Download PDF - America

Download PDF - America

Download PDF - America

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

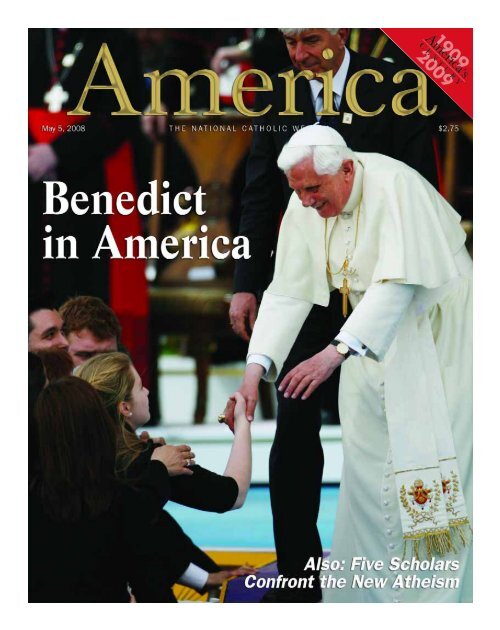

White House WelcomePope Benedict XVI blows out a candle on abirthday cake presented to him at the WhiteHouse on April 16.Pope Benedict XVI, meeting at theWhite House with President George W.Bush, said it was important to preservethe traditional role of religion in<strong>America</strong>n political and social life.Religious values helped forge “the soul ofthe nation” and should continue toinspire <strong>America</strong>ns as they face complexpolitical and ethical issues today, he said.The pope spoke April 16, his 81st birthday,at a ceremony on the South Lawn ofthe White House, where he was warmlywelcomed by the president and thousandsof cheering well-wishers. It was thepope’s first official encounter after arrivingin Washington, D.C., the day before.The pope smiled and beamed as thecrowd sang an impromptu “HappyBirthday.” The two leaders stood and listenedto their respective nationalanthems, then a fife and drum corpsplayed a medley of “Yankee Doodle” andother patriotic songs. The presidentgreeted the pope with the Latin phrasePax tecum (“Peace be with you”), and saidthe entire country was moved and honoredto have the pope spend “this specialday” with them.Benedict in <strong>America</strong>Pope Meets Privately WithVictims of AbusePope Benedict XVI held an unannouncedmeeting with victims of sexual abuse bymembers of the Catholic clergy, shortlyafter pledging the church’s continuedefforts to help heal the wounds caused bysuch acts. The Vatican said the pope metprivately in a chapel at the apostolic nunciaturewith “a small group of personswho were sexually abused by members ofthe clergy.” The group was accompaniedby Cardinal Sean P. O’Malley, O.F.M.Cap., of Boston, which was the center ofthe abuse scandal. “They prayed with theHoly Father, who afterward listened totheir personal accounts and offered themwords of encouragement and hope,” aVatican statement said. “His Holinessassured them of his prayers for theirintentions, for their families and for allvictims of sexual abuse,” it said. FedericoLombardi, S.J., the Vatican press spokesman,told journalists the meeting involvedfive or six victims, men and women fromthe Archdiocese of Boston, and lastedabout 25 minutes. During the encounter,each of the victims had a chance to speakpersonally to the pope, who spoke some“very affectionate words,” he said. Accordingto Father Lombardi, it was a veryemotional meeting; some were in tears.Dialogue Leads to TruthPope Benedict XVI encouraged interreligiousleaders to work not only for peacebut for the discovery of truth. The popeurged about 200 representatives of Islam,Jainism, Buddhism, Hinduism andJudaism at the Pope John Paul IICultural Center in Washington April 17“to persevere in their collaboration” toserve society and enrich public life. “Ihave noticed a growing interest amonggovernments to sponsor programsintended to promote interreligious dialogueand intercultural dialogue. Theseare praiseworthy initiatives,” PopeBenedict said. “At the same time, religiousfreedom, interreligious dialogueand faith-based education aim at somethingmore than a consensus regardingways to implement practical strategies foradvancing peace....The broader purposeof dialogue is to discover the truth,” hesaid. In a ceremony in the two-story mainlobby of the cultural center, Milwaukee’sAuxiliary Bishop Richard J. Sklba, chairmanof the U.S. bishops’ Committee onEcumenical and Interreligious Affairs,introduced the pope to the interreligiousleaders, who wore traditional garmentsidentifying their faiths.At New York Synagogue,‘Bridges of Friendship’The pope stands with former New York MayorEd Koch, left, and Rabbi Arthur Schneier at thePark East Synagogue in New York.In a brief and moving visit to a NewYork synagogue, Pope Benedict XVIexpressed his respect for the city’s Jewishcommunity and encouraged the buildingof “bridges of friendship” between religions.The encounter on April 18 markedthe first time a pope has visited a Jewishplace of worship in the United States,and occurred shortly before the start ofthe Jewish Passover. The pope said hefelt especially close to Jews as they “prepareto celebrate the great deeds of theAlmighty and to sing the praises of himwho has worked such wonders for hispeople.” He was welcomed at the ParkEast Synagogue by Rabbi ArthurSchneier, 78, who called the visit historicand “a reaffirmation of your outreach,good will and commitment to enhancingJewish-Catholic relations.” The rabbialso used the opportunity to wish thepope “mazel tov,” or best wishes on his81st birthday two days earlier. A choirfrom the Park East Day School performedduring the meeting, which waskept brief because the Jewish Sabbathobservance was to begin at sunset.4 <strong>America</strong> May 5, 2008

Benedict in <strong>America</strong>Human Rights Cannot Be Limited, Pope Tells U.N.Pope Benedict XVI touches a United Nations flag at theU.N. headquarters in New York April 18. The flag was flyingover the U.N. headquarters in Baghdad, Iraq, on Aug.19, 2003, when a truck bomb killed 17 people.Neither government nor religion has aright to change or limit human rights,because those rights flow from the dignityof each person created in God’simage, Pope Benedict XVI said in hisApril 18 speech to the U.N. GeneralAssembly. The pope insisted thathuman rights cannot be limited orrewritten on the basis ofnational interests or majorityrule. But he also said the roleof religions is not to dictategovernment policy, but tohelp their members strive tofind the truth, including thetruth about the dignity of allpeople, even if their religiousviews are different. U.N.Secretary General Ban Kimoonwelcomed the popeand met privately with himbefore the pope addressed theGeneral Assembly. In hispublic welcoming remarks,the U.N. leader said: “TheUnited Nations is a secularinstitution, composed of 192states. We have six officiallanguages but no official religion.We do not have achapel—though we do have ameditation room. But if you ask thoseof us who work for the United Nationswhat motivates us, many of us reply ina language of faith.... We see what wedo not only as a job, but as a mission.”He added, “Your Holiness, in so manyways, our mission unites us withyours.”where some 3,000 bishops, priests, religiousand seminarians gave him a standingovation. The crowd broke intoapplause when the pope’s secretary ofstate, Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone, delivereda Spanish-language “happy anniversary”message and wished the pontiffmany more years. The pope took themicrophone and, looking out on the seaof faces in the neo-Gothic cathedral,smiled and spoke in a soft voice. “I canonly thank you for your love of thechurch, for the love of our Lord and thatyou give also your love to the poor successorof St. Peter,” he said. “I will do allthat is possible to be a real successor ofthe great St. Peter, who also was a manwith his faults and some sins, but heremains finally the rock for the church,”he said.At Ground Zero, SolemnPrayer and ComfortYoung Adults EnjoyImpromptu MeetingSeveral hundred young adults holding avigil behind the security perimeteraround the house in New York Citywhere Pope Benedict XVI was stayingwere rewarded April 18 with a papalhandshake. Helen Osman, director ofcommunications for the U.S. Conferenceof Catholic Bishops, said more than1,000 people had gathered throughoutthe evening near the residence of theVatican’s permanent observer to theUnited Nations, where the pope wasstaying. “Some just came out of curiosity,”but there were also others, playingguitars and drums. The young peoplefrom three New York parishes had beengathered by the Sisters of Life of NewYork, the order founded by the lateCardinal John O’Connor to promote the“Gospel of life.” At about 8 p.m. the U.S.Secret Service began allowing smallgroups to pass the traffic blockade andapproach the residence. Pope Benedictcame outside “after dinner” at about 9p.m., said Federico Lombardi, S.J., theVatican spokesman. The pope spentabout 10 minutes shaking hands withyoung religious and other young adultswho got the Secret Service nod.<strong>America</strong>ns Thanked forTheir Love and PrayersDescribing himself as “the poor successorof St. Peter,” Pope Benedict XVIthanked <strong>America</strong>ns for their prayers andlove on the third anniversary of his election.The pope made the imprompturemarks at the end of a Mass April 19 inSt. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York,Pope Benedict XVI offers prayers at groundzero in New York.In the most somber moment of his sixdayvisit to the United States, PopeBenedict XVI knelt alone at ground zeroand offered a silent prayer. The cheeringcrowds were far away as the popeblessed the ground where the WorldTrade Center stood until terroristscrashed airplanes into its twin towers onSept. 11, 2001. While the extraordinarysecurity measures that surrounded theMay 5, 2008 <strong>America</strong> 5

Benedict in <strong>America</strong>pope’s entire visit tangibly demonstratedhow the attacks have changed theUnited States, the ground zero visit gavethe pope an opportunity to speak to andconsole those whose lives were changedmost directly that day. Twenty-fourpeople stood around a candle, a plot ofearth and a tiny pond as the pope kneltin prayer, including family members ofthose killed, some of the survivors andrepresentatives of the first respondersfrom the New York Port Authority,police and fire departments. At the bottomof the 70-foot crater where thetowers had stood, surrounded by steelconstruction rods, forklifts and steelbeams, Pope Benedict looked up pastthe skyscrapers shrouded in fog and reada prayer.Pope Meets WithTheologian Avery DullesDuring his whirlwind U.S. visit, PopeBenedict XVI took a few moments outfor a private meeting with one of<strong>America</strong>’s preeminent theologians,Cardinal Avery Dulles, S.J. Thewheelchair-bound scholar traveled fromhis residence at Jesuit-run FordhamUniversity’s Rose Hill campus in theBronx to St. Joseph’s Seminary inYonkers, N.Y., April 19, for a prearrangedprivate meeting with the pope,just after the pontiff met with disabledyouths. “It was a lovely meeting,” saidAnne-Marie Kirmse, O.P., who has beenthe cardinal’s executive assistant for thepast 20 years. She was present to helpfacilitate the get-together, held at theseminary. “The pope literally boundedinto the room with a big smile on hisface,” she told Catholic News Service onApril 21. “He went directly to whereCardinal Dulles was sitting, saying,‘Eminenza, Eminenza, Eminenza, I recallthe work you did for the InternationalTheological Commission in the 1990s.’”States amid a cheering crowd of 4,000people who had come to see him off.“It has been a joy for me to witness thefaith and devotion of the Catholiccommunity here,” the pope said April20 in brief remarks to those gatheredin Hanger 19 at John F. KennedyInternational Airport. “It was heartwarmingto spend time with leadersand representatives of other Christiancommunities and other religions,”Pope Benedict added. Among thosepresent were Cardinal Edward M.Egan of New York; Bishop William F.Murphy of Rockville Centre;Archbishop Pietro Sambi, apostolicnuncio to the U.S.; and BishopNicholas DiMarzio of Brooklyn, whosediocese includes the airport. Also inattendance were Mayor MichaelBloomberg of New York and VicePresident Dick Cheney and his wife,Lynne. “It has been a memorableweek, and Pope Benedict XVI hasstepped into the history of our countryin a special way,” Cheney said.Multicultural Mix ofAncient and ModernThe liturgical celebration of Mass byPope Benedict XVI on April 17 inNationals Park reflected the diversity ofCatholic heritages and sensibilities foundin the Archdiocese of Washington, D.C.,where the Mass was held. It acknowledgedboth the roots of tradition and thebranches that have sprouted from thoseroots. The prayer of the faithful wasrecited in six languages—English,Spanish, Korean, Vietnamese, Tagalogand Igbo. The sung response to theintentions incorporated three languages:English, Latin and Spanish. The firstreading—the account of how the apostlesstarted speaking in tongues unknownto them at Pentecost—was proclaimed inSpanish. Music composed in the 40 yearssince the conclusion of the SecondVatican Council was included, as wereancient Latin texts set to chant—and aLatin-language Gloria written in the pastdecade.Pope Reaches out to Disabled ChildrenFaith of U.S. Catholics‘A Joy to Witness’Thanking <strong>America</strong>ns for their hospitality,Pope Benedict XVI left the UnitedFrom CNS and other sources. CNS photos.Pope Benedict XVI greets a girl during a gathering with young people with disabilities at St.Joseph’s Seminary in Yonkers, N.Y., on April 19.6 <strong>America</strong> May 5, 2008

EditorialPastor and ProphetTHE ENDURING IMPRESSION Pope BenedictXVI left with most <strong>America</strong>ns followinghis recent visit to Washington, D.C., andNew York was of a pastor ministering tohis flock. In repeated gestures, from meetingwith the victims of sexual abuse to blessing the disabledand speaking with the survivors of the terroristattacks of Sept. 11, 2001, he showed his desire to healthose who are wounded and broken.His numerous comments on sexual abuse by membersof the clergy demonstrated awareness of the depth of thehurt to victims and their families as well as to the<strong>America</strong>n Catholic Church as a whole. From his confessionof shame to reporters during the flight to the UnitedStates to his spontaneous acknowledgment of his ownhuman weakness at the Mass at New York’s St. Patrick’sCathedral, he signaled that like Peter, he is an ordinaryChristian who struggles to be a disciple.Though commentators have often depicted hisGerman heritage as a source of rigidity and heavyhandedness,Benedict’s Bavarian Gemütlichkeit revealed itself witha relaxed smile, and it projected warm joy throughout hispublic appearances. His natural graciousness enabled himto look those he encountered in the eyes and to listen tothem attentively. Though he is known to prefer more traditionalliturgical styles himself, he appeared to relish themultilingual, multiethnic liturgical events prepared forhim, which are so characteristic of the United States today.His prayer at ground zero was a gem of quiet commemoration,and the visit to the Park East Synagogue on the eveof Passover was a gesture of undiminished goodwill towardthe Jewish community.Just as he came to heal, Pope Benedict also came tounify. His homilies and addresses allowed no gloating byone church faction over another. In addressing the bishops,for instance, he balanced pro-life issues with socialjustice concerns. “Is it consistent,” he asked, “to professour beliefs in church on Sunday, and then during the weekto promote business practices or medical procedures contraryto those beliefs? Is it consistent for practicingCatholics to ignore or exploit the poor and marginalized,to promote sexual behavior contrary to Catholic moralteaching, or to adopt positions that contradict the right tolife of the human being from conception to naturaldeath?” Though Pope Benedict’s critique of <strong>America</strong>n culture—ofindividualism, secularism, materialism and thecult of untrammeled freedom—was clear, his reproof wasconsistently gentle: questioning rather than condemning,edifying rather than hectoring.With his gentle voice and peaceful demeanor, Benedictdid not fail to offer a prophetic word to the world. At theUnited Nations General Assembly, he upheld the necessityof the organization for the defense of human rights andgave new prominence to “the duty to protect,” that is, theresponsibility of the international community to intervenewhen a government either fails to protect its own peopleor is itself guilty of violating their rights. He made clearthat the United Nations serves human solidarity by makingthe strong responsible for defending the weak.Pope Benedict also extrapolated a seldom discussedteaching of Pope John XXIII in the encyclical Pacem inTerris—that the legitimacy of governments depends ontheir respect for and defense of the rights of their people.It is not “intervention,” he argued, that should be interpretedas “a limitation on sovereignty,” but rather “nonintervention”that causes harm out of indifference to the victimsof oppression. With international missions founderingin long-lasting conflicts like those in Congo andSudan, however, the pope’s remarks place the burden onthe international community to build the capacity to dealwith major humanitarian emergencies.WHILE POPE BENEDICT SHOWED APPRECIATION for <strong>America</strong>n culture,especially for the flowering of liberty, and for U.S.Catholics, he also laid bare our temptations and failings.He spoke to young people about the “callousness of heart”that leads to “drug and substance abuse, homelessness,poverty, racism, violence and degradation—especially ofgirls and women.” He also warned against relativism,“which, in disregarding truth, pursues what is false andwrong,” leading to “addiction, to moral or intellectual confusion,to hurt, to a loss of self-respect, even to despair....”This portrait is unflattering. <strong>America</strong>ns may find ithard to look in the mirror Benedict held up to us. We maywant to avert our eyes. But the challenge of the visit is tolearn from Pope Benedict’s criticism as well as his praise,take it to heart and find new ways to redeem the shadowside of our <strong>America</strong>n character. For, as he reminded us,with our eyes fixed on the saints whose lives enable us to“soar freely along the limitless expanse of the horizon ofChristian discipleship,” we too can live the Gospel life in21st-century <strong>America</strong>.May 5, 2008 <strong>America</strong> 7

Morality MattersAgainst All Odds‘In Eastern Congo, motherhoodis still a risky business.MOTHERHOODdemandsrisk, personal danger andcourage. When Marysaid yes to life, to becomingthe mother of God,she risked everything. As a young, unwedmother in a patriarchal society, she riskedlosing her family, her place in the communityand thus her means of survival.Joseph’s first instinct to the news of herpregnancy was to break with her, untilangels interceded and the Holy Familywas begun.As we celebrate the month of Maryand Mother’s Day, motherhood is still arisky business. For the women of EasternCongo, where atrocities against womenare routinely committed, motherhoodrequires great courage. In the past 10years 5.4 million people have died fromthe war and violence in the DemocraticRepublic of Congo; 47 percent of theseare children. In a huge country, the sizeof the United States east of theMississippi, rebel groups supported byforeigners fight with each other and thegovernment, largely over the D.R.C.’srich natural resources.“Conflict coltan” mines in EasternCongo are particular targets, as coltan isused in our cell phones, laptops and computerchips. Rwanda’s génocidères remainin Eastern Congo, where they and otherscontinue their brutality. The largely collapsedD.R.C. is at best unable to protectpeople; at worst the untrained and unpaidtroops and police themselves prey on thepeople.Women and children suffer most.Alan Goss, the U.N. special representativeto the D.R.C., laments that the rates ofinfant and maternal mortality in Congoare among the worst in the world. InMARYANN CUSIMANO LOVE serves on theadvisory board of the CatholicPeacebuilding Network.‘Eastern Congo, with its coltan mines andforeign fighters, violence continues longafter peace accords have been signed.Women are routinely raped andmutilated as an instrument of war, as documentedby the U.N. special rapporteuron violence against women, Ms. YakinErturk. She notes, “The scale and brutalityof the atrocities amount to war crimesand crimes against humanity.” Girls asyoung as 5 and grandmothers as old as 80are not immune to gang rapes, some ofthem committed with tree limbs, guns ormachetes. Mothers are raped while theirhusbands and children are tied to treesand forced to watch. In many cases thevictims are shunned, blamed for theattacks on them, because the rapes humiliatethe family, or because they are infectedby the attacks with H.I.V./AIDS andother diseases, or because many areimpregnated with the children of thesecriminals and enemies.Although the D.R.C. made rape andviolence against women illegal in 2006,few perpetrators are ever arrested or prosecuted.The filmmaker Lisa Jacksonshows in “The Greatest Silence,” a chillingrecent HBO documentary, theimpunity of these rapists, who brag oncamera of their crimes.What do women do in the midst ofsuch horrible suffering? They try to raisetheir children and hold their familiestogether, against all odds. They see theseoffspring of rape not as children of theenemy, but as children of God.Archbishop Francois-Xavier Maroygrew up in these areas and now presidesthere. His three predecessors were murdered.He was recently in the UnitedStates to attend Catholic PeacebuildingNetwork conferences, and to urge actionby the U.S. government, in particular bySenators Sam Brownback and JosephBiden and Congressman Barney Frank,who are promoting legislation on theseissues. “All of humanity are attacked whenwomen are attacked,” he said, and continued:“Women are sacred, the mothers oflife, the pillars of the family, she that educatessociety through her children. Theseare attacks against the whole human family,aimed at the extermination of theCongolese people of the east.”He explained that with the collapse ofthe state almost all social services are providedby the church, from trauma healingto health care. But this is difficult to do,and resources are scarce. For women withmore severe injuries, there is only onedoctor able to treat them, Dr. Mukwege ofthe Panzi Hospital in Bukavu. Accordingto the archbishop:We work on reintegration of thewomen back into families andsocieties, and in the reintegrationof their children. The problem isthat after rape they are marginalizedby their own family members,evicted and their household goodsstolen as well, so the church triesto give other means to establishlives and become useful again. Wealso work with the children whoare born of these rapes, as they areinnocent victims too.What we would ask the<strong>America</strong>n church is first, for yourprayers. Prayer is the strongestforce, and can change hearts ofstone to hearts of flesh. Second,we ask <strong>America</strong>n Catholics to tellthe U.S. government, which is thefirst power of the world, to help usbring peace back to Congo, and towork to return the Rwandan fightersback to Rwanda. We ask thatthe U.S. government be a forcefor reconstruction, not destruction.And third, we ask for financialassistance as well.Despite the suffering of the people towhom Archbishop Maroy ministers everyday, he maintains a positive outlook andgentle smile. “As a church, we must alwayskeep hope and never be discouraged.”This May, let us pray together with thepeople of Congo, “Deliver us Lord fromevery evil, and grant us peace in our day.”Maryann Cusimano LoveMay 5, 2008 <strong>America</strong> 9

May 5, 2008 <strong>America</strong> Vol. 198 No. 15, Whole No. 4814T h e N e w A t h e i s mIn recent years religious fundamentalism and disputesover the relationship between faith and science haveprovoked a wave of publications known collectively as“the new atheism.” Following the Second VaticanCouncil’s observation that “believers can have morethan a little to do with the rise of atheism,” the editorshave asked five prominent theologians to explorewhich expressions of contemporary Christianity supplywhat the council called “the secret motives” ofatheism. We also asked our experts to reflect on howChristians might respond to both the legitimate criticismsoffered by the new atheism and the distortionsof faith found within it.May 5, 2008 <strong>America</strong> 11

Catholicism andThe New AtheismBY RICHARD R. GAILLARDETZRICHARD R. GAILLARDETZ is the Thomas and Margaret Murrayand James J. Bacik Professor of Catholic Studies at theUniversity of Toledo.ONE OF THE LESS NOTED contributions of theSecond Vatican Council is its brief treatmentof atheism in its “Pastoral Constitution onthe Church in the Modern World.” In thatgroundbreaking document, the council avoided the shrillcondemnations of atheism that were so common in preconciliartexts. Instead, the council acknowledged thediverse motives for modern atheism, from the overreachingclaims of the positive sciences to modern atheism’slegitimate rejection of “a faulty notion of God” (No. 19).The bishops invited Christians to go beyond condemnationand “seek out the secret motives that lead the atheisticmind to deny God” (No. 20). By way of contrast, theso-called “new atheists”—figures like Richard Dawkins,Daniel Dennett, Christopher Hitchens and SamHarris—engage in an aggressive and decidedly nondialogicalattack on religion. They insist that religion is fundamentallytoxic to human society and must be directlychallenged and eradicated where possible. Consider thesecond part of the title of Hitchens’s volume, God is NotART BY STEPHANIE RATCLIFFE12 <strong>America</strong> May 5, 2008

Great: How Religion Poisons Everything.Islamic and Christian fundamentalism receive the lion’sshare of criticism, but Catholicism does not escape attack.Harris skewers Catholicism for its anti-Semitic history, theevils perpetrated by the Spanish Inquisition and theCatholic leadership’s scandalous protection of clerical childabusers. Hitchens joins Harris in mentioning the scandal ofsexual abuse but also lampoonsCatholicism for itsWe must ask ourselveswhether there is anything inour Catholic culture thatinvites these attacks andmight be avoided withoutabandoning what is essentialto our faith.supposed reliance onsuperstition and condemnsits pursuit of power inorder to control the livesof others. Almost all ofthese critics challengeCatholicism’s dogmatismand overbearing exerciseof authority, which theysee as directly opposed tothe use of human reasonand the primacy of conscience.The committed Catholic(indeed, the committed practitioner of any great religioustradition) is bound to bristle at the aggressive tone andthe tendency toward caricature and sweeping generalizationthat runs through these works. It is tempting simply to dismissthese attacks. Yet the Second Vatican Council’s mandatefor respectful engagement with the critics of faithinvites an alternative course of action. We must certainlydefend the integrity and reasonableness of our deepest religiousconvictions, but an adequate Catholic response mustgo beyond traditional apologetics; we must also ask ourselveswhether there is anything in our Catholic Christianculture that invites these attacks and might be avoided withoutabandoning what is essential to our faith. I focus onthree elements in the Catholic faith that call for our attention:Catholic practices that suggest a naïve theism; thenature of Catholic truth claims; and the exercise of churchauthority.Naïve TheismAs Michael Buckley, S.J., pointed out in his classic study ofatheism (At the Origins of Modern Atheism), all forms of modernatheism are parasitic upon a particular form of theism.The proponents of the new atheism presuppose a naïveform of theism that perceives God, as Karl Rahner put it, asan individual being, albeit the Supreme Being, who is simplyanother “member of the larger household of reality”(Foundations of Christian Faith). Yet the god of this naïve theismmore closely resembles a benevolent Zeus than the godof the Judeo-Christian tradition. One imagines a god standingon the sidelines of human history but occasionally interveningin the course of human events. Still, we should askourselves whether there are popular Catholic beliefs orpractices that may, however unintentionally, support suchnaïve theism.As one example, consider the procedures for the canonizationof saints. Vatican regulations require that for beatificationone verified miraclebe attributable to the“servant of God”; for canonizationtwo arerequired. In these rules,miracles are described asevents attributed to theintercession of the servantof God and certified asinexplicable according tomodern science. Withoutdenying the possibility ofsuch events, I wonderwhether the emphasis ontheir scientifically inexplicablecharacter risks givingthe impression that God’s action in the world cannot bereconciled with a scientific account of the workings of ourphysical universe. Does this interventionist view of divineaction invite accusations of superstition and caricatures ofdivine activity by those outside the community of faith? It isvital that our religious beliefs and practices affirm a fundamentalcompatibility between divine action and scientificaccounts of our world.It may be opportune to consider revised procedures thatwould focus less on the scientifically inexplicable and moreon diverse testimony to the continuing influence and impactof the servant of God on those who remain on their earthlypilgrimage. Pope Benedict’s recent encyclical on hopemakes effective use of the lives of select saints as movingembodiments of Christian hope. I suspect that it is thisevangelical witness rather than the verification of miraculousinterventions that the contemporary skeptic is morelikely to find compelling.Catholic Truth ClaimsWe have not been left on this earth to wander blindly insearch of the divine. Catholics believe that God communicatesthe divine self to us in revelation. This revelation hasbeen mediated in various forms throughout human historyand has achieved its unsurpassable form in the person ofJesus of Nazareth. The Spirit-inspired testimony to thisdivine revelation is found in Holy Scripture and continuesto unfold in the tradition of the church. Within that tradition,the revealed message of God’s offer of salvation hasMay 5, 2008 <strong>America</strong> 13

een given formal expression in dogma.Unfortunately, the presentations of church teaching thatone sometimes hears from catechists and clergy can succumbto what Juan Luis Segundo, S.J., has called a “digital”view of dogma (The Liberation of Dogma). This understandingdivests dogma of its analogical, imaginative and transformativecharacter and renders it strictly informational.One can easily get the impression that by learning churchdogma one has somehow “mastered” God, much as a chemistrystudent masters the periodic table. Presentations basedon a fundamental misunderstanding of the gift of infallibilitycan create the impression that Catholic dogma is static,as if the very language of dogmatic statements is immune tohistorical, philosophical or cultural influence.For Catholics, dogmatic statements symbolically mediaterevelation without exhausting our encounter with God.Although dogmas play a valid role by affirming the truth ofour most central convictions, they are not the only, nor evennecessarily the primary way in which we encounter divinerevelation. The narrative power of Scripture, the symbolicefficacy of the liturgy, the moving testimony of the lives ofsaints and ordinary believers—all of these can mediateGod’s word to us. Moreover, the charism of infallibility,which Catholics hold is active when the church believes andteaches that which is central to the divine offer, does notexempt church teaching from reasoned inquiry and critique.Catholic teaching on infallibility proceeds from our confidencethat the Spirit of God so abides in the church that ourmost central convictions about God are utterly reliable andwill not lead us away from God’s saving offer. Insofar as theyremain human statements, subject to the limits of languageand history, dogmatic pronouncements, although not erroneous,are always subject to reformulation. No human statement,however much its formulation may be assisted by theSpirit and protected from essential error, can capture theholy mystery of God. Religious authority figures shouldresist presenting dogma as if it brought all theologicalreflection to a close.The church’s teachers should also continue to acknowledge,clearly and without apology, that not all official churchteaching has the status of dogma. In many instances theteaching office of the church proposes as formal churchteaching or binding church discipline its best insight, hereand now, regarding the application of the faith to often complexissues, even as it acknowledges the possibility of error.Pope Benedict has noted that in today’s world the possibilityof revealed truth is itself under attack. If that is thecase, then the church has a particularly pressing obligationto offer a credible account of divine revelation. For thisaccount to be credible, it should include the following threepoints: the acknowledgment that church dogma does notexhaust the holy mystery of God; the recognition thatchurch dogma, although not erroneous, is not exempt fromthe linguistic and philosophical limits to which all humanstatements are subject; and the unambiguous admission thatnot all church teaching is taught with the same degree ofauthority and that noninfallible teaching remains open tosubstantive revision. These steps might go a long waytoward thwarting the tendency of the church’s critics tolump Roman Catholicism together with the various religiousfundamentalisms that succumb to simplistic andseemingly irrational conceptions of divine truth.Church LeadershipThe Catholic Church is a human institution that hasalways embraced the need for authoritative church structures.Yet often it is not church authority itself, but theparticular manner in which church authority is exercisedthat opens the Catholic Church to such harsh attacks fromcontemporary critics. Many who observe the CatholicChurch from the “outside” see an institution prone toheavy-handed and arbitrary wielding of authority. Theysee ecclesiastical pronouncements on complex ethicalissues and wonder how church officials can pronounce onthem with such certitude. Some outside the church see anunwillingness on the part of church leadership to considerthe wisdom of ordinary believers or to entertain theinsights of contemporary scholarship when these insights14 <strong>America</strong> May 5, 2008

might challenge official church positions. They also seetoo many church leaders obsessed with the trappings ofrank and privilege, titles and prerogatives, leaders more athome in the court of a 19th-century monarch than in amodern institution. There are, of course, many Catholicleaders whose style of leadership is far removed from thesestereotypes, but they are often better known to thoseinside the church than to those outside.If truth be told, the deepest wisdom of our great traditionpresents a vision of church authority often at odds withchurch practice. Scripture teaches that authentic churchauthority is always to be exercised as a service, not as aninstrument for control (Mt 20:25-8). Voices within our traditionlike St. Paulinus of Nola or Cardinal Newman haveinsisted that church leaders consult the faithful, not becauseit was politically correct to do so but because of an ancientconviction that the Spirit of God might speak through thewhole people of God. We can appeal to great figures of thepast like St. Augustine and Pope Gregory the Great or tothe more recent teaching of Vatican II and find remindersthat the exercise of church authority must be subject tohumility. This humility presupposes that we belong to a pilgrimchurch that is being led by the Spirit but that has notyet arrived at its final destination and is therefore always inneed of reform and renewal.Can we afford to overlook the popularity of Pope JohnXXIII throughout the world, a popularity based largely onhis humble and self-effacing style of leadership, the exerciseof which was for that very reason all the more effective?Later, Pope John Paul II would exemplify authenticChristian authority in his resolute determination, oftenagainst the wishes of his closest advisers, to admit the mistakesand grievous sins perpetrated by Catholics past andpresent. In his encyclical Ut Unum Sint (Nos. 95-96), PopeJohn Paul II even invited other Christian leaders to explorewith him new ways of exercising his papal ministry as a ministryof unity and not division. Is it a coincidence that thesetwo figures were the most widely admired popes of the 20thcentury by those outside the Catholic Church? Theirs wasan exercise of authority that seemed credible even to thosewho did not share the faith of the church.Many of us become frustrated when we read atheists’attacks on religion, because we do not recognize ourselvesand our religious communities in their scathing portraits.Yet we must resist channeling our frustration into equallyvicious counterattacks. Instead, let us search our own faithtraditions and purge them of all that obscures what is mostprecious to us. For we remain convinced that our deepestreligious convictions do not “poison everything” but affirmall that is good and gently invite all into communion withthat Holy Mystery “in whom we live and move and haveour being.”AA Symposium -Apostolic Religious Life since Vatican II....Reclaiming the Treasure: Bishops, Theologians,and Religious in ConversationStonehill College, Easton, MassachusettsSaturday, September 27, 20088:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m.Keynote speakers:Franc Cardinal Rode, C.M.Prefect of the Congregation for Institutes ofConsecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic LifeSister Sara Butler, M.S.B.T.Member of the International Theological CommissionHomilist:Sean Cardinal O’Malley, O.F.M. Cap.Archbishop of BostonCost: Free, compliments of Stonehill CollegeRegistration Deadline: May 31, 2008For schedule and signup, visitwww.stonehill.edu/rlsIn Celebration of the200th Anniversary ofthe Archdiocese of BostonHosted byThe Diocese ofFall RiverStonehill CollegeContact: Rev. Thomas Looney, C.S.C.tlooney@stonehill.edu or 508-565-1551May 5, 2008 <strong>America</strong> 15

True BelieversHave the new atheists adopted a faith of their own?BY JOHN F. HAUGHTThe atheist, by merely being in touch with reality, appearsshamefully out of touch with the fantasy life of his neighbors.– Sam HarrisJust those who feel they are...most fully objective in theirassessment of reality, are most in the power of deep unconsciousfantasies.– Robert BellahJOHN F. HAUGHT is senior fellow of science and religion atWoodstock Theological Center, Georgetown University,Washington, D.C. He is the author of God and the NewAtheism: A Critical Response to Dawkins, Harris, and Hitchens.THE BESTSELLING BOOKS by Richard Dawkins,Daniel Dennett, Sam Harris and ChristopherHitchens provide colorful portraits of the evils ofreligion. Theyappeal especially to themoral sensitivity of readersand easily awaken outrageat the “poison” associatedwith the various faith traditions,not least those thatclaim descent fromAbraham. Ultimately,however, as our “new atheists”would surely agree, itis not in the name ofmorality alone, but especiallyin the name of reasonthat they must convincetheir readers of the wrongnessof religious faith. Inthis essay I shall show howthey fail to do so by posingthree sets of questions tohighlight the fundamentalbeliefs—that is the appropriateword—that underlie the worldview of Dawkins andcompany. Before doing so, however, let us look at the historicaland scientific roots of the new atheism and how it hasdeveloped into its current insidious form.The intellectual foundation of the new atheism is notnew. It is the well-worn modern worldview known as “scientificnaturalism,” a label first used by T. H. Huxley in the19th century to emphasize the principle that science mustnever appeal to supernatural explanations. As understoodtoday, however, scientific naturalism goes far beyond whatHuxley intended. It decrees that the natural world, includinghuman beings and our creations, is literally all thatexists. There is no divine creator, no cosmic purpose, nosoul and no possibility of life beyond death.Most scientific naturalists are avowed materialists. Theybelieve that lifeless and mindless physical stuff, evolving byimpersonal natural processes over billions of years, is theultimate origin and destiny of everything, including livingand thinking organisms. “According to the materialists,”the philosopher Daniel Dennett claims in his bookConsciousness Explained, “we can (in principle!) account forevery mental phenomenon using the same physical principles,laws and raw materials that suffice to explain radioactivity,continental drift, photosynthesis, reproduction,nutrition and growth.”Since Darwin, scientific naturalists have increasinglyalloyed their materialism with evolutionary accounts of life.Darwin’s notes reveal that he too was tempted occasionallyART BY STEPHANIE RATCLIFFE16 <strong>America</strong> May 5, 2008

to make materialism the foundation of his own understandingof evolution. But where Darwin felt uneasy splicingbiology onto such an inherently atheistic metaphysics, todaymany biologists and philosophers have no such hesitancy.Especially after it became possible in the last century tounderstand evolution in terms of genes migrating blindlyfrom one generation to the next, the irresistible temptationScientism and scientific naturalismframe every page of the newatheistic tirades. These wearyconstraints on human thoughthave been around for a long time.has arisen to resolve the entirety of life into a specialinstance of matter in motion.This reduction is the basis of Dawkins’s and Dennett’sunderstanding of evolution, and both Harris and Hitchensgo along with it. Dennett’s Breaking the Spell and Dawkins’sThe God Delusion assume that all living phenomena, includingour own ethical instincts and religious longings, can beadequately accounted for in an evolutionary and materialistmanner. Theological explanation, therefore, is now utterlysuperfluous.Scientism and the End of FaithThe materialist worldview espoused by the new atheists isitself the offspring of “scientism,” the widely sharedassumption that modern scientific method is the only wayfor reasonable, truth-seeking people to gain knowledge ofthe real world. Science, Harris insists, “has become the preeminentsphere for the demonstration of intellectual honesty.”Dawkins is even more emphatic: “It may be thathumanity will never reach the quietus of complete understanding,but if we do, I venture the confident predictionthat it will be science, not religion, that brings us there. Andif that sounds like scientism, so much the better for scientism.”For the new atheists science always trumps religiousbelief. Why? Because scientific method formulateshypotheses about phenomena on the basis of physicalobservations that can be tested over and over. Since religiousideas, by contrast, are not subject to publicly repeatableempirical verification (or falsification), rational inquiryrequires that they disown them.Religions, the new atheists complain, stem from “faith,”that is, from irrational acts of what they call “belief withoutevidence.” This is far from being a theologically informeddefinition, but it supports the new atheists’ declaration thatfaith is utterly opposed to science. “Pretending to knowthings you do not know is a great liability in science,” saysHarris, “and yet, it is the sine qua non of faith-based religion.”Hitchens adds, “If one must have faith in order tobelieve in something, then the likelihood of that somethinghaving any truth or value is considerablydiminished.”Since there is no scientifically accessible“evidence” to support the claims of religiousfaith, the authors classify them as “delusions.”According to Dawkins, the methods a goodtheologian should use “in the unlikely eventthat relevant evidence ever became available,would be purely and entirely scientific methods.”Science alone can decide the question ofGod.Scientism and scientific naturalism frameevery page of the new atheistic tirades. These weary constraintson human thought have been around for a long timeand still command a wide following in academic circles.What, then, is so new about the “new” atheism?Aside from the heavy dose of Darwinian materialism inDawkins’s and Dennett’s accounts of religion and morality(and even this is not peculiar to them), the only real noveltyadvanced by the four authors examined here is theirastounding intolerance of faith in any form. Since they takefaith to be the root cause of innumerable evils in the world,Dawkins, Harris and Hitchens instruct readers that it istime to erase every instance of “belief without evidence”from every human mind.Our critics warn that this ideal will never be actualizedas long as we keep nurturing the modern liberal tolerance offaith. In democratic societies most of us still assume uncriticallythat people have a right to believe whatever they want,but this leniency only makes the world ever more dangerous,the critics say. Most instances of faith may seem harmlessenough, but permissiveness toward any beliefs forwhich evidence is lacking opens an abyss in human mindsthat will inevitably be colonized sooner or later by the mostmonstrous religious lunacy. Events such as the terroristattacks of Sept. 11, 2001, should be proof enough that bytolerating faith to any degree, religious and secular liberalsalike become accomplices in evil.Theologians are especially to blame for making spacefor faith in people’s minds, according to the new atheists.That academic departments of theology still exist in an ageof science is, to them, a nauseating anachronism. “Surelythere must come a time,” Harris remarks, “when we willacknowledge the obvious: theology is now little more thana branch of human ignorance. Indeed, it is ignorance withMay 5, 2008 <strong>America</strong> 17

wings.” Adopting the spirit of science, on the other hand,should help rid the world of theology and faith. Thereby itshould also help dispel our liberal tolerance of all kinds of“belief without evidence.”Three Questions for the New AtheistsWhat do the new atheists mean by evidence? They do notbother to clarify the term carefully, but undoubtedly it signifiesfor them whatever can be subject to scientific testing.To the new atheists, therefore, we must put the questionwhether the imperative to ground all claims to truth in scientificevidence is itself reasonable. We might begin by posingthree sets of questions to all four authors.Isn’t your belief that science is the only reliable road to truthself-contradictory? Your scientism instructs you to take nothingon faith, and yet faith is required for you to embrace thecreed of scientism. You have formally repudiated any ideasfor which there is no tangible or empirical “evidence.” Yetwhere exactly is the visible evidence that supports your scientism?What are the scientific experiments that lead you toconclude that science alone can be trusted to lead you totruth? Wouldn’t you have to believe—without evidence—inscience’s capacity to comprehend everything before settingup such experiments in the first place?To undertake scientific research, don’t you have to start outwith several important beliefs? You must take it on faith, asAlbert Einstein was perceptive enough to realize, that theuniverse you are exploring is intelligible or comprehensible.That the universe is intelligible at all is a great mystery thatyou cannot account for in scientific terms. Instead you mustapproach the cosmos with a sustained faith that it will continueto make sense as you probe deeper into it.Next, you cannot commit yourself to a life of rationalinquiry—or even write your atheistic manifestos—withoutbelieving constantly that truth is worth pursuing. Hereagain you cannot provide any scientific evidence to supportthis belief.Moreover, to claim with such conviction that scientismis right and religion wrong, each of you must believe (sinceyou cannot prove) that your own mind is of sufficientintegrity to grasp meaning and decide what is true or false.Your evolutionist materialism, however, should, logicallyspeaking, subvert your own intellectual swagger. As CharlesDarwin himself observed, evolutionary explanations of thehuman mind, accurate though they may be historicallyspeaking, are not enough to embolden us to trust our ownthought processes.Evolutionary accounts of your mind’s origin are importantand interesting as far as they go, but your need for logicalconsistency demands that you look for a more securereason to trust your mental functioning. Evolutionarymaterialism, far from providing such a foundation, givesyou every reason to distrust your mind. A theologicalworldview, on the other hand, could conceivably groundand justify the trust you place in your capacity to understandand know the world without in any way contradicting thediscoveries of Darwin’s science.How so? Theology’s claim is that all of creation is everlastinglyembraced by the mystery of God and is invited toenter ever more fully into that mystery. It is this invitationthat accounts ultimately for both the world’s evolutionarycharacter and the human mind’s own restlessness. A profoundfaith that your own mind somehow already participatesin infinite being, meaning, truth and goodness can inprinciple justify your cognitional trust, explain your tirelesssearch for deeper understanding, fortify your love of truthand ground your obedience to conscience. In this sense theologydoes not compete with science but provides essentialsupport to its ongoing adventure of discovery.Can you deny that there are avenues other than scientificmethod by which you experience, understand and know the worldyou inhabit? In your interpersonal knowledge, for example,the evidence that someone loves you is hard to measure scientifically,but is that love unreal? Have you arrived at yourknowledge of another person by way of the objectifyingroad of scientific experimentation? Most reasonable andethical people believe that such an approach to other humanpersons is both intellectually and morally wrong.Do you truly believe that if a personal God actuallyexists, the evidence for this God’s existence could be collectedas cheaply as the evidence to support a scientifichypothesis, as Dawkins requires? Even in your ordinaryexperience, only a position of vulnerable trust can allow youto encounter the subjective depths of another person. Howcould it be otherwise with God, whom believers experiencenot merely as ordinary, but as a supreme “Thou”?Remarkably, Dawkins insists that only science is qualifiedto decide the question of God’s existence, even thoughscience, with its impersonal objectivity, is not wired todetect subjectivity or personhood in any sense. Would notany effort to determine the existence of God primarilyrequire an interpersonal kind of experience, one that couldlead one to knowledge of God?If the universe is encompassed by an infinite love, anyconceivable encounter with this ultimate reality wouldrequire nothing less than a posture of receptivity, a readinessto surrender to its embrace. The new atheists believe thatthey can decide the question of God’s existence withouthaving opened themselves to the personal transformationessential to the formation of faith. One can only ask: what isthe evidence for such a belief?AFrom April 1909, the editors on “Darwinism andPopular Science,” at americamagazine.org.18 <strong>America</strong> May 5, 2008

An Evangelical Moment?To combat the rise of atheism, Christians must first look to themselves.BY RICHARD J. MOUWONE OF THE BEST HOMILIESI ever heard wasbased on the first chapter of the Book of Jonah.The preacher described the situation on board aship that had run into a terrible storm on the wayto Tarshish and a confrontation that ensued between somepagan sailors and a prophet of the true God. Surely, thepreacher observed, we would all put our money on theprophet of God, but this prophet was running away fromGod, and the sailors had figured that out. In that confrontation,said the preacher, an unbelieving worldpreached an important message to the church.I have often thought of those words as the writings onthe new atheism have appeared. Many of my fellow evangelicalshave joined Christians from other traditions ingoing into attack mode, responding to the case being madeagainst religious belief and practice. On many key issuesRichard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris andtheir like are fairly easy targets. Regardless of how otherChristian groups might respond, however, evangelicalshave much to think about, since we loomlarge in the new atheists’ scenarios about thedangers of religious conviction. Specifically, theycriticize the ways evangelicals have led thecharge against the teaching of evolution in publicschools and the larger influence of the religiousright in public life.Beyond Anti-IntellectualismIn both cases, the underlying problems have todo with a streak of anti-intellectualism that haslong plagued the evangelical movement.Historically, we evangelicals have found goodreasons to be worried about the intellectual life.Evangelicalism is a loose coalition of groups thathave their origins in various branches of Protestant pietism,a movement that emphasized the experiential dimensions ofthe Christian faith. European pietism had its beginnings ina reaction against a highly intellectualized orthodoxy thathad come to characterize many Lutheran and ReformedRICHARD J. MOUW is president and professor of Christian philosophyat Fuller Theological Seminary, Pasadena, Calif.Popular evangelicalism is at avulnerable point: many of ourformer heroes have embarrassedus. There may now be morereceptivity to some new thoughtsabout what it means to work forthe common good.churches in the century or so after the Reformation. Theearly pietists protested the way “head knowledge” oftencrowded out “heart knowledge.” The present-day evangelicalmovement includes groups whose histories can bedirectly traced back to these pietists, as well as to Wesleyans,Pentecostals and sectarian primitivists, who emphasizedsimilar experiential motifs.The pietist project of taming the intellect took on a newsignificance in subsequent centuries, when a second battlewas waged, this time not primarily against orthodox intellectualizers,but against the inroads of Enlightenmentthought into the Christian community. The 20th-centuryevangelical struggle against modernism was a continuationof this second battle.Indeed, evangelical worries about the intellectual lifehave had some legitimacy when they have aimed at keepingthe intellectual quest in tune with a vibrant experientialfaith, or when they have addressed the dangers of a worldviewthat disparages religious convictions as such. Butrecent evangelicalism has also been influenced by a brand ofanti-intellectualism fostered by frontier revivalism, a phenomenonchronicled in some detail in Richard Hofstadter’sclassic, Anti-Intellectualism in <strong>America</strong>n Life. Here a seriousengagement with the important issues of life gives way toclichés, slogans and biblical proof texts.During last year’s controversies over Supreme Court20 <strong>America</strong> May 5, 2008

ART BY STEPHANIE RATCLIFFEappointments, Franklin Foer commented in The NewRepublic that we seldom hear about possible evangelicalcandidates for the nation’s highest court. Evangelicals speakup loudly about the need for conservative justices, he wrote,but when conservative nominations are forthcoming thecandidates are typically Catholics. On issues of public policy,Foer observed, Catholics have “intellectual heft” andevangelicals do not. Foer is right about evangelicalism as apopular movement. This lack of heft has made them anespecially easy target for the new atheists. They would notattack evangelicals with such passion if it were not for thenoise factor. As a force in the public square, evangelicalChristians have been hard to ignore in recent years.What has led us to be so noisy? It was not always so. Inmy youth it was not uncommon for the more liberal typesto complain that evangelicals were much too quiet aboutissues of social concern. My guess is that nowadays thosepeople—the ones who are still around—are looking backwistfully to the good old days.Evolution played a big role in silencing us in earlierdecades. The historian George Mardsen once observedthat moving from the 19th to the 20th century was forNorth <strong>America</strong>n evangelicals an immigrant experience ofsorts. The migration was not geographic but cultural. Mostof the 19th-century evangelicals were active in public life,even playing a key role in promoting abolition andwomen’s suffrage. Entering into a new century, however,evangelicals found themselves defending the fundamentalsof their faith against an emerging Protestant liberal movement.The battle did not go well for the evangelicals, wholost control of the major Northern denominations and theologicalfaculties. Soon they lost again, in the battle againstevolutionism that came to a head with the famous Scopestrial. This time their defeat brought with it much publicridicule. The evangelicals retreated to the margins of culture,adopting a theological perspective that emphasizedtheir status as a “true remnant” and viewed the flow of historyin apocalyptic terms.From Minority to Majority ConsciousnessA sense of cultural marginalization characterized<strong>America</strong>n evangelicalism well into the 1970s. Then suddenlyin 1979 a movement that had for a half-centurydefined itself as a cognitive minority in a society headedtoward Armageddon now proclaimed itself to be theMoral Majority. Evangelicals had once again become aMay 5, 2008 <strong>America</strong> 21

noisy presence in the public square.The shift from minority to majority status took placewithout much theological reflection. Not long after JerryFalwell appeared on the public scene, for example, he confessedthat he had once preached a sermon denouncingMartin Luther King Jr., on the grounds that preachersought not to be involved in politics. Now he was ready toadmit that King had been right. Unfortunately, Falwellnever offered much of an explanation as to the theologicalbasis for his change of heart. Had he now embraced a differentunderstanding of “Bible prophecy” from the dispensationalismthat had shaped his previous ministry? Did hehave a new doctrine of the church? What was his theologicalgrasp now of the common good, public justice and therelationship between church and state? Answers to thesequestions were not forthcoming.My own take is that for the past two centuries evangelicalshave gone back and forth between two eschatologicalperspectives. Typically we have done so without much theologicalawareness. Thus, in the late 1970s, when theprospects for cultural influence suddenly looked good, theevangelicals switched back to a more hopeful eschatology.Once again <strong>America</strong> was a chosen nation that could serveGod’s revealed purposes, if only the faithful would restorethe nation to its founding vision.If this new activism was not generated by a new theologicaldiscovery, what did account for the enthusiasm forpublic policy issues? One factor was a shift in class. By the1980s, many evangelical Pentecostal and holiness congregations,which had once resided on the wrong side of thetracks, had become flourishing megachurches sitting on thebest real estate in town. This turnabout nurtured a sense ofcultural leverage.What motivated evangelicals to use their leverageaggressively to bring about change was a concern about therearing of children. In large part the religious right hasarisen as a response to the sexual revolution that wassparked in the 1960s. The increasing visibility of pornography,the gay rights movement, the promiscuity that camewith the availability of the pill—all of these made evangelicalparents very nervous about the introduction of sex educationin the public schools. Many early initiatives by thereligious right were directed against school boards.That was also the case with creation science, a crusadethat had much to do with parental concern about schools.While the “young earth” adherents have presented theirviews as an alternative science, there has not been muchcareful, give-and-take dialogue about the nature of scientificinquiry and the relationship between the Bible and science.Much of the rhetoric has been fueled by conspiracytheories, relying heavily on sloganeering and the use of biblicalmaterials as proof-texts.A New Openness Among EvangelicalsThe irony is that while grass-roots evangelicals have beenembarrassing themselves in public life, many of their sonsand daughters have gained a significant voice in the<strong>America</strong>n academy. The cover story of The Atlantic forOctober 2000 boldly announced, “The Opening of theEvangelical Mind.” Alan Wolfe, who wrote the story, notonly chronicled the scholarly contributions of evangelicalschools like Calvin College, Wheaton College and FullerSeminary, but he also pointed out that the history and theologydepartments at the University of Notre Dame havebecome a home for many evangelical professors and graduatestudents. Just recently Mark Noll left Wheaton toassume the professorship at Notre Dame previously held byGeorge Mardsen, who had moved to Notre Dame fromCalvin College after making his mark in <strong>America</strong>n religioushistory there. Harvard Divinity School has established anendowed chair in evangelical thought. And evangelicalscholars have been instrumental in forming an array offaith-based associations in several disciplines, like literature,history, philosophy and the natural and social sciences.The problem is not that evangelical Christianity lacksthe intellectual resources to remedy the much-publicizeddefects of popular evangelicalism. Rather, the challenge is tofind some way of repairing the disconnection betweengrass-roots evangelicals and evangelical academics who havebeen making their marks in the scholarly disciplines.Surely there is much to criticize in the freewheelingattacks on the faith that have been launched by the newatheists, and evangelical scholars have a contribution tomake to those debates. It is also an opportune time for evangelicalsto speak clearly to our own community of faith.Popular evangelicalism is at a vulnerable point: many of ourformer heroes have embarrassed us. There may be morereceptivity now to new thoughts about what it means towork for the common good.We academics will need pastoral support in making sucha case to our own people. We can take encouragement fromthe fact that some wise evangelical pastors have emerged aspublic leaders during the past decade. Bill Hybels, JoelHunter and Rick Warren, for example, have not only takenon different issues (AIDS, global warming, economic justice)than the religious right traditionally did, but have doneso with a sense of kinship with the evangelical scholarlycommunity and a spirit of civility toward those whom thereligious right often identified as enemies of the faith.This may be the right time for evangelicals to reflecton how people whom we have identified as our enemiesmay actually be speaking some truths to us. Perhaps in themysterious ways of providence the new atheists have beenraised up as unwitting servants of the Lord for such a timeas this.A22 <strong>America</strong> May 5, 2008

Called to LoveChristian witness can be the best response to atheist polemics.BY STEPHEN J. POPEWHO ARE the “newatheists”? Broadlyspeaking, they area collection ofwriters who have come togetherin recent years in their disdain forthe very idea of God. Theyregard religion as the last bastionof superstition, obscurantism andfear and see the Christianchurches as dedicated to inhibitingprogress and human freedom.They regard biologicalevolution as providing the bestoverall account of who we are,where we have come from andwhere we might go as a species.Religion “poisons everything,”proclaims the journalistChristopher Hitchens, and religiousmorality amounts to psychologicalabuse. The sociobiologistRichard Dawkins describesreligion as a “virus,” and in The God Delusion proclaims thatmonotheism is “the great unmentionable evil at the centerof our culture.” Dawkins regards theistic ethics as commandingobedience to a biblical God whose jealous and violentcharacter is anything but morally admirable. Thephilosopher Daniel Dennett depicts religion as a willfulattempt to pass on ignorance through promises that cannever be kept. He asserts that religious morality based onsacred texts immunizes people from asking critical questions.And in The End of Faith, Sam Harris argues that faithonly generates “solidarity born of tribal and tribalizing fictions.”Its promotion of irrationality dangerously sanctionsa habit of acting out of religious conviction unrestrained byhumility or compassion.One can certainly raise questions about the accusationsof the new atheism, but practical constraints narrow mySTEPHEN J. POPE is professor of theological ethics at BostonCollege and author of Human Evolution and Christian Ethics(Cambridge University Press, 2007).focus to three issues: first, therelation between belief in Godand morality; second, the relationbetween morality, reason andreligion; and third, the relationbetween morality and theChristian ethic of love. The newatheist critique of Christianmorality usually applies (if at all)only to a fundamentalist minorityof Christians. Yet because this literaturehits home with manyreaders, we Christians have totake seriously both its criticismsand our responsibility to presenta better public witness to thetruth of the Gospel.Is God Necessary forMorality?Much of the new atheist literatureis reactive in that it beginsby sharply criticizing what itrejects. The new atheists react against a triple claim oftenadvanced by religious people: that belief in a personal Godis necessary for people to have moral knowledge, for peopleto do what is right and avoid wrong, and for people to justifymoral absolutes.First, some Christians claim that belief in a God whoreveals the divine law presents the sole (or most reliable)basis for knowing right from wrong. Reason takes people allover the place, but only religious authority can settle thingsonce and for all. Yet the value of a given moral authoritydoes not prove either its legitimacy or reliability. Such anapproach to moral security is made the more troublesomeby the fact that Christians who rely on the same scripturalauthority, as well as Catholic Christians who profess loyaltyto a single hierarchy, often disagree on moral issues. Beliefin God does not exempt one from the difficult work ofinterpreting the significance of specific biblical texts orchurch teachings for our own day. On the contrary, it canmake moral reasoning at least as complex as anything onefinds in texts of moral philosophy.ART BY STEPHANIE RATCLIFFEMay 5, 2008 <strong>America</strong> 23

The Catholic tradition walks a middle way between thereligious positivist, who says we ought to rely only on religiousauthority, and the new atheist, who claims reason tobe self-sufficient. Catholics affirm the need for communityand the value of the accumulated wisdom of the past;Catholics also hold that each person is created with a conscienceand has access to the natural law through the exerciseof his or her moral intelligence. God teaches us throughthe exercise of our reason within the church and the broadersocial world within which we act.Second, some Christians assert that belief in God suppliesa necessary motive for doing right and avoiding wrong.The so-called sanction argument holds that fear of divinewrath keeps people on the narrow path; without it people arecapable of anything. The new atheists properly target thosewho take this deeply pessimistic view of the human person,curbed from evil only by threat of eternal punishment. AsHarris puts it, our “common humanity is reason enough toprotect our fellow human beings from coming to harm.”On this point, Catholic moral anthropology is closer tothe new atheists than to Christian fear-mongers. It regardseach person’s conscience as capable of being moved by aninnate “connaturality” with the good. God does not inspirein us a servile fear, which, as David Hume noted long ago,is an essentially egocentric position. Rather, Christian lifecalls us toward authentic love of God, neighbor and self andteaches us that we ought to fear sin and love God as our saviorand redeemer.Third, the new atheists reject the claim that only beliefin God provides the basis for exceptionless moral prohibitions.Harris regards moral absolutism as proposing a “certaintywithout evidence” that “is necessarily divisive anddehumanizing.” Even Christian critics see the questionbeggingnature of an apologetic tack that takes for grantedthe legitimacy of moral absolutes. It also ignores the factthat some atheists display a very strong moral code, justifiedby reasons independent of belief in God. The new atheistsrecognize the wrongfulness of murder, rape and the like. Yetone might argue that this thin concession does not providea sufficiently detailed ethic regarding morally complex andcontentious cases, especially concerning the most vulnerableamong us. Moral absolutes against abortion, embryonicstem cell research and physician-assisted suicide can bemaintained, Christians might argue, only by reliance ondivinely mandated or church-endorsed morality.Yet the fact that Christians themselves are sharply dividedover the ethics of life indicates that belief in God does notnecessarily guarantee consensus over the content of particularmoral absolutes. The significant gap between the smallminority of Christians who accept the absolute prohibitionon artificial contraception and the vast majority who differentiatebetween its properand improper usesChristian ethics is based on the belief thatthe purpose of human existence is neitherthe ‘replication of genes’ nor the ‘survival ofthe fittest,’ but the development of ourcapacity to understand and to love.illustrates this point. TheCatholic natural law traditiondoes not teach thatwe come to know thestrictly binding characterof these norms onlythrough divine revelationor ecclesial instruction. Itaffirms that one canattain knowledge of moral norms through the use of humanmoral intelligence.Is Christian Ethics Irrational?A major issue raised by the new atheists concerns the relationbetween Christian morality and reason. The new atheistswant us to reject Christianity for the sake of moralprogress, then to draw an antinomy between two massivedomains of human agency—reason and religion—in orderto promote the dominance of the former and the destructionof the latter. At times they concede that the Christiantradition has made some important historical contributionsto human well-being (including universities and hospitals),but they argue that everything good in the Christian traditionis because of the operation of reason within it.Conversely, everything bad in the tradition is because ofreligion, not reason. This line of argumentation is arbitrary,tendentious and viciously circular. It ignores the fact thatthe global (and ill-defined) categories of “reason” and “religion”are not alternatives but rather two forms of humanactivity that can be related variously: competitively, cooperativelyor in other ways. From a Christian standpoint, thecause of evil can be attributed neither to religion nor reason,but to human sin—the willful decision to put what is essentiallygood to evil uses out of greed, pride or other twistedmotivations.There is no question that sometimes evildoing has beenpursued under the guise of religion, but the same can be saidof science. The new atheists display their innocence of thecomplexity of historical causation when they simply point to“religion” as the prime cause of the wrongdoing of24 <strong>America</strong> May 5, 2008

Christians, ranging from Augustine’s defense of using violenceto repress heretics to the “silence” of Pius XII duringthe Holocaust. One could just as easily (and cheaply) blamereason for similar horrors. If the Nazis had not been sointelligently organized, they could not have managed theirfactories of death so efficiently. I say this facetiously, but thewritings of the new atheists are replete with such simplemindedrhetoric from self-appointed champions of reason.Is the Christian Ethic of Love Unrealistic?Some of the new atheists, informed by sociobiology andevolutionary psychology, hold that Christian morality proposesan impossibly high norm of love;meanwhile, the actual conduct ofChristians tends to conform to neo-Darwinian expectations that we care for“our own” and not others. In their view,what we need is a more realistic ethic,less lofty but more effective.Dawkins regards morality as a set ofnormative standards that rewards goodacts with social approval and punishesbad acts with social disapproval, andwithin which an individual promotes hisor her evolutionary self-interestthrough morality. Altruism typicallytakes one of four forms: “kin altruism”toward relatives and especially our ownchildren; “reciprocal altruism,” whichtrades benefits with friends in mutuallybeneficial relationships; generous acts,which accrue “reputational benefits”;and acts of assistance, which enhance anindividual’s own social status. In everysociety morality promotes individualconformity to socially agreed-upon patternsof reciprocity that allow communitiesto function with some degree oforder, regularity and peace. Christianmorality does the same.The new atheists regard Christianlove as a completely unrealistic form ofaltruism. Despite high-flown sentiments,most Christians channel theirresources to their own loved ones ratherthan to the poor. A small degree ofaltruism can be taught by culture, butinstructing human beings to be altruisticis, to use Dawkins’s metaphor, liketraining a bear to ride a unicycle.Altruism toward a stranger is an “evolutionarymistake,” and those who regularlypractice indiscriminate altruism can expect to be evolutionaryfailures as well as impoverished.Advocates of Christian morality can respond to thisposition in several ways.First, it is important to admit that the actual conductof Christians often leaves a great deal to be desired. Ingroupfavoritism and out-group oppression, sometimesagainst one another’s subgroups and more often againstoutsiders, can do more damage to the Christian communitythan any new atheist tract ever could. The new atheistsecho Freud’s denunciation of the contradictionbetween the universal ethic of the Gospel and the historyMay 5, 2008 <strong>America</strong> 25

Catholic Studies ProgramWriting and the CatholicImaginationRon HansenAuthor of Mariette in Ecstasy and Exiles, a newnovel about Gerard Manley HopkinsThursday May 8, 7:00 p.m.Cortelyou Commons2324 N. Fremont St.Chicago, IL 60614FREE AND OPEN TO THE PUBLICFor more information email Farrell O’Gorman atwogorman@depaul.edu, or visithttp://condor.depaul.edu/~cathstd/of Christian brutality toward the Jews.Second, the new atheists’ moral critique replicates theChristian tradition’s own internal criticisms of religioushypocrisy, apathy and self-deception. The prophetic tradition,for example, launched its sharpest criticisms againstthose who practiced liturgical correctness while being indifferentto the suffering of the poor. And it is clear that wehave yet to grasp fully the implications of Jesus’ mission tosave sinners, not the righteous. Christian prophets have recognized,as Dorothy Day once observed, that the Christianmust live in a state of “permanent dissatisfaction with thechurch.”Third, the critique applies to sectarian Christianswho suggest that the Christian ethic constitutes a completelyradical way of life that transcends all normalhuman needs and limitations and to those who interpretdiscipleship as an ethic for saints and heroes, but not forordinary people. Yet Catholic ethics regards grace as theperfection of human nature, not its enemy. The churchacknowledges that divine grace enables people like OscarRomero to lead heroically self-giving lives. The churchalso understands that grace calls most of us to follow theGospel in everyday life as we take care of our families,friends and neighbors. Even the most demandingChristian ideals, such as the preferential option for thepoor, are sustained when they are are pursued within lifegivingpersonal relationships and communities.Learning From the New AtheistsThe anti-religious polemics offered by the new atheists areoften unfair, uninformed and hysterical. Yet their body ofwork offers us a salutary reminder of the importance of twodimensions of moral integrity: the intellectual and the practical.Christian ethics is based on the belief that the purposeof human existence is neither the “replication of genes” northe “survival of the fittest,” but the development of ourcapacity to understand and to love.The new atheists rightly complain about the unreflectiveand ill-informed nature of much Christian belief.Harris laments, for example, the pervasive superficiality andanti-intellectualism of popular Christianity; Dawkins criticizesthe “distressingly little curiosity” that religious peopleshow regarding their own faith. It is no consolation that secularpeople in our society display similar weaknesses. Whilethe attacks of the new atheists reveal their ignorance of theChristian faith, their call for greater intellectual honestywithin the Christian community is appropriate and ought tobe heeded.The new atheists also consistently point to a gapbetween Christian beliefs and Christian conduct. But if theflawed conduct adds fuel to the new atheists’ fire, does notthe highest Christian witness snuff out at least some of theflames? Beliefs begin to make senseonly when they are embodied in reallives. True Christians exemplify thelove of God and neighbor in everydaylife in work, family and community life;and the examples of Christians whoselflessly serve the poor and neglectedare worth more than 1,000 books onmoral theology.For most of us, belief or unbeliefhas little to do with proofs for God’sexistence or the intellectual cogency ofTrinitarian theology. Most people areattracted (or repelled) by the quality ofthe lives of the individual Christiansthey encounter, rather than by theintellectual appeal of Christian beliefs.The primary response of Christians tothe new atheism, then, should not be tomarshal better moral counterarguments,but to engage in concreteactions that show that Christian beliefsare not sentimental illusions. As theauthor of 1 John put it, “let us love notwith word or with tongue but in deedand in truth” (3:18).A26 <strong>America</strong> May 5, 2008