Spring - NWIFC Access - Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

Spring - NWIFC Access - Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

Spring - NWIFC Access - Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

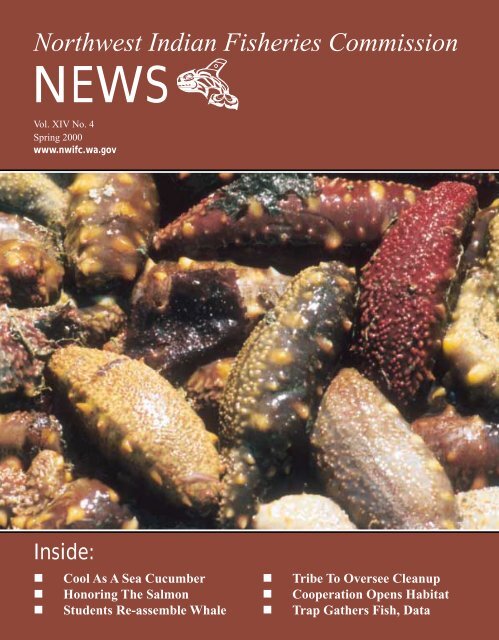

<strong>Northwest</strong> <strong>Indian</strong> <strong>Fisheries</strong> <strong>Commission</strong>NEWSVol. XIV No. 4<strong>Spring</strong> 2000www.nwifc.wa.govInside: Cool As A Sea Cucumber Honoring The Salmon Students Re-assemble WhaleTribe To Oversee CleanupCooperation Opens HabitatTrap Gathers Fish, Data

Being FrankA New Look At HatcheriesBy Billy Frank Jr.<strong>NWIFC</strong> ChairmanThis is a time of great change inthe management of the salmon resourcein the State of Washington.Listings of several local salmonstocks under the Endangered SpeciesAct have required us to re-examinemany of our approaches tothe way we manage salmon.Our use of hatcheries is one example.Today the tribes, as well asstate and federal agencies, are looking at salmon hatcheriesin new ways.Once viewed by many simply as “factories” for producingsalmon, now we are reforming hatchery practices tohelp recover and conserve wild salmon populations whileproviding sustainable fisheries for <strong>Indian</strong> and non-<strong>Indian</strong>fishermen.While the tribes have made efforts over the past decadeto reduce impacts of hatcheries on wild salmon stocks –such as carefully timing releases of young hatchery salmoninto rivers to avoid competition for food and habitat withyoung wild salmon – a lack of funding has prevented thetribes from applying a comprehensive, systematic approachto hatchery reform.Now, thanks to the efforts of Washington’s congressionaldelegation, the treaty tribes, Washington Department ofWildlife, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine<strong>Fisheries</strong> Service will share $3.6 million this year toconduct much-needed research, monitoring and evaluationof hatchery practices at the approximately 150 tribal, stateand federal hatchery facilities in western Washington.Federal legislation has created an independent HatcheryScientific Review Group to provide scientific oversight fortribal, state and federal hatchery practices reform and toprovide recommendations for implementation of scientificgoals and strategies. A top priority of the tribal and stateco-managers under the hatchery reform initiative will be tocomplete Hatchery Genetic Management Plans for eachspecies at each hatchery on Puget Sound. The plans willprovide a picture of how stocks and hatcheries should bemanaged, and will serve as a tool for implementing hatcheryreform.Already, some salmon enhancement facilities have beenswitched from producing hatchery fish to restoring wildfish through broodstocking and supplementation. Throughthese programs, wild salmon are captured and spawned ata hatchery. Their offspring are then reared in the facility(Continued, Next Page)On The Cover: A mass of sea cucumbers harvested by a Nooksack tribal fisherman await processing. Sea cucumbers, adelicacy in parts of Asia, are related to sea urchins and sand dollars. See story on Page 4. Photo L. Harris2<strong>Northwest</strong> <strong>Indian</strong> <strong>Fisheries</strong> <strong>Commission</strong> NewsThe <strong>NWIFC</strong> News is published quarterly on behalf of the treaty <strong>Indian</strong> tribes in western Washington by the <strong>Northwest</strong> <strong>Indian</strong><strong>Fisheries</strong> <strong>Commission</strong>, 6730 Martin Way E., Olympia, WA 98516. Complimentary subscriptions are available. Articles in<strong>NWIFC</strong> News may be reprinted. An electronic version of this newsletter is available at www.nwifc.wa.gov.Jamestown S’Klallam .... 360-683-1109Lower Elwha Klallam .... 360-452-8471Lummi ............................ 360-384-2210Makah ............................. 360-645-2205Muckleshoot ................... 253-939-3311Nisqually ........................ 360-456-5221<strong>NWIFC</strong> Member TribesNooksack........................ 360-592-5176Port Gamble S’Klallam .. 360-297-2646Puyallup ......................... 253-597-6200Quileute .......................... 360-374-6163Quinault .......................... 360-276-8211Sauk-Suiattle .................. 360-436-0132Skokomish ..................... 360-426-4232Squaxin Island ............... 360-426-9781Stillaguamish .................. 360-652-7362Suquamish ...................... 360-598-3311Swinomish ...................... 360-466-3163Tulalip ............................. 360-651-4000Upper Skagit .................. 360-856-5501<strong>NWIFC</strong> Executive Director: Jim Anderson; <strong>NWIFC</strong> News Staff: Tony Meyer, Manager, Information Services Divisionand South Puget Sound Information Officer (IO); Logan Harris, Strait/Hood Canal IO; Jeff Shaw, North Sound IO;Debbie Preston, Coastal IO; and Sheila McCloud, Editorial Assistant. For more information please contact: <strong>NWIFC</strong>Information Services at (360) 438-1180 in Olympia; (360) 424-8226 in Mount Vernon; (360) 297-6546 in Kingston;or (360) 374-5501 in Forks.

PassagesJoe DeLaCruzJoe DeLaCruz died April 16 at the age of 62. Amongmany other distinctions, he had been President of theQuinault <strong>Indian</strong> Nation, the National Congress of American<strong>Indian</strong>s, the National Tribal Chairmen’s Associationand the Affiliated Tribes of <strong>Northwest</strong> <strong>Indian</strong>s. He mademonumental contributions to tribal education, health care,economic development, natural resource managementand self- governance."He was one of the greatest <strong>Indian</strong> leaders who ever Joe DeLaCruzlived in the United States," said Billy Frank, Jr. chairmanof the <strong>Northwest</strong> <strong>Indian</strong> <strong>Fisheries</strong> <strong>Commission</strong>.DeLaCruz served the tribes faithfully for more than three decades, amassingvast experience as a leader in natural resource management, health care,education, economic diversity, governance and tribal culture. He was a staunchsupporter of the <strong>Northwest</strong> <strong>Indian</strong> <strong>Fisheries</strong> <strong>Commission</strong>, a founding memberof the <strong>Northwest</strong> Renewable Resources Center, co-chair of the <strong>Commission</strong>on State-Tribal Relations, one of the creators of the Pacific Salmon<strong>Commission</strong> and member of the Washington State Historical Society.The Centennial Accord, signed by Governor Booth Gardner and tribalchairs from throughout Washington in the state’s centennial year of 1989,was Joe DeLaCruz’s idea – an idea that has since captured the imaginationof indigenous people and governments throughout the world. The TribalSelf-Governance Program, which he also helped originate, likewise convertedthe principles of tribal sovereignty and government-to-governmentrelations into reality. These, and many other DeLaCruz achievements in thearena of tribal self-determination, were the manifestation of beliefs which heexpressed as follows:"No right is more sacred to a nation, to a people, than the right to freelydetermine its social, economic, political and cultural future without externalinterference. The fullest expression of this right occurs when a nation freelygoverns itself. We call the exercise of this right self-determination. The practiceof this right is self-government."More than 2,000 people – tribal officials from near and far, elected representatives,friends, neighbors and family members – commemorated the lifeof "Skinny Joe" DeLaCruz at services conducted April 22 at the new QuinaultTribal Resort in Ocean Shores."Joe DeLaCruz will always be a part of Washington state, just as this landwas always a part of him," said Governor Gary Locke.Younger brother Franklin DeLaCruz placed a wooden staff in the casket,adorned with carvings of a two-headed wolf, the DeLaCruz family crest, aswell as a bear, an eagle, an orca and a spawning salmon, signifying the circleof life. "He needs to go to the other side with something like this powerfulstaff," he said.DeLaCruz was buried on the Colville Reservation April 24 – an agreementbetween he and his wife, Dorothy, a Colville tribal member. Other survivorsinclude three daughters, two sons, seven grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.– S. RobinsonBeing FrankContinued From Page 2and later released in various locationswithin the watershed to increase theirchances for survival.Hatchery reform is part of an integratedstrategy for salmon recovery.The tribal and state co-managers areresponding to declining wild salmonpopulations through improved planningprocesses like Comprehensive Cohoand Comprehensive Puget Sound Chinook,which seek to protect and restoreadequate freshwater habitat and to ensurethat enough adult salmon reach thespawning grounds to recover the stocks.As part of the effort, recovery goals andcomprehensive recovery plans are beingdeveloped for all salmon species inwestern Washington. Specific recoveryplans are being developed for each watershedto guide how harvest, habitatand hatcheries will be managed.The treaty <strong>Indian</strong> tribes in westernWashington already have made significantharvest reductions to protect weakwild stocks. In fact, over the past 25years, treaty tribal salmon harvests havebeen reduced by more than 90 percent.This has come at a great cost to thespiritual, cultural and economic wellbeingof the tribes.For 2000, the tribes are planning conservativefisheries that are more restrictivethan last year to protect weak wildsalmon stocks. While recognizing thereare some strong hatchery chinook returnsexpected, tribal fisheries will bedesigned to contribute to the rebuildingof Puget Sound chinook, which havebeen listed as threatened under the EndangeredSpecies Act.All of these steps will have little effect,however, if there are no similarefforts to protect salmon habitat. Lostand damaged salmon habitat has been,and continues to be, the main reasonfor the decline of wild salmon.We are confident, however, that byworking together we can achieve ourgoal of returning wild salmon stocks toabundance.(See Related Story On Page 5)3

Fishery Provides Extra OpportunityCool As A Sea CucumberBased on itsunusual defensemechanismalone –expelling its internalorgans toentangle or distractwould-bepredators – thehomely, bottom-dwellingsea cucumbermay test mostAmericans’idea of a tasty menu item.Nooksack fisherman Mario Narte hauls upa catch of sea cucumbers north ofBellingham in March. Photos: L.HarrisBut the leathery tube-shaped echinoderm is much loved inthe Asian diet, which is why tribal fishermen looking foryear-round harvest opportunities may increasingly pursuethe spiny creatures in Puget Sound waters. Millions of therust-colored sea cucumbers, ranging from roughly six inchesto two feet in length and beyond, are available on the PugetSound floor as they sluggishly move along while feeding onmicroscopic organisms.Diving and trawling are the common sea cucumber fishingmethods and Mario Narte, a Nooksack tribal fisherman,has fished both ways from his versatile 46-foot purse seiner,the Marysville.“It’s a way to keep fishing until shrimp season,” said Narte,whose longest sea cucumber-fishing stretch surpassed 28hours. “The more tows, the more pounds.”On his best day Narte said he brought up 2,300 pounds ofsea cucumbers, but noted 900-pound days are more common.Narte said he was getting about $1.25 per pound fromOrient Seafoods, a Vancouver, British Columbia, buyer. Thetribes were allowed 314,000 pounds in the San Juans, onlya percentage of which were available by trawl.By regulation, Narte trawls at least 120 feet deep. He mustmove to another fishing spot if bycatch of any other commerciallyharvested species exceeds 10 percent. Trawlingat only 1 knot, most species, such as crab, are able to avoidthe trawling net. Bycatch is largely limited to clamshells,seaweed, a few flatfish, and small crabs, notes Nooksackharvest manager Gary MacWilliams.MacWilliams said the fishery is closely monitored to ensurenegative impacts to other species and sea-bottom habitat remainnegligible. “We’re seeing minimal habitat degradationwith the manner restrictions currently in place,” he said.Like most tribal fishermen, Narte started out pursuingsalmon, but with declining salmon runs and fishing closureshe’s had to hustle and diversify his business. A completeshutdown of sockeye fishing in the San Juans wipedout many tribal fishermen last year, but Narte hung on partlyby fishing for shrimp, crab, sea urchins and sea cucumbers.He’s even interested in fishing sea snails as he sees moreopportunity in Asian markets.“The big heyday of sockeye salmon fishing is just aboutover,” Narte said. “You have to be creative and find othertypes of fishing if you want to survive. You have to diversify.”Trawling inroughly hourlongintervals,Narte andcrewmen EdGladstone, aNooksackmember, andBarry Westley,a Lummimember, haulup the catch.If not pretty, sea cucumbers can meanharvest opportunity for tribal fishermen.The cucumbers are separated from the rocks, weeds andbycatch and loaded onto a tray table where they are splitand drained of water. Market weight is determined afterthe creatures are split and drained.The sea cucumber is a prized food in the Asian market. Itis sold in a smoked, dried form or as a powdered dietarysupplement. It is sought for use in soups and even as anaphrodisiac. Though managed as a shellfish, the sea cucumberis an echinoderm and is closely related to the seaurchin, starfish and sand dollar. And while it may expel itsinternal organs to entangle or distract would-be predators,the organs are ultimately regenerated.Sea cucumbers may possess strange habits and a less-thanpicturesqueprofile, but with salmon seasons increasinglyclosed or restricted, the creatures can rate more beautifulthan a dime-bright sockeye.“It’s a modern reality that if a tribal fisherman wants tomake a living at fishing, he’ll have to get creative andgear up for more than salmon,” said Bob Kelly, NaturalResource Director for the Nooksack Tribe. “Fish managersare working hard to provide more opportunities andmarkets to keep fishermen working year round.”– L. Harris4

Lummis Honor First SalmonNot only did the Lummi Nation greet the first returning salmon of theyear — they made sure future returning salmon would have plenty of company.Using song, dance and ritual, the tribe welcomed the first returning salmonof the year recently. More than 350 people – from youth to elders – attendedthe ceremony that honors the fish and encourages the return of salmon runs.Additionally, the tribe released 20,000 fall chinook from its Skookum CreekSalmon hatchery into the Nooksack River on the day of the ceremony.That’s just a part of a larger program, where the tribe has released 500,000fall chinook in conjunction with the State of Washington.This year’s ceremony was a special one for many reasons, including thedancing and participation of young people from Lummi Tribal School.“This is a first for the tribal school, and it is a beginning for the LummiNation,” said tribal member Jack Cagey. “From here on, as long as the riverflows and the grass grows, this ceremony will go on.”This year’s first salmon was carried respectfully into the tribal school gymnasiumon a “slawen” – a mat woven from cattails – and welcomed into theroom by the waving ferns of tribal school dancers. The young dancers’performances included a dance which symbolizes the life cycle of the remarkablefish, from the spawning of salmon parents to the returning creatures’upriver journey.Cagey said that the dance honors the “miracle” that the salmon representsfor native people.“It’s hard to describe how one feels in the heart about this,” he said. “It’sfrom this salmon that all living things make their lives.”Everyone in attendance was encouraged to take a piece of the ceremonialsalmon for themselves. When all that remained of the fish was its skeleton,the bones were carefully nestled into the flow of the Nooksack River.Lummi Director of Natural Resources Merle Jefferson said that the ceremonyrepresents the tribe’s commitment to the salmon, and to the biologicalhealth of the region’s ecosystems.“Everyone knows the Nooksack River is very stressed, ecologically speaking,”said Jefferson. “We at Lummi Nation are doing all we can to help theriver regain its health.”Tribal HatcheriesRelease Nearly43 Million SalmonPuget Sound and coastal treaty <strong>Indian</strong>tribes released nearly 43 million healthyhatchery fish in 1999, according to recentlycompiled statistics.Of the 42,782,792 fish released, most(16,050,951) were chum salmon. Substantialnumbers of fall chinook(12,510,096) and coho (11,236,984)were also released. Releases also included1,498,618 spring/ summerchinook and 1,186,284 steelhead. Additionally,69,328 pink and sockeyesalmon were released from the Makahtribal hatchery.Some of the fish were producedthrough cooperative enhancement effortsof the tribes, the Washington Departmentof Fish and Wildlife, state regionalenhancement groups, U.S. Fishand Wildlife Service, and sport or communityorganizations.Tribal hatchery programs are designedto minimize any potential impact on wildsalmon stocks, said <strong>Northwest</strong> <strong>Indian</strong><strong>Fisheries</strong> <strong>Commission</strong> chairman BillyFrank, Jr.“The tribes, as well as state and federalagencies, are reforming hatcherypractices to help recover and conservewild populations while providing sustainablefisheries for both tribal and nontribalharvest,” Frank said.While the tribes have made constantefforts over the past decade to reformhatchery management procedures – includingcarefully timed releases ofyoung hatchery salmon, which help toavoid competition with wild salmon forfood and habitat – new congressionalfunding has given these initiatives a seriousboost.“Hatchery reform is an important partof an integrated salmon recovery strategy,and we will continue to adapt ourhatcheries to reflect the best availablescience,” Frank said.5

'It's Finishing What We StartedMakah High School StudentsAssemble Bones Of Historic WhaleTribal students from Neah Bay High School say it isfitting that they are assembling the bones of the first whaleharvested by the Makah Tribe in 70 years.“It’s finishing what we started,” said senior DanielGreene. “It fits in with the history of Ozette and it will bea good part of history itself. It established our treaty rightsagain,” he said.The finished skeleton will hang in the Makah Culturaland Research Center. It will join thousands of Makahwhaling artifacts from the ancient Ozette village, an archaeologicalsite just south of Neah Bay.Daniel Greene’s father, Dan, was a member of the whalingcrew. The younger Greene was also an integral part ofthe celebration, welcoming guests and elders in the Makahlanguage. He wants to get his college degree and return toteach the Makah language to the next generations of Makahchildren.Patrick DePoe, 17, remembers May 17, 1999 vividly.“I helped tow the whale to shore. It was a great day,”said DePoe. “Working on this project feels really good.The museum is where it belongs. It was a historical moment,”he said.Two classes at the school areparticipating in the complex,often smelly job of preparingand assembling the bones.“There has been a way forall the students to participate,”said woodshop instructor BillMonette.“People immediately think about this only in terms of itbeing the whale that was harvested, but the school wantedto be sure there was a diverse educational component tothis,” Monette said. “There is math involved, understandingthe biology and anatomy of the whale, how it’s put together,problem solving, and of course, the cultural component.When the kids get to working on it, they are really into it,”he said.“It’s really great that the kids are able to do this project,”said Ben Johnson, Makah tribal chairman. “Having the skeletonhang in the museum and having it done by the kidsbrings everything full circle. Now, when people visit themuseum, it’s living proof that we’re whalers — not onlythen, but now,” Johnson said.The students received help assembling the whale from theMuseum of Natural Historyin Denver, the NationalMarine <strong>Fisheries</strong>Service, and a biologistfrom the U.S. Navy.“Things that needed tohappen in order for thisto get done just sort of fellinto place. It was meantto be,” said Monette.The students andMonette have put morethan 1,000 hours of workinto the project and hopeto finish it before the endof the year. As part of theproject, Ross Jimmacum,18, has been drawing twohuge whales on the walls6

Upper left: Bill Monette, left, and Travis Butterfield, work to piecetogether part of the gray whale harvested by the Makah Tribe. Thesecond skull is of a whale that washed ashore in Puget Sound. Above:Gordon Steeves III aligns rib bones and vertebrae. Left: Neah BayHigh School students pose with the whale bones they are reassemblingfor display at the tribe's cultural center. Photos: D. Prestonof the shop, one facing north and one facing south, for the twomigration routes.Amanda Jimmicum, disappointed that she was away the day thewhale was brought to the village, is proud to work on assemblingthe bones. She plans to be on hand for the next successful hunt andlooks forward to one day taking her children to the Makah Culturaland Research Center to show them the re-constructed skeleton ofthe first whale.“I’m really proud I can say I helped put it together,” saidJimmicum. – D. PrestonSuquamish Tribe,Navy Reach AccordDemonstrating a commitment to solvingproblems through cooperationwhenever possible, the Suquamish Tribeand the United States Navy reached agroundbreaking agreement on habitatrestoration in Bremerton’s Sinclair Inletin May.The tribe and the military settled alawsuit filed by the Suquamish over theNavy’s plan to dredge the inlet and constructa new pier in the body of water.The plans should create an effectiveport for the armed forces’ huge Nimitzclass aircraft carriers – but the tribeworried that construction processesmight damage salmon habitat and destroycrucial fishing and shellfishingopportunities.“This agreement reflects the Navy’srecognition of its responsibility, as a federalagency, to protect our treaty-reservedfishing rights – rights which dependupon a healthy habitat,” said tribalchairman Bennie Armstrong.The accord, manifested in a memorandumof understanding, features bothsides vowing to “plan and implementmutually acceptable habitat mitigation”together.“The Suquamish Tribe always prefersto solve problems through cooperation,rather than litigation,” tribal attorneyScott Wheat said. “Fortunately, wewere able to come up with an arrangementthat satisfies both parties and protectsthe regional environment as well.”The City of Bremerton issued theNavy a conditional use permit whichauthorized the dredging and construction.But the tribe worried that such anextensive undertaking could thwart culturalresource protection, hinder habitatpreservation and harm fishing opportunities.Under the new agreement, though,mutually acceptable mitigation measureswill occur. Additionally, $1.4 millionwill be earmarked for habitat restorationin the area. – J. Shaw7

Tribe Will Oversee Pulp Mill CleanupY’innis means “good beach” in theKlallam language and was the name ofa major tribal village that once thrivedat the mouth of what is now EnnisCreek.Today the “good beach” is poisonedby dioxin and PCBs contaminating itssoil and groundwater. The now-closedand torn down Rayonier Inc. pulp mill— which operated at the site for sevendecades — is responsible for toxic pollutionthat has also leached into PortAngeles Harbor.Strong cultural ties — including anancestral burial ground – and concernfor its fishing resources in the creek andharbor are why the Lower ElwhaKlallam Tribe signed a landmarkagreement in May with state and federalagencies to clean up the site. Underthe agreement — rare for the cloutprovided a tribe in an off-reservationcleanup — the state Department ofEcology (DOE) will lead the projectconditioned upon a number of tribalrequirements.“We were pleased to get a seat at thetable, especially since the site is off-reservation.It’s the first time that has happenedin the nation,” said tribal ChairmanRuss Hepfer. “It is important tohave our deep cultural and fishing tiesto this place recognized.”Four years of detailed studies to learnthe extent of the pollution problem,along with public involvement and planning,will precede any cleanup. Butthat’s fine with the tribe so long as thejob is done right.Sparked by environmentalists’ concernsabout contamination once the millwas torn down in 1998, the EnvironmentalProtection Agency (EPA) tooksoil samples suggesting pollution levelswere high enough to qualify the site forSuperfund cleanup. Considered “moderatelypolluted,” the EPA indicated the75-acre site could be cleaned up understate laws.The Lower Elwha Klallam Dancers perform before a mural of the Y’innis Village ata ceremony in May. The event celebrated the tribe’s role in cleaning up pollutionat the site of the former village. (Photo: Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe)Local and state officials, and the millowner, didn’t want the stigma of a federalSuperfund site in Port Angeles, anddidn’t want to cede control of thecleanup to a federal agency. But theyneeded tribal sign-off on a state deferral,because the fishery impacted by thepollution is considered a tribal propertyright.The tribe initially supportedSuperfund status because deferring thecleanup to the state DOE might meanno tribal role or funding to ensure propercleanup. The agreement worked becausethe state needed Lower Elwha’ssign-off and was willing to negotiate,and because the mill owner, Rayonier,was willing to pay the cleanup costs.Rayonier will reimburse the tribe for itsexpenses up to $250,000 per year.If tribal conditions aren’t met, LowerElwha essentially has veto power in thestate deferral agreement and could againsupport Superfund listing.“We got everything we wanted exceptfor funding to restore EnnisCreek,” said Hepfer. “We’ll have to goelsewhere to find funding to restore thestream.”A large painted mural near the PortAngeles City Pier portrays early 19 thcentury life in the wealthy, fortifiedY’innis village. It was one of two largeKlallam villages in the harbor. TheY’innis site was occupied by the PugetSound Cooperative Colony in 1887 andsome surviving Klallams continued tolive on beaches of the harbor until the1930s, when lands were purchased fora reservation on the Elwha River.In 1917 the U.S. Government built asawmill on the site for milling sprucewood. The sawmill was rebuilt into apulp mill in 1929-1930. Rayonier operatedthe pulp mill from the 1930s untilits closure in February 1997. Prior toclosing it was the largest private employeron the North Olympic Peninsula.– L. Harris8

In Dungeness River WatershedJamestown S’Klallams,Agencies Working ToFind Pollution SourcesDebbie Sargent, water quality specialist for the WashingtonDepartment of Ecology, takes a water sample from theDungeness River as part of a sediment study by the JamestownS’Klallam Tribe. Photo: D. PrestonAs sediment and bacteria increasingly seep into the DungenessRiver watershed, fewer salmon are returning and DungenessBay shellfish are becoming unsafe to eat.Help may be on the way. The Jamestown S’Klallam Tribeis hoping a number of ongoing Dungeness River water qualitystudies will reveal relationships between the sediment,pollution and the tribe’s fisheries, as well as pinpoint sourcesof the problems.Included is a two-year, $125,000 sediment study that beganin May. The tribe is splitting the cost of the study withthe U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) after receiving a CentennialClean Water Fund grant from the state Departmentof Ecology (DOE). Preliminary results are expected within amatter of months, with a final report on USGS survey workdue in March 2001.“This information is needed by federal, state and localagencies and the tribe to develop salmon recovery plans, aswell as detailed plans to restore river and estuary functions,and to take actions necessary to reverse the shellfish closure(in Dungeness Bay),” said Ron Allen, Chairman of theJamestown S’Klallam Tribe.Increased levels of fecal coliform bacteria prompted thestate Department of Health in April to close commercialshellfish harvesting on a portion of Dungeness Bay. Theclosure hit the tribe’s shellfish operation hard, effectivelyreducing its oyster farm by one third.Another study being carried out by DOE, in cooperationwith the tribe, is monitoring freshwater for bacteria and flowsto try to pinpoint sources of fecal coliform bacteria.“By last summer, it was obvious the bacteria problem hadspread out in the bay,” said Lyn Muench, natural resourceplanner for the tribe. “We had a heads up, but the fix is notas easy as we had hoped. We’re still trying to find thesources.”Tribal staff have battled the effects of low flows and sedimentationin the Dungeness River for many years as runs ofpink and chinook salmon dwindled to a fraction of theirformer abundance.Bacteria and sediment sources will be difficult to pinpointuntil the tribe, DOE and USGS install and, over time, monitora series of flow, sediment, temperature and water qualitysampling stations along a 12-mile section of the lower river.Sampling, monitoring and an investigation of water circulationpatterns will also take place in the bay as part of thestudy.Poorly built and maintained logging roads are blamed forcontributing large quantities of sediment into streams thatfeed the Dungeness River. Land clearing and historical loggingpractices along the river have also created erosion problems.Sediment can bury salmon eggs and spawning gravels.When sediment exceeds a stream’s ability to transport it,salmon habitat is destroyed as channels shift, resting poolsfill, streambeds rise and wetlands and estuaries are chokedoff.The sediment study will also investigate whether silt ishelping transport bacteria to the bay. “We want to know ifthere is a linkage – if the sediment coming down the riveris playing a role in bacteria retention,” Muench said.No single polluter is suspected. Rather, farms with highnumbers of livestock and poor waste management practices,and robust residential development — with its accompanyingseptic tanks and leaking drainfields — are suspected culpritsin the climbing fecal coliform counts. Population numbersin the Dungeness River basin have more than tripled inthe last 25 years.“We can’t address the threats to our watershed, salmonand shellfish until we find the specific source of those problems,”said Allen. “This study will help us do that.”– L. Harris9

Quileutes Aid WhaleBehavior ResearchGray whales are a common sight alongthe Washington coast during their springand fall migrations. What isn’t commonis the opportunity to observe them fromshore for long periods of time.That rare opportunity is what is drawingone researcher to LaPush, home ofthe Quileute Tribe. The tribe is takingthe lead in learning more about the graywhales that return to LaPush annually.They have invited researcher JayMallonee, who specializes in mammalbehavior, to study in LaPush. Malloneehopes to add to the body of knowledgeabout gray whale behavior through hisown observations, those of his students,and by talking with Quileute tribal members.'The behaviors werethings I’d never seenbefore.'– Jay Mallonee,Whale Researcher“The tribe is establishing an informationbase about whales for scientific,educational and interpretive purposes,”said Mitch Lesoing, marine biologist forthe Quileute Tribe.“Relatively little has been describedabout how the gray whales use thecoastal habitat at LaPush during theirunique migration. Quileute tribal membersare experienced whale observersand much information has been passedalong over the centuries. Jay’s observationswill shed more light on describingcurrent whale behavior and he isanxious to exchange whale knowledgewith tribal members,” said Lesoing.“I had known about thewhales coming to LaPushfrom word of mouth, butwhen I got here, I was justamazed. The behaviorswere things I’d never seenbefore,” said Mallonee.Stories passed downthrough hundreds of years link the birthof the Quileute Tribe to the whale. Thesea and the food it provides still sustainthe tribe and it is integral to their culture.Obtaining more knowledge aboutthe gray whale and their required habitatis a necessary component for responsibleresource management.Every year, female gray whales andtheir calves stop at LaPush, apparentlyto feed. They can be seen where wavesbreak off First Beach in LaPush, nomore than 30 yards off shore. The behaviorof “spy hopping,” where thewhales rise vertically to about one-thirdof their body length to take a lookaround, is also seen off the beaches ofLaPush and neighboring beaches withinOlympic National Park in the tribe’susual and accustomed area of fishingand gathering.It’s these kinds of behaviors thatMallonee wants to watch and catalogue.“You can actually put together a lotabout what’s going on underwater bymeticulously recording what is goingabove the water,” he said.“Shore-based observation is very nonintrusive– it doesn’t alter the whalebehavior as a boat might. It’s alsocheaper. You can do scuba dives later,after you’ve established normal behaviorpatterns,” Mallonee said.The Quileute Tribe is interested inMallonee’s research for a number ofreasons. As word has spread aboutLaPush as a refuge from a busy world,Researcher Jay Mallonee scans the waters off LaPush.Photo: D. Prestona surfing mecca for the hardy, and awhale-watching base, more and moretourists have come to visit.“Along with the scientific knowledge,the tribal council is interested in knowinghow more visitors and their activitiesmight affect the whales. They arealso interested in the future of havingthe students at the tribal school participatein some of the observations andestablishing a curriculum,” said Lesoing.Mallonee also wants to develop a programpartnering with the tribal schooland natural resources program that willenable school students to participate inwhale observations. The idea is to providea hands-on approach through studiesat the school that will inspire youngstudents to continue on with careers inthe natural sciences or the marine education/interpretivefield.The tribe is also looking at possibilitiesof creating careers for tribal membersby providing wildlife observationopportunities and developing interpretivefacilities that describe natural andcultural histories.“There is a lot here in terms of themarine coastal environment, natural resourceuse and traditional tribal cultureto interpret for students and visitors,”said Lesoing. “We really like the ideaof students and visitors learning handsonabout marine science and the coastalenvironment at the same time they arelearning about Quileute tradition andculture.” – D. Preston10

On Sol Duc RiverCooperative Project Re-Opens HabitatSalmon habitat that has been inaccessible for more than50 years will soon open at a tributary to the lower Sol DucRiver thanks to a cooperative project by the Quileute Tribe,Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW),People For Salmon, and Pacific Coast Salmon Coalition.The approximately $181,000 project can be found just offthe Quillayute Prairie Road near its junction with Highway110 near Forks.“This project opens up an original side channel of the riverthat was closed around World War II when the U.S. Navybuilt the bridge over the Sol Duc River,” said AdamKowalski, Timber Fish and Wildlife biologist for the QuileuteTribe.The bridge will not be altered, but a waterfall blocking theside channel will be eliminated by inserting a large culvert.Quileute tribal members Gene Gaddis and Eugene Jacksondug out a part of the old side channel by hand; water flow isexpected to do the rest of the work. The waterfall blockingfish passage was created in the 1940s when the bridge wasbuilt for access to a military airport on Forks Prairie.Suitable places for salmon to spawn and rear are key totheir survival. Side channels such as the one being re-openedprovide a place for young fish to escape high river flowsduring the winter and provide pools for adult fish to spawn.“This project is one we identified in a ranking processwhen we conducted watershed analysis for the Sol Duc Riverin 1995-96,” said Mel Moon, director of the Quileute Natu-ral Resources department. Watershed analysis assesses currentphysical, biologicaland other conditions toidentify and provide informationto guide restorationactivitieswithin a watershed.The Sol Duc analysiswas completed by ateam involving theQuileute Tribe, OlympicNational ForestService, the WashingtonDepartment of Fishand Wildlife and USFish and Wildlife Serviceand other stateagencies.“People can see thatthe falls were a definitebarrier to any fishmovement. Now withthe new gradual accessQuileute tribal members GeneGaddie, left, and Eugene Jacksonexcavate river mud from a sidechannel of the Sol Duc River nearForks. Photo: D. Prestonroute they should be able to see fish moving back into thecreek. It may take awhile, but coho salmon are biologicallywell-suited to use the new route first. Chinook are a littlemore selective because of their size, but conceivably, allsalmon will use that area,” Moon said. – D. PrestonAwesomeAnglingJesse Bowen, 12, displays arainbow trout he caught at theUpper Skagit Tribe’s Kids FishingDay. Over 100 young peopleranging from pre-schoolers toteenagers tried their hand at snaringthe wily fish from ponds at thetribe's hatchery. This is the thirdconsecutive year the Upper Skagittribal community has hosted theevent. Photo: J. Shaw11

Smolt Trap Gathers Fish, InformationAs daylight fades over Monroe, a crew gracefully positionsa contraption over the Skykomish River’s fish run.Once the metal trap has reached the middle of the river, itwill begin collecting salmon smolts from the water – andgathering data invaluable to salmon recovery efforts.The Tulalip Tribes are undertaking the first comprehensivestudy of this type on the Skykomish River. BeginningApril 4, scientists and technicians began capturing and releasingmigratory fish – all to learn more about the uniquelife process and population size of the chinook salmon.“It’s been successful in other places,” said Kurt Nelson,fish and water wildlife resources scientist with the TulalipTribes, “but nobody has tried this means to assess populationsize on the Skykomish before.”The equipment the tribal team uses – called a ‘screw trap’– allows technicians to monitor fish without injuring them.Fish are drawn in through the trap’s wide ‘cone,’ which isdesigned to safely capture the young salmon, and are funneledinto an holding area. There, the juvenile salmon andtrout will be counted, measured and set free.The design of the trap, which was fine-tuned by Lumminatural resources biologist Mike MacKay, is spreading. Onthe lower portion of the Nooksack River, Lummi teams haveoperated a trap since 1994. A crew from the Nooksack Tribecurrently operates one on the south fork of the NooksackRiver. The Stillaguamish Tribe is going through the permittingprocess for a smolt trap of its own as well.The research efforts have similar aims: to examine howmany fish are traveling to the sea, how successful their migrationsare, and the means the salmon use to survive.“This is going to give us quite a bit of information onpopulation size, behavior, migratory patterns, freshwatersurvival, and what kind of life cycle variations exist amongchinook,” Nelson said.From left, Kurt Nelson, Miriam Bill and Gene Enick monitorthe Tulalip Tribes’ smolt trap on the Skykomish River nearMonroe. Photo: J. ShawHarvest managers rely on that kind of data to forecast thesizes of fish runs. It should also prove useful to habitat managerswho are working on a recovery plan for the Skykomishwatershed.This research effort is focused on the river’s chinook run,but will also provide information on coho, chum, sockeye,and pink salmon, as well as cutthroat, steelhead, brown bulland Dolly Varden trout.The Tulalip project is a cooperative effort with SnohomishCounty, and is fully funded over the next two years – throughan Environmental Protection Agency grant during 2000 anda Bureau of <strong>Indian</strong> Affairs grant during 2001. The TulalipTribes are planning to undertake a similar research projecton the Snoqualmie River next year. – J. Shaw<strong>Northwest</strong> <strong>Indian</strong> <strong>Fisheries</strong> <strong>Commission</strong>6730 Martin Way EastOlympia, WA 98506(360) 438-1180BULK RATEU.S. POSTAGEPAIDMAIL NW