Scotland's rare tooth fungi: - Plantlife

Scotland's rare tooth fungi: - Plantlife

Scotland's rare tooth fungi: - Plantlife

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

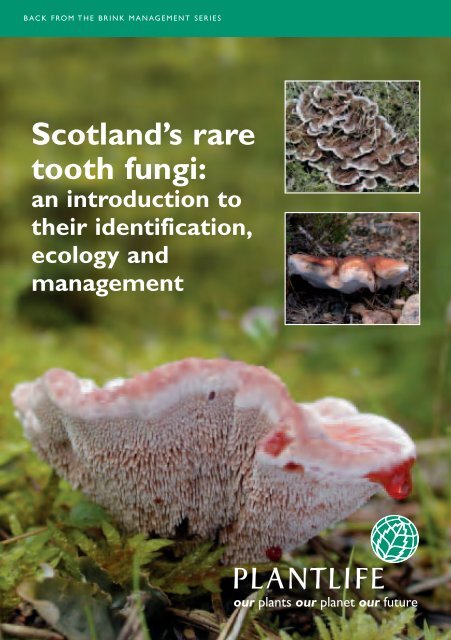

BACK FROM THE BRINK MANAGEMENT SERIESBACK FROM THE BRINK MANAGEMENT SERIESScotland’s <strong>rare</strong><strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong>:an introduction totheir identification,ecology andmanagement3

BACK FROM THE BRINK MANAGEMENT SERIESLeft: Tooth <strong>fungi</strong> habitat on Deeside© Liz HoldenFront cover: main image, Hydnellumpeckii © Mark Gurney, RSPBInset top: Phellodon tomentosus© Liz HoldenInset below: Bankera fuligineoalba© Mark Gurney, RSPB<strong>Plantlife</strong> is the UK’s leading charityworking to protect wild plants and theirhabitats. The charity has 10,500members and owns 23 nature reserves.In 2008, <strong>Plantlife</strong> is 'Lead Partner' for 77species under the UK Government'sBiodiversity Action Plan. Conservationof these species is delivered through thecharity’s Back from the Brink speciesrecovery programme, which is jointlyfunded by Countryside Council forWales, Natural England, Scottish NaturalHeritage, charitable trusts, companiesand individuals. It involves its membersas volunteers (Flora Guardians) indelivering many aspects of this work.<strong>Plantlife</strong>’s head office is in Salisbury,Wiltshire, and the charity has nationaloffices in Wales and Scotland.<strong>Plantlife</strong> ScotlandBalallan HouseAllan ParkStirlingFK8 2QGTel. 01786 478509www.plantlife.org.ukscotland@plantlife.org.uk

BACK FROM THE BRINK MANAGEMENT SERIESHydnellum requiring further taxonomic investigation to define exact species © Mark Gurney, RSPBScotland’s <strong>rare</strong> <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong>: anintroduction to their identification,ecology and managementNot quite animals and certainly not plants,these fascinating organisms are members ofone of the largest kingdoms on the planet, the<strong>fungi</strong>, essential to the health of all ecologicalsystems and without which around 90% of ourhigher plants and trees would not survive.The parts of a fungus that we see aboveground are the spore producing structures,(the ‘fruit bodies’) of a much larger organismthat is mostly hidden from sight andcomposed of a branching network offilamentous cells.This underground network,the ‘mycelium’, enables <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong> to foragefor nutrients and to link up with the roots ofliving trees in a symbiotic ‘ectomycorrhizal’relationship wherein both partners gainnutrients.What are <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong>?‘<strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong>’ are a diverse group of <strong>fungi</strong> thatutilise <strong>tooth</strong> like structures to produce theirspores. Only four of the many genera (groupsof species) that share this character are ofconservation concern in Scotland andconsidered here: Bankera, Hydnellum, Phellodonand Sarcodon.Two other stipitate (stalked) genera couldcause confusion as they have similarmacroscopic structures, but these arewidespread: the Wood Hedgehogs (Hydnum)and Earpick Fungus (Auriscalpium). Other <strong>tooth</strong><strong>fungi</strong> are not stipitate and where they are ofconservation concern, have not yet beenfound fruiting in Scotland.1

BACK FROM THE BRINK MANAGEMENT SERIESHydnellum aurantiacum. © Liz HoldenDistribution in ScotlandThe core concentrations of Scottish <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong>appear to be in the Caledonian pine forests ofthe Central and Eastern Highlands, withscattered records from elsewhere. Certainspecies, including Orange Tooth (Hydnellumaurantiacum) and Greenfoot Tooth (Sarcodonglaucopus) are <strong>rare</strong>ly recorded even within thecore areas.2Tooth <strong>fungi</strong> characteristics● Rather than gills or tubes, the undersides ofthe caps have little <strong>tooth</strong>-like structures tosupport the developing spores.● The four genera of conservation concern inScotland have stalks, known as ‘stipes’ andhence known as ‘stipitate’.● These <strong>fungi</strong> produce relatively long-livedfruit bodies (several weeks in some cases)between early August and October.● Up to ten species, representing all fourgenera, have been found fruiting in closeproximity to each other in ‘hot spot’ clusters.● It appears that these genera do not readilycolonise new sites. Once established at asite their main mode of dispersal is throughvegetative growth with the myceliummoving from tree root to tree root.Wood hedgehogs (Hydnum species) have teethand stipes but are widespread in Scotland and notof conservation concern © Mark Gurney, RSPB

BACK FROM THE BRINK MANAGEMENT SERIESTooth <strong>fungi</strong> habitat● Tooth <strong>fungi</strong> are woodland organisms thataccess nutrients in a partnership withliving trees. In Scotland the host trees arethought to be mainly pine, birch and oak.● Their fruit bodies appear in soil and arenot on dead wood.● There is evidence to suggest that thelarger the area of woodland, the higher thenumber of species (Newton et al, 2002).● As a group they seem to share apreference for fruiting in poor sandy soils,often on banks, tracksides, old quarries orborrow pits where there is a poorlydeveloped humus layer and very littlevascular plant cover.●●●Soils supporting <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong> are usuallywell drained although humidity levels areoften relatively high. Humidity might bemaintained for, example, by proximity towater or overhanging branches.The fruiting success of these <strong>fungi</strong> appearsto be linked to low nitrogen levels in thesoil as well as climatic variables.Fruiting is not limited to old growthforests and fruit bodies do sometimesoccur with young trees or in plantationwoodland on suitable ground.There ishowever, usually a link to old growthforest either through proximity to thathabitat or through scattered old growthforest trees.Ideal <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong> habitat © Stewart Taylor3

BACK FROM THE BRINK MANAGEMENT SERIESBankera fuligineoalba © Liz HoldenThe <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong> generaBankera speciesThe flesh can be quite easily broken andgenerally the caps do not fuse together.Thefruit bodies have white to buff teeth and whitespores.The cap is fleshy and often has debrissticking to it. It is white at first becomingtinged brown with age. Dried material usuallysmells strongly of fenugreek or curry powder.Sarcodon speciesThe flesh can be quite easily broken andgenerally the caps do not fuse together. Fruitbodies have greyish teeth and brown spores.The cap is fleshy, a brown colour and coveredin distinct scales.There is no strong spicy smellwhen dried.Sarcodon squamosus © Liz Holden4

BACK FROM THE BRINK MANAGEMENT SERIESSarcodon glaucopus © Liz HoldenBankera fuligineoalba© Mark Gurney5

BACK FROM THE BRINK MANAGEMENT SERIESHydnellum speciesThe flesh is tough and the caps often fusetogether incorporating surrounding vegetationand debris; there are multiple stipes beneath.Caps have brownish teeth and brown spores.The cap can be thick or thin and whilststarting very pale, becomes some shade ofbrown, with blue, orange or pink tints in somespecies.The caps of thin-fleshed species areoften concentrically zoned.The cut flesh itselfis often zoned and in some species containsbright blue or orange colours. In dampweather fresh fruit bodies of some speciesproduce blood red droplets (guttules).There isno strong spicy smell when dried.Hydnellum peckii © Liz Holden Hydnellum requiring further taxonomicinvestigation to define exact species © Liz Holden Hydnellum caeruleum © Liz Holden6

BACK FROM THE BRINK MANAGEMENT SERIES Hydnellum peckii © David Genney Hydnellum ferrugineum © Mark Gurney RSPB7

Phellodon tomentosus © Liz HoldenPhellodon melaleucus © Mark Gurney RSPBPhellodon speciesThe flesh is tough and the caps often fusetogether incorporating surrounding vegetationand debris; there are multiple stipes beneath.Caps have white teeth and white spores. Capsare often concentrically zoned and colours varyfrom brown to blue black. Dried material usuallysmells strongly of fenugreek or curry powder.Phellodon niger © Liz HoldenLook alike non-target speciesThe Earpick Fungus (Auriscalpium) – is a small,dark brown fungus that grows throughout theyear on old pinecones.The relatively long, thin,hairy stipe is often set to one side of the cap.The Wood Hedgehogs (Hydnum) – have teethmore or less the same colour as the uniformlycoloured cap ie pale cinnamon to buff orterracotta.The spores are whitish.The cap isfleshy and easily broken.Tiger’s Eye (Coltricia perennis) – is common insimilar habitats, has a stipe, tough flesh and thetop of the cap has concentric brown zones likeseveral of the <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong>. Look carefully to findpores rather than teeth below the cap.Why are <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong>of conservation concern?Reports produced during the 1980s and 1990sin parts of western and central Europe indicatedthat fruiting of these <strong>fungi</strong> was in significantdecline and in 1999, concern about their statusin the UK led to a grouped Biodiversity ActionPlan (BAP) being established.The revised 2007BAP list includes one additional species bringingthe total number of species in the plan to 15, ofwhich 13 occur in Scotland.8

Perceived threats● Habitat loss at both macro and micro scalese.g. clear felling, alteration of site conditionsby invasive plants such as bracken orrhododendron or loss of suitable, sandy soilmicrohabitats● Eutrophication of soils through airbornepollution or agricultural run-off● The application of <strong>fungi</strong>cides or substancescontaining nitrogen and / or phosphate● Liming alters the soil pH dramatically.Workin Sweden and Germany has found thatliming was detrimental to establishedectomycorrhizal species (Taylor & Finlay,2003)● Compaction or disturbance of soil bytrampling or machine● Lack of awareness of the habitatrequirements of <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong> amongst landmanagers● Lack of understanding of the ecology andtaxonomy of the groupWhat you can do if you find <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong>● These are species of conservation concernand collection should be kept to theminimum necessary to establishidentification.● Tooth <strong>fungi</strong>, some of which are listed onthe UK BAP (2007) list and in thepreliminary Red List of Threatened Fungi(Evans, 2007), are not currently listed onSchedule 8 of the Wildlife and CountrysideAct (1981).Although a licence from thegovernment is not required to pick fruitbodies, permission of the landowner mustbe sought.● These <strong>fungi</strong> are not poisonous and workingwith the fruit bodies will not require actionbeyond normal health and safetyprocedures. Most species are either tooA survey plot for <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong> © Liz Holden●●●tough or bitter to be edible although someare collected for dying craft materials.Check whether their presence is alreadyrecorded at the site using your own landmanagement records, by checking theFungal Records Database of Britain andIreland through the British MycologicalSociety website or by contacting <strong>Plantlife</strong>Scotland (contact details on back page). Ifthey are already well recorded then there isno need to disturb them further; if not thenadvice can be given on how to proceed.Refer to the management guidelines belowif interventions are proposed for the site.Consider undertaking a simple survey, asthere is very little base line data availablefrom which to assess the impact ofmanagement interventions. Surveys shouldtake place over at least 5 years, as some<strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong> do not fruit regularly. Monthlyvisits from early August to October eachyear are also recommended as somespecies fruit early and others later.Temporarily mark each fruiting site to avoidconfusion in successive monthly visits. GPSreadings, good field notes and photographscan help to accurately map your <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong>and inform future site management.Contact <strong>Plantlife</strong> if assistance is required.9

© Liz HoldenManagement guidelinesIf you are in woodland with suitable host treesand poor sandy soils it is possible that youeither already have <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong>, or if they donot appear to be present, that you couldencourage their presence through appropriatemanagement. Current research (Van der Linde,2008) suggests that the mycelium of <strong>tooth</strong><strong>fungi</strong> can be successfully transferred to newsites on the inoculated roots of seedling trees.This work is at an early stage but may be afuture consideration.General guidelines in areas where <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong>are known to fruit:● The exact ecological requirements ofthese <strong>fungi</strong> are not yet fully understood, sogreat care should be taken when changingthe management of sites known tosupport <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong>.● Ensure contractors and land managers areaware of the presence of <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong>.●●●●●Get to know species specialists and localfungus recording groups who may be able tohelp inform site management and provideregular and relevant advice including how tomonitor any management interventions.In the vicinity of known fruit bodies, maintain awide age structure of trees to increase thelikelihood of continuity of host trees.The exactstocking densities to enable the inoculation ofneighbouring young trees with fungal myceliumhave not been determined in this habitat butwill relate to the extent of the host tree’s ownroot system. Opening up the canopy beyond1.5 times the radius of the canopy is notrecommended close to the known areacolonised by <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong>. It can be difficult toascertain which trees are actually hosting thetarget mycelium; the further development ofmolecular tools will assist with this process inthe future. Meanwhile the maintenance of asustainable buffer zone (a minimum of 50m issuggested) of potential host trees aroundknown fruiting sites is recommended toensure host continuity.Extended rotations, continuous coverforestry and small coupe felling are morelikely to sustain <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong> populations thanclear fell.When carefully applied these formsof management can benefit <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong> byincreasing the longevity of the woodland site,maintaining continuity of hosts (selectivethinning can be used to reduce the likelihoodof felling host trees) and maintainingappropriate environmental conditions suchas humidity.Increase woodland size where possible byextending existing woodlands andincorporating existing woodland fragments.Further research is required to determinewhich areas of the forest are likely to bemost suitable for the mycelia of these <strong>fungi</strong>.10

BACK FROM THE BRINK MANAGEMENT SERIES●●●●●●●It is not yet possible to offer specificmanagement recommendations to favourthe development of these species in thewider forest.Where natural regeneration is notpossible then restocking should be withnative host species.Minimise heavy disturbance andcompaction from vehicle access or foottraffic. Ploughing and scarification shouldbe avoided in areas where <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong> areknown to be fruiting or where there is aplan to encourage the presence of <strong>tooth</strong><strong>fungi</strong>. Even light disturbance should beavoided during the fruiting season.Maintain areas around fruiting <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong>free from the development of humus anddense vascular plant cover. Verge cuttingwith a bar can be appropriate as long asthe dead plant material does notaccumulate to enrich the soil.The effect ofherbicides on <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong> is unknown.At sites threatened by, for example,Rhododendron ponticum or Snowberry(Symphoricarpus albus) take measures tocontrol, contain or eradicate invasive nonnativeplant species using ForestryCommission guidelines on suitabletechniques. Bracken, particularly inriverside locations, can be difficult toaccess by machinery but could be mownor managed by volunteers.Avoid the use of <strong>fungi</strong>cides, lime or theapplication or accidental run off of anynitrogen or phosphorus rich substance inor adjacent to target areas.Monitor the effects of managementinterventions.Remember that it is possible to managefor a range of conservation interests bycreating a mosaic of habitats.Maintenance of paths, roads and car parks inareas known to support <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong>:● Aim for minimal interference with theestablished soil profile e.g. avoid excavationto create foundations or deep layers ofnew surfacing material to level the paths.● Endeavour to retain existing path widthsand edges where <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong> are knownto fruit● New construction materials should belocally sourced if possible and mineral inorigin.Wood chips would not beappropriate.● A few carefully sited borrow pits, awayfrom the locations of the <strong>rare</strong>st <strong>tooth</strong><strong>fungi</strong>, could provide additional suitablehabitat for these species to fruit in. Forthis purpose and where appropriate, it isrecommended that topsoil is not replaced.Excess topsoil should be placed severalmetres into the woodland and away from<strong>tooth</strong> fungus fruiting sites.● Path drainage should be established withcare and in consultation with speciesspecialists.The maintenance of ditches andbanks can be beneficial in somecircumstances.● Material derived from any clearance oftrees should be piled up several metres intothe surrounding woodland if staying on site.● Minimise disturbance and compactionfrom machinery involved in the project, orthe storage of materials.● It is important to maintain the host treesbut it may also be important to have aclear margin between the path edge andthe trees, if that does not compromisehumidity levels.11

BACK FROM THE BRINK MANAGEMENT SERIESRecommended texts and referencesUKBAP species lists and action plans areavailable at www.ukbap.org.ukThe preliminary assessment for the RedData List of Threatened British Fungi (Evans2007) can be found through the BritishMycological Society’s website(www.britmycolsoc.org.uk)D.N. Pegler, P.J. Roberts and B.M. Spooner.Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew 1997 BritishChanterelles and <strong>tooth</strong> <strong>fungi</strong>J. Breitenbach and F. Kränzlin.VerlagMykologia, 1986 Fungi of Switzerland Vol 2Non gilled <strong>fungi</strong>Newton,A.C., Holden, E., Davy, L.M.,Ward,S.D., Fleming, L.V. & Watling, R. (2002). Statusand distribution of stipitate hydnoid <strong>fungi</strong> inScottish coniferous forests. BiologicalConservation (107) 181-192Parfitt, D.,Ainsworth,A.M., Simpson, D.,Rogers,H.J. & Boddy, L. (2007). Molecular andmorphological discrimination of stipitatehydnoids in the generaHydnellum and Phellodon. Mycological Research,111, 761-777.Taylor,A.F.S. & Finlay, R.D. (2003). Effects ofliming and ash application on below groundectomycorrhizal community structure in towNorway Spruce forests. Water, Air and SoilPollution: Focus 3: 63-76, NetherlandsVan der Linde, S. (2008).‘Ecology and conservationof stipitate hydnoid <strong>fungi</strong> associated with ScotsPine’. PhD thesis, University of Aberdeen12Contacts for advice and furtherinformationFor help with reporting or identifying <strong>tooth</strong><strong>fungi</strong> contact,<strong>Plantlife</strong> ScotlandBalallan HouseAllan ParkStirlingFK8 2QGTel. 01786 478509scotland@plantlife.org.ukwww.plantlife.org.ukFor help with contacting mycologicalcontractors and volunteer groups: contact<strong>Plantlife</strong> ScotlandFor help with contacting fungal recordinggroups contact the British Mycological Societyat www.britmycolsoc.org.uk or <strong>Plantlife</strong>ScotlandFor information on dealing with invasive nonnativeplant species see the ForestryCommission Practice Guides for example‘Managing and controlling invasiverhododendron’ by Colin Edwards (2006) atwww.forestry.gov.ukGuidance provided in this leaflet is integratedinto HaRPPS, the Forestry Commission's webbasedinformation and decision support system,providing quick and easy access to informationabout a range of Priority and protectedwoodland species and habitat management:http://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/fr/INFD-758CCA

BACK FROM THE BRINK MANAGEMENT SERIESSarcodon squamosus © Mark Gurney RSPBThis leaflet was written for <strong>Plantlife</strong> Scotlandby Liz Holden, Field Mycologist

BACK FROM THE BRINK MANAGEMENT SERIESBACK FROM THE BRINK MANAGEMENT SERIESPhellodon niger © Mark Gurney, RSPBBritish Lichen Societywww.plantlife.org.ukscotland@plantlife.org.uk<strong>Plantlife</strong> International – The Wild Plant Conservation Charity<strong>Plantlife</strong> ScotlandBalallan House,Allan Park, Stirling FK8 2QGTel. 01786 478509ISBN: 978-1-904749-40-0 © October 2008<strong>Plantlife</strong> International – The Wild Plant Conservation Charity is a charitable company limited by guarantee.Registered Charity Number: 1059559 Registered Company Number: 3166339. Registered in EnglandCharity registered in Scotland no. SC038951Front cover image: Buxbaumia viridis capsules on an alder log Stewart Taylor, RSPB Design: rjpdesign.co.uk Print: crownlitho.co.uk