Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

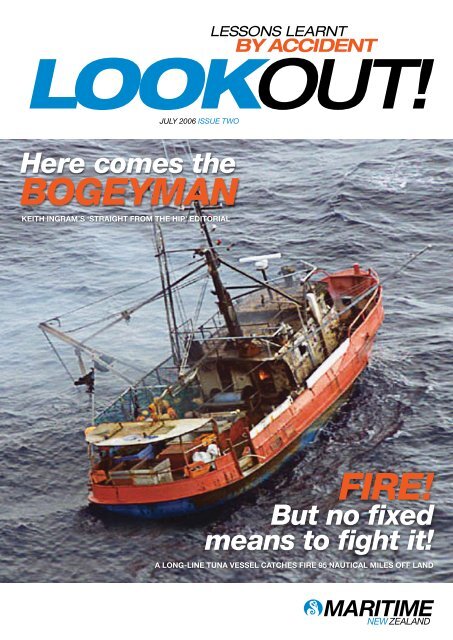

JULY <strong>2006</strong> ISSUE TWOHere comes thebogeymanKeith Ingram’s ‘straight from the hip’ editorialFire!But no fixedmeans to fight it!a long-line tuna vessel catches fire 95 nautical miles off land

ContentsJULY <strong>2006</strong> ISSUE TWO58116 Delayed reaction togas escape7 Too close for comfort!10 Throttle failure off the rocks12 In harms wayIncorrect chartplays part invessel groundingA deep-sea factory trawler groundswhile attempting to berth.Fire! But no fixedmeans to fight it!A long-line tuna vessel catches fire95 nautical miles off land.Simple watertightcommunicationscan save livesA cellphone may have saved the lifeof a recreational boatie.13 Booze + Boat + Bad weather= Death14 Don’t take chanceswhen kayaking!16 Training matters!17 Five thrown from raft15182019 Inadequate fuel tankmounting causes fire21 A moments distractionis all it takes21 Failed hoist wire not upto specification22 Safety bulletinGas detectors canprevent explosionsA recreational skipper is hospitalisedwith severe burns after the stove onhis yacht explodes.Head On?Turn to starboard!A fibreglass launch collides witha passenger ferry at night.Fatigue, thecreeping dangerA skipper is woken suddenly by thesound of his vessel grounding on rocks.Regulars3 Introduction4 Guest Editorial:Here comes the bogeyman

LOOKOUT!IntroductionWelcome once again to Lookout!– <strong>Maritime</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>’s newsafety focused quarterly. Thankyou all for your positive andconstructive feedback on the firstissue – from all accounts it was asought after read by many of you.This issue includes a ‘straight from the hip’ guest editorial byKeith Ingram. Keith, as many of you will know, is a professionalmariner with some 40 years of sea-going experience operatingall types of vessels. He is the publisher and editor of ProfessionalSkipper, NZ Aquaculture and NZ Workboat Review magazines,and a well-known and respected member of our industry.As illustrated by the stories in this issue, accidents are causedby a variety of factors. With a little foresight and planning, someof these could have well been avoided, whereas others wouldhave occurred no matter how well prepared those involved were– yet had their reactions been different the outcome may wellhave been altered.I am sure you will find this issue informative and thoughtprovoking – do pass it on to your colleagues and crew or contactany one of our offices if you’d like more copies. The full accidentreports are available on our website www.maritimenz.co.nz or bycalling our toll free number 0508 22 55 22.As always, we welcome your feedback on Lookout! and its content.Russell KilvingtonDirector of <strong>Maritime</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>LOOKOUT! JULY <strong>2006</strong>

LOOKOUT!GuesteditorialIncorrect chartplays part invessel groundingIt won’t happen to me! – is a generalfeeling of complacency that surroundsthe maritime industry. Unfortunately all tooften Mother Nature proves us wrong asthe facts demonstrate. As seafarers wecontinue to fail in a rare display of humanweakness at the most inappropriate times.Accidents, incidents and mishaps remainan unfortunate part of our everydaylives as we go about our business at sea.Sometimes they are the result of a calculatedrisk or a manoeuvre gone wrong. Atothers the cause may be incompetenceor it may just be plain bad luck. Whateverthe cause, the end result is that a reportmust be logged and invariably we receivea visit from the “Bogeyman” or in morecorrect terms the accident investigator.It’s at this point where honesty is thebest policy. Yeah right you say! Well yeahit is because the primary reasons for anyinvestigation are two-fold -1. To determine the nature and causeof an accident, incident, or mishap sowe as an industry might learn from ourmistakes. How often have we all thought,“But there for the grace of God go I.”2. To determine (and this is the moreunpleasant aspect) if a non-compliant ornegligent act was the cause, the outcomeof which may result in a prosecution– hence, our fear of the “bogeyman.” It isthis aspect of any investigation that bringsout our best defences and our inability torecall the facts.Which is why <strong>Maritime</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>has introduced a 3-tier reporting andHere comes thebogeymaninvestigating system. An excellent, proactivemove where levels 1 and 2 involveinvestigations and reports, but only level1 investigations may involve the issue ofa caution and may lead to a prosecution.For this new reporting system towork there must be a level of trust onboth sides. If not the system will fail, andrespect and credibility will be lost.As an industry commentator I amfrequently saddened to hear of yetanother life lost or the demise of anotherLives are at stake,ours included, andonly training andgood planning canreduce the odds inour favour.fine vessel. Even the most respectedand experienced seamen are coming togrief. Why can this be? Have we got tothe stage where our industry is no longerfinancially viable, where the constantcost cuts are taking their toll on training,maintenance and safety? Our fishingfleet is a sad reminder of the gloriousdays gone by, when fishermen could goto sea and make a quid. Boats were wellmaintained and we took pride in them.The scruffy tired-looking vessels yousee today are not just the preserve ofthe fishing industry alone. Look aroundour ports and it’s not hard to see vesselsfrom all sectors in desperate need of a bitof TLC.The words of my first skipper still ringin my ears today: “She might be a fishingboat boy, but she don’t have to smell likeone.” And he was not talking about hiswife when he said, “It makes a man feelgood to take the old girl out when she’started up and looking a picture”.We should all spend time doing touchups and maintenance after each trip. Bytaking a bit of time small problems can beidentified and fixed before they becomea major. Is this lack of pride in shipshusbandry cost driven and the first steptowards complacency?Repairs, preventative maintenance,safety drills and deck skills used to bepart of our training. It was drummed intous so we knew what to do in that momentof panic when things go frightfully wrong,when you don’t have time to think andmust react automatically. Lives are atstake, ours included, and only trainingand good planning can reduce the oddsin our favour.Lookout! is designed to bring youinformation on accidents so that wecan all learn from them and be betterinformed. Call it part of our training andbeing prepared if you like. If you do nothingelse, let the crew read these stories,discuss them and ask “Could this happento us? And if so how would we cope…?”by Keith IngramA deep-sea factory trawler,with a static draft of7.6 metres, grounded whileattempting to berth in an areawhere adjacent shoal groundrequired careful pilotage.Charted depth contours for theapproach to the berth were incorrect.Due to an oversight, a Notice to Mariners,advising of the correct depth contours,had not yet been issued. The skipperand first mate were unaware the charteddepths on their charts were incorrect.The pilot was aware of the changes indepth contours but was unaware that thedetails had not been published.The pilot’s briefing to the skipperand first mate included looking at boththe vessel’s electronic and paper charts.However, the pilot made no remark atthat time about the incorrect charteddepths off the berth.The vessel transited into the innerharbour in accordance with the advice thatwas given by the pilot. The skipper wassteering the vessel throughout this period.Once in the inner harbour, the skipperindicated to the pilot that the first matewould like to manoeuvre the vessel ontothe berth. The pilot agreed and the firstmate took over from the master. At this1. The port’s procedures manual requiredany vessel with a draft greater than 7metres when arriving or departing theberth to manoeuvre in such a manner thatshe did not proceed west of that berthuntil she was at least 0.9 cables (about165 metres) off the wharf. The groundingoccurred about 0.5 cables (90 metres) offthe berth. Neither the skipper nor the firstmate were aware of this procedure.2. The vessel’s chart plotter displayshowed the vessel was approaching thetown wharftrack afterrefloatingpoint, the pilot allegedly told the skipperand the first mate that they were not toproceed past the end of the town wharf,which lay about 150 metres to the westof the westerly extremity of the vessel’sberth, as it got shallower beyond thatpoint. The speed of the vessel at this timewas about 3-4 knots.On approaching the berth the vesselhad to conduct a turn to port of about180 degrees to enable it to berth starboardside to. According to the skipper,the vessel was about 150 metres off thetown wharf and approaching a pointabout 150 metres from the end of theDue to an oversight, a Notice toMariners, advising of the correct depthcontours, had not yet been issued.groundingthe vessel’s actual tracks both before (black) and following (orange) the grounding.westerly extremity of her intended berthand was about 2 cables (370 metres) offthe wharf, when the vessel started to turnto port. The vessel’s advance would havetaken her further to the west during thecourse of the turn and into the area wherethe actual depth of water was under 7metres. At a depth of 7 metres plus 0.9metres for height of tide, the static underkeel clearance of the vessel was only 0.3metres. As a broad rule of thumb a ‘safe’minimum static under keel clearance iswharf, when the pilotsaid that they shouldstart to turn as thewater gets shallowerat that end. The pilotcontended that hegave this advice earlier.The skipper checkedthe echo sounder andnoticed there wasabout 1 metre of waterunder the keel but wasnot too concerned,as the first mate hadalready put on porthelm in accordancewith the pilot’s advice.The pilot, who realised the vessel wasat risk of grounding on the shoal ground,that lay adjacent to the vessel’s berth,decided it was best to continue with theturn as stopping the engine and comingastern would only worsen the situation.When the vessel was about threequarters of the way through the turn toport, the bridge team realised the forwardmomentum of the vessel had stoppedand she was aground.With the use of her main enginesand the assistance of the pilot boat, thevessel was refloated and safely made fastalongside the berth.approach trackView the full report online at:www.maritimenz.govt.nzLookout!Pointsusually taken to be 10% of a vessel’smaximum draft, which in this case wouldhave been 0.76 metres.3. The pilot was the only member of thebridge team who knew the correct depthcontours and the extent to which thebottom shelved off the berth. As such,it was his responsibility to ensure thebridge team was informed and that theturn to port was started in good time toavoid any risk of grounding. The pilot wascensured for his actions. LOOKOUT! JULY <strong>2006</strong>LOOKOUT! JULY <strong>2006</strong>

Delayedreaction togas escapeA shore maintenanceengineer working on a fishingvessel’s refrigeration systemwas overcome by freon gaswhich escaped whilst purgingpressure from the lines.The engineer had worked withoutincident on the lines system over theprevious two days, as part of the generalrepair, cleaning and maintenance processon the vessel. On the day of the accident,the engineer was intending to inspect thethermo expansion valves fitted to the ceilingpipe evaporator coils. The engineerunscrewed the liquid line of the firstvalve and left it to purge off any residualpressure without any difficulty. However,as he started to disconnect the secondline, the valve opened suddenly and blewout under great pressure and landed onthe deck of the fish hold. Some liquid,but mainly refrigerant gas, then started toescape from the line for around 10 to 15seconds. On hearing the noise of the gasescaping, the skipper and crew of thevessel rushed to the fish hold to checkthe source of the noise. At that stagethey were unaware the shore engineerhad been working in the hold. When theysaw the engineer in the fish hold, theskipper called out to check if he was OK,and received a ‘thumb’s up’ signal. Theskipper and crew then left.After the gas had stopped ventingfrom the line, the engineer got down onhis hands and knees to search for themissing valve opening. After he retrievedit and stood up, he suddenly felt verywoozy and disoriented. He tried to makefor the hatch ladder and leave the hold,but collapsed before he could do so.About fifteen minutes later, when theskipper was on the deck of the vessel, heHe tried to makefor the hatch ladderand leave the hold,but collapsed beforehe could do so.heard the sound of groaning coming fromthe bottom of the fish hold. On investigation,the skipper saw the engineer lying onthe deck of the hold with his legs pulledup into his chest. The skipper and one ofthe crew immediately climbed down intothe fish hold and brought the engineerup on deck, put him in the recoveryposition and called an ambulance. Theengineer began vomiting, but after aboutThe vessel.10 minutes in the fresh air, he began tofeel better. He had no memory of whathad happened. He was later dischargedfrom hospital without any ill effects.It was estimated that about 10kg offreon gas had escaped into the fish hold.View the full report online at:www.maritimenz.govt.nzLookout!PointsToo closefor comfort!Two passenger ferriescame within around 0.3nautical miles of eachother in a close quartersencounter during a crewtraining exercise.About three nautical miles from land andheading seaward, the master of the firstferry decided to drill officers and crew onthe use of the emergency steering system.The master, first officer, first engineeringofficer and several deck crew gatheredin the steering compartment, while thethird officer and a deck cadet kept watchon the bridge. Before the drill began,the bridge crew noted the presence ofthe second ferry on a broadly reciprocalcourse about 10 nautical miles off. Thevessels were closing with each other at acombined speed of about 35 knots.The master of the first ferry decidedto conduct the emergency steeringgear drill using the manually operateddirectional control valve, instead of theusual non follow-up switch. Neither themaster, nor any of the crew had practisedthis method on the vessel before.Despite some disquiet from the ferry’sengineer, the master alerted the bridgevia telephone the steering control wasabout to be transferred from the bridgeto the steering gear compartment andthat the vessel would then be turningto starboard. By now the second ferrywas about three nautical miles out andbearing on the port bow. The bridge crewdid not mention this to the master.Once the steering had been transferred,one of the crew, on the instructionsof the master, operated the directionalcontrol valve marked “starboard”. Thebridge crew immediately noted that insteadof the vessel turning to starboard asthey had been told would happen, it hadin fact started to turn to port, and in thedirection of the approaching ferry. Theyinstead of thevessel turning tostarboard as theyhad been told wouldhappen, it had infact started to turnto port, and in thedirection of theapproaching ferry.looked at the rudder angle indicator andnoticed that port helm had been applied.The bridge crew did not immediatelyalert those in the steering compartmentof what was happening assuming theywould soon realise their mistake.The second ferry was now about onemile away and bearing fine on the portbow. As the first ferry was still turning toport, the bridge crew advised the masterthat the rudders had gone to port andemphasised that starboard helm wasneeded. However they still did not mentionthe near approach of the other ferry.The master again called for starboardhelm, and the same valve as beforewas operated but this time with a largeramount of what was wrongly assumed tobe starboard helm. Seeing the rudders goto port again, the bridge crew alerted themaster for the first time of the developingclose quarters situation with the otherferry and asked for the steering controlto be returned to the bridge. The mastercalled for the helm to be set amidships,but was told it had stuck. The first ferrywas by now swinging rapidly to port inthe direction of the second ferry.Realising there was a problem,the master of the second ferry immediatelyput his helm hard to starboard toturn away.After the steering control wasreturned to the bridge, the bridge crewarrested the port swing and brought thevessel back on track. The second ferry,which closed to within approxiamately500 metres of the first ferry, continuedto turn away until well clear.It was later discovered that the firstferry’s port and starboard directionalcontrol valves had been labelled in thereverse direction.View the full report online at:www.maritimenz.govt.nz1. Whilst the employers of the engineerstated they had robust health and safetyprocedures in place for working in isolationin enclosed spaces, the engineer, asa minimum, should have informed thecrew of his intentions so that one of themcould have been standing by in the eventof an emergency. If the skipper had notheard the engineer groaning, the situationcould have been very serious indeed2. Although the fish hold was not in thestrictest sense, an enclosed space, suchas a cargo tank or a double bottom tank,the open hatch cover was not very largeand the following precautions shouldhave been taken:■ Before commencing work on the ship’srefrigeration system, where gas couldpotentially escape, a permit to workshould have been obtained.■ A portable gas detector should havebeen used before starting any work.■ A ready means of communicationshould have been established throughoutthe time the engineer was in thefish hold.■ A safety belt/harness line should havebeen rigged in readiness should anemergency occur.■ A breathing apparatus set should havebeen immediately available for use by arescuer in the event of an emergency.3. When the gas first started to escape,the engineer should have left the hold.Freon gas is heavier than air and thedecision of the engineer to search forthe valve on his hands and knees seriouslyincreased the risk of his exposureto the fumes.4. The skipper and crew member shouldnot have gone into the hold to retrievethe engineer without first checking thatthe hold was gas free or without usingbreathing apparatus sets. By failing to doso they put their own lives at risk.It was later discovered that the ferry’s portand starboard directional control valves hadbeen labelled in the reverse direction.1. No crewmember had experienceusing the manually-operated directionalcontrol valves on the first ferry. The masterdid not carry out a thorough pre-drillbriefing, outlining what to expect and thesafety actions to be taken should theybe required.2. The bridge watch crew did not impressupon the master the pending approachof the second ferry until a close quarterssituation had already developed. Careshould have been taken before commencingthe drill to ensure that no other vesselswere likely to be in the near vicinity.Lookout!Points3. The master who was conducting theemergency drill did not report this incidentto <strong>Maritime</strong> NZ, even though it was clearlyreportable under the provisions of the<strong>Maritime</strong> Transport Act. The master of thesecond ferry later reported the incident. LOOKOUT! JULY <strong>2006</strong>LOOKOUT! JULY <strong>2006</strong>

Fire! But nofixed meansto fight it!He aimed a 9kg CO 2cylinder through thehatch opening but thishad no effect on extinguishingthe fire.A 15 metre long-line tunavessel caught fire95 nautical miles off land.The skipper and two crew were settingup their gear on the fishing grounds whenlight grey smoke was seen coming frombehind the wheelhouse.The skipper immediately reducedspeed and took the main engine out ofgear. Opening the engine room accesshatch from the saloon, he saw flamesand greyish back smoke coming fromthe port side of the engine compartmentat deckhead level. He aimed a 9kg CO 2cylinder through the hatch opening butthis had no effect on extinguishing the fire.The skipper began emergency procedures,alerting the crew to the locationof the fire and calling for the liferaft to bemoved to the after deck, and the tender tobe launched in case it became necessaryto abandon ship. The skipper attemptedleft: The abandoned vessel with fire visiblein the accommodation (circled).to extinguish the fire a second time bytying down the trigger of a 9kg foamextinguisher and throwing this through theengine room hatch in the general directionof where he thought the fire had startedand then closing the hatch again.The skipper then closed all ventilatorsand dogs for the engine roomair intake and exhaust, and shut off thefuel tanks, which combined, containedabout 7 200 litres of marine diesel oil.He returned to the wheelhouse andre-opened the engine hatch but saw theflames had not diminished and closed thehatch again. Meanwhile the crew gatheredsurvival equipment and prepared tolaunch the liferaft.The skipper managed to make threeMayday calls on 2182 MHz and 4125 MHzvia a single sideband radio and to activatethe 406 MHz EPIRB before abandoningship and later an additional 121.5 MHzEPIRB that was kept in the liferaft. Hiscalls were answered by <strong>Maritime</strong> NZ’s<strong>Maritime</strong> Operations Centre.The skipper tried several times toestablish whether the fire was intensifyingor diminishing before being forced toabandon the vessel due to toxic smokeand flames. The steel wheelhouse wasglowing red from the heat and flamescould be seen reaching about 1-2 metresabove the wheelhouse, whose windowswere heard exploding. Once in the liferaftthe skipper fired a distress rocket. By thistime, daylight was fading.The trio watched the vessel burn fromthe liferaft over the following five hoursbefore being located by an RNZAF Orionsearch aircraft and later rescued by arescue helicopter.When salvage vessels arrived at the lastknown position, there was no trace of thevessel, aside from its long-line equipment.View the full report online at:www.maritimenz.govt.nzLookout!Points1. As the wreck of the vessel could not betraced and the crew were unable to accessthe engine room, it was not possibleto determine either the cause of the fire orhow the vessel sank. Intense heat in theengine room would have distorted metaland possibly broken welds. The rupturingand explosion of the two fuel tanks cannotbe discounted with diesel oil havinga flashpoint of 65 degrees centigrade. Allskin fittings in the vessel were metallicand solid steel watertight doors separatedthe engine room from the rest of thevessel. The only access to the engineroom was through the hatch located in thesaloon. The last photographs that weretaken of the vessel by the Orion aircraftshowed substantial fire damage to thewheelhouse with smoke coming from theforward engine compartment vents butwith no visible damage in way of the afterfish hold. There was no obvious list or trimon the vessel, which was still riding highin the water when it was last observed.2. Under <strong>Maritime</strong> Rules, the vessel,being under 24 metres in length, was notrequired to have either a fire detectionsystem or a fixed fire fighting system inthe engine room. An amendment to theRules is currently under considerationby <strong>Maritime</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>. A fixed firedetection system or a remote powerdriven emergency fire pump would probablyhave saved this vessel. Fire pumpsshould be installed away from machineryspaces and be capable of being drivenindependently of the vessel’s main andauxiliary machinery.3. Throwing fire extinguishers into burningengine rooms is not recommended.Foam has to be aimed at the base of afire to be effective and a foam cylindermust be held upright to operate fully. Afoam extinguisher that has not been fullydischarged has the potential to explodeor rupture.4. The vessel was equipped with atwo-inch fire pump (even though this wasnot required by <strong>Maritime</strong> Rules), but thiswas operated off the main engine andwas rendered inoperable when the mainengine stopped.5. The skipper said he had a robusthazard identification system on boardand conducted drills, including fire drills,every 14 days.6. Given the prevailing calm conditions,it is likely that water initially entered thevessel below the waterline making thevessel sit lower in the water. Entrancesto the accommodation and fish hold thatwere left open would have contributed tothe loss once the deck edge had becomeimmersed. If flooding had been restrictedto the engine room, the vessel wouldprobably have had sufficient reservebuoyancy to remain afloat. LOOKOUT! JULY <strong>2006</strong>LOOKOUT! JULY <strong>2006</strong>

Throttlefailure offthe rocks TheA harbour cruise vesselwith 31 passengers on boardwas manoeuvring just50 metres from shore whenthe throttle failed.As the skipper put both enginesastern to allow passengers to get abetter view of some seals, only the portengine responded. The starboard enginecontinued to idle ahead. When the skipperre-engaged the starboard engine toastern, the vessel leapt forward with fullahead power on the starboard engine. Asthe skipper tried unsuccessfully to turnthe vessel away from the shore using fullport throttle, it impacted on a rock ledge.1. The control Morse cables werereplaced with a more robust cable.Emergency stop buttons were alsoinstalled on each bridge wing.The skipper hit the emergency stop onthe starboard engine and moved thebow off the rock using the port engine.As he did so, the vessel’s stern quartersmacked onto the rocks.Aided by a light breeze and theswell, the skipper freed the vessel andpositioned it in clear water. The voidspaces were inspected, and no waterwas found. Throughout the slow tripback to port, the skipper repeatedlychecked the vessel to ensure it wasnot taking on water.The passengers were shaken, butthere were no serious injuries and nonewere admitted to hospital.On investigation, metallurgists found2. It is possible to reduce stress on gearcable by supporting it horizontally forabout 100 to 150 mm from the actuatorbox cable fastening. Securely clampingMorse cables at least 100 mm past theWhen the skipperre-engaged thestarboard engine toastern, the vesselleapt forward withfull ahead powertop left: the vessel. above: the Damaged starboard propeller.the throttle failure was due to a brokengear-select Morse cable. It had brokendue to metal fatigue caused by cyclicunidirectional bending when the gearwas operated.The vessel sustained damage tothe starboard hull, the starboard propellerand shaft.View the full report online at:www.maritimenz.govt.nzLookout!Pointsfastening will ensure the filament doesnot rub against the outer sheath andwill minimise metal fatigue. The vessel’sowner installed a system after the accidentto reduce unidirectional bending.Simplewatertightcommunicationscan save livesA cellphone may have saved the life of arecreational boatie who died after a lateafternoon fishing jaunt, but only if it wassealed in a plastic bag. The boatie andthe skipper of a small aluminium dinghyhad left a cellphone in their car at theboat ramp.When the pair was about one milefrom shore, travelling at approximately15 knots, the skipper let go of theoutboard motor tiller to stop his hat fromblowing off in the wind. At this point thedinghy went into a tight spin, partiallyswamping it, which resulted in the dinghycapsizing before the men had a chanceto bail it out. Neither man had been wearinga life jacket, but both managed toput these on after being thrown into thewater. They then made several attemptsto right the upturned dinghy, but it provedtoo unstable with the stern held down bythe weight of the outboard motor.With night approaching, the tidecarrying them further from land and noother boats in sight, the pair decided toswim for shore.The men saw some fishing buoys thatwere significantly closer than the shore1. The area where the men were fishinghad both VHF radio and cellphone coverage.A water-resistant, hand-held VHFradio costs under $200 and will not onlyalert <strong>Maritime</strong> Radio right around the NZcoast, but can also summon help fromother vessels within at least a four-mileradius. A cellphone in a sealed plasticbag can be used effectively with no lossThe dinghy.and decided to make for them. Althoughboth were good swimmers, the tide wasagainst them and they were unable toreach the buoys. After an hour, one manbecame exhausted.skipper then faced the agonisingchoice of staying with his exhausted friendor pressing on for shore and help.The skipper then faced the agonisingchoice of staying with his exhaustedfriend or pressing on for shore and help.For two hours, the skipper attemptedto tow his friend, but finally made thedecision to swim on alone. It took him afurther two hours to reach the shore andraise the alarm at a local farm house.Just over an hour later, the rescuehelicopter sighted the upturned dinghy.of reception quality.2. The area was visible from shore byseveral houses and a road. A red, handheldflare may well have been seen.3. A personal locator beacon would alsohave raised the alarm.4. Capsizes are not uncommon in smallboats. Boaties need to be prepared andhave an action plan to cope with anyThe missing man was found minuteslater by the Coastguard in a very seriouscondition. He was pronounced deadshortly after reaching shore.The following information is availableonline at www.maritimenz.govt.nzor by phoning 0508 22 55 22:<strong>Maritime</strong> Rule Part 91.4 – NavigationSafety Rules: Personal Floatation DevicesSafe Boating An Essential Guidepublished by <strong>Maritime</strong> NZ, Coastguardand Water Safety NZTips About Boating Safety stickerproduced by <strong>Maritime</strong> NZView the full report online at:www.maritimenz.govt.nzan example of A waterproof bagthat can be used for a cellphone.these are readily available frommost ship chandlers.Lookout!Pointsemergency. As both men had life jacketsand were sound swimmers, a meansof being able to communicate withsomeone ashore would almost certainlyhave prevented this accident leadingto a fatality.5. If the boat had not been equippedwith life jackets, it is probable that twolives would have been lost.10 LOOKOUT! JULY <strong>2006</strong>LOOKOUT! JULY <strong>2006</strong> 11

In harms wayWhen a chemical tanker’s shore mooringline parted suddenly, recoiling into ashore hammerman on board the vesselkilling him instantly, <strong>Maritime</strong> NZ Investigatorsfound that half the senhouse slipshad not been crack or load tested byoff-site professionals.The fatality occurred when the tanker,with a deadweight of 9 000 tonnes, was beingmade fast starboard side to a harbourwharf under the advice of a local pilot.Due to swell conditions, shore-mooringlines, in addition to the ship’s lines,were used to secure the vessel. The ship’sbow thruster and a harbour tug were alsoused to assist in berthing the vessel.When the pilot was told that the vesselhad been secured forward following ashore mooring gang going onboard, heinstructed the tug master to push the shipastern so that the after shore mooringscould be tensioned before making fast. Thetug master angled his tug to the port sideof the vessel using 90% of ahead thrust. Atthe same time, a shore loader was used tohaul in the slack lanyard that was attachedto the after shore mooring line.A maximum swell surge of 0.5 metrewas recorded on the harbour tidal gaugewhilst the vessel was being made fast.The effect of these combined forceson the forward shore mooring line causedthe senhouse slip to fracture. The suddenrelease of tension then caused the shoremooring to recoil striking the hammermanas he was tidying up the rope tails onthe forecastle head. The hammerman’semployer did not have adequate healthand safety procedures in place. Had therebeen, he would have been standing clearat this time.Instead, the hammerman suffered afractured left arm, massive head injuriesand was killed instantly.Metallurgic analysis showed thesenhouse slip had failed catastrophicallyin a brittle manner because it had beenA sudden release of tension then causedthe shore mooring to recoil striking thehammerman as he was tidying up the ropetails on the forecastle head.1. There was no requirement for hammermento wear hard hats on board a vessel.2. Approximately, half the senhouse slipsused in the port were identifiable and haddocumentation confirming they had beencrack tested and in some cases, loadtested by off-site professional testers. Theother half, including the senhouse slipthat failed, had no such identification ordocumentation of crack and load testing.3. The failure of a senhouse slip hadnot been identified as a hazard by theemployers of the hammerman, Also, theemployers did not have any proceduresor policy regarding the regular testing andmaintenance of senhouse slips. Both ofpennant wire to shoresenhouse slipTypical senhouse slip arrangements used on the tanker.The shore mooring line was made fast, without incident,using a senhouse slip connecting the pennant wire of theshore mooring line to a wire strop that was made fast to theset of bitts. In the event of a sudden emergency, requiringthe vessel to leave the port quickly, the shore mooring linecould be let go without having to fully slacken the line byhammering clear the slip ring of the senhouse slip.these were in breach of the requirementsof the Health and Safety in EmplomentAct 1992.4. Actions taken by the employers afterthe accident included the following:■ Hammermen to stand clear beforehauling begins on moorings at theother end of a vessel.■ A minimum of two shore mooring linesat each end should be used for thosevessels requiring such moorings.■ When a tug is being used to push avessel, two mooring lines should bemade fast at one end of the vesselbefore the shifting begins. The hammermanto stand clear at this time.wire to bittsangle of pulland impact areaLooking over bitts towards Panama Lead.manufactured using material that was notfit for purpose. Further, the design specificationswere inappropriate for the potentialforces such a device might experience.The following information is availableonline at www.maritimenz.govt.nzor by phoning 0508 22 52 22:Section 6, 7 – Health & Safety inEmployment Act 1992View the full report online at:www.maritimenz.govt.nzLookout!Points■ Clearing up tails should be left until avessel is fully secured.■ Loading and destruction testing of allsenhouse slips and mooring lines.■ All unmarked senhouse slips removedfrom the wharves to be marked and setaside for testing.<strong>Maritime</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> prosecutedthe employers of the hammerman forbreaches under section 6/50(1) of theHealth and Safety in Employment Act.The employers pleaded guilty to thecharge and were fined $15 000 andordered to pay reparation of $50 000which was to be paid into a trust fundfor the deceased’s daughter.Booze + Boat+ Bad weather= DeathAn engineer is presumeddrowned after a failed leapfrom a dinghy to the side‘sea door’ of a fishing vesselanchored in an exposed inlet.The engineer and skipper of thefishing vessel had gone ashore early inthe morning and spent the day in portvisiting friends and drinking at the localpub. Three other crewmembers witheither little or no understanding of Englishremained on board for the day, keepingan anchor watch and processing fish.Later that evening, the skipper andengineer returned to the vessel in anoar-propelled dinghy despite choppyseas and increasing winds of about 30knots. The sea temperature was about10 degrees and neither man wore alife jacket or had any means of communicationin the event of an emergency.Both had been drinking heavily. As thepair in the dinghy neared the fishingvessel, the engineer ignored the skipper’searlier instructions to remain seated untilthe dinghy was fully alongside, and leaptfor the fishing vessel’s open sea door,1. Having spent the day drinking and ona dark night, with the wind increasing,the skipper and engineer should not haveattempted to return to the vessel in asmall dinghy, particularly as there were nolife jackets or means of communicationon board. As skipper, it was his duty toensure the safety of all his crew.2. A life jacket and a ready means ofcommunication to raise the alarm mayhave saved the engineer’s life.3. Alcohol, even in small quantities,the bottom of which was about 1 metreabove the sea. He missed, but managedto cling briefly to the bulwark at theafter end of the open sea door, beforetumbling into the sea and drifting asternof the vessel.In leaping across to the fishing vessel,the engineer had forced the dinghy awayfrom the vessel’s side. With the increasedfreeboard of the dinghy and with only oneoar at the ready, the dinghy drifted evenfurther astern of the fishing vessel thanthe engineer who was calling out for help.Hearing shouts, the crew on the vesselwho had been keeping watch in thethe engineer ignored the skipper’searlier instructions to remain seated untilthe dinghy was fully alongside, and leaptfor the fishing vessel’s open sea doorwheelhouse, twice threw a lifebuoy in thedirection of the engineer. On the secondoccasion, the lifebuoy landed within armsreach of the engineer, but he made noattempt to grab it. The crew last saw theengineer drifting into the night, face downin the water and not moving.The skipper tried in vain to row againstthe wind and seas towards the engineer,but became exhausted. He was eventuallyblown onto the far rocky shore and wherehe finally managed to raise the alarm.affects judgement and exaggeratesself-confidence. Alcohol can also reducethe ability to sense direction and cancause unsteadiness, which in a smallboat at night is courting disaster. It alsodramatically decreases the body’s abilityto handle cold. The onset of hypothermiacan occur up to 50% earlier in a personwho has consumed alcohol.4. The crew of the fishing vessel didnot have sufficient knowledge of Englishto be able to raise the alarm by radio.Above: The photo shows the Open sea door the engineer attempted to enter.below: The dinghy that the engineer leaped from.The following information is availableonline at www.maritimenz.govt.nzor by phoning 0508 22 52 22:<strong>Maritime</strong> Transport Act 1994– Section 19 – Skipper’s DutiesView the full report online at:www.maritimenz.govt.nzLookout!PointsAll crew should be conversant in theworking language of a vessel. It is difficultfor skippers to conduct proper safetyfamiliarisation and induction training ifcrew cannot understand instructions.5. The skipper should never have leftthe anchored vessel in an exposedinlet, where bad weather was knownto regularly occur, and in the hands ofcrew who could not raise the alarm oroperate the main engine in the event ofan emergency.12 LOOKOUT! JULY <strong>2006</strong>LOOKOUT! JULY <strong>2006</strong> 13

Don’t take chanceswhen kayaking!Gas detectors canprevent explosionsA tourist drowned after hisopen cockpit kayak capsizedon a high-flowing river.Although he (kayaker 1) was kayakingwhat was normally a class I to II (easyto moderate) river with a very experiencedfemale companion (kayaker2), the pair had several times that dayconsidered abandoning the trip due tohigh water flow.They had borrowed two kayaks fromthe owners of holiday accommodationwhere they were staying, and had alsoconsulted several local people as to thenature and flow of the river before settingout. The owners had recommended thatthey stay on the lake and not to go onthe river, as the water could be very swift.At the time of the accident the river flowwas 650 cubic metres (650 000 litres)per second.The pair had been able to borrow onlyone life jacket and kayaker 2 wore this,as she was the only one who fitted it.They had tied a plastic/vinyl buoy to eachkayak, using approximately 16 metres oforange plastic rope. The purpose of thiswas that should one of them capsize, theother could throw their buoy to assist theswimmer in the water.As they approached a notorious spoton the river, about which they had beenwarned, kayaker 1 paddled across to aneddy on one side of the river to assesswhat lay ahead. The high river level meant1. Although a life jacket may not haveprevented this death, it is not wise tokayak without one. Particularly when theriver flow is swift and there are heavilywooded sides, as this removes the optionof a swimmer floating in the middle ofthe river and waiting for an unwoodedsection of a bank to swim ashore.2. The kayaker who died had littleexperience, and neither kayaker hadany previous experience of the riverconcerned. The water of the lake-fedriver would have been clear at all times,so it would not have been immediatelyobvious that it was in very high flow toKayaker 2’s kayak.a lot of water was flowing through thetrees on the riverbank. Kayaker 2 paddledinto some slow moving current belowkayaker 1’s eddy. In order to steady thekayak, kayaker 2 grabbed hold of sometrees and in doing so capsized and fellout of the kayak. She was quickly sweptdownstream. Kayaker 1 threw her theplastic/vinyl buoy that was attached tohis kayak, and in doing so also capsized.Kayaker 2 was swept by the weightof water into a rata tree protruding fromthe bank. She managed to free herselffrom the rope that was attached to herkayak, resurface and climb onto the tree.She saw both kayaks trapped on thebranches of the rata tree but could notsee kayaker 1. She then struggled uponto the riverbank, and ran downstreamsearching unsuccessfully for kayaker 1.She met a tourist who called 111,and both women then returned to theaccident site. Returning to the tree shehad been caught on, kayaker 2 saw thethe pair had several times that day consideredabandoning the trip due to high water flow.someone who did not know it well.3. The pair did seek out informationabout the river, but none of it was goodquality advice that related specificallyto kayaking.4. Both kayakers struggled with theropes they had tied on as rescue lines.Rope and rivers are a potentially dangerousmix. Although throw bags can beuseful in rescuing people and equipmenton a river, they should not be carriedwithout a knife to allow them to be cutaway if necessary.5. The open cockpit kayaks that wereused on this trip have wide flat hulls thatcoat jacket kayaker 1 had been wearingsubmerged beneath the branches of thetree. She managed to venture along oneof the branches far enough to be able topoke the jacket with her foot. It was atthis stage she realised her companionwas still in the jacket and that he wastrapped under the water.Due to the fast flowing water, andthe flimsy structure of the tree, it was notpossible to retrieve the body of kayaker 1.His body was later recovered with thethe rata tree (Note Kayaker 2’s kayak still pinned).assistance of a jet boat. The rescue ropethat had been attached to the kayak wasfound around his neck. The driver of thejet boat estimated the rate of the riverflow at this time to be about 25-30 knots.View the full report online at:www.maritimenz.govt.nzLookout!Pointsare most ideally suited for family fun oncalm water.6. There was no neoprene cockpit cover(spray skirt) on either of the two kayaks.These are worn by the paddler and aresecured around the rim of the cockpit tokeep out any water.7. <strong>Maritime</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> has recommendedthat managers of all Departmentof Conservation visitor centres seek inputfrom local kayaking experts to formulateguidelines to help staff give appropriateadvice regarding kayaking local rivers.A recreational skipper washospitalised for six weekswith severe burns afterthe stove on his 8.4 metrefibreglass yacht exploded.On the day of the accident, theskipper had replaced a gas bottle and itsregulator after noticing on an earlier tripthat the stove was not working properly.The skipper soap-tested the regulatorsuccessfully and found the pressure wasnow working well, with no apparent gasleaks. He ignited the two burner stoveand then turned off one of the burners,leaving the other running to further testthe gas pressure and then busied himselfin the saloon. Minutes later, there was aloud explosion in the starboard quarterberth next to the stove. The skipper burstout of the quarter berth with seriousburns over his lower body. Realising theyacht was on fire, the skipper, quicklyreturned and attempted to fight the fireMinutes later, therewas a loud explosionin the starboardquarter berth nextto the stove.with the help of other people nearby. Onlythen did the skipper realise the extent ofhis injuries and an ambulance was called.Accident investigators found thePVC constructed gas line between thegas bottle, located in the aft cockpitlocker and the stove in the quarter berthwas perforated with what appeared to bea number of drill holes. These drill holeswere considered to be the cause of theFire Damage to Topsides.initial poor performance that theskipper had tried to rectify by replacingthe gas regulator.Before the accident, when the skipperwas overseas, engineers had replacedthe yacht’s motor and installed a newelectric loom. This had required a numberof holes to be drilled in the yacht’s internalbulkheads. The run of the loom cablingwas next to the gas line and several drillholes in the bulkheads were found tobe near to the perforations in the gasline. The skipper had not conducted anydrilling during his ownership of the yacht.Damage to the yacht was extensive,both structurally from the force of the1. The yacht’s gas line had not beentested and there was no gas detectoron board, in breach of the Yachting<strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> Safety Regulations. Pressuretesting would certainly have exposedthe leak and may have preventedthe accident.2. LPG is heavier than air and will settlein lower areas of a vessel. In concentrationsof one part per 70 to air, it willexplode when ignited. A gas detectorwith a remote sensor unit is inexpensive,and can automatically shut off any electricallyoperated gas solenoid valve.3. The use of Poly Vinyl Chloride(PVC) for the gas line is a breach of<strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> Standards. Plastic hardenswith time and can crack and in this caseexplosion and due to the severe effectsof the fire. The yacht, which was insuredfor $47,000, was declared a constructivetotal loss.The skipper suffered extensive burnsto 25% of his body. Most of the burnswere to his legs, but his arms and facewere also affected. He has undergoneseveral skin graft operations and continuesto suffer pain from his injuries.View the full report online at:www.maritimenz.govt.nzLookout!Pointsbe inadvertently perforated.4. It is common for gas explosion victimsto not immediately realise the extent oftheir injuries. It is crucial that burns beimmersed in water immediately to preventdeep tissue damage.14 LOOKOUT! JULY <strong>2006</strong>LOOKOUT! JULY <strong>2006</strong> 15

Five thrownfrom raftA man drowned pinned toa rock by river rapids afterbeing thrown from a whitewater raft.Training matters!A 40 metre passengervessel with 60 passengerson board grounded againstrocks whilst its master wasbusy in the tank room.The vessel had spent the previoustwo hours cruising the area, visitingvarious wildlife hotspots along its route.As the cruise neared completion, themaster set the vessel on a straight courseat about 8 knots and handed controlover to a less experienced crewmemberto give her some steering time. As heleft the wheelhouse, the master toldthe crewmember to head for home,and asked the chef who was also in thewheelhouse to keep an eye on things.The vessel was about 150 to 200 metresfrom the shore.After the master left, the crewmemberthat had control heard the nature guideannounce over the public addresssystem that penguins had been spottedin the water. Hoping to assist withsight-seeing, the crewmember claimsshe pulled the ship’s controls to neutral.Immediately, both engines stopped andThe vessel hit therocks at about 4knots, rearing upbefore settling downon an even keel.the stall alarms sounded. The chef triedto restart both engines, failing on twoseparate attempts. The master returnedto the wheelhouse and made three failedattempts to restart the engines.The wind was by now pushing theabove: The vessel.vessel toward the rock shore. The mastersuccessfully started both engines usingthe over-ride start-up system, but whenhe activated the levers to full astern, therewas no response.The vessel hit the rocks at about4 knots, rearing up before settling downon an even keel. The master managedto shut down both engines and restartthem, engaging in idle ahead to holdthe vessel in place while it was checkedfor damage. Fortunately, no water wastaken on board and there were noinjuries. The vessel was backed off therocks and returned to its berth.View the full report online at:www.maritimenz.govt.nzThe man was one of several colleaguesspending the afternoon whitewater rafting as part of a leadershipcourse. Four rafts, each containing sixor seven passengers, were rafting theriver in convoy. The river rapids rangedfrom grade one (easy) to grade five(very difficult).About two hours into the trip, theconvoy reached the last grade 4/5 rapidof the journey and slowed above it toassess the river conditions. The lead raftguide gave the passengers a briefingon what to expect and reminded themThe guide wasyelling to paddleharder, but couldsee the raft did nothave enough forwardspeed to get past arock positioned atthe top of the rapid.how to avoid a ‘wrap’ situation – wherethe upstream side of the pontoon goesunderwater and the raft rides up and ispinned against a rock.The crew on board the first raft set offtoward the rapid paddling hard to get intothe right area of water flow. The guidewas yelling to paddle harder, but couldsee the raft did not have enough forwardspeed to get past a rock positioned at thetop of the rapid. He called for the crew tomove to the side of the raft that was closestto the rock to prevent the raft fromriding up the rock. As the crew startedto follow the instruction the raft struckthe rock. Water came over the pontoonand the raft began to slide up the rockand became wrapped. Five of the sixpassengers were swept into the rapid.The guide and remaining passengermanaged to free the raft and beach it at adownstream eddy. From there they couldsee four of the spilled out passengers,but one remained unaccounted for.The remaining three rafts camethrough the rapid and were told via raftingEntrapment point hereWrap RockSwimmer routesign language that one passenger hadbeen lost. Sign language is a usual formof communication among river guides andis useful for overcoming the problems oflong distances and roaring river sounds.Various search attempts to locate themissing passenger failed. His body waslater found pinned by the flow of waterunderneath a large rock downstream ofthe accident site.View the full report online at:www.maritimenz.govt.nzLookout!Points1. It is likely that the crewmember movedthe vessel’s controls into astern, ratherthan neutral. Procedures should requirea well-trained and experienced personto be on board whenever staff trainingis underway, in addition to the master orperson who has control of the vessel, incase they are unexpectedly called away.2. This vessel’s main start-up procedurewas overly complicated. Neither themaster, nor the chef could re-start theengines in time to prevent the grounding.3. A bridge needs to be well managedat all times. In this instance, themaster handed over to an inexperiencedcrewmember who was to be supervisedLookout!Pointsby the chef (who happened to be onthe bridge during his break). The masterneeded to formalise this hand over sothat all crew knew what they were doingand what responsibilities they had. Thechef should not have accepted thecommand to keep an eye on things in thewheelhouse so casually.1. Although sign language use is commonin rafting, it created some confusionamong the guides as to whether or notall the passengers were safe. Althoughtwo of the guides carried repeater radios,these were not used as primary communication.Had each guide carried eithera repeater radio, or a small line-of-siteradio, confusion may have been lessened.2. River signals can sometimes bedifficult to interpret. It is important to replyto each signal with the same signal in thisway ensuring more accurate interpretationof communication between guides. Theprincipal of returning the same signaldoes not apply to the use of the ‘OK’signal if the situation is clearly not OK.3. The accident occurred toward the endof a two-hour rafting trip that includedseveral grade 4/5 rapids. Guides shouldremember that passengers can becomefatigued on demanding raft trips. Guidesmust stay focused because the river tripis not finished until all rafts are at thetakeout point.4. The flow of the river at the time ofthe accident was over 40 000 litres ofwater per second.16 LOOKOUT! JULY <strong>2006</strong>LOOKOUT! JULY <strong>2006</strong> 17

Inadequatefuel tankmountingcauses fireabove: Aft section of engine room bay.right: The vessel.A skipper died after hisfibre-glass launch collidedwith a passenger ferry at night.Visibility was poor with low overcastcloud and rain at the time of the accident.As the two vessels approached eachother in a nearly head-on situation, aseries of misunderstandings on bothvessels developed.The ferry master, who first observedthe launch ahead at a significantdistance, saw her red sidelight, andoccasionally both her green and redsidelights but felt the launch would passclear down the ferry’s port side. However,upon realising the launch was going to1. The Collision Rules make it clear thatin a head-on or nearly head-on situation,each vessel must alter course tostarboard so that each shall pass on theport side of the other. This tragedy wouldhave been avoided if the launch skipperhad stuck to this most basic requirement.The local bylaws also required the launchskipper to keep out of the way of the ferry.2. The launch skipper should have usedpass too close to his vessel, the mastersounded five short and rapid warningblasts on the ship’s whistle, and alteredcourse slightly to starboard.The launch skipper, navigating by eye,mistakenly believed the ferry had turnedto port towards the launch. Suddenlyrealising the danger, and about one minutefrom impact, the skipper turned to portto try and avoid the ferry. Tragically, thiscourse put him directly in the ferry’s path.Upon seeing the launch’s alteration ofcourse to port the ferry master put bothmain engines full astern and the rudderhard to starboard, sounding the ship’swhistle continuously.When the two vessels collided, theevery available tool to assist with hislookout. Navigating by eye at night is notoriouslyinaccurate. Although not fitted,radar would have assisted the skipper tomonitor his position in relation to knownferry tracks. The launch was fitted witha GPS plotter, however it did not haveelectronic charts for the accident area.3. Fibreglass is a poor radar reflector.Such vessels transiting areas that areWhen the twovessels collided, thelaunch capsized andwas cut in two by thebow of the ferry.Head On?Turn to starboard!launch capsized and was cut in two bythe bow of the ferry.The crewmember who was on thelaunch at the time of the collision wasable to swim out of the fore end windowof the upturned and flooded cabin. Shewas rescued by a lifeboat deployedfrom the ferry. The skipper’s body wasrecovered about 40 minutes later.The ferry was eventually stopped justshort of the land that had been on itsstarboard side before the collision.View the full report online at:www.maritimenz.govt.nzLookout!Pointsfrequently used by large vessels wouldincrease their visibility by fitting passiveradar reflectors.4. Although recreational vessels are notrequired to carry VHF radio. This wouldhave proven a simple and effective wayfor the ferry master to establish communicationswith the launch and to resolvethe developing problem.An incorrectly installed fueltank caused a fire thatseriously damaged a 9.5 metrealuminium rescue vessel.The skipper and four crew wereresponding at speed to an incident whenthey smelled diesel. Looking astern, theysaw oil on the water and thick smokecoming from the engine bay vents. Theydecided, rightly, not to open the cover boxto the engine bay, to prevent more oxygenfeeding the fire. Attempts to control thefire by shutting off the fuel supply werethwarted by the presence of thick smoke.After issuing a Mayday call on channel16 and advising <strong>Maritime</strong> NZ’s <strong>Maritime</strong>Operations Centre of the situation, theskipper ordered the crew to abandon the1. The failure to comply with design andconstruction specifications was due tothe tight fit of the fuel tank in the well.This meant that there was inadequateroom to allow for the specified mountingsystem to be utilised and as a result analternate system was installed.2. The vessel was fitted with anautomatic bilge alarm that was audibleat the steering position on the vessel.However, the crew did not hear the alarmsound. The skipper believed this couldhave been due to the float switch beinglocated in the forward section of theengine bay bilge and not activating, asthe vessel was on the plane and trimmedby the stern with the spilled fuel accumulatingin the aft section of the bilge.3. There is no requirement under<strong>Maritime</strong> Rules for vessels of this size tobe fitted with a fixed fire fighting systemin the machinery space. The crew werevessel to avoid further exposure to thetoxic smoke. Two recreational vesselsthat had responded to the vessel’sMayday subsequently rescued the crewfrom the water.An hour later, the fire was extinguishedby the Fire Service and otherrescue vessels, and the fire damagedvessel was towed back to port and liftedout of the water.On inspection, it was found that thewelding of the four aluminium anglebrackets – measuring 6mm in thicknessand 47mm in width – that were designedto hold the 450 litre diesel fuel tank firmlyin position to the hull, was substandardwith inadequate penetration and fusion.Moreover, the fuel tank was securedcontrary to design and constructionThe spilled diesel was then sprayedover the hot turbo charger of the engineunable to direct the vessel’s portablefire extinguishers onto the fire due to theextent of the thick acrid smoke.4. Different fire fighting systems areavailable to small vessel operators thatcan be installed in engine bays to providea flood type system. These include:■ FM 200 systems that operate by cableor automatic sprinkler systems thatrespond to high temperature levelsCO 2 systems with self latching handlesattached to copper or steel tubing thatlead into an engine space. Powder extinguisherswith swage lock connectionsthrough bulkheads or engine box coversthat enable the nozzle of an extinguisherto lock into a quick release connector.■ <strong>Maritime</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> has been askedto give consideration to a Rule amendmentrequiring vessels of less than 15metres in length to be installed witha fixed fire fighting system or one ofspecifications. As a result, the fuel tankhad moved by about 50mm from itsoriginal welded position whilst the vesselwas operating at speed. This shift in theposition of the fuel tank caused the fuelfiller line to disconnect which resulted inabout 250 litres of diesel spilling into thebilge of the engine bay.The spilled diesel was then sprayedover the hot turbo charger of the engineby the action of the turning propellershaft, resulting in ignition and fire.The vessel was substantially damagedbut was able to return to serviceonce a new engine had been installedand repairs carried out.View the full report online at:www.maritimenz.govt.nzLookout!Pointsthe above systems, or the carriage ofa remote (from the machinery space)power driven emergency fire pump.5. Fuel that is sprayed onto the hotspots of an engine by a rotating propellershaft, including a turbo charger, is of adensity that is particularly susceptible toignition. Many fires on smaller vesselshave been caused in this manner andare often exacerbated by the difficultiesin accessing the fire directly due to thepresence of smoke, heat, toxic fumesand limited physical access.6. It is essential that fuel tanks areadequately secured as loose or rupturedfuel tanks pose a serious threat to thesafety of a vessel and its crew. In highspeed vessels, such as in this case, thehydraulic pressure created by free surfaceeffects in fuel tanks, even when they arebaffled, can exert considerable force onsystems used to secure such tanks.18 LOOKOUT! JULY <strong>2006</strong>LOOKOUT! JULY <strong>2006</strong> 19

Fatigue, thecreeping dangerAn 11 metre fibreglass crayfishing vessel broke upon rocks after groundingwhile its two crew slept.The experienced skipper and crew hadleft port in the early hours of the morningin order to arrive at the fishing groundsby sunrise. After clearing the harbourentrance, the skipper handed over thewatch to one of the crew. The othercrewmember had already gone to bed.The skipper then went below for aboutan hour and slept for what he believed tobe about 15 minutes before being wokenby the crewmember and returning to thewheelhouse. After taking over the watch,the crewmember went below to sleep.The skipper was navigating by chartplotter and radar. He was monitoring thevessel’s position in relation to the landand making course adjustments in order1. The skipper had managed to get about4½ hours’ sleep in preparation for thetrip, as well as a short nap in the earlystages of the trip, while another crewmember kept watch. Naps can providea good defence for a while against goingto sleep on watch. However, at least sixhours uninterrupted sleep in one stretchis a recommended minimum beforestarting work and with a 7-8 hour stretchbeing ideal.2. The skipper said that he felt fine onthe morning of the accident and didnot feel sleepy. He had not consumedany alcohol and had had a good dinnerthe night before. He was not taking anyto cut in close with the land and lessenthe adverse effects of the tidal streamon the vessel’s speed. The helm was inautopilot. No waypoints or alarms wereset on the GPS, no guard zones were seton the radar to warn if another vessel orthe land was coming too close to the vesseland the echo sounder was switchedoff. The vessel was not equipped with awatch-keeping alarm.After setting a course and followingthe coastline, the skipper sat on thebench seat in the wheelhouse to keepwatch. The visibility was good with alight westerly wind and a swell of about1 metre. The skipper stated that he feltrelaxed and that it was good to have‘decent’ weather conditions. He saw theecho of an island, on which the vessellater grounded, that was showing threemiles ahead on the radar screen.The next thing the skipper rememberedwas being woken suddenly bythe sound of the vessel grounding. Theskipper checked the GPS, which showedthe vessel had hit the island. Donninglife jackets, the awakened crew checkedthe vessel, but found no initial hulldamage. The skipper tried to manoeuvreThe next thing the skipper rememberedwas being woken suddenly by the soundof the vessel grounding.astern off the rocks but to no avail as thevessel was hard aground. It was takinga pounding from the swell and beinglifted further up onto the rocks. About 30minutes after grounding, cracks beganappearing in the hull, and the crew wereunable to stem the flooding.medication that might affect his sleep.3. People are more susceptible tofatigue at night and particularly in theearly hours of the morning, which is whenthis accident occurred. Peak alertnessoccurs near midday, when the bodytemperature is at its highest, whereas theearly hours of the morning is when thebody temperature is at it’s lowest.4. It is a good idea to use multipledefences against fatigue, such as thoselisted below, particularly when keepingwatch during the early morning hours.■ Install a watch-keeping alarm■ Use an echo sounder shallow-water alarm■ Use radar guard zonesA remaining section of the vessel’s hull.A nearby fishing vessel, which theskipper had called for assistance, arrivedon the scene and tried unsuccessfully totow the vessel off the rocks.Realising that nothing further couldbe done to save his vessel, the skipperinflated the vessel’s liferaft and, wearinga wetsuit, pulled the two crewmembersacross the water from the rocks to theisland shore. All three were later rescued bythe local surf club’s inflatable rescue boat.The fishing vessel gradually broke upon the rocks.View the full report online at:www.maritimenz.govt.nzLookout!Points■ Use GPS waypoint-arrival alarms (setto sound on arrival at course alterationwaypoints) and cross track error alarms■ Steer by hand■ Keep a window open■ Take regular walks around thewheelhouse■ Drink coffee or tea.5. FishSAFE, a grouping of the SeafoodIndustry Training Organisation, ACC and<strong>Maritime</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>, has recentlyproduced Safety Guidelines for smallcommercial fishing vessels, whichincludes advice on fatigue. For moreinformation go to www.fishsafe.org.nzA momentsdistractionis all it takesA stevedore foreman working on aninternational container vessel was hit by aswinging pontoon hatch lid and sustainedserious injuries.The stevedore was part of a crewloading and discharging containers inwind gusting up to 35 knots. The hatchlid was being lifted by crane and thestevedore and a mate were positioned1. The stevedore was properly positionedto guide the pontoon lid into its housing,with room on either side to move outFailed hoistwire not up tospecificationA 27 tonne load of grabbed coalsmashed suddenly and without warningonto the main deck of an 18 000 grosston bulk/log carrier, when a ship’s cranehoist-wire failed. The main deck platingwas dented to a depth of about 25mm,but was not pierced. There were noinjuries to the stevedores or crew.After the accident, the crew changedthe hoist wire on the affected crane andchecked the hoist wires and associated1. The cargo gear had undergone prooftesting and a five-year thorough examinationby the ship’s classification societyabout 1 year before the accident.2. The point where the hoist wire partedwas near the right hand sheave at the topof the crane. The point where the otherwire partially failed was on the left handside of the crane jib.on either side of the stowing position,intending to help guide the pontoon lidinto place. The stevedore momentarilybecame distracted, possibly by hishand-held VHF radio. At that moment alarge gust of wind caught the pontoon lid,making it swing suddenly in his direction.The stevedore was pinned againsta ‘wall’ of containers by the pontoonof the way if necessary. However, hedid not see the lid swinging toward himbecause he had become distracted. Evencargo gear on the remaining three ship’scranes for any defects; no defects werefound at that stage. Each crane had anSWL of 30 tonnes. However, sometimeafter cargo work resumed, a secondcrane driver noticed that one strand onhis hoist wire had also parted, and theunloading of the coal cargo was stoppedat all hatches. Upon inspection, two ofthe four crane hoist wires were found tobe four-stranded wire with 39 wires per3. After the accident, an equivalentweight of coal and the grab that wasbeing used at the time was weighed.Weighbridge dockets showed thecombined weight to be 27.56 tonnes.4. After the accident, the ship’s masterwas instructed that none of the craneswas to be used to work cargo until theirhoist wires had been replaced.the hatch lid that trapped the stevedore foreman.lid and suffered nine broken ribs and apunctured lung as a result of the accident.He was rushed to hospital and wasdischarged eight days later.View the full report online at:www.maritimenz.govt.nzLookout!Pointsthough this stevedore had many years’experience, remaining vigilant during keyoperations, every time, is vital.strand, rather than the specified fourstrandedwire with 48 wires per strand.The thinner wires would havebeen less flexible, and more prone tometal fatigue as they passed through thecranes’ eight sheaves.the grab after falling onto the vessel’s deck.View the full report online at:www.maritimenz.govt.nzLookout!Points5. Two of the replacement hoistwires held on board the vessel werealso found to be the wrong size. Therewere no documented procedures in theship’s ISM documentation to ensure thathoist wires met design specificationsand construction.20 LOOKOUT! JULY <strong>2006</strong>LOOKOUT! JULY <strong>2006</strong> 21

Safety bulletin issue 6 <strong>2006</strong><strong>Maritime</strong> NZ publishes Safety Bulletins as a means of communicating and encouraging dialogue on a variety of safetyissues and the proposals relating to these. The bulletins are published as and when required, and are directed to thosesectors directly involved. They are also available to the wider maritime industry via our website. A copy of the latest Bulletinis below and we welcome any comment you may have on the recommendations or content in general.Safe Operation of Mitsubishi HeavyIndustries Hydraulic Deck Cranes<strong>Maritime</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> is investigating an accidentin which the jib of a Mitsubishi HeavyIndustries (MHI) hydraulic crane collapsed whilethe vessel was loading logs in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>.A number of similar crane accidents have occurred in the past whilelogs were being loaded, resulting in cranes being severely damaged.Fortunately, no one has been killed or injured, although there have beenseveral near misses.All the accidents have occurred when the retaining bolts attaching thecrane jibs to their heel pins either broke or loosened. This caused thecrane jibs to detach from their fittings and fall back against the craneturret. The retaining bolts were hidden by steel cover plates, so it wasnot apparent that they were either broken or had worked loose until thecrane jibs collapsed.After a crane accident in 1992, MHI carried out a stress analysis of theretaining bolts on their cranes. This showed that for the 30 tonne SafeWorking Load (SWL) MHI cranes, fitted with four 20mm diameter heelpin bolts, the safety factor reduced from 1.83 to 1.04 when the directionof the lift was changed from the vertical to 20° from the vertical. Toovercome this, all new and some existing MHI cranes have since beenfitted with six 30mm diameter-retaining bolts. There have been noreported accidents involving these cranes.However, there are still many ships built before 1992 that were fittedwith MHI deck cranes, which have not been similarly modified. Thefollowing safety precautions apply to those ships.Recommendations and Action PointsThe MHI publication Technical Information of Mitsubishi Deck CraneInspections recommends that end plate fittings and retaining bolts forjib heel pin bearings are inspected every six months or, in the case ofcranes manufactured before 1988, every 3 months.<strong>Maritime</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> has frequently found that after a change ofvessel ownership or crew that the above information regarding inspectionhas not been passed on. During the last 12 years, <strong>Maritime</strong> NZPort State Control Inspectors have come across several loose orbroken heel pin bolts, each of which could have resulted in a seriousaccident if no remedial action had been taken.Recommendations to Stevedores & Port CompaniesBefore loading cargo commences, check the ship’s records toensure that MHI cranes built before 1992 that have not beenupgraded, are being maintained and inspected as specified in theMHI Technical Information booklet.While loading, do not permit crane hoist wires to be used at anglesbeyond those specified in the crane manufacturer’s instructions. Thereis a risk of this occurring while dragging out slings from under logs.Recommendation to Ship SurveyorsAt every inspection or examination of ship’s cargo gear, ensure that allheel pin bearing cover plates are removed and each bolt is tested witha spanner. Broken, loose or suspect bolts should be replaced with themanufacturer’s specified parts.Recommendation to <strong>Maritime</strong> Safety InspectorsDuring Port State Inspections or any inspections carried out at therequest of a concerned party, ensure that:The required inspections of Mitsubishi cranes, as specified in theMHI Technical Information booklet, have been carried out andrecorded in a format shown in the Technical Information’s “CheckList of Thrust Stopper Bolts”.There is a record of heel pin bearing cover plates having been removedfor inspections during the last 3 or 6 months as appropriate.If there is any doubt about the condition of the cranes or whetherinspections have been properly carried out, heel pin bearing cover platesshould be removed and each bolt tested for tightness using a spanner.If you have any queries, or require more detail pleasecontact John Mansell, General Manager, <strong>Maritime</strong>Operations, <strong>Maritime</strong> NZ on 04-494 1228.Subscribe to Lookout! and Safe Seas Clean SeasTo receive these free quarterly publications, to change your addressdetails or tell us about others who may want to receive them, email usat publications@maritimenz.govt.nz or phone 0508 22 55 22.Disclaimer: All care and diligence has been used in extracting, analysingand compiling this information, however, <strong>Maritime</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> gives nowarranty that the information provided is without error.Copyright <strong>Maritime</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> <strong>2006</strong>: Parts of this document maybe reproduced, provided acknowledgement is made to this publicationand <strong>Maritime</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> as source.ISSN: 1177-2654