Push and Pull Factors in International Nurse Migration - University of ...

Push and Pull Factors in International Nurse Migration - University of ...

Push and Pull Factors in International Nurse Migration - University of ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

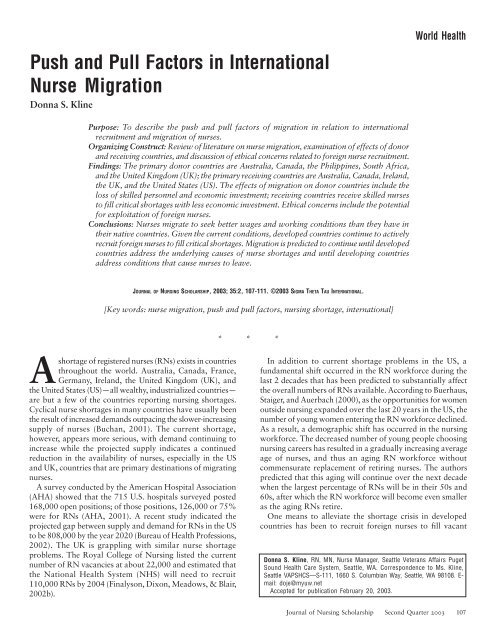

<strong>Push</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Pull</strong> <strong>Factors</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>International</strong><strong>Nurse</strong> <strong>Migration</strong>Donna S. Kl<strong>in</strong>eWorld HealthPurpose: To describe the push <strong>and</strong> pull factors <strong>of</strong> migration <strong>in</strong> relation to <strong>in</strong>ternationalrecruitment <strong>and</strong> migration <strong>of</strong> nurses.Organiz<strong>in</strong>g Construct: Review <strong>of</strong> literature on nurse migration, exam<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> donor<strong>and</strong> receiv<strong>in</strong>g countries, <strong>and</strong> discussion <strong>of</strong> ethical concerns related to foreign nurse recruitment.F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs: The primary donor countries are Australia, Canada, the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es, South Africa,<strong>and</strong> the United K<strong>in</strong>gdom (UK); the primary receiv<strong>in</strong>g countries are Australia, Canada, Irel<strong>and</strong>,the UK, <strong>and</strong> the United States (US). The effects <strong>of</strong> migration on donor countries <strong>in</strong>clude theloss <strong>of</strong> skilled personnel <strong>and</strong> economic <strong>in</strong>vestment; receiv<strong>in</strong>g countries receive skilled nursesto fill critical shortages with less economic <strong>in</strong>vestment. Ethical concerns <strong>in</strong>clude the potentialfor exploitation <strong>of</strong> foreign nurses.Conclusions: <strong>Nurse</strong>s migrate to seek better wages <strong>and</strong> work<strong>in</strong>g conditions than they have <strong>in</strong>their native countries. Given the current conditions, developed countries cont<strong>in</strong>ue to activelyrecruit foreign nurses to fill critical shortages. <strong>Migration</strong> is predicted to cont<strong>in</strong>ue until developedcountries address the underly<strong>in</strong>g causes <strong>of</strong> nurse shortages <strong>and</strong> until develop<strong>in</strong>g countriesaddress conditions that cause nurses to leave.JOURNAL OF NURSING SCHOLARSHIP, 2003; 35:2, 107-111. ©2003 SIGMA THETA TAU INTERNATIONAL.[Key words: nurse migration, push <strong>and</strong> pull factors, nurs<strong>in</strong>g shortage, <strong>in</strong>ternational]* * *Ashortage <strong>of</strong> registered nurses (RNs) exists <strong>in</strong> countriesthroughout the world. Australia, Canada, France,Germany, Irel<strong>and</strong>, the United K<strong>in</strong>gdom (UK), <strong>and</strong>the United States (US)—all wealthy, <strong>in</strong>dustrialized countries—are but a few <strong>of</strong> the countries report<strong>in</strong>g nurs<strong>in</strong>g shortages.Cyclical nurse shortages <strong>in</strong> many countries have usually beenthe result <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased dem<strong>and</strong>s outpac<strong>in</strong>g the slower-<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gsupply <strong>of</strong> nurses (Buchan, 2001). The current shortage,however, appears more serious, with dem<strong>and</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g to<strong>in</strong>crease while the projected supply <strong>in</strong>dicates a cont<strong>in</strong>uedreduction <strong>in</strong> the availability <strong>of</strong> nurses, especially <strong>in</strong> the US<strong>and</strong> UK, countries that are primary dest<strong>in</strong>ations <strong>of</strong> migrat<strong>in</strong>gnurses.A survey conducted by the American Hospital Association(AHA) showed that the 715 U.S. hospitals surveyed posted168,000 open positions; <strong>of</strong> those positions, 126,000 or 75%were for RNs (AHA, 2001). A recent study <strong>in</strong>dicated theprojected gap between supply <strong>and</strong> dem<strong>and</strong> for RNs <strong>in</strong> the USto be 808,000 by the year 2020 (Bureau <strong>of</strong> Health Pr<strong>of</strong>essions,2002). The UK is grappl<strong>in</strong>g with similar nurse shortageproblems. The Royal College <strong>of</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>g listed the currentnumber <strong>of</strong> RN vacancies at about 22,000 <strong>and</strong> estimated thatthe National Health System (NHS) will need to recruit110,000 RNs by 2004 (F<strong>in</strong>alyson, Dixon, Meadows, & Blair,2002b).In addition to current shortage problems <strong>in</strong> the US, afundamental shift occurred <strong>in</strong> the RN workforce dur<strong>in</strong>g thelast 2 decades that has been predicted to substantially affectthe overall numbers <strong>of</strong> RNs available. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Buerhaus,Staiger, <strong>and</strong> Auerbach (2000), as the opportunities for womenoutside nurs<strong>in</strong>g exp<strong>and</strong>ed over the last 20 years <strong>in</strong> the US, thenumber <strong>of</strong> young women enter<strong>in</strong>g the RN workforce decl<strong>in</strong>ed.As a result, a demographic shift has occurred <strong>in</strong> the nurs<strong>in</strong>gworkforce. The decreased number <strong>of</strong> young people choos<strong>in</strong>gnurs<strong>in</strong>g careers has resulted <strong>in</strong> a gradually <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g averageage <strong>of</strong> nurses, <strong>and</strong> thus an ag<strong>in</strong>g RN workforce withoutcommensurate replacement <strong>of</strong> retir<strong>in</strong>g nurses. The authorspredicted that this ag<strong>in</strong>g will cont<strong>in</strong>ue over the next decadewhen the largest percentage <strong>of</strong> RNs will be <strong>in</strong> their 50s <strong>and</strong>60s, after which the RN workforce will become even smalleras the ag<strong>in</strong>g RNs retire.One means to alleviate the shortage crisis <strong>in</strong> developedcountries has been to recruit foreign nurses to fill vacantDonna S. Kl<strong>in</strong>e, RN, MN, <strong>Nurse</strong> Manager, Seattle Veterans Affairs PugetSound Health Care System, Seattle, WA. Correspondence to Ms. Kl<strong>in</strong>e,Seattle VAPSHCS—S-111, 1660 S. Columbian Way, Seattle, WA 98108. E-mail: doje@myuw.netAccepted for publication February 20, 2003.Journal <strong>of</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Scholarship Second Quarter 2003 107

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Nurse</strong> <strong>Migration</strong>positions. However, not only are representatives fromdeveloped countries recruit<strong>in</strong>g nurses, some <strong>of</strong> the samerecruit<strong>in</strong>g countries such as Australia, Canada, <strong>and</strong> the UKare los<strong>in</strong>g nurses through migration. The “bra<strong>in</strong> dra<strong>in</strong>” <strong>of</strong>nurses has come under <strong>in</strong>tense scrut<strong>in</strong>y <strong>in</strong> recent years withcompla<strong>in</strong>ts from people <strong>in</strong> donor countries such as India, thePhilipp<strong>in</strong>es, South Africa, <strong>and</strong> Zimbabwe about the loss <strong>of</strong>valuable human resources (“Record overseas numbers,” 2002).The purpose <strong>of</strong> this analysis was to explore these issuesregard<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>ternational migration <strong>of</strong> nurses:• the push-pull theory <strong>of</strong> migration;• identification <strong>of</strong> the major receiv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> donor countries;• effects <strong>of</strong> nurse migration on donor <strong>and</strong> receiv<strong>in</strong>gcountries; <strong>and</strong>• ethical considerations <strong>of</strong> nurse migration.The <strong>Push</strong>-<strong>Pull</strong> Theory <strong>of</strong> <strong>Migration</strong>Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Mejia, Pizurki, <strong>and</strong> Royston (1979), migrationis the result <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>terplay <strong>of</strong> various forces at both ends <strong>of</strong>the migratory axis. Some <strong>of</strong> these forces are political, social,economic, legal, historical, cultural, <strong>and</strong> educational. Theauthors classified the forces as “push” <strong>and</strong> “pull” factors.<strong>Push</strong> factors are generally present <strong>in</strong> donor countries, <strong>and</strong>pull factors perta<strong>in</strong> to receiv<strong>in</strong>g countries. Both forces mustbe operat<strong>in</strong>g for migration to occur. In addition, facilitat<strong>in</strong>gforces must be present as well, such as the absence <strong>of</strong> legal orother constra<strong>in</strong>ts that impede migration.K<strong>in</strong>gma (2001) discussed several reasons for nurse migrationthat constituted both push <strong>and</strong> pull factors. First, nursesmigrated <strong>in</strong> search <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional development that was notatta<strong>in</strong>able <strong>in</strong> their current job or country, demonstrat<strong>in</strong>geducational pull factors. The desire to practice nurs<strong>in</strong>g skillsmay have required mov<strong>in</strong>g from rural to urban areas or toanother country where opportunities existed for them to usetheir knowledge <strong>and</strong> skills. Second, nurses sought betterwages, improved work<strong>in</strong>g conditions, <strong>and</strong> higher st<strong>and</strong>ards<strong>of</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g not present <strong>in</strong> their native countries, exhibit<strong>in</strong>geconomic <strong>and</strong> social push <strong>and</strong> pull factors.Third, nurses sought areas to work where they wouldencounter less risk to their personal safety. Personal safety isan <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly strong political <strong>and</strong> social factor <strong>in</strong> nursemigration <strong>and</strong> “may be motivated by circumstances with<strong>in</strong>the health sector or the external environment” (K<strong>in</strong>gma, 2001,p. 207). <strong>Push</strong> factors such as concerns for personal safetyare evident <strong>in</strong> African countries with high rates <strong>of</strong> HIV<strong>and</strong> other <strong>in</strong>fectious diseases. For example, the WorldBank reported that Zimbabwe, a donor country, has one <strong>of</strong>the highest rates <strong>of</strong> HIV prevalence <strong>in</strong> the world, with26% <strong>of</strong> the population estimated to be <strong>in</strong>fected. In addition,the number <strong>of</strong> tuberculosis cases has <strong>in</strong>creased fivefold s<strong>in</strong>ce1995 (Zimbabwe: National Health Strategy Support, 1999).Not only does the AIDS epidemic place health workers suchas nurses at risk, the dem<strong>and</strong>s for care by nurses <strong>in</strong> theseareas are much greater than <strong>in</strong> countries with lowerprevalence rates.Global Movement <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nurse</strong>sDeveloped countries are the primary dest<strong>in</strong>ations <strong>of</strong> mostmigrant nurses. Australia, the UK, <strong>and</strong> the US are the countriesreceiv<strong>in</strong>g the largest number <strong>of</strong> migrant nurses. Australiareceived 11,757 foreign nurses between the years <strong>of</strong> 1995<strong>and</strong> 2000 (Hawthorne, 2001). Between 1995 <strong>and</strong> 2000, theU.S. Immigration <strong>and</strong> Naturalization Service (INS) reportedmore than 10,000 foreign nurses were admitted to the USunder H-1A visas (Immigration <strong>and</strong> Naturalization Service,2000). In the 4-year period between 1998 <strong>and</strong> 2002, the UKadmitted 26,286 foreign nurses <strong>in</strong>to the U.K. nurse registry(“Record overseas numbers jo<strong>in</strong> UK nurse register,” 2002).Countries such as Denmark, Norway, <strong>and</strong> Sweden generallyrecruit from other Nordic countries (Nurs<strong>in</strong>g WorkforcePr<strong>of</strong>ile 2002, 2002). Saudi Arabians have long depended onforeign nurses, with as many as 40 countries represented <strong>in</strong>the nurse workforce. Estimates <strong>of</strong> foreign nurses there rangefrom 83% to 95% <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>clude nurses <strong>in</strong> significant numbersfrom Australia, Canada, Indonesia, <strong>and</strong> the US (Aboul-Ene<strong>in</strong>,2002; Marrone, 1999).Although Japan has had a homogeneous nurse workforce,the Japanese rul<strong>in</strong>g Liberal Democratic Party recently approveda proposal to ease visa <strong>and</strong> residency regulations to <strong>in</strong>cludenurses (Lamar, 2002). Under current regulations, work<strong>in</strong>g visas<strong>in</strong> Japan are restricted to people deemed to have expertise <strong>in</strong>academic fields, technology, <strong>and</strong> journalism. The shift <strong>in</strong> policyis partially related to Japanese estimates that nearly 1 <strong>in</strong> 5 <strong>of</strong> its120 million people are over 65 years <strong>of</strong> age, <strong>and</strong> the percentageis rapidly <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g (Population Ag<strong>in</strong>g, 2002).The Table shows the major receiv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> donor countries.Major donor countries <strong>in</strong>clude Australia, India, Philipp<strong>in</strong>es,South Africa, <strong>and</strong> UK. The primary receiv<strong>in</strong>g countries areAustralia, Canada, Irel<strong>and</strong>, UK, <strong>and</strong> US.Table. Major Donor <strong>and</strong> Receiv<strong>in</strong>g Countries <strong>of</strong> Migrat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Nurse</strong>sReceiv<strong>in</strong>g Australia Canada Irel<strong>and</strong> UK USAcountriesDonor Ch<strong>in</strong>a Irel<strong>and</strong> Australia Australia Canadacountries Germany Philipp<strong>in</strong>es Philipp<strong>in</strong>es Canada Hong KongHong Kong UK UK F<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> JapanIndia South Africa Germany IndiaIrel<strong>and</strong> Ghana MexicoMalaysia Irel<strong>and</strong> NigeriaNew Zeal<strong>and</strong> India Philipp<strong>in</strong>esPhilipp<strong>in</strong>es Kenya Puerto RicoSouth Africa New Zeal<strong>and</strong> South KoreaSri Lanka Nigeria UKUK Pakistan VietnamPhilipp<strong>in</strong>esSouth AfricaSwedenUSAWest IndiesZambiaZimbabwe108 Second Quarter 2003 Journal <strong>of</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Scholarship

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Nurse</strong> <strong>Migration</strong>Not only are <strong>in</strong>dustrialized countries recruit<strong>in</strong>g from oneanother, develop<strong>in</strong>g countries also recruit nurses, <strong>of</strong>ten with<strong>in</strong>the same geographic area. For example, Caribbean <strong>and</strong>southern African countries recruit from each other (“Recordoverseas numbers jo<strong>in</strong> UK nurse register,” 2002). The number<strong>of</strong> foreign nurses admitted to the US is expected to <strong>in</strong>creasewith the proposed revision <strong>of</strong> immigration requirements(H-1C visas). The revisions would allow entry <strong>of</strong> foreign RNs<strong>in</strong>to the US to work <strong>in</strong> hospitals on a temporary basis <strong>in</strong>areas most acutely affected by the nurse shortage (“Senatepasses workforce legislation,” 2001).Effects <strong>of</strong> <strong>Migration</strong> on Donor <strong>and</strong> Receiv<strong>in</strong>g CountriesThe movement <strong>of</strong> nurses from donor to receiv<strong>in</strong>g countriescan create hardships <strong>in</strong> donor countries because <strong>of</strong> the loss <strong>of</strong>skilled personnel <strong>and</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> economic <strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>in</strong>education. The migration <strong>of</strong> nurses from develop<strong>in</strong>g countries,such as from African countries, results <strong>in</strong> the loss <strong>of</strong> “scarce<strong>and</strong> relatively expensive-to-tra<strong>in</strong> resources” (Buchan, 2001,p. 204). Many African countries have had significant <strong>in</strong>creases<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>and</strong> prevalence <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>fectious diseases such asAIDS, malaria, <strong>and</strong> tuberculosis, thus plac<strong>in</strong>g further dem<strong>and</strong>son already overburdened health care systems. The WorldHealth Organization (WHO) reported that at the end <strong>of</strong> 2000,25.3 million people <strong>in</strong> Sub-Saharan Africa had HIV/AIDS(WHO, 2000). Difficulties created by migration particularlyfrom the Sub-Saharan region come less from the loss <strong>of</strong> people<strong>in</strong> absolute numbers than from the loss <strong>of</strong> the few qualifiedpr<strong>of</strong>essionals (Ojo, 1990). The loss <strong>of</strong> nurses <strong>in</strong> this regionresults <strong>in</strong> even fewer skilled nurses, <strong>in</strong>creased care dem<strong>and</strong>son the nurses who rema<strong>in</strong>, <strong>and</strong> further deterioration <strong>of</strong><strong>in</strong>adequate health care systems.In addition to African countries, some other donor countriesalso have scarce nurse resources <strong>and</strong> can ill afford to losenurses to migration. WHO (1998) estimates showed thedistribution <strong>of</strong> health personnel per 100,000 <strong>of</strong> the population.Ch<strong>in</strong>a, India, <strong>and</strong> Pakistan <strong>in</strong>dicated 99, 45, <strong>and</strong> 34 nursesrespectively per 100,000 persons. In comparison, the USreported 972 nurses (for 1996), the UK reported 870 nurses(for 2000; Buchan & Seccombe, 2002), Australia reported830 nurses (for 1998), Canada reported 897 nurses (for 1996),<strong>and</strong> Irel<strong>and</strong> reported 1,593 nurses (for 1998) per 100,000persons.Reports from the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es are mixed regard<strong>in</strong>g effectson the health care system <strong>and</strong> the economy when largenumbers <strong>of</strong> nurses leave for other countries. The migration <strong>of</strong>Filip<strong>in</strong>o nurses is an example <strong>of</strong> the push factors <strong>of</strong> theeconomic conditions <strong>of</strong> oversupply, m<strong>in</strong>imal employmentopportunities, <strong>and</strong> the political factors <strong>of</strong> an aggressive exportpolicy (Hawthorne, 2001). Sison (2002) reported that Filip<strong>in</strong>ogovernment <strong>of</strong>ficials viewed the export<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> nurses as a newgrowth area for overseas employment. The 175 nurs<strong>in</strong>gschools <strong>in</strong> the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es produce more than 9,000 graduatesyearly, <strong>of</strong> whom 5,000 to 7,000 become licensed.Governmental encouragement for nurse migration isunderst<strong>and</strong>able, given the amount <strong>of</strong> money returned to thecountry <strong>in</strong> remittances. L<strong>in</strong>dquist (1993) reported over $800million received <strong>in</strong> remuneration per year from Filip<strong>in</strong>os liv<strong>in</strong>gabroad, money on which the Filip<strong>in</strong>o economy had becomehighly dependent. Filip<strong>in</strong>o nurses are sought <strong>in</strong> many Englishspeak<strong>in</strong>gcountries because <strong>of</strong> the Western-oriented nurs<strong>in</strong>gcurriculums with English as the primary <strong>in</strong>structive language,mak<strong>in</strong>g Filip<strong>in</strong>o nurses “marketable to foreign countries”(Ort<strong>in</strong>, 1990, p. 11).However, Prystay (2002) reported that nurs<strong>in</strong>g directors <strong>in</strong>the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es were greatly concerned about the high turnoverrates, with novice nurses staff<strong>in</strong>g hospital wards <strong>and</strong> operat<strong>in</strong>grooms. In addition to los<strong>in</strong>g experienced staff nurses, the<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Santo Tomas reportedly lost one-fourth <strong>of</strong> itsteach<strong>in</strong>g staff <strong>in</strong> 2001 to overseas hospitals. The Filip<strong>in</strong>o nurseswho rema<strong>in</strong> face (a) steep competition for jobs <strong>and</strong> poor wages,(b) little <strong>in</strong>centive from governmental health <strong>of</strong>ficials toimprove wages <strong>and</strong> work<strong>in</strong>g conditions, <strong>and</strong> (c) shortage <strong>of</strong>experienced nurs<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>structors.The effect on receiv<strong>in</strong>g countries is positive <strong>in</strong> that countriesreceive skilled nurses who can enter the workforce withm<strong>in</strong>imal preparation to fill critical shortages. On an averageday, the UK uses 20,000 temporary or agency nurses to fillshortage positions <strong>in</strong> hospitals, cost<strong>in</strong>g the NHS $1,235million USD a year (F<strong>in</strong>alyson, Dixon, Meadows, & Blair,2002a). In the US, agency nurses can earn $50 per hour or$104,000 per year. <strong>Nurse</strong>s who work as travel<strong>in</strong>g nurses canearn $75 per hour or $156,000 per year (Gamble, 2002). Thecost <strong>of</strong> employ<strong>in</strong>g foreign nurses is a much less expensivemethod <strong>of</strong> fill<strong>in</strong>g vacant positions. One hospital <strong>in</strong> Kentuckyrecently recruited 50 nurses from the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es at the cost<strong>of</strong> $300,000, which was roughly what the hospital paid foragency nurses for 1 month (Dooley, 2002).Nurs<strong>in</strong>g leaders <strong>in</strong> the US are concerned about the use <strong>of</strong>immigration as a means to address the nurs<strong>in</strong>g shortage.Glaessel-Brown (1998) reported that us<strong>in</strong>g foreign nurses as“readily available, expendable workers postpones susta<strong>in</strong>edefforts to resolve pr<strong>of</strong>essional problems lead<strong>in</strong>g to a morestable work force <strong>and</strong> self-susta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g cycles” (p. 327). In hertestimony before the House Education <strong>and</strong> WorkforceCommittee, Mary Foley (2001), then president <strong>of</strong> the American<strong>Nurse</strong>s Association, echoed Glaessel-Brown’s op<strong>in</strong>ion thatus<strong>in</strong>g foreign nurses to fill shortage positions only delayedaction on the serious workplace issues that have drivenAmerican nurses away from the pr<strong>of</strong>ession.Ethical ConcernsAs the level <strong>of</strong> migration <strong>in</strong>creases, the ethics <strong>of</strong><strong>in</strong>ternational recruitment warrant consideration. The<strong>International</strong> Council <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nurse</strong>s’ (ICN) position statement(ICN, 2002) <strong>in</strong>dicated the right <strong>of</strong> nurses to migrate, but italso acknowledged the adverse effects that migration mighthave on the quality <strong>of</strong> health care <strong>in</strong> donor countries. TheICN condemned the practice <strong>of</strong> recruit<strong>in</strong>g nurses to countrieswhere human resource plann<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> problems related toJournal <strong>of</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Scholarship Second Quarter 2003 109

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Nurse</strong> <strong>Migration</strong>retention <strong>and</strong> recruitment <strong>of</strong> nurses have not been addressed.The potential for exploitation <strong>of</strong> foreign nurses is <strong>of</strong> greatconcern. In 1998, six people <strong>in</strong> the US were charged withfraudulently obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g H-1A visas <strong>and</strong> us<strong>in</strong>g them to employFilip<strong>in</strong>o nurses as nurse aides rather than as registered nurses(Puente, 1998). In 1996, the Catholic Archdiocese <strong>of</strong> Chicagopaid $50,000 <strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>es <strong>and</strong> $384,700 <strong>in</strong> back pay to 99 Filip<strong>in</strong>onurses work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a Catholic nurs<strong>in</strong>g home. The nurses wereemployed as nurse aides (Allen, 1996). Filip<strong>in</strong>o nurses <strong>in</strong>Missouri were awarded $2.1 million for failure to receivecomparable wages as U.S.-born nurses <strong>in</strong> the same facility(Grimsley, 2000). Brubaker (2001) reported that someWash<strong>in</strong>gton, D.C. area hospitals <strong>of</strong>fered overseas nursessalaries that were less than those <strong>of</strong>fered to comparable U.S.nurses, by credit<strong>in</strong>g overseas nurses with only half <strong>of</strong> theiryears <strong>of</strong> experience. Reports also have <strong>in</strong>dicated that foreignnurses work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the US are restricted to less-desirable jobs,have to work <strong>in</strong> entry-level positions because they are notnaturalized citizens, <strong>and</strong> are excluded from jobs <strong>in</strong> lead<strong>in</strong>gfacilities (Glaessel-Brown, 1998).In the UK, foreign nurses have tended to fill entry-levelpositions (Hardill & MacDonald, 2000) <strong>and</strong> they earn muchless than do domestic nurses. In Irel<strong>and</strong>, a period <strong>of</strong> supervisedpractice <strong>and</strong> assessment can be required <strong>of</strong> foreign nurses,although qualified nurses from the EU, Australia, Canada,New Zeal<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> the US are exempt from the requirement.Foreign nurses not exempt are paid a wage equal to one-third<strong>of</strong> a 3rd-year student salary for the required period <strong>of</strong>supervised cl<strong>in</strong>ical nurs<strong>in</strong>g practice, after which they are paida salary commensurate with their verified nurs<strong>in</strong>g experience(Department <strong>of</strong> Health <strong>and</strong> Children, 2002). The period <strong>of</strong>supervised practice was not specified.F<strong>in</strong>ally, Mugera (2002) reported that the UK is consider<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>troduc<strong>in</strong>g compulsory HIV tests for all foreign health staffwork<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the country. The action is be<strong>in</strong>g considered afterhealth authorities found 10 nurses recruited from South Africawere HIV positive <strong>and</strong> they fear that more South Africannurses might carry the virus. In a newsletter, the <strong>Nurse</strong> <strong>and</strong>Midwifery Council’s (“HIV test for new NHS staff,” 2002)published view was that employees should be honest with theemployer <strong>and</strong> hav<strong>in</strong>g the virus should not affect a nurse’sability to practice. The potential for discrim<strong>in</strong>ation based ontest results could affect thous<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> African nurses who havebeen recruited to work <strong>in</strong> the UK.Strategies<strong>Push</strong> <strong>and</strong> pull factors exist between donor <strong>and</strong> receiv<strong>in</strong>gcountries, <strong>and</strong> nurses cont<strong>in</strong>ue to migrate <strong>in</strong> search <strong>of</strong> higherst<strong>and</strong>ards <strong>of</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> improved pr<strong>of</strong>essional opportunities.<strong>International</strong> strategies vary <strong>in</strong> response to some <strong>of</strong> theproblems created by nurse shortages <strong>and</strong> the result<strong>in</strong>g “bra<strong>in</strong>dra<strong>in</strong>” <strong>of</strong> nurses. The Australian Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Federation calledfor a national workforce plan that would <strong>in</strong>clude timely <strong>and</strong>consistent nurs<strong>in</strong>g workforce data (which has been severelylack<strong>in</strong>g) <strong>and</strong> the creation <strong>of</strong> a chief nurse role at the federallevel to advise on nurs<strong>in</strong>g issues (“Senate submission callsfor a national workforce plan,” 2002). The South AfricanGovernment proposed to the Commonwealth that recruitment<strong>of</strong> health pr<strong>of</strong>essionals from develop<strong>in</strong>g countries take placeonly with<strong>in</strong> formal bilateral agreements between richer <strong>and</strong>poorer nations. In the US, the ANA has resisted the passage<strong>of</strong> the Rural <strong>and</strong> Urban Health Care Act <strong>of</strong> 2001 that wouldexp<strong>and</strong> the exist<strong>in</strong>g H-1C visas to ease the immigration <strong>of</strong>foreign nurses (Trossman, 2002) out <strong>of</strong> concern thatimmigration “doesn’t address the underly<strong>in</strong>g problem thatdrives shortages—nurses’ deteriorat<strong>in</strong>g work<strong>in</strong>g conditions”(Trossman, 2002, p. 86). Buchan (2001) discussed severalstrategies be<strong>in</strong>g undertaken <strong>in</strong> the UK to address the migrationissue. The Department <strong>of</strong> Health <strong>in</strong> the UK established practiceguidel<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational recruitment for NHS employers.This attempt has had m<strong>in</strong>imal success, because it did not<strong>in</strong>clude the private sector recruiters or employers. A bilateralagreement was established between Great Brita<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> Spa<strong>in</strong>for Spanish nurses to work <strong>in</strong> the NHS for a def<strong>in</strong>ed period <strong>of</strong>time. The English-language Caribbean countries havedesigned a common approach to managed migration,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g compensation from receiv<strong>in</strong>g countries.<strong>Migration</strong> can be considered a freedom <strong>of</strong> choice <strong>and</strong> italso is an expected result <strong>of</strong> globalization. However, the extentto which the recruitment <strong>of</strong> foreign nurses is used to solve theshortage problem raises many questions about nurs<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong>health care. The UK, Australia, <strong>and</strong> Canada are import<strong>in</strong>gnurses to fill vacancies left by their own nurses migrat<strong>in</strong>gelsewhere, as well as to meet the <strong>in</strong>creased dem<strong>and</strong>s for nurses<strong>in</strong> their chang<strong>in</strong>g health care systems. In the US, changes <strong>in</strong>the health care system <strong>in</strong> the 1980s <strong>and</strong> 1990s have <strong>in</strong>creasedthe dem<strong>and</strong> for nurses; at the same time, decreased studentenrollments <strong>in</strong> nurs<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> the undersupply <strong>of</strong> nurs<strong>in</strong>g facultyfurther compound problems <strong>in</strong> produc<strong>in</strong>g an adequate supply<strong>of</strong> nurses.Address<strong>in</strong>g the nurse recruitment <strong>and</strong> retention issuescontribut<strong>in</strong>g to nurse shortages <strong>in</strong> developed countries seemsthe best strategy, but it is a long-term one. Aiken <strong>and</strong> colleagues(Aiken et al., 2001) reported on nurse surveys completed by43,000 nurses <strong>in</strong> five countries, three <strong>of</strong> which are majorreceiv<strong>in</strong>g countries, with different types <strong>of</strong> health care systems.These nurses reported similar <strong>in</strong>adequacies <strong>in</strong> their workenvironments <strong>and</strong> the quality <strong>of</strong> care provided. The authorsdescribed deficiencies on an <strong>in</strong>ternational scale <strong>in</strong> hospitalorganization, work design, <strong>and</strong> nurs<strong>in</strong>g care that have resultedfrom the restructur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> health care systems <strong>and</strong> hospitals that“emulate <strong>in</strong>dustrial models <strong>of</strong> productivity improvement” (p.51) but stopped short <strong>of</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g policies <strong>and</strong> benefits fornurses such as “opportunities for career advancement, life-longlearn<strong>in</strong>g, flexible work schedules, <strong>and</strong> policies that promote<strong>in</strong>stitutional loyalty <strong>and</strong> retention” (pg. 51). Buchan (2000)advocated use <strong>of</strong> “an evidence-based approach to identify whichflexible employment practices <strong>and</strong> pay <strong>and</strong> nonpay <strong>in</strong>centivesare effective <strong>in</strong> specific labor market conditions” (p.204) <strong>in</strong>promot<strong>in</strong>g improved job satisfaction <strong>and</strong> nurse retention.110 Second Quarter 2003 Journal <strong>of</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Scholarship

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Nurse</strong> <strong>Migration</strong>ConclusionsNurs<strong>in</strong>g shortages affect nurses, health care delivery, <strong>and</strong>populations worldwide. A wide range <strong>of</strong> factors contributesto nurse shortages <strong>and</strong> migration, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g political,economic, social, legal, historical, cultural, <strong>and</strong> educationalfactors. Many <strong>of</strong> those factors are beyond the scope <strong>of</strong> thisdiscussion. <strong>International</strong> migration <strong>of</strong> nurses is expected torema<strong>in</strong> high. While debates about nurse migration cont<strong>in</strong>ue,people from recruit<strong>in</strong>g countries should (a) actively exam<strong>in</strong>etheir own recruitment practices, (b) assure ethical treatment<strong>of</strong> foreign nurses, <strong>and</strong> (c) address the local problems thatcontribute to repeated shortages <strong>of</strong> nurses.ReferencesAboul-Ene<strong>in</strong>, F.H. (2002). Personal contemporary observations <strong>of</strong> nurs<strong>in</strong>gcare <strong>in</strong> Saudi Arabia. <strong>International</strong> Journal <strong>of</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Practice, 8,228-230.Aiken, L.H., Clarke, S.P., Sloane, K.M., Sochalski, J.A., Busse, R., Clarke,H., et al. (2001, May/June). <strong>Nurse</strong>s’ reports on hospital care <strong>in</strong> fivecountries. Health Affairs, 43-53.Allen, J.L. (1996, March 14). Archdiocese settles case on nurseunderpayments. Chicago Tribune, 2.American Hospital Association. (2001). AHA poll f<strong>in</strong>ds workforce shortagehurts hospitals now <strong>and</strong> will get worse. Retrieved December 1, 2002,from http://www.hospitalconnect.comBrubaker, B. (2001, June 11). Hospitals go abroad to fill slots for nurses;wide pay gap exists between US foreign workers <strong>in</strong> D.C. area. TheWash<strong>in</strong>gton Post, pp. A.1.Buchan, J. (2001). <strong>Nurse</strong> migration <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational recruitment. Nurs<strong>in</strong>gInquiry, 8(4), 203-204.Buchan, J. (2000). Plann<strong>in</strong>g for change: Develop a policy framework fornurs<strong>in</strong>g labor markets. <strong>International</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Review, 47, 199-206.Buchan, J., & Seccombe, I. (2002). Beh<strong>in</strong>d the headl<strong>in</strong>es: A review <strong>of</strong> theUK nurs<strong>in</strong>g labor market <strong>in</strong> 2001. Retrieved March 20, 2003, fromhttp://www.epolitix.com/data/companies/images/Companies/Royal-College-<strong>of</strong>-Nurs<strong>in</strong>g/edit2.htmBuerhaus, P.I., Staiger, D.O., & Auerbach, D.I. (2000). Implications <strong>of</strong>an ag<strong>in</strong>g registered nurse workforce. JAMA, 283(22), 2948-2954.Bureau <strong>of</strong> Health Pr<strong>of</strong>essions. (2002). Projected supply, dem<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong>shortages <strong>of</strong> registered nurses: 2000-2020. Health Resources <strong>and</strong>Services Adm<strong>in</strong>istration, U.S. Department <strong>of</strong> Health <strong>and</strong> HumanServices. Retrieved December 1, 2002, from http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/rnproject/report.htmDepartment <strong>of</strong> Health <strong>and</strong> Children. (2001). Atta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g full pr<strong>of</strong>essionalregistration. In Guidance for best practice on the recruitment <strong>of</strong> overseasnurses <strong>and</strong> midwives. Retrieved November 30, 2002, from http://www.doh.ie/publications/nurse/chap5.htmlDooley, K. (2002, July 13). Hospital imports nurses from the Philipp<strong>in</strong>esto alleviate shortage. Lex<strong>in</strong>gton Herald-Leader, A1.F<strong>in</strong>alyson, B., Dixon, J., Meadows, S., & Blair, G. (2002a). M<strong>in</strong>d thegap: The extent <strong>of</strong> the NHS nurs<strong>in</strong>g shortage. British Medical Journal,325, 538-541.F<strong>in</strong>alyson, B., Dixon, J., Meadows, S., & Blair, G. (2002b). M<strong>in</strong>dthe gap: The policy response to the NHS nurs<strong>in</strong>g shortage. BritishMedical Journal, 325, 541-544.Foley, M. (2001, September 25). Nurs<strong>in</strong>g shortage. Testimony toHouse Education <strong>and</strong> Workforce Committee, U.S. House <strong>of</strong>Representatives, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC. Retrieved April 14, 2003, fromhttp://edworkforce.house.gov/hear<strong>in</strong>gs/107th/fc/nurses92501/foley.htmGamble, D. (2002). Filip<strong>in</strong>o recruitment as a staff<strong>in</strong>g strategy. Journal<strong>of</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Adm<strong>in</strong>istration, 32(4), 175-177.Glaessel-Brown, E. (1998). Use <strong>of</strong> immigration policy to managenurs<strong>in</strong>g shortages. Image: Journal <strong>of</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Scholarship, 30, 323-327.Grimsley, K.D. (2000, June 22). Immigrant workers abused, EEOCsays; new agency suit alleges Hispanics were underpaid, mistreated byArizona firm. The Wash<strong>in</strong>gton Post, E2.Hardill, I., & MacDonald, S. (2000). Skilled <strong>in</strong>ternational migration: theexperience <strong>of</strong> nurses <strong>in</strong> the UK. Regional Studies, 34(7), 681-692.Hawthorne, L. (2001). The globalization <strong>of</strong> the nurs<strong>in</strong>g workforce: Barriersconfront<strong>in</strong>g overseas qualified nurses <strong>in</strong> Australia. Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Inquiry,8(4), 213-229.HIV test for new NHS staff. (2002, December 9). Retrieved April14, 2003, from http://www.nmc-uk.org/cms/content/News/HIV%20test%20for%20new%20NHS%20staff.aspImmigration <strong>and</strong> Naturalization Service. (2000) Table 37. Nonimmigrantsadmitted by class <strong>of</strong> admission 1995-2000. Retrieved April 14, 2003,from http://www.immigration.gov/graphics/shared/aboutus/statistics/Yearbook2000.pdf<strong>International</strong> Council <strong>of</strong> <strong>Nurse</strong>s. (2002). Position statement: <strong>Nurse</strong>retention, transfer <strong>and</strong> migration. Retrieved October 5, 2002, fromhttp//:www.icn.ch/psretention.htmK<strong>in</strong>gma, M. (2001). Nurs<strong>in</strong>g migration: Global treasure hunt or disaster<strong>in</strong>-the-mak<strong>in</strong>g.Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Inquiry, 8(4), 205-212.Lamar, J. (2000). Japan to allow <strong>in</strong> foreign nurse to care for old people.British Medical Journal, 320, 825.L<strong>in</strong>dquist, B. (1993). <strong>Migration</strong> networks: a case study <strong>in</strong> the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es.Asian <strong>and</strong> Pacific <strong>Migration</strong> Journal, 2(1), 75-102.Marrone, S.R. (1999). Nurs<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Saudi Arabia: Leadership development<strong>of</strong> a multicultural staff. Journal <strong>of</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Adm<strong>in</strong>istration, 29(7/8), 9-11.Mejia, A., Pizurki, H., & Royston, E. (1979). Physician <strong>and</strong> nursemigration: Analysis <strong>and</strong> policy implications. Geneva, Switzerl<strong>and</strong>:World Health Organization.Mugera, S. (2002). ‘HIV test for African nurses’ opposed. RetrievedNovember 30, 2002, from http//:news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/2198351.stmNurs<strong>in</strong>g Workforce Pr<strong>of</strong>ile 2002. (2002). <strong>International</strong> council <strong>of</strong><strong>Nurse</strong>s. Retrieved January 20, 2003, from http://www.icn.ch/SewDatasheet02.pdfOjo, K.O. (1990). <strong>International</strong> migration <strong>of</strong> health manpower <strong>in</strong> sub-Saharan Africa. Social Science Medic<strong>in</strong>e, 3(6), 631-637.Ort<strong>in</strong>, E.L. (1990, April-June). Ethics <strong>of</strong> bra<strong>in</strong> dra<strong>in</strong>: From the perspective<strong>of</strong> an export<strong>in</strong>g country. Philipp<strong>in</strong>e Journal <strong>of</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>g, 10-13,16.Population Age<strong>in</strong>g: 2002. (2002). United Nations. Retrieved February16, 2003, from http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/age<strong>in</strong>g/Graph.pdfPrystay, C. (2002, July 18). U.S. solution is Philipp<strong>in</strong>e dilemma: As recruiterssnap up more nurses, hospitals <strong>in</strong> Manila are scrambl<strong>in</strong>g. The WallStreet Journal. Retrieved November 30, 2002, from www.onl<strong>in</strong>ewsj.comPuente, M. (1998, January 15). Five plead guilty to nurse visa smuggl<strong>in</strong>g.USA Today, pp. 3.Record overseas numbers jo<strong>in</strong> UK nurse register. (2002). Australian Nurs<strong>in</strong>gJournal, 10(1), 16.Senate passes workforce legislation. (2001, October). HealthcareF<strong>in</strong>ancial Management, 23.Senate submission calls for a national workforce plan. (2002). AustralianNurs<strong>in</strong>g Journal, 9(10), 11.Sison, M. (2002, May 13). Exodus <strong>of</strong> nurses grows, health system feelseffect. Retrieved April 14, 2003, from http://www.manilatimes.net/national/2002/may/13/metro/20020513met5.htmlTrossman, S. (2002). The global reach <strong>of</strong> the nurs<strong>in</strong>g shortage: The ANAquestions the ethics <strong>in</strong> lur<strong>in</strong>g foreign-educated nurses to the UnitedStates. American Journal <strong>of</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>g, 102(3), 85-87.World Health Organization. (2000). Regional HIV/AIDS statistics <strong>and</strong>features, end <strong>of</strong> 2000. Retrieved April 14, 2003, from http://w3.whosea.org/hivaids/fact.htm#End-2000%20global%20estimatesWorld Population Prospects: The 2000 Revision: Highlights. (2001). NewYork: United Nations. Retrieved February 20, 2003, from http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/wpp2000/highlights.pdfZimbabwe: National Health Strategy Support. (1999). Retrieved January20, 2003, from http//:www.worldbank.org/pics/pid/zm3325.txtJournal <strong>of</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Scholarship Second Quarter 2003 111