A Multitude of Moths - New Hampshire Fish and Game Department

A Multitude of Moths - New Hampshire Fish and Game Department

A Multitude of Moths - New Hampshire Fish and Game Department

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

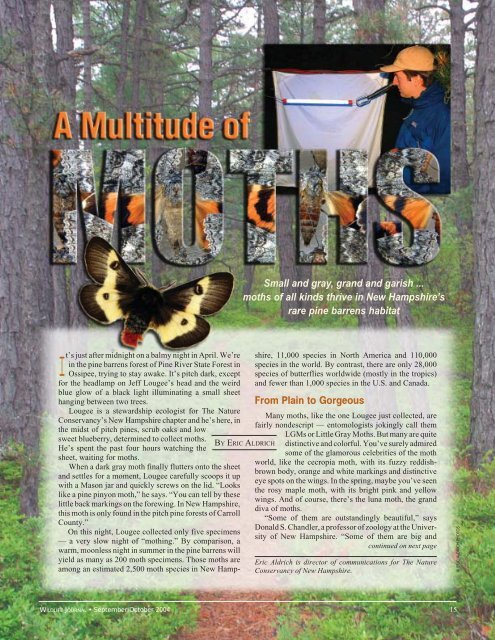

Small <strong>and</strong> gray, gr<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> garish ...moths <strong>of</strong> all kinds thrive in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>’srare pine barrens habitatBY ERIC ALDRICHIt’s just after midnight on a balmy night in April. We’rein the pine barrens forest <strong>of</strong> Pine River State Forest inOssipee, trying to stay awake. It’s pitch dark, exceptfor the headlamp on Jeff Lougee’s head <strong>and</strong> the weirdblue glow <strong>of</strong> a black light illuminating a small sheethanging between two trees.Lougee is a stewardship ecologist for The NatureConservancy’s <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> chapter <strong>and</strong> he’s here, inthe midst <strong>of</strong> pitch pines, scrub oaks <strong>and</strong> lowsweet blueberry, determined to collect moths.He’s spent the past four hours watching thesheet, waiting for moths.When a dark gray moth finally flutters onto the sheet<strong>and</strong> settles for a moment, Lougee carefully scoops it upwith a Mason jar <strong>and</strong> quickly screws on the lid. “Lookslike a pine pinyon moth,” he says. “You can tell by theselittle back markings on the forewing. In <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>,this moth is only found in the pitch pine forests <strong>of</strong> CarrollCounty.”On this night, Lougee collected only five specimens— a very slow night <strong>of</strong> “mothing.” By comparison, awarm, moonless night in summer in the pine barrens willyield as many as 200 moth specimens. Those moths areamong an estimated 2,500 moth species in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>,11,000 species in North America <strong>and</strong> 110,000species in the world. By contrast, there are only 28,000species <strong>of</strong> butterflies worldwide (mostly in the tropics)<strong>and</strong> fewer than 1,000 species in the U.S. <strong>and</strong> Canada.From Plain to GorgeousMany moths, like the one Lougee just collected, arefairly nondescript — entomologists jokingly call themLGMs or Little Gray <strong>Moths</strong>. But many are quitedistinctive <strong>and</strong> colorful. You’ve surely admiredsome <strong>of</strong> the glamorous celebrities <strong>of</strong> the mothworld, like the cecropia moth, with its fuzzy reddishbrownbody, orange <strong>and</strong> white markings <strong>and</strong> distinctiveeye spots on the wings. In the spring, maybe you’ve seenthe rosy maple moth, with its bright pink <strong>and</strong> yellowwings. And <strong>of</strong> course, there’s the luna moth, the gr<strong>and</strong>diva <strong>of</strong> moths.“Some <strong>of</strong> them are outst<strong>and</strong>ingly beautiful,” saysDonald S. Ch<strong>and</strong>ler, a pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> zoology at the University<strong>of</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>. “Some <strong>of</strong> them are big <strong>and</strong>continued on next pageEric Aldrich is director <strong>of</strong> communications for The NatureConservancy <strong>of</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>.© ERIC ALDRICH PHOTOSWILDLIFE JOURNAL • September/October 2004 15

© ERIC ALDRICH PHOTO© VICTOR YOUNG PHOTO© VICTOR YOUNG PHOTOJeff Lougee <strong>of</strong> The NatureConservancy sometimes collects asmany as 200 moth specimens in asingle night.Betterunderst<strong>and</strong>ing<strong>of</strong> moths will leadto better habitatmanagement.Cecropia mothPainted lady butterflycontinued from previous pagebeautiful, like the luna moth. Andsome <strong>of</strong> them are tiny <strong>and</strong> delicate<strong>and</strong> colorful.”The most beautiful, if you askCh<strong>and</strong>ler, are the so-called micros —so small you could fit four or five <strong>of</strong>them on a penny. Under a microscope,their splendor shines. B<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong>gold or silver. Patches <strong>of</strong> iridescentblue. Verydelicate, brilliant<strong>and</strong> littleunderstood.In fact, manyentomologistsdon’tbother collectingthem; they’re to<strong>of</strong>ragile, too hard to identify <strong>and</strong> too hard to preparefor collections.As curator <strong>of</strong> UNH’s insect collection, Ch<strong>and</strong>lerhas tediously identified <strong>and</strong> mounted hundreds<strong>of</strong> moths. Within the collection’s 700,000 insectspecimens — from beetles to flies — are some2,000 moth species. These are moths, mind you,not butterflies, which occupy a much smallernumber <strong>of</strong> nearby drawers.Moth orButterfly?Three micro mothson a dime.While there’s no foolpro<strong>of</strong> rule fordistinguishing moths <strong>and</strong> butterflies,both members <strong>of</strong> the orderLepidoptera, here are some clues:• <strong>Moths</strong> tend to rest with wings flat,while butterflies, with some exceptions,rest with wings folded upwardsover their back.• <strong>Moths</strong> tend to be nocturnal or dusk/dawn flyers, while most butterflies flyduring the day.• All moths have a bristle or bunch <strong>of</strong>bristles, called a frenulum, lockingthe forewing <strong>and</strong> hindwing together;butterflies don’t have this feature.• Most moths have tapering, featheryor hairlike antennae. Butterflies havea knob at the tip <strong>of</strong> the antennae.© ERIC ALDRICH PHOTOFrom Egg to MothButterflies <strong>and</strong> moths share a fairly similar lifehistory. Both go through four stages: egg, pupa,larva (or caterpillar) <strong>and</strong> adult. On reaching itslarval stage, a moth caterpillar will find a quietplace where it will make the transition to an adult.Some species spin a silk cocoon attached to abranch. Others make the transition underground,or go inside a folded leaf. Inside, the caterpillarbecomes a pupa <strong>and</strong> its body transforms into a sort<strong>of</strong> soup. Its metamorphosis into a moth can takedays, weeks or even months, depending on thespecies.Once emerged, the adult moth has four wings:two on top called forewings <strong>and</strong> two “hind” wingsunderneath. Most adult moths live only two weeksor so; others a few days or a few months. Andwhile some will eat during this time, others willnot, focusing instead on reproducing <strong>and</strong> avoidingpredators. Once the female lays eggs, there’slittle else for her to do.Much <strong>of</strong> the moth’s role in the ecosystem —especially among <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>’s species — isto eat, according to UNH’s Don Ch<strong>and</strong>ler. Only afew species here are pollinators. Most fill theirecological purpose as caterpillars ... eating <strong>and</strong>eating. They’re like little gardeners, he says. Eatingleaves <strong>and</strong> other pieces <strong>of</strong> plants stimulatesplants to grow. Other moth caterpillars help recyclethe soil by eating detritus.Habitats <strong>and</strong> <strong>Moths</strong>You can find moths virtually anywhere in <strong>New</strong><strong>Hampshire</strong>. Different habitats produce differentmoths, in both abundance <strong>and</strong> diversity. Oakforests, for instance, have a relatively huge variety<strong>of</strong> species <strong>and</strong> abundance <strong>of</strong> individual moths.Ch<strong>and</strong>ler has collected certain moths in theSeabrook s<strong>and</strong> dunes <strong>and</strong> others in silver mapleflood plain forests near Dalton. He’s collected232 species in Spruce Hole kettle bog near Durham.Some <strong>of</strong> the rarest moth species in the state arefound in the remnant pine barrens, such as thosein the Concord <strong>and</strong> Ossipee areas. According toDale Schweitzer, a <strong>New</strong> Jersey-based moth <strong>and</strong>butterfly expert with The Nature Conservancy,pine barrens (like those found from Maine throughthe Mid-Atlantic states) “are the habitat for global<strong>and</strong> regional moth rarities. Pitch pine/scrub oakbarrens are the place to look. There’s no otherhabitat that comes close to having the rarities.”In the Concord pine barrens, which is habitatfor the endangered Karner blue butterfly, Ch<strong>and</strong>lerhas collected some 578 moth species. N.H.<strong>Fish</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Game</strong> has also done scientific monitor-16 September/October 2004 • WILDLIFE JOURNAL

ing <strong>of</strong> moths, according to Celine Goulet, a biologistwith the <strong>Department</strong>’s Nongame <strong>and</strong>Endangered Wildlife Program. Better underst<strong>and</strong>ing<strong>of</strong> all the moths <strong>and</strong> butterflies in thisdistinctive habitat will lead to better management,Goulet said. And that may ultimately preventcommon moths from becoming uncommon <strong>and</strong>rare moths from vanishing altogether.Managing Moth HabitatsThe same is true for the Ossipee pine barrens.In the summer <strong>of</strong> 2002, University <strong>of</strong> Vermontgraduate students Claire Dacey <strong>and</strong> JonathanKart took an intensive look at the Ossipee, withDacey looking at the habitat <strong>and</strong> vegetation <strong>and</strong>Kart looking at the moths. The project was organized<strong>and</strong> sponsored by The Nature Conservancy,which has protected 2,000 acres in the Ossipeepine barrens since 1988. Seven hundred acres <strong>of</strong>that are classic pitch pine/scrub oak habitat.That summer, Kart collected more than 2,500individual moths, comprising 246 species. Ofthose, six species he collected are consideredrare. They have strange <strong>and</strong> exotic names, such asZanclognatha martha <strong>and</strong> Glena cognataria.Since Kart’s initial work, the Conservancy’s JeffLougee has done the follow-up collecting, gatheringmoths at times <strong>and</strong> places that Kart couldn’t.Thous<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> years ago, after the last Ice Age,pitch pines <strong>and</strong> scrub oaks sprouted from thes<strong>and</strong>y plains <strong>of</strong> what’s now Ossipee, Freedom,Madison, Tamworth <strong>and</strong> surrounding towns. Whathas long been part <strong>of</strong> that ecosystem is fire. Pitchpines thrive in fire-prone ecosystems becausetheir seeds can rapidly colonize <strong>and</strong> germinate insoils exposed by fire. And fire rejuvenates thesoil, clearing the way for the next growth <strong>of</strong> lowsweetblueberries <strong>and</strong> scrub oak. Fire keeps thedistinctive scattered openings <strong>of</strong> the pitch pine/scrub oak ecosystem.But there hasn’t been a good burn in theOssipee Pine Barrens for more than 50 years.Underst<strong>and</strong>ably so: there are homes <strong>and</strong> businessesthroughout this ecosystem. The NatureConservancy is preparing to carefully restore fireto this ecosystem starting in 2005. The plans arepainstakingly detailed <strong>and</strong> involve measuringfuel loads, creating fire breaks <strong>and</strong> devising plansfor controlled burns.“Fire will essentially go through <strong>and</strong> removeold, dead scrub oak <strong>and</strong> replace it with fresh,young growth,” Lougee said. “It’s that new growththat the caterpillars feed on. The sheer quantity<strong>and</strong> quality <strong>of</strong> the scrub oak goes up dramatically.Fire <strong>and</strong> mechanical treatment also open up thecanopy. The additional solar energy helps the cater-Know Your<strong>Moths</strong><strong>Moths</strong> come in many families orgroups, but most belong to just a few.There are the silk moths (Saturnidae)— medium to big moths, most <strong>of</strong> whichdo not feed as adults. Good examplesare the luna moth or the io moth.Then there are the sphinx moths(Sphingidae), which are probably theeasiest to recognize. They’re mediumto large <strong>and</strong> have long bodies. They’realso fast fliers; some hover <strong>and</strong> feedfrom flowers. Good examples are thefive-spotted hawk moth, the laurelmoth <strong>and</strong> the hummingbird moth.Another big group is the Arctiidae,which includes tiger moths. Somehave bright colors, a warning sign tobirds that they’re distasteful. And thereare the owlet moths (Noctuidae). Thisis the biggest family, with nearly 3,000species in North America. Most arenocturnal, like miniature owls. Manyhave a triangular shape, such as thecommon oak moth.There are a few others. Forinstance, even the casual moth observerwill recognize Lasiocampids,which include the tent caterpillarmoths. There are the tussock moths(Lymantriidae), which includes thenotorious gypsy moth; you may remembera horrendous outbreak <strong>of</strong>their caterpillars in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> inthe early 1980s. Needless to say,these prolific invaders do not requireany special habitat protections.pillars. So, after fire, there’s more food,better food <strong>and</strong> better habitat. What’s goodfor the caterpillars is good for the moths.”And in the long run, what’s good for the moths isgood for the special natural communities thatsustain them.Luna mothHummingbird mothCommon oak mothB<strong>and</strong>ed tussock mothGypsy moth caterpillar© VICTOR YOUNG PHOTO©ROGER IRWIN PHOTO© JOHN HIMMELMAN PHOTO© JOHN HIMMELMAN PHOTO© ERIC ALDRICH PHOTOWILDLIFE JOURNAL • September/October 2004 17