <strong>in</strong>spired, to touch art.”Theatre Day Productions wants drama, theatre, and creative activities to be a regular partof the lives of young people <strong>in</strong> Palest<strong>in</strong>e so that kids can f<strong>in</strong>d their <strong>in</strong>dividual voices, theirsense of self, and discover their creative life.The Arabic name of the company, "Ayyam Al Masrah" (Theatre Days) comes from thenotion that some day each Palest<strong>in</strong>ian child will have at least one ‘theatre day’ dur<strong>in</strong>g his orher school year. TDP makes plays with adults and performs for kids. We also make playswith kids who perform for kids. TDP has set <strong>in</strong> motion both a youth theatre company and anactors tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g programme. The programme is carried out on a regional basis: at present <strong>in</strong>the Gaza Strip and <strong>in</strong> the West Bank.IntroductionCzech Republic: The Charles University founded <strong>in</strong> 1348 is one of the oldestuniversities <strong>in</strong> the world and nowadays belongs to the most em<strong>in</strong>ent educational andscientific establishments <strong>in</strong> the Czech Republic, which are recognised <strong>in</strong> both theEuropean and global context. Scientific and research activities form the basis on whichthe Doctoral and Masters programmes are based at Charles University. Over 42,400students study at Charles University <strong>in</strong> more than 270 accredited academic programmeswith 600 departments.The Department of <strong>Education</strong> hosts the DICE project. <strong>Drama</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> is part of ThePersonal and Social <strong>Education</strong>, which is one of the specialisations of The Department of<strong>Education</strong>. We also co-operate with The Theatre Faculty of the Academy of Perform<strong>in</strong>gArts <strong>in</strong> Prague, which among others educates drama teachers.Norway: Bergen University College is a state <strong>in</strong>stitution of higher education,established <strong>in</strong> August 1994 by the merg<strong>in</strong>g of six former <strong>in</strong>dependent colleges <strong>in</strong> Bergen,Norway. The total number of students is about 7,000, and there are 750 academic andadm<strong>in</strong>istrative staff.Bergen University College (Høgskolen i Bergen) is organised <strong>in</strong> 3 faculties: Faculty of<strong>Education</strong>, Faculty of Eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g, Faculty of Health and Social Sciences. The Collegehas a strong tradition with<strong>in</strong> teacher education <strong>in</strong> the arts: drama, dance, music, visualarts and Norwegian (language and literature). The Faculty of <strong>Education</strong> has a centre forarts, culture and communication (SEKKK).Portugal: The mission of the Technical University of <strong>Lisbon</strong> (UTL) is to promote,develop and transmit scientific, technical and artistic knowledge to the highest standards,encourag<strong>in</strong>g research, <strong>in</strong>novation and entrepreneurship, and adapt<strong>in</strong>g to the chang<strong>in</strong>gneeds of society <strong>in</strong> terms of ethics, culture and <strong>in</strong>ternationalisation.UTL is a 21 st -century research European university, alert to the new challenges posed bysociety, and a leader <strong>in</strong> its areas of knowledge where professionals and researchers aretra<strong>in</strong>ed to the highest standards.The Faculty of Human K<strong>in</strong>etics (FMH) is the oldest sports and physical educationfaculty <strong>in</strong> Portugal. It became part of the Technical University of <strong>Lisbon</strong> <strong>in</strong> 1975. It is thefruit of its long history, marked by successive reformulations of its objectives and by itsadaptation to society’s needs, as these were <strong>in</strong>terpreted by the <strong>in</strong>stitutions that precededit – the National Institute of Physical <strong>Education</strong> (INEF) from 1940 to 1975 and the HigherInstitute of Physical <strong>Education</strong> (ISEF) up to 1989.Orig<strong>in</strong>ally an <strong>in</strong>stitution that focused on physical education <strong>in</strong> schools, with a strongemphasis on pedagogy, the Faculty is nowadays open to a wider range of study areasof <strong>in</strong>terest to different sectors of society – the education system, sports, health, <strong>in</strong>dustry,and the arts – with which it cooperates <strong>in</strong> a lively and fruitful way.1415

IntroductionSerbia: NGO CEDEUM Centre for <strong>Drama</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> and Art was founded onOctober 29th 1999, but its founders have been cont<strong>in</strong>ually work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> this field for thepast twenty-five years, as promoters of drama/theatre <strong>in</strong> education and arts. CEDEUMgathers experts from this field <strong>in</strong> Belgrade and has a widespread network of associates,both from Belgrade and the whole country. The goal of CEDEUM is further promotionof drama and theatre <strong>in</strong> all aspects of educative, artistic and social work throughprojects, workshops, sem<strong>in</strong>ars, expert meet<strong>in</strong>gs and work presentations. CEDEUM isparticularly engaged <strong>in</strong> education of educators and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g of artists, as well as sem<strong>in</strong>arsand tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g programmes based on <strong>Drama</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> and Theatre <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong>methodology for pre-school teachers, and teachers <strong>in</strong> elementary and secondary schools<strong>in</strong> Serbia. CEDEUM experts are active <strong>in</strong> the process of <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g drama <strong>in</strong> schools, andtake an active role towards <strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g national policies for promotion and <strong>in</strong>troductionof dramatic activities <strong>in</strong> the educational and cultural system and social work. CEDEUMis also an organiser of “Bitef Pollyphony”: a special drama/theatre programme with<strong>in</strong>the Belgrade International Theatre Festival BITEF – New Theatrical Trends (mid-September) focused on national, regional and <strong>in</strong>ternational exchange of drama/theatreexperiences, collaboration, network<strong>in</strong>g, workshops and work presentations <strong>in</strong> the field ofarts, education and social work. CEDEUM is a member and National Centre of IDEA –International <strong>Drama</strong>/Theatre and <strong>Education</strong> Association.Sweden: Culture Centre for Children and Youth <strong>in</strong> Umeå develops and supportscultural activities for the younger generation <strong>in</strong> Umeå, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g networks for support andco-operation <strong>in</strong> this area, <strong>in</strong>-service tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> relevant fields for teachers and others whocome <strong>in</strong>to contact with children and young people <strong>in</strong> the course of their work, culturalprogrammes for pre-schools and other types of school, and public performances forchildren and family audiences.Cultural education projects are conducted <strong>in</strong> schools and <strong>in</strong> the form of tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g andguidance for teach<strong>in</strong>g staff <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> creative activities for children and young people.The "Teatermagas<strong>in</strong>et" drama groups for children and young people <strong>in</strong> the age range 10-19 are a major aspect of the operations; and theatre groupsfor physically impaired children are a high priority, as isthe use of Theatre <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong>. A drama festivalwith all children takes place <strong>in</strong> May every year.The City of Umea is the largest city <strong>in</strong> northernSweden and also one of the fastest grow<strong>in</strong>gcities. Umeå has two universities, and apopulation of 114,000, with an average ageof 38. Over half of the people who live hereare from outside the region. Umeå will be theEuropean Capital of Culture <strong>in</strong> 2014, along withRiga. Umeå wishes to establish itself as one of Europe´s many cultural capitals. A proud,forward-th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g city <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>tegrated and multifaceted Europe built on participationand co-creation, characterised by curiosity and passion. The program of Umeå 2014is <strong>in</strong>spired by the eight Sami seasons, and the year will entail many opportunities for<strong>in</strong>spir<strong>in</strong>g meet<strong>in</strong>gs and cultural exchanges.To contact any of the consortium members see Appendix C<strong>Education</strong>al Theatre and <strong>Drama</strong>– What is it?The children are watch<strong>in</strong>g a refugee girl, Amani, and a boy, George, <strong>in</strong>teract <strong>in</strong> a disusedrailway station. Amani and George are played by two actors <strong>in</strong> role. The <strong>in</strong>teraction isfraught with tension. Amani is frightened, George is aggressive - he is frightened too. Theycannot speak to each other. One of the pupils, a girl aged seven, a girl who is often quiet,distant even, taps one of the adults work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the programme on the shoulder. “I knowwhat the problem is”, she says. The adult gets the attention of the actor facilitat<strong>in</strong>g theprogramme, <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g that the child is prepared to share her understand<strong>in</strong>g with the restof her peers. “His story is her story” she observes with quiet confidence, “and her story ishis story, but they don’t realise it.” The significance was apparent to everyone <strong>in</strong> the room,it was held <strong>in</strong> a portentous silence. The task for everyone <strong>in</strong>volved now was to deepen thisunderstand<strong>in</strong>g and share it with George and Amani. This was the stuff of real drama.Suitcase – a Theatre In <strong>Education</strong> programme for children aged 6-7 years oldThe drama of – As ifLet’s beg<strong>in</strong> with a broad def<strong>in</strong>ition of the mean<strong>in</strong>g of drama, which derives from the Greekword Dran – to do. <strong>Drama</strong> is someth<strong>in</strong>g of significance that is ‘done’ or enacted. In ourwork it is action explored <strong>in</strong> time and space <strong>in</strong> a fictional context.<strong>Drama</strong> and theatre is a shared experience among those <strong>in</strong>volved either as participant oraudience where they suspend disbelief and imag<strong>in</strong>e and behave as if they were otherthan themselves <strong>in</strong> some other place at another time. There are many aspects to theimag<strong>in</strong>ed experience of as if.<strong>Drama</strong> is a framed activity where role-tak<strong>in</strong>g allows the participants to th<strong>in</strong>k or/andbehave as if they were <strong>in</strong> a different context and to respond as if they were <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong>a different set of historical, social and <strong>in</strong>terpersonal relationships. This is the source ofdramatic tension. In drama we imag<strong>in</strong>e the real <strong>in</strong> order to explore the human condition.Introduction1617

IntroductionAct<strong>in</strong>g a role <strong>in</strong> a play, or tak<strong>in</strong>g a role <strong>in</strong> a drama, is a mental attitude, a way of hold<strong>in</strong>gtwo worlds <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d simultaneously: the real world and the world of the dramatic fiction.The mean<strong>in</strong>g and value of the drama lies <strong>in</strong> the dialogue between these two worlds andthe human subjects beh<strong>in</strong>d its representations: the real and the enacted; the spectatorand the participant; the actor and the audience. Even <strong>in</strong> performance we are not simplyshow<strong>in</strong>g to others but also see<strong>in</strong>g ourselves, and because of this, drama is an act of ‘self’creation.DICE – <strong>Education</strong>al Theatre and <strong>Drama</strong>The range of work that has been the subject of this research project is both rich anddiverse. It <strong>in</strong>volves a variety of processes and performance elements <strong>in</strong> a variety ofcontexts us<strong>in</strong>g many different forms and different approaches to drama and theatre. Wedo however share a common concern for the needs of young people and view our workwith<strong>in</strong> an educational framework, whether this is <strong>in</strong> school or another learn<strong>in</strong>g contextsuch as a theatre and drama group or club. We have therefore adopted the generic termof educational theatre and drama to describe the work that the partners <strong>in</strong> the DICEproject do.Why do we differentiate between theatre and drama?To paraphrase Eric Bentley: 2In theatre, A (the actor/enactor) plays B (the role/performance) to C (the audience) whois the beneficiary.<strong>Drama</strong>, on the other hand, is not as concerned with the learn<strong>in</strong>g of theatre-skills,or production, as it is with the construction of imag<strong>in</strong>ed experience. <strong>Drama</strong> createsdramatic situations to be explored by the participants, <strong>in</strong>vit<strong>in</strong>g them to f<strong>in</strong>d out moreabout the process of how the situation comes <strong>in</strong>to be<strong>in</strong>g, to shift perspectives <strong>in</strong> thehere and now, identify and sometimes solve problems and deepen our understand<strong>in</strong>gof them. The focus is on process: it is a social activity that relies on many voices andperspectives, and on role-tak<strong>in</strong>g; that focuses on task rather than <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>in</strong>terests; andthat enables participants to see with new eyes. This approach creates an opportunity toprobe concepts, issues and problems central to the human condition, and builds spacefor reflection to ga<strong>in</strong> new knowledge about the world. <strong>Drama</strong> is more concerned withprovid<strong>in</strong>g the child with lived-through experience, with the enactive moment, rather thanwith perform<strong>in</strong>g the rehearsed moment. It moves along an educational cont<strong>in</strong>uum thatembraces many forms, from simple role play that is very close to child’s play to fullystructuredshar<strong>in</strong>g (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g show<strong>in</strong>g); but the focus rema<strong>in</strong>s on identify<strong>in</strong>g opportunitiesfor learn<strong>in</strong>g and how to organise these.IntroductionThe work explored <strong>in</strong> this publication, and we suspect the work of practitionerseverywhere, functions along a cont<strong>in</strong>uum, with process at one end, mov<strong>in</strong>g on throughexplor<strong>in</strong>g, shar<strong>in</strong>g, craft<strong>in</strong>g, present<strong>in</strong>g, and assess<strong>in</strong>g, towards performance at the other.The fundamental difference between the two ends of the spectrum is the differencebetween process and product.The creation and craft<strong>in</strong>g of a piece of theatre has the audience as its focus. Theprocess of mak<strong>in</strong>g theatre can be educative <strong>in</strong> itself – we need to understand what weare perform<strong>in</strong>g to an audience, we learn skills <strong>in</strong> order to present a play text – but thefunction of theatre, irrespective of what an <strong>in</strong>dividual may get out of perform<strong>in</strong>g, is toshow to others.Performance however requires depth <strong>in</strong> order to be an event rather than an empty effect.Theatre cannot be theatre unless the actor is consciously divided with<strong>in</strong> the aestheticspace, both self and not self – I and not I; unless there is a division between the aestheticspace and the audience; unless the dramatic event unlocks or accesses for the audiencethe most extreme situations, dilemmas and emotions concern<strong>in</strong>g the gamut of humanexperience – be they spiritual, emotional, psychological, social, physical, etc.In drama, A (the actor/enactor) is simultaneously B (role) and C (audience,) throughparticipation and observation, <strong>in</strong> a process of percipience (a process of both observ<strong>in</strong>gand participat<strong>in</strong>g).<strong>Education</strong>ally speak<strong>in</strong>g some of our work tra<strong>in</strong>s youngpeople <strong>in</strong> theatre and drama skills <strong>in</strong> order that theycan perform <strong>in</strong> theatre or pass those skills on toothers through teach<strong>in</strong>g. But there is also a deeperconcern and a wider potential <strong>in</strong> educational theatreand drama: to use dramatic art to connect thoughtand feel<strong>in</strong>g so that young people can explore andreflect subject matter, test and try out new ideas,acquire new knowledge, create new values, andbuild self-efficacy and self-esteem.2 Bentley, Eric (1964). The Life of <strong>Drama</strong>. New York: Applause Theatre Books.1819

IntroductionThe DICE Project – Our ethos“I go to the theatre because I want to see someth<strong>in</strong>g new, to th<strong>in</strong>k, to be touched, toquestion, to enjoy, to learn, to be shaken up, to be <strong>in</strong>spired, to touch art.”– Child <strong>in</strong> Palest<strong>in</strong>e“It helps when you’re stuck for words; when you act it out people can see what you’reth<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g. But when you’re [only] say<strong>in</strong>g it, they’re just go<strong>in</strong>g ‘mmm, OK’ - they don’t reallyunderstand. I th<strong>in</strong>k people f<strong>in</strong>d it better to learn when they’re do<strong>in</strong>g practical stuff and notjust sitt<strong>in</strong>g there writ<strong>in</strong>g or listen<strong>in</strong>g.” – Child <strong>in</strong> Birm<strong>in</strong>gham“A child may absorb all the skills of a closed society and not have the ability to judge orquestion the values of that society. We may need other ways to open a child’s m<strong>in</strong>d tothe deeper questions about society and human existence, not only to challenge the childbut to get the child to challenge us and our culture. Perhaps there is someth<strong>in</strong>g moreimportant than the develop<strong>in</strong>g of cognitive skills, perhaps we can help even the youngestchild to embark on a search for wisdom, the development of that child’s own values andphilosophy of life.” – Teach<strong>in</strong>g Children to Th<strong>in</strong>k, Robert Fisher (1990)If we are to address well-founded concerns about ‘social cohesion and develop<strong>in</strong>gdemocratic citizenship’ we believe that there needs to be a new paradigm <strong>in</strong> education,an approach that goes beyond the transmission model that is currently predom<strong>in</strong>antwhich requires that the child learn ‘ready-made’ testable knowledge focusedpredom<strong>in</strong>antly on pass<strong>in</strong>g the tests. Teachers f<strong>in</strong>d it <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly difficult to see the youngdevelop<strong>in</strong>g human be<strong>in</strong>gs beh<strong>in</strong>d the target grades and assessment process. And forthose who do, <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly restrictive and proscriptive curricula make it very difficult forthem to access that young human be<strong>in</strong>g. That many teachers do is a testament to theircommitment to their pupils and to learn<strong>in</strong>g. Programmes such as PISA (The Programmefor International Student Assessment), 3 which aim to ‘improve’ educational policiesand outcomes through regular evaluations, focus on the k<strong>in</strong>d of measurement that isreductive and cannot take account of potential development.If one believes that poor performance <strong>in</strong> the education system is due primarily tofailures <strong>in</strong> the assessment of teachers and students, then creat<strong>in</strong>g better <strong>in</strong>struments formeasur<strong>in</strong>g how well students are do<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> literacy, numeracy and science makes perfectsense. But the culture of education is rooted <strong>in</strong> a different and far more serious set ofproblems.IntroductionLike-m<strong>in</strong>ded artist educatorsThe ethos underp<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g the DICE project has been developed by the practice of theresearch project itself. It reflects our own learn<strong>in</strong>g, the spirit of our collaboration and theongo<strong>in</strong>g process we are engaged <strong>in</strong> through educational theatre and drama. We do notclaim to be an absolute authority on the theory and practice of educational theatre anddrama. We are a group of artist educators and arts education pedagogues who cametogether because we hold some fundamental values <strong>in</strong> common that underp<strong>in</strong> the workthat we do. Pr<strong>in</strong>cipal among them is a commitment to nurture and develop the young; asdramatic arts educators and practitioners we work with young people and tra<strong>in</strong> others todo so. We proceed from the premise that children and young people are not undevelopedadults but human be<strong>in</strong>gs who have rights, should be treated justly and given equality ofopportunity. We recognise that society too easily forgoes its responsibility to treat youngpeople <strong>in</strong> this way.The need for change“There is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g concern about social cohesion and develop<strong>in</strong>g democraticcitizenship; this requires people to be <strong>in</strong>formed, concerned and active. The knowledge,skills and attitudes that everyone needs are chang<strong>in</strong>g as a result.”– Proposal for a Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Councilon key competences for lifelong learn<strong>in</strong>g, p3.There are essentially two ways by which we organise andmanage our understand<strong>in</strong>g of the world: logicalscientificth<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g, and narrative th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g. 4 Thetraditional education system is tied to the formerand treats the narrative arts as an ‘added value’rather than a necessity. But it is <strong>in</strong> the narrativemode that one can construct an identity and f<strong>in</strong>da place <strong>in</strong> one's culture. <strong>Education</strong> must alsocultivate this mode of th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g and do<strong>in</strong>g, andnurture it; our future society depends upon it. Weneed a fusion of both modes of th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g to createthe active citizens of the future.The power of educational theatre and drama<strong>Education</strong>al theatre and drama can be a dynamic tool for achiev<strong>in</strong>g the fusion of thesetwo modes of th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g, a holistic approach to the child that contextualises and groundslearn<strong>in</strong>g both socially and historically.3 Co-ord<strong>in</strong>ated by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), PISA is a worldwideevaluation of 15-year-old school children's academic performance. It was first <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong> 2000 and isrepeated every three years.4 See Bruner, Jerome (1996). The Culture of <strong>Education</strong>, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.2021

IntroductionIn educational theatre and drama our engagement is both <strong>in</strong>tellectual and emotional,mak<strong>in</strong>g learn<strong>in</strong>g affective. We cannot 'give' someone our understand<strong>in</strong>g, realunderstand<strong>in</strong>g is felt. Only if the understand<strong>in</strong>g is felt can it be <strong>in</strong>tegrated <strong>in</strong>to our m<strong>in</strong>dsand shape our values.<strong>Education</strong>al theatre and drama is empower<strong>in</strong>g and cultivates self-efficacy and builds selfconfidence.In daily life, which proceeds at such a pace, it is hard to see our ‘self’ fromwith<strong>in</strong> a situation and to exercise control over our thoughts and feel<strong>in</strong>gs. When we work<strong>in</strong> the drama mode we develop our ‘self-spectator’, an ability to be conscious of ourselves<strong>in</strong> a given situation. This helps us to take responsibility for ourselves; if we cannot do thiswe cannot take responsibility for others.Rather than fear the ‘other’, which foments prejudice and hatred, educational theatre anddrama encourage us to explore how others th<strong>in</strong>k and feel. Be<strong>in</strong>g able to ‘step <strong>in</strong>to theshoes’ of others fosters empathy, without which tolerance and understand<strong>in</strong>g is muchharder to come by.<strong>Education</strong>al theatre and drama cultivates the imag<strong>in</strong>ation, utilis<strong>in</strong>g our uniquely humancapacity to imag<strong>in</strong>e the real and envisage the possible. The former provides safety,the latter freedom. This dialectic liberates the m<strong>in</strong>d from the tyranny of the present.<strong>Education</strong>al theatre and drama is the imag<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> action.Democratic citizenship can be served well by participation <strong>in</strong> educational theatre anddrama activity, which is by its very nature both social and collaborative. If the EUproposal on key competences for lifelong learn<strong>in</strong>g seeks to provide personal fulfilmentand <strong>in</strong>clusion, our citizens need to broaden their perspectives <strong>in</strong>to a worldview that asksfundamental questions about what it is to be human. If educational theatre and dramahave an overarch<strong>in</strong>g subject it is this. There is a symbiotic relationship between dramaand democracy which began <strong>in</strong> ancient Greece. Antigone, Medea, Orestes, Oedipus etal dramatised human experience and shared the problems of be<strong>in</strong>g human. <strong>Drama</strong> gavevoice to those - such as women and slaves or victims and the defeated - who largelywent unheard <strong>in</strong> society. The theatre functioned as a truly democratic public space, aspace for reflection that contested the ethos of Greek society. <strong>Education</strong>al theatre anddrama has <strong>in</strong>herited this tradition and provides a safe public space (safe because it isfictional rather than actual) that is both enactive and reflective, for young people to learnand develop a sense of ‘self’, socially and psychologically.The citizens of the future need to be citizens of the world rather than just of a nationstate. <strong>Education</strong>al theatre and drama universalises human experience, transcend<strong>in</strong>gborders and nurtur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terculturalism, and better equipp<strong>in</strong>g us to meet the challengesthat globalisation has created. <strong>Education</strong>al theatre and drama focuses on respond<strong>in</strong>g tothe chang<strong>in</strong>g needs of society; ethically, culturally and <strong>in</strong>terculturally.IntroductionRational thought can be coldly functional, but <strong>in</strong>fused by the imag<strong>in</strong>ation it changes theway we th<strong>in</strong>k: we can reason creatively, humanly. All fields of human thought and actionneed the creativity that the imag<strong>in</strong>ation br<strong>in</strong>gs, to go beyond facts and the <strong>in</strong>formationalready given.The imag<strong>in</strong>ation creates human values – and neverbefore has society so needed to utilise it, to f<strong>in</strong>dcreative solutions to human problems, toreflect on society and what makes it worthliv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>, while envisag<strong>in</strong>g new possibilitieswith a better sense of where we are go<strong>in</strong>gand with deep convictions about what k<strong>in</strong>dof people we want to be.The imag<strong>in</strong>ation is a tool for learn<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g higher thought processes thatcan br<strong>in</strong>g about a deep penetration of anysubject matter under exploration, enrich<strong>in</strong>gthe acquisition of new knowledge and concepts.The paradigm of educational theatre and drama gives young people their <strong>in</strong>dividual andcollective voice. There are no right or wrong answers to complex questions to do withhow we live our lives and understand the world. The world is an open question not aclosed one with a ready-made answer. In the narrative mode of th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g learners are notimitative but are given the <strong>in</strong>itiative whereby they become stewards of their own learn<strong>in</strong>g.The work we doThe work of the partners of the DICE project uses educational theatre and drama to workalongside young people <strong>in</strong> order to help them make mean<strong>in</strong>g of their lives and the worldaround them. In our daily work with children and young adults, educational theatre anddrama is used as a means to f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g a deeper understand<strong>in</strong>g of many different questionsand complex problems. It creates social awareness and breaks taboos, it creates thespace (through performance, participatory drama and workshop activity) to analyse socialand moral problems.<strong>Education</strong>al theatre and drama is such a powerful tool because it is based on text,image and action: an image l<strong>in</strong>gers <strong>in</strong> the m<strong>in</strong>d long after the words have been forgotten.We often learn best through do<strong>in</strong>g, and educational theatre and drama is enactive –2223

Introductionexperienced <strong>in</strong> the moment. Our work often seeks, <strong>in</strong> time, to enable the participantsthemselves to become leaders of the artistic and educational process. We work withchildren and young people <strong>in</strong> state / public schools, special schools and <strong>in</strong> after-schoolactivities. The participants have different social and economic backgrounds and differentneeds: some are deaf and hard of hear<strong>in</strong>g, others have learn<strong>in</strong>g or emotional andbehavioural difficulties, and some are often deemed to be ‘less able’ or academic failures.Daily we re-discover that our work empowers every child because it is <strong>in</strong>clusive, and that<strong>in</strong> educational theatre and drama young people stand ‘a head taller than themselves’.Research F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs – A summary of key f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsThe DICE research was a longitud<strong>in</strong>al cross-cultural study, which basically means thatwe have been measur<strong>in</strong>g the effect of educational theatre and drama <strong>in</strong> different cultures(cross-cultural) over a period of time (longitud<strong>in</strong>al).As outl<strong>in</strong>ed earlier <strong>in</strong> The DICE Project – what is DICE? The project outl<strong>in</strong>ed, weexam<strong>in</strong>ed the follow<strong>in</strong>g five out of the eight <strong>Lisbon</strong> <strong>Key</strong> <strong>Competences</strong>:• Communication <strong>in</strong> the mother tongue• Learn<strong>in</strong>g to learn• Interpersonal, <strong>in</strong>tercultural and social competences, and civic competence• Entrepreneurship• Cultural expressionAnd we added our own:• All this and more, which is the universal competence of what it is to be humanand we <strong>in</strong>cluded it <strong>in</strong> the discussion of the research results.In the f<strong>in</strong>al database we have data from 4,475 students altogether, from 12 differentcountries, who have participated <strong>in</strong> 111 different types of drama programmes. We havecollected data from the students, their teachers, theatre and drama programme leaders,<strong>in</strong>dependent observers, external assessors and key theatre and drama experts as well.The research design was complex, the research sample was large and rich, and results<strong>in</strong> detail are planned to be published over forthcom<strong>in</strong>g years.What does the research tell us about those students who regularlyparticipate <strong>in</strong> educational theatre and drama activities?• are assessed more highly by their teachers<strong>in</strong> all aspects,• feel more confident <strong>in</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g andunderstand<strong>in</strong>g tasks,• feel more confident <strong>in</strong> communication,• are more likely to feel that they arecreative,• like go<strong>in</strong>g to school more,• enjoy school activities more,• are better at problem solv<strong>in</strong>g,• are better at cop<strong>in</strong>g with stress,• are significantly more toleranttowards both m<strong>in</strong>orities and foreigners,• are more active citizens,• show more <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> vot<strong>in</strong>g at any level,• have more <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> participat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> public issues,• are more empathic: they have concern for others,• are more able to change their perspective,• are more <strong>in</strong>novative and entrepreneurial,• show more dedication towards their future and have more plans,• are much more will<strong>in</strong>g to participate <strong>in</strong> any genre of arts and culture, and not justperform<strong>in</strong>g arts, but also writ<strong>in</strong>g, mak<strong>in</strong>g music, films, handicrafts, and attend<strong>in</strong>g allsorts of arts and cultural activities,• spend more time <strong>in</strong> school, more time read<strong>in</strong>g, do<strong>in</strong>g housework, play<strong>in</strong>g, talk<strong>in</strong>g,spend<strong>in</strong>g time with family members and tak<strong>in</strong>g care of younger brothers and sisters.In contrast, they spend less time with watch<strong>in</strong>g TV or play<strong>in</strong>g computer games,• do more for their families, are more likely to have a part-time job and spend moretime be<strong>in</strong>g creative either alone or <strong>in</strong> a group. They go more frequently to thetheatre, exhibitions and museums, and the c<strong>in</strong>ema, and go hik<strong>in</strong>g and bik<strong>in</strong>g moreoften,• are more likely to be a central character <strong>in</strong> the class,• have a better sense of humour,• feel better at home.Section B of this book <strong>in</strong>cludes short extracts about the most relevant results related toeach of the key competences. If you would like to know more details about the researchmethodology and the results, read Section B of this book’s tw<strong>in</strong>: “The DICE has beencast – research f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs and recommendations on educational theatre and drama”.IntroductionHere is a brief summary: compared with peers who had not been participat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> anyeducational theatre and drama programmes, those who had participated <strong>in</strong> educationaltheatre and drama2425

thoughts, feel<strong>in</strong>gs and facts <strong>in</strong> both oral and written form (listen<strong>in</strong>g, speak<strong>in</strong>g, read<strong>in</strong>gand writ<strong>in</strong>g), and to <strong>in</strong>teract l<strong>in</strong>guistically <strong>in</strong> an appropriate way <strong>in</strong> the full range of societaland cultural contexts – education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, work, home and leisure, accord<strong>in</strong>g to theirspecific needs and circumstances.*It is recognised that the mother tongue may not <strong>in</strong> all cases be an official language of the MemberState, and that ability to communicate <strong>in</strong> an official language is a pre-condition for ensur<strong>in</strong>gfull participation of the <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>in</strong> society. Measures to address such cases are a matter for<strong>in</strong>dividual Member StatesHow educationaltheatre and dramaimproves keycompetencesA brief <strong>in</strong>troduction to the documentedpracticesBelow are def<strong>in</strong>itions of five of the eight competences as def<strong>in</strong>ed by theEU, which the DICE project has been research<strong>in</strong>g.<strong>Key</strong> <strong>Competences</strong>No1. Communication <strong>in</strong> the mother tongue*Def<strong>in</strong>ition: Communication <strong>in</strong> the mother tongue is the ability to express and <strong>in</strong>terpretNo2. Learn<strong>in</strong>g to learnDef<strong>in</strong>ition: ‘Learn<strong>in</strong>g to learn’ is the ability to pursue and persist <strong>in</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g. Individualsshould be able to organise their own learn<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g through effective management oftime and <strong>in</strong>formation, both <strong>in</strong>dividually and <strong>in</strong> groups. Competence <strong>in</strong>cludes awarenessof one’s learn<strong>in</strong>g process and needs, identify<strong>in</strong>g available opportunities, and the abilityto handle obstacles <strong>in</strong> order to learn successfully. It means ga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, process<strong>in</strong>g andassimilat<strong>in</strong>g new knowledge and skills as well as seek<strong>in</strong>g and mak<strong>in</strong>g use of guidance.Learn<strong>in</strong>g to learn engages learners to build on prior learn<strong>in</strong>g and life experiences <strong>in</strong>order to use and apply knowledge and skills <strong>in</strong> a variety of contexts – at home, atwork, <strong>in</strong> education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. Motivation and confidence are crucial to an <strong>in</strong>dividual’scompetence.No3. Interpersonal, <strong>in</strong>tercultural and social competences, and civic competenceDef<strong>in</strong>ition: These competences cover all forms of behaviour that equip <strong>in</strong>dividuals toparticipate <strong>in</strong> an effective and constructive way <strong>in</strong> social and work<strong>in</strong>g life, and particularly<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly diverse societies, and to resolve conflict where necessary. Civiccompetence equips <strong>in</strong>dividuals to fully participate <strong>in</strong> civic life, based on knowledge ofsocial and political concepts and structures and a commitment to active and democraticparticipation.No4. EntrepreneurshipDef<strong>in</strong>ition: Entrepreneurship refers to an <strong>in</strong>dividual’s ability to turn ideas <strong>in</strong>to action. It<strong>in</strong>cludes creativity, <strong>in</strong>novation and risk tak<strong>in</strong>g, as well as the ability to plan and manageprojects <strong>in</strong> order to achieve objectives. This supports everyone <strong>in</strong> day to day life at homeand <strong>in</strong> society, employees <strong>in</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g aware of the context of their work and be<strong>in</strong>g able toseize opportunities, and is a foundation for more specific skills and knowledge needed byentrepreneurs establish<strong>in</strong>g social or commercial activity.No5. Cultural expressionDef<strong>in</strong>ition: Appreciation of the importance of the creative expression of ideas, experiencesand emotions <strong>in</strong> a range of media, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g music, perform<strong>in</strong>g arts, literature, and thevisual arts.Documented practices26 27

Documented practicesSkills: Self-expression through the variety of media […]. Skills <strong>in</strong>clude also the ability torelate one’s own creative and expressive po<strong>in</strong>ts of view to the op<strong>in</strong>ions of others. Attitude:A strong sense of identity is the basis for respect and [an] open attitude to diversity ofcultural expression.The partners also added a sixth competence to reflect our practice and to accompany theother five.No6. All this and more.….Def<strong>in</strong>ition: The No6 on our DICE <strong>in</strong>corporates the first five but adds a new dimension,because educational theatre and drama is fundamentally concerned with the universalcompetence of what it is to be human. An <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g concern about the coherence ofour society and develop<strong>in</strong>g democratic citizenship requires a moral compass by whichto locate ourselves and each other <strong>in</strong> world and to beg<strong>in</strong> to re-evaluate and create newvalues; to imag<strong>in</strong>e, envisage, a society worth liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>, and liv<strong>in</strong>g with a better sense ofwhere we are go<strong>in</strong>g with deep convictions about what k<strong>in</strong>d of people we want to be.The universal competence of what it is to be human rema<strong>in</strong>s the benchmark fromwhich all else follows <strong>in</strong> the work that we do, and we believe that this should underp<strong>in</strong> allour efforts as artist educators.Section B is broken down <strong>in</strong>to the six competences. The impact of educational theatreand drama activities on each competence is illustrated by documented practice, two percompetence. Each documented practice is broken down <strong>in</strong>to three sections:• the project/workshop/production – what we were do<strong>in</strong>g and how we did it.• our approach – an <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to some of the th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g guid<strong>in</strong>g our practice.• teachers: a guide to practice – recommendations, issues and questions to consider ifyou were to take on the development of this work.The f<strong>in</strong>al part of each competence <strong>in</strong> Section B <strong>in</strong>cludes short extracts about the mostrelevant research results related to each of the key competences.Each documented practice is a reflection of the stage of development the partnershave reached; it is an attempt to articulate what we understand about the role ofeducational theatre and drama and our practice as artist educators.Learn<strong>in</strong>g to learnDef<strong>in</strong>ition: ‘Learn<strong>in</strong>g to learn’ is the ability to pursue and persist <strong>in</strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g. Individuals should be able to organise their own learn<strong>in</strong>g,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g through effective management of time and <strong>in</strong>formation, both<strong>in</strong>dividually and <strong>in</strong> groups. Competence <strong>in</strong>cludes awareness of one’slearn<strong>in</strong>g process and needs, identify<strong>in</strong>g available opportunities, andthe ability to handle obstacles <strong>in</strong> order to learn successfully. It meansga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, process<strong>in</strong>g and assimilat<strong>in</strong>g new knowledge and skills as wellas seek<strong>in</strong>g and mak<strong>in</strong>g use of guidance. Learn<strong>in</strong>g to learn engageslearners to build on prior learn<strong>in</strong>g and life experiences <strong>in</strong> order to useand apply knowledge and skills <strong>in</strong> a variety of contexts – at home, atwork, <strong>in</strong> education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. Motivation and confidence are crucialto an <strong>in</strong>dividual’s competence.1. Suitcase – drama workshop,Big Brum Theatre <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Companya. Workshop SummaryEvery suitcase tells a story and this participatory workshop explores the story of amigrant/refugee, us<strong>in</strong>g a suitcase as the pivotal object. It is one session made up of 6units. It starts by creat<strong>in</strong>g a site from which the participants build the story.There is no pre-determ<strong>in</strong>ed end or desired outcome. There isa structured sequence to the workshop but also greatfreedom for the participants to be creative with<strong>in</strong>it, so that the structure develops <strong>in</strong> responseto what the young people br<strong>in</strong>g to it andhow they <strong>in</strong>terpret the material. There isno ‘message’ for the Facilitator to transmit.The Facilitator is the mediator betweenthe group and the situation (the world ofthe drama and its layers of mean<strong>in</strong>g) whoassists the participants to seek reason(understand<strong>in</strong>g) through the use of theimag<strong>in</strong>ation. The workshop is <strong>in</strong>tended tohave two primary functions: to create a spacefor the young people to test their values and toYoung people whoregularly participate <strong>in</strong> educationaltheatre and drama activities,when compared to those who donot, are 6.9% more likely to feelthat be<strong>in</strong>g creative is important tothem; their enjoyment of schoolis 2.5% higher; and they feel 6%better at school.Documented practices2829